The NS5 protein expression of certain flaviviruses, such as Dengue virus type 2, West Nile virus, Hepatitis C virus, and GB virus type C, is associated with a reduced in vitro human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) viral load. To evaluate the suppression effect of the dengue virus serotype 1 (DENV1) NS5 protein on HIV replication, a CD4+ T-cell line was transfected with a plasmid that contained the coding sequence of the DENV1 NS5 gene, and later, it was infected with HIV. DENV1 NS5 protein expression suppressed HIV replication by 28.88% (P < 0.005) on the fifth day compared with the control cells. These results confirm the suppression effect on HIV replication when the DENV1 NS5 protein is expressed in CD4+ T cells. Additional studies are needed to understand exactly how the DENV1 NS5 protein participates in the inhibition of HIV in vitro.

HIV interaction with other infectious agents, especially in tropical regions, is associated with accelerated HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) disease progression. However, Watt and others1 reported that HIV and dengue interaction was associated with a reduced HIV viral load. In regard to this finding, there are only four reports on HIV and DENV interaction in humans. The first study refers to an HIV patient infected with DENV1, in which a reduction in the viral load was observed during the coinfection.1 The second study describes an HIV patient with dengue hemorrhagic fever in Brazil,2 and the third report is a case series that includes five HIV patients infected with dengue in Singapore.3 Finally, a DENV3 and HIV coinfection in Cuba was described.4 Previous in vitro studies have reported that NS5 protein expression in certain flaviviruses, including DENV2, West Nile virus, Hepatitis C virus, Yellow Fever virus, and GB virus type C(GBV-C), is associated with HIV replication suppression in CD4+ T cells, which is attributed to an increase in the stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) cytokine level expression.5 SDF-1 is the principle ligand for the CXCR4 coreceptor, and it blocks HIV fusion and entry into the CD4+ T lymphocytes.6 Despite the fact that these studies have suggested that the NS5 protein expression of DENV2 and other flaviviruses is associated with elevated levels of SDF-1 expression, the participation of the NS5 polyprotein during HIV suppression is not clear. The present study evaluated the effect of DENV1 NS5 protein expression on HIV replication in a CD4+ T-cell line.

An in vitro study was carried out, in which Jurkat CD4+ T-cell cultures were infected with HIV. A DENV1 NS5 gene coding sequence was introduced into the experimental group, whereas the control group was only infected with HIV. HIV p24 antigen levels were measured as a viral replication estimator at the end of the experiment.

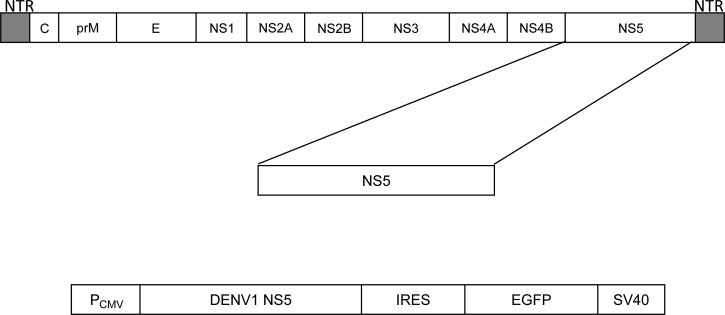

Plasmid design

A pInternal Ribosome Entry Site - Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (pIRES-EGFP) 5.3-kb expression plasmid (Clontech) was used to introduce the coding sequence of the DENV1 NS5 gene (FJ850113; GenBank) that was synthesized by Epoch Life Science, Inc. Gene sequence is identical to the detected gene sequence in patients infected with dengue virus from the state of Colima, México (López-Lemus UA and others, unpublished data). The plasmid was modified by adding a stop codon at the end of the NS5 gene sequence (Figure 1), and the Kozak sequence was not added, which is in contrast to the process described by McLinden and others.7 The transfection of Jurkat CD4+ T cells with the plasmid (a bicistronic vector for simultaneous expression of DENV1 NS5 and EGFP) was carried out using the Xfect Transfection Reagent (Clontech) following the manufacturer's recommendations. A stable cell line of transfected cells was obtained with the Geneticin G418 (Gibco) reagent and kept in fresh RPMI 1640 medium (10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 0.25 μg/mL Fungizone [amphotericin B], and 200 μg/mL Geneticin; Gibco) until processing. Expanded cell line was visualized by fluorescence microscopy to confirm the uniform expression of bicistronic messages throughout the population.

Figure 1.

Design of the expression construct. (Upper panel) Organization of DENV genome including untranslated regions (NTRs). (Lower panel) NS5 gene was inserted into a pIRES2-EGFP vector. A stop codon was added at the end of the NS5 gene.

HIV infection

Jurkat CD4+ T cells, at a concentration of 106 cells/mL, were infected with HIV using the blood serum of an HIV-1 patient with a viral load of 5 × 106 copies/mL. The serum sample used in this study was positive for X4 HIV-1 and identified by the Institute for Epidemiological Diagnosis and Reference (Mexican Health Department). The infection protocol was carried out according to the guidelines described by Vicenzi and Poli.8 Five groups were included in the study: (1) healthy cells (with no transfection or infection), (2) cells transfected with the empty expression plasmid, (3) cells transfected with the plasmid containing the NS5 gene, (4) untransfected cells infected with HIV, and (5) cells transfected with the NS5 gene and infected with HIV. For the HIV-infected groups, 105 Jurkat CD4+ T cells per 1 mL that were previously infected with HIV for every 106 transfected cells (experimental group) and untransfected cells (control group) per 1 mL were added to each culture well.

Viral replication measurement

HIV replication was evaluated through the measurement of p24 antigen secreted in supernatants collected over a period of 7 study days. HIV p24 antigen measurement was carried out with the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique, and the GenScreen ULTRA HIV Ag-Ab Kit (BioRad) was used following the manufacturer's instructions. This method is a qualitative method, and therefore, a calibration curve with a standard p24 antigen (< 25 pg/mL) control was used for the quantitative analysis. The relation of the optic density (OD) value over the method's cutoff (Co) point (OD/Co = ratio) was used to correlate the increase or decrease of the p24 antigen level in the culture for the number of days of the analysis by numerical scale percentages.9

All assays and measurements were carried out in triplicate. The Mann–Whitney U test was used for the data analysis with the MedCalc v11.6.1.0 program and a 95% confidence interval. This protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Biomedical Research Center of the University of Colima.

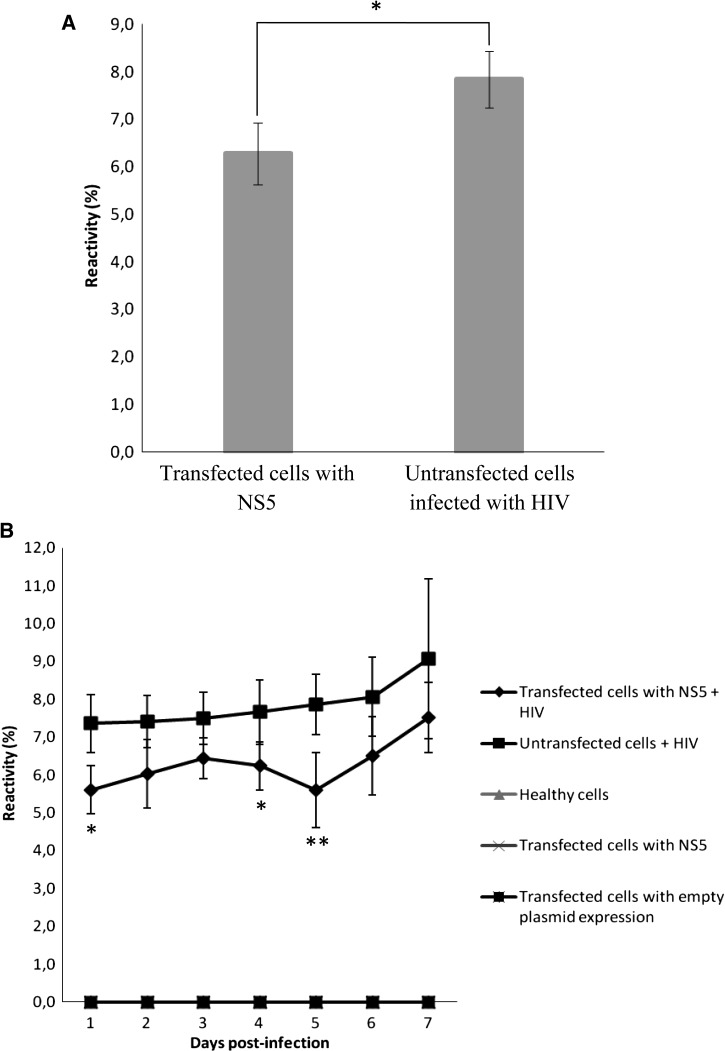

Both the transfected and untransfected cells with no HIV infection (groups 1–3) showed absolutely no HIV replication. Therefore, Figure 2A only shows the results for groups 4 and 5. Viral replication values were significantly higher in the infected cells that were not transfected with the NS5 gene than group 5 cells that were transfected with NS5. However, when the behavior in relation to the 7-day follow-up was analyzed (Figure 2B), viral replication reduction was observed to take place only during the initial phase (from days 1 to 5), whereas on days 6 and 7, this replication tended to reach levels close to those levels of group 4.

Figure 2.

The DENV1 NS5 protein interferes with HIV replication in Jurkat CD4+ T cells. (A) The percentage of HIV p24 antigen reactivity in CD4+ T cells that are transfected with NS5 and not transfected. *P < 0.01. (B) The percentage of p24 antigen reactivity over a period of 7 study days; 25 pg/mL HIV p24 antigen were taken as 100% reactivity. *P < 0.02; **P < 0.005.

The results of this study suggest that DENV1 NS5 protein expression interferes with HIV replication during the initial phase of coinfection with the DENV. Until now, there are only a few case reports1–4 and in vitro studies7,10 that support the idea of DENV participation in HIV suppression.

DENV2 NS5 polyprotein expression suppresses HIV replication > 90% in Jurkat CD4+ T cells when there is an increase in SDF-1 expression levels according to a proposal by McLinden and others.7 However, SDF-1 participation in the process is not clear given that some studies have not confirmed its expression in DENV infection.11–15 Therefore, a more thorough study of SDF-1 participation in RNA viruses, like the dengue virus, is necessary. However, the inhibition of HIV replication in the initial phase of the coinfection was transitory. The results of the present study are similar to the results observed by Watt and others,1 in which there was an inhibitory effect by DENV-1 during days 3–6. We cannot explain this phenomenon; however, we suppose that the NS5 gene expression, or the expression of any other DENV protein, is transitory, and it is possible that the altered SDF-1 transcriptional regulation could be associated with extracellular signals induced by the NS5 protein when it interacts with the CD4+ cell.12,16

In conclusion, the expression of the DENV-1 NS5 replicative protein interferes with HIV replication in Jurkat CD4+ T cells. However, additional studies are needed to understand the main function of the DENV NS5 protein during HIV suppression, especially regarding the role that SDF-1 plays and the factors implied in the rapid inhibition remission. We cannot rule out the importance of studying the effect of the interaction of other DENV replicative proteins on HIV replication, such as the non-structural NS1 and NS3 proteins. These proteins participate together with the NS5 protein during DENV replication, and this multiple protein expression could generate an effect on an in vitro system that is not yet known. The results of these studies could eventually serve as a base for creating new therapeutic agents for fighting HIV infection using specific sequences of the DENV genome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Elvira Mayen-Pimentel, Mariela Trujillo-Cruz, Magali Nova-Cruz, and Lourdes Cano-Santana from the HIV Laboratory of the Instituto de Diagn?stico y Referencia Epidemiol?gicos (InDRE) for their support in this study.

Footnotes

Financial support: This protocol was financed by InDRE-R33, Universidad de Colima - Ramón Álvarez-Buylla de Aldana (UCOL-FRABA)-750/11, and Fondo Institucional de Fomento Regional para el Desarrollo Científico, Tecnológico y de Innovación - Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (FORDECYT-CONACYT) (ID 2009/1-000000000117535) research grants.

Authors' addresses: Uriel A. López-Lemus, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colima, Colima, Mexico, E-mail: lemus_a83@yahoo.com. Clemente Vásquez and Salvador Valle-Reyes, Biomedical Sciences, University of Colima, Colima, Mexico, E-mails: clemvas@ucol.mx and valle_salvador@hotmail.com. Roberto Vázquez-Campuzano and Carmen Guzmán-Bracho, Department of Emerging Diseases and Emergencies, Institute of Epidemiological Diagnosis and Reference, Mexico City, Mexico, E-mails: rvzqzroberto@yahoo.com and carmen.guzman@salud.gob.mx. Diego Araiza-Garaygordobil, Nicte Rebolledo-Prudencio, Iván Delgado-Enciso, and Francisco Espinoza-Gómez, Public Health, University of Colima, Colima, Mexico, E-mails: elezkato@hotmail.com, nicte1331@hotmail.com, ivan_delgado_enciso@ucol.mx, and fespin@ucol.mx.

References

- 1.Watt G, Kantipong P, Jongsakul K. Decrease in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 load during acute dengue fever. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:1067–1069. doi: 10.1086/374600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendes Wda S, Branco Mdos R, Medeiros MN. Clinical case report: dengue hemorrhagic fever in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74:905–907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siong WC, Ching TH, Jong GC, Pang CS, Vernon LJ, Sin LY. Dengue infections in HIV patients. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39:260–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gonzalez D, Limonta D, Bandera JF, Perez J, Kouri G, Guzman MG. Dual infection with dengue virus 3 and human immunodeficiency virus 1 in Havana, Cuba. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:318–320. doi: 10.3855/jidc.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiang J, George SL, Wünschmann S, Chang Q, Klinzman D, Stapleton JT. Inhibition of HIV-1 replication by GB virus C infection through increases in RANTES, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta, and SDF-1. Lancet. 2004;363:2040–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16453-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Clercq E, Schols D. Inhibition of HIV infection by CXCR4 and CCR5 chemokine receptor antagonists. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2001;1:19–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLinden JH, Stapleton JT, Chang Q, Xiang J. Expression of the dengue virus type 2 NS5 protein in a CD4(+) T cell line inhibits HIV replication. J Infect Dis. 2008;198:860–863. doi: 10.1086/591254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vicenzi E, Poli G. Detection and analyses of HIV: infection of CD4+ primary T cells and cell lines, generation of chronically infected cell lines, and induction of HIV expression. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2005;12(12):3. doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im1203s69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutthent R, Gaudart N, Chokpaibulkit K, Tanliang N, Kanoksinsombath C, Chaisilwatana P. p24 antigen detection assay modified with a booster step for diagnosis and monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:1016–1022. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.3.1016-1022.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang J, McLinden JH, Rydze RA, Chang Q, Kaufman TM, Klinzman D, Stapleton JT. Viruses within the flaviviridae decrease CD4 expression and inhibit HIV replication in human CD4+ cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:1–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oishi K, Saito M, Mapua CA, Natividad FF. Dengue illness: clinical features and pathogenesis. J Infect Chemother. 2007;13:125–133. doi: 10.1007/s10156-007-0516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathew A, Rothman AL. Understanding the contribution of cellular immunity to dengue disease pathogenesis. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:300–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lei HY, Huang KJ, Lin YS, Yeh TM, Liu HS, Liu CC. Immunopathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever. Am J Infect Dis. 2008;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang T, Cardosa MJ, Guzman MG. Of cascades and perfect storms: the immunopathogenesis of dengue hemorrhagic fever-dengue shock syndrome (DHF/DSS) Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:43–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lei HY, Yeh TM, Liu HS, Lin YS, Chen SH, Liu CC. Immunopathogenesis of dengue virus infection. J Biomed Sci. 2001;8:377–388. doi: 10.1007/BF02255946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill CS, Treisman R. Transcriptional regulation by extracellular signals: mechanisms and specificity. Cell. 1995;80:199–211. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]