Key Points

Allogeneic donor T cells establish stable contacts with dendritic cells in lymph nodes immediately (2 hours) after they are transplanted.

Endogenous Tregs disrupt stable contacts between T cells and DCs, which are interleukin-10 dependent.

Abstract

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is a systemic inflammatory response due to the recognition of major histocompatibility complex disparity between donor and recipient after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). T-cell activation is critical to the induction of GVHD, and data from our group and others have shown that regulatory T cells (Tregs) prevent GVHD when given at the time of HSCT. Using multiphoton laser scanning microscopy, we examined the single cell dynamics of donor T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) with or without Tregs postallogeneic transplantation. We found that donor conventional T cells (Tcons) spent very little time screening host DCs. Tcons formed stable contacts with DCs very early after transplantation and only increased velocity in the lymph node at 20 hours after transplant. We also observed that Tregs reduced the interaction time between Tcons and DCs, which was dependent on the generation of interleukin 10 by Tregs. Imaging using inducible Tregs showed similar disruption of Tcon–DC contact. Additionally, we found that donor Tregs induce host DC death and down-regulate surface proteins required for donor T-cell activation. These data indicate that Tregs use multiple mechanisms that affect host DC numbers and function to mitigate acute GVHD.

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is the preferred treatment of patients with high-risk acute leukemia, relapsed leukemia, and congenital or acquired bone marrow (BM) failure syndromes, and it has been used increasingly for the treatment of individuals with low-grade lymphoid malignancies.1 More widespread use of allogeneic HSCT is limited by the occurrence of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which is mediated by donor T lymphocytes recognizing disparate minor or major major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens in the host. Donor T cells are activated in secondary lymphoid organs and migrate to GVHD target organs. These cells mediate a proinflammatory process that recruits other immune cells to target organs, leading to GVHD.2 However, the kinetics of activation of donor conventional T cells (Tcons) and their interaction with host dendritic cells (DCs) have not been studied at a cellular level.

The interaction of T cells with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) has been evaluated in vivo using multiphoton laser scanning microscopy (MPLSM). Early studies demonstrated that pathogen-specific transgenic T cells in the lymph node (LN) had a tri-phasic mode of movement and activation.3-5 After the entry of T cells into the LN, T cells formed brief contacts with DCs in a screening phase that lasted for approximately 4 to 8 hours. After screening, pathogen-specific T cells established long-lasting arrest on DCs for more than an hour, and this phase lasted 8 to 12 hours. After the phase of long-lasting interactions with DCs, T cells proliferated, expanded, and differentiated. During activation, the interaction of T cells with DCs was again characterized by very brief interactions. Later, several studies found that relatively high concentrations of antigen can induce rapid or immediate arrest of transgenic T cells on DCs without an initial phase of T-cell screening.6-8 These data would suggest that T-cell screening of DCs is not obligatory when antigen is abundant.9 However, the relevance of these findings to immunity with diverse T-cell repertoires is not clear. All of the studies on T-cell and DC interaction using MPLSM have used transgenic T cells. Furthermore, some of these studies used concentrations of antigen that were not in the physiological range, with only a small population of APCs capable of presenting antigen. The behavior of naïve T cells with a broad repertoire has not been well characterized by MPLSM. In addition, there are no studies that have used MPLSM to evaluate a systemic inflammatory process such as acute GVHD.

Over the past 15 years, a new subset of CD4+ T cells that express the transcription factor FoxP3 and suppress the activation and proliferation of other T cells has been characterized.10-12 Work from our group and others have shown that these regulatory T cells (Tregs), if given in sufficient numbers, can prevent the onset of acute GVHD.13-17 These findings have led to several early phase clinical trials in which Tregs were given to recipients to prevent GVHD.18-20 Although a limited number of patients were treated in these trials, the initial data suggested that Tregs diminish GVHD without increasing the risk of disease recurrence or infection.

Interestingly, despite their clinical use, it is still unclear how Tregs function to prevent GVHD. Our group showed that Tregs with high levels of expression of l-selectin, a protein critical for the migration of lymphocytes into secondary lymphoid tissue (SLT), were much more potent at preventing GVHD than those with a lower level of l-selectin expression.17 This suggested that Tregs needed to migrate to SLT for their activity, although the mechanisms by which they interfere with Tcon activation in SLT are unknown. Furthermore, the use of Tregs has been hampered by their low numbers in vivo and the difficulty of expanding these cells ex vivo. CD4+ T cells in the presence of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and interleukin 2 (IL-2) can be polarized to become FoxP3-expressing inducible Tregs (iTregs) and were shown to inhibit GVHD in a xenogeneic transplant model.21 These cells, which are more easily generated and expanded ex vivo, have attracted interest as a potential therapy for the prevention of GVHD. However, preclinical studies using these cells were not successful in preventing GVHD, due in part to the ability of these cells to revert to effector T cells posttransplantation.22 At this time, it is not clear if the function of iTregs is intrinsically different in their ability to suppress GVHD, or if their lack of function is mediated by FoxP3 instability or some other mechanism.

This study sought to determine the processes by which alloreactive T cells are activated by DCs in SLT. Additionally, we examined how Tregs mitigate this activation and whether endogenous Tregs or in vitro–induced Tregs use the same mechanisms to suppress donor T-cell activation.

Methods

Mice

C57BL/6J (B6), BALB/cJ, IL-10−/−, CD11c-Diphtheria Toxin Receptor (DTR)-Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein (EGFP), and CD11c-YFP mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. FoxP3-multimeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) (FIR) mice were kindly provided by Dr Yisong Wan. All animal procedures have been approved by The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee under the protocol 11-059.

Transplantation systems

Donor T cells and T-cell depleted (TCD) BM cells were prepared as previously described.23 Recipient mice were irradiated at 800 cGy (BALB/c background) or 950 cGy (B6 background) 1 day prior to transplantation with 3 to 5 million donor T cells (or 3 million total T cells, with 2 million Tregs), and 4 to 5 million TCD BM cells. Donor wild-type (WT) or IL-10−/− Treg cells were prepared as previously described.17 Because Tregs in 8-week-old mice are composed of predominantly natural Tregs and a much smaller population of iTregs, we have termed these cells endogenous Tregs (eTregs).

Generation of iTregs

CD4+ T cells were purified from LNs and spleens using negative selection by magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS). CD25-CD4+ T cells were then cultured for 4 days in a 24-well plate in complete Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium, containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of IL-2, and 10 ng/mL of TGF-β.

Intravital imaging

CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice (BALB/c background) or CD11c –YFP mice (B6 background) were lethally irradiated (800 or 950 cGy, respectively). The next day, mice were transplanted with TCD BM cells, CMTPX (Invitrogen)-labeled naïve T cells and unlabeled naïve T cells from B6 mice. In different experiment settings, mice were transplanted with a different combination of labeled T cells, labeled Tregs, or labeled iTregs, with different unlabeled control cells. At 2 to 8 hours and 18 to 24 hours after transplantation, recipient mice were anesthetized and the popliteal LN was imaged using the FV1000MPE microscope (Olympus). Body temperature was maintained at 37°C by an electric warming plate. A plaster cast was put on the hind leg to minimize the respiratory movements and microscopic surgery was done to expose the LN.24 Five z-planes separated by 3 to 5 μm were collected at 60 time points, making each movie approximately 30 to 35 minutes. Images were analyzed using Imaris and Matlab software.

More experimental details can be found in the supplemental Methods available on the Blood Web site.

Results

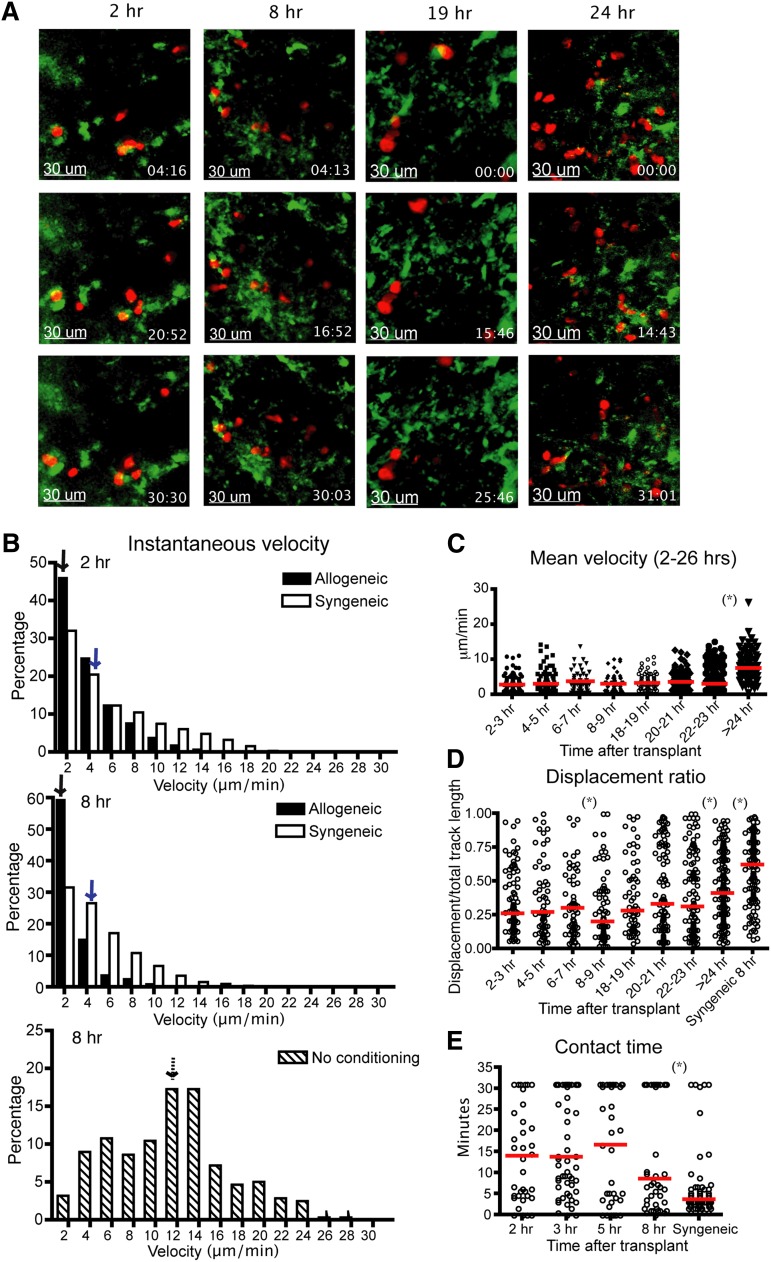

Allogeneic donor T cells do not screen for host DCs in GVHD

Our group has shown previously that the infusion of 5 × 105 B6 T cells mediated lethal GVHD in irradiated BALB/c recipients, with all animals killed by day 25 post-BM transplant (BMT).25 To observe the interactions between donor Tcons and host DCs during the initial phase of GVHD in this model, we used intravital imaging of popliteal LNs of recipient mice. CD11c-DTR-GFP mice (BALB/c background) were irradiated and given labeled B6 donor T cells with TCD BM cells 1 day after irradiation. After transplant, the recipient mouse was anesthetized and the popliteal LN was surgically exposed and observed using the Olympus FV1000 (Figure 1A and supplemental Figure 1a). We found that the instantaneous and mean velocity of donor allogeneic T cells was diminished at 2 to 3 hours after transplantation, comparable to that found at 8 to 9 hours posttransplant (Figure 1B-C). The median displacement ratio was low from 2 to 3 hours to 8 to 9 hours posttransplant (Figure 1D). Combined with similar contact time between donor T cells and host DCs throughout the first 8 hours (Figure 1E and supplemental Movie 1), these data suggest that allogeneic donor T cells require very little time screening DCs before forming long-term interactions after allogeneic BMT. However, the percentage of T cell and DC conjugates that lasted more than 30 minutes was modestly lower at 2 hours compared with the later time points (supplemental Figure 1b), suggesting a small percentage of T cells did require screening of DCs presenting cognate alloantigens. Twenty to 24 hours after bone marrow transplantation, a subset of donor T cells began to increase velocity and displacement (supplemental Movie 2). By 24 hours after transplantation, the majority of T cells were moving rapidly (Figure 1C). These results indicated that the kinetics of allogeneic Tcon–DC interaction do not require a prolonged phase of short encounters to screen for antigen-expressing DCs, supporting the studies using transgenic T-cell receptor T cells with abundant antigen.6 The stable contact phase between T cells and DCs ends at approximately 24 hours posttransfer.3,5

Figure 1.

Donor T cells show decreased velocity, low displacement ratios, and early engagement with DCs in LNs 2 hours after transplant. Intravital imaging of donor T cells (labeled with CMTPX) and host DCs in the popliteal LNs of irradiated or naïve CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice (BALB/c background). (A) Still images from the movies of 2, 8, 19, and 24 hours (hrs) posttransplant. Red cells are donor T cells and green cells are DCs. (B) Instantaneous velocity of donor T cells at 2 and 8 hrs after transplant. Median values are indicated by arrows. Allogeneic (filled bar): donor T cells and BM cells from C57BL/6 mice. Syngeneic (open bar): donor T cells and BM cells from BALB/c mice. Syngeneic–no conditioning (dashed bar): donor T cells from BALB/c mice transferred into naïve nonirradiated CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice. (C) Time course of mean velocity of donor T cells from 2 to 26 hrs after transplant. (D) Displacement ratio (displacement/total track length of 30 minutes) of donor T-cell movement from 2 to 26 hrs after transplant. (E) Contact time between allogeneic donor T cells and host DCs at various time points posttransplant compared with syngeneic T-cell controls. The red bars in all graphs represent median values. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between 2 time points or conditions (*P < .05). Data are representative of 3 separate experiments, with 1 or 2 mice imaged per condition per experiment.

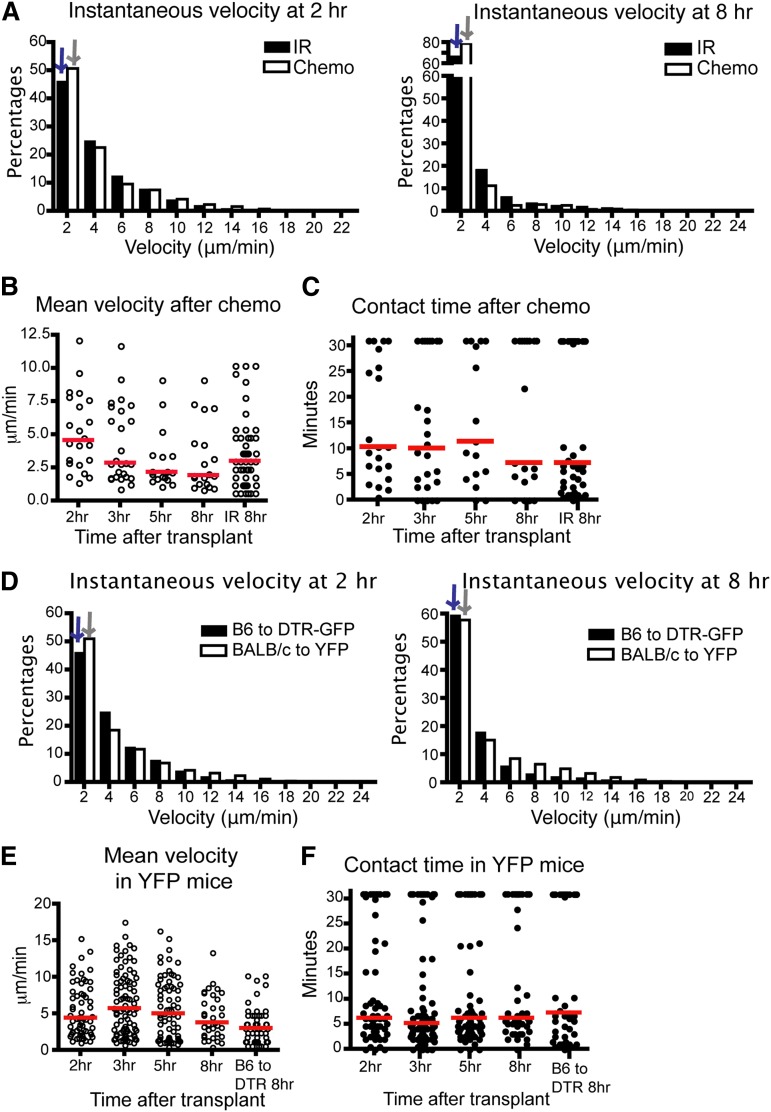

Syngeneic T cells had a higher instantaneous velocity and displacement ratio than allogeneic T cells (Figure 1B-D), indicating that differences in velocity and displacement ratio were not due to conditioning therapy alone. However, there was an effect of conditioning therapy, as syngeneic T cells had diminished velocity in irradiated recipients compared with syngeneic T cells given to nonconditioned recipients (Figure 1B). To examine the effect of a different type of conditioning, we repeated imaging using recipient mice conditioned with chemotherapy. CD11c-DTR-GFP mice were given intraperitoneal cyclophosphamide before transplant and imaging. We found comparable results between donor T cell and host DC interactions in mice conditioned with chemotherapy or radiation. The donor T cells had diminished velocity as early as 2 hours posttransplant and contact time between T cells and DCs was not significantly different up to 8 hours posttransplant (Figure 2A-C). The percentage of T cell–DC conjugates that lasted more than 30 minutes at 2 hours was also slightly lower than at other time points (supplemental Figure 1c), consistent with the data after irradiation. These data indicate that allogeneic donor T cells follow very similar kinetics in host LNs after transplant, which is independent of the process used for conditioning.

Figure 2.

The kinetics of T cell–DC interaction is similar in mice after chemotherapy or in BALB/c to CD11c-YFP mice. (A-C) Intravital imaging of donor T cells (labeled with CMTPX) and host DCs in the popliteal LNs of CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice (BALB/c background) conditioned by chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide 200 mg/kg intraperitoneal 1 day before transplant). (A) Instantaneous velocity of Tcons at 2 and 8 hours (hr) posttransplant compared with Tcons in mice conditioned with irradiation. (B) Mean velocity of Tcons at various time points. (C) Contact time between donor Tcons and host DCs at various time points after chemotherapy. (D-F) Median values for instantaneous velocity are indicated by blue or gray colored arrows. Intravital imaging of BALB/c donor T cells (labeled) and host DCs in the LNs of CD11c-YFP mice (C57BL/6 background). (D) Instantaneous velocity of Tcons at 2 and 8 hours posttransplant in YFP mice compared with those of CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice. (E) Mean velocity of Tcons in YFP mice. (F) Contact time between Tcons and DCs. Each line represents a different time point. The bars in all graphs represent median values. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments, with 1 mouse imaged per condition per experiment.

To confirm that these findings were not model-dependent, we evaluated the velocity of BALB/c T cells and their contact time with DCs after transplantation into CD11c-YFP B6 recipient mice. As shown (Figure 2D-F), BALB/c Tcons have analogously low instantaneous velocity, decreased mean velocity, and similar contact time with DCs from 2 to 8 hours posttransplant. The percentage of T cell–DC interactions lasting more than 30 minutes is lower at 2 to 3 hours compared with 5 to 8 hours, but this difference was not significant (supplemental Figure 1d). Thus, these data indicate that when antigen is not limiting, T cells need a very short time screening of DCs before they form stable interactions. Furthermore, this finding was not model-dependent.

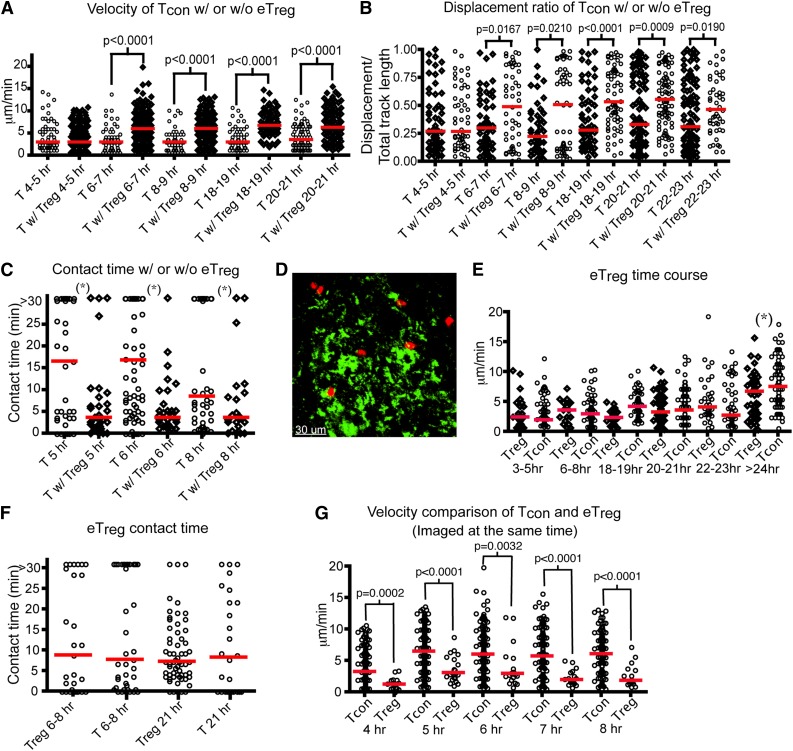

Cotransplant of Tregs disrupts Tcon–DC interactions

Several human clinical trials using eTregs with HSCT have shown that Treg therapy given prior, or at the time of HSCT, was associated with a reduced risk of acute GVHD.18-20 Cotransfer of Tregs at the same time as transplantation of donor Tcons and TCD BM reduced GVHD in murine models.13,17 Therefore, we investigated how eTregs impede donor T-cell activation in real time in vivo. Over 85% of our purified eTregs expressed FoxP3 and they suppressed Tcon proliferation in vitro (supplemental Figure 2a-b), which is analogous to the purity typically found after column-based purification clinically. We administered labeled Tcons with unlabeled eTregs (Tcons:Treg ratio of 3:2) to irradiated CD11c-DTR-GFP mice. We found that Tcons transferred with eTregs have a significantly increased velocity by 6 to 7 hours posttransplant compared with Tcons transferred alone (Figure 3A and supplemental Movie 3). Additionally, the movement of Tcons transferred with eTregs is less confined (Figure 3B). The interactions between DCs and Tcons were substantially altered, with reduced median DC contact time when given with eTregs (Figure 3C). Furthermore, when infused with eTregs, less than 20% of Tcons are in contact with DCs for more than 30 minutes. By comparison, 30% or more Tcons interact with DCs for 30 minutes or longer when transferred without concomitant eTregs (supplemental Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Endogenous Tregs show stable interactions with host DCs and interfere with the interaction between donor T cells and DCs in the LNs. (A-C) Intravital imaging of donor T cells (labeled with CMTPX) and host DCs in the popliteal LNs of irradiated CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice in the presence (Tcon:Treg ratio of 3:2) or absence of unlabeled Tregs. In the absence of Tregs, unlabeled T cells were injected to provide an identical number of donor cells. (A) The mean velocity of donor T cells in the presence or absence of eTregs from 4 to 24 hours (hr) posttransplant. (B) The time course of the displacement ratio of donor T-cell movement in the presence or absence of eTregs. (C) Contact time between donor T cells and host DCs with or without eTregs at different time points posttransplant. (D-G) Intravital imaging of donor eTregs (labeled with CMTPX) and host DCs in the presence of unlabeled Tcons. (D) Still image from movies of eTreg (red) with DCs (green). (E) Comparison of mean velocity between eTregs and Tcons cells at various time points after transplant. (F) Contact time between eTregs and host DCs, compared with contact time between donor T cells and DCs. (G) Comparison of mean velocity between eTregs and Tcons when they were injected into the same recipient. The bars in all graphs represent median values. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between time points (*P < .05) or P value is shown. Data are representative of 2 separate experiments with 1 mouse imaged per condition per experiment.

Next, we evaluated the interaction of donor eTregs with host DCs (Figure 3D-G). The mean velocity of eTregs in the LN was similar to that of Tcons from 3 to 24 hours posttransplant (Figure 3E). Eight hours after transfer, approximately 30% of eTregs were in contact with host DCs for at least 30 minutes; approximately 21 hours after transplant, 15% of the eTregs were still in contact with DCs for at least 30 minutes. These findings are comparable to the percentage of lasting T cell–DC interactions found with transfer of Tcons alone (supplemental Figure 3b and supplemental Movie 4). However, eTregs displayed much lower velocity than Tcons when they were examined together (Figure 3G). Combined with the data showing that contact duration between Tcons and DCs is reduced by eTreg transfer, we conclude that 1 method by which eTregs function is to diminish the early interaction (4 to 8 hours posttransplant) of Tcons with host DCs.

To determine if the contaminating 15% of the cells given with our eTreg infusions affected these results, we sort purified Tregs from FIR mice using the expression of mRFP to greater than 95% purity (supplemental Figure 2c). No differences were found between the mean velocity, contact time, or displacement ratio after the use of highly purified Tregs or less purified, more clinically relevant Treg preparations (data not shown).

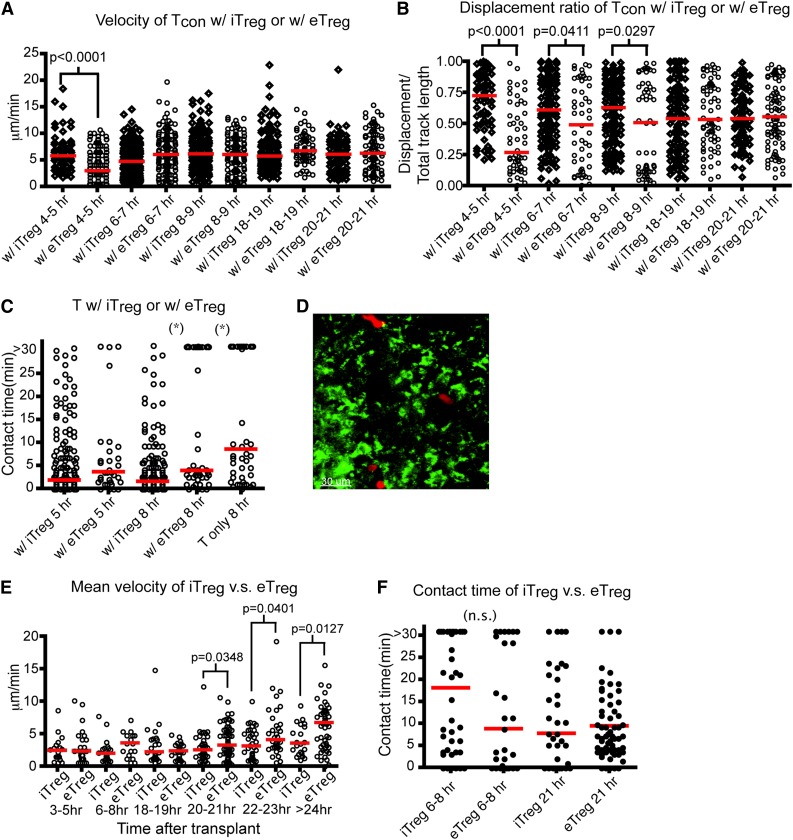

Inducible Tregs also reduce Tcon–DC interactions

Murine Tregs can be induced in vitro by stimulating CD4+CD25− T cells in the presence of TGF-β1 and IL-2. Transfer of these iTregs suppresses allergic pathogenesis.26,27 However, several groups have shown that infusion of iTregs did not prevent acute GVHD in animal models, hypothesized to be due to instability of the iTreg phenotype.22 Whether iTregs intrinsically function differently than eTregs is not clear. Thus, we examined the effect of iTreg transfer on the movement of donor T cells and their interaction with host DCs. The percentage of iTregs generated ex vivo and their function in suppressing proliferation was similar to eTregs (supplemental Figure 2d-e). Interestingly, the velocity of Tcons in the presence of iTregs was statistically greater in the first 4 to 5 hours posttransplant compared with the velocity of Tcons in the presence of eTregs. This correlated with a statistically significant difference in the displacement ratio of Tcons in the presence of iTregs compared with eTregs (Figure 4A-B). As shown in Figure 4C and supplemental Figure 3c, iTregs reduced the interactions between Tcons and DCs comparable to that found using eTregs at 8 hours after transplant (supplemental Movie 5).

Figure 4.

Inducible Tregs interfere with the interactions between donor T cells and host DCs comparable to eTregs. (A-C) Intravital imaging of donor T cells (labeled with CMPTX) and host DCs of irradiated CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice in the presence of eTregs (Tcon:eTreg ratio of 3:2) or iTregs (Tcon:iTreg ratio of 1:1). (A) The time course of mean velocity of donor T cells in the presence of iTregs or eTregs. (B) The time course of the displacement ratio of donor T-cell movement in the presence of iTregs or eTregs. (C) Contact time between donor T cells and DCs with iTregs or eTregs at 5 or 8 hours (hr) posttransplant. (D-F) Intravital imaging of donor iTregs or eTregs (labeled with CMPTX) and host DCs in the presence of unlabeled donor T cells. (D) Still image from movies of iTregs (red) with DCs (green). (E) Comparison of mean velocity between iTregs and eTregs cells at various time points after transplant. (F) Contact time between iTregs–DC in comparison with contact time between eTregs and DCs at 2 different time points after transplant. The bars in all graphs represent median values. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences (*P < .05) or P value is shown. Data are representative of 2 experiments with 1 to 2 mice per experiment.

We also examined the kinetics of iTregs in LNs posttransplant (Figure 4D). The mean velocity of iTregs late posttransplant differed from eTreg after transplant, as iTreg velocity remained diminished even 21 hours after transplant (Figure 4E). However, the longitudinal interaction with DCs was equal between eTregs and iTregs from 8 to 24 hours posttransplant (Figure 4F, supplemental Figure 3d, and supplemental Movie 6). These data suggest that iTregs function similar to eTregs early posttransplantation.

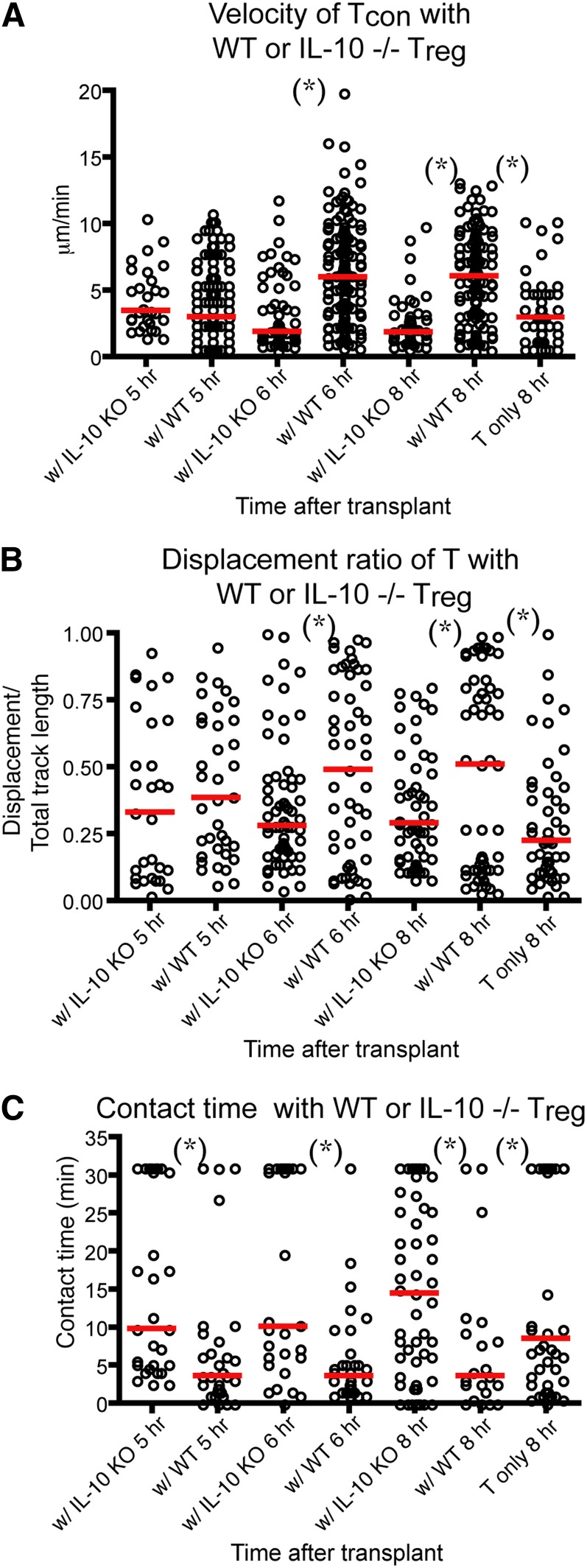

IL-10 is required for the disruption of T cell–DC interaction by eTregs

IL-10 is one of the humoral factors that Tregs use to suppress immunity in vivo.28 IL-10–deficient Tregs have been found to be less effective in preventing acute GVHD in animal models.29 In addition, IL-10 has been shown to directly suppress the maturation and stimulatory functions of DCs.30-32 Therefore, we sought to examine whether IL-10−/− eTregs had decreased the ability to block T cell–DC interaction in our intravital experiments. We found that the cotransplant of IL-10−/− eTregs with Tcons failed to increase the velocity and displacement ratio of Tcons (Figure 5A-B). IL-10−/− eTreg also failed to decrease the contact time and the percentage of T cell–DC conjugates between Tcons and DCs (Figure 5C and supplemental Figure 3e). Our data indicate that eTreg production of IL-10 was critical for the effects of donor Tregs on the interaction between donor Tcons and host DCs.

Figure 5.

IL-10 is required for Treg-mediated disruption of Tcon–DC interaction. Intravital imaging of donor T cells (labeled with CMTPX) and host DCs in the popliteal LNs of irradiated CD11c-DTR-EGFP mice in the presence of WT or IL-10−/− Tregs. (A) The comparison of mean velocity of donor T cells in the presence IL-10−/− or WT Tregs. (B) The comparison of the displacement ratio of donor T-cell movement in the presence IL-10−/− or WT Tregs. (C) Contact time between donor T cells and host DCs in the presence IL-10−/− or WT Tregs at different time points posttransplant. The bars in all graphs represent median values. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences between the groups or time points (*P < .05). Data are representative of 2 experiments with 1 to 2 mice per experiment.

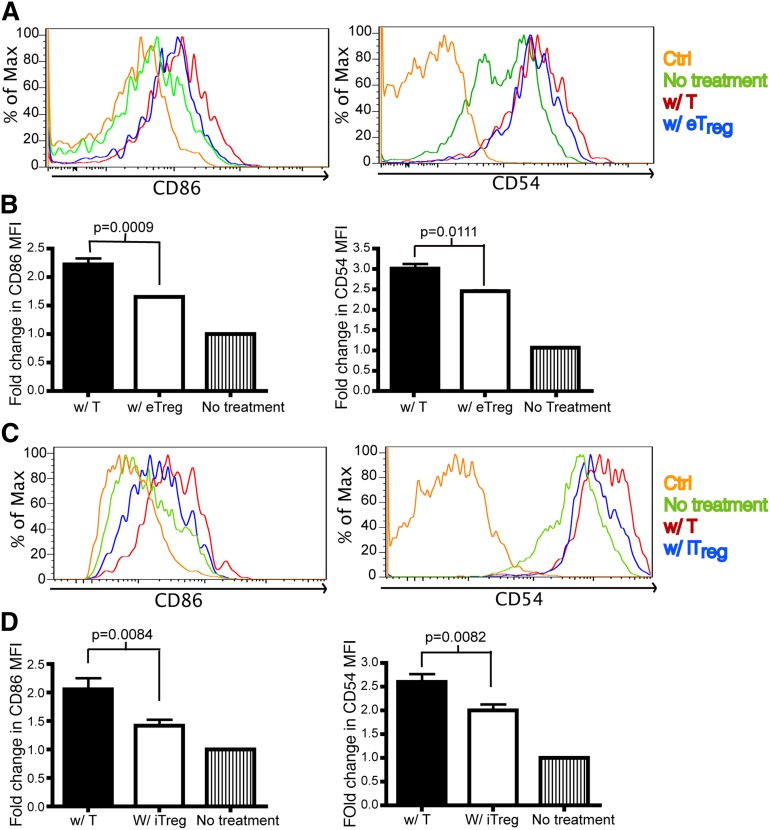

Both eTreg and iTreg decrease CD86 and CD54 on host DCs and diminish host DC number

One potential mechanism for the function of Tregs in vivo is to directly interact with Tcons to inhibit T-cell activation. To determine whether this is found in the allogeneic setting, we evaluated the interaction between Tcons and Tregs in the first 24 hours posttransplant. During this time frame, we were unable to find a significant interaction between these cells (supplemental Movie 7) that is consistent with the previous studies.33-35 Because we observed that Tregs interact with DCs in vivo, we investigated the expression of co-stimulatory molecules and molecules involved in synapse formation by host DCs after BMT. The molecules examined included CD80, CD86, CD40, CD54, CD70, B7-H3, and B7-H4. On day 1 after transplant, there was no difference in the expression of co-stimulatory molecules from DCs isolated from the spleen of mice transferred with Tcons or eTregs (data not shown). However, a modest statistically significant decrease was found in the expression of CD69 by both activated donor CD4+ and CD8+ Tcons in the presence of eTregs (data not shown). No difference on day 1 was found in the expression of CD25 or CD44 by donor T cells (data not shown). In contrast, on day 2 posttransplant, we found that DCs from recipient mice receiving eTregs had down-regulated CD86 and CD54 on host splenic DCs (Figure 6A-B). The transplantation of iTregs also reduced the expression of CD86 and CD54 on host DCs isolated from sLNs (Figure 6C-D). No differences were found in the other proteins evaluated. Evaluations past day 2 posttransplant could not be performed due to the paucity of host DCs present.

Figure 6.

Tregs down-regulate CD86 and CD54 on DCs. Flow analysis on DCs from skin-draining lymph nodes (sLNs) and spleens of recipient mice that were transplanted with T cells or eTregs or iTregs (with TCD BM) 1 day or 2 days prior to analysis. Ctrl: antibody isotype control. No treatment: mice were not irradiated or transplanted prior to evaluation. BM: mice were transplanted with BM only. W/ T: mice transplanted with donor T cells. W/ e Treg: mice transplanted with endogenous Treg. W/ iTregs: mice transplanted with iTregs. (A) The histogram of CD86 and CD54 expression on DCs from spleens of mice transplanted with T cells or eTregs 2 days posttransplant. (B) The fold change of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) for CD86 and CD54 on DCs was calculated by dividing the MFI of the specific staining antibody by the MFI of the control antibody. N = 3 to 4 mice per group (1 mouse for no treatment) with representative data from 2 different experiments. (C) The histogram of CD86 and CD54 expression on DCs from sLNs of mice transplanted with T cells or iTregs 1 day posttransplant. (D) MFI of CD86 and CD54 on DCs from (C). N = 3 to 4 mice per group (1 mouse for no treatment) with representative data from 2 different experiments. No difference was found in the expression of CD80, CD40, MHCII, B7H3, B7H4, or CD70 on DCs in the presence or absence of eTregs or iTregs (data not shown).

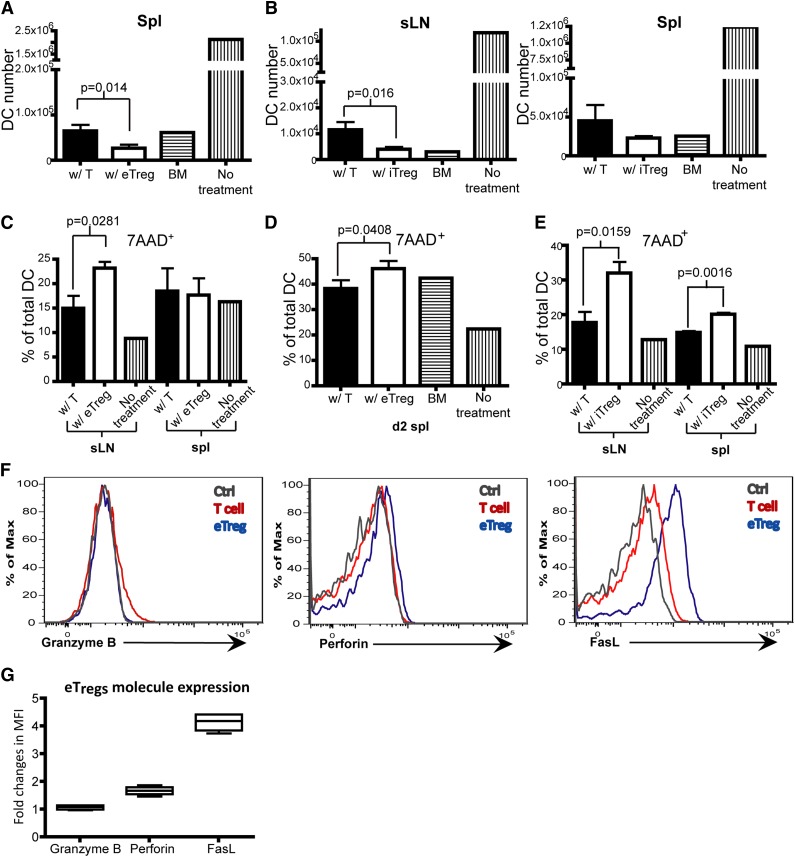

Interestingly, and somewhat unexpected, while evaluating the effect of Tregs on the expression of costimulatory molecules, we found that infusion of Tregs led to a decrease in the number of host DCs, compared with the infusion of Tcons. The average decrease in host DCs was 50% on day 2 after the infusion of eTregs or iTregs, compared with Tcons (Figure 7A-B). We then examined the death rate of DCs and found that the infusion of eTregs and iTregs induced a statistically significant increase in DCs expressing 7AAD 7-Aminoactinomycin D (7AAD) (Figure 7C-E). Endogenous Tregs in the recipient spleen expressed Fas ligand (FasL) and perforin (Figure 7F-G), whereas iTregs generated in vitro only expressed FasL (supplemental Figure 4). This suggests that 1 process by which host DCs were eliminated posttransplant was through Treg-mediated killing potentially via either FasL or perforin.36

Figure 7.

Tregs promote DC death. (A-G) Flow analysis on DCs from sLNs and spleens of recipient mice that were transplanted with T cells or eTregs or iTregs (with TCD BM) 1 day or 2 days prior to analysis. (A) Total DC number on day 2 in the spleen of mice transplanted with T cells or eTregs on day 2 posttransplant. (B) Total number of DCs on day 1 in sLNs and spleen of mice transplanted with T cells or iTregs. (C-E) The percentage of 7AAD+ DCs in total DCs from sLNs or the spleen of mice transplanted with T cells or eTregs on day 1 (C) or day 2 (spleen only) (D). (E) The percentage of 7AAD+ DCs of total DCs from sLNs or spleens of mice transplanted with T cells or iTregs on day 1. (F) Flow analysis of eTregs from spleens 3 days posttransplant. (G) Box plot of fold changes in MFI for granzyme B, perforin and FasL from eTregs. N = 3 to 4 mice per group (1 mouse for controls) with representative data from 2 different experiments.

Discussion

Allogeneic HSCT is the most effective cellular therapy for the treatment of specific malignant diseases. One of the significant complications that occur after allogeneic HSCT is the occurrence of acute GVHD.2,37 Multiple groups have shown that the interaction of donor T cells with host APCs is critical for the induction of acute GVHD.38-40 Here, we have evaluated this interaction in vivo using MPSLM. We found that donor allogeneic Tcons do not require a prolonged screening phase prior to specific stable interactions with host DCs. Tcons establish long contacts with DCs 2 hours after arrival in the LN. The time for stable contact duration between Tcons and DCs in this systemic model is approximately 20 to 24 hours. The frequency of long-term T cell–DC interactions is much lower at 24 hours after transplant, whereas alloantigens are still abundant, indicating that alloreactive T cells become refractory to further T-cell receptor stimulation after initial activation. We also found that eTregs and iTregs can significantly interrupt the interactions between Tcons and DCs, which has been observed for eTregs in organ-specific autoimmunity. When used as the sole population of T cells after HSCT, eTregs, iTregs, and Tcons have comparable interactions with host DCs. However, at later time points (>20 hours posttransplant), iTregs have lower velocity than the other 2 cell types, which is most likely due to their previous activation ex vivo. Finally, we have found that eTregs and iTregs down-regulate the expression of critical co-stimulatory and adhesion molecules by host DCs and induce host DC death.

A number of different groups have performed elegant experiments in pathogen-specific transgenic systems that defined the 3 phases of T-cell activation.3-5 The interpretation for the initial phase of short interaction between T cell and DCs was that this was needed for pathogen-specific T cells to sample APCs presenting the correct peptide:MHC complex for T-cell activation. Thus, 8 to 12 hours after this initial phase, pathogen-specific T cells have identified APCs presenting the correct peptide:MHC complex and engage in a prolonged period of contact necessary for T-cell activation. However, subsequent studies using high concentrations of antigen failed to detect an initial phase of transient interactions and instead visualized the formation of long-lived T cell–DC contacts very early in the response.6,7 Our study found that the majority of T cells were still in the lumen of the high endothelial venule of the LN at 1 to 2 hours after transplant (data not shown). Therefore, we started our analysis 2 hours after transplant. A subset of T cells, approximately 20% to 25% of the T cells imaged, maintained prolonged interactions with host APCs for more than 30 minutes starting 2 hours posttransplant (supplemental Figure 1b). Although the percentage of these long-interacting T cells increased to 25% to 30% from 2 hours to 3 hours, it indicated that the majority of alloreactive T cells had already established stable contact with DCs 2 hours after transplant. Thus, we were not able to demonstrate a distinct screening phase of transient interactions in the allogeneic setting. We believe that the absence of this screening phase is because alloreactive T cells can be activated by any APC. Our data support a paradigm for T-cell activation in the presence of antigen abundance, in which the scanning of APCs is not necessary.9 This finding would also explain why prophylactic drugs need to be present for a significant amount of time prior to the infusion of donor T cells, as the expansion of donor T cells occurs almost immediately after their infusion.

The infusion of Tregs has very quickly moved into the clinic, with multiple groups in the United States and abroad using this approach to prevent acute GVHD.18-20 Interestingly, this is being performed despite a limited understanding in regard to how these cells function in vivo. Our work suggests that Tregs use multiple mechanisms to prevent Tcons activation in vivo, centered on disruption of Tcon–DC interactions. DCs are potent APCs due to multiple factors, including the ability to take up antigen, the expression of co-stimulatory molecules critical for T-cell activation, and the generation of cytokines critical to polarizing a T-cell response.41 Our data indicate that the prolonged interaction of donor Tcons with host DCs is markedly diminished in the presence of donor eTregs or iTregs. We believe that this is one critical mechanism by which Tregs function in secondary lymphoid tissue to prevent acute GVHD. Interestingly, iTregs functioned better initially than eTregs, probably due to their prior activation ex vivo.

We found additionally that donor Tregs can reduce the expression of critical co-stimulatory and adhesion molecules, such as CD86 and CD54. It is interesting that previous investigations have identified CD28:CD80/CD86 and LFA-1:CD54 interactions as important for the generation of the immunological synapse.42 Therefore, one method by which Tregs could block Tcon activation is by altering proteins present in the immunological synapse and increasing the signaling threshold needed to activate Tcons. Our group is currently evaluating this hypothesis.

Another method we found that may be responsible for the function of Tregs is the induction of death of host DCs. Previously, Boissonnas et al36 evaluated the effect of Tregs on the viability of DCs from tumor-draining LNs. They found that reducing Treg numbers using anti-CD25 antibody or the administration of diphtheria toxin to FoxP3-DTR mice led to an increase in DCs. Death of DCs in this model was dependent on perforin expression by Tregs. Our data suggest that the administration of Tregs may lead to an early increase in the death of host DCs, consistent with Boissonnas et al’s36 previous finding. Our ex vivo studies indicate that iTregs and eTregs have significant expression of FAS ligand and more modestly, perforin, which may mediate the death of host DCs found in this study.

The fact that iTregs can interrupt Tcon–DC interaction better than eTregs early posttransplant demonstrates that they are intrinsically functional in vivo. It is advantageous to use these iTregs in human cellular therapy because they can be generated more easily and in larger numbers than eTregs. However, the inflammatory nature of GVHD may create an environment that is not conducive to maintaining the expression of FoxP3 by iTregs or support their survival over time. This would suggest that separating iTreg infusions from conditioning therapy may improve their function.

Finally, we showed that IL-10 is required for Treg-mediated disruption of Tcon–DC stable contacts. IL-10 has been shown to down-regulate co-stimulatory molecules on DCs, whereas IL-10 neutralization has shown no effect on T-cell activation in vitro when T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3.43 In addition, IL-10 deficiency or blockade had no effect on Treg-mediated suppression of T-cell proliferation in vitro when DCs were not present.28,44 Therefore, it is unlikely that IL-10 directly causes Tcons to decrease their interaction with DCs. One hypothesis consistent with these data is that IL-10 down-regulates CD54 and CD86 on DCs, preventing Tcons from forming stable contacts with DCs (supplemental Figure 5).

In summary, our findings shed new light on the activation of donor T cells by host APCs found after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. In addition, we have found that eTregs and iTregs use a number of different approaches to block the activation of donor T cells by altering the early interaction between host APC and donor T cell.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (RO1AI064363, RO1CA166794, RO1HL115761) (J.S.S.) (POIAI056299 and RO1HL56067) (B.R.B.), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS-180681) (J.S.S.), and a fellowship grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (LLS-226687) (K.L.L.).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: K.L.L. and J.S.S. conceived the studies and wrote the manuscript; K.L.L. performed experimental work and analyzed data M.L.W. and L.M.F. assisted in performing experiments; J.M.C., B.R.B., J.E.B., J.S.S., and M.B. assisted in analyzing data; J.M.C., B.R.B., and J.E.B. assisted in writing the manuscript; and N.A.T. and T.P.M. assisted in editing the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jonathan Serody, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, Room 22-044, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7295; e-mail: jonathan_serody@med.unc.edu.

References

- 1.Gratwohl A, Baldomero H. Trends of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in the third millennium. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16(6):420–426. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328330990f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shlomchik WD. Graft-versus-host disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(5):340–352. doi: 10.1038/nri2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, Von Andrian UH. T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature. 2004;427(6970):154–159. doi: 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller MJ, Hejazi AS, Wei SH, Cahalan MD, Parker I. T cell repertoire scanning is promoted by dynamic dendritic cell behavior and random T cell motility in the lymph node. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(4):998–1003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306407101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller MJ, Safrina O, Parker I, Cahalan MD. Imaging the single cell dynamics of CD4+ T cell activation by dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2004;200(7):847–856. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Celli S, Lemaître F, Bousso P. Real-time manipulation of T cell-dendritic cell interactions in vivo reveals the importance of prolonged contacts for CD4+ T cell activation. Immunity. 2007;27(4):625–634. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shakhar G, Lindquist RL, Skokos D, et al. Stable T cell-dendritic cell interactions precede the development of both tolerance and immunity in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(7):707–714. doi: 10.1038/ni1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei SH, Safrina O, Yu Y, Garrod KR, Cahalan MD, Parker I. Ca2+ signals in CD4+ T cells during early contacts with antigen-bearing dendritic cells in lymph node. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1586–1594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bousso P. T-cell activation by dendritic cells in the lymph node: lessons from the movies. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(9):675–684. doi: 10.1038/nri2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shevach EM. Regulatory T cells in autoimmmunity*. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:423-449. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):68–73. doi: 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsdell F. Foxp3 and natural regulatory T cells: key to a cell lineage? Immunity. 2003;19(2):165–168. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00207-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson MJ, Fulton LM, Coghill JM, et al. L-selectin is dispensable for T regulatory cell function postallogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(12):2596–2603. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coghill JM, Carlson MJ, Moran TP, Serody JS. The biology and therapeutic potential of natural regulatory T-cells in the bone marrow transplant setting. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(10):1860–1869. doi: 10.1080/10428190802272684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edinger M, Hoffmann P, Ermann J, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells preserve graft-versus-tumor activity while inhibiting graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation. Nat Med. 2003;9(9):1144–1150. doi: 10.1038/nm915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann P, Ermann J, Edinger M, Fathman CG, Strober S. Donor-type CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells suppress lethal acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. J Exp Med. 2002;196(3):389–399. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor PA, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Swedin JM, et al. L-Selectin(hi) but not the L-selectin(lo) CD4+25+ T-regulatory cells are potent inhibitors of GVHD and BM graft rejection. Blood. 2004;104(12):3804–3812. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunstein CG, Miller JS, Cao Q, et al. Infusion of ex vivo expanded T regulatory cells in adults transplanted with umbilical cord blood: safety profile and detection kinetics. Blood. 2011;117(3):1061–1070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-293795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Di Ianni M, Falzetti F, Carotti A, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(14):3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horch M, Nguyen VH. Regulatory T-cell immunotherapy for allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Ther Adv Hematol. 2012;3(1):29–44. doi: 10.1177/2040620711422266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hippen KL, Merkel SC, Schirm DK, et al. Generation and large-scale expansion of human inducible regulatory T cells that suppress graft-versus-host disease. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(6):1148–1157. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03558.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koenecke C, Czeloth N, Bubke A, et al. Alloantigen-specific de novo-induced Foxp3+ Treg revert in vivo and do not protect from experimental GVHD. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(11):3091–3096. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wysocki CA, Burkett SB, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Differential roles for CCR5 expression on donor T cells during graft-versus-host disease based on pretransplant conditioning. J Immunol. 2004;173(2):845–854. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Celli S, Bousso P. Intravital two-photon imaging of T-cell priming and tolerance in the lymph node. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;380:355-363. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Fulton LM, Carlson MJ, Coghill JM, et al. Attenuation of acute graft-versus-host disease in the absence of the transcription factor RORγt. J Immunol. 2012;189(4):1765–1772. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204(8):1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen W, Jin W, Hardegen N, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25- naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-beta induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198(12):1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyara M, Sakaguchi S. Natural regulatory T cells: mechanisms of suppression. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13(3):108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tawara I, Sun Y, Liu C, et al. Donor- but not host-derived interleukin-10 contributes to the regulation of experimental graft-versus-host disease. J Leukoc Biol. 2012;91(4):667–675. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1011510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Smedt T, Van Mechelen M, De Becker G, Urbain J, Leo O, Moser M. Effect of interleukin-10 on dendritic cell maturation and function. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27(5):1229–1235. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinbrink K, Wölfl M, Jonuleit H, Knop J, Enk AH. Induction of tolerance by IL-10-treated dendritic cells. J Immunol. 1997;159(10):4772–4780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koch F, Stanzl U, Jennewein P, et al. High level IL-12 production by murine dendritic cells: upregulation via MHC class II and CD40 molecules and downregulation by IL-4 and IL-10. J Exp Med. 1996;184(2):741–746. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mempel TR, Pittet MJ, Khazaie K, et al. Regulatory T cells reversibly suppress cytotoxic T cell function independent of effector differentiation. Immunity. 2006;25(1):129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tadokoro CE, Shakhar G, Shen S, et al. Regulatory T cells inhibit stable contacts between CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med. 2006;203(3):505–511. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang Q, Adams JY, Tooley AJ, et al. Visualizing regulatory T cell control of autoimmune responses in nonobese diabetic mice. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(1):83–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boissonnas A, Scholer-Dahirel A, Simon-Blancal V, et al. Foxp3+ T cells induce perforin-dependent dendritic cell death in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Immunity. 2010;32(2):266–278. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Socié G, Blazar BR. Acute graft-versus-host disease: from the bench to the bedside. Blood. 2009;114(20):4327–4336. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-204669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duffner UA, Maeda Y, Cooke KR, et al. Host dendritic cells alone are sufficient to initiate acute graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2004;172(12):7393–7398. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matte CC, Liu J, Cormier J, et al. Donor APCs are required for maximal GVHD but not for GVL. Nat Med. 2004;10(9):987–992. doi: 10.1038/nm1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy P, Maeda Y, Liu C, Krijanovski OI, Korngold R, Ferrara JL. A crucial role for antigen-presenting cells and alloantigen expression in graft-versus-leukemia responses. Nat Med. 2005;11(11):1244–1249. doi: 10.1038/nm1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedl P, den Boer AT, Gunzer M. Tuning immune responses: diversity and adaptation of the immunological synapse. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(7):532–545. doi: 10.1038/nri1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Del Prete G, De Carli M, Almerigogna F, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Romagnani S. Human IL-10 is produced by both type 1 helper (Th1) and type 2 helper (Th2) T cell clones and inhibits their antigen-specific proliferation and cytokine production. J Immunol. 1993;150(2):353–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sarangi PP, Sehrawat S, Suvas S, Rouse BT. IL-10 and natural regulatory T cells: two independent anti-inflammatory mechanisms in herpes simplex virus-induced ocular immunopathology. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6297–6306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.