Summary

The mitochondrial carriers play essential roles in energy metabolism. The short Ca2+-binding mitochondrial carrier (SCaMC) transports ATP-Mg in exchange for Pi and is important for activities that depend on adenine nucleotides. SCaMC adopts, in addition to the transmembrane domain (TMD) that transports solutes, an extramembrane N-terminal domain (NTD) that regulates solute transport in a Ca2+-dependent manner. Crystal structure of the Ca2+-bound NTD reveals a compact architecture in which the functional EF hands are sequestered by an endogenous helical segment. NMR relaxation rates indicated that removal of Ca2+ from NTD results in a major conformational switch from the rigid and compact Ca2+-bound state to the dynamic and loose apo state. Finally, we showed using surface plasmon resonance and NMR titration experiments that free apo NTD could specifically interact with liposome-incorporated TMD, but Ca2+ binding drastically weakened the interaction. Our results together provide a molecular explanation for Ca2+-dependent ATP-Mg flux in mitochondria.

Introduction

Mitochondrial matrix house essential components of energy metabolism in cell. Since the matrix are closed compartments, linking biochemical pathways of mitochondria and cytosol requires selective trafficking of metabolites, nucleotides, inorganic phosphates and vitamins across the mitochondrial inner membrane, and these transport activities are mediated by a large family of membrane proteins on the inner membrane, collectively termed mitochondrial carriers (Klingenberg, 2009; Palmieri et al., 2006; Walker and Runswick, 1993). Mitochondrial carriers adopt a range of transport modes including uniport, symport and antiport; their transport activities are driven by substrate concentration gradient and membrane potential across the inner membrane (Dehez et al., 2008; Kunji and Robinson, 2010; Palmieri et al., 2011). The structures of two family members have been characterized. The crystal structures of the ADP/ATP carrier (AAC) (Kunji and Harding, 2003; Pebay-Peyroula et al., 2003) and the NMR structure of the uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) (Berardi et al., 2011) all show an open-top container architecture formed with three structurally similar domains, and each domain consists of two packed transmembrane (TM) helices separated in sequence by an amphipathic helix. Based on sequence homology within the mitochondrial carrier family, other members are believed to have similar structural scaffolds (Palmieri et al., 2011).

There is, however, an unusual mitochondrial carrier that adopts, in addition to the transmembrane domain (TMD), an N-terminal domain (NTD) with Ca2+ binding signatures that extends beyond the membrane into the intermembrane space. This protein is the short Ca2+-binding mitochondrial carrier (SCaMC) that transports ATP-Mg in exchange for Pi and thereby modulates the matrix adenine nucleotide content (Satrustegui et al., 2007; Traba et al., 2011). SCaMC is one of the two carriers responsible for transporting ATP. While AAC accounts for the bulk ADP/ATP recycling in the matrix by exporting newly synthesized ATP out of the matrix while importing ADP for continuous synthesis (Traba et al., 2009b), the transport activity of SCaMC is important for mitochondrial activities that depend on adenine nucleotides, such as gluconeogenesis, mitochondrial biogenesis and mitochondrial DNA maintenance (Amigo et al., 2013; Cavero et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2011; Kucejova et al., 2008; Llorente-Folch et al., 2013; Satrustegui et al., 2007). SCaMC is abundant, and to date, five major paralogs have been identified, SCaMC-1/SLC25A24, SCaMC-2/SLC25A25, SCaMC-3/SLC25A23 (Bassi et al., 2005; del Arco and Satrustegui, 2004; Fiermonte et al., 2004; Mashima et al., 2003), SCaMC-1L (Amigo et al., 2012) and SCaMC-3L (Traba et al., 2009a), most of which have several alternative spliced variants (del Arco and Satrustegui, 2004). The major difference between SCaMC and AAC is the specific regulation of only SCaMC by Ca2+. Studies in isolated hepatocytes and mitochondria have reported that SCaMC remains inactive, unless stimulated by a cytosolic Ca2+ signal (Amigo et al., 2013; Chen, 2004; Dransfield and Aprille, 1993; Hagen et al., 1993; Nosek et al., 1990; Traba et al., 2012). The finding is consistent with SCaMC having a characteristic Ca2+ binding domain (Satrustegui et al., 2007).

It has been difficult to elucidate the role of the NTD in Ca2+-dependent transport activity because we have not seen a structural example illustrating how membrane transporter can be regulated by a covalently tethered ectodomain. Therefore, it is of fundamental interest to investigate the role of the SCaMC NTD in sensing Ca2+ and in interacting with the substrate-transporting TMD. Based on sequence analysis, the NTD contains four EF-hand motifs in a calmodulin-like arrangement, i.e., the N- and C-terminal lobes each consists of two EF hands with two Ca2+ binding loops (Hoeflich and Ikura, 2002). Calmodulin (CaM) is a ubiquitous Ca2+ sensor that is essential for numerous cellular Ca2+-regulated signaling pathways, including the function of several ion channels (Clapham, 2007; Van Petegem et al., 2005; Wingo et al., 2004). The overall Ca2+ triggered conformational switch is well understood for CaM. In the absence of Ca2+, four helices from two EF hands in each of the N- and C-lobes fold into a compact four-helix bundle in which hydrophobic residues of the helices are buried inside a hydrophobic core (Kuboniwa et al., 1995; Tjandra et al., 1995). Upon Ca2+ coordination by the Ca2+ binding loops, the EF-hand helices open up, exposing the hydrophobic residues (Chou et al., 2001). This conformational switch allows the EF hands to clamp onto their target peptides, as in the case of Ca2+-dependent activation of the myosin light chain kinase by CaM during muscle contraction (Ikura et al., 1992; Meador et al., 1992). In CaM, there is also a flexible linker connecting the N- and C-lobes, which permits the two domains to wrap around the same peptide (Barbato et al., 1992).

Although the SCaMC NTD also has four EF-hands, there does not appear to be a flexible central linker between the N- and C-lobes according to secondary structure prediction (del Arco and Satrustegui, 2004), and sequence analysis also predicted an additional C-terminal helix (Fig. S1). These predicted differences raised the question of whether the NTD adopts a Ca2+-dependent mode of action different from that of CaM. Moreover, it is still not clear whether the NTD interacts at all with the TMD.

In this study, we used a combination of X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and surface plasmon resonance (SPR) approaches to investigate Ca2+ triggered structural changes of human SCaMC-1 NTD and its interaction with the TMD. We showed that the NTD can undergo change from the dynamic apo state that specifically binds to the transporter domain to a rigid and compact structure upon Ca2+ binding, and this conformational switch essentially abrogates interaction with the substrate-transporting TMD.

Results

Structure determination

We attempted to determine the crystal structure of the human SCaMC-1 NTD in both apo and Ca2+-bound states. While the Ca2+-bound NTD could be crystallized, the apo state resisted extensive crystallization trials and was later found to be highly dynamic by NMR measurements. The Ca2+-bound NTD was crystallized in two different space groups, P6222 and P3121. Initial phase and structural model were obtained from the 2.9 Å multiple wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD) data collected on P6222 crystals of selenomethionine labeled protein (Doublie, 2007; Yang et al., 2011). We then used the model and solved the phase of the P3121 dataset by molecular replacement. The structure of the Ca2+-bound NTD in the P3121 crystal was subsequently refined to 2.1 Å with good statistics (R = 17.67%, Rfree = 22.53%; full statistics in Table 1). The construct that was successfully crystallized above consisted of residues 1–193. We included residues 156–193, a region of the NTD that is between the EF-hand-rich domain and the TMD, with the intention to examine its potential interaction with the EF hands (Fig. S2A). In the electron density map, however, only residues 22–176 were visible.

Table 1.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| SeMet peak | SeMet inflation | SeMet remote | Native | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PDB ID | 4N5X | |||

| Data collection | ||||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9794 | 0.9795 | 0.9494 | 1.5418 |

| Resolution (Å) | 40-2.9 (2.98-2.9) a | 40-2.92 (3.03-2.92) | 40-3.0 (3.1-3.0) | 20-2.1 (2.17-2.10) |

| Space group | P6222 | P6222 | P6222 | P3121 |

| Cell dimensions | ||||

| a= b(Å) | 74.480 | 74.489 | 74.503 | 51.210 |

| c (Å) | 173.637 | 173.650 | 173.709 | 112.153 |

| α= β (°) | 90 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| γ (°) | 120 | 120 | 120 | 120 |

| Total reflections | 260454 (20594) | 254334 (28333) | 235619 (23782) | 111675 (10536) |

| Unique reflections | 11865 (886) | 11613 (1220) | 10726 (1023) | 10443 (1013) |

| Redundancy | 21.6 (23.2) | 21.9 (23.2) | 21.9 (23.2) | 10.6 (10.4) |

| I/σI | 26.89 (5.09) | 27.95 (5.74) | 27.22 (5.69) | 21.96 (6.18) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.1 (100) | 99.0 (100) | 99.2 (100) | 100 (99.9) |

| Rmerge (%) | 8 (90.8) | 7.9 (80.7) | 8.1 (86.5) | 10.7 (40.0) |

| Phasing | ||||

| No. of SeMet sites | 4 | |||

| Figure of merit (AutoSol) | 0.58 | |||

| Refinement | ||||

| Resolution (Å) | 20-2.10 | |||

| No. reflections | 10443 | |||

| Rwork/Rfree (%)c | 17.67/22.53 b | |||

| R.m.s deviations | ||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.007 | |||

| Bond angles (°) | 1.151 | |||

| B-factors (Å2) | ||||

| SCaMC (Chain A) | 22.762 | |||

| Ca2+ (Chain B) | 18.742 | |||

| Water | 26.939 | |||

| Ramachandran plot statistics | ||||

| Most favored regions | 99.34% | |||

| Allowed regions | 0.66% | |||

| Disallowed regions | 0% | |||

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

Rmerge = S |I −<I>|/S I, where <I> is the average intensity from multiple observations of symmetry-related reflections.

Rwork and Rfree = Sh ||Fo| − |Fc||/Sh |Fo|, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes. Rfree was calculated with ~ 5% of the reflections not used in refinement.

The Ca2+-bound NTD has a compact structure with self-sequestered EF hands

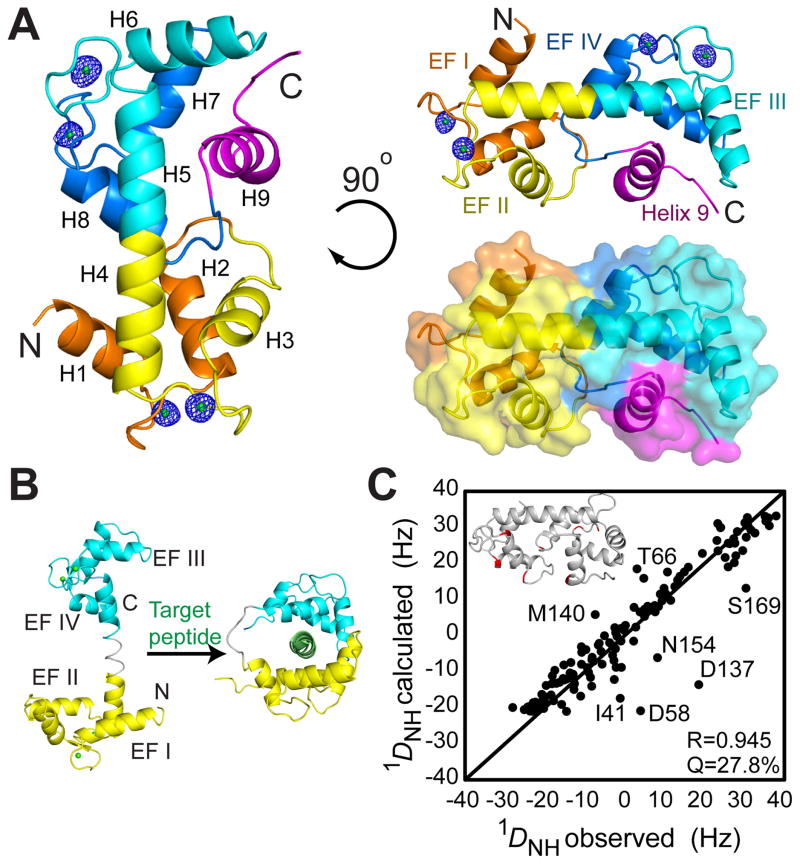

The crystal structure of the Ca2-bound NTD shows a rigid and elongated architecture that contains three main structured regions: the N-terminal lobe (residues 22–87) and the C-terminal lobe (residues 88–152), each consisting of two Ca2+-bound EF hands, and a C-terminal helix (residues 159–170) (Fig. 1A). All four EF hands have the typical EF-hand conformation as seen in the Ca2+-bound CaM, in which two α helices flank the canonical 12-residue Ca2+-coordinating loop (Gifford et al., 2007) (Fig. 1A). For each Ca2+-coordinating loop, the main chain carbonyl, side chain carboxylates and a bridged water molecule coordinate Ca2+ in a 7-fold pentagonal dipyramid fashion (Fig. S2B). The distances between two Ca2+ ions in the N- and C-lobes are 11.7 Å, and 11.9 Å, respectively; they are very similar to those in other EF-hand pairs (Gifford et al., 2007).

Figure 1. Structure of the Ca2+-bound NTD of human SCaMC-1 shows a self-sequestered CaM-like architecture.

(A) Cartoon and surface representations of the 2.1 Å crystal structure of the Ca2+-bound NTD. The NTD construct used for structure determination consists of residues 1–193, but electron density was observed only for residues 22–173. EF-hands are colored in orange, yellow, cyan, and blue. The extra helix (H9) after the CaM-like domain is colored in magenta. Ca2+ ions are represented by green sphere, and their simulated omit map are shown as blue mesh (contoured at 4 σ). See also Figure S2.

(B) Structures of the Ca2+-CaM with and without the bound peptide, shown for comparison with the NTD. Ca2+-CaM and Ca2+-CaM-peptide complexes are adapted from PDB: 4CLN and 2BBN, respectively. The N- and C-lobes are colored in yellow and cyan, respectively. The central flexible loop is in gray and the target peptide is in green.

(C) Correlation of 1DNH measured for Ca2+-bound NTD in solution to 1DNH values calculated based on the 2.1 Å crystal structure. The goodness of fit was accessed by Pearson correlation coefficient (R) and the quality factor (Q). The outliers with discrepancy between measured and calculated 1DNH larger than 10 Hz are mapped onto the structure of the Ca2+-bound NTD (Insert).

Despite the structural similarity in the N- and C-lobes between the Ca2+-bound NTD and CaM, the overall conformations are profoundly different. The Ca2+-bound NTD is rigid and compact whereas CaM adopts an extended dumbbell shape in which the N- and C-lobes are linked by a 6-residue flexible linker and are free to move relative to each other in solution (Barbato et al., 1992; Taylor et al., 1991) (Fig. 1B). For NTD, however, the flexible linker between the two lobes essentially does not exist. Consequently, the second helix of EF-hand II (H4) and the first helix of EF-hand III (H5) merge into a continuous central helix that bridges the N- and C-lobes (Fig. 1B). Unlike CaM, this central helix is short enough to allow the N- and C-lobes to be positioned in proximity to form extensive hydrogen bonds and non-polar contacts. Main interactions are those between the intervening loop (residues 51–59) connecting EF-hands I and II of N-lobe and the loop (residues 152–159) C-terminal to EF-hand IV of C-lobe (Fig. 1A). These interactions bury an interface of about 726 Å2, which accounts for more than 13% of the surface of the individual lobes. These inter-lobe contacts effectively lock the four EF hands in a compact fold while stabilizing the central helix.

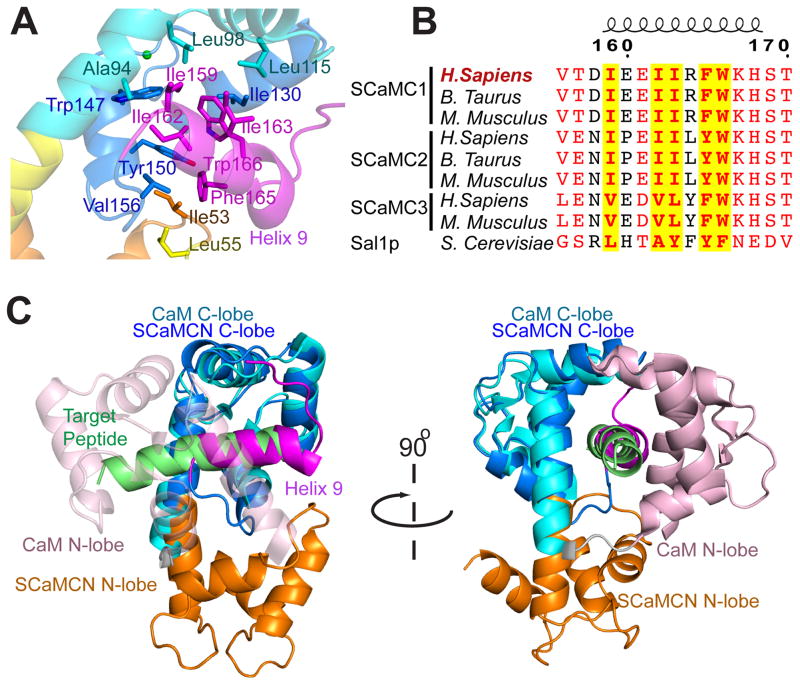

Another unusual and important feature of the NTD is the C-terminal helix (H9) in addition to the four EF hands. This helix encompasses a conserved sequence (residues 159 – 168) and forms extensive non-polar interactions with the hydrophobic clamps of EF-hands III and IV (Fig. 2A, 2B and S3). Hydrophobic clamps of EF-hands are binding sites for target peptides in CaM (Gifford et al., 2007). Indeed, the H9 in complex with the C-lobe in NTD aligns well with target peptide in several CaM-peptide complexes (Fig. 2C) (Hoeflich and Ikura, 2002), suggesting that it serves as an internal target peptide for the NTD EF-hands, similar to the sterile α motif (SAM) of the stromal interaction molecule (STIM) (Stathopulos et al., 2008; Zheng et al., 2011).

Figure 2. Helix-9 appears to be an intramolecular target peptide for the SCaMC EF hands.

(A) Detailed view of H9 interacting with EF-hands III & IV, showing the residues involved in the interaction. The color scheme used is the same as in Figure 1.

(B) Sequence alignment of H9 from SCaMC paralogs and homologs. Residues with more than 70% conservation are colored in red. The five hydrophobic residues involved in binding to the EF hands are highlighted in yellow. A more complete alignment is shown in Figure S3.

(C) Structure alignment between Ca2+-NTD and CaM-peptide complex. The N- and C-lobes of NTD are colored in orange and blue, respectively, whereas the CaM N- and C-lobes are in pink and cyan, respectively. The SCaMC-1 H9 (magenta) aligns well with the target peptide of CaM (green) in the CaM-peptide complex.

Due to the earlier example in which crystal packing caused the flexible central linker in the Ca2+-bound CaM to be helical, we had the concern that crystal contacts could also have artificially stabilized the compact state of SCaMC-1 NTD. We thus examined the structure of the Ca2+-bound NTD in solution. We measured the 1H-15N residual dipolar coupling (RDC) 1DNH, for Ca2+-bound NTD in a liquid crystalline medium composed of filamentous phage (Pf1). The measured 1DNH fitted the crystal structure well with Pearson correlation coefficient (R) of 0.945 and quality factor (Q) of 27.8% (Fig. 1C). The seven outliers with discrepancy larger than 10 Hz (e.g., residue 41, 58 and 137) are located in the loop regions and at the beginning of helices (Fig. 1C). The RDC data confirmed that the Ca2+-bound NTD in solution adopts the same structure as in crystal.

The apo NTD is distinctly more dynamic and less structured

To investigate potential Ca2+ triggered conformational change of SCaMC-1 NTD, we measured structural properties of the NTD in the absence of Ca2+ by NMR (Fig. 3). We attempted to crystallize the apo NTD but were not successful. We then found, during measurements of NMR relaxation rates, that the apo NTD has very substantial internal dynamics, which explains the unsuccessful crystallization trials. The 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectra of the apo and Ca2+-bound NTD are completely different (Fig. S4A), indicating that the structural and/or dynamic properties of the two states are very different and that Ca2+ binding clearly triggers a major conformational switch in the protein.

Figure 3. The apo NTD is more dynamic and less structured than Ca2+-bound NTD.

A, C, and E show the residue-specific heteronuclear 15N(1H) NOE, R2, and R1 values of the Ca2+-bound NTD, measured at 30 °C and 1H frequency of 750 MHz. The corresponding NOE and relaxation rates for the apo NTD are shown in B, D, and F. Secondary structure elements of the Ca2+-bound NTD are indicated above the plots. The color scheme used here is the same as in Figure 1A. See also Figure S1. (G) The flexible regions (15N(1H) NOE < 0.75) found in the apo NTD (salmon) are mapped onto the structure of the Ca2+-bound NTD, for showing regions of the Ca2+-bound NTD that become largely disordered in the absence of Ca2+. The unassigned residues (139–155) in the apo state are colored in blue.

We then compared the dynamic properties of the apo and Ca2+-bound NTD by measuring protein backbone 15N relaxation rates R1 and R2 and heteronuclear 15N(1H) NOE for both states. The relaxation data for the Ca2+-bound NTD is very uniform (except for N- and C-terminus) (Fig. 3A, 3C and 3E), which is indicative of a rigid and compact structure where the structured segments of the protein tumble together in solution. In contrast, the relaxation rates and the heteronuclear NOEs of the apo NTD are very heterogeneous (Fig. 3B, 3D and 3F). Regions that have low heteronuclear NOE values include H3 and adjacent loops (residues 50–78), the Ca2+-binding loop of EF-hand III (residues 99–109), as well as the C-terminal H9 (residues 159–170) (Fig. 3B and 3G). In particular, heteronuclear NOEs indicate that residues 50–78, which stabilize inter-lobe interactions in the Ca2+-bound state, are essentially disordered in the apo state (Fig. 3B and 3G). In addition to the disordered regions, the heteronuclear NOEs of the structured EF hands in the apo NTD are also uniformly lower than those in the Ca2+-bound NTD (Fig. 3A and 3B), indicating that the structured regions that remain in the apo state are also dynamic with respect to each other. These results together show that apo NTD does not adopt a defined conformation and that it is loosely packed and has significant amount of disordered regions.

The NTD binds specifically to the TMD in a Ca2+-dependent manner

The above structural characterization of SCaMC-1 NTD in the absence and presence of Ca2+ clearly show the existence of Ca2+ triggered conformational switch in NTD. To investigate whether NTD interacts with TMD and, if so, whether Ca2+ influences the interaction, we first used SPR to examine direct association of NTD to TMD in the absence and presence of Ca2+. The TMD of SCaMC-1 was over-expressed, purified and reconstituted in dodecyl-phosphocholine (DPC) micelles using a protocol similar to that used previously for another mitochondrial carrier UCP2 (Berardi et al., 2011), and further incorporated into POPC/POPG/cardiolipin liposome while removing detergent completely. The TMD proteoliposome was then immobilized onto the L1 sensor chip (Hodnik and Anderluh, 2010; Stahelin, 2013) for studying its interaction with NTD. The SPR measurements showed that the NTD could bind specifically to TMD proteoliposome with a KD of 250 ± 50 μM in the absence of Ca2+, and that the interaction is at least 20 fold lower in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+ (KD = 5600 ± 1000 μM) (Fig 4A and 4B). The binding affinity decreases as the Ca2+ concentration increases (with an apparent KD of 64.7 ± 18.8 μM). (Fig. 4C and 4D). Moreover, NTD did not bind to a proteoliposome incorporated with a bacterial homolog of the tryptophan-rich sensory protein (TSPO) expressed in the mitochondrial outer membrane, in either presence or absence of Ca2+ (Fig 5S). This further supports the specific interaction between NTD and TMD of SCaMC1.

Figure 4. The apo, but not the Ca2+-bound NTD binds specifically to TMD.

(A) SPR sensorgrams of the binding of NTD to immobilized TMD proteoliposomes at different NTD concentrations in the absence of Ca2+ (left) and in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+ (right).

(B) Binding isotherms derived from data in (A) determined KD of 250 ± 50 μM for the apo NTD and 5600 ± 1000 μM for the Ca2+-bound NTD. In this analysis, equilibrium signals at various NTD concentrations were plotted and fit with a single binding isotherm to determine KD. The KD values presented are mean ± SD, calculated from 3 independent measurements.

(C) SPR sensorgrams of the binding of 33 μM NTD, which does not contain EDTA, to the immobilized TMD proteoliposomes in the presence of 0, 3, 10, 30, 100, 300 and 1000 μM of Ca2+.

(D) Binding isotherms derived from data in (C) determined apparent KD of 64.7 ± 18.8 μM for Ca2+. In this analysis, the RU at 0 μMCa 2+ was used as a reference point and the change in RU (ΔRU) as compared to 0 μM Ca2+ for the rest of the data points were plotted and fit with a single binding isotherm to determine apparent KD. The KD values presented are mean ± SD, calculated from 2 independent measurements. See also Figure S5

(E) The 1H-15N TROSY-HSQC spectra of 0.1 mM apo NTD in the presence of empty liposomes (left) or 0.1 mM TMD incorporated proteoliposomes (right), both containing 20 mM total lipid. The majority of the peaks disappeared with the exception of the dynamic regions, residues 53–72 and 172–193.

(F) The same spectra as in (C) recorded for Ca2+-bound NTD, showing essentially no change in the presence of the TMD. See also Figure S4

We then examined NTD-TMD interaction using NMR with the attempt to map interactions between NTD and TMD-detergent complex. But, as indicated by our NMR spectra (Fig. S4B), the NTD is incompatible with the detergents we tested, i.e., it unfolded and/or aggregated at as low as 2 critical micelle concentration (CMC) of commonly used detergents including DDM, LDAO and DPC. On the other hand, when titrating with empty POPC/POPG/cardiolipin liposome, the NTD spectrum was unaffected (Fig. S4C and Fig. S4D), indicating that the protein does not interact with lipid bilayers. We thus investigated interaction between NTD and TMD proteoliposome by NMR. In the absence of Ca2+, titrating NTD with TMD proteoliposome caused drastic broadening of the NMR spectrum. Most resonances disappeared except those of flexible regions (Fig. 4E). This observation is expected. Due to the slow tumbling of the large proteoliposomes, NMR resonances of the regions of NTD that directly interact with the TMD are expected to severely broaden and vanish while those of disordered loops should still have sufficiently long T2 to be observed. More specifically, the remaining resonances correspond to highly dynamic regions including residues 53–72 and residues 172–193 (which connect NTD and TMD in the full-length SCaMC-1), whereas resonances for the structured regions disappeared. The results indicate that apo NTD could directly interact with certain regions of the TMD. In contrast, in the presence of Ca2+, NTD spectrum did not show any noticeable broadening upon the addition of TMD proteoliposomes (Fig. 4F), indicating that the Ca2+-bound structure of NTD does not support specific interaction with the TMD.

Discussion

The structural and functional data we have presented show that SCaMC NTD can undergo large conformational changes triggered by Ca2+ binding and this conformational switch may play a role in Ca2+-dependent regulation of the ATP-Mg transport activity of TMD. The crystal structure of the Ca2+-bound state of NTD shows a compact and rigid structure that appears to preclude the EF-hands from interacting with any target peptides. The compactness of the NTD is in striking difference with CaM in its Ca2+-bound form. For CaM, in the presence of Ca2+, the central linker adopts an extended form that separates N- and C-lobes (Chou et al., 2001). In the Ca2+-bound SCaMC-1 NTD, however, the corresponding central linker essentially does not exist, thus resulting in the formation of a continuous central helix that constitutively place the N- and C-lobes in proximity. In this conformation, the N-lobe EF-hands are preoccupied with interaction with the C-lobe EF-hand, while the otherwise exposed hydrophobic clamps of EF-hands III and IV are sequestered by H9 (Fig. 1A). Therefore, the Ca2+-bound NTD does not appear to be in a conformation capable of interacting with any peptide substrates and this is consistent with our NMR titration and SPR data that in the presence of Ca2+, NTD has very weak, if any, interactions with the liposome-incorporated TMD. The self-sequestered conformation above resembles the auto-regulation mechanism of the stromal interaction molecules (STIM), in which two EF-hands of STIM bind to an appended helix in the presence of Ca2+ to form a compact conformation and maintain its monomeric status (the inactive state) (Stathopulos et al., 2008). Depletion of Ca2+ from STIM leads to EF-hands conformational change and subsequent oligomerization (the active state) (Zheng et al., 2011).

In the absence of Ca2+, the NTD has drastically different structural properties than the Ca2+-bound state as indicated by the different NMR spectra and relaxation rates. Whereas the NMR relaxation rates for the Ca2+-bound state is uniform throughout most of the protein, it became very heterogeneous in the apo state (Fig. 3). The relaxation rates and heteronuclear NOE data indicated that residues 50–78 become essentially unfolded in the apo state. Moreover, the H9 has different relaxation properties as the EF-hand III and IV to which it binds in the Ca2+-bound state, indicating that in the apo-state this helix no longer interacts with the EF-hands. We did not observe resonances for residues 139–155, probably due to solvent exchange and/or exchange broadening. Since the interactions between residues 51–59 and 152–159 are the primary forces holding N- and C-lobes together, the unfolding of the above regions is expected to expose a large surface to bind TMD (Fig. 3G). Indeed, as demonstrated by our SPR measurements, the apo state of NTD could specifically bind to TMD reconstituted in liposomes (KD of ~ 250 μM), but the Ca2+-bound form did not. Furthermore, the dependence of interaction between NTD and TMD on Ca2+ (apparent KD of ~ 65 μM) is similar to the half-maximal activation [Ca2+] determined by Ca2+ activated ATP transport in mitochondria of COS-7 cell line (12 μM) (Traba et al., 2012) and in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (~ 20 μM) (Cavero et al., 2005; Traba et al., 2008). Although we were not able to determine a conformation representing the dynamic apo NTD, the NMR dynamics data clear indicate that the apo state is a much less compact, less structured, and more dynamic state.

Based on the above results, we propose that, in the absence of Ca2+, NTD acts as a cap that physically blocks substrate transport (Fig. 5). Although it is unusual that the apo, not the Ca2+-bound, EF hands represent the state responsible for target recognition, there are earlier precedence of apo CaM capable of binding target peptides of Myosine (Houdusse et al., 2006) and NaV (Chagot and Chazin, 2011; Wang et al., 2012) as part of its regulatory mechanism. The Ca2+-dependent capping/uncapping mechanism is in good agreement with previous functional observations. First, Ca2+ stimulates ATP import in the mitochondria of rat liver (Nosek et al., 1990), human Osteosarcoma cell lines 143B (Traba et al., 2012), and S. cerevisiae (Chen, 2004). Second, Ca2+ only alters ATP-Mg translocation rates, but not the binding affinity for ATP-Mg (Dransfield and Aprille, 1993; Tewari et al., 2012; Traba et al., 2008). Third, loss of the entire N-terminal domain leads to a constitutively active variant SCaMC-3L (Traba et al., 2009a), whereas Sal1p mutants with impaired Ca2+-binding displayed a defective ATP transport, possibly due to the inability to convert the apo to Ca2+-bound form (Chen, 2004). It is interesting from an evolutionary perspective that none of the SCaMC variants show any amino acid substitutions for the EF-hands (Satrustegui et al., 2007) as these variants would otherwise result in permanently inactivated SCaMC and thus impaired growth. It is also interesting that aspartate/glutamate carrier (AGC), another one of the two carriers that possess N-terminal CaM-like domain, is also activated by Ca2+ (Palmieri et al., 2001), and this carrier may use a similar capping/uncapping mechanism to regulate solute transport.

Figure 5. A proposed model for Ca2+-regulated ATP-Mg/Pi transport by SCaMC.

(A) In the absence of Ca2+, the NTD has a dynamic and loose conformation; it can specifically interact with and probably undergo conformational change and “cap” the intermembrane space side of the TMD. Apo form NTD is represented by the ellipsoid.

(B) In the presence of Ca2+, the NTD is in a compact and self-sequestered form that no longer interacts with the TMD. The “uncapping” allows solutes to be transported. The TMD structure was modeled after the crystal structure of the inhibited state of the ADP/ATP carrier (PDB ID: 1OKC).

Ca2+ is one of the most important secondary signaling messengers, involved in a wide range of physiological regulations. But adoption of a CaM-like Ca2+-sensing domain by a membrane transporter to directly regulate its transport activity is unusual. The voltage-gated Na+ channels (Shah et al., 2006) and the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (Johny et al., 2013) are among the few ion channels that use covalently tethered EF-hand motifs for mediating Ca2+ regulation of channel activity, but such regulation also requires inter-molecular interaction with CaM (Chagot and Chazin, 2011; Johny et al., 2013; Van Petegem et al., 2005). To the best of our knowledge, SCaMC and AGC are the only two transporters known thus far that use a covalently linked domain to regulate transport activities in a Ca2+-dependent manner (del Arco and Satrustegui, 2004; Palmieri et al., 2001). This unusual structural feature entitles SCaMC important role in the regulation of energy metabolism. Since SCaMC NTD is in the intermembrane space, it senses cytosolic Ca2+ concentration fluctuation and can transmit Ca2+ signal without the need to transport Ca2+ into the matrix. This provides an indirect Ca2+ signaling pathway in additional to those require the import of Ca2+ into the matrix, e.g., the mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter (MCU) mediated pathway (Baughman et al., 2011). In accordance with the role of Ca2+ as signal for increased energy requirements, Ca2+ binding to NTD releases auto-inhibition of SCaMC, which leads to increased matrix adenine nucleotide content and subsequently stimulates oxidative phosphorylation (Amigo et al., 2013). Knockout of SCaMC gene in mice resulted in lower cellular ATP levels, reduced physical endurance and metabolic efficiency (Anunciado-Koza et al., 2011).

In conclusion, we have shown that the extra-membrane NTD of SCaMC-1 undergoes a large structural change triggered by Ca2+ binding and this conformational switch directly impact its ability to interact with the TMD as a part of Ca2+ regulation of ATP-Mg transport. In the absence of Ca2+, NTD is partially unfolded in solution and binds specifically to TMD, whereas in the presence of Ca2+ it adopts a rigid and compact structure that largely abrogates TMD binding. An unexpected feature of the Ca2+-bound state was a C-terminal helix that appeared to serve as an endogenous inhibitory domain that sequesters the EF-hands from target interaction. Our structural and biochemical data, together with earlier functional results of Ca2+-induced activation of ATP-Mg transport of SCaMC, suggests a capping mechanism of SCaMC by which the apo NTD caps the TMD channel from the intermembrane space of mitochondria and blocks substrate transport, whereas Ca2+ binding convert NTD to a self-sequestered form that uncaps the channel. While this model remains to be tested by further structural investigations of the NTD-TMD complex, it represents a significant step towards the structural basis of Ca2+ regulation of ATP-Mg transport by the SCaMC transporters.

Experimental Procedures

X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy

Human SCaMC-1 NTD (residues 1–193) was expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells and purified with cobalt resin and a Superdex S75 size exclusion column. The purified NTD fraction was in the Ca2+-bound form. The apo form of NTD was obtained by extensive dialysis against buffer containing EDTA. The Ca2+-bound NTD was crystallized in two forms with space groups P6222 and P3121. Attempts to crystallize NTD in the absence of Ca2+ were unsuccessful. The 1H-15N RDCs of the Ca2+-bound NTD were measured using 15N-labeled protein weakly aligned in filamentous phage Pf1. Relaxation rates 15N R1 and R2, and 15N(1H) NOE for apo and Ca2+-bound NTD were measured using the standard pulse schemes described previously (Kay et al., 1989). Details of data collection and analysis are provided in SI text.

Proteoliposome binding measurements

TMD (residues 185–477) was expressed in BL21 (DE3) cells and purified using a protocol similar to that previously reported (Berardi et al., 2011). TMD proteoliposome is prepared as described in SI text. The liposome is composed of POPC, POPG and cardiolipin at 4:1:0.1 molar ratio. The final proteoliposome solution contained 40 mM total lipid and 0.2 mM TMD for NMR experiments, or 0.5 mM total lipid and 2.5 μM TMD for SPR experiments. Empty liposomes were prepared in the same way without the protein. For NMR measurements of NTD-TMD interaction, 0.2 mM 15N-labeled NTD in the NMR buffer was mixed with equal volume of either TMD proteoliposome or empty liposome solution above.

SPR experiments were performed using a protocol similar to that described previously (Hodnik and Anderluh, 2010; Stahelin, 2013). TMD proteoliposomes or empty liposomes were immobilized in active flow cell or control flow cell of L1 sensor chip, respectively. To measure binding, apo or Ca2+ bound NTD were injected at increasing concentrations and the responses in signal (RU) were recorded. Sensorgrams were corrected for changes in the refractive index of the buffer and non-specific binding by subtracting the response of the control flow cell with immobilized empty liposomes. Equilibrium signal (Req) at a given NTD concentration (C) were plotted and fit to the equation Req = Rmax/(1 + KD/C) to determine the equilibrium binding constant (KD). Rmax is the binding signal at saturation. More details are provided in SI text.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

High resolution structure of a calcium sensing domain that regulates Mg-ATP carrier

Described the dynamic conformational switch of the calcium sensing domain

Identified the state of the calcium sensing domain that binds to the transporter

Proposed a model for calcium regulation of Mg-ATP transport

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Chou Lab for technical assistance and insightful discussions, Dr. Kirill Oxenoid for TSPO protein and Dr. Yu Chen (Harvard Medical School) for X-ray data collection. S.B is a recipient of an Erwin Schrödinger postdoctoral fellowship of the Austrian Science Fund (FWF, J3251). This work was supported by NIH Grant GM094608 (to J.J.C.).

Footnotes

Accession number

Coordinates of Ca2+-bound SCaMC-1 NTD have been deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank under the accession code 4N5X.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amigo I, Traba J, Gonzalez-Barroso MM, Rueda CB, Fernandez M, Rial E, Sanchez A, Satrustegui J, Del Arco A. Glucagon Regulation of Oxidative Phosphorylation Requires an Increase in Matrix Adenine Nucleotide Content through Ca2+ Activation of the Mitochondrial ATP-Mg/Pi Carrier SCaMC-3. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:7791–7802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amigo I, Traba J, Satrustegui J, Del Arco A. SCaMC-1Like a Member of the Mitochondrial Carrier (MC) Family Preferentially Expressed in Testis and Localized in Mitochondria and Chromatoid Body. PloS one. 2012;7:e40470. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anunciado-Koza RP, Zhang J, Ukropec J, Bajpeyi S, Koza RA, Rogers RC, Cefalu WT, Mynatt RL, Kozak LP. Inactivation of the mitochondrial carrier SLC25A25 (ATP-Mg2+/Pi transporter) reduces physical endurance and metabolic efficiency in mice. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:11659–11671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.203000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato G, Ikura M, Kay LE, Pastor RW, Bax A. Backbone dynamics of calmodulin studied by 15N relaxation using inverse detected two-dimensional NMR spectroscopy: the central helix is flexible. Biochemistry. 1992;31:5269–5278. doi: 10.1021/bi00138a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi MT, Manzoni M, Bresciani R, Pizzo MT, Della Monica A, Barlati S, Monti E, Borsani G. Cellular expression and alternative splicing of SLC25A23, a member of the mitochondrial Ca2+-dependent solute carrier gene family. Gene. 2005;345:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baughman JM, Perocchi F, Girgis HS, Plovanich M, Belcher-Timme CA, Sancak Y, Bao XR, Strittmatter L, Goldberger O, Bogorad RL, et al. Integrative genomics identifies MCU as an essential component of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter. Nature. 2011;476:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nature10234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berardi MJ, Shih WM, Harrison SC, Chou JJ. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 structure determined by NMR molecular fragment searching. Nature. 2011;476:109–113. doi: 10.1038/nature10257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavero S, Traba J, Del Arco A, Satrustegui J. The calcium-dependent ATP-Mg/Pi mitochondrial carrier is a target of glucose-induced calcium signalling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Biochemical journal. 2005;392:537–544. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagot B, Chazin WJ. Solution NMR structure of Apo-calmodulin in complex with the IQ motif of human cardiac sodium channel NaV1.5. Journal of molecular biology. 2011;406:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen XJ. Sal1p, a calcium-dependent carrier protein that suppresses an essential cellular function associated With the Aac2 isoform of ADP/ATP translocase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2004;167:607–617. doi: 10.1534/genetics.103.023655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Chou HC, Lyu PC, Yin HS, Huang FL, Chang WS, Fan CY, Tu IF, Lai TC, Lin ST, et al. Mitochondrial proteomics analysis of tumorigenic and metastatic breast cancer markers. Functional & integrative genomics. 2011;11:225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10142-011-0210-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou JJ, Li S, Klee CB, Bax A. Solution structure of Ca(2+)-calmodulin reveals flexible handlike properties of its domains. Nature structural biology. 2001;8:990–997. doi: 10.1038/nsb1101-990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham DE. Calcium signaling. Cell. 2007;131:1047–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehez F, Pebay-Peyroula E, Chipot C. Binding of ADP in the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier is driven by an electrostatic funnel. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:12725–12733. doi: 10.1021/ja8033087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Arco A, Satrustegui J. Identification of a novel human subfamily of mitochondrial carriers with calcium-binding domains. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:24701–24713. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doublié S. Production of selenomethionyl proteins in prokaryotic and eukaryotic expression systems. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;363:91–108. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-209-0_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dransfield DT, Aprille JR. Regulation of the mitochondrial ATP-Mg/Pi carrier in isolated hepatocytes. The American journal of physiology. 1993;264:C663–670. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.3.C663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiermonte G, De Leonardis F, Todisco S, Palmieri L, Lasorsa FM, Palmieri F. Identification of the mitochondrial ATP-Mg/Pi transporter. Bacterial expression, reconstitution, functional characterization, and tissue distribution. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:30722–30730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford JL, Walsh MP, Vogel HJ. Structures and metal-ion-binding properties of the Ca2+-binding helix-loop-helix EF-hand motifs. The Biochemical journal. 2007;405:199–221. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen T, Joyal JL, Henke W, Aprille JR. Net adenine nucleotide transport in rat kidney mitochondria. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1993;303:195–207. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodnik V, Anderluh G. Capture of intact liposomes on biacore sensor chips for protein-membrane interaction studies. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;627:201–211. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-670-2_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeflich KP, Ikura M. Calmodulin in action: diversity in target recognition and activation mechanisms. Cell. 2002;108:739–742. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houdusse A, Gaucher JF, Krementsova E, Mui S, Trybus KM, Cohen C. Crystal structure of apo-calmodulin bound to the first two IQ motifs of myosin V reveals essential recognition features. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:19326–19331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609436103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikura M, Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Zhu G, Klee CB, Bax A. Solution structure of a calmodulin-target peptide complex by multidimensional NMR. Science. 1992;256:632–638. doi: 10.1126/science.1585175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johny MB, Yang PS, Bazzazi H, Yue DT. Dynamic switching of calmodulin interactions underlies Ca(2+) regulation of CaV1.3 channels. Nature communications. 2013;4:1717. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay LE, Torchia DA, Bax A. Backbone dynamics of proteins as studied by 15N inverse detected heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy: application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8972–8979. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg M. Cardiolipin and mitochondrial carriers. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1788:2048–2058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuboniwa H, Tjandra N, Grzesiek S, Ren H, Klee CB, Bax A. Solution structure of calcium-free calmodulin. Nature structural biology. 1995;2:768–776. doi: 10.1038/nsb0995-768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucejova B, Li L, Wang X, Giannattasio S, Chen XJ. Pleiotropic effects of the yeast Sal1 and Aac2 carriers on mitochondrial function via an activity distinct from adenine nucleotide transport. Molecular genetics and genomics: MGG. 2008;280:25–39. doi: 10.1007/s00438-008-0342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunji ER, Harding M. Projection structure of the atractyloside-inhibited mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:36985–36988. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunji ER, Robinson AJ. Coupling of proton and substrate translocation in the transport cycle of mitochondrial carriers. Current opinion in structural biology. 2010;20:440–447. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llorente-Folch I, Rueda CB, Amigo I, Del Arco A, Saheki T, Pardo B, Satrustegui J. Calcium-Regulation of Mitochondrial Respiration Maintains ATP Homeostasis and Requires ARALAR/AGC1-Malate Aspartate Shuttle in Intact Cortical Neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2013;33:13957–13971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0929-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashima H, Ueda N, Ohno H, Suzuki J, Ohnishi H, Yasuda H, Tsuchida T, Kanamaru C, Makita N, Iiri T, et al. A novel mitochondrial Ca2+-dependent solute carrier in the liver identified by mRNA differential display. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:9520–9527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m208398200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meador WE, Means AR, Quiocho FA. Target enzyme recognition by calmodulin: 2.4 A structure of a calmodulin-peptide complex. Science. 1992;257:1251–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.1519061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek MT, Dransfield DT, Aprille JR. Calcium stimulates ATP-Mg/Pi carrier activity in rat liver mitochondria. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265:8444–8450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri F, Agrimi G, Blanco E, Castegna A, Di Noia MA, Iacobazzi V, Lasorsa FM, Marobbio CM, Palmieri L, Scarcia P, et al. Identification of mitochondrial carriers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by transport assay of reconstituted recombinant proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1757:1249–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri F, Pierri CL, De Grassi A, Nunes-Nesi A, Fernie AR. Evolution, structure and function of mitochondrial carriers: a review with new insights. The Plant journal: for cell and molecular biology. 2011;66:161–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri L, Pardo B, Lasorsa FM, del Arco A, Kobayashi K, Iijima M, Runswick MJ, Walker JE, Saheki T, Satrustegui J, et al. Citrin and aralar1 are Ca(2+)-stimulated aspartate/glutamate transporters in mitochondria. The EMBO journal. 2001;20:5060–5069. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebay-Peyroula E, Dahout-Gonzalez C, Kahn R, Trezeguet V, Lauquin GJ, Brandolin G. Structure of mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier in complex with carboxyatractyloside. Nature. 2003;426:39–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satrustegui J, Pardo B, Del Arco A. Mitochondrial transporters as novel targets for intracellular calcium signaling. Physiological reviews. 2007;87:29–67. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah VN, Wingo TL, Weiss KL, Williams CK, Balser JR, Chazin WJ. Calcium-dependent regulation of the voltage-gated sodium channel hH1: intrinsic and extrinsic sensors use a common molecular switch. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:3592–3597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507397103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahelin RV. Surface plasmon resonance: a useful technique for cell biologists to characterize biomolecular interactions. Molecular biology of the cell. 2013;24:883–886. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopulos PB, Zheng L, Li GY, Plevin MJ, Ikura M. Structural and mechanistic insights into STIM1-mediated initiation of store-operated calcium entry. Cell. 2008;135:110–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DA, Sack JS, Maune JF, Beckingham K, Quiocho FA. Structure of a recombinant calmodulin from Drosophila melanogaster refined at 2.2-A resolution. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:21375–21380. doi: 10.2210/pdb4cln/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tewari SG, Dash RK, Beard DA, Bazil JN. A biophysical model of the mitochondrial ATP-Mg/P(i) carrier. Biophysical journal. 2012;103:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.08.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tjandra N, Kuboniwa H, Ren H, Bax A. Rotational dynamics of calcium-free calmodulin studied by 15N-NMR relaxation measurements. European journal of biochemistry/FEBS. 1995;230:1014–1024. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traba J, Del Arco A, Duchen MR, Szabadkai G, Satrustegui J. SCaMC-1 promotes cancer cell survival by desensitizing mitochondrial permeability transition via ATP/ADP-mediated matrix Ca(2+) buffering. Cell death and differentiation. 2012;19:650–660. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traba J, Froschauer EM, Wiesenberger G, Satrustegui J, Del Arco A. Yeast mitochondria import ATP through the calcium-dependent ATP-Mg/Pi carrier Sal1p, and are ATP consumers during aerobic growth in glucose. Molecular microbiology. 2008;69:570–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traba J, Satrustegui J, del Arco A. Characterization of SCaMC-3-like/slc25a41, a novel calcium-independent mitochondrial ATP-Mg/Pi carrier. The Biochemical journal. 2009a;418:125–133. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traba J, Satrustegui J, del Arco A. Transport of adenine nucleotides in the mitochondria of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: interactions between the ADP/ATP carriers and the ATP-Mg/Pi carrier. Mitochondrion. 2009b;9:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traba J, Satrustegui J, del Arco A. Adenine nucleotide transporters in organelles: novel genes and functions. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS. 2011;68:1183–1206. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0612-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Petegem F, Chatelain FC, Minor DL., Jr Insights into voltage-gated calcium channel regulation from the structure of the CaV1.2 IQ domain-Ca2+/calmodulin complex. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2005;12:1108–1115. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker JE, Runswick MJ. The mitochondrial transport protein superfamily. Journal of bioenergetics and biomembranes. 1993;25:435–446. doi: 10.1007/BF01108401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Chung BC, Yan H, Lee SY, Pitt GS. Crystal structure of the ternary complex of a NaV C-terminal domain, a fibroblast growth factor homologous factor, and calmodulin. Structure. 2012;20:1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo TL, Shah VN, Anderson ME, Lybrand TP, Chazin WJ, Balser JR. An EF-hand in the sodium channel couples intracellular calcium to cardiac excitability. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2004;11:219–225. doi: 10.1038/nsmb737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q, Coseno M, Gilmartin GM, Doublié S. Crystal structure of a human cleavage factor CFI(m)25/CFI(m)68/RNA complex provides an insight into poly(A) site recognition and RNA looping. Structure. 2011;19:368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L, Stathopulos PB, Schindl R, Li GY, Romanin C, Ikura M. Auto-inhibitory role of the EF-SAM domain of STIM proteins in store-operated calcium entry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:1337–1342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015125108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.