Abstract

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), caused by the commensal fungus Candida albicans, is an opportunistic infection associated with infancy, AIDS and IL-17-related primary immunodeficiencies. The Th17-associated cytokines IL-23 and IL-17 are crucial for immunity to OPC, but the mechanisms by which they mediate immunity are poorly defined. IL-17RA-deficient humans and mice are strongly susceptible to OPC, with reduced levels of CXC chemokines and concomitantly impaired neutrophil recruitment to the oral mucosa. Paradoxically, humans with isolated neutropenia are typically not susceptible to candidiasis. To determine whether immunity to OPC is mediated via neutrophil recruitment, mice lacking CXCR2 were subjected to OPC, and were found to be highly susceptible, although there was no dissemination of fungi to peripheral organs. To assess whether the entire neutrophil response is IL-17-dependent, IL-17RA−/− and IL-23−/− mice were administered neutrophil-depleting antibodies and subjected to OPC. These mice displayed increased oral fungal burdens compared to IL-17RA−/− or IL-23−/− mice alone, indicating that additional IL-17-independent signals contribute to the neutrophil response. WT mice treated with anti-Gr-1 antibodies exhibited a robust infiltrate of CD11b+Ly-6GlowF4/80− cells to the oral mucosa, but were nonetheless highly susceptible to OPC, indicating that this monocytic influx is insufficient for host defense. Surprisingly, Ly-6G antibody treatment did not induce the same strong susceptibility to OPC in WT mice. Thus, CXCR2+ and Gr-1+ neutrophils play a vital role in host defense against OPC. Moreover, defects in the IL-23/17 axis cause a potent but incomplete deficiency in the neutrophil response to oral candidiasis.

Keywords: Neutrophils, mucosal candidiasis, IL-17, IL-23, Th17

Introduction

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC, thrush) is an opportunistic mucosal infection caused by the commensal fungus Candida albicans. C. albicans causes disease when exposure is combined with host susceptibility through immunodeficiency or a breach in normal barriers. A range of primary and secondary immunodeficiency syndromes are associated with susceptibility to OPC (1, 2), including the primary immunodeficiency Hyper-IgE syndrome and a family of genetic diseases leading to chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) (3). Secondary immunodeficiencies are now the most common predisposing factor for mucosal Candida disease. OPC is well described in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and is considered an AIDS-defining illness. Cancer chemotherapy, immunosuppression for transplant recipients, renal failure and high-dose corticosteroids increase the risk of candidiasis.

T cells, specifically the Th17 subset of CD4+ T helper cells, play a central role in resistance to OPC (4–6). Th17 cells secrete IL-17 (IL-17A), a pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in defense against extracellular pathogens (7, 8). Previous studies have shown that mice deficient in the IL-17 receptor (IL-17RA or IL-17RC) and IL-23 (required for the expansion of the Th17 cell subset) exhibit dramatic susceptibility to OPC (4, 9).

The mechanisms of host defense induced by IL-17 are not fully understood, but appear to be mediated by the secretion of antimicrobial peptides and recruitment of neutrophils through chemotactic chemokines and granulopoietic cytokines. A role for neutrophils in OPC has been inferred based on the observation of neutrophil influx into the tongue after oral Candida infection (4). Mice subjected to OPC show an increased expression of genes associated with neutrophil regulation, including granulopoietic cytokines G-CSF and IL-6 and chemokines CXCL1 (KC, Groα), CXCL2 (MIP-2) and CXCL5 (LIX) (4, 10). Moreover, neutrophil recruitment to tissue is markedly attenuated in mice deficient in IL-17 signaling, thus linking IL-17 to neutrophil function and susceptibility to OPC (4, 9). Strikingly, recent reports of single gene defects in humans resulting in CMC cluster in the IL-17 pathway, including mutations in IL-17RA, IL-17F and Act1, an adaptor molecule mediating IL-17 signaling (3, 11, 12).

The requirement for neutrophils in host defense from disseminated candidiasis is well described (13, 14). However, the role of neutrophils in host defense at the oral mucosa is less clear. Patients with broad immunosuppression that includes neutropenia are typically susceptible to OPC, as are those with hereditary myeloperoxidase deficiency with defects in neutrophil and macrophage activity. However, oral thrush is not frequently reported in patients with isolated neutropenia (15–17), raising the question of whether the effect of IL-17 on OPC susceptibility is solely or primarily due to its impact on neutrophils.

There is no knockout mouse system to study profound neutropenia, but alternate tools are available to examine the role of neutrophil recruitment and effector responses. Neutrophils, characterized by expression of Ly-6G (a component of the Gr-1 epitope), are regulated through the chemokine receptor CXCR2 (18–20). Neutrophils are the predominant CXCR2+ cell among blood leukocytes, with lower expression on mast cells, monocytes, macrophages, endothelial and epithelial cells (21–23). In addition, several antibodies (anti-Ly-6G and anti-Gr-1) are available to deplete neutrophils peripherally, albeit with variable degrees of efficiency in tissue and cell type specificity (24–27). To test the hypothesis that neutrophils are essential in host defense from OPC, we evaluated disease in CXCR2−/− mice and antibody-mediated neutrophil depletion. In addition, we assessed redundancy in host defense systems with neutrophil depletion in mice deficient in IL-23 or IL-17RA. Our findings indicate a central role for CXCR2 and Gr-1+ neutrophils in the oral mucosa.

Materials and methods

Mice

IL-23p19−/− mice were provided by Genentech (South San Francisco, CA) and IL-17RA−/− mice by Amgen (Seattle, WA) and bred in-house. All other mice were from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Habor, ME) on the C57BL/6 background unless noted. Mice were 6–9 weeks old, age- and sex-matched for all experiments unless noted. Protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and adhered to guidelines in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH.

Antibody-mediated neutrophil depletion

Mice were injected intraperitoneally (IP) with monoclonal antibody (Mab) 24 h prior to and 2 d after inoculation with C. albicans (Day 0). Anti-Ly-6G (clone 1A8, Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH) and isotype control (clone 2A3, Bio X Cell) were administered at a dose of 300 μg. Anti-Gr-1 (clone RB6-8C5, Bio X Cell) and isotype control (clone LTF-2, Bio X Cell) were administered at a dose of 80 μg. All cohorts not receiving Mab were treated with PBS. The degree of neutrophil depletion was assessed in peripheral blood as follows: blood was collected by saphenous venous puncture or cardiac puncture and anti-coagulated in EDTA-containing tubes (Microvette Tubes, Sarstedt, Newton, NC and Microtainer Tubes, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Total white blood cell counts (WBC) were determined by visual enumeration after trypan blue exclusion. The percentage of neutrophils was determined by enumeration of a blood smear stained with Giemsa (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ). 100–200 cells were counted per sample. The absolute neutrophil count (ANC) was determined by multiplying the percentage of neutrophils (mature and band forms) by total WBC.

Mouse model of OPC

OPC was performed as described (4, 28). In brief, mice were inoculated under anesthesia by placing a 0.0025-g cotton ball saturated in a 2 × 107 CFU/ml C. albicans suspension (strain CAF2-1) sublingually for 75 min. Sham-inoculated mice were inoculated with a cotton ball saturated with sterile PBS. The oral cavity was swabbed immediately before each infection and streaked on yeast peptone dextrose (YPD) agar to verify the absence of Candida. No antibiotics were administered. If indicated, control mice were immunosuppressed with cortisone acetate 225 mg/kg (Sigma-Aldrich) on days −1, 1 and 3. Mice were weighed daily and weight compared to baseline weight on day −1. Fungal burden in the indicated organs was determined by dissociation on a GentleMACS Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) followed by plating serial dilutions on YPD with antibiotics (ampicillin, gentamicin). Plates were incubated for 48 hours at 30°C followed by colony enumeration in triplicate.

Flow cytometry

Tongue tissue was processed with an enzyme cocktail [EDTA, HEPES, collagenase-2 (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood NJ), dispase (Gibco, Invitrogen), DNase I (Applied Biochemical) and defined trypsin inhibitor (Gibco)]. Tissue was mechanically homogenized and passed through a cell strainer to form a single-cell suspension. Abs were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA), eBioscience (San Diego CA) or Biolegend (San Diego CA). 1–2×106 cells were stained with CD11b-APC (clone M1/70), Gr-1-FITC or Alexa Fluor 700 (AF700) (clone RB6-8C5), CD45-AF700 (clone 30-F11), Ly-6G-PE (clone 1A8), Ly-6C-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone AL-21), CD115-AF488 (clone AFS98), CD11c-PerCP-Cy5.5 (clone HL3) and F4/80-PE-Cy7 (clone BM8). Isotype control Abs and unstained samples were included in the analyses. Data were acquired on an LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc).

RNA extraction and real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR

Frozen tongue was homogenized in RLT lysis buffer (RNAeasy Kit, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with a GentleMACS Dissociator (M-tubes, RNA02 program, Miltenyi). RNA was extracted with RNAeasy Kit. In all, 0.732 μg total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with a SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Relative quantification of indicated genes was determined by real-time PCR with SYBR Green (Quanta BioSciences, Gaithersburg, MD) normalized to GAPDH. Primers were from SA Biosciences (Qiagen). Results were analyzed on a 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) in triplicate.

Statistics

Data were compared by Mann-Whitney or unpaired Student’s t test using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA) or Microsoft Excel. P values < 0.05 were considered significant. All experiments were performed a minimum of twice.

Results

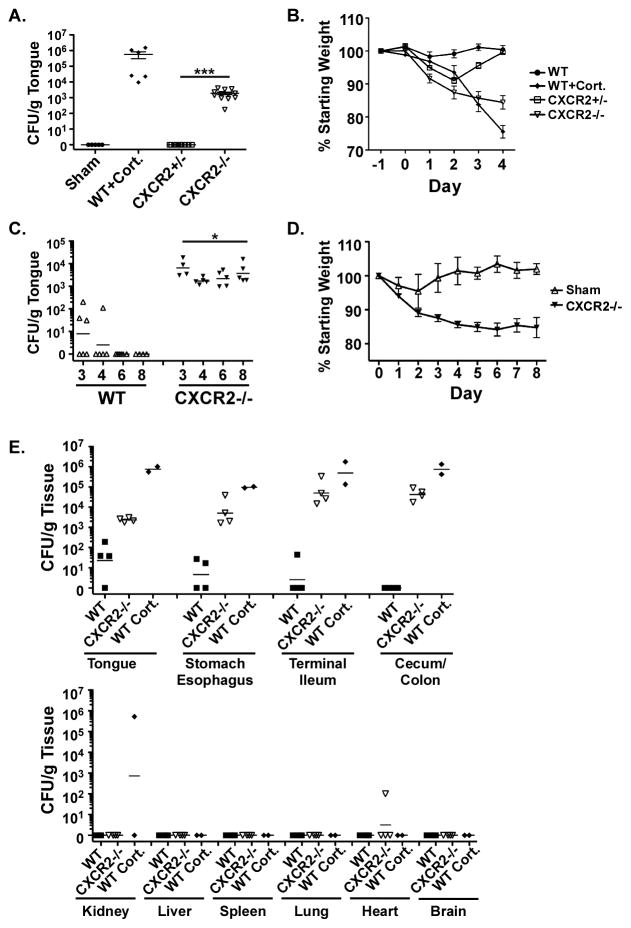

CXCR2 deficiency induces persistent susceptibility to OPC

To assess the contribution of neutrophils to host defense from OPC, we used a mouse deficient in neutrophil recruitment due to knockout of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 (22, 29). CXCR2−/− mice exhibit abnormal neutrophil trafficking in response to the chemokines CXCL1, CXCL2 and CXCL5, all of which are upregulated by IL-17 during oral C. albicans infection (22, 29–31). We subjected CXCR2−/− mice to OPC by sustained sublingual exposure (4, 28). In this model, WT mice are resistant to infection but cortisone-treated or IL-17RA-deficient mice are susceptible (4, 28). Whereas heterozygous littermates were not susceptible to OPC, CXCR2−/− mice showed a mean oral fungal burden of 1.9×103 CFU/gram tongue tissue at 4 days after inoculation (Figure 1A). CXCR2−/− mice also showed progressive weight loss after inoculation, with a mean of 16% weight loss on day 4 compared to baseline (Figure 1B). To determine whether CXCR2−/− mice showed persistent susceptibility or only a delayed clearance, CXCR2−/− mice and WT littermates were inoculated with C. albicans on day 0 and oral fungal burden was assessed on days 3, 4, 6 and 8. CXCR2−/− mice had persistent oral fungal burden through day 8, in contrast to WT littermates that cleared the fungus fully by day 5 (Figure 1C). Consistently, weight loss in CXCR2−/− mice was sustained through day 8, whereas WT mice returned to baseline (Figure 1D). Although C. albicans was found in the mouth and GI tract after infection, CXCR2−/− mice did not show dissemination of yeast to peripheral organs such as kidney or brain, measured on day 4 after inoculation (Figure 1E). Thus, CXCR2 signaling is essential for immunity to oral candidiasis, but not for barrier maintenance and prevention of dissemination.

Figure 1. CXCR2 deficiency induces persistent susceptibility to OPC.

(A) CXCR2−/− mice are susceptible to OPC. CXCR2+/− and CXCR2−/− mice at 7–16 weeks of age were subjected to OPC on Day 0. Sham-infected mice and WT mice treated with cortisone acetate were used as controls. Mice were sacrificed at 4 days and fungal burden in tongue was assessed by plating and colony enumeration. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments and geometric means are shown. *** p<0.001 versus CXCR2+/−. (B) CXCR2−/− mice show steady weight loss after inoculation. Mice were inoculated as in panel (A) and daily weight shown as a percentage of day −1. Means and SEM are shown. * p<0.05 comparing samples at matched time points. (C) CXCR2−/− mice show persistent C. albicans infection. CXCR2−/− and WT littermates at 6–9 weeks of age were subjected to OPC on Day 0, and tongues were assessed for fungal burden on days 3–8. Geometric means are shown. (D) CXCR2−/− mice show persistent weight loss. Mice were inoculated as in panel (C), and daily weight compared to day −1. Means and SEM are shown. (E) There is no dissemination of C. albicans from GI tract to peripheral organs in CXCR2−/− mice. 4 days after oral inoculation, CXCR2−/− or WT mice ± cortisone acetate were evaluated for fungal loads in the indicated organs.

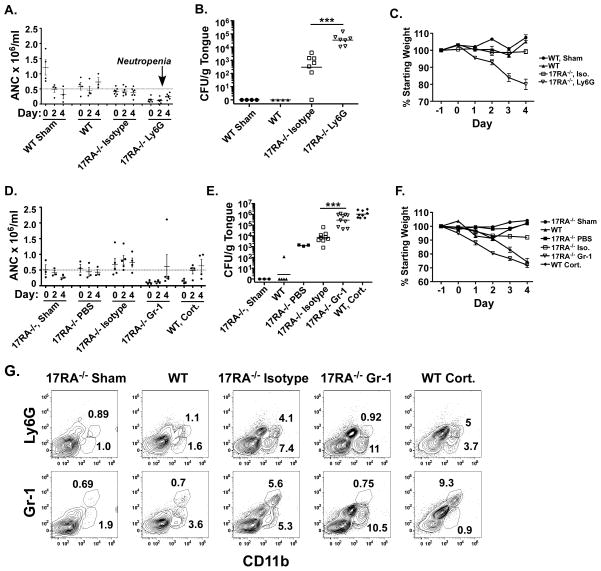

Neutrophil depletion augments OPC in IL-17/Th17-deficient mice

To investigate the degree to which IL-17 signaling is responsible for regulation of neutrophils in OPC, antibodies to deplete neutrophils were administered during the course of infection in IL-17RA−/− mice. IL-17RA−/− mice were treated with anti-Ly-6G (clone 1A8), which recognizes a highly expressed marker on neutrophils, 24 hours prior to and 2 days post infection. Anti-Ly-6G-treated mice were neutropenic throughout the experimental period, with absolute neutrophil counts (ANC) less than 0.5 × 106 neutrophils/ml (Figure 2A). As expected, IL-17RA−/− mice treated with isotype Abs were susceptible to OPC, similar to untreated IL-17RA−/− (4) (Figure 2B). IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Ly-6G showed significantly higher oral fungal burdens than isotype-treated mice (Figure 2B). The anti-Ly-6G-treated mice also displayed more weight loss than isotype-treated mice (Figure 2C).

Figure 2. Elevated oral fungal load with preserved CD11b+ tongue cellular infiltrate in IL-17RA−/− mice following neutrophil depletion.

(A) IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Ly-6G had sustained neutropenia. IL-17RA−/− mice were treated with isotype or anti-Ly-6G Abs on days −1 and 2 and subjected to OPC on Day 0. Sham- and Candida-inoculated WT mice served as controls. Peripheral blood neutrophil counts were assessed by visual smear examination on days 0, 2 and 4. Geometric means are shown. Dashed line indicates threshold for clinically significant neutropenia. (B) IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Ly-6G have elevated oral fungal burdens. Mice were treated with Abs and infected as in (A). Fungal burden in tongue was assessed 4 days after inoculation. Geometric means are shown. *** p<0.001. (C) IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Ly-6G display elevated weight loss. Mice were treated with Ab and inoculated as in (A). Mice were weighed daily and weight loss compared to baseline. Means and SEM are shown. (D) IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Gr-1 exhibit profound neutropenia. IL-17RA−/− mice were treated with isotype or anti-Gr-1 Abs on days −1 and 2 and subjected to OPC on Day 0. Controls included: sham- or Candida-inoculated IL-17RA−/− mice, IL-17RA−/− mice treated with PBS, Candida-inoculated WT mice, and cortisone-treated WT mice. Peripheral blood neutrophil counts were assessed as in (A). Geometric means are shown. Dashed line indicates threshold for clinically significant neutropenia (E) IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Gr-1 Abs show an elevated oral fungal burden. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (D). Fungal burden in tongue tissue was assessed after 4 days. *** p<0.001. Mice were evaluated in 2 independent experiments. (F) IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Gr-1 exhibited profound weight loss. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (D). Mice were weighed daily and weight loss compared to baseline. (G) Candida-inoculated IL-17RA−/− mice show a CD11b+ cellular infiltrate in tongue that is maintained with anti-Gr-1 treatment. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (D). Tongue was harvested on day 4 and fluorochrome-stained tongue homogenates were analyzed by flow cytometry.

To extend these findings, IL-17RA−/− mice were treated with an antibody directed against Gr-1 (clone RB6-8C5), which recognizes Ly-6G, and to a lesser extent Ly-6C, on mature granulocytes, monocytes (transiently during differentiation) and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (at low levels). Most mice treated with anti-Gr-1 demonstrated peripheral blood neutropenia (Figure 2D). IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Gr-1 exhibited a significant increase in oral fungal burden compared to isotype-treated mice 4 days after inoculation (Figure 2E). Dissemination of C. albicans to the kidney was found in 10% of IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Gr-1, but not in mice treated with isotype Abs, PBS or anti-Ly-6G (data not shown). Treatment with isotype did not alter the susceptibility of IL-17RA−/− mice to OPC compared to PBS. Treatment with anti-Gr-1 resulted in increased weight loss in IL-17RA−/− after OPC challenge, similar to the weight loss observed in WT mice treated with high-dose cortisone (Figure 2F). Collectively, these data show that the susceptibility to OPC due to defective IL-17 signaling can be augmented by neutrophil depletion.

Although anti-Gr-1 and anti-Ly-6G can cause profound depletion of peripheral blood neutrophils, this has been shown to correlate poorly with neutrophil depletion in resident tissues (24). Accordingly, we assessed the effects of Ab treatment on neutrophil infiltration into tongue by flow cytometry. At 4 days after inoculation, WT mice showed a small but measurable CD11b+Gr-1low population (Figure 2G). Inoculated WT mice treated with cortisone showed a tongue infiltrate of CD11b+Gr-1hi cells. Sham-treated IL-17RA−/− mice showed minimal infiltrate of cells staining positive for CD11b, Ly-6G or Gr-1. IL-17RA−/− mice treated with isotype showed a robust infiltrate of CD11b+Ly-6Ghi and CD11b+Ly-6Glow cells. In inoculated IL-17RA−/− mice treated with anti-Gr-1, only the tongue infiltrate of CD11b+Ly-6Glow cells was observed, and these cells were Gr-1low (Figure 2G). These data indicate that OPC induces a local CD11b+ cellular infiltrate that is preserved after treatment with anti-Gr-1 Abs, but the absence of CD11b+Ly-6Ghi neutrophils results in heightened susceptibility to OPC.

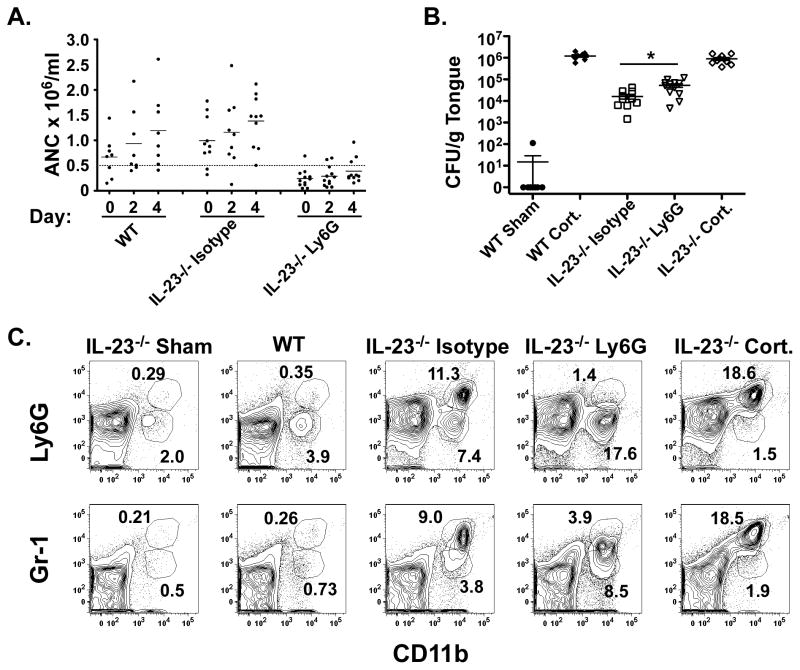

IL-23 is critical for the maintenance of IL-17-producing cells (32, 33), and deficiency in IL-23 results in susceptibility to OPC at levels indistinguishable from IL-17RA−/− mice (9). To determine whether neutrophil depletion in IL-23−/− mice followed a similar profile, IL-23−/− mice were treated with anti-Ly-6G 24 hours prior to and 2 days after oral inoculation with C. albicans. Mice were neutropenic throughout the experimental period with peripheral ANC less than 0.5 × 106 neutrophils/ml (Figure 3A). Mice treated with anti-Ly-6G showed a significant increase in fungal burden on day 4 compared to IL-23−/− mice treated with isotype Abs (Figure 3B). Similar to the IL-17RA−/− mice, IL-23−/− mice treated with isotype Abs exhibited a robust infiltrate of CD11b+Gr-1hi cells in tongue. IL-23−/− mice treated with anti-Ly-6G continued to have a CD11b+ population, but Gr-1 staining shifted to Gr-1low (Figure 3C). Low numbers of CD11b+Ly-6Glow cells were present in sham-infected IL-23−/− and Candida-infected WT mice, while IL-23−/− mice treated with cortisone and inoculated with C. albicans showed a robust infiltrate of CD11b+Ly-6Ghi and Gr-1hi cells (Figure 3C). Together, these results show that deficiency in Th17 cells or IL-17 signaling does not fully eliminate the neutrophilic response to OPC.

Figure 3. Neutrophil depletion in IL-23−/− mice increases susceptibility to OPC.

(A) IL-23−/− mice treated with anti-Ly-6G show peripheral neutropenia. IL-23−/− mice were treated with isotype or anti-Ly-6G Abs on days −1 and 2 and subjected to OPC on day 0. Control mice include: Candida-inoculated WT, cortisone-treated WT and cortisone-treated IL-23−/− mice. Peripheral blood neutrophil counts were assessed as in Figure 2A. Dashed line indicates threshold for clinically significant neutropenia. (B) IL-23−/− mice treated with anti-Ly-6G show elevated oral fungal burdens. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (A) and fungal burden in tongue tissue assessed after 4 days. Mice were evaluated in 2 independent experiments, and geometric means are shown. * p<0.05 (C) IL-23−/− mice exhibit a robust CD11b+ cell population in tongue, which is Gr-1low in anti-Ly-6G-treated mice. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (A). Tongue was harvested on day 4.

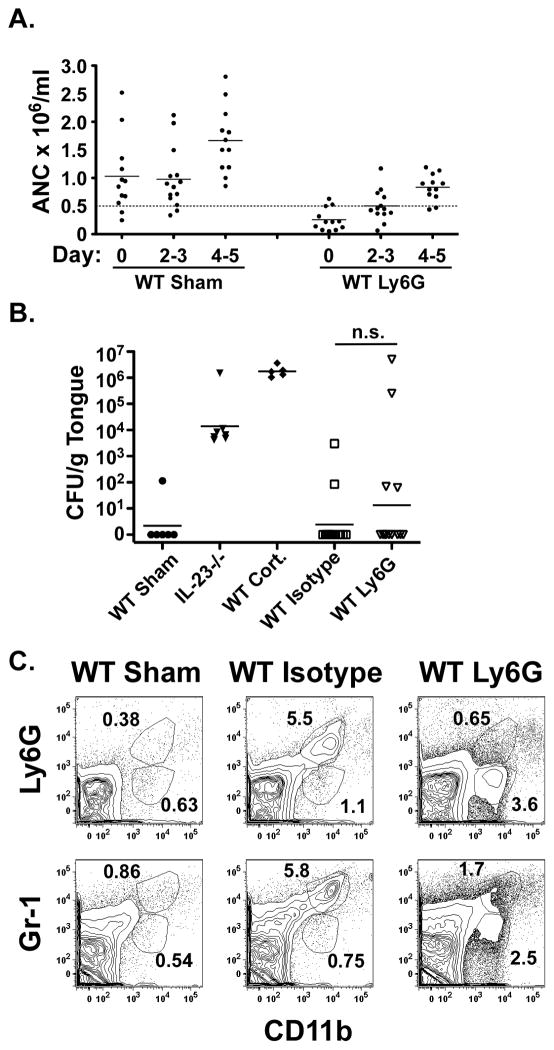

Susceptibility to OPC is induced in normally resistant WT mice with myeloid cell depletion

Next, we assessed whether neutrophil depletion induced susceptibility in WT mice. WT mice were treated with isotype or anti-Ly-6G as described above. Peripheral ANC demonstrated a transient neutropenia in anti-Ly-6G-treated mice, with recovery above 0.5 × 106 cells/ml by day 4–5 (Figure 4A). Neutrophil-depleted mice showed a bimodal response to inoculation, with 86% of mice completely resistant to infection while 14% were profoundly susceptible with high oral fungal burdens, sustained weight loss and dissemination to kidney at day 4–5 (Figure 4B and data not shown). The cohort treated with anti-Ly-6G experienced weight loss similar to isotype-treated mice (data not shown). There was no correlation between the degree of neutropenia and susceptibility to OPC. Isotype-treated mice had a large infiltrate of CD11b+Gr-1hi cells, while anti-Ly-6G-treated mice showed an infiltrate of CD11b+Gr-1low cells at day 2. Both populations were absent in sham-inoculated WT mice (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Selective neutrophil depletion induces susceptibility to OPC in a subset of WT mice.

(A) WT mice treated with anti-Ly-6G exhibit transient peripheral neutropenia. WT mice were treated with isotype control or anti-Ly-6G on days −1 and 2 and subjected to OPC on day 0. Controls were WT sham-inoculated mice, IL-23−/− and cortisone-treated WT mice. Peripheral neutrophil counts were assessed as described in Figure 2A. Dashed line indicates threshold for clinically significant neutropenia. (B) WT mice treated with anti-Ly-6G show a bimodal response. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (A). Fungal burden in tongue was assessed after 4–5 d. Mice were evaluated in 2 independent experiments and geometric means are shown. n.s., not significant. (C) WT mice show a CD11b+ tongue infiltrate on day 2 after inoculation. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (A). Tongue was harvested on day 2 and analyzed by flow cytometry.

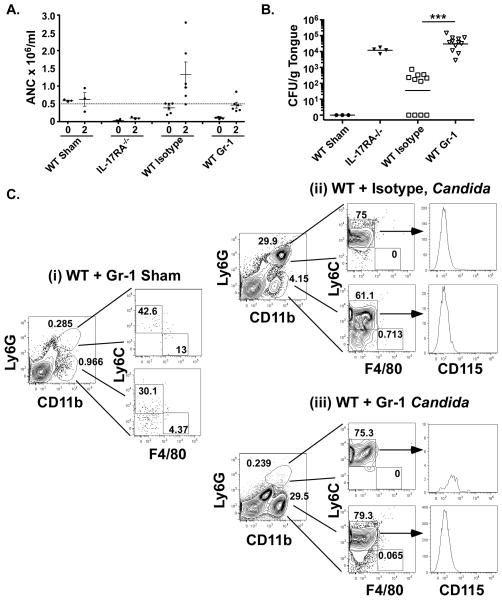

Although anti-Ly-6G and anti-Gr-1 treatments cause similar phenotypes in IL-17RA−/− mice, their effects were different in WT mice. Anti-Gr-1 resulted in profound peripheral neutropenia on day zero, with some count recovery by day 2 (Figure 5A). Unlike the anti-Ly-6G-treated mice, these animals were profoundly ill, with decreased activity and grooming seen as early as day 1. Mice were sacrificed on day 3 for humane reasons, at which time there was a significant difference in the oral fungal burden between isotype and anti-Gr-1-treated mice (Figure 5B). At 2 days after inoculation, sham-treated WT mice treated with Gr-1 Abs showed minimal infiltration of leukocytes staining positive for CD11b and Ly-6G (Figure 5C panel i). WT mice treated with isotype Abs and inoculated with Candida had a dominant population of CD11b+Ly-6Ghi cells and a smaller population of CD11b+Ly-6Glow cells. At day 3, both populations were starting to wane as the infection cleared (data not shown). In WT mice treated with anti-Gr-1 and infected with Candida, a much larger percentage of the population consisted of CD11b+Ly-6Glow cells (Figure 5C, panel ii). The CD11b+ population was further characterized by staining for macrophage/monocyte markers including Ly-6C, F4/80 and CD115. Based on these markers, the cell infiltrate in infected mice (isotype treated) was consistent with neutrophils (CD11b+Ly-6GhiLy-6Chi) and inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+Ly-6GlowLy-6Chi) (Figure 5C, panel ii). The neutrophil population but not the inflammatory monocyte population was depleted in anti-Gr-1-treated mice (Figure 5C, panel iii). The inflammatory monocytes that remained could not orchestrate Candida clearance, since these mice were highly susceptible to OPC (Figure 5B). Markers for monocyte-derived phagocytes were absent from this population, as these cells did not stain strongly for F4/80 or CD115 (Figure 5C). We also looked for DCs by staining for CD11c, but no positive cells were observed (data not shown).

Figure 5. Neutrophil depletion with anti-Gr-1 induces susceptibility to OPC in WT mice.

(A) WT mice treated with anti-Gr-1 Abs have peripheral neutropenia. Mice were treated with isotype or anti-Gr-1 Abs on days −1 and 2 and subjected to OPC on day 0. Controls include WT sham-inoculated and IL-17RA−/− mice. Peripheral neutrophil counts were determined as in Figure 2A. Dashed line indicates threshold for clinically significant neutropenia. (B) WT mice treated with anti-Gr-1 are highly susceptible to OPC. Mice were treated with Abs and inoculated as in (A). Fungal burden was assessed after 3 d. Mice were evaluated in 2 independent experiments and geometric means are shown. ***p<0.001. (C) Anti-Gr-1-treated WT mice lose neutrophils but not inflammatory monocytes in tongue. WT mice were treated with anti-Gr-1 Abs (panels i and iii) or istopye (panel ii) and inoculated with C. albicans (panels ii and iii) as in (A). Tongue was harvested on day 2 and analyzed by flow cytometry.

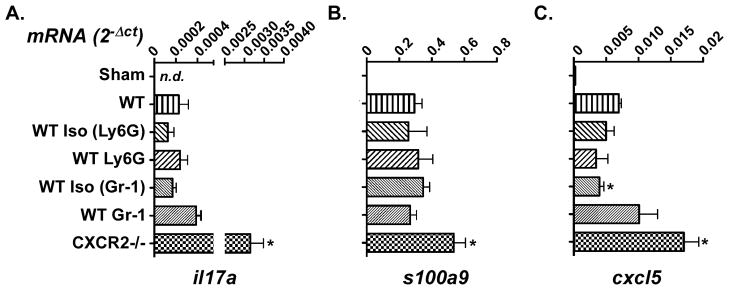

A Gr-1+ or CD11b+ cell capable of suppressing T cells has been described in other settings, including disseminated candidiasis (34–36). To determine whether the cellular influx into the tongue after oral Candida challenge suppressed the IL-17/Th17-mediated host defense, we examined expression of a panel of IL-17 signature genes known to be induced in tongue after C. albicans exposure (4). There was no significant difference in expression of il17a between mice treated with isotype or neutrophil-depleting antibodies compared to untreated WT mice (Figure 6A). There was also no difference in expression of the neutrophil-associated gene s100a9 (Figure 6B). There was a small but significant decrease in expression of the CXCR2 ligand cxcl5 in mice treated with the isotype for anti-Gr-1, but no other differences in treated compared to untreated WT mice were observed (Figure 6C). As expected, there was no basal expression of il17a or IL-17 signature genes in sham-inoculated mice, but there was an elevation in il17a expression in CXCR2−/− mice (4, 22). These findings indicate that the tongue cellular influx does not appear to suppress IL-17 expression or activity.

Figure 6. No evidence for suppression of IL-17 responses upon anti-Ly-6G or anti-Gr-1 treatment.

WT mice were treated with isotype control Abs (n=3–5 mice), anti-Ly-6G (n=3), anti-Gr-1 (n=5) or no Ab (n=3) on Day −1, and subjected to OPC on Day 0. Controls include: sham-inoculated WT mice (n=3) or CXCR2−/− mice (n=2). Tongue mRNA was evaluated for il17a (A), s100a9 (B) or cxcl5 (C) by real-time RT-PCR. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate and bars represent means with SEM. *p<0.05 compared to WT. n.d., not detectable.

Discussion

In this study we demonstrate that Gr-1+ neutrophils are vital for the elimination of C. albicans from the oral mucosa. Deficiency in the CXCR2 chemokine receptor results in persistent oral fungal burdens, weight loss and augmented IL-17 signature gene expression in the oral tissue, although no dissemination to visceral organs was detectable. Antibody-mediated neutrophil depletion also results in susceptibility to OPC in normally resistant WT mice. Susceptibility is profound and consistent in mice broadly depleted of myeloid cells with anti-Gr-1 Mab, and susceptibility is also induced with the more specific anti-Ly-6G Mab. Additionally, an increase in susceptibility is induced in mice deficient in Th17 cells or IL-17 signaling upon antibody-mediated neutrophil depletion, indicating that IL-17 does not account for all of the Ly-6G/Gr-1 dependent host protection in the oral cavity. All susceptible mice showed a CD11b+ tongue infiltrate, with alterations in Ly-6G and Gr-1 positivity depending on the specific antibody treatment. It has been long assumed that neutrophils and CXC chemokines are the mediators of host defense at the oral mucosal surface, but the evidence supporting this assumption is surprisingly scant. This is, to our knowledge, the first study to directly demonstrate a role for CXCR2 in OPC and the role of neutrophils in the context of IL-23/IL-17 signaling deficiency.

CXCR2, as the central chemokine receptor for neutrophil recruitment, is considered a potential therapeutic target (37), and thus our data suggest a potential new infectious risk implication of blocking CXCR2. In the context of fungal infections, CXCR2 is linked to fungal asthma and resistance to invasive pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus (26, 38, 39). In the oral cavity, CXCR2 plays a host-protective role in a mouse model of periodontal disease, with CXCR2 deficiency resulting in a more severe phenotype of oral bone loss than IL-17 signaling deficiency alone (31). Depletion of neutrophils, the primary CXCR2-expressing cell type, with anti-Ly6G Abs resulted in two distinct phenotypes. The majority of mice were resistant to OPC, but a subset was profoundly ill with both oral and disseminated candidiasis (Figure 4B). The more severe phenotype was observed in all anti-Gr-1 treated mice (Figure 5B). It remains controversial in the field whether Ly-6G Abs are simply less efficient at depleting neutrophils than Gr-1 Abs, or whether an alternative Ly-6G-negative cell type exists that compensates for neutrophils upon depletion. Our data are more consistent with the former model, as our staining experiments did not reveal any evidence for an alternative monocytic cell that might be functionally compensatory. In disseminated candidiasis, however, there is evidence that inflammatory monocytes can mediate Candida clearance from kidney (40), but immunity to mucosal candidiasis is known to be considerably different from disseminated disease. A caveat to mouse models of candidiasis is the potential difference in the human and mouse neutrophil response to C. albicans. A recent report found a reduced ability to kill C. albicans and increased phagocyte death after in murine versus human neutrophils (41). Therefore, it remains to be determined whether the compensatory CD11b+ cell response we see in mice occurs in humans, where the direct neutrophil response to C. albicans is more effective.

It was unexpected to find that susceptibility to OPC in mice lacking IL-23 or IL-17 signaling could be augmented by neutrophil depletion. Although signals for neutrophil recruitment are mediated by IL-17 in the context of OPC, alternative mechanisms of neutrophil regulation and recruitment thus appear to be present when IL-17 signaling is perturbed. Cellular influx of CD11b+ cells into the tongue was observed in mice experiencing active infection (Figures 2G, 3C), which may be due to toll-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors or other cytokines. In addition to mediating expression of neutrophil-recruiting chemokines, IL-17 regulates expression of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that exhibit anti-fungal activity, such as β-defensins and histatins (4, 42). IL-17 also mediates host defense through alterations in cytokine production and synergy with other pro-inflammatory effectors (43). The entirety of IL-17-mediated host protection to candidiasis presumably comes from the combined effects on all these facets of the immune system.

As noted, there are limited tools to study isolated states of neutropenia in mice. Historically, many studies used cyclophosphamide, whole body irradiation or other chemotherapeutic agents that induce neutropenia, but these regimens also cause defects in other leukocytes and mucosal integrity. Selective depletion of neutrophils with monoclonal antibodies is a useful approach, but has limitations. Commercially available Abs such as anti-Gr-1 and anti-Ly-6G deplete mature neutrophils, but may also affect eosinophils, monocytes and dendritic cells. In addition, these Abs deplete mature neutrophils but not the immature band forms, which are nonetheless fully functional. Therefore, in response to intact signals for neutrophil production in the bone marrow and/or neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection, an ongoing robust neutrophilic response may occur even in the face of continued antibody treatment. This is most evident in the affected tissue, and is overlooked if only peripheral blood is evaluated to assess efficiency of depletion. In a prior study attempting to address the issue of neutrophils in OPC, a swabbing method was used to as a qualitative measure of fungal infection (44). However, that approach does not accurately recover hyphal forms of the yeast that have invaded the mucosal tissue. The current study advances the field by providing a highly quantitative evaluation of susceptibility to invasive mucosal Candida infection, the hallmark of OPC, in states of neutrophil/myeloid cell impairment.

The prevalence of immunodeficiency is on the rise, along with an increasing awareness of the risk of opportunistic infection in susceptible patients. In clinical medicine, morbidity and mortality due to fungal infections are observed in patients with neutropenia. Early reports of primary immunodeficiency with isolated neutropenia focused on invasive rather than mucosal candidiasis, but more recent case reports of congenital neutropenia highlight susceptibility to oral candidiasis (45). Neutropenia can also be secondary to immunosuppressive medications, medication side effects or autoimmunity. Notably, neutropenia is rarely an isolated immunodeficiency. Combination defects in branches of the immune system are common and are likely to become more so with the increasing use of selective immunomodulation with biologic agents. The current study is directly relevant to the use of drugs currently in development that target IL-17 and the Th17 pathway (46–48). Along these lines, a recent analysis of IBD patients showed that anti-TNFα therapy is linked to oral candidiasis (49). Our findings suggest that the addition of IL-17 blockade to neutropenia-inducing therapies is likely to lead to a substantially increased risk of mucosal candidiasis.

Acknowledgments

IL-23−/− mice were provided by Genentech, and IL-17RA−/− mice by Amgen. We thank M Simpson-Abelson, M McGeachy, M Michaels, MH Nguyen, PL Lin and B Mehrad for helpful suggestions and AJ Mamo for technical assistance.

SLG was supported by the NIH (DE022550). TD was supported by AI054624. HRC was supported by F32-DE023293 and ARH by the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of the UPMC Health System and a Pediatric Infectious Disease Society Fellowship Award (funded by the Stanley A. Plotkin Sanofi Pasteur Fellowship Award). PB was supported by the Division of Rheumatology at UPMC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Antachopoulos C, Walsh TJ, Roilides E. Fungal infections in primary immunodeficiencies. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1099–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farah CS, Lynch N, McCullough MJ. Oral fungal infections: an update for the general practitioner. Aust Dent J. 2010;55(Suppl 1):48–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2010.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huppler AR, Bishu S, Gaffen SL. Mucocutaneous candidiasis: the IL-17 pathway and implications for targeted immunotherapy. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14:217. doi: 10.1186/ar3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milner JD, Brenchley JM, Laurence A, et al. Impaired T(H)17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452:773–776. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaffen SL, Hernandez-Santos N, Peterson AC. IL-17 signaling in host defense against Candida albicans. Immunol Res. 2011;50:181–187. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8226-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Veerdonk FL, Gresnigt MS, Kullberg BJ, et al. Th17 responses and host defense against microorganisms: an overview. BMB Rep. 2009;42:776–787. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2009.42.12.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho AW, Shen F, Conti HR, et al. IL-17RC is required for immune signaling via an extended SEF/IL-17R signaling domain in the cytoplasmic tail. J Immunol. 2010;185:1063–1070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saunus JM, Wagner SA, Matias MA, et al. Early activation of the interleukin-23-17 axis in a murine model of oropharyngeal candidiasis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2010;25:343–356. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2010.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puel A, Cypowyj S, Bustamante J, et al. Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in humans with inborn errors of interleukin-17 immunity. Science. 2011;332:65–68. doi: 10.1126/science.1200439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boisson B, Wang C, Pedergnana V, et al. A biallelic ACT1 mutation selectively abolishes interleukin-17 responses in humans with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. Immunity. 2013;39:676–686. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koh AY, Kohler JR, Coggshall KT, et al. Mucosal damage and neutropenia are required for Candida albicans dissemination. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e35. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Concia E, Azzini AM, Conti M. Epidemiology, incidence and risk factors for invasive candidiasis in high-risk patients. Drugs. 2009;69(Suppl 1):5–14. doi: 10.2165/11315500-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Del Favero A. Management of fungal infections in neutropenic patients: more doubts than certainties? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;16:135–137. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welte K, Zeidler C, Dale DC. Severe congenital neutropenia. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:189–195. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lanza F. Clinical manifestation of myeloperoxidase deficiency. J Mol Med (Berl) 1998;76:676–681. doi: 10.1007/s001090050267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rot A, von Andrian UH. Chemokines in innate and adaptive host defense: basic chemokinese grammar for immune cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:891–928. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cacalano G, Lee J, Kikly K, et al. Neutrophil and B cell expansion in mice that lack the murine IL-8 receptor homolog. Science. 1994;265:682–684. doi: 10.1126/science.8036519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reutershan J, Morris MA, Burcin TL, et al. Critical role of endothelial CXCR2 in LPS-induced neutrophil migration into the lung. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:695–702. doi: 10.1172/JCI27009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson TS, Ley K. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in leukocyte trafficking. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2002;283:R7–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00738.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mei J, Liu Y, Dai N, et al. Cxcr2 and Cxcl5 regulate the IL-17/G-CSF axis and neutrophil homeostasis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:974–986. doi: 10.1172/JCI60588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murdoch C, Monk PN, Finn A. Cxc chemokine receptor expression on human endothelial cells. Cytokine. 1999;11:704–712. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frazer LC, O’Connell CM, Andrews CW, Jr, et al. Enhanced neutrophil longevity and recruitment contribute to the severity of oviduct pathology during Chlamydia muridarum infection. Infect Immun. 2011;79:4029–4041. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05535-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wozniak KL, Kolls JK, Wormley FL., Jr Depletion of neutrophils in a protective model of pulmonary cryptococcosis results in increased IL-17A production by gammadelta T cells. BMC Immunol. 2012;13:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-13-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehrad B, Strieter RM, Moore TA, et al. CXC chemokine receptor-2 ligands are necessary components of neutrophil-mediated host defense in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. J Immunol. 1999;163:6086–6094. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daley JM, Thomay AA, Connolly MD, et al. Use of Ly6G-specific monoclonal antibody to deplete neutrophils in mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:64–70. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamai Y, Kubota M, Kamai Y, et al. New model of oropharyngeal candidiasis in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45:3195–3197. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.3195-3197.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eash KJ, Greenbaum AM, Gopalan PK, et al. CXCR2 and CXCR4 antagonistically regulate neutrophil trafficking from murine bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2423–2431. doi: 10.1172/JCI41649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen F, Gaffen SL. Structure-function relationships in the IL-17 receptor: implications for signal transduction and therapy. Cytokine. 2008;41:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu JJ, Ruddy MJ, Wong GC, et al. An essential role for IL-17 in preventing pathogen-initiated bone destruction: recruitment of neutrophils to inflamed bone requires IL-17 receptor-dependent signals. Blood. 2007;109:3794–3802. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-010116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton CE, Lalor SJ, Sweeney CM, et al. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghilardi N, Ouyang W. Targeting the development and effector functions of TH17 cells. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serafini P, Carbley R, Noonan KA, et al. High-dose granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor-producing vaccines impair the immune response through the recruitment of myeloid suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6337–6343. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bronte V, Apolloni E, Cabrelle A, et al. Identification of a CD11b(+)/Gr-1(+)/CD31(+) myeloid progenitor capable of activating or suppressing CD8(+) T cells. Blood. 2000;96:3838–3846. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mencacci A, Montagnoli C, Bacci A, et al. CD80+Gr-1+ myeloid cells inhibit development of antifungal Th1 immunity in mice with candidiasis. J Immunol. 2002;169:3180–3190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stadtmann A, Zarbock A. CXCR2: From Bench to Bedside. Front Immunol. 2012;3:263. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bonnett CR, Cornish EJ, Harmsen AG, et al. Early neutrophil recruitment and aggregation in the murine lung inhibit germination of Aspergillus fumigatus Conidia. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6528–6539. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00909-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schuh JM, Blease K, Hogaboam CM. CXCR2 is necessary for the development and persistence of chronic fungal asthma in mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:1447–1456. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ngo L, Kasahra S, Kumasaka D, et al. Inflammatory monocytes mediate early and organ-specific innate defense during systemic candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit413. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ermert D, Niemiec MJ, Rohm M, et al. Candida albicans escapes from mouse neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1189/jlb.0213063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conti HR, Baker O, Freeman AF, et al. New mechanism of oral immunity to mucosal candidiasis in hyper-IgE syndrome. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;4:448–455. doi: 10.1038/mi.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aujla SJ, Dubin PJ, Kolls JK. Th17 cells and mucosal host defense. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Farah CS, Elahi S, Pang G, et al. T cells augment monocyte and neutrophil function in host resistance against oropharyngeal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6110–6118. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6110-6118.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mamishi S, Esfahani SA, Parvaneh N, et al. Severe congenital neutropenia in 2 siblings of consanguineous parents. The role of HAX1 deficiency. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19:500–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leonardi C, Matheson R, Zachariae C, et al. Anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody ixekizumab in chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1190–1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, et al. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1181–1189. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel DD, Lee DM, Kolbinger F, et al. Effect of IL-17A blockade with secukinumab in autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(Suppl 2):ii116–123. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ford AC, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Opportunistic Infections With Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1268–1276. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]