Abstract

Catechol-O-methyltransferase, encoded by COMT gene, is the primary enzyme that metabolizes catecholamines. COMT haplotypes have been associated with vulnerability to persistent non-traumatic pain. In this prospective observational study, we investigated the influence of COMT on persistent pain and pain interference with life functions after motor vehicle collision (MVC) in 859 European American adults for whom overall pain (0–10 numeric rating scale) and pain interference (Brief Pain Inventory) were assessed at week 6 after MVC. Ten single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) spanning the COMT gene were successfully genotyped, nine were present in three haploblocks: block 1 (rs2020917, rs737865, rs1544325), block 2 (rs4633, rs4818, rs4680, rs165774) and block 3 (rs174697, rs165599). After adjustment for multiple comparisons, haplotype TCG from block 1 predicted decreased pain interference (p =.004). The pain-protective effect of the low pain sensitivity (LPS, CGGG) haplotype from block 2 was only observed if at least one TCG haplotype was present in block 1 (haplotype × haplotype interaction p=.002 and <.0001 for pain and pain interference, respectively). Haplotype AG from block 3 was associated with pain and interference in males only (sex × haplotype interaction p=.005 and .0005, respectively). These results suggest that genetic variants in the distal promoter are important contributors to the development of persistent pain after MVC, directly and via the interaction with haplotypes in the coding region of the gene.

Keywords: Catechol-O-methyltransferase, musculoskeletal pain, motor vehicle collision, stress

INTRODUCTION

COMT has been shown to influence an array of complex phenotypes, including pain phenotypes (Nackley et al. 2006b; Diatchenko et al. 2005; Meyer-Lindenberg et al. 2006; Zubieta et al. 2003; Smolka et al. 2007; Reuter and Hennig 2005). Initially it was widely assumed that variations in COMT activity in humans were caused only by the non-synonymous valine (Val) to methionine (Met) substitution at codon 158 (rs4680), which results in reduced thermostability and reduced activity of the enzyme (Lotta et al. 1995). Numerous studies identified associations between the low-activity Met158 allele and several pain phenotypes (e.g. (Smith et al. 2011; Cohen et al. 2009; Barbosa et al. 2012; Jacobsen et al. 2012; van Meurs et al. 2009; Gursoy et al. 2003)), however the observed associations were often modest and occasionally inconsistent (Tander et al. 2008; Hocking et al. 2010; Nicholl et al. 2010), suggesting that additional SNPs in the COMT gene modulate COMT activity.

In a study examining the association between COMT genotypes in the central haploblock of the COMT gene and variability in human pain perception, the Val158Met polymorphism alone was not significantly associated with pain sensitivity (Diatchenko et al. 2005). Instead, three common haplotypes in the central haploblock, including two synonymous SNPs (rs4633 and 4818) and the nonsynonymous Val158Met SNP, were found to code for different levels of enzymatic activity and influence vulnerability to persistent musculoskeletal pain (Diatchenko et al. 2005). These differences in COMT enzyme activity were subsequently demonstrated to be mediated by haplotype-dependent differences in secondary RNA structure (Nackley et al. 2006a). The robust effect of these haplotype-dependent differences in secondary RNA structure on COMT enzyme activity was found to be much greater than the modest effect of the Val158Met substitution alone (Nackley et al. 2006a).

Despite these data, studies examining the association between COMT haplotypes in the central haploblock of the COMT gene and persistent musculoskeletal pain outcomes have produced inconsistent results. While COMT haplotypes predicted fibromyalgia symptom severity in Spanish (but not Mexican) women (Vargas-Alarcon et al. 2007), two other population-based studies failed to demonstrate an association of COMT haplotypes and chronic widespread pain (Hocking et al. 2010; Nicholl et al. 2010). One potential contributor to these inconsistent results may be that important interactions exist between these haplotypes and other variants in COMT. This hypothesis is supported by evidence that COMT variants outside the central haploblock, including variants in the distal promoter (P2) region and 3′-untranslated region, influence complex phenotypes (Meyer-Lindenberg et al. 2006; Shifman et al. 2002; Gaysina et al. 2013; Shibata et al. 2009). Another potential contributor to inconsistent findings in previous association studies evaluating haplotypes in the central COMT haploblock may be sex-specific effects. Evidence suggests that important differences in the influence of COMT genotypes may exist between men and women (reviewed in (Tunbridge and Harrison 2011)).

In this prospective study we evaluated the influence of haplotypes from three functionally important COMT loci (promoter P2, coding region, and 3′-untranslated region) on vulnerability to persistent pain 6 weeks after motor vehicle collision (MVC). We hypothesized that COMT haplotypes, and/or interactions between haplotypes from these three loci and patient sex, would influence pain severity six weeks after experiencing an MVC. In addition, because pain-related interference with global life function is an important health outcome in patients with pain,(Dworkin et al. 2005) and because COMT may influence not only pain severity but also psychological processes that influence function in the presence of pain (George et al. 2008b; George et al. 2008a), we also evaluated the influence of these haplotypes on pain-related interference six weeks after MVC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The details of the CRASH study have been reported (Platts-Mills et al. 2011). In brief, individuals ≥ 18 and ≤ 65 years of age presenting to one of eight emergency departments in four no-fault insurance states within 24 hours of MVC who did not have fracture or other injury requiring hospital admission were enrolled. Patients who were not alert and oriented were excluded, as were pregnant patients, prisoners, patients unable to read and understand English, patients taking a β-adrenoreceptor antagonist, or patients taking opioids above a total daily dose of 30 mg of oral morphine or equivalent. Participant race was determined via self-report. Enrollment was limited to non-Hispanic whites (the most common ethnicity at study sites) because the study included the collection of genetic data and genetic analyses are potentially biased by population stratification (Diatchenko et al. 2007). Informed consent was obtained from all participants and IRB approval was obtained at all study sites.

DNA collection and genotyping

Blood (8.5cc) was collected using PAXgene DNA storage tubes. Blood samples were then refrigerated at the study site and shipped in batches every 2 weeks to Beckman Coulter Genomics, Inc, Morrisville, NC. DNA purification was performed using PAXgene™ blood DNA kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Average DNA yield was 275 μg per sample. Genotyping was performed at batches using the Sequenom platform (Sequenom, Inc., San Diego, CA). Two Hapmap samples and 2 repeat samples were included in each genotyping batch (96 samples) to ensure genotypic accuracy and reliability. Repeated genotyping demonstrated greater than 98% call agreement.

Outcome assessments

Overall pain intensity six weeks after MVC (defined in this study as “persistent pain”) was assessed via telephone interview or web-based questionnaire using a verbal 0–10 numeric rating scale (NRS) assessing average overall pain intensity during the past week. Verbally administered NRSs have been validated as a substitute for Visual Analog Scales in acute pain measurement in the emergency department (Bijur et al. 2003).

Pain interference with life functions was assessed using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) (Cleeland and Ryan 1994; Keller et al. 2004). Interference with each life function (general activity, walking ability, mood, relations with other people, sleep and enjoyment of life) was assessed on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represents “does not interfere” and 10 indicates “interferes completely”. Interference total score was calculated by adding up interferencesubscale values for each individual.

Analyses

All genotyped SNPs were tested for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) using a chi-square test. SNPs that were not in HWE, SNPs with call rates below 85%, and SNPs with minor allele frequency less than 0.05 were excluded from analyses.

Linkage disequilibrium between COMT SNPs was explored by calculating Levontin D′ and squared correlation r2 using HaploView (Barrett et al. 2005). Haploblocks were estimated using the method of confidence intervals (Gabriel et al. 2002). COMT haplotypes and their population frequencies were estimated using the expectation-maximization algorithm implemented in HaploView and were then verified using Bayesian estimation of haplotype frequencies implemented in HAPLOTYPE procedure (SAS version 9.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) (Lin et al. 2002).

The associations between COMT haplotypes and pain outcomes in the CRASH cohort were assessed using general linear models. Study site was included as a covariate in these models due to potential genetic heterogeneity between study recruitment centers. Interaction between haplotypes and interaction between haplotypes and patient sex were assessed by introducing the corresponding product terms into the models. Partial F-test was used to evaluate whether the removal of the non-significant terms affected model fit. Least square means were output from the model and post-hoc pairwise comparisons of means were performed. Bonferroni correction of the significance level was performed by dividing 0.05 by the number of estimated haplotypes.

RESULTS

Study population

A total of 10,629 individuals who presented to the emergency department for evaluation in the hours after MVC were screened, 1,416 were eligible, 969 consented to study participation, and 948 completed baseline evaluation. The recruitment flowchart, with major reasons for ineligibility and refusal, is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. Nine hundred and forty five individuals were successfully genotyped, 6 week follow-up evaluation was obtained in 859/945 (91%). Participants who were lost to follow-up were more likely to be younger, less-educated males; they did not, however, were different from the rest of the cohort in terms of baseline pain severity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study participants

| Characteristic | Baseline (n=948) | Lost to week 6 follow-up (n=89) | Week 6 follow-up (n=859) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, yrs (SD)a | 36 (13) | 31 (11) | 36 (13) |

| Range | 18–65 | 18–61 | 18–65 |

| Females, n (%)a | 575 (61) | 37 (42) | 538 (63) |

| Education, n (%)a | |||

| 8–11 yrs | 42 (4) | 6 (7) | 36 (4) |

| HS | 184 (19) | 27 (31) | 157 (18) |

| Post-HS | 57 (6) | 5 (6) | 52 (6) |

| Some college | 311 (33) | 34 (39) | 278 (32) |

| College | 237 (25) | 13 (15) | 225 (26) |

| Post-college | 113 (12) | 3 (3) | 110 (13) |

| Overall pain score (SD) | 5.5 (2.4) | 5.6 (2.5)b | 3.8 (2.8) |

| Pain severity, n (%) | |||

| None or mild (0–3 NRS) | 188 (20) | 16 (18)b | 417 (49) |

| Moderate (4–6 NRS) | 407 (43) | 37 (42)b | 273 (32) |

| Severe (7–10 NRS) | 344 (37) | 36 (40)b | 168 (20) |

| Pain interference (SD) | |||

| Total | - | - | 16.8 (18.1) |

| General activity | - | - | 2.8 (3.1) |

| Walking ability | - | - | 1.5 (2.6) |

| Mood | - | - | 2.9 (3.1) |

| Relations with other people | - | - | 1.5 (2.7) |

| Sleep | - | - | 2.9 (3.3) |

| Enjoyment of life | - | - | 2.3 (3.1) |

these characteristics were significantly different between those for whom 6 week data were obtained and those who were lost to follow-up (p < 0.05 for t-test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate);

baseline measurements; SD, standard deviation; HS, high school; NRS, numeric rating scale

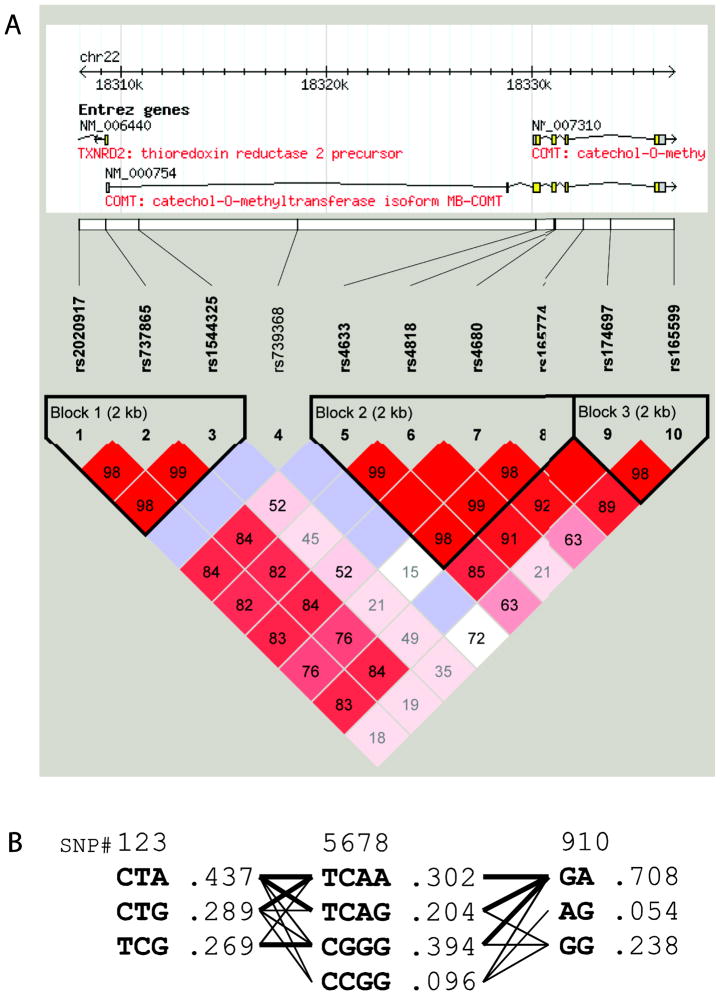

Genotyping results and haplotype estimation

Ten SNPs spanning the COMT gene were genotyped. Call rates were excellent (≥99.9%) for nine SNPs and good for rs165599 (96.4%). All SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (Chi-square p > .05, Supplementary Table 1). Using data from all 945 genotyped DNA samples, three haploblocks were identified by the method of confidence intervals (Gabriel et al. 2002) (Figure 1, A). Haploblocks 1, 2, and 3 included three, four, and three common haplotypes, respectively (Figure 1, B). Haplotypes in block 1 were denoted as A1–A3; haplotypes in block 3 were denoted as B1–B3. Haplotypes in block 2 corresponded to those identified in a previous study (Diatchenko et al. 2005) and included the low pain sensitivity (LPS) haplotype, the high pain sensitivity (HPS) haplotype, and two variants of the average pain sensitivity (APS1 and APS2) haplotype (Table 2).

Figure 1.

(A) COMT haploblocks and linkage disequilibrium; color and numbers represent D′ values (dark red=high inter-SNP D′; blue=statistically ambiguous high D′; white= statistically ambiguous low inter-SNP D′). (B) COMT haplotypes and haplotype frequencies; thin lines denote haplotype combinations with frequency >1%, thick lines with frequency > 10%.

Table 2.

Association of COMT haplotypes with pain and pain interference at week 6 after motor vehicle collision

| Haplotype | Number of haplotype alleles

|

F-value | P-valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Overall pain (SE) | |||||

| A1 (CTA) | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.2) | 0.71 | 0.489 |

| A2 (CTG) | 3.9 (0.1) | 3.8 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.4) | 0.29 | 0.749 |

| A3 (TCG) | 3.8 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.2) | 3.1 (0.4) | 2.96 | 0.051 |

| LPS (CGGG) | 3.8 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.1) | 3.3 (0.2) | 4.26 | 0.014 |

| HPS (CCGG) | 3.8 (0.1) | 4.1 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.9) | 0.74 | 0.473 |

| APS1 (TCAA) | 3.8 (0.1) | 4.0 (0.2) | 3.3 (0.3) | 2.58 | 0.077 |

| APS2 (TCAG) | 3.8 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.4) | 0.09 | 0.912 |

| B1 (GA) | 3.7 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.2) | 3.8 (0.1) | 0.70 | 0.491 |

| B2 (AG) | 3.8 (0.1) | 4.2 (0.3) | 5.5 (1.2) | 1.73 | 0.175 |

| B3 (GG) | 3.9 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.4) | 0.56 | 0.566 |

| Pain interference (SE) | |||||

| A1 (CTA) | 17 (1) | 18 (1) | 16 (1) | 0.42 | 0.651 |

| A2 (CTG) | 17 (1) | 17 (1) | 18 (2) | 0.04 | 0.965 |

| A3 (TCG) | 16 (1) | 19 (1) | 11 (2) | 5.54 | 0.004b |

| LPS (CGGG) | 17 (1) | 19 (1) | 14 (2) | 3.69 | 0.024 |

| HPS (CCGG) | 17 (1) | 17 (2) | 26 (6) | 1.04 | 0.349 |

| APS1 (TCAA) | 17 (1) | 18 (1) | 15 (2) | 1.46 | 0.230 |

| APS2 (TCAG) | 17 (1) | 17 (1) | 18 (3) | 0.01 | 0.994 |

| B1 (GA) | 15 (2) | 18 (1) | 17 (1) | 0.42 | 0.657 |

| B2 (AG) | 17 (1) | 17 (2) | 40 (8) | 3.85 | 0.021 |

| B3 (GG) | 18 (1) | 17 (1) | 14 (3) | 0.42 | 0.416 |

SE, standard error of mean;

genotypic model;

p-value is significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons

Haplotype frequencies were estimated using the Expectation-Maximization algorithm; verification using Bayesian estimation yielded virtually identical results (data not shown). Within each block, the above described common haplotypes accounted for approximately 99% of haplotypic diversity. Haplotype pair assignment probability for blocks 1, 2, and 3 was greater than .99 in 943, 941, and 911 individuals, respectively. Because haplotype uncertainty in a small proportion of individuals (<5% of the total sample) is unlikely to substantially bias study results (Kraft and Stram 2007), for further analyses these individuals were assigned to the most probable haplotype pair.

Bivariate analyses evaluating associations between COMT haplotype and persistent pain and pain interference 6 weeks after MVC

Under the genotypic model adjusted for study site, LPS haplotype was significantly protective against persistent pain at the nominal level alpha = 0.05 (Table 2). Three haplotypes were associated with increased pain interference at the nominal level alpha = 0.05: LPS, haplotype A3, and haplotype B2. After applying Bonferroni correction (alpha=0.05/10=0.005), only A3 remained a significant (p=0.004) predictor of pain interference. Individuals heterozygous at the A3 allele had the highest pain interference, those homozygous had the lowest pain interference, and individuals without a haplotype A3 had an intermediate phenotype.

Multivariate analyses including haplotype × haplotype and haplotype × sex interactions

Multivariate regression analyses with interaction terms were used to evaluate the potential influence of haplotype × haplotype and haplotype × sex interactions on pain and pain-related interference outcomes. Haplotypes associated at the p < 0.05 level with pain and pain-related interference outcomes in bivariate analyses (A3, LPS, and B2), sex, study site, and all possible two-way interactions were included as model terms. Interactions A3×LPS and B2×Sex were highly significant in both models (Table 3). Removal of non-significant and borderline-significant interaction terms did not affect the overall fit of the models (partial F-test p > 0.1), and both interactions (A3×LPS and B2×Sex) remained highly significant (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate regression analysis of pain outcomes at week 6 after motor vehicle collision

| Model terma | DF | Overall pain

|

Pain interference

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full model

|

Reduced model

|

Full model

|

Reduced model

|

||||||||||

| Type III SS | F Value | P Value | Type III SS | F Value | P Value | Type III SS | F Value | P Value | Type III SS | F Value | P Value | ||

| A3 | 1 | 54.4 | 7.27 | 0.0072 | 49.5 | 6.63 | 0.0102 | 3532.3 | 11.25 | 0.0008 | 3942.9 | 12.55 | 0.0004 |

| LPS | 1 | 3.7 | 0.49 | 0.4823 | 8.9 | 1.19 | 0.2759 | 58.6 | 0.19 | 0.6659 | 548.8 | 1.75 | 0.1866 |

| A3*LPS | 1 | 83.8 | 11.21 | 0.0008 | 73.3 | 9.8 | 0.0018 | 4739.9 | 15.09 | 0.0001 | 4957.7 | 15.78 | <.0001 |

| B2 | 1 | 68.1 | 9.11 | 0.0026 | 66.3 | 8.87 | 0.0030 | 4960.1 | 15.79 | <.0001 | 5657.5 | 18.01 | <.0001 |

| A3*B2 | 1 | 8.7 | 1.17 | 0.2801 | -- | -- | -- | 8.9 | 0.03 | 0.8664 | -- | -- | -- |

| LPS*B2 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0.8177 | -- | -- | -- | 33.4 | 0.11 | 0.7445 | -- | -- | -- |

| A3*Sex | 1 | 17.2 | 2.3 | 0.1296 | -- | -- | -- | 1257.0 | 4 | 0.0458 | -- | -- | -- |

| LPS*Sex | 1 | 9.7 | 1.29 | 0.2562 | -- | -- | -- | 268.8 | 0.86 | 0.3551 | -- | -- | -- |

| B2*Sex | 1 | 52.1 | 6.97 | 0.0085 | 54.5 | 7.29 | 0.0071 | 4861.0 | 15.48 | <.0001 | 5263.1 | 16.75 | <.0001 |

| Sex | 1 | 60.3 | 8.06 | 0.0046 | 143.6 | 19.21 | <.0001 | 1187.4 | 3.78 | 0.0522 | 1465.3 | 4.66 | 0.0311 |

| Site | 7 | 104.3 | 1.99 | 0.0533 | 106.6 | 2.04 | 0.0480 | 5536.8 | 2.52 | 0.0144 | 5611.1 | 2.55 | 0.0133 |

A3 is a haplotype TCG from haploblock 1; LPS is a haplotype CGGG from haploblock 2; B2 is a haplotype AG from haploblock 3; Sex was coded as male=1 and female=2

Subgroup analyses of haplotype×haplotype and haplotype×sex interactions

To better understand the identified A3×LPS interaction, the influence of an LPS allele on pain-related outcomes was compared among individuals in the MVC cohort with (410, 48%) and without (445, 52%) at least one A3 allele. Among those with one or more copies of the A3 allele, LPS haplotype had a nearly linear protective effect on pain-related outcomes, reducing overall pain severity by 0.8±0.3 units (p=0.002, Figure 2, A) and pain interference by 5.7±1.6 units (p=0.0004, Figure 2, B) for each LPS allele copy present. In contrast, among individuals without at least one A3 allele, LPS copy number had no effect on pain or pain interference (Figure 2).

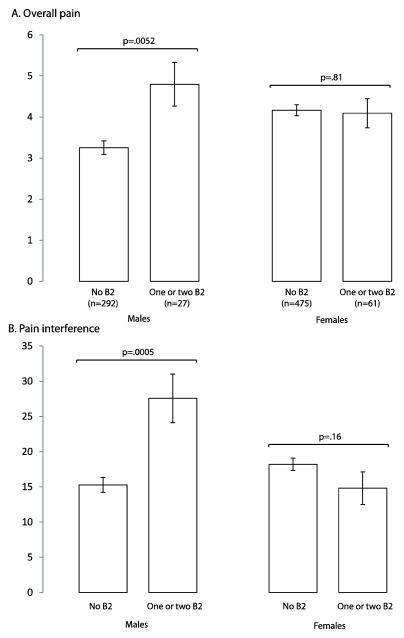

Figure 2.

Haplotype A3 x LPS interactions on overall pain (A) and pain interference (B) at week 6 after motor vehicle collision; plotted values are means ± standard errors of mean; p-values are from the additive genetic model.

To evaluate the B2×sex interaction, the effect of B2 haplotype on pain-related outcomes after MVC was compared among men (321, 37%) and women (538, 63%). Because of the low frequency of haplotype B2 (5.4%), heterozygous (n=83) and B2/B2 homozygous (n=5) individuals were combined into one category. Among men, the presence of one or two copies of haplotype B2 was associated with increased overall pain (by 1.5±0.5 scale units, p=0.005, Figure 3, A) and increased pain interference (by 12±4 scale units, p=0.0005, Figure 3, B). In contrast, among women the presence of one or two copies of haplotype B2 had no effect on pain and pain interference (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Haplotype B2 x sex interactions on overall pain (A) and pain interference (B) at week 6 after motor vehicle collision. Plotted values are means ± standard errors of mean.

To explore whether this sex difference in B2 haplotype influence might be limited to pre-menopausal women, we repeated the analysis among only men and women who were age 55 or older at the time of the MVC (n=108). Although the interaction between B2 haplotype and sex in this much smaller sample was not statistically significant (p = 0.25 for pain interference and p = 0.093 for pain), effect sizes were similar (data not shown). These data suggest that the interaction between B2 haplotype and sex may not be limited to premenopausal women alone.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort study of adult European Americans presenting to the emergency department after MVC, COMT haplotype×haplotype and haplotype×sex interactions were much stronger predictors of pain outcomes 6 weeks after MVC than individual haplotypes. In the overall cohort, the LPS haplotype in the COMT coding region was nominally associated with pain and interference, and haplotype A3 in the P2 promoter region predicted pain interference with a significant overdominant effect. However, as evident from the F-values in Tables 2 and 3, the interaction of the A3 and LPS haplotypes was much more strongly associated with pain and pain interference outcomes after MVC than either haplotype alone. (The fact that the LPS haplotype was largely dependent on distal P2 promoter genotype suggests that the COMT P2 locus is also functional.) Similarly, the effect of haplotype B2 in the 3′-untranslated region was associated with increased overall pain and pain interference after MVC in men, but not in women.

The present finding that COMT distal P2 promoter genotype influences pain outcomes after MVC is consistent with current understanding of COMT isoform expression and physiology. The P2 promoter influences MB-COMT expression, and MB-COMT is the predominant form of the enzyme in the central nervous system (CNS) (Chen et al. 2004). Thus genetic variants in P2 are most likely to affect the function of important pain pathways in the CNS. In addition, the MB-COMT isoform also has a higher affinity to catecholamines at the physiologic concentrations of catecholamines found in the brain (Roth 1992).

Our findings of the interaction between genotypes in the coding region of COMT and genotypes in the P2 promoter region are in accordance with several previous studies. In a study examining the influence of COMT polymophisms on brain function, two SNPs in the P2 region, rs737865 and rs2075507, when analyzed together with the Val158Met polymorphism, were shown to critically affect prefrontal cortex function (Meyer-Lindenberg et al. 2006). Of note, allele C at rs737865 is a tagging allele for haplotype A3 in our study (Figure 1, B) and is in high linkage disequilibrium with HindIII, a potentially functional deletion in the P2 promoter (Palmatier et al. 2004). In another study, allele C at rs737865 was found to be associated with reduced COMT transcription in the central nervous system (Bray et al. 2003). Finally, interactions between P2 promoter region genetic variants and the coding region variants have been associated with vulnerability to schizophrenia (Shifman et al. 2002).

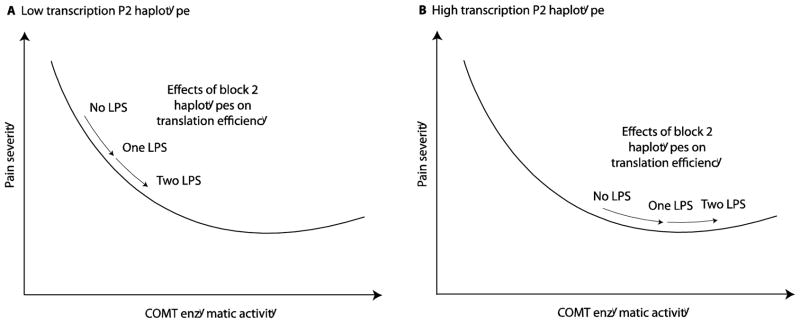

One of the hypothetical mechanistic explanations of the interaction between promoter P2 variants and coding region haplotypes employs a potentially non-linear relationship between COMT activity and vulnerability to persistent pain (Figure 4). The non-linear, U-shaped, dose-response relationship with pain sensitivity has been previously documented for yohimbine (alpha-adrenoceptor agonist) and dopamine (Paalzow and Paalzow 1983; Pelissier et al. 2006). The proposed model may help to explain why the effect of COMT central block haplotypes is prominent with some promoter P2 haplotypes (e.g. low transcription in presence of haplotype A3 at promoter P2) and non-significant in others. Additionally, in our study haplotype A3 (previously shown to be associated with reduced transcription of COMT) (Bray et al. 2003) had significant main effect on pain outcomes, resulting in substantially higher pain interference in A3/A3 homozygous individuals.

Figure 4.

Hypothesized mechanistic explanation of the interaction between P2 promoter and COMT coding region haplotypes. (A) In presence of the COMT promoter P2 haplotype associated with low levels of COMT transcription, the effect of the haplotypes covering the coding region of COMT is prominent because of the steep dose-response curve; (B) In absence of the “low transcription” P2 haplotype the total enzymatic activity is shifted to the right so that the effect of the haplotypes in the coding gene region is reduced because of the flattened dose-response curve.

In this study we also observed marked sexual dimorphism in the influence of COMT genotypes on pain outcomes after motor vehicle collision. The strong effect of the B2 haplotype (covering intron 5, exon 6, and 3′-untranslated region) on pain outcomes was present only in males. This finding is in accordance with previous studies showing differences in males and females in COMT function: COMT activity in the prefrontal cortex, the brain region responsible for cognitive and emotional processing of pain, has been shown to be higher in males than in females (Chen et al. 2004). These observations are also supported by animal studies, which found that knocking out the COMT gene results in increased dopamine in the frontal cortex in males, but not in females (Gogos et al. 1998). Additionally, genetic variations in COMT have also been shown to have sexually-dimorphic effects in several neuropsychiatric conditions. COMT Val158Met (rs4680) genotype has been found to influence the risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder (Pooley et al. 2007; Katerberg et al. 2010) and Intelligence Quotient (Barnett et al. 2009) in males but not in females, and COMT genotype (rs737865 and rs165599) has been found to influence schizophrenia in females, but not in males (Shifman et al. 2002; Talkowski et al. 2008). While the sexually dimorphic effects of COMT have been attributed to estrogen (a potent inhibitor of COMT transcription) (Jiang et al. 2003), in our subgroup analyses of the participants age 55–65 effect size differences between men and women were unchanged. This suggests that the sexually dimorphic effects of haplotype B2 may not be due to estrogen alone.

One of the limitations of our study is that we did not utilize ancestry informative markers to control for population stratification in our study. However, self-reported race or ethnicity has been shown to be an accurate means of determining European American ancestry in genetic association studies (Tang et al. 2005). Additionally, all assessed polymorphisms were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium, suggesting little, if any, stratification in the studied samples. Adjustment for study site in the regression models was also used to minimize the effect of population variations across geographic regions of the Eastern United States. In addition, the results of our study are generalizable only to European Americans, and the influence of COMT genotype on pain outcomes after other traumatic events is unknown. Also, as reflected by our use of the term “persistent pain” throughout the manuscript, while six weeks of pain is an important health outcome in itself, pain of this duration does not yet meet the definition of chronic (i.e. pain lasting 2–3 months (Wolfe et al. 1990; Macrae and Davies 1999)). Future studies should evaluate the influence of COMT genotype on chronic pain, both after MVC and after other types of trauma exposure.

Finally, although we present no replication of our finding of the interaction between COMT haplotypes, our results are in strong agreement with previous literature on the role of catechol-O-methyltransferase and its polymorphisms in pain perception and chronic pain development (Diatchenko et al. 2005; Nackley et al. 2006a; Meyer-Lindenberg et al. 2006; Shifman et al. 2002; Gaysina et al. 2013; Shibata et al. 2009).

In conclusion, this is the first report of the association between COMT genetic variants and persistent pain and pain interference after MVC. Our study confirms that the effect of COMT polymorphisms on persistent pain is best evaluated using a haplotype-based approach that takes into account interactions between haplotypes in the distal promoter, coding, and 3′-untranslated region, and sex differences. Further studies are needed to investigate the biological substrate for these interactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health, under Award Number R01AR056328 to Dr. Samuel A. McLean. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Diatchenko is a co-founder and equity stock holder in Algynomics, Inc. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barbosa FR, Matsuda JB, Mazucato M, de Castro Franca S, Zingaretti SM, da Silva LM, et al. Influence of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) gene polymorphisms in pain sensibility of Brazilian fibromialgia patients. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(2):427–430. doi: 10.1007/s00296-010-1659-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett JH, Heron J, Goldman D, Jones PB, Xu K. Effects of catechol-O-methyltransferase on normal variation in the cognitive function of children. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(8):909–916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08081251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijur PE, Latimer CT, Gallagher EJ. Validation of a verbally administered numerical rating scale of acute pain for use in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(4):390–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray NJ, Buckland PR, Williams NM, Williams HJ, Norton N, Owen MJ, et al. A haplotype implicated in schizophrenia susceptibility is associated with reduced COMT expression in human brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(1):152–161. doi: 10.1086/376578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lipska BK, Halim N, Ma QD, Matsumoto M, Melhem S, et al. Functional analysis of genetic variation in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): effects on mRNA, protein, and enzyme activity in postmortem human brain. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(5):807–821. doi: 10.1086/425589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen H, Neumann L, Glazer Y, Ebstein RP, Buskila D. The relationship between a common catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism val(158) met and fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(5 Suppl 56):S51–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Belfer I, et al. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(1):135–143. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, Maixner W. Responses to Drs. Kim and Dionne regarding comments on Diatchenko, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphisms are associated with multiple pain-evoking stimuli. Pain 2006; 125: 216–24. Pain. 2007;129(3):366–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Katz NP, et al. Core outcome measures for chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2005;113(1–2):9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel SB, Schaffner SF, Nguyen H, Moore JM, Roy J, Blumenstiel B, et al. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science. 2002;296(5576):2225–2229. doi: 10.1126/science.1069424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaysina D, Xu MK, Barnett JH, Croudace TJ, Wong A, Richards M, et al. The catechol-O-methyltransferase gene (COMT) and cognitive function from childhood through adolescence. Biol Psychol. 2013;92(2):359–364. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SZ, Dover GC, Wallace MR, Sack BK, Herbstman DM, Aydog E, et al. Biopsychosocial influence on exercise-induced delayed onset muscle soreness at the shoulder: pain catastrophizing and catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) diplotype predict pain ratings. Clin J Pain. 2008a;24(9):793–801. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31817bcb65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SZ, Wallace MR, Wright TW, Moser MW, Greenfield WH, 3rd, Sack BK, et al. Evidence for a biopsychosocial influence on shoulder pain: pain catastrophizing and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) diplotype predict clinical pain ratings. Pain. 2008b;136(1–2):53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogos JA, Morgan M, Luine V, Santha M, Ogawa S, Pfaff D, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase-deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic changes in catecholamine levels and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(17):9991–9996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gursoy S, Erdal E, Herken H, Madenci E, Alasehirli B, Erdal N. Significance of catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism in fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2003;23(3):104–107. doi: 10.1007/s00296-002-0260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocking LJ, Smith BH, Jones GT, Reid DM, Strachan DP, Macfarlane GJ. Genetic variation in the beta2-adrenergic receptor but not catecholamine-O-methyltransferase predisposes to chronic pain: results from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study. Pain. 2010;149(1):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen LM, Schistad EI, Storesund A, Pedersen LM, Rygh LJ, Roe C, et al. The COMT rs4680 Met allele contributes to long-lasting low back pain, sciatica and disability after lumbar disc herniation. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(7):1064–1069. doi: 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2011.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Xie T, Ramsden DB, Ho SL. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase down-regulation by estradiol. Neuropharmacology. 2003;45(7):1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katerberg H, Cath DC, Denys DA, Heutink P, Polman A, van Nieuwerburgh FC, et al. The role of the COMT Val(158)Met polymorphism in the phenotypic expression of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(1):167–176. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller S, Bann CM, Dodd SL, Schein J, Mendoza TR, Cleeland CS. Validity of the brief pain inventory for use in documenting the outcomes of patients with noncancer pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(5):309–318. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200409000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft P, Stram DO. Re: the use of inferred haplotypes in downstream analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(4):863–865. doi: 10.1086/521371. author reply 865–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Cutler DJ, Zwick ME, Chakravarti A. Haplotype inference in random population samples. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(5):1129–1137. doi: 10.1086/344347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotta T, Vidgren J, Tilgmann C, Ulmanen I, Melen K, Julkunen I, et al. Kinetics of human soluble and membrane-bound catechol O-methyltransferase: a revised mechanism and description of the thermolabile variant of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 1995;34(13):4202–4210. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macrae WA, Davies DHO. Chronic post-surgical pain. In: Crombie LSIK, Croft P, Von Korff M, LeResche L, editors. Epidemiology of Pain. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1999. pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Lindenberg A, Nichols T, Callicott JH, Ding J, Kolachana B, Buckholtz J, et al. Impact of complex genetic variation in COMT on human brain function. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(9):867–877. 797. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Shabalina SA, Tchivileva IE, Satterfield K, Korchynskyi O, Makarov SS, et al. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes modulate protein expression by altering mRNA secondary structure. Science. 2006a;314(5807):1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1131262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nackley AG, Tan KS, Fecho K, Flood P, Diatchenko L, Maixner W. Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition increases pain sensitivity through activation of both beta(2)- and beta(3)-adrenergic receptors. Pain. 2006b;128(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholl BI, Holliday KL, Macfarlane GJ, Thomson W, Davies KA, O’Neill TW, et al. No evidence for a role of the catechol-O-methyltransferase pain sensitivity haplotypes in chronic widespread pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(11):2009–2012. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.126086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paalzow GH, Paalzow LK. Yohimbine both increases and decreases nociceptive thresholds in rats: evaluation of the dose-response relationship. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1983;322(3):193–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00500764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier MA, Pakstis AJ, Speed W, Paschou P, Goldman D, Odunsi A, et al. COMT haplotypes suggest P2 promoter region relevance for schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9(9):859–870. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier T, Laurido C, Hernandez A, Constandil L, Eschalier A. Biphasic effect of apomorphine on rat nociception and effect of dopamine D2 receptor antagonists. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;546(1–3):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platts-Mills TF, Ballina L, Bortsov AV, Soward A, Swor RA, Jones JS, et al. Using emergency department-based inception cohorts to determine genetic characteristics associated with long term patient outcomes after motor vehicle collision: methodology of the CRASH study. BMC Emerg Med. 2011;11:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-227X-11-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pooley EC, Fineberg N, Harrison PJ. The met(158) allele of catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder in men: case-control study and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(6):556–561. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter M, Hennig J. Association of the functional catechol-O-methyltransferase VAL158MET polymorphism with the personality trait of extraversion. Neuroreport. 2005;16(10):1135–1138. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200507130-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth JA. Membrane-bound catechol-O-methyltransferase: a reevaluation of its role in the O-methylation of the catecholamine neurotransmitters. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;120:1–29. doi: 10.1007/BFb0036121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata K, Diatchenko L, Zaykin DV. Haplotype associations with quantitative traits in the presence of complex multilocus and heterogeneous effects. Genet Epidemiol. 2009;33(1):63–78. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shifman S, Bronstein M, Sternfeld M, Pisante-Shalom A, Lev-Lehman E, Weizman A, et al. A highly significant association between a COMT haplotype and schizophrenia. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(6):1296–1302. doi: 10.1086/344514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Maixner DW, Greenspan JD, Dubner R, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, et al. Potential genetic risk factors for chronic TMD: genetic associations from the OPPERA case control study. J Pain. 2011;12(11 Suppl):T92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka MN, Buhler M, Schumann G, Klein S, Hu XZ, Moayer M, et al. Gene-gene effects on central processing of aversive stimuli. Mol Psychiatry. 2007;12(3):307–317. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talkowski ME, Kirov G, Bamne M, Georgieva L, Torres G, Mansour H, et al. A network of dopaminergic gene variations implicated as risk factors for schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(5):747–758. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tander B, Gunes S, Boke O, Alayli G, Kara N, Bagci H, et al. Polymorphisms of the serotonin-2A receptor and catechol-O-methyltransferase genes: a study on fibromyalgia susceptibility. Rheumatol Int. 2008;28(7):685–691. doi: 10.1007/s00296-008-0525-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H, Quertermous T, Rodriguez B, Kardia SL, Zhu X, Brown A, et al. Genetic structure, self-identified race/ethnicity, and confounding in case-control association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76(2):268–275. doi: 10.1086/427888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunbridge EM, Harrison PJ. Importance of the COMT gene for sex differences in brain function and predisposition to psychiatric disorders. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2011;8:119–140. doi: 10.1007/7854_2010_97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meurs JB, Uitterlinden AG, Stolk L, Kerkhof HJ, Hofman A, Pols HA, et al. A functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene is associated with osteoarthritis-related pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(2):628–629. doi: 10.1002/art.24175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Alarcon G, Fragoso JM, Cruz-Robles D, Vargas A, Lao-Villadoniga JI, Garcia-Fructuoso F, et al. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene haplotypes in Mexican and Spanish patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(5):R110. doi: 10.1186/ar2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(2):160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Heitzeg MM, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu K, Xu Y, et al. COMT val158met genotype affects mu-opioid neurotransmitter responses to a pain stressor. Science. 2003;299(5610):1240–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.1078546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.