Abstract

Learning about a moving visual stimulus was examined in zebrafish larvae using an automated imaging system and a t1-t2 design. In three experiments, zebrafish larvae were exposed to one of two inputs at t1 (either a gray bouncing disk or an identical but stationary disk) followed by a common test at t2 (the gray bouncing disk). Using 7 days post-fertilization (dpf) larvae and 12 stimulus exposures, Experiment 1 established that these different treatments produced differential responding to the moving disk during testing. Larvae familiar with the moving test stimulus were significantly less likely to be still in its presence than larvae that had been exposed to the identical but stationary stimulus. Experiment 2 confirmed this result in 7 dpf larvae and extended the finding to 5 and 6 dpf larvae. Experiment 3 found differential responding to the moving test stimulus with 4 or 8 stimulus exposures but not with just one exposure in 7 dpf larvae. These results provide evidence for learning in very young zebrafish larvae. The merits and challenges of the t1-t2 framework to study learning are discussed.

Keywords: activity, avoidance, habituation, learning, thigmotaxis, t1-t2 design, zebrafish larvae

1. Introduction

The developing zebrafish ( Danio rerio) has emerged as an important model system in biology, environmental toxicology, and neuroscience. Its small size, rapid development of sensory and motor functions, and its behavioral diversity combine to make the larval zebrafish an ideal candidate for high throughput automated analyses of behavior essential for rapid mutagenesis screening and detection of the effects of pharmaceutical and chemical agents. By 7 days post-fertilization (dpf), the zebrafish larva is approximately 5 mm long. It has a complex swimming repertoire consisting of several topographically distinct components that help co-ordinate its movements in three dimensional space at a variety of speeds (Wolman & Granato, 2012). This finely tuned motor system coupled with a highly developed tetrachromatic visual system enables the 7 dpf zebrafish larva to track and capture small prey, to avoid predators including adult zebrafish, and to maneuver without collision in typically densely populated larval colonies. Automated medium and high throughput assays have already been established to study spontaneous and stimulus-induced locomotor activity, social proximity, and visually-induced avoidance behavior in zebrafish larvae (Chen, Huang, Zheng, Simonich, Bai, Tanguay & Dong, 2011; Colwill & Creton, 2011a,b; Creton, 2009; Kokel & Peterson, 2011; Pelkowski, Kapoor, Richendrfer, Wang, Colwill & Creton, 2011; Powers, Wrench, Ryde, Smith, Seidler & Slotkin, 2010; Selderslaghs, Hooyberghs, DeCoen & Witters, 2010). Here, we report three experiments using a semi-automated behavioral assay to study the effects of prior experience (learning) in zebrafish larvae.

Arguably the simplest procedure for studying learning is the repeated presentation of a stimulus. Demonstrations of habituation, sensitization, imprinting, and the mere exposure effect as well as studies of perceptual learning, latent inhibition, expectancy violation, priming and recognition memory all employ this basic procedure. However, proper assessment of the learning produced by this procedure is a more complicated matter. For example, many studies using this procedure to show habituation typically rely on the demonstration of a significant decline in responding to the stimulus, usually between the first and last presentations. Such an approach is inadequate for several reasons (Davis, 1970; Davis & Wagner, 1968, 1969; Rescorla, 1988; Rescorla & Holland, 1976). Foremost, this design confounds the conditions for learning (input) with the assessment of learning (test) which can lead to serious misunderstandings about the nature of that learning. For example, Best, Berghmans, Hunt, Clarke, Fleming, Goldsmith, and Roach (2008) recently examined how the interstimulus interval (ISI) affected the rate of response decrement to an iterative auditory stimulus. Using a between-subjects design, different groups of 7 dpf WIK larvae were exposed to repeated stimulus presentations at 1, 5 or 20 sec intervals, and the distance moved in the second immediately following each stimulus presentation was measured. The decline in the distance moved between the initial and terminal stimulus presentations was most pronounced in the larvae with the 1 sec ISI. For the larvae with the 20 sec ISI, there was no significant change in distance moved. On the basis of these results, the authors concluded that habituation was slower with longer ISIs.

The opposite view that habituation is, in fact, superior with spaced stimulus presentations has been reached in studies that do not confound variations in the conditions for learning with concomitant variations in the testing conditions. For example, Wolman, Jain, Liss, and Granato (2011) exposed 6 dpf larvae in groups of 20 to a two hour habituation procedure consisting of a series of 480 1-sec dark flashes with an ISI of 15 sec. For one group, the series was split into 4 blocks of 120 flashes punctuated by 10 min intervals; for the other group, the stimuli were presented in a single block (massed). All larvae were then tested with a series of 10 1-sec dark flashes with an ISI of 60 sec. Larvae that had received a spaced pattern of stimulation showed a longer-lasting response decrement (dark flash failed to elicit an O-bend response) than those that had received a massed pattern of stimulation.

To guard against the potential pitfalls that can arise from confounding the conditions for learning with the assessment of that learning, Rescorla and Holland (1976) formulated an important general framework for all studies of elementary learning processes. They proposed the t1-t2 design, in which the input phase of a learning procedure is varied within or between animals at one point in time (t1) while the test phase is kept constant within or between animals and occurs at a subsequent point in time (t2). Intrinsic to this t1-t2 framework is the recognition that an appropriate control for determining learning about a stimulus is to compare behavior to that stimulus in a common test between animals that did or did not receive prior exposure to that stimulus. A significant difference in behavior during that common test would provide evidence for learning about the stimulus during the input phase.

We implemented the t1-t2 framework in a between-subjects design to study learning about a moving visual stimulus. Using a modified version of our automated visual avoidance assay (Creton, 2009; Pelkowski et al., 2011; Richendrfer, Pelkowski, Colwill & Creton, 2012), larvae in Group B were exposed to 5 min periods of a plain white background alternating with a gray bouncing disk superimposed on the white background. Control larvae in Group S received the same exposure treatment except that the disk did not move. In previous work, we have demonstrated that larvae will swim away from a bouncing but not a stationary visual stimulus. The input phase was immediately followed by identical testing for both groups. Testing began with a presentation of the plain white background for 5 min immediately followed by presentation of the gray bouncing disk for 5 min. Using 7 dpf larvae, Experiment 1 established that 12 exposures to either a bouncing or stationary disk at t1 produced differential responding to the bouncing disk during testing at t2. Experiment 2 replicated the procedure of Experiment 1 with 5, 6, and 7 dpf larvae. Experiment 3 used the same procedure as Experiment 1 with 7 dpf larvae but with fewer stimulus exposures (1, 4 or 8) in the input phase.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Embryo collection and rearing

Embryos were collected from a breeding population of adult male and female wild type zebrafish originally obtained from Carolina Biological Supply Co.(Burlington, NC) and maintained at Brown University as a genetically diverse outbred strain. The fish were housed in 20 gallon tanks at 28°C and maintained on a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle. They were fed a combination of frozen or fresh brine shrimp and flake fish food once or twice per day. Embryos were collected for two hours following light onset using shallow trays placed in the bottom of the tanks.

Embryos were grown at a density of approximately 250 embryos per liter of egg water (60 mg/L sea salt, Instant Ocean, in deionized water and 0.25 mg/L methylene blue as a mold inhibitor) in 2L plastic breeding tanks (Aquatic Habitats) and incubated at 28°C. Unfertilized eggs were removed at 1 dpf. Dead larvae and other particles were removed on a daily basis and egg water in each tank was partially changed every other day to maintain water quality. Food supplements were not provided during this period because the larvae absorb nutrition from their yolk sac through 7 dpf (Jardine & Litvak, 2003).

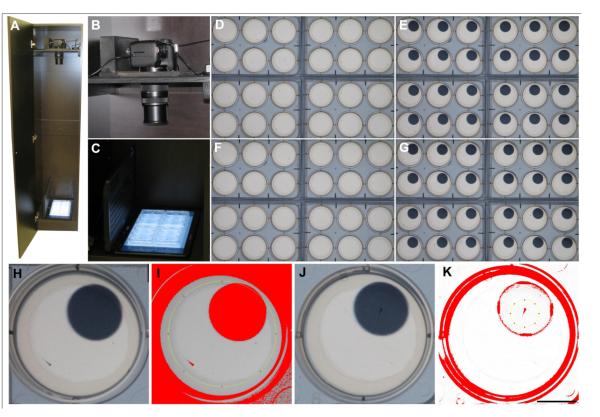

2.2 Image collection

Details of the imaging system have been described previously (Pelkowski et al. 2011). Flat-bottom 6-well plates (Corning Costar no. 3506) were optimized for larval imaging by filling each well with 5 ml of agarose (0.5% w/v in deionized water). Agarose was allowed to set and then a center portion was punched out to create a 27 mm diameter × 5 mm deep swimming area surrounded by an agarose ring (Creton, 2009). Four 6-well plates with one larva per well were placed on the LCD screen (1366 × 768 pixel resolution and a brightness of 220 cd/m2) of an inverted laptop on the bottom shelf of a tall cabinet (Fig 1A-1C). A plastic diffuser (Pendaflex 52345) was placed between the multiwell plates and the screen to avoid moiré patterns. Larvae were imaged from above by a 15 megapixel Canon EOS Rebel T1i digital camera with an EF-S 55-250mm f/4.0-5.6 IS zoom lens using Canon’s remote capture software. The following camera settings were used: image quality = 4752 × 3168 pixels, high-quality JPEG compression (0.6 MB/image), lamp = outdoor, iso-speed = 100, F = 5.0, and exposure time (Tv) = 1/20 s. In Experiment 3, we also used an 18 megapixel Canon EOS Rebel T2i digital camera with an EF-S 55-250mm f/4.0-5.6 IS zoom lens with image quality = 5184 × 3456 pixels. All other camera settings remained the same.

Figure 1. The zebrafish imaging system.

A) Camera mounted on top shelf of cabinet with laptop on bottom. B) Camera is mounted on an L-shaped bracket attached to top shelf. C) A laptop is used to display PowerPoint presentations to the larvae in multiwell plates. D-G) PowerPoint slides used for the single stimulus learning assay. D and E are the input (t1) slides that alternated every 5 min. D also served as the set up template with white disks to ensure that the multiwell plates were situated correctly. E is the stimulus exposure slide with gray bouncing disks on one side and gray stationary disks on the other (sides are counterbalanced across larvae). F and G are the two 5 min test (t2) slides. F is identical to D and immediately preceded G. In G, the gray bouncing disk appeared in all wells. In this example, the larvae on the left had been exposed to the moving disk but those on the right had not. H-K) Image analysis. Images were first opened in ImageJ (H), a region of interest (yellow ring) was set to encompass the entire swimming area, and larvae were separated from the larger disk using ImageJ’s particle analysis (I). When a larva overlapped with the disk (J), background subtraction was applied and a region of interest was placed around the larva (K). Scale bar in K = 1 cm.

2.3 Behavioral testing

In all three experiments, larvae were first ex posed to alternating 5 min periods of a white background (RGB values were 255, 255, 255) with no visual stimuli (Fig. 1D) and 5 min periods of either a gray moving disk (1.35 cm in diameter) or an identical gray but stationary disk (RGB values were 120, 120, 120) on a white background (Fig. 1E). Exposure (t1) was immediately followed by testing (t2). For testing, all larvae were exposed to a 5 min period of the plain white background (Fig. 1F) followed by a 5 min presentation of the gray moving disk (Fig. 1G). Images were captured at the fastest rate allowed by the camera (6 sec), a setting that generated 49 or 50 images in the 5 min recording periods. The visual stimuli were created in Microsoft PowerPoint. Using the custom animation feature, the moving gray disk was programmed to bounce back and forth in a straight line across the upper half of each well at a rate of 1.65 cm/s. The gray stationary disk was also presented in the upper half of each well but remained fixed in the center of the path traveled by the bouncing disk. Whether the stationary or bouncing disks appeared in the 12 wells on the right half or on the left half of the PowerPoint display was counterbalanced across subjects.

2.3.1 Experiment 1: Basic demonstration of single stimulus learning

The input phase consisted of 12 5-min presentations of a white background (Fig 1D) alternating with 12 5-min presentations of either the gray bouncing disk or the gray stationary disk (Fig 1E) for 120 min. The test phase was the same for all larvae and consisted of a 5-min presentation of the white background (Fig 1F) followed by a 5-min presentation of the gray bouncing disk (Fig 1G). There was no delay between the test phase and the end of the exposure treatment. Twenty-four larvae from the same egg collection were randomly assigned to either the bouncing (Group B) or stationary (Group S) stimulus conditions. Three larvae were later discarded due to physical abnormalities leaving 23 subjects in Group B and 22 subjects in Group S.

2.3.2 Experiment 2: Effect of larval age

The procedure was identical to that described for Experiment 1. However, larvae from the same egg collection were randomly divided into three groups of 48 larvae for stimulus exposure and testing at one of three ages: 5, 6 or 7 dpf. Within each of these age groups, 24 larvae were randomly assigned to the bouncing disk condition (Group B) and 24 larvae to the stationary disk condition (Group S). Data from one 7 dpf larva in the stationary disk condition were discarded because the larva did not move throughout the experiment.

2.3.3 Experiment 3: Effect of number of stimulus exposures

The basic procedure was the same as that described for Experiment1 except that the number of stimulus exposures alternating with the white background in the input phase was reduced from 12 to 8, 4, or 1. The test phase was identical to that of Experiment 1 and began immediately after the last designated stimulus presentation. Consequently, the interval between the start of exposure and the start of testing increased as the number of exposures increased. All larvae were 7 dpf and obtained from multiple egg collections. There were 24 larvae in each of the two groups (Groups B and S) at each of the three levels of stimulus exposure (1, 4, or 8). Data from one larva in the 4 exposure condition with the stationary disk (Group S-4) were excluded from analysis because the larva did not move throughout the experiment.

2.4 Image analysis and quantification of behavior

Images were imported into ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/index.html) and an automatic macro was used to apply a threshold, identify the larvae (and exclude the disk) based on particle size, and obtain the X,Y coordinates of each larva’s centroid. The automatic macro failed to identify X,Y co-ordinates when the larvae were on top of or abutting the bouncing disk. The missing values were obtained by using the automatic macro to subtract the background and then manually adjusting the contrast to reveal the darker larvae against the relatively lighter gray disk , using the backspace key to erase noise from the disk as necessary. Following image analysis, the X,Y coordinates were imported into a customized Microsoft Excel template.

Four behavioral measures, avoidance, edge, still and swim rate, were calculated to capture a range of potential defensive responses to a perceived threat, the bouncing disk. Based on prior work, we hypothesized that the larvae might (1) swim away from the bouncing disk (to evade capture), (2) display thigmotaxis and move to the edge of the well (to seek refuge), (3) freeze (to avoid detection), or (4) be hyperactive and erratic (to confuse a potential predator). Avoidance of the bouncing disk was measured by comparing the Y co-ordinate of the larva’s centroid with the Y coordinate of the midpoint of the larva’s well for each image. If the Y value of the larva’s centroid was equal to or larger than the Y value of the well’s midpoint, the larva was located in the half of the well opposite from where the visual stimulus was presented. The avoidance index was calculated in the same way when the disk was absent on the white background. To determine if the larva was in the center of the well or at the edge of the well, the values of the X,Y co-ordinates of the larva’s centroid and the values of the X,Y co-ordinates of the well’s midpoint were used to calculate the larva’s distance from the midpoint. If this distance was equal to or larger than the value of the well’s radius divided by the square root of 2, the larva was located at the edge of the well. Estimates of swim rate and still were derived in two steps. First, the values of the X,Y coordinates of the larva’s centroid were used to calculate the displacement in pixels of the centroids between pairs of consecutive images. To calculate swim rate in mm/min, this displacement value was converted to mm and multiplied by 10. To calculate still, this displacement value was converted to mm and if less than 0.3 mm, the larva was recorded as still. Measurements of still and swim rate yielded one fewer data points than the measurements of avoidance and edge in each of the three 5-min recording periods analyzed. Means were calculated for each measure in each 5-min recording period and converted into percentages for avoidance, edge and still. Measurements of larval location and locomotion were taken in the horizontal plane only.

2.5 Statistical analyses

For each response measure, means were compared between Groups B and S using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA, SPSS v. 19.0) with Group (2 levels) as the between subjects factor. A Bonferroni correction procedure was used to adjust significance levels for analyses involving overlapping raw datasets between percent avoidance and percent edge and between percent still and swim rate. The corrected p value to test for significance was .025.

3. Results

For all three experiments, statistical analyses were performed on four response measures: mean percent avoidance, mean percent edge, mean percent still, and mean swim rate (mm/min). Means were compared for three 5-min recording periods: the first 5 min presentation of the plain white background, the 5 min presentation of white in the test phase, and the 5 min presentation of the gray bouncing disk in the test phase. By examining responses in the first 5 min, we were able to determine if random assignment was adequate or if matching was needed to equate Groups B and S.

3.1 Response measures in the first 5 min

Means for the first 5 min white presentation are summarized in Table I for each experiment. No statistically significant differences were found on any of the response measures between the larvae assigned to Groups B and S in Experiment 1 (Fs<1). For Experiment 2, there were no significant differences on any response measure between Groups B and S at 5 dpf, Fs(1,46) ≤2.3, ps>.10, at 6 dpf, Fs(1,46) ≤ 1.0, ps>.10, or at 7 dpf, Fs(1,46) < 1.7, ps>.10, although the difference in the starting location (percent avoidance) of the larva at 5 dpf was marginally nonsignificant, F(1,46) = 4.6, p>.03. For Experiment 3, there were no significant differences on any response measure between Groups B and S in the 8 exposure condition, Fs(1,46) ≤ 1.6, ps>.10, or in the 1 exposure condition, Fs(1,46) ≤ 1.2, ps>.10. In the 4 exposure condition, there was a significant difference in percent edge, F(1,45) = 5.4, p<.025, but not on any other measure, Fs (1,45) ≤ 2.3, ps >.10. Random assignment of larvae to the bouncing or stationary stimulus conditions in the input phase was generally satisfactory in ensuring no statistically significant group differences prior to the first stimulus exposure.

TABLE I.

Means (±SEMs) for first 5 min on white background

Groups: B = bouncing disk, S = stationary disk

| %Avoidance | %Edge | %Still | Swim rate (mm/min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Exp 1 | ||||

| Group B | 53.5 (±6.1) | 89.0 (±2.4) | 4.7 (±3.7) | 93.9 (±8.6) |

| Group S | 53.3 (±6.6) | 91.8 (±2.1) | 11.8 (±6.3) | 83.1 (±8.1) |

|

| ||||

| Exp 2 | ||||

| 5 dpf | ||||

| Group B | 58.3 (±7.4) | 79.0 (±5.4) | 37.7 (±9.1) | 48.2 (±8.9) |

| Group S | 78.6 (±5.8) | 76.8 (±6.5) | 55.9 (±9.2) | 29.3 (±8.6) |

|

| ||||

| 6 dpf | ||||

| Group B | 60.0 (±6.1) | 75.8 (±4.4) | 23.8 (±6.9) | 62.0 (±7.5) |

| Group S | 52.0 (±6.4) | 78.9 (±4.8) | 34.6 (±8.3) | 55.5 (±8.9) |

|

| ||||

| 7 dpf | ||||

| Group B | 56.4 (±5.1) | 74.8 (±4.0) | 7.3 (±4.3) | 78.4 (±6.1) |

| Group S | 55.2 (±7.1) | 77.5 (±4.7) | 17.9 (±7.1) | 66.9 (±8.7) |

|

| ||||

| Exp 3 | ||||

| Group B-8 | 54.3 (±5.7) | 79.3 (±3.9) | 16.7 (±6.0) | 73.8 (±8.5) |

| Group S-8 | 43.7 (±6.0) | 72.0 (±5.5) | 20.8 (±7.5) | 67.3 (±8.9) |

|

| ||||

| Group B-4 | 48.7 (±5.3) | 80.1 (±3.7) | 16.3 (±5.6) | 81.9 (±8.5) |

| Group S-4 | 56.5 (±7.5) | 90.3 (±2.4) | 30.1 (±8.7) | 61.7 (±10.5) |

|

| ||||

| Group B-1 | 57.4 (±4.1) | 77.3 (±3.9) | 4.6 (±3.2) | 99.5 (±5.6) |

| Group S-1 | 55.1 (±3.3) | 74.7 (±4.2) | 0.9 (±0.8) | 97.1 (±5.6) |

|

| ||||

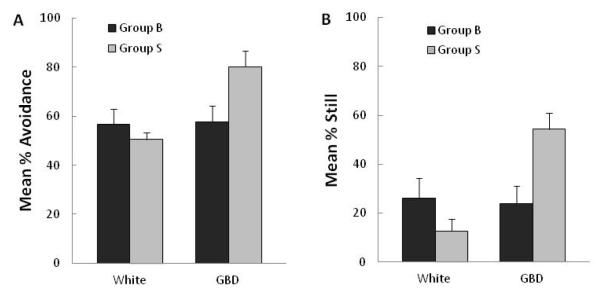

3.2 Experiment 1: Basic demonstration of single stimulus learning

The results from the test phase in Experiment 1 are shown in Figure 2A for percent avoidance and Figure 2B for percent still. Table II shows the means for percent edge and swim rate. During the 5 min presentation of the gray bouncing disk, larvae previously exposed to that stimulus (Group B) showed less avoidance, F(1,43) = 5.8, p<.025, were less likely to be still, F(1,43) = 9.3, p<.01, and had faster swim rates, F(1,43) = 8.3, p<.01, than the larvae exposed to the stationary gray disk (Group S). The two groups did not, however, differ in the mean percent observations on the edge (F<1). There were no significant differences between the two groups on any of these measures in the 5 min white presentation that immediately preceded testing with the gray bouncing disk, Fs(1,43) ≤ 2.0, ps>.10.

Figure 2. Experiment 1.

Mean responses in testing (t2) to the gray bouncing disk for 7 dpf larvae that had been exposed in training (t1) either to that gray bouncing disk (Group B, black bars) or to an identical but stationary disk (Group S, gray bars). Data are shown separately for the 5-min period with no visual stimulus (White) and the 5-min period with the gray bouncing disk (GBD). A) Mean % avoidance denotes the percent observations that the larva was on the side away from where the stimulus was presented; B) Mean % still denotes percent displacements of larval centroids between two consecutive images that were smaller than 0.3 mm.

TABLE II.

Means (±SEMs) during testing on white background (WHITE) and in presence of bouncing disk (GBD)

Groups: B = bouncing disk, S = stationary disk

| %Edge | %Edge | Swim rate (mm/min) | Swim rate (mm/min) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| White | GBD | White | GBD | |

|

| ||||

| Exp 1 | ||||

| Group B | 84.5 (±3.6) | 88.6 (±2.5) | 83.2 (±11.7) | 70.3 (±9.5) |

| Group S | 88.0 (±4.1) | 91.8 (±4.5) | 83.6 (±9.7) | 36.8 (±6.6) |

|

| ||||

| Exp 2 | ||||

| 5 dpf | ||||

| Group B | 70.3 (±7.0) | 80.7 (±6.2) | 33.1 (±7.0) | 22.7 (±5.2) |

| Group S | 68.3 (±7.5) | 94.5 (±4.1) | 49.2 (±10.2) | 12.6 (±3.0) |

|

| ||||

| 6 dpf | ||||

| Group B | 79.9 (±5.4) | 79.0 (±6.5) | 61.6 (±9.0) | 57.0 (±9.7) |

| Group S | 77.6 (±4.1) | 91.4 (±4.2) | 53.6 (±8.8) | 15.5 (±6.1) |

|

| ||||

| 7 dpf | ||||

| Group B | 73.4 (±5.9) | 80.0 (±5.8) | 55.4 (±10.9) | 58.6 (±11.5) |

| Group S | 70.1 (±5.1) | 80.6 (±5.2) | 58.8 (±10.2) | 20.7 (±4.7) |

|

| ||||

| Exp 3 | ||||

| Group B-8 | 79.5 (±4.1) | 83.4 (±3.6) | 73.1 (±10.6) | 74.5 (±11.2) |

| Group S-8 | 66.6 (±5.8) | 89.4 (±5.6) | 82.6 (±11.5) | 14.6 (±8.2) |

|

| ||||

| Group B-4 | 81.0 (±5.3) | 88.6 (±4.1) | 88.1 (±11.6) | 69.7 (±11.7) |

| Group S-4 | 78.1 (±6.3) | 88.9 (±5.7) | 77.5 (±11.1) | 20.7 (±5.0) |

|

| ||||

| Group B-1 | 87.4 (±3.4) | 92.2 (±3.1) | 95.6 (±6.7) | 87.3 (±7.8) |

| Group S-1 | 79.9 (±3.2) | 90.4 (±2.5) | 99.5 (±6.4) | 71.3 (±9.1) |

|

| ||||

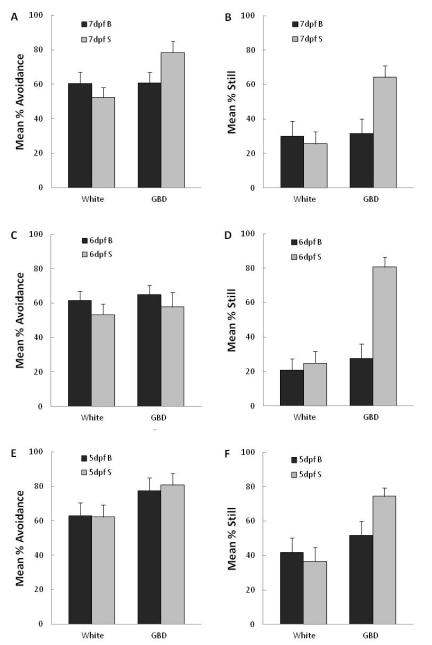

3.3 Experiment 2: Effect of larval age

Data from the test phase in Experiment 2 are shown in Figure 3 for percent avoidance and percent still and in Table II for percent edge and swim rate. For larvae exposed and tested at 7 dpf, the overall pattern of results replicated that of Experiment 1. Group B was less likely to be still, F(1,45) = 9.0, p<.01, and had significantly faster swim rates, F(1,45) = 8.9, p<.01, than Group S. They also displayed numerically less avoidance although this difference was not significant, F(1,45) = 3.6, p>.06. As in Experiment 1, there was no significant difference in the mean percent observations on the edge (F<1) and there were no significant differences in the 5 min white period preceding testing (Fs<1).

Figure 3. Experiment 2: Effects of larval age.

Mean responses in testing (t2) to the gray bouncing disk for larvae that had been exposed in training (t1) either to that gray bouncing disk (Group B, black bars) or to an identical but stationary disk (Group S, gray bars). Data are shown separately for the 5-min period with no visual stimulus (White) and the 5-min period with the gray bouncing disk (GBD). A, C, E) Mean % avoidance denotes the percent observations that the larva was on the side away from where the stimulus was presented for 7, 6, and 5 dpf larvae, respectively; B, D, F) Mean % still denotes percent displacements of larval centroids between two consecutive images that were smaller than 0.3 mm for 7, 6, and 5 dpf larvae, respectively.

The novel data in this experiment come from the tests with the 5 and 6 dpf larvae. Larvae previously exposed to the gray bouncing disk were less likely to remain still during its presentation in testing at both 5 dpf, F(1,46) = 5.8, p<.025, and 6 dpf, F(1,46) = 26.7, p<.01. In addition, these larvae had faster swim rates than their respective controls but the difference was only significant at 6dpf, F(1,46) = 13.1, p<.01, and not at 5 dpf, F(1,46) = 2.8, p>.10. At neither age was there a significant difference in percent avoidance (Fs<1) or in percent edge, F(1,46) = 3.4, p>.07 at 5dpf and F(1,46) = 2.56, p>.10 at 6 dpf. There were no significant differences between Groups B and S on any of the response measures in the 5 min white presentation that immediately preceded testing with the gray bouncing disk at either 5 dpf, Fs(1,46) ≤ 1.7, ps>.10, or at 6 dpf (Fs<1).

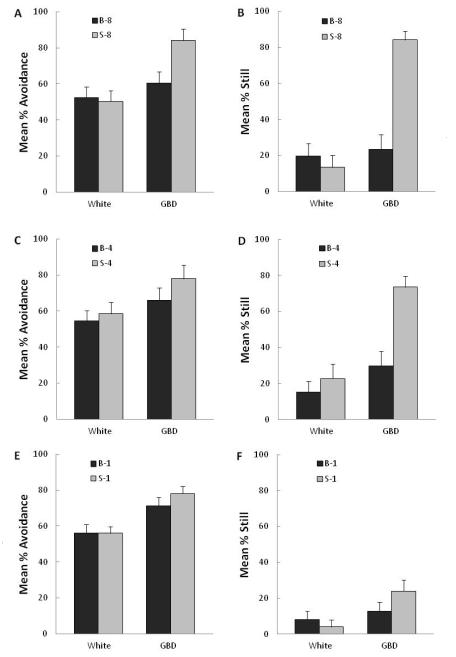

3.4 Experiment 3: Effect of number of stimulus exposures

Figure 4 shows the test results for percent avoidance and percent still for Groups B and S after receiving 8, 4 or 1 stimulus exposures. Test data for percent edge and swim rate are shown in Table II. Larvae that received 8 exposures to the gray bouncing disk (Group B-8) showed less avoidance, F(1,46) = 6.92, p = .01, were less likely to be still, F(1,46) = 40.18, p <.01, and were more active as measured by swim rate, F(1,46) = 18.79, p < .01, when presented with the gray bouncing disk in the test than the larvae that had been exposed to the gray stationary disk (Group S-8). These two groups did not, however, differ in the percent observations on the edge (F<1). Larvae that received 4 exposures to the gray bouncing disk (Group B-4) were less likely to be still, F(1,45) = 16.9, p<.01, and had faster swim rates, F(1,45) = 13.7, p<.01, when presented with the gray bouncing disk in the test than the larvae that had been exposed to the gray stationary disk (Group S-4). The two groups did not, however, differ in the percent avoidance, F(1,46) = 1.1, p>.10, or in percent observations on the edge (F<1). Larvae that received just one 5-min exposure to the gray bouncing disk (Group B-1) did not differ from larvae exposed to the stationary disk (Group S-1) on any of the measures during the test with the bouncing disk, Fs(1,46) ≤ 1.89, ps>.10.

Figure 4. Experiment 3: Effects of stimulus exposure.

Mean responses in testing (t2) to the gray bouncing disk for larvae that had been exposed in training (t1) either to that gray bouncing disk (Group B, black bars) or to an identical but stationary disk (Group S, gray bars). Data are shown separately for the 5-min period with no visual stimulus (White) and the 5-min period with the gray bouncing disk (GBD). A, C, E) Mean % avoidance denotes the percent observations that the larva was on the side away from where the stimulus was presented following 8, 4, or 1 stimulus presentations, respectively; B, D, F) Mean % still denotes percent displacements of larval centroids between two consecutive images that were smaller than 0.3 mm following 8, 4, or 1 stimulus presentations, respectively.

In the 5-min period of white that immediately preceded testing with the gray bouncing disk, regardless of the number of stimulus exposures, there were no significant differences between larvae exposed to the gray bouncing disk and those exposed to the gray stationary disk on measures of percent avoidance (Fs<1), swim rate (Fs<1) or percent still (Fs<1). Similarly, there was no significant difference in percent edge following one, F(1,46)=2.5, p>.10 or four (F<1) or eight stimulus exposures, F(1,46)= 3.3, p>.05.

4. Discussion

In three experiments, zebrafish larvae were exposed to repeated 5-min presentations of either a gray bouncing disk (Group B) or a gray stationary disk (Group S) on a white background alternating with 5-min periods of the white background alone. All larvae were then tested with a 5-min presentation of the gray bouncing disk preceded by a 5-min white background. Automated images were collected at 6 sec intervals and subsequently analyzed for information about larval location, swim rate and immobility during testing. The finding of most interest was that the two exposure treatments produced differential responding during a common test with the gray bouncing disk. Of the four measures recorded, the most sensitive index of this effect was percent still: Group B had significantly fewer displacements of less than .3 mm between consecutive images than Group S. This effect was found in 5, 6, and 7 dpf larvae given 12 stimulus exposures (Experiments 1 and 2) and in 7 dpf larvae given 4 and 8 stimulus exposures (Experiment 3). None of these group differences was statistically significant in the 5 min period on the white background that immediately preceded the test presentation of the gray bouncing disk.

Exposure to a novel stimulus is an operation that not only makes an individual aware of the existence of the stimulus but provides an opportunity for an individual to construct an internal representation of that stimulus (Rescorla & Holland, 1976). Such learning is fundamental to the ability to recognize stimuli and is the foundation for learning about relations between stimuli in Pavlovian conditioning and among stimuli, responses and outcomes in instrumental conditioning. Although our experiments were not designed to evaluate stimulus specificity and the precision of the internal representations of the exposure stimuli, our results clearly demonstrate that the two groups were differentially affected by their respective experiences at t1. We consider two possible explanations, habituation and expectancy violation, for why Groups B and S behaved differently in the presence of the bouncing disk in the common test at t2.

When confronted with a potential threat, individual larval zebrafish may freeze to avoid detection or swim away to avoid capture or injury. In nature, however, large moving stimuli do not necessarily signal imminent danger for zebrafish larvae. For example, plants or leaf debris may be moved by water currents and, depending on weather conditions, overhanging foliage may cast fluctuating shadows. Habituation is an elementary and ubiquitous form of learning that enables animals to ignore irrelevant stimuli of this kind. Our data are consistent with the view that young zebrafish larvae have the ability to learn about inconsequential stimuli and to modify their responses to them. Specifically, 5, 6, and 7 dpf larvae were significantly less likely to remain motionless during testing with the bouncing disk if they had been repeatedly exposed to that stimulus (Group B) than if they had received repeated exposure to an identical but stationary stimulus (Group S). In a related study with 6-8 dpf zebrafish larvae, a reduction in the C-start reflex to an auditory/vibrational test stimulus was observed in larvae familiar with presentations of that stimulus compared to larvae that had no prior experience with that stimulus (Roberts, Reichl, Song, Dearinger, Moridzadeh, Lu et al., 2011). Such differences in behavior to a stimulus at t2 following variations in experience with that stimulus at t1 are commonly interpreted as evidence of habituation.

An alternative explanation for the difference between Groups B and S in testing invokes the concept of expectancy violation. According to this account, larvae exposed to the stationary stimulus (Group S) developed the expectancy that this stimulus was a static feature of their environment, revealed at regular intervals in the same physical location. This expectancy was violated when the disk moved during testing, resulting in a strong startle reaction detected here as heightened immobility or freezing. These two accounts, habituation in Group B and expectancy violation in Group S, are not mutually exclusive. One strategy to evaluate their relative contributions would be to compare the test responses of Groups B and S to those of larvae that received no stimulus presentations in the exposure phase. Interpretation of such comparisons would, however, be complicated by any significant behavioral differences among the groups in the 5-min period on the white background preceding the test presentation of the bouncing disk.

Studies adopting the t1-t2 framework to investigate the plasticity of stimulus-elicited defensive behaviors are immune to several significant problems that can plague the traditional design of measuring habituation in terms of a decrement in responding between the initial and terminal presentations of a repeated stimulus. Given the relative popularity of the traditional approach among zebrafish researchers (Best et al., 2008; Burgess & Granato, 2007; Grossman, Stewart, Gaikwad, Utterback, Wu, Dileo et al., 2011; Levin, Swain, Donerly, & Linney, 2004; Miklosi & Andrew, 1999; Sledge, Yen, Morton, Dishaw, Petro, Donerly et al., 2011; Wong, Elegante, Bartels, Elkhayat, Tien, Roy et al., 2010), we reiterate these concerns as they apply to the study of learning in developing zebrafish. In a typical study, zebrafish larvae are exposed to a series of brief stimulus presentations that elicit a startle reflex. Their learning is indexed by a significant decrease in the response to that stimulus between its initial and terminal presentations. This approach to the study of learning is problematic (Davis, 1970; Davis & Wagner, 1968, 1969; Rescorla, 1988; Rescorla & Holland, 1976).

One notable problem is that a change in behavior may arise for reasons that are quite independent of the repeated stimulus exposure. For example, maturational changes may occur between the first and last stimulus presentations which may affect stimulus processing or response production. Similarly, behavior may be affected by acute motivational changes induced by gradual shifts in ambient conditions such as water temperature or quality, by prolonged isolation from conspecifics, or by increasing hunger or fatigue. For these reasons, it is not meaningful in our experiments to compare the behavior of Group B to the first and last presentations of the bouncing disk or to compare the behavior of Group B to the first presentation of the bouncing disk with the behavior of Group S to their first exposure to the bouncing disk. Such problems are essentially eliminated when larvae that differ only in their prior experience with the stimulus at t1 are compared in a common test at t2.

Alternatively, the learning-performance confound can arise from the stimulus presentations themselves. Studies of the effects of stimulus intensity measuring learning as a change in behavior at t1 have produced the same kind of questionable conclusions about the nature of habituation as have studies of the effects of stimulus distribution. Relatedly, it is not uncommon to find researchers claiming that after a response decrement plateaus, additional stimulus presentations produce no further learning. Similarly, claims have been made that habituation may be weak or nonexistent when repeated stimulus presentations lead to little or no decrement in responding. In these latter examples, the conclusions represent a failure to appreciate that learning may be behaviorally silent. Mistakes of this kind can be avoided with the adoption of the t1-t2 framework because animals given different experiences at t1 can be compared in a common test at t2 that is not inherently or artificially restricted to a measurement that can be employed at t1. Given these arguments, we restricted our analyses to the t2 data to demonstrate single stimulus learning in zebrafish larvae.

Implementation of the t1-t2 framework is not, however, always possible. Neuroscience techniques, developmental studies and experimental manipulations applied to the study of learning routinely confound t1 and t2. Consider, for example, Experiment 3 in which the number of stimulus exposures was manipulated. For each exposure condition, t2 immediately followed the end of t1. Although this held constant the interval between the end of training and the start of testing for all larvae, the interval between the start of training and the start of testing varied with the number of exposures, from 10 min with one exposure to 80 min with 8 exposures. Consequently, at the time of testing, larvae differed in the total number of stimulus exposures, total time in the wells, time from the first stimulus exposure and in their exact age. As a result, it is unclear whether the apparent increase in the magnitude of the differences between Groups B and S as a function of number of exposures is a product of learning, as would be predicted by most learning theories, or of performance.

Experiment 2, in which both t1 and t2 were administered at different ages, illustrates a similar challenge for developmental studies of learning. The difference in percent still between Groups B and S was statistically significant at 5, 6, and 7 dpf, revealing that larvae at all three ages have the capacity to learn. The magnitude of those group differences, however, was not consistent across those ages and appeared largest at 6 dpf. Again, it is unclear whether this age-related effect should be attributed to differences in learning or to factors that affect the expression of that learning. In this particular case, a performance based explanation seems reasonable given the ongoing maturation of the sensory and motor systems. Locomotor responses emerge in a predictable sequence in the developing zebrafish from gross, rapid swim movements to slow, controlled ones (Fetcho & McLean, 2010; McLean & Fetcho, 2009), culminating in a functional beat and glide system by 5 dpf. The visual system also develops after hatching with distinct differences apparent in the age range we examined. Visual acuity, for example, improves with age and continues to do so in larvae much older than 7 dpf (Bilotta, 2000). The optomotor response (OMR) is considered robust in 7 dpf larvae but unreliable or not present at all in 5 dpf and younger larvae (Fleisch & Neuhauss, 2006). It is possible that the challenge of co-ordinating a dual speed motor system with a maturing visual system and the need to compensate for morphological growth may underlie the pattern of age-related differences in Experiment 2.

The t1-t2 framework specifies an elegant strategy for studies of elementary learning processes but, as these examples show, some of the techniques used to investigate properties of that learning may have no option but to confound t1 and t2. In such situations, researchers need to be especially cautious in interpreting their results and consider the complications arising from confounding learning and performance. The importance of well-formulated psychological and neurobiological theories of learning to guide this process cannot be exaggerated. A major contribution of contemporary theories of habituation is the distinction between short-term and long-term habituation. Wagner’s (1976, 1981) dual-priming dual-memory model attributes the former to a non-learning process involving self-generated priming and the latter to an associative learning process involving retrieval-generated priming. The basic premise of this model is that responding to and learning about a stimulus will be attenuated if that stimulus is presented while its trace or representation is in an active state. Trace activation can occur through a recent presentation of the stimulus (self-generated priming) or through presentation of a cue associated with that stimulus (retrieval-generated priming). According to this approach, long-term habituation is mediated by an association between the stimulus and typically the context in which that stimulus is presented. An important prediction of this model, corroborated by behavioral studies of the effects of stimulus intensity and distribution, is that long-term habituation is inversely related to short-term habituation.

A distinction between short-term and long-term habituation has also emerged in neurobiological research which has been heavily influenced by the dual process theory (Groves & Thompson, 1970). Studies of stimulus-response reflex arcs in simple systems such as Aplysia have shown that a decrease in neurotransmitter release at the terminals of sensory neurons contributes to short-term habituation whereas post-synaptic processes and protein synthesis contribute to long-term habituation (Glanzman, 2009). The zebrafish is an ideal model system to examine the involvement of these molecular and neurobiological mechanisms in learning at different stages of development. For example, long-term habituation can be suppressed by inhibition of protein synthesis with cyclohexamide (Wolman et al., 2011) and it may be possible to suppress specific proteins, such as the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), which are important for the conversion of short- to long-term memory (Kandel, 2012). Moreover, advanced imaging-based methodologies have been developed to modulate and measure neural activity and integrate neural anatomy and function for zebrafish circuit analysis (Arrenberg & Driever, 2013).

Aside from demonstrating single stimulus learning in 7 dpf zebrafish larvae, a major contribution of our studies is the establishment of an assay that produces robust learning in larvae as young as 5 dpf (Experiment 2) and with as few as 4 stimulus exposures in 7 dpf larvae (Experiment 3). These features are highly desirable for rapid genetic screening of mutants that have limited survival potential. However, further refinements are needed to increase the suitability of our assay for high throughput forward genetic large scale screens or high throughput screening of pharmaceuticals and chemical compounds for behavioral effects. For example, one current limitation is the inability of the automated image analysis software to differentiate a superimposed or juxtaposed larva from our startle stimulus. Although manual extraction of the X,Y coordinates of the larva was possible under these conditions, this process was extremely labor intensive. Use of a red or blue bouncing disk solves the image segregation problem but there is a reduction in the effectiveness of these colored stimuli relative to the gray disk in eliciting robust startle behaviors. Additionally, it would be informative to improve the precision of our four behavioral measures. Analyzing a videotaped recording of the 10 min assessment test would improve the fidelity of these measures, allow continuous tracking of the reactions of the larvae to the moving test stimulus, and enable better assessment of the interactions among the measures due to larval maturation and response competition.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a reliable behavioral assay with fully automated stimulus presentations to demonstrate that the behavior of 5, 6 and 7 dpf zebrafish larvae can be modified by experience. Consistent across all three experiments, zebrafish larvae familiarized with a gray bouncing disk were less likely to be still in its presence during testing than were control larvae equally familiar with an identical but stationary disk. This difference meets the criteria established by the t1-t2 framework for learning. The goal of our future studies is to characterize in detail the nature of this learning from both psychological and neurobiological perspectives. A critical but challenging next step is to determine the persistence of the effect we have demonstrated.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS, R03ES017755) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD, R01HD060647). Thanks are due to Sean Pelkowski, Sarah Gonzalez, Matt Lattal and two anonymous reviewers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arrenberg AB, Driever W. Integrating anatomy and function for zebrafish circuit analysis. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2013;23:7–74. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00074. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best JD, Berghmans S, Hunt JJ, Clarke SC, Fleming A, Goldsmith P, Roach AG. Non-associative learning in larval zebrafish. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(5):1206–1215. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301489. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilotta J. Effects of abnormal lighting on the development of zebrafish visual behavior. Behavioral Brain Research. 2000;116(1):81–87. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00264-3. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(00)00264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess HA, Granato M. Sensorimotor gating in larval zebrafish. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27(18):4984–4994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0615-07.2007. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0615-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Huang C, Zheng L, Simonich M, Bai C, Tanguay R, Dong Q. Trimethyltin chloride (TMT) neurobehavioral toxicity in embryonic zebrafish. Neurotoxicology & Teratology. 2011;33(6):721–726. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.09.003. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill RM, Creton R. Imaging escape and avoidance behavior in zebrafish larvae. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2011a;22(1):63–73. doi: 10.1515/RNS.2011.008. doi:10.1515/RNS.2011.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwill RM, Creton R. Locomotor behaviors in zebrafish (danio rerio) larvae. Behavioural Processes. 2011b;86(2):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creton R. Automated analysis of behavior in zebrafish larvae. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;203(1):127–136. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.030. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. Effects of interstimulus interval length and variability on startle-response habituation in the rat. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1970;72(2):177–192. doi: 10.1037/h0029472. doi:10.1037h0029472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Wagner AR. Startle responsiveness after habituation to different intensities of tone. Psychonomic Science. 1968;12(7):337–338. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Wagner AR. Habituation of startle response under incremental sequence of stimulus intensities. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1969;67(4):486–492. doi: 10.1037/h0027308. doi:10.1037h0027308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetcho JR, McLean DL. Some principles of organization of spinal neurons underlying locomotion in zebrafish and their implications. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1198:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05539.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisch VC, Neuhauss SCF. Visual behavior in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2006;3(2):191–201. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2006.3.191. doi:10.1089/zeb.2006.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanzman DL. Habituation in Aplysia: The Cheshire Cat of neurobiology. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2009;92:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.005. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman L, Stewart A, Gaikwad S, Utterback E, Wu N, Dileo J, et al. Effects of piracetam on behavior and memory in adult zebrafish. Brain Research Bulletin. 2011;85(1-2):58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.02.008. doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves PM, Thompson RF. Habituation: a dual-process theory. Psychological Review. 1970;77:419–450. doi: 10.1037/h0029810. doi: 10.1037/h0029810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine D, Litvak MK. Direct yolk sac volume manipulation of zebrafish embryos and the relationship between offspring size and yolk sac volume. Journal of Fish Biology. 2003;63(2):388–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1095-8649.2003.00161. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER. The molecular biology of memory: cAMP, PKA, CRE, CREB-1, CREB-2, and CPEB. Molecular Brain. 2012;14:5–14. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-14. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokel D, Peterson RT. Using the zebrafish photomotor response for psychotropic drug screening. Methods in Cell Biology. 2011;105:517–524. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00022-9. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381320-6.00022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Swain HA, Donerly S, Linney E. Developmental chlorpyrifos effects on hatchling zebrafish swimming behavior. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2004;26(6):719–723. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2004.06.013. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean DL, Fetcho JR. Spinal interneurons differentiate sequentially from those driving the fastest swimming movements in larval zebrafish to those driving the slowest ones. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(43):13566–13577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3277-09.2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3277-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklosi A, Andrew RJ. Right eye use associated with decision to bite in zebrafish. Behavioural Brain Research. 1999;105(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(99)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkowski SD, Kapoor M, Richendrfer HA, Wang X, Colwill RM, Creton R. A novel high-throughput imaging system for automated analyses of avoidance behavior in zebrafish larvae. Behavioural Brain Research. 2011;223(1):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.033. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers CM, Wrench N, Ryde IT, Smith AM, Seidler FJ, Slotkin TA. Silver impairs neurodevelopment: Studies in PC12 cells. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2010;118(1):73–79. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901149. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Behavioral studies of Pavlovian conditioning. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 1988;11(1):329–352. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.001553. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.001553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Holland PC. Some behavioral approaches to the study of learning. In: Bennett E, Rosenzweig MR, editors. Neural mechanisms of learning and memory. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1976. pp. 165–192. [Google Scholar]

- Richendrfer H, Pelkowski SD, Colwill RM, Creton R. On the edge: Pharmacological evidence for anxiety-related behavior in zebrafish larvae. Behavioural Brain Research. 2012;228(1):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.11.041. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2011.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, Reichl J, Song MY, Dearinger AD, Moridzadeh N, Lu ED, et al. Habituation of the C-start response in larval zebrafish exhibits several distinct phases and sensitivity to NMDA receptor blockade. PloS One. 2011;6(12):e29132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029132. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selderslaghs IWT, Hooyberghs J, De Coen W, Witters HE. Locomotor activity in zebrafish embryos: A new method to assess developmental neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2010;32(4):460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2010.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledge D, Yen J, Morton T, Dishaw L, Petro A, Donerly S, et al. Critical duration of exposure for developmental chlorpyrifos-induced neurobehavioral toxicity. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2011;33(6):742–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.06.005. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AR. Priming in STM: An information-processing mechanism for self-generated or retrieval-generated depression in performance. In: Tighe TJ, Leaton RN, editors. Habituation: Perspectives from child development, animal behavior, and neurophysiology. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1976. pp. 95–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AR. SOP: A model of automatic memory processing in animal behavior. In: Spear NE, Miller RR, editors. Information processing in animals: Memory mechanisms. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1981. pp. 5–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wolman MA, Jain RA, Liss L, Granato M. Chemical modulation of memory formation in larval zebrafish. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(37):15468–15473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107156108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1107156108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolman M, Granato M. Behavioral genetics in larval zebrafish: Learning from the young. Developmental Neurobiology. 2012;72(3):366–372. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20872. doi:10.1002/dneu.20872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong K, Elegante M, Bartels B, Elkhayat S, Tien D, Roy S, et al. Analyzing habituation responses to novelty in zebrafish (danio rerio) Behavioural Brain Research. 2010;208(2):450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.023. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]