Abstract

In spite of significant advances in early detection and combined treatments, a number of cancers are often diagnosed at advanced stages and thereby carry a poor prognosis. Developing novel prognostic biomarkers and targeted therapies may offer alternatives for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Recent rapid development of nanomaterials, such as silica based nanoparticles (SiNPs), can just render such a promise. In this article, we attempt to summarize the recent progress of SiNPs in tumor research as a novel delivery vector. SiNP-assisted imaging techniques are used in cancer diagnosis both in vitro and in vivo. Meanwhile, SiNP-mediated drug delivery can efficiently treat tumor by carrying chemotherapeutic agents, photosensitizers, photothermal agents, siRNA, and gene therapeutic agents. Finally, SiNPs that contain at least two different functional agents may be more powerful for both tumor imaging and therapy.

Keywords: silica nanoparticles, tumor diagnosis, tumor therapy, multifunctional

1. Introduction

In the last two decades, applications of nanotechnology in cancer diagnosis and therapy have attracted significant attention.1–4 A number of functional nanomaterials have been developed and evaluated for drug delivery,5, 6 diagnostic sensors,7 imaging agents,8 and labeling probes.9 Nanomaterials can be organic or inorganic,10, 11 with a size from 1 nanometer to a few hundred nanometers,12, 13 and surface charges from negative to positive or natural.14 Gold nanoparticles,15 quantum dots,16 carbon nanotubes,17 magnetic nanoparticles,18 liposomes,19 and silica nanoparticles (SiNPs)20 have been developed for imaging as well as drug and gene delivery. Furthermore, multifunctional nanomaterials with two or more different functions have been designed for cancer imaging and therapy both in vitro and in vivo. 21–23

Among these nanomaterials, SiNPs have gained special attention for tumor imaging and therapy due to their easy synthesis, uniform morphology, adjustable pore volume, controllable diameter, modifiable surface potential, easy functionalization, and significant biocompatibility.24–27 There are two main types of SiNPs developed for tumor imaging and therapy: mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs)27 and core/shell silica nanoparticle (C/S-SiNPs).26 MSNs were successfully used for drug delivery and gene delivery because of their unique mesopores and nanochannels, which can render a high payload of the drug28 and easy stimuli-controllable release.29 C/S-SiNPs are useful for imaging agent delivery because imaging agents, such as fluorophores, quantum dots (QDs), and gold nanoparticles, can be easily doped into the nanoparticles. The shell structures can protect imaging agents inside the nanoparticles, and the signal from imaging agents gives the precise location of nanoparticles and tumor tissue.30 SiNPs can accumulate in tumor tissues through passive targeting and active targeting.31, 32 More importantly, both MSNs and C/S-SiNPs have shown a significant biocompatibility both in vitro and in vivo,33, 34 a great property for tumor diagnosis and therapy in humans.

In this article, we will briefly discuss the synthetic methods and important characteristics of relatively well-studied SiNPs. Due to the importance of early cancer diagnosis, the applications of SiNPs in in vitro and in vivo imaging will be discussed as well. By varying imaging agents in SiNPs, the end products can be used in different imaging models, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorescence imaging, positron emission tomography (PET), and X-ray computed tomography (X-ray CT) imaging. Then, the applications of SiNPs in drug and gene delivery for tumor therapy will be summarized. Photosensitizers, photothermal agents and chemotherapeutic agents can be successfully delivered to tumor cells and tissues by SiNPs. The loading and releasing mechanisms of drugs in MSNs and the applications of multifunctional nanomaterials bearing imaging and therapeutic features will be discussed. The different types of SiNPs for tumor imaging and therapy in vitro and in vivo coupled with their characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The SiNPs for tumor imaging and therapy in vitro and in vivo.

| Type | Diameter (nm) |

Surface modification |

targets | Targeting pathway |

Imaging mode | Therapeutic mode |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core/shell SiNPs | 20 | monoclonal antibodies | cells | Active | Fluorescence (rhodamine-B) | 59 | |

| 30 | Folic acid | cells | Active | Fluorescence (DBF*) | 61 | ||

| Aptamer | cells | Active | Fluorescence (FITC†, RuBpy‡, TMR§ and Cy5) | 64 | |||

| 31 | RGD‖ | cells | Active | Fluorescence (QDs¶) and MRI (Gd) | 78 | ||

| 25 | -NH2 | cells | Cell uptake | Fluorescence (rhodamine 6G) | Antisense oligonucleotides | 99 | |

| 105 ± 6.8 | -PO43− | Xenografts | Fluorescence (MB#) | PDT** (MB) | 67 | ||

| 25 – 42 | -NH2 and PEG†† | Xenografts | Passive | Fluorescence (IR820) | PDT (PpIX‡‡) | 74 | |

| 120 | Xenografts | Cell uptake | Fluorescence (QDs) | 75 | |||

| Folic acid | Cells and xenografts | Active | Dark-field scattering and CT/X-ray imaging (AuNR) | PTT§§ (AuNR‖ ‖) | 103 | ||

| MSNs | 150 | Cells | Cell uptake | Chemo (DOX¶¶) and PTT (Pd@Ag) | 3 | ||

| 50 | TAT peptide | Cells | Active | Fluorescence (DOX) | Chemo (DOX) | 39 | |

| 110–130 | Polyethyleneimine | Cells | Cell uptake | Fluorescence (FITC) | siRNA and DNA | 13 | |

| ~220 | Cells | Cell uptake | Fluorescence (FITC) | Chemo (DOX) | 28 | ||

| ~110 | RGD | Cells | Active | Fluorescence (FITC) | Chemo (CPT##) | 46 | |

| 245 | Galactose | Cells | Active | Fluorescence (FITC) | Chemo (CPT) and PDT (porphyrin) | 96 | |

| 200 | Cells | Cell uptake | Fluorescence (DOX) | siRNA and Chemo (DOX) | 101 | ||

| 100 – 130 | Folic acid | Xenografts | Active | Fluorescence (FITC) | Chemo (CPT) | 65 | |

| < 100 | PEG | Xenografts | Passive | MRI (Fe3O4) | 79 | ||

| 70 ± 6 | PEG | Xenografts | Passive | MRI (Fe3O4) | Chemo (DOX) | 81 | |

| 100–130 | folic acid | Xenografts | Active | Chemo (CPT) | 32 | ||

| Silica Nanorattle | 125 | PEG | Xenografts | Passive | Chemo (Dtxl***) | 43 |

Footnotes:

4,4'-(1E,1'E)-2,2'-(9,9-didecyl-9H-fluorene-2,7-diyl)bis(ethene-2,1- diyl)bis(N,N-dibutylaniline); Fluorescein isothiocyanate;

Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) chloride;

tetramethylrhodamine;

Arg-Gly-Asp;

quantum dots;

methylene blue;

photodynamic therapy;

polyethylene glycol;

protoporphyrin IX;

photothermal therapy;

gold nanorod;

doxorubicin;

camptothecin;

docetaxel.

2. Characteristics of silica nanoparticles

2.1 Particle size

As a delivery vector, the particle size and pore dimension of SiNPs are crucial parameters and affected drug loading efficiency, pathway of cell uptake, biodistribution in vivo and targeting efficiency in cancer diagnosis and therapy.35, 36 Through a reverse microemulsion method, monodispersed C/S-SiNPs can be easily constructed with a controllable size. For instance, Tan et al. investigated how the amount of ammonium hydroxide, surfactant, tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS), H2O, and reaction time affect the size of SiNPs.37 They found that the size of the dye-doped SiNPs was reverse-proportional to the concentration of ammonium hydroxide and water to surfactant molar ratio, but direct-proportional to the amount of TEOS and reaction time.37 In order to continuously control the size of the C/S-SiNPs in a more defined range, Zhao et al. developed a method by systematically varying the organic solvents used in a reverse microemulsion method.38 Organic solvent may affect the surface area occupied by surfactant molecules, while the diameter of water droplet can increase with the length of the organic molecule. Eventually, through hydrolysis of TEOS on the surface of the droplet, the size of nanoparticles may change by varying the organic molecule. C/S-SiNPs with a tunable size range from 10–100 nm was developed by simply varying the types of organic solvents.

Varying the amount of ammonium hydroxide was also useful for synthesizing MSNs with different sizes. Mou et al. synthesized MSNs with sizes from 30 nm to 280 nm using this strategy.35 It was also found that the uptake of MSNs by cells was size-dependent and 50 nm was the preferable diameter for cell uptake. Pan et al. developed a tunable particle size of MSNs from 25 nm to 105 nm, and size effect on nuclear targeting was investigated.39 They found that only MSNs of 50 nm or smaller can effectively target nucleus with the help of a TAT peptide. Using the Stö ber method, large nanoparticles from 60 nm to 880 nm were synthesized by the Rosenzweig group by changing the amount of ammonium hydroxide.40 The toxicity of SiNPs was also associated with their diameters. Hoet et al. developed a method to obtain amorphous spherical SiNPs of different sizes ranged from 13.8 nm to 335.0 nm and investigated their cytotoxicity to human endothelial cells. It was found that the smaller the particles, the higher the toxicity to cells.41

2.2 Surface modification

The surface of SiNPs is usually negatively charged without further modification because of the presence of the hydroxyl group after hydrolysis of TEOS. However, it is convenient to modify the SiNPs’ surface through the silane chemistry. Polyethylene glycol (PEG), amine, carboxyl, and phosphate groups could be easily conjugated to hydroxyl SiNPs by hydrolysis of the corresponding silanes. For example, He et al. synthesized three types of SiNPs with different surface charges, including OH-SiNPs, COOH-SiNPs, and PEG-SiNPs, and found that the biodistribution and excretion of the SiNPs were dependent on surface modifications. Neutrally-charged SiNPs (PEG-SiNPs) exhibited relatively longer blood circulation and lower uptake by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) organs than the other two.33 As a result, these PEG-modified SiNPs showed better passive targeting effects to the tumor site when they were used for the delivery of drugs and imaging agents.42, 43

Furthermore, as an effective delivery vector, active targeting is another strategy for better targeting efficiency. After surface modification with different functional groups, targeting molecules, including antibodies,44 peptides,45, 46 folic acid,47 and aptamers,48 can be easily conjugated to the surface of SiNPs for active targeting tumor tissues.49 For example, Lu et al. modified SiNPs with folic acids through EDC-NHS conjugation.32 Tan et al. reported modification of COOH-SiNPs with aptamers through EDC-NHS conjugation reaction and used the aptamer-modified dye-doped SiNPs for the detection of cancer cells.31 By using these strategies, the surface of SiNPs is easily modified with recognizing molecules to enhance the ability of the SiNPs to recognize cancer markers. Thus, the efficiency of SiNPs for cancer imaging and therapy is improved.

3. Imaging applications of silica nanoparticles

With tunable particle sizes, easy surface modification, and good biocompatibility, SiNPs have been widely used for imaging of cancer cells or tissues both in vitro and in vivo. Imaging agents can be doped into or modified on the surface of SiNPs. In the next section, we will review the latest progress in SiNPs-mediated tumor imaging with fluorescence and MRI techniques.

3.1 Fluorescence imaging

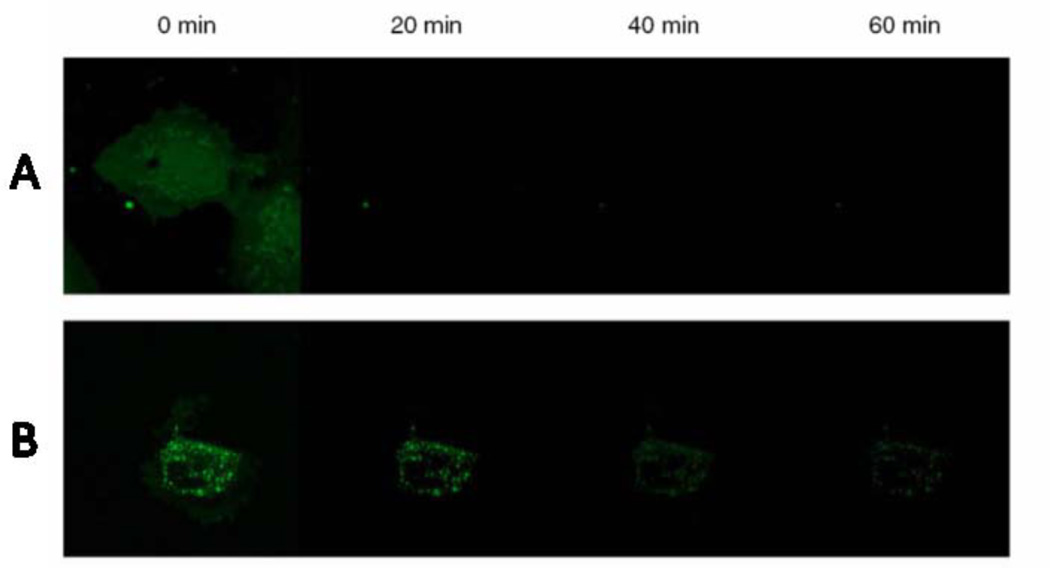

Fluorescence technology possesses high resolution compared to other imaging strategies, and the sensitivity of the fluorescence detection on cancer cells is promising.50, 51 Traditionally, fluorescent dyes suffer from the disadvantages of low brightness, photo-bleaching, and non-specific targeting.52 However, fluorescent SiNPs may overcome these shortcomings and provide highly sensitive and selective tumor imaging. By doping thousands of fluorescent dye molecules into one SiNP, the brightness of SiNP was much higher than a single dye molecule.53 For example, Herr et al. compared the fluorescence intensity between dye and dye-doped SiNPs.31 Their results showed that an aptamer modified dye-doped SiNP was brighter and more stable in fluorescence imaging than a dye-aptamer alone. Flow cytometry demonstrated that the signal from the SiNPs-aptamer was 100 times higher than that of the dye-aptamer. Therefore, these dye-doped SiNPs with high fluorescence intensity may be useful for creating highly sensitive biosensors.53 Another important advantage of dye-doped SiNPs compared to free dye molecules is that silica matrix can protect the dye from photobleaching, allowing long-duration imaging of tumor cells and tissues.54 As shown in Figure 1, with continual irradiation under a confocal microscope, the fluorescence of cells stained by pure FITC quenched almost completely within 20 min.55 However, 60% of fluorescence in the FITC-doped SiNPs retained for imaging after 20 min, and 30% of the fluorescence intensity retained even after 1 h irradiation. This indicates that fluorescent SiNPs may have better photostability than free dyes and thus were more powerful as fluorescent markers for long-time imaging of living cells and tissues.

Figure 1.

Confocal micrographs of continued irradiation of cells leading to photobleaching over a 1 h time scale. A) FITC loaded HUVEC cells. B) 30 nm fluorescent silica loaded cells. The cells are incubated with 100 µg/mL of nanomaterials for 3 h and are washed and subjected to continued irradiation for a period of 1 h. Images are taken every 20 min and the photobleaching of pure FITC and FITC loaded nanomaterials are studied. Reprinted from ref. 55 with permission by the SpringerLink.

Moreover, the facileness to modify SiNPs makes the modification of targeting ligands convenient and effective. Targeting ligands, such as aptamers,56, 57 antibodies,58, 59 peptides,60 and folic acid,61, 62 can be attached on SiNPs. Aptamer is a short fragment of DNA or RNA which can selectively bind to certain targets, including ions, small biomolecules, peptides, and cells.63 In 2011, Tan et al. developed an aptamer-conjugated nanoparticle for fluorescence imaging and extraction of tumor cells.64 In this assay, silica-coated magnetic and fluorophore-doped SiNPs modified with aptamers were used to recognize and isolate cancer cells from mixed cell populations using an external magnetic field.

The excellent optical characteristics of the dye-doped SiNPs ensure their usage as fluorescence agents for both tumor cells in vitro and in vivo imaging. Furthermore, the high biocompatibility and controllable size of SiNPs make in vivo tumor imaging possible.65, 66 The feasibility of SiNPs for in vivo imaging has been confirmed by many research groups. For instance, He et al. developed methylene blue-encapsulated phosphonate-terminated silica nanoparticles (MB-encapsulated PSiNPs) for in vivo imaging.30 They found that the MB-encapsulated PSiNPs could be used as an effective NIR fluorescence imaging agent in mice using three different injection routes.

For in vivo imaging, there are two different pathways to target tumors with nanoparticles. The first one is passive targeting by enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. In this case, certain sizes of particles would accumulate at the tumor sites rather than normal tissues because the newly formed blood vessels of tumor tissues were abnormal.67 The small nanoparticles, such as gold nanoparticles,68 gold nanoclusters,69 quantum dots,70 upconventional nanoparticles,71, 72 have been used to prove this theory for tumor targeting in vivo. The second pathway is active targeting by modifying target ligands on the surface of nanoparticles. In 2010, Lu et al. investigated the biodistribution of fluorescent SiNPs in mice with xenograft tumors.65 They found that both fluorescent silica nanoparticle (FMSNs) and folic acid modified fluorescent silica nanoparticles (F-FMSNs) could preferentially accumulate in tumor tissues after injecting to mice through the tail vein injection. The tissue section of different organs also confirmed the results from the in vivo fluorescence imaging. In these two different types of nanoparticles, FMSNs targeted tumor through EPR effect, while the F-FMSNs targeted tumor through the folate receptor on the surface of tumor cells. Meanwhile, Qian et al. reported PEG-modified NIR SiNPs for mouse tumor imaging due to its deep penetration ability and low autofluorescence in NIR region.66 The NIR SiNPs accumulated in the tumor tissues through EPR effects, also these NIR SiNPs exhibited bright and stable NIR fluorescence that could be used for long-term in vivo imaging. It was noteworthy that SiNPs could be cleared from the mice through the hepatobiliary excretion, indicating their relatively low toxicity and perhaps high applicability in humans.

In order to enhance the performance of fluorescence imaging, other fluorescent nanomaterials have been coupled to SiNPs for cancer imaging. For instance, quantum dots, which possess brighter fluorescence, narrower photoluminescence spectra and better photostability than traditional dyes, were embedded into SiNPs for tumor fluorescence imaging. In 2012, Jun et al. reported an ultrasensitive QDs-embedded SiNP for tumor fluorescence imaging (Figure 2a).73 Compared to a single QD, the QDs-embedded SiNPs showed brighter fluorescence intensity and increased uptake by HeLa cells (Figure 2b). For in vivo fluorescence cell tracking, single QD labeled- or QDs-embedded SiNPs labeled-HeLa cells were injected into mice for long-term fluorescence imaging, and the results showed that even after 10 days, the QDs-embedded SiNPs emitted strong fluorescence for in vivo imaging (Figure 2c). Therefore, the QDs-embedded SiNPs may have the potential for long-term fluorescence imaging in vivo.

Figure 2.

Cellular uptake in vivo test of single QDs and Si@QDs@Si NPs. a) Illustration of sQD or Si@QDs@Si-NP labeling to HeLa cells. b) Fluorescence images of sQD- and Si@QDs@ Si-NP-uptaken cells (Red color: QD, blue color: DAPI). c) Maestro in vivo fluorescence image of sQD-labeled (left leg) and Si@QDs@Si-NP-labeled (right leg) cell-transplanted mouse. Reprinted from ref. 73 with permission by Wiley-VCH.

3.2 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Compared to fluorescence imaging, MRI has better penetration ability in tissues. As a result, MRI is routinely used as a primary diagnosis method for cancer in hospitals. However, most of the currently-used MRI contrast agents are small molecules such as gadolinium chelates, which cannot provide a high contrast image for early diagnosis of cancer because of its low sensitivity and poor selectivity. By applying SiNPs, thousands of MRI agents like gadolinium chelates may be loaded into one nanoparticle. This high loading efficiency in SiNPs enhances the sensitivity of the MRI agent. Taylor et al. synthesized a highly efficient MSN-based MRI contrast agent for in vitro and in vivo MRI imaging.74 This MSN-based MRI contrast agent was an ideal platform for MRI benefitting from its large payload of Gd centers and enhanced water accessibility of the Gd chelates. This is the key parameter for the design of highly efficient MRI contrast agents. Lin et al. modified the Gd chelates onto SiNPs using layer-by-layer self-assembly coupled with doping a fluorescence contrast agent during the synthesis.75 With the modification of a targeting peptide, the K7RGD-SiNPs had the ability to detect certain tumor cells using MRI and fluorescence imaging. Also, Gd chelates could be coated onto SiNPs through lipid coating.76 Coupled with quantum dots doping in the same SiNPs, the imaging nanocomposite had the abilities of fluorescence and MRI imaging for tumor cells.

In addition, super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) nanoparticles are another type of useful MRI contrast agents for tumor imaging in vitro and in vivo. In 2008, Kim et al. doped single magnetic iron oxide nanoparticle in mesoporous silica nanoparticles (Fe3O4@mSiO2), followed by doping the fluorescent dye in the silica shell to form multifunctional nanoparticles for tumor imaging and therapy (Figure 3A).77 PEG modification on SiNPs increased the biocompatibility and targeting efficiency to tumor sites through EPR effects. After intravenous injection of the Fe3O4@mSiO2 into the mice implanted with MCF-7 cells, researchers took the T2-weighted MRI imaging and observed that the T2 signal intensity in the tumor site decreased, indicating the accumulation of Fe3O4@mSiO2 in the tumor site (Figure 3B). Meanwhile, the fluorescence of the Fe3O4@mSiO2 in the tumor site was captured to verify the results from the T2-weighed MR imaging. Furthermore, the nanoparticles coupled with MRI agents and drugs were developed for simultaneous tumor imaging and therapy. For instance, Liong et al. enclosed multiple magnetites in the core of SiNPs, and then doped fluorescent dye or drug in SiNPs to form a multifunctional delivery vehicle for tumor imaging and therapy. With the modification of folic acids on the surface of SiNPs, these multifunctional SiNPs showed the potential for active targeting tumor sites for diagnosis and therapy.78 Lee et al. developed a novel silica nanovector for tumor MRI, fluorescence imaging and drug delivery. The fluorescent dyes were doped into SiNPs, whereas multiple iron oxide nanoparticles were decorated on the surface of the SiNPs.79 In addition to tumor imaging, iron oxide nanoparticles embedded SiNPs were widely used for MRI imaging of stem cells in vitro and in vivo by varying the targeting ligands.80, 81

Figure 3.

A) Schematic illustration of the synthetic procedure for magnetite nanocrystal /mesoporous silica core–shell NPs. B) fluorescence images of subcutaneously injected MCF-7 cells labeled with Fe3O4@mSiO2(R) (10 µg Fe mL−1) and control MCF-7 cells without labeling into each dorsal shoulder of a nude mouse. Reprinted from ref. 77 with permission by Wiley-VCH.

4. Drug and gene delivery using silica nanoparticles

4.1 Drug delivery

SiNPs have been widely used for tumor therapy in vitro and in vivo because of their unique properties, such as large surface area and pore volume, easy functionalization, great biocompatibility, high stability, and controllable particle sizes. In the following section, we will discuss applications of SiNPs for drug delivery into tumor cells or tissues.

4.1.1 Chemotherapeutic agents

Chemotherapy is a mainstream treatment of cancer. However, there are some limitations of existing chemotherapeutics, such as the hydrophobicity, low targeting efficiency, side toxic effects, and unsatisfactory therapeutic efficacy. To overcome these limitations, biocompatible SiNPs have been employed as nano-vehicles for tumor targeting imaging and therapy. Camptothecin (CPT) and its derivatives are one of the most promising anticancer drugs; however, their hydrophobic property limits their clinical applications. In order to transfer CPT efficiently into tumor tissues without modification of the molecule, Lu et al. reported a method for loading CPT in MSNs (MSNs/CPT) and delivering it to cancer cells to induce apoptosis.82 Furthermore, they investigated anticancer effects of the MSNs/CPT in vivo.65 Folic acid was modified onto MSNs for active targeting cancer cells (Figure 4A). As shown in Figure 4B, folic acid-modified MSNs/CPT resulted in a higher therapeutic efficiency to SK-BR-3 cells than that to MCF-7 cells because of the high level expression of folate receptor on SK-BR-3 cells. In contrast, the MSNs/CPT without folic acid modification demonstrated similar cytotoxicity to these two human cancer cells. This indicated that the folic acid-mediated active targeting to folate receptor positive tumor cells by MSNs showed efficacy in tumor treatment. Having achieved the exciting results from cancer cell treatment of MSNs/CPT, researchers investigated the in vivo tumor-suppressing effect of MSNs/CPT. As shown in Figure 4C and D, nude mice with xenografts of human breast cancer cell MCF-7 received different therapeutic agents. The MSNs/CPT and folic acid modified MSNs/CPT showed faster tumor-shrinking effects in mice than that of the CPT alone group, and no obvious subcutaneous tumors were found in these two testing groups at the end points. In contrast, saline solution and MSNs did not inhibit the tumor growth in nude mice. In the work of Tsai et al., a non-cytotoxic anionic surfactant was coupled to the control releasing of a hydrophobic drug, resveratrol, loaded in the MSNs to kill HeLa cells.83 The amount of resveratrol-loaded MSNs uptaken by tumor cells increased by almost 4-fold compared to calcined MSNs due to the targeting delivery of surfactant. In another work, TAT peptide-modified MSNs were used for the delivery of doxorubicin (DOX) to nuclei of cancer cells.39 With the modification of a TAT peptide on the surface of these MSNs, it was found that 50 nm or smaller TAT-MSNs can efficiently target the nucleus of HeLa cells. DOX in TAT-MSNs was released into the nucleus to kill cancer cells with enhanced efficiencies compared to MSNs. In addition, other targeting ligands such as aptamer have also been used for drug delivery using SiNPs.84

Figure 4.

A) Schematic illustration of FMSNs modified with folic-acid-targeting ligands on the surface. B) Cell-proliferation assay with FMSNs and F-FMSNs in MCF10F (M) and SK-BR-3(SK) cells. The cells were treated for 48 h with 20 µgmL−1 of nanoparticles only (FMSN), CPT-loaded nanoparticles (FMSN/CPT), CPT-loaded F-FMSNs, or the same concentration of CPT dissolved in DMSO. The cells were then washed and stained with 10% WST-8 solution from the cell-counting kit (DojindoCo.) for 2 h. The absorbances were measured at 450 nm with a plate reader. The percentages of each sample relative to control cells are presented as mean values ± SD. C) The average tumor volumes are shown as means ± SD. *= p < 0.05; **= p < 0.01. D) Representative images of mice from different groups. Red arrows indicate the location of subcutaneous tumors. Reprinted from ref. 65 with permission by Wiley-VCH.

In order to control the release of drugs loaded in SiNPs, stimuli-responsive released systems based on SiNPs were developed. MSNs have size tunable pores which allow adjusting the loading of different drug molecules and triggering the drug release from MSNs. Therefore, we will focus on the applications of stimuli-responsive release MSNs. These MSNs-based stimuli-responsive systems were originally developed by Lin’s group.85 The principle of these systems is shown in Figure 5.25 Drugs were loaded into MSNs through diffusion and chemical binding. Then, a gatekeeper, such as nanoparticles, organic molecules, and supermolecular assemblies, was used to regulate the encapsulation and release of drugs by certain stimulus conditions in tumor cells and tissues. Through this controllable loading and releasing manners in MSNs, the treatment efficacy for cancer increased markedly.

Figure 5.

Representation of MSNs loaded with guest molecules and end-capped with a general gatekeeper. Reprinted from ref. 25 with permission by Elsevier.

Using a self-complementary duplex DNA as the gatekeeper to control the release of drugs in certain regions, Chen et al. developed a MSNs-based drug delivery system for cancer therapy.86 The drugs were trapped within the porous channels of MSNs, and then the self-complementary duplex DNA was modified on the surface of MSNs to regulate the release of drugs. When the duplex DNA was denatured by heating or hydrolyzed by endonucleases in cancer cells, drugs in MSNs were released to kill cancer cells. Singh et al. coated MSNs with a shell of polymer, which was then triggered by the temperature and proteases presented in tumor cells.29 Afterwards, DOX that was doped in the core and shell was released into tumor cells to induce apoptosis. pH can also be used as another triggering factor for drug release from MSNs for tumor therapy. Meng et al. developed β-cyclodextrin (β-CD)-coated MSNs for DOX delivery into cancer cells.87 The β-CD-based nanovalves were responsive to the endosomal acidification conditions in cancer cell lines. Upon the triggering by the acid condition, the DOX in the MSNs could be released into nuclei of cancer cells. Furthermore, Gao et al. investigated the effect of pore sizes and pH for drug release rates in MSNs-based drug delivery systems.28 With increasing pore sizes, drug release rates also increased. In addition, acid conditions could trigger the release of the drug into tumor cells.

Nanoparticles were another kind of gatekeeper for the controllable MSNs-based drug delivery system. Quantum dots,85 gold nanoparticles,88 and iron oxide nanoparticles79 have been investigated for controllable drug release systems. Utilizing stimuli-responsive drug delivery systems based on MSNs, drugs for cancer therapy could be efficiently and specifically delivered to cancer cells and tissues in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, more effective therapy and fewer side effects of the chemotherapeutic drugs could be obtained by the stimuli-responsive MSNs.

4.1.2 Photodynamic therapy agents

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) of cancers is a relatively new treatment compared to chemotherapy. Photosensitizer, oxygen, and irradiation constitute necessary factors for PDT. Upon the irradiation of light, photosensitizers absorb photons and transfer the energy to surrounding oxygen to generate singlet oxygen that can irreversibly oxidize molecules, such as proteins and nucleic acids of tumor cells, resulting in cell killing.

Several photosensitizers have been developed for PDT. However, there are some limitations for clinical applications of these photosensitizers, such as hydrophobic property, low target efficiency to tumor sites, instability in biological environments, and side effects to normal cells. In order to overcome these limitations, SiNPs were used to deliver the photosensitizers to tumor cells with high targeting efficiency and low side effects. In 2003, Roy et al. entrapped a hydrophobic photosensitizer, 2-devinyl-2-(1-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide (HPPH), in SiNPs for tumor therapy.89 With the irradiation of visible light, irreversible destruction of tumor cells was induced by singlet oxygen generated by the photodynamic process. To increase the penetration depth of light, Kim et al. used a two-photo absorbing fluorescent dye co-encapsulating with HPPH in SiNPs to form a photodynamic therapy system to effectively kill tumor cells.90 In these two examples, the photosensitizers were encapsulated in the SiNPs through a physical process.

Drug leakage during systemic circulation is one of the disadvantages of these systems. Ohulchanskyy et al. covalently incorporated a photosensitizer to SiNPs and investigated singlet oxygen generation efficiency upon photo-irradiation.91 Tumor cells incubated with these SiNPs demonstrated low survival rates than those of the control group. Zhang et al. described a versatile photosensitizer delivery system based on SiNPs for tumor therapy.92 In their design, an upconverting nanoparticle was doped in SiNPs, and the photosensitizers were encapsulated within the silica shell. The surface of the silica shell was modified with antibodies that were specific for antigens of tumor cells. Upon the NIR irradiation, the upconverting nanoparticles absorbed the NIR light and transferred the energy to photosensitizers in the shell to generate singlet oxygen, leading to oxidative damage to tumor cells nearby the nanoparticles. An in vivo PDT based on SiNPs was investigated by He et al. in 2009.30 Methylene blue (MB), a NIR photosensitizer, was doped in phosphate-modified SiNPs. It showed that these MB-SiNPs not only caused the death of tumor cells in vitro, but also induced damage on mouse tumor tissues due to the NIR irradiation (Figure 6). Meanwhile, fluorescence in vivo imaging was obtained by the fluorescence emission of MB in the SiNPs. Also, Gary-Bobo et al. combined a chemotherapeutic agent and photosensitizer into SiNPs for both chemotherapy and PDT to further enhance tumor killing.93 Zhu et al. encapsulated the photosensitizers in small MSNs with a high loading capacity.94 The resulting delivery system increased the amount of photosensitizers in cancer cells by two orders of magnitude and the therapy efficiency was enhanced by more than four-folds.

Figure 6.

In vivo imaging and PDT of subcutaneous-HeLa-tumor-xenografted mice after different treatment: (A) 100 ml 44 mg/ml MB-encapsulated PSiNPs injection and 5 min light exposure with power intensity of 500 mw/cm2, the red circle indicates the region injected the MB-encapsulated PSiNPs and with light exposure; (B) 100 ml 44 mg/ml MB-encapsulated PSiNPs injection; and (C) 5 min light exposure with power intensity of 500 mw/cm2. Reprinted from ref. 30 with permission by Elsevier.

4.2 Gene therapy using SiNPs-based vectors

The development of gene therapy technologies has generated great interest in cancer treatments about two decades ago. However, cancer gene therapy lacks specific delivery systems for carrying therapeutic genes to target tumor cells. Since He et al. reported that SiNPs could protect DNA from the cleavage by nucleases in 2003, these nanomaterials might have the potential for gene delivery to tumor cells.95 Antisense oligonucleotide-loaded SiNPs were also developed for targeting HeLa cells by the same group.96 It was found that these nanoparticles efficiently inhibited the proliferation and survival of HeLa cells. Xia et al. applied DNA or siRNA attached and polyethyleneimine (PEI) modified MSNs for gene therapy.11 To improve this technology, a GFP-containing siRNA was used as a model for siRNA delivery to kill tumor cells. Flow cytometry (Figure 7A) and fluorescence confocal microscopy (Figure 7B) were used to evaluate the transfection efficiency of the siRNA-loaded MSNs. The results showed that the MSNs coated with 10 kD PEI had the best transfection efficiency in transducing the GFP-siRNA into tumor cells. The fluorescence intensity of GFP in these cells was the lowest compared to the control groups due to the death of targeted cells. Meanwhile, a GFP-expressing plasmid was also delivered by MSNs into tumor cells to test the feasibility of the SiNPs for DNA delivery.

Figure 7.

GFP knockdown by siRNA in stable transfected GFP-HEPA cells. HEPA-1 cells with stable GFP expression were used for siRNA knockdown assays. MSNP coated with different size PEI polymers were used to transfect GFP-specific or scrambled siRNA and the results compared with LipofectAmine 2000 as transfection agent. (A) GFP knockdown was assessed by flow cytometry in which GFP MFI was normalized to the value of control untransduced cells (100%). (B) Confocal pictures were taken showing GFP knockdown in GFP-HEPA cells. TEX 615-labeled siRNA was used to show the cellular localization of the nucleic acid bound particles (red dots). X, scrambled siRNA. The experiment was reproduced three times. Reprinted from ref. 13 with permission by the American Chemical Society.

Overexpression of drug efflux transporters is one of the issues for cancer therapy. For example, P-glycoprotein (Pgp) is one of the well-known multiple drug resistance proteins. For efficient treatment of tumor cells with chemotherapeutics, siRNA used to silence the expression of Pgp was a new approach for the drug resistant tumor cells. Meng et al. designed MSNs to deliver DOX and Pgp for tumor therapy.97 This group found that the fluorescence intensity of DOX in tumor cells increased dramatically when the Pgp siRNA was co-delivered with DOX using MSNs, indicating that the Pgp expression was silenced by a Pgp siRNA on the MSNs. By staining with Annexin V-SYTOX, an apoptotic indicator, the tumor cells treated with the siRNA and DOX co-delivered MSNs showed significantly increased apoptosis compared to those treated with free DOX or DOX delivered by non-siRNA MSNs. Pgp is a pump resistant protein for multi-drug resistance, while for the nonpump resistance of multi-drug resistance, activation of cellular anti-apoptotic defense triggered by Bcl-2 protein is the main mechanism. To deliver a Bcl-2 siRNA into tumor cells, Chen et al. loaded Bcl-2 siRNA and DOX in MSNs to enhance chemotherapy.98 DOX and Bcl-2 siRNA were loaded in the pore channel of MSNs (Figure 8). When the particles were taken up by tumor cells, the gatekeeper, G2 PAMAM, was opened by the acid pH in the endosome. Subsequently DOX was released into cells to induce apoptosis, and Bcl-2 siRNA was released to silence Bcl-2 protein to increase apoptosis. Owing to the Bcl-2 siRNA directed delivery, the chemotherapeutic efficacy of DOX was enhanced in tumor cells.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of a co-delivery system based on MSNs to deliver Dox and Bcl-2-targeted siRNA simultaneously to A2780/AD human ovarian cancer cells for enhanced chemotherapy efficacy. Reprinted from ref. 98 with permission by Wiley-VCH.

5. Multifunctional silica nanoparticles

To increase the therapy efficiency, not only is the therapy process important, but also diagnosis, especially at early stages, is crucial for patient survival. Theranostics has emerged as an inter-disciplinary field by integrating imaging and therapy. Therefore, the development of novel multifunctional platforms for both imaging and therapy is one of the challenges in cancer treatments.99 The success of SiNPs in delivery of imaging agents and drugs attests the potential of SiNPs for theranostics of tumor using multifunctional nanomaterial entities.100 The capability of these multifunctional nanomaterials in imaging provides high quality images for guiding therapeutic agents.101 During and after the therapy, the images could be used for monitoring the effects of therapy. These properties may improve drug delivery efficacy and survival rates, and minimize side effects of drugs to normal tissues.

There are at least three different models for multifunctional SiNPs including multimodel imaging, multimodel therapy and multimodel theronostics. For the multimodel imaging system, the designed SiNPs possess different kind of imaging strategies, such as optical imaging, MRI, PET, CT, ultrasonic, etc. This multimodel imaging system can greatly increase the diagnosis accuracy and sensitivity.101, 102 For example, Huang et al. developed a multifunctional MSN that incubated fluorescence imaging, MRI and PET for tumor imaging and probe localization.103 The multimodel therapy system contains the SiNPs that incubated different therapeutic strategies. For example, chemotherapy, gene therapy, thermotherapy, PDT and photothermal therapy (PTT) can be combined for the multimodel therapy of tumor.104, 105 The multimodel therapy system can enhance the therapeutic efficiency. Furthermore, the most important multifunctional SiNPs possess multimodel imaging abilities and multimodel therapeutic abilities for tumor diagnosis and therapy,106–109 which is illustrated as following.

Liong et al. proposed the use of multifunctional MSNs for imaging, targeting, and drug delivery to tumors.78 The iron oxide nanocrystal-doped in MSNs and fluorescein on the silica shell provided the feasibility of MRI and fluorescence imaging for tumors. Folic acid was used to target tumor cells and tissues due to the high expression of folate receptor on tumor cells. A drug was loaded in the pore channel of MSNs for killing tumor cells. Meanwhile, the iron oxide nanocrystal could be used for magnetic manipulation to modulate the platform to a desired location. Therefore, the multifunctional MSNs boasted five functions together for tumor imaging and therapy. Chen et al. developed similar multifunctional SiNPs for simultaneous cell imaging and drug delivery.110 Iron oxide nanocrystal or gold nanoparticles were doped in SiNPs, and then co-loaded with a chemotherapeutic agent. In vitro and in vivo MRI and therapeutic functionalities of the platform were shown to be promising for tumor imaging and therapy in mice.

In 2011, Huang et al. constructed silica-modified gold nanorods for X-ray/CT imaging and photothermal therapy for tumor.111 As shown in Figure 9A, gold nanorods were encapsulated in the silica nanoshell, which was modified with folic acids for active targeting tumor cells. Upon the irradiation of light, the tumor cells that underwent apoptosis were increased as stained by PI (Figure 9B). Furthermore, in vivo X-ray imaging showed that tumor tissue displayed a sharp contrast compared to normal tissues (Figure 9C). To explore the thermal effect of gold nanoparticles, Huschka et al. investigated the thermal effect of gold nanoshell and gold nanorod for DNA release, which might be useful for tumor targeting gene delivery and therapy.112 With a similar design, Zhang et al. developed mesoporous silica-coated gold nanorods (Au@SiO2)for cancer treatment.113 The Au@SiO2 was monitored using two-photon imaging. Doxorubicine was also doped into the nanocomposite which could be released by the low power density laser for chemotherapy. Meanwhile, with high power density laser, the gold nanorods induced photothermal effect could be used for the hyperthermia. Similarly, He et al. developed a MB-doped SiNPs for simultaneous fluorescent imaging and PDT of tumor cells in vitro and tissues in vivo.30 Zhao et al. doped upconversion nanoparticles into SiNPs, which were then coupled with photosensitizer for NIR imaging and PDT.114 Interestingly, this nanomaterial also demonstrated good MR contrast in tumor cells, and thereby could be used for MRI. In a recent review, Bardhan et al. summarized the design and synthesis of nanoshell-based theranostic agents using enhanced near-infrared fluorescence or magnetic resonance imaging guided photothermal ablation in both cellular models and animal models.115

Figure 9.

A) Synthetic procedure of GNR-SiO2-FA. B) Photo-thermal therapy effects on GC803 cells incubated with 12.5 mM of GNR-SiO2-FA for 24 h at 37°C in the dark prior to irradiation for 3 min with 808 nm laser. (a and b) MGC803 cells on the laser spot center, (d and d) GC803 cells on the boundary of laser spot. (a and c) Bright field, (b and d) Fluorescence field. C) Real-time in vivo X-ray images after intravenous injection of GNR-SiO2-FA in nude mice at different time points. (a) The photograph of the tumor tissue; (b) the X-ray image at 0 h; (c) the X-ray image at 0 h (in color); (d) the X-ray image at 12 h, (e) the X-ray image at 12 h (in color); (f) the X-ray image at 24 h (in color). Reprinted from ref. 111 with permission by Elsevier.

Collectively, the goals of theranostics may be achieved by combining imaging agents and therapy agents into appropriate SiNPs for tumor imaging and therapy. More important, these multifunctional nanoparticles may provide combined imaging strategies, such as fluorescence and MR imaging, fluorescence and X-ray imaging, fluorescence and Raman imaging, and MR and X-ray imaging, for precise guidance of drug selection and monitoring the efficacy during tumor therapy.

6. Biocompatibility of silica nanoparticles

With the development of SiNPs for cancer diagnosis and therapy, the safety issues have been gradually recognized and need serious and full further investigation. The biocompatibility of SiNPs at different levels, including cells, tissues and animals, were demonstrated by several groups. Because of the chemical inert of silica, the SiNPs showed great biocompatibility at different levels. However, the physiochemical properties, such as size, surface charge and modification, can all play important roles on the toxicity and pharmacokinetics of SiNPs in the cells and animals. Meanwhile, because of the various synthesis methods and treated bio-matrixes, it is hard to draw a general conclusion about the toxicity of the SiNPs on cells and animals. Herein, we briefly reviewed the recent developments of the investigations of the in vitro and in vivo toxicity of SiNPs regarding the size and surface modification of the nanoparticles.

The toxicity of SiNPs was affected by several factors, including the cell lines, concentrations, particle sizes, surface charges, particle shapes and structures of the SiNPs. Mou et al. investigated the cellular uptake amount of different sized MSNs using Hela cells.35 They found that the MSNs of 50 nm diameter showed the highest uptake efficiency. Jin et al. synthesized different sizes core/shell SiNPs and investigated their cytotoxicity.38 It was found that the smaller SiNPs (23 ± 3 nm) showed higher cytotoxicity than that of the larger SiNPs (85 ± 5 nm). At the animals level, He et al. investigated the biodistribution and urinary excretion of MSNs with different particle size from 80 nm to 360 nm.116 They found that the accumulation of MSNs in the liver and spleen and the excretion efficiency increased with the increase of particle size from 80, 120, to 200 nm after intravenous injection. However, within one month, neither MSNs nor PEGylated MSNs showed toxicity to the treated mice.

The surface modification of SiNPs was another factor that could affect the toxicity on the cells. The SiNPs with cationic charge surface had strong interaction with the cell membrane because of the electrostatic interaction, which would induce more immune response and cytotoxicity compared with the neutral and anion SiNPs. For the unmodified SiNPs, the surface was covered with silanol groups which induced a negative charge of the SiNPs. However, other functional groups, such as amino group, carboxyl group, phosphonate group and PEG were easily modified on the surface of the SiNPs with the silanol chemistry. Among these groups, PEG was by far the best way to increase the dispersity and increase the biocompatibility of the SiNPs. With the modification of PEG, the blood half-life in small animals would significantly increase, and the accumulation in RES tissues would greatly decrease, which was enhancing the tumor targeting efficiency and biocompatibility. With PEGylation, the endocytosis of the SiNPs may be diminished, which could reduce the hemolytic activity and cytotoxicity.117, 118 After intravenous injection of different modified SiNPs, He et al. found that all the SiNPs accumulated in the liver and spleen with the increase of time.33 However, the PEGylated SiNPs showed longer blood circulation times and lower uptake by the RES tissues than that of the hydroxyl modified SiNPs and carboxyl modified SiNPs. Meanwhile, all the SiNPs were partly excreted through the renal excretion route, which was confirmed by the fluorescence in the bladder and urine, and TEM images of SiNPs in the urine. The excretion process might greatly reduce the long-term toxicity of SiNPs in vivo.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, the applications of SiNPs in in vitro and in vivo tumor imaging demonstrated the potential for further developing the SiNPs into clinically-useful reagents. Fluorescence and MRI imaging are currently the main strategies for the applications of SiNPs in cancer imaging. X-ray/CT may also be used along with SiNPs as imaging agents. As biocompatible nanomaterials, SiNPs can be used for drug delivery, especially for chemotherapeutic agents, photosensitizers and photothermal agents. Stimuli-responsive MSNs for drug delivery and release have improved therapeutic efficacy and decreased side effects. Furthermore, the multifunctional SiNPs that combined imaging and therapy functionalization provided the most promising tool for tumor diagnostics and treatment.

However, there are some challenges that need to be resolved before successful applications of SiNPs in clinics. First of all, the delivery efficiency to the targeting tumor cells and tissues should be improved. Even several targeting ligands, including antibodies, aptamers and peptides, have been tested for the active targeting for tumor diagnosis and therapy; most of them have great absorption in the liver and spleen. This might induce side effects to normal tissues and organs. Therefore, the excellent targeting efficiency to tumor is of great promise. Secondly, multifunctional SiNPs is in the early stage for tumor diagnosis and therapy. With different functions, the multifunctional SiNPs can accurately detect/arrive tumor sites, and then kill the tumor cells. Importantly, the therapy efficiency can also be monitored. By carefully designing of the multifunctional SiNPs, it will be of significance to accomplish all the necessary function in one SiNP composite. Thirdly, the biocompatibility and toxicity of the SiNPs to normal tissues of rodents and primates need extensive investigation. Several investigations in SiNP toxicity have been recently carried out by different groups; however, it is premature to make a general conclusion on the toxicity of the SiNPs in bio-systems. Much research needs to be done before the realization of the great potential of novel SiNPs in bio-medical applications. For example, a systemic investigation for the toxicity in vitro and in vivo should be performed in small animal and primates. We look forward to witnessing more promising discoveries for tumor diagnosis and therapy using novel silica nanomaterials.

This review summarized the development of the silica nanoparticles for tumor imaging and therapy. With the great biocompatibility, easy synthesis and modification, SiNPs were designed to carry out different functions in the treatment of cancer. The imaging ability can be used for the diagnosis of cancer, and the therapy ability can be used for the treatment of cancer. By combining these two functions, SiNPs are promising for the diagnosis and therapy of cancer in the future.

Acknowledgments

All sources of support for research: This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Grants CHE 0911472 and CHE 0947043 to J.X.Z. This work was also supported by the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (FAMRI, Grant #103007), National Institute of Health AI101973-01, and AI097532-01A1 to M.W.

Abbreviations

- SiNPs

silica nanoparticles

- MSNs

mesoporous silica nanoparticles

- C/S SiNPS

core/shell silica nanoparticle

- QDs

quantum dots

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

positron emission tomography

- X-ray CT

X-ray computed tomography

- TEOS

tetraethyl orthosilicate

- PEG

polyethylene glycol

- RES

reticuloendothelial system

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- FMSNs

fluorescent silica nanoparticle

- F-FMSNs

folic acid modified fluorescent silica nanoparticles

- SPIO

super paramagnetic iron oxide

- CPT

camptothecin

- DOX

doxorubicin

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- HPPH

2-devinyl-2-(1-hexyloxyethyl) pyropheophorbide

- MB

methylene blue

- PEI

polyethyleneimine

- Pgp

P-glycoprotein

- PTT

photothermal therapy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhao Y, Trewyn BG, Slowing II, Lin VSY. Mesoporous Silica nanoparticle-based double drug delivery system for glucose-responsive controlled release of insulin and cyclic AMP. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8398–8400. doi: 10.1021/ja901831u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patil YB, Swaminathan SK, Sadhukha T, Ma L, Panyam J. The use of nanoparticle-mediated targeted gene silencing and drug delivery to overcome tumor drug resistance. Biomaterials. 2010;31:358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fang W, Yang J, Gong J, Zheng N. Photo- and pH-Triggered Release of Anticancer Drugs from Mesoporous Silica-Coated Pd@Ag Nanoparticles. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:842–848. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klichko Y, Liong M, Choi E, Angelos S, Nel AE, Stoddart JF, et al. Mesostructured silica for optical functionality, Nanomachines, and Drug Delivery. J Amer Ceram Soc. 2009;92:S2–S10. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-2916.2008.02722.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, Noh Y-W, Heo MB, Cho MY, Lim YT. Multifunctional hybrid nanoconjugates for efficient in vivo delivery of immunomodulating oligonucleotides and enhanced antitumor immunity. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:9670–9673. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bagalkot V, Gao X. siRNA-aptamer chimeras on nanoparticles: preserving targeting functionality for effective gene silencing. ACS nano. 2011;5:8131–8139. doi: 10.1021/nn202772p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sardesai NP, Barron JC, Rusling JF. Carbon nanotube microwell array for sensitive electrochemiluminescent detection of cancer biomarker proteins. Anal Chem. 2011;83:6698–6703. doi: 10.1021/ac201292q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen T, Shukoor MI, Wang R, Zhao Z, Yuan Q, Bamrungsap S, et al. Smart multifunctional nanostructure for targeted cancer chemotherapy and magnetic resonance imaging. ACS nano. 2011;5:7866–7873. doi: 10.1021/nn202073m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao Y, Yang C, Liu X, Ma R, Kong D, Shi L. A multifunctional nanocarrier based on nanogated mesoporous silica for enhanced tumor-specific uptake and intracellular delivery. Macromol Biosci. 2012;12:251–259. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Unezaki S, Maruyama K, Hosoda J-I, Nagae I, Koyanagi Y, Nakata M, et al. Direct measurement of the extravasation of polyethyleneglycol-coated liposomes into solid tumor tissue by in vivo fluorescence microscopy. Int J Pharm. 1996;144:11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia T, Kovochich M, Liong M, Meng H, Kabehie S, George S, et al. Polyethyleneimine coating enhances the cellular uptake of mesoporous silica nanoparticles and allows safe delivery of siRNA and DNA constructs. ACS nano. 2009;3:3273–3286. doi: 10.1021/nn900918w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu X, He X, Wang K, Xie C, Zhou B, Qing Z. Ultrasmall near-infrared gold nanoclusters for tumor fluorescence imaging in vivo. Nanoscale. 2010;2:2244–2249. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00359j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon S, Teichmann E, Young K, Finnie K, Rades T, Hook S. In vitro and in vivo investigation of thermosensitive chitosan hydrogels containing silica nanoparticles for vaccine delivery. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2010;41:360–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao X, Cui Y, Levenson RM, Chung LW, Nie S. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969–976. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng YC, Samia A, Meyers JD, Panagopoulos I, Fei B, Burda C. Highly efficient drug delivery with gold nanoparticle vectors for in vivo photodynamic therapy of cancer. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:10643–10647. doi: 10.1021/ja801631c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, Tsay JM, Doose S, Li JJ, et al. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science. 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moon HK, Lee SH, Choi HC. In vivo near-infrared mediated tumor destruction by photothermal effect of carbon nanotubes. ACS nano. 2009;3:3707–3713. doi: 10.1021/nn900904h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lewin M, Carlesso N, Tung CH, Tang XW, Cory D, Scadden DT, et al. Tat peptide-derivatized magnetic nanoparticles allow in vivo tracking and recovery of progenitor cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2000;18:410–414. doi: 10.1038/74464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Z, Tong R, Mishra A, Xu W, Wong GCL, Cheng J, et al. Reversible cell-specific drug delivery with aptamer-functionalized liposomes. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6494–6498. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu SH, Hung Y, Mou CY. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as nanocarriers. Chem Commun. 2011;47:9972–9985. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11760b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumer B, Gao J. Theranostic nanomedicine for cancer. Nanomedicine. 2008;3:137–140. doi: 10.2217/17435889.3.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Louie A. Multimodality imaging probes: design and challenges. Chem Rev. 2010;110:3146–3195. doi: 10.1021/cr9003538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosenholm JM, Sahlgren C, Linden M. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for combined therapeutic, diagnostic and targeted action in cancer treatment. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:1166–1186. doi: 10.2174/138945011795906624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trewyn BG, Giri S, Slowing II, Lin VSY. Mesoporous silica nanoparticle based controlled release, drug delivery, and biosensor systems. Chem Commun. 2007:3236–3245. doi: 10.1039/b701744h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slowing II, Vivero-Escoto JL, Wu C-W, Lin VSY. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as controlled release drug delivery and gene transfection carriers. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2008;60:1278–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bae SW, Tan W, Hong JI. Fluorescent dye-doped silica nanoparticles: new tools for bioapplications. Chem Commun. 2012;48:2270–2282. doi: 10.1039/c2cc16306c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, Barnes JC, Bosoy A, Stoddart JF, Zink JI. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2590–2605. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15246g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao Y, Chen Y, Ji X, He X, Yin Q, Zhang Z, et al. Controlled intracellular release of doxorubicin in multidrug-resistant cancer cells by tuning the shell-pore sizes of mesoporous silica nanoparticles. ACS nano. 2011;5:9788–9798. doi: 10.1021/nn2033105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh N, Karambelkar A, Gu L, Lin K, Miller JS, Chen CS, et al. Bioresponsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for triggered drug release. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19582–19585. doi: 10.1021/ja206998x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He X, Wu X, Wang K, Shi B, Hai L. Methylene blue-encapsulated phosphonate-terminated silica nanoparticles for simultaneous in vivo imaging and photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5601–5609. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Herr JK, Smith JE, Medley CD, Shangguan D, Tan W. Aptamer-conjugated nanoparticles for selective collection and detection of cancer cells. Anal Chem. 2006;78:2918–2924. doi: 10.1021/ac052015r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu J, Li Z, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. In vivo tumor suppression efficacy of mesoporous silica nanoparticles-based drug-delivery system: enhanced efficacy by folate modification. Nanomedicine. 2012;8:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.He X, Nie H, Wang K, Tan W, Wu X, Zhang P. In vivo study of biodistribution and urinary excretion of surface-modified silica nanoparticles. Anal Chem. 2008;80:9597–9603. doi: 10.1021/ac801882g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu T, Li L, Teng X, Huang X, Liu H, Chen D, et al. Single and repeated dose toxicity of mesoporous hollow silica nanoparticles in intravenously exposed mice. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1657–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lu F, Wu S-H, Hung Y, Mou C-Y. Size effect on cell uptake in well-suspended, uniform mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Small. 2009;5:1408–1413. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tang F, Li L, Chen D. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: synthesis, biocompatibility and drug delivery. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1504–1534. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bagwe RP, Yang C, Hilliard LR, Tan W. Optimization of dye-doped silica nanoparticles prepared using a reverse microemulsion method. Langmuir. 2004;20:8336–8342. doi: 10.1021/la049137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin Y, Lohstreter S, Pierce DT, Parisien J, Wu M, Hall C, et al. Silica nanoparticles with continuously tunable sizes: synthesis and size effects on cellular contrast imaging. Chem Mater. 2008;20:4411–4419. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan L, He Q, Liu J, Chen Y, Ma M, Zhang L, et al. Nuclear-targeted drug delivery of TAT peptide-conjugated monodisperse mesoporous silica nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:5722–5725. doi: 10.1021/ja211035w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossi LM, Shi L, Quina FH, Rosenzweig Z. Stober synthesis of monodispersed luminescent silica nanoparticles for bioanalytical assays. Langmuir. 2005;21:4277–4280. doi: 10.1021/la0504098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Napierska D, Thomassen LCJ, Rabolli V, Lison D, Gonzalez L, Kirsch-Volders M, et al. Size-dependent cytotoxicity of monodisperse silica nanoparticles in human endothelial cells. Small. 2009;5:846–853. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torchilin V. Tumor delivery of macromolecular drugs based on the EPR effect. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2011;63:131–135. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li L, Tang F, Liu H, Liu T, Hao N, Chen D, et al. In vivo delivery of silica nanorattle encapsulated docetaxel for liver cancer therapy with low toxicity and high efficacy. ACS nano. 2010;4:6874–6882. doi: 10.1021/nn100918a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilson NS, Yang B, Yang A, Loeser S, Marsters S, Lawrence D, et al. An Fcgamma receptor-dependent mechanism drives antibody-mediated target-receptor signaling in cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith BR, Cheng Z, De A, Koh AL, Sinclair R, Gambhir SS. Real-time intravital imaging of RGD-quantum dot binding to luminal endothelium in mouse tumor neovasculature. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2599–2606. doi: 10.1021/nl080141f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferris DP, Lu J, Gothard C, Yanes R, Thomas CR, Olsen JC, et al. Synthesis of biomolecule-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles for targeted hydrophobic drug delivery to cancer cells. Small. 2011;7:1816–1826. doi: 10.1002/smll.201002300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Porta F, Lamers GEM, Morrhayim J, Chatzopoulou A, Schaaf M, den Dulk H, et al. Folic acid-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cellular and nuclear targeted drug delivery. Adv Healthcare Mater. 2012;2:281–286. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201200176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhar S, Kolishetti N, Lippard SJ, Farokhzad OC. Targeted delivery of a cisplatin prodrug for safer and more effective prostate cancer therapy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:1850–1855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011379108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Zhao W, Tan W. Bioconjugated silica nanoparticles: Development and applications. Nano Res. 2008;1:99–115. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calfon MA, Rosenthal A, Mallas G, Mauskapf A, Nudelman RN, Ntziachristos V, et al. In vivo near infrared fluorescence (NIRF) intravascular molecular imaging of inflammatory plaque, a multimodal approach to imaging of atherosclerosis. J Vis Exp. 2011;54:e2257. doi: 10.3791/2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Condeelis J, Weissleder R. In vivo imaging in cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a003848. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oleinikov VA. Semiconductor fluorescent nanocrystals (quantum dots) in biological biochips. Bioorg Khim. 2011;37:171–189. doi: 10.1134/s1068162011020117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao X, Tapec-Dytioco R, Tan W. Ultrasensitive DNA detection using highly fluorescent bioconjugated nanoparticles. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:11474–11475. doi: 10.1021/ja0358854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Santra S, Zhang P, Wang K, Tapec R, Tan W. Conjugation of biomolecules with luminophore-doped silica nanoparticles for photostable biomarkers. Anal Chem. 2001;73:4988–4993. doi: 10.1021/ac010406+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veeranarayanan S, Cheruvathoor Poulose A, Mohamed S, Aravind A, Nagaoka Y, Yoshida Y, et al. FITC labeled silica nanoparticles as efficient cell tags: uptake and photostability study in endothelial cells. J Fluoresc. 2012;22:537–548. doi: 10.1007/s10895-011-0991-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu C-L, Lu C-H, Song X-Y, Yang H-H, Wang X-R. Bioresponsive controlled release using mesoporous silica nanoparticles capped with aptamer-based molecular gate. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:1278–1281. doi: 10.1021/ja110094g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.He X, Zhao Y, He D, Wang K, Xu F, Tang J. ATP-responsive controlled release system using aptamer-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2012;28:12909–12915. doi: 10.1021/la302767b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai C-P, Chen C-Y, Hung Y, Chang F-H, Mou C-Y. Monoclonal antibody-functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN) for selective targeting breast cancer cells. J Mater Chem. 2009;19:5737–5743. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar R, Roy I, Ohulchanskyy TY, Goswami LN, Bonoiu AC, Bergey EJ, et al. Covalently dye-linked, surface-controlled, and bioconjugated organically modified silica nanoparticles as targeted probes for optical imaging. ACS nano. 2008;2:449–456. doi: 10.1021/nn700370b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu P, He X, Wang K, Tan W, Ma D, Yang W, et al. Imaging breast cancer cells and tissues using peptide-labeled fluorescent silica nanoparticles. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2008;8:2483–2487. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2008.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X, Yao S, Ahn HY, Zhang Y, Bondar MV, Torres JA, et al. Folate receptor targeting silica nanoparticle probe for two-photon fluorescence bioimaging. Biomed Opt Express. 2010;1:453–462. doi: 10.1364/BOE.1.000453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lebret V, Raehm L, Durand JO, Smaihi M, Werts MH, Blanchard-Desce M, et al. Folic acid-targeted mesoporous silica nanoparticles for two-photon fluorescence. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2010;6:176–180. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2010.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iliuk AB, Hu L, Tao WA. Aptamer in bioanalytical applications. Anal Chem. 2011;83:4440–4452. doi: 10.1021/ac201057w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Medley CD, Bamrungsap S, Tan W, Smith JE. Aptamer-conjugated nanoparticles for cancer cell detection. Anal Chem. 2011;83:727–734. doi: 10.1021/ac102263v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lu J, Liong M, Li Z, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Biocompatibility, biodistribution, and drug-delivery efficiency of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer therapy in animals. Small. 2010;6:1794–1805. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Qian J, Wang D, Cai F, Zhan Q, Wang Y, He S. Photosensitizer encapsulated organically modified silica nanoparticles for direct two-photon photodynamic therapy and In Vivo functional imaging. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4851–4860. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986;46:6387–6392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shukla R, Chanda N, Zambre A, Upendran A, Katti K, Kulkarni RR, et al. Laminin receptor specific therapeutic gold nanoparticles (198AuNP-EGCg) show efficacy in treating prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:12426–12431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121174109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huang X, Luo Y, Li Z, Li B, Zhang H, Li L, et al. Biolabeling hematopoietic system cells using near-infrared fluorescent gold nanoclusters. J Phys Chem C. 2011;115:16753–16763. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hong G, Robinson JT, Zhang Y, Diao S, Antaris AL, Wang Q, et al. In vivo fluorescence imaging with Ag2S quantum dots in the second near-infrared region. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;124:9956–9959. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xiong LQ, Chen ZG, Yu MX, Li FY, Liu C, Huang CH. Synthesis, characterization, and in vivo targeted imaging of amine-functionalized rare-earth up-converting nanophosphors. Biomaterials. 2009;30:5592–5600. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xiong L, Chen Z, Tian Q, Cao T, Xu C, Li F. High contrast upconversion luminescence targeted imaging in vivo using peptide-labeled nanophosphors. Anal Chem. 2009;81:8687–8694. doi: 10.1021/ac901960d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jun B-H, Hwang DW, Jung HS, Jang J, Kim H, Kang H, et al. Ultrasensitive, biocompatible, quantum-dot-embedded silica nanoparticles for bioimaging. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:1843–1849. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taylor KML, Kim JS, Rieter WJ, An H, Lin W, Lin W. Mesoporous silica nanospheres as highly efficient MRI contrast agents. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2154–2155. doi: 10.1021/ja710193c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kim JS, Rieter WJ, Taylor KML, An H, Lin W, Lin W. Self-assembled hybrid nanoparticles for cancer-specific multimodal imaging. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:8962–8963. doi: 10.1021/ja073062z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Koole R, van Schooneveld MM, Hilhorst J, Castermans K, Cormode DP, Strijkers GJ, et al. Paramagnetic lipid-coated silica nanoparticles with a fluorescent quantum dot core: A new contrast agent platform for multimodality imaging. Bioconjuate Chem. 2008;19:2471–2479. doi: 10.1021/bc800368x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim J, Kim HS, Lee N, Kim T, Kim H, Yu T, et al. Multifunctional uniform nanoparticles composed of a magnetite nanocrystal core and a mesoporous silica shell for magnetic resonance and fluorescence imaging and for drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:8438–8441. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liong M, Lu J, Kovochich M, Xia T, Ruehm SG, Nel AE, et al. Multifunctional inorganic nanoparticles for imaging, targeting, and drug delivery. ACS nano. 2008;2:889–896. doi: 10.1021/nn800072t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lee JE, Lee N, Kim H, Kim J, Choi SH, Kim JH, et al. Uniform mesoporous dye-doped silica nanoparticles decorated with multiple magnetite nanocrystals for simultaneous enhanced magnetic resonance imaging, fluorescence imaging, and drug delivery. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;132:552–557. doi: 10.1021/ja905793q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lu CW, Hung Y, Hsiao JK, Yao M, Chung TH, Lin YS, et al. Bifunctional magnetic silica nanoparticles for highly efficient human stem cell labeling. Nano Letter. 2007;7:149–154. doi: 10.1021/nl0624263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu HM, Wu SH, Lu CW, Yao M, Hsiao JK, Hung Y, et al. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles improve magnetic labeling efficiency in human stem cells. Small. 2008;4:619–626. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu J, Liong M, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a delivery system for hydrophobic anticancer drugs. Small. 2007;3:1341–1346. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tsai CH, Vivero-Escoto JL, Slowing II, Fang IJ, Trewyn BG, Lin VS. Surfactant-assisted controlled release of hydrophobic drugs using anionic surfactant templated mesoporous silica nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6234–6244. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.He X, Hai L, Su J, Wang K, Wu X. One-pot synthesis of sustained-released doxorubicin silica nanoparticles for aptamer targeted delivery to tumor cells. Nanoscale. 2011;3:2936–2942. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00913j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lai CY, Trewyn BG, Jeftinija DM, Jeftinija K, Xu S, Jeftinija S, et al. A mesoporous silica nanosphere-based carrier system with chemically removable CdS nanoparticle caps for stimuli-responsive controlled release of neurotransmitters and drug molecules. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4451–4459. doi: 10.1021/ja028650l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen C, Geng J, Pu F, Yang X, Ren J, Qu X. Polyvalent nucleic acid/mesoporous silica nanoparticle conjugates: dual stimuli-responsive vehicles for intracellular drug delivery. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:882–886. doi: 10.1002/anie.201005471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, Zhao Y-L, Tamanoi F, Stoddart JF, et al. Autonomous in vitro anticancer drug release from mesoporous silica nanoparticles by pH-sensitive nanovalves. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12690–12697. doi: 10.1021/ja104501a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liu R, Zhang Y, Zhao X, Agarwal A, Mueller LJ, Feng P. pH-responsive nanogated ensemble based on gold-capped mesoporous silica through an acid-labile acetal linker. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1500–1501. doi: 10.1021/ja907838s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Roy I, Ohulchanskyy TY, Pudavar HE, Bergey EJ, Oseroff AR, Morgan J, et al. Ceramic-based nanoparticles entrapping water-insoluble photosensitizing anticancer drugs: a novel drug-carrier system for photodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7860–7865. doi: 10.1021/ja0343095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kim S, Ohulchanskyy TY, Pudavar HE, Pandey RK, Prasad PN. Organically modified silica nanoparticles co-encapsulating photosensitizing drug and aggregation-enhanced two-photon absorbing fluorescent dye aggregates for two-photon photodynamic therapy. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2669–2675. doi: 10.1021/ja0680257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ohulchanskyy TY, Roy I, Goswami LN, Chen Y, Bergey EJ, Pandey RK, et al. Organically modified silica nanoparticles with covalently incorporated photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy of cancer. Nano Lett. 2007;7:2835–2842. doi: 10.1021/nl0714637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang P, Steelant W, Kumar M, Scholfield M. Versatile photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy at infrared excitation. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4526–4527. doi: 10.1021/ja0700707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gary-Bobo M, Hocine O, Brevet D, Maynadier M, Raehm L, Richeter S, et al. Cancer therapy improvement with mesoporous silica nanoparticles combining targeting, drug delivery and PDT. Int J Pharm. 2012;423:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2011.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhu J, Wang H, Liao L, Zhao L, Zhou L, Yu M, et al. Small mesoporous silica nanoparticles as carriers for enhanced photodynamic therapy. Chemistry Asian J. 2011;6:2332–2338. doi: 10.1002/asia.201100064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.He X-x, Wang K, Tan W, Liu B, Lin X, He C, et al. Bioconjugated nanoparticles for DNA protection from cleavage. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:7168–7169. doi: 10.1021/ja034450d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Peng J, He X, Wang K, Tan W, Li H, Xing X, et al. An antisense oligonucleotide carrier based on amino silica nanoparticles for antisense inhibition of cancer cells. Nanomedicine. 2006;2:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Meng H, Liong M, Xia T, Li Z, Ji Z, Zink JI, et al. Engineered design of mesoporous silica nanoparticles to deliver doxorubicin and P-glycoprotein siRNA to overcome drug resistance in a cancer cell line. ACS nano. 2010;4:4539–4550. doi: 10.1021/nn100690m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chen AM, Zhang M, Wei D, Stueber D, Taratula O, Minko T, et al. Co-delivery of Doxorubicin and Bcl-2 siRNA by Mesoporous silica nanoparticles enhances the efficacy of chemotherapy in multidrug-resistant cancer cells. Small. 2009;5:2673–2677. doi: 10.1002/smll.200900621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mai WX, Meng H. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles: A multifunctional nano therapeutic system. Integr Biol. 2013;5:19–28. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20137b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang Q, Liu F, Nguyen KT, Ma X, Wang X, Xing B, et al. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer-targeted and controlled drug delivery. Adv Funct Mater. 2012;22:5144–5156. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Joshi R, Feldmann V, Koestner W, Detje C, Gottschalk S, Mayer HA, et al. Multifunctional silica nanoparticles for optical and magnetic resonance imaging. Biol Chem. 2013;394:125–135. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee N, Cho HR, Oh MH, Lee SH, Kim K, Kim BH, et al. Multifunctional Fe3O4/TaO(x) core/shell nanoparticles for simultaneous magnetic resonance imaging and X-ray computed tomography. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10309–10312. doi: 10.1021/ja3016582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Huang X, Zhang F, Wang H, Niu G, Choi KY, Swierczewska M, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-based cell engineering with multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for tumor delivery. Biomaterials. 2013;34:1772–1780. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Meng H, Mai WX, Zhang H, Xue M, Xia T, Lin S, et al. Codelivery of an optimal drug/siRNA combination using mesoporous silica nanoparticles To overcome drug resistance in breast cancer in vitro and in vivo. ACS nano. 2013;7:994–1005. doi: 10.1021/nn3044066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rosenholm JM, Sahlgren C, Linden M. Towards multifunctional, targeted drug delivery systems using mesoporous silica nanoparticles--opportunities & challenges. Nanoscale. 2010;2:1870–1883. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00156b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Benachour H, Seve A, Bastogne T, Frochot C, Vanderesse R, Jasniewski J, et al. Multifunctional peptide-conjugated hybrid silica nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy and MRI. Theranostics. 2012;2:889–904. doi: 10.7150/thno.4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mignot A, Truillet C, Lux F, Sancey L, Louis C, Denat F, et al. A Top-down synthesis route to ultrasmall multifunctional Gd-based silica nanoparticles for theranostic applications. Chemistry Asian J. 2013;19:6122–6136. doi: 10.1002/chem.201203003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]