Abstract

Context

Obese individuals have high aldosterone levels that may contribute to insulin resistance (IR) and endothelial dysfunction leading to obesity induced cardiovascular disease. We conducted a study to evaluate the effect of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonism on IR and endothelial function in obese individuals.

Design

This was a placebo-controlled, double blind, randomized, parallel-group study (NCT01406015).

Participants and Interventions

Thirty two non-diabetic, obese subjects (BMI 30 to 45 kg/m2) with no other medical problems were randomized to six weeks of treatment with spironolactone 50 mg daily or placebo. Insulin sensitivity index (ISI) was assessed by Matsuda method, endothelial function by flow mediated vasodilatation (FMD) of brachial artery and renal plasma perfusion by clearance of para-aminohippurate (PAH).

Results

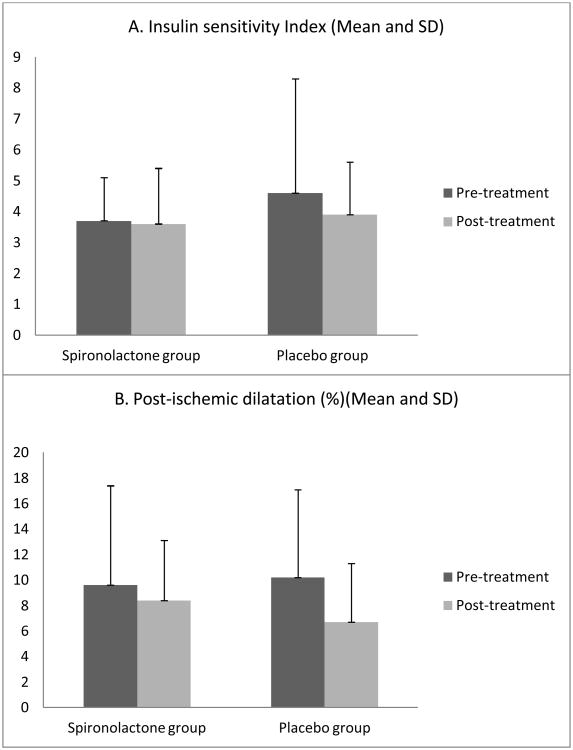

There was no change in weight, BMI or plasma potassium during the study period. Treatment with spironolactone led to increases in serum aldosterone (7.6±6.6 Vs 3.2±1.3 ng/dL; p <0.02, post-treatment Vs baseline) and urine aldosterone (11.0±7. Vs 4.8±2.4 µg/G creatinine; p<0.01) and decreases in systolic blood pressure (116±11 Vs 123±10 mmHg; p<0.001). There were no changes in these variables in the placebo group. Neither spironolactone nor placebo treatment had a significant effect on ISI or other indices of glucose metabolism (HOMA, area under the curve for insulin, area under the curve for glucose), brachial artery reactivity or the renal plasma perfusion values. Changes in these variables were similar in two groups.

Conclusions

We conclude that six weeks of treatment with spironolactone does not change insulin sensitivity or endothelial function in normotensive obese individuals with no other comorbidities.

Keywords: Mineralocorticoid Receptor, Obesity, Insulin Resistance, Endothelial Function

Introduction

Obesity is a public health problem with one third of all Americans being obese, half of whom also have metabolic syndrome [1, 2]. Studies have shown elevated aldosterone levels in obese individuals [3-5] and many investigators have proposed that increase in aldosterone and subsequent mineralocorticoid receptor (MR) activation underlies the increased cardiovascular disease risk in obesity [6, 7]. These hypotheses are supported by pre-clinical studies showing adverse effects of MR activation on insulin signaling, endothelial function, vascular injury, and cardiac and renal function [8-13]. In vitro studies demonstrate an adverse effect of aldosterone on insulin signaling mechanisms [9]. In animal studies, aldosterone promotes inflammation and vascular dysfunction, and blockade of the MR has beneficial effects on the vasculature and also improves insulin sensitivity [11, 14].

Human data are limited but MR blockade or adrenalectomy improves IR in patients with primary aldosteronism [15] and MR blockade has been shown to improve endothelial function in patients with heart failure [16]. These data raise the possibility that activation of the MR by aldosterone may contribute to the IR and vascular dysfunction in obese individuals. A recent perspective article suggested that MR antagonists (i.e., spironolactone, eplerenone) may have clinical benefits in obese and/or diabetic patients to prevent cardiovascular disease [7]. Therefore, we conducted a study to evaluate the effect of MR antagonist, spironolactone, on insulin sensitivity and endothelial function in obese individuals.

Methods

This was a placebo-controlled, double blind, randomized, parallel-group study (NCT01406015). We recruited subjects aged 18 to 60 years with BMI >30 kg/m2. Exclusion criteria included any medical illnesses other than treated hypothyroidism, blood pressure (BP) >135/85 or systolic BP <90 mm Hg, fasting plasma glucose >126 mg/dL, hepatic transaminases > 3 times upper limit of normal, eGFR <80 ml/min, serum K >5.0 mmol/L, history of drug or alcohol abuse, allergic reactions to spironolactone and participation in any other concurrent clinical trial. The study protocol was approved by Partners Health Human Research Committee and all participants provided written informed consent.

Subjects were placed on a standardized isocaloric diet including 2,500 ml fluid, 200 mEq Na, 100 mEq K, and 1000 mg Ca for 5 days before assessment studies. On the morning of day 5, subjects came to CCI after an overnight fast. A 24-hour urine collection was started for measurement of total volume, sodium, potassium, aldosterone and creatinine. An oral glucose tolerance test was conducted with 75 G glucose and blood samples were obtained every 30 minutes for 2 hours. On the next morning, after the subject had remained fasting and in the supine position since midnight, blood samples were obtained for potassium, sodium and aldosterone. Ultrasonography of the brachial artery was performed to evaluate endothelial function by flow mediated dilatation (FMD) studies using the technique previously described [16, 17]. Then, a loading dose of para-aminohippurate sodium (PAH) (8 mg/kg) (Merck, Sharpe and Dohme, West Point PA) was given intravenously followed by a 1 hour constant infusion of PAH at a rate of 12 mg/minute. Plasma samples were obtained at baseline and at 50, and 60 minutes. PAH clearance was calculated from the plasma levels and infusion rates as previously described [18].

Subjects were then randomly assigned in a double blind fashion to treatment with spironolactone 50 mg daily or placebo for 6 weeks. Plasma potassium was checked every 2 weeks for safety reasons. Procedures performed at the baseline were repeated after 6 weeks of treatment with spironolactone or placebo, after subjects ate the standardized diet for 5 days. The last dose of study drug was administered at 3:00 PM while in the hospital and all procedures, other than OGTT, were performed the next morning, 14-16 hours after last drug dose.

Statistical analysis

Insulin sensitivity index (ISI) was calculated by Matsuda and Defronzo's method [19]. All values are presented as means ± standard deviation of the means (SD). Paired t-tests were used to compare changes at 6 weeks versus the baseline within groups. Unpaired t-test was used to compare the change from baseline between MR antagonist versus the placebo group. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Our sample size calculation was based on a previous study that evaluated the effect of troglitazone on FMD in healthy obese subjects [17]. Based on data from that study, >80% power was expected for 30% improvement in FMD in this study. Moreover, with a baseline ISI of 3.7 ± 1.4 seen in this study, we should have been able to detect a 30% change in ISI with our study sample size of 16 in each group. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 15.0 statistical software.

Results

Of the 38 subjects who met inclusion/exclusion criteria and were randomized to treatment, six subjects, 3 in spironolactone group and 3 in placebo group, withdrew due to concerns regarding time commitment (n=4) and decisions to have elective knee (n=1) and foot (n=1) surgery. Thirty-two subjects (age 43.4 ± 12.3 years, BMI 36.8 ± 5.8 kg/m2, 31% male) completed the study. Subjects randomized to placebo group had characteristics similar to the spironolactone group (table 1). Plasma potassium was not influenced by drug treatment. All plasma potassium values were <5.0 mEq/L during the study and no subjects were withdrawn due to high potassium. There was no change in weight or BMI during the study period.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects randomized to spironolactone and placebo groups.

| MRA group | Placebo group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47 ± 11.6 | 40 ± 12.3 | NS |

| Gender (M:F) | 6:10 | 4:12 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 38 ± 6.6 | 36 ± 4.6 | NS |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 123 ± 10 | 119 ± 12 | NS |

| Diastolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | 71 ± 5 | 70 ± 8 | NS |

| Serum Na (meq/L) | 139 ± 1.1 | 138 ± 1.5 | NS |

| Serum K (meq/L) | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | NS |

| Serum Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 123 ± 61 | 77 ± 33 | NS |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 179 ± 27 | 174 ± 29 | NS |

| Serum HDL (mg/dL) | 106 ± 21 | 108 ± 25 | NS |

| Serum cLDL (mg/dL) | 48 ± 12 | 50 ± 17 | NS |

Spironolactone treatment significantly reduced systolic BP whereas placebo had little effect on BP (table 2). The average decrease in systolic BP was 7 ± 5 mm Hg with spironolactone versus 0 ± 7 mm Hg with placebo (p <0.001). Spironolactone, but not placebo, led to an increase in plasma and 24-hour urinary aldosterone as is anticipated from initiation of MR blockade (table 3). Further, post-treatment levels of plasma aldosterone were higher in the spironolactone group compared to the placebo group.

Table 2.

Effect of spironolactone or placebo on clinical and biochemical parameters.

| MRA (N=16) | Placebo (N=16) | Change from baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-treatment | P | Baseline | Post-treatment | P | MRA | Placebo | P | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 38 ± 6.6 | 38 ± 6.8 | NS | 36 ± 4.6 | 36 ± 4.7 | NS | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.3 ± 1.0 | NS |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 123 ± 10 | 116 ± 11 | 0.0001 | 119 ± 12 | 119 ± 8 | NS | -7 ± 5 | 0 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 71 ± 5 | 69 ± 7 | NS | 70 ± 8 | 71 ± 8 | NS | -3 ± 6 | 1 ± 7 | NS |

| Serum Na (meq/L) | 139 ± 1.1 | 138 ± 1.4 | 0.04 | 138 ± 1.5 | 138 ± 1.6 | NS | -0.94 ± 1.6 | 0.63 ± 1.7 | 0.01 |

| Serum K (meq/L) | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 | NS | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | NS | 0.11 ± 0.3 | 0.02 ± 0.3 | NS |

| Urine Na (meq/G creatinine) | 123.7 ± 57.3 | 124.8 ± 44.1 | NS | 100.7 ± 27.5 | 126.4 ± 38.4 | NS | 4.3 ± 46.3 | 21.9 ± 47.5 | NS |

| Serum Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 123 ± 61 | 123 ± 57 | NS | 76 ± 33 | 83 ± 39 | NS | -0.2 ± 33.9 | 6.8 ± 19.7 | NS |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 179 ± 27 | 179 ± 28 | NS | 174 ± 29 | 168 ± 23 | NS | 0.0 ± 11.5 | -5.3 ± 13.3 | NS |

| Serum HDL (mg/dL) | 48 ± 12 | 46 ± 11 | NS | 50 ± 17 | 49 ± 11 | NS | -3.0 ± 6.4 | -0.9 ± 7.6 | NS |

| Serum cLDL (mg/dL) | 106 ± 21 | 109 ± 21 | NS | 108 ± 25 | 102 ± 19 | NS | 3.1 ± 8.8 | -4.4 ± 12.5 | NS |

Data presented as Mean ± SD. SBP= systolic blood pressure, DBP=diastolic blood pressure

Table 3.

Effect of spironolactone or placebo on hormonal and vascular parameters.

| MRA (N=16) | Placebo (N=16) | Change from baseline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-treatment | P | Baseline | Post-treatment | P | MRA | Placebo | P | |

| Serum Aldosterone (ng/dL) | 3.2 ± 1.3 | 7.6 ± 6.6 | 0.02 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 3.7 ± 2.8* | NS | 4.4 ± 6.8 | 0.3 ± 3.2 | 0.04 |

| Urine aldosterone (mcg/G Creatinine) | 4.8 ± 2.4 | 11.0 ± 7.8 | 0.01 | 7.1 ± 3.7 | 7.4 ± 5.3* | NS | 6.0 ± 8.6 | -0.1 ± 4.9 | 0.03 |

| HOMA-IR | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 2.9 ± 1.4 | NS | 3.4 ± 3.2 | 3.3 ± 3.2 | NS | 0.1 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 4.4 | NS |

| ISI | 3.7 ± 1.4 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | NS | 4.6 ± 3.7 | 3.9 ± 1.7 | NS | -0.1 ± 0.8 | -1.1 ± 2.7 | NS |

| AUCgl (mg/dL × 180 min) | 16717 ± 4247 | 17602 ± 4160 | NS | 15649 ± 4155 | 15839 ± 4308 | NS | 885 ± 1629 | 261 ± 1567 | NS |

| AUCins (milli units/L × 180 min) | 7435 ± 3187 | 7878 ± 4151 | NS | 7471 ± 3803 | 8395 ± 3910 | NS | 443 ± 2911 | 1324 ± 4296 | NS |

| Brachial artery diameter (resting) (mm) | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | NS | 3.3 ± 0.5 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | NS | 0.1 ± 0.3 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | NS |

| Brachial artery diameter (post-ischemia) (mm) | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | NS | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | NS | 0.0 ± 0.4 | 0.0 ± 0.2 | NS |

| Brachial artery diameter (post-Nitroglycerine) (mm) | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | NS | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | NS | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.3 | NS |

| Post-ischemic dilatation (%) | 9.6 ± 7.8 | 8.4 ± 4.7 | NS | 10.2 ± 6.9 | 6.7 ± 4.6 | NS | -1.2 ± 6.1 | -2.0 ± 4.7 | NS |

| Post Nitroglycerine dilatation (%) | 17.1 ± 6.3 | 19.3 ± 8.8 | NS | 25.1 ± 8.8 | 19.0 ± 7.0 | NS | 0.89 ± 3.7 | -3.5 ± 8.9 | NS |

| PAH clearance (ml/min) | 488 ± 80 | 492 ± 75 | NS | 521 ± 116 | 506 ± 102 | NS | -2.3 ± 28.7 | -5.2 ± 25.3 | NS |

ISI=insulin sensitivity index, AUCgl = area under curve for glucose, AUCins=area under curve for insulin.

p<0.01 comparing with post-treatment MR antagonist.

Neither spironolactone nor placebo treatment had a significant effect on any indices of insulin resistance (Table 3). Specifically, neither treatment affected HOMA, area under the curve for insulin or glucose, or ISI (mean change with spironolactone -0.08 ± 0.79).

Results of the vascular studies are also shown in table 3. Neither the brachial artery reactivity nor the renal plasma perfusion values changed significantly in either treatment group.

Discussion

This study shows that treatment with an MR antagonist for 6 weeks significantly reduces BP in obese, otherwise healthy individuals, but does not affect IR or endothelial dysfunction. These results suggest that excess MR activation does not contribute to early obesity-induced changes in IR or endothelial dysfunction.

We observed the expected rise in aldosterone levels on treatment with MR antagonist and a decrease in systolic BP, suggesting good compliance with study drug. Our hypothesis that there is excess MR activation in obesity was based on both preclinical and clinical data. In humans, we previously showed that angiotensin II-stimulated aldosterone levels are increased in overweight versus lean individuals on a high sodium diet [3]. Since this study includes a similar but more obese population compared to the previous study, it would be expected to have increased baseline stimulated aldosterone. Further, MR can be activated by multiple factors other than circulating aldosterone [20, 21]. In our study population, the best evidence of baseline MR activation was reduction in BP after treatment with MRA. As our study design did not include a healthy lean comparison group, we cannot state that this decrease in BP was exaggerated.

We had anticipated that treatment with an MR antagonist would increase ISI in this obese, insulin resistant population. However, spironolactone did not affect IR, suggesting that despite prior reports of an association between aldosterone levels and IR [3], a cause and effect relationship is unlikely in this population of relatively healthy obese individuals. It is possible that the effects of increased aldosterone on IR are seen at higher levels of aldosterone and/or accrue over years. If so, this would explain why patients with primary aldosteronism show improvements in IR when treated with surgery or a MR antagonist [15]. Similarly the beneficial effects of MR blockade on the endothelial function observed in the Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study (RALES) study could be due to greater MR activation in patients with heart failure as compared to our healthy obese population [22]. It is an open question as to whether MR blockade would affect IR in obese individuals with primary hypertension and other cardiovascular comorbidities. Other investigators have suggested that excess MR activation impairs insulin release [23]. In our study spironolactone treatment did not affect the area under the curve for insulin, suggesting that this mechanism may not contribute to impaired glucose metabolism in this population. Preclinical studies have shown that aldosterone may induce insulin resistance through multiple potential mechanisms including excessive oxidative stress, proteosomal degradation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS), enhanced signaling through hybrid insulin/IGF-1 receptor and decreased expression of liver GLUT2 and skeletal muscle GLUT4 [7, 24]. The mechanisms may differ in different populations and this may be the reason for disparate results.

It is possible that ISI and FMD were normal at baseline and therefore, a further improvement would have been difficult to achieve. However, abnormal IR and impaired endothelial function are well described in insulin resistant obese population [17] and we think our subjects were representative of a typical obese population. Mean ISI was <5 in our subjects as compared to normative levels of 8-12 in healthy lean subjects in other studies, indicating that our subjects were insulin resistant [25]. While ISI correlates very well with euglycemic clamp studies, the gold standard for assessing IR, it is possible that ISI was not adequately sensitive for detecting a change in IR in this population [19]. Another possibility is that aldosterone exerts its effects on insulin signaling through a mechanism independent from the MR. However; if this possibility were true, one would assume that as aldosterone levels increase with MR blockade, IR would increase. This did not occur in our study. The possibility of increase in aldosterone counteracting the effect of spironolactone or the absence of MR activation at baseline in this population cannot be completely ruled out. Also, we cannot rule out the possibility of inadequate dose of spironolactone or relatively shorter duration of its use in our study. It is important to note that 6 weeks of spironolactone 50 mg daily did not lead to an impairment in glucose tolerance as has been suggested by some studies [26].

Our inability to see an effect of MR antagonist on FMD is consistent with a prior report in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes showing no effect [27]. Also, we did not see worsening of endothelial function, which is important as one study reported an adverse effect of spironolactone on endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [28]. Prior studies have shown that weight loss of 6.6% leads to parallel improvements in endothelial function and IR [29]. Similarly, insulin sensitizing drug therapy improves both endothelial function and IR [17]. The failure of improvement in FMD in this study is consistent with the lack of improvement in IR.

We conclude that six weeks of treatment with spironolactone 50 mg daily reduces systolic blood pressure, but does not change insulin sensitivity or endothelial function in normotensive obese individuals with IR and no other comorbidities.

Figure 1.

Effect of spironolactone and placebo on: A. insulin sensitivity index, B. Flow mediated vasodilatation of the brachial artery. The differences were not statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants K24 HL103845 (GKA) and UL1 RR025758 (Harvard Catalyst; The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center) and Brigham and Women's Hospital Center for Clinical Investigation.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The authors have no disclosures.

Conflict of interest details: Design: RG, GKA and GHW Conduct/data

collection: RG, GKA, LK

Analysis: RG, GKA

Writing Manuscript: RG, LK, GKA, GHW

Authorship details: None of the authors has a competing interest

Author contributions: RG conceived the idea, conducted the study, analyzed and interpreted data and wrote the manuscript; LK recruited study subjects and implemented the protocol; GHW helped in developing idea, interpretation of data and reviewed the manuscript; GKA helped in designing and conducting the study, analysis and interpretation of data and writing the manuscript.

References

- 1.http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html.

- 2.Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. Jama. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley-Lewis R, Adler GK, Perlstein T, et al. Body mass index predicts aldosterone production in normotensive adults on a high-salt diet. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4472–4475. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossi GP, Belfiore A, Bernini G, et al. Body mass index predicts plasma aldosterone concentrations in overweight-obese primary hypertensive patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2566–2571. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andronico G, Cottone S, Mangano MT, et al. Insulin, renin-aldosterone system and blood pressure in obese people. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:239–242. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg R, Adler GK. Role of mineralocorticoid receptor in insulin resistance. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2012;19:168–175. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283533955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bender SB, McGraw AP, Jaffe IZ, Sowers JR. Mineralocorticoid receptor-mediated vascular insulin resistance: an early contributor to diabetes-related vascular disease? Diabetes. 2013;62:313–319. doi: 10.2337/db12-0905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han SY, Kim CH, Kim HS, et al. Spironolactone prevents diabetic nephropathy through an anti-inflammatory mechanism in type 2 diabetic rats. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1362–1372. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005111196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wada T, Ohshima S, Fujisawa E, Koya D, Tsuneki H, Sasaoka T. Aldosterone inhibits insulin-induced glucose uptake by degradation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) 1 and IRS2 via a reactive oxygen species-mediated pathway in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1662–1669. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirata A, Maeda N, Hiuge A, et al. Blockade of mineralocorticoid receptor reverses adipocyte dysfunction and insulin resistance in obese mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:164–172. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo C, Ricchiuti V, Lian BQ, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor blockade reverses obesity-related changes in expression of adiponectin, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, and proinflammatory adipokines. Circulation. 2008;117:2253–2261. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuster GM, Kotlyar E, Rude MK, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor inhibition ameliorates the transition to myocardial failure and decreases oxidative stress and inflammation in mice with chronic pressure overload. Circulation. 2005;111:420–427. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153800.09920.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo C, Martinez-Vasquez D, Mendez GP, et al. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist reduces renal injury in rodent models of types 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinology. 2006;147:5363–5373. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada T, Kenmochi H, Miyashita Y, et al. Spironolactone improves glucose and lipid metabolism by ameliorating hepatic steatosis and inflammation and suppressing enhanced gluconeogenesis induced by high-fat and high-fructose diet. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2040–2049. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Catena C, Lapenna R, Baroselli S, et al. Insulin sensitivity in patients with primary aldosteronism: a follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3457–3463. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abiose AK, Mansoor GA, Barry M, Soucier R, Nair CK, Hager D. Effect of spironolactone on endothelial function in patients with congestive heart failure on conventional medical therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:1564–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg R, Kumbkarni Y, Aljada A, et al. Troglitazone reduces reactive oxygen species generation by leukocytes and lipid peroxidation and improves flow-mediated vasodilatation in obese subjects. Hypertension. 2000;36:430–435. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.3.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher ND, Price DA, Litchfield WR, Williams GH, Hollenberg NK. Renal response to captopril reflects state of local renin system in healthy humans. Kidney Int. 1999;56:635–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1462–1470. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pojoga LH, Baudrand R, Adler GK. Mineralocorticoid receptor throughout the vessel: a key to vascular dysfunction in obesity. Eur Heart J. 2013 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagase M, Fujita T. Role of Rac1-mineralocorticoid-receptor signalling in renal and cardiac disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013;9:86–98. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farquharson CA, Struthers AD. Spironolactone increases nitric oxide bioactivity, improves endothelial vasodilator dysfunction, and suppresses vascular angiotensin I/angiotensin II conversion in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:594–597. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luther JM, Luo P, Kreger MT, et al. Aldosterone decreases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in vivo in mice and in murine islets. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2152–2163. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tirosh A, Garg R, Adler GK. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2010;12:252–257. doi: 10.1007/s11906-010-0126-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radikova Z, Koska J, Huckova M, et al. Insulin sensitivity indices: a proposal of cut-off points for simple identification of insulin-resistant subjects. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006;114:249–256. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homma T, Fujisawa M, Arai K, Ishii M, Sada T, Ikeda M. Spironolactone, but not eplerenone, impairs glucose tolerance in a rat model of metabolic syndrome. J Vet Med Sci. 2012;74:1015–1022. doi: 10.1292/jvms.12-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joffe HV, Kwong RY, Gerhard-Herman MD, Rice C, Feldman K, Adler GK. Beneficial effects of eplerenone versus hydrochlorothiazide on coronary circulatory function in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2552–2558. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davies JI, Band M, Morris A, Struthers AD. Spironolactone impairs endothelial function and heart rate variability in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2004;47:1687–1694. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hamdy O, Ledbury S, Mullooly C, et al. Lifestyle modification improves endothelial function in obese subjects with the insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2119–2125. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]