Abstract

Cancer cells tend to utilize aerobic glycolysis even under normoxic conditions, commonly called the “Warburg Effect.” Aerobic glycolysis often directly correlates with malignancy, but its purpose, if any, in metastasis remains unclear. When wild-type KISS1 metastasis suppressor is expressed, aerobic glycolysis decreases and oxidative phosphorylation predominates. However, when KISS1 is missing the secretion signal peptide (ΔSS), invasion and metastasis are no longer suppressed and cells continue to metabolize using aerobic glycolysis. KISS1-expressing cells have 30–50% more mitochondrial mass than ΔSS-expressing cells, which is accompanied by correspondingly increased mitochondrial gene expression and higher expression of PGC1α, a master co-activator that regulates mitochondrial mass and metabolism. PGC1α-mediated downstream pathways (i.e. fatty acid synthesis and β-oxidation) are differentially regulated by KISS1, apparently reliant upon direct KISS1 interaction with NRF1, a major transcription factor involved in mitochondrial biogenesis. Since the downstream effects could be reversed using shRNA to KISS1 or PGC1α, these data appear to directly connect changes in mitochondria mass, cellular glucose metabolism and metastasis.

Introduction

Metabolic reprogramming of cells has long been appreciated to contribute to oncogenesis (1). First described by Otto Warburg in the 1920’s, cancer cells have increased conversion of glucose to lactic acid even under normoxic conditions (2–5). As cellular metabolic signaling and primary energy sensors, mitochondrial bioenergetic and, much less commonly, genetic abnormalities mediate tumor transformation and progression (3, 6–8). Likewise, tumor-associated gene expression and/or protein activities (e.g., TP53, MYC, RAS, SRC and HIF1α) drive metabolic sensing (9–11), mitochondrial cristae structure (10, 12–14), as well as glucose uptake, lactate accumulation and cytosolic pH acidification. Correspondingly, mutations in cancer patients for citric acid cycle enzymes (e.g., isocitrate dehydrogenase, fumarase and succinate dehydrogenase) have been described (15) as have mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) itself (16–18). Mutations in mitochondrial enzymes and mtDNA are relatively rare, i.e., of insufficient frequency to explain a majority of metabolic reprogramming observed in cancers. Yet, the molecular mechanisms underlying metabolic reprogramming remain elusive and the relationship (i.e., cause-effect vs correlation-only) to metastasis remain unclear. Two hypotheses are supported by experimental data: (i) mitochondria generate numerous reactive oxygen species (ROS) which cause oxidative stress and signal to drive cancer cell motility/invasion and tumor progression (16, 19, 20); and, (ii) redox potentials or NAD+/NADH ratio regulate metastatic potential (16, 20–23)

Despite well-established associations of aerobic glycolysis with tumor development, the relationships, if any, with metastasis development are much less clear. Given the enormous energy requirements of the metastatic cascade, the stresses cells experience throughout the process and the flexibility of the energy metabolism by glycolysis, it makes sense that some relationship would exist (24). Recent studies indicated that specifically reduced glucose oxidation enhances tumor metastasis (25), while other studies find or fail to identify correlations (18, 26). Generation of cybrids – cells which retain their nuclear genome but have mtDNA transferred from another source – shows that mitochondrial polymorphisms can dramatically influence metastatic potential (16, 18, 27). Yet, metabolic changes have not been systematically correlated with metastatic behaviors.

KISS1 is a member of the still-expanding family of metastasis suppressors, which are defined by their ability to block metastasis without preventing primary tumor development. Nascent KISS1 is a 145-amino acid polypeptide which is secreted and processed by prohormone convertases into kisspeptins (KP). KP54 ((aa68 - aa121) originally called metastin (28) but standardized nomenclature has recently been adopted (29)) was first identified as the ligand for a G-protein coupled receptor, KISS1R (also known as GPR54, AXOR12 or hOT7T175) (28, 30, 31). If the secretion signal peptide is removed (designated by ΔSS), the metastasis suppressing capacity of KISS1 is lost (32). KP54 can be further cleaved into smaller KP comprised of 13, 14 or 10 amino acid residues from the (typically amidated) C-terminal portion of KP54 (30). As long as the smaller KP retain the terminal RF–NH2 sequence, they can bind to and activate KISS1R. KISS1/KP54 activates a variety of signals, including phospholipase C (PLC), protein kinase C, intracellular Ca2+ mobilization, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathways (33). These observations led us to hypothesize that KISS1 secretion, processing and autocrine signaling through KISS1R were responsible for anti-metastatic effects. However, since none of the cell lines suppressed for metastasis when KISS1 is re-expressed express the KISS1R (32), the hypothesis was revised to implicate intracrine or paracrine signaling, or the existence of another KISS1 receptor (33).

To begin addressing these alternative hypotheses and whether there is a relationship between KISS1 metastasis suppression and metabolism, we performed bioenergetic and metabolic studies. Our results show, for the first time, that KISS1 expression increased extracellular pH by decreasing aerobic glycolysis, apparently via pathways that enhance mitochondrial respiration and/or biogenesis through regulating PPARγ co-activator-1 (PGC1α).

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture

The majority of experiments presented in this report were performed with a highly metastatic subclone of the human melanoma cell line C8161. Validation studies of key experiments were performed in MDA-MB-435 and MelJuSo. KFM (KISS1-FLAG-Metastin) or KFMΔSS were described previously (32) in C8161.9. Briefly, KFM and KFMΔSS insert the FLAG epitope within the proprotein convertase processing site (between R67 and X68) so that KISS1 protein and subsequent processing can be tracked. KFMΔSS removes the 19 amino acid secretion signal sequence. Initially, constructs were made in pcDNA3.1 phagemid, but lentiviral constructs have been generated using the Life Technologies Gateway® platform. Metastasis suppression was equivalent (Figure 1A). All cells were cultured as previously described in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco’s-modified minimum essential medium and Ham’s F-12 medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA or Sigma, St. Louis, MO), non-essential amino acids and glutamine. For cells expressing exogenous cDNA or shRNA, G418 (500 mM) or puromycin (5 μg/mL) were added. All cell lines were tested using a PCR-based assay and found to be free of Mycoplasma spp. contamination.

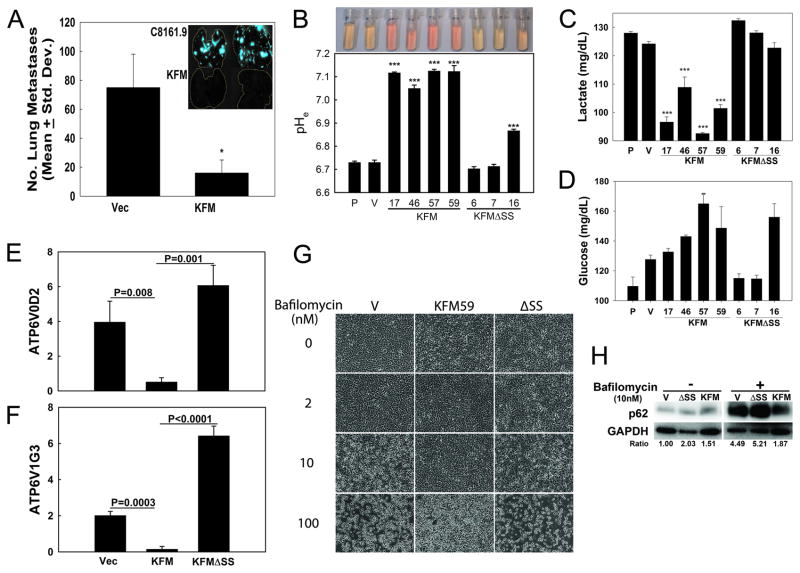

Figure 1. KISS1 down-regulates extracellular acidification.

A, KISS1 re-expression in C8161.9 cells (200,000) suppresses metastasis to lung following intravenous injection into NOD-SCID female mice (n=5). Inset shows GFP-labeled tumor cells in lung 6 wk after inoculation (* = p<0.05). B, Extracellular pH (pHe) is significantly higher in KFM-expressing cells, but not in most KFMΔSS-expressing clones of C8161.9. Image shows cell culture medium collected from equal-density cultures with corresponding pH measurement below. (*** = P<0.001, n = 5). C, lactate secretion and glucose utilization (D, measured by glucose remaining in cell culture medium) by C8161.9 (P), C8161.9Vector (V), C8161.9KFM, and C8161.9ΔSS cell clones were measured (and normalized by cell number). E, F, Expression of V-ATPase V0D2 and V1G3 subunit transcripts in C8161.9Vector (Vec), C8161.9KFM, and C8161.9ΔSS cell clones were examined by RT-qPCR. G, KISS1 protects C8161.9Vector (V), C8161.9KFM, and C8161.9ΔSS cell clones from cytoxicity following treatment with Bafilomycin (0–100 nM), an inhibitor of V-ATPase. H, Immunoblot showing accumulation of p62 in bafilomycin-treated (10 nM) parental and KFMΔSS-expressing, but not KFM-expressing C8161.9 cells, suggesting autophagy inhibition. Densitometry of p62 normalized to GAPDH is shown. Bars = mean ± S.E.M. I, Quantification of cell viability when cells are treated with bafilomycin. Open bars = no bafilomycin; filled bar = bafilomycin-treated (10 nM). ***, p<0.05.

Glucose uptake and lactate production

Cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 cells per well. Culture media was collected at 48 hr and stored at −20°C until assayed. Glucose uptake was measured using the Quantichrom Glucose Assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA). Absorbance (630 nm) was measured a using Synergy H4 Hybrid Multi-mode microplate reader (Biotek, Winoosky, VT) and normalized to total protein. Lactate production in the medium was detected by using Enzychrom L-Lactate Assay kit. Results were normalized to total protein.

Real-time RT-PCR and Mitochondria PCR-Array

To measure gene expression, total RNA was isolated and mRNA was reverse-transcribed. Resulting cDNA was then amplified using TaqMan® or SYBR Green probes (Primer/probe information in Supplemental Table 1). To simultaneously analyze mitochondria associated gene expression, RNA was extracted and genomic DNA was eliminated by DNase treatment followed by PCR-Array Procedure. Human mitochondria RT2 profiler PCR Array and RT2 Real-Timer SyBR Green/ROX PCR Mix were purchased from SuperArray Bioscience (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). PCR was performed on ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA).

Mitochondrial function

To measure mitochondrial function, a Seahorse Bioscience (North Billerica, MA) XF24 extracellular flux analyzer was used (34, 35). The rates of oxygen consumption and extracellular acidification rate were expressed in pmol/min and mpH/min, respectively, and normalized by total amount of protein of cells. The mitochondrial toxins oligomycin, carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy) phenylhydrazone (FCCP) and antimycin A were to disrupt mitochondrial function were purchased from Sigma.

Antibodies, immunoprecipitation and immunoblot

For co-IP experiments, cells were lysed in ice-cold lysis buffer (45 min, Pierce, Thermo Scientific, Lenexa, KS) and centrifuged (12,000 × g; 15 min; Beckman-Coulter Microfuge 22R Centrifuge, Brea, CA). The supernatant was incubated with monoclonal antibody followed by precipitation with protein G-sepharose beads. The beads were precipitated by centrifugation and thoroughly washed three times. Proteins bound to beads were released and analyzed by immunoblotting. For immunoblots, cell lysates were boiled (10 min), resolved using SDS-PAGE using 4–20% precast polyacrylamide gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Antibodies were purchased from the following manufacturers and were used at the titre listed: PGC1α (1:500; Merck, White House Station, NJ), NRF1 (1:500; Santa Cruz), GAPDH (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Danvers MA) and KISS1 (32)(1:500). Membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and bands were visualized using SuperSignal West Femto Substrate (Thermo Scientific).

Yeast two-hybrid protein interactions

Full-length KISS1 was used as bait in a yeast two-hybrid screen with placenta and normal breast libraries as prey (Hybrigenics, Paris, France).

Invasion and migration

Invasion was measured using Matrigel-coated transwell chambers (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) as previously described (32), except that tumor cells were tracked using CellTracker Green CMFDA (Life Technologies). Migration was measured using a wound healing or scratch assay as previously described (32).

Anchorage-independent growth

Anchorage-independent growth was assessed by monitoring colony formation after 14–21 days in soft agar (0.8% base; 0.4% upper layer) using 5000 cells/well in 6-well plates. First, 0.6% agarose (2 mL) in growth medium was added to a 6-well plate and allowed to solidify. Then, cells were suspended in 2 mL of 0.3% agar were added on top of the agar base and allowed to solidify. Colonies (>50 cells) were stained with crystal violet and counted using a phase contrast microscope.

Statistical analyses

Experiments were done using a minimum of three replicates for each experimental group. Representative data from at least two replicate experiments are depicted. However, some experiments with cell lines other than C8161.9 were performed only once. For all statistical analysis, Sigmastat, Sigmaplot or Prism software were used. Results are reported as mean ± S.D. (or mean ± S.E.). Statistical significance was determined by a two-sided Student’s test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test. Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Results

KISS1 expression inhibits extracellular acidification

Compared to normal tissues, the extracellular space of most tumors is acidic because production of excess lactic acid occurs during aerobic glycolysis. Growing evidence suggests that tumor acidity correlates with cancer proliferation, invasion, metastasis and chemoresistance (36, 37). Cultured metastatic C8161.9 cells and C8161 expressing KFMΔSS (C8161.9ΔSS) cells exhibit typical acidic pH[Ex] (range = 6.7–6.9). In contrast, medium collected from cultures of non-metastatic C8161.9 cells stably expressing KFM (C8161.9KFM) maintain a neutral pH (pH[Ex] = 7.2–7.4) (Figure 1B). Similar pH normalization following KISS1 re-expression, but not KISS1ΔSS, was observed in MDA-MB-435 and MelJuSo cell lines as well (Supplemental Figure 1 and Figure 6). Since production of lactate corresponds to high rates of glycolysis, lactate secretion and glucose uptake were measured (Figures 1C and 1D, respectively). We further examined whether KISS1 affects enzymes in the glycolytic pathway. Transcripts of hexokinase II (HKII) was significantly decreased in C8161KFM and C8161KFMΔSS cells compared to vector-only cells, while glucose transporter GLUT1 was significantly increased. In contrast, phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1) and LDHB genes were up-regulated in C8161.9KFM cells, but not C8161.9KFMΔSS cells (Supplemental Figure 1). However, expression of glycolytic enzymes were not consistently observed in MelJuSo melanoma cells. Therefore, KISS1-mediated metabolic changes should be ascribed elsewhere. KISS1-expressing cell clones showed lower glucose uptake and lactate secretion.

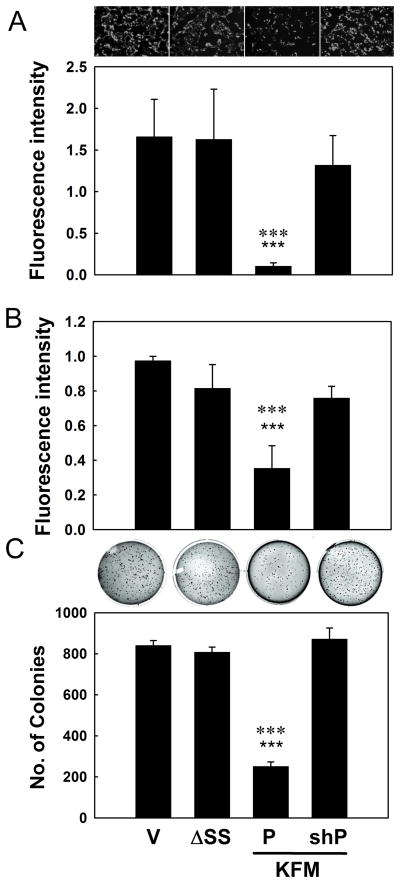

Figure 6. PGC1α is essential for KISS1 metastasis suppression.

A, C8161.9Vector (V), C8161.9ΔSS C8161.9KFM (P) and C8161.9KFM/shPGC1α (KFM- (SHK) and shRNA to PGC1α (SHP) co-transfected) cell clones are evaluated for transwell invasion (A) and migration using a scratch assay (B) and anchorage-independent growth in soft agar (C). Representative images for invading cells and colonies in soft agar are shown. Bars = mean ± S.E.M., n=3, ★★★ (three stars), P<0.001 compared to Vector or KFMΔSS; ✱✱✱ (three asterisks), P<0.001 compared to shRNA to PGC1α (shP).

Lactate is not the sole contributor to acidic microenvironments (37, 38). Plasma membrane vacuolar proton-ATPase (V-ATPase) also promotes extracellular acidification as well as increased invasion, survival and metastasis (39–41). A comprehensive analysis of v-ATPase subunit expression by RT-qPCR revealed that expression of the V0d2 and V1g3 isoform transcripts were significantly decreased in C8161.9KFM cells compared to parental of KFMΔSS-expressing tumor cells (C8161.9 or C8161.9ΔSS shown in Figures 1E and 1F, respectively). If conditioned medium from KFM, but not parental or KFMΔSS cell cultures, were put onto vector-only transfected C8161.9 cells, both V-ATPase transcripts were also reduced (Supplemental Figure 2A). Bafilomycin, an inhibitor of v-ATPase, induced cell death in C8161.9 and C8161.9ΔSS cells, while C8161.9KFM cells were resistant at equivalent doses (Figures 1G and 1I). Because Bafilomycin is also an inhibitor of autophagy, we speculated that C8161.9KFM cells should be resistant to Bafilomycin-induced autophagy inhibition (i.e., undergo apoptosis in response to stress). KISS1 showed substantially lower p62 accumulation (i.e., deficient for autophagy) (Figure 1H). Moreover, significant up-regulation of apoptotic genes (BNIP3 and ATG6) and glycolytic pathway factors (GLUT1, HKII, PFK1) were observed in vector- and KFMΔSS-, but not KFM-expressing cells (Supplemental Figure 2B). Taken together, these data strongly indicate that KISS1-expressing cells are less V-ATPase active and, therefore, may have a deficiency in autophagy compared to vector- and KFMΔSS-expressing cells.

KISS1 induces mitochondrial biogenesis and activation

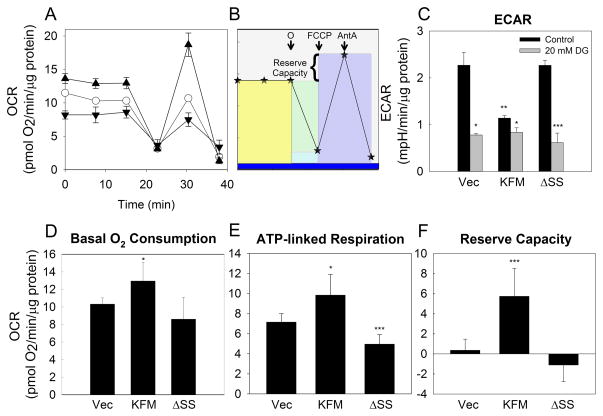

Reduced acidification in KISS1-expressing cells suggested that they might have shifted from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation. A Seahorse Bioscience XF24 was used to examine multiple mitochondrial function parameters after sequential injection of oligomycin (ATP synthase inhibitor), FCCP (uncoupling agent), and Antimycin A (Complex III inhibitor) (Figures 2A and 2B) (35). These parameters include oxygen consumption rate (OCR), ATP-linked respiration and the reserve respiratory capacity (Figures 2A and 2B).

Figure 2. KISS1 enhances mitochondria respiratory capabilities.

Measurement of mitochondrial function in C8161.9Vector, C8161.9KFM, and C8161.9ΔSS cells using the XF24 bioanalyzer. A, Measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR) under the basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin (O), FCCP and antimycin A as depicted schematically in Panel B. Symbols = ○ (open circle), Vector; ▲ (closed up triangle), KFM; ▼ (closed down triangle), KFMΔSS. Colored blocks in Panel B represent basal oxygen consumption (yellow); ATP-linked respiration (green); maximal oxygen consumption (purple), proton leak (light blue) and other respiration (dark blue). Reserve capacity is the difference between maximal ATP-linked respiration and maximal oxygen consumption. C, Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) measured contemporaneously with OCR measurements in the absence (black bars) or presence (gray bars) of 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG; 20 mM). D, Basal oxygen consumption; E, ATP-linked respiration; and F, reserve capacity derived from OCR measurements in Panel A. N=6–8; Error bars = SEM; *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001.

Consistent with lactate measurements, ECAR (Figure 2C) was significantly lower in C8161.9KFM cells compared to C8161.9vector and C8161.9ΔSS, while C8161.9KFM cells exhibited significantly higher basal oxygen consumption, ATP-linked respiration and reserve capacity (Figures 2D–F). Together, these results confirmed that KISS1-expressing cells shifted from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation and enhanced bioenergetic capacity. These changes may have resulted from either improved functionality of existing mitochondria or enhanced mitochondrial function resulting from increased total mitochondrial mass in the KISS1-expressing cells (i.e., the per mitochondrion functionality is the same, but total oxidative phosphorylation per cell would be higher).

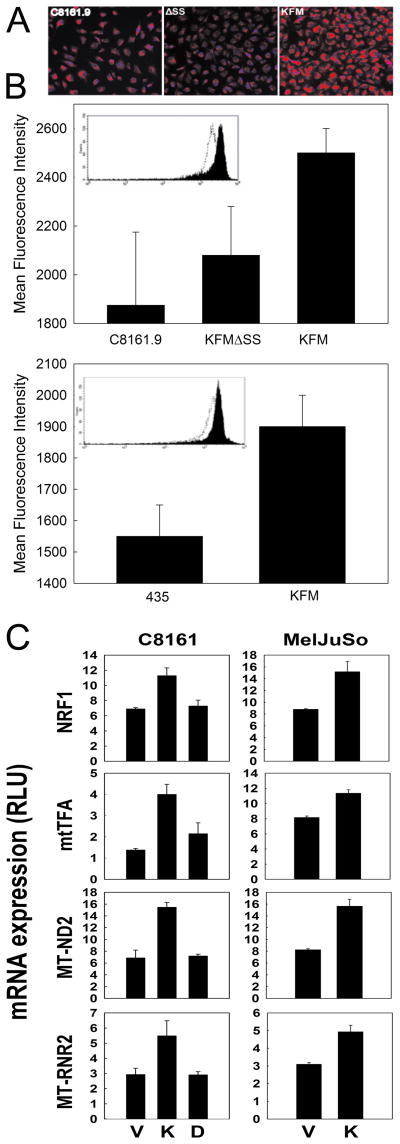

To assess a change in mitochondrial mass, C8161.9 and MDA-MB-435 cells were stained with MitoTracker dyes and quantified by immunofluorescence (Figure 3A and 3B) and flow cytometry (Figure 3B insets). KISS1-expressing cells consistently had significantly greater mitochondrial mass than non-expressing of KFMΔSS-expressing cells. Consistent with the MitoTracker staining results, expression of genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis and function – measured using a mitochondrial PCR array (Supplemental Figure 3) – were mostly higher (Figure 3C). In KISS1-expressing cells, various mitochondria genes encoded by the nuclear genome [apoptotic protein (AIFM2), chaperone proteins (HSP60 and HSP90AA1), membrane polarization and potential proteins (Ucp4 and Ucp5), import proteins (TIMM8A, TIMM8B, IMMP1L, MIPEP and LRPPRC) and small molecule transport and import/fission proteins (TSPO, SLC25A12, SLC25A20, SLC25A23, MFRN, ANT1 and ANT2)] were consistently more highly expressed. Furthermore, re-expression of KISS1 markedly induced expression of two key transcription factors in C8161 and MelJuSo cells, mitochondrial nuclear respiratory factors (NRF1) and mitochondrial transcription factor A (Tfam), corresponding to higher expression of mitochondria genome-encoded genes (Figure 3C). Collectively, these data suggest that KISS1 promotes a coordinate metabolic shift, stimulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and increased mitochondrial function.

Figure 3. KISS1 enhances mitochondrial biogenesis.

A, MitoTracker staining of C8161 and MDA-MB-435 cancer cells shows that KISS1- (KFM), but not KFMΔSS-expressing cell clones, have higher mitochondrial mass than parental cells, which was validated and further quantified by flow cytometry (B). Actual flow cytometric plots are shown in the insets. C, KISS1, but not KFMΔSS, expression increases transcript levels of mitochondrial biogenesis-associated genes (NRF1, mtTFA) and mitochondrial genes (MT-ND2, MT-RNR2) in C8161 and MelJuSo cell lines. Abbreviations used: C8161.9Vector (V), C8161.9KFM (K), C8161.9KFMΔSS (D). Bars = mean ± S.E.M., n = 3–5.

KISS1 promotes PGC1α expression and differentially regulates downstream metabolism factors

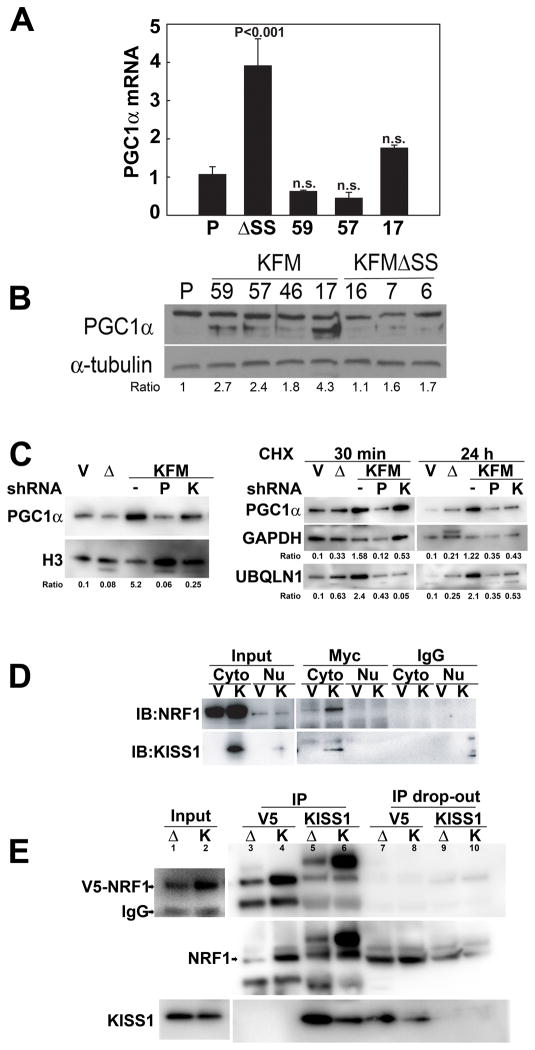

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator 1-α (PGC1α) is a transcriptional co-activator for many of the genes responsible for the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis and function (42). PGC1α interacts with NRF1 and activates transcription of Tfam, which then activates transcription and replication of the mitochondrial genome (43). Therefore, we explored whether PGC1α is involved in KISS1-mediated metabolic changes. KISS1 did not affect PGC1α mRNA expression (Figure 4A), but greatly increased steady state PGC1α protein expression (Figure 4B). Introduction of shRNA for KISS1 attenuated PGC1α protein expression in nuclei (Figure 4C, left panel), further leading to the conclusion that there is a direct link between KISS1 and PGC1α expression.

Figure 4. KISS1 up-regulates PGC1α expression and differentially regulates PGC1α downstream signals.

A, KISS1 does not increase PGC1α mRNA as detected by RT-qPCR; however, PGC1α protein (B, immunoblot, lower band) is consistently higher in KISS1-expressing, but not KFMΔSS-expressing C8161-derived cell clones. C, left panel, Treatment of KISS1-expressing (KFM) cells with shRNA to KISS1 reduces PGC1α in the nucleus of C8161 cell clones. C, right panel, C8161.9Vector (V), C8161.9ΔSS (Δ), C8161.9KFM, C8161.9KFM/shKiss1 (K) and C8161.9KFM/shPGC1α (P) cells were treated with cycloheximide for 30 min and 24 hr followed by immunoblotting to examine the expression of PGC1α and ubiquilin 1 (Ubql1). D, MelJuSo (V) and MelJuSoKFM (K) cells were transfected with Myc-tagged NRF1 plasmid. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated using anti-Myc antibody or control IgG, followed by immunoblotting with anti-NRF1 or anti-KISS1 antibodies. Data show that KISS1 interacts with NRF1 in the cytoplasm and is validated in reciprocal immunoprecipitation studies. E, Following transduction with V5-tagged NRF1 cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated using anti-V5 or anti-KISS1 antibodies followed by immunoblotting with anti-NRF1 or anti-KISS1 antibodies. Data show that KISS1 interacts with NRF1, but KFMΔSS, does not.

To assess whether KISS1 affects stability of PGC1α protein, cells were treated with cycloheximide to prevent protein synthesis. Figure 4C (right panel) shows that PGC1α levels quickly dropped in C8161.9 and C8161.9ΔSS, but no reduction was observed in C8161.9KFM cells, suggesting that KISS1 somehow stabilized PGC1α expression at a post-translational level.

Since PGC1α regulates multiple aspects of energy metabolism including mitochondria biogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, fatty acid synthesis, glucose utilization and antioxidant detoxification, KISS1 alterations of PGC1α downstream signals was measured (Supplemental Figure 4). KISS1 down-regulated expression of PPARα (fatty acid oxidation), but up-regulated ACC and FASN (fatty acid synthesis). Knockdown of KISS1 using shRNA blocked KISS1 induced changes of these genes. These intriguing results suggest that KISS1 differentially (i.e., not ubiquitously) regulates cellular metabolism through its regulation of PGC1α.

In initially unrelated experiments searching for KISS1-interacting proteins, one of the highest probability interacting proteins (i.e., relative binding strength and frequency of interaction in breast and placental libraries) was a molecular chaperone protein, ubiquitin-like protein (PLIC-1 or Ubiquilin-1). Ubiquilin-1 reportedly binds ubiquitylated proteins and ubiquitin ligases to interfere with the process of proteasome-dependent degradation (44). Figure 4C (right panel) shows that Ubiquilin-1 expression was as stable as PGC1α in C8161.9KFM cells, raising the possibility that KISS1 protects PGC1α from degradation by interacting with Ubiquilin-1.

NRF1 was identified in the yeast two-hybrid screens as another strongly interacting KISS1-interacting protein. Using Myc-tagged NRF1, the interaction was validated using anti-Myc antibodies in transiently transfected MelJuSo cells co-expressing KISS1 (Figure 4D). In a separate experiment, stably expressed V5-NRF1 in C8161.9KFM and C8161.9ΔSS cells was co-immunoprecipitated (Figure 4E). Although C8161.9ΔSS shows some interaction with V5-NRF, much more NRF1 associated with KISS1 in C8161.9KFM cells.

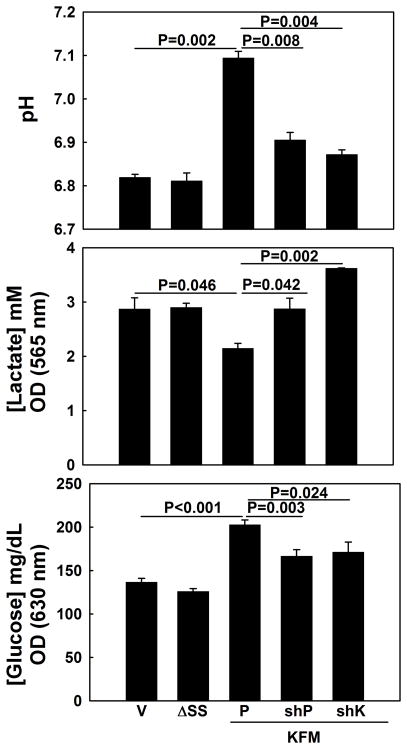

PGC1α is essential for KISS1-mediated metabolism changes and suppression of invasion

To investigate whether higher expression of PGC1α in KISS1-expressing cells was relevant to KISS1-mediated metabolism changes and/or metastasis suppression, shRNA was used to diminish PGC1α expression in C8161.9KFM cells. As predicted, knock-down of PGC1α resulted in extracellular acidification, increased glucose uptake and enhanced lactate secretion in cultured C8161.9KFM cells (Figures 5 and Supplemental Figure 7A). mtTFA and other mitochondrial genes were concomitantly down-regulated in C8161.9KFM cells after knocking-down PGC1α expression (Supplemental Figure 5).

Figure 5. PGC1α is essential for KISS1-mediated metabolism changes.

KISS1 effects on pH, lactic acid production and glucose uptake are reversed when KISS1 or PGC1α are knocked down using shRNA (shK and shP, respectively). Representative data are shown, but data are equivalent using other shRNA from Open Biosystems. Bars = mean ± S.E.M., n=3. P-values calculated using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-test.

The in vitro metabolic associations prompted examination of whether PGC1α is also involved as a downstream signal of KISS1 in metastasis suppression. KISS1 reduced invasion (Figure 6A and Supplemental Figure 6A), migration (Figure 6B and Supplemental Figure 6B) and anchorage-independent growth (Figure 6C); and, knock-down of PGC1α gene restored each phenotype.

Discussion

The glycolytic phenotype that persists in most primary and some metastatic cancers, even during normoxic conditions, would appear to provide a strong selective growth advantage. Despite many hypotheses to explain cancer cell predilection toward aerobic glycolysis (6, 45), the underlying mechanisms are still being uncovered as debates concerning the selective advantages of the Warburg Effect continue (46–48). We report here that the KISS1 metastasis suppressor inhibits aerobic glycolysis and increases oxidative phosphorylation, strongly suggesting that aerobic glycolysis is not required for primary tumor growth, but that it may contribute to successful metastasis.

The effects of KISS1 on glucose metabolism and microenvironment acidification provide plausible explanations for differences in metastasis between cell clones in a tumor. Acidosis can be mutagenic as it can inhibit DNA repair (49), which, in turn, could promote mutations that lead to metastatic competency. Lowering extracellular pH can impede cell-cell communication through gap-junctions (50), possibly altering cellular reception of growth regulatory signals. Extracellular pH also regulates activation, secretion and cellular distribution of many proteases (51–53), some of which are involved in breakdown of the extracellular matrix and invasion. All of these consequences of metabolic shifts could affect metastasis development.

Beyond enhanced glycolysis, there are additional mechanisms that can lead to extracellular acidification. Proton pumps, such as the vacuolar H+-ATPases (v-ATPase) which are ubiquitous multi-subunit ATP-dependent proton pumps found within plasma membrane, endosomal, lysosomal and Golgi-derived cellular membranes (54–56), contribute to membrane potentials and microenvironment pH. Plasma membrane-associated v-ATPase has been implicated in metastatic tumor cells (39–41). In addition to the metabolic changes occurring when KISS1 is re-expressed, we found that KISS1 appears to regulate v-ATPase expression, leading to the notion that manipulation of the microenvironment might be the underlying mechanism by which KISS1 allows growth at orthotopic sites while not allowing it at ectopic (metastatic) sites.

The most surprising and most profound observations reported here relate to KISS1 expression boosting mitochondrial biogenesis via modulation of PGC1α expression. Importantly, PGC1α seems to be essential for KISS1-mediated metabolic changes and invasion/metastasis suppression; that is, there appears to be a KISS1-PGC1α pathway involved in controlling malignant behavior. Roles for PGC1α in cancer are not unprecedented. Consistent with our findings, recent studies show that PGC1α expression is reduced in tumors compared to matching normal tissues (57–61). Moreover, PGC1α expression is inversely correlated with survival in breast cancer (62).

That PGC1α interacts with so many members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of orphan and ligand-activated transcription factors belies its versatility in controlling diverse biological programs involved in metabolism. One of the primary functions of PGC1α is to regulate energy metabolism by increasing oxidative metabolism, particularly mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by inducing expression of most genes in the citric acid cycle and electron transport chain (43). Mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration are, as a result, stimulated by PGC1α through powerful induction of the transcription factors NRFs and mtTFA (63). Thus, the mitochondrial biogenesis associated with KISS1 expression is probably through up-regulation of NRF1 and mtTFA.

PGC1α also regulates anabolic metabolism, which addresses one of the presumed benefits of cellular adoption of aerobic glycolysis – a shift toward macromolecular synthesis rather than efficiency of nutrient-to-energy conversion. For example, under nutrient-rich conditions, PGC1α promotes de novo fatty acid synthesis by co-activating the lipogenic transcription factor SREBP1 (64, 65). Under conditions of nutrient deprivation, PGC1α promotes β-oxidation by co-activating the liver X receptor (LXR) (64, 66, 67). When KISS1 was re-expressed, PGC1α downstream genes involved in β-oxidation (PPARα) were down-regulated while genes involved in lipogenesis (FASN, ACC1) were up-regulated. KISS1 re-expression also inhibited activation of AMPK (Supplemental Figure 7B), a major regulator in cellular energy homeostasis and autophagy. In highly proliferating metastatic cancers (of which all of the parental cell lines used in this report represent), cells at the core of the tumor have limited access to ATP and oxygen which are essential for growth and survival. These conditions would lead to up-regulation of glycolysis, inhibition of mitochondrial ATP synthesis and AMPK activation which, in turn, inactivates ACC1/2 to maintain NADPH levels. β-oxidation serves as an alternative survival pathway and several reports show that inhibition of mitochondrial β-oxidation compromises tumor cell survival (68–71). Collectively, these changes would enable cells to generate significant amounts of energy and promote cell survival during energy stress conditions.

On the other hand, we found that KISS1 cells have decreased V-ATPase expression. Preliminary studies suggest that KISS1 may prevent the assembly of V0 and V1 domains (data not shown). As a result, KISS1 cells have massively attenuated v-ATPase activity (which is required for the final step of autophagy, the breakdown of cargo delivered to the vacuole). Reduced autophagy in KISS1 cells was confirmed by increased p62 protein. Recent work has shown that p62 controls cell survival, autophagy and apoptosis. Moreover, modulation of p62 by autophagy is a key factor in tumorigenesis. Although these data suggest a connection between KISS1, metabolic regulation via autophagy, apoptosis and survival, more extensive studies are needed to firm up the associations.

Our findings establish a novel and unanticipated connection between the metastasis suppressor KISS1 and tumor metabolism. KISS1 regulation is multifaceted, affecting glycolysis, mitochondrial biogenesis and lipid homeostasis. These metabolic changes appear to center around KISS1 regulation of PGC1α protein levels, which begins to explain the paradoxical observation that the metabolism effects are observed in cells which do not express the KISS1 receptor (32) and that KISS1 mutants that are not secreted do not elicit a metabolic shift. Hints regarding a molecular mechanism of action are found in the direct binding of KISS1 and ubiquilin-1 and NRF1. Interactions between KISS1 and ubiquilin suggest that the presence of KISS1 reduces PGC1α protein degradation which, in turn, results in overall higher PGC1α expression. Thus far, however, we have not been able to identify a differential interaction with the KFMΔSS mutant that would fully explain the results. On the other hand, wild-type KISS1, but not the ΔSS mutant, interacts with NRF1. This is consistent with the observation that enhanced mitochondria biogenesis was only found in wild-type KISS1-expressing cells.

Ultimately, the findings suggest that some therapies that normalize metabolism may be particularly beneficial in controlling metastasis. Of course, this remains to be seen. This report establishes, for the first, time a direct relationship between metastasis suppression and metabolism. Emerging data using other models find similar trends, even though the mechanisms leading to normalized metabolism and metastasis suppression are not directly overlapping. Given the cross-talk between proliferation, survival and metabolic pathways and the perturbations that have been previously described in each of those pathways as relating to malignant behavior compel a more systematic and comprehensive examination of the interrelationships, particularly in the context of metastasis control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful for the direct financial support for this project from the following: U.S. National Cancer Institute RO1-CA134981 (DRW), Susan G. Komen for the Cure SAC11037 (DRW), National Foundation for Cancer Research-Center for Metastasis Research (DRW) and partial support from the Kansas Bioscience Authority (DRW), RO1-CA87728 (DRW), P30-CA168524 (DRW), T32-HL007918 (ARD), R01-CA151727 (AD) and the American Cancer Society RSG-09-169-01-CS (TI). DRW is the Hall Family Professor of Molecular Medicine and is a Kansas Bioscience Authority Eminent Scholar. The authors gratefully acknowledge the helpful technical support from Xuemei Cao and John W. Thomas, and advice and consultation from Drs. Douglas R. Hurst and Andra R. Frost and the University of Kansas Cancer Center Biostatistics Shared Resource.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–14. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O, Wind F, Negelein E. The metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 1927;8:519–30. doi: 10.1085/jgp.8.6.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biswas S, Lunec J, Bartlett K. Non-glucose metabolism in cancer cells--is it all in the fat? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:689–98. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9384-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaelin WG, Thompson CB. Q&A: Cancer: Clues from cell metabolism. Nature. 2010;465:562–4. doi: 10.1038/465562a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayevsky A. Mitochondrial function and energy metabolism in cancer cells: past overview and future perspectives. Mitochondrion. 2009;9:165–79. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Modica-Napolitano JS, Kulawiec M, Singh KK. Mitochondria and human cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:121–31. doi: 10.2174/156652407779940495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nature Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dang CV. c-Myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Molec Cell Biol. 1999;19:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Semenza GL. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Semin Cancer Biol. 2009;19:12–6. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez-Rios F, Sanchez-Arago M, García-García E, Ortega AD, Berrendero JR, Pozo-Rodríguez F, et al. Loss of the mitochondrial bioenergetic capacity underlies the glucose avidity of carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9013–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiche J, Rouleau M, Gounon P, Brahimi-Horn MC, Pouyssegur J, Mazure NM. Hypoxic enlarged mitochondria protect cancer cells from apoptotic stimuli. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222:648–57. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen PL. Tumor mitochondria and the bioenergetics of cancer cells. Prog Exp Tumor Res. 1978;22:190–274. doi: 10.1159/000401202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson CB. Metabolic enzymes as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:813–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0810213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ishikawa K, Takenaga K, Akimoto M, Koshikawa N, Yamaguchi A, Imanishi H, et al. ROS-generating mitochondrial DNA mutations can regulate tumor cell metastasis. Science. 2008;320:661–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1156906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koshikawa N, Hayashi J, Nakagawara A, Takenaga K. Reactive oxygen species-generating mitochondrial DNA mutation up-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha gene transcription via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt/protein kinase C/histone deacetylase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33185–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa K, Hashizume O, Koshikawa N, Fukuda S, Nakada K, Takenaga K, et al. Enhanced glycolysis induced by mtDNA mutations does not regulate metastasis. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:3525–30. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen EI. Mitochondrial dysfunction and cancer metastasis. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2012;44:619–22. doi: 10.1007/s10863-012-9465-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pani G, Giannoni E, Galeotti T, Chiarugi P. Redox-based escape mechanism from death: the cancer lesson. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2791–806. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santidrian AF, Matsuno-Yagi A, Ritland M, Seo BB, LeBoeuf SE, Gay LJ, et al. Mitochondrial complex I activity and NAD+/NADH balance regulate breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1068–81. doi: 10.1172/JCI64264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Wang SY, Nottke AC, Rocheleau JV, Piston DW, Goodman RH. Redox sensor CtBP mediates hypoxia-induced tumor cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2006;103:9029–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603269103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelicano H, Lu W, Zhou Y, Zhang W, Chen Z, Hu Y, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species imbalance promote breast cancer cell motility through a CXCL14-mediated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2375–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jerby L, Wolf L, Denkert C, Stein GY, Hilvo M, Oresic M, et al. Metabolic associations of reduced proliferation and oxidative stress in advanced breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5712–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamarajugadda S, Stemboroski L, Cai Q, Simpson NE, Nayak S, Tan M, et al. Glucose oxidation modulates anoikis and tumor metastasis. Molec Cell Biol. 2012;32:1893–907. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06248-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erol A. Retrograde regulation due to mitochondrial dysfunction may be an important mechanism for carcinogenesis. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65:525–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imanishi H, Hattori K, Wada R, Ishikawa K, Fukuda S, Takenaga K, et al. Mitochondrial DNA mutations regulate metastasis of human breast cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohtaki T, Shintani Y, Honda S, Matsumoto H, Hori A, Kanehashi K, et al. Metastasis suppressor gene KiSS1 encodes peptide ligand of a G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2001;411:613–7. doi: 10.1038/35079135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Navarro VM, Tena-Sempere M. Neuroendocrine control by kisspeptins: role in metabolic regulation of fertility. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2012;8:40–53. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kotani M, Detheux M, Vandenbogaerde A, Communi D, Vanderwinden JM, Le Poul E, et al. The metastasis suppressor gene KiSS-1 encodes kisspeptins, the natural ligands of the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR54. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34631–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muir AI, Chamberlain L, Elshourbagy NA, Michalovich D, Moore DJ, Calamari A, et al. AXOR12: A novel human G protein-coupled receptor, activated by the peptide KiSS-1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:28969–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102743200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nash KT, Phadke PA, Navenot J-M, Hurst DR, Accavitti-Loper MA, Sztul E, et al. KISS1 metastasis suppressor secretion, multiple organ metastasis suppression, and maintenance of tumor dormancy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:309–21. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beck BH, Welch DR. The KISS1 metastasis suppressor: a good night kiss for disseminated cancer cells. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gerencser AA, Neilson A, Choi SW, Edman U, Yadava N, Oh RJ, et al. Quantitative microplate-based respirometry with correction for oxygen diffusion. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6868–78. doi: 10.1021/ac900881z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dranka BP, Benavides GA, Diers AR, Giordano S, Zelickson BR, Reily C, et al. Assessing bioenergetic function in response to oxidative stress by metabolic profiling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:1621–35. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lunt SY, Vander Heiden MG. Aerobic glycolysis: meeting the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:441–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCarty MF, Whitaker J. Manipulating tumor acidification as a cancer treatment strategy. Altern Med Rev. 2010;15:264–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kroemer G, Pouyssegur J. Tumor cell metabolism: cancer’s Achilles’ heel. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:472–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sennoune SR, Bakunts K, Martinez GM, Chua-Tuan JL, Kebir Y, Attaya MN, et al. Vacuolar H+-ATPase in human breast cancer cells with distinct metastatic potential: distribution and functional activity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286:C1443–C1452. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00407.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hinton A, Sennoune SR, Bond S, Fang M, Reuveni M, Sahagian GG, et al. Function of a subunit isoforms of the V-ATPase in pH homeostasis and in vitro invasion of MDA-MB231 human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:16400–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901201200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nishisho T, Hata K, Nakanishi M, Morita Y, Sun-Wada GH, Wada Y, et al. The a3 isoform vacuolar type H+-ATPase promotes distant metastasis in the mouse B16 melanoma cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:845–55. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spiegelman BM, Heinrich R. Biological control through regulated transcriptional coactivators. Cell. 2004;119:157–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis: the central role of PGC-1alpha. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:208–17. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ko HS, Uehara T, Tsuruma K, Nomura Y. Ubiquilin interacts with ubiquitylated proteins and proteasome through its ubiquitin-associated and ubiquitin-like domains. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:110–4. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: The metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward PS, Thompson CB. Metabolic reprogramming: a cancer hallmark even warburg did not anticipate. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:297–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dang CV. Rethinking the Warburg effect with Myc micromanaging glutamine metabolism. Cancer Res. 2010;70:859–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dang CV. Links between metabolism and cancer. Genes Dev. 2012;26:877–90. doi: 10.1101/gad.189365.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raghunand N, Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Microenvironmental and cellular consequences of altered blood flow in tumours. Br J Radiol. 2003;76(Spec No 1):S11–S22. doi: 10.1259/bjr/12913493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ruch RJ, Klaunig JE, Kerckaert GA, LeBoeuf RA. Modification of gap junctional intercellular communication by changes in extracellular pH in Syrian hamster embryo cells. Carcinogenesis. 1990;11:909–13. doi: 10.1093/carcin/11.6.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez-Zaguilan R, Seftor EA, Seftor REB, Chu YW, Gillies RJ, Hendrix MJC. Acidic pH enhances the invasive behavior of human melanoma cells. Clin Exptl Metastasis. 1996;14:176–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00121214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlappack OK, Zimmermann A, Hill RP. Glucose starvation and acidosis: effect on experimental metastatic potential, DNA content and MTX resistance of murine tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 1991;64:663–70. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1991.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rozhin J, Sameni M, Ziegler G, Sloane BF. Pericellular pH affects distribution and secretion of cathepsin B in malignant cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6517–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Forgac M. Vacuolar ATPases: rotary pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:917–29. doi: 10.1038/nrm2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kane PM. The where, when, and how of organelle acidification by the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2006;70:177–91. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.70.1.177-191.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagner CA, Finberg KE, Breton S, Marshansky V, Brown D, Geibel JP. Renal vacuolar H+-ATPase. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1263–314. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feilchenfeldt J, Brundler MA, Soravia C, Totsch M, Meier CA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) and associated transcription factors in colon cancer: reduced expression of PPARgamma-coactivator 1 (PGC-1) Cancer Lett. 2004;203:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee HJ, Su Y, Yin PH, Lee HC, Chi CW. PPAR(gamma)/PGC-1(alpha) pathway in E-cadherin expression and motility of HepG2 cells. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:5057–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang Y, Ba Y, Liu C, Sun G, Ding L, Gao S, et al. PGC-1alpha induces apoptosis in human epithelial ovarian cancer cells through a PPARgamma-dependent pathway. Cell Res. 2007;17:363–73. doi: 10.1038/cr.2007.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.D’Errico I, Salvatore L, Murzilli S, Lo SG, Latorre D, Martelli N, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1alpha) is a metabolic regulator of intestinal epithelial cell fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:6603–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016354108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lehman JJ, Barger PM, Kovacs A, Saffitz JE, Medeiros DM, Kelly DP. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 promotes cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. JCI. 2000;106:847–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI10268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Watkins G, Douglas-Jones A, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. The localisation and reduction of nuclear staining of PPARgamma and PGC-1 in human breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:483–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Girnun GD. The diverse role of the PPARgamma coactivator 1 family of transcriptional coactivators in cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:381–8. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vega RB, Huss JM, Kelly DP. The coactivator PGC-1 cooperates with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in transcriptional control of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation enzymes. Molec Cell Biol. 2000;20:1868–76. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.5.1868-1876.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lehman JJ, Kelly DP. Transcriptional activation of energy metabolic switches in the developing and hypertrophied heart. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:339–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gao M, Liu D. The liver X receptor agonist T0901317 protects mice from high fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. AAPS J. 2013;15:258–66. doi: 10.1208/s12248-012-9429-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gastaldi G, Russell A, Golay A, Giacobino JP, Habicht F, Barthassat V, et al. Upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator gene (PGC1A) during weight loss is related to insulin sensitivity but not to energy expenditure. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2348–55. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0782-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barger JF, Plas DR. Balancing biosynthesis and bioenergetics: metabolic programs in oncogenesis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:R287–R304. doi: 10.1677/ERC-10-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burton JD, Goldenberg DM, Blumenthal RD. Potential of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma antagonist compounds as therapeutic agents for a wide range of cancer types. PPAR Res. 2008;2008:494161. doi: 10.1155/2008/494161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Samudio I, Harmancey R, Fiegl M, Kantarjian H, Konopleva M, Korchin B, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of fatty acid oxidation sensitizes human leukemia cells to apoptosis induction. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:142–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI38942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafer ZT, Grassian AR, Song L, Jiang Z, Gerhart-Hines Z, Irie HY, et al. Antioxidant and oncogene rescue of metabolic defects caused by loss of matrix attachment. Nature. 2009;461:109–13. doi: 10.1038/nature08268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.