Abstract

The HIV-1 capsid protein plays a crucial role in viral infectivity, assembling into a cone that encloses the viral RNA. In the mature virion, the N-terminal domain of the capsid protein forms hexameric and pentameric rings, while C-terminal domain homodimers connect adjacent N-terminal domain rings to one another. Structures of disulfide-linked hexamer and pentamer assemblies, as well as structures of the isolated domains have been solved previously. The dimer configuration in C-terminal domain constructs differs in solution (residues 144–231) and crystal (residues 146–231) structures by ~30°, and it has been postulated that the former connects the hexamers while the latter links pentamers to hexamers. Here we study the structure and dynamics of full-length capsid protein in solution, comprising a mixture of monomeric and dimeric forms in dynamic equilibrium, using ensemble simulated annealing driven by experimental NMR residual dipolar couplings and X-ray scattering data. The complexity of the system necessitated the development of a novel computational framework that should be generally applicable to many other challenging systems that currently escape structural characterization by standard application of mainstream techniques of structural biology. We show that the orientation of the C-terminal domains in dimeric full-length capsid and isolated C-terminal domain constructs is the same in solution, and obtain a quantitative description of the conformational space sampled by the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain on the nano- to millisecond time-scale. The positional distribution of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain is large and modulated by the oligomerization state of the C-terminal domain. We also show that a model of the hexamer/pentamer assembly can be readily generated with a single configuration of the C-terminal domain dimer, and that capsid assembly likely proceeds via conformational selection of sparsely-populated configurations of the N-terminal domain within the capsid protein dimer.

Keywords: HIV-1 capsid, conformational sampling, NMR spectroscopy, residual dipolar couplings, solution X-ray scattering, ensemble simulated annealing refinement

INTRODUCTION

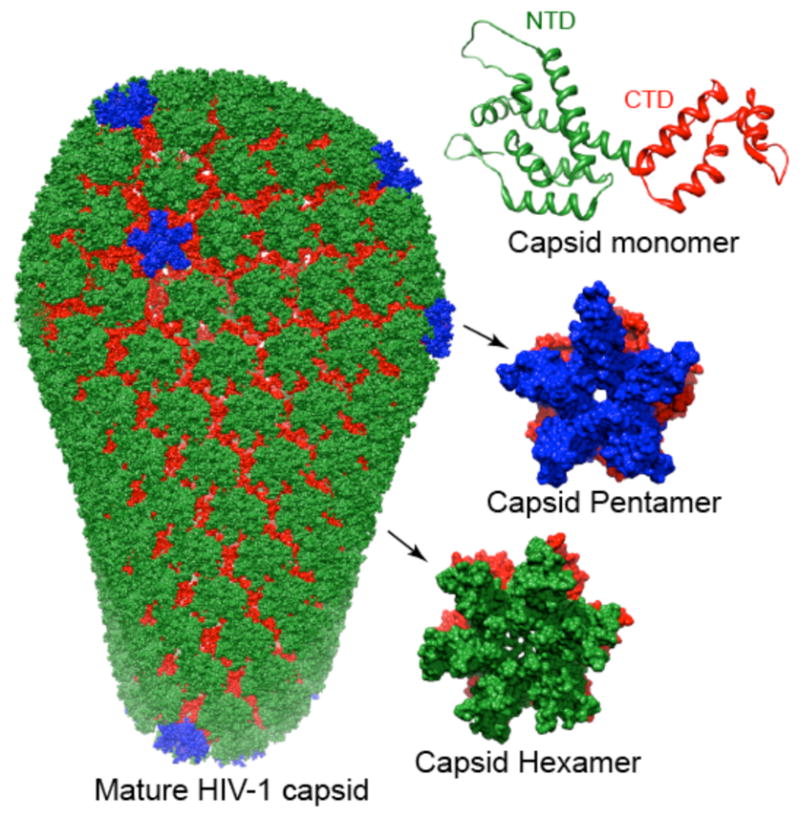

In the mature human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) approximately 1500 copies of the capsid protein form a fullerene-like cone that encapsulate the viral RNA.1–4 The capsid protein consists of two domains, an arrow shaped N-terminal domain (NTD, residues 1–145) and a globular C-terminal domain (CTD, residues 150–221), connected by a short linker (residues 146–149) (Figure 1).3,4 The exterior of the mature capsid comprises ~250 hexameric N-terminal domain rings and exactly 12 pentameric units (Figure 1).5–7 Adjacent N-terminal domain rings are connected to one another by symmetric C-terminal domain homodimers which are essential for the overall assembly process.8,9

Figure 1. HIV-1 capsid assembly.

The capsid protein (top right) comprises N- (green) and C- (red) terminal domains.10 During capsid assembly, the N-terminal domains forms pentameric7 (middle right) and hexameric11 (bottom right) rings (with the N-terminal domains shown in blue and green, respectively, and the C-terminal domains shown in red in both oligomers). A model of the fully assembled capsid (left) comprises adjacent hexamers connected to each other via C-terminal domain dimers and exactly 12 pentamers are required to close the cone.7

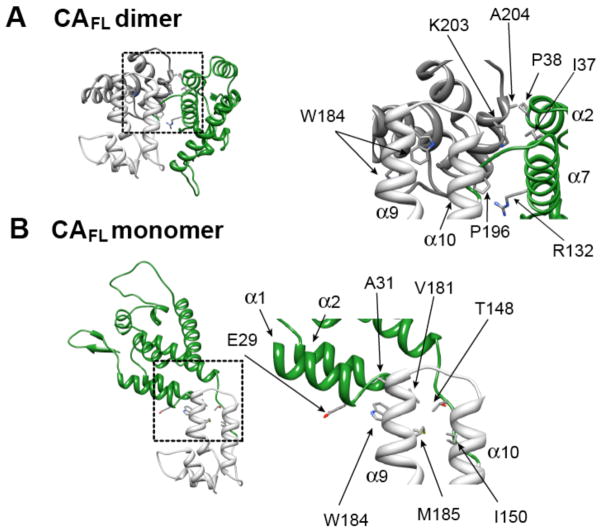

Structural investigation of full-length HIV-1 capsid protein (Figure 2) has been problematic owing to the presence of large-scale interdomain motions between the N- and C-terminal domains. To date, structures of full-length capsid protein in non-physiological dimeric10,12 and monomeric13 forms have been studied by crystallography and NMR, respectively. In addition, several structures of isolated N- and C-terminal domain constructs have been solved.14–17 Comparison of these structures indicates that although the C-terminal domain exhibits a common fold, the relative orientation of the two C-terminal domains in the dimer varies considerably. For example, two similar C-terminal domain constructs, one solved by NMR (PDB id 2KOD,17 residues 144–231), the other by crystallography (PDB id 1A43,15,16 residues 146–231) have similar equilibrium dimerization constants but differ by ~30° in their subunit orientation (Figure 3A). Both these dimeric C-terminal domain configurations were utilized in constructing a model of the mature HIV-I capsid where the orientation observed in the NMR structure was used to connect N-terminal domain hexamers while the orientation observed in the crystal structure was used to connect N-terminal domain pentamers to hexamers.7 These observations gave rise to the notion that the C-terminal domain dimer is conformationally malleable and that this malleability is essential for the effective incorporation of pentamers in the mature capsid, which in turn dictates the lattice curvature. Despite limited evidence from previous solution NMR studies that the N- and C-terminal domains do not appear to interact with one another in the full-length capsid protein,17 the overall magnitude and time-scale of the relative motions between the domains are unknown, and the conformational space sampled by the domains has not yet been characterized.

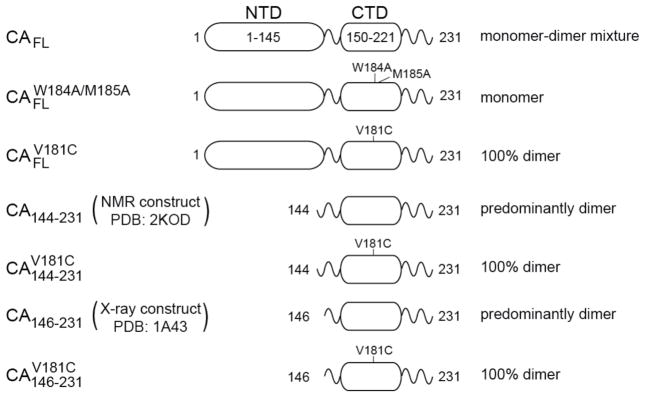

Figure 2.

Summary of capsid constructs used in the current work. The delineation of the N- and C-terminal domains and the location of point mutations in the various constructs are shown. The dimerization state of the constructs under the experimental conditions used for NMR and SAXS/WAXS measurements are also indicated.

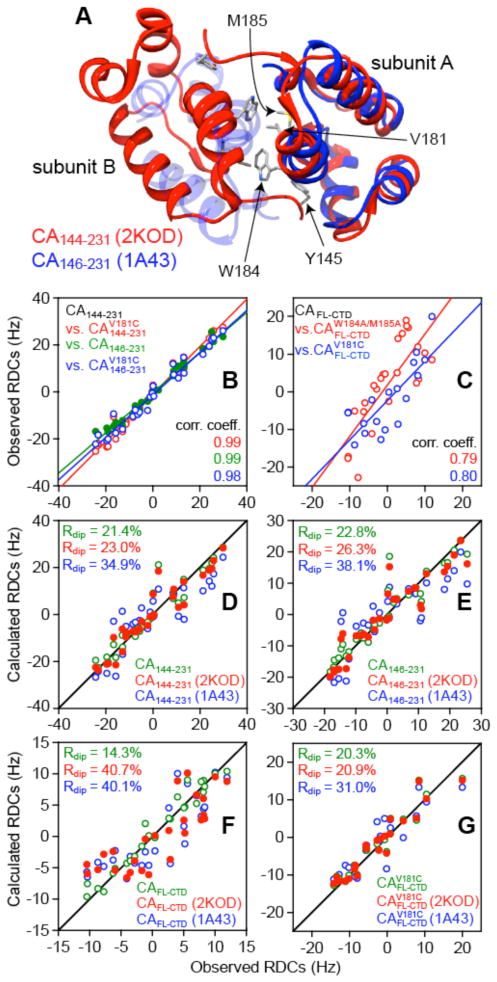

Figure 3.

Residual dipolar coupling (RDC) analysis of the relative orientation of the C-terminal domains in full-length capsid and C-terminal domain constructs. (A) Superposition of the coordinates of the CA144-231 NMR structure (PDB id 2KOD,17 red) and the CA146-231 crystal structure (PDB id 1A43,16 opaque and semi-transparent blue) best-fit to subunit A. (B) RDCs (measured in bicelles) for the CA144-231 construct (x axis) are highly correlated to those for the shorter CA146-231 construct (green), as well as the engineered (red) and (blue) dimers (y-axis). (C) The backbone 1DNH RDCs (measured in bicelles) for the C-terminal domain of full-length wild-type capsid (CAFL, x axis) are poorly correlated to those of either the mutant dimer (blue) or the mutant monomer (red) (y-axis) due to the existence of a dynamic monomer-dimer equilibrium (see Table 3). Agreement between experimental RDCs (in bicelles) for the C-terminal domain constructs (D) CA144-231 and (E) CA146-231 and for the C-terminal domain of the full-length (F) wild-type capsid (CAFL) and (G) mutant dimer with the calculated RDCs for a single C-terminal domain subunit (green) and for the C-terminal domain dimer in the NMR (red; 2KOD17) and X-ray (blue; 1A4315,16) orientations. The coordinates for the C-terminal domain of the full-length capsid protein crystal structure (PDB id 3NTE10) are used as a template for SVD analysis.

Here we explore the conformational space sampled by the monomeric and dimeric species of the wild-type, full length HIV-1 capsid protein, CAFL (Figure 2) using experimental NMR residual dipolar couplings (RDC) and small and wide angle solution X-ray scattering (SAXS/WAXS) data in an ensemble simulated annealing protocol, supplemented by NMR relaxation measurements and analytical ultracentrifugation. Methodology was developed to treat the simultaneous determination of monomer and dimer ensemble structures along with optimal ensemble weights.

To date, attempts to study the full-length capsid protein by conventional solution NMR methods have been hampered by severe resonance line-broadening of the backbone resonances of the linker residues, as well as of residues at the dimer interface as a consequence of a dynamic monomer-dimer exchange. Although such localized line broadening is an impediment for traditional NMR structure determination, it can be circumvented providing a limited number of RDCs can be measured within each domain of the full-length capsid protein, and the structures of the individual domains in the full-length capsid and the isolated domain constructs are the same. Under these conditions, the individual domains of a multi-domain protein/macromolecular assembly can be treated as rigid bodies for ensemble simulated annealing calculations in which RDCs arising from steric alignment provide both shape and orientational information18,19 while the SAXS/WAXS data provide complementary restraints on size and shape.20,21 This hybrid approach is much less time consuming than conventional methods of NMR structure determination20 and can readily be transferred to other multi-domain proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression and purification

All full-length HIV-1 capsid constructs, the wild-type (CAFL, residues 1–231, plasmid pNL4-3), the disulfide-linked mutant ( ) and monomeric mutant ( ), as well as the four C-terminal domain constructs, CA144-231 and CA146-231 and the corresponding disulfide-linked-linked mutants ( and ) (see Figure 2) were sub-cloned in a pET-11a vector and expressed in BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL competent cells (Agilent Technologies). Point mutations were performed using the QuikChange™ kit (Agilent Technologies). Uniformly labeled proteins were expressed at 37°C using the following standard protocol. Briefly, cells were grown in 1 L minimal M9 medium containing 0.5 g/L 2H/15N/13C Isogro (Sigma-Aldrich), 2H2O, 1g/L 15NH4Cl and 3g/L 2H7,13C6-D-glucose for 2H/15N/13C labeling; 0.3 g/L 2H/15N Isogro (Sigma-Aldrich), 2H2O, 1g/L 15NH4Cl and 3g/L 2H7,12C6-D-glucose for 2H /15N labeling; and 1g/L 15NH4Cl for 15N labeling. Cells, induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at an optical density of A600 ~0.6, were harvested 8 hours later and re-suspended in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (BME) and 1 cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablet (Roche Applied Science). All proteins were purified by combination of ion exchange and size exclusion chromatography. The cell lysate was loaded onto a HiPrep 16/10 DEAE FF column (GE Healthcare) with a 0–1 M NaCl gradient in buffer containing 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA and 5 mM BME. Relevant flow-through fractions were concentrated (Amicon ultra-15, 3 and 10 kDa cutoff) and loaded onto a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM BME and 200 mM NaCl (for all the disulfide-linked dimers, no reducing agent was used during and after this step of the purification). All proteins were further purified using a Mono S™ 10/100 GL column (GE Healthcare) with a 0–1 M NaCl gradient in buffer containing 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0 and 5 mM BME. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing and mass spectrometry (using an Agilent 1100 LC/MS system equipped with an Agilent Zorbax 300SB-C3 column coupled to a quadrupole mass analyzer).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Concentrated samples of the purified full-length and C-terminal domain constructs of the capsid protein (uniformly 15N labeled) in 50 mM NaCl, 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) were loaded into 3 mm 2-channel epon centerpiece cells (100 μL), whereas dilute samples were loaded into 12 mm 2-channel epon centerpiece cells (400 μL). Disulfide-linked dimers were analyzed in the same buffer without DTT. Sedimentation velocity experiments were conducted at 20.0, 25.0 and 35.0°C and 50 krpm on a Beckman Coulter ProteomeLab XL-I analytical ultracentrifuge using both the absorbance (250 or 280 nm) and Rayleigh interference optical systems. Time-corrected sedimentation data were analyzed in SEDFIT14.122,23 in terms a continuous c(s) distribution covering an s range of 0.0 – 6.0 S with a resolution of 120 and a confidence level (F-ratio) of 0.68. Excellent fits were obtained with r.m.s.d. values ranging from 0.003 – 0.010 fringes or 0.003 – 0.008 absorbance units. The solution density (ρ) and viscosity (η) for the buffer were calculated based on the solvent composition using SEDNTERP 1.0924 (Hayes, D.B., Laue, T. & Philo, J. http://www.jphilo.mailway.com). The partial specific volumes of the various protein constructs (v) were calculated based on the amino acid composition using SEDNTERP 1.09 and corrected for uniform 15N labeling. Sedimentation coefficients were corrected to standard conditions s20,w.

The wild-type CAFL samples were studied by sedimentation velocity at concentrations of 100, 33, 22, 11 and 3.2 μM using a combination of 3 mm and 12 mm path-length cells. Global absorbance data collected at 280 nm and Rayleigh interference data collected at 655 nm were analyzed in terms of a reversible monomer-dimer self-association by direct Lamm equation modeling25 in SEDPHAT 9.426 (http://www.analyticalultra-centrifugation.com) to obtain the equilibrium constant. Excellent fits were obtained with r.m.s.d. values ranging from 0.0035 to 0.011 fringes or 0.0029 to 0.0053 absorbance units. The protein extinction coefficient at 280 nm and interference signal increment27 used for the calculations were determined based on the amino acid composition in SEDNTERP 1.09 and SEDFIT 12.7, respectively. The interference signal increment was corrected for the uniform 15N labeling.

For sedimentation equilibrium experiments, samples were loaded at various concentrations into 3 mm 2-channel epon centerpiece cells (40 μL) and 12 mm 6-channel epon centerpiece cells (135 μL). Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were conducted at 20.0, 25.0 and 35.0°C and various rotor speeds on a Beckman Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge with absorbance data collected at 250 and 280 nm. Data were analyzed globally in terms of a single non-interacting species or a monomer-dimer self-association with implicit mass conservation in SEDPHAT 9.4 essentially as described.28 Excellent fits were obtained with r.m.s.d. values ranging from 0.0030 to 0.012 absorbance units. In all cases, 95% confidence limits of the fitted parameters were obtained using the method of F-statistics.29

NMR Sample Preparation

All heteronuclear NMR experiments were performed on uniformly 15N/13C/2H labeled samples (unless stated otherwise) prepared in buffer containing 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 93% H2O/7% D2O and 1 mM DTT (with the latter omitted for the disulfide-linked dimers). Aligned samples were prepared using phage pf1 (Asla biotech),30,31 and DMPC/06:0 Diether PC bicelles (q=3) (Avanti polar lipids) doped with 0.1% PEG-2000-PE (Avanti polar lipids) to improve bicelle stability.32 Addition of PEG-2000-PE was not necessary for the C-terminal domain constructs. 1DNH RDC data for all proteins were measured on samples containing 0.2 mM protein in subunits (either 2H/15N/13C or 2H/15N labeled). In addition, for the wild-type CAFL construct, RDCs in bicelles were measured at three protein concentrations (0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 mM in subunits). For 15N relaxation measurements on 2H/15N-labeled and constructs, a protein concentration of 0.5 mM in subunits was employed.

NMR Spectroscopy

All heteronuclear NMR experiments were carried out at 35°C on Bruker 500 and 800 MHz spectrometers equipped with z-gradient triple resonance cryoprobes. Spectra were processed using NMRPipe33 and analyzed using the CCPN software suite.34 Sequential 1H, 15N, and 13C backbone resonance assignments were performed using conventional TROSY-based35 through-bond three-dimensional triple resonance experiments.36 Backbone (1DNH) RDCs were measured on perdeuterated proteins using the TROSY-based ARTSY technique37 and analyzed using Xplor-NIH.38 15N-R1, 15N-R1ρ and heteronuclear 15N-{1H} NOE measurements were carried out on uniformly 2H/15N-labeled disulfide-linked and monomeric constructs using newly developed pulse schemes with a TROSY readout39 at 1H frequencies of 500 and 800 MHz. For the CA144-231 construct, heteronuclear 15N-{1H} NOE measurements were carried out on a uniformly 2H/15N/13C-labeled sample at a 1H frequency of 500 MHz. Eight different decay durations were sampled in an interleaved manner for each relaxation time measurement (see Supplementary Information [SI] Figure S3 for additional details). The 15N-{1H} NOE and reference spectra were recorded with a 10 second saturation time for the NOE measurement and equivalent recovery time for the reference measurement in an interleaved manner, each preceded by an additional 1 sec recovery time.

SAXS/WAXS Data Collection

All SAXS/WAXS data were collected at Beam Line 12-IDB, Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL) and conducted at 25°C. The sample buffer was the same as that employed in the NMR experiments except for the use of H2O instead of 93% H2O/7% D2O.

For the wild-type CAFL (15N-labeled), X-ray scattering data were acquired at protein concentrations of 6.5 and 3.25 mg/mL (0.26 and 0.13 mM, respectively in subunits) using a Pilatus 2M detector positioned 3.04 m from the sample capillary in a highly offset geometry with 12 keV incident radiation resulting in an observable q-range of 0.01 – 0.70 Å−1. Scattered radiation was detected subject to an 11 keV low-energy cutoff. For the monomer mutant (15N-labeled), X-ray scattering data were acquired using a mosaic Gold CCD detector positioned in an on-center geometry, 3.08 and 0.48 m from the sample capillary using 18 keV incident radiation, resulting in an observable q-range of 0.01 – 0.21 Å−1 for the small angle and 0.10 – 0.23 Å−1 for the wide-angle data. To evaluate the effect of the monomer/dimer equilibrium for CAFL and the magnitude of a possible inter-particle structure factor, data were collected for protein concentrations of 0.63, 1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 mg/mL. Q-axis mapping was done using a silver behenate standard sample. A total of 20 sequential data frames with exposure times of 10 seconds for the wild-type CAFL and 2 seconds for the mutant were recorded with the samples kept at 25°C throughout the measurements. To prevent radiation damage, volumes of 120 μL of samples and buffers were oscillating during data collection. Individual data frames were masked, corrected for the detector sensitivity, radially integrated and normalized by the corresponding incident beam intensities and sample transmissions. The final 1D scattering profiles and their uncertainties were calculated as means and mean uncertainties over the 20 individual frames. The buffer data were then subtracted from the samples. For wild-type CAFL, the data at both 6.5 and 3.25 mg/mL were used in the structure analysis, and for the mutant data collected at concentrations of 2.5 mg/mL were used.

For the C-terminal domain constructs (15N-labeled CA144-231 and CA146-231), X-ray scattering data were acquired using a mosaic Gold CCD detector positioned in an on-center geometry, 2m and 0.5m from the sample capillary using 18 keV incident radiation, resulting in the observable q-range of 0.007 – 0.285 Å−1 for the small-angle and 0.10 – 2.3 Å−1 for the wide-angle data. To evaluate the the magnitude of a possible inter-particle structure factor, the small-angle data were collected for protein concentrations of 1.25, 2.5, and 5.0 mg/mL while the wide-angle data were collected only for the 5 mg/mL protein samples. Q-axis mapping was done using a silver behenate standard sample. A total of 20 sequential data frames with exposure times of 2 seconds for the small-angle and 2.5 seconds for the wide-angle data were recorded with the samples kept at 25°C throughout the measurement. To prevent radiation damage, volumes of 100 μL of samples and buffers were oscillating during data collection. Individual data frames were masked, corrected for the detector sensitivity, radially integrated and normalized by the corresponding incident beam intensities and sample transmissions. The final 1D scattering profiles and their uncertainties were calculated as means and mean uncertainties over the 20 individual frames. The buffers data were then subtracted from the samples. Data at 5 mg/mL were used in the structure refinement.

Although SAXS/WAXS data were also acquired for the mutant dimer, the consistent presence of small amounts of higher molecular weight species reflected in batch-to-batch variability, likely due to intermolecular cross-linking involving the two free cysteines at positions 198 and 218, precluded their use in structure calculations. In the case of wild type CAFL and the monomer mutant, the inclusion of the reducing agent DTT in the sample buffer prevented intermolecular cross-linking from occurring; for the disulfide-linked mutant dimer, however, DTT could not be employed as DTT also reduces the engineered disulfide bond at the dimer interface between Cys181 of one subunit and Cys181 of the other.

Structure calculations and computational methodology

Structure calculations were performed in Xplor-NIH38,40 using an ensemble comprised of a mixture of dimer and monomer species of wild-type CAFL. For most calculations, equal numbers of dimers ( ) and monomers ( ) were employed, ranging from 1 to 6 for each species corresponding to a total ensemble size ranging from 2 to 12. The RDCs and SAXS/WAXS profiles were calculated as a population-weighted average with the fraction of dimer and monomer species determined directly from the experimental Kdimer values determined by analytical ultracentrifugation (Table 3). Note that there is a subtle difference in the averaging used for the RDC and SAXS/WAXS data: for the RDCs, averaging is on a subunit basis, that is the fraction of subunits that are dimeric and monomeric; for the SAXS/WAXS data, on the other hand, averaging is based on the molar fraction of monomer and dimer species.

Table 3.

Monomer-dimer equilibrium for full-length and C-terminal domain constructs of HIV-1 capsid determined by analytical ultracentrifugation.

| Construct |

Kdimer (μM)a

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 20°C | 25°C | 35°C | |

| CAFL | 20±3b,c | 40±3d | 82±9d |

| CA144-231e | 7±3b | 9.8±0.6f | 16±3b |

| CA146-231e | 23±6b,g | - | 24±4b |

The confidence intervals in the Kdimer values are reported as ±1 standard deviation.

Determined from sedimentation equilibrium data. The fraction of subunits that are dimeric in the NMR RDC experiments conducted at 35°C and a subunit concentration of 0.2 mM is 0.82 for CA144-231 and 0.78 for CA146-231.

The value reported by Gamble et al.15 for CAFL at 20°C is 18±0.6 μM.

Determined from sedimentation velocity data by simultaneously fitting global absorbance and Rayleigh interference data. The same values within experimental error were obtained from sedimentation equilibrium data. The fraction of subunits that are dimeric in the NMR RDC experiments conducted at 35°C is 0.42, 0.53 and 0.64 at subunit concentrations of 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 mM, respectively. The molar fraction of dimer in the SAXS/WAXS experiments conducted at 25°C is 0.51 and 0.61 at subunit concentrations of 0.127 and 0.254 mM, respectively.

At 20°C, the CA144-231 and CA146-231 constructs are predominantly dimeric (92 and 90%, respectively, at subunit concentrations of 0.52 and 0.55 mM) with sedimentation coefficients of 1.95 S and 1.92 S, respectively and a molecular weight (MW) of ~21 kDa (which compares to a calculated dimer molecular weight of 19.9 kDa). The and C-terminal domain constructs behave as monodisperse dimers with molecular weights of ~20 kDa. The full-length mutant construct behaves as a monodisperse dimer with a sedimentation coefficient of 3.30S and MW of 54 kDa (compared to the calculated value of 51.2 kDa). The full-length mutant construct (at 410 μM and 20°C) behaves as a monodisperse monomer with a sedimentation coefficient of 2.17 S and a molecular weight of 22.3 kDa (compared to a calculated value of 25.4 kDa).

From Byeon et al.17

The value reported by Gamble et al.15 for CA146-231 at 20°C is 10±3 μM.

The calculations employed the SARDC potential term19 which calculates the alignment tensor from molecular shape as applicable for RDC experiments performed using a purely steric alignment medium such as neutral bicelles. In the time-scale regime considered here, each ensemble member has its own effective alignment tensor, and if one were to use the common practice of letting the alignment tensors float to optimize the fit to the experimental RDC data, the fit would be unstable and ill-determined as there would be far too many parameters for the given data. The original SARDC term was updated and corrected for this work: specifically, corrections included proper calculation of the gradient with respect to the alignment tensor; and updates included adding support for pairwise averaging such that a single restraint table can be simultaneously used for symmetric homodimers and the monomeric species.

The target function for the SARDC term is proportional to the χ2 metric given by:

| (1) |

where δi is the calculated RDC value for residue i, is the observed experimental value, Δδi is an error and NRDC is the number of observed RDCs. Errors arise from both experimental and coordinate error. As the backbone of the N- and C-terminal domains were held fixed during the calculations, we chose to set the errors to the difference between the observed values and the RDC values calculated using SVD on the isolated domains. Due to the definition of in Eq. 1, this choice effectively down-weights the RDCs which fit the individual subunits less well. The errors associated with the RDCs for the C-terminal domain were further scaled down by the product of two factors: To compensate for the fact that the magnitude of the C-terminal domain RDCs are smaller than those of the N-terminal domain, a factor of 0.5 was applied to the C-terminal domain RDC errors. In addition, to account for the fact that more RDCs were measured for the N-terminal domain, an additional scale factor of was applied to the C-terminal domain RDC errors, where NCTD and NNTD are the number of measured RDCs for the C- and N-terminal domains, respectively.

The merged SAXS/WAXS curves were used in the range q = qmin to 0.65 Å−1, linearly interpolated at 30 points. SAXS/WAXS errors were scaled by a factor of 1/√20 to account for the fact that they were obtained by averaging 20 curves. Corrections for globbing, numerical integration over solid angle20 and bound-solvent contributions were recomputed at each temperature of simulated annealing. For computation of the final SAXS/WAXS curves and value, 100 points were used and a cubic spline was used to evaluate I(q) at each experimental value of q.

Two energy terms were used to maintain the proper symmetry for each calculated ensemble of dimers. In these calculations, the C2 symmetry of the full ensemble must be maintained, but the individual ensemble members need not possess this symmetry as they are analogous to snapshots in time. Thus, the approach traditionally used for homodimer structure calculation41 was augmented. Typically, a non-crystallographic symmetry (NCS) term42 is used to keep the coordinates of dimer subunits identical and distance symmetry restraints are used to enforce C2 symmetry. Here, we updated Xplor-NIH’s posDiffPot term to restrain the ensemble-averaged atomic positions in each subunit to be the same, and also introduced a variance tensor restraint, such that the ensemble-averaged deviation from the mean coordinate positions were restrained to be identical. The variance tensor for atom j in subunit η is defined as:

| (2) |

where qη,j,i is the position of atom j of subunit η in ensemble member i; α and β select the three Cartesian components x,y and z; wi is the weight of ensemble member i; and <·> denotes ensemble average. The restraint can now be defined: the variance in subunit A of atom j should be the same as that in subunit B for all atoms:

| (3) |

where kvar is a force constant and N is the number of atoms. While the term is easily formulated, there are subtleties involved in deriving an expression for the gradient, as it involves derivatives of the rotation matrix which best-fits subunits A and B, a dependence which is not present for the standard non-crystallographic symmetery potential term. Finally, the distance symmetry restraint was applied to ensemble-averaged atomic positions to maintain C2 symmetry of the resulting ensemble.

Torsion angles were restrained by the torsionDB multidimensional torsion angle database potential of mean force43 applied to all active torsion angles. A separate torsionDB term with increased force constant was applied to the torsion angles in the linker region. A knowledge-based low-resolution hydrophobic contact potential, the residueAff term,44 was used to help characterize any potential interactions between N- and C-terminal domain residues. Standard terms to enforce covalent geometry (bonds, angles and improper torsions) were applied, in addition to a quartic repulsive non-bonded term45 to prevent atomic overlap.

For all structure calculations, the backbone atoms of the C-terminal domains were kept fixed and the backbone atoms of the N-terminal domains moved as rigid bodies, while atoms in the linker region (residues 146–149) were given all degrees of freedom. The ensemble members (both monomer and dimer) were allowed to move freely with respect to one another (i.e. while a van der Waals repulsion term prevented atomic overlap within each ensemble member, atomic overlap between different ensemble members is allowed since the ensemble reflects a population distribution). Sidechain atoms of the N- and C-terminal domains were given torsion angle degrees of freedom throughout.

All active torsion angles (including those in the linker region) were initially randomized by ±8° and an initial gradient minimization performed. High temperature dynamics was run for 800 ps or 8000 steps, whichever came first. Simulated annealing was performed from 3000 to 25 K in 25 K increments. Simultaneously, force constants were geometrically scaled as specified in Table S2. At each temperature, dynamics was performed for the shorter of 100 steps or 0.2 ps. Final gradient minimization was performed after simulated annealing.

Variable ensemble weights

In this work, ensemble weights were allowed to vary to improve the fit, and to reduce the ensemble size required for a good fit. Ensemble weights were encoded using N-sphere coordinates, xi:

| (4) |

with the radial component r taken to be 1, and the Ne − 1 angular coordinates ϕi encoded as bond angles of pseudo-atoms. Ensemble weights wi are then given as

| (5) |

and they obey the normalization condition Σwi = 1.

With this representation of ensemble weights, computation of the gradient with respect to pseudo-atom coordinates is straightforward. Facilities within Xplor-NIH are now provided to make it convenient to optimize ensemble weights for any ensemble energy term by providing the derivative with respect to ensemble weight. As of this writing, ensemble weight derivative support has been added to the SAXS and SARDC potential terms, as well as to the two symmetry terms used in this work.

To avoid instabilities due to wild gyrations in ensemble weight values early in the structure calculations, we also introduced a stabilizing energy term:

| (6) |

where kweight is a force constant which is generally large at the start of a structure calculation, and small at the end. The target value of was taken as 1/Ne in this work. In this work the dimer/monomer ratio was held fixed to the value determined by analytical ultracentrifugation and a separate energy term (Eweight) was used for the monomer and dimer ensembles.

Projection contour map of the N-terminal domain distribution relative to the C-terminal domain

The distribution of the position of the centroid of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain was represented by a projection with the origin at the centroid of the C-terminal domain and the z direction taken to be the average of the positions of all N-terminal domain centroids, the x direction perpendicular to the z direction and the C2 symmetry axis of the dimer, and the y direction taken to obey the right-hand rule. For the dimer structures, the B subunit was first rotated about its symmetry axis before computation of the position of the N-terminal domain. Note that this projection map does not capture rotation of the N-terminal domain about its centroid.

Pentamer calculation

The calculation of the pentamer of capsid dimers utilized the coordinates for the model of the intact capsid fullerene shell generated in ref. 7 and kindly provided by Mark Yaeger. In this calculation, a pentamer of CAFL dimers was utilized in which the inner N-terminal domains take the pentamer structure given by PDB id 3P057 and the outer N-terminal domains are each members of different hexamers (PDB id 3H47)11. In the initial coordinates the N-terminal domains are connected by the flexible linker to the C-terminal domain dimers in the configuration found in the crystal structure of CA146-231 (PDB id 1A4315,16). For our purposes the outer N-terminal domains were fixed in space to the initial coordinates, and the remainder of each hexamer was not included in the calculation. The inner associated N-terminal domains were grouped together such that they rotated and translated as a rigid body in the 3P057 configuration. The C-terminal domains were allowed all torsion angle degrees of freedom, while the linker regions were given all degrees of freedom. A non-crystallographic symmetry-type potential term forced the backbone atoms of each C-terminal domain dimer towards the solution structure of the CA144-231 dimer (PDB id 2KOD17). Other energy terms included a torsion angle restraint to force all torsion angles in the linker to lie in the range −175…−45°, the torsion angle database potential of mean force, and standard bond length, bond angle, improper torsion angle and repulsive non-bonded energy terms. The optimization protocol started with 10 ps of molecular dynamics at 3000 K, followed by simulated annealing molecular dynamics from 3000 to 25 K in 12.5 K increments, at each step performing the smaller of 0.2 ps or 100 steps of dynamics. Finally, conjugate gradient minimization was performed on the annealed structures.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Subunit orientation of the C-terminal domains within the capsid dimer

The relative orientation of the C-terminal domains within the dimer of the various full-length and C-terminal domain constructs of the capsid protein (Figure 2) was assessed from backbone amide (1DNH) RDC measurements in two alignment media, neutral bicelles46 and negatively charged phage pf1.30,31 RDCs provide orientational information on bond vectors relative to an external alignment tensor.47 The alignment tensor in bicelles is determined by molecular shape while that in pf1 is affected by both shape and charge distribution. In a symmetric homodimer, one of the principal axes of the alignment tensor lies along the C2 symmetry axis.48 If the dimer orientation is correct, the RDC R-factor for the fits of the RDCs to the atomic coordinates of the dimer should be only slightly larger (by 2–3% due to the constraint imposed on the alignment tensor by C2 symmetry and errors in the RDCs themselves) than those for the fits to an individual subunit.

A superposition of the 1H-15N TROSY correlation spectra of the three full-length capsid constructs is shown in SI Figure S1A. Contrary to earlier reports,17,49 excellent spectral quality was obtained for the wild-type capsid protein (CAFL) through perdeuteration, coupled with the use of low protein concentrations (≤0.5 mM in subunits) to avoid aggregation. It should be noted that 1HN/15N cross-peaks for residues within and adjacent to the linker region (residues 145–154), as well as for residues at or near the C-terminal domain dimerization interface (residues 169–193), especially those close to the side chain of Trp184, are broadened out in wild type CAFL due to conformational exchange between monomer and dimer species on a time-scale that is intermediate on the chemical shift time-scale (SI Figure S1A). However, the overall high quality of the NMR spectrum of CAFL yielded sufficient RDCs within the C-terminal domain to permit subsequent analysis.

The 1DNH RDCs measured for the four C-terminal domain constructs (cf. Figure 2) are highly correlated to one another (Figure 3B and SI Figure S2B), indicating that the relative orientation of the two subunits within the dimer is the same. Singular value decomposition (SVD) fits of the RDCs were obtained using the coordinates of the 1.95 Å resolution crystal structure of full-length capsid (PDB id 3NTE)10 as a template since this coordinate set provides the best fits to the RDCs in both phage and bicelles for a single subunit (Table 1). (Note that the head-to-tail dimer seen in this crystal structure with the dimer interface formed by intersubunit interactions between the N- and C-terminal domains is a crystallization artifact and does not exist in solution). The SVD fits to the dimer in the orientation found in the NMR structure of CA144-231 (PDB id 2KOD)17 are only minimally worse than the corresponding fits to a single subunit, while the fits to the orientation found in the X-ray structure of CA146-231 (PDB id 1A43)16 are significantly poorer (Figures 1D and E; and SI Figure S1D). Moreover, rigid-body simulated annealing refinement against the RDC and SAXS/WAXS data for the CA144-231 and CA146-231 constructs yield very similar structures (SI Figure S2D) which lie within 0.3–0.6 Å backbone rms of the NMR structure of the CA144-231 construct.17 One can therefore conclude that the subunit orientation for the four C-terminal domain constructs (Figure 2) in solution is identical to that of the NMR structure of CA144-231,17 and that the orientation seen in the crystal structure of CA146-231 15,16 is likely a result of crystal packing. (Note that while the experimental data is consistent with a zero population of this crystal form in solution, one cannot rule out the presence of a small population of the latter. Based on the expected impact on the RDC R-factors, the upper limit fraction, however, is likely to be less than 10%.)51 These observations are also consistent with the finding that the N-terminal residues of the CA144-231 construct, up to residue 148, are disordered in solution as evidenced by 15N-{1H} heteronuclear NOE values of less than 0.1 (SI Figure S3B), and hence are unlikely to impact the orientation of the C-terminal domains within the dimer.

Table 1.

SVD fits of experimental RDCs in two alignment media (phage pf1 and bicelles) to an individual C-terminal domain of HIV-1 capsid from three different structures.a

| Construct | Number of RDCsc | RDC R-factor (%) phage / bicellesb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3NTE (X-ray 1.95Å) (1–231)d | 2KOD (NMR) (146–231) | 1A43 (X-ray 2.6 Å) (144–231)d | |||

| CAFL | 25 / 26 | 12.7 / 14.3 | 12.8 / 27.4 | 24.9 / 21.9 | |

|

|

26 / 22 | 18.8 / 20.3 | 16.9 / 28.5 | 24.4 / 33.5 | |

|

|

46 / 43 | 18.5 / 19.4 | 15.7 / 22.5 | 29.2 / 28.9 | |

| CA144–231 | 31 / 31 | 17.3 / 21.4 | 15.3 / 18.3 | 16.5 / 23.2 | |

|

|

41 / 37 | 19.0 / 18.0 | 17.2 / 16.5 | 18.9 / 21.0 | |

| CA146–231 | 24 / 32 | 14.0 / 22.8 | 20.0 / 18.6 | 23.0 / 24.1 | |

|

|

39 / 35 | 18.7 / 18.4 | 16.6 / 16.4 | 19.2 / 21.1 | |

All experiments were carried out on samples containing 0.2 mM protein in 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 6.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1mM DTT and 1 mM EDTA at 35°C.

The RDC R-factor is defined as {<(Dobs − Dcalc)2>/(2<Dobs2>)}1/2 where Dobs and Dcalc are the observed and calculated RDCs, respectively.50 The first and second numbers refer to the SVD fits in alignment media of phage pf1 and bicelles, respectively. The concentrations of phage employed were as follows: 11 mg/ml for the CAFL, and samples; 7mg/ml for the CA144-231 and CA146-231 samples, and 5 mg/ml for the and samples. The concentrations of bicelles employed were as follows: 5% (w/v) for the CAFL, CA144-231 and CA146-231 samples; and 3.5% (w/v) for the and samples. The bicelles comprised 1,2-dimyritoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine/1,2-di-O-hexyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocoline (DMPC/06:0 diether PC); q=3. For the full length capsid constructs, bicelles were doped with 0.1% (w/v) PEG-2000-PE to improve the bicelle stability.32

The RDCs only include residues in secondary structure elements.

Backbone amide protons were added using standard geometry to the X-ray coordinates (PDB id 3NTE and 1A43) using Xplor-NIH.38

The 1DNH RDCs for the C-terminal domain of wild-type capsid (CAFL), however, are poorly correlated to those measured on either the engineered dimer or the monomer (Figure 3C). The SVD fits for the RDCs of are comparable for the dimer orientation seen in the CA144-231 NMR structure and an individual subunit (Figure 3G, SI Figure S1C and Table 2). The RDCs for the C-terminal domain of CAFL, however, do not fit the dimer in either the NMR or X-ray orientations (Figure 3F, Figure S1C and Table 2). This is not due to an alternative subunit orientation of the C-terminal domains in the wild type CAFL dimer but rather to the presence of a significant amount of monomer in the NMR samples as the equilibrium dimerization constant (Kdimer) for CAFL at 35°C (~82 μM) is 3 to 5-fold lower than those for CA144-231 (~16 μM) and CA146-231 (~24 μM) (Table 3). When the RDC data for the C-terminal domain of CAFL at three different concentrations (0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 mM) are fit simultaneously by SVD to the appropriate mixture of monomer and dimer, an excellent fit is obtained using the dimer configuration in the CA144-231 NMR structure. Moreover, the RDC data for the C-terminal domain of wild-type CAFL and the mutant dimer can be fit simultaneously to the same orientation using a single alignment tensor for the dimer (SI Table S1). The corresponding fits using the orientation seen in the crystal structure of CA146-231 are significantly worse (SI Table S1). Given these results we conclude that the relative orientation of the C-terminal domains in the wild-type CAFL dimer is the same as that in the NMR structure of CA144-231.17

Table 2.

Comparison of SVD fits of experimental RDCs measured on full-length and C-terminal domain constructs of HIV-1 capsid protein.

| phage pf1/bicellesb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

η | R-factor (%) | ||

| CA144–231 | ||||

| CTD subunit | −16.4 / 18.5 | 0.64 / 0.40 | 17.3 / 21.4 | |

| CTD dimer 2KOD orientation | 17.2 / 17.9 | 0.55 / 0.42 | 20.1 / 23.0 | |

| CTD dimer 1A43 orientation | 21.4 / 16.1 | 0.06 / 0.56 | 33.0 / 34.9 | |

|

| ||||

| CTD subunit | −12.0 / 20.0 | 0.53 / 0.42 | 19.0 / 18.3 | |

| CTD dimer 2KOD orientation | −11.6 / 19.4 | 0.63 / 0.41 | 19.4 / 18.6 | |

| CTD dimer 1A43 orientation | 13.6 / 18.1 | 0.18 / 0.52 | 33.6 / 27.0 | |

| CA146–231 | ||||

| CTD subunit | −19.9 / 16.1 | 0.64 / 0.31 | 14.0 / 22.8 | |

| CTD dimer 2KOD orientation | 20.8 / 15.6 | 0.55 / 0.39 | 16.2 / 26.3 | |

| CTD dimer 1A43 orientation | 22.8 / 13.7 | 0.14 / 0.51 | 29.3 / 38.1 | |

|

| ||||

| CTD subunit | −11.6 / 19.4 | 0.58 / 0.36 | 18.7 / 18.4 | |

| CTD dimer 2KOD orientation | 11.4 / 18.6 | 0.64 / 0.34 | 19.5 / 19.3 | |

| CTD dimer 1A43 orientation | 13.8 / 17.5 | 0.10 / 0.45 | 32.2 / 28.4 | |

|

| ||||

| CTD subunit | 13.7 / 10.6 | 0.39 / 0.21 | 18.8 / 20.3 | |

| CTD dimer 2KOD orientation | 14.1 / 10.3 | 0.40 / 0.17 | 20.9 / 20.9 | |

| CTD dimer 1A43 orientation | 13.5 / 7.1 | 0.56 / 0.40 | 25.6 / 31.0 | |

| CAFL | ||||

| CTD subunit | 15.2 / −7.4 | 0.19 / 0.43 | 12.7 / 14.3 | |

| CTD dimer 2KOD orientation | 14.9 / 6.5 | 0.13 / 0.08 | 19.3 / 40.7 | |

| CTD dimer 1A43 orientation | 15.9 / 5.6 | 0.09 / 0.15 | 20.8 / 40.1 | |

The coordinates of the 1.95 Å resolution crystal structure of CAFL (PDB id 3NTE)10 are used as a template to construct C-terminal domain (CTD) dimers in the orientation of the CA144-231 NMR structure (PDB id 2KOD)17 or the CA146-231 X-ray structure (PDB id 1A43).16 This ensures that the results of the different SVD fits can be directly compared to one another.

The first and second numbers refer to the SVD fits in alignment media of phage pf1 and bicelles, respectively. Sample conditions are given in Table 1. The number of RDCs for the individual C-terminal domain subunits is given in Table 1, and for the fits to the dimer coordinates the number of RDCs is doubled (one set for each subunit). is the magnitude of the principal component of the alignment tensor and η the rhombicity.

Large amplitude interdomain motions in full-length capsid

For the three full-length capsid constructs (cf. Figure 2), the magnitude of the principal components of the alignment tensors for the N-terminal domain are different (larger) than those for the C-terminal domain (Table 4, and SI Figures S1B and C), indicative of large amplitude motions of the two domains relative to one another.52,53 Moreover, the 15N-{1H} heteronuclear NOE values for the linker (residues 146–149) connecting the N- and C-terminal domains of the monomeric and dimeric full-length capsid mutants are <0.6 indicative of a high degree of local internal mobility (SI Figure S3). Analysis of 15N relaxation data collected at 500 and 800 MHz (SI Figure S3) for the dimeric and monomeric mutants using an extended Lipari-Szabo model54,55 with an axially symmetric diffusion tensor yields overall correlation times of ~29 and ~17 ns, respectively, with anisotropies of ~1.8 and ~1.6, respectively. The time-scale of the interdomain motions probed by the relaxation measurements are described by an effective slow internal correlation time of 2–5 ns. (Note that the RDCs probe interdomain motions up to the millisecond time-scale). Taken together the above observations all support a large degree of interdomain motion, likely reflecting the absence of stable interactions at the contact interface between the N- and C-terminal domains of CAFL.

Table 4.

Comparison of alignment tensors in two alignment media (phage pf1 and bicelles) for the N- and C-terminal domains of an individual subunit of wild-type capsid (CAFL) and the dimeric ( ) and monomeric ( ) mutants

| Number of RDCsb | N-terminal domain | C-terminal domain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Hz) | η | R-factor (%) | (Hz) | η | R-factor (%) | |||

| Phage pf1 | ||||||||

| CAFL | 44/25 | −22.8 | 0.56 | 14.6 | 15.2 | 0.19 | 12.7 | |

|

|

42/26 | −25.7 | 0.41 | 16.4 | 13.7 | 0.39 | 18.8 | |

|

|

40/46 | −25.1 | 0.53 | 16.2 | 15.4 | 0.10 | 18.5 | |

| Bicelles | ||||||||

| CAFL | 54/26 | 18.9 | 0.32 | 10.2 | −7.4 | 0.43 | 14.3 | |

|

|

43/22 | 15.8 | 0.32 | 15.1 | 10.6 | 0.21 | 20.3 | |

|

|

82/43 | 26.5 | 0.36 | 12.3 | −11.7 | 0.39 | 19.4 | |

The alignment tensors were obtained by SVD using the X-ray coordinates of full-length capsid (PDB id 3NTE)10 as a template. is the magnitude of the principal component of the alignment tensor and η the rhombicity.

The first and second numbers refer to the number of RDCs measured for the N- and C-terminal domains, respectively.

Quantitative description of interdomain motions in wild-type capsid protein

To quantitatively determine the conformational space sampled by the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain in wild-type CAFL, we made use of RDC- and SAXS/WAXS-driven simulated annealing.20,38 The RDCs induced by steric alignment through transient interactions with the neutral liquid crystalline bicelles provide both shape (see below) and orientational information,18,19 which complements the shape and size information afforded by SAXS/WAXS. (Note that RDCs measured in pf1 include alignment effects in part due to electrostatic interactions and were therefore not used in these calculations.) The complementarity of the two techniques is critical to resolving multiple possible solutions in a system involving a mixture of species (monomer and dimer), each comprising an ensemble of states, as neither technique alone is capable of providing a unique solution.

The starting coordinates consisted of dimer and monomer species whose N- (residues 1–145) and C-terminal (residues 150–221) domains were taken from the crystal structure of full-length capsid (PDB id 3NTE).10 The dimer was constructed by best-fitting the Cα coordinates of the C-terminal domain onto those of the NMR structure of CA144-231.17 Since the N-terminal domain samples a large region of conformational space relative to the C-terminal domain, an ensemble representation was employed. With interdomain motions on the nanosecond to millisecond time-scale, every member of the ensemble has a different alignment tensor calculated directly from the overall molecular shape18,19 as described in Material and Methods. For all structure calculations the backbone atoms of the C-terminal domains were kept fixed, the backbone atoms of the N-terminal domains moved as rigid bodies, and atoms in the linker region (residues 146–149) were given all degrees of freedom. Wild-type CAFL comprises a concentration-dependent mixture of monomer and dimer (cf. Table 3) treated as described in Materials and Methods.

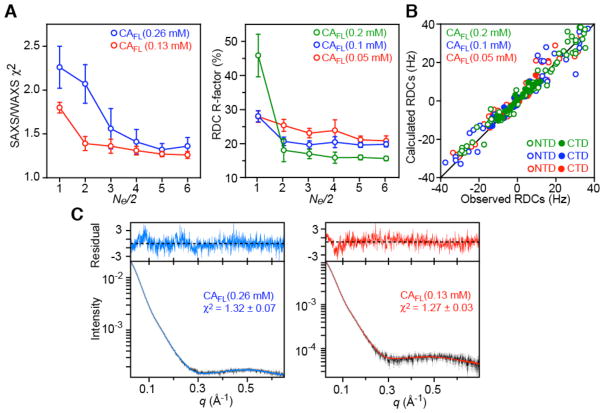

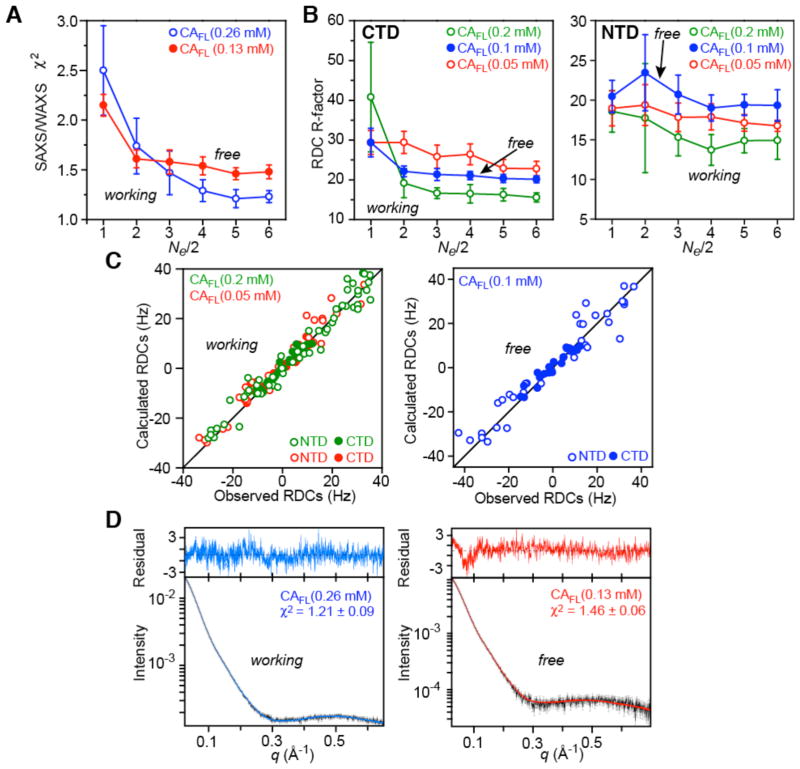

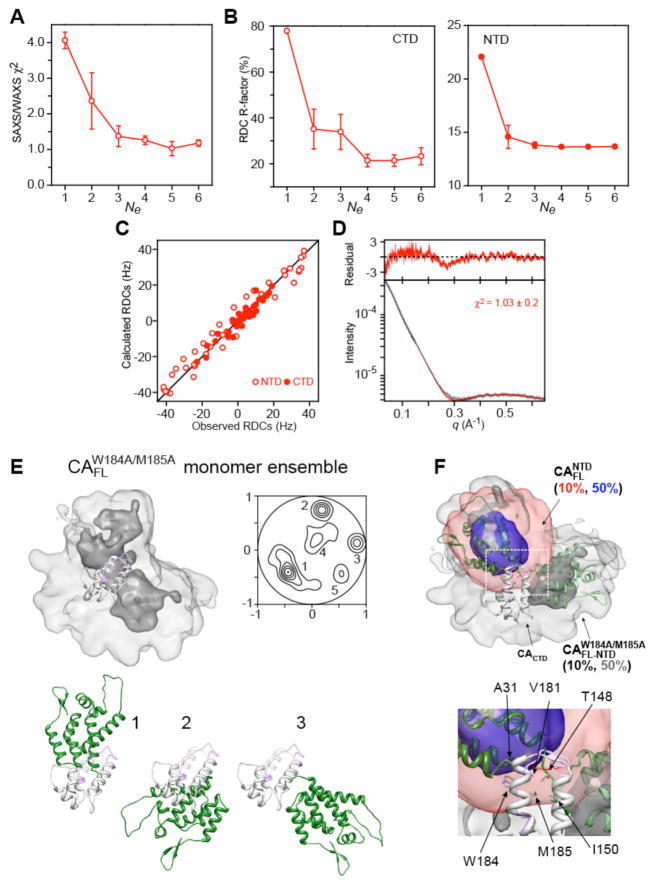

Several calculations with total ensemble sizes Ne ranging from 2 to 12 ( ) were carried out for the wild-type CAFL (Figures 4 and 5, and Table 5): refinement against the SAXS/WAXS (25°C) and RDC (35°C) data at all concentrations (0.127 and 0.254 mM in subunits for SAXS/WAXS, and 0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 mM in subunits for the RDCs); refinement against the wild-type CAFL SAXS/WAXS data at high concentration (0.254 mM) and the RDC data at high (0.2 mM) and low (0.05 mM) concentrations, with cross-validation against the SAXS/WAXS data at low concentration (0.127 mM) and the RDC data at intermediate concentration (0.1 mM). The latter calculations (Figure 5) safeguard against overfitting the experimental data. The optimal ensemble size was found to be Ne = 10 ( ) (Figures 4A and 5A). The positional distributions of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain for the wild-type CAFL dimer and monomer are depicted as atomic probability and projection contour maps in Figures 6A and B, respectively.

Figure 4.

SAXS/WAXS and RDC-driven ensemble simulated annealing refinement of the wild-type capsid protein CAFL. Each ensemble comprises the same number of monomers and dimers (i.e. weighted according to their populations at different concentrations as determined by analytical ultracentrifugation (Table 3). (A) SAXS/WAXS χ2 and C-terminal domain RDC R-factors as a function of ensemble size Ne/2. Note that the RDC R-factors for the N-terminal domain show a much smaller decrease with increasing Ne (see Table 5 and Fig. 7A). (B) Agreement between observed and calculated 1DNH RDCs at three CAFL concentrations (0.2, 0.1 and 0.05 mM shown in green, blue and red, respectively). Note the smaller span of the RDCs for the C-terminal domain (filled-in circles, ~ ±15 Hz) compared to those for the N-terminal domain (open circles, ~ ±40 Hz). (C) Agreement between observed and calculated SAXS/WAXS curves. The experimental SAXS/WAXS data are shown in black with grey vertical bars equal to 1 s.d., and the calculated curves are shown in blue and red for the data at CAFL concentrations of 0.26 and 0.13 mM (in subunits), respectively. The residuals, given by , are plotted above the curves.

Figure 5.

SAXS/WAXS and RDC-driven ensemble simulated annealing calculations for the wild-type capsid protein CAFL with cross-validation. The calculations are identical to those reported in Figure 4 except that the low concentration (0.13 mM in subunits) SAXS/WAXS and intermediate concentration (0.1 mM) RDC data have been omitted (“free” data sets, closed circles). Thus the working data sets (open circles) comprise the high concentration (0.26 mM) SAXS/WAXS data and the high (0.2 mM) and low (0.05 mM) concentration RDC data. (A) SAXS/WAXS χ2 and (B) RDC R-factors for the C-(left) and N- (right) terminal domains as a function of ensemble size Ne/2. (C) Agreement between observed and calculated RDCs for the working (left) and free (right) datasets. (D) Agreement between observed and calculated SAXS/WAXS curves for the working (left) and free (right) datasets. The experimental SAXS/WAXS data are shown in black with grey vertical bars equal to 1 s.d., and the calculated curves are shown in blue and red for the working and free datasets, respectively. The residuals given by are plotted above the curves.

Table 5.

Structural statistics for refinements against SAXS/WAXS and bicelle RDC data for wild-type CAFL and the mutant monomer using an ensemble size of Ne = 10 ( ) to represent the conformational space sampled by the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain

| CAFL (calculations with all data)a | CAFL (calculations with cross-validation)b |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAXS/WAXS χ2 | ||||

| 0.26 mM | 1.27±0.03 | 1.21±0.09 | 1.03±0.03 | |

| 0.13 mM | 1.32±0.07 | 1.46±0.06 | ||

| RDC R-factors (%) | ||||

| All | ||||

| 0.2 mM | 14.1±1.6 | 15.0±1.5 | 14.7±0.5 | |

| 0.1 mM | 18.7±0.9 | 19.5±1.2 | ||

| 0.05 mM | 18.0±0.8 | 17.8±1.0 | ||

| NTD (1–145) | ||||

| 0.2 mM | 14.0±1.7 | 14.9±1.5 | 13.6±0.1 | |

| 0.1 mM | 18.6±1.0 | 19.4±1.3 | ||

| 0.05 mM | 17.6±0.9 | 17.1±1.1 | ||

| CTD (150–221) | ||||

| (0.2 mM) | 16.0±0.7 | 16.3±1.6 | 21.4±2.5 | |

| (0.1 mM) | 19.6±0.7 | 20.3±1.0 | ||

| (0.05 mM) | 21.1±1.1 | 22.9±2.2 |

The complete CAFL dataset used for refinement comprises two concentrations (0.127 and 0.254 mM in subunits) for the SAXS/WAXS data at 25°C, and three concentrations (0.05, 0.1 and 0.2 mM in subunits) for the NMR RDC data at 35°C.

Entries in bold italics indicate cross-validated values where the data for that entry are left out during refinement. The CAFL data used included in the refinement comprise a single concentration (0.254 mM in subunits) for the SAXS/WAXS data at 25°C and two concentrations (0.2 mM and 0.05 mM in subunits) for the RDC data at 35°C.

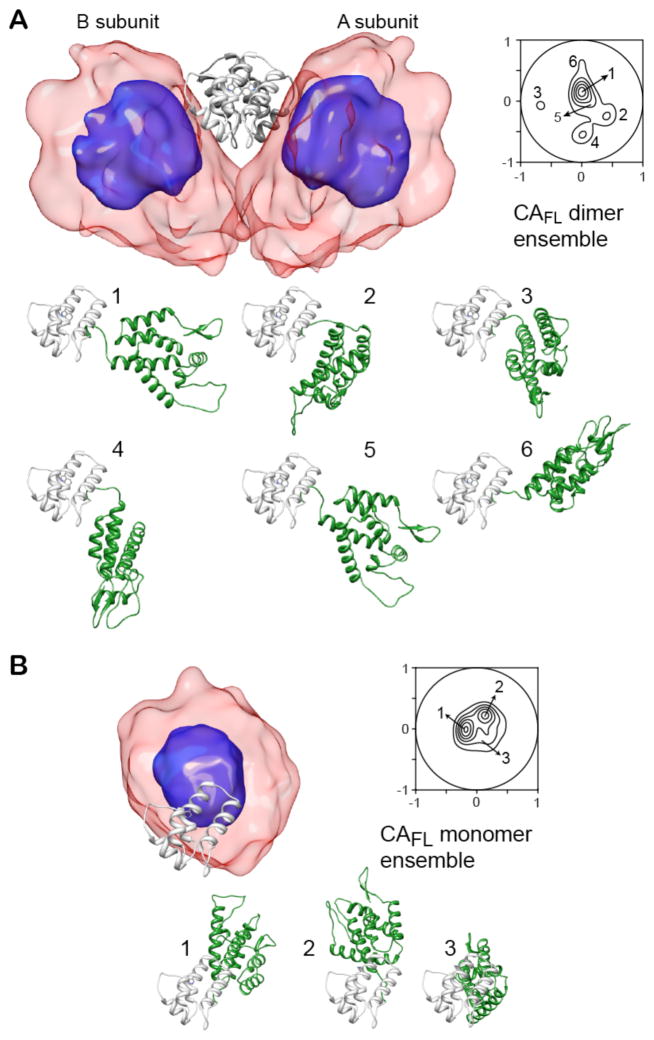

Figure 6.

Structural ensembles calculated for the wild-type capsid (CAFL) dimer (A) and monomer (B). The overall distribution of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain (light and dark grey ribbons) is displayed as a reweighted atomic probability plotted at 50% (blue) and 10% (transparent red) of maximum. Also shown are projection contour maps that display the distribution of the position of the centroid of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain (see Methods). The dimer and monomer ensembles are characterized by 6 and 3 main clusters, respectively. Representative structures from each cluster are shown as ribbon diagrams with a single C-terminal domain subunit in light grey and the N-terminal domain in green. The orientation of the displayed C-terminal domain for the dimer and monomer clusters is the same as that of the A subunit (light grey) shown in the top of panel A. For simplicity, only a single subunit is shown for the six dimer clusters.

The dimer and monomer CAFL ensembles were also cross-validated against the bicelle RDC data obtained for the dimer and monomer mutants (SI Figure S4). While the wild-type CAFL dimer ensemble cross-validates well against the bicelle RDCs for the mutant dimer, cross-validation is poor for the monomer CAFL ensemble versus the bicelle RDCs for the monomer mutant (SI Figure To ascertain the reason for the latter observation we also carried out RDC and SAXS/WAXS-driven ensemble simulated annealing calculations for the monomer mutant (Figure 7). The optimal ensemble size was also found to be , but the distribution of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain for the monomer mutant was over twice as large as that for the wild-type CAFL monomer (Figures 7E and F). This finding can be attributed to destabilization of the N-terminal end of the dimerization helix (Fig. S3A) induced by the double W184A/M185A mutation (see below).

Figure 7.

SAXS/WAXS and RDC-driven ensemble simulated annealing calculations for the monomer mutant. (A) SAXS/WAXS χ2 and (B) RDC R-factors for the C- (left) and N- (right) terminal domains as a function of ensemble size Ne. (C) Agreement between observed and calculated RDCs is shown in red. (D) Agreement between observed and calculated SAXS/WAXS curves. The experimental SAXS/WAXS data are shown in black with grey vertical bars equal to 1 s.d., and the calculated curves are shown in red. The residuals given are plotted above the curves. (E) Overall distribution of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain (light grey ribbon) is displayed as a reweighted atomic probability plotted at 50% (dark grey) and 10% (light grey) of maximum. Projection contour maps that display the distribution of the position of the centroid of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain are shown; the mutant monomer is characterized by five main clusters. Representative structures from clusters 1–3 are shown as ribbon diagrams with the C-terminal domain in light grey and the N-terminal domain in green. The orientation of the C-terminal domain is the same as that shown for the wild-type ensemble in Figure 6. The residues corresponding to the N-terminal half (residues 178–186) of the dimerization helix are highly mobile in solution as judged by 15N-{1H} heteronuclear NOE values <0.6 (see SI Figure S3A). These residues are also unstructured in the crystal structure of the capsid hexamer formed by the W184A/M185A mutant (PDB id 3H47)11 and are displayed as a semi-transparent purple ribbon. (F) Comparison of the N-terminal domain ensemble distributions found in full-length wild-type CAFL monomer and the monomer mutant. The atomic probability density maps are contoured at 50% (blue for CAFL and dark grey for ) and 10% (red for CAFL, light grey for ). Representative structures of the N-terminal domain are shown in dark and semi-transparent green for the wild-type and mutant, respectively. The insets provide a closeup view of the interface between the N- and C-terminal domains seen in cluster 2 of the wild-type monomer (cf. Figure 6B).

For the wild-type CAFL monomer, the flexible linker (residues 146–149) and a relatively small monomeric C-terminal domain (~9 kDa) allow the larger N-terminal domain (~16 kDa) to sample a distinct region of conformation space that does not overlap with that sampled by the N-terminal domain in the wild-type dimer (Figures 6A and B). These differences in the distribution of the N-terminal domain can be directly attributed to the oligomerization state of the C-terminal domain. The dimerization helix (residues 179–192) in the wild-type C-terminal domain is rigid and hydrophobic (Figure 3A). In the monomer, the hydrophobic residues of the dimerization helix (Val181, Trp184, Met185) are solvent exposed and transiently interact in one of the clusters (cluster 2; Figure 8B) with several residues of the N-terminal domain (such as Glu29 and Ala31 in the loop connecting helices 1 and 2), as well as with residues in the linker region (Thr148 and Ile150) (Figures 7F and 8B, and SI Figure S5B). Formation of the C-terminal domain dimer effectively blocks these transient interactions between the N- and C-terminal domains as the hydrophobic residues of the C-terminal domain dimerization helix are located at the dimer interface and are therefore no longer accessible. Enhancement of the transient intrasubunit interactions between the N- and C-terminal domains seen in the wild-type CAFL monomer ensemble by the introduction of various hydrophobic mutations in the loop connecting helices 1 and 2 of the N-terminal domain might explain the reduction in capsid assembly rate observed for the double E28A/E29A mutant,6 even though these residues are not involved in either the formation of N-terminal domain oligomers or in the intermolecular helix-capping interactions between the N- and C- terminal domains found in hexameric and pentameric capsid assemblies.7,11 Hydrophobic capsid assembly inhibitors, such as CAP156 and the recently discovered benzodiazepine and benzimidazole-related compounds,57 which distort the loop connecting helices 3 and 4 may act in a similar manner by shifting the monomer-dimer equilibrium in favor of the capsid monomer.

Figure 8.

Transient interdomain contacts observed in the cluster 2 configurations for the wild-type capsid CAFL dimer and monomer. For the dimer (A), only a single N-terminal domain (green) attached to its corresponding C-terminal domain (light grey) is shown; the C-terminal domain of the second subunit of the dimer is shown in dark grey. For the monomer (B), the orientation of the C-terminal domain (light grey) is the same as that of the light grey C-terminal domain domain in the dimer. The insets shown in the right panels provide close-up views of the interface between the N- and C-terminal domains.

In the wild-type CAFL dimer the conformational space sampled by the N-terminal domain in the CAFL monomer is no longer accessible due to intersubunit steric clash with the C-terminal domain (cf. Figure 6). As a result, the wild-type CAFL dimer exhibits a distinct distribution of the N-terminal domain coupled with a distinct pattern of transient interactions between the N- and C-terminal domains. A small (~5%) population (Cluster 6 in Figure 6A) of the N-terminal domain configurations sampled in the wild-type CAFL dimer ensemble is functionally relevant as it closely resembles the configurations observed in both hexameric and pentameric capsid assemblies (Figure 9C). The Cluster 6 configuration, however, does not exhibit any intersubunit interactions between the N- and C-terminal domains. Transient intersubunit interactions between the N- and C-terminal domains in the CAFL dimer are predominantly observed in the Cluster 2 configuration (Figure 8A) and involve contacts between helix 10 of the C-terminal domain (Pro196, Lys203, Ala204) and helices 2 (Pro34, Ile37, Pro38) and 7 (Arg 132) of the N-terminal domain (Figure 8A and SI Figure S5A). Mutation of Pro38, Arg132 and Lys203 to a hydrophobic residue is predicted to enhance intersubunit contacts between the N- and C-terminal domains, thereby reducing the population of the Cluster 6 configurations relevant for capsid assembly and providing a possible explanation for the reduced capsid assembly rates observed for the P38A, R132A and K203A mutants.6,58,59

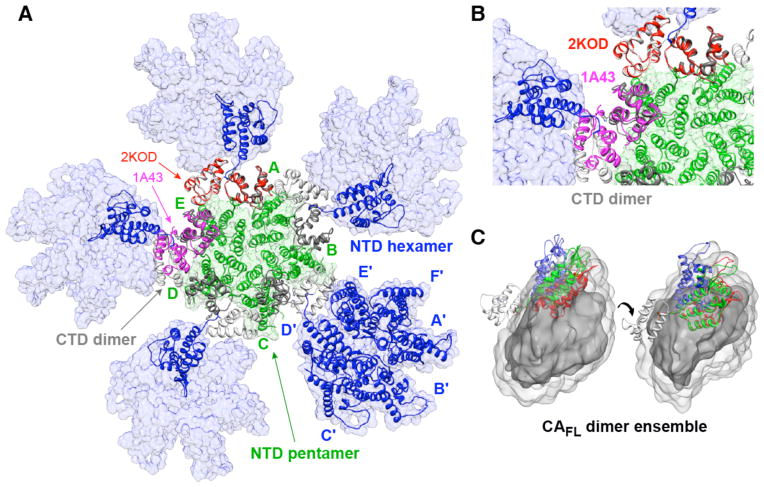

Figure 9.

Model of the interface between a pentamer and surrounding hexamers in a HIV-1 capsid fullerene cone. (A) Overall model7 generated with the C-terminal domain dimers in the orientation found in the NMR structure of CA144-231.17 The pentamer ring of N-terminal domains is shown in green, the C-terminal domain dimers in light and dark grey, and the hexamer rings of N-terminal domains in blue. Also shown in red and purple are superpositions of the C-terminal domain dimer in the orientations seen in the NMR structure of CA144-231 (2KOD)17 and the X-ray structure of CA146-231 (1A43),15,16 respectively. The only difference between this model and that presented by Pornillos et al.7 is that in the latter model the dimer orientation of the C-terminal domain subunits at the interface of the pentamer and hexamer rings of N-terminal domains was assumed to be in the X-ray dimer orientation. An expanded view is shown in (B). (C) Comparison of the position of the N-terminal domain found within the pentamer (green) and hexamer (blue) rings with that for cluster 6 (cf. Figure 6A) found in the wild type CAFL dimer ensemble (red). Only a single subunit is displayed in two orientations, differing by about 60°, with the C-terminal domain is shown as a light grey ribbon, and the atomic probability density map of the N-terminal domain in dark (10% contour) and light (2% contour) grey.

The N-terminal domain in the mutant monomer, on the other hand, samples a much larger region of conformational space than in the wild-type CAFL monomer (Figure 7E and F). The latter is partially restricted not only by transient interactions between Trp184 of the C-terminal domain and residues of the N-terminal domain (see above), but also by interactions between Met185 and residues in the linker (e.g. Thr148 and Ile150). In the mutant monomer, however, substitution of Trp184 and Met185 by Ala results in destabilization of the N-terminal end (residues 181–188) of the dimerization helix as evidenced by 15N-{1H} heteronuclear NOE data (SI Figure S3A); hence, the interactions involving Trp184 and Met185 that limit the conformational space sampled in the wild-type monomer are no longer supported in the mutant monomer. (Note that in the crystal structure of the capsid hexamer formed by a disulfide-linked variant of the mutant, the region corresponding to most of the dimerization helix in the C-terminal domain is no longer helical.)11

Modeling the C-terminal domain dimer at the interface of pentameric and hexameric capsid rings

Given that our data demonstrate that the subunit orientation of the C-terminal domains within the dimer is the same in wild-type CAFL and the NMR structure of CA144-231 (PDB id 2KOD),17 and that this orientation is fully consistent with the packing of hexameric rings of N-terminal domains in tubes of HIV-1 capsid as seen by cryo-electron microscopy,17 the question arises as to whether the same C-terminal domain dimer orientation is consistent with the connection of pentameric to hexameric rings of N-terminal domains. Previously,7 it had been suggested that the latter connection required the dimeric C-terminal domain subunit orientation observed in the crystal structure of the CA146-231 construct (PDB id 1A4315,16). However, the fact that the conformational space sampled by the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain dimer is quite large (Figure 6A) and generated solely by conformational flexibility of four linker residues extending from residue 146–149, it seems likely that the orientation of the C-terminal domains within the CAFL dimer observed here should also be compatible with the pentamer-hexamer connection. To test this hypothesis we took the coordinates for the full HIV-1 fullerene cone capsid model7 based on the crystal structures of pentamer7 and hexamer rings,11 and generated a set of starting coordinates comprising a pentamer of CAFL dimers in which the inner N-terminal domains take the pentamer structure and the outer N-terminal domains are each members of different hexamers. The results of constrained optimization (see Materials and Methods) in which the C-terminal domain dimer is strongly biased towards the orientation seen in the NMR structure of CA144-23117 are shown in Figures 9A and B. The Cα rms difference between the resulting C-terminal domain dimer and the CA144-231 NMR structure17 is ~0.3 Å, and the torsion angles for the linker lie within the allowed region of the Ramachandran map.

Thus we conclude that the orientation of the C-terminal domain subunits within the dimer found in the wild-type CAFL dimer reported here and in the NMR structure of the CA144-231 construct17 is fully consistent with the model of a capsid fullerene cone7 and that intrinsic curvature of the capsid lattice arises largely from variations in the orientation of the N-terminal domain relative to the C-terminal domain dimer, rather than any intrinsic configurational heterogeneity in the C-terminal domain dimer. This is also consistent with a recent cryo-electron microscopy and molecular dynamics simulation study of capsid tubes which suggested that variations in crossing angle for the dimerization helix of the C-terminal domain are confined within a limited range of ±10 degrees.4

A comparison of the orientations of the N-terminal domain within the pentamer and hexamer with the ensemble of orientations of the N-terminal domain in the wild type CAFL dimer is shown in Fig. 9C. The orientation in the pentamer is very similar to that of one of the CAFL clusters (cluster 6) whose population is sampled at around the 5% level. Although the orientation seen in the hexamer depicted in Figure 9C is actually less populated (<2%) within the CAFL ensemble, the exact orientation of the N-terminal domain to C-terminal domain dimer in a hexameric lattice is dependent upon location in the fullerene cone. Thus, assembly of both hexamers and pentamers very likely proceed via conformational selection involving states that are only sparsely-populated in the CAFL dimer. This would account for the fact that under the conditions used here (protein concentration ~0.05–0.2 mM, 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.5), wild type CAFL exhibits a pure monomer-dimer equilibrium with no evidence for the presence of higher order oligomers. Indeed, under physiological salt conditions the capsid assembly rate is close to zero, but is speeded up by many orders of magnitude by addition of high levels of crowding agents that mimic the cellular environment.60 The latter effectively increases the local concentration of CAFL, thereby increasing the population of the dimer species as well as the concentration of assembly-active conformers in which the relative orientations of the N- to C-terminal domains in the CAFL dimers are close to those in the assembled virion, and may also shift the distribution of the N-terminal domain ensemble towards assembly-active conformers through interactions with the crowding agent.

Concluding remarks

In summary, the wild-type HIV-1 capsid protein, CAFL, exists in a dynamic monomer-dimer equilibrium. The structure of the full-length CAFL dimer is characterized by a single orientation of the C-terminal domains that coincides with that previously seen in the NMR structure of CA144-23117 and contrasts to that observed in the crystal structure of CA146-231.15,16 The relative N- to C-terminal domain orientations encompass a diverse distribution of states that differ significantly in monomeric and dimeric forms. Further, the orientations in the HIV-1 capsid cone assembly are present at small populations in the dimer distribution, but are absent in the monomer. Importantly, even though the structural ensembles reported here encompass a large number of degrees of freedom, they are validated by fits against concentration-dependent RDC and SAXS/WAXS data. The detailed structural description of this system is complicated not only by the diversity of the observed relative N- to C-terminal domain geometries, but also by the fact that the system exists as a mixture of inter-converting dimers and monomers, which requires both a combination of NMR and SAXS/WAXS experimental data and a novel computational apparatus for the structural fit. The approach described should be generally applicable to many other challenging real-world systems that currently escape structural characterization by standard application of mainstream techniques of structural biology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Vincenzo Venditti, Marvin Bayro and Mengli Cai for useful discussions, Rob Tycko for generously giving us the full length capsid DNA, Dan Garrett for technical support, and Mark Yeager (Scripps Research Institute) for providing the fullerene cone model coordinates. Use of the Advanced Photon Source (D.O.E. W-31-109-ENG-38) and the shared scattering beamline resource (PUP-77 agreement between NCI, NIH and Argonne National Laboratory) is acknowledged. This work was supported by funds from the Intramural Program of the NIH, NIDDK (G.M.C.) and CIT (C.D.S.), and from the Intramural AIDS Targeted Antiviral Program of the Office of the Director of the NIH (to G.M.C.).

Footnotes

Supporting information: This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Hanke T, McMichael AJ. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:3390–3393. doi: 10.1002/eji.201190072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dahirel V, Shekhar K, Pereyra F, Miura T, Artyomov M, Talsania S, Allen TM, Altfeld M, Carrington M, Irvine DJ, Walker BD, Chakraborty AK. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11530–11535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105315108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeager M. J Mol Biol. 2011;410:534–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao G, Perilla JR, Yufenyuy EL, Meng X, Chen B, Ning J, Ahn J, Gronenborn AM, Schulten K, Aiken C, Zhang P. Nature. 2013;497:643–646. doi: 10.1038/nature12162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganser BK, Li S, Klishko VY, Finch JT, Sundquist WI. Science. 1999;283:80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5398.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganser-Pornillos BK, von Schwedler UK, Stray KM, Aiken C, Sundquist WI. J Virol. 2004;78:2545–2552. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2545-2552.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Yeager M. Nature. 2011;469:424–427. doi: 10.1038/nature09640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borsetti A, Ohagen A, Gottlinger HG. J Virol. 1998;72:9313–9317. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9313-9317.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Accola MA, Strack B, Gottlinger HG. J Virol. 2000;74:5395–5402. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.12.5395-5402.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du S, Betts L, Yang R, Shi H, Concel J, Ahn J, Aiken C, Zhang P, Yeh JI. J Mol Biol. 2011;406:371–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pornillos O, Ganser-Pornillos BK, Kelly BN, Hua Y, Whitby FG, Stout CD, Sundquist WI, Hill CP, Yeager M. Cell. 2009;137:1282–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monaco-Malbet S, Berthet-Colominas C, Novelli A, Battai N, Piga N, Cheynet V, Mallet F, Cusack S. Structure. 2000;8:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00507-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin R, Tzou YM, Krishna NR. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9457–9467. doi: 10.1021/bi2011493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gitti RK, Lee BM, Walker J, Summers MF, Yoo S, Sundquist WI. Science. 1996;273:231–235. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamble TR, Yoo S, Vajdos FF, von Schwedler UK, Worthylake DK, Wang H, McCutcheon JP, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Science. 1997;278:849–853. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Worthylake DK, Wang H, Yoo S, Sundquist WI, Hill CP. Acta Cryst Section D. 1999;55:85–92. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998007689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byeon IJ, Meng X, Jung J, Zhao G, Yang R, Ahn J, Shi J, Concel J, Aiken C, Zhang P, Gronenborn AM. Cell. 2009;139:780–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zweckstetter M, Bax A. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:3791–3792. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang JR, Grzesiek S. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:694–705. doi: 10.1021/ja907974m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwieters CD, Suh JY, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Takayama Y, Clore GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:13026–13045. doi: 10.1021/ja105485b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takayama Y, Schwieters CD, Grishaev A, Ghirlando R, Clore GM. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:424–427. doi: 10.1021/ja109866w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuck P. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao H, Ghirlando R, Piszczek G, Curth U, Brautigam CA, Schuck P. Anal Biochem. 2013;437:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2013.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole JL, Lary JW, TPM, Laue TM. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;84:143–179. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)84006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brautigam CA. Methods. 2011;54:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schuck P. Analytical Biochem. 2003;320:104–124. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhao H, Brown PH, Schuck P. Biophys J. 2011;100:2309–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghirlando R. Methods. 2011;54:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson ML, Straume M. In: Modern Analytical Ultracentifugation. Schuster TM, Laue TM, editors. Birkhaüser; Boston: 1994. pp. 37–65. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clore GM, Starich MR, Gronenborn AM. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:10571–10572. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen MR, Mueller L, Pardi A. Nature Struct Biol. 1998;5:1065–1074. doi: 10.1038/4176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King V, Parker M, Howard KP. J Magn Reson. 2000;142:177–182. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 1995;6:277–293. doi: 10.1007/BF00197809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vranken WF, Boucher W, Stevens TJ, Fogh RH, Pajon A, Llinas M, Ulrich EL, Markley JL, Ionides J, Laue ED. Proteins. 2005;59:687–696. doi: 10.1002/prot.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riek R, Pervushin K, Wuthrich K. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:462–468. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clore GM, Gronenborn AM. Trends Biotech. 1998;16:22–34. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fitzkee NC, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 2010;48:65–70. doi: 10.1007/s10858-010-9441-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Clore GM. Progr Nucl Magn Reson Spectros. 2006;48:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakomek NA, Ying J, Bax A. J Biomol NMR. 2012;53:209–221. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9626-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. J Magn Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nilges M. Proteins. 1993;17:297–309. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hendrickson WA. Meth Enzymol. 1985;115:252–270. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(85)15021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bermejo GA, Clore GM, Schwieters CD. Protein Sci. 2012;21:1824–1836. doi: 10.1002/pro.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]