Abstract

Recent interest in the development of surfactant-based nano delivery systems targeting tumor sites has sparked our curiosity to understand the detailed mechanism of the self-assembly and phase transitions of pH-sensitive surfactants. Towards this goal we applied a state-of-the-art simulation technique, continuous constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) with the hybrid-solvent scheme and pH-based replica-exchange protocol, to study de novo self-assembly of 30 and 40 lauric acids, a simple model titratable surfactant. We observed the formation of a gel-state bilayer at low and intermediate pH and a spherical micelle at high pH, with the phase transition starting at 20–30% ionization and completing at 50%. The degree of cooperativity for the transition increases from the 30-mer to the 40-mer. The calculated apparent or bulk pKa value is 7.0 for the 30-mer and 7.5 for the 40-mer. Congruent with experiment, these data demonstrate that CpHMD is capable of accurately modeling large conformational transitions of surfactant systems while allowing simultaneous proton titration of constituent molecules. We suggest that CpHMD simulations may become a useful tool to aid in the design and development of pH-sensitive nanocarriers for a variety of biomedical and technological applications.

1 Introduction

A major area of nanomedicine focuses on the development of nanocarriers that target specific malignant cells for delivery of drugs, genes, imaging tools, and diagnostic sensors.1 Targeted drug delivery has the advantage of significantly higher activity and reduced cyto-toxicity. With numerous FDA-approved clinical applications, liposomes hold great promise as a class of versatile delivery systems.2 A particular area of interest is the design of liposomes as nanocarriers for cancer treatment. Since tumors and other sites of immune activity have localized acidic pH,3, 4 pH-sensitive liposomes have been developed,5, 6 which can release encapsulated drugs or other therapeutic agents by undergoing pH-dependent destabilization of the liposomal membrane.2 The mechanistic details of such processes remain to be elucidated.

A simple class of pH-sensitive surfactants is the fatty acid with a single unbranched hydrocarbon tail and a carboxylic headgroup (CH3-(CH2)n-COOH). It has been long known that fatty acids form vesicles or liposomes near the apparent pKa value, where the protonated and deprotonated forms exist in similar fractions, while at pH conditions where the anionic form dominates, they exist in micelles.7–9 Namani and Walde showed that the vesicle formation pH for decanoic acids (C10 fatty acids) can be tuned by addition of ionic co-surfactants such as dodecylbenzenesulfonate. 10 Most recently, de la Cruz group demonstrated that the morphology of vesicles formed by mixtures of palmitic acids (C16 fatty acids) and peptide amphiphiles with the same hydrocarbon tail can be regulated by pH.11

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer valuable insights into the atomic-level interactions that are difficult or impossible to probe experimentally. In the last decade, the revolution of computing power has allowed all-atom MD to be applied to directly simulate micellization of surfactants. In a pioneering work, Marrink and coworkers demonstrated the spontaneous aggregation of 54 dodecylphosphocholine molecules into a worm-like (0.46 M) or spherical (0.12 M) micelle.12 Recently, starting from 400 randomly distributed sodium dodecyl sulfate molecules with a concentration of 0.7 M, Sammalkorpi and coworkers examined the effects of type and concentration of excess salt on the size and structure of the micelle.13 MD simulations have also been applied to study the self-assembly of ionized fatty acids, such as octanoate (C8 fatty acid)14 and laurate (C12 fatty acid) as well as oleate (C18 fatty acid with a double bond).15 One aspect that has been missing in all simulation work published so far (except for our recent work,16 see below) is the effect of pH, which, as discussed earlier, plays an important role in controlling the phase and morphological behavior of ionizable surfactants. To mimic the change in pH, one approach is to run multiple simulations with varying ratios of protonated and deprotonated molecules.17 The accuracy of such an approach is however questionable because of the ambiguity in combining protonated and deprotonated configurations. Furthermore, the pH condition for phase or morphological transitions as well as the apparent pKa of the system can not be determined.

The continuous constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) technique, however, is capable of representing both protonated and deprotonated states in an MD simulation, by using a set of titration coordinates that are coupled to, and propagated simultaneously with, the atomic coordinates.18–21 CpHMD allows the protonation state of a titratable site to change in response to the change in local environments during dynamics, thus unlocking the ability to model pH-dependent self-assembly. While the CpHMD technique was originally designed for simulations with the generalized Born (GB) implicit-solvent model,18, 19 we recently developed a hybrid-solvent CpHMD which models the conformational dynamics in explicit solvent while calculating the solvation forces on the titration coordinates based on the GB model.20

Used together with a pH-based replica exchange (pH-REX) protocol, hybrid-solvent CpHMD offers more accurate pKa prediction as compared to the GB-based CpHMD with 1 ns sampling time per replica for proteins.20 The ability to propagate conformational dynamics in explicit solvent also allows it to be applied to study proton titration of surfactants, as our previous work showed the GB model resulted in overly-compact micelles. Hybrid-solvent CpHMD gives quantitative prediction of the pKa shift of a lauric acid in ionic and non-ionic micelles.22 Most recently, we demonstrated the first constant pH molecular dynamics simulation of the self-assembly of 20 lauric acid molecules, finding a micelle at high pH and a bilayer at low pH, with the transition between the two phases occurring near the apparent pKa of 7.0.16 This was a promising result, as it for the first time reproduced the pH-dependence observed in experiments, and the predicted pKa of 7.0 is in good agreement with the experimental value of 7.5.23 However, the aggregate size of 20 molecules is much smaller than the experimental aggregation number of 55–70 for sodium laurate micelles.24 Thus, the objective of this work is to extend the pilot study by simulating systems comprising 30 and 40 lauric acids in order to further assess the capability of the CpHMD technique in modeling pH-dependent self-assembly and phase transitions of surfactants. The data reproduce the pH-induced transition from a gel-state bilayer to a micelle and offer an opportunity to examine the various details related to the phase transition. Finally, we will present the simulation of 8-carbon octanoic acids to explore the effect of hydrocarbon chain length on the self-assembly. This work sets the stage for atomistic simulation studies of pH-dependent dynamics of lipids and surfactants.

2 Methods and Simulation Details

Methods

The study presented here is based on the continuous constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) simulations,18–20, 25 in which the protonation states of titratable sites are represented by a set of fictitious λ coordinates26 propagated simultaneously with the atomic coordinates. The partial charges on the titratable sites and van der Waals interactions involving titratable protons are scaled based on the λ coordinates, thus coupling proton titration with conformational dynamics. The hybrid-solvent CpHMD used here takes advantage of the explicit water models for more accurate sampling of conformational states and the GB model for efficient propagation of λ coordinates.20 To enhance sampling in the coupled conformational and protonation space and accelerate convergence, a pH-based replica exchange (pH-REX) protocol is used.20

Force fields and parameters

The CHARMM27 lipid force field27 was used to represent the hydrocarbon chain of the fatty acid, while the CHARMM22 protein force field was used to represent the protonated and unprotonated forms of the carboxylic headgroup.28 The CHARMM modified TIP3P water model was used. The GBSW model29 was used for the calculation of solvation forces on the titration coordinates, with the atomic input radii derived in our previous work.30 The surface tension term was set to zero. Unless otherwise specified, the ionic strength was set to zero. All other GBSW-related parameters were set to the default values. The potential of mean force for titrating a single lauric acid in solution (model compound) was determined previously.22 The model compound pKa was 5.0, which is the experimental pKa of dilute lauric acid solution.31 The same parameters and model pKa were used for fatty acids with C8 chains (octanoic acids).

Simulation protocol

The hybrid-solvent CpHMD simulations with pH-REX were performed using CHARMM version c36b1.32 The fatty acids were initially randomly distributed in a cubic simulation box with a minimum distance of 5 Å between molecules. The edge length of the box was 50 Å for the lauric acid systems and 40 Å for the octanoic acid systems. The system was solvated with water molecules; 3590, 3437, 1850, and 1747 waters were used for the systems containing 30 lauric acids, 40 lauric acids, 20 octanoic acids, and 30 octanoic acids, respectively. The solvated systems were then subjected to 50 steps of steepest descent and 150 steps of adopted-basis Newton-Raphson energy minimization before starting the pH-REX CpHMD simulation. In the pH-REX protocol, 11 replicas were used, which occupied a pH ladder of 4–9 with spacing of 0.5 unit. Every 500 time steps, or 1 ps, an exchange in pH conditions between replicas with adjacent pH was attempted according to the Metropolis criterion.20 Each replica underwent molecular dynamics according to the NPT ensemble at 300 K and 1 atm via the Hoover thermostat33 and Langevin piston pressure coupling algorithm.34 The integration time step was 2 fs as the length of bonds involving hydrogen was constrained using the SHAKE algorithm. The van der Waals interactions were smoothed to zero via a switching function between 10 and 12 Å. The particle-mesh Ewald (PME) method was used to calculate long-range electrostatic interactions in the conformational sampling. The PME calculation employed a real space cutoff of 12 Å and a sixth-order B-spline interpolation. FFT and κ were set to 64 and 0.34 Å−1, respectively.

We did not include counterions in the simulation box because a fixed number of counter ions can not fully compensate the total net charge of the system at all pH conditions. Nevertheless, possible effects of the counterions were explored in a test simulation with the 20-mer.16 We found that while the dielectric screening results in a small decrease of the apparent pKa value and the transition pH, the presence of explicit ions slightly distorts the bilayer structure.16 Development of a rigorous way to include counterions is a topic addressed by our newly developed all-atom CpHMD technique, which utilizes titratable co-ions21 or water molecules35 to enable charge neutrality of the system. We are currently assessing its suitability for modeling pH-dependent surfactant dynamics.

3 Results and Discussion

Lauric acids self-assemble into a single aggregate

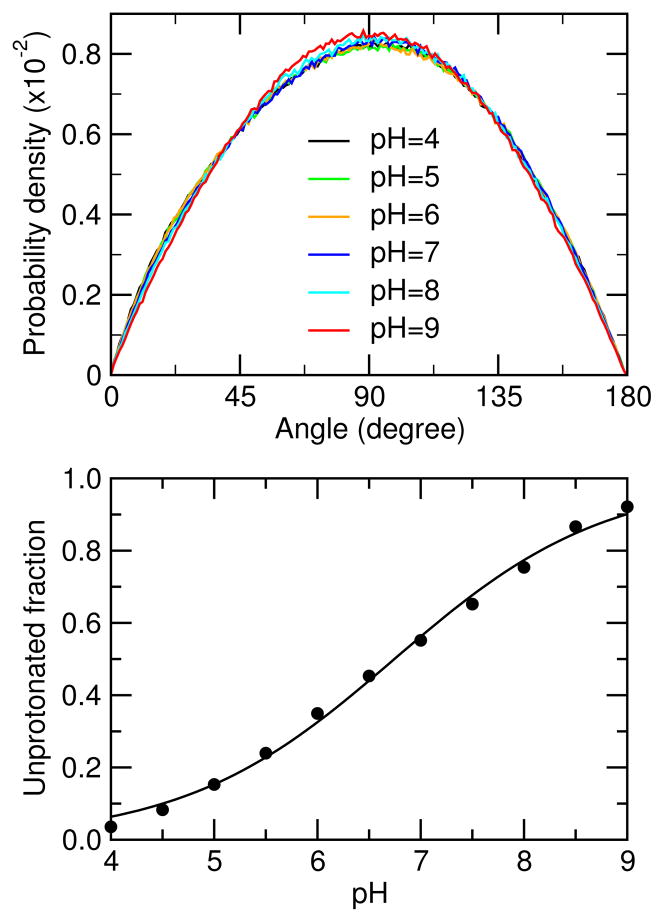

Initially lauric acids were randomly distributed in a simulation box. The simulation of each pH replica lasted 50 ns for the 30-mer and 90 ns for the 40-mer. Within 10 ns, one aggregate was formed in all replicas but one where two aggregates persisted until they merged at about 40 ns. The protonation-state sampling in the simulation is well converged, as evident from the nearly constant value of the unprotonated fraction (see Figure 1 top for the 40-mer system). The behavior of the 30-mer system is similar and not shown here. We also examined the details of the replica-exchange behavior. Figure 1 bottom shows that all replicas undergo multiple walk-throughs of the entire pH ladder. The average exchange ratio for the 30- and 40-mer systems is about 22%. These data indicate that the REX protocol employed here was at an adequate efficiency for enhancing the sampling of the coupled protonation and conformational space.

Figure 1.

Top. Cumulative unprotonated fraction of the 40-mer system at all pH values as a function of simulation time. Only the last 20 ns is shown. 1 ps is equivalent to 1 exchange step. Bottom. All replicas walk through the entire pH ladder. For clarity the pH conditions visited by two randomly chosen replicas as a function of time are shown.

Figures 2 shows representative snapshots of the 40-mer system at pH 4 (left panel) and pH 9 (right panel). The same behavior is seen as in the 20-mer system.16 A bilayer was formed with a significant degree of interdigitation at pH 4 and a spherical micelle was formed at pH 9. Note that, despite running for 90 ns per replica, the formation of the bilayer was slightly incomplete for the 40-mer system, as evidenced by the two monomers lying parallel to the plane of the bottom leaflet (Figure 2 left). However, the small fraction (5%) does not change the apparent pKa and transition pH, or the qualitative picture emerging from this study.

Figure 2.

Representative snapshots of the 40-mer at pH 4 (left) and pH 9 (right) in the simulation box. Alkyl tails are shown in cyan, while the protonated and unprotonated headgroups are represented by blue and red beads, respectively. For clarity water is not shown.

Formation of a gel-state bilayer under low and intermediate pH conditions

To provide a quantitative characterization of the aggregate morphology, we calculate the distribution of the relative orientation between two surfactants, defined as the angle between two C1-C12 vectors. The shape of the angle distribution differentiates bilayer from micelle. At pH 4, when all lauric acids are protonated and neutral (see later discussion), the angle distribution is bimodal with symmetric peaks near 0° and 180° (Figure 3), indicating a preferential parallel/antiparallel arrangement of the alkyl chains and the presence of bilayer for both the 30-mer and 40-mer. As expected, the bilayer shape becomes more regular with the increasing number of lauric acids, as seen from the heightened peaks when comparing the distributions of the 20-mer,16 30-mer and 40-mer. Note that there is a small bump at 90° in the 40-mer (Figure 3 bottom), which is caused by the two lauric acids that are not incorporated in the bilayer, with the tails perpendicular to the rest of the molecules (see Figure 2 left). As pH increases to 6 for the 30-mer and 7 for the 40-mer, the intensity of the two peaks decreases significantly and the probability density for the angles between 45 and 135° increases, which indicates that the bilayer becomes disordered. At pH 7–7.5, the peaks disappear, which indicates the loss of the bilayer character.

Figure 3.

Distribution of the angle between two surfactants in the 30- (top) and 40-mer (bottom) systems. For clarity only the integer pH conditions are shown with the exception of pH 6.5 and 7.5 displayed as dashed orange and blue curves for the 40-mer. Magenta curve represents the distribution obtained from the simulation of a spherical micelle comprising 60 laurate ions.

To examine the conformation of the lauric acids in the bilayer, we plot the probability distribution of the alkyl-chain length, defined as the C1-C12 distance (Figure 4 top). An identical bimodal distribution is seen for the 30- and 40-mer, which has a narrow peak at 14 Å and a second peak at 13 Å with a tail extending to 10 Å. Thus, the lauric acids spend the majority of the time in fully stretched configurations, which suggests that the bilayer may be in a solid gel phase (see more discussion later). Interestingly, the intensity of the narrow peak is increased in the 30- and 40-mer relative to the 20-mer studied by us previously (see data in Ref16), which is the result of increased ordering of the bilayer in the larger bilayers due to the decrease fraction of solvent-exposed alkyl chains. With the increase in aggregate size, the bilayer also exhibits a lesser degree of interdigitation, which can be quantified by the fractional overlap, defined as (2*L−T)/L, where L represents the average monomer length (distance between the C1 and C12 atoms in both leaflets) and T represents the average bilayer thickness (distance between the C1 atoms of the upper and lower leaflets). As seen in Figure 5, the fractional overlap is decreased from about 90% for the 30-mer to about 85% for the 40-mer, consistent with the fractional overlap of about 78% for vesicles of undecenoic acid (10-carbon fatty acid with a terminal double bond).36

Figure 4.

Probability distribution of the alkyl-chain length (defined as the C1-C12 distance) in the bilayer (top) and micelle (bottom). The 30- and 40-mers are displayed in red and blue, respectively. The dash black curve represents the cumulative probability (integration of the probability density). Since it is very similar for the two aggregates, only one curve is shown.

Figure 5.

Blue bars indicate the fractional overlap, which is defined as (2 * L − T)/L, where L represents the average monomer length (distance between the C1 and C12 atoms in both leaflets) and T represents the average bilayer thickness (distance between the C1 atoms of the upper and lower leaflets).

Formation of a spherical micelle under high pH conditions

As pH increases beyond 7, the angle distribution approaches that of a micelle comprising 60 fully charged laurate ions (magenta curve in Figure 3), which indicates that the shape of the aggregate becomes spherical. We compare the conformation of lauric acids in the micelle with those in the bilayer. The distribution of the alkyl-chain length remains bimodal with identical peak positions as in the bilayer (Figure 4 bottom). However, the height of the narrow peak is significantly decreased to slightly below that of the broad peak, indicating that the laurate ions are most of the time in the bent configurations in the micelle. Interestingly, the distributions for the micelle are similar to that of a single lauric acid in a bilayer of diethyl ester dimethyl ammonium, which is in the liquid phase at room temperature (data not shown). Thus, the increase in pH induces a solid-to-liquid phase transition, in agreement with experiment,7, 9 and reflects the fact that the simulation temperature (300 K) is below the melting temperatures of lauric acid (317 K) and 1:1 potassium hydrogen dilaurate (307 K), but above the critical micelle temperature of potassium laurate (below 273 K).7, 9

Titration behavior of the aggregate and individual molecules

Now we examine the macroscopic titration behavior of the aggregate and compare the calculated apparent pKa with experiment. The unprotonated fraction for all the lauric acids in the simulation box was calculated at each pH condition. The resulting titration data show that both the 30- and 40-mer aggregates are nearly completely protonated at pH 4 while at pH 9, the 30-mer is about 90% deprotonated and the 40-mer is 75% deprotonated (Figure 6, top). Fitting of the data to the Hill equation results in macroscopic or apparent pKa values of 7.0 and 7.5 for the 30- and 40-mers, respectively. The small Hill coefficient (0.33 for both aggregates) is a manifestation of negative cooperativity between the deprotonation events of the lauric acids. It is interesting to see that the pKa increases from 7.0 to 7.5 as the aggregate size is increased from 30 to 40, which is consistent with the observed increase in the apparent pKa of premicellar aggregates of fatty acids.23 The pKa of the 40-mer (7.5) is identical to the experimental value of 7.5 measured above the critical micelle concentration.23

Figure 6.

Top. Titration curves for the 30- and 40-mers. The fraction of laurate ions was calculated at each pH condition based on the last 20-ns data. Bottom. Calculated pKa values for the individual lauric acids in the 30-mer (red) and 40-mer (blue) aggregate. The dash lines represent the average pKa’s.

While the bulk or apparent pKa of the aggregate is the only observable in experiments, CpHMD simulation can also track proton titration of the individual lauric acids. We calculated the unprotonated fractions of the individual lauric acids, which are well converged during the simulation of both 30- and 40-mer aggregates (data not shown). Fitting of the unprotonated fractions to the Hill equation is excellent for all lauric acids in the aggregates. The resulting microscopic pKa’s cover a range of 6.7–7.2 for the 30-mer and 7.0–7.9 for the 40-mer (Figure 6, bottom). The Hill coefficients are in the range of 0.35–0.45. These data are consistent with the bulk titration data. The small Hill coefficients corroborate the fact that deprotonation of the individual lauric acids is highly coupled and negatively cooperative.

Transition between the bilayer and micelle

To further characterize the phase change as a function of pH, we computed an order parameter defined as,

| (1) |

where v⃗i is a normalized vector connecting the C12 and C1 atoms of the molecule i, and d⃗ is a normalized average vector of the unsigned orientations of all v⃗i. The P2 value reaches 1 when molecules are perfectly aligned, while it is small when different orientations are sampled. The control simulation of a prebuilt micelle comprising 60 laurate ions gave P2 of 0.4. Thus, the pH-induced phase transition can be investigated by calculating P2 at different pH conditions. Since P2 at a specific pH condition varies due to conformational flexibility of the aggregate (especially the micelle), histograms were constructed. The corresponding probabilities are converted to the relative free energies and plotted as a function of P2 and pH (Figure 7, top for the 30-mer and bottom for the 40-mer). There are two regions with low free energies, where P2 spans 0.8–1 and 0.3–0.6, representing the bilayer and micelle, respectively.

Figure 7.

Relative free energy (kcal/mol) as a function of P2 order parameter and pH for the 30-(top) and 40-mer (bottom).

Comparing the 40-mer with the 30-mer, it is seen that the bilayer-to-micelle transition (where both bilayer and micelle are seen) is shifted from pH 5.5–6.5 to a higher pH range, 6.5–7.0, as a result of the increase in the bulk as well as microscopic pKa values of lauric acids in the 40-mer (Figures 6). Interestingly, the bilayer-to-micelle transition is completed when only half of the lauric acids are ionized, i.e., at the bulk pKa value, 7.0 and 7.5 for the 30- and 40-mer, respectively. During the transition, the fraction of laurate ions increases from 20% to 40% for the 30-mer, and from 30% to 40% for the 40-mer. Thus, only partial deprotonation of the lauric acids is necessary for the formation of the micelle. Besides the shift in transition pH, the transition becomes more cooperative for the 40-mer, which may be the result of the increased hydrophobic attraction in the larger aggregate, which also explains why the bilayer of the 40-mer is more ordered (smaller variation in the P2 value) than the 30-mer (see Figure 3).

Transition states have one fully-formed leaflet

To further elucidate the mechanism of the bilayer-to-micelle transition, we examined the transition states of the 40-mer aggregate, defined as the configurations at the transition pH 6.5 that have the lowest probability of occurrence based on the free energy map (Figure 7, bottom). These states were identified to have 0.65 < P2 < 0.75 and account for a population of 7%. Note that the most stable micelle and bilayer have the P2 values of 0.5 and 0.9, respectively. The angle distribution of these transition structures shows two asymmetric peaks. The peak near 0° is much higher than the one near 180° (Figure 8 top), suggesting that the parallel arrangement is more preferred than the anti-parallel one. Visual inspection of the snapshots reveals the origin of the asymmetry. As seen in Figure 8 bottom, a large number of alkyl chains are aligned in the lower leaflet of the bilayer, and of these aligned molecules the majority of the headgroups are pointing down which corresponds to the peak near 0° in the angle distribution. There are fewer headgroups in the upper leaflet, resulting in a lower intensity for the peak near 180°. Furthermore, there are about 25% of the molecules in the upper leaflet that are not incorporated in the interdigitated bilayer. The presence of these molecules raises the valley, between 45° and 135°, in the angle distribution (Figure 8 top).

Figure 8.

Top. Distribution of the angles between two surfactants in the transition states of the 40-mer at pH 6.5. Bottom. Representative snapshot of a transition state. Colors are the same as in Figure 2.

Bilayer-to-micelle transition is driven by increased electrostatic repulsion among head-groups

To characterize the intermolecular interactions in the self-assembled structure, we computed the radial distribution function (RDF) between the carboxyl carbons in the 40-mer (Figure 9). At pH 4, where the lauric acids are all protonated, there is a broad maximum at 4.4–5.2 Å, reflecting the interactions among the protonated headgroups in the bilayer. At pH 5, 11% of the molecules become deprotonated, which results in the splitting of the maximum into a small, sharp peak at 4.3 Å and a broad shoulder at 4.5–5.2 Å. The sharp peak is due to the hydrogen-bonded pairs of carboxylic acid and laurate ion, which are more likely to form as compared to the condition of pH 4 (see Figure 9, bottom). The broad shoulder represents the non-hydrogen-bonded population of lauric acids and laurate ions. As pH is raised to 6 and 7, the fraction of laurate ions increases to 25% and 43%, respectively. Consequently, the intensity of the first peak increases due to the progressively greater probability of forming hydrogen bonds between lauric acids and laurate ions (see Figure 9, bottom). In fact, the average number of hydrogen bonds reaches a maximum at pH 6.5–7.5. The broad shoulder which is seen at pH 5 is lightly raised at pH 6 and it becomes a broad peak at pH 7 with the center of the maximum shifting from 5.1 to 5.5 Å. The latter reflects the emergence of a micellar structure where the carboxyl carbons are further apart as compared to the bilayer. The intensity of the first peak continues to grow and reaches a maximum at pH 7.5. This is because at pH 7.5, the populations of lauric acids and laurate ions are approximately equal (Figure 6), which results in the largest number of hydrogen bonds between the headgroups (see Figure 9, bottom). As the pH is further raised to 8 and 9, the position of the two peaks remains the same as at pH 7. However, the intensity of the first peak lowers while that of the second peak becomes higher, reflecting the decreasing number of hydrogen bonds and increasing number of laurate ions. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the increased spatial separation between the headgroups due to charge-charge repulsion drives the morphological change from bilayer to micelle. The decreasing number of hydrogen bonds with decreasing pH indicates that hydrogen bonding alone is not responsible for the formation of bilayer.

Figure 9.

Top. Radial distribution functions between carboxyl carbons in the 40-mer at indicated pH conditions. Plots are shifted vertically to facilitate visualization. Bottom. Average number of hydrogen bonds between laurate and lauric acid headgroups for the 40-mer at different pH conditions. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Octanoic acids form micelle only and have a lower apparent pKa

It has been known that the association of fatty acids occurs when the alkyl chain exceeds 8 carbons.7, 23 We performed simulation of the self-assembly of 20- and 30-mers of octanoic (or caprylic) acid, an eight-carbon fatty acid. Interestingly, a spherical micelle was observed in the entire pH range, from 4 to 9, irrespective of the protonation state of octanoic acids. (see angle distributions for the 20-mer, Figure 10 top). The micelle formation of octanoate molecules seen here is consistent with numerous experimental and simulation studies, which determined the aggregation number to be 17–24 (Ref37 and references therein). The lack of bilayer formation in the simulation may be explained by the decreased hydrophobic attraction between the C8 alkyl chains as compared to the C12 alkyl chains of lauric acid, and reinforces the notion that the balance between hydrophobic attraction and electrostatic repulsion determines the bilayer or micelle morphology. However, it contradicts the experimental observation of vesicles comprising partially protonated octanoic acids.7 We will come back to the possible cause for the discrepancy. The apparent pKa for the micelle is 6.8 for the 20-mer or 7.3 for the 30-mer (Figure 10 bottom), which is somewhat higher than the measured pKa of 6.5.23 Consistent with the lauric acid aggregates, the 30-mer of octanoic acid has a slightly lower Hill coefficient (0.32) as compared to the 20-mer (0.43), reflecting an increased degree of anti-cooperativity as a result of higher packing density.

Figure 10.

Top. Probability distribution of the angles between octanoic acids obtained from the simulation the self-assembled 20-mer. Data was collected from 15–30 ns for each pH replica. Bottom. Unprotonated fraction of octanoic acids at different pH conditions. Solid curve is the best fit of the data using the Hill equation.

4 Concluding Remarks

We have presented the pH-REX CpHMD simulations of de novo self-assembly of 30 and 40 lauric acids (12-carbon fatty acids), which are the minimalist model for titratable surfactants. In agreement with experiment8, 9 and our pilot study of the 20-mer system,16 the assembled structure shows a pH-dependent morphology, i.e., bilayer at low and intermediate pH conditions and micelle at high pH conditions. The bilayer is in a gel phase with untilted, interdigitated surfactants, in line with the experimental observation of crystals at room temperature and vesicles at 50°C.7–9 The observed interdigitation may be explained by the dominant hydrophobic attraction between protonated lauric acids under low acidic conditions, consistent with the observation that neutralizing charges induces interdigitation in the crystalline bilayer of amphiphiles with positively charged headgroups.11

Similar to the helix-coil transition of polymers where the degree of cooperativity increases with the number of monomer units,38 the bilayer-to-micelle transition becomes sharper for the 40-mer (pH 6.5–7.0) as compared to the 30-mer (pH 5.5–6.5). Interestingly, the transition is initiated at the pH condition where 20% (30-mer) or 30% (40-mer) of the surfactants become ionized and completes at 50% ionization, which is pH 7.0 for the 30-mer and 7.5 for the 40-mer. The latter is identical to the experimental value of 7.5 measured above the CMC condition for the lauric acid23 and presents a shift of 2.5 units relative to the solution pKa of unassociated lauric acids.

While our simulations reveal a micelle at pH conditions greater than the bulk pKa, experiments show vesicles/crystals (depending on temperature) persisting within about one unit above the pKa value.9 This discrepancy is likely due to the lack of ions in the hybrid-solvent CpHMD simulations. At half-ionization, the presence of ions will weaken the repulsion between the ionized headgroups, thereby stabilizing the bilayer morphology and shifting the transition pH higher relative to the pKa. There are two issues which make it difficult to properly account for the ionic effects in the hybrid-solvent CpHMD. First, the total net charge can not be compensated at all pH conditions with the same number of explicit ions. Second, since the titration coordinates are propagated with the GB implicit-solvent model, which utilizes an approximate function to account for Debye-Hückel screening, effects due to explicit ions are neglected. Nevertheless, our previous test simulations with 150 mM explicit salt ions showed that dielectric screening and explicit ions cause a small shift (within one pH unit) in the bulk pKa and transition pH as well as a small distortion of the bilayer structure.16 We expect the latter to go away as the system size increases. To rigorously incorporate explicit ions in CpHMD simulations, we recently developed the fully explicit-solvent CpHMD method21 with co-ions21 or titratable water molecules35 that can absorb the excess charge in the titrating system. Efforts are underway to test the new methodologies for surfactant systems.

The bilayer-to-micelle transition of the lauric acid assembly is caused by tipping of the balance between electrostatic repulsion among the headgroups and hydrophobic attraction among the tails. For surfactants with shorter alkyl chains, hydrophobic forces may not be sufficient to align the chains in a bilayer form. This may be the reason why in the simulation of the octanoic acids only a micelle is formed at all pH. However, the lack of bilayer formation of octanoic acids contradicts experiment, which showed vesicles at intermediate pH.7 There are two factors that may contribute to the inconsistency. First, the bilayer formation of fatty acids with shorter chains may require a larger number of monomers which are not present in the simulation. Second, the lack of dielectric screening by counter ions exaggerates the magnitude of electrostatic repulsion, thereby preventing the formation of bilayer. Efforts are being made to address these issues by using the all-atom CpHMD technique with explicit ions21, 35 and coarse-grained models to scale up the system (Morrow and Shen, work in progress). Despite the above-mentioned limitations, the presented results are encouraging and demonstrate that replica-exchange constant pH molecular dynamics is capable of modeling large, ionization-coupled conformational transitions for surfactant systems. We suggest that constant pH molecular dynamics may become a useful tool for aiding in the development of pH-sensitive nanocarriers for a variety of biomedical and technological applications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Procter & Gamble for a corporate gift. Support was also provided by National Institutes of Health (R01 GM098818) to JKS. Computing time was in part provided by the OU Supercomputing Center for Education and Research (OSCER) at the University of Oklahoma, as well as the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) at the University of Texas at Austin.

References

- 1.Wagner V, Dullaart A, Bock AK, Zweck A. The emerging nanomedicine landscape. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1211–1217. doi: 10.1038/nbt1006-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torchilin VP. Recent advances with liposomes as pharmaceutical carriers. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:145–160. doi: 10.1038/nrd1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lardner A. The effects of extracellular pH on immune function. J Leukocyte Biol. 2001;69:522–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:891–899. doi: 10.1038/nrc1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yatvin M, Kreutz W, Horwitz B, Shinitzky M. pH-sensitive liposomes: possible clinical implications. Science. 1980;210:1253–1255. doi: 10.1126/science.7434025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shi G, Guo W, Stephenson SM, Lee RJ. Efficient intracellular drug and gene delivery using folate receptor-targeted pH-sensitive liposomes composed of cationic/anionic lipid combinations. J Controlled Release. 2002;80:309–319. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hargreaves WR, Deamer DW. Liposomes from ionic, single-chain amphiphiles. Biochemistry. 1978;17:3759–3768. doi: 10.1021/bi00611a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cistola DP, Atkinson D, Hamilton JA, Small DM. Phase behavior and bilayer properties of fatty acids: hydrated 1:1 acid-soaps. Biochemistry. 1986;25:2804–2812. doi: 10.1021/bi00358a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cistola DP, Hamilton JA, Jackson D, Small DM. Ionization and phase behavior of fatty acids in water: application of the Gibbs phase rule. Biochemistry. 1988;27:1881–1888. doi: 10.1021/bi00406a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namani T, Walde P. From decanoate micelles to decanoic acid/dodecylbenzenesulfonate vesicles. Langmuir. 2005;21:6210–6219. doi: 10.1021/la047028z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leung CY, Palmer LC, Qiao BF, Kewalramani S, Sknepnek R, Newcomb CJ, Greenfield MA, Vernizi G, Stupp SI, Bedzyk MJ, Olvera de la Cruz M. Molecular crystallization controlled by pH regulates mesoscopic membrane morphology. ACS Nano. 2012;6:10901–10909. doi: 10.1021/nn304321w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marrink SJ, Tieleman DP, Mark AE. Molecular dynamics simulation of the kinetics of spontaneous micelle formation. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:12165–12173. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sammalkorpi M, Karttunen M, Haataja M. Ion surfactant aggregates in saline solutions: sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in the presence of excess sodium chloride (NaCl) or calcium chloride (CaCl2) J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:5863–5870. doi: 10.1021/jp901228v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Moura AF, Bernardino K, de Oliveira OV, Freitas LCG. Solvation of sodium octanoate micelles in concentrated urea solution studied by means of molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:14582–14590. doi: 10.1021/jp206657m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King DT, Warren DB, Pouton CW, Chalmers DK. Using molecular dynamics to study liquid phase behavior: simulations of the ternary sodium laurate/sodium oleate/water system. Langmuir. 2011;27:11381–11393. doi: 10.1021/la2022903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrow BH, Koenig PH, Shen JK. Atomistic simulations of pH-dependent self-assembly of micelle and bilayer from fatty acids. J Chem Phys. 2012;137:194902. doi: 10.1063/1.4766313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schuler LD, Walde P, Luisi PL, van Gunsteren WF. Molecular dynamics simulation of n-dodecyl phosphate aggregate structures. Eur Biophys J. 2001;30:330–343. doi: 10.1007/s002490100155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee MS, Salsbury FR, Jr, Brooks CL., III Constant-pH molecular dynamics using continuous titration coordinates. Proteins. 2004;56:738–752. doi: 10.1002/prot.20128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khandogin J, Brooks CL., III Constant pH molecular dynamics with proton tautomerism. Biophys J. 2005;89:141–157. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wallace JA, Shen JK. Continuous constant pH molecular dynamics in explicit solvent with pH-based replica exchange. J Chem Theory Comput. 2011;7:2617–2629. doi: 10.1021/ct200146j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wallace JA, Shen JK. Charge-leveling and proper treatment of long-range electrostatics in all-atom molecular dynamics at constant pH. J Chem Phys. 2012;137:184105. doi: 10.1063/1.4766352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrow BH, Wang Y, Wallace JA, Koenig PH, Shen JK. Simulating pH titration of a single surfactant in ionic and nonionic surfactant micelles. J Phys Chem B. 2011;115:14980–14990. doi: 10.1021/jp2062404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanicky JR, Shah DO. Effect of Premicellar Aggregation on the pKa of Fatty Acid Soap Solutions. Langmuir. 2003;19:2034–2038. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caponetti E, Martino DC, Floriano M, Triolo R. Fluorinated, protonated, and mixed surfactant solutions: a small-angle neutron scattering study. Langmuir. 1993;9:1193–1200. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khandogin J, Brooks CL., III Toward the accurate first-principles prediction of ionization equilibria in proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9363–9373. doi: 10.1021/bi060706r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong X, Brooks CL., III λ-dynamics: A new approach to free energy calculations. J Chem Phys. 1996;105:2414–2423. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feller SE, MacKerell AD., Jr An Improved Empirical Potential Energy Function for Molecular Simulations of Phospholipids. J Phys Chem B. 2000;104:7510–7515. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mackerell AD, Jr, Feig M, Brooks CL., III Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: Limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1400–1415. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Im W, Lee MS, Brooks CL., III Generalized Born model with a simple smoothing function. J Comput Chem. 2003;24:1691–1702. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Wallace JA, Koenig PH, Shen JK. Molecular dynamics simulations of ionic and nonionic surfactant micelles with a generalized Born implicit-solvent model. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:2348–2358. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palaprat G, Ganachaud F, Mauzac M, Hémery P. Cationic polymerization of 2,4,6,8-tetramethylcyclotetrasiloxane processed by tuning the pH of the miniemulsion. Polymer. 2005;46:11213–11218. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks BR, Brooks CL, III, Mackerell AD, Jr, Nilsson L, Petrella RJ, Roux B, Won Y, Archontis G, Bartles C, Boresch S, Caflisch A, Caves L, Cui Q, Dinner AR, Feig M, Fischer S, Gao J, Hodoscek M, Im W, Lazaridis KKT, Ma J, Ovchinnikov V, Paci E, Pastor RW, Post CB, Pu JZ, Schaefer M, Tidor B, Venable RM, Woodcock HL, Wu X, Yang W, York DM, Karplus M. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoover WG. Canonical dynamics: Equilibration phase-space distributions. Phys Rev A. 1985;31:1695–1697. doi: 10.1103/physreva.31.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feller SE, Zhang Y, Pastor RW, Brooks BR. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: The Langevin piston method. J Chem Phys. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen W, Wallace J, Yue Z, Shen J. Introducing Titratable Water to All-Atom Molecular Dynamics at ConstantpH. Biophys J. 2013;105:L15–L17. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee JH, Danino D, Raghavan SR. Polymerizable vesicles based on a single-tailed fatty acid surfactant: a simple route to robust nanocontainers. Langmuir. 2009;25:1566–1571. doi: 10.1021/la802373j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Moura AF, Freitas LCG. Molecular dynamics simulation of the sodium octanoate micelle in aqueous solution. Chem Phys Lett. 2005;411:474–478. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimm BH, Doty P, Iso K. Determination of the parameters for helix formation in poly–γ-benzyl-L-glutamate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1959;45:1601–1607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.45.11.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]