Abstract

This review describes the functions, structures, and mechanisms of nine nickel-containing enzymes: glyoxalase I, acireductone dioxygenase, urease, superoxide dismutase, [NiFe]-hydrogenase, carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, acetyl-coenzyme A synthase/decarbonylase, methyl-coenzyme M reductase, and lactate racemase. These enzymes catalyze their various chemistries by using metallocenters of diverse structures, including mononuclear nickel, dinuclear nickel, nickel-iron heterodinuclear sites, more complex nickel-containing clusters, and nickel-tetrapyrroles. Selected other enzymes are active with nickel, but the physiological relevance of this metal specificity is unclear. Additional nickel-containing proteins of undefined function have been identified.

Keywords: Nickel, Enzyme, Metallocenter, Catalytic mechanism, Protein structure

Introduction

Ni-containing enzymes play critical roles in bacteria, archaea, fungi, algae, and higher plants [1, 2]. This article summarizes the functions, structures, and mechanisms of nine Ni enzymes, progressing from three relatively simple, non-redox-active representatives (glyoxalase I, GlxI; acireductone dioxygenase, ARD; and urease), to a mononuclear, redox-active example (superoxide dismutase, SOD), to three heteronuclear cluster-containing enzymes ([NiFe]-hydrogenase; carbon monoxide dehydrogenase, CODH; and acetyl-coenzyme A synthase/decarbonylase, ACS), to proteins containing a Ni-tetrapyrrole (methyl-coenzyme M reductase, MCR, and its methane-oxidizing counterpart), to the newest representative (lactase racemase). In addition, we briefly summarize additional enzymes that are suggested to utilize Ni and explain how to identify true Ni enzymes.

Several of the Ni-dependent enzymes we describe require auxiliary proteins that participate in Ni delivery, metallocenter assembly, or organometallic cofactor synthesis [1, 3, 4]; however, this topic is only briefly considered here with key reviews highlighted. Furthermore, we avoid the ancillary issues of Ni uptake, Ni efflux, or Ni homeostasis systems [1, 5–7] along with the mechanisms used for Ni-dependent regulation [5, 8] or the multiple facets of Ni toxicity [9] that are important aspects of cellular Ni metabolism. The phylogenetic distribution of the various proteins involved in Ni metabolism, including Ni enzymes, has been assessed by comparative genomic analysis will not be covered here [10]. For each of these topics, interested readers are referred to the above citations. Hereafter, our focus is exclusively on catalysis by Ni enzymes.

Glyoxalase I

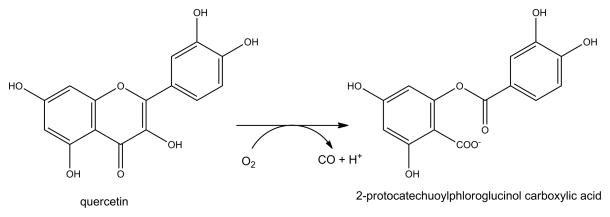

Two intermediates in the glycolysis pathway, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate, can undergo spontaneous reactions to form toxic methyglyoxal [11]. This reactive compound continuously modifies the proteome, where arginine residues are the primary target, and can also derivatize nucleic acids and other molecules. Therefore, cells need a mechanism to detoxify methylglyoxal to prevent damage to cellular components. A widely distributed, two-component enzyme system metabolizes methylglyoxal into non-toxic end products (Figure 1A). In a preliminary non-enzymatic step, methylglyoxal reacts with reduced glutathione (GSH) to form a hemithioacetal. The first enzyme in the detoxification pathway, glyoxalase I (GlxI) converts this species to S-D-lactoylglutathione. Finally, glyoxalase II (GlxII) hydrolyses this intermediate to lactate while regenerating reduced glutathione.

Fig. 1.

Glyoxalase I (GlxI). (A) GlxI acts on the reversibly-formed hemithioacetal product of glutathione (GSH) plus methylglyoxal, and catalyzes formation of S-D-lactoylglutathione via a cis-enediolate intermediate. The product is hydrolyzed by glyoxalase II (GlxII) to yield D-lactate. (B) Glx I structure and active site. The homodimeric protein (cyan and white cartoon view, PDB access code 1f9z, Escherichia coli) contains two Ni-containing active sites (green spheres) at the dimer interface with His and Glu ligands (sticks) contributed by each subunit and two coordinated waters (red spheres).

(2 column width)

GlxI contains an essential metal ion. The enzymes from humans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and Pseudomonas putida are zinc-dependent, with the structure of human GlxI revealing two mononuclear Zn2+ active sites at the dimer interface [12]. In contrast, the homologous GlxI from Escherichia coli is inactive with bound Zn2+ and maximally active in the presence of Ni2+ [13]. Significantly, the structures of the zinc-bound human enzyme and nickel-bound E. coli enzyme (Figure 1B) each exhibit octahedral coordination of their metals, with four amino acid side chains and two sites occupied by water molecules, while the inactive zinc-substituted E. coli GlxI has the metal coordinated in a trigonal bipyramidal manner with a single bound water molecule [14]. Thus, octahedral coordination of the metal appears to be necessary for GlxI activity from either source.

The reaction of GlxI is suggested to use an enediolate intermediate as shown in Figure 1A [13, 15, 16]; however, the structures of human and E. coli GlxI do not reveal an active site general base needed to generate this species. Two reasonable mechanistic proposals are consistent with the structural findings of native and metal-substituted forms of the human and bacterial enzymes. In one scenario, substrate displaces one or both metal-bound water ligands plus a Glu ligand; the displaced Glu then acts as a general base for proton abstraction from the hemithioacetal and as a general acid for reprotonation of the adjacent carbon to produce S-D-lactoylglutathione. This mechanism is supported by computational and spectroscopic studies of inhibitor-bound forms of the human [17, 18] and E. coli [19, 20] enzymes. A second plausible mechanism derived from X-ray absorption spectroscopy of the E. coli enzyme with bound product [20] postulates that substrate does not directly bind the metal; thus, the two water molecules remain bound to the metal and are available to facilitate the proton transfer reactions. Additional studies are needed to further decipher the role of the metal ion in catalysis by this enzyme.

Acireductone dioxygenase

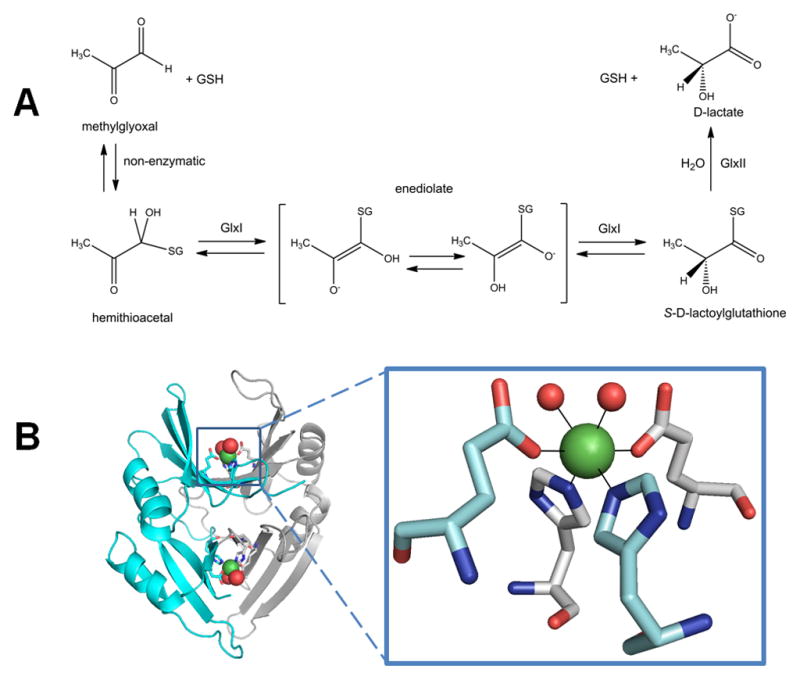

In addition to its well known function as a methyl donor, S-adenosylmethionine is decarboxylated and used as an aminopropyl donor for polyamine biosynthesis [21], and plants use S-adenosylmethionine to make aminocyclopropane carboxylate, a precursor to the hormone ethylene [22]. These reactions generate 5′-methylthioadenosine, the first compound in the ubiquitous methionine salvage pathway [23]. During methionine salvage, 5′-methylthioadenosine is converted through multiple steps to form 1,2-dihydroxy-3-keto-5-methylthiopentene, a substrate of the metalloenzyme acireductone dioxygenase (ARD). Much of what is known about the ARD mechanism has been determined by using enzyme isolated from the bacterium Klebsiella oxytoca. In the usual reaction, ARD converts 1,2-dihydroxy-3-keto-5-methylthiopentene and dioxygen to formate and 2-keto-4-methylthiobutanoate (left portion of Figure 2A), which can be transaminated to regenerate methioinine. In addition, the enzyme catalyzes an off-pathway shunt, and produces formic acid, CO, and 3-methylthiopropionate (right portion of Figure 2A). The products formed depend on which metal is bound to the enzyme, Fe2+ or Ni2+ [24, 25].

Fig. 2.

Acireductone dioxygenase (ARD). (A) The Fe-containing enzyme (left pathway) converts the substrate to formic acid and the keto-acid of Met, while the Ni-bound enzyme (right path) produces formic acid, CO, and 3-methylthiopropionate. (B) ARD structure and active site. The NMR structure of acireductone dioxygenase (white cartoon view, PDB access code 1zrr, Klebsiella oxytoca) is shown. The 6-coordinate Ni (green sphere) coordinates three His and one Glu (sticks), and two water molecules (red spheres). (C) Postulated reaction intermediates in the Fe- versus Ni-catalyzed reactions of ARD. Dioxygen and 1,2-dihydroxy-3-keto-5-methylthiopentene are thought to react at the ARD active site to form the metal-dependent cyclic peroxides shown. These rearrange, as shown by the arrows, to yield the appropriate products.

(2 column width)

The two forms of ARD use an identical polypeptide chain, yet early studies showed that the Ni and Fe forms of the protein can be separated by chromatography [24], indicating that they have somewhat different overall structures. Mg2+, Co2+, and Mn2+ can also be substituted into ARD yielding varying degrees of activity. The ability of alternative metal ions with such diverse redox potentials to be active in ARD, coupled with the fact that the non-enzymatic 2-keto-4-methylthiobutanoate forming reaction proceeds at a significant rate, implies that the metal is not an activator of O2, but serves to orient the substrate for direct reaction with O2 [26]. The precise differences between the two forms of ARD were disclosed by NMR models of the Ni enzyme (Figure 2B, left) and subsequent spectroscopic studies on wild-type and site-directed variant proteins [27–30]. No crystallographic structure exists for ARD, but a structure is reported for a mouse homolog where the identity of the metal is unknown [25]. ARD belongs to a diverse superfamily known as cupins, which contain a conserved “jelly roll” motif. The Fe form of ARD has a structure identical to the apoprotein form of the enzyme, while Ni-ARD has subtle structural differences. The metals are bound to a 3-His-1-carboxylate motif (Figure 2B, right). Significantly, binding of Fe2+ leads to a disordered C-terminus, and increased order at the N-terminus relative to that found in the Ni2+-bound ARD. These changes are propagated through the protein to produce subtle differences in the active site.

In one proposed mechanism, the Ni or Fe metallocenter of ARD binds the dianion form of the substrate, but as different tautomers [29]. A single electron transfer from substrate to O2 yields a superoxide intermediate that forms distinct cyclic peroxide adducts depending on the metal ion (Figure 2C). From this point, metal-specific rearrangement reactions yield the appropriate products. Additional model compound studies support this mechanism [31, 32]. An alternative proposal to this differential chelate model invokes different hydration states for the Ni and Fe species [33]. Crystallography of the Ni- and Fe-containing forms of ARD with bound substrates will be required to confirm or modify the proposed mechanisms.

Urease

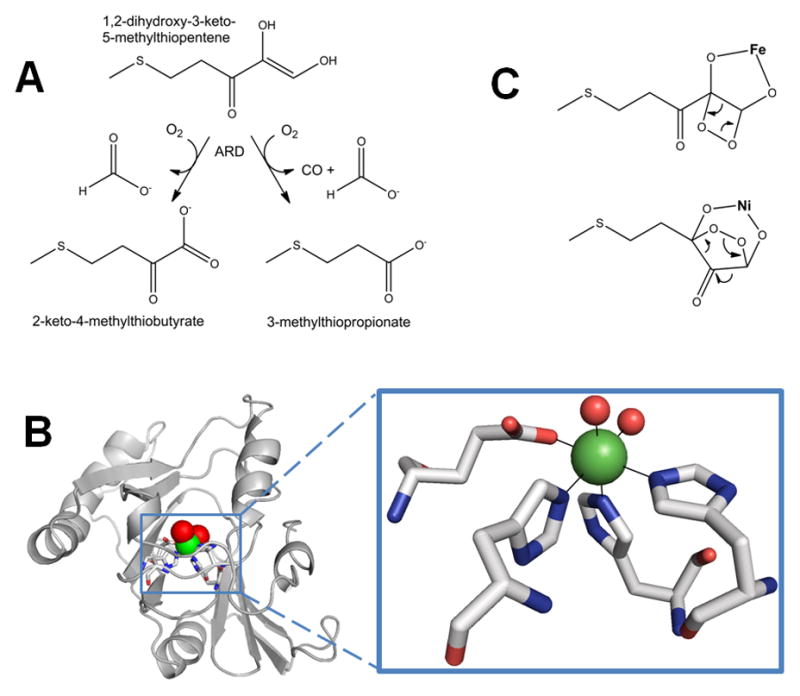

Urease, an enzyme found in selected bacteria, archaea, plants, algae, and fungi, catalyzes the seemingly simple hydrolysis of urea into ammonia and carbamic acid which spontaneously decomposes into another molecule of ammonia and carbonic acid (Figure 3A) [34–37]. The increase in ammonia concentrations and subsequent rise in pH resulting from urease catalysis has medical and agricultural implications [38, 39]. In many pathogenic bacteria, urease acts as a virulence factor associated with urinary stone formation, pyelonephritis, ammonia encephalopathy, and hepatic coma [40, 41]. In addition, Helicobacter pylori takes advantage of the pH increase from urea hydrolysis to colonize the acidic stomach environment [42–44]. In agriculture, urease is involved in cycling various nitrogen compounds, most notably urea-based fertilizers [39]. It also plays a role in seed germination by degrading the urea formed by arginase activity [45, 46].

Fig. 3.

Urease. (A) The reaction catalyzed by urease. (B) Urease structure and active site. The detailed architectures differ for different ureases, but all include a trimeric configuration of 1, 2, or 3 subunits. The urease shown (cartoon view, PDB access code 1fwj, Klebsiella aerogenes) possesses three subunits in uniform color (cyan, yellow, or white). Each active site contains two Ni (green spheres) that are bridged by a Lys carbamate and a water, with each Ni also binding a terminal water and two His, plus an Asp coordinating to one metal (side chains as sticks and solvent as red spheres). (C) Four reaction mechanisms proposed for urease. Proposals for urease catalysis are unified by having the urea carbonyl oxygen coordinated to Ni-1. (i) Hydroxide bound to Ni-2 attacks the urea carbonyl carbon to form a tetrahedral intermediate that decomposes with a nearby His residue functioning as a general acid. (ii) The bridging hydroxide attacks the urea carbonyl carbon while transferring its proton to product ammonia, with the other urea amine coordinated to Ni-2. (iii) The bridging hydroxide attacks the urea carbonyl carbon to form a tetrahedral intermediate that decomposes with a nearby His residue functioning as a general acid. (iv) A general base (perhaps Ni-2 coordinated hydroxide as shown) abstracts a urea proton leading to elimination of ammonia and production of cyanate that is subsequently hydrated.

(2 column width)

Ureases share a basic trimeric structure with three dinuclear catalytic sites and essentially identical folds, despite having variations in their quaternary structures [47–51]. Many bacterial ureases, such as the well-studied enzymes from Klebsiella aerogenes or Sporosarcina (formerly Bacillus) pasteurii, contain three subunits, UreA, UreB, and UreC, which form a trimer containing one catalytic center (located within UreC) [47, 50]. Three of those trimers come together to form the characteristic trimer (Figure 3B, left). In Helicobacter species, fungi, and plants, two or three of the subunits are fused and the overall architecture is dodecameric or hexameric [48, 49, 51].

The urease active site (Figure 3B, right) contains two Ni2+ atoms bridged by a carbamylated lysine residue and a water molecule [47, 52, 53]. Each Ni2+ is also coordinated by a terminal water and two His residues, finally one Ni2+ is also coordinated by an Asp. Assembly of this active site is a complex process involving four accessory proteins in most bacterial systems [54]. There is also evidence that plant and fungal ureases require accessory proteins for activation [34, 36, 46].

Four general mechanisms for urease have been proposed (Figure 3C). Long before the initial urease crystal structure was available [47], a mechanism involving two Ni2+ with distinct functions was proposed (i) [55]. Here, the carbonyl oxygen of urea displaces a terminal water and binds to Ni-1. The terminal water molecule bound to Ni-2 attacks the carbonyl carbon of urea, forming a tetrahedral intermediate that decomposes with the aid of a general acid. The crystal structure readily accommodated this mechanism with a nearby His residue serving as the general acid. A second mechanism (ii) was proposed on the basis of the crystal structure of phenylphosphorodiamidate-inhibited urease from S. pasteurii [50]. This mechanism suggests that urea displaces solvent ligands from both Ni atoms to bind in a bidentate manner. The bridging hydroxide attacks the carbonyl carbon, leading to a tetrahedral intermediate, and donates its proton to the departing ammonia. A third mechanism (iii) merges the first two by proposing that urea binds to Ni-2 and the bridging hydroxide attacks the carbonyl carbon, with a nearby His acting as the general acid [56, 57]. A fourth mechanism (iv) is based on biomimetic and computational methods [58, 59]. A general base (depicted as a terminal hydroxide, but other options are possible) abstracts a proton from one of the urea nitrogen atoms, resulting in release of ammonia and formation of a cyanate intermediate; the cyanate is subsequently hydrated to form carbamate. Notably, cyanate has never been detected as a product, nor is it a substrate of urease. Regardless of the mechanism, one might expect that other metals ions could substitute for Ni in facilitating urea hydrolysis. Indeed, Mn- or Co-substituted K. aerogenes enzyme possesses substantial activity [60] and a naturally-occurring Fe-containing urease has been purified from Helicobacter mustelae [61]

Superoxide dismutase

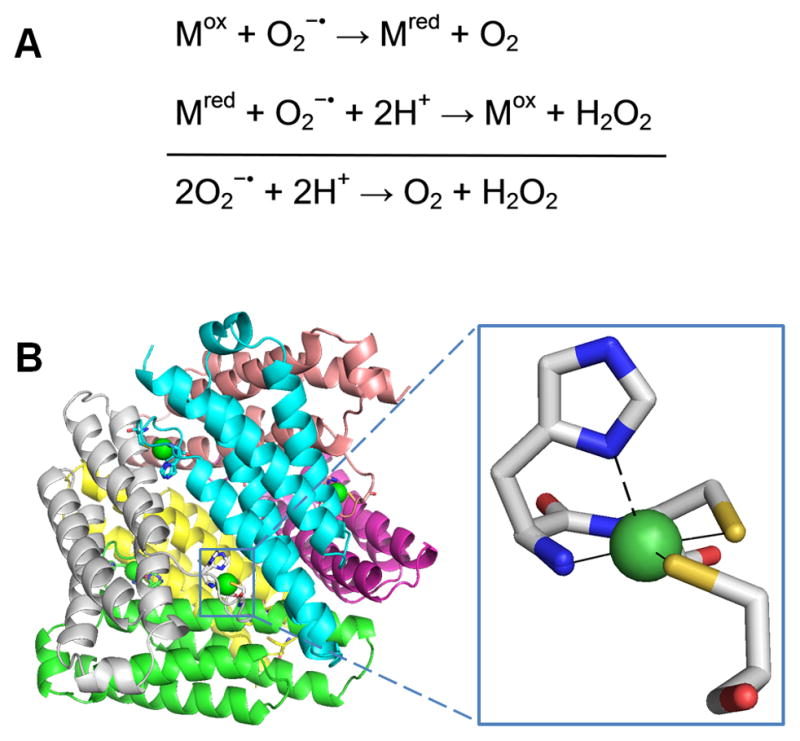

Cellular respiration using oxygen leads to the formation of superoxide radical anion (O2−·). This byproduct is reactive with iron-sulfur clusters [62] and other cellular components, and is implicated in a variety of age-related diseases. Cells can detoxify superoxide by converting it to O2 and H2O2 using the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). All SODs possess metal ions at their active site, and the most common forms utilize N- or O-donors to bind Fe or Mn mononuclear or Cu/Zn dinuclear centers [63]. The reaction proceeds by a 1-electron redox cycle of the metal ion as shown in Figure 4A.

Fig. 4.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD). (A) The reaction catalyzed by SOD. (B) NiSOD structure and active site. The homohexameric structure of NiSOD (cartoon view, PDB access code 1t6u, Streptomyces coelicolor) is shown with each subunit a different color. One active site is shown in the oxidized form, with Ni3+ (green sphere) coordinated via the amino terminal amine, a backbone amide, two Cys, and an axial His (stick view). The His is displaced as a ligand for the reduced state (indicated by the dashed line).

(1 column width)

A fourth class of SOD containing mononuclear Ni (NiSOD) [64] has been isolated from several Streptomyces bacteria [65, 66], studied in the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus marinus [67], and predicted to occur in several other genera [68]. While this enzyme shares a common functional role with the other SODs, several lines of evidence highlight its unique features. The amino acid sequence of NiSOD has no significant homology to the other SODs or to any other proteins. High resolution crystal structures (Figure 4B) have been determined for NiSOD from two Streptomyces sources [69, 70], and additional site-directed mutation and spectroscopic studies have been performed to define the Ni coordination geometry [66, 71–73]. The overall quaternary structure of NiSOD is unlike those of the other SODs; it exists as a homohexamer with each independently-acting Ni site located in an N-terminal hook. Post-translational processing to remove 14 N-terminal residues is necessary for Ni binding to occur [66].

The active site coordination of the Ni differs from the other SOD metal ions, and explains how nickel is able to carry out catalysis. The as-isolated protein contains a mixture of Ni2+ and Ni3+, each with its distinct coordination geometries. In the +2 state, Ni is bound in a square-planar configuration by a backbone amide from Cys2, a primary amine from the N terminus, and two thiolate ligands from Cys2 and Cys6. In the +3 state, it is bound in a five-coordinate square-pyramidal arrangement with the additional bond provided by the His1 via its Nδ atom (Figure 4C, inset). Thus, only three amino acid residues contribute to Ni binding. Spectroscopic and computational studies of NiSOD [74] and model compounds [75] show that the thiolate and imidazole ligands are critical in creating an environment that lowers the reduction potential of the Ni by over 1 V and renders it capable of catalyzing the 1-electron, 2-proton dismutation.

[NiFe]-Hydrogenase

Hydrogenases catalyze the interconversion of hydrogen gas with protons and electrons, as shown in Figure 5A. These enzymes are found in archaea, bacteria, and selected eukaryotes, where this reversible reaction is used either for consumption of excess reducing equivalents or for providing electrons destined for energy-generating pathways. Hydrogenases are generally categorized into three groups according to the type of metal(s) in their active site [76]. The heterodinuclear [NiFe]-hydrogenases are discussed below. [FeFe]-hydrogenases contain a dinuclear Fe active site along with Fe-S clusters [77]. The third group, known as the [Fe]-hydrogenases, contain a single Fe atom per subunit and lack Fe-S clusters; these enzymes couple hydrogen uptake to reduction of methylene-tetrahydromethanopterin in methanogenic Archaea [78].

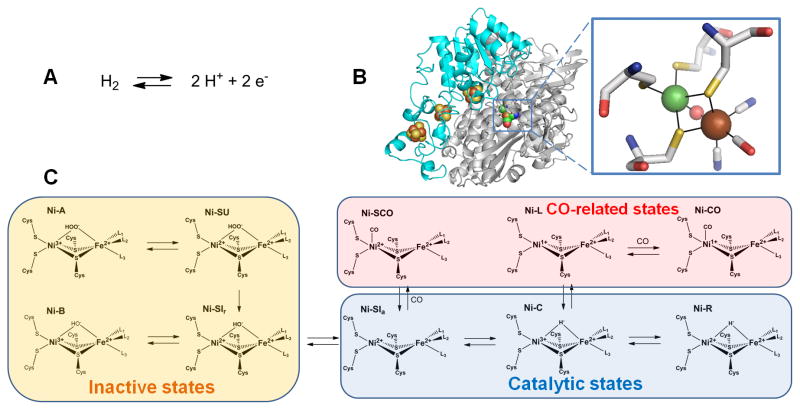

Fig. 5.

Hydrogenase. (A) The reaction catalyzed by hydrogenase. (B) Hydrogenase structure and active site. The dimeric [NiFe]-hydrogenase (cartoon view, PDB access code 1yrq, Desulfovibrio fructosovorans) contains three [FeS] clusters (brown and yellow spheres) in the small (cyan) subunit and the [NiFe] cluster in the large (white) subunit. An expanded view of the [NiFe] cluster is shown in stick view with the Ni (green sphere) coordinated by four Cys, two of which also coordinate Fe (brown sphere). In this state, a μ-oxo group (red sphere) bridges the two metals, and the Fe possesses a CO and two cyanide ligands. (C) Subset of the [NiFe] cluster states proposed for the [NiFe]-hydrogenase from Desulfovibrio vulgaris str. Miyazaki F. L1, L2, and L3 are diatomic ligands of Fe.

(2 column width)

[NiFe]-hydrogenases are typically composed of a minimum of two subunits: a large ~60-kDa catalytic subunit containing the Ni-Fe active site, and a small ~30-kDa electron transfer subunit with one or more Fe-S clusters [77, 79, 80]. Numerous crystal structures exist for [NiFe]-hydrogenases as exemplified by that for the enzyme from Desulfovibrio fructosovorans depicted in Figure 5B [81]. The active site is deeply buried in the large subunit with the Ni coordinated by four cysteine residues. Two of the same cysteines coordinate the Fe, which has additional diatomic ligands (two cyanide and one carbon monoxide are shown here, but these ligands can differ in enzymes from other sources) and a metal-bridging ligand is present in some redox states [82]. In addition, a subset of [NiFe]-hydrogenases possess a Se ligand, where a selenocysteine replaces a cysteine metallocenter ligand in the protein [83]. In the D. fructosovorans protein the small subunit contains three Fe-S clusters (proximal and distal [4Fe-4S] clusters separated by a [3Fe-4S] cluster), but alternative Fe-S cluster arrangements exist in enzymes from other organisms.

Biosynthesis and maturation of the [NiFe]-hydrogenase active site is a complex multistep process that involves many accessory proteins [80, 84, 85]. The best studied case of active site assembly is for E. coli hydrogenase 3. Of particular importance are the Hyp proteins, which function in generation and addition of CN− to iron (HypE, HypF,), Fe-CN delivery (HypD/HypC), and energy-dependent insertion of the nickel (HypA, HypB). The source of CO is unknown. A final proteolytic processing step is required to rearrange the protein structure to bury the assembled active site.

Aerobic purification of [NiFe]-hydrogenases often yields inactive enzyme that can slowly be activated under reducing conditions [86]. This initial finding led to further investigations of various active and inactive intermediate states, including crystallographic analyses of the D. fructosovorans enzyme [87] and spectroscopic studies of the enzyme from Desulfovibrio vulgaris [88, 89]. A simplified scheme depicting some of the known states is shown in Figure 5C; detailed discussion of these many forms is beyond the scope of this review [89, 90].

The overall reaction of [NiFe]-hydrogenase is complicated by the need for substrates/products (H2, protons, and electrons) to access the buried active site. In the case of D. fructosovorans, H2 traverses a hydrophobic channel that is evident in the high resolution crystal structure [81]. H2 is cleaved heterolytically to yield a proton and a hydride [91], with subsequent electron removal from the hydride to produce a second proton. Electron transfer utilizes the three Fe-S clusters, one of which is exposed to the protein surface where it can interact with a redox partner. The pathways for proton transport are less clear, but may involve a Cys ligand [92]. Presumably, protonatable side chains and water molecules can then move protons to the outside of the protein [93].

Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase

Carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) catalyzes the reversible oxidation of carbon monoxide to carbon dioxide (Figure 6A), thus playing a vital role in the global carbon cycle by allowing organisms to utilize carbon monoxide as a source of carbon and energy [94–96]. Two major classes of CODH exist: a molybdopterin/Cu/Fe-S cluster-containing enzyme is found in aerobic microorganisms [97] and a Ni-containing enzyme in anaerobes [98]. Ni-CODH can be found either as an independent enzyme or as part of a larger complex with acetyl-coenzyme A (CoA-SH) synthase/decarbonylase (ACS) activity, the focus of the following section.

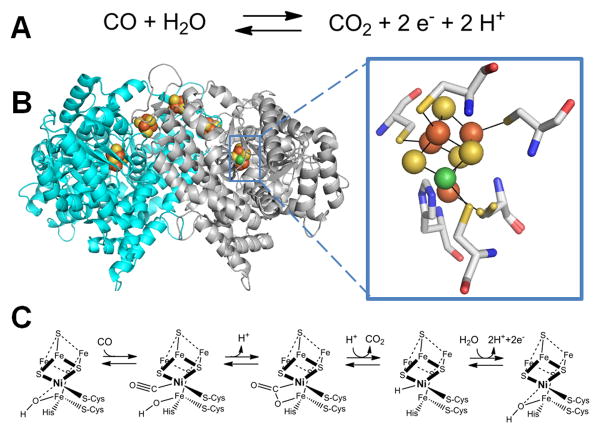

Fig. 6.

CO dehydrogenase (CODH). (A) The reaction catalyzed by CODH. (B) The CODH structure and active site. Dimeric CODH (cartoon view, 3b53, Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans) contains two [1Ni-4Fe-4S] clusters (green, brown, and yellow spheres) and three [4Fe-4S] clusters (brown and yellow spheres) including one which bridges the subunits. An expanded view of the [1Ni-4Fe-4S] cluster is shown with the ligands shown in stick view. (C) Mechanism of CODH. One proposal for the mechanism of CODH includes a Ni2+-hydride intermediate and retains Ni2+ in all steps; an alternative model invokes a Ni0 state following CO2 release.

(2 column width)

Crystallography studies reveal a dimeric structure for the independent CODHs from Rhodospirillum rubrum [99] or Carboxydothermus hydrogenoformans [100], a homodimer with two copies of another subunit for the Methanosarcina barkeri protein [101], and a CODH homodimer bridging additional subunits for the ACS from Moorella thermoacetica (formerly Clostridium thermoaceticum) [102, 103]. The C. hydrogenoformans CODH crystal structure (Figure 6B) depicts five metalloclusters per homodimer; each subunit contains a [1Ni-4Fe-4S] C-cluster and a typical [4Fe-4S] B-cluster, with a [4Fe-4S] D-cluster found at the interface of the subunits [100]. Depending on the source and the enzyme state the C-cluster structure can vary in the number of S atoms (4 or 5) and the identity of bound ligands [104–107], but in essence it can be viewed as [3Fe-4S] cluster bridged to a Ni-Fe center. The C-clusters are thought to be the sites of CO oxidation on the basis of genetic and spectroscopic studies whereas the three [4Fe-4S] clusters connect the two active sites to a separate electron carrier protein [94]. Ni incorporation into the CODH active site requires accessory proteins, but the maturation process has not been well studied [108–110].

A recent computationally-derived catalytic mechanism that accounts for the wealth of structural and spectroscopic data for CODH [111] retains Ni in the 2+ oxidation state throughout the reaction cycle (Figure 6C). The resting enzyme is thought to possess a hydroxide molecule bound to the unique Fe in the C-cluster. CO binds to the Ni and adopts a bent geometry. Nucleophilic attack by the hydroxide on the bound CO carbon forms a Ni-C(O)O-Fe intermediate, which decomposes to release CO2. In this mechanism, the resulting C-cluster possesses a Ni-bound hydride which is released as a proton by loss of two electrons; an alternative model proposes the intermediacy of a Ni0 state that is subsequently oxidized [94, 95, 106].

Acetyl-coenzyme A synthase/decarbonylase

Acetyl-S-CoA synthase/decarbonylase (ACS) is a CODH-containing protein complex that reversibly condenses CO (derived from CO2) with CoA-SH and a methyl group (derived from a corrinoid/Fe-S protein, abbreviated Co(III)-FeSP) to generate acetyl-S-CoA as depicted in Figure 7A [96]. Many types of anaerobic microorganisms utilize ACS as the key enzyme of the acetyl-S-CoA pathway used for fixing CO2, while acetate-degrading methanogenic archaea use this enzyme to convert the two-carbon substrate into CO2 and methane. ACS contains two Ni-containing active sites, one responsible for the CODH activity and one that catalyzes the reversible carbon-carbon-sulfur linkages of acetyl-S-CoA; these active sites are connected by an internal channel or tunnel [112–114].

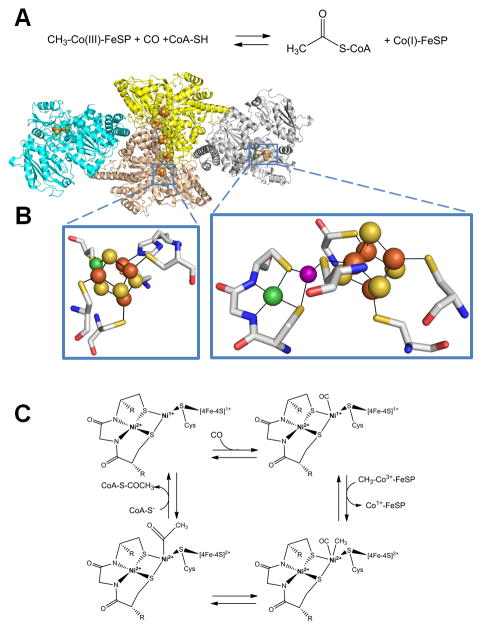

Fig. 7.

Acetyl-coenzyme A (acetyl-S-CoA) synthase/decarbonylase (ACS). (A) The reaction catalyzed by ACS. (B) ACS structure and active sites. ACS (cartoon view, PDB access code 2z8y, Morella thermoacetica) contains a CODH homodimer (yellow and sand) with two [1Ni-4Fe-4S] clusters (side chains shown in stick view, bottom left) and three [4Fe-4S] clusters, including one bridging the subunits, along with two subunits (cyan and gray cartoon) each containing a [Ni-M-4Fe-4S] cluster (side chains shown in stick view, bottom right). The structure shown is for an inactive protein where M is Cu (purple sphere), but the active enzyme possesses Ni at this site. (C) ACS mechanism. In this oversimplified view of the ACS mechanism, the Ni located distal to the [4Fe-4S] cluster retains its divalent state throughout catalysis whereas the proximal Ni cycles between the Ni2+ and Ni1+ states. Alternative mechanisms invoke Ni3+ or Ni0 states for the proximal metal site.

(2 column width)

Crystal structures for ACS are available for the CODH-containing complex from M. thermoacetica [102, 103, 114] and as the CODH-free ACS subunit from C. hydrogenoformans [115]. The M. thermoacetica protein complex consists of the core CODH dimer with additional subunits bound on either side (Figure 7B). The additional subunits each contain an A-cluster that includes a [4Fe-4S] cluster bridged via a Cys residue to a proximal metal site that bridges to a distal metal site via two other Cys residues. The distal metal is Ni, coordinated by two backbone amides in addition to the two Cys residues, whereas the proximal metal site can be occupied by Ni, Cu or Zn (the Cu form is shown in Figure 7B); the dinuclear Ni site appears to be physiologically relevant [102–104, 115].

The catalytic mechanism of ACS is not fully established, but evidence suggests the proximal Ni atom changes oxidation state, whereas the distal Ni remains in the 2+ oxidation state throughout the reaction [116] (Figure 7C). CO binds to the proximal metal in the Ni1+ state forming a species that has been trapped and spectroscopically characterized [117], with the same Ni subsequently undergoing methylation by the CH3-Co(III)-FeSP. The CO and methyl group react to form an acetyl group, which undergoes nucleophilic attack by CoA-SH to form acetyl-S-CoA [118]. Alternate mechanisms with distinct oxidation states of the proximal Ni for the intermediates have also been suggested [116, 119].

Methyl-coenzyme M reductase and anaerobic methane oxidation

Methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR) plays an important role in the global carbon cycle by catalyzing the interconversion of methyl-coenzyme M (methyl-S-thioethanesulfonate, CH3-S-CoM) plus coenzyme B (N-7-mercaptoheptanoylthreonine phosphate, CoB-SH) with methane and the heterodisulfide CoM-S-S-CoB (Figure 8A) [96, 120]. All biologically produced methane is formed by methanogenic archaea using MCR, and the reverse reaction is carried out by other archaea catalyzing the anaerobic oxidation of methane in synergy with sulfate-reducing bacteria [121, 122].

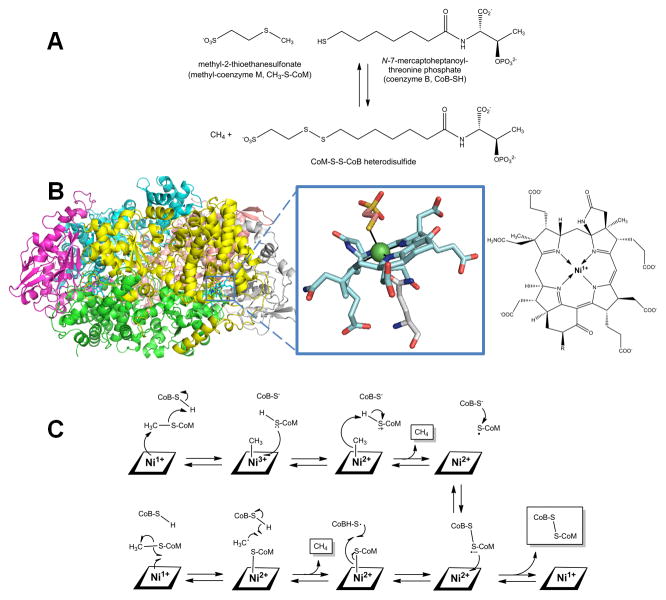

Fig. 8.

Methyl-coenzyme M reductase (MCR). (A) The reaction catalyzed by MCR. (B) MCR structure and active site. MCR is a dimer of the αβγ subunits (cartoon view, PDB access code 1mro, Methanothermobacter marburgensis). Each active site (Ni as a green sphere with ligands in stick view) contains coenzyme F430 with an axial Gln ligand, and an additional axially coordinated CoM-SH in this particular structure. A line drawing of coenzyme F430 is illustrated for clarity, where R is H or S-CH3 depending on the source. (C) Two postulated reaction mechanism of MCR. In the upper pathway, the Ni1+ attacks the methyl group of methyl-S-CoM to form a methyl-Ni3+ intermediate. In the lower pathway, a CoM-S-Ni2+ intermediate is formed. Both pathways incorporate a disulfide anion radical.

(2 column width)

High resolution crystal structures have been obtained for the oxidized form of MCR, revealing a primarily helical 300-kDa hexamer in a α2β2γ2 arrangement (Figure 8B) [123, 124]. The α subunit contains the active site which includes coenzyme F430, a Ni-tetrapyrrole [125]. This corphinoid species is related to sirohemes and corrinoids, but it contains only five double bonds making it the most reduced tetrapyrrole in nature. Slight modifications exist in the structure of this yellow compound when derived from methanogens versus anaerobic methane oxidizers [122]. F430 is active when in the Ni1+ oxidation state, but it is easily converted to other oxidation states [126–128]. The coenzyme is tightly but non-covalently bound at the terminus of a hydrophobic channel that prevents solvent from accessing the active site and allows for coordination of the substrates. In addition to the tetrapyrrole nitrogens, Ni is axially coordinated by a Gln side chain with the second axial coordination site available for substrate binding [123, 124, 129].

The reaction mechanism of MCR continues to be investigated, with two major proposals under active consideration (Figure 8C). One prominent mechanism (upper pathway) postulates that the F430 Ni1+ center performs an SN2 reaction on the methyl group of methyl-CoM, forming a methyl-Ni3+ F430 species and the CoM-S− thiolate anion, which would reasonably be protonated by CoB-SH. Electron transfer from CoM-SH to the metal could produce the methyl-Ni2+ F430 species which should be able to undergo protonolysis, yielding methane, Ni2+ F430 cofactor, and the CoM-S• radical. Subsequent linkage of the radical with the CoB-S− anion generates the disulfide radical anion. Electron transfer from this species to the oxidized cofactor would yield the disulfide and regenerate the initial Ni1+ F430 state [96, 130–133]. A second commonly cited mechanism, based primarily on computational studies, proposes that the Ni1+ F430 cofactor catalyzes homolytic cleavage of the C-S bond of methyl-CoM to generate a methyl radical and the Ni2+-bound thiol. The methyl radical is proposed to abstract a hydrogen atom from CoB-SH, forming methane and the CoB-S• thiyl radical. Recombination yields the same disulfide anion radical and Ni2+ F430 species as in the earlier mechanism, with electron transfer again yielding the disulfide product and the regenerated Ni1+ F430 cofactor [96, 131, 134, 135].

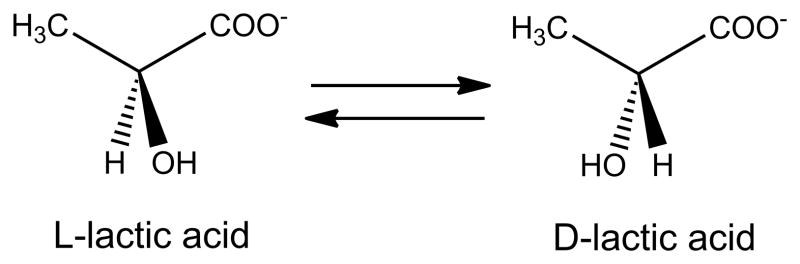

Lactate racemase

The most recently identified Ni-dependent enzyme is lactate racemase or LarA (unpublished observations by Drs. B. Desguin, P. Soumillion, and P. Hols, personal communication). This enzyme catalyzes the racemization between L- and D-lactic acid (Figure 9), a reaction that may involve transient hydride transfer to Ni. The structure of the apoprotein has been determined and spectroscopic studies suggest the holoprotein contains a five-coordinate Ni with at least two His ligands. Three accessory proteins (LarB, LarC, and LarE) are required for metallocenter assembly.

Fig. 9.

Reaction catalyzed by lactate racemase.

(1 column width)

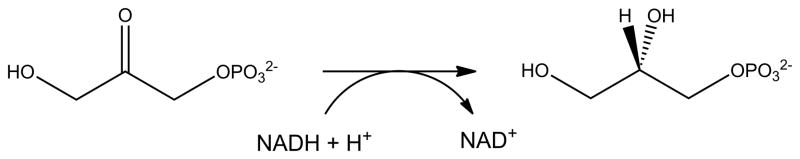

Other Ni-dependent enzymes

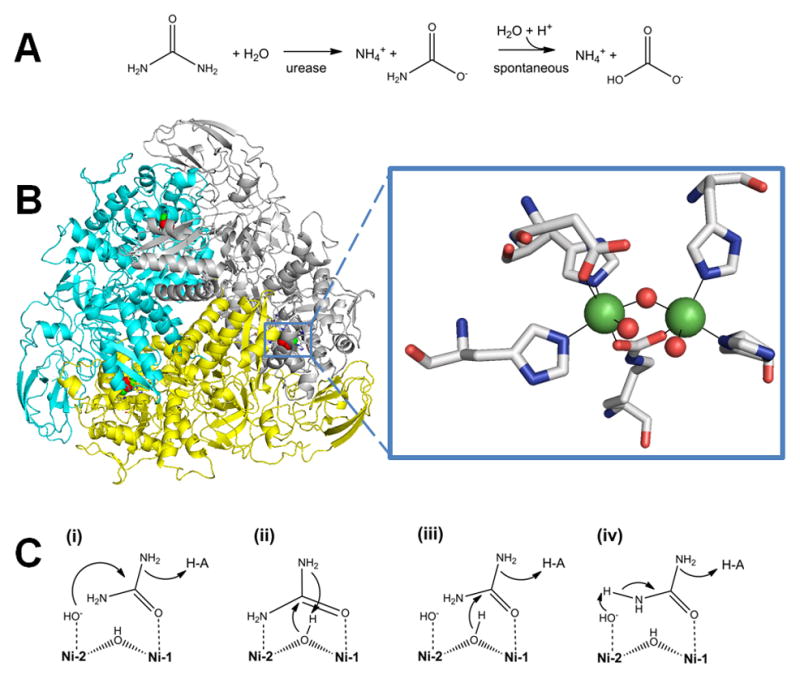

Many non-redox metalloenzymes are active when their native metal is replaced by Ni as illustrated by the 1960 study of Ni-substituted metallocarboxypeptidases that use zinc as their native metal [136]. It is likely that other true Ni-dependent enzymes exist, but proving Ni is the physiologically relevant metal is not trivial. Two examples illustrate the complexity of establishing metal specificity. QueD, a quercetinase, catalyzes the transformation of the flavonol quercetin by a dioxygenase reaction that releases carbon monoxide (Figure 10). In some microorganisms the enzyme contains copper, in others the reaction is promoted best by manganese, and the Streptomyces sp. FLA enzyme is most active with Ni or cobalt [137]. This result is based on the finding of greatest QueD activity in cell extracts of cultures supplemented with either of these metals, but not manganese, iron, copper, or zinc; however, the cell growth studies used a recombinant high-expression system in E. coli. Even with Ni-supplemented growth the purified protein contains only ~0.5 equivalents of Ni, thus the relevance to metal speciation of protein in the native host remains unclear. In a similar manner, a glycerol-1-phosphate dehydrogenase (Figure 11) from Bacillus subtilis (AraM) was reported to be Ni-dependent on the basis of the activity in recombinant E. coli cells expressing araM and grown with various metal ions [138]. Additionally, AraM apoprotein was obtained by prolonged treatment with EDTA, and Ni was shown to be greatly superior to zinc, cobalt, or other metal ions in restoring activity.

Fig. 10.

Reaction catalyzed by the QueD quercetinase.

(1.5 column width)

Fig. 11.

Reaction catalyzed by AraM, a glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase.

(1.5 column width)

Genomic sequencing efforts are uncovering homologs to genes encoding QueD, AraM, and the nine Ni-dependent enzymes described earlier in a large number of organisms. The presence of these genes suggests the existence of Ni-containing enzymes, but this need not be the case as shown by quercetinases that utilize other metals or by Fe-dependent urease. Furthermore, the diverse types of Ni environments in the various Ni-dependent enzymes mean that it is very difficult, if not impossible, to identify a new type of Ni-containing enzyme based only on the gene sequence.

To establish that a particular enzyme is dependent on Ni in vivo, several lines of inquiry should be undertaken. It is desirable to quantify the metal content of that protein when purified from the native host without using an overexpression system. Furthermore, it is useful to assess the effects of mutations/deletions of genes affecting metal uptake or metal efflux systems on the enzyme activity of interest; e.g., in regard to AraM no Ni uptake system is known for B. subtilis [139]. Metal-dependent transcription studies of the gene encoding the target protein also can hint at the metal specificity. Finally, one should examine the effects of metal identity on enzyme activity, being sure to utilize anaerobic conditions when testing an oxygen-sensitive metal such as ferrous ions.

In addition to the above enzymes known to utilize Ni, it is very likely that Ni is required for still-uncharacterized activities of other proteins. For example, during a structural proteomics analysis of the archaeon Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum, protein MTH152 was only able to be crystallized in the presence of Ni [140]. The structure of MTH152 suggested the metal plays an important role in bridging flavin mononucleotide and residues of the protein, but the function of the putative flavoenzyme is unknown. Furthermore, chromatographic resolution and mass spectrometric detection of metalloproteins from Pyrococcus furiosus uncovered four new Ni-containing proteins of unknown function in this thermophilic microorganism [141]. Similar discoveries are nearly certain to occur as additional host organisms from diverse environmental niches are studied.

Concluding remarks

Although limited in number, Ni-containing enzymes exhibit a rich diversity of metallocenter structures and participate in a variety of important reactions. Further understanding of these enzymes is certain to include additional structural and spectroscopic studies of the proteins themselves along with computational and bioinorganic modeling efforts. Novel Ni-containing enzymes await discovery, and other aspects of Ni metabolism (transport and delivery to the correct apoprotein, as well as Ni-dependent regulation) remain incompletely understood. Clearly, many exciting avenues of investigation exist for those interested in Ni!

Highlights.

The function, structure, and mechanisms are described for nickel-dependent enzymes

Nickel active sites range from simple mononuclear centers to complex multi-metal complexes

Methods to establish nickel specificity are discussed

Acknowledgments

Studies in the authors’ laboratory related to this review were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (DK045686).

Abbreviations used

- ACS

acetyl coenzyme A synthase/decarbonylase

- ARD

acireductone dioxygenase

- CoA-SH

coenzyme A

- CODH

carbon monoxide dehydrogenase

- CoB-SH

coenzyme B

- CoM-SH

coenzyme M

- GlxI

glyoxalase I

- GSH

glutathione

- MCR

methyl-coenzyme M reductase

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Mulrooney SB, Hausinger RP. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;27:239–261. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00042-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ragsdale SW. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18571–18575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R900020200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaluarachchi H, Chan Chung KC, Zamble DB. Natural Product Reports. 2010;27:681–694. doi: 10.1039/b906688h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins KA, Carr CE, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7816–7832. doi: 10.1021/bi300981m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Y, Zamble DB. Chem Rev. 2009;109:4617–4643. doi: 10.1021/cr900010n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eitinger T, Mandrand-Berthelot MA. Arch Microbiol. 2000;173:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s002030050001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eitinger T, Suhr J, Moore L, Smith JAC. BioMetals. 2005;18:399–405. doi: 10.1007/s10534-005-3714-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwig JS, Chivers PT. Natural Product Reports. 2010;27:658–667. doi: 10.1039/b906683g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macomber L, Hausinger RP. Metallomics. 2011;3:1153–1162. doi: 10.1039/c1mt00063b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y, Rodionov DA, Gelfand MS, Gladyshev VN. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:78. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillips SA, Thornalley PJ. Eur J Biochem. 1993;212:101–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron AD, Olin B, Ridderstrom M, Mannervik B, Jones TA. EMBO J. 1997;16:3386–3395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clugston SL, Barnard JFJ, Kinach R, Miedema D, Ruman R, Daub E, Honek JF. Biochemistry. 1998;37:8754–8763. doi: 10.1021/bi972791w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He MM, Clugston SL, Honek JF, Matthews BW. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8719–8727. doi: 10.1021/bi000856g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hall SS, Doweyko AM, Jordan F. J Am Chem Soc. 1976;98:7460–7461. doi: 10.1021/ja00439a077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sellin S, Rosevear PR, Mannervik B, Mildvan AS. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:23–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feierberg I, Cameron AD, Aqvist J. FEBS Lett. 1999;453:90–94. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00703-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feierberg I, Luzhkov V, Aqvist J. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22657–22662. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ly HD, Clugston SL, Sampson PB, Honek JF. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 1998;8:705–710. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davidson G, Clugston SL, Honek JF, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4569–4582. doi: 10.1021/bi0018537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luk GD, Baylin SB. West J Med. 1985;1424:88–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang SF, Hoffman NE. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1984;35:155–189. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Albers E. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:1132–1142. doi: 10.1002/iub.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai Y, Wensink PC, Abeles RH. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1193–1195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pochapsky TC, Ju T, Dang M, Beaulieu R, Pagani GM, OuYang B. Metal Ions Biol Syst. 2007;2:473–500. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pochapsky TC, Pochapsky SS, Ju T, Mo H, Al-Mjeni F, Maroney MJ. Nature Struct Biol. 2002;9:966–972. doi: 10.1038/nsb863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Mjeni F, Ju T, Pochapsky TC, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 2002;41:6761–6769. doi: 10.1021/bi012209a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pochapsky TC, Pochapsky SS, Ju T, Hoefler C, Liang J. J Biomolec NMR. 2006;34:117–127. doi: 10.1007/s10858-005-5735-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ju T, Goldsmith RB, Chai SC, Maroney MJ, Pochapsky SS, Pochapsky TC. J Molec Biol. 2006;393:823–834. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chai SC, Ju T, Dang M, Goldsmith RB, Maroney MJ, Pochapsky TC. Biochemistry. 2008;47:2428–2438. doi: 10.1021/bi7004152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szajna E, Arif AM, Berreau LM. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:17186–17187. doi: 10.1021/ja056346x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berreau LM, Borowski T, Grubel K, Allpress CJ, Wikstrom JP, Germain ME, Rybak-Akimova EV, Tierney DL. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1047–1057. doi: 10.1021/ic1017888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allpress CJ, Grubel K, Szajna-Fuller E, Arif AM, Berreau LM. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:659–668. doi: 10.1021/ja3038189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carter EL, Flugga N, Boer JL, Mulrooney SB, Hausinger RP. Metallomics. 2009;1:207–221. doi: 10.1039/b903311d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krajewska B. J Molec Catalysis B: Enzymatic. 2009;59:9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Witte CP. Plant Sci. 2011;180:431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zambelli B, Musiani F, Benini S, Ciurli S. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:520–530. doi: 10.1021/ar200041k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mobley HLT, Island MD, Hausinger RP. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:451–480. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.451-480.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mobley HLT, Hausinger RP. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:85–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.1.85-108.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Collins CM, D’Orazio SEF. Molec Microbiol. 1993;9:907–913. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burne RA, Chen YYM. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:533–542. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Atherton JC. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2006;1:63–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusters JG, Van Vliet AHM, Kuipers EJ. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:449–490. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00054-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stingl K, Altendorf K, Bakker EP. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10:70–74. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02287-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zonia LE, Stebbins NE, Polacco JC. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:1097–1103. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.4.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polacco JC, Mazzafera P, Tezotto T. Plant Sci. 2013;199–200:79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jabri E, Carr MB, Hausinger RP, Karplus PA. Science. 1995;268:998–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Balasubramanian A, Ponnuraj K. J Molec Biol. 2010;400:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ha NC, Oh ST, Sung JY, Cha KA, Lee MH, Oh BH. Nature Struct Biol. 2001;8:505–509. doi: 10.1038/88563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benini S, Rypniewski WR, Wilson KS, Miletti S, Ciurli S, Mangani S. Structure. 1999;7:205–216. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balasubramanian A, Durairajpandian V, Elumalai S, Mathivanan N, Munirajan AK, Ponnuraj K. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;58C:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.04.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park IS, Hausinger RP. Science. 1995;267:1156–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.7855593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pearson MA, Michel LO, Hausinger RP, Karplus PA. Biochemistry. 1997;36:8164–8172. doi: 10.1021/bi970514j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Farrugia MA, Macomber L, Hausinger RP. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:13178–13185. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.446526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dixon NE, Riddles PW, Gazzola C, Blakeley RL, Zerner B. Can J Biochem. 1980;58:1335–1344. doi: 10.1139/o80-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Todd MJ, Hausinger RP. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5389–5396. doi: 10.1021/bi992287m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pearson MA, Park IS, Schaller RA, Michel LO, Karplus PA, Hausinger RP. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8575–8584. doi: 10.1021/bi000613o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barrios AM, Lippard SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:9172–9177. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Estiu G, Merz KM., Jr J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:10263–10274. doi: 10.1021/jp072323o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamaguchi K, Cosper NJ, Stalhanske C, Scott RA, Pearson MA, Karplus PA, Hausinger RP. J Biol Inorg Chem. 1999;4:468–477. doi: 10.1007/s007750050333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carter EL, Tronrud DE, Taber SR, Karplus PA, Hausinger RP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13095–13099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106915108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Flint DH, Tuminello JF, Emptage MH. J Biol Chem. 1993;268 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abreu IA, Cabelli DE. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ. In: Nickel ands Its Surprising Impact on Nature. Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel ROK, editors. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; West Sussex, England: 2007. pp. 417–444. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Youn HD, Kim EJ, Roe JH, Hah YC, Kang SO. Biochem J. 1996;318:889–896. doi: 10.1042/bj3180889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bryngelson PA, Arobo SE, Pinkham JL, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:460–461. doi: 10.1021/ja0387507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eitinger T. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7812–7825. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7821-7825.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dupont CL, Neupane K, Shearer J, Paienik B. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10:1831–1843. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wuerges J, Lee JW, Yim YI, Kang SO, Carugo KD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8569–8574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308514101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barondeau DP, Kassman CJ, Bruns CK, Tainer JA, Getzoff ED. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8038–8047. doi: 10.1021/bi0496081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Choudhury SB, Lee JW, Davidson G, Yim YI, Bose K, Sharma ML, Kang SO, Cabelli DE, Maroney MJ. Biochemistry. 1999;38:3744–3752. doi: 10.1021/bi982537j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Szilagyi RK, Musaev DG, Morokuma K. J Molec Struct-Theochem. 2000;506:131–146. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ryan K, Johnson O, Cabelli DE, Brunold T, Maroney MJ. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2010;15:795–807. doi: 10.1007/s00775-010-0645-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fiedler AT, Bryngelson PA, Maroney MJ, Brunold TC. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5449–5462. doi: 10.1021/ja042521i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Broering EP, Truong PT, Gale EM, Harrop TC. Biochemistry. 2013;52:4–18. doi: 10.1021/bi3014533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vignais PM, Billoud B. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4206–4272. doi: 10.1021/cr050196r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fontecilla-Camps JC, Volbeda A, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4273–4303. doi: 10.1021/cr050195z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Corr MJ, Murphy JA. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:2279–2292. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00150c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.de Lacey AI, Fernández VM, Rousset M. Coord Chem Rev. 2005;249:1596–1608. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Böck A, King PW, Blokesch M, Posewitz MC. Adv Microbial Physiol. 2006;51:1–71. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(06)51001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Volbeda A, Montet Y, Vernède X, Hatchikian EC, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2002;27:1449–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pierik AJ, Roseboom W, Happe RP, Bagley KA, Albracht SPJ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3331–3337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Baltazar CSA, Marques CJ, Soares CM, De Lacey AI, Pereira IAC, Matias PM. Eur J Inorg Chem. 2011:948–962. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Watanabe S, Sasaki D, Tominaga T, Miki K. Biol Chem. 2012;393:1089–1100. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McGlynn SE, Mulder DW, Shepard EM, Broderick JB, Peters JW. Dalton Trans. 2009:4274–4285. doi: 10.1039/b821432h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fernandez VM, Hatchikian EC, Cammack R. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;832:69–79. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Volbeda A, Martin L, Cavazza C, Matho M, Faber BW, Rosebloom W, Albracht SPJ, Garcia E, Rousset M, Fontecilla-Camps JC. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2005;10:239–249. doi: 10.1007/s00775-005-0632-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fichtner C, Laurich C, Bothe H, Lubitz W. Biochemistry. 2006;45:9706–9716. doi: 10.1021/bi0602462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pandelia ME, Ogata H, Lubitz W. ChemPhysChem. 2010;11:1127–1140. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200900950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ogata H, Lubitz W, Higuchi Y. Dalton Trans. 2009:7577–7587. doi: 10.1039/b903840j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Berlier Y, Lespinat PA, Dimon B. Anal Biochem. 1990;188:427–431. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90631-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Matias PM, Soares CM, Saraiva LM, Coelho R, Morais J, Le Gall J, Carrondo MA. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2001;6:63–81. doi: 10.1007/s007750000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Williams RJP. Nature. 1995;376:643. doi: 10.1038/376643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Volbeda A, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Dalton Trans. 2005:3443–3450. doi: 10.1039/b508403b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kung Y, Drennan CL. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ragsdale SW. J Inorg Biochem. 2007;101:1657–1666. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.King GM, Weber CF. Nature Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:107–118. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Oelgeschläger E, Rother M. Arch Microbiol. 2008;190:257–269. doi: 10.1007/s00203-008-0382-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Drennan CL, Heo J, Sintchak MD, Schreiter E, Ludden PW. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:11973–11978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211429998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Dobbek H, Svetlitchnyi V, Gremer L, Huber R, Meyer O. Science. 2001;293:1281–1285. doi: 10.1126/science.1061500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gong W, Hao B, Wei Z, Ferguson DJ, Jr, Tallant T, Krzycki JA, Chan MK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9558–9563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800415105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Doukov TI, Iverson TM, Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW, Drennan CL. Science. 2002;298:567–272. doi: 10.1126/science.1075843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Darnault C, Volbeda A, Kim EJ, Legrand P, Vernède X, Lindahl PA, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Nature Struct Biol. 2003;10:271–279. doi: 10.1038/nsb912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Drennan CL, Doukov TI, Ragsdale SW. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:511–515. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0563-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dobbek H, Svetlitchnyi V, Liss J, Meyer O. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:5382–5387. doi: 10.1021/ja037776v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Jeoung JH, Dobbek H. Science. 2007;318:1461–1464. doi: 10.1126/science.1148481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kung Y, Doukov TI, Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW, Drennan CL. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7432–7440. doi: 10.1021/bi900574h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kerby RL, Ludden PW, Roberts GP. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2259–2266. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2259-2266.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Watt RK, Ludden PW. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10019–10025. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.10019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jeon WB, Cheng J, Ludden PW. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38602–38609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104945200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Amara P, Mouesca JM, Volbeda A, Fontecilla-Camps JC. Inorg Chem. 2011;50:1868–1878. doi: 10.1021/ic102304m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1274–1277. doi: 10.1021/bi991812e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maynard EL, Lindahl PA. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:9221–9222. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Doukov TI, Blasiak LC, Seravalli J, Ragsdale SW, Drennan CL. Biochemistry. 2008;47:3474–3483. doi: 10.1021/bi702386t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Svetlitchnyi V, Dobbek H, Meyer-Klaucke W, Meins T, Thiele B, Römer P, Huber R, Meyer O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:446–451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304262101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bender G, Stich TA, Yan L, Britt RD, Cramer SP, Ragsdale SW. Biochemistry. 2010;49:7516–7523. doi: 10.1021/bi1010128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Seravalli J, Kumar M, Ragsdale SW. Biochemistry. 2002;41:1807–1819. doi: 10.1021/bi011687i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Amara P, Volbeda A, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Field MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:2776–2784. doi: 10.1021/ja0439221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lindahl PA. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2004;9:516–524. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0564-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Jaun B, Thauer RK. Metal Ions Biol Syst. 2007;2:323–356. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Boetius A, Ravenschlag K, Schubert CJ, Ricker D, Widdel F, Gieseke A, Amann R, Jorgensen BB, Witte U, Pfannkuche O. Nature. 2000;407:623–626. doi: 10.1038/35036572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Scheller S, Goenrich M, Boecher R, Thauer RK, Jaun B. Nature. 2010;465:606–608. doi: 10.1038/nature09015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ermler U, Grabarse W, Shima S, Goubeaud M, Thauer RK. Science. 1997;278:1457–1462. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Grabarse W, Mahlert F, Duin EC, Goubeaud M, Shima S, Thauer RK, Lamzin V, Ermler U. J Molec Biol. 2001;309:315–330. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Diekert G, Jaenchen R, Thauer RK. FEBS Lett. 1980;119:118–120. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(80)81011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Goubeaud M, Schreiner G, Thauer RK. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:110–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Telser J, Davydov R, Horng YC, Ragsdale SW, Hoffman BM. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5853–5860. doi: 10.1021/ja010428d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Mahlert F, Grabarse W, Kahnt J, Thauer RK, Duin EC. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s007750100270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Grabarse W, Mahlert F, Shima S, Thauer RK, Ermler U. J Molec Biol. 2000;303:329–344. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Horng YC, Becker DF, Ragsdale SW. Biochemistry. 2001;40:12875–12885. doi: 10.1021/bi011196y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Thauer RK. Microbiology. 1998;144:2377–2406. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sarangi R, Dey M, Ragsdale SW. Biochemistry. 2009;48:3146–3156. doi: 10.1021/bi900087w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Dey M, Li X, Kunz RC, Ragsdale SW. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10902–10911. doi: 10.1021/bi101562m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pelmenschikov V, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM, Crabtree RH. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:4039–4049. doi: 10.1021/ja011664r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Chen LL, Blomberg MRA, Siegbahn PEM. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:6309–6315. [Google Scholar]

- 136.Coleman JE, Vallee BL. J Biol Chem. 1960;235:390–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Merkens H, Kappl R, Jakob RP, Schmid FX, Fetzner S. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12185–12196. doi: 10.1021/bi801398x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Guldan H, Sterner R, Babinger P. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7376–7384. doi: 10.1021/bi8005779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Moore CM, Helmann JD. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Christendat D, Yee A, Dharamsi A, Kluger Y, Savchenko A, Jr, Cort, Booth V, Mackereth CD, Saridakis V, Ekiel I, Kozlov G, Maxwell KL, Wu N, McIntosh LP, Gehring K, Kennedy MA, Davidson AR, Pai EF, Gerstein M, Edwards AM, Arrowsmith CH. Nature Struct Biol. 2000;7:903–909. doi: 10.1038/82823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Cvetkovic A, Menon AL, Thorgersen MP, Scott JW, Poole FL, II, Jenney FE, Jr, Lancaster WA, Praissman JA, Shanmukh S, Vaccaro BJ, Trauger SA, Kalisiak E, Apon JV, Siuzdak G, Yannone SM, Tainer JA, Adams MWW. Nature. 2010;466:779–782. doi: 10.1038/nature09265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]