Abstract

Background

On most occasions treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis is started by physicians based predominantly on radiological opacities. Since these opacities may not be suggestive of active pulmonary tuberculosis and most of these opacities may even remain unchanged after complete treatment, starting treatment solely on the basis of these opacities may lead to ambiguous end points of cure. In view of this, study of misdiagnosis of radiological opacities as active pulmonary tuberculosis by physicians was undertaken in one of the respiratory centers of Armed Forces hospitals.

Methods

This was a prospective study of patients referred to our center for confirmation of active disease and institutional therapy. All patients who were diagnosed as pulmonary tuberculosis predominantly on radiological basis by physicians were evaluated for active pulmonary tuberculosis clinically, radiologically and microbiologically. Patients found to have inactive disease were followed for one year. At three monthly review, history, clinical examination, sputum AFB and chest radiographs were done.

Results

There were 36 patients [all males, mean age: 36.9 years (range: 22–46 years)]. The most common initial presentation was of asymptomatic persons (33.3%) reporting for routine medical examination. The commonest radiological pattern was localized reticular opacities (52.8%)On follow up, only one patient was diagnosed to have pulmonary tuberculosis. The final diagnosis was consolidation in 6, bronchiectasis in 8, pulmonary tuberculosis in 1 and localized pulmonary fibrosis in 21 patients.

Conclusion

Diagnosing and treating tuberculosis predominantly on radiological basis is not appropriate and sputum microscopy and culture remains the cornerstone of diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis.

Keywords: Pulmonary opacities, Radiological misdiagnosis, Pulmonary tuberculosis

Introduction

The Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) was launched in our country for overcoming the factors considered responsible for the failure of the earlier National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP).1 One such factor was over-dependence on radiology and under-use of sputum microscopy for the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis.1,2 Diagnosis of tuberculosis is based on examination of sputum by quality sputum microscopy.3,4 However, it has been observed that most of the physicians do not insist on quality sputum microscopy for diagnosis and in the absence of positive sputum microscopy for acid fast bacillus (AFB), anti- tubercular treatment (ATT) is started solely on the basis of radiological opacities. These opacities may remain unchanged even after full course of ATT in most of these cases leading to ambiguous end points for cure and also with attendant side effects due to unnecessary administration of ATT. In view of this, present study of misdiagnosis of radiological opacities as active pulmonary tuberculosis by physicians was undertaken in one of the respiratory centers of Armed Forces hospitals.

Material and methods

This was a prospective study carried out over 18 months in one of the respiratory centers of armed forces hospital. Thirty-six patients who were diagnosed as pulmonary tuberculosis predominantly on radiological basis by physicians and were smear negative for pulmonary tuberculosis were evaluated for active pulmonary tuberculosis by means of detailed history and clinical examination. Laboratory investigation like erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), blood counts, sputum smear for AFB, gram staining, cultures for pyogenic organisms, Lowenstein Jensen (LJ) and radiometric MTB culture, fungal studies and malignant cells were performed. All these patients were subjected to computed tomography (CT) of thorax.

The patients who were smear AFB negative were subjected to fiber optic bronchoscopy (FOB) and broncho alveolar lavage (BAL) analysis for AFB and MTB culture on LJ medium. All patients who were found to have no evidence of active disease were followed up with three monthly reviews till one year. During review, patients were evaluated by history, clinical examination, sputum for AFB and chest radiograph.

Results

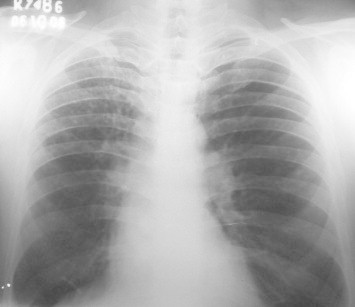

There were 36 patients [all male patients, mean age 36.6 years (Range 22–46 years)]. Table 1 shows that most common initial presentation was of asymptomatic persons reporting for routine medical examination. Table 2 shows that the most common opacities on chest radiograph were reticular opacities seen in 19 (52.8%) patients. CT thorax showed reticular opacities in 19 (52.8%), nodular opacities in 12 (33.3%), cystic opacities in 8 (22.2%) [Fig. 1], calcific opacities in 7 (19.4%) and acinar opacities in 6 (16.7%) cases. Opacities were localized in all cases and upper zone involvement [Fig. 2] was seen in 23 patients (63.9%), mid zone in 10 (27.8%) and lower zone in 6 (16.7%). Sputum smear was false positive in one case and MTB culture was false positive in one patient. BAL for AFB smear and culture were negative in all the cases. 12 patients (33.3%) were already on ATT (EHRZ) started by physicians and one was on second line ATT started on radiological basis. On follow up, one patient showed radiological deterioration of nodular opacities at six months and was diagnosed to have smear negative and culture positive pulmonary tuberculosis and was treated with ATT. All other patients remained asymptomatic with negative sputum AFB in all cases during follow up. Acinar opacities had shown complete resolution in all 6 cases. The final diagnosis was pneumonic consolidation in 6 (16.7%), bronchiectasis in 8 (22.2%), localized pulmonary fibrosis in 21 (58.3%) and pulmonary tuberculosis in one (2.8%) patient.

Table 1.

Initial presentation at peripheral hospital.

| Presenting complaints | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Streaky hemoptysis | 05 (13.9%) |

| Fever (<1 week) | 08 (22.2%) |

| Productive cough (<2 weeks) | 07 (19.4%) |

| Unquantified weight loss | 02 (5.5%) |

| Breathlessness | 02 (5.5%) |

| Asymptomatic | 12 (33.3%) |

Table 2.

Pattern of opacities on chest radiograph.

| Radiologic opacities | No (%) |

|---|---|

| Reticular opacities | 19 (52.8%) |

| Cystic opacities | 04 (11.1%) |

| Acinar opacities | 06 (16.7%) |

| Nodular opacities | 07 (19.4%) |

| Calcific opacities | 07 (19.4%) |

Fig. 1.

High resolution computed tomogram showing cystic lucencies in right upper lobe.

Fig. 2.

Chest radiograph showing cystic opacities in right upper zone.

Discussion

The study was carried out in an Armed Forces chest center where serving soldiers suspected to have pulmonary tuberculosis are referred by physicians for evaluation. It was observed that ATT is often started predominantly on radiological basis in asymptomatic patients or those with illness of short duration. These patients are evaluated in detail for disease activity and those who are diagnosed to have active pulmonary tuberculosis are given institutional supervised chemotherapy till cure is achieved.

In our study it was observed that patients were diagnosed to have pulmonary tuberculosis solely on the basis of radiological findings and started on ATT even when symptoms were of short duration or patients were asymptomatic and sputum examination for AFB was negative. The diagnosis of active pulmonary tuberculosis cannot be made solely based on single chest radiograph. The presence of consolidation is often equated with activity and calcified nodules with inactivity.5 There have been patients with focal consolidation in apical and posterior segments of upper lobe who have had repeated negative sputum cultures and whose lesions have remained unchanged even with adequate chemotherapy. At the other end, are calcified nodules that pathologically show active granulomatous inflammation and contain viable tubercle bacilli.5 In our study, all asymptomatic patients with predominant cystic, reticular or calcific opacities showed no change in opacities after one year follow up. Acinar opacities seen in six patients showed complete resolution on follow up after initial course of antibiotics. These cases most likely had bacterial pneumonia and ATT was started on the basis of incomplete resolution of opacities after 2–3 weeks. Six immunocompetent patients with lower zone opacities were diagnosed to have active pulmonary tuberculosis on radiological basis even though lower zone involvement in immunocompetent patients is uncommon. None of these cases had active disease on follow up.

CT of chest was helpful in further delineation of opacities seen on chest radiograph. Bronchiectasis could be diagnosed in 8 patients and localized pulmonary fibrosis in three additional patients on HRCT of thorax. It was also helpful in identification of opacities in regions other than those seen on chest radiograph and as a guidance in taking BAL from areas suggestive of having active disease.

Fiber optic bronchoscopy was helpful in our patients as most of them were asymptomatic by the time they reached our center and were not able to produce sputum BAL for AFB smear and MTB culture was negative in one patient, who was smear and culture positive in previous hospital. This helped in identifying false positive sputum AFB and MTB culture. ATT was stopped in 12 patients at our center and all of them showed no evidence of disease activity on follow up. They were put on treatment predominantly based on localized reticular or cystic opacities and had localized pulmonary fibrosis or bronchiectasis.

Over-reliance on radiology as the primary means of diagnosis persists despite documentation that 50–70% of smear negative patients placed on treatment did not have tuberculosis at all.6 In our study, 97.2% patients did not have active disease who were initially diagnosed to have pulmonary tuberculosis even with minimal symptoms or short duration of illness or were asymptomatic. Uplekar et al reported that most of a group of 143 practicing doctors, which included MBBS, MD, Ayurvedic, Unani and Homeopathic doctors who dealt regularly with tuberculosis cases in their private practice, depended heavily on chest radiograph.7 Besides, wide inter and intra-observer variations in reading chest radiograph is one of the main reasons for over and under-diagnosis of tuberculosis, which again depends on experience in reading chest radiograph.8,9 Misdiagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis occurs on radiologic basis because many non-tuberculous respiratory diseases have symptoms, signs as well as radiological abnormalities similar to those of pulmonary tuberculosis.9 As such, under RNTCP, there is a provision for making radiological examination, if two sputum specimens are smear negative and the patient does not show any symptomatic improvement after treatment with antibiotics for two weeks. This complementary role of radiology is, however, secondary to effective smear microscopy.

The study has revealed that diagnosing and treating tuberculosis predominantly on radiological basis is not appropriate and sputum microscopy remains the cornerstone of diagnosing pulmonary tuberculosis, supported with culture of the mycobacterium, where relevant.

Intellectual contribution

Study concept: Brig MS Barthwal, Lt Col Vikas Marwah.

Drafting and manuscript revision: Brig AK Rajput, Lt Col Vikas Marwah.

Statistical analysis: Lt Col Vikas Marwah.

Study supervision: Brig MS Barthwal.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Khatri G.R. Revised National TB Control Programme. Ind J Tub. 1999;46:157. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . 2nd ed. WHO/TB/97.220; Geneva: 1997. Treatment of Tuberculosis: Guidelines for National Programmes. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enarson D.A., Rieder H.L., Amadottir T., Trebucq A. 4th ed. International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases; Paris: 1996. Tuberculosis Guide for Low Income Countries. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins P.A. In: The Microbiology of Tuberculosis: Clinical Tuberculosis. Davies P.D.O., editor. Chapman & Hall Medical; London: 1994. pp. 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraser R.S., Pare P.D., Muller N.L., Colman N. Fraser and Pare's Diagnosis of Diseases of the Chest. 4th ed. WB Saunders; Philadelphia: 1999. Pulmonary infection – mycobacteria; p. 820. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair S.S. Significance of patients with X-ray evidence of active tuberculosis not bacteriologically confirmed. Ind J Tub. 1974;21:3. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uplekar M.W., Rangan S. Private doctors and tuberculosis control in India. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1993;74:332–337. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(93)90108-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rao K.N. Tuberculosis Association of India; 1981. Text-Book of Tuberculosis: Diagnostic Methods of Tuberculosis. 201. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lale A.P. Role of bronchoscopy and allied procedures to evaluate over-diagnosis of tuberculosis. Ind J Tub. 1999;46:193. [Google Scholar]