Abstract

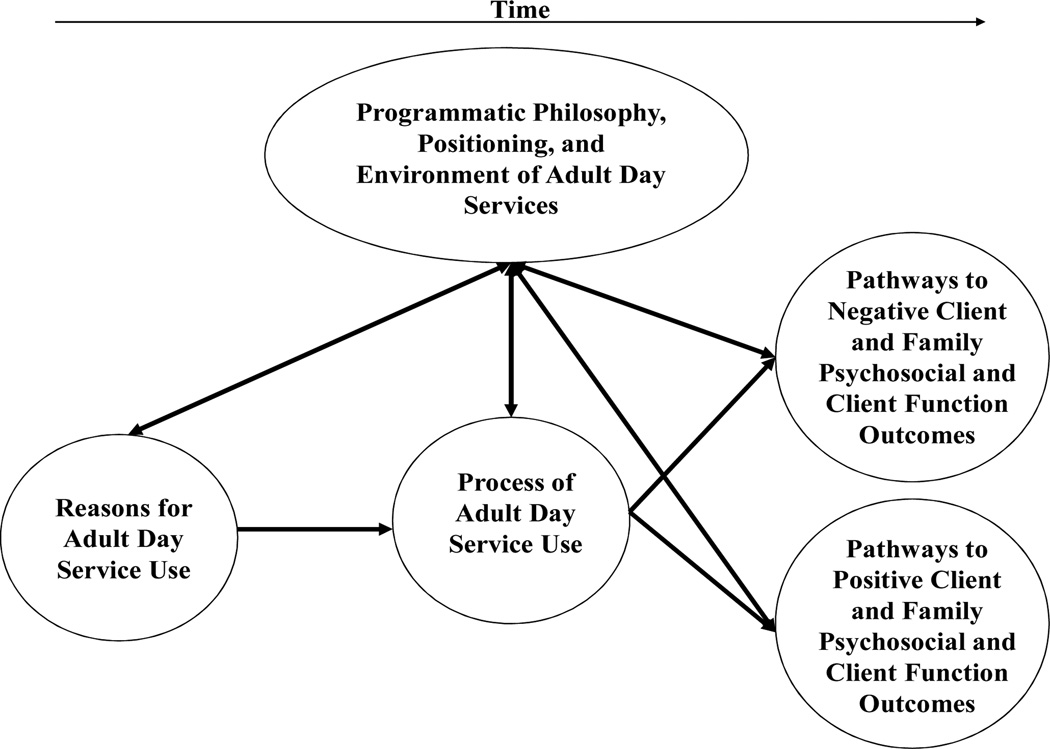

The objective of this study was to examine why and how families and older adults utilize adult day services. The current study included three months of participant observation in one rural and one suburban adult day service program in an upper-Midwestern region of the United States as well as semi-structured interviews with 14 family members of clients and 12 staff members from these programs. Several key constructs emerged that organized the multiple sources of qualitative data including programmatic philosophy, positioning, and environment of ADS; clients’ and family members’ reasons for use; the process of ADS use by families and clients; and pathways to family/client psychosocial and client functional outcomes. A number of inter-related themes emerged within each construct. The constructs identified and their potential associations among each other were used to expand upon and refine prior conceptualizations of ADS to frame future clinical and research efforts.

Introduction

Adult day service (ADS) programs offer out-of-home supervised activities and socialization for older persons or other adults. Among the goals of ADS programs are to offer families who provide care to elderly relatives with relief from day-to-day care responsibilities of disabled relatives, to enhance the functional independence and quality of life of older clients who attend ADS, and to allow clients to remain in a home/community setting for as long as possible.1 A recent national survey of ADS programs found that there are 4,600 operational programs that serve more than 260,000 people in the United States.2 Seventy-one percent of all ADS programs operate on a non-profit basis and 61% are affiliated with some other health care organization such as skilled nursing facilities or home care programs.2 Average client capacity for ADS is 51 with a 6:1 client to staff ratio.2 Nearly half of ADS clients suffer from some form of dementia, 58% of clients are women, and 69% are 65 years of age and older.2 The cost of ADS varies based on services provided and utilized and the average is $61.71 per day.2

Although research in the 1970s and early 1980s pointed to the potential benefits of ADS in improving life satisfaction and functional dependence of elderly clients, subsequent multi-site, randomized evaluations of ADS offered more ambiguous results.3 While the mixed findings suggested the limited effects of ADS use on clients’ functional outcomes, other quasi-experimental or descriptive studies indicated potential psychosocial benefits for clients such as satisfaction with services and increased life satisfaction, improved emotional well-being for family caregivers, and enhanced adaptation to nursing home admission for clients.4 A common gap among prior evaluations was that participants were often classified as to whether they used ADS or not; moreover, programmatic or policy characteristics of ADS were not considered. It generally remains unknown how size, staffing, service content, and other program-level dimensions influence key outcomes over time among users.5,6 Similarly, current research has not adequately specified how family caregivers and clients utilize ADS programs, and how this process can lead to potential benefits for family caregivers and their relatives in ADS.

Such gaps can in part be addressed with the use of more appropriate methodologies. For example, ethnographic or grounded theory approaches7–10 could yield valuable insight into those processes and components of care that appear linked to the key outcomes of ADS utilization.11–15 These methodologies can also explain those processes and components of care that appear linked to the key outcomes of ADS utilization. In doing so, constructivist/interpretive approaches may suggest: a) pathways to benefit for clients and family caregivers; and b) constructs to operationalize and measure (via quantitative data collection techniques) how clients and families use ADS and what programmatic components are more likely to result in positive outcome for these individuals.

Prior research has relied on constructivist epistemological stances and associated methodological frameworks to develop conceptual models of ADS benefit. Dabelko and Zimmerman16 postulated that ADS operates through two domains of influence: psychosocial well-being and physical function of clients. Bull and McShane (2008) examined the transition to ADS use for family caregivers of ADS clients and utilized grounded theory techniques to develop a conceptual model that described how families and older adults make the decision to utilize ADS, the adjustment process to ADS, and how families and clients integrated ADS into their everyday lives.17

The focus of the present study was to utilize semi-structured interviews and observational information to determine how ADS provides respite to family caregivers and therapeutic benefits to clients. Specifically, this study attempted to identify constructs and their relationships with each other in order to determine how and why families and clients utilize ADS, and whether such use does or does not lead to positive outcomes for clients and family members. Multiple qualitative methods were utilized to understand how potentially therapeutic activities, environmental aspects, programmatic philosophy, and social interaction facilitates client engagement and family well-being. This investigation of the process of ADS use aimed to advance current research by effectively framing clinical practice and future evaluations of ADS to examine how this important type of community-based long-term care can lead to positive outcomes for clients and their family caregivers.

Methods

The methodological framework chosen for this study incorporated elements from qualitative gerontology and grounded theory8–10,18,19 in order to develop a conceptual model (categories/constructs, themes, and theorized relationships among them) to more fully describe the process of ADS use for clients and family members. University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approval was granted for the research activities reported here (IRB#0807S39521).

Adult Day Program Settings

Two adult day programs were selected to conduct participant observation and semi-structured interviews (their names are changed to protect confidentiality). The first, referred to as Blue Lake Adult Day Center (BLADC), is located in a rural community approximately 55 miles from a large, upper-Midwestern metropolitan area in a town of 4,674 people (as of 2012). The estimated median household income in the town BLADS is located was $37,733 in 2011; estimated per capita income was $19,522. Based on 2010 U.S. Census data, the percentage of White alone residents was 96.47%.The second adult day program, Century Adult Day Services (CADS), is located in a suburb adjoining the same large, upper-Midwestern metropolitan area (population = 20,404 in 2012). The 2011 median household of the town CADS is located in was $52,442; in 2010 85.3% of the population was White alone, BLADC is a private, not-for-profit ADS and has been in operation since 2000. BLADC cost clients approximately $56 per day of attendance. Eighteen clients attended BLADC. BLADC is affiliated with a local nursing home operator but is physically located in a nearby church. CADS is also not-for-profit, has been in operation since 1990, and served 53 clients. CADS cost clients approximately $83 per day of attendance and is not affiliated with a long-term care operator. CADS occupies space in a former community hospital which has been transformed to include CADS (which is located in the former nurses’ station area), a nursing home, and several other community organizations. The staffing mix at BLADS included 3 program aides/direct care staff, 1 nurse’s aide, and 1 director. The staffing mix at CADS included 1 activity coordinator, 2 program aides/direct care staff, 1 floor director, 1 administrative/executive director of the business office (the business office at CADS also included one billing staff person), 1 owner, 1 manager of in-home services, and 1 physical therapist assistant.

Variations were apparent in client composition. The age range of clients in BLADS was 24 to 90 years of age, while in CADS the age range was from 56 to 94. Sixty-six percent and 53% of CADS and BLADS clients were women, respectively. All BLADS clients were Caucasian, while only 72% of CADS clients were Caucasian. A high proportion of clients (70% vs. 61%) in CADS and BLADS were Medicaid eligible, respectively. Both programs were open soon after 6:00 AM and closed at 6:00 PM in the evening, Monday through Friday.

Participant Observation

Participant observation was utilized to better understand the types of therapeutic activities or rehabilitative services offered in each ADS during various times of the day. A principal goal of the observational activity was to identify how and why certain activities, environmental details, and social interactions facilitated client engagement. An additional goal was to better understand the programmatic context of ADS in terms of its care philosophies and day-to-day operation.

Observations of adult day programs took place from June 2009 to August/September 2009 (with a final observational visit in May, 2010). The first author, who has extensive research experience on ADS programs and their efficacy,1,3 conducted all observations. Each program was generally observed for an hour every other week during different times and days. While a formal randomized process to identify the days and times participant observations were to occur was not used, the days and times the author attended varied and took place during the following blocks of time: at opening, during the morning activity hours, during lunch, afternoon activity hours, and client departure times. The author assumed a participant observer role;10,20 he observed activities, staff-to-staff, client-to-staff, and client-to-client interactions and also had several impromptu, unsolicited conversations with ADS directors and staff to discuss the stories of residents or the care philosophy of each ADS. The observational protocol included detailed handwritten notes of activities, the program environment, number of clients, gender of clients and staff present, room location, and client and staff location in each room as well as verbatim transcriptions of oral communication where possible.9 Usually within 24 hours following an observation notes were recorded in a handheld digital recorder. In addition to these field notes, approximately once per week theoretical and methodological notes were recorded to summarize more general impressions of each ADS and to begin to formulate concepts to explore further. These digital recordings were then transcribed into Word documents verbatim by a professional transcriptionist.

Semi-Structured Interviews

From October 2009 to May 2010 the author initiated a series of semi-structured interviews with all staff at BLADS and CADS as well as family members of clients. Both staff and family members of clients were approached by executive directors to seek permission for contact. All BLADS and CADS staff (N = 12) agreed to participate with the exception of one staff member at CADS who declined to be interviewed. ADS directors also identified family members of relatives at the ADS. ADS directors were asked to identify family members of current clients actively enrolled in their respective programs and ascertained their interest in participating. While purposive sampling would have been ideal, ADS directors were asked to identify as many potential family members as possible in order to result in enough respondents to yield rich qualitative description. Of the 16 family members identified by ADS directors, 1 declined to participate and 1 was excluded because the focus of the analysis was on ADS use for older clients. Characteristics of family and ADS staff participants are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics: Family Members and Adult Day Service Staff.

| Variable | Family Member (N = 14) |

Staff (N = 12) |

|---|---|---|

| Age |

M = 62.50 SD = 11.04 |

M = 56.42 SD = 8.79 |

| Female |

N = 9 64.3% |

N = 12 100% |

| Race | ||

| White (Alone) non-Hispanic |

N = 13 92.9% |

N = 12 100% |

| White (Alone) Hispanic |

N = 1 7.1% |

|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Not Hispanic/Latino |

N = 13 92.9% |

N = 11 91.7% |

| Not reported |

N = 1 7.1% |

N = 1 8.3% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married and/or living with partner |

N = 12 85.7% |

N = 10 83.3% |

| Divorced |

N = 2 14.3% |

|

| Never married |

N = 2 6.7% |

|

| Number of living children |

M = 3.00 SD = 1.75 |

- |

| Formal education | ||

| Did not complete high school |

N = 1 7.1% |

- |

| High school degree |

N = 4 28.5% |

N = 3 25.0% |

| Some college courses |

N = 1 7.1% |

N = 1 8.3% |

| Associate’s degree/2-year college |

N = 1 7.1% |

N = 4 33.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree/4-year college |

N = 6 42.9% |

N = 3 25.0% |

| Graduate degree |

N = 1 7.1% |

N = 1 8.3% |

| Total household income | ||

| $10,000–$14,999 |

N = 1 7.1% |

|

| $20,000–$24,999 |

N = 3 21.4% |

|

| $25,000–$29,999 |

N = 1 7.1% |

|

| $30,000–$59,999 |

N = 3 21.4% |

|

| $60,000–$79,999 |

N = 2 14.3% |

|

| $80,000 or over |

N = 4 28.6% |

|

| Work status | ||

| Working at a full-time job |

N = 6 42.9% |

|

| Working at a part-time job |

N = 2 14.3% |

|

| Retired |

N = 5 35.7% |

|

| Unemployed |

N = 1 7.1% |

|

| Relationship to client | ||

| Spouse or partner |

N = 5 35.7% |

|

| Daughter or son |

N = 7 50.0% |

|

| Daughter-in-law or son-in-law |

N = 1 7.1% |

|

| Sister or brother |

N = 1 7.1% |

|

| Duration of care for relative(months) |

M = 85.57 SD = 97.40 |

|

| Primary family caregiver of client |

N = 14 100% |

|

| Hours spent caring for client during typical week |

M = 30.64 SD = 18.18 |

|

| Length of time employed at ADS (months) | - |

M = 99.17 SD = 77.54 |

| Hour per week spent at ADS on average |

M = 35.46 SD = 12.05 |

|

| Length of time it takes to travel to ADS (minutes) |

M = 14.58 SD = 12.24 |

|

NOTE: ADS = adult day service program; M = mean; SD = standard deviation

Interviews were face-to-face. All staff interviews took place in a private conference room or closed office space at each ADS. Family interviews were held in participants’ homes or in a setting preferred by the family member (e.g., a local library). Interviews were semi-structured and lasted from 45 to 60 minutes each. In addition to a standardized order of open-ended questions, participants were allowed and encouraged to discuss any other issues related to how ADS was used or why it did or did not help families or clients.18,20 A digital recorder was used to record all semi-structured interviews, and they were later transcribed verbatim by an expert transcriptionist. The semi-structured interview guides are included as supplemental material.

Data Analysis

Analysis of the open-ended data followed the steps recommended by Morse,9,10 Gubrium and Holstein,21 and Luborsky.19 Following transcription, the author initially read the hard copy of all transcripts to identify relationships and overarching ideas and patterns in field notes, semi-structured interview transcripts, and methodological/field notes. These initial reads were then followed by labeling and highlighting of key text to identify codes; this was done to later incorporate codes into larger themes and eventually a conceptual model of the process of adult day service use. Specifically, each line of hardcopy text was open-coded and assigned handwritten codes to reflect the meanings of highlighted text. Then, using nVivo 10 software22 the author re-read the transcripts and reviewed the initially assigned codes and linked similar descriptive codes together; this process continued until new codes were no longer apparent (e.g., “saturation”).23

Similar to approaches described by Morse and others,9,10,23,24 statements or topics were cross-checked and integrated across the observational and interview notes to begin to assemble a set of codes, themes (or, a set of similar codes assigned under a single label), and constructs/concepts as well as their relationships to each other. The identification of codes, themes, constructs, and their relationships to each other were developed with the goal of determining how and why families and clients utilized adult day services and how ADS use did or did not lead to positive outcomes on the part of clients and family members. The author then reviewed the final code, theme, and concept list to ensure that they adequately represented the data.

Results

One-hundred and thirty-six transcribed pages of field and methodological/theoretical notes and 360 pages of interview text were generated. A total of 459 codes were identified that were later synthesized to identify key themes, and later, constructs and their conceptual relationships with each other. While the source of codes was documented (field notes, methodological/theoretical notes, staff interview transcript, family interview transcript), all of the qualitative data were blended to contribute to and create themes and constructs.

The investigation of multiple sources of information yielded several key conceptual dimensions/constructs: the policy/environmental context of ADS; reasons why ADS was used; how ADS is used; and pathways to client/family psychosocial and client functional outcomes. These categories are organized across a temporal dimension in the conceptual model of Figure 1, and within each category/construct emerged a number of specific themes based on activities and services, client behavior, family and staff perceptions, and interaction/communication between clients, staff, and/or family members in ADS (see Table 2). Candidate quotes from observational notes and interview transcriptions that represent themes derived are presented in Table 2 due to space considerations. All names are changed to protect confidentiality.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model: The Process of Adult Day Service Use

Table 2.

Themes by Category/Concept and Representative Quotes

| Concept | Themes | Representative Participant Quotes/Field Notes/Theoretical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Programmatic Philosophy, Positioning, and Environment of ADS |

|

|

| Reasons ADS Use |

|

|

| Process of ADS Use |

|

|

| Pathways to Negative Client and Family Psychosocial, Client Function Outcomes |

|

|

| Pathways to Positive Client and Family Psychosocial, Client Function Outcomes |

|

|

| (Interviewer): That’s right. | ||

| (Family member): And I realized the care that would be needed, but realizing it and doing it are two different things. But, it wasn’t bad at all, because we had the daytime hours to do our chores or whatever we wanted, morning was kind of, you know, it’s social time. It wasn’t a big deal to get Mother ready and take her and visit with her in the car. And then in the evening it was the same. So she had a fulfilling life, like going to school or going to work. I could do my thing, <husband> could do his thing, and then we were together in the evening.” | ||

| Staff member, BLADS: “And the outings. Just in general, just having them have an outlet just seems to really be the best part.” |

NOTE: ADS = adult day services

Programmatic Philosophy, Positioning, and Environment of ADS

The “shadow” of the nursing home was apparent in interviews with staff, family members, and in participant observation. Specifically, family members and staff commented on how the atmosphere of ADS compared (positively) to nursing homes, particularly the different philosophy surrounding ADS staff training, care routines, and scheduling. Another theme apparent across the qualitative data sources was the need to promote, or effectively market, ADS programs so that more people would know about these services and also utilize them; a certain degree of frustration was evident among staff, as they seemed to be at a loss as to why the “word was not out” about CADS. The need to adopt a more business-like approach in marketing and managing ADS programs was also mentioned in interviews with staff, but this also contrasted with how some direct care staff viewed themselves and their mission. An additional tension was the current economic crisis;15 the constant specter of economic burdens placed considerable stress on how families and staff viewed the future viability of ADS programs that were never designed to focus on profit.

A key environmental and philosophical dimension of ADS programs was their community integration, or their interaction and participation in activities and events in the community outside of the ADS.25 Similarly, the degree to which client and staff lives outside of the program walls influenced and shaped the activities and services provided within the ADS context were apparent through the sharing of personal stories and staff knowledge of clients’ history and lives.

Reasons for ADS Use

The reasons why ADS programs were used was less a set of discrete factors and more a complicated process that weighed the needs of the client (socialization, need for supervision) and the family (need for relief from care responsibilities, affordability) along with interactions with the broader long-term care system (ranging from dissatisfaction with care provided in other settings/services as well as recommendations from healthcare professionals). The findings suggest the dynamics underlying why families make the decision to use ADS, as it is one that is based on the interplay between the needs of elderly clients and their families along with healthcare professionals’ willingness to recommend ADS as an appropriate service. As one of the themes that emerged in the programmatic philosophy of ADS was the need to better market these services to potential family members (see above), considering the reasons for ADS use might help better target such efforts.

Process of Use

A driving theme of ADS use was their ability, or at times their inability, to fully engage clients in various activities and services that were therapeutic (even in activities that were not initially perceived as desirable by clients). In particular, cognitive impairment and the utilization of one-to-one staff care seemed to determine the degree of that engagement.26,27 Cognitively impaired clients were sometimes segregated during meals in order for staff to more effectively serve these clients and assist them (e.g., helping these clients cut and eat their food). During large group activities cognitively impaired clients were often provided with alternative games or activities that they could actually “do.” This might have implications for stigmatization or segregation for such clients (and could constitute a threat to personhood).11,12,28,29 Moreover, incorporating cognitively impaired clients into large group activities alongside cognitively intact clients (e.g., those who could speak and understand game instructions and tasks) also appeared to lead to disengagement on the part of these clients (e.g., staring, dozing off, and so forth). These barriers to engagement for cognitively impaired clients were often overcome by staff through the use of one-to-one care interaction, personal names, and emotional validation. Indeed, one-to-one, personalized care provided by staff seemed to spark positive emotional affect and a greater degree of engagement among cognitively impaired clients.

The various sources of information also provided much greater insight into how ADS care was provided and delivered. A key theme that emerged in the process of use was client preference versus client need (see Table 2); ADS staff often had to balance what clients wanted to do (e.g., play bingo) with implementation of activities and services that were thought to stimulate clients’ memories, build socialization, and enhance function.30 In order to achieve the sometimes precarious balance between client preference and client need, staff had to assume multifaceted care roles including staff as “serving” (e.g., preparing and serving food with an eye toward hospitality), working together collaboratively, provision of intensive activity of daily living care, and offering flexible care to meet the needs of clients as well as family caregivers. The process of use and service delivery within ADS also interacted with the role of family members; families’ main engagement with ADS appeared to largely revolve around preparing the relative to attend ADS (which posed a number of challenges) as well as balancing ADS with other community-based services. Although families had some interaction and involvement in daily ADS activities, family members did not seem aware what their relatives in ADS did or which activities or services in ADS directly benefited their relatives.

Pathways to Negative and Positive Outcomes: Client and Family Psychosocial and Client Function

Among the themes that emerged throughout the participant observation as well as semi-structured interviews included the various challenges families faced when utilizing ADS. One concern was the resistance of clients to attend or utilize ADS; in addition to the various issues that arose for family members getting clients ready to go to the ADS in the morning (rehabilitative routines for clients with complex health conditions, agitation on the part of relatives, transportation arrangements), family members and staff noted a period of acclimation for clients to become comfortable in the group-based ADS environment. Individuals with varying degrees of functional or cognitive impairments, diverse ages, and other characteristics would protest to family that “I am not one of them.” This resistance might have also influenced, or was associated with, the overall lack of use by family members. The findings here emphasize that clients were not using ADS as much as staff felt they should to achieve the cognitive, social, or functional benefits of ADS therapies and services.

The available data emphasized a number of ways that ADS works for clients. In particular, the quality of person-centered care and activities in ADS benefited clients through socialization, independence, and stimulation. The activities and therapeutic services in ADS provided socialization (which was felt to be lacking for many older clients before ADS use),14,31 independence via the use of rehabilitative activities or direct physical therapy, and stimulation (largely through the adoption of activities designed to engage clients’ memory). Of note was the theme of “programmatic permeability;”25 families mentioned that the use of ADS increased clients’ activity and social engagement when at home, often represented by clients talking about the activities that took place at the ADS during the day. This combination of engaging clients at the ADS as well as improving client behavior, mood, and function at home led many families and staff to believe that ADS was responsible for clients remaining at home for as long as possible.

The benefits of ADS extended to families for several reasons. Families noted that using ADS provided them with a sense of security that their relatives were safe and cared for when attending. Other mechanisms of benefit to families included the direct engagement of ADS staff with family members, either through care planning meetings or the provision of information and training to address care-related concerns.

Discussion

There are multiple pathways to benefit for clients and their family caregivers in ADS, although the process of use is complex. Via participant observation and semi-structured interviews with ADS staff and family caregivers, the current study captures this process of use. As noted above, a current gap in the existing literature which is the focus on the overall efficacy of ADS with little attention as to how and why such programs actually help clients and families or not.3,4 Specifically, the use of multiple sources of data (i.e., “triangulation”)32 facilitated the construction of a conceptual model helped to better explain not only the outcomes that were possible in ADS (i.e., what worked), but also the process or mechanisms potentially leading to such an outcomes (e.g., person-centered care as a philosophy and process of care). Alternatively, the conceptual model indicates potential processes that could lead to less than ideal outcomes for clients or family caregivers, such as lack of client engagement because of rigid, routinized activities. The resulting model (see Figure 1) could conceptually frame future research and assessment on ADS.9,10

The conceptual model that resulted aligns with and builds upon other examples in the literature.16,17 For example, Dabelko and Zimmerman16 postulated that ADS operates through two domains of influence: psychosocial well-being and physical function of clients. The service components thought to positively influence these domains include activities, relationships, and social work services (psychosocial) as well as rehabilitation therapy, personal assistance, and specific services (medical, nursing, nutritional) (physical function). Dabelko and Zimmerman (2008) further specify the proximal and distal psychosocial and physical functional outcomes thought to be positively influenced by ADS. Proximal psychosocial outcomes include control, personal growth, and an increased sense of purpose/self-acceptance, while distal psychosocial outcomes include client’s global well-being (depressive symptoms, anxiety). Physical function outcomes included reduced activity of daily living dependencies and reduced nutritional risk (proximal) and physical well-being such as reductions in health care utilization and positive perceived health (distal). Bull and McShane17 utilized grounded theory techniques informed by semi-structured interviews with 16 family caregivers of ADS clients to develop a conceptual model that described how families and older adults make the decision to utilize ADS, the adjustment process to ADS, and how families and clients integrated ADS into their everyday lives. The basic social process underlying this model was seeking what is best for elder; and the specific stages in the ADS transition include choosing an ADS, adjusting to ADS, and integrating ADS into their lives. The current study builds on these earlier efforts and conceptual models with multiple data sources to more explicitly demonstrate possible links between how the policy and environmental characteristics of ADS might influence why families and clients decide to use ADS, how ADS is utilized, and why ADS offers benefits or not to family caregivers and older clients. For example, it has been noted in prior research that many families and/or older persons delay their use of ADS until it is too late during the course of a chronic disease to yield positive benefits; the multifaceted reasons for use that emerged in the current study could inform community-based or clinical providers why ADS is used and when these services could be best targeted to ensure effective utilization.3,33

One of this study’s most prominent limitations is the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in our sample. While the inclusion of a rural program helped to provide diversity in terms of geographic heterogeneity, the lack of overall ethnic and racial diversity among older adults in Minnesota made the inclusion of a program that served these clientele difficult. There is clearly a need for future studies of ADS to determine how these programs provide culturally tailored services and support to disabled older persons and their families.12 Purposive sampling of family members may have also allowed for greater variation in the sample, as recommended by expert qualitative methodologists. While member checking is not universally viewed as necessary in some types of qualitative methods,34,35 many methodologists agree that use of member checking is an important step to ensure the trustworthiness of interview data. When member checking was considered for the current study, the time elapsed since the completion of staff and family interviews (from 3–4 years) attenuated the utility of this technique.

As prior research has noted, community-residing older adults with various chronic conditions require holistic, preventive care. The case mix of ADS clients includes many older adults suffering from chronic conditions such as dementia, and the group-based setting of ADS represents an ideal context within which to deliver more efficient chronic care management services than traditional case-finding methods.2,36,37 However, ADS operates somewhat as a “black box” of community-based long-term care; earlier research on ADS evaluated whether ADS was “efficacious” or not within randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental designs.3 In light of less than consistent positive results on family caregiver or client outcomes, an initial conclusion was that ADS simply did not benefit clients and families consistently enough to warrant support.38,39 Lacking in these studies was a comprehensive analysis of why and how ADS services were used and operated; a research limitation that grounded theory, ethnography, and similar scientific approaches are uniquely qualified to address. In this respect, the conceptual models emerging from other investigators16,17 as well as the current study demonstrate the various dynamics that occur within and outside of ADS that benefit users and can be potentially maximized to enhance clinical practice (such as that delivered by geriatric nurses) across ADS settings.

Before the goal of enhancing practice in ADS can be achieved, however, improved clinical assessment of how clients and families utilize ADS is likely required. This becomes even more critical when considering the changing clinical landscape of ADS; recent nationwide surveys of ADS suggest that older clients in these programs are suffering from more complex, co-occurring condition who require more skilled services that registered nurses are ideally positioned to provide.2 Specifically, the rich information available from participant observation and semi-structured interview data could guide the development of more sensitive, ADS-specific measures of the process of ADS use.40 Using a) the categories identified in the conceptual model in Figure 1 (e.g., philosophy/programmatic environment of ADS; why ADS is used; how ADS is used; client and family member outcomes) as the constructs of interest to measure; b) the themes in Table 2 as the actual measurement scales; and c) specific quotes or observation notes as the basis for instrument items, a set of measures ascertaining the various key dimensions of ADS utilization are possible. The grounding of ADS items in quotes and observational notes could yield items for potential measurement instruments that have strong face (i.e., the measure appear to measures what it intends to) and content (i.e., items of the measure assess the entirety of the construct to be measured) validity in the study of ADS use. Grounding the operationalization of ADS use in theoretically rich qualitative data can perhaps traverse an existing gap in the study of ADS effectiveness by creating measures and assessment tools that are more grounded in the expectations, preferences, and achievable benefits of ADS for families, clients, and staff. These efforts could then direct nurses to provide the most effective holistic care to elderly clients in ADS.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This research was supported by grant K02029480 from the National Institute on Aging to Dr. Gaugler.

References

- 1.Gaugler JE, Dabelko-Schoeny H, Fields N, Anderson KA. Selecting adult day services. In: Craft-Rosenberg M, Pehler SR, editors. Encyclopedia of family health. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2011. pp. 930–932. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dabelko-Schoeny H, Anderson KA. [Cited July 17, 2013];The MetLife National Study of Adult Day Services: Providing Support to Individuals and Their Family Caregivers. 2010 Available https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2010/mmi-adult-day-services.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaugler JE, Zarit SH. The effectiveness of adult day services for disabled older people. J Aging Soc Policy. 2001;12:23–47. doi: 10.1300/J031v12n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fields NL, Anderson KA, Dabelko-Schoeny H. The effectiveness of adult day services for older adults: a review of the literature from 2000 to 2011. J Appl Gerontol. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0733464812443308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCann JJ, Hebert LE, Li Y, et al. The effect of adult day care services on time to nursing home placement in older adults with Alzheimer's disease. Gerontologist. 2005;45:754–763. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen-Mansfield J, Lipson S, Brenneman KS, Pawlson LG. Health status of participants of adult day care centers. J Health Soc Policy. 2001;14:71–89. doi: 10.1300/J045v14n02_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbin JM. The Corbin and Strauss chronic illness trajectory model: An update. Sch Inq Nurs Pract. 1998;12:33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morse JM, Niehaus L. Mixed method design: Principle and procedures (developing qualitative inquiry) Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morse JM, Field PA. Qualitative research methods for health professionals. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyman KA. Day in, day out with Alzheimer's: Stress in caregiving relationships. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore KD. Interpreting the “hidden program” of a place: An example from dementia day care. J Aging Stud. 2004;18:297–320. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beisecker AE, Wright LJ, Chrisman SK, et al. Family caregiver perceptions of benefits and barriers to the use of adult day care for individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Res Aging. 1996;18:430–450. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salari SM, Rich M. Social and environmental infantilization of aged persons: Observations in two adult day care centers. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2001;52:115–134. doi: 10.2190/1219-B2GW-Y5G1-JFEG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson KA, DabelkoSchoeny HI, Tarrant SD. A constellation of concerns: Exploring the present and the future challenges for adult day services. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2012;24:132–139. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dabelko HI, Zimmerman JA. Outcomes of adult day services for participants: a conceptual model. J Appl Gerontol. 2008;27:78–92. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bull MJ, McShane RE. Seeking what's best during the transition to adult day health services. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:597–605. doi: 10.1177/1049732308315174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaufman SR. In-depth interviewing. In: Gubrium JF, Sankar A, editors. Qualitative methods in aging research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication, Inc; 1994. pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luborsky MR. The identification and analysis of themes and patterns. In: Gubrium JF, Sankar A, editors. Qualitative methods in aging research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daly KJ. Qualitative methods for family studies & human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gubrium JF, Holstein JA. Analyzing talk and interaction. In: Gubrium JF, Sankar A, editors. Qualitative methods in aging research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- 22.QSR International Pty Ltd. [Cited on July 17, 2013];NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. 2012 Available http://www.qsrinternational.com/products_nvivo.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shippee TP. On the edge: balancing health, participation, and autonomy to maintain active independent living in two retirement facilities. J Aging Stud. 2012;26:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003;15:85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rowles GD, Concotelli JA, High DM. Community integration of a rural nursing home. J Appl Gerontol. 1996;15:188–201. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasselkus BR. The meaning of activity: day care for persons with Alzheimer disease. Am J Occup Ther. 1992;46:199–206. doi: 10.5014/ajot.46.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brataas HV, Bjugan H, Wille T, et al. Experiences of day care and collaboration among people with mild dementia. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2839–2848. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyman KA. Staff stress and treatment of clients in Alzheimer's care: a comparison of medical and non-medical day care programs. J Aging Stud. 1990;4:61–79. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith M, Kolanowski A, Buettner LL, et al. Beyond bingo: meaningful activities for persons with dementia in nursing homes. Ann Long Term Care. 2009;17:22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valadez AA, Lumadue C, Gutierrez B, et al. Las comadres and adult day care centers: the perceived impact of socialization on mental wellness. J Aging Stud. 2006;20:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greene JC, Caracelli VJ, Graham WF. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1989;11:255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox C. Findings from a statewide program of respite care: a comparison of service users, stoppers, and nonusers. Gerontologist. 1997;37:511–517. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morse JM, Barrett M, Mayan M, Olson K, Spiers J. Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. Int J Qual Methods. 2002;1:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: The problem of rigor in qualitative research revisited. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1993;16:1–8. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mezey M, Boltz M, Esterson J, Mitty E. Evolving models of geriatric nursing care. Geriatr Nurs. 2005;26(1):11–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jennings-Sanders A. Nurses in adult day care centers. Geriatr Nurs. 2004;25(4):227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callahan JJ. Play it again Sam — there is no impact. The Gerontologist. 1989;29(1):5–6. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flint AJ. Effects of respite care on patients with dementia and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 1995;7(4):505–517. doi: 10.1017/s1041610295002249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.