Abstract

Purpose

To investigate the cone photoreceptor mosaic in eyes with pseudodrusen as evidenced by the presence of subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDD) and conventional drusen using adaptive optics (AO) imaging integrated into a multimodal imaging approach.

Design

Observational case series

Participants

Eleven patients (11 eyes) with pseudodrusen and 6 patients (11 eyes) with conventional drusen

Methods

Consecutive patients were examined using near-infra-red reflectance (IR) confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) and eye-tracked spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) and flood-illuminated retinal AO camera of non-confluent pseudodrusen or conventional drusen. Correlations were made between the IR-SLO, SD-OCT and the AO images. Cone density analysis was performed on AO images within 50 × 50 µm windows in 5 regions of interest overlying and in 5 located between SDD or conventional drusen with the same retinal eccentricity.

Main Outcome Measures

Cone densities in the regions of interest.

Results

The pseudodrusen correlated to subretinal accumulations of material in SD-OCT imaging and this was confirmed in the AO images. Defects in the overlying ellipsoid zone band as seen by SD-OCT were associated with SDD but not conventional drusen. The mean (±standard deviation) cone density was 8,964 (± 2,793) cones/mm2 between the SDD and 863 (± 388) cones/mm2 over the SDD, a 90.4% numerical reduction. By comparison the mean cone packing density was 9,838 (± 3,723) cones/mm2 on conventional drusen and 12,595 (± 3,323) cones/mm2 between them, a 21.9% numerical reduction. The difference in cone density reduction between the two lesion types was highly significant (P<<0.001).

Conclusions

The pseudodrusen in these eyes correlated with subretinal deposition of material in multiple imaging modalities. Reduced visibility of cones overlying SDD in the AO images can be due to several possible causes including a change in their orientation, an alteration of their cellular architecture, or absence of the cones themselves. All of these explanations imply that decreased cone photoreceptor function is possible, suggesting eyes with pseudodrusen appearance may experience decreased retinal function in age-related macular degeneration independent of choroidal neovascularization or retinal pigment epithelial atrophy.

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a progressive disorder and the leading cause of irreversible visual impairment in individuals over the age of 65 years in the developed world.1–3 Drusen are a hallmark of non-neovascular AMD. Two main clinical phenotypes, conventional drusen and pseudodrusen, are both significantly associated with late AMD.4 The distinction between conventional drusen and pseudodrusen has been made first clinically by Mimoun and colleagues5 in 1990. They identified pseudodrusen as a different type of drusen based on enhanced visibility using blue light illumination and called them “les pseudo-drusen visible en lumière bleue”.5

The Sarks and coworkers described accumulations of membranous debris, the distinguishing component of soft drusen, on apical and basal aspects of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) in areas surrounding geographic atrophy.6 They did not make a clinical correlate, but the fundus photographs in their paper showed dot-like structures surrounding the geographic atrophy. Rudolf and colleagues described 3 eye bank eyes with subretinal deposition of drusenoid material that shared many histologic characteristics with soft drusen, except for location.7 Unlike conventional drusen on the inner portion of Bruch’s membrane external to the RPE, subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDD) were found internal to the RPE. Zweifel and associates demonstrated eyes with pseudodrusen have collections of material in the subretinal space as seen using spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) that have the size and shape corresponding to the pseudodrusen seen in color fundus photographs.8 They made the link between the material visualized in vivo and that seen in the histopathologic studies.6, 7 Later work from the same authors showed the reflectance properties conferred by the location of the material relative to the RPE would account for the enhanced visualization with blue light.9 The presence of SDD was found to be an independent risk factor for late AMD in a case control study.4 Limited published histologic data has shown photoreceptor degeneration internal to SDD.9

Photoreceptors overlying conventional drusen may show signs of degeneration in histologic study.10–12 Schumann and colleagues found that there was outer nuclear layer thinning over drusen in vivo using SD-OCT, suggesting photoreceptor loss or at least lateral displacement.13 However, there is limited data about photoreceptor distribution over drusen in vivo. Conventional imaging systems cannot visualize individual photoreceptors because lateral resolution is limited by the numerical aperture of the system used and the aberrations of the human eye. Adaptive optics (AO) has been used to improve the transverse resolution of retinal imaging by measuring the optical aberrations and compensating for them in real time with active optical elements.14, 15 Because the resolution is improved to several micrometers, cone photoreceptor packing density analysis can be performed in vivo. We present a preliminary analysis of cone photoreceptor density overlying pseudodrusen and soft drusen using AO imaging and these results were compared with multimodal imaging data.

Methods

This is a retrospective study of consecutively imaged patients with the clinical diagnosis of non-confluent pseudodrusen and soft drusen. These patients were examined in a private retinal referral practice between June 2012 and July 2013. The diagnosis of pseudodrusen and soft drusen in this study was based on combined color photograph, red-free photograph, near-infra-red reflectance (IR) confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) and spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) according to our previously established criteria.4, 8, 9 Pseudodrusen were diagnosed based on the ophthalmoscopic appearance while the material in the subretinal space as seen by OCT or adaptive optics imaging was termed SDD. The height of soft drusen was measured between Bruch’s membrane band and the inner border of the RPE band. The height of SDD was measured between the inner portion of the RPE band to the inner border of the subretinal material. OCT image measurements were made using image planimetry software (Spectralis Viewing Module 5.4.6.0; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). The integrity of the ellipsoid zone was evaluated over SDD and conventional drusen in the SD-OCT images.16 The conventional drusen evaluated were greater or equal to 63 µm in diameter, thus falling in the range of medium to large drusen.17

Patients with pseudodrusen and conventional drusen were examined with a flood-illuminated retinal AO camera (rtx-1, Imagine Eyes, Orsay, France) to assess the cone photoreceptor mosaic overlying pseudodrusen and soft drusen. All patients signed an informed consent form after receiving a full explanation of the adaptive optics imaging procedure. The study had institutional review board approvals through the Western Institutional Review Board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The color photographs were obtained with a Topcon ImageNet camera (Topcon America, Paramus, NJ). The IR-SLO images and eye-tracked SD-OCT scans were obtained with the Heidelberg Spectralis (version 1.6.1, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany).

The rtx1 Adaptive Optics Retinal Camera

The rtx1 adaptive optics retinal flood-illumination camera (Imagine Eyes, Orsay, France) is a compact device that includes a wavefront sensor (HASO 32-eye, Imagine Eyes), a correcting element (52- actuating electromagnetic deformable mirror, MIRAO 52-e, Imagine Eyes), and a low-noise, high resolution, charge-coupled device camera (Rope Scientific). The rtx1 adaptive optics system uses 2 light sources: a low-coherence superluminescent diode centered at 750 nm that is used for measuring and correcting optical aberrations and controlling the focus at the retinal layers and a light-emitting diode with a wavelength centered at 850 nm that provides uniform illumination of the retinal area imaged. Adaptive optics imaging sessions were performed with dilated pupils. Each image was obtained from an average of 40 frames of a 4° by 4° retinal area over an acquisition time of 4 seconds. Multiple images were recorded between 1 and 8 degrees of retinal eccentricity from the foveal center in the areas of SDD and soft drusen identified using combined IR and eye-tracked SD-OCT images as a guide. We carefully focused the AO camera through the depth of the retina to detect reflectivity consistent with cone inner segments overlying both SDD and soft drusen.

Post-processing Methods for Adaptive Optics Imaging

Each series of 40 images acquired by the AO camera was processed using software programs provided by the system manufacturer (CK v0.1 and AOdetect v0.1, Imagine Eyes, France). These images were registered and averaged to produce a final image with improved signal-tonoise ratio. The raw images that showed artifacts due to eye blinking and saccades were automatically eliminated before averaging. For display and printing purposes, the histogram of the resulting averaged image was stretched over a 16-bit range of gray levels. The positions of photoreceptor inner segments were computed by automatically detecting the central coordinates of small circular spots whose brightness differed from the surrounding background level. The spatial distribution of these point coordinates was finally analyzed in terms of local cell numerical density (cells/mm2 of retinal surface).

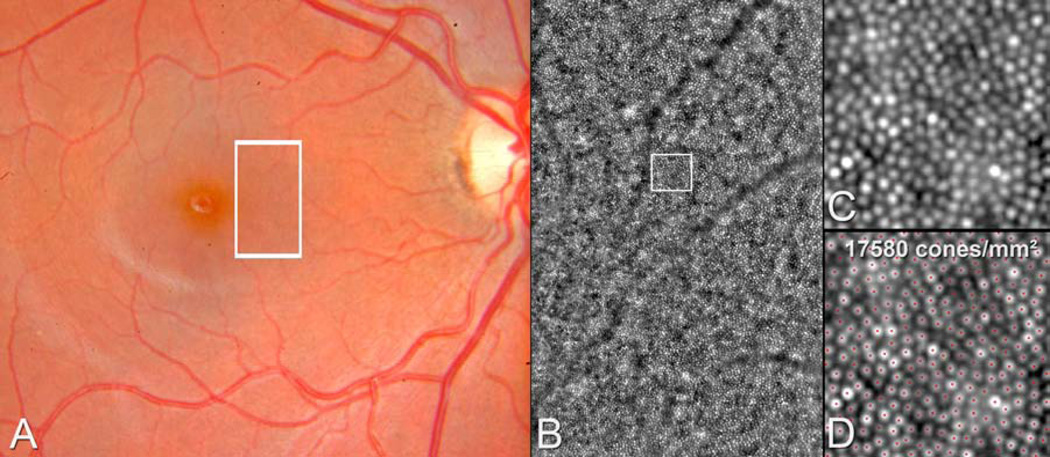

For each patient, cone packing density analysis was performed on AO images within 50 × 50 µm windows in 5 regions of interest overlying and in 5 located between SDD and soft drusen. Each measurement of cone density on top of a SDD or soft drusen was paired with a measurement in between drusen at approximately the same degree of retinal eccentricity from the foveal center in the same quadrant. The regions of interest in eyes with SDD and eyes with conventional drursen were not necessarily at the same retinal eccentricity. The cone packing density measurements were performed using software programs provided by the system manufacturer (CK v0.1 and AOdetect v0.1, Imagine Eyes, France), as described above and illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the method of cone packing density measurement using the software program provided by the system manufacturer (CK v0.1 and AO detect v0.1, Imaging Eyes, France) in the normal right eye of a 21 year-old female. A. The color photograph shows a normal retinal appearance of the posterior pole and the adaptive optics image corresponding to the area in the white rectangle (B) show a normal cone mosaic. The magnified adaptive optics images (C, D) correspond to the area in the white square. The red dots mark the structures that have been identified and counted automatically as cones by the software (D).

Correlations between the Different Modalities of Imaging

For each eye Photoshop (Photoshop CS6, Adobe System Inc., San Jose, CA) was used to superimpose the color photograph, the IR-SLO image, and each AO image manually, using the retinal vessels as landmarks. The correlation feature of the Heidelberg Spectralis was used to establish the correspondence between the IR-SLO image and the SD OCT image. Manual corrections to correlations were made using Photoshop if the retinal vessels in the SD-OCT scans did not accurately match with the IR-SLO images of the same retinal vessels. Then correlations were made between the IR-SLO and the matched color photographs, IR-SLO and the AO images.

Statistical Analysis

Correlations were made between mean cone packing density over drusen and disruption of the ellipsoid zone over drusen, the diameter and the height of the drusen in SD-OCT images, using a generalized estimating equation analysis. The statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

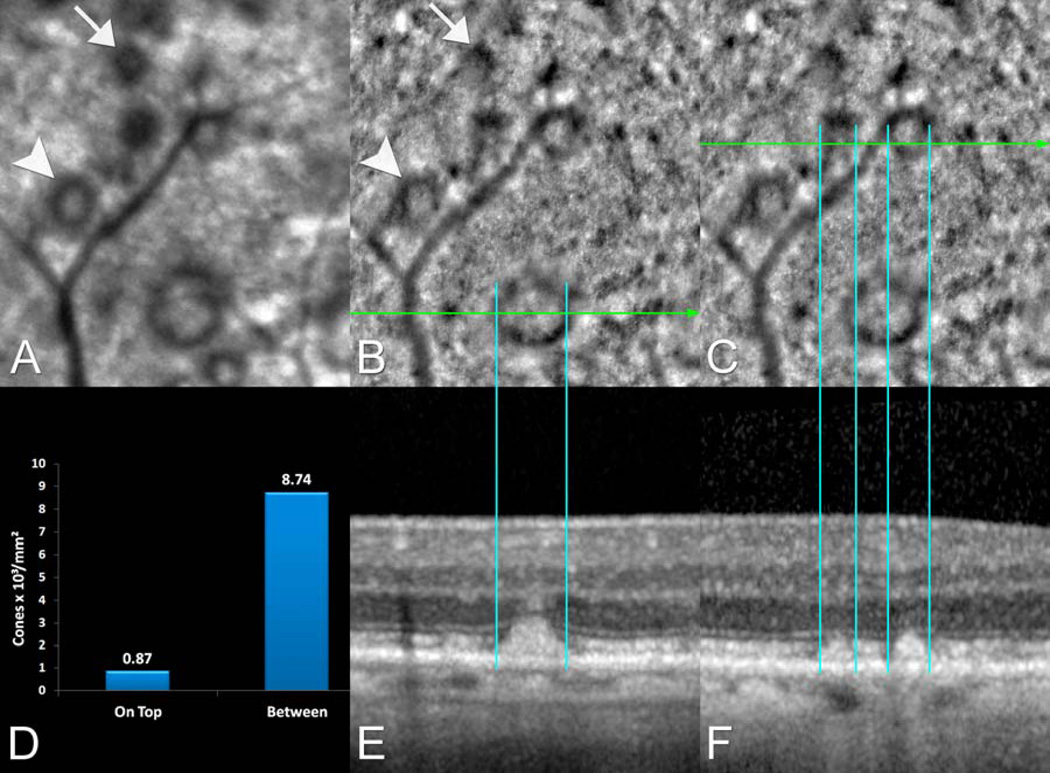

The mean (± standard deviation) age of 11 patients with SDD was 75.7 years (± 7.42 years) and 2 patients were males. The mean age of 6 patients (11 eyes) with conventional (soft) drusen was 71.7 years (± 7.27 years) and 2 patients were males. The difference in ages was not statistically significant (P=0.216). Non-exudative AMD was present in 10 eyes with SDD and 10 eyes with soft drusen. Subfoveal choroidal neovascularization was present in one eye with conventional drusen and one eye with SDD. One patient with SDD had a pigmented foveal scar due to subretinal neovascularization secondary to macular telangiectasia type 2. The areas imaged were never directly involved with exudation. The SDD identified by combined IR-SLO and SD-OCT corresponded to well-defined areas darker than the surrounding uninvolved areas in the AO images (Figures 2, 3). The size, shape and reflectivity of the SDD varied in the AO images and correlated with their size, shape and reflectivity in the corresponding IR-SLO images.

Figure 2.

Multimodal imaging of the right eye of an 84 year-old female with pseudodrusen appearance seen during the ophthalmoscopic examination. A. The near infra-red reflectance (IR) confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) image and (B and C) the corresponding adaptive optics (AO) image. D. The cone packing density was much lower over SDD than in between SDD measured in that AO image. The numbers above the bars are thousands of cones per square millimeter. Multiple subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDD) identified by combined IR-SLO (A) and (E and F) spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) correspond to well-defined areas that have somewhat similar gross reflectance characteristics in the AO image as in the IR image. Some SDD appear completely dark (white arrow) and others have a dark annulus surrounding interiors that have similar gross intensities than those of adjacent non-SDD-bearing areas (white arrowhead). The SDD appeared to be encircled by a dark annular ring of nearly constant width that corresponded to an area where the ellipsoid zone appears either tilted or disrupted in corresponding SD-OCT images (blue lines).

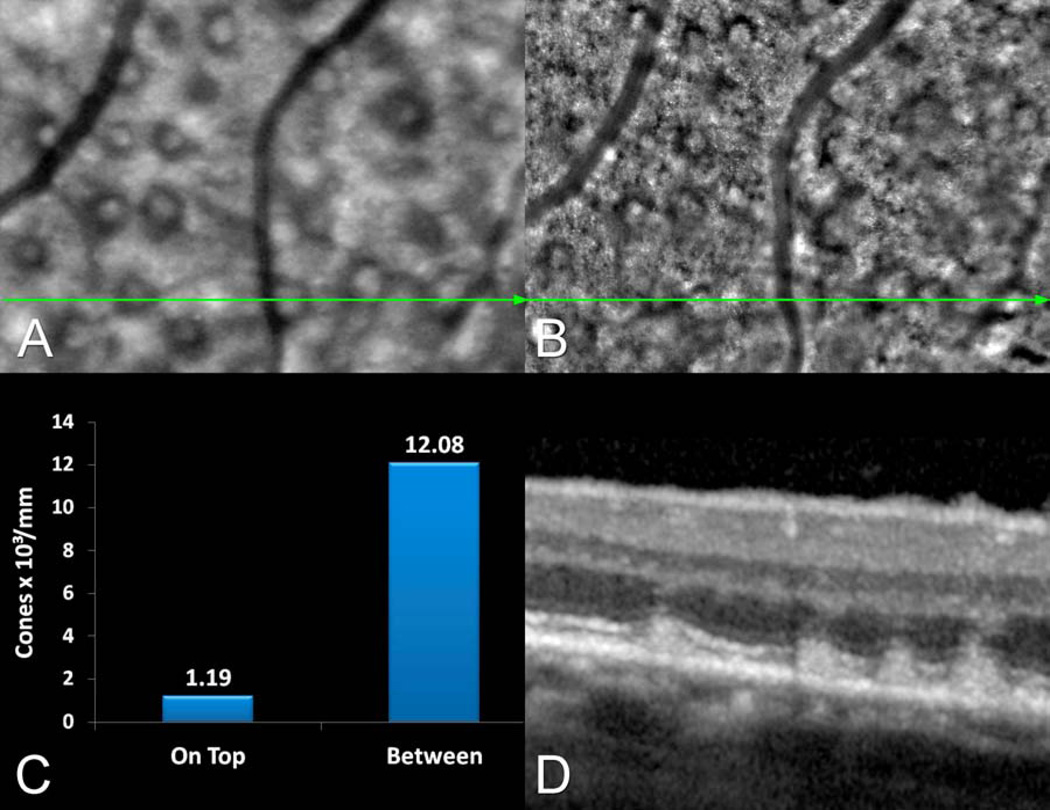

Figure 3.

This 71 year-old female had multiple pseudodrusen seen in the infra-red reflectance (IR) confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) image (A) and corresponding adaptive optics (AO) montage (B). C. There was a marked reduction in cone packing density over subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDDs) as compared with between them. D. Multiple SDD are visible in the spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) image and these colocalized with the IR-SLO image showing pseudodrusen and the AO montage image (B) of the same lesions.

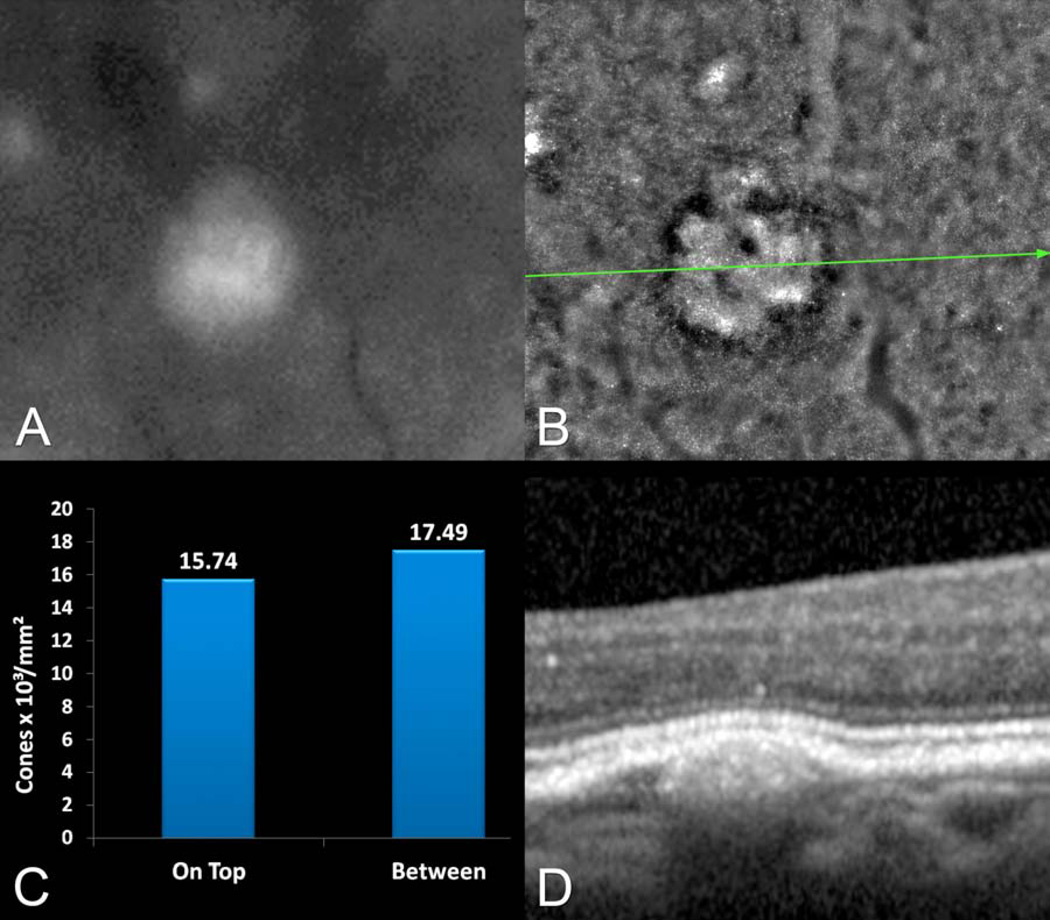

The conventional drusen identified by combined color photographs, IR-SLO and SD-OCT corresponded to areas of subtle alterations in grayscale intensity in the AO images (Figure 4). Lesion size and shape varied and showed a correspondence between the IR-SLO images and color photographs (Figure 4). The mean greatest linear diameter measured for drusen evaluated with AO imaging was 234 (± 189.8) µm, which was larger than the SDD, 119 (± 18.4) µm (P=0.086). The mean height of the conventional drusen was 60 (±20.3) µm, as compared with the height of the SDD, 74 (±13.4) µm (P=0.091). Fifty five SDD and 55 conventional drusen were analyzed.

Figure 4.

Multimodal imaging of the left eye of a 71 year-old female with multiple soft drusen seen in the ophthalmoscopic examination. A. The red-free photograph shows a druse that is seen in greater detail in (B) the adaptive optics (AO) image. The cone density showed a modest reduction over conventional drusen as compared with between them. D. The spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) shows the elevation of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) along with the retina, over a sub-RPE accumulation of material.

The mean cone packing density was 8,964 (±2,793) cones/mm2 between SDD as compared with 863 (± 388) cones/mm2 over SDD, a 90.4% reduction in cone density. The mean cone packing density was 9,838 (± 3,723) cones/mm2 over conventional drusen and 12,592 (± 3,323) cones/mm2 between conventional drusen, a 21.9% reduction. The proportions of cone density reduction over SDD as compared to conventional drusen was highly significant (P<<0.001). The ellipsoid zone was intact over all of the conventional drusen. The observed densities are within the range of densities determined histologically from grossly normal older donor retinas from similar eccentricities.18

Thirty one SDD appeared completely dark in AO images. Twenty four others had a dark annulus surrounding a central region with intensities grossly similar to those of adjacent non-SDD-bearing areas (Figure 2). The dark annulus was approximately the same width in all cases, independently of the diameter of the SDD itself (Figures 2, 3, 5) and corresponded to loss or distortion of the ellipsoid zone in corresponding SD-OCT images (Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Schematic representing the reflectivity profile of subretinal drusenoid deposit (SDD) in both the infra-red reflectance (IR) confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscope (SLO) and adaptive optics (AO) images. The smallest SDD appears completely dark and the others have a dark annulus surrounding interiors that had intensities grossly similar to those of adjacent non-SDD-bearing areas. The dark annulus is approximately the same width in all cases, independently of the diameter of the SDD itself.

DISCUSSION

In this study of both SDD and conventional drusen, imaging data from color photographs, IR-SLO, SD-OCT and AO images provided converging evidence about the site of both lesions. Subretinal drusenoid deposits localized specifically to the subretinal space and conventional drusen to the sub-RPE space. Cone density was dramatically reduced over SDD in the AO images. By comparison cone density was relatively preserved over conventional drusen in the AO images. The lack of visualization of cones over SDD in the AO images can be due to several causes impacting reflectivity including a change in their orientation, absence or shortening of the inner or outer segments or both, or loss of cones in totality. There was no difference in the heights of the respective lesions, implying a true structural difference in photoreceptor configuration. With conventional drusen the RPE is displaced by the sub-RPE material, and the retina appears to conform to variations induced by the underlying contour of the RPE monolayer. With SDD, the extracellular material physically juts into the subretinal space, in close proximity to photoreceptors, and as a consequence alters the outer retinal structure as visualized by both AO imaging and SD-OCT. To the best of our awareness, there has not been a previously published study using AO to evaluate cone density in eyes with age-related macular degeneration.

These new findings from adaptive optics imaging integrated into a multimodal approach are consistent with previously published results4, 8, 9 that pseudodrusen appearance is the result of subretinal deposition of material. These findings are not consistent with alternate hypotheses, such as the appearance is due to alterations of the RPE19 or patterns within the choroid.20 These new AO imaging observations suggest that the different imaging aspects of SDD correspond to different stages of a progressive disease, as has been previously suggested in the literature8, 21, 22 and that the material accumulates in the same tissue compartment as the photoreceptors.

The cone mosaic was previously evaluated over one conventional druse in a 45-year-old asymptomatic female23 and over large colloid drusen in a 29-year-old female.24 The results of the case reports were consistent with what was found in the present series. Reduction in cone packing density over conventional drusen was modest. In our study the packing density over SDD was distinctly decreased, and the magnitude of this reduction was apparent when compared to that over conventional drusen. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no previous report evaluating the differential loss of photoreceptors overlying SDD versus conventional drusen, by histopathology or in vivo. With AMD progression there is the potential for an increasing confluence of SDD and of conventional drusen. The outer retinal abnormalities seen over isolated SDD would likely be present in more confluent phenotypes. Thus, increasing area of SDD would be associated with more profound areas of photoreceptor absence detectable by high resolution imaging. It is also likely that there would be alterations in the cone packing density over confluent areas of conventional drusen, but given the diminution of cones was less severe over isolated conventional drusen, the decrease in packing density is likely to be not as bad as over confluent SDD. In support of this hypothesis is the long-term observation that visual acuity in eyes with conventional drusen under the fovea usually is good.25 Confluent areas of SDD are not typically observed in the fovea.

The SDD phenotype appears as more threatening for vision and quality of life than the conventional drusen phenotype. These new results from adaptive optics retinal imaging are consistent with the handicapping visual complaints of patients with peudodrusen despite a relatively preserved fundus examination and the absence of late AMD according to the current terminology. Spaide recently described outer retinal atrophy as a common finding in eyes having pseudodrusen using optical coherence tomography and proposed to add this entity as a new type of late age-related macular degeneration that can overlap with geographic atrophy and choroidal neovascularization.22

The limitations of this preliminary study are that it is an observational case series with a small number of patients. The comparison of paired within-eye observations was a strength because it obviates variability introduced by rapidly changing cone densities with increasing eccentricity and differences between patients.10, 26 Image acquisition with AO systems and the subsequent image processing is extremely time consuming, which urrently limits more widespread application. Future studies are required to evaluate eyes with different stages of SDD in AMD over time and the dynamics of photoreceptor distribution overlying different types of drusen. If cone photoreceptor function is reduced in proportion to the observed cone packing density, then eyes with pseudodrusen appearance, particularly with confluent SDD, are likely to have decreased photopic visual function. The rods were not visualized in this study, but given that rods may be affected before cones in both aging and AMD,27 the results of this study do not imply that visual function mediated by rods will be normal. As a consequence we have started a prospective study examining functional tests, including microperimetry, in relation to lesion type. In addition we have begun to examine the histologic characteristics of photoreceptors over collections of SDD in autopsy eyes.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This work was supported by the LuEsther T. Mertz Retinal Research Foundation. CAC is supported by NEI EY06109 with institutional support from the EyeSight Foundation of Alabama and Research to Prevent Blindness Inc.

Financial disclosures: Richard F. Spaide: Topcon: Consultant, Royalties; Thrombogenics: Consultant, Bausch and Lomb, Consultant; Christine A. Curcio: Genentech, research support: Hoffman-LaRoche, consultant; Rinat Neuroscience/Pfizer, research support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Adaptive optics imaging showed the cone density was dramatically reduced over subretinal drusenoid deposits as compared with similarly sized conventional drusen. This reduction may result from a change in cone orientation, architecture, or even absence.

References

- 1.Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Causes and prevalence of visual impairment among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122:477–485. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein R, Klein BE, Jensen SC, Meuer SM. The five-year incidence and progression of age-related maculopathy: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:7–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell P, Smith W, Attebo K, Wang JJ. Prevalence of age-related maculopathy in Australia. The Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1450–1460. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30846-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zweifel SA, Imamura Y, Spaide TC, et al. Prevalence and significance of subretinal drusenoid deposits (reticular pseudodrusen) in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1775–1781. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mimoun G, Soubrane G, Coscas G. Macular drusen [in French] J Fr Ophtalmol. 1990;13:511–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarks JP, Sarks SH, Killingsworth MC. Evolution of geographic atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. Eye (Lond) 1988;2:552–577. doi: 10.1038/eye.1988.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudolf M, Malek G, Messinger JD, et al. Sub-retinal drusenoid deposits in human retina: organization and composition. Exp Eye Res. 2008;87:402–408. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zweifel SA, Spaide RF, Curcio CA, et al. Reticular pseudodrusen are subretinal drusenoid deposits. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:303–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spaide RF, Curcio CA. Drusen characterization with multimodal imaging. Retina. 2010;30:1441–1454. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3181ee5ce8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curcio CA, Medeiros NE, Millican CL. Photoreceptor loss in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1236–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson PT, Brown MN, Pulliam BC, et al. Synaptic pathology, altered gene expression, and degeneration in photoreceptors impacted by drusen. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4788–4795. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson PT, Lewis GP, Talaga KC, et al. Drusen-associated degeneration in the retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:4481–4488. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuman SG, Koreishi AF, Farsiu S, et al. Photoreceptor layer thinning over drusen in eyes with age-related macular degeneration imaged in vivo with spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:488–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofer H, Chen L, Yoon GY, et al. Improvement in retinal image quality with dynamic correction of the eye's aberrations. [Accessed September 14, 2013];Opt Express. 2001 8:631–643. doi: 10.1364/oe.8.000631. [serial online] Available at: http://www.opticsinfobase.org/oe/abstract.cfm?uri=oe-8-11-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang J, Williams DR, Miller DT. Supernormal vision and high-resolution retinal imaging through adaptive optics. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 1997;14:2884–2892. doi: 10.1364/josaa.14.002884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spaide RF. Questioning optical coherence tomography. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:2203–2204. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferris FL, III, Wilkinson CP, Bird A, et al. Beckman Initiative for Macular Research Classification Committee. Clinical classification of age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:844–851. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Curcio CA, Millican CL, Allen KA, Kalina RE. Aging of the human photoreceptor mosaic: evidence for selective vulnerability of rods in central retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:3278–3296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith RT, Chan JK, Busuoic M, et al. Autofluorescence characteristics of early, atrophic, and high-risk fellow eyes in age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:5495–5504. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sohrab MA, Smith RT, Salehi-Had H, et al. Image registration and multimodal imaging of reticular pseudodrusen. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:5743–5748. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Querques G, Canoui-Poitrine F, Coscas F, et al. Analysis of progression of reticular pseudodrusen by spectral domain-optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:1264–1270. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-9063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spaide RF. Outer retinal atrophy after regression of subretinal drusenoid deposits as a newly recognized form of late age-related macular degeneration. Retina. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31829c3765. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Godara P, Siebe C, Rha J, et al. Assessing the photoreceptor mosaic over drusen using adaptive optics and SD-OCT. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2010;41(suppl):S104–S108. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20101031-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Querques G, Massamba N, Guigui B, et al. In vivo evaluation of photoreceptor mosaic in early onset large colloid drusen using adaptive optics. [Accessed September 14, 2013];Acta Ophthalmol. 2012 90:e327–e328. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02228.x. [letter] [report online]. Available at: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1755-3768.2011.02228.x/pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leibowitz HM, Krueger DE, Maunder LR, et al. The Framingham Eye Study monograph: An ophthalmological and epidemiological study of cataract, glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, macular degeneration, and visual acuity in a general population of 2631 adults, 1973–1975. Surv Ophthalmol. 1980;24(suppl):335–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Curcio CA, Sloan KR, Kalina RE, Hendrickson AE. Human photoreceptor topography. J Comp Neurol. 1990;292:497–523. doi: 10.1002/cne.902920402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson GR, Owsley C, Curcio CA. Photoreceptor degeneration and dysfunction in aging and age-related maculopathy. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1:381–396. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]