Abstract

BACKGROUND

The King-Devick (KD) test measures the speed of rapid number naming, and is postulated to require fast eye movements, attention, language, and possibly other aspects of cognitive functions. While used in multiple sports concussion studies, it has not been applied to the field of movement disorders.

METHODS

Forty-five Parkinson's disease (PD), 23 essential tremor (ET), and 65 control subjects were studied. Subjects performed two trials of reading out loud single-digit numbers separated by varying spacing on three test cards that were of different formats. The sum time of the faster trial was designated the KD score and compared across the three groups.

RESULTS

PD patients had higher (worse) KD scores, with longer reading times compared to ET and control subjects (66 seconds vs. 49 sec. vs. 52 sec., p < 0.001, adjusting for age and gender). No significant difference was found between ET and control (Δ = −3 seconds, 95% CI: −10 to 4).

CONCLUSIONS

This is the first study of the King-Devick Test in Parkinson's disease. PD patients were found to have a slower rapid number naming speed compared to controls. This test may be a simple and rapid bedside tool for quantifying correlates of visual and cognitive function in Parkinson's disease.

Keywords: Parkinson's disease, eye movements, cognitive function

Introduction

Non-motor symptoms are well recognized in Parkinson's disease (PD) patients, even early in their disease process. Although clinicians routinely assess many non-motor symptoms such as those involving cognition, mood, and sleep, visual complaints are rarely evaluated quantitatively. PD patients frequently complain of blurred vision, double vision, and difficulty with reading. The underlying cause of these visual symptoms is not always well understood as many of these patients have normal or near normal visual acuity.

In addition to limb and axial motor symptoms, PD patients have ocular motor abnormalities. Studies have reported abnormal visual scanning (1), saccadic eye movement impairment (1,2), and deficiency in eye movement planning and target anticipation (2,3) in PD. Existing literature mainly focuses on laboratory recordings using electro-oculography or video-based eye tracking systems to examine saccades, antisaccades, ocular pursuit, and fixation tasks as quantitative parameters for ocular motor evaluation. The study of eye movements is important because it provides powerful insights into neural control of volitional and reflexive processes (2). However, since specialized equipment is required, the current eye movement studies are often done in research setting instead of clinical practice, and patient access may be limited.

The objective of our study was to find an easy-to-use quantitative bedside tool to evaluate visual function of PD patients. The King-Devick (KD) test is a rapid number naming test that requires saccadic eye movements to perform, and is postulated to also capture attention, language, and possibly other aspects of cognitive function according to recent sports-related concussion research (4,5). This test takes about two minutes to perform and can be done in a routine office visit. To our knowledge, this is the first study using the KD test to evaluate ocular motor function of Parkinson's disease patients.

Patients and Methods

SUBJECTS

Forty-five PD, 23 essential tremor (ET), and 65 control subjects were studied. Subjects were tested in the movement disorders clinic at Mayo Clinic Arizona, or in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders (AZSAND) by the Arizona PD Consortium/Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program. All participants signed written informed consents approved by the institutional IRBs. PD was clinically diagnosed according to the UK Brain Bank criteria, i.e., the presence of two of three cardinal features (resting tremor, bradykinesia, and rigidity) without atypical features (including early falls, early dementia, gaze palsy, early marked autonomic disturbance, fluctuating confusional states) or obvious secondary cause (such as stroke, drugs, toxins, arthritis). Subjects with dementia and those with a history of macular degeneration, glaucoma, untreated cataracts, or blindness were excluded from the study. Subjects were permitted to wear corrective lenses. The Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) was performed for all subjects.

KING-DEVICK TEST

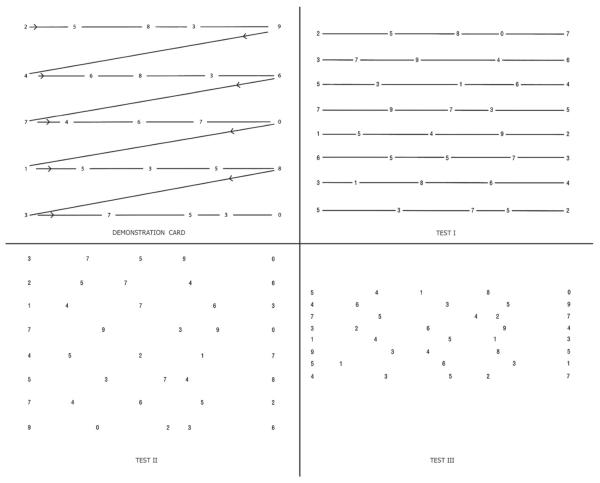

The King-Devick test consists of a demonstration card and three test cards with a series of single-digit numbers separated by varying spacing, either with or without a connecting line between numbers (Figure 1). Participants started with a demonstration card and read the numbers out loud from left to right and top to bottom, as quickly as possible and without making errors. The three test cards were then read in order in two consecutive trials. The sum time of the three test cards from the faster trial was designated the final test score. Accuracy was important; if errors were not immediately corrected, the score was not valid. The mean KD scores from the three groups were compared by single factor analysis of variance. Adjusted means were compared by using a generalized linear model with terms for age and gender.

Figure 1.

Demonstration and test cards for the King–Devick (KD) Test for rapid number naming. To perform the KD test, participants were asked to read the numbers on each card from left to right as quickly as possible without making any errors. Following completion of the demonstration card (upper left), subjects are then asked to read each of the three test cards in the same manner. The times required to complete each card were recorded in seconds using a stopwatch. The sum of the three test card time scores constitutes the summary score for the entire test, the KD time score.

Results

PD subjects were younger (mean ± SD, 73.1 ± 8.4 years) compared to ET (80.8 ± 4.8 years) and control subjects (80.0 ± 6.3 years). There were more men in the PD group (67% PD vs. 43% ET vs. 32% Control). Disease duration for the PD group was 7.2 ± 5.9 years (range 1 to 25 years). The mean UPDRS part III score was 20.5 ± 11.8, and Hoehn and Yahr staging was 2.2 ± 0.7.

The mean KD score for PD (63 ± 18 seconds) was higher (worse) compared to scores for ET (51 ± 13 sec) and control subjects (53 ± 13 sec), p = 0.001 (Figure 2). After adjusting for age and gender, the mean KD score remained higher in PD (66 sec) than ET (49 sec) and control (52 sec), p < 0.001. No significant difference was found between ET and control (Δ = −3 sec, 95% CI: −10 to 4). For the PD group, the correlation between KD scores and disease duration showed a linear correlation coefficient of r = 0.25 (95% CI −0.06 to 0.51, p = 0.11). Similarly for UPDRS part III scores, the correlation coefficient was 0.23 (95% CI −0.07 to 0.49, p = 0.13). Because of the small sample size of the PD group, the significance of these correlations was difficult to assess.

Figure 2.

Box-Whisker plot of KD scores. The lines in the box represent the medians, and boxes delineate the interquartile range (25th–75th percentiles). Whiskers represent the range of observations. * p = 0.001, single factor analysis of variance.

Discussion

In addition to motor symptoms, Parkinson's disease patients often develop a wide range of visual problems during their disease process. A change in their vision may be due to alterations in various factors including but not limited to visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, color discrimination, eye movements, visual perception, visuospatial processing, and visual hallucination. Some of these parameters such as visual acuity, visual perception, and visuospatial processing can be assessed clinically by routine ophthalmological exam or neuropsychological testing, while others require specialized laboratory equipments. The evaluation of eye movements is usually done by formal laboratory testing using electro-oculography or video-based eye tracking systems. The purpose of our study was to determine whether the King-Devick test, a short test based on rapid number naming, could be used as a bed-side tool to quantify ocular motor function and its associated cognitive correlate.

Abnormal eye movements in PD have been well described by formal laboratory studies. A meta-analysis of 47 studies revealed prolongation of saccadic latency in Parkinson's disease patients compared to controls (6). Both visual guided and memory guided saccades were impaired in PD patients (7,8). A reduction in saccadic amplitude could be observed early in the disease course (8), while increased saccade latency did not occur until later stages (7) and was associated with cognitive decline (8).

According to the current model of neurophysiology, accurate rapid eye movement control is generated by integrating cortical input from the frontal, supplemental, and parietal eye fields through circuits of thalamus, basal ganglia, and the superior colliculus (9). Some of these neuronal pathways are involved in the neurodegeneration of Parkinson's disease. In addition, PD targets the fronto-parietal networks of attention and executive function. The close anatomical relationship between ocular motor, visual, and higher cognitive functions may explain the visuospatial, visuoperceptual, and executive function impairment in PD patients (10). Two recent reports found that impairment in several saccadic eye movement parameters including error rates, visual exploration strategies, prolonged fixation time, and saccadic latency correlated with cognitive dysfunction ranging from mild cognitive impairment to dementia in PD patients (9,11).

In this proof of concept study using the King-Devick test as a bedside tool, PD patients performed worse on rapid number naming compared to control subjects and patients with essential tremor. The mean KD time in PD patients was 10 seconds longer than controls and 12 seconds longer than ET patients. The advantage of the King-Devik test is that it is quantitative, brief, and easy to use. It takes about two minutes to perform and can be done in the clinic setting. However, in addition to measuring saccadic eye movements, the KD test may also be capturing attention, language, and possibly other suboptimal brain function (5). In order to identify the contribution to the KD score by each individual component, data is needed to cross reference the KD test with laboratory eye movement tests and neuropsychological evaluation. Galetta and colleagues studied a group of professional hockey players and found cross-sectional associations of worse KD scores with worse scores for immediate memory in the Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC) (4). These findings potentially implicate that the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is involved in the generation of saccades and working memory, thus linking cognition to eye movements (4).

Another potential confounding factor is that bradykinesia may influence the speed of rapid number naming. Mixed results have been reported on correlation of ocular motor function and limb/axial motor function. Some of these studies found that eye movements correlated well with UPDRS motor scores (9,11,12), while others did not (3,10). In our study, KD scores did not show significant correlation with PD duration or the UPDRS motor scores, possibly due to the small sample size and heterogeneous factors such as attention, medications, mood, and cognitive function that may play a role in KD testing outcome.

In conclusion, the King-Devick test may provide a simple, brief, and quantitative way to assess visual function and its cognitive correlate that routine clinical evaluation and eye exam do not capture. It does not require specialized equipment and can be done as part of a routine office visit. Further study is needed to better define the relationship between the King-Devick test and disease progression as well as cognition.

Acknowledgement

The Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium and the Brain and Body Donation Program are supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U24 NS072026 National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson's Disease and Related Disorders), the National Institute on Aging (P30 AG19610 Arizona Alzheimer's Disease Core Center), the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract 211002, Arizona Alzheimer's Research Center), the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contracts 4001, 0011, 05-901 and 1001 to the Arizona Parkinson's Disease Consortium), and Mayo Clinic Foundation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.Matsumoto H, Terao Y, Furubayashi T, Yugeta A, Fukuda H, Emoto M, et al. Small saccades restrict visual scanning area in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011 Aug 1;26:1619–26. doi: 10.1002/mds.23683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan F, Armstrong IT, Pari G, Riopelle RJ, Munoz DP. Deficits in saccadic eye-movement control in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:784–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmchen C, Pohlmann J, Trillenberg P, Lencer R, Graf J, Sprenger A. Role of anticipation and prediction in smooth pursuit eye movement control in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord Off J Mov Disord Soc. 2012 Jul;27:1012–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.25042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galetta MS, Galetta KM, McCrossin J, Wilson JA, Moster S, Galetta SL, et al. Saccades and memory: baseline associations of the King-Devick and SCAT2 SAC tests in professional ice hockey players. J Neurol Sci. 2013 May 15;328:28–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galetta KM, Barrett J, Allen M, Madda F, Delicata D, Tennant AT, et al. The King-Devick test as a determinant of head trauma and concussion in boxers and MMA fighters. Neurology. 2011 Apr 26;76:1456–62. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821184c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chambers JM, Prescott TJ. Response times for visually guided saccades in persons with Parkinson's disease: a meta-analytic review. Neuropsychologia. 2010 Mar;48:887–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terao Y, Fukuda H, Yugeta A, Hikosaka O, Nomura Y, Segawa M, et al. Initiation and inhibitory control of saccades with the progression of Parkinson's disease - changes in three major drives converging on the superior colliculus. Neuropsychologia. 2011 Jun;49:1794–806. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson TJ, MacAskill MR. Eye movements in patients with neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013 Feb;9:74–85. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Archibald NK, Hutton SB, Clarke MP, Mosimann UP, Burn DJ. Visual exploration in Parkinson's disease and Parkinson's disease dementia. Brain J Neurol. 2013 Mar;136:739–50. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perneczky R, Ghosh BCP, Hughes L, Carpenter RHS, Barker RA, Rowe JB. Saccadic latency in Parkinson's disease correlates with executive function and brain atrophy, but not motor severity. Neurobiol Dis. 2011 Jul;43:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macaskill MR, Graham CF, Pitcher TL, Myall DJ, Livingston L, van Stockum S, et al. The influence of motor and cognitive impairment upon visually-guided saccades in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychologia. 2012 Dec;50:3338–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino S, Lanzafame P, Sessa E, Bramanti A, Bramanti P. The effect of L-Dopa administration on pursuit ocular movements in suspected Parkinson's disease. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol. 2010 Jun;31:381–5. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0180-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]