Abstract

Iron cardiomyopathy is the leading cause of death in transfusional iron overload, and men have twice the mortality of women. Since the prevalence of cardiac iron overload increases rapidly in the second decade of life, we postulated that there are steroid-dependent sex differences in cardiac iron uptake. To test this hypothesis, we manipulated sex steroids in mice having constitutive iron absorption (homozygous hemojuvelin knockout); this model mimics the myocyte iron deposition observed in humans. At four weeks of age, female mice were ovariectomized (OVX) and male mice were castrated (OrchX). Female mice received an estrogen implant (OVX+E) or a cholesterol control (OVX), while male mice received an implant containing testosterone (OrchX+T), dihydrotestosterone (OrchX+DHT), estrogen (OrchX+E), or cholesterol (OrchX). All animals received a high iron diet for eight weeks. OrchX, OVX and OVX+E mice all had similar cardiac iron loads. However, OrchX+E males had a significant increase in cardiac iron concentration compared to OrchX (p<0.01), while OrchX+T and OrchX+DHT only trended higher (p<0.06 and p<0.15, respectively). Hormone treatments did not impact liver iron concentration in either sex. When data were pooled across hormone therapies, liver iron concentration was 25% greater in males than females (p<0.01). In summary, we found that estrogen increased cardiac iron loading in male mice, but not in females. Male mice loaded 25% more hepatic iron than female mice, irrespective of the hormone treatment.

Introduction

While the availability of iron is crucial to the body, iron excess can be lethal. For this reason, plasma iron concentration is tightly regulated by a negative feedback loop involving the hepatic hormone hepcidin (1, 2). Several “iron sensor” proteins, including hemochromatosis (HFE) and hemojuvelin (HJV) (3, 4), regulate hepcidin release according to transferrin saturation (5). Hepcidin restricts cellular export of iron into the blood by binding to and degrading of the iron exporter, ferroportin, the only known iron exporter in the body (6). When ferroportin has been degraded, iron can no longer enter the bloodstream from its main sources, the enterocytes of the duodenum and macrophages that recycle old red blood cells. Hepcidin controls the flux of iron such that all labile forms can be safely bound by the carrier protein transferrin (7), preventing unregulated redox chemistry in the circulation.

Primary iron overload occurs when there is a deleterious mutation in the iron regulatory system (e.g. HFE or HJV) (8, 9). This disease is characterized by a blunted hepcidin response, resulting in high plasma iron and high transferrin saturation (10, 11). Iron overload can also occur in response to chronic blood transfusions, a condition known as secondary iron overload (12). Some patients with hemoglobinopathies (e.g. β-thalassemia) require chronic blood transfusions every 3 to 4 weeks, with each transfusion containing 400-600 times the daily absorption of iron (13). Because humans have no way of up-regulating iron excretion, transfusional iron eventually overwhelms the hepcidin regulatory system, saturates transferrin binding capacity, and deposits in the endocrine glands and the heart. Although the exact transporters responsible for extra-hepatic iron overload are not known, L-type calcium channels, T-type calcium channels, and Zip14 zinc channels have been implicated in previous animal studies (14-16).

Thalassemia is the most common genetic disease worldwide with a very high prevalence in Asia (17). While chronic blood transfusions correct the patients' anemia, they produce severe iron overload that can become lethal in the second decade of life (18). The leading cause of death in these patients is iron-mediated cardiomyopathy (19). Women with thalassemia have a 2:1 survival advantage compared to men with the disease (20); similar disparities in disease severity have been documented in hereditary hemochromatosis (21). In thalassemia, the onset of cardiac iron overload is greatest during puberty(18). Thus, we postulated that sex steroids might modulate cardiac iron loading, with androgens and estrogens acting antagonistically.

Response to sex steroids can be classified as organizational or activational (22, 23). Organizational effects persist even if steroids are later removed. An example would be steroidal actions in utero that determine male or female genitalia. Activational effects can occur throughout the lifespan and are more reversible, such as increased muscle mass caused by testosterone and the bone-strengthening effects of estrogen. We sought to determine if sex steroids have organizational effects and/or activational effects with respect to cardiac iron loading. Experiments were performed in gonadectomized mice, allowing for hormonal regulation by subcutaneous implants. Since testosterone can act through both androgenic and estrogenic mechanisms, we studied cardiac iron responses to testosterone, dihydrotestosterone and estrogen.

To evaluate possible sex differences in cardiac iron overload, we used the hemojuvelin knockout mouse (HJV KO), a model of juvenile hemochromatosis, supplemented with dietary iron. Our goal was to mimic the cardiac iron exposure found in transfusional siderosis. Although HFE mutations are more common than HJV mutations in humans, cardiac iron accumulation does not occur on an experimentally feasible timescale (many decades). The HJV mice continuously absorb iron from their diet, overcoming the high spontaneous iron elimination mechanisms found in rodents, and develop myocyte iron levels similar to that found in human adolescents with transfusional siderosis or juvenile hemochromatosis (24). Although high total cardiac iron levels can also be produced by iron dextran injections in rodents, iron is preferentially retained in cardiac phagocytic cells (which humans lack) rather than myocytes (25). Without a means to separately track changes in myocyte and phagocytic cell iron burdens, response of iron dextran models to therapies can be difficult to translate to humans. Thus, we believe that severe hemochromatosis mutants, such as HJV KO, represent the closest practical mimic to cardiac siderosis experienced in transfusional iron overload.

Methods

Animals

Mice were housed in the Animal Care Facility of Children's Hospital Los Angeles. All studies were carried out with approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Children's Hospital Los Angeles. Hemojuvelin (HJV) knockout mice were used in order to induce dietary iron overload; these mice have the background strain of 129S6/SvEvTac and were obtained from the lab of Dr. Nancy Andrews at Children's Hospital Boston (26). At four weeks of age, female mice were ovariectomized (OVX) and male mice were castrated (OrchX). Female mice received either an estrogen implant (OVX+E) or a cholesterol control (OVX); males received an implant containing testosterone (OrchX+T), dihydrotestosterone (OrchX+DHT), estrogen (OrchX+E), or cholesterol (OrchX). There were 7 mice per group; OVX and OrchX groups had 12 mice per group. The mice were placed on a high iron diet for the 8 weeks following gonadectomy (1400 ppm Fe, Newco Distributors Inc.). A high iron diet was necessary in order to overcome the rodents' up regulation of iron excretion during iron overload, a phenomena that is not seen in humans. Also, a high iron diet allowed for the development of cardiac iron loading in a short period of time. At 12 weeks of age the mice were sacrificed and the heart and liver tissue were harvested.

Gonadectomy and Hormone Implants

All surgeries were performed under Avertin anesthesia (250 mg/kg). Orchiectomy was performed via mid-line scrotal incision and ovariectomy was performed through bilateral dorsal flank incisions. Steroids were replaced at physiologic levels by Silastic implant sc. Males received a 5 mm implant (o.d. 2.16 mm, i.d. 1.02 mm, Dow Corning, Midland, MI) filled with crystalline testosterone (Steraloids, Newport, RI). Females received a similar implant of estradiol (1:1 17β-estradiol:cholesterol). These implants have been shown to restore normal male and female phenotypes in numerous previous studies (27-30).

Iron quantification

Heart and liver specimens were digested in 100% nitric acid at 80°C for 10 minutes; an equal volume of 30% H2O2 was then added and digestion continued at 80°C for an additional 10 minutes or until the tissue was completely dissolved. Digested samples were diluted with reagent grade water to 2% nitric acid concentration and analyzed by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA).

RT-PCR

RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Protect Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Tissues were excised and submerged in RNA Later solution immediately after sacrificing the mouse. Tissue samples in RNA Later solution were stored at -20°C until RNA extraction was performed. cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RT-PCR reactions were done using the Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Samples were run on a 7900 HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). Linearity of amplification was verified for all primers. Hepcidin expression was reported as percentage of β-actin expression. Cardiac iron transporters were measured as a percentage of GAPDH expression. Primer sequences were as follows: Hepcidin forward 5-CTGAGCAGCACCACCTATCTC-3, reverse 5-TGGCTCTAGGCTATGTTTTGC-3; β-actin forward 5-GACGGCCAGGTCATCACTATTG-3, reverse 5-CCACAGGATTCCATACCCAAGA-3 (31); Zip14 forward 5-GAGCCAACTGATAATCCATTGCT-3, reverse 5-GTCAACGGCCACATTTTCAA-3 (32); L-type calcium channel forward 5-GATGGGATCATGGCTTATGG-3, reverse 5-GGCCAGCTTCTTTCTCTCCT-3 (33); T-type calcium channel forward 5-ACCCTCCCCAAAGAAAGAT-3, reverse 5-GCTTACATGGGACTTTTCAG-3 (34); GAPDH forward 5-CAATGTGTCCGTCGTGGATCT-3, reverse 5-GTCCTCAGTGTAGCCCAAGATG-3 (35).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests were performed using JMP 5.1 (SAS, Cary, North Carolina). Since hormone treatment groups differed in males and females, steroid effects were evaluated in each sex separately by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Post-hoc comparisons using Dunnett's method were performed using OrchX and OVX as control populations for males and females, respectively. A two-way ANOVA was performed to assess for possible interaction between estrogen treatment and sex in determining cardiac iron concentration. When no treatment group differences were observed, data were pooled across sex and analyzed using an unpaired t-test.

Results

Hormone replacement had significant effects on heart mass in both sexes (Table 1). In females, estrogen reduced heart weight compared with OVX females (p<0.01). In males, OrchX+T males had significantly bigger hearts than OrchX (p<0.01). Body weight was significantly reduced in OVX+E vs. OVX, as well as in OrchX+E vs. OrchX (p<0.001 and p<0.01, respectively). The heart/body weight ratio was significantly altered in OrchX+T compared to OrchX males (p<0.05).

Table 1. Effects of Steroid Treatment on Body, Heart and Liver Weight.

| Group | Body weight (g) | Heart weight (g) | Liver weight (g) | Heart/Body Weight (×10ˆ3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrchX | 26.3 ± 0.9 | 0.139 ± 0.005 | 1.59 ± 0.10 | 5.3 ± 0.1 |

| OrchX+T | 27.7 ± 1.1 | 0.170 ± 0.009 * | 1.59 ± 0.08 | 6.1 ± 0.2 * |

| OrchX+DHT | 27.3 ± 0.7 | 0.145 ± 0.008 | 1.55 ± 0.04 | 5.3 ± 0.2 |

| OrchX+E | 21.5 ± 0.5 * | 0.121 ± 0.007 | 1.21 ± 0.04 * | 5.6 ± 0.4 |

| OVX | 25.4 ± 0.6 | 0.137 ± 0.005 | 1.51 ± 0.08 | 5.3 ± 0.2 |

| OVX+E | 22.0 ± 0.6 * | 0.113 ± 0.006 * | 1.40 ± 0.07 | 5.2 ± 0.3 |

Values are reported as: mean ± standard error of the mean.

P < 0.05 (Dunnett's method, with ‘OrchX’ as the control for male groups and ‘OVX’ as the control for female groups).

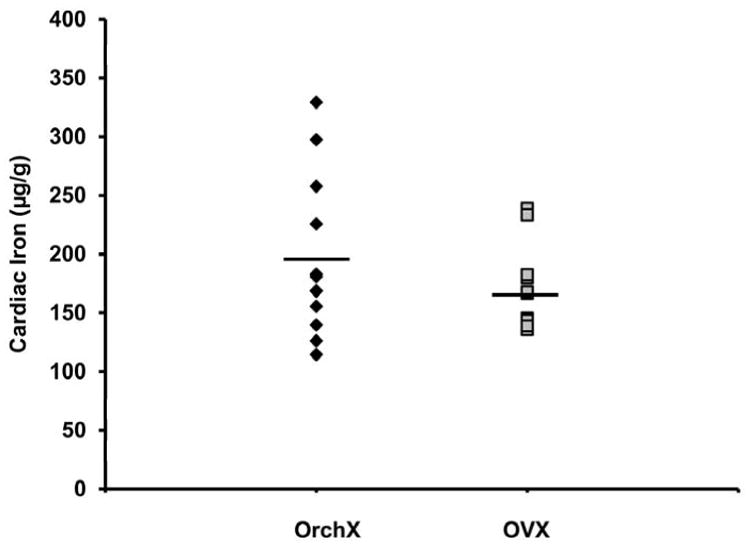

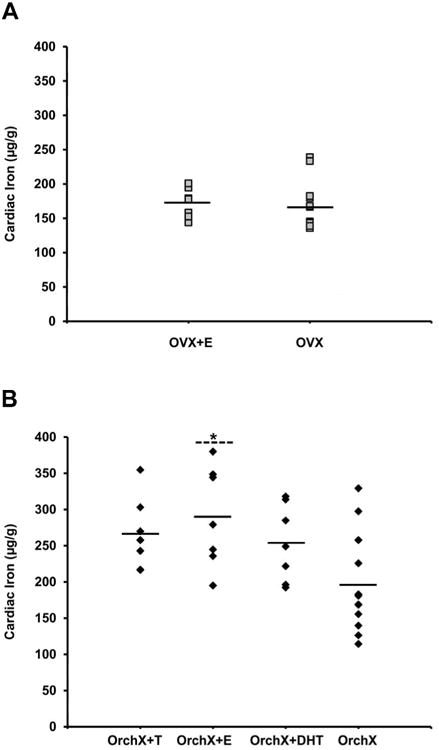

Gonadectomized males (OrchX) and females (OVX) exhibited similar cardiac iron loads of 195.6±19.7 μg/g (mean±SEM) and 165.4±9.8 μg/g, respectively (p>0.05, Fig 1). There was no effect of hormone treatment on cardiac iron in female mice, with OVX+E having a heart iron concentration of 172.4±8.1 μg/g (Fig. 2A). In contrast, a significant effect of hormone treatment on cardiac iron was revealed in males by ANOVA (p<0.05). The concentration of cardiac iron in OrchX+E males was 289.6±26.1 μg/g, compared to 195.6±19.7 μg/g for OrchX males (p<0.01) (Fig. 2B). OrchX+T cardiac iron concentration was 266.0±18.7 μg/g while OrchX+DHT was 253.7±20.0 μg/g; however, these did not reach statistical significance (p>0.05 vs. OrchX in both cases). There was an interaction between estrogen treatment and sex as measured by 2-way ANOVA, as estrogen raised cardiac iron levels in male mice but not in females (p<0.05). RT-PCR did not reveal any significant effect of sex or hormone treatment on the mRNA of Zip14, L-type or T-type calcium channels, all of which are putative transporters of non-transferrin bound iron in the heart. There was also no correlation found between the expression levels of these channels and cardiac iron (data not shown).

Fig 1.

Cardiac iron concentrations in gonadectomized male (OrchX) and female (OVX) HJV knockout mice exposed to a high iron diet for 8 weeks. No significant difference in cardiac iron was found between OrchX and OVX mice in the absence of steroid replacement. Black diamonds represent males, grey squares represent females.

Fig 2.

The effect of sex hormones on cardiac iron concentration in gonadectomized male (OrchX) and female (OVX) HJV knockout mice exposed to a high iron diet for 8 weeks. (A) Replacement with estrogen (OVX+E) had no effect on cardiac iron in female mice. (B) In males, estrogen (Orchx+E) significantly increased cardiac iron (* P = 0.01).

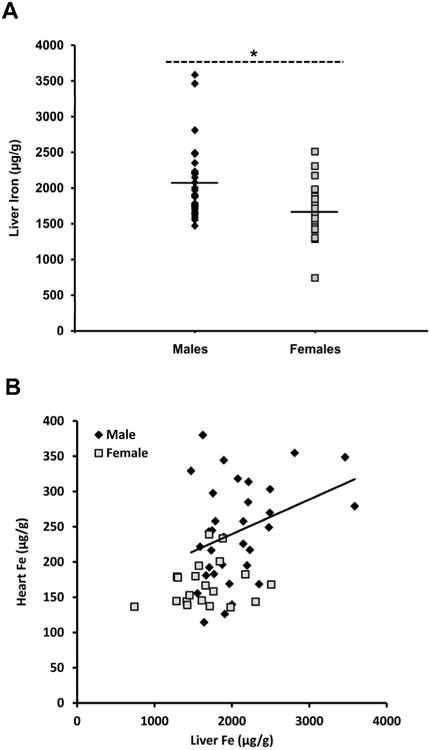

Hormone treatment did not have any significant effect on liver iron concentration in males or females. Therefore, liver iron data was pooled by sex. Liver iron concentration in males was 2041.0±77.8 μg/g compared to 1776.5±101.5 μg/g in females (p<0.01) (Fig. 3A). Cardiac and liver iron were weakly correlated in males (R2=0.12, p<0.05), although this relationship appears driven by two outliers. No relationship was seen in females (R2=0.04, p>0.05) (Fig. 3B).

Fig 3.

(A) Hepatic iron concentration in pooled samples of male and female HJV knockout mice exposed to a high iron diet for 8 weeks. (A) Males had 25% more liver iron than females, indicating greater whole body iron (* P < 0.01). (B) Males showed a weak correlation between liver iron and cardiac iron (R2=0.12, p<0.05, trendline illustrated) but females did not show any correlation (R2=0.04, p>0.05). Black diamonds represent males, grey squares represent females.

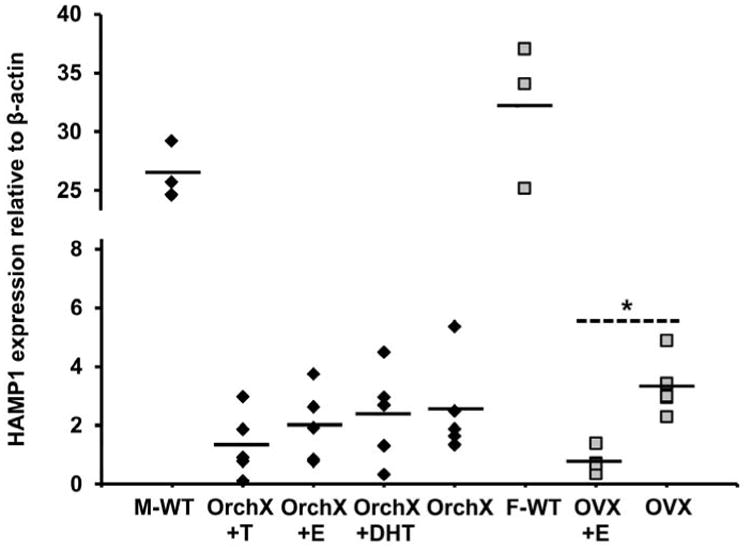

All of the mice used in our experiments were homozygous hemojuvelin knockouts. Compared to wild type mice, they should have very low hepcidin values despite high dietary iron. In mice, the functional hepcidin protein is coded by the HAMP1 gene; hepcidin expression can therefore be analyzed by measuring HAMP1 mRNA levels (36). Our male mice had 7.7% the HAMP1 mRNA of wild type males, while our female mice had 6.3% the HAMP1 mRNA of wild type females. No correlation was found between HAMP1 expression and liver Fe concentration in male or female mice (data not shown). In male mice, there was no effect of steroid treatment on HAMP1; OVX+E females did have significantly less HAMP1 than OVX (p<0.01) (Fig. 4), but the physiologic significance of this difference is unclear.

Fig 4.

HAMP1 expression relative to β-actin in male and female HJV knockout mice as well as in male and female wildtype (WT) mice. Male and female HJV knockout mice had suppressed HAMP1 expression in comparison to their wildtype counterparts. Male HJV knockout mice did not show any significant differences in HAMP1 expression due to hormone treatment. In females, OVX did have significantly more HAMP1 expression than OVX+E (* P < 0.01). Black diamonds represent males, grey squares represent females.

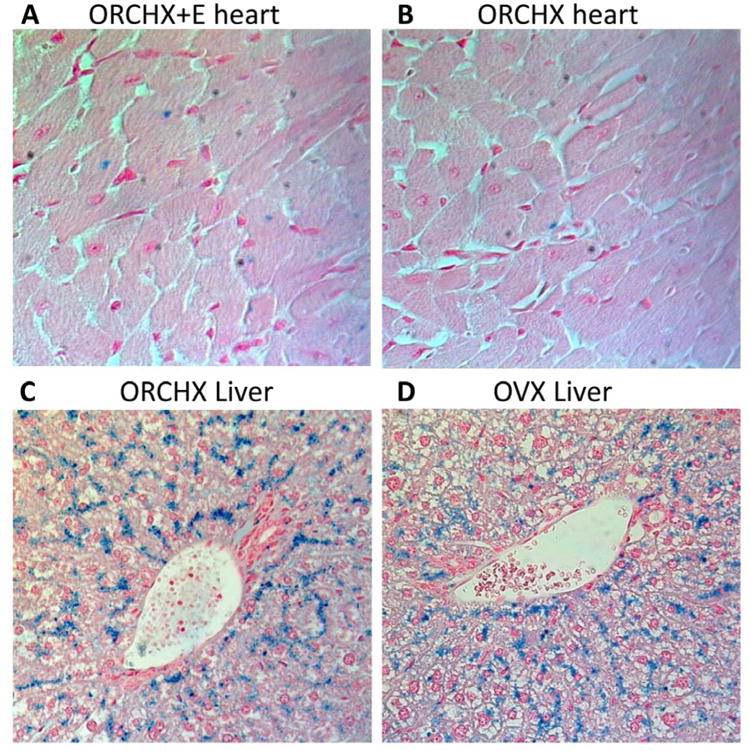

The location of iron deposits within the heart and liver was revealed via Prussian blue staining (Fig. 5). OrchX+E mice, which had the most cardiac iron as measured by atomic absorption, showed heart iron primarily within cardiomyocytes. OrchX mice had fewer cardiac iron deposits than OrchX+E mice, but also largely deposited iron within cardiomyocytes. While male mice had significantly more liver iron than female mice, the pattern of liver iron deposition was very similar in males and females. Hepatic iron deposits tended to cluster around portal triads and largely resided within hepatocytes in both males and females.

Fig 5.

Prussian blue iron staining of heart (40× magnification) and liver tissue (20× magnification). Iron deposits are revealed by their blue color. (A) OrchX+E mice show iron staining within cardiomyocytes. (B) OrchX mice also show iron staining within cardiomyocytes, but to a lesser degree. (C and D) Male and female livers showed similar patterns of iron deposits around portal triads. OrchX and OVX livers are depicted here as examples. Hepatic iron deposited largely within hepatoctyes.

Discussion

We found that estrogen increased cardiac iron concentration selectively in males, indicating that prenatal steroid exposure primed the males (organizational effect) to accumulate greater cardiac iron in the presence of estrogen (activational effect). It is true that estrogen-implanted males had a trend towards smaller heart weight (Table 1), which could conceivably increase cardiac iron through a concentration effect. However, estrogen lowered heart weights more in females than in males, yet females did not show an increase in cardiac iron concentration. There was also no correlation found between heart weight and cardiac iron concentration (data not shown). Therefore, changes in heart weight do not explain the changes in cardiac iron concentration seen in OrchX+E mice.

One way estrogen could increase cardiac iron load in males is by modulating the iron transporters of the heart. Traditional iron transporters such as DMT1 and ferroportin are tightly regulated so that stable levels of tissue iron are maintained, even during iron overload (37). More likely targets include putative, nonspecific labile iron transporters such as the Zip14 zinc channel or the L-type and T-type calcium channels (14-16). However, we did not see any effect of sex or hormone treatment on mRNA expression of these three channels, or any correlation between their expression and heart iron concentration. We did not have sufficient cardiac tissue to probe for differences at the protein level. We also cannot exclude possible hormone effects on channel activity. With regards to the L-type calcium channel, several studies suggest that estrogen inhibits its current, which would counter the observations in the present work (38-40).

Alternatively, estrogen could be increasing cardiac iron load in males by increasing the amount of labile plasma iron (LPI), the form of iron taken up by cardiac myocytes. Iron in the plasma is normally bound by transferrin so that it can be shuttled throughout the body in a safe manner. Once transferrin saturation reaches ∼85%, LPI levels rise quite sharply (41). If estrogen treatment in males increases iron levels in the plasma, and transferrin is already nearly saturated, then there would be disproportionately more LPI available for transport into the heart. Direct validation of this possibility is challenging because of the lability and lack of validation of transferrin saturation measurements in animals.

Hormone treatment did not have any significant effect on liver iron concentration in either sex (no activational effect). However, males had 25% more liver iron than females overall, indicating organizational differences in iron absorption or elimination. Further work using metabolic cages and using different controlled diets will be necessary to better localize the source of these differences. In prior published works, females have had more hepcidin expression and liver iron than males (42, 43). However, there are two key differences between the present study and prior work. First, HJV KOs have no significant hepcidin upregulation in response to iron load, thus sex differences in hepcidin expression will be masked. Second, the present study did not address the potential role of progesterone on iron absorption in females. While the OVX+E females did have physiologic levels of estrogen, they had no exposure to progesterone. Because progesterone is produced in preparation for and maintenance of pregnancy, it is conceivable that it enhances iron absorption. Alternatively, normal hormonal cyclicity of gonad-intact females could cause them to have more liver iron than males.

Initially, the translational relevance of estrogen replacement in males might be difficult to appreciate. Testosterone is the dominant steroid produced by the testes, and circulating estrogen levels in males are relatively low. Instead, males produce estrogen locally by aromatization of testosterone at target tissue sites that also contain estrogen receptors. The aromatase enzyme has been detected in various tissues of the body including adipose, bone, vasculature, brain and heart (44-46). Many studies, particularly in the central nervous system, have shown that actions of androgens in males are actually mediated via estrogen. Because testosterone has potential to bind either to androgen receptors or to estrogen receptors after local aromatization, it is important to distinguish between its androgenic and estrogenic effects. This is achieved through comparison of DHT vs. estrogen replacement. That testosterone-treated males in the present study exhibited cardiac iron levels similar to estrogen-treated males (and higher than DHT-treated males) argues that testosterone's effects in males are likely mediated through estrogen.

One limitation of this study is that we do not have measurements of LPI or transferrin saturation. These measurements are challenging to perform accurately in humans, and even more so in mice. Further work is also needed to explore whether increased liver iron resulted from increased iron absorption or decreased iron excretion. Radiolabelled iron and metabolic cage studies would be required to address this question. Small group sizes may have limited our ability to detect a significant difference in cardiac iron between the androgenic mice (OrchX+T and OrchX+DHT) and OrchX. If our measured means and standard deviations were representative of true cardiac iron differences, we would have required group sizes of 18 animals for the OrchX+DHT vs. OrchX comparison, and 12 animals for the OrchX+T vs. OrchX comparison to achieve 80% statistical power to detect these differences; group sizes of this magnitude would have been difficult to justify to our animal facility and animal use committees.

We also acknowledge that there is no perfect model for mimicing transfusional iron overload. Hypertransfusion is technically challenging and cannot produce meaningful cardiac iron loading in rodents during their lifespan (humans require close to 100 transfusions before cardiac iron accumulation occurs). Massive macromolecular iron injections produce detectable iron overload in the heart, but unlike in humans, most of the iron is deposited in cardiac macrophages rather than cardiomyocytes (25). In contrast, the HJV KO mouse, when given increased dietary iron, produces myocyte histology and iron levels similar to those found in adolescents with early cardiac iron accumulation (24). Although mutations in HFE are far more common than those in HJV, HFE knockouts do not readily load cardiac iron. In fact, humans with the HFE mutation do not develop cardiac iron overload until the fourth or fifth decade of life.

Any mutation that abolishes hepcidin response to iron inherently obscures the possibility that sex steroids may act through modulation of the BMP-SMAD and hepcidin pathways. To date, the effects of sex steroids on hepcidin have been mixed: ‘Yang Q et al. 2012’ and ‘Hou Y et al. 2012’ demonstrated that OVX females had increased hepcidin, while ‘Ikeda et al., 2012’ reported that OVX females had decreased hepcidin (47-49). While our results have important limitations, they do clearly demonstrate substantive steroid-mediated differences that are independent of hepcidin. This is also relevant because thalassemia patients tend to have low hepcidin levels due to their ineffective erythropoiesis. Furthermore, there has been no evidence to date that cardiac HJV has any effect on cardiac iron flux.

Our animal model also fails to capture functional aspects of cardiac iron overload. Histology of the HJV KOs revealed no structural damage in the heart and the activity level and life span of the mice were normal. However, creating functional abnormalities of iron overload in rodents has been very hard to capture across the field. Rodents may have a better intrinsic buffering system against iron overload within cardiomyocytes. Alternatively, the time-scale of practical animal experimentation (weeks to months) is much shorter than the time-scale for development of cardiac symptoms in humans (years), so the iron just may not have had sufficient time to produce measureable damage.

Speculations

Men fare worse than women in iron overload syndromes. Iron loss through menstruation may be one potential explanation for this effect. However, since female mice do not menstruate, menstrual blood loss cannot account for the sex differences we observed in the present study. Although hepcidin regulation and dysregulation explain many clinical aspects of iron biology, we demonstrate that sex steroids increase hepatic and cardiac iron loading through a hepcidin-independent mechanism in a primary hemochromatosis model. The effect is limited to males, indicating that prenatal steroid exposure is responsible for postnatal sensitivity. No clear evolutionary basis for this observation is evident, but there are clinical consequences. For example, it may partially explain why development of cardiac iron overload is most common between 10 and 20 years of age in secondary hemochromatosis (18). Increased iron absorption in males might also contribute to sex differences in hereditary hemochromatosis severity (21). Sex differences might also be a useful technique to probe for iron transporters and alternative regulatory pathways.

Background.

Iron cardiomyopathy remains the leading cause of death for patients with iron overload, with cardiac iron accumulation peaking during adolescence. Mortality rate is twice as great for men as it is for women, suggesting a role for sex steroids in cardiac iron accumulation and toxicity.

Translational Significance.

Estrogen increased cardiac iron through in males but not females, indicating organizational differences in steroid sensitivity. Increased cardiac iron loading in peripubertal and post-pubertal males may contribute to their poorer survival.

Acknowledgments

Partial funding for this study was provided by NHLBI grant #1RC HL099412-01 and by Novartis. Dr. John Wood consults for Shire, ApoPharma, and Novartis and has received speaker's honoraria and travel support from all three companies.

List of Abbreviations

- OVX

ovariectomized

- OrchX

castrated

- E

estrogen

- T

testosterone

- DHT

dihydrotestosterone

- HFE

hemochromatosis

- HJV

hemojuvelin

- KO

knockout

- LPI

labile plasma iron

Footnotes

The authors have no other financial or personal relationship with organizations that could potentially be perceived as influencing the described research. All authors have read the journal's policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ganz T. Hepcidin, a key regulator of iron metabolism and mediator of anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2003 Aug 1;102(3):783–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrews NC. Forging a field: the golden age of iron biology. Blood. 2008 Jul 15;112(2):219–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-077388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridle KR, Frazer DM, Wilkins SJ, et al. Disrupted hepcidin regulation in HFE-associated haemochromatosis and the liver as a regulator of body iron homoeostasis. The Lancet. 2003;361(9358):669–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12602-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Wrighting DM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling by hemojuvelin regulates hepcidin expression. Nat Genet. 2006 May;38(5):531–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babitt JL, Huang FW, Xia Y, Sidis Y, Andrews NC, Lin HY. Modulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling in vivo regulates systemic iron balance. J Clin Invest. 2007 Jul;117(7):1933–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI31342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Domenico I, Ward DM, Langelier C, et al. The molecular mechanism of hepcidin-mediated ferroportin down-regulation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007 Jul;18(7):2569–78. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan J. Mechanisms of Cellular Iron Acquisition: Another Iron in the Fire. Cell. 2002;111(5):603–6. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolondi G, Garuti C, Corradini E, et al. Altered hepatic BMP signaling pathway in human HFE hemochromatosis. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2010;45(4):308–12. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papanikolaou G, Samuels ME, Ludwig EH, et al. Mutations in HFE2 cause iron overload in chromosome 1q-linked juvenile hemochromatosis. Nat Genet. 2004;36(1):77–82. doi: 10.1038/ng1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beutler E. Hemochromatosis: Genetics and Pathophysiology. Annual Review of Medicine. 2006;57(1):331–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.121304.131310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Babitt JL, Lin HY. The Molecular Pathogenesis of Hereditary Hemochromatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2011;31(03):280–92. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1286059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porter JB. Pathophysiology of Transfusional Iron Overload: Contrasting Patterns in Thalassemia Major and Sickle Cell Disease. Hemoglobin. 2009;33(s1):S37–S45. doi: 10.3109/03630260903346627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. Thalassemia--a global public health problem. Nat Med. 1996;2(8):847–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0896-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oudit GY, Sun H, Trivieri MG, et al. L-type Ca(2+) channels provide a major pathway for iron entry into cardiomyocytes in iron-overload cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2003 Sep;9(9):1187–94. doi: 10.1038/nm920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumfu S, Chattipakorn S, Srichairatanakool S, Settakorn J, Fucharoen S, Chattipakorn N. T-type calcium channel as a portal of iron uptake into cardiomyocytes of beta-thalassemic mice. European Journal of Haematology. 2010;86(2):156–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nam H, Wang CY, Zhang L, et al. ZIP14 and DMT1 in the liver, pancreas, and heart are differentially regulated by iron deficiency and overload: implications for tissue iron uptake in iron-related disorders. Haematologica. 2013;98(7):1049–57. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.072314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weatherall D. The Thalassemias: the role of molecular genetics in an evolving global health problem. Am J Hum Genet. 2004 Mar;74(3):385–92. doi: 10.1086/381402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood JC, Origa R, Agus A, Matta G, Coates TD, Galanello R. Onset of cardiac iron loading in pediatric patients with thalassemia major. Haematologica. 2008 Jun;93(6):917–20. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood JC, Kang BP, Thompson A, et al. The effect of deferasirox on cardiac iron in thalassemia major: impact of total body iron stores. Blood. 2010 Jul 29;116(4):537–43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-250308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borgna-Pignatti C, Rugolotto S, De Stefano P, et al. Survival and complications in patients with thalassemia major treated with transfusion and deferoxamine. Haematologica. 2004 Oct;89(10):1187–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burke W, Thomson E, Khoury MJ, et al. Hereditary hemochromatosis: Gene discovery and its implications for population-based screening. JAMA. 1998;280(2):172–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phoenix CH, Goy RW, Gerall AA, Young WC. Organizing action of prenatally administered testosterone propionate on the tissues mediating mating behavior in the female guinea pig. Endocrinology. 1959;65(3):369–82. doi: 10.1210/endo-65-3-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarthy MM, Wright CL, Schwarz JM. New tricks by an old dogma: mechanisms of the Organizational/Activational Hypothesis of steroid-mediated sexual differentiation of brain and behavior. Horm Behav. 2009;55(5):655–65. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Otto-Duessel M, Brewer C, Wood JC. Interdependence of cardiac iron and calcium in a murine model of iron overload. Transl Res. 2011;157(2):92–9. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otto-Duessel M, Brewer C, Gonzalez I, Nick H, Wood JC. Safety and efficacy of combined chelation therapy with deferasirox and deferoxamine in a gerbil model of iron overload. Acta Haematol. 2008;120(2):123–8. doi: 10.1159/000174757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang FW, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS, Fleming MD, Andrews NC. A mouse model of juvenile hemochromatosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):2187–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI25049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wersinger SR, Sannen K, Villalba C, Lubahn DB, Rissman EF, De Vries GJ. Masculine sexual behavior is disrupted in male and female mice lacking a functional estrogen receptor alpha gene. Horm Behav. 1997 Dec;32(3):176–83. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antzoulatos E, Jakowec MW, Petzinger GM, Wood RI. Sex differences in motor behavior in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010 Jun;95(4):466–72. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacob DA, Temple JL, Patisaul HB, Young LJ, Rissman EF. Coumestrol antagonizes neuroendocrine actions of estrogen via the estrogen receptor alpha. Exp Biol Med. 2001;226:301–6. doi: 10.1177/153537020122600406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barkley MS, Goldman BD. The effects of castration and Silastic implants of testosterone on intermale aggression in the mouse. Horm Behav. 1977;9(1):32–48. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(77)90048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang AS, Gao J, Koeberi DD, Enns CA. The role of hepatocyte hemomjuvelin in regulation of bone morphogenic protein-6 and hepcidin expression in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2010 May;285(22):16416–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liuzzi JP, Bobo JA, Lichten LA, Samuelson DA, Cousins RJ. Responsive transporter genes within the murine intestinal-pancreatic axis form a basis of zinc homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(40):14355–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406216101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golden KL, Marsh JD, Jiang Y. Castration reduces mRNA levels for calcium regulatory proteins in rat heart. Endocrine. 2002;19(3):339–44. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:19:3:339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuta E, Miake J, Yano S, et al. Subtype switching of T-type Ca 2+ channels from Cav3. 2 to Cav3. 1 during differentiation of embryonic stem cells to cardiac cell lineage. Circ J. 2005;69(10):1284–9. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vecchi C, Montosi G, Zhang K, et al. ER stress controls iron metabolism through induction of hepcidin. Science. 2009;325(5942):877–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1176639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krijt J, Niederkofler V, Salie R, et al. Effect of phlebotomy on hepcidin expression in hemojuvelin-mutant mice. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2007;39(1):92–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muckenthaler MU, Galy B, Hentze MW. Systemic Iron Homeostasis and the Iron-Responsive Element/Iron-Regulatory Protein (IRE/IRP) Regulatory Network. Annu Rev Nutr. 2008;28(1):197–213. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.28.061807.155521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kam KW, Kravtsov GM, Liu J, Wong TM. Increased PKA activity and its influence on isoprenaline-stimulated L-type Ca2+ channels in the heart from ovariectomized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;144(7):972–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson BD, Zheng W, Korach KS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA, Rubanyi GM. Increased expression of the cardiac L-type calcium channel in estrogen receptor-deficient mice. J Gen Physiol. 1997;110(2):135–40. doi: 10.1085/jgp.110.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cairrão E, Alvarez E, Carvas JM, Santos-Silva AJ, Verde I. Non-genomic vasorelaxant effects of 17β-estradiol and progesterone in rat aorta are mediated by L-type Ca2+ current inhibition. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2012;33(5):615–24. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piga A, Longo F, Duca L, et al. High nontransferrin bound iron levels and heart disease in thalassemia major. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(1):29–33. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Courselaud B, Troadec MB, Fruchon S, et al. Strain and gender modulate hepatic hepcidin 1 and 2 mRNA expression in mice. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;32(2):283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krijt J, Cmejla R, Sýkora V, Vokurka M, Vyoral D, Necas E. Different expression pattern of hepcidin genes in the liver and pancreas of C57BL/6N and DBA/2N mice. J Hepatol. 2004;40(6):891–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson ER. Sources of estrogen and their importance. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;86(3-5):225–30. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(03)00360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bell JR, Mellor KM, Wollermann AC, et al. Aromatase Deficiency Confers Paradoxical Postischemic Cardioprotection. Endocrinology. 2011;152(12):4937–47. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grohe C, Kahlert S, Lobbert K, Vetter H. Expression of oestrogen receptor alpha and beta in rat heart: role of local oestrogen synthesis. J Endocrinol. 1998;156(2):R1–R7. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.156r001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Q, Jian J, Katz S, Abramson SB, Huang X. 17β-Estradiol inhibits iron hormone hepcidin through an estrogen responsive element half-site. Endocrinology. 2012;153(7):3170–8. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hou Y, Zhang S, Wang L, et al. Estrogen regulates iron homeostasis through governing hepatic hepcidin expression via an estrogen response element. Gene. 2012;511(2):398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikeda Y, Tajima S, Izawa-Ishizawa Y, et al. Estrogen regulates hepcidin expression via GPR30-BMP6-dependent signaling in hepatocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]