Abstract

“Hookups” are sexual encounters between partners who are not in a romantic relationship and do not expect commitment. We examined the associations between sexual hookup behavior and depression, sexual victimization (SV), and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among first-year college women. In this longitudinal study, 483 women completed 13 monthly surveys assessing oral and vaginal sex with hookup and romantic partners, depression, SV, and self-reported STIs. Participants also provided biological specimens that were tested for STIs. During the study, 50% of participants reported hookup sex, and 62% reported romantic sex. Covariates included previous levels of the outcome, alcohol use, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and romantic sex. Autoregressive cross-lagged models showed that controlling for covariates, hookup behavior during college was correlated with depression, Bs = .21, ps < .05, and SV, Bs = .19, ps < .05. Additionally, pre-college hookup behavior predicted SV early in college, B = .62, p < .05. Hookup sex, OR 1.32, p < .05, and romantic sex, OR 1.19, p < .05, were associated with STIs. Overall, sexual hookup behavior among college women was positively correlated with experiencing depression, SV, and STIs, but the nature of these associations remains unclear, and hooking up did not predict future depression.

Keywords: hooking up, casual sex, college students, sexual victimization, depression

Emerging adulthood, the life-stage between adolescence and adulthood (ages 18 to 25), is replete with important developmental tasks, including identity formation and exploration of romantic and sexual intimacy (Arnett, 2000). The first year of college marks an important developmental time, as emerging adults transition from more structured social environments (i.e., high school) to settings characterized by less parental monitoring, increased flexibility of schedules, a wider range of social opportunities, and greater access to same-age peers as well as easier access to alcohol and other drugs (Fromme, Corbin, & Kruse, 2008). The developmental tasks of emerging adulthood coupled with new freedoms and social opportunities facilitate an increase in sexual exploration.

Sexual exploration among emerging adults increasingly occurs outside of traditional courtship relationships (i.e., dating) in encounters called “hookups” (Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013). The term hookup lacks a single, universal definition, but there appears to be consensus among young people and scholars that hookups are sexual interactions that occur outside of committed romantic relationships (cf. Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013; Garcia, Reiber, Massey, & Merriweather, 2012; Heldman & Wade, 2010; Lewis, Atkins, Blayney, Dent, & Kaysen, 2012a; Paul & Hayes, 2002; Stinson, 2010). Hookups involve a wide range of sexual behaviors (e.g., kissing to vaginal sex) between partners who are not dating or in a romantic relationship, and the interaction does not imply an impending romantic commitment (Epstein, Calzo, Smiler, & Ward, 2009; Holman & Sillars, 2012; Lewis et al., 2012a; Paul & Hayes, 2002). Hookup behavior is common among college students; a recent review found that lifetime prevalence rates among college samples typically range from 60–80% (Garcia et al., 2012).

Little is known about the health consequences of hooking up. In the popular press (e.g., Stepp, 2007) and the scientific literature (e.g., Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013; Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008; Heldman & Wade, 2010; LaBrie, Hummer, Ghaidarov, Lac, & Kenney, 2012; Paul & Hayes, 2002; Testa, Hoffman, & Livingston, 2010), hookups are portrayed as harmful to young people, especially women; many authors have suggested that hookups increase women’s risk of poor mental health (e.g., depression, low self-esteem), sexual victimization, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). However, the evidential basis for these portrayals remains limited (Bersamin et al., 2013; Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013). Nomothetically, young women are more vulnerable than young men to depression (American College Health Association [ACHA], 2011), sexual victimization (Forke, Myers, Catallozzi, & Schwarz, 2008), and STIs (McCree & Rompalo, 2007). Women are also believed to be more at risk for the potential negative health outcomes of hooking up (Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013; Owen, Quirk, & Fincham, 2013). Therefore, we focused our investigation of the health consequences of hookups on women.

Sexual hookup behavior may have varied effects on women’s mental health. Hookups are described as enjoyable and convenient (Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013; Paul & Hayes, 2002), and college women report more positive emotional reactions to their hookups than negative reactions (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Owen & Fincham, 2011; Owen et al., 2013). However, in several cross-sectional studies (Bersamin et al., 2013; Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008; Grello, Welsh, & Harper, 2006; Mendle, Ferrero, Moore, & Harden, 2013; Owen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Fincham, 2010; Paul, McManus, & Hayes, 2000) and two longitudinal studies (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen, Fincham, & Moore, 2011), hooking up was associated with negative emotional states. Negative reactions may be related to attitudes about relationships and sexual behavior; for instance, compared to men, women are less likely to desire or engage in sex outside of committed relationships (Okami & Shackelford, 2001). Because of the sexual “double standard,” women who hook up too often are disparaged (Bogle, 2008; England, Shafer, & Fogarty, 2008). In one study, almost two-thirds of women reported wanting their hookup to become a romantic relationship (Owen & Fincham, 2011); they may experience emotional distress if this transition does not occur. In addition, women may not experience sexual satisfaction during hookups (Armstrong, England, & Fogarty, 2012), and they may be pressured by hookup partners to go further sexually than they want (Paul & Hayes, 2002; Wright, Norton, & Matusek, 2010).

Evidence regarding the association between hooking up and sexual victimization (SV) is more limited. One study revealed that 25% of college students with hookup experience reported unwanted sex during college, compared to 0% of students without hookup experience (Flack et al., 2007). A longitudinal study found that hookup behavior during high school and the first semester of college was a risk factor for SV during the first year of college (Testa et al., 2010). Sexual hookup behavior may increase women’s risk for SV through several mechanisms. First, alcohol use and hookup behavior frequently co-occur (LaBrie et al., 2012), and alcohol use is a risk factor for SV (Söchting, Fairbrother, & Koch, 2004). Therefore, when examining the relationship between hooking up and SV, it is important to control for alcohol use. Second, hookups may lead men to misperceive women’s sexual interest, which is another risk factor for SV (Abbey, Zawacki, Buck, Clinton, & McAuslan, 2001). Research has also shown that “hookup” can be an ambiguous term (Bogle, 2008; Lewis et al., 2012a), that men and women often differ in their expectations for how far hookups should progress (Wright et al., 2010), that men and women overestimate the other gender’s comfort with sexual behaviors during a hookup (Lambert, Kahn, & Apple, 2003), and that partners do not usually talk about what is happening (Paul & Hayes, 2002). Taken together, these factors may create risk for SV. Third, hooking up may also increase risk for SV by providing more opportunities to encounter a sexually aggressive partner (Franklin, 2010).

Evidence regarding the association between hooking up and STIs is also limited. Hooking up may increase risk for STIs due to unprotected sex and the increased likelihood of having multiple or concurrent partners compared to committed relationships (Claxton & van Dulmen, 2013; Paik, 2010). Event-level studies of college students’ most recent hookups have shown that 15–38% involved oral sex, and 27–39% involved vaginal sex (England et al., 2008; Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Lewis, Granato, Blayney, Lostutter, & Kilmer, 2012b). As is true of most oral sex encounters (ACHA, 2011), condom use is seldom reported for oral sex hookups (Fielder & Carey, 2010b). Regarding vaginal sex hookups, 69% of female students reported condom use (Fielder & Carey, 2010b). Another event-level study found that 53% of hookups involving oral, vaginal, and/or anal sex were not condom-protected (Lewis et al., 2012b). Because hookup partners are not in committed relationships, such relationships are more likely to involve brief intervals between partners or partner concurrency, factors that increase risk for STIs (Kraut-Becher & Aral, 2003).

In sum, although it is plausible to predict associations between hookups and depression, SV, and STIs among women, there is a paucity of research on these predictions. Most studies of hooking up and mental health have been cross-sectional (e.g., Bersamin et al., 2013; Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008; Mendle et al., 2013; Owen et al., 2010; Paul et al., 2000) and have not used clinically relevant measures (e.g., clinical-level depression). Only one longitudinal study has explored the link between hookups and SV (Testa et al., 2010), and no study has investigated the relationship between hookups and STI risk. Moreover, the effect of depression and SV on later hookup behavior has not been investigated. Therefore, the current study was designed to examine the effect of hooking up on depression, SV, and STIs in women.

We included several covariates in our study to rule out alternative explanations for the association between hookups and the outcomes. First, we controlled for romantic sex (i.e., sex within the context of romantic relationships) to control for general sexual activity; by doing so, we could examine the specific effects of hookup sex. Second, we controlled for alcohol use (typical drinks per week) given its correlation with depression in college women (Harrell, Slane, & Klump, 2009) and its status as a robust risk factor for SV (Söchting et al., 2004). Third, to rule out third-variable explanations related to personality, impulsivity and sensation-seeking were included in all models given their associations with sexual risk taking (Charnigo et al., 2013). Fourth, when examining SV only, we controlled for sorority membership, which has been identified as a risk factor for SV among college women (e.g., Minow & Einolf, 2009). Fifth, we controlled for demographic characteristics (i.e., race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation) given that race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (Owen et al., 2010) have been related to hooking up in prior studies. Lastly, we controlled for prior levels of each outcome to ensure that relationship between hookups and the outcomes were not better explained by prior history of the outcome (e.g., we controlled for baseline depression when predicting first-semester depression).

In summary, the purpose of our study was to assess the associations of sexual hookup behavior with depression, SV, and STIs among first-year college women. We focused on penetrative (i.e., oral or vaginal) sex during hookups given the greater degree of physical intimacy compared to non-penetrative sexual behavior (e.g., kissing, petting) as well as the potential for STI transmission. Anal sex was not a focus of this study because it is unusual during hookups (occurs in 0–3% of hookups, Fielder & Carey, 2010b; LaBrie et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012b). We sampled college students because of the prevalence of hooking up among this group (Garcia et al., 2012) and because a major developmental goal of emerging adulthood is exploration of sex and intimacy (Arnett, 2000). We sampled females because they are disproportionately vulnerable to depression (ACHA, 2011), SV (Forke et al., 2008), and STIs (McCree & Rompalo, 2007), compared to males. To improve upon prior research, we recruited a large sample and used frequent measurements and a longitudinal design. We hypothesized that engaging in hookups would increase women’s risk of experiencing (a) depression, (b) SV, and (c) STIs. We also advanced the field by examining the opposite direction of effects, that is, whether depression and SV increased women’s risk of hooking up. To determine whether hooking up poses a unique risk, sexual behavior in the context of romantic relationships was used as a basis of comparison, and to rule out third variable explanations, we controlled for other empirically and theoretically relevant variables, as noted above.

Method

Participants

Participants were 483 first-year female undergraduates attending a private university in upstate New York. Exclusion criteria were: under age 18 or over age 25 at baseline (women younger than 18 were excluded due to logistical difficulties associated with obtaining parental consent, women older than 25 were excluded due to our focus on emerging adults) and scholarship athlete (excluded due to National Collegiate Athletic Association restrictions on receiving payments while a student-athlete). The sample constituted 26% of the incoming first-year female students at the university for the Fall 2009 semester and had an equivalent racial/ethnic distribution to the entire class of first-year females (Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, 2011). Of the women who enrolled in the study,94% were 18 years old at baseline (M = 18.1, SD = 0.3, range: 18–21). Two-thirds (66%) identified as White, 11% as Asian, 10% as Black, and 13% as other/multiple races; 9% identified as Hispanic. Almost all participants (96%) identified as heterosexual, and 23% reported joining a sorority in February 2010. On average, participants reported middle to upper-middle class socioeconomic status (M = 6.3, SD = 1.7, median = 6.0, range: 1–10).

Design

We used a longitudinal design with a baseline (T1) and 12 monthly follow-ups (T2-T13).

Measures

Demographics

At baseline, participants provided their age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation (heterosexual, gay/lesbian, bisexual, unsure; ACHA, 2011), and relationship status (single, committed relationship). At T8, participants indicated their family’s socioeconomic status using a 10-point ladder, on which they ranked their family relative to other American families (scale of 1 to 10; Adler, Epel, Castellazzo, & Ickovics, 2000).

Covariates

To capture alcohol use at each assessment, participants completed a grid assessing the number of standard drinks consumed each day in a typical week in the last month (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985); this yielded typical drinks per week.

Impulsivity was measured at baseline using six items (Magid, MacLean, & Colder, 2007) from the impulsiveness subscale of the Impulsiveness—Monotony Avoidance Scale (Schalling, 1978). Participants indicated how well each item (e.g., “I often throw myself too hastily into things”) applied to them on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me). Scores were summed to create a total score (α = .82) ranging from 6 to 24.

Sensation-seeking was measured at baseline using six items (Magid et al., 2007) from the monotony avoidance subscale of the Impulsiveness—Monotony Avoidance Scale (Schalling, 1978). Participants indicated how well each item (e.g., “I like doing things just for the thrill of it”) applied to them on a Likert scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me). Scores were summed to create a total score (α = .82) ranging from 6 to 24.

At T7, participants indicated whether they had joined a sorority during the Spring 2010 semester. Wave seven was the first survey after sorority rush was completed.

Sexual behavior

Participants were first asked about physical intimacy (“closeness with a partner that might include kissing, sexual touching, or any type of sexual behavior”) separately for romantic and casual partners to orient them to our definitions of partner types and to inform skip patterns. A romantic partner was defined as “someone whom you were dating or in a romantic relationship with at the time of the physical intimacy.” A casual partner was defined as “someone whom you were not dating or in a romantic relationship with at the time of the physical intimacy, and there was no mutual expectation of a romantic commitment. Some people call these hookups.” This definition of casual/hookup partner has been used in prior research (Fielder & Carey, 2010a, 2010b; Lewis et al., 2012a, 2012b). Participants who indicated one or more partners or who left the number of physical intimacy partners questions blank proceeded to questions about oral and vaginal sex. Oral sex was defined as “when either partner puts their mouth on the other partner’s genitals,” and vaginal sex was defined as “when a man puts his penis in a woman’s vagina.”

Hookup behavior was assessed at every occasion using items adapted from previous research (Fielder & Carey, 2010a, 2010b). Rather than asking participants directly about hookups (e.g., with how many people have you hooked up?), participants were asked about engaging in specific sexual behaviors (i.e., oral and vaginal sex) with casual partners (Fielder, Carey, & Carey, 2013). Use of the word hookup was intentionally minimized (i.e., only used once, within the definition of casual partner as stated earlier) due to the potential for proactive interference, which may have caused participants to respond with idiosyncratic understandings of the term in mind (Bogle, 2008; LaBrie et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012a; Paul & Hayes, 2002). A sexual hookup was operationally defined as oral or vaginal sex with a casual partner; this definition reflects the extant research on partner types, sexual behaviors, and the defining characteristic of a hookup (Epstein et al., 2009; Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Garcia et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012a; Paul & Hayes, 2002). This assessment strategy reduced ambiguity in interpretations of questions about hookups.

Three items assessed the number of oral sex (performed), oral sex (received), and vaginal sex with casual partners (i.e., hookup events) within a given time interval. A parallel set of three items assessed sexual behavior in the context of romantic relationships, henceforth referred to as romantic behavior. At baseline (T1), participants were asked about their lifetime; at subsequent monthly assessments (T2-T13), participants were asked about the last month, and anchor dates were provided to facilitate recall.

Depression

Depression was measured at every assessment using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Spitzer, Kroenke, & Williams, 1999), which has high test-retest reliability, good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α .81–.89 in this study) and demonstrated construct and criterion validity (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). Participants indicated how often they were bothered by each symptom (e.g., little interest or pleasure in doing things) over the last two weeks on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The PHQ-9 scoring algorithm (Spitzer et al., 1999) identifies the presence (yes/no) of clinically significant depressive symptoms that meet diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Dichotomous variables were created to capture depression at baseline, between T2 and T5, between T6 and T9, and between T10 and T13. Findings related to depression and hooking up may differ based on use of a continuous versus dichotomous outcome (see Mendle et al., 2013). With regard to the data reported in the present study, the pattern of findings was similar using a continuous indicator of depressive symptom severity, but we present the findings using the dichotomous indicator of depression (viz., clinical-level depression) because the latter is more clinically interpretable.

Sexual victimization

SV was assessed every four months using items adapted (by Testa et al., 2010) from the Revised Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss et al., 2007). The measure comprised 20 items, formed by crossing four perpetrator tactics with five types of sexual contact, and asked women to indicate how many times (0, 1, 2, 3, or 4+) each experience happened “when you indicated that you didn’t want to.” Participants reported SV since age 14 at baseline, and SV during the Fall semester (i.e., August–December) at T5; during the Spring semester (i.e., January–April) at T9; and over the summer (i.e., May–August) at T13. Due to limited variability in the frequency of SV, which precluded use of count regression analyses, we created dichotomous variables indicating whether participants experienced one or more incidents of SV before entering college, between T2 and T5, between T6 and T9, and between T10 and T13.

In the current study, we limited our focus to 12 items consistent with our operational definition of SV: oral sex, anal sex or other penetration, attempted vaginal intercourse, or completed vaginal intercourse that occurred via physical force, threats of harm, or incapacitation (Cronbach’s α was .78 at baseline and .90–.96 at follow-ups). We focused on the most severe forms of SV that reflect legal definitions of rape (U. S. Department of Justice, 2012). Compared to a broader definition of SV (i.e., one including kissing or sexual touching by any tactic, and any sexual contact by verbal coercion), this narrower definition of SV was used because (a) unlike sexual contact, kissing and fondling do not confer risk for STIs and pregnancy; (b) women report more emotional consequences and more severe psychological effects following attempted or completed rape compared to sexual contact (Crown & Roberts, 2007), and (c) forcible and incapacitated rape are perceived by women as more severe than verbal coercion is (Abbey, BeShears, Clinton-Sherrod, & McAuslan, 2004; Brown, Testa, & Messman-Moore, 2009). The decision not to include unwanted sexual contact and verbal coercion in the operational definition of SV does not reflect a belief that unwanted sexual contact or verbally coerced SV is in any way acceptable or inconsequential; rather, it reflects our focus on the most severe outcomes at this initial stage of research.

Sexually transmitted infections

Self-reported STI diagnosis was assessed every four months. Participants were asked if they had been tested for an STI (in their lifetime at baseline and since the last assessment at T5, T9, and T13 [anchor dates were provided]); if so, they were asked if they had been diagnosed with an STI. Our analysis included only those women who reported being tested over the course of the study (at T5, T9, and/or T13). For the STI outcome, participants were classified as having a new STI based on either a self-reported diagnosis at any of the three follow-ups or a laboratory-confirmed diagnosis at T9.

STIs were assessed by biological testing at the end of the academic year (i.e., T9, April 2010). Specimens were tested for three STIs: Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Gc), and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV), which are prevalent among Americans aged 15–24 (Weinstock, Berman, & Cates, 2004). All three STIs can be detected accurately using a single self-collected vaginal swab (Caliendo et al., 2005). Testing was conducted at Emory University’s Center for AIDS Research. CT and Gc testing used the Becton Dickinson ProbeTec ET amplified DNA assay, and TV testing used Taq-Man polymerase chain reaction (Caliendo et al., 2005). Sensitivity and specificity of the three assays was 92.0% and 96.6% for CT, 95.2% and 98.8% for Gc, and 100% and 99.6% for TV, respectively.

Specimens were obtained using self-collected vaginal swabs, as recommended by the National Institutes of Health (Hobbs et al., 2008). Vaginal swabs have numerous logistical advantages over urine samples and are more sensitive than urine samples in the detection of CT and Gc, and as sensitive as endocervical swabs (Hobbs et al., 2008). Furthermore, because TV primarily affects the vagina, rather than the cervix, vaginal swabs are optimal for its detection.

Procedure

The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Recruitment

Recruitment began one month before the start of the Fall 2009 semester with a mass postal mailing to 1,400 incoming first-year female students who would be at least 18 years old by the start of the study. International students and scholarship athletes were excluded from the mailing due to uncertain timing of mail delivery to foreign addresses and ineligibility, respectively. The mailing comprised a letter introducing our study of health behaviors and relationships and directing interested women to the study website; women who signed up on the website were emailed instructions for scheduling an orientation session to learn more. Three supplemental recruitment strategies were also used to try to reach our desired sample size of 500: campus flyers, word of mouth, and the psychology department participant pool.

Data collection

During their first three weeks on campus, interested students attended a brief orientation session, at which time the study was explained and participants provided written informed consent. Participants completed the baseline survey on private individual computers, for which they received $20. All data were collected online using a secure survey website. Follow-up surveys began at the end of September 2009 (T2) and continued through the end of August 2010 (T13). Surveys were linked over time using unique identification codes, and identifying information was stored separately from survey responses. At the end of each month, participants were emailed an embedded link to a confidential survey site, and they had one week to complete the survey. Participants received $10 for each survey completed from T2-T11, $15 for T12, and $20 for T13; the increase in compensation for the final two surveys helped guard against higher attrition during the summer. Surveys were designed to be completed in 10–20 minutes. To prompt timely responding, participants were entered in a monthly raffle for two $50 cash prizes, with the number of raffle entries decreasing as response lag increased.

STI testing

Participants were invited to provide a specimen for STI testing at the end of the academic year. Participants were informed they could opt out of testing and still continue with monthly surveys. Testing occurred at the on-campus student health center. Research staff explained the procedures and obtained a separate written informed consent. To protect participants’ privacy, specimens were labeled with their identification code rather than their name. Participants were given detailed, illustrated instructions for the specimen collection and used a private bathroom to self-collect their specimen. Participants received $20 for providing a specimen. Participants with positive test results were called with the results, encouraged to visit the student health center, and advised of the procedure for obtaining free treatment. Positive test results for CT or Gc were reported to the county health department per state law.

Data Management and Analyses

Missing data

Over the one-year duration of the study and 13 assessments, 4–19% of participants had missing data on the monthly hookup and romantic sex variables.1 For the outcomes, rates of missing data (by wave/assessment) ranged from 3–19% for depression, 9–15% for SV, and 9–15% for STI diagnosis. To maintain the entire sample, we used multiple imputation, which is preferred over traditional approaches (e.g., listwise deletion) to missing data analysis (Graham, Olchowski, & Gilreath, 2007). We imputed data for missing demographics, predictors, covariates, and outcomes. For demographics and covariates, rates of missing data were 0.6% for sexual orientation, 12% for socioeconomic status, 8% for sorority membership, 0.2% for pre-college STI diagnosis, and 3–20% for typical drinks per week. We imputed 100 complete datasets (Graham et al., 2007) using the R program Amelia II (Honaker, King, & Blackwell, 2011). Analyses were conducted with all 100 datasets, and parameter estimates were pooled using the imputation algorithms in Mplus 5 (Muthén & Muthén, 2007).

Data management

Summary dichotomous variables for any hookup (romantic) behavior (performed oral sex, received oral sex, or had vaginal sex) were created for each time period by collapsing across these three types of hookup (romantic) behavior; dichotomous variables were used given low variability in monthly frequency and our preference to maintain the entire sample (it is not possible to impute count data in Mplus). For the depression and SV models, composite indicators were created for T2-T5, T6-T9, and T10-T13. We used 4-month periods to (a) align with the assessment frequency of SV, (b) assure consistency in the modeling across these two outcomes, and (c) accommodate the high degree of correlation among depression scores from adjacent months. To keep sexual behavior consistent with the depression and SV outcomes, we created dichotomous variables indicating whether any penetrative sex hookups (romantic events) occurred during each time period (i.e., T2-T5, T6-T9, and T10-T13). For the STI model, there were not enough STI cases to examine within 4-month epochs (i.e., a low base rate), so we created a variable that encompassed the entire 12-month follow-up period. Monthly indicators were summed to obtain the number of months in which the participant engaged in sexual hookup (romantic) behavior between T2 and T13.

Data analyses

Depression and SV analyses were conducted using an autoregressive cross-lagged panel model approach (Curran, 2000), allowing us to test associations within and across time. Cross-lagged path analysis is often used to infer causal associations in data from longitudinal research designs; cross-lagged models simultaneously address reciprocal influences between two or more constructs. These analyses were conducted with Mplus 5 using a robust weighted least squares estimator for categorical variables (WLSMV). We applied equality constraints in cross-lagged models to impose stationarity (cf. Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, 2010); autoregressive paths (paths from a given variable at one time point to the same variable at the next time point), lagged paths (paths from a given variable at one time point to a different variable at the next time point), and within-time correlations between variables were constrained to be equal over time. Exceptions were paths and correlations including T1 variables; these were freely estimated given that T1 variables sometimes assessed different time frames (i.e., hookup and romantic behavior, SV) and that we did not model the predecessors of T1.

The primary variables of interest (hookup behavior, depression, and SV) were modeled over time. Several covariates were included in the models to rule out alternative explanations for the association between hookups and the outcomes. Romantic sex and alcohol use (typical drinks per week) were included in all models as time-varying covariates (measured at each time point). Demographic characteristics (race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sexual orientation) as well as personality variables (impulsivity and sensation-seeking) were treated as covariates predicting the first two time points (T1 and T2-T5) of hookup behavior, depression, and SV, under the assumption that any subsequent influence of these variables operates through their associations with these early time points. Sorority membership was also included as a control in the SV model; because women could not join a sorority until their second semester, this control predicted the last two time points (T6-T9 and T10-T13) in the SV model. Paths that were highly non-significant (Z < 1) were constrained to zero to increase model parsimony and stabilize estimates (Bentler & Mooijaart, 1989).

Model fit was assessed using the comparative fit index (CFI); the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI); and the misfit measure known as the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). Good fit is indicated by CFI and TLI values greater than .95 and RMSEA values less than .05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Chi-square goodness of fit statistics were not available due to the use of multiple imputation. Fit indices were averaged across the 100 imputed datasets. We report probit regression coefficients (B) as well as 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Logistic regression was used to test the association between hookup behavior and incident STIs controlling for demographics, personality, typical drinks per week, pre-college STI diagnosis, and romantic behavior. Again, coefficients that were highly non-significant were fixed to zero (Bentler & Mooijaart, 1989). Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs are reported.

Results

Women were recruited through the mass mailing (61%), the psychology department research pool (28%), or word of mouth/flyers (11%). Response rates for the follow-up surveys ranged from 97% (at T2) to 81% (at T11). Response rates remained above 90% through T7 and were lowest during the summer (81% at T11, 83% at T12), when students did not reside on campus. The median and mode for number of surveys completed was 13 (M = 11.7, SD = 2.5); 64% completed all 13 surveys. Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for all covariates, sexual behavior variables, and outcome variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Variable | Time frame | M (SD) or % (n) | Rangea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sorority membership | T7 | 23% (111) | |

| Typical drinks per week | T1-T13 | 5.75 (5.63) | 0–29 |

| Impulsivity | Baseline | 12.67 (4.02) | 6–24 |

| Sensation-seeking | Baseline | 17.17 (3.78) | 6–24 |

| Hookup behavior | Pre-college | 34% (164) | |

| Hookup behavior | T2-T13 | 50% (241) | |

| Hookup behavior (number of months) | T2-T13 | 1.7 (2.5) | 0–11 |

| Romantic behavior | Pre-college | 58% (282) | |

| Romantic behavior | T2-T13 | 62% (300) | |

| Romantic behavior (number of months) | T2-T13 | 4.0 (4.4) | 0–12 |

| Depression | Baseline | 6.4% (31) | |

| T2-T5 | 22% (106) | ||

| T6-T9 | 23% (111) | ||

| T10-T13 | 20% (97) | ||

| Sexual victimization | Baseline | 25% (121) | |

| T2-T5 | 14% (67) | ||

| T6-T9 | 11% (52) | ||

| T10-T13 | 10% (47) | ||

| Sexually transmitted infections | Baseline | 2.1% (10) | |

| T2-T13 | 3.0% (10)b |

Ranges presented for continuous variables only.

Includes only the 334 women who reported having been tested for STIs in their lifetime.

Sexual Behavior during Hookups and Romantic Relationships

Overall, 34% of participants (n = 164) reported that they had engaged in hookup behavior (i.e., performed oral sex, received oral sex, or had vaginal sex with a casual partner) prior to starting college. Monthly rates of hookup behavior ranged from 9% (T11) to 18% (T3 and T10); overall, 50% (n = 241) reported that they engaged in hookup behavior during the study (T2-T13). The average number of months with hookup behavior was 1.7 (SD = 2.5, range: 0–11). By the end of the study, 57% (n = 277) reported engaging in an oral or vaginal sex hookup during their lifetime. For every month from T2-T13 except one (when the rates were equivalent), the prevalence of performing oral sex was 1–5% higher than the prevalence of receiving oral sex (data not shown).

Overall, 58% of participants (n = 282) reported that they had engaged in romantic behavior (i.e., performed oral sex, received oral sex, or had vaginal sex with a romantic partner) prior to starting college. At baseline, 29% reported being in a committed relationship. Monthly rates of romantic behavior ranged from 26% (T3) to 39% (T13); overall, 62% (n = 300) reported that they engaged in romantic behavior during the study. The average number of months with romantic behavior was 4.0 (SD = 4.4, range: 0–12). By the end of the study, 72% (n = 347) reported engaging in oral or vaginal sex within the context of a romantic relationship during their lifetime.

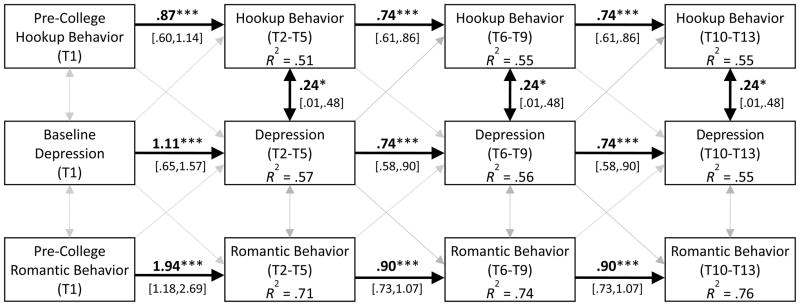

Depression

The cross-lagged model (Figure 1) was a good fit to the data, CFI = .99 (.004), TLI = .99 (.004), RMSEA = .02 (.006). At baseline, 6.4% of women reported clinically significant depressive symptoms (i.e., depression). During the study, 22% of women (n = 106) reported depression between T2 and T5, 23% (n = 111) between T6 and T9, and 20% (n = 97) between T10 and T13. The autoregressive coefficients for depression were significant, Bs ≥ 0.74, SEs ≤ 0.24, ps < .001, as were the autoregressive coefficients for hookup behavior, Bs ≥ 0.74, SEs ≤ 0.14, ps < .001, and romantic behavior, Bs ≥ 0.90, SEs ≤ 0.39, ps < .001. Neither hookup nor romantic behavior exhibited significant lagged effects on depression, nor did depression exhibit significant lagged effects on hookup or romantic behavior. However, hookup behavior in each time period during college was significantly correlated with depression, Bs = 0.24, SEs = 0.12, ps < .05. In contrast, there were no within-time associations between romantic behavior and depression.

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged model showing associations between hookup behavior, romantic behavior, and depression during the first year of college. Control variables included race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and typical drinks per week. Models were fitted using a WLSMV estimator in Mplus; unstandardized probit regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals are reported. Gray arrows represent non-significant paths included in the initial model. Average fit indices (with SEs in parentheses): CFI = .99 (.004), TLI = .99 (.004), RMSEA = .02 (.006).

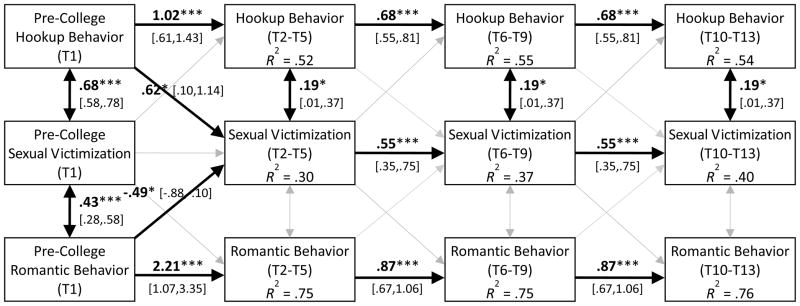

Sexual Victimization

The cross-lagged model (Figure 2) was a good fit to the data, CFI = .99 (.004), TLI = .99 (.004), RMSEA = .02 (.006). At baseline, 25% of participants reported at least one SV experience since age 14. During the study, 14% of women (n = 67) reported at least one SV event between T2 and T5, 11% (n = 52) between T6 and T9, and 10% (n = 47) between T10 and T13. Overall, 24% of women reported at least one SV event during the first year of college. The autoregressive coefficients for SV during college were significant, Bs ≥ 0.55, SEs ≤ 0.10, ps < .001, although SV early in college (T2-T5) was not predicted by pre-college SV, B = 0.19, SE = 0.19, p = .33. The autoregressive coefficients for hookup behavior were significant, Bs ≥ 0.68, SEs ≤ 0.21, ps < .001, as were those for romantic behavior, Bs ≥ .87, SEs ≤ 0.58, ps < .001. Pre-college SV was positively correlated with pre-college hookup behavior, B = 0.68, SE = 0.05, p < .001, and pre-college romantic behavior, B = 0.43, SE = 0.08, p < .001. Additionally, hookup behavior in each time period during college was significantly correlated with SV, Bs = 0.19, SEs = 0.09, ps < .05. In contrast, there were no within-time associations between romantic behavior and SV during college. Pre-college hookup behavior had a significant, positive lagged effect on T5 SV, B = 0.62, SE = 0.27, p < .05, while pre-college romantic behavior had a significant negative (protective) lagged effect on T5 SV, B = −0.49, SE = 0.20, p < .05. There were no other lagged effects of hookup or romantic behavior on SV or of SV on hookup or romantic behavior.

Figure 2.

Cross-lagged model showing associations between hookup behavior, romantic behavior, and sexual victimization during the first year of college. Control variables included race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, sorority membership, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and typical drinks per week. Models were fitted using a WLSMV estimator in Mplus; unstandardized probit regression coefficients and 95% confidence intervals are reported. Gray arrows represent non-significant paths included in the initial model. Average fit indices (with SEs in parentheses): CFI = .96 (.005), TLI = .97 (.004), RMSEA = .04 (.003).

Sexually transmitted infections

Pre-college STIs were reported by 10 participants (2.1%). The majority of the sample (n = 310, 64%) participated in STI testing as a part of the study, and a total of 334 women (69%) self-reported testing at some point during the study and were included in this analysis. Three participants had a new, biologically-confirmed STI, and seven others self-reported an incident STI during the study. In total, 3.0% of those tested (n = 10) had an incident STI during the study. Controlling for race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, drinks per week, and romantic behavior (see Table 2), hookup behavior (number of months) predicted incident STIs during the study, OR 1.32, 95% CI [1.03, 1.69], p < .05. Romantic behavior also predicted incident STIs, OR 1.19, 95% CI [1.03, 1.37], p < .05.

Table 2.

Multivariate Predictors of Incident STI Diagnosis for Women Reporting STI Testing

| Predictor | B | SE | p | AOR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asian racea | 1.65 | 0.90 | .07 | 5.19 | [0.89,31.23] |

| Black racea | 2.09 | 0.79 | .01 | 8.09 | [1.73,37.76] |

| Hispanic ethnicitya | −11.54 | 0.63 | <.001 | 0.00 | [0.00,0.00] |

| Sexual minority identificationa | −11.54 | 0.72 | <.001 | 0.00 | [0.00,0.00] |

| Socioeconomic status | −0.31 | 0.16 | .05 | 0.73 | [0.54,0.996] |

| Romantic behavior | 0.18 | 0.07 | .01 | 1.19 | [1.03,1.37] |

| Hookup behavior | 0.28 | 0.13 | .03 | 1.32 | [1.03,1.69] |

|

| |||||

| R2 | 0.85 | 0.01 | <.001 | [0.83,0.88] | |

Note. N = 334. B = regression estimate; SE = standard error; AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; STI = sexually transmitted infection. Hookup and romantic behavior includes performing oral sex, receiving oral sex, or having vaginal sex with casual and romantic partners, respectively. Pre-college STI diagnosis, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and drinks per week were included in the model, but their coefficients were fixed to zero because they were highly non-significant (Z < 1) and fixing these coefficients improved the model as measured by the Bayesian information criterion (BIC).

Dummy-coded: 0 = no, 1 = yes.

Discussion

This longitudinal study examined associations between sexual hookup behavior and depression, SV, and STIs. In this sample of 483 college women, oral or vaginal sex hookup behavior was reported by 34% prior to college and 50% during the first year of college. By the start of their sophomore year, 57% had lifetime sexual hookup experience, whereas 72% had lifetime sexual romantic experience. Rates of hookup behavior in the current study were somewhat lower than reported in some previous studies (e.g., Armstrong et al. 2012), likely reflecting two methodological differences; (a) we focused on penetrative sex hookups, which are less common than hookups involving only kissing or sexual touching (Fielder & Carey, 2010b), and (b) we sampled only first-year students rather than students from all four years.

Depression

Consistent with our first hypothesis, hookup behavior during college was positively correlated with experiencing clinically significant depression symptoms. Sex in the context of romantic relationships was not correlated with depression. There are several reasons why hooking up, but not romantic sex, may be associated with poor mental health among women, including unfavorable attitudes toward sex outside of committed relationships (Okami & Shackelford, 2001), risk of acquiring a negative reputation (England et al., 2008), failure for the hookup to transition to a romantic relationship (Owen & Fincham, 2011), sexually unsatisfying hookups (Armstrong et al., 2012), and peer pressure or verbal coercion from partners to go further sexually than they want (Paul & Hayes, 2002; Wright et al., 2010). Although some of these issues may also arise within romantic relationships (e.g., verbal coercion for sex [Brousseau, Bergeron, Hébert, & McDuff, 2011]), most do not apply or occur less commonly in romantic relationships compared to hookups (e.g., unsatisfying sex [Armstrong et al., 2012]). Indeed, dating relationships are perceived to involve more trust, intimacy, and social support compared to hookups (Bradshaw, Kahn, & Saville, 2010), and they still appear to provide a more socially acceptable context for women’s sexual behavior compared to hookups. Although we found no correlation between depression and romantic sex, prior research has found that being in a romantic relationship is negatively correlated with depression and poor mental health (i.e., romantic relationships are actually protective) among young adults, especially women (Braithwaite, Delevi, & Fincham, 2010; Simon & Barrett, 2010).

Our results showing a positive correlation between hookup behavior and depression corroborate prior findings suggesting an association between hookup behavior and poor mental health (Bersamin et al., 2013; Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Grello et al., 2006; Owen et al., 2010) with a larger sample and a clinically significant outcome (i.e., symptoms consistent with a major depressive episode). However, in contrast to prior (correlational) findings and our a priori hypotheses, hookup behavior did not predict future depression. In light of the methodological limitations of prior research and the results of the current study, there does not appear to be evidence of a causal relationship between hooking up and depression among women. This conclusion is tentative; further methodologically strong research into the association between hookup behavior and poor mental health is warranted.

The previously reported association between hookups and poor mental health (e.g., Bersamin et al., 2013; Grello et al., 2006; Owen et al., 2010) has several conceivable explanations. First, it is possible that depression predicts hookups; that is, depressed individuals may hook up as a way of coping with negative affect (Bancroft et al., 2003). The cross-lagged panel analysis allowed us to test this alternative hypothesis in our sample, and depression did not predict future hookup behavior. Second, it is possible that a “third” variable affects both depression and propensity to hook up. For instance, women who are lonely (see Owen et al., 2011) or bored may become depressed and turn to hookups to forge connections with others or interject some excitement into their lives, respectively. Another likely third variable is alcohol use, a highly prevalent behavior among first-year college students that is associated with depression among women (e.g., Harrell et al., 2009) as well as hooking up (Lewis et al., 2012b; LaBrie et al., 2012). However, in our sample, we controlled for typical level of alcohol use, and the cross-sectional association between depression and hookups persisted.

The absence of longitudinal associations between hookups and depression in our study may also reflect a methodological issue. Due to our monthly assessment schedule, the time lag between the occurrence of hookups and the measurement of depressive symptoms could have been as long as one month. It may be that emotional distress resulting from a negative hookup experience would emerge sooner after a hookup (i.e., within a matter of days), rather than several weeks or a month later. Research using more frequent experience sampling (e.g., daily diaries, ecological momentary assessment) can help to clarify the temporal relationship between hookup behavior and emotional well-being, and begin to identify moderators and mediators of the association. Overall, the present findings, coupled with prior research, suggest that hooking up is associated with poor mental health, but continued study is needed to determine if this effect is reliable and, if it is, the magnitude of the effect.

Sexual Victimization

Approximately one-quarter of the sample reported at least one instance of SV by way of physical force, threats of harm, or incapacitation during the year-long study. The rate of SV found in our sample was slightly higher than that in a prior sample using the same measure (Testa et al., 2010), but we measured SV over a longer time period. The results, which suggested that hookup behavior increases risk for SV, supported our second hypothesis and corroborated prior findings (Testa et al., 2010). Pre-college hookup behavior predicted increased likelihood of experiencing SV during the first semester of college. Additional research is needed to better understand the mechanism of this effect. In our sample, women with pre-college hookup experience were more likely to hookup early in college. However, relative to pre-college hookups, hookups in college may be occurring in physical and social environments that are riskier. For example, the college environment is likely to involve more unsupervised dorm rooms, parties, access to alcohol and other drugs, increased partner expectations for intimacy, and other factors that may increase the risk of a hookup leading to SV.

Hookup behavior during college was positively correlated with SV within each time period. This association held even after controlling for theoretically and empirically established covariates, including previous history of SV, alcohol use, impulsivity, sensation-seeking, and sorority membership. Notably, hookup behavior during college did not predict future SV, and SV during college did not predict future hookup behavior. In contrast to the pattern found with hookup sex, pre-college romantic sex predicted reduced likelihood of experiencing SV during the first semester of college, and romantic behavior during college was not associated with SV within any time period. Thus, unlike sex in the context of romantic relationships, hookup sex appears to be uniquely associated with SV. The results corroborate results from cross-sectional studies of hooking up and SV (Flack et al., 2007; Flack et al., 2008) as well as the only longitudinal study conducted thus far (Testa et al., 2010). Taken together, there is emerging support for an association between hooking up and SV, including SV that meets legal definitions of rape. Nevertheless, as with depression, we failed to find a consistent longitudinal association between hooking up and SV.

Research employing event-level methodologies can help elucidate the association between hookups and SV. For example, an important initial step for future research is to explore how often hookup events involve SV experiences. In addition, event-level studies may identify third variables, such as alcohol use (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; LaBrie et al., 2012; Lewis et al., 2012b), that increase risk for SV in the context of hookups. In the current study, the association between hookup behavior and SV existed even after controlling for the participant’s overall level of alcohol use, but it is possible that alcohol use at the time of the hookup (or partner alcohol use) may explain the hookup-SV association. Other variables, such as the ambiguity of the hookup situation (Bogle, 2008; Lewis et al., 2012a), gender differences in sexual expectations (Wright et al., 2010), lack of communication (Paul & Hayes, 2002), and the tendency for men to overestimate women’s comfort with sexual behavior during hookups (Lambert et al., 2003) likely create risk for SV and warrant event-level investigation. Also to be evaluated is the more parsimonious explanation that increased exposure to more partners creates more opportunities to encounter a sexually aggressive partner (Franklin, 2010). Clarification of the determinants of the association between hooking up and SV can help to guide prevention efforts.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

The low base rate of STIs in our sample (3%), which is consistent with the rates found in a large national sample of college students (i.e., 2%; cf. ACHA, 2011) may indicate that this sample of mostly middle to upper-middle class college students at a private university is part of a relatively low-risk sexual network. Nonetheless, hookup behavior during the study was a significant predictor of incident STIs, supporting our third hypothesis. Although the finding needs to be replicated, this is the first study to establish an association specifically between sexual hookup behavior and STI risk. Hookup behavior may increase risk for STIs in a number of ways, including opportunities for sexual risk behavior, inconsistent condom use during vaginal sex hookups (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Lewis et al., 2012b), near-zero rates of condom use during oral sex hookups (Fielder & Carey, 2010b), multiple and/or concurrent partners (Paik, 2010), and briefer gaps between partners (Kraut-Becher & Aral, 2003). Condoms may not be used for many reasons, such as the spontaneous nature of the hookup (Fielder & Carey, 2010b), lack of knowledge about STI risk, intoxication, use of hormonal contraceptives to prevent pregnancy, and low perceived risk (Civic, 2000). The potential for multiple and/or concurrent partners is higher in a hookup situation (Paik, 2010) compared to a romantic relationship, although infidelity is possible in the latter case. Romantic behavior was also an independent predictor of incident STIs. Similar to hookups, failure to use condoms correctly and consistently and serial monogamy may contribute to the risk for STIs with romantic behavior (Kraut-Becher & Aral, 2003; McCree & Rompalo, 2007).

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

First, generalizability of these results may be limited given that the sample included first-year women from only one university, and most participants were middle to upper-middle class. However, the racial distribution of the sample was equivalent to that of all incoming first-year female students at the university (Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, 2011) and that of a National College Health Assessment sample (ACHA, 2011). Second, depression scores were based on self-report, rather than structured diagnostic interviews. Nonetheless, the PHQ-9 has excellent criterion validity with depression diagnoses made by mental health professionals (Kroenke et al., 2001; Spitzer et al., 1999). Third, given limited variability in number of SV events, we used a dichotomous indicator instead of a count. Fourth, although we did offer biological testing at T9, we also included self-reported STI diagnoses for the STI outcome. Fifth, as with all studies of sexual behavior, our measures relied on self-report. Despite these limitations, confidence in the results is bolstered by the conceptual and methodological strengths of our study, including the longitudinal design, sample size, high retention rates, mental health measure with clinical significance, sophisticated data analytic approach, statistical controls for relevant third variables and romantic sex, and biological STI testing.

The limitations of this study suggest directions for future research. For example, research sampling males and non-college-attending emerging adults is needed. Weekly or daily diaries would be more sensitive to acute changes in mental health (see O’Grady, Tennen, & Armeli, 2010), allow for precise temporal ordering of hookups and emotional distress, and improve the accuracy of data collection (Leigh et al., 2008). Use of more specific sexual behavior measures, including number of partners and condom use, and event-level assessments that ask about hookup and romantic events as well as whether SV occurred specifically during those events is recommended, as is testing for additional STIs. Researchers may also want to explore whether less intimate hookups (i.e., those that do not progress farther than kissing or petting) are associated with adverse health outcomes. Finally, qualitative research might examine for whom and under what conditions hooking up may have positive outcomes (see Owen et al., 2013). Qualitative research suggests that this practice has some benefits for women (Paul & Hayes, 2002). Better understanding of its positive consequences will elucidate the full context in which youth choose to hook up.

Implications

Although hooking up may provide some emerging adults with opportunities for normative sexual exploration (Owen et al., 2013; Stinson, 2010), for others, sexual hookup behavior appears to be associated with experiencing clinically significant depressive symptoms, SV, and STIs. Depression and the sequelae of SV can undermine mood, impair psychosocial functioning, and interfere with students’ academic performance (ACHA, 2011). STIs may cause negative health consequences, including pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility (McCree & Rompalo, 2007).

The potential for negative health and social outcomes suggest the need for proactive educational efforts (cf. LaBrie et al., 2012). Educational programming can raise awareness and prompt discussion of the potential adverse health outcomes associated with hooking up. For example, flyers could be made available in residence halls and student health centers to inform youth about the association between hooking up and SV, given that many women do not perceive hookups as a context for SV (Littleton, Tabernik, Canales, & Backstrom, 2009). Student orientation and academic courses that address other health behaviors (e.g., alcohol use) might include discussion of hookups. Such sexual health promotion and risk reduction programs can help students who decide to hook up to do so more safely (e.g., with clear expectations, using condoms for STI prevention). Given the association between alcohol use and hooking up (Fielder & Carey, 2010a, 2010b; LaBrie et al., 2012), information about hookups could be incorporated into brief interventions to reduce risky alcohol use. Health care providers working with college students might encourage sexually active students to be tested for STIs and to use condoms with both hookup and romantic partners. Mental health professionals and sexual assault counselors should be aware of the risk for SV in the context of hookups.

Continued research is needed to elucidate the risks and benefits of hookup behavior for young women. Hookups are not inherently risky; indeed, in the present study, we did not find consistent evidence for a longitudinal association with depression and SV. However, hookups can be risky to the extent that they involve unprotected sex, multiple partners, sex while intoxicated, and SV (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Flack et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2012b). A balanced, non-judgmental approach is important, and research to investigate the perceived benefits of hookups for young people is needed (Owen et al., 2013). A more even-handed approach to hooking up will allow sexuality and health educators to help youths achieve their sex and intimacy goals in a well-informed, safe, and healthy manner.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R21-AA018257 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism to Michael P. Carey. The authors thank Annelise Sullivan for her assistance with data collection and the Center for AIDS Research (P30-AI050409) at Emory University for conducting the STI testing.

Footnotes

Participants who completed all 13 surveys (n = 309) and those who missed one or more surveys (n = 174) were compared on demographic variables, baseline alcohol use, and pre-college hookup and romantic sexual behavior, depression, SV, and STIs. The only difference was that those who completed all 13 surveys (M = 0.74) reported fewer pre-college SV events than those who missed one or more surveys (M = 1.40), t(265) = 2.43, p = .02.

Contributor Information

Robyn L. Fielder, Department of Psychology, Syracuse University, and Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital

Jennifer L. Walsh, Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital, and Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University

Kate B. Carey, Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, and Center for Alcohol and Addiction Studies, Brown University

Michael P. Carey, Centers for Behavioral and Preventive Medicine, The Miriam Hospital, and Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior and Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences, Brown University

References

- Abbey A, BeShears R, Clinton-Sherrod AM, McAuslan P. Similarities and differences in women’s sexual assault experiences based on tactics used by the perpetrator. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2004;28:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbey A, Zawacki T, Buck PO, Clinton AM, McAuslan P. Alcohol and sexual assault. Alcohol Research and Health. 2001;25:43–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Epel ES, Castellazzo G, Ickovics JR. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychology. 2000;19:586–592. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College Health Association. American College Health Association-National College Health Assessment II: Reference group data report Fall 2010. Linthicum, MD: Author; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.achancha.org/docs/ACHA-NCHA-II_ReferenceGroup_DataReport_Fall2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong EA, England P, Fogarty ACK. Accounting for women’s orgasm and sexual enjoyment in college hookups and relationships. American Sociological Review. 2012;77:435–462. doi: 10.1177/0003122412445802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft J, Janssen E, Strong D, Carnes L, Vukadinovic Z, Long JS. The relation between mood and sexuality in heterosexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2003;32:217–230. doi: 10.1023/A:1023409516739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Mooijaart A. Choice of structural model via parsimony: A rationale based on precision. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;106:315–317. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin MM, Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Donnellan MB, Hudson M, Weisskirch RS, Caraway SJ. Risky business: Is there an association between casual sex and mental health among emerging adults? Journal of Sex Research. 2013 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.772088. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogle KA. Hooking up: Sex, dating, and relationships on campus. New York: New York University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw C, Kahn AS, Saville BK. To hook up or date: Which gender benefits? Sex Roles. 2010;62:661–669. doi: 10.1007/s11199-010-9765-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite SR, Delevi R, Fincham FD. Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01248.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brousseau MM, Bergeron S, Hébert M, McDuff P. Sexual coercion victimization and perpetration in heterosexual couples: A dyadic investigation. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9617-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AL, Testa M, Messman-Moore TL. Psychological consequences of sexual victimization resulting from force, incapacitation, or verbal coercion. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:898–919. doi: 10.1177/1077801209335491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging. 2010;25:453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0017216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caliendo AM, Jordan JA, Green AM, Ingersoll J, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM. Real-time PCR improves detection of Trichomonas vaginalis infection compared with culture using self-collected vaginal swabs. Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005;13:145–150. doi: 10.1080/10647440500068248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charnigo R, Noar SM, Garnett C, Crosby R, Palmgreen P, Zimmerman RS. Sensation seeking and impulsivity: Combined associations with risky sexual behavior in a large sample of young adults. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50:480–488. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.652264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civic D. College students’ reasons for nonuse of condoms within dating relationships. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2000;26:95–105. doi: 10.1080/009262300278678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton SE, van Dulmen MHM. Casual sexual relationships and experiences in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood. 2013;1:138–150. doi: 10.1177/2167696813487181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crown L, Roberts LJ. Against their will: Young women’s nonagentic sexual experiences. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2007;24:385–405. doi: 10.1177/0265407507077228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ. A latent curve framework for the study of developmental trajectories in adolescent substance use. In: Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, editors. Multivariate applications in substance use research: New methods for new questions. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- England P, Shafer EF, Fogarty ACK. Hooking up and forming romantic relationships on today’s college campuses. In: Kimmel M, editor. The gendered society reader. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 531–547. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Calzo JP, Smiler AP, Ward LM. “Anything from making out to having sex”: Men’s negotiations of hooking up and friends with benefits scripts. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:414–424. doi: 10.1080/00224490902775801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshbaugh EM, Gute G. Hookups and sexual regret among college women. Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;148:77–90. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.148.1.77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Are hookups replacing romantic relationships? A longitudinal study of first-year female college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2013;52:657–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey MP. Predictors and consequences of sexual “hookups” among college students: A short-term prospective study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010a;39:1105–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9448-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey MP. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual hookups among first-semester female college students. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2010b;36:346–359. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2010.488118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack WF, Caron ML, Leinen SJ, Breitenbach KG, Barber AM, Brown EN, Stein HC. “The red zone”: Temporal risk for unwanted sex among college students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:1177–1196. doi: 10.1177/0886260508314308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flack WF, Daubman KA, Caron ML, Asadorian JA, D’Aureli NR, Gigliotti SN, Stine ER. Risk factors and consequences of unwanted sex among university students: Hooking up, alcohol, and stress response. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2007;22:139–157. doi: 10.1177/0886260506295354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forke CM, Myers RK, Catallozzi M, Schwarz DF. Relationship violence among female and male college undergraduate students. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162:634–641. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin CA. Physically forced, alcohol-induced, and verbally coerced sexual victimization: Assessing risk factors among university women. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2010;38:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin WR, Kruse MI. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1497–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Reiber C, Massey SG, Merriweather AM. Sexual hookup culture: A review. Review of General Psychology. 2012;16:161–176. doi: 10.1037/a0027911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Olchowski A, Gilreath T. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science. 2007;8:206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grello CM, Welsh DP, Harper MS. No strings attached: The nature of casual sex in college students. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:255–267. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell ZAT, Slane JD, Klump KL. Predictors of alcohol problems in college women: The role of depressive symptoms, disordered eating, and family history of alcoholism. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:252–257. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldman C, Wade L. Hook-up culture: Setting a new research agenda. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2010;7:323–333. doi: 10.1007/s13178-010-0024-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs MM, van der Pol B, Totten P, Gaydos CA, Wald A, Warren T, Martin DH. From the NIH: Proceedings of a workshop on the importance of self-obtained vaginal specimens for detection of sexually transmitted infections. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2008;35:8–13. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31815d968d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman A, Sillars A. Talk about “hooking up”: The influence of college student social networks on nonrelationship sex. Health Communication. 2012;27:205–216. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.575540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: A program for missing data. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler P. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut-Becher JR, Aral SO. Gap length: An important factor in sexually transmitted disease transmission. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2003;30:221–225. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Ghaidarov TM, Lac A, Kenney SR. Hooking up in the college context: The event-level effects of alcohol use and partner familiarity on hookup behaviors and contentment. Journal of Sex Research. 2012 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.714010. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert TA, Kahn AS, Apple KJ. Pluralistic ignorance and hooking up. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:129–133. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Morrison DM, Hoppe MJ, Beadnell B, Gillmore MR. Retrospective assessment of the association between drinking and condom use. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:773–776. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Blayney JA, Dent DV, Kaysen DL. What is hooking up? Examining definitions of hooking up in relation to behavior and normative perceptions. Journal of Sex Research. 2012a doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.706333. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Granato H, Blayney JA, Lostutter TW, Kilmer JR. Predictors of hooking up sexual behaviors and emotional reactions among U.S. college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012b;41:1219–1229. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Tabernik H, Canales EJ, Backstrom T. Risky situation or harmless fun? A qualitative examination of college women’s bad hook-up and rape scripts. Sex Roles. 2009;60:793–804. doi: 10.1007/s11199-009-9586-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magid V, MacLean MG, Colder CR. Differentiating between sensation seeking and impulsivity through their mediated relations with alcohol use and problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2046–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCree DH, Rompalo AM. Biological and behavioral risk factors associated with STDs/HIV in women: Implications for behavioral interventions. In: Aral SO, Douglas JM, Lipshutz JA, editors. Behavioral interventions for prevention and control of sexually transmitted diseases. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mendle J, Ferrero J, Moore SR, Harden KP. Depression and adolescent sexual activity in romantic and nonromantic relational contexts: A genetically-informative sibling comparison. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:51–63. doi: 10.1037/a0029816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minow JC, Einolf CJ. Sorority participation and sexual assault risk. Violence Against Women. 2009;15:835–851. doi: 10.1177/1077801209334472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus (Version 5) [Computer software] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén and Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Institutional Research and Assessment, Syracuse University. Institutional reporting. 2010 Retrieved from https://oira.syr.edu/Reporting/Reporting.htm.

- O’Grady MA, Tennen H, Armeli S. Depression history, depression vulnerability and the experience of everyday negative events. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:949–974. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2010.29.9.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okami P, Shackelford TK. Human sex differences in sexual psychology and behavior. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2001;12:186–241. doi: 10.1080/10532528.2001.10559798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Fincham FD. Young adults’ emotional reactions after hooking up encounters. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:321–330. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9652-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Fincham FD, Moore J. Short-term prospective study of hooking up among college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Quirk K, Fincham F. Toward a more complete understanding of reactions to hooking up among college women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy. 2013 doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.751074. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JJ, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Fincham FD. “Hooking up” among college students: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paik A. The contexts of sexual involvement and concurrent sexual partnerships. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42:33–42. doi: 10.1363/4203310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul EL, Hayes KA. The casualties of “casual” sex: A qualitative exploration of the phenomenology of college students’ hookups. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:639–661. doi: 10.1177/0265407502195006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paul EL, McManus B, Hayes A. “Hookups”: Characteristics and correlates of college students’ spontaneous and anonymous sexual experiences. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:76–88. doi: 10.1080/00224490009552023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schalling D. Psychopathy-related personality variables and the psychophysiology of socialization. In: Hare RD, Schalling D, editors. Psychopathic behaviour: Approaches to research. New York: Wiley; 1978. pp. 85–105. [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, Barrett AE. Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:168–182. doi: 10.1177/0022146510372343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söchting I, Fairbrother N, Koch WJ. Sexual assault of women: Prevention efforts and risk factors. Violence Against Women. 2004;10:73–93. doi: 10.1177/1077801203255680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepp LS. Unhooked: How young women pursue sex, delay love, and lose at both. New York: Riverhead Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson RD. Hooking up in young adulthood: A review of factors influencing the sexual behavior of college students. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 2010;24:98–115. doi: 10.1080/87568220903558596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Hoffman JH, Livingston JA. Alcohol and sexual risk behaviors as mediators of the sexual victimization-revictimization relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:249–259. doi: 10.1037/a0018914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Justice. Attorney General Eric Holder announces revisions to the Uniform Crime Report’s definition of rape. 2012 Jan 6; Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/news/pressrel/press-releases/attorney-general-eric-holder-announces-revisions-to-the-uniform-crime-reports-definition-of-rape.

- Weinstock H, Berman S, Cates W. Sexually transmitted diseases among American youth: Incidence and prevalence estimates, 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36:6–10. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.6.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]