Abstract

Over the last several decades, development of various imaging techniques such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography greatly facilitated the early detection of cancer. Another important aspect that is closely related to the survival of cancer patients is complete tumor removal during surgical resection. The major obstacle in achieving this goal is to distinguish between tumor tissue and normal tissue during surgery. Currently, tumor margins are typically assessed by visual assessment and palpation of the tumor intraoperatively. However, the possibility of microinvasion to the surrounding tissues makes it difficult to determine an adequate tumor-free excision margin, often forcing the surgeons to perform wide excisions including the healthy tissue that may contain vital structures. It would be ideal to remove the tumor completely, with minimal safety margins, if surgeons could see precise tumor margins during the operation. Molecular imaging with optical techniques can visualize the tumors via fluorophore conjugated probes targeting tumor markers such as proteins and enzymes that are upregulated during malignant transformation. Intraoperative use of this technique may facilitate complete excision of the tumor and tumor micromasses located beyond the visual capacity of the naked eye, ultimately improving the clinical outcome and survival rates of cancer patients.

Keywords: molecular imaging, image-guided surgery, optical imaging, tumor margin, Cerenkov luminescence, intraoperative imaging, cancer

INTRODUCTION

Appropriate management of diseases is an integral part of health care. The main goal of surgery is to repair, remove, or correct diseased tissues while avoiding unnecessary damage to healthy structures. Sufficient control of cancer progression with surgery in a single step operation will significantly reduce the surgical morbidity as well as the healthcare cost. Adequate visualization of the tumor (margin) is a necessary requirement for achieving the main goal of surgery [1]. Recent advances in technology have led to concomitant innovations of surgical tools. However, to ensure a tumor-free excision margin during surgery remains a major challenge in clinical oncology. Surgeons usually rely on macroscopic findings to detect tumor margins and leave large safety margins to remove the whole tumor mass [2]. Intraoperative frozen section analysis is widely used to determine the margins of the tumor during excision, however this method is quite time consuming and requires the expertise of well-trained personnel.

The emerging field of intraoperative optical imaging allows immediate differentiation between normal and diseased tissue beyond gross anatomical distortion or discoloration. This can offer more complete removal of diseased tissue and minimal inadvertent injury to vital structures [3]. Many diseases may alter one or more of the measurable optical tissue properties, thereby creating an endogenous source of contrast. Much of the early research in optical diagnostics relied on such alterations in the optical properties of naturally existing chromophores, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase. Yet, non-targeted imaging based on autofluorescence has not shown a compelling performance in clinical detection and is not widely used in surgical or endoscopic detection [4,5].

Optical imaging agents such as organic fluorophores, metallic nanoparticles, and semiconductor quantum dots (QD) can be conjugated to targeting moieties to recognize various tumor biomarkers [4-11]. These targeted probes can be used for real-time guidance of tumor excision during oncologic surgery [4,5], as well as other applications across many disciplines in biology and medicine [7]. Image-guided surgery using optical techniques requires an efficient combination of molecular probes and signal detection systems suitable for intraoperative use. In the broadest sense, molecularly targeted optical imaging incorporates biomarker discovery, contrast agent synthesis/optimization, and imaging instrumentation. In this review, we will summarize the molecular targets and imaging probes for molecularly targeted intraoperative optical imaging guided surgery in both preclinical and clinical settings.

FLUOROPHORES FOR INTRAOPERATIVE OPTICAL IMAGING

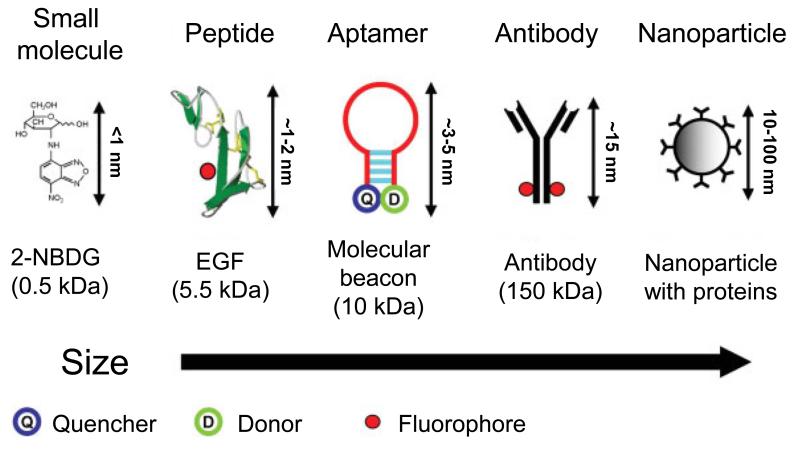

Tumor cells or biomarkers can be imaged using probes conjugated to an optically active reporter (e.g., fluorophore). Antibodies, antibody fragments, and biologically derived peptides contain amine, carboxyl, or thiol groups that can allow the conjugation of fluorophore for optical imaging (Fig. 1). Fluorescently labeled small molecules and nanoparticle-based optical agents (e.g., gold nanoparticles and QDs) have also been widely used (Fig. 1) [7]. To obtain a reliable separation of tumor and normal tissues, the specific signal from the tumor needs to be increased by least 3-4 fold in comparison to the signal from the normal tissues to yield a high signal-to-background ratio (SBR).

Figure 1.

Representative molecular specific optical imaging agents are shown from left to right in order of increasing size. Adapted from reference [7].

Conventional Fluorescence

The probes used for conventional fluorescence imaging are typically in the visible light spectrum (400-600 nm), which results in low SBR due to the relatively high level of autofluorescence from the tissue. Moreover, visible light is significantly absorbed by biologic chromophores, in particular hemoglobin, which limits the depth of signal penetration to a few millimeters. In most cases, the light properties within this spectrum are not sufficient to obtain the required sensitivity and specificity to make optical imaging an adequate technique for image-guided surgery in the clinic [4,5].

Near-Infrared (NIR) Fluorescence

Fluorescent agents that emit in the NIR region (650-900 nm) have several advantages over conventional fluorescent agents. The absorption coefficient of tissue is at a minimum when using light in the NIR spectrum since hemoglobin absorbs light mostly in the visible light spectrum (<600 nm) while other major tissue components (e.g., water and lipids) absorb light in the infrared range (>900 nm). This provides an optical imaging window from approximately 650 to 900 nm, which exhibits significantly decreased light scattering and nonspecific autofluorescence, as well as increased tissue penetration depth of signal [6]. These features make NIR fluorescence imaging desirable for intraoperative image-guided surgery, which is quite sensitive and can be used across the macroscopic and microscopic levels.

However, in contrary to autofluorescence, NIR fluorescent probes require external excitation with suitable wavelengths to emit light. External excitation non-selectively stimulates both the targeted fluorophores and the non-targeted fluorophores in the imaging field of view. Consequently, a background signal is detected which may be high enough to hinder the specific signal originating from the targeted tissue, especially when the target molecule is expressed at low levels [7]. Recent efforts to increase the SBR in optical imaging have led to the development of a new class of probes that become activated only under certain biological conditions (e.g., in the presence of tumor-associated enzymes, after internalization into the targeted cells, altered pH, etc.), which can exhibit minimal background fluorescence. For example, Weissleder et al. developed a protease-activatable probe based on multiple Cy5.5 molecules which are self-quenched [12], and the fluorescence signal is detectable only when the probe is cleaved by targeted enzymes such as cathepsins and matrix metalloproteases.

Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are of significant interest as fluorescent probes for optical imaging. QDs are small nanocrystals (typically 2-15 nm diameter) made of inorganic semiconductor materials that possess several physical properties desirable for optical imaging, such as high signal intensity, tunable fluorescence emission spectra favoring multiplexed imaging, and high photo stability [13-15].

Due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect, nanoparticles can passively accumulate in tumors more efficiently than in healthy tissues. The pathological basis of the EPR effect is the larger fenestrations in the endothelial layer of tumor vessels, which are built to supply fast-growing tumor cells, in addition to inefficient lymphatic drainage in the tumor tissue [16]. The EPR effect is not valid for low molecular weight fluorophores, in which fast extravasation from the blood vessels to the tissues is counterbalanced by inverse diffusion. In this regard, nanoparticles can be modified with fluorescent dyes and various targeting moieties on their surfaces, which can alter the biodistribution of low molecular weight fluorophores [4,7].

In an intriguing report, InP/ZnS QDs could provide intraoperative surgical guidance without the need for real-time excitation, thereby efficiently eliminating background autofluorescence, which makes it promising for image-guided surgery [17]. Of note, caution should be paid on the potential toxicity of nanoparticles, since QDs consist of a diverse group of elements including heavy metal cores which can be cytotoxic [18,19]. Silica nanoparticles are generally recognized to be more biocompatible and less toxic, although there are studies indicating signs of potential liver injury caused by these agents in mice [20]. Clearly, the clinical applications of QDs or other fluorescent nanoparticles are heavily dependent on the restriction of potential cytotoxic effects [4].

INTRAOPERATIVE OPTICAL IMAGING GUIDED SURGERY

A key feature of malignant cells is the limitless replicative potential that is facilitated by increased metabolism, high expression level of growth signaling factors/receptors, and increased tumor angiogenesis to supply sufficient oxygen and nutrients [21]. These characteristics of malignant cells can be explored to construct molecular probes for optical imaging and image-guided cancer surgery.

Image-Guided Surgery in Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is the most commonly studied tumor type for experimental image-guided surgery applications. Since galactosyl serum albumin (GSA) was found to be a specific probe for human ovarian adenocarcinomas, GSA-rhodamine green was investigated to help detect sub-millimeter intraperitoneal tumor metastases upon intraperitoneal injection in ovarian cancer bearing nude mice [22]. In another report, a NIR-activatable human GSA-based probe was synthesized, which contains a bacteriochlorin-based dye N-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone (NMP1) that has two unique absorption peaks in the green and NIR range but emits at a peak of 780 nm [23]. With this agent, in vivo peritoneal ovarian cancer metastases, located both superficially and deep in the abdominal cavity, could be clearly detected. Similarly, fluorescently labeled avidin (which targets surface lectins on ovarian cancer cells) was able to provide good spatial resolution and high SBR in mice with ovarian cancer, meeting the requirements of intraoperative optical imaging [24].

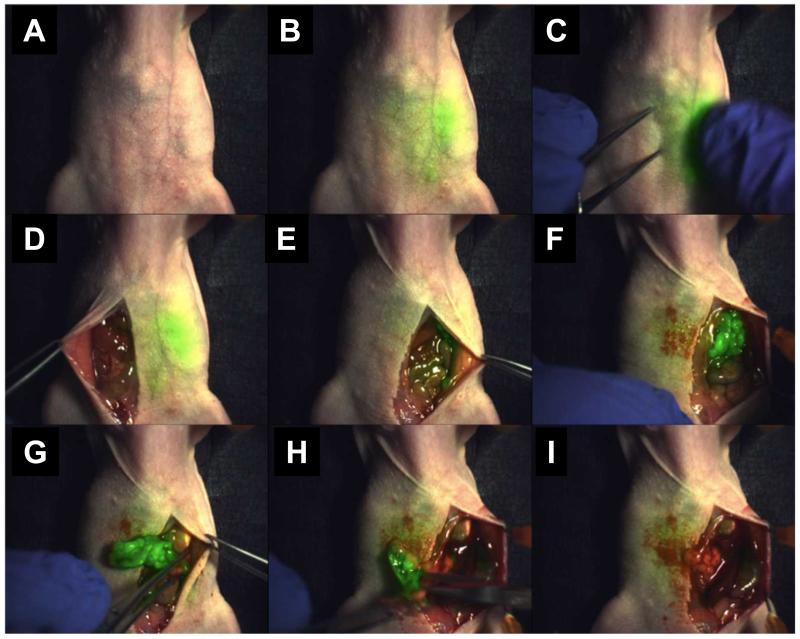

IntegriSense 680 (PerkinElmer, USA) is a commercially available fluorescent probe targeting integrin αvβ3, a protein that plays important roles in many cancer types [25,26]. This probe is composed of a potent non-peptidic integrin αvβ3 antagonist and an NIR fluorochrome with an excitation peak of 675±5 nm and an emission peak of 693 nm. In a recent study, ovarian tumor-bearing mice were injected intravenously (i.v.) with IntegriSense 680 and fluorescent spots and non-fluorescent tissue were identified and resected (Fig. 2) [27]. Histological analysis of the 58 samples that were excised with support of intraoperative optical imaging revealed a sensitivity of 95%, specificity of 88%, and a diagnostic accuracy of 96.5%. There were only two false-positive fluorescent spots due to autofluorescence from stool. The same probe was evaluated in other studies, including one using an oral cancer model, in a similar manner which gave clear demarcation of the tumors in vitro, in vivo, and on histological analysis with sufficient SBR [28,29].

Figure 2.

NIR fluorescence-guided tumor excision in an ovarian cancer model. The signal originating from the tumor tissue was visible through the skin under NIR laser (A-C). Following incision and exposure of the abdominal cavity, the tumor became visible in green color in the lower left quadrant (D-F). Excision was carried out under the guidance of fluorescent light (G,H), and no apparent fluorescence from residual tumor could be observed after the operation (I). Adapted from reference [27].

Another optical probe targeting integrin αvβ3 is a tetrameric cyclic Arg-Gly-Asp (cRGD) peptide containing nanoprobe which is commercially available under the name AngioLone™. An NIR fluorescent dye is linked to the AngioLone™ platform to give AngioStamp™ [30]. The same group developing AngioLone™ and AngioStamp™ developed a reflection-mode fluorescence molecular tomography (FMT) system with a handheld probe to facilitate image-guided surgery [31], and AngioStamp™ and FMT together could reliably detect the targets located within 5 mm beneath the surface with an average positional error of 0.5 mm laterally and 1.5 mm axially. In two other studies, another portable NIR optical imaging device (Fluobeam®) was used in combination with AngioStamp™ [32,33]. AngioStamp™ was injected i.v. into peritoneal cancer bearing mice, which were then operated with the aid of Fluobeam®. The number of detectable tumor nodules increased significantly in comparison to those that could be seen with the naked eye, and a significant reduction in operation time was reported [32,33]. These studies were important in terms of introducing new optical imaging systems, which are equally important as the development of specific probes for image-guided surgery. In addition to FMT and Flubeam®, FLARE™ camera system, Artemis™ camera system, and the Hamamatsu Photodynamic Eye have also been developed for intraoperative optical imaging [2].

Many of the exogenously injected probes for optical imaging can have potential side effects and/or toxicity. The use of non-toxic molecules, naturally used by the human body, as targeting probes may help decrease the potential toxicity of optical imaging probes. For example, folic acid is a vitamin excessively consumed by tumor cells, which often overexpress folate receptors to meet such demand. In an early report about a decade ago, a folic acid-based fluorescent probe was used to detect metastatic ovarian cancer loci of sub-millimeter size, which was able to confer sharp distinction between tumor and normal tissues [34]. Negligible toxicity of folic acid, as demonstrated in this study, promoted the first clinical application of intraoperative optical imaging guided surgery as discussed later in this review.

Bevacizumab and trastuzumab are anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) antibodies. These antibodies have been labeled with the NIR dye IRDye 800CW for both serial in vivo and intraoperative optical imaging applications [35]. Real-time intraoperative imaging using these probes helped to detect VEGF-positive subcutaneous ovarian tumors and HER2-positive intraperitoneal gastric tumors in athymic nude mice. In another interesting study, a mouse model of ovarian cancer was created by co-injecting animals with two distinct cell lines so that the mice simultaneously bore tumors with two distinct ovarian cancer phenotypes (HER2+/RFP− and HER2-/RFP+, RFP denotes red fluorescent protein) [36]. Multicolor fluorescence imaging was carried out with this model, in which HER2 was targeted with a trastuzumab-rhodamine green conjugate to create green tumor implants, whereas the RFP plasmid created red tumor implants. It was demonstrated that real-time in vivo multicolor imaging is feasible and the fluorescence characteristics can be used to guide surgical removal of ovarian cancer.

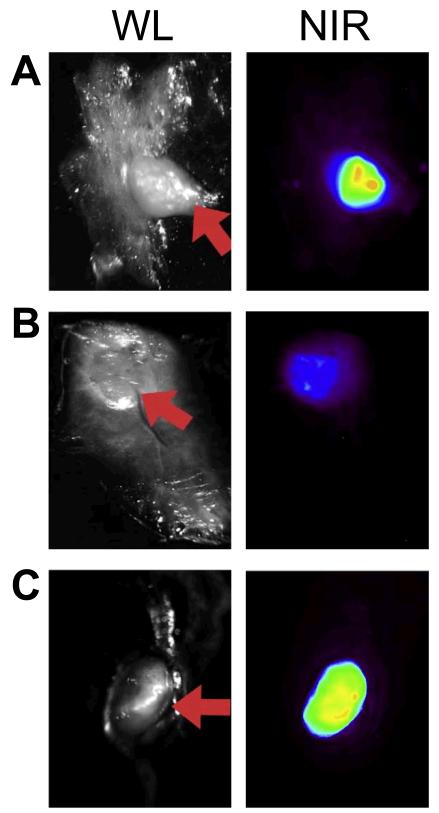

A protease activatable NIR probe, termed ProSense750, was evaluated in a murine model of ovarian peritoneal carcinomatosis [37]. Metastatic foci were imaged and excised under white light (WL) and NIR light following i.v. administration of ProSense 750 (Fig. 3). Different from many other studies, the ability to account for variations in fluorescence signal intensity due to changes in distance between the catheter and target lesion was evaluated in this study. Based on 52 histologically validated samples, the sensitivity for WL imaging was 69%, while the sensitivity for NIR imaging was 100%. The effect of intraoperative distance changes upon fluorescence intensity was corrected in real-time, resulting in a decrease from 89% to 5% in signal variance during fluorescence laparoscopy.

Figure 3.

The ovarian cancer foci in a peritoneal carcinomatosis model can be seen under white light (WL, red arrows) and NIR, which are located in the omentum (A), adherent to the peritoneum (B), and invading a para-aortic lymph node (C). Adapted from reference [37].

Image-Guided Surgery in other Tumor Types

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a surface glycoprotein that is highly expressed in human prostate cancer cells. Recently, an optical probe composed of a PSMA–targeting ligand conjugated with IRDye 800CW was employed to guide the resection of PSMA-positive prostate tumors in mice, where discrete NIR fluorescence could be elicited from 2 of 3 PSMA-positive tumors and the surgical margins were negative in all excised specimens [38]. In another study, PSMA was targeted using an activatable monoclonal antibody-indocyanine green (ICG) conjugate [39]. Prior to binding of the humanized antibody J591 to PSMA and cellular internalization, the probe yielded little signal. However, an 18-fold activation was observed after binding, which enabled specific detection of PSMA-positive tumors up to 10 days after i.v. administration of a low dose of the probe.

Another “smart” optical probe is activatable cell-penetrating peptide (ACPP) that is formed by coupling of fluorescently labeled, polycationic cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) to a neutralizing peptide via a cleavable linker [40]. Upon exposure to proteases, commonly found in tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment, the linker is cleaved to dissociate the inhibitory peptide, which allows the CPP to enter tumor cells. In the MDA-MB-435 xenograft model, Cy5-labeled ACPP and ACPP conjugated to dendrimers (ACPPD) could effectively delineate the margin between tumor and adjacent tissue, resulting in improved precision of tumor resection [40].

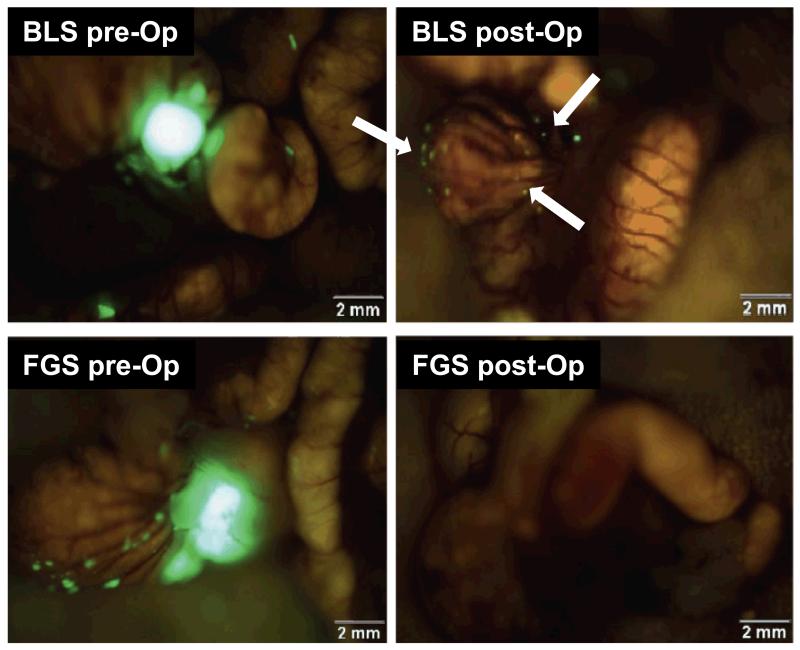

In another report, pancreatic tumor was detected intraoperatively using a different strategy [41]. A fluorescence laparoscopy model was developed with the use of a Xenon light source, which permitted facile, real-time imaging and localization of GFP-expressing pancreatic tumors within the mouse abdomen. In other studies, fluorophore conjugated anti-carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) antibody and anti-CA19-9 antibody were also investigated for enhanced detection of tumors during laparotomy in orthotopic mouse models of pancreatic and colon cancer [42,43]. In two recent reports from the same research group, similar tumor models were studied without the use of anti-CEA or anti-CA19-9 probes to visualize the tumors [44,45]. Instead, the investigators transfected the BxPC-3 pancreatic cancer and HCT-116-GFP colon cancer cell lines with RFP and visualized tumors intraoperatively under fluorescent light (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Images acquired before and after tumor removal using fluorescence image-guided surgery (FGS) or bright light surgery (BLS) in an orthotopic mouse model of HCT-116-GFP colon cancer in nude mice. Residual tumors could be detected under fluorescent light postoperatively in an animal underwent BLS (white arrows). The enhanced ability to visualize tumor margins in FGS led to more complete resection of the tumor nodules (lower right panel).Adapted from reference [45].

Tumor cells depend on increased angiogenesis (the formation of new vessels) to maintain their metabolic needs, which is an established hallmark of cancer [21]. CD105 (also called endoglin) plays diverse roles during tumor angiogenesis and is a validated diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic target in cancer [46-48]. TRC105, a chimeric anti-CD105 antibody, has been extensively studied in our laboratory over the last several years for molecular imaging of tumor angiogenesis [49-60], as well as physiological angiogenesis [61,62]. Using dual-labeled TRC105 with a NIR dye (IRDye 800CW) and a positron emitter (89Zr or 64Cu to yield 89Zr-Df-TRC105-800CW or 64Cu-NOTA-TRC105-800CW, respectively), we have used the resulting probes to non-invasively detect experimental lung metastases with positron emission tomography (PET), which was established by i.v. injection of firefly luciferase-transfected 4T1 murine breast cancer cells into BALB/c mice [60,63]. In addition, tumor fluorescence signal of the i.v. injected agents also offered intraoperative image guidance for the removal of subcutaneous tumors [60,63]. Such dual-labeled PET/NIR fluorescent agents may be particularly useful in future clinical cancer patient management by employing the whole-body PET scan to identify the location of tumor(s), and NIRF imaging to guide tumor resection.

OPTICAL IMAGING GUIDED SURGERY IN THE CLINICAL SETTING

Due to the highly encouraging preclinical data and recent availability of light-sensitive cameras that can be used in the surgical room, optical imaging guided surgery has attracted tremendous attention over the last several years. However, ICG and methylene blue, which cannot be covalently attached to a targeting molecule, have long been the only fluorophores approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical use [64,65]. To date, only a few tumor-targeted imaging agents have been investigated in clinical studies, opening new avenues for clinical applications of optical image-guided surgery.

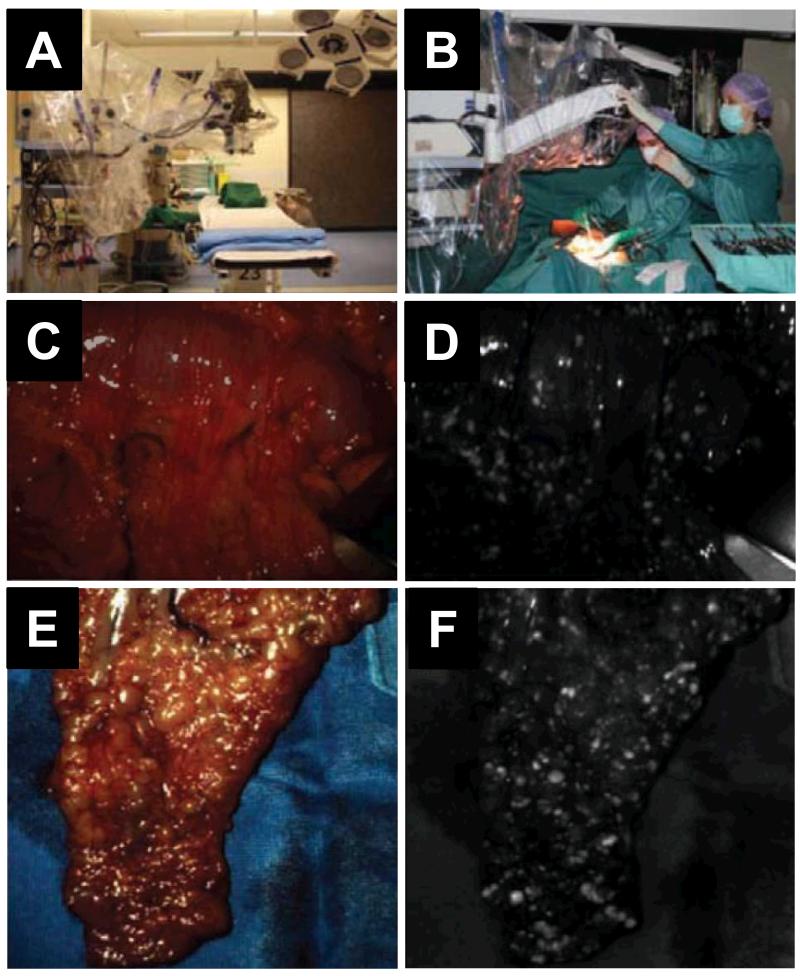

The first-in-human use of intraoperative tumor-specific optical imaging for real-time surgical visualization of tumor tissue was performed in patients undergoing an exploratory laparotomy for suspected ovarian cancer (Fig. 5) [66]. FITC conjugated folate was used for targeting folate receptor-α (FR-α) and imaging was carried out with a multispectral intraoperative optical imaging system, which enabled real-time image-guided excision of fluorescent tumor deposits of <1 mm in size. All fluorescent tissue was confirmed to be malignant with histopathology. Tumor-specific fluorescence signal originating from disseminated tumor deposits could be detected up to 8 h after injection during a prolonged procedure. More importantly, healthy tissue did not show any fluorescence signal either in vivo, ex vivo, or during histopathological validation. The mean SBR (as compared to healthy peritoneal surface) of 3.1 ± 0.8 can potentially be significantly improved when a NIR dye is used instead of FITC, which emits in the green wavelength range and is far from optimal for imaging applications.

Figure 5.

The first clinical investigation of intraoperative tumor-specific optical imaging in a patient with high-grade ovarian carcinoma and extensive peritoneal carcinomatosis. A. Operation room set up after draping the instrument. B. A photo taken during surgery. C & E. Intraoperative white light screenshots of two different areas of abdominal cavity. D & F. Corresponding fluorescent images showing the tumor nodules as bright spots. Adapted from reference [66].

When the target tissue lacks an extended vascular network, topical delivery may be used as an alternative to i.v. injection, which can have fewer side effects. Increased absorption of the probe through the skin or other surfaces can occur by incorporating chemical permeation enhancers in the contrast agent formulation, which can be successful for delivery of small molecules and peptides but not antibodies or nanoparticles [67]. In a recent study, wheat germ agglutinin labeled with AlexaFluor 680 was investigated to target cell surface glycans that are altered in the progression of Barrett’s esophagus [68]. Esophageal surgical specimens were topically sprayed with the fluorescent lectin, which demonstrated significant signal enhancement for the detection of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. The main advantage of this technique was that lectins, just like folic acid, are part of a regular diet hence have very low toxicity. In another interesting preclinical report, topical spraying of fluorescent agents was employed with the use of a rapidly activatable fluorescent probe [65]. This probe can be readily activated by a cell-surface enzyme of glutathione metabolism, which is highly expressed in various types of human cancer.

Despite the promising advancement in the development of molecular specific optical imaging agents, fast clinical translation and broad clinical use of optical image-guided surgery is heavily dependent upon prompt solutions to several problems. Adequate access of injected probes to the neoplastic microenvironment is the first requirement for generation of tumor-specific signal. The access to target molecules located on the surface of tumor cells or tumor vasculature is relatively easy, when compared to intracellular targets. However, in many cases, sufficient solid tumor penetration of the probe can be a major issue for using macromolecular and nanoparticle-based agents in optical image-guided surgery, which may result in suboptimal uptake in the targeted tissue after i.v. injection [69]. In addition to adequate target binding affinity and efficient delivery, optimal clearance time and demonstrated lack of toxicity at clinically appropriate doses are also fundamental requirements for clinical translation/success of an optical imaging probe. Furthermore, pharmacokinetic studies may be necessary to determine the optimal post-injection time window for image-guided surgery when the SBR is relatively low [7].

CERENKOV LUMINESCENCE IMAGING (CLI) AND IMAGE-GUIDED SURGERY

Cerenkov luminescence is a phenomenon that occurs when a charged β-particle travels through a medium at a velocity greater than that of light in the same medium. Dependent upon their energy, charged β-particles can induce polarization of molecules in the medium, which can emit photons upon relaxation [64]. In 2009, the concept of Cerenkov luminescence imaging (CLI) was introduced [70]. As a technique that bridges optical imaging and radionuclide-based imaging, CLI has many desirable characteristics such as high sensitivity, high resolution, low cost, wide availability, and relatively high throughput. Since CLI does not require external excitation source, it does not suffer from autofluorescence or reflection of excitation light which can give very low background signal [64]. Perhaps more importantly, many commercially available radionuclide-based probes are already approved by the FDA, such as 18F-FDG [71-73], which can greatly facilitate potential clinical use of CLI. It is believed that CLI has the potential to circumvent many of the problems of optical imaging by providing almost real-time, quantitative information on radiotracer uptake with high sensitivity, while limiting the radiation dose to patients and surgical teams [74,75].

In one report, CLI with 89Zr-DFO-trastuzumab was carried out for target specific, quantitative imaging of HER2-positive tumors in vivo [76]. HER2 specific uptake of 89Zr-DFO-trastuzumab in BT-474 (HER2-positive) versus MDA-MB-468 (HER2-negative) xenograft tumors in the same mice was demonstrated. In addition, this study also provided the proof for the feasibility of true CLI-guided, intraoperative surgical resection of tumors. Since the tumors could be visualized with optical imaging as late as 6 days post-injection of the PET tracer, the investigators suggested that upon clinical translation, a radiotracer can be used first to determine the exact tumor size and location using pre-surgery PET, followed by definition of accurate tumor margins intraoperatively, and finally confirm the success of the operation (i.e., complete tumor removal) with CLI before closure and post-surgery PET.

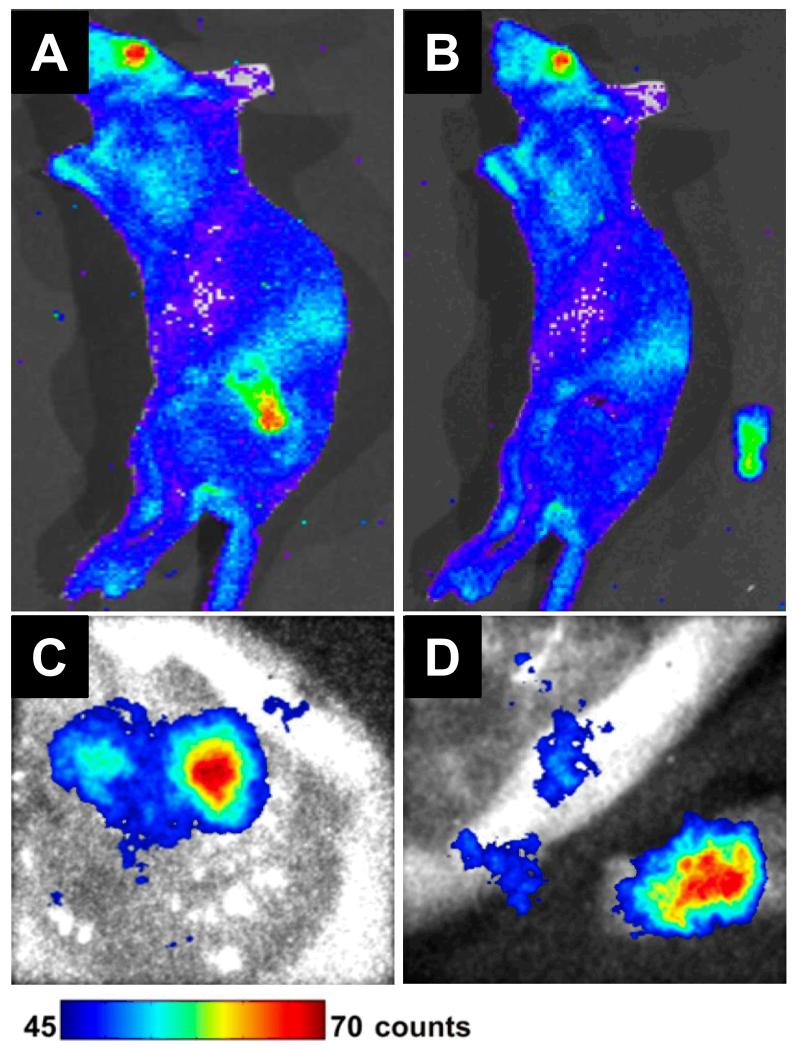

About a year later, the first prototype system that is amenable to CLI in the clinic was developed and tested using mice bearing subcutaneous C6 glioma tumors [77]. The animals were injected i.v. with 18F-FDG and CLI was performed using an optical fiber bundle and an intensified charge-coupled device (CCD) camera before and after surgical removal of the tumor (Fig. 6). Although this study demonstrated the feasibility of CLI for guiding the resection of tumor tissues, much further optimization of the system will be needed to provide sufficient sensitivity for identification of small tumor nodules in the clinical setting.

Figure 6.

Cerenkov luminescence imaging guided resection of a C6 glioma after administration of 37 MBq (1 mCi) of 18F-FDG into tumor-bearing mice. The mice were scanned in an IVIS optical imaging system before and after tumor removal (A, B), or a prototype fiber based Cerenkov luminescence imaging system (C, D). Adapted from reference [77].

CONCLUSIONS

To effectively use optical imaging for surgical guidance, only viewing the fluorescence of the contrast agent is not enough. Ideally, fluorescence images should be superimposed in real-time and in precise spatial register with reflectance images showing the morphology of tumor/normal tissue and the location of surgical instrument. Significant future advances in signal detection, SBR optimization, and intraoperative display are needed for large-scale implementation of optical image-guided surgery in cancer patients. The preclinical data obtained to date and a few recent clinical pilot studies have spurred much excitement. However, much more translational effort and well-planned multidisciplinary studies are required to move this exciting technology forward into day-to-day cancer patient management. The parallel development of high quality fluorescent agents with superb tumor specificity and low non-specific binding to normal tissue, as well as imaging instrumentation to detect and display the intraoperative images, is a must to overcome the many challenges facing optical image-guided surgery.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported, in part, by the University of Wisconsin - Madison, the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NCI 1R01CA169365), the Department of Defense (W81XWH-11-1-0644), and the American Cancer Society (125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE).

REFERENCES

- [1].Orosco R, Tsien R, Nguyen Q. Fluorescence Imaging in Surgery. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2013 doi: 10.1109/RBME.2013.2240294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Keereweer S, Kerrebijn JD, van Driel PB, Xie B, Kaijzel EL, Snoeks TJ, Que I, Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, Mieog JS, Vahrmeijer AL, van de Velde CJ, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Lowik CW. Optical image-guided surgery--where do we stand? Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;13:199–207. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0373-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Metildi CA, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Fluorescence-guided surgery and fluorescence laparoscopy for gastrointestinal cancers in clinically-relevant mouse models. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:290634. doi: 10.1155/2013/290634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Keereweer S, Sterenborg HJ, Kerrebijn JD, Van Driel PB, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Lowik CW. Image-guided surgery in head and neck cancer: current practice and future directions of optical imaging. Head Neck. 2012;34:120–126. doi: 10.1002/hed.21625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Garcia-Allende PB, Glatz J, Koch M, Ntziachristos V. Enriching the Interventional Vision of Cancer with Fluorescent and Optoacoustic Imaging. J Nucl Med. 2013 doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.099796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Merian J, Gravier J, Navarro F, Texier I. Fluorescent nanoprobes dedicated to in vivo imaging: from preclinical validations to clinical translation. Molecules. 2012;17:5564–5591. doi: 10.3390/molecules17055564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pierce MC, Javier DJ, Richards-Kortum R. Optical contrast agents and imaging systems for detection and diagnosis of cancer. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1979–1990. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Huang X, Lee S, Chen X. Design of “smart” probes for optical imaging of apoptosis. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;1:3–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wu Y, Zhang W, Li J, Zhang Y. Optical imaging of tumor microenvironment. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;3:1–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yigit MV, Medarova Z. In vivo and ex vivo applications of gold nanoparticles for biomedical SERS imaging. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:232–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nolting DD, Nickels ML, Guo N, Pham W. Molecular imaging probe development: a chemistry perspective. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:273–306. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Weissleder R, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A., Jr. In vivo imaging of tumors with protease-activated near-infrared fluorescent probes. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:375–378. doi: 10.1038/7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Michalet X, Pinaud FF, Bentolila LA, Tsay JM, Doose S, Li JJ, Sundaresan G, Wu AM, Gambhir SS, Weiss S. Quantum dots for live cells, in vivo imaging, and diagnostics. Science. 2005;307:538–544. doi: 10.1126/science.1104274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cai W, Hsu AR, Li ZB, Chen X. Are quantum dots ready for in vivo imaging in human subjects? Nanoscale Res Lett. 2007;2:265–281. doi: 10.1007/s11671-007-9061-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cai W, Hong H. In a “nutshell”: intrinsically radio-labeled quantum dots. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:136–140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. Tumor vascular permeability and the EPR effect in macromolecular therapeutics: a review. J Control Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chin PT, Buckle T, Aguirre de Miguel A, Meskers SC, Janssen RA, van Leeuwen FW. Dual-emissive quantum dots for multispectral intraoperative fluorescence imaging. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6823–6832. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kirchner C, Liedl T, Kudera S, Pellegrino T, Munoz Javier A, Gaub HE, Stolzle S, Fertig N, Parak WJ. Cytotoxicity of colloidal CdSe and CdSe/ZnS nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2005;5:331–338. doi: 10.1021/nl047996m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lewinski N, Colvin V, Drezek R. Cytotoxicity of nanoparticles. Small. 2008;4:26–49. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xie G, Sun J, Zhong G, Shi L, Zhang D. Biodistribution and toxicity of intravenously administered silica nanoparticles in mice. Arch Toxicol. 2010;84:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s00204-009-0488-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Gunn AJ, Hama Y, Koyama Y, Kohn EC, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Targeted optical fluorescence imaging of human ovarian adenocarcinoma using a galactosyl serum albumin-conjugated fluorophore. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:1727–1733. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Alexander VM, Sano K, Yu Z, Nakajima T, Choyke PL, Ptaszek M, Kobayashi H. Galactosyl human serum albumin-NMP1 conjugate: a near infrared (NIR)-activatable fluorescence imaging agent to detect peritoneal ovarian cancer metastases. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:1671–1679. doi: 10.1021/bc3002419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hama Y, Urano Y, Koyama Y, Kamiya M, Bernardo M, Paik RS, Krishna MC, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. In vivo spectral fluorescence imaging of submillimeter peritoneal cancer implants using a lectin-targeted optical agent. Neoplasia. 2006;8:607–612. doi: 10.1593/neo.06268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Cai W, Niu G, Chen X. Imaging of integrins as biomarkers for tumor angiogenesis. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:2943–2973. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Liu S, Park R, Conti PS, Li Z. “Kit like” (18)F labeling method for synthesis of RGD peptide-based PET probes. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;3:97–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Harlaar NJ, Kelder W, Sarantopoulos A, Bart J, Themelis G, van Dam GM, Ntziachristos V. Real-time near infrared fluorescence (NIRF) intra-operative imaging in ovarian cancer using an alpha(v)beta(3-)integrin targeted agent. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:590–595. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Keereweer S, Mol IM, Kerrebijn JD, Van Driel PB, Xie B, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Vahrmeijer AL, Lowik CW. Targeting integrins and enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect for optical imaging of oral cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:714–718. doi: 10.1002/jso.22102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Themelis G, Harlaar NJ, Kelder W, Bart J, Sarantopoulos A, van Dam GM, Ntziachristos V. Enhancing surgical vision by using real-time imaging of alphavbeta3-integrin targeted near-infrared fluorescent agent. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:3506–3513. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Wenk CH, Ponce F, Guillermet S, Tenaud C, Boturyn D, Dumy P, Watrelot-Virieux D, Carozzo C, Josserand V, Coll JL. Near-infrared optical guided surgery of highly infiltrative fibrosarcomas in cats using an anti-alpha(v)ss(3) integrin molecular probe. Cancer Lett. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zhao Q, Jiang H, Cao Z, Yang L, Mao H, Lipowska M. A handheld fluorescence molecular tomography system for intraoperative optical imaging of tumor margins. Med Phys. 2011;38:5873–5878. doi: 10.1118/1.3641877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Keramidas M, Josserand V, Righini CA, Wenk C, Faure C, Coll JL. Intraoperative near-infrared image-guided surgery for peritoneal carcinomatosis in a preclinical experimental model. Br J Surg. 2010;97:737–743. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mery E, Jouve E, Guillermet S, Bourgognon M, Castells M, Golzio M, Rizo P, Delord JP, Querleu D, Couderc B. Intraoperative fluorescence imaging of peritoneal dissemination of ovarian carcinomas. A preclinical study. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kennedy MD, Jallad KN, Thompson DH, Ben-Amotz D, Low PS. Optical imaging of metastatic tumors using a folate-targeted fluorescent probe. J Biomed Opt. 2003;8:636–641. doi: 10.1117/1.1609453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Terwisscha van Scheltinga AG, van Dam GM, Nagengast WB, Ntziachristos V, Hollema H, Herek JL, Schroder CP, Kosterink JG, Lub-de Hoog MN, de Vries EG. Intraoperative near-infrared fluorescence tumor imaging with vascular endothelial growth factor and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 targeting antibodies. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1778–1785. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Longmire M, Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Multicolor in vivo targeted imaging to guide real-time surgery of HER2-positive micrometastases in a twotumor coincident model of ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:1099–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Sheth RA, Upadhyay R, Stangenberg L, Sheth R, Weissleder R, Mahmood U. Improved detection of ovarian cancer metastases by intraoperative quantitative fluorescence protease imaging in a pre-clinical model. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Laydner H, Huang SS, Heston WD, Autorino R, Wang X, Harsch KM, Magi-Galluzzi C, Isac W, Khanna R, Hu B, Escobar P, Chalikonda S, Rao PK, Haber GP, Kaouk JH, Stein RJ. Robotic real-time near infrared targeted fluorescence imaging in a murine model of prostate cancer: a feasibility study. Urology. 2013;81:451–456. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Nakajima T, Mitsunaga M, Bander NH, Heston WD, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Targeted, activatable, in vivo fluorescence imaging of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) positive tumors using the quenched humanized J591 antibodyindocyanine green (ICG) conjugate. Bioconjug Chem. 2011;22:1700–1705. doi: 10.1021/bc2002715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nguyen QT, Olson ES, Aguilera TA, Jiang T, Scadeng M, Ellies LG, Tsien RY. Surgery with molecular fluorescence imaging using activatable cell-penetrating peptides decreases residual cancer and improves survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:4317–4322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910261107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Tran Cao HS, Kaushal S, Lee C, Snyder CS, Thompson KJ, Horgan S, Talamini MA, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Fluorescence laparoscopy imaging of pancreatic tumor progression in an orthotopic mouse model. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:48–54. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kaushal S, McElroy MK, Luiken GA, Talamini MA, Moossa AR, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Fluorophore-conjugated anti-CEA antibody for the intraoperative imaging of pancreatic and colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1938–1950. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0581-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].McElroy M, Kaushal S, Luiken GA, Talamini MA, Moossa AR, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Imaging of primary and metastatic pancreatic cancer using a fluorophoreconjugated anti-CA19-9 antibody for surgical navigation. World J Surg. 2008;32:1057–1066. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9452-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Metildi CA, Kaushal S, Hardamon CR, Snyder CS, Pu M, Messer KS, Talamini MA, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Fluorescence-guided surgery allows for more complete resection of pancreatic cancer, resulting in longer disease-free survival compared with standard surgery in orthotopic mouse models. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.02.021. discussion 135-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Metildi CA, Kaushal S, Snyder CS, Hoffman RM, Bouvet M. Fluorescenceguided surgery of human colon cancer increases complete resection resulting in cures in an orthotopic nude mouse model. J Surg Res. 2013;179:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Dallas NA, Samuel S, Xia L, Fan F, Gray MJ, Lim SJ, Ellis LM. Endoglin (CD105): a marker of tumor vasculature and potential target for therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1931–1937. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Fonsatti E, Altomonte M, Nicotra MR, Natali PG, Maio M. Endoglin (CD105): a powerful therapeutic target on tumor-associated angiogenetic blood vessels. Oncogene. 2003;22:6557–6563. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zhang Y, Yang Y, Hong H, Cai W. Multimodality molecular imaging of CD105 (Endoglin) expression. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2011;4:32–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hong H, Severin GW, Yang Y, Engle JW, Zhang Y, Barnhart TE, Liu G, Leigh BR, Nickles RJ, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression with 89Zr-Df-TRC105. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;39:138–148. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1930-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Hong H, Yang Y, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Barnhart TE, Nickles RJ, Leigh BR, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression during tumor angiogenesis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;38:1335–1343. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhang Y, Hong H, Engle JW, Bean J, Yang Y, Leigh BR, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of CD105 expression with a 64Cu-labeled monoclonal antibody: NOTA is superior to DOTA. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Zhang Y, Hong H, Engle JW, Yang Y, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Positron Emission Tomography and Optical Imaging of Tumor CD105 Expression with a Dual-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:645–653. doi: 10.1021/mp200592m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zhang Y, Hong H, Orbay H, Valdovinos HF, Nayak TR, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W. PET imaging of CD105/endoglin expression with a 61/64Cu-labeled Fab antibody fragment. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:759–767. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2334-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zhang Y, Hong H, Severin GW, Engle JW, Yang Y, Goel S, Nathanson AJ, Liu G, Nickles RJ, Leigh BR, Barnhart TE, Cai W. ImmunoPET and nearinfrared fluorescence imaging of CD105 expression using a monoclonal antibody duallabeled with 89Zr and IRDye 800CW. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4:333–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Engle JW, Hong H, Zhang Y, Valdovinos HF, Myklejord DV, Barnhart TE, Theuer CP, Nickles RJ, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of tumor angiogenesis with a 66Ga-labeled monoclonal antibody. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:1441–1448. doi: 10.1021/mp300019c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hong H, Yang K, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Feng L, Yang Y, Nayak TR, Goel S, Bean J, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Liu Z, Cai W. In vivo targeting and imaging of tumor vasculature with radiolabeled, antibody-conjugated nanographene. ACS Nano. 2012;6:2361–2370. doi: 10.1021/nn204625e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Hong H, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Nayak TR, Theuer CP, Nickles RJ, Barnhart TE, Cai W. In vivo targeting and positron emission tomography imaging of tumor vasculature with (66)Ga-labeled nano-graphene. Biomaterials. 2012;33:4147–4156. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hong H, Zhang Y, Orbay H, Valdovinos HF, Nayak TR, Bean J, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Positron emission tomography imaging of tumor angiogenesis with a (61/64)Cu-labeled F(ab’)(2) antibody fragment. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:709–716. doi: 10.1021/mp300507r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Shi S, Yang K, Hong H, Valdovinos HF, Nayak TR, Zhang Y, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Liu Z, Cai W. Tumor vasculature targeting and imaging in living mice with reduced graphene oxide. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3002–3009. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Zhang Y, Hong H, Nayak TR, Valdovinos HF, Myklejord DV, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Imaging tumor angiogenesis in breast cancer experimental lung metastasis with positron emission tomography, near-infrared fluorescence, and bioluminescence. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:663–674. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9344-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Orbay H, Zhang Y, Hong H, Hacker TA, Valdovinos HF, Zagzebski JA, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Positron Emission Tomography Imaging of Angiogenesis in a Murine Hindlimb Ischemia Model with Cu-Labeled TRC105. Mol Pharm. 2013;10:2749–2756. doi: 10.1021/mp400191w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Orbay H, Hong H, Zhang Y, Cai W. PET/SPECT imaging of hindlimb ischemia: focusing on angiogenesis and blood flow. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:279–287. doi: 10.1007/s10456-012-9319-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Hong H, Zhang Y, Severin GW, Yang Y, Engle JW, Niu G, Nickles RJ, Chen X, Leigh BR, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Multimodality Imaging of Breast Cancer Experimental Lung Metastasis with Bioluminescence and a Monoclonal Antibody Dual-Labeled with 89Zr and IRDye 800CW. Mol Pharm. 2012;9:2339–2349. doi: 10.1021/mp300277f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Chin PT, Welling MM, Meskers SC, Valdes Olmos RA, Tanke H, van Leeuwen FW. Optical imaging as an expansion of nuclear medicine: Cerenkov-based luminescence vs fluorescence-based luminescence. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2408-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Urano Y, Sakabe M, Kosaka N, Ogawa M, Mitsunaga M, Asanuma D, Kamiya M, Young MR, Nagano T, Choyke PL, Kobayashi H. Rapid cancer detection by topically spraying a gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase-activated fluorescent probe. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:110ra119. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].van Dam GM, Themelis G, Crane LM, Harlaar NJ, Pleijhuis RG, Kelder W, Sarantopoulos A, de Jong JS, Arts HJ, van der Zee AG, Bart J, Low PS, Ntziachristos V. Intraoperative tumor-specific fluorescence imaging in ovarian cancer by folate receptor-alpha targeting: first in-human results. Nat Med. 2011;17:1315–1319. doi: 10.1038/nm.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Asbill CS, El-Kattan AF, Michniak B. Enhancement of transdermal drug delivery: chemical and physical approaches. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2000;17:621–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bird-Lieberman EL, Neves AA, Lao-Sirieix P, O’Donovan M, Novelli M, Lovat LB, Eng WS, Mahal LK, Brindle KM, Fitzgerald RC. Molecular imaging using fluorescent lectins permits rapid endoscopic identification of dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Nat Med. 2012;18:315–321. doi: 10.1038/nm.2616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Balogh L, Nigavekar SS, Nair BM, Lesniak W, Zhang C, Sung LY, Kariapper MS, El-Jawahri A, Llanes M, Bolton B, Mamou F, Tan W, Hutson A, Minc L, Khan MK. Significant effect of size on the in vivo biodistribution of gold composite nanodevices in mouse tumor models. Nanomedicine. 2007;3:281–296. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Robertson R, Germanos MS, Li C, Mitchell GS, Cherry SR, Silva MD. Optical imaging of Cerenkov light generation from positron-emitting radiotracers. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:N355–365. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/16/N01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Alauddin MM. Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging with 18F-based radiotracers. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:55–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Eary JF, Hawkins DS, Rodler ET, Conrad EU., 3rd. 18F-FDG PET in sarcoma treatment response imaging. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;1:47–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Iagaru A. 18F-FDG PET/CT: timing for evaluation of response to therapy remains a clinical challenge. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011;1:63–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Xu Y, Liu H, Cheng Z. Harnessing the power of radionuclides for optical imaging: Cerenkov luminescence imaging. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:2009–2018. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.092965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Thorek D, Robertson R, Bacchus WA, Hahn J, Rothberg J, Beattie BJ, Grimm J. Cerenkov imaging - a new modality for molecular imaging. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012;2:163–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Holland JP, Normand G, Ruggiero A, Lewis JS, Grimm J. Intraoperative imaging of positron emission tomographic radiotracers using Cerenkov luminescence emissions. Mol Imaging. 2011;10:177–186. 171–173. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Liu H, Carpenter CM, Jiang H, Pratx G, Sun C, Buchin MP, Gambhir SS, Xing L, Cheng Z. Intraoperative imaging of tumors using Cerenkov luminescence endoscopy: a feasibility experimental study. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1579–1584. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]