Abstract

Objective

To date walking outcomes in cerebral palsy (CP) have been capacity-based (what a child does in structured setting). Physical activity performance (what a child really does in daily life) has been documented to influence the relationship of capacity-based gross motor measures to participation.(1) This study examines the relationship between walking performance and participation in mobility-related habits of daily life in children with CP.

Design

Cross-sectional prospective cohort study.

Setting

Regional pediatric specialty care centers

Participants

A cohort of 128 ambulatory children with CP ages 2–9 yrs, 41% female, and 49% having hemiplegia participated.

Interventions

Not Applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

Walking performance was quantified from a 5-day sample of StepWatch accelerometry data. Stride activity was summarized through the outcomes of average total strides/day (independent of intensity) and average number of strides/day at > 30 strides/minute (marker of intensity). Mobility-based participation was assessed by the Life Habits (Life-H) categories of Personal Care, Housing, Mobility, and Recreation. Regression models were developed controlling for gender, age, cognition, communication, pain, and body composition.

Results

Average total strides/day was positively associated with the Personal Care, Housing, Mobility, and Recreation Life-H categories (β = .34 to.41, p <.001). Average number of strides > 30 stride/min/day was associated with all categories (β = .54 to.60, p < .001).

Conclusions

Accelerometry-based walking activity performance is significantly associated with levels of participation in mobility-based life habits for ambulatory children with CP. Evaluation of other factors and the direction of relationships within the ICF is warranted to inform rehabilitation strategies.

Keywords: cerebral palsy, walking activity performance, stride rates

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model provides a unified and standard language for the discussion of assessment, goals and intervention within the field of pediatric disability. (2) The impact of this framework has been seen in a clinical research shift of focus from body function and structure to an increased emphasis on outcomes related to activities (carrying out tasks) and participation (involvement in daily life in a social context). The ICF model proposes reciprocal relationships between all the components, yet there has been limited examination of these relationships with direct measures of the behaviors indicating the activity or participation components. Literature to date has primarily focused on classifications of functional level, clinic, lab or survey-based outcomes of activity or participation versus direct community-based measures such as accelerometers or global positioning devices (GPS).

Within the ICF framework the component of activity is defined as the execution of a task (i.e. walking) or action by an individual(2), while participation is involvement in a life situation. Walking is defined as mobility within the activity component of the ICF. The qualifiers of ‘performance’ and ‘capacity’ allow the activity and participation components to classify the presence or severity of a problem in function at the person level within the ICF. Performance of an activity describes what an individual actually does in his or her ‘lived experience’ or daily life, while capacity describes a person’s ability to do a task in a structured environment (i.e. clinic/lab) and indicates the highest probable level of function. Strides (steps) taken each day is a common descriptor of community walking activity in the public health literature. (3) It is related to intensity and can be employed to describe community-based walking activity by number of strides take taken in ranges of increasing strides rates. (4) Thus, within the ICF framework, measurement of walking in a clinical setting (i.e. six minute walk test) would be a capacity-based measure of walking activity, while walking (strides taken each day) would be performance-based measures of walking activity.

A better understanding of the determinants of day to day participation has potential to inform rehabilitation strategies employed to enhance participation by targeting specific activities and/or impairments. For example, if daily walking (activity performance) improves for a child with cerebral palsy (CP) considering their unique body function/structure, activity capacity, personal and environmental factors, is this then associated with the child walking more often to a friend’s house for a play date (mobility–based participation)?

Children with CP have been described as having some of the most sedentary lifestyles among pediatric disabilities. (5) Van den Berg-Emons et al. (6) reported that school-aged children with spastic diplegia CP were less physically active than a healthy control group and that a child with CP would need to exercise 2.5 hours/day to reach activity levels of peers. Day-to-day walking activity performance via the StepWatch accelerometer has been documented in children with CP ages 10–13 years to be higher in children with higher motor function by Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels. (7, 8) A study of school-based activity performance and participation in Israel documented that children with CP had significantly lower physical activity performance as measured by the School Function Assessment. The children with CP participated significantly less often than their typically developing peers in daily school activities (i.e., playground games and moving to other areas of the school). (9)

What determinants influence overall participation in daily life for children with CP? Children with the diagnosis of CP often exhibit movement disorders and activity limitations. Motor function has been shown to be predictive of restricted participation in mobility, education and social relations. (10) A 2008 systematic review of the determinants of participation in leisure activities for children with CP found the following to be influential: age, gender, activity limitations, family preferences and coping, motivation and environmental resources and supports. (11) Survey based measures of activity performance reported by parents have documented positive relationships between activity performance and day to day social participation. Family activity orientation and motor ability (performance) were documented by Palisano and colleagues in 2011 to be the primary determinants of intensity of participation in leisure and recreation for a sample of 205 children with CP. (12) Specific to participation in mobility-based life habits, a European population-based study in 2009 by Fauconnier and colleagues documented lower mobility participation levels for participants with impairments of walking ability, communication, intellectual ability and pain. (13)

Clearly, the daily life habits of ambulatory children with CP are influenced by activity limitations. Current rehabilitation strategies focus primarily on the enhancement of walking skills in children with CP by addressing impairments of body function/structure and activity capacity (what they can do in structured setting). These strategies are based on the assumption that better activity will positively influence participation in daily life. Thus, to date, the influence of these activity limitations on daily life in the published literature has been measured either by capacity-based (i.e. clinical walking tests, three dimensional gait analyses) or by parental report of what a child does in daily life (performance). (12–15)

Limitations in energy efficiency (body/structure function of ICF) have been documented to be significantly correlated with clinic-assessed measures of activity (capacity-based) but not those tapping community life experiences or participation. (14) Similarly in a botulinum toxin intervention study, measures of activity capacity and parental report of activity performance had moderate to strong associations to measures of participation at baseline. Interestingly, the post intervention change score relationship to participation was only fair for these capacity and performance activity outcomes.(15) A recent analysis documented that the association of walking capacity (clinic-based walking test) to the life habits related to getting around the environment is mediated by their daily walking performance in children with CP ages 2–10 years.(16) These findings suggest that the relationships between ICF components may differ by context and/or direction of association. This work has potential to inform rehabilitation strategies (and outcomes) aimed at enhancing the every day lives of ambulatory children with CP. A better understanding of the relationship of activity performance (what a child actually does in day-today life) to participation in mobility-based life habits in ambulatory children with CP is warranted. Thus, this study examines the direct relationship of daily walking performance (measured via accelerometry) to participation in mobility-based life habits in ambulatory children with CP.

METHOD

Design and Study Sample

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis on data collected within a prospective cohort study, which received prior approval from the human subjects review committee of a regional pediatric specialty care hospital. Participants were approached through targeted mailings from two specialty care pediatric facilities in the Pacific Northwest United States and local therapy providers. Initial mailing lists were generated for children seen at the institutions, having an ICD-9 diagnosis code of CP, and within the age range criteria. This list was further screened prior to mailing to confirm ambulatory status and the use of the English language. Ambulatory children with CP were enrolled who met the inclusion criteria of 1) age 2 to <10 years, 2) GMFCS levels I–III and 3) diagnosis of cerebral palsy. Participants were excluded for: 1) visual impairment limiting physical activity, 2) lower extremity botox injections in the last 3 months, 3) uncontrolled seizure disorder impacting mobility skills and 4) orthopedic or neurosurgery in the last 6 months.

Measures

Measures collected were based on published literature to include covariates that have been documented to negatively influence levels of mobility participation including walking ability, cognition, communication skills and parental report of pain. (12, 13) Consistent with the ICF and documented factors influencing participation in this population, we collected age, gender, race, cognition, communication, body composition, and pain to represent body function/structure. Functional gross motor and communication levels and walking activity represent the activity component of the ICF with parental report of mobility-based participation. Movement disorder and topography were not included in the model, as previous population-based studies have confirmed that these factors (unilateral/bilateral, spastic or not) are not significantly associated with levels of daily participation. (13)

Once informed consent was obtained the demographic information of age, gender, race, communication and functional motor level and cognition were collected by the PI during a single research study visit (See Table I). Functional gross motor level was documented through the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) and communication skills with the Communication Function Classification System (CFCS). (7, 17) Functional motor and communication levels, topography of motor impairment, cognition, and presence of spasticity was collected from the medical records and confirmed by, parent report and/or observation of walking and movement by the PI. Cognition was coded as “normal” or “not” based on parent report of participation in regular early eduction, preschool or education classes and confirmed by documented testing in the medical records.

Table I.

Sample characteristics (n=128)

| Age mean (SD)[range] | 6.2 (2.3) [2.2–9.9] |

|

| |

| Age Group: n (%) | |

| 2–3 years | 24 (19) |

| 4–5 years | 34 (27) |

| 6–7 years | 39 (30) |

| 8–9 years | 31 (24) |

|

| |

| Gender-Male, n (%) | 76 (59) |

|

| |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 105 (82) |

|

| |

| Spasticity, n (%) | 91 (72) |

|

| |

| Topography of CP, n (%) | |

| Diplegia | 46 (36) |

| Hemiplegia | 63 (49) |

| Quadriplegia | 12 (9) |

| Triplegia | 6 (5) |

| Monoplegia | 1 (1) |

|

| |

| Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) n (%) | |

| Level I | 44 (35) |

| Level II | 54 (42) |

| Level III | 30 (23) |

|

| |

| Cognition, Normal, n (%) | 115 (90) |

|

| |

| Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) n (%) | |

| Level I | 73 (57) |

| Level II | 25 (20) |

| Level III | 18 (14) |

| Level IV | 12 (9) |

|

| |

| Pain-Parent report problem with physical function in last month due to having hurts or aches’ (PedsQL) | |

| Never | 22 (17) |

| Almost Never | 44 (34) |

| Sometimes | 45 (35) |

| Often | 11 (9) |

| Almost Always | 6 (5) |

|

| |

| Height Adjusted Lean Mass(HALM), Mean (SD)[range]** | |

| Level I | 45 (7.3) [35.2. 63.4] |

| Level II | 46.5 (5.6) [34.9, 67.9] |

| Level III | 42.0 (5.4) [33.9, 57.5] |

|

| |

| Average accuracy of StepWatch Calibration, Average [range] | 0.99 [0.91–1.07] |

ANOVA,

p <.006;

Body composition was collected to represent physical health within the body function/structure component of the ICF and due to significant differences documented by GMFCS level in this study sample (p = .006, See Table I &II). The PI measured weight, triceps and subscapular skinfolds, tibial length, and knee height using standardized methods appropriate for children with CP.(18–20) Height Adjusted Lean Mass (HALM) was calculated as (100 minus percent body fat × weight) divided by knee segment height and expressed as kilograms per cm. Percent body fat was determined from triceps and subscapular skin fold thicknesses employing the appropriate corrections for CP.(21) Pain was assessed by parent report of how much of a problem pain was in the last month for physical function (Pediatric Quality of Life –PedsQL question). (22)

Table II.

Summary of average strides/day, average number of strides at > 30 stride/min rate per day height adjusted lean mass (HALM) by Gross Motor Function Classification System levels (GMFCS).

| GMFCS Level | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level I | Level II | Level III | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Average strides/day** | 6691 | 2123 | 5407## | 2061 | 1970##, ### | 1475 |

| Average number of strides at > 30 stride/min rate per day** | 3097 | 1559 | 2444# | 1265 | 506##, ### | 565 |

| Height adjusted lean mass (HALM)** | 45.4 | 7.3 | 46.5# | 5.6 | 42.0#, ### | 5.4 |

ANOVA,

p < or = .006;

t-test: compared to GMFCS level I,

p <.02,

p< .001, Level II to III,

p <.002

Parents completed the Assessment of Life Habits for Children questionnaire (Life-H, Versions 0–4 years or 5–13 years, as appropriate for age of their child) to sample participation in daily life. (23) The Life-H was developed from the Disability Creation Process (DCP) model. The DCP model proposes an interaction of risk, personal and environmental factors with life habits to describe the social participation and/or handicapping experience of a person. In this model, risk factors represent the cause of the disease, trauma or disruption of develop in a person. Personal factors are the organic systems interacting with persons capabilities. Within the ICF model, this would be the body/function/structure component interacting with the activity component (capability/performance). The environmental factors of the DCP model are considered any facilitator or obstacle in their environment whether physical, cultural and/or attitudinal. This would be consistent with the ICF’s environmental component. Life habits within the DCP model is the social participation and/or handicapping situation resulting from the interaction of risk, personal and environmental factors and is comparable to the participation component of the ICF. Overall, the DCP model suggests that measurement of accomplishment of life habits is part of examining the interaction between a person and their environment, which subsequently takes the responsibility for the handicapping experience off of the person. Thus, accomplishment of life habits may be enhanced by compensation for disabilities and limitations in capabilities through rehabilitation. Similarly, strategies to reduce obstacles on the social, physical and/or resource level are identified. In comparison, the ICF model is employed to classify/examine a person’s health status (i.e. spastic diplegia) through the interaction of five key components.

The questionnaire was designed and validated to assess the social participation of children with disabilities. (24) Each Life-H item is ranked on a 0–9 scale for accomplishment, where a score of 0 represents ‘not accomplished’ and a score of 9 equals ‘no difficulty and no assistance.’ A weighted score for each Life-H category was derived from the number of applicable habits items and the raw scores according to Life-H scoring instructions. The specific Life-H category scores of personal care, housing, mobility and recreation were examined due to their specific focus on walking and upright mobility. Personal care, for example, addresses toileting at home and in the community, while the housing category samples the ability to move around the home, backyard and garden and mobility measures moving on uneven surfaces, streets and pavement. The recreation category samples participation in outdoor games, sports and cultural and tourist events.

Walking activity performance within the context of daily life was measured with the StepWatch device. (25) The StepWatch is a two-dimensional accelerometer, designed to measure when the heel leaves the ground. The pager sized device was calibrated through settings of sensitivity and cadence for the individual walking pattern of the participant per instructions of the device developers. Calibration accuracy was confirmed by visual observation during a 100+ stride walking trial wearing the StepWatch. Strides were manually counted with a hand held counter and compared to the StepWatch count of strides taken as a ratio of agreement and averaged (See Table I). Accuracy to manual counts and comparison to other pedometers has confirmed the accuracy and precision of the StepWatch for detecting strides taken. (26–28) Participants wore the StepWatch on their lateral left ankle (inside a knit cuff) for 7 days. Instructions were to wear the StepWatch during all waking hours (except bathing/swimming). The device was returned to the investigators by postage paid mail.

Each day of monitoring was reviewed and noncompliance was defined as days that had more than 3 hours of inadequate monitoring (i.e., monitor upside down) or unexplained lack of stride counts (i.e., swimming/bathing) during waking hours (6:00 AM–10:00 PM). Five days of stride activity data (4 weekdays and 1 weekend day) were obtained for all participants. Only walking activity during waking hours was examined. (29, 30) Stride activity was summarized through the variables of average total strides/day and number of strides at > 30 strides/min rate per day. Average total strides/day from a five day sample represents a metric of overall daily walking activity across functional walking levels. This summary variable is also consistent with the CDC pediatric walking activity guidelines for optimal health benefits.(31)

Strides (steps) taken per minute (or cadence) is a common temporal-spatial parameter of gait. It is related to intensity and can be employed to describe patterns of community-based walking activity by tracking average number of strides taken in ranges of increasing strides rates (4). Stride rates (number of strides taken each minute) from a recent sample of 209 children with CP and 386 typically developing youth (TDY) ages 2–14 years ranged from 1 to ~ 100 strides/min. (16) Per StepWatch accelerometry, the TDY sample walked on average a similar number of strides/day in low (1–30 strides/min) and moderate (31–60 strides/min) stride rates. In contrast, children with CP averaged a significantly lower number of strides in the moderate stride rate as compared to the low rate. Thus, in order to explore development of potential walking intensity interventions, the average number of strides at > 30 strides/min was examined as a metric of walking performance at medium to high intensity. The cutoff of 30 was chosen based on our a priori experience with StepWatch data that number of strides start decline sharply for children with CP at GMFCS level 3. (16)

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics were summarized by descriptive statistics as appropriate for variable type. Preliminary pairwise correlations with this study sample, between average total strides/day and GMFCS documented a significant negative correlation (Spearman r =−0.62, p<.001). Previous literature has confirmed that higher GMFCS levels (more motor limitations) are significantly associated with decreased strides/day and stride rates. Thus, GMFCS was not included in the models due to high correlations with walking stride activity. (8, 16, 30) Across GMFCS level differences for the walking performance measures and HALM were examined by an ANOVA with comparison between GMFCS groups by t-tests. The main analyses examining the association between walking activity performance and mobility-based life habits were based on multivariable linear regression models. Regression models were developed a priori based on published literature to include covariates that have been shown or suggested to influence levels of mobility participation. (12, 13) Separate regression models predicting each of the mobility-based Life-H categories were developed for the predictors of interest average strides/day and number of strides at >30 stride/min rate per day. The walking performance variables were scaled to allow ease of interpretation of the regression coefficients (i.e. average total strides/day divided by 1000). A common set of covariates were used in all regressions regardless of their significance. They included age (continuous), gender (male), CFCS level (I to IV) and pain limiting function in the last month (5 levels from never to almost always). Age was included in the model due to the wide age range studied and the delay of onset of walking in this population. Gender was included due to the reported male to female prevalence ratio for CP of 1.2:1 reported in recent US data. (32) All p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

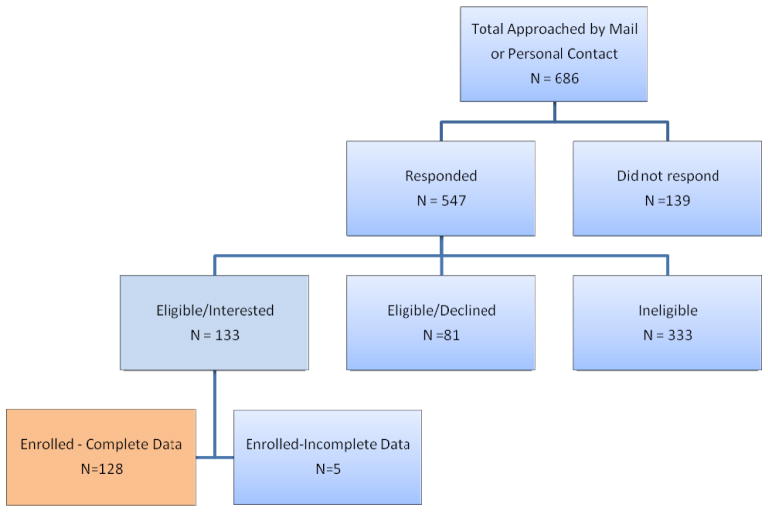

A total of 686 children and families were initially approached in person or by directed mailings (see Fig. 1). Of the 547 who responded, 133 were enrolled. Five participants did not complete data collection (four monitors unreturned) for a total of 128 completing the study. To insure distribution by age, the enrollment goal was 30 or more participants per age group across four 2-year age groups (See Table I). Sample size by age group ranged from 24 (2–3 years) to 39 (6–7 years). The participant’s average age was 6.2 (range 2.2, 9.9) years. The sample was predominately male (59%), Caucasian (82%), had hemiplegia (49%) with spasticity as the primary movement disorder (72%). GMFCS levels I, II and III were represented by 44, 54 and 30 children respectively. Cognitively, 90% of the sample was coded as normal. Participants were primarily functioning at CFCS levels I or II (77%) and approximately half the sample (51%) reported “hurts or aches” never or almost never a problem with physical function in the last month. Ratio of agreement between manual counts and the StepWatch during calibration walking trials was acceptable and averaged 0.99 (range 0.91–1.07). (26)

Figure 1.

Summary of recruitment of participants. Flow chart of recruitment efforts to enroll the study cohort of 128 participants.

The walking performance measures by GMFCS level are displayed in Table II. Both average stride/day and average number of strides >30 stride/min decreased as motor function decreased (GMFCS level higher). GMFCS levels II and III were significantly lower (p = .02 to .001) than level I with level III lower than level II for both walking measures (p = .002). HALM was significantly different across GMFCS levels (p =.006, See Table I & II). Only GMFCS level III was significantly lower than level I and II (p = .022 and .002 respectively, Table II).

The regression analysis examining the association of walking performance as measured by average strides/day to Life-H mobility based participation categories is summarized in Table III. Average strides/day was positively associated with Personal Care, Housing, Mobility and Recreation Life-H categories (β =.34 to .41, p < .001). These models explained 30–35% of the variance in mobility-based life habits. After accounting for the covariates, average strides/day explained an additional 7–12% of the variance. Gender was only associated with the Personal Care category (β =−1.4, p =.005). Males reported lower levels of participation in Personal Care than females. Communication was negatively associated with participation in all mobility-based Life-H categories (β = −.54 to 1.2, p < .002). Lower communication skills had the greatest association (β = −1.2, p = <.001) with the Recreation category. Age, normal cognition, problems with hurts or aches in the last month and body composition (HALM) was not significantly associated with accomplishment of mobility-based life habits.

Table III.

Multivariable linear Regression analysis of the relationship of average strides/day to Life Habits (Life-H) categories of Personal Care, Housing, Mobility, and Recreation, controlling for gender, age, cognition, communication, pain and body composition (n=128).

| Mobility-based Life-H Categories | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Care | Housing | Mobility | Recreation | |||||

| β (CI) | P values | β (CI) | P values | β (CI) | P values | β (CI) | P values | |

| Predictors | ||||||||

| Average Strides/day **(Average total strides per day/1000) |

.40 (.22, .58) | <.001 | .34 (.17, .52) | <.001 | .41 (.23, .59) | <.001 | .35 (.15, .54) | .001 |

| Gender- Male | −1.4 (−2.4, −.45) | .005 | −.34 (−1.3, .59) | .48 | −.86 (−1.8, .11) | .08 | −.43 (−1.5, .61) | .42 |

| Age | .14 (−.10, .36) | .25 | .07 (−.15, .29) | .51 | −.15 (−.38, .08) | .20 | −.07 (−.32, 18) | .59 |

| Cognition -Normal | −.85 (−2.3,.62) | .25 | .47 (−.93, 1.9) | .51 | .53 (−.93, 2.0)) | .47 | −.03 (−1.6, 1.5) | .98 |

| Communication Function Classification System CFCS | −1.0 (−1.5,−.54) | <.001 | −.68 (−1.1, −.25) | .002 | −.54 (−1.0, −.09) | .02 | −1.2 (−1.7, −.67) | <.001 |

| Pain-Problem with hurts or aches in last month | .00 (−.42, .43) | 1.0 | −.35 (−.75, .06) | .09 | −.33 (−.75, .09) | .12 | −.37 (−.82, .09) | .11 |

| Body Composition Height Adjusted Lean Mass (HALM) |

.63 (−.54, 1.8) | .29 | .14 (−.97, 1.3) | .80 | .76 (−.39, 1.9) | .19 | −.45 (−1.7, .79) | .47 |

| Constant | 5.4 (2.7, 8.1) | 6.4 (3.8, 8.9) | 6.6 (3.9, 9.3) | 7.6 (4.7, 10.5) | ||||

| Partial Correlation (R2) | .35 | .30 | .30 | .35 | ||||

β = B weights on the original scale.

Average strides/day has been rescaled to 1 unit = 1000 strides/day. A β of .40 translates to 2.5 units (2500 strides/day) increase in average stride rate is associated with 1 unit improvement in Life-H Personal care score.

Partial Correlation R2 = variance explained by the full model.

Table IV displays the results of the regression models exploring the relationship of walking performance as measured by average number of strides at > 30 stride/min rate per day to Life-H mobility-based participation categories. This walking intensity performance variable was positively associated with all four Life-H categories (β = .54 – .60, p < .001). The full models explained 29 – 37% of the variance in mobility-based life habits examined. Average number of strides at > 30 strides/min per day explained an additional 4 – 12% of the variance after accounting for the covariates. Being male was negatively associated with Personal care life (β = −1.4, p = <.001). Lower communication skills was significantly associated with lower performance of all mobility based life habits (β = −.57 to −1.1, p <.02). Ages, normal cognition, parental report of pain and body composition were not associated with participation in mobility-based life habits.

Table IV.

Multivariable linear regression analysis of the relationship of average number of strides at > 30 stride/min per day to Life Habits (Life-H) categories of Personal Care, Housing, Mobility, and Recreation, controlling for gender, age, cognition, communication, pain and body composition (n=128).

| Mobility-based Life-H Categories | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Personal Care | Housing | Mobility | Recreation | |||||

| β (CI) | P values | β (CI) | P values | β (CI) | P values | β (CI) | P values | |

| Predictors | ||||||||

| Average number of strides > 30 stride/min/day **(number strides > 30 stride/min per day/1000) | .60 (.30, .90) | <.001 | .54 (.26,.82) | <.001 | .66 (.36, .95) | <.001 | .64 (.33, .95) | .001 |

| Gender- Male | −1.4 (−2.4, −.36) | .007 | −.32 (−1.3, .61) | .50 | −.87 (−1.9, .10) | .08 | −.52 (−1.6, .50) | .31 |

| Age | .13 (−.11, .36) | .46 | .07 (−.15, .29) | .56 | −.16 (−.38, .07) | .17 | −.08 (−.32, 17) | .54 |

| Cognition -Normal | −.84 (−2.3,.65) | .27 | .46 (−.94, 1.9) | .52 | .50 (−1.0, 2.0) | .50 | −.11 (−1.6, 1.4) | .88 |

| Communication Function Classification System CFCS | −1.0 (−1.5,−.58) | <.001 | −.71 (−1.2, −.28) | .002 | −.57 (−1.0, −.11) | .02 | −1.1 (−1.6, −.67) | <.001 |

| Pain-Problem with hurts or aches in last month | −.04 (−.47, .39) | .85 | −.38 (−.78, .03) | .07 | −.36 (−.78, .06) | .09 | −.37 (−.82, .07) | .10 |

| Body Composition-Height Adjusted Lean Mass (HALM) | . 46 (−.70, 1.6) | .43 | .02 (−1.1, 1.1) | 1.0 | .65 (−.50, 1.8) | .26 | −.47 (−1.7, .74) | .45 |

| Constant | .60 (3.6, 8.9) | 7.0 (4.5,9.5) | 7.4 (3.9, 10.0) | 8.1 (5.3, 10.8) | ||||

| Partial Correlation (R2) | .33 | .29 | .29 | .37 | ||||

β = B weights on the original scale.

Average number strides > 30 stride/min per day has been rescaled to 1 unit=1000 strides/day. A β of .60 means one unit (1000 strides) increase in average number of strides at >30 strides/min rate is associated with 0.6 unit increase in Life-H Personal Care score, or 1667 more strides is associated with one unit increase in Life-H Personal Care score.

Partial Correlation (R2) = variance explained by the full model.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first paper to examine day-to-day walking activity performance (accelerometry-based stride counts) relative to accomplishment of mobility-based life habits. Previous work has examined measures of activity capacity or functional walking levels (i.e. GMFCS, 6 minute walk test, 10 meter walk test) relative to accomplishment of life habits or participation. (13, 23, 33, 34) Our findings are consistent with the work of Lepage and colleagues, (34) who documented a negative association of locomotor limitations on the accomplishment of life habits in 96 children with CP across GMFCS all levels and ages 5 – 17.8 years. They documented lower participation in life habits for children using assistive mobility devices for walking as compared to independent walkers for Life-H total scores and the categories of housing, mobility, community and recreation. This current study expands the work of Lapage et al by examining the association of community-based walking performance levels (i.e. average strides/day) within ambulatory children with CP to participation in mobility-based life habits. The results of this study are also consistent with the work of Fauconnier and colleagues, (13) who documented the association of decreasing participation in the life habits related to mobility and recreation as walking skill decreased (GMFCS) in a large cross-sectional European sample of ambulatory children in 2009.

The variance explained by the regression models presented are similar to previous work exploring the determinants of intensity of participation and recreation.(12) It should be noted that the models examined in this study explained only 29 to 37% of the total variance in mobility-based participation. Proportionally, accelerometry-based walking activity explained 4–12% of this variance supporting the inclusion of walking activity performance as a factor in the relationship. The unexplained total variance of the models suggests that other factors should be considered as well in examination of this unidirectional relationship.

Within the ICF, this unexplained variance maybe physical, social and/or attitudinal environmental factors as well as other personal or body function/structure factors which were not measured in this study. Physical environment factors such as rural/urban setting, presence of sidewalks or parks, geography of local neighborhood and/or type of housing should be examined. Social factors including family makeup, physical activity level of family, socioeconomic status and/or parental education may be influencing the relationships. School/community/family attitudes towards physical activity and/or inclusion of children with motor limitations may also explain a portion of the unidirectional relationship of walking activity performance to participation in mobility-based life habits for children with CP. Personal factors not addressed in this model may include personality as well as interest in physical activity. This study only tests the direction of association of activity to participation within the ICF. The directionality of the relationship is unknown, as levels of participation in mobility-based life habits may influence levels of activity performance.

Yet within the context of this study and taking into account factors known to influence participation in children with CP, the results suggest that walking activity performance (average strides/day and number of strides > 30 strides/min per day) is significantly associated with the accomplishment of life habits related to the mobility-based life habits of personal care, housing, mobility and recreation. Significant positive relationships between activity performance (Activity Scale for Kids) and the intensity of active physical and social activities (Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment) have been reported. (35) These results are also in harmony with the work of Olin and colleagues who reported higher intensity of participation in home, extracurricular and community activities for children with CP walking with the least restrictions. (36) Similarly, Palisano and coauthors reported that motor ability was a primary determinant of intensity of participation in leisure and recreation across functional levels in children with CP. (12) All of these previous studies documented activity performance through recall questionnaires versus monitoring of the activity (walking) within daily life as carried out in this study.

Of note, pain was not a significant factor associated with mobility-based participation in this sample, which is in contrast to previous population-based work with the Life-H outcome measure across all functional levels (GMFCS). (13) Fauconnier and colleagues queried pain relative to level and frequency (two separate questions from the Child Health Questionnaire relative to intensity and frequency) within the past week. The differing results may be a function of how pain was measured (a single question from the PedsQL) or that pain may be more of an issue for children with lower gross motors skills (non-ambulatory) children. This work documented that males reported lower levels of accomplishment of life habits related to personal care. In contrast, Palisano and colleagues documented lower intensity of participation in leisure and recreation for males. (12) The lower levels of participation documented for male participants in differing life habit categories between previous work and this project may be a function of differing measures of participation.

The results suggest that mobility-based participation levels are associated with walking activity performance. Based on the regression model (Table III), an increase of approximately 2439 to 2941 average strides/day has potential to be associated with a one unit increase in Life-H scores. Similarly, an increase of 1515 to 1852 strides > 30 strides/min/day (Table IV) would potentially be associated with one unit increase in Life-H scores. Based on the Life-H scoring, a positive change of one unit or point could potentially represent a range of change in accomplishment of specific life habits from with difficulty using an assistive device to with difficulty and human assistance up to a change from no difficulty and an assistive device/adaptation to completion of the habit with no difficulty without an assistive device/adaptation.

Walking activity and daily life habits, by virtue of being queried, observed and/or quantified with in this study may have been influenced or modified (i.e. Hawthorne effect). This potential confounding is limited due to the use of an accelerometer worn on the ankle, thus decreasing the potential influence of being ‘watched’ by a human data collector. This population commonly wears orthotics, thus the addition of the device worn outside their orthotics was predominately unnoticed per parent report after initial donning. Participation was queried through parent-report of the ‘usual’ way their child carries out common activities of daily life, thus participants themselves were unaware of the specific habits queried and/or the context.

Study Limitations

Limitations should be noted in the interpretation of these results. First, this was a cross-sectional design and thus causal relationships cannot be assumed. Second, this was a convenience sample from one geographical area in the United States and may not generalize. We did not achieve the enrollment goal of 30 participants for all age groups, thus the 2–3 years olds maybe under represented relative to the full sample. Replication with a larger sample size and wider age range is needed to confirm the relationships documented. Third, our sample was predominately participants with hemiplegia, which could bias associations towards youth with higher walking performance. The Life-H was measured by parental report only, which may have introduced bias due to differing reports of the children’s day-to-day accomplishments of life habits. Pain was assessed via a single question from the PedsQL. Such methods may not adequately quantify the influence of pain relative daily mobility in this ambulatory population and should be interpreted with caution.

CONCLUSIONS

This examination of a unidirectional relationship within the ICF expands our understanding of the directionality of the interactions among all components and is consistent with the social model of disability. (37) The relationships documented in this project suggest the need for future exploration of the bidirectional conceptual relationships of the ICF. We do not know if increasing walking performance will enhance mobility-based participation or whether increasing mobility-based participation increase walking performance.

These findings suggest the need to specifically test whether interventions that focus on enhancing daily stride levels and average number of strides each day at rates > 30 strides/min enhance levels of accomplishment of mobility-based life habits. For example, over-ground or treadmill burst training is a potential rehabilitation strategy to be examined. Likewise in reverse, interventions to enhance mobility-based life habits should be explored for their influence on walking activity performance with potential physical health benefits. Such strategies maybe implemented through individualized family strategies, community resources, state and/or national initiatives. Optimizing the levels of activity performance and participation in day to day life for children with CP lays the foundation for healthy and active lifestyles in adulthood. The relative influence and bidirectional interaction of all the ICF components (i.e., personal factors, body structure/function, activity and environment) on life habits or participation requires further clarification to inform and optimize clinical management.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by funding from NIH K23 HD060764 and by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant UL1RR025014. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

List of abbreviations

- ICF

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

- CP

Cerebral Palsy

- CFCS

Communication Function Classification System

- GMFCS

Gross Motor Function Classification System

- LIFE-H

Assessment of Life Habits

- TDY

Typically developing youth

- HALM

Height adjusted lean mass

Footnotes

Presentations

Pisa, Italy, International Cerebral Palsy Conference, Oct 10, 2012

American Physical Therapy Association, Combined Sections Meeting, San Diego, Jan 22, 2013

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01217242

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERNCES

- 1.Bjornson K, Zhou C, Stevenson RD, Christakis D. Capacity to Participation in Cerebral Palsy: Evidence of an Indirect Path via Performance. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2013.06.020. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Geneva: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tudor-Locke C, Craig C, Beets M, Belton S, Cardon G, Duncan S, Hatano Y, Lubans D, Olds T, Raustorp A, Rowe D, Spence J, Tanaka S, Blair S. How many steps/day are enough? for children and adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2011;8(1):78. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barreira TV, Katzmarzyk PT, Johnson WD, Tudor-Locke C. Cadence Patterns and Peak Cadence in US Children and Adolescents: NHANES, 2005–2006. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2012;44(9):1721–7. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318254f2a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longmuir PE, Bar-Or O. Factors influencing the physical activity levels of yourth with physical and sensory disabilities. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 2000;17(1):40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.van den Berg-Emons HJ, Saris WH, Westerterp KR, Huson, van Baak MA. Daily physical activity of school children with spastic diplegia and of healthy control subjects. Journal of Pediatrics. 1995;127(4):578–84. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Bartlett D, Livingston MH. GMFCS-R & E Gross Motor Function Classification System Expanded and Revised: CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability. McMasters University; Hamilton, ON: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bjornson KF, Belza B, Kartin D, Logsdon R, McLaughlin JF. Ambulatory Physical Activity Performance in Youth With Cerebral Palsy and Youth Who Are Developing Typically. Physical Therapy. 2007;87(3):248–57. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schenker R, Coster W, Parush S. Participation and activity performance of students with cerebral palsy within the school environment. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2005;27(10):539–52. doi: 10.1080/09638280400018437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beckung E, Hagberg G. Neuroimpairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2002;44(5):309–16. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shikako-Thomas K, Majnemer A, Law M, Lach L. Determinants of Participation in Leisure Activities in Children and Youth with Cerebral Palsy: Systematic Review. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2008;28(2):155–69. doi: 10.1080/01942630802031834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palisano RJ, Orlin M, Chiarello LA, Oeffinger D, Polansky M, Maggs J, Gorton G, Bagley A, Tylkowski C, Vogel L, Abel M, Stevenson R. Determinants of Intensity of Participation in Leisure and Recreational Activities by Youth With Cerebral Palsy. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2011;92(9):1468–76. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fauconnier J, Dickinson HO, Beckung E, Marcelli M, McManus V, Michelsen SI, Parkes J, Parkinson KN, Thyen U, Arnaud C, Colver A. Participation in life situations of 8–12 year old children with cerebral palsy: cross sectional European study. British Medical Journal. 2009:338. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerr C, Parkes J, Stevenson M, Cosgrove AP, McDowell BC. Energy efficiency in gait, activity, participation, and health status in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2008;50(3):204–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright FV, Rosenbaum PL, Goldsmith CH, Law M, Fehlings D. How do changes in body functions and structures, activity and participation relate in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2008;50:283–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.02037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bjornson K, Zhou C, Stevenson RD, Christakis D, Song K. Walking activity patterns in youth with cerebral palsy and youth developing typically. Disability & Rehabilitation. 2013 doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.845254. In Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hidecker MJC, Paneth N, Rosenbaum PL, Kent RD, Lillie J, Eulenberg JB, Chester JK, Johnson B, Michalsen L, Evatt M, Taylor K. Developing and validating the Communication Function Classification System for individuals with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2011;53(8):704–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03996.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spender QW, Cronk CE, Charney EB. Assessment of linear growth of children in cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1989;31:206–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1989.tb03980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevenson R, Conaway M, Chumlea C, Rosenbaum P, Fung E, Henderson R, Worley G, Liptak G, O’Donnell M, Samson-Fang L. Growth and health in children with moderate-to-severe cerebral palsy. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1010–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevenson R. Measurement of Growth in Children with Developmental Disabilities. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1996;38:855–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1996.tb15121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gurka MJ, Kuperminc MN, Busby MG, Bennis JA, Grossberg RI, Houlihan CM, Stevenson RD, Henderson RC. Assessment and correction of skinfold thickness equations in estimating body fat in children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2010;52(2):e35–e41. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03474.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varni JW. PedsQL 4.0: Measurement model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003. Available from: http://www.pedsql.org/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Lepage C, Noreau L, Bernard P-M, Fougeyrollas P. Profile of handicap situations in children with cereral palsy. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1998;30(4):263–72. doi: 10.1080/003655098444011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noreau L, Lepage C, Boissiere L, Picard R, Fougeyrollas P, Mathieu J, Desmarais G, Nadeau L. Measuring participation in children with disabilities using the Assessment of Life Habits. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007;49(9):666–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.StepWatch-OrthocareInnovations. 2008 Available from: http://www.orthocareninnovations.com.

- 26.Bjornson KF, Yung D, Jacques K, Burr R, Christakis D. StepWatch-based stride counting: Accuracy, precision, and prediction of energy expenditure in children. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011;5:7–14. doi: 10.3233/PRM-2011-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster RC, Lanningham-Foster LM, Manohar C, McCrady SK, Nysse LJ, Kaufman KR, Padgett DJ, Levine JA. Precision and accuracy of ankle-worn acclerometer-based pedometer in step counting and energy expenditure. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41:778–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitre N, Lanningham-Foster L, Foster R, Levine JA. Pedometer Accuracy in Children: Can We Recommend Them for Our Obese Population? Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):e127–e31. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bjornson KF, Song KM, Lisle J, Robinson S, Killen E, Barrett T, Zhou C. Measurement of Walking Activity throughout Childhood: Influence of Leg Length. Pediatrics Exercise Science. 2010;22:581–95. doi: 10.1123/pes.22.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjornson KF, Song K, Zhou C, Coleman K, Myaing M, Robinson SL. Walking stride rate patterns in children and youth. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2011;23(4):354–63. doi: 10.1097/PEP.0b013e3182352201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: Fact Sheet for Professionals. 2012 Available from: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/factsheetprof.aspx.

- 32.Kirby RS, Wingate MS, Van Naarden Braun K, Doernberg NS, Arneson CL, Benedict RE, Mulvihill B, Durkin MS, Fitzgerald RT, Maenner MJ, Patz JA, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Prevalence and functioning of children with cerebral palsy in four areas of the United States in 2006: A report from the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2011;32(2):462–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kerr C, McDowell B, McDonough S. The relationship between gross motor function and participation restriction in children with cerebral palsy: an exploratory analysis. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2007;33(1):22–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lepage C, Noreau L, Bernard P-M. Association Between Characteristics of Locomotion and Accomplishment of Life Habits in Children With Cerebral Palsy. Physical Therapy. 1998 May 1;78(5):458–69. doi: 10.1093/ptj/78.5.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.King GA, Law M, King S, Hurley P, Hanna S, Kertoy M, Rosenbaum P. Measuring children’s participation in recreation and leisure activities: construct validation of the CAPE and PAC. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2007;33(1):28–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Orlin MN, Palisano RJ, Chiarello LA, Kang LJ, Polansky M, Almasri N, Maggs J. Participation in home, extracurricular, and community activities among children and young people with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2010;52(2):160–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colver A, Thyen U, Arnaud C, Beckung E, Fauconnier J, Marcelli M, McManus V, Michelsen SI, Parkes J, Parkinson K, Dickinson HO. Association Between Participation in Life Situations of Children With Cerebral Palsy and Their Physical, Social, and Attitudinal Environment: A Cross-Sectional Multicenter European Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012;93(12):2154–64. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]