Abstract

Objective

To evaluate published evidence about health literacy and cancer screening.

Methods

Seven databases were searched for English language articles measuring health literacy and cancer screening published in 1990-2011. Articles meeting inclusion criteria were independently reviewed by two investigators using a standardized data abstraction form. Abstracts (n=932) were reviewed and full text retrieved for 83 articles. Ten articles with 14 comparisons of health literacy and cancer screening according to recommended medical guidelines were included in the analysis.

Results

Most articles measured health literacy using the S-TOFHLA instrument and documented cancer screening by self-report. There is a trend for an association of inadequate health literacy and lower cancer screening rates, however, the evidence is mixed and limited by study design and measurement issues.

Conclusion

A patient's health literacy may be a contributing factor to being within recommended cancer screening guidelines.

Practice Implications

Future research should: be conducted using validated health literacy instruments; describe the population included in the study; document cancer screening test completion according to recommended guidelines; verify the completion of cancer screening tests by medical record review; adjust for confounding factors; and report effect size of the association of health literacy and cancer screening.

Keywords: Health Literacy, Cancer Screening, Cancer

1. Introduction

Cancer mortality rates have decreased during the past decades, however, cancer remains a significant cause of mortality in the United States (U.S.) [1]. Factors contributing to the decrease in cancer mortality rates include increases in cancer screening rates, appropriate abnormal screening test follow-up, and treatment advances. Certain populations, mainly minority and low socioeconomic status (SES) groups, have not benefited equally from cancer screening and continue to have elevated cancer mortality rates [2]. Inadequate health literacy may be a reason for the lack of awareness and/or knowledge about the importance of completing cancer screening tests within U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended intervals, and may be a contributing factor to cancer screening disparities [3].

Health literacy is defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions [4]. Due to the multiple skill domains required to obtain health information and receive appropriate health services, health literacy is conceptualized as the intersection of education, culture, experience, setting, and other factors [4]. A framework for health literacy may consist of multiple components including cultural and conceptual knowledge, print literacy (ability to read, write, and understand text), numeracy (capability to complete numerical tasks), oral literacy (listening, speaking, communication), and media literacy (ability to access and evaluate media information including ehealth) within a health context [4,5]. Each component of health literacy or combination of components may influence an individual's ability to make a decision about completing a cancer screening test.

Understanding the potential benefits, harms, alternatives, and uncertainties associated with undergoing a recommended cancer screening test is important when making a cancer screening decision. To better understand the role that health literacy may play in health decisions, including cancer screening, instruments to measure health literacy have been developed in the past few decades. Health literacy measurement is challenging, however, because it encompasses knowledge, multiple skills, previous personal experiences, setting, and context [4].

Instruments with accumulated evidence of validity and reliability measuring different relevant components of health literacy needed to navigate the health care system exist and have been used in research focused on a variety of health issues [4, 6]. The National Center for Education Statistics’ National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL) assesses prose, document, and quantitative literacy in the health context [7]. The Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) tests word recognition and pronunciation [8, 9]. The Test Of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA) is a reading comprehension test which includes numeracy [10, 11]. Additional instruments include the Newest Vital Sign which measures reading and quantitative skills [12], and a three item and single item screener of health literacy [13-15]. More recently, the health literacy skills instrument has been developed and measures skills associated with reading and understanding text, locating and interpreting information in documents, numeracy, oral literacy, and the ability to seek information via the Internet (navigation) [16]. Some health literacy instruments are available in shorter versions to decrease participant burden [9, 10, 17], and some instruments have been validated in other languages [11, 12].

A systematic review of health literacy found that inadequate health literacy is associated with less health knowledge, poor health status, and improper use of health services [18]. Although previous research suggests that inadequate health literacy may contribute to lower cancer screening rates, to our knowledge there has not been a comprehensive review of this topic. If inadequate health literacy contributes to lower cancer screening rates, the development of materials and interventions aimed at low literacy populations is vital to improving cancer screening rates, and ultimately reducing cancer disparities. This systematic review synthesizes the evidence about health literacy and cancer screening and suggests direction for future research.

2. Methods

2.1 Identification of relevant studies

In January 2012, a comprehensive search of PUBMED, CINAHL, PSYCINFO, Social Science Citation Index, Comabstracts, ERIC, and LISTA was conducted to identify English language articles that included health literacy and cancer screening. Since health literacy instruments with strong psychometric properties were not available until the 1990s; the search was from January 1990 through December 2011. Articles were individually identified by searching the terms health literacy and literacy with the following key search terms: cancer, cancer screening, colon cancer screening, colorectal cancer screening, fecal occult blood test (FOBT), flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, breast cancer screening, mammography, cervical cancer screening, Pap, prostate cancer screening, and prostate specific antigen (PSA).

Resulting abstracts were reviewed for a measure of health literacy and cancer screening. Articles focused on cancer survivors were excluded to ensure the review focused on the early detection of cancer and not the detection of cancer recurrence or a second cancer. Articles identified as literature reviews, editorials, summaries, abstracts, dissertations, or critiques were excluded resulting in the inclusion of only peer-reviewed empirical research. The full text of articles lacking an abstract with sufficient information to determine study inclusion were reviewed using the previously stated criteria.

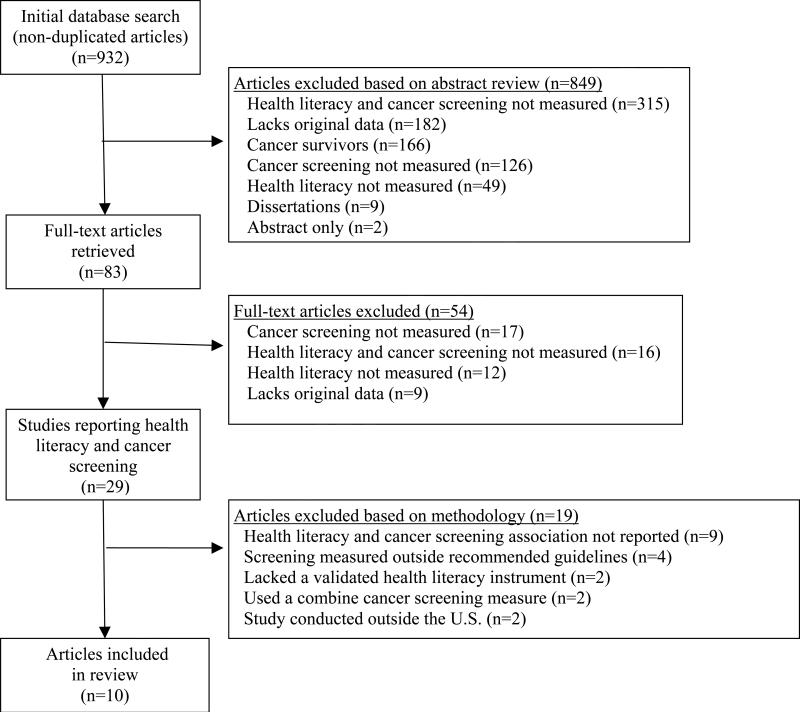

After removal of duplicates, the abstracts of 932 articles were reviewed (Figure 1). Articles (n=849) were excluded because they: lacked measures of both health literacy and cancer screening behavior (n=315); did not include original data (n=182); focused on cancer survivors (n=166); failed to report cancer screening behavior (n=126); lacked a measure of health literacy (n=49); were dissertations (n=9); or were meeting abstracts (n=2). The remaining 83 articles were reviewed for study inclusion. An additional 54 articles were excluded because they: lacked information about cancer screening behavior (n=17); failed to measure both health literacy and cancer screening behavior (n=16); failed to measure health literacy (n=12); or did not include original data (n=9).

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram.

2.2 Data extraction

The articles (n=29) meeting inclusion criteria were independently reviewed by two investigators using a standardized data abstraction form to document the: 1) first author; 2) journal; 3) publication date; 4) sample size and characteristics (including geographic location); 5) study design; 6) health literacy instrument and proportion of participants with inadequate health literacy; 7) cancer type; 8) cancer screening test; 9) determination of screening status and screening proportion (participants screened during time interval defined within the study); 10) study setting; and 11) the association between health literacy and cancer screening (effect size estimate and direction). The investigators resolved any discrepancies through discussion and differences were resolved through consensus.

To be able to compare results across studies, the quality of methodology was assessed for each study. Additional articles (n=19) were excluded because they: failed to report on the association between health literacy and cancer screening behavior (n=9) [19-27]; documented cancer screening less often than USPSTF recommended guidelines at the time of the study (e.g. having ever been screened) (n=4)[28-31]; did not assess health literacy with a validated instrument (n=2)[32, 33]; presented combined cancer screening behaviors for multiple anatomic sites into one overall cancer screening rate (n=2) [34, 35]; or were conducted outside of the U.S. (n=2) [36, 37].

3. Results

The resulting 10 articles, including 14 comparisons of health literacy and cancer screening, were published between 2004 and electronically by the beginning of 2012. The articles include 4 studies of colorectal cancer screening (Table 1) [38-41], 5 studies of breast cancer screening (Table 2) [39, 42-45], 3 studies of cervical cancer screening (Table 3) [39, 42, 46], and 2 studies of prostate cancer screening (Table 4) [39, 47].

Table 1.

Health literacy and colorectal cancer screening

| Author (Year) | Shelton[38] (2011) | White[39]* (2008) | Liu[40] (2011) | Miller[41] (2007) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size & Gender | 400 M&F | 18,100 M&F | 42 M&F | 50 M&F | |

| Study Design | CSS | CSS | QES | CSS | |

| Health Literacy/Numeracy | Instrument | SAHLSA | NAAL | S-TOFHLA | REALM |

| Inadequate Health Literacy Definition | NP | 0-225 | 0-22 | 0-60 | |

| Inadequate Health Literacy (%) | NP | 36 | NP† | 48 | |

| Cancer Screening | Test | FOBT‡, COL¶ | CRC Screening (undefined)‡ | FOBT‡, FS§, COL¶ | FOBT‡, FS§, COL¶ |

| Measure | SR | SR | SR | SR | |

| Study Population Completion Rate (%) | 59 | 40 | 55 | 56 | |

| Population Characteristics | Clinic Based Sample | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Female (%) | 72 | 60 | 72 | ||

| Age Range | 50-65+ | 16-65+ | 50+ | 50+ | |

| White (%) | NP | 71 | 43 | 42 | |

| Black (%) | NP | 11 | 57 | 58 | |

| Latino (%) | 100 | 12 | NP | NP | |

| Uninsured (%) | 7 | 18 | NP | 20 | |

| Household Income (%) | 67 <$10,000 |

17 <poverty level |

NP | 87 <$25,000 |

|

| Association | Effect Size | OR: 0.99 (0.95-1.05) | MML Probit Coefficient: 50-64 years old: −0.04 (0.3SE) 65+ years old: 0.10 (0.03 SE) |

NP | RR: 0.99 (0.64-1.55) |

| Adjusted | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Significance | No significant association | 50-64 years old: No significant association 65+ years old: Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening |

No significant association | No significant association | |

F: Female; M: Male; CSS: Cross Sectional Survey; QES: Quasi-Experimental Pre-Post Survey; SAHLSA: Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Spanish Adults (Scale 0-50); NAAL: National Assessment of Adult Literacy (Scale: 0-500); S-TOFHLA: Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (Scale: 0-36); REALM: Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (Scale: 0-66); NP: not provided FOBT: Fecal Occult Blood Test; FS: Flexible Sigmoidoscopy; COL: Colonoscopy; CRC: Colorectal Cancer; SR: Self-Report

Population characteristics provided for the total sample

Mean Score=33.62

Previous year

Previous 5 years

Previous 10 years.

Table 2.

Health literacy and breast cancer screening

| Author (Year) | White[39]* (2008) | Garbers[42]* (2009) | Bennett[43]* (2009) | Guerra[44] (2005) | Pagan[45] (2012) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 18,100 (52% female) | 697 | 2,668 (55% female) | 97 | 722 | |

| Study Design | CSS | CSS | CSS | CSS | CSS | |

| Health Literacy/Numeracy | Instrument | NAAL | TOFHLA-S | NAAL | S-TOFHLA (English or Spanish) | S-TOFHLA (English or Spanish) |

| Inadequate Health Literacy Definition | 0-225 | 0-59 | 0-225 | 0-22 | 0-22 | |

| Inadequate Health Literacy (%) | 36 | 24 | 58 | 52 | 50 | |

| Cancer Screening | Test | Mammo† | Mammo‡ | Mammo† | Mammo† | Mammo†, § |

| Measure | SR | EDR | SR | SR | SR | |

| Study Population Completion Rate (%) | 61 | 57 | 66 | 69 | 62 (last 2 yrs) 44 (last 1 yr) |

|

| Population Characteristics | Clinic Based Sample | No | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Age Range | 16-65+ | 40+ | 65+ | 41-85 | 40-70+ | |

| White (%) | 71 | NP | 85 | NP | NP | |

| Black (%) | 11 | NP | 7 | NP | NP | |

| Latino (%) | 12 | 100 | 5 | 100 | 100 | |

| Uninsured (%) | 18 | 99 | NP | 26 | 27 | |

| Household Income (%) | 17 <poverty level |

100 <250% poverty level |

18 <poverty level |

63 <$10,000 |

58 ≤$10,000 |

|

| Association | Effect Size | MML Probit Coefficient: 40-64 years old: −0.05 (0.03 SE) 65+ years old: 0.20 (0.04SE) |

X2: 0.58 | MML Probit Coefficient: 0.17(0.04) | OR: 1.01 (0.95-1.08) | OR: Past year: 2.30 (1.54-3.43) Past 2 years: 1.70 (1.14-2.53) |

| Adjusted | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Significance | 40-64 years old: No significant association; 65+ years old: Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening |

No significant association | Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening | No significant association | Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening | |

CSS: Cross Sectional Survey; NAAL: National Assessment of Adult Literacy (Scale: 0-500); TOFHLA-S: Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults-Spanish (Scale: 0-100); S-TOFHLA: Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (Scale: 0-36); Mammo: Mammogram; SR: Self Report; EDR: Electronic Database Review; NP: not provided

Population characteristics provided for the total sample.

previous year

previous 8 months

previous 2 years.

Table 3.

Health literacy and cervical cancer screening

| Author (Year) | White[39]* (2008) | Garbers[42]* (2009) | Garbers[46] (2004) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 18,100 (52% female) | 310 | 205 | |

| Study Design | CSS | CSS | CSS | |

| Health Literacy/Numeracy | Instrument | NAAL | TOFHLA-S | TOFHLA-S |

| Inadequate Health Literacy Definition | 0-225 | Inadequate: 0-59 Marginal: 60-74 |

0-59 | |

| Inadequate Health Literacy (%) | 36 | Inadequate: 24 Marginal: 14 |

Inadequate: 30 Score 0: 12 |

|

| Cancer Screening | Test | PAP‡ | PAP† | PAP§ |

| Measure | SR | EDR | SR (10% Sampled MRR) | |

| Study Population Completion Rate (%) | 69 | 75 | 92 | |

| Population Characteristics | Clinic Based Sample | No | Yes | Yes |

| Age Range | 16-65+ | 40+ | 40-78 | |

| White (%) | 71 | NP | NP | |

| Black (%) | 11 | NP | NP | |

| Latino (%) | 12 | 100 | 100 | |

| Uninsured (%) | 18 | 99 | 58 | |

| Household Income (%) | 17 <poverty level |

100 <250% poverty level |

NP | |

| Association | Effect Size | MML Probit Coefficient: 18-39 years old: 0.05 (0.02 SE) 40-64 years old: −0.06 (0.03 SE) |

OR: Inadequate and Marginal : 2.27 (1.13-4.60) | OR: Inadequate: 0.53 (0.21-1.35) Score 0: 0.24 (0.07-0.85) |

| Adjusted | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Significance | 18-39 years old: Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening 40-64 years old: No significant association |

Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with MORE screening | Inadequate: No significant association Score=0: Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening |

|

CSS: Cross Sectional Survey; NAAL: National Assessment of Adult Literacy (Scale: 0-500); TOFHLA-S: Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults-Spanish (Scale:0-100); Pap: Papanicolaou test; SR: Self Report; EDR: Electronic Database Review; MRR: Medical Record Review; NP: not provided

Population characteristics provided for the total sample.

Previous 60 days

Previous year

Previous 3 years.

Table 4.

Health literacy and prostate cancer screening

| Author (Year) | White[39]* (2008) | Ross[47] (2010) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | 18,100 (48% male) | 49 | |

| Study Design | CSS | QES | |

| Health Literacy/Numeracy | Instrument | NAAL | TOFHLA |

| Inadequate Health Literacy Definition | 0-225 | 0-59 | |

| Inadequate Health Literacy (%) | 36 | 22 | |

| Cancer Screening | Test | Prostate Cancer Screening (unspecified test)† | PSA† |

| Measure | SR | SR | |

| Study Population Completion Rate (%) | 31 | 55 | |

| Population Characteristics | Clinic Based Sample | No | No |

| Age Range | 16-65+ | 35-91 | |

| White (%) | 71 | 0 | |

| Black (%) | 11 | 100 | |

| Latino (%) | 12 | NP | |

| Uninsured (%) | 18 | NP | |

| Household Income (%) | 17 <poverty level |

33 <$25,000 |

|

| Association | Effect Size | MML Probit Coefficient: 40-64 years old: 0.09 (0.03 SE) 65+ years old: 0.08 (0.04 SE) |

NP |

| Adjusted | Yes | No | |

| Significance | 40-64 years old: Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening 65+ years old: Inadequate health literacy significantly associated with LESS screening |

No significant association | |

CSS: Cross Sectional Survey; QES: Quasi-Experimental Pre-Post Survey; NAAL: National Assessment of Adult Literacy (Scale: 0-500); TOFHLA: Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (Scale: 0-100); PSA: Prostate Specific Antigen; SR: Self-Report; NP: not provided

Population characteristics provided for the total sample.

Previous year.

3.1 Colorectal cancer screening

Participants were recruited from medical clinics and community-based samples in urban and rural settings for the four studies about health literacy and colorectal cancer (CRC) screening (Table 1). Two studies were conducted in Spanish or English [38, 39], with one study conducting the literacy assessment only in English [39]. Most studies did not mention if individuals were excluded based on increased risk for CRC or included individuals at increased-risk or high-risk for CRC [39-41]. All studies included both males and females in their study population and used cross sectional data to investigate the relationship between health literacy and CRC screening. The single study using a quasi-experimental design analyzed pre-test data only to investigate the possible relationship between health literacy and screening [40]. All studies used self-report of CRC screening, and screening ranged from 40%-59% [38-41]. Two studies did not provide the study sample's inadequate health literacy proportion [38, 40] and it was reported as 36% and 48% in the other two studies [39,41].

One large study found a significant positive relationship between health literacy and CRC screening among adults 65 years of age and older and no significant association among adults 50-64 years old [39]. The remaining three studies found no significant association between health literacy and CRC screening [38, 40, 41]. There is limited evidence for a relationship between health literacy and CRC screening according to USPSTF guidelines.

3.2 Breast cancer screening

Five studies were reviewed for health literacy and breast cancer screening (Table 2). Study participants were recruited from health care clinics, community locations, and a nationally representative sample in urban and rural settings. One study included only women older than 65 years of age [43]. All studies offered at least part of the interview in Spanish or English [39, 42-45]. Three of the five studies offered the health literacy assessment in Spanish or English [42, 44, 45]. All studies did not mention if individuals were excluded based on increased risk for breast cancer or included women at high-risk for breast cancer. Cross sectional data was used in each study, and only one of the five studies confirmed screening with medical record review [42]. Breast cancer screening ranged from 44% to 69% [39, 42-45]. Inadequate health literacy ranged from 24% to 58% [39, 42-45]. Three studies found a significant relationship between inadequate health literacy and lower cancer screening rates [39, 43, 45]. In one study the significant relationship between health literacy and screening was only among women 65+ years [39]. The evidence for a relationship between health literacy and breast cancer screening is limited, although trending in a positive direction.

3.3 Cervical cancer screening

Three studies were reviewed for health literacy and cervical cancer screening (Table 3). One study used self-report of cancer screening [39], one study combined self-report with medical record review of a subsample [46], and one study completed an electronic record database review [42]. Participants were recruited from urban medical clinics and a national survey. Two of the studies included women 40+ years of age [42, 46], while the national survey included women 18+ year old [39]. All studies were conducted in Spanish or English [39,42,46]. One study conducted the health literacy assessment only in English [39]. All studies either did not mention if participants were excluded based on being at increased risk for cervical cancer or included women at high-risk for cervical cancer. All studies used a cross-sectional study design. Cancer screening ranged from 69% to 92% and inadequate health literacy ranged from 24% to 36% [39,42,46]. Two studies found a significant positive association between inadequate health literacy and lower screening rates [39, 46]. In one study the positive relationship was only among women younger than 40 years of age [39]. The remaining study found a significant negative relationship between health literacy and cervical cancer screening (women with inadequate health literacy were more likely to receive a Pap test) [42]. The overall evidence for a relationship of health literacy and cervical cancer screening is mixed.

3.4 Prostate cancer screening

Two studies focused on prostate cancer screening (Table 4). Participants were recruited from the community and a national survey. Both studies included men younger than age 50; with one study of African Americans including men as young as age 35 [47]. Both studies did not specifically mention if individuals were excluded based on being at increased risk for prostate cancer or included men at high-risk for prostate cancer. One study was conducted in Spanish or in English, with the health literacy assessment being conducted in English [39]. In both studies, prostate cancer screening (31% and 55%) were by self-report. Inadequate health literacy in the studies was 22% and 36% [39,47]. One small study used a pre-post test design, assessed health literacy and cancer screening from the baseline data, and did not find a significant association [47]. The large national study used a cross-sectional study design and found inadequate health literacy associated with lower rates of prostate screening [39]. The overall evidence for a relationship between health literacy and prostate cancer screening is limited.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

Previous research suggests that inadequate health literacy may be a factor contributing to lower cancer screening rates and subsequent cancer disparities [3]. This is important since limited health literacy affects 36% (22% basic and 14% below basic) of adults living in the U.S. [48]. Among the 14 comparisons in the 10 reviewed articles that provided information about the association of health literacy measured with a validated instrument and cancer screening within recommended guidelines in the U.S., seven found a significant positive relationship, one found a significant negative relationship, and six found no significant association.

Methodological issues excluded several studies from being included in the review and also made it challenging to compare the included studies. Consequently, it is not possible to provide a definitive answer about health literacy and cancer screening behaviors. No single agreed upon standardized measure of health literacy is one of the methodological issues making the review difficult. Health literacy, as a concept, is multifaceted and includes many components. Although there are many skill sets included in health literacy, the validated instruments used in the reviewed articles measure only a subsample of those skill sets. The development of a single, acceptable instrument with good psychometric properties that could be completed in a short amount of time would improve our ability to compare results among different populations in various settings. As multiple components of health literacy may effect an individual's decision about completing a cancer screening test, the use of primarily reading tests may not capture important components of health literacy. An example of this issue is an individual who may be able to read but does not understand their cancer risk because of inadequate numeracy skills. Despite the lack of a single best health literacy measure, several instruments with accumulated evidence of validity do exist. Among the 10 articles included in this review, the most common validated health literacy instruments used were the S-TOFHLA, REALM, and the NAAL. Even though these validated instruments were used, inadequate health literacy was defined differently among studies (e.g. marginal literacy included or not included in inadequate literacy rates).

The second health literacy measurement issue has to with the complex crossroads of individuals, different languages, and cultural diversity. It would be ideal, and probably impossible, if any health literacy measure could be applicable among diverse populations. This is significant because words translated from one language to another language may not have the same meaning; or specific words used may hold different meanings or values among diverse populations. Additionally, oral fluency may not be a good indicator of understanding in non-native English speaking populations [49]. As six of the 14 anatomic site-specific comparisons included in this review were conducted among a Hispanic or Latino population, this factor may play a significant role in the findings. It is important to use health literacy instruments developed and validated in other languages (e.g. Spanish) when possible [11,12]. The difficulties associated with the translation of different languages is a considerable health literacy issue emerging in the U.S. and may be a contributing factor associated with cancer screening disparities. New strategies to address this issue, such as patient navigation, are increasingly important to minimize disparities in cancer screening rates among certain population groups [50, 51].

The documentation of cancer screening completion is the third methodological issue raised by the reviewed articles. Cancer screening completion has been reported using an individual's self-report, medical record review (paper and electronic records), or review of Medicare claims data. Cancer screening status in the reviewed articles was often determined based on self-report, with eight of the ten articles documenting cancer screening completion by self-report only. The accuracy of using self-report for cancer screening completion has lead to errors described in numerous studies and should not be used as the gold standard in research [52-61]. In addition, the accuracy of self-report of cancer screening may differ by gender [62], cancer screening test [52, 57, 61], using Medicare claims data [56, 63], or based on the review of paper versus electronic medical records [64]. This issue may potentially be resolved by using electronic medical records within a closed health system to avoid discordant findings between self-report of cancer screening and medical record review, especially among patients with multiple providers.

The lack of uniform cancer screening test intervals and age recommendations (initiation and ending) for the various cancer screening tests is another important methodological issue. For example, the breast cancer screening studies reviewed measured the completion of a mammogram in the previous 12, 18, or 24 months [39, 42-45]. Documenting the timing of screening behaviors different from recommended guidelines may over or underestimate individuals engaging in appropriate cancer screening. In addition, some studies included individuals not within the age range recommended for specific cancer screening tests. This issue may reflect differing cancer screening recommendations by various professional societies and modification of screening recommendations based on emerging scientific information [65-68]. Prostate cancer screening presents a special challenge in this regard as new recommendations suggest that the pros and cons of prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing be discussed with men to achieve an informed shared decision between patient and health care provider [67]. Therefore, the findings in this review for prostate cancer screening must not be over-interpreted especially from the study taking place after the recent guideline change which sought to achieve discussion and shared decision making and not necessarily screening completion [47].

The lack of information about the population included in the different studies is another methodological issue that needs to be addressed by investigators. Although it is difficult to determine by the information provided in some studies included in this review, analysis of cancer screening within recommended guidelines must reflect whether individuals are at average-risk, increased-risk, or high-risk for a specific cancer. Recommended cancer screening tests and intervals differ depending on risk and this information is important when documenting completion of cancer screening. In addition, the prevalence of inadequate health literacy within a population should be described since this factor also influences study findings. The population information that was available seems to demonstrate a non-representative sample in many of the reviewed studies. In addition to using an exclusively Hispanic/Latino population in 6 of the 14 comparisons in this review, the studies represent a sample with greater likelihood of living below the poverty level ($22,350 for a family of four) than the national average of 15% in 2011 [69]. Furthermore, six of the 14 comparisons included study populations recruited from health clinics [38, 41, 42, 44, 46]. Although it is unknown how these factors may affect the interpretation of study results, these individuals have already demonstrated some capability to access the complex health care system and therefore are not representative of non-clinic based populations.

Additional methodological issues that may have contributed to inconsistent results among the studies reviewed are the differing study designs, study locations, sampling methods, sample sizes, lack of power, and the lack of adjustment for confounders. It is interesting to note that four of the six comparisons that found no association of health literacy and cancer screening included less than 100 participants, and the one large national survey study accounted for four of the seven comparisons with a significant positive association of inadequate health literacy and lower cancer screening rates. Finally, several studies measured health literacy and cancer screening behaviors but failed to report the relationship and thus could not be included in this review. Although most of these studies were testing an intervention to increase cancer screening rates, the lack of reporting this important information presents a bias in the scientific literature.

The review has several limitations. First, although numerous databases were searched, appropriate articles may have been missed. To minimize this possibility, both health literacy and literacy was used in the search methodology. Second, the review was limited to only scientific articles published in English. Third, to be able to compare across studies, 19 articles were excluded from review based on varying methodology issues. Future studies should report investigated associations between health literacy and cancer screening regardless of the result of these possible associations. Finally, we included only studies that reported both a measure of health literacy and cancer screening behavior according to USPSTF guideline intervals. Thus, studies that report the relationship of health literacy and cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, or behavior outside of USPSTF recommended intervals were not included in this review.

4.2 Conclusions

This review highlights the current evidence in the literature about health literacy and cancer screening behaviors. There is a trend for the association of inadequate health literacy and lower cancer screening rates within recommended guidelines. Considering that there is strong evidence for a relationship between health literacy and other health outcomes, further research focused on health literacy and cancer screening behavior is warranted.

4.3 Practice implications

In order to truly understand the role that health literacy plays in the completion of cancer screening, future research should: a) be conducted using validated health literacy instruments; b) measure cancer screening according to recommended guidelines; c) verify the completion of cancer screening with medical record review or electronic health record review; d) describe the population included in the study (e.g. average- vs. high-risk); e) adjust for confounding factors (e.g. demographic variables); and f) report effect size of the association (significant or not significant) of health literacy and cancer screening. If future research focuses on these recommendations, the association between health literacy and cancer screening will become more clear, and investigators can focus on developing interventions to improve cancer screening rates among all population groups. Given the current strong evidence for health literacy and other health outcomes, and the evidence showing a trend for an association between inadequate health literacy and lower cancer screening rates within recommended guidelines, the health literacy of patients warrants consideration by providers. Providers can address the possible influence of inadequate health literacy by engaging patients using pictorial representations of cancer screening tests, checking for understanding using the teach-back methodology, and ensuring that cancer screening status is documented and updated in medical records [70-72]. By addressing the health literacy of patients, providers can assist them in the cancer screening process.

Acknowledgments

Contributors: The authors would like to thank Dr. Erica Breslau for her helpful comments and suggestions about an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Funders: This work was supported by the following grant: K07 CA107079 (MLK)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: No financial disclosures.

Author Statement: “I confirm that the patient/person(s) have read this manuscript and given their permission for it to be published in PEC.”

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–36. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2012: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:129–142. doi: 10.3322/caac.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis TC, Williams MV, Marin E, Parker RM, Glass J. Health literacy and cancer communication. CA Cancer J Clin. 2002;52:134–49. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.52.3.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Medicine of the National Acadamies . Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christ WG, Potter WJ. Media literacy, media education, and the academy. Journal Comm. 1998;48:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Sayah F, Williams B, Johnson JA. Measuring health literacy in individuals with diabetes: a systematic review and evaluation of available measures. Health Educ Behav. 2013;40:42–55. doi: 10.1177/1090198111436341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Center for Educational Statistics . National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis TC, Crouch MA, Long SW, Jackson RH, Bates P, George RB, Bairnsfather LE. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23:433–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, Crouch MA. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baker DW, Williams MV, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nurss J. Development of a brief test to measure functional health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(98)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parker RM, Baker DW, Williams MV, Nurss JR. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10:537–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02640361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, Mockbee J, Hale FA. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the newest vital sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:514–22. doi: 10.1370/afm.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36:588–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, Noorbaloochi S, Grill JP, Snyder A, Bradley KA, Nugent SM, Baines AD, Vanryn M. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:561–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B. The Single Item Literacy Screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCormack L, Bann C, Squiers L, Berkman ND, Squire C, Schillinger D, Ohene-Frempong J, Hibbard J. Measuring health literacy: A pilot study of a new skills-based instrument. J Health Comm. 2010;15:51–71. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bann CM, McCormack LA, Berkman ND, Squiers LB. The Health Literacy Skills Instrument: a 10-item short form. J Health Comm. 17(Suppl 3):191–202. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.718042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Viera A, Crotty K, Holland A, Brasure M, Lohr KN, Harden E, Tant E, Wallace I, Viswanathan M. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evid Rep Technol Assess. 2011 Mar;(199):1–941. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferreira MR, Dolan NC, Fitzgibbon ML, Davis TC, Gorby N, Ladewski L, Liu D, Rademaker AW, Medio F, Schmitt BP, Bennett CL. Health care provider-directed intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among veterans: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1548–54. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Geller BM, Skelly JM, Dorwaldt AL, Howe KD, Dana GS, Flynn BS. Increasing patient/physician communications about colorectal cancer screening in rural primary care practices. Med Care. 2008;46(Suppl 1):S36–43. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817c60ea. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz ML, Fisher JL, Fleming K, Paskett ED. Patient Activation Increases Colorectal Cancer Screening Rates: A Randomized Trial among Low-Income Minority Patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:45–52. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller DP, Jr., Spangler JG, Case LD, Goff DC, Jr., Singh S, Pignone MP. Effectiveness of a web-based colorectal cancer screening patient decision aid a randomized controlled trial in a mixed-literacy population. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:608–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson JM, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Cancer information comprehension by English-as-a-second-language immigrant women. J Health Comm. 2011;16:17–33. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.529496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson EA, Wolf MS, Curtis LM, Clayman ML, Cameron KA, Eigen KV, Makoul G. Literacy, cognitive ability, and the retention of health-related information about colorectal cancer screening. J Health Comm. 2010;15(Suppl 2):116–25. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.499984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis TC, Berkel HJ, Arnold CL, Nandy I, Jackson RH, Murphy PW. Intervention to increase mammography utilization in a public hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:230–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00072.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Erwin DP, Erwin DO, Ciupak G, Hellenthal N, Sofi MJ, Guru KA, Edge SB. Challenges and implementation of a women's breast health initiative in rural Kashmir. Breast. 2011;20(Suppl 2):S46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindau ST, Tomori C, Lyons T, Langseth L, Bennett CL, Garcia P. The association of health literacy with cervical cancer prevention knowledge and health behaviors in a multiethnic cohort of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:938–43. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott TL, Gazmararian JA, Williams MV, Baker DW. Health literacy and preventive health care use among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. Med Care. 2002;40:395–404. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson NB, Dwyer KA, Mulvaney SA, Dietrich MS, Rothman RL. The influence of health literacy on colorectal cancer screening knowledge, beliefs and behavior. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1105–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guerra CE, Dominguez F, Shea JA. Literacy and knowledge, attitudes, and behavior about colorectal cancer screening. J Health Comm. 2005;10:651–63. doi: 10.1080/10810730500267720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aggarwal A, Speckman JL, Paasche-Orlow MK, Roloff KS, Battaglia TA. The role of numeracy on cancer screening among urban women. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31:S57–68. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ciampa PJ, Osborn CY, Peterson NB, Rothman RL. Patient numeracy, perceptions of provider communication, and colorectal cancer screening utilization. J Health Comm. 2010;15(Suppl 3):157–68. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schapira MM, Neuner J, Fletcher KE, Gilligan MA, Hayes E, Laud P. The relationship of health numeracy to cancer screening. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:103–10. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0133-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho YI, Lee SYD, Arozullah AM, Crittenden KS. Effects of health literacy on health status and health service utilization amongst the elderly. Social Science & Medicine. 2008;66:1809–16. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Todd L, Harvey E, Hoffman-Goetz L. Predicting breast and colon cancer screening among English-as-a-second-language older Chinese immigrant women to Canada. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:161–9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee SY, Tsai TI, Tsai YW, Kuo KN. Health Literacy and Women's Health-Related Behaviors in Taiwan. Health Educ Behav. 2012;39:210–8. doi: 10.1177/1090198111413126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shelton RC, Jandorf L, Ellison J, Villagra C, Duhamel KN. The Influence of Sociocultural Factors on Colonoscopy and FOBT Screening Adherence among Low-income Hispanics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:925–44. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White S, Chen J, Atchison R. Relationship of preventive health practices and health literacy: A national study. Am J Health Behav. 2008 May-Jun;32(3):227–42. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu CJ, Fleck T, Goldfarb J, Green C, Porter E. Attitudes to Colorectal Cancer Screening After Reading the Prevention Information. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26:710–7. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0210-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller DP, Jr., Brownlee CD, McCoy TP, Pignone MP. The effect of health literacy on knowledge and receipt of colorectal cancer screening: a survey study. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;8:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garbers S, Schmitt K, Rappa AM, Chiasson MA. Functional health literacy in Spanish-speaking Latinas seeking breast cancer screening through the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Screening Program. Int J Womens Health. 2010;1:21–9. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett IM, Chen J, Soroui JS, White S. The contribution of health literacy to disparities in self-rated health status and preventive health behaviors in older adults. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:204–11. doi: 10.1370/afm.940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guerra CE, Krumholz M, Shea JA. Literacy and knowledge, attitudes and behavior about mammography in Latinas. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16:152–66. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pagan JA, Brown CJ, Asch DA, Armstrong K, Bastida E, Guerra C. Health Literacy and Breast Cancer Screening among Mexican American Women in South Texas. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27:132–7. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garbers S, Chiasson MA. Inadequate functional health literacy in Spanish as a barrier to cervical cancer screening among immigrant Latinas in New York City. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1:A07. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross L, Ashford AD, Bleechington SJ, Dark T, Erwin DO. Applicability of a video intervention to increase informed decision making for prostate-specific antigen testing. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:228–36. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kutner M, Greenburg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C, National Center for Educational Statistics WDC. American Institutes for Research KMD . The Health Literacy of America's Adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. NCES 2006-483: National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dowse R, Lecoko L, Ehlers MS. Applicability of the REALM health literacy test to an English second-language South African population. Pharmacy World & Science. 2010;32:464–71. doi: 10.1007/s11096-010-9392-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: an update on the state of the science. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2011;61:237–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, Casey AA, Goddu AP, Keesecker NM, Cook SCV. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:992–1000. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2082-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones RM, Mongin SJ, Lazovich D, Church TR, Yeazel MW. Validity of four self-reported colorectal cancer screening modalities in a general population: differences over time and by intervention assignment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:777–84. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paskett E, Tatum C, Rushing J, Michielutte R, Bell R, Long Foley K, Bittoni M, Dickinson SL, McAlearney AS, Reeves K. Randomized trial of an intervention to improve mammography utilization among a triracial rural population of women. J Natl Cancer Institut. 2006;98:1226–37. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Cho YI, Walk JA. Accuracy of self-reported cancer-screening histories: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:748–57. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shokar NK, Vernon SW, Carlson CA. Validity of self-reported colorectal cancer test use in different racial/ethnic groups. Family Practice. 2011;28:683–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schenck AP, Klabunde CN, Warren JL, Peacock S, Davis WW, Hawley ST, Pignone M, Ransohoff DF. Evaluation of claims, medical records, and self-report for measuring fecal occult blood testing among medicare enrollees in fee for service. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:799–804. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferrante JM, Ohman-Strickland P, Hahn KA, Hudson SV, Shaw EK, Crosson JC, Crabtree BF. Self-report versus medical records for assessing cancer-preventive services delivery. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;7:2987–94. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Howard M, Agarwal G, Lytwyn A. Accuracy of self-reports of Pap and mammography screening compared to medical record: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes & Control. 2009;20:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caplan LS, McQueen DV, Qualters JR, Leff M, Garrett C, Calonge N. Validity of women's self-reports of cancer screening test utilization in a managed care population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(11 Pt 1):1182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holt K, Franks P, Meldrum S, Fiscella K. Mammography self-report and mammography claims: racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic discrepancies among elderly women. Medical Care. 2006;44:513–8. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215884.81143.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGovern PG, Lurie N, Margolis KL, Slater JS. Accuracy of self-report of mammography and Pap smear in a low-income urban population. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:201–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(97)00076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Griffin JM, Burgess D, Vernon SW, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Powell A, van Ryn M, Halek K, Noorbaloochi S, Grill J, Bloomfield H, Partin M. Are gender differences in colorectal cancer screening rates due to differences in self-reporting? Prev Med. 2009;49:436–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fiscella K, Holt K, Meldrum S, Franks P. Disparities in preventive procedures: comparisons of self-report and Medicare claims data. Bmc Health Services Research. 2006;6:122. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clark CR, Baril N, Kunicki M, Johnson N, Soukup J, Lipsitz S, Bigby J. Mammography use among Black women: the role of electronic medical records. Journal of Women's Health. 2009;18:1153–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:627–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Moyer VA. Screening for cervical cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:880–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-12-201206190-00424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:120–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-2-201207170-00459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:716–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. United States Department of Commerce. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington: 2012. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011. Report Number P60-243. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bertakis KD. The communication of information from physician to patient: a method for increasing patient retention and satisfaction. J Fam Pract. 1977;5:217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schillinger D, Piette J, Grumbach K, Wang F, Wilson C, Daher C, Leong-Grotz K, Castro C, Bindman AB. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:83–90. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Houts PS, Doak CC, Doak LG, Loscalzo MJ. The role of pictures in improving health communication: A review of research on attention, comprehension, recall, and adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:173–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]