Abstract

The two objectives of the current study were: (1) to identify daily patterns of negative affect (NA) in obese individuals; and (2) to determine whether daily affect patterns were related to overeating without loss of control (OE-only), loss of control eating without overeating (LOC-only), and binge eating (BE) episodes. Fifty obese (BMI=40.3±08.5) adults (84.0% female) completed a two-week ecological momentary assessment protocol during which they completed assessments of NA and indicated whether their eating episodes were characterized by OE and/or LOC. Latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM) was used to identify daily trajectories of NA. GEE analysis was used to determine whether daily affect trajectories were differentially related to the frequency of OE-only, LOC-only, and BE episodes. The LGMM analyses identified nine unique trajectories of NA. Significantly higher frequencies of OE-only and BE episodes occurred on days characterized by high or increasing levels of NA. There were no significant differences between classes for the frequency of LOC-only episodes. These data suggest that NA may act as an antecedent to OE-only and BE episodes and that targeting “problematic affect days” may reduce the occurrence of OE-only and BE episodes among obese individuals.

Keywords: latent growth mixture modeling, mood, obesity

1. Introduction

Binge eating is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) as having two key characteristics, namely, the consumption of an objectively large amount of food and the subjective feeling that one has lost control during the eating episode (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Binge eating is relatively common and is associated with significant medical and psychiatric comorbidities, including increased risk of overweight and obesity (Hudson et al., 2007). Although not all individuals who binge eat are overweight or obese, those individuals with concurrent binge eating and obesity are typically older, have a longer duration of illness, eat more meals and snacks throughout the day, and exercise less than non-obese binge eaters (Goldschmidt et al., 2011). Similarly, compared to obese individuals who do not binge eat, individuals with concurrent obesity and binge eating report greater body dissatisfaction (Striegel-Moore et al., 1998; Hsu et al., 2002), higher disinhibition (Wadden et al., 1993; de Zwaan et al., 1994; Hsu et al., 2002) more psychopathology (Wadden et al., 1993; Striegel-Moore et al., 1998), more frequent weight fluctuations (de Zwaan et al., 1994), and consume more calories during both meals and binges in laboratory settings (Yanovski et al., 1992; Goldfein et al., 1993; Hsu et al., 2002). These findings suggest that although binge eating and obesity are each associated with physiological and psychological consequences, the combination of binge eating and obesity may be particularly problematic with regard to comorbidity and risk.

During the past two decades, there has been growing interest in the relationship between affect, particularly negative affect (NA), and binge eating among individuals who are obese (OBE). Early descriptive research on OBE found that mood alteration was often cited as a motivation for OBE (Arnow et al., 1992; Arnow et al., 1995), that OBE was often precipitated by NA (Arnow et al., 1992), and that there was a significant positive correlation between emotional eating and the severity of OBE (Arnow et al., 1995). Experimental designs corroborated these findings by demonstrating that exposure to NA through mood induction increased the likelihood that individuals with OBE experienced their eating as out of control, defined their eating as a “binge”, and engaged in investigator-defined binge eating (Agras and Telch, 1998). More recently, research using ecological momentary assessment (EMA) has demonstrated that loss of control eating episodes among obese individuals are associated with both increased stress and increased NA, regardless of whether the episodes were characterized by overeating (Goldschmidt et al., 2012). Taken together, these findings appear to provide robust support for the hypothesis that OBE is associated with fluctuations in momentary affect, and more specifically, increases in NA.

However, the extent to which conclusions can be drawn regarding the relationship between binge eating and affect is limited by methods used to define and identify episodes of binge eating. As stated above, binge eating is characterized by both the consumption of an objectively large amount of food and the subjective feeling that one has lost control during the eating episode (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Although the DSM-IV-TR requires that both features be present, individuals with concurrent binge eating and obesity self-define binge eating primarily in terms of whether loss of control is present (Telch et al., 1993). This finding suggests that self-defined binge eating episodes may differ qualitatively from investigator-defined binge eating episodes such that they may be more likely to reflect loss of control eating than binge eating (i.e., the combination of loss of control and overeating).

Given that the accuracy of binge eating assessments depends on the definition of binge eating used (e.g., self-defined vs. investigator-defined), it is important to evaluate research findings in this context. For example, one of the studies described above defined binge eating only in terms of whether loss of control was present (Arnow et al., 1992), and a second study only utilized self-defined binge eating episodes in analyses (Arnow et al., 1995). Although the two other studies described above (Agras and Telch, 1998; Goldschmidt et al., 2012) did assess both features of binge eating (i.e., overeating and loss of control), these studies found significant effects for affect and loss of control eating, but not affect and overeating (defined in terms of caloric intake). Only one study found a significant relationship between affect and investigator-defined binge eating (i.e., both loss of control and overeating were present) (Agras and Telch, 1998). To summarize, three studies have found a relationship between affect and loss of control eating (Arnow et al., 1992; Agras and Telch, 1998; Goldschmidt et al., 2012), two studies have found a relationship between affect and self-defined binge eating (Arnow et al., 1995; Agras and Telch, 1998), and only one study has found a relationship between affect and investigator-defined binge eating (Agras and Telch, 1998). Because self-defined binge eating may be more characteristic of loss of control eating than binge eating (which is characterized by both loss of control and the consumption of an objectively large amount of food), these previous investigations appear to suggest that among obese individuals, momentary fluctuations in affect may be more closely associated with the experience of loss of control eating rather than binge eating.

The identification of binge eating episodes may also be impacted by the timing of the assessment relative to the binge eating episode(s) themselves. Specifically, research has demonstrated that some individuals who explicitly deny binge eating when assessed retrospectively will endorse binge eating when assessed in the moment (Green et al., 2000; Le Grange et al., 2001). Although it is possible that participants in these studies deliberately minimized their binge eating symptoms during the assessments utilizing retrospective recall, it seems unlikely given that they did endorse binge eating symptoms when assessed in the moment. It may be more likely that these differences result from retrospective recall biases such as current mood (Teasdale and Fogarty, 1979), retroactive reconstruction, and effort after meaning (Stone and Shiffman, 1994). Given this information, it is notable that two of the studies described above assessed binge eating retrospectively (Arnow et al., 1992; Arnow et al., 1995) whereas the other two utilized momentary assessment. Of the two studies that utilized momentary assessment of binge eating, one assessed binge eating in a laboratory setting (Agras and Telch, 1998), and one assessed binge eating using EMA (Goldschmidt et al., 2012). Although both laboratory settings and EMA procedures allow for momentary data collection, EMA procedures may be more ecologically valid given that they occur in the natural environment rather than in a laboratory setting (Shiffman et al., 2008).

In addition to being more ecologically valid, EMA procedures are also advantageous because they can be used to obtain information at regular intervals over relatively longer periods of time (e.g., days, weeks). As such, EMA data provide a unique opportunity to examine possible antecedents to behavior, such as whether fluctuations in affect precipitate episodes of binge eating. As stated above, one study has utilized EMA procedures to examine the relationship between affect and OBE (Goldschmidt et al., 2012). Although these studies suggest that increased NA may be associated with loss of control eating, these data do not establish how often increased NA is associated with loss of control eating. In addition, these previous investigations do not indicate whether NA fluctuates and if such fluctuations differ from day to day. Because the magnitude (i.e., high, low) and trajectory (e.g., increasing, decreasing) of NA may vary from day to day, some daily patterns of NA may be more likely to precipitate problematic eating behaviors such as overeating, loss of control eating, or binge eating. Understanding how daily NA patterns vary as well as how such variations are related to overeating, loss of control eating, and binge eating could provide critically important information for the treatment of binge eating and obesity (Crosby et al., 2009).

The first objective of the current study was to identify prototypical daily patterns of affect among obese individuals using latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM). The second objective was to determine whether there were differences between the daily affect patterns with regard to the frequency of overeating without loss of control (OE-only), loss of control eating without overeating (LOC-only), and binge eating (BE). Based on previous research from the OBE literature as well as previous LGMM findings in bulimia nervosa, it was hypothesized that days characterized by high or increasing levels of NA would be associated with more frequent LOC-only and BE episodes.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Obese (BMI>30) adults between the ages of 18 and 65 were recruited through community advertisements and flyers. Potential participants were excluded if they (a) met current or lifetime criteria for DSM-IV anorexia nervosa (AN) or bulimia nervosa (BN), (b) had received gastric bypass surgery, (c) were pregnant or breastfeeding, (d) were currently enrolled in treatment for obesity, or (e) were unable to read and understand English. Given that research has demonstrated that individuals may deny binge eating during retrospective recall, but endorse binge eating during EMA procedures, we elected to include obese individuals who denied binge eating at baseline to enhance the generalizability of the findings. We also elected to include obese individuals who denied binge eating at baseline because we were interested in examining the relationship between daily affect patterns and episodes of OE-only and LOC-only, both of which may be present in individuals who do not binge eat. A total of 105 individuals were screened for eligibility and 50 participants were enrolled in the EMA protocol. Of the 55 individuals who were screened but were not enrolled, 5 were eligible but decided against participating prior to scheduling the informational meeting, 13 were eligible but did not attend their informational meeting and could not be rescheduled, and 37 were ineligible. The most common reasons for ineligibility were regular use of inappropriate compensatory behaviors (n=19) or current or lifetime history of AN or BN (n=9).

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition – Eating Disorder Module (SCID-I/P)

The SCID-I/P (First et al., 1995) is a semi-structured interview that assesses current and lifetime history of Axis I psychopathology. The eating disorder module of the SCID-I/P was administered by a trained doctoral-level psychologist at baseline and was used to determine whether participants met criteria for current or lifetime DSM-IV AN and/or BN. The eating disorder module of the SCID-I/P was also used to establish current and lifetime history of full- and sub-threshold binge eating disorder (BED) at baseline. Full-threshold BED was defined as binge eating that occurred at least twice per week for the past 6 months and that was accompanied by distress as well as three or more features associated with binge eating (e.g., eating more rapidly than normal, eating until uncomfortably full, eating large amounts of food when not physically hungry, eating alone because of feeling embarrassed about how much one is eating, and feeling disgusted, depressed, or guilty after eating) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Participants were given a subthreshold BED diagnosis if they met all but one of the criteria for BED. Of the five participants who met lifetime or current criteria for subthreshold BED, two met all criteria for BED except that the binge eating episodes were not characterized by an objectively large amount of food, two did not meet the frequency criteria (i.e., they reported binge eating less than twice per week), and one did not report distress associated with the binge eating episodes. Individuals who endorsed regular compensatory behaviors (e.g., self-induced vomiting, laxative or diuretic misuse, fasting, or excessive exercise) were excluded from the study.

2.2.2. Positive and Negative Affect States (PANAS)

The PANAS (Watson et al., 1988) is a self-report questionnaire that measures two general dimensions of affect (i.e., positive and negative). To replicate the methodology used in previous EMA investigations (e.g., Smyth et al., 2007) and minimize the assessment burden on participants, an abbreviated PANAS NA scale was used. The following eleven items from the PANAS were chosen to assess momentary NA: afraid, lonely, irritable, ashamed, angry, distressed, nervous, dissatisfied with self, jittery, sad, and angry with self. Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they currently felt these emotions on a 05-point Likert scale, ranging from 01 (“not at all”) to 05 (“extremely”) on palmtop computers. The internal consistency of this abbreviated NA scale (α=00.91) was consistent with the internal consistency of the full NA scale when assessed at the momentary level (range of αs=00.85–00.91) (Watson and Clark, 1994).

2.2.3. Eating behaviors

Participants were asked to record all eating episodes on the palmtop computers, including the extent to which the eating episode was characterized by overeating and/or loss of control over eating. The questions used to assess overeating and loss of control eating were designed for the current study and based on conceptualizations of overeating and loss of control eating provided by the Eating Disorder Examination (e.g., Fairburn and Cooper, 2008). Participants were asked to record these behaviors immediately after they occurred (i.e., event contingent recording, see below for more detail), but were also given the opportunity to record them at the next signaled recording (i.e., signal contingent recording; see below for more detail). Overeating was assessed by asking participants to rate the extent to which they felt they had overeaten on a Likert scale from 01 (“not at all”) to 05 (“extremely”); episodes that were rated as ≥03 (i.e., at least “moderately”) were classified as episodes of overeating. Loss of control was assessed by asking to rate each of the following four questions on a Likert scale from 01 (“not at all”) to 05 (“extremely”): (a) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel a sense of loss of control?”, (b) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel that you could not resist eating?”, (c) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel that you could not stop eating once you had started?”, and (d) “While you were eating, to what extent did you feel driven or compelled to eat?”. Similarly, an episode was classified as loss of control eating if the participant rated at least one of the four loss of control items at ≥03 (i.e., at least “moderately”). Binge eating episodes were defined as episodes that met criteria for both overeating and loss of control eating.

2.3. Procedures

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota. Interested participants were initially screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria over the phone by a research coordinator. Participants who appeared eligible based on the phone screen were scheduled for an informational meeting during which they received information about the study. Participants who were interested then provided written informed consent, completed in-person assessments (i.e., Eating Disorder module of the SCID-I/P, measures of height and weight) to ensure eligibility, and then received instructions about how to complete EMA recordings on the palmtop computers. After being trained, participants were given palmtop computers and were instructed to complete practice ratings for two days. When participants returned, their practice data were reviewed and feedback regarding compliance rates was provided. These data were only used for training purposes and were not used in any analyses. At the end of the feedback session, participants were instructed to complete EMA assessments for the next two weeks. During the two-week assessment period, one in-person visit was scheduled with each participant. At the in-person visit, data from the palmtop computers were uploaded and participants were provided feedback regarding their compliance rates by a trained research coordinator. Participants received $150 for completing the two-week assessment period and were given a $50 bonus for completing at least 90% of assessments within 45 minutes of the palmtop signal.

The current EMA assessment protocol implemented three types of daily self-report methods: 1) signal contingent recording, 2) interval contingent recording, and 3) event contingent recording (Wheeler & Reis, 1991). For signal contingent recording, participants were signaled by the palmtop computer to complete EMA assessment ratings at six semi-random times throughout the day. These signals occurred semi-randomly, but were all within +/− 20 minutes of each of the six “anchor” times distributed evenly throughout the day: 08:30 a.m., 11:10 a.m., 01:50 p.m., 04:30 p.m., 07:10 p.m., and 09:50 p.m. With regard to interval contingent recording, participants were instructed to complete EMA assessment ratings at the end of each day. Finally, for event contingent recording, participants were instructed to provide EMA assessment ratings immediately after eating. During each recording, participants completed the PANAS and indicated whether they had eaten since their last recording. If participants had eaten since their last recording, they were also asked to indicate the extent to which the eating episode was characterized by overeating and/or loss of control eating.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM) (Muthen and Khoo, 1998; Muthen and Muthen, 2000) was used to identify prototypical patterns of daily patterns of NA from EMA assessments. The LGMM models were estimated using Mplus 6.11 software (Muthen and Muthen, 1999–2004). Following the procedures used by Crosby and colleagues (2009), only signal contingent ratings were included for analyses because of the comparable timeframe and frequency of ratings across participants. Also, days in which less than four signal contingent mood ratings were completed (typically “partial days on participants’ first and last days of EMA recordings) were excluded. Thus, from the 697 total participant days of EMA recordings, those days with less than four valid mood ratings (n=140) were excluded, leaving 557 participant days of EMA mood recordings (see Figure 01). LGMM models included an intercept, as well as linear and quadratic components to adequately characterize daily patterns of NA. The cubic component was not significant and dropped from the final LGMM model. Individual variation within class was allowed for both the intercept and the linear components, but was set to zero for the quadratic effect to facilitate model convergence.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of EMA data collected

The optimal number of classes was determined based upon the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Schwartz, 1978), the adjusted BIC (aBIC) (Sclove, 1987), the Akaike information criterion (AIC) (Akaike, 1973), and the consistent Akaike information criterion (cAIC) (Bozdogman, 1987), with the lowest values indicating the best fitting model. The entropy index (Ramaswamy et al., 1993) was also calculated for each model as an index of the average classification accuracy.

General estimating equations (GEE) (Liang and Zeger, 1986) with negative binomial response function were used to compare latent classes in terms of the frequency of overeating, loss of control, and binge eating episodes.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

Participants were 50 obese (BMI=40.3±08.5) adults (84% female, n=42), 12 (24%) of whom were diagnosed at baseline with lifetime full- or sub-threshold BED. Participants ranged in age from 21 to 64 (Mean=43.0±11.9) and the majority identified themselves as Caucasian (76%, n=38), followed by African American (14%, n=07), and Asian (6%, n=03), with other groups constituting 04% of the sample (n=02). The majority of participants were employed (78%, n=39) and a substantial minority had earned a college degree or higher (40%, n=20).

During the two-week EMA procedure, 40 participants (80%) endorsed having at least one OE-only episode, 42 (84%) endorsed having at least one LOC-only episode, and 48 (96%) endorsed at least one episode of BE. The frequency with which the three types of eating episodes occurred during the two-week assessment period varied substantially among the participants. The number of OE-only episodes endorsed ranged from 00 to 32 episodes (M=09.0, SD=08.9), the number of LOC-only episodes endorsed ranged from 00 to 55 episodes (M=08.0, SD=10.3), and the number of BE episodes ranged from 00 to 31 (M=07.1, SD=08.3). Of the 557 days included in the analyses, 285 included at least one OE-only episode, 236 included at least one LOC-only eating episode, and 227 included at least one BE episode. The frequency with which OE-only, LOC-only, and BE eating episodes occurred also varied across days (range of OE-only episodes per day=01–06 episodes, range of LOC-only eating episodes per day=01–05, range of BE episodes per day=01–05).

3.2. Identification of daily mood trajectories

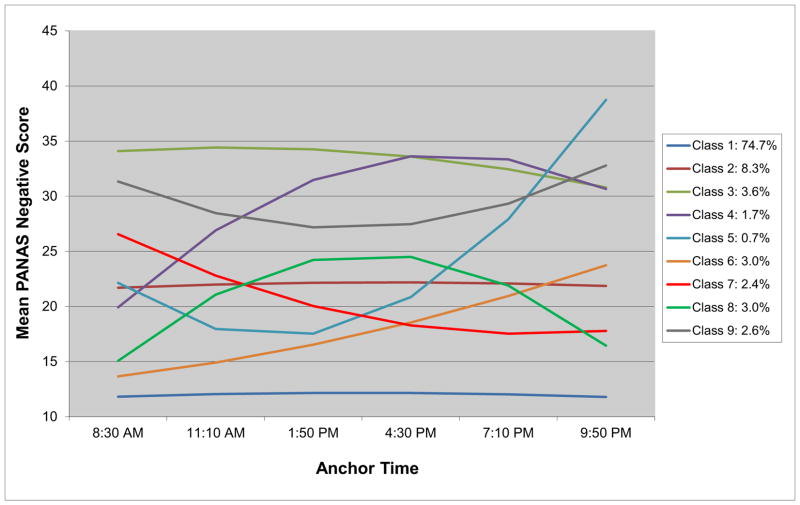

LGMM models using 01- to 10-class solutions were evaluated. All four information criterion indices (AIC, BIC, aBIC, and cBIC) were lowest for a nine-class solution (see Table 01 for fit indices); thus, the nine-class model was selected as the best fitting model of daily mood patterns (see Table 02 for model parameters). Three of the nine classes (Classes 01, 02, and 03) were characterized by stable mood patterns as indicated by non-significant linear and quadratic components. Although these three classes demonstrated similar trajectories of affect over the course of the day, they differed with regard to the magnitude of NA endorsed. Class 01, labeled “Stable Low Negative Affect”, was characterized by low NA throughout the entire day and accounted for the majority of all days classified (74.7%). Class 02, labeled “Stable Moderate Negative Affect”, was characterized by moderate levels of NA over the course of the day and accounted for 08.3% of all days classified. Finally, Class 03, labeled “Stable High Negative Affect”, was characterized by high levels of NA throughout the day and accounted for 03.6% of all days classified. The number of participants who contributed observations to a given class ranged from 4 (Class 5) to 45 (Class 1). See Figure 02 for a graphical representation of the mean NA ratings at each time point for all nine classes.

Table 1.

Model Fit Indices of Latent Growth Mixture Models for 576 EMA Mood Assessment Days.

| Number of Classes | BIC | aBIC | AIC | cAIC | LL | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 17405.35 | 17364.08 | 17348.72 | 17418.35 | −8661.36 | |

| 02 | 17082.63 | 17028.66 | 17008.57 | 17099.63 | −8487.29 | 00.94 |

| 03 | 16863.34 | 16796.67 | 16771.86 | 16884.34 | −8364.93 | 00.96 |

| 04 | 16736.07 | 16656.70 | 16627.16 | 16761.07 | −8288.58 | 00.96 |

| 05 | 16638.56 | 16546.49 | 16512.23 | 16667.56 | −8227.11 | 00.97 |

| 06 | 16567.05 | 16462.29 | 16423.30 | 16600.05 | −8178.65 | 00.97 |

| 07 | 16497.32 | 16379.86 | 16336.15 | 16534.32 | −8131.07 | 00.97 |

| 08 | 16454.19 | 16324.03 | 16275.59 | 16495.19 | −8096.80 | 00.97 |

| 09 | 16375.19 | 16232.34 | 16179.17 | 16420.19 | −8044.58 | 00.97 |

| 10 | 16400.62 | 16245.06 | 16187.17 | 16449.62 | −8044.58 | 00.97 |

Note. Minimum value for each fit index is in boldface. BIC=Bayesian information criterion; aBIC=sample size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion; AIC=Akaike information criterion; cAIC=Consistent Akaike information criterion; LL=log likelihood.

Table 2.

Relative Proportion, Parameter Estimates, and Standard Errors for Nine-Class Latent Growth Mixture Model.

| Class | Description | n(Proportiona) | Intercept

|

Linear

|

Quadratic

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |||

| 01 | Stable Low NA | 430(00.747) | 11.81* | 00.25 | 00.28* | 00.17 | −00.06* | 00.04 |

| 02 | Stable Moderate NA | 048(00.083) | 21.69* | 01.29 | 00.36* | 00.37 | −00.07* | 00.07 |

| 03 | Stable High NA | 021(00.036) | 34.09* | 01.68 | 00.58* | 00.80 | −00.25* | 00.17 |

| 04 | Early Increasing NA | 010(00.017) | 19.92* | 02.79 | 08.19* | 01.00 | −01.21* | 00.20 |

| 05 | Late Increasing NA | 004(00.007) | 22.13* | 02.82 | −06.05* | 01.25 | 01.87* | 00.23 |

| 06 | Gradually Increasing NA | 017(00.030) | 13.65* | 00.63 | 01.05* | 01.02 | 00.19* | 00.25 |

| 07 | Gradually Decreasing NA | 014(00.024) | 26.55* | 02.03 | −04.27* | 00.77 | 00.50* | 00.13 |

| 08 | Inverted U-Shaped NA | 017(00.030) | 15.06* | 01.35 | 07.44* | 00.89 | −01.43* | 00.26 |

| 09 | U-Shaped NA | 015(00.026) | 31.33* | 01.05 | −03.66* | 00.66 | 00.79* | 00.14 |

Note. n=number of days in each class; NA=negative affect; Est.=estimate; SE=standard error.

Proportions based upon most likely latent class membership.

p<00.001

Figure 2.

Latent classes of daily negative affect patterns.

Three classes were classified by increasing NA over the course of the day. Class 04, labeled “Early Increasing Negative Affect,” involved moderate levels of NA which increased to high levels of NA over the first three ratings and then stabilized. Class 04 accounted for 01.7% of all days classified. Class 05, labeled “Late Increasing Negative Affect”, involved moderate levels of NA during the first four ratings of the day, which rapidly increased to high levels of NA by the last rating of the day. Class 05 accounted for 00.7% of days classified. Finally, Class 06, labeled “Gradually Increasing Negative Affect”, appeared to be characterized by low levels of NA at the first daily rating, which gradually increased over the course of the day to moderate levels by the last rating of the day. Although the linear and quadratic components were non-significant, these non-significant findings may be due to a lack of statistical power. Class 06 accounted for 03.0% of all classified days.

One class was characterized by decreasing NA. Class 07, labeled “Gradually Decreasing Negative Affect”, involved moderately high levels of NA which gradually decreased to moderately low levels of NA over the first four daily ratings and then stabilized over the final two daily ratings. Class 07 accounted for 02.4% of classified days. Lastly, two classes were characterized by widely varying levels of NA over the course of the day. Class 08, labeled “Inverted U-Shaped Negative Affect”, involved low levels of NA at the beginning of the day which increased to moderate levels of NA by mid-day and then decreased to low levels of NA by the end of the day. Class 08, labeled “U-Shaped Negative Affect”, involved high levels of NA at the beginning of the day, which decreased to moderately high levels of NA by mid-day, and then increased to high levels of NA by the end of the day. Classes 08 and 09 accounted for 03.0% and 02.6% of classified days, respectively.

3.3. Relationship between affect and eating episodes

There was considerable variability between the nine classes with regard to the mean frequency of overeating (range=00.64–01.59), loss of control eating (range=00.27–01.23), and binge eating episodes (range=00.45–01.50) (see Table 03). General estimating equations (GEE) (Liang & Zeger, 1986) with negative binomial response function were used to compare the mean episodes for each class to the “Stable Low Negative Affect” class (Class 01). Using Class 01 (“Stable Low Negative Affect”) as a reference, significantly more overeating episodes were reported for Class 02 (“Stable Moderate Negative Affect”, M=01.40±00.21), Class 05 (“Late Increasing Negative Affect”, M=1.50±.25), Class 06 (“Gradually Increasing Negative Affect”, M=01.35±00.24), and Class 08 (“Inverted U-Shaped Negative Affect”, M=01.59±00.24) (all ps<.005). Similarly, when compared to Class 01, significantly more binge eating episodes were reported for Classes 02 (“Stable Moderate Negative Affect”, M=01.29±00.23), 03 (“Stable High Negative Affect”, M=01.35±00.28), 05 (“Late Increasing Negative Affect”, M=01.50±00.25), 06 (“Gradually Increasing Negative Affect”, M=02.06±00.27), and 09 (“U-Shaped Negative Affect”, M=01.09±00.20) than Class 01 (all ps<.005). With regard to the frequency of loss of control eating episodes, there were no significant differences between Class 01 and the other classes.

Table 3.

Overeating, Loss of Control Eating, and Binge Eating Episodes by Daily Mood Patterns

| Class | Description | Overeating Episodes

|

Loss of Control Eating Episodes

|

Binge Eating Episodes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | ||

| 01 | Stable Low NAa | 00.65* | 00.10 | 00.72* | 00.15 | 00.45* | 00.08 |

| 02 | Stable Moderate NA | 01.40* | 00.21 | 00.80* | 00.08 | 01.36* | 00.22 |

| 03 | Stable High NA | 01.35* | 00.28 | 00.53* | 00.15 | 01.35* | 00.28 |

| 04 | Early Increasing NA | 01.10* | 00.35 | 00.90* | 00.40 | 01.00* | 00.37 |

| 05 | Late Increasing NA | 01.50* | 00.25 | 00.75* | 00.41 | 01.50* | 00.25 |

| 06 | Gradually Increasing NA | 01.35* | 00.24 | 00.76* | 00.20 | 01.29* | 00.23 |

| 07 | Gradually Decreasing NA | 00.85* | 00.26 | 01.23* | 00.31 | 00.85* | 00.26 |

| 08 | Inverted U-Shaped NA | 01.59* | 00.24 | 00.29* | 00.15 | 01.18* | 00.40 |

| 09 | U-Shaped NA | 01.18* | 00.24 | 00.27* | 00.08 | 01.09* | 00.20 |

Note: M=mean number of eating episodes per day by latent class, SE=standard error, NA=negative affect

Class 01 was used as a reference by which to compare all other classes

p<00.01

4. Discussion

The first objective of the current study was to identify daily patterns of NA among obese individuals. A nine-class solution provided the best fit for these data which replicated a nine-class solution found in a previous sample of adult women with BN. Furthermore, the nine daily patterns of NA that were identified in the current sample closely correspond to the daily patterns of NA identified in women with BN (Crosby et al., 2009). The second objective of the study was to examine whether daily patterns of NA were differentially related to the frequency of OE-only, LOC-only, and BE episodes. It was hypothesized that more LOC-only and BE episodes would occur on days characterized by high or increasing NA. These hypotheses were partially supported by the data. The results indicate that days characterized by high or increasing NA were associated with more frequent OE-only and BE episodes than days characterized by low NA and that daily affect patterns were not differentially related to LOC-only episodes. These findings contradict previous OBE investigations (Goldschmidt et al., 2012) that demonstrated a relationship between increased NA and loss of control eating, but not overeating or binge eating. However, these data replicate findings from previous LGMM research in BN (Crosby et al., 2009).

Differences between the findings of the current study and those of previous investigations might be explained by the differences in the methodologies used across studies. For example, whereas most previous investigations defined overeating objectively (e.g., setting a threshold for the number of kilocalories consumed); in this study, overeating was self-rated and self-defined. Thus, in the current study, overeating episodes may be more representative of eating episodes that were perceived as episodes of overeating rather than eating episodes during which an objectively large amount of food was consumed. It is unclear whether the perception of overeating accurately reflects eating episodes in which the amount of energy intake is objectively large. It may be that the extent to which an eating episode is perceived as overeating is impacted by other variables, such as the type of food consumed, the timing of the eating episode, and/or situational/contextual factors surrounding the eating episode. Thus, it could be that there is a relationship between NA and the subjective experience of overeating, but no relationship between NA and objectively defined overeating. The differences between the results of the current study and those of previous OBE investigations could also be explained by the use of different statistical methodologies. Whereas previous investigations have largely examined the relationship between OBE and NA at single points in time, the current study examined the relationship between OBE and the trajectory of NA over the entire day. Thus, it could be that loss of control eating is associated with momentary levels of NA whereas overeating and binge eating are associated with the overall pattern of NA during the day.

4.1. Implications

These results indicate that daily patterns of NA may act as an antecedent to overeating and binge eating among obese individuals. The similarity between the findings from the current study, which used a nonclinical sample of obese adults, and findings from a previous LGMM investigation that used a sample of women with BN suggests a functional relationship between affect and eating behaviors that is broadly applicable and not unique to individuals with eating disorders. As a result, targeting “problematic affect days” in treatment may be an effective approach to reducing, and potentially preventing, the occurrence of OE-only and BE episodes among obese individuals. To this end, clinicians may consider utilizing emotion-focused psychological treatments such as dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Telch et al., 2001), integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT; Wonderlich et al., 2013), and integrative response therapy (IRT; Robinson, 2013), which have demonstrated efficacy at reducing binge eating among individuals with eating disorders.

It may be argued that a nine-class solution is not parsimonious and may be difficult to apply in clinical settings. The fact that three classes were characterized by stable NA (i.e., Classes 1, 2, and 3) may appear to bolster this argument. However, the fact that a similar nine-class solution (including three classes that are identical to Classes 1, 2, and 3 in the current study) was found in a sample of women with bulimia nervosa (Crosby et al., 2009) suggests that this model is neither unique nor unnecessarily complex. Additionally, it is important to note that these data do not suggest that each participant experienced all nine patterns of daily affect nor do they suggest that a nine-class solution will be relevant to a specific individual seeking treatment for OBE. Rather, these data suggest that daily patterns of affect among individuals with obesity can be categorized into one of these nine classes and that these classes differentially predict the frequency of OE-only and BE episodes. Furthermore, given the consistency of the findings from the GEE analyses (i.e., there was only an increased frequency of OE-only and BE episodes on days characterized by elevated or increasing NA), it may not be necessary to apply the full nine-class solution in a clinical setting. It may be enough to discuss the relevance of daily patterns of NA to eating behaviors and identify days characterized by elevated or increasing NA as targets for treatment.

It is interesting to note that in the current sample, the majority of days were characterized by stable levels of low NA, which indicates that, on most days, participants did not report elevated or fluctuating levels of NA. Although it should be noted that the absence of NA does not necessarily indicate the presence of positive affect, understanding that days characterized by elevated levels of or fluctuating NA are relatively uncommon in this group may help clinicians identify and target “problematic affect days” more effectively. Lastly, although OE-only and BE episodes occurred more frequently on elevated or increasing NA days, it is important to note that OE-only and BE episodes were not absent on days characterized by stable low NA. This finding suggests that other variables (e.g., caloric restriction, positive affect, situational factors, food availability and palatability) may also be related to the frequency of OE-only and BE episodes and may need to be targets of treatment as well.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

There were several strengths to the methodology used in the current study. First, although using LGMM in psychological research is not a novel technique in and of itself, this investigation is one of the first studies to use LGMM to examine daily affect patterns in the context of eating patterns in obesity. Second, the use of EMA data not only reduces the risk of retrospective recall bias, but it may also be more ecologically valid than assessing affect and behavior in a laboratory setting. Third, the use of palmtop computers to collect EMA data allows for a time-stamp to be attached to each assessment point. Without time-stamps, it can be difficult to guarantee that assessments were completed when they were supposed to be and as a result, it can be almost impossible to examine temporal relationships between variables with accuracy. Fourth, both features of binge eating (i.e., overeating and loss of control) were assessed independently of one another, which allowed for separate analyses of OE-only, LOC-only, and BE episodes. Finally, the inclusion of participants who were not seeking treatment and the inclusion of participants who did not endorse binge eating at baseline enhanced the potential generalizability of the findings.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be noted. First, the use of LGMM in this context is limited because it identifies classes of affect days under the assumption that the pattern on daily affect on one day is independent from the patterns of daily affect on all other days. However, it is possible that what happens on one day affects what happens on the next day. Given this possibility, two additional analyses were conducted. First, the class on “day 1” was used to predict the class on “day 2”. Second, the class on “day 1” was used to predict the eating behaviors (OE-only, LOC-only, and BE episodes) on “day 2”. These analyses were all statistically significant with the exception that class on “day 1” did not predict frequency of OE-only episodes on “day 2”. Overall, these data suggest that the daily pattern of affect on one day does impact both the daily pattern of affect and eating behaviors on the next day. The implications of these data are two-fold. First, these findings provide further evidence for the clinical relevance of these classes. Second, they suggest that future research must examine trajectories of NA over longer periods of time and not simply look at individual days in isolation.

Second, it has been noted that LGMM analyses may be limited by the “cat’s cradle” effect (Sher et al., 2012), which is the potential for LGMM models to identify the same number of classes across different datasets. The cat’s cradle effect was first noted in the substance use literature, with LGMM analyses consistently finding four trajectories of alcohol use patterns (i.e., high use, low use, increasing use, decreasing use) regardless of the characteristics of the sample (e.g., age) and methodology used (e.g., length of follow-up). It has been hypothesized that the cat’s cradle effect reflects the tendency for LGMM analyses to simply identify all possible trajectories (Sher et al., 2012). However, it is notable that although the current study replicated a nine-class solution in a BN sample, there were some differences in the specific classes identified (e.g., the current sample identified only one trajectory that represented a decrease in NA whereas the previous study identified two decreasing trajectories). Additionally, a similar LGMM study in a sample of women with anorexia nervosa (Lavender et al., in press) identified a seven-class solution rather than a nine-class solution. Together, these findings suggest that the current analyses may be less susceptible to the cat’s cradle effect than studies on the course of alcohol use over time.

Third, although overeating and loss of control were assessed independently of one another, these variables were self-rated by the participants. As stated above, overeating in the current study may be more reflective of perceived overeating than objective overeating defined by excessive food consumption. Second, although previous research suggests that EMA procedures are not reactive, it is possible that self-monitoring NA and eating episodes may impact how affect and eating are experienced and thus how these variables were rated. Third, the majority of participants were Caucasian females, which may diminish the generalizability of the findings. Finally, although these data suggest a relationship between NA and OE-only and BE episodes, these data cannot be used to establish a causal relationship between these variables.

4.3. Conclusions

These data suggest that in obese individuals, daily patterns of NA characterized by high or increasing NA may be associated with higher frequencies of OE-only and BE episodes than those characterized by low NA. These results suggest that identifying and targeting “problematic affect days” in treatment may be an effective approach to reducing the frequency of OE-only and BE episodes among obese individuals. However, given that OE-only and BE episodes were not absent on days characterized by stable low NA, additional research is needed to examine other possible antecedents of OE-only and BE episodes (e.g., dietary restriction, positive affect). Future researchers should also examine whether patterns of NA over longer periods of time (e.g., multiple days, week) are associated with increased frequencies of OE-only and BE episodes. Finally, additional research is needed to determine whether perceived overeating reflects objective overeating that is defined in terms of kilocalories consumed.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Nora Durkin, M.A. and Heather Beach, M.P.H. for their help with data collection. This research was supported by grants from NIDDK (P30DK 50456) and NIMH (T32 MH082761-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agras WS, Telch CF. The effects of caloric deprivation and negative affect on binge eating in obese binge-eating disordered women. Behavior Therapy. 1998;29:491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum principle. 2nd International Symposium on Information Theory; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR) Washington, D.C: APA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arnow B, Kenardy J, Agras WS. Binge eating among the obese: a descriptive study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;15:155–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00848323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow B, Kenardy J, Agras WS. The emotional eating scale: The development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1995;18:79–90. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199507)18:1<79::aid-eat2260180109>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdogman H. Model selection and akaike’s information criterion: the general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika. 1987;52:345–370. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Simmonich H, Smyth J, Mitchell JE. Daily mood patterns and bulimic behaviors in the natural environment. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2009;47:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan M, Mitchell JE, Seim HC, Specker SM, Pyle RL, Raymond NC, Crosby RD. Eating related and general psychopathology in obese females with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1994;15:43–52. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199401)15:1<43::aid-eat2260150106>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured clinical interview for the DSM-IV axis I disorders - patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; Biometrics Research Department; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfein JA, Walsh BT, LaChaussee JL, Kissileff HR, Devlin MJ. Eating behavior in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;14:427–431. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199312)14:4<427::aid-eat2260140405>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, Le Grange D, Mitchell JE. Momentary affect surrounding loss of control and overeating in obese adults with and without binge eating disorder. Obesity. 2012;20:1206–1211. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt AB, Le Grange D, Powers P, Crow SJ, Hill LL, Peterson CB, Mitchell JE. Eating disorder symptomatology in normal-weight vs. obese individuals with binge eating disorder. Obesity. 2011;19:1515–1518. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeno CG, Wing RR, Shiffman S. Binge antecedents in obese women with and without binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu LKG, Mulliken B, McDonagh B, Krupa Das S, Rand W, Fairburn CG, Roberts S. Binge eating disorder in extreme obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2002;26:1398–1403. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61(348):358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavender JM, De Young KP, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Mitchell JE, Le Grange D. Daily patterns of anxiety in anorexia nervosa: associations with eating disorder behaviors in the natural environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0031823. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D, Gorin A, Catley D, Stone AA. Does momentary assessment detect binge eating in overweight women that is denied at interview? European Eating Disorders Review. 2001;9:309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitundinal analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Khoo ST. Longitudinal studies of achievement growth using latent variable modeling. Learning and Individual Differences. 1998;10:73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Muthen LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen B. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Muthen & Muthen; 1999–2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, DeSarbo W, Reibstein D, Robinson W. An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science. 1993;12:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson A. Integrative response therapy for binge eating disorder. Cognitive and behavioral practice. 2013;20:93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Sclove LS. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52:333–343. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Jackson KM, Steinley D. Alcohol use trajectories and the ubiquitous cat’s cradle: cause for concern? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;120:322–335. doi: 10.1037/a0021813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Stone AA, Hufford MR. Ecological momentary assessment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2008;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1994;16:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Elder KA, Brownell KD. Binge eating in an obese community sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;23(27):37. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199801)23:1<27::aid-eat4>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale JD, Fogarty SJ. Differential effects of induced mood on retrieval of pleasant and unpleasant events from episodic memory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1979;88:248–257. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.88.3.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch CF, Agras WS, Linehan MM. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1061–1065. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch CF, Pratt EM, Niego SH. Obese women with binge eating disorder define the term binge. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;24:313–317. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199811)24:3<313::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadden TA, Foster GD, Letizia KA, Wilk JE. Metabolic, anthropometric, and psychological characteristics of obese binge eaters. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1993;14:17–25. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199307)14:1<17::aid-eat2260140103>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The panas-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule - expanded form. The University of Iowa; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler L, Reis HT. Self-recording of everyday life events: origins, types, and uses. Journal of Personality. 1991;59:339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Peterson CB, Crosby RD, Smith TL, Klein MH, Mitchell JE, Crow SJ. A randomized controlled comparison of integrative cognitive-affective therapy (ICAT) and enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT-E) for bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine. 2013;23:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovski SZ, Leet M, Yanovski JA, Flood M, Gold PW, Kissileff HR, Walsh BT. Food selection and intake of obese women with binge-eating disorder. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1992;56:975–980. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.6.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]