Abstract

Children with early surgery for congenital heart disease (CHD) are known to have impaired neurodevelopment; their performance on school-age achievement tests and their need for special education remains largely unexplored. The study aimed to determine predictors of academic achievement at school-age and placement in special education services among early CHD surgery survivors. Children with CHD surgery at <1 year of age from 1/1/1998─12/31/2003 at the Arkansas Children’s Hospital were identified. Out-of-state births and infants with known genetic and/or neurologic conditions were excluded. Infants were matched to an Arkansas Department of Education database containing standardized assessments at early school-age and special education codes. Predictors for achieving proficiency in literacy and mathematics and the receipt of special education were determined. 256 children who attended Arkansas public schools and had surgery as infants were included; 77.7% had either school-age achievement-test scores or special education codes of mental retardation or multiple disabilities. Scores on achievement tests for these children were 7–13% lower than Arkansas students (p<0.01). They had an 8-fold increase in the receipt of special education due to multiple disabilities (OR 10.66, 95% CI 4.23─22.35) or mental retardation (OR 4.96, 95% CI 2.6─8.64). Surgery after the neonatal period was associated with reduced literacy proficiency and cardiopulmonary bypass during the first surgery was associated with reduced mathematics proficiency. Children who had early CHD surgery were less proficient on standardized school assessments and many received special education. This is concerning since achievement- test scores at school-age are “real-world” predictors of long-term outcomes.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, congenital heart surgery, academic achievement, special education

Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) affects 6─8 per 1,000 live births annually in the U.S. and many are operated on before their first birthday [1, 2]. Infants with CHD are at high risk for neurodevelopmental delays, and sometimes require several surgeries during early childhood that may compound this risk [3–6]. The American Heart Association recently proposed that infants with CHD surgery are at increased risk for impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes and should be evaluated throughout childhood [7].

Early heart surgery impacts neurologic outcome and academic performance [8, 9]. Gross and fine motor impairments are frequently evident in childhood following CHD surgery [8, 10–12]. Neurodevelopmental tests at 1 year likely underestimate the risk of poor school achievement [13], as >50% have neurodevelopmental impairments at school age [14]. While intelligence quotients are in the normal range, they score below age-matched controls on executive functions at early school-age [15]. CHD children also have a high prevalence of hyperactivity, inattention, and other learning problems, with up to 50% receiving additional academic services [16]. Impairments in executive functioning become apparent later in childhood affecting quality-of-life measures [15, 17, 18]. There is also an estimated 10% reduction in the completion of schooling [19]. Proposed risk factors for neurodevelopmental delays include: earlier surgery [12], younger gestational age [20], preoperative acidosis and hypoxia [14, 21], type of CHD [22], and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) [5]. The problem is likely multi-factorial [11].

Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH) is the only pediatric hospital in the state and cares for the majority of Arkansan children with CHD and maintains a database of all CHD surgeries. By matching data from the ACH CHD database with achievement test scores and special education codes from the Arkansas Department of Education (ADE) longitudinal student database a unique study was performed [23, 24]. We sought to determine predictors of achieving proficiency (scores at ≥grade-level) on statewide achievement-tests at early school-age for children who had CHD surgery during infancy, by linking data from these two databases and comparing these children with the general Arkansas public school student population. We hypothesized that children with CHD would be less proficient and would receive more special education than average Arkansas students.

Material and Methods

Study Design

Following institutional review board approval, all infants who had surgery at ACH for CHD during the first year of life from 1/1/1998─12/31/2003 were identified from the Cardiac Surgery Outcomes and the Society for Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery databases. Corresponding medical records were abstracted. Infants were excluded if their birth weight was <1500 grams, if they only had a patent ductus arteriosus ligation, or only had non-CHD surgery.

Demographic data collected included the infants’ name, date of birth, social security number, gender, race, mothers’ name, state citizenship, and mortality date (if applicable). Age at surgery, weight at surgery, receipt (and duration) of CPB, surgery date, CHD operation duration, length of stay, CHD diagnosis, type of CHD surgery, associated Risk Adjustment for Congenital Heart Surgery (RACHS-1) category [25], and known genetic and/or neurologic conditions were recorded. Since ACH is a tertiary care center without an inborn delivery service, birth weight, gestational age, and Apgar scores were abstracted when available. CHD type was divided into 4 categories: left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO, which included interrupted aortic arch type A, aortic stenosis, coarctation, and hypoplastic left heart syndrome), right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO, which included pulmonary atresia, Ebstein’s anomaly, tricuspid atresia, and pulmonary valve stenosis), conotruncal defects (which included interrupted aortic arch type B, truncus arteriosus, dextro-transposition of the great arteries, tetralogy of Fallot, and double outlet right ventricle), and others (i.e., anomalous pulmonary venous return, atrioventricular septal defects, ventricular and atrial septal defects, heterotaxy, and complex [typically 3 or more major phenotypes]) [26].

The Arkansas Department of Health verified subjects’ social security numbers. The final dataset was only Arkansas-born subjects who had CHD surgery as infants and later attended Arkansas public schools.

Arkansas Department of Education (ADE)

The compiled dataset was securely transmitted to the ADE. Social security numbers, dates of birth, and mothers’ names were used to match infant data to education records. Once matching was complete, a unique study identifier was created by the ADE and all personal health information was removed, creating a de-identified dataset. A Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) waiver was obtained from the ADE.

The ADE database contains data for children who attend public schools in Arkansas. Children who were home-schooled, attended private school, had moved out-of-state, or were residents of another state would not match, and were therefore excluded from the analysis. For each subject, the ADE provided scores on the Arkansas Augmented Benchmark Examinations [23, 24] (annual achievement tests taken by all Arkansas public school students, grades 3─8) and if the subject received special education, the reason code. The available grade data were dependent on the subject’s birth year and current grade-level during the 2011─2012 school year. Not all matched subjects had achievement tests performed, as up to 5% of children at each school may not take the examination, so only other ADE data would be known.

Scores are designated by the ADE as advanced, proficient, basic, or below basic. A proficient or advanced score represents performance at or above grade-level, respectively (i.e., “proficient”); basic and below-basic scores represent performance below grade-level (i.e., “not proficient”). Grades 3 and 4 were used as the “early school-age” assessments because these were the earliest grades that have proficiency designations associated with the annual assessments and are grades in which more complex use of basic skills are required. Further detail regarding the achievement tests is in the online Supplemental Material.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic variables and clinical features were summarized by those subjects having early school-age assessments or identified as requiring special education secondary to mental retardation or multiple disabilities (CHD study cohort) versus those missing early-school age assessments but still having ADE records (partial data CHD cohort). Available demographic data in the Arkansas public school population was compared to the CHD cohort using data available on the ADE and Arkansas Research Center’s websites [23, 24]. Demographic and clinical similarity between groups was estimated using equivalence tests assuming a 20% margin, estimating any selection bias introduced by the matching process [27–29].

The primary outcome was defined based upon a subject achieving proficiency on early school-age assessments or a subject requiring special education due to cognitive impairment. Subsequently, literacy and mathematics primary outcomes were dichotomized as a negative outcome (defined as not proficient and/or receipt of special education due to cognitive impairment) or a positive outcome (defined as proficient and not receiving special education due to cognitive impairment). Other reasons for special education (e.g., specific learning disabilities) were not combined with the primary negative outcome, as they do not clearly represent a cognitive impairment.

To determine risk factors associated with the primary outcome, logistic regression models for proficiency in literacy and mathematics at early school-age accounting for repeated measurements were developed. An unstructured correlation was assumed between the repeated assessments made on a given subject. Explanatory variables included in the regression model (Table 4), were selected due to clinical relevance. Underlying distributions of explanatory variables were examined and appropriate transformations were used to restrict the influence of extreme observations.

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Predictor Variables for Literacy and Mathematics Models

| Literacy |

Mathematics |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p | ||

| Number of Surgeries | 0.357 | 0.803 | |||||

| One | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| Multiple | 0.68 | (0.31, 1.53) | 1.11 | (0.48, 2.56) | |||

| Age at Surgery a | 0.004 | 0.113 | |||||

| Infant | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| Neonate | 3.42 | (1.47, 7.97) | 2.04 | (0.84, 4.91) | |||

| Gender | 0.395 | 0.066 | |||||

| Female | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| Male | 0.78 | (0.44, 1.39) | 1.75 | (0.96, 3.19) | |||

| Race | <0.001 | 0.001 | |||||

| Non-white | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| White | 3.27 | (1.74, 6.12) | 3.03 | (1.60, 5.71) | |||

| Cardiopulmonary Bypass | 0.110 | 0.046 | |||||

| No | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| Yes | 0.48 | (0.20, 1.18) | 0.38 | (0.15, 0.98) | |||

| Diagnosis Group b | 0.487 | 0.250 | |||||

| Conotruncal | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| LVOTO | 0.95 | (0.39, 2.32) | 1.24 | (0.50, 3.12) | |||

| Otherc | 1.67 | (0.70, 3.96) | 2.46 | (0.99, 6.11) | |||

| RVOTO | 1.25 | (0.42, 3.71) | 1.22 | (0.39, 3.80) | |||

| RACHS-1 Category b | 0.539 | 0.231 | |||||

| [1–2] | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| [3–4] | 1.45 | (0.63, 3.35) | 1.71 | (0.72, 4.06) | |||

| [5–6] | 0.81 | (0.18, 3.66) | 0.81 | (0.17, 3.72) | |||

| Not Classified | 1.27 | (0.16, 9.90) | 1.16 | (0.17, 8.03) | |||

| Weight at Surgery | 0.062 | 0.145 | |||||

| 25th Q. (3.3 kg) | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| 75th Q. (5.7 kg) | 1.75 | (0.97, 3.13) | 1.58 | (0.86, 2.91) | |||

| Total Time In Surgery | 0.225 | 0.130 | |||||

| 25th Q. (155 min) | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| 75th Q. (315 min) | 1.5 | (0.78, 2.89) | 1.74 | (0.85, 3.54) | |||

| Length of Stay | 0.026 | 0.026 | |||||

| 25th Q. (7 days) | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| 75th Q. (25 days) | 0.54 | (0.32, 0.93) | 0.54 | (0.31, 0.93) | |||

| Grade Level | 0.005 | 0.252 | |||||

| 3 | [REFERENCE] | [REFERENCE] | |||||

| 4 | 1.44 | (1.12, 1.86) | 0.87 | (0.69, 1.10) | |||

| Concordance Statistic d | 0.73 | (0.67, 0.79) | 0.74 | (0.67, 0.81) | |||

CI — Confidence Interval; LVOTO — left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; RVOTO — right ventricular outflow tract obstruction; RACHS — Risk Adjustment Congenital Heart Surgery

Infant is >28 days of age at 1st surgery, Neonate is ≤28 days of age at 1st surgery

Deviance test reported

Other diagnosis group includes types of congenital heart disease which do not have an associated RACHS-1 category, i.e. heart transplant.

Concordance statistic assesses predictive accuracy of model and is equal to the area-under-the-curve (AUC) in logistic regression [40]

To estimate the difference between the CHD Study cohort and the overall early school-age population, proficiency rates in literacy and mathematics at early school-age were estimated by year using logistic regression. The estimated CHD study cohort proficiency at each year was compared to state data at each year and then evaluated using an overall simultaneous test of independence. Stata 12.1 (College Station, TX) and R 2.15.1 (Vienna, Austria) were used.

Results

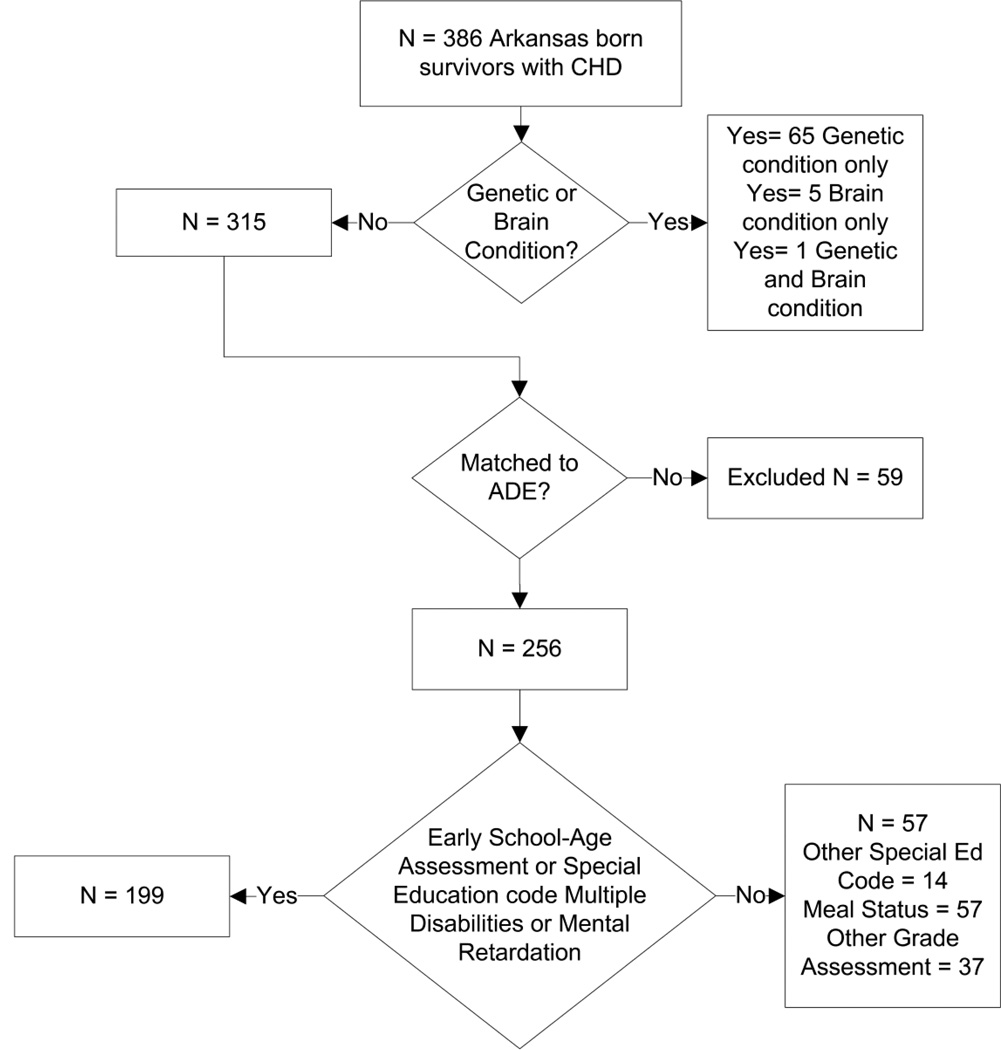

The descriptive characteristics of 256 infants who met inclusion criteria are described in Table 1. The majority (77.7%) had early school-age assessments or a special education code of mental retardation or multiple disabilities and formed the CHD study cohort (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Summary of Demographics and Clinical Features by Study Status

| CHD Study Cohorta N = 199 n (%) |

Partial Data CHD Cohortb N = 57 n (%) |

Total CHD Cohortc N = 256 n (%) |

Pi | Psd | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <0.001 | 0.057 | |||

| Female | 83 (42) | 19 (33) | 102 (40) | ||

| Male | 116 (58) | 38 (67) | 154 (60) | ||

| Race | <0.001 | 0.148 | |||

| Non-white | 64 (32) | 11 (19) | 75 (29) | ||

| White | 135 (68) | 46 (81) | 181 (71) | ||

| Age in Days at Surgerye | 9 57 154 | 8 19 93 | 9 45 148 | <0.001 | 0.092 |

| Weight At Surgery (kg)e | 3.4 4.3 5.7 | 3.1 3.6 5.6 | 3.4 4.1 5.7 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Number of Surgeries | 0.002 | <0.001 | |||

| One | 150 (75) | 42 (74) | 192 (75) | ||

| Multiple | 49 (25) | 15 (26) | 64 (64) | ||

| Cardiopulmonary Bypass | 0.168 | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 127 (64) | 29 (51) | 156 (61) | ||

| No | 72 (36) | 28 (49) | 100 (39) | ||

| Diagnosisf | |||||

| Conotruncal | 58 (29) | 17 (30) | 75 (29) | 0.005 | 0.009 |

| LVOTO | 48 (24) | 19 (33) | 67 (26) | <0.001 | 0.205 |

| RVOTO | 20 (10) | 11 (19) | 31 (12) | <0.001 | 0.056 |

| Other | 73 (37) | 10 (18) | 83 (32) | 1.00 | <0.001 |

| Apgar Scores 5 Minuteseg | 8.0 9.0 9.0 | 7.8 8.5 9.0 | 8.0 9.0 9.0 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Gestational Age at Birth (weeks)eh | 38 39 40 | 38 39 40 | 38 39 40 | <0.001 | 0.132 |

| Birth Weight (kg)ei | 3.0 3.3 3.6 | 2.8 3.0 3.5 | 2.9 3.2 3.5 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

LVOTO ─ left ventricular outflow tract obstruction; RVOTO ─ right ventricular outflow tract obstruction

Subjects with Grade 3─4 assessments or a special education code of multiple disabilities or mental retardation

Subjects who either did not match to the ADE database or that matched to in-complete ADE data

Subjects who met inclusion criteria and were submitted to the ADE to match to assessment data

Equivalence indicated if Inferiority (Pi) and Superiority (Ps) tests were simultaneously rejected. α 0.025

Lower Quartile, Median, Upper Quartile reported. Otherwise, n (column %) reported

Bonferroni adjusted P-values

Data available for 105 subjects

Data available for 139 subjects

Data available for 134 subjects

Fig. 1. CHD Cohort “N” Diagram.

One hundred ninety-nine (199) of 256 infants (77.7%) with early CHD surgery had either an early school-age assessment or a special education code of mental retardation or multiple disabilities and were labeled as the CHD Study Cohort.

Twenty-eight percent (73/256) of CHD infants did not have early school-age achievement-test scores. Having a special education code was associated with not having an early school-age assessment (p <0.001), as 41% (30/73) that did not have an assessment had a special education code. A special education code was reported in 26.2% (67/256) of CHD infant-student pairs, which is more than the 10.3% (53,842/523,167) of all Arkansas public school students who received special education (odds ratio [OR] 3.09, 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.3, 4.1). The OR of receiving special education for mental retardation in CHD subjects compared to Arkansas students was 4.96 (95% CI 2.6, 8.64). Similarly, CHD infants had higher odds of receiving special education due to multiple disabilities (OR 10.66, 95% CI 4.23, 22.35). Of the 20 subjects who received special education for mental retardation (n = 13) or multiple disabilities (n = 7), 4 took early school-age achievement tests, and all were not proficient.

One-hundred ninety-nine (199) CHD subjects had either early school-age assessments (n = 183) or a special education code of mental retardation or multiple disabilities (n = 20, 4 also had early school-age assessments) and were included in the model as the CHD Study Cohort (Figure 1). The study cohort was equivalent within a 20% margin to the 57 subjects who matched only to other ADE data for weight at surgery, number of surgeries, and conotruncal diagnosis category (Table 1) [27–29]. The CHD study cohort had similar gender and race compared to the Arkansas public school population, but a difference in meal-status (Table 2). The mean percent of CHD subjects achieving proficiency was different from the state proficiency averages (for literacy and mathematics at early school-age, p <0.05 (Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison between CHD Study Cohort and All Arkansas Public School Students for Academic Year 2011─2012

| CHD Study Cohort N = 199 n (%) |

State Academic Year 2011─2012 N = 523,167 n (%) |

Pi | Ps a | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 83 (42) | 255,208 (49) | |||

| Male | 116 (58) | 267,959 (51) | |||

| Race | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Non-white | 64 (32) | 185,735 (36) | |||

| White | 135 (68) | 337,432 (64) | |||

| Meal Statusb | <0.001 | 0.987 | |||

| Free | 42 (21) | 261,903 (51) | |||

| Reduced | 23 (12) | 46,029 (9) | |||

| Full-Price paid | 134 (67) | 204,619 (40) | |||

| Special Education Codec | <0.001 | ||||

| Autism | 0 (0) | 3,363 (0.64) | |||

| Multiple disabilitiesd | 7 (4) | 1,376 (0.26) | <0.001 | ||

| Mental retardationd | 13 (7) | 5,585 (1.1) | <0.001 | ||

| Other health impairments | 15 (8) | 9,417 (1.8) | |||

| Speech language impairments | 4 (2) | 14,643 (2.8) | |||

| Specific learning disabilities | 14 (7) | 18,220 (3.5) | |||

| Other | 1,777 (0.34) | ||||

| None | 146 (73) | 468,786 (90) |

Equivalence indicated if Inferiority (Pi) and Superiority (Ps) tests were simultaneously rejected, α 0.025

Full-Price vs. Other. For the State, the total number of students is 512,551 since the meal status is recorded at a different time of year than the assessment data

Chi-Square Test of Independence reported for No special education code vs. any special education code comparison

Bonferroni-corrected Test of Proportions reported for each special education code

Table 3.

Comparison of Congenital Heart Disease (CHD) Cohort to Arkansas State Proficiency

| CHD Study Cohort | State Proficiency | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proficiency | Na | 95% Confidence Interval |

Mean (SD) Age in years |

Averageb | p value | |

| Grade 3 Literacy | 0.54 | 183 | (0.46, 0.62) | 9.2 (0.5) | 0.67 | 0.004 |

| Grade 4 Literacy | 0.66 | 151 | (0.50, 0.74) | 10.2 (0.6) | 0.73 | 0.002 |

| Grade 3 Mathematics | 0.71 | 182 | (0.64, 0.78) | 9.2 (0.5) | 0.73 | 0.006 |

| Grade 4 Mathematics | 0.68 | 150 | (0.60, 0.76) | 10.2 (0.6) | 0.79 | 0.005 |

N is the number of CHD subject values

Scores from testing years 2007–2011

In the literacy logistic regression model, age at surgery, race, and length of stay for the first hospitalization were significant predictors for achieving proficiency (Table 4). In the mathematics logistic regression model, race, CPB, and length of stay for the first hospitalization were predictors for proficiency at early school-age (Table 4). For both models, gender, having 1 or ≥2 surgeries, the type of CHD, RACHS-1 category, weight at surgery, and the total surgical time at the first surgery were not predictive of achieving proficiency (Table 4).

Discussion

In this CHD cohort, average proficiency at early school-age in literacy and mathematics achievement tests was up to 13% lower than the state population (p <0.01, overall). These infants also received any type of special education and had an 8-fold increase in receiving special education due to mental retardation or multiple disabilities, compared to Arkansas school students. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to evaluate standardized achievement tests in a large cohort of children from a single state with CHD surgery during infancy. Important strengths of the study include: 1) most Arkansas infants with CHD are cared for and operated on at ACH; 2) the ADE has the mission of sharing educational data with researchers to improve educational outcomes in Arkansas; 3) the match rate of infants with CHD to educational data was high; and 4) “real world” assessments that correlate with long-term economic outcomes were used [30, 31]. Since children with genetic and/or brain conditions were excluded, the study results represent a cohort of CHD children whose lower achievement-test scores were likely due to their CHD, treatment, and/or surgery regimens, further enhancing the significance of the findings. Moreover, the state data used for comparison included children with genetic and/or neurologic conditions, making the high rate of poor achievement-test performance in the CHD children even more concerning.

A surprising observation was that children who had their first CHD surgery during the first 28 days of life were more proficient on literacy at early school-age compared to those operated on after the neonatal period (OR 3.42). Although it is unclear when it is best to operate, the timing of surgery is impacted by the type of CHD, clinical condition of the infant, and physician preference. It has been hypothesized that performing surgery too early may be harmful to the developing brain [32]; however, based on our findings, later surgery may have its own set of consequences. Hypoxemia is one mechanism for preoperative brain injury [21]. Perhaps, correcting the anatomic reason for hypoxemia and impaired cerebral blood flow earlier may allow for improved brain growth and development, which occurs rapidly throughout infancy. Well-designed, randomized clinical studies comparing timing of surgery for particular lesions are clearly needed.

Overall, the CHD study cohort performed below the state proficiency average in both literacy and mathematics. This is consistent with a Danish study showing that individuals with CHD had lower educational achievement by ~10% [19]. Surprisingly, in our cohort, type of CHD and associated-RACHS-1 categories, which are linked to the surgical procedure and often its timing, were not predictive of achieving proficiency. RACHS-1 categories are a widely used consensus-based risk stratification for CHD infants, with higher categories corresponding to surgeries with a higher risk of death [25, 33]. However, no association between heart lesion and school outcome was found in our cohort (p = 0.250). It is important to note that cognitive changes in infants with CHD can be a result of genetic conditions, intrauterine insults, pre-operative insults, intra-operative injury, post-operative injury, medical comorbidities, and necessary mechanical support and its duration [7].

Infants who received CPB were about half as likely to achieve proficiency in mathematics compared to those who did not receive CPB (p = 0.046). For literacy proficiency, however, CPB as a predictor did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.110). CPB is known to have effects on the developing brain and can contribute to brain injury in the form of white matter changes and atrophy [34–37].

The study found a high rate of special education among children who were operated on during infancy, almost 3-fold higher than the general public school population. A novel finding of this study is that 30% of CHD children receiving special education do so because of mental retardation or because of multiple disabilities; this is significantly greater than the 12.9% of Arkansas public school students receiving special education due to these reasons. These two reasons for special education were specifically chosen to be included as a negative outcome because they clearly represent cognitive impairment, while the presence of a specific learning disability or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder does not necessarily mean the subject is cognitively impaired. The effects of this outcome on quality of life, the economic impact to the family and child, and society in general are substantial. In fact, the rate would be even higher if the CHD subjects were compared to Arkansas children who did not have a genetic and/or brain condition. By itself, this finding demonstrates that children with early CHD surgery have significant cognitive impairment as children and need serial routine neurodevelopmental assessments. Future interventions, therefore, should be aimed at providing neurologic morbidity-free survival.

This study is limited by its retrospective design and the surgical era in which these children were born. The receipt of free/reduced lunch as a proxy for socioeconomic status was considered in the models, however since it is school district-dependent, and therefore not a consistent marker of an individuals’ status, it was ultimately not incorporated into the final model. The CHD cohort however, had a higher percent paying full-price for lunch compared to the state population (67% vs. 40%, Ps = 0.987). This would suggest that the CHD cohort is perhaps of higher socioeconomic status and that the elevated need for special education services among CHD children may make them more likely to attend public school, because they could not receive these services if home-schooled or went to private school. Of note, we did replace race with meal status in the regression models and found nearly identical results. In the literacy model, paying full-price for lunch was associated with increased odds of proficiency (OR 3.61, 95% CI 1.88, 6.88, p < 0.001) which was very close to the odds of achieving proficiency for white subjects (OR 3.27). Comparable odds were seen with this substitution in the mathematics model. In Arkansas, socioeconomic status and race are closely correlated. Unfortunately, we did not have consistent data on maternal education and parental intelligence scores were unavailable.

Since educational data were only available for Arkansas public school students, this study may not be generalizable to children who are home-schooled, attend private school, or who moved out-of-state. Specific data about the children who received special education such as the type of classroom environment or the medication status of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder were also not known, and would be of interest in understanding how these affect academic achievement. The educational data for the CHD subjects however, should be nearly 100%, as unless there was data entry error by the ADE, every child that ever attended public school would match to all available data. The school assessments performed by the ADE include both multiple choice style questions and short essay responses. The essays may involve higher levels of cognition and executive functioning, which is known to be affected in children with CHD [15], but sub-scores for these were not able to be obtained.

A weakness of this study is that it did not account for personal childhood characteristics, childhood diagnoses and interventions, or 9–10 years of environmental influences (e.g., schools attended, home and neighborhood environments, nutrition, childhood diseases and injuries, family and caregiver education), similar to previously performed high-quality CHD follow-up studies [3, 4, 8–16]. Given that so many factors affect academic achievement between birth and early school-age, the fact that 9–10 years later we still observed statistical differences in school performance between CHD subjects and Arkansas students is noteworthy. Another weakness is that we used observational clinical data, where treatment decisions were at the discretion of attending pediatric cardiologists and cardiovascular surgeons. The influence of oxygen saturation pre- and postoperatively on outcome was not able to be determined with the available data. In addition, the CPB strategy did not change at our center during this time period so should not affect outcome. Our center predominantly uses high flow CPB with moderate hypothermia and uses alpha-stat unless the core temperature falls <25° C, when it is switched to pH-stat. Neuroimaging was not a standard practice in CHD infants pre- and postoperatively during these operative years, so the relationship of brain imaging findings and outcome could not be determined.

Early intervention with preschool educational services for all children with early CHD surgery may improve school-age cognitive function and overall academic and lifetime achievement. Studies of preschool education in premature infants at developmental risk have shown to be of modest benefit [38, 39].

Children who survive early CHD surgery are less proficient on early school-age standardized achievement tests. They also received special education at a high rate due to cognitive impairments. These findings at early school-age are concerning, since they are associated with high school test scores, which are correlated with future economic success [30, 31]. Outcomes need to be assessed for children who have had surgery during more recent years as pre-operative and post-operative intensive care and surgical techniques have improved. The need for CPB and surgery after the neonatal period may be two predictors for reduced academic proficiency, but further studies are needed. Upcoming research must be aimed at reducing modifiable factors that contribute to long-term neurodevelopmental morbidity in order to improve cognitive outcomes and lifetime achievement among survivors of CHD surgery during infancy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Center for Translational Neuroscience award from The National Institutes of Health (P20 GM103425), the Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute, and the Arkansas Biosciences Institute that provided dedicated research time to SB Mulkey, MD, and statistical support by CJ Swearingen, PhD, and MS Melguizo, MS.

The authors appreciate Sadia Malik, MD, (University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Department of Pediatrics) who assisted with large group classification of infants [26], and Joseph Bates, MD, (Arkansas Department of Health) and Shalini Manjanatha (Arkansas Department of Health) for helping to ensure the quality and completeness of study data.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Mulkey receives funding from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Center for Translational Neuroscience, the Arkansas Children’s Hospital Research Institute, and the Arkansas Biosciences Institute. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoffman JI. Congenital heart disease: incidence and inheritance. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1990;37:25–43. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)36830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samanek M. Congenital heart malformations: prevalence, severity, survival, and quality of life. Cardiol Young. 2000;10:179–185. doi: 10.1017/s1047951100009082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Donofrio MT, Massaro AN. Impact of congenital heart disease on brain development and neurodevelopmental outcome. [Accessed May 15, 2013];Int J Pediatr. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/359390. http://www.ncbinlmnih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2938447/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flick RP, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Wilder RT, Voigt RG, Olson MD, et al. Cognitive and behavioral outcomes after early exposure to anesthesia and surgery. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1053–e1061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsia TY, Gruber PJ. Factors influencing neurologic outcome after neonatal cardiopulmonary bypass: what we can and cannot control. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:S2381–S2388. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Massaro AN, El-Dib M, Glass P, Aly H. Factors associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes in infants with congenital heart disease. Brain Dev. 2008;30:437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marino BS, Lipkin PH, Newburger JW, Peacock G, Gerdes M, Gaynor JW, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes in children with congenital heart disease: evaluation and management: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:1143–1172. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318265ee8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snookes SH, Gunn JK, Eldridge BJ, Donath SM, Hunt RW, Galea MP, et al. A systematic review of motor and cognitive outcomes after early surgery for congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e818–e827. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shillingford AJ, Wernovsky G. Academic performance and behavioral difficulties after neonatal and infant heart surgery. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:1625–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Majnemer A, Limperopoulos C, Shevell M, Rosenblatt B, Rohlicek C, Tchervenkov C. Long-term neuromotor outcome at school entry of infants with congenital heart defects requiring open-heart surgery. J Pediatr. 2006;148:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Majnemer A, Limperopoulos C, Shevell MI, Rohlicek C, Rosenblatt B, Tchervenkov C. A new look at outcomes of infants with congenital heart disease. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sananes R, Manlhiot C, Kelly E, Hornberger LK, Williams WG, MacGregor D, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes after open heart operations before 3 months of age. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1577–1583. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGrath E, Wypij D, Rappaport LA, Newburger JW, Bellinger DC. Prediction of IQ and achievement at age 8 years from neurodevelopmental status at age 1 year in children with D-transposition of the great arteries. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e572–e576. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0983-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hovels-Gurich HH, Seghaye MC, Schnitker R, Wiesner M, Huber W, Minkenberg R, et al. Longterm neurodevelopmental outcomes in school-aged children after neonatal arterial switch operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;124:448–458. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.122307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calderon J, Bonnet D, Courtin C, Concordet S, Plumet MH, Angeard N. Executive function and theory of mind in school-aged children after neonatal corrective cardiac surgery for transposition of the great arteries. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52:1139–1144. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shillingford AJ, Glanzman MM, Ittenbach RF, Clancy RR, Gaynor JW, Wernovsky G. Inattention, hyperactivity, and school performance in a population of school-age children with complex congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e759–e767. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellinger DC, Wypij D, Rivkin MJ, DeMaso DR, Robertson RL, Jr, Dunbar-Masterson C, et al. Adolescents with d-transposition of the great arteries corrected with the arterial switch procedure: neuropsychological assessment and structural brain imaging. Circulation. 2011;124:1361–1369. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.026963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marino BS, Shera D, Wernovsky G, Tomlinson RS, Aguirre A, Gallagher M, et al. The development of the pediatric cardiac quality of life inventory: a quality of life measure for children and adolescents with heart disease. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:613–626. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olsen M, Hjortdal VE, Mortensen LH, Christensen TD, Sorensen HT, Pedersen L. Educational achievement among long-term survivors of congenital heart defects: a Danish population-based follow-up study. Cardiol Young. 2011;21:197–203. doi: 10.1017/S1047951110001769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goff DA, Luan X, Gerdes M, Bernbaum J, D'Agostino JA, Rychik J, et al. Younger gestational age is associated with worse neurodevelopmental outcomes after cardiac surgery in infancy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andropoulos DB, Easley RB, Brady K, McKenzie ED, Heinle JS, Dickerson HA, et al. Changing expectations for neurological outcomes after the neonatal arterial switch operation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:1250–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaynor JW, Gerdes M, Nord AS, Bernbaum J, Zackai E, Wernovsky G, et al. Is cardiac diagnosis a predictor of neurodevelopmental outcome after cardiac surgery in infancy? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;140:1230–1237. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.07.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. [Accessed May 15, 2013];Arkansas Research Center Quick looks at Arkansas student performance. 2011 http://arc.arkansas.gov/quicklooks/

- 24.Arkansas Department of Education. [Accessed May 15, 2013];Test scores. 2012 http://www.arkansased.org/divisions/learning-services/student-assessment/test-scores.

- 25.Jenkins KJ. Risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery: the RACHS-1 method. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu. 2004;7:180–184. doi: 10.1053/j.pcsu.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Botto LD, Lin AE, Riehle-Colarusso T, Malik S, Correa A. Seeking causes: classifying and evaluating congenital heart defects in etiologic studies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:714–727. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anderson S, Hauch WW. A new procedure for testing equivalence in comparative bioavailability and other clinical-trials. Commun Statist-Theor Meth. 1983;12:2663–2692. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westlake WJ. Symmetrical confidence intervals for bioequivalence trials. Biometrics. 1976;32:741–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wellek S. Testing Statistical Hypotheses of Equivalence. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanushek EA, Jamison DT, Jamison EA, Woessmann L. Education and economic growth: it's not just going to school, but learning something while there that matters. Educ Next. 2008;8:62–70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanushek EA. Education. Building on No Child Left Behind. Science. 2009;326:802–803. doi: 10.1126/science.1177458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andropoulos DB, Hunter JV, Nelson DP, Stayer SA, Stark AR, McKenzie ED, et al. Brain immaturity is associated with brain injury before and after neonatal cardiac surgery with high-flow bypass and cerebral oxygenation monitoring. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010;139:543–556. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang N, Cole T, Tsang V, Elliott M, de Leval MR. Risk stratification in paediatric open-heart surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du Plessis AJ. Mechanisms of brain injury during infant cardiac surgery. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 1999;6:32–47. doi: 10.1016/s1071-9091(99)80045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahle WT, Tavani F, Zimmerman RA, Nicolson SC, Galli KK, Gaynor JW, et al. An MRI study of neurological injury before and after congenital heart surgery. Circulation. 2002;106:I109–I114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarajuuri A, Jokinen E, Puosi R, Eronen M, Mildh L, Mattila I, et al. Neurodevelopmental and neuroradiologic outcomes in patients with univentricular heart aged 5 to 7 years: related risk factor analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1524–1532. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sarajuuri A, Jokinen E, Mildh L, Tujulin AM, Mattila I, Valanne L, et al. Neurodevelopmental burden at age 5 years in patients with univentricular heart. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e1636–e1646. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McCormick MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Buka SL, Goldman J, Yu J, Salganik M, et al. Early intervention in low birth weight premature infants: results at 18 years of age for the Infant Health and Development Program. Pediatrics. 2006;117:771–780. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarton CM, Brooks-Gunn J, Wallace IF, Bauer CR, Bennett FC, Bernbaum JC, et al. Results at age 8 years of early intervention for low-birth-weight premature infants. The Infant Health and Development Program. JAMA. 1997;277:126–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Austin PC, Steyerberg EW. Interpreting the concordance statistic of a logistic regression model: relation to the variance and odds ratio of a continuous explanatory variable. [Accessed May 15, 2013];BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012 :12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-82. http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/1471-2288-12-82.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.