Abstract

Purpose

Delayed diagnosis of early-onset epilepsy is a potentially important and avoidable complication in epilepsy care. We examined the frequency of diagnostic delays in young children with newly presenting epilepsy, their developmental impact, and reasons for delays.

Methods

Children who developed epilepsy before their third birthday were identified in a prospective community-based cohort. An interval ≥1 month from second seizure to diagnosis was considered a delay. Testing of development at baseline and for up to three years after and of IQ 8–9 years later was performed. Detailed parental baseline interview accounts and medical records were reviewed to identify potential reasons for delays. Factors associated with delays included the parent, child, pediatrician, neurologist, and scheduling.

Results

Diagnostic delays occurred in 70/172 (41%) children. Delays occurred less often if children had received medical attention for the first seizure (p<0.0001), previously had neonatal or febrile seizures (p=0.02), had only convulsions before diagnosis (p=0.005) or had a college-educated parent (p=0.01). A ≥1 month diagnostic delay was associated with an average 7.4 point drop (p=0.02) in the Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior motor score. The effect was present at diagnosis, persisted for at least three years, and was also apparent in IQ scores 8–9 years later which were lower in association with a diagnostic delay by 8.4 points (p=0.06) for processing speed up to 14.5 points (p=0.004) for full scale IQ, after adjustment for parental education and other epilepsy-related clinical factors. Factors associated with delayed diagnosis included parents not recognizing events as seizures (N=47), pediatricians missing or deferring diagnosis (N=15), neurologists deferring diagnosis (N=7), and scheduling problems (N=11).

Significance

Diagnostic delays occur in many young children with epilepsy. They are associated with substantial decrements in development and IQ later in childhood. Several factors influence diagnostic delays and may represent opportunities for intervention and improved care.

Keywords: Health Services, Barriers to care, pediatrics, development

Epilepsy is a clinical diagnosis made on the basis of a variety of contributory factors.1–3 Oftentimes the diagnosis is made long after seizures have begun.4 Reasons for delayed diagnosis are not well understood. About 10% of all epilepsy occurs in the first three years of life.5 Early-onset epilepsy is frequently associated with significant cognitive and behavioral morbidity making early recognition of seizures and complete diagnosis of the type of epilepsy and its cause especially urgent.2, 3, 6 Furthermore, early diagnosis and effective treatment may mitigate some effects of seizures on the developing brain.6–10 While these studies suggest that delayed diagnosis and treatment are associated with worse developmental outcomes, they are often retrospective or limited to infantile spasms6–8 or to a surgically resectable lesion (e.g. hemimegalencephaly).9

How often diagnosis of epilepsy is delayed in very young children with epilepsy, the impact of delays on development and cognition, and the reasons for delays are questions that have not been studied in a setting that allows inferences to children in the general population. We examine these three questions concerning the impact of diagnostic delay in a prospective community-based setting.

Methods

Patients

Participants are from the Connecticut study of Epilepsy, a prospective community-based cohort study of childhood epilepsy first diagnosed in 1993–1997. Children were identified primarily from 16 of the 17 pediatric neurologists practicing in the state during that time. Pediatricians and adult neurologists were also contacted and efforts made to recruit from those practitioners who reported occasionally diagnosing and treating children themselves without referral to a pediatric neurologist.11

Seizure onset and epilepsy

Two unprovoked seizures at least 24 hours apart was the operational definition of epilepsy used in this study.12 Participating physicians were aware of the study inclusion criteria and referred patients to the study based on those criteria. For this analysis, children with 2 or more unprovoked seizures before their third birthday were included. This is the age group during which seizures are thought to be especially harmful to the developing brain.10

Data collection

Parents completed structured and semi-structured interviews covering gender, race, parental education, and details about the circumstances under which the seizures first occurred. This included a chronological account of the first event up through diagnosis. The interviewer compiled a report based on the parent’s account, which was then reviewed by the PI (ATB), and supplemented by further discussion with the parent when necessary. Dates of the first and second unprovoked seizure days were recorded. These accounts along with the original histories from medical records were reviewed for factors potentially contributing to prolonging time to formal diagnosis of epilepsy. Consistent with recent work, we considered a delay to be an interval of ≥1month from second seizure day to date of diagnosis.6 We also considered extent of delay (<1 month, 1 month to <4 months, 4 months to <12 months, ≥12 months). Pre-school-age children’s parents completed the Vineland Scales of Adaptive Behavior (VABS) at study entry.13 The VABS provides five scores, composite, social, communication, daily living and motor.

For follow-up, parents were called every 3–4 months. We re-reviewed medical records every 6 months. Parents completed the VABS yearly until the child entered school. We analyzed VABS scores through three years after diagnosis. Information about the child’s seizure types, underlying epilepsy, and cause were assessed through chart review and consensus of three pediatric epileptologists.11 Seizure types were categorized as convulsions (tonic, clonic, or tonic-clonic), epileptic spasms, myoclonic, staring spells (absence, focal dyscognitive, or undetermined), and other (mostly focal motor seizures). There were many underlying causes. To simplify analysis, we grouped children with specifically identified causes (e.g. brain hemorrhage of cortical dysplasia) along with children who had clear evidence of neurological impairment (e.g. hemiplegia, moderate to severe developmental delay as assessed by the clinician at initial diagnosis) as having a “complex presentation.” Children with normal exams, development, and imaging, and no specifically identified causes were considered to have an uncomplicated presentation. Type of epilepsy was grouped into three broad categories consistent with recent recommendations:14 non-syndromic epilepsies (epilepsies with focal or nondescript features with or without an identified cause), encephalopathic epilepsy syndromes (West, Lennox-Gastaut, Dravet, and other syndromes with mixed features and often associated with poor prognosis), and specific self-limited syndromes (e.g. Benign epilepsy with centro-temporal spikes (BECTS), Childhood Absence Epilepsy (CAE)).

At 8–9 years after study entry, children were invited to participate in an assessment that included the Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children (WISC-III).15 The WISC provides a full scale IQ (FSIQ) and four factor scores (verbal comprehension, perceptual organization, processing speed, and freedom from distractibility). All VABS and WISC scores standardized to a mean=100 and standard deviation (SD)=15.

Statistical analysis

Bivariate comparisons were made with t-test, chi-square test, and correlations as appropriate for the data. Multivariable regression and longitudinal regression analysis (Proc GLM and MIXED, SAS 9.3) were used to test the impact of delayed diagnosis on the child’s VABS scores at onset and over time. Residual distributions were examined to ensure appropriateness of the model and standard information criteria (−2 Log likelihood, Akaike and Bayesian Information Criteria) were considered in interpreting and comparing the models. Generalized linear regression was used to test the impact of diagnostic delay on WISC scores after adjustment for other factors.

Ethics

Parents were invited to participate in the study and provided written informed consent for participation and review of their children’s medical records. Children provided assent when older to participate in the IQ testing phase. All procedures were approved by the IRBs of all participating institutions.

Results

Demographics

Epilepsy developed before the third birthday in 172/613 (28%) children recruited in the original cohort. The median time from second unprovoked seizure to diagnosis was 0.5 months (interquartile range 0–2.6). A diagnostic delay (≥1 month) for epilepsy occurred in 70 (41%) children including 36 (21%) diagnosed between 1 and 4 month, 12 (7%) between 4 and 12 months, and 22 (13%) who were diagnosed after more than 1 year had passed.

Several clinical and demographic factors were associated with diagnostic delays (Table 1). Children with histories of prior provoked seizures (febrile or neonatal), who received medical attention for their first unprovoked seizure, had convulsive seizures or had a college-educated parent were less likely to experience a diagnostic delay. Children with only convulsive events before diagnosis were least likely to have diagnostic delays compared to all other seizure types combined (p=0.004) and to individual seizure types.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations of ≥1 month delay to diagnosis with demographic and clinical factors for 172 children who developed epilepsy before the third birthday.

| Factors (N and % of total) | <1month delay N=102 (59.3%) |

≥1 month delay N=70 (40.7%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) of row value | N (%) of row value | ||

| Gender | |||

| Boy | 66 (68.0%) | 31 (32.0%) | 0.008 |

| Girl | 36 (48.0%) | 39 (52.0%) | |

| Race – Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 82 (59.4%) | 56 (40.6%) | 0.81 |

| African American | 8 (53.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 9 (69.2%) | 4 (30.8%) | |

| Other | 3 (50%) | 3 (50%) | |

| Parents graduated from college | |||

| Neither parent | 54 (51.9%) | 50 (48.1%) | 0.01 |

| 1 or both parents | 48 (70.6%) | 20 (29.4%) | |

| History of prior provoked seizures | |||

| None | 72 (54.6%) | 60 (45.4%) | 0.02 |

| One or more | 30 (75.0%) | 10 (25.0%) | |

| Received medical attention for initial unprovoked seizures | |||

| Yes | 668 (82.9%) | 14 (17.1%) | <0.0001 |

| No | 34 (37.8%) | 56 (62.2%) | |

| Initial Seizure types prior to diagnosis | |||

| Convulsions only | 32 (78.1%) | 9 (21.9%) | * |

| Convulsions plus other seizure types | 27 (61.4%) | 17 (38.6%) | 0.10 |

| Spasms | 13 (56.5%) | 10 (43.5%) | 0.07 |

| Staring spells | 47 (51.7%) | 44 (48.3%) | 0.004 |

| Myoclonic seizures | 5 (45.5%) | 6 (54.5%) | 0.03 |

| Other seizure types | 7 (46.7%) | 8 (53.3%) | 0.03 |

| Type of epilepsy | |||

| Nonsyndromic | 79 (64.2%) | 44 (35.8%) | 0.07 |

| Early encephalopathic epilepsies | 22 (48.9%) | 23 (51.1%) | |

| Self-limited syndromes | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | |

| Presentation | |||

| Uncomplicated | 68 (61.8%) | 42 (38.2%) | 0.37 |

| Complicated* | 34 (54.8%) | 28 (45.2%) | |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age at first seizure (years) | |||

| <1 | 49 (58.3%) | 35 (41.7%) | 0.69 |

| 1- | 24 (55.8%) | 19 (44.2%) | |

| 2–3 | 29 (64.4%) | 16 (35.6%) | |

| Age at first seizure (years) | 1.25 (0.97) | 1.20 (0.84) | 0.75 |

| Age at second seizure (years) | 1.33 (0.99) | 1.27 (0.85) | 0.67 |

Intracranial infection (N=5), IVH/HIE (N=10), Chromosomal/Genetic (N=9), Malformations of cortical development (N=13), Hypoglycemic encephalopathy (N=1), CVA post neonatal (N=1), Neurometabolic disease (N=3), Tumor (N=2), Abnormal exam or imaging without specific cause identified (N=18)

Clinical factors and VABS scores

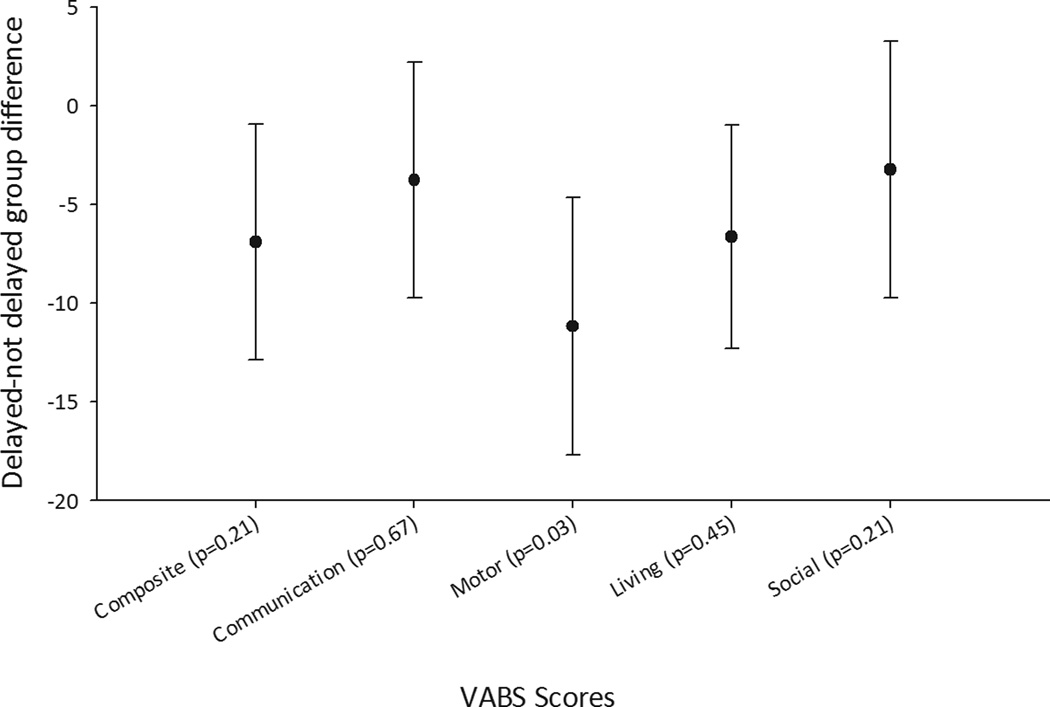

The VABS was completed for 166 (97%) at baseline, 150 (87%) at 1 year, 141 (82%) at 2 years, and 119 (69%) at 3 years after study entry. Attrition was largely due to children aging out of the targeted preschool-aged group for the VABS. Many of the clinical factors associated with diagnostic delay were also associated with lower initial VABS scores (Table 2). The baseline VABS composite, motor, and daily living scores were also significantly lower in children with a ≥1 month delayed diagnosis (Table 2). The difference in the motor score persisted through three years. In a series of longitudinal regression analyses, we adjusted for parental education, type of epilepsy (encephalopathic epilepsy syndrome versus other) and complex presentation. A previous analysis found early pharmacoresistance (failure of two informative trials of appropriate medications16) had an increasing effect on the VABS with time.17 Even with adjustments for these effects, there was a persistent association between delayed diagnosis and the VABS motor score (average difference for delayed - not-delayed groups = −6.1 points, 95% CI, −11.5, −0.8, p=0.03). Delayed diagnosis was associated with decreases in the other VABS scores, but these did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1). We compared models in which delay was represented as <1 versus ≥1 month versus the ordinal representation (<1, 1−, 4−, 12+ months). The models were highly similar based on model R-squares and examination of the information criteria with minor differences between the models depending on the specific outcome variable under consideration. For parsimony, we chose to use the 1-month delay definition for these analyses as the other representation did not provide a substantially different understanding of the associations. We also tested the effect of individual seizure types and compared seizure types to syndrome groups. Syndrome group remained statistically significant, and seizure types did not contribute significantly to the prediction of VABS scores. We tested whether the effect of delay changed over time by including an interaction effect for delay and time. No evidence of change was found, consistent with the unadjusted, bivariate means presented in Table 3.

Table 2.

Association between baseline clinical variables and baseline Vineland scores.

| Composite Mean (SD) |

Communication Mean (SD) |

Motor Mean (SD) |

Daily Living Mean (SD) |

Social Mean (SD) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 90.5 (20.5) | 90.4 (18.9) | 92.8 (24.1) | 91.0 (18.2) | 95.0 (22.5) |

| Male | 91.2 (19.0) | 92.8 (19.8) | 94.2 (20.0) | 89.1 (18.8) | 94.4 (20.0) | |

| p-value | 0.82 | 0.42 | 0.69 | 0.52 | 0.86 | |

| College educated parent | No | 87.9 (19.4) | 89.6 (19.4) | 91.2 (21.6) | 86.7 (17.0) | 92.9 (20.9) |

| Yes | 95.3 (19.2) | 95.0 (19.1) | 97.1 (21.8) | 94.8 (19.8) | 97.4 (20.8) | |

| p-value | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.005 | 0.17 | |

| Encephalopathic form of epilepsy | No | 93.8 (19.4) | 93.9 (18.9) | 98.7 (21.8) | 89.1 (18.0) | 98.6 (20.8) |

| Yes | 82.9 (17.9) | 85.9 (19.8) | 79.6 (14.4) | 92.3(20.0) | 84.2 (17.6) | |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | 0.3 | <0.0001 | |

| Came to attention for first seizure | No | 87.6 (19.8) | 89.8 (19.4) | 89.5 (21.0) | 88.4 (19.4) | 90.9 (20.4) |

| Yes | 94.3 (18.9) | 93.9 (19.3) | 97.9 (21.9) | 91.5 (17.5) | 98.8 (20.9) | |

| p-value | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.02 | |

| Convulsive seizures | No | 89.4 (19.1) | 91.2 (18.7) | 91.9(22.0) | 89.6 (18.4) | 92.2 (19.8) |

| Yes | 95.6 (20.6) | 93.8 (21.7) | 98.7(20.3) | 90.8 (19.0) | 102.4 (22.8) | |

| p-value | 0.08 | 0.45 | 0.08 | 0.72 | 0.006 | |

| Spasms | No | 91.7 (20.0) | 92.3 (19.6) | 95.6 (22.4) | 88.7 (18.9) | 96.5 (21.1) |

| yes | 85.5 (16.5) | 88.3 (18.1) | 80.9 (11.5) | 97.6 (14.1) | 83.3 (16.5) | |

| p-value | 0.16 | 0.36 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.005 | |

| Complex presentation | No | 98.5 (17.3) | 98.3 (18.1) | 103.2 (18.3) | 92.6 (16.1) | 101.5 (20.7) |

| Yes | 77.8 (16.3) | 80/5 (17.5) | 77.1 (17.0) | 85.4 (21.5) | 82.9 (15.6) | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | <0.0001 |

Figure 1.

Average difference (delayed-not delayed) with 95% confidence intervals in VABS scores over time after adjustment for early drug failure, time since diagnosis, their interaction, known cause for the epilepsy, type of epilepsy, and parental education.

Table 3.

Mean VABS scores at baseline and through 3 years after diagnosis and IQ scores 8–9 years later in children with and without a ≥1month delay from the development of epilepsy to its diagnosis.

| A. Vineland Scores* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | <1 month delay (N=102) Mean (SE) |

≥1 month delay (N=67) Mean (SE) |

p-value |

| Composite | 93.6 (1.8) | 86.7 (2.6) | 0.03 |

| Communication | 93.3 (1.9) | 89.5 (2.5) | 0.22 |

| Motor | 98.0 (2.1) | 86.9 (2.6) | 0.001 |

| Daily living | 92.6 (1.8) | 85.9 (2.3) | 0.02 |

| Social | 95.9 (2.0) | 92.8 (2.7) | 0.33 |

| 12-months | (N=94) | (N=59) | |

| Composite | 87.5 (2.8) | 79.6 (3.1) | 0.07 |

| Communication | 90.0 (2.7) | 86.9 (3.2) | 0.46 |

| Motor | 93.4 (3.0) | 80.3 (3.4) | 0.006 |

| Daily living | 79.2 (2.0) | 74.6 (2.6) | 0.16 |

| Social | 92.3 (2.7) | 86.7 (3.2) | 0.19 |

| 24-months | N=90 | N=53 | |

| Composite | 85.6 (3.2) | 75.9 (3.8) | 0.06 |

| Communication | 89.1 (2.9) | 82.1(3.2) | 0.12 |

| Motor | 86.2 (3.3) | 75.7 (4.0) | 0.05 |

| Daily living | 77.7 (2.6) | 70.9 (3.7) | 0.13 |

| Social | 92.1 (3.1) | 84.7 (3.8) | 0.14 |

| 36-months | N=78 | N=43 | |

| Composite | 85.0 (3.6) | 74.7 (4.2) | 0.08 |

| Communication | 88.7 (3.2) | 79.7 (3.6) | 0.08 |

| Motor | 85.1 (4.2) | 72.2 (5.2) | 0.06 |

| Daily living | 76.7 (3.2) | 69.9 (3.9) | 0.20 |

| Social | 93.4 (3.3) | 81.8 (3.8) | 0.03 |

| B. WISC scores at 8–9 years after diagnosis** | |||

| <1 month delay (N=37) | ≥1 month delay (N=37) | p-value | |

| FSIQ | 103.4 (3.2) | 83.0 (3.9) | 0.0001 |

| Verbal comprehension | 106.3 (2.9) | 88.5 (3.5) | 0.0002 |

| Perceptual organization | 101.2 (3.2) | 87.8 (3.6) | 0.006 |

| Processing Speed | 98.8 (2.9) | 85.6 (3.4) | 0.004 |

| Freedom from distractibility | 104.1 (3.0) | 86.3 (3.6) | 0.0003 |

SE: Standard Error

Vineland scores were missing for 3 (Baseline), 19 (12 months), 29 (24 months), and 51 (36 months)

Of those not tested with the WISC, 59 had moderate to severe impairment, 11 had been lost to follow-up and 1 had died. 27 chose not to participate.

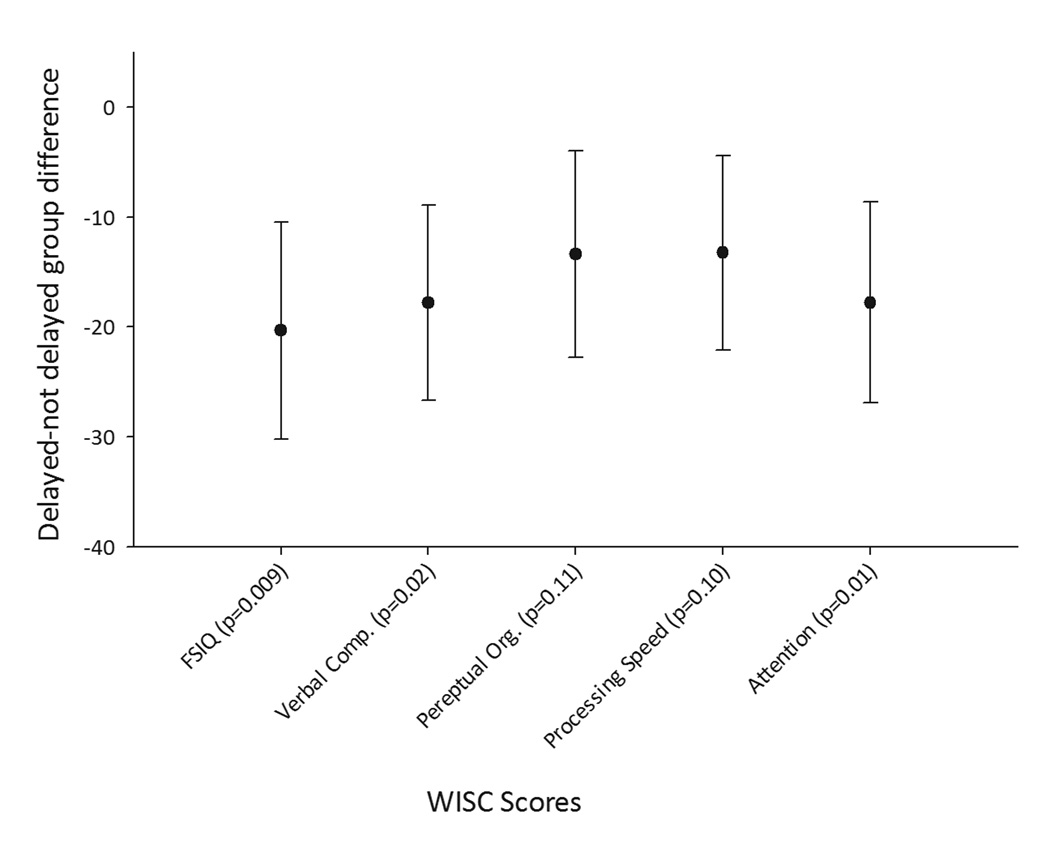

Seventy-two children participated in WISC testing 8–9 years later. Of those who did not, 59 had moderate to severe impairment as ascertained through medical record review and parent report, 11 had been lost to follow-up, 1 had died, and 27 chose not to participate. On bivariate analysis, delayed diagnosis was associated with as much as a 20-point decrease in the full scale IQ and the four factor scores from the WISC (Table 2b). After adjustment for parental education, complex presentation, type of epilepsy and pharmacoresistance, the effect of diagnostic delay was still substantial: full scale IQ: −12.4 (p=0.009); verbal comprehension: −10.2 (p=0.02); perceptual organization −7.6 (p=0.11); processing speed: −7.1 (p=0.10); freedom from distractibility: −11.2 (p=0.01) (Figure 2, eTable 1). Individual seizure types did not significantly contribute to these models.

Figure 2.

Average difference (delayed-not delayed) with 95% confidence intervals in WISC scores measured 8–9 years after diagnosis as associated with a ≥1 month diagnostic delay and after adjustment for early drug failure, known cause, type of epilepsy, and parental education.

Factors associated with delays

In reviewing the parents’ verbal accounts of their children’s seizure histories, we found four factors that appeared to play a role in prolonging the time to diagnosis: the parent, pediatrician, neurologist, and scheduling (Table 4). More than one factor could be present in a given a child. Sixteen children also had pronounced developmental delays or medically complicated presentations, which may have also contributed to delays in diagnosing epilepsy.

Table 4.

Factors contributing to a ≥1 month delay between the second unprovoked seizure and the diagnosis of epilepsy in 70 children with ≥1 delay to diagnosis. Multiple factors were often present for a single child.

| Source contributing to delay | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Parent: The parent(s) noticed the events but did not understand what they were and did not act for some time. | 47 (67 %) |

| Triggers that lead to parent seeking attention included: increased frequency of spells (12), seizures became more severe (N=3), appearance of convulsions (N=9), events went on for too long (N=7). | |

| Child was seen for first seizure but parents did not act immediately when subsequent seizures occurred (N=6). | |

| Nocturnal seizure were only recognized in retrospect (n=2). | |

| Parents were aware of events but waited for the next appointment to mention the events to the pediatrician (N=5). | |

| Parent sought non-pharmacologic treatments first (N=1). | |

| Seizures were recognized by someone else who observed them in person: pediatrician during office visit (N=4), preschool teacher (N=2), physical therapist (N=1), relative with epilepsy (N=1) | |

| Pediatrician: The events were brought to pediatrician’s attention but were not diagnosed as seizures. | 15 (21%) |

| The pediatrician ordered an EEG that came back normal (N=3). | |

| The pediatrician considered seizures but waited for another (or more) event(s) to occur before acting (N=6). | |

| The pediatrician misidentified the events as being symptoms of another disorder -colic (N=1), breath holding spells (N=2). | |

| The pediatrician said the behaviors were nothing or were normal (N=5). | |

| Neurologist: The neurologist considered epilepsy but deferred the diagnosis | 7 (10%) |

| An EEG was performed but was normal, diagnosis could not be established at that time (N=6) | |

| Unprovoked seizure mixed with febrile seizures (N=1) | |

| Scheduling: | 11 (15%) |

| Time from referral to appointment for EEG or neurologist either exceeded 1 month or, in combination with other delays pushed the delay to >1 month. | |

| Other issues | 5 (7%) |

| Lack of insurance resulted in delay to obtaining EEG (N=2) | |

| Parent had difficulties (psychiatric) that interfered with care of child (N=1) | |

| Breakdown in complex care (N=1) | |

| Child first evaluated for seizures while visiting out of state (N=1) | |

| Medically Complicated Child: The child had other serious developmental or medical concerns. These may have contributed to the reasons for delays above. Many of these children were already being seen by other specialists when seizures began. | 16 (20.5%) |

Not recognizing events as seizures on the part of the parent was the most common contributor to diagnostic delays (N=47). Delays at the level of the pediatrician occurred in 15 instances. Neurologists deferred diagnosis in 6 children after the EEG was interpreted as normal. Scheduling delays ranged from minimal (but, in combination with other factors, associated with a time to diagnosis of over a month) to over two months in 11 instances. Most scheduling delays were in the range of a few weeks to a month. Some of these children had already had a normal EEG.

Discussion

In a community-based setting, a substantial proportion of children with early onset epilepsy had a ≥1 month delay to diagnosis of epilepsy. Developmental scores (particularly motor) at the time of diagnosis and for three years after as well as IQ scores 8–9 years later were lower in association with delayed diagnosis. This persisted after adjustment for other explanatory factors, specifically parental education, complex initial presentation (which includes identified brain conditions as well as neurological impairment on exam regardless of an identified cause), pharmacoresistance, and type of epilepsy. Several of the factors that contributed to delays may represent opportunities for parent and provider education and system improvements.

Delayed diagnosis of epilepsy has been reported in adults and older children, for whom nonconvulsive seizures went undiagnosed for months or even years4 Studies of infantile spasms documented considerable delay in recognition of spasms by parents and diagnosis by physicians and demonstrated impaired developmental outcomes in association with these delays.6, 7

Notably, after adjustment for parental education, we did not find the same global impact on development reported by others.6, 7 Generally, we would not expect parental education to have a large impact on early developmental scores; however, the VABS is a parent-reported form and therefore could be somewhat influenced by parent’s educational level. Other investigators did not adjust for parental education when reporting Vineland results so we cannot compare our results with theirs directly.6, 7 We still found an impact in the motor domain, an area we might expect to be least affected by parental education, especially at this early age.

Our findings for development are consistent with those reported in a variety of studies that have examined the developmental impacts of early onset epilepsy.6, 7, 9, 10, 18 In addition, the sizable decrement in IQ scores several years later was also associated with delayed diagnosis even after adjustment for parent’s education, complex presentation, encephalopathic form of epilepsy, and pharmacoresistance. We not that only 74/172 (43%) children had WISC testing. A disproportionate number of those not tested had moderate to severe intellectual disability based on parental report and review of their records. Our results are thus most relevant to children who are not the most severely impaired. To our knowledge, this may be the first time that an association between diagnostic delay of early-onset epilepsy and IQ measured several years later has been demonstrated.

Reasons for these findings could be biological or social. One possible factor that may contribute to our findings has been referred to as “epileptic encephalopathy.” Although often used to refer to forms of epilepsy (such as West syndrome) the concept was redefined recently to describe a process by which seizure activity in the brain, above and beyond any impact attributable to the underlying cause, may have an adverse effect upon cognition.14 This may occur in any person; however, in the developing brain, the concern is that the ongoing seizure activity disrupts processes necessary for establishing mature function during the critical period of brain development, thereby leading to long-term developmental and cognitive consequences. Another possibility is that there may be parental or related factors, beyond what can be measured by college education, that result in earlier diagnoses being made and which are also associated with better developmental and cognitive levels. Whichever is the case a delay to diagnosis may identify patients at risk for delay later in life and in greatest need for early developmental intervention. If this represents a causal effect (epileptic encephalopathy), this could mean that some of the cognitive difficulties seen in children with epilepsy may be avoidable.

Numerous factors may pose obstacles to timely appropriate care for children with epilepsy and may represent opportunities for interventions.19 Parents often did not recognize subtle events as being of concern. It is unclear how to address this through public health awareness or office-based informational programs. The over-recognition of non-epileptic seizure-like events and the anxiety that could be caused need to be carefully addressed and minimized before implementing any broad educational or awareness strategy. Some pediatricians recognized seizures and reacted immediately. Others told parents that these were normal behaviors or made a different diagnosis. Auvin et al. also found a proportion of physicians discounting the seizures as normal or nothing to worry about.6 Physician knowledge, particularly among non-neurologists, of the range of seizure types and impact of epilepsy is clearly an area for medical student and resident training, quality improvement and continuing medical education. Currently in the US, there is no requirement for pediatric residents to receive neurology training; it is an elective.20

Notably, several pediatricians and neurologists appropriately ordered an EEG, which was interpreted as normal. Consistent with community-based practice then and now, EEGs were typically performed as brief outpatient studies, the diagnostic yield of which is reputedly low.21–24 The gold standard for diagnosing seizures requires prolonged (hours to days) simultaneous video-EEG recordings of ictal events, a technique not often used for an initial evaluation and not very helpful in patients with infrequent seizures. Consequently, the EEG, especially standard outpatient EEG, must be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical history. In addition to duration, three factors affect EEG interpretation: quality of the EEG recording, provocation maneuvers, and the EEG reader. The EEGs in this study complied with published quality parameters for EEG.25 Provocations, such as sleep deprivation, hyperventilation, and photic stimulation may increase the yield of recording spikes during a routine EEG.26 The level of training of the EEG reader also influences interpretation.27, 28 The EEG, however, is not a test for epilepsy. Absence of interictal discharges does not preclude epilepsy; presence of interictal discharges does not confirm a diagnosis of epilepsy. This makes diagnosis of epilepsy much harder than for other common chronic diseases where clinicians may witness signs (e.g. wheezes on exam with asthma) or can obtain diagnostic (blood) tests (e.g. fasting glucose for diabetes).

Scheduling is a ubiquitous problem, especially for children in need of specialty care. Many systems are implementing access metrics to ensure that patients are seen within an acceptable timeframe. “Time-to-next-third-available appointment” can improve patient no-show rates and wait time.29 A related concept specific to epilepsy is the First Seizure or New-Onset Clinic which provides rapid access (e.g. within a week) for newly presenting seizure patients each week. Planning capacity for such a clinic is based on a center’s or office’s typical volumes. Further, a model of “access” pediatricians who are embedded within subspecialty clinics has also been associated with improved wait times and higher parent/patient satisfaction although the impact on patient outcomes has not yet been formally demonstrated.30

Perhaps most sobering, some children already under the specialists’ care did not receive a timely diagnosis. The lack of coordination in care and communication among the specialists caring for a patient may represent another opportunity for improving care and management of children with complex presentations.31 The rise of Accountable Care Organizations could possibly address both the scheduling and coordination of care issue32 as well as access discrimination based on type of insurance.33

There are relative weaknesses and strengths of our study. All patients were recruited beginning 20 years ago in a single state. Since then, however, little has changed in pediatric epilepsy care that would lead us to believe that the delays we observed and the reasons for them would have changed during that time, especially as most were due to parents and pediatricians. The results of a recent workshop involving parents of children with epilepsy, highlighted that the same concerns associated with delays that were found in the 1990s exist today and, in fact, the workshop motivated this analysis.34 We suspect the results from our study likely reflect what happens in the US today where we currently have few standards and guidelines. This may be different from the situation in the UK where the National Institute for Clinical Excellence has a pediatric clinical care pathway urging that children with suspected seizures be seen within 2–4 weeks, by a pediatric specialist.35

Connecticut is a relatively well-off state with two large medical centers and 17 practicing pediatric neurologists for a population of, at the time, about 500,000 children. Thus, Connecticut may represent a setting with above average access to pediatric neurologists, and our findings may reflect what happens under some of the best of circumstances. We suspect that epilepsy care may be even less optimal in most other settings in the US and elsewhere.

Strengths include that patients were recruited on a community-wide basis. We studied all children under three years of age and used standardized assessments of development starting at initial diagnosis. We were able to examine the impact of delayed diagnosis on developmental status at diagnosis and its impact on IQ in mid-childhood while taking into account the impact of refractory seizures and parental education.17 We used a parent-reported adaptive behavior assessment and not a clinician performed standardized examination such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development. The Vineland is a well-standardized instrument used both clinically and in research (e.g. the UKISS study7). Given the scope of this study, both the geographic decentralization and the repeated assessment every year, the Vineland was an excellent choice of instruments. While the Bayley Scales may provide a definitive clinical diagnosis of delay, there is no evidence that the overall assessment of level of function would be substantially different from that provided by a parental assessment such as the Vineland. A recent report compared a revised version of the both the Vineland and Bayley (neither available at the time children were assessed in this study) and found them reasonably comparable for most purposes.36 Finally, the purpose in using the VABS was to make valid comparisons between groups of children within the cohort based on an accepted, standardized measure, not to make a clinical diagnosis of delay.

Early onset epilepsy represents a complex set of disorders. Manifestations range from dramatic convulsions to relatively subtle events that are difficult to appreciate. Rapid and accurate diagnosis is a key goal, as minimizing delays may be associated with better developmental outcomes. There are clearly many areas including parent awareness and education, pediatrician training, improved care coordination, and perhaps standards for EEG in evaluating a new patient (to avoid false negatives), that could be addressed to optimize pediatric epilepsy care.

Our findings support the growing literature implicating the potential consequences associated with untreated seizures in the developing brain,6, 7 and the need for timely aggressive intervention.9, 10, 18 The US might consider the development of care pathways such as those in the UK; however, we will first need to develop the evidence base to support such recommendations and their implementation within the US healthcare system. Minimizing diagnostic delays would directly address recent recommendations from the Institute of Medicine37 and would also promote a goal from Healthy People 2020, “to increase the proportion of people with epilepsy and uncontrolled seizures who receive appropriate care.”38

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funded by : A grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R37-NS31146

Dr. Berg has received speaker honoraria and travel support from BIAL and MUSC, and travel support from the ILAE, serves on advisory boards for CURE and Eisai, serves on the editorial boards of Epilepsy & Behavior and Neurology, and is supported by funding from the NINDS (Grant R37-NS31146) and the Pediatric Epilepsy Research Foundation.

Dr. Loddenkemper serves on the Laboratory Accreditation Board for Long Term (Epilepsy and Intensive Care Unit) Monitoring, on the Council of the American Clinical Neurophysiology Society, on the American Board of Clinical Neurophysiology, as an Associate Editor for Seizure, the European Journal of Epilepsy, as an Associate Editor for Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy 6th edition, as an Editorial Board member for Biomedical Research International, and performs video electroencephalogram long-term monitoring, electroencephalograms, and other electrophysiological studies at Boston Children's Hospital and bills for these procedures. T.L. receives research support from the National Institutes of Health/NINDS (1R21NS076859-01), a Career Development Fellowship Award from Harvard Medical School and Boston Children's Hospital, the Payer Provider Quality Initiative, The Epilepsy Foundation of America (EF-213882 & EF-213583), the Center for Integration of Medicine and Innovative Technology, the Epilepsy Therapy Project, from an Infrastructure Award by the American Epilepsy Society, CURE and from investigator initiated research grants from Lundbeck and Eisai.

Dr. Baca receives support from grant NINDS-R37-NS31146. Dr. Baca has received travel support from CURE.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors affirm that the work described in this study is consistent with Epilepsia’s guidelines for ethical publication.

References

- 1.Camfield P, Camfield C. Long-term Prognosis for Symptomatic (Secondarily) Generalized Epilepsies: A Population-based Study. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1128–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cross JH. Pitfalls in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of epilepsy. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2009;19:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamiwka LD, Singh N, Niosi J, et al. Diagnostic inaccuracy in children referred with "first seizure": role for a first seizure clinic. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1062–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CAROLE. Délais évolutifs des syndromes épileptiques avant leur diagnostic : résultats descriptifs de l'enquête CAROLE. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2000;156:481–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camfield CS, Camfield PR, Gordon K, et al. Incidence of epilepsy in childhood and adolescence: a population-based study in Nova Scotia from 1977 to 1985. Epilepsia. 1996;37:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1996.tb00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auvin S, Hartman AL, Desnous B, et al. Diagnosis delay in West syndrome: misdiagnosis and consequences. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1695–1701. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1813-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Callaghan FJK, Lux AL, Darke K, et al. The effect of lead time to treatment and of age of onset on developmental outcome at 4 years in infantile spasms: Evidence from the United Kingdom Infantile Spasms Study. Epilepsia. 2011;52:1359–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vendrame M, Alexopoulos AV, Boyer K, et al. Longer duration of epilepsy and earlier age at epilepsy onset correlate with impaired cognitive development in infancy. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2009;16:431–435. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jonas R, Nguyen S, Hu B, et al. Cerebral hemispherectomy: Hospital course, seizure, developmental, language, and motor outcomes. Neurology. 2004 May 25;62:1712–1721. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000127109.14569.c3. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loddenkemper T, Holland KD, Stanford LD, et al. Developmental Outcome After Epilepsy Surgery in Infancy. Pediatrics. 2007;119:930–935. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berg AT, Shinnar S, Levy SR, et al. Newly diagnosed epilepsy in children: presentation at diagnosis. Epilepsia. 1999;40:445–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1999.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guidelines for epidemiologic studies on epilepsy. Epilepsia. 1993;34:592–596. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales: Interview edition survey forms manual. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berg AT, Berkovic SF, Brodie MJ, et al. Revised terminology and concepts for organization of seizures and epilepsies: Report of the ILAE Commission on Classification and Terminology, 2005–2009. Epilepsia. 2010;51:676–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: Consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1069–1077. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berg AT, Smith SN, Frobish D, et al. Longitudinal assessment of adaptive behavior in infants and young children with newly diagnosed epilepsy: influences of etiology, syndrome, and seizure control. Pediatrics. 2004;114:645–650. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1151-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freitag H, Tuxhorn I. Cognitive Function in Preschool Children after Epilepsy Surgery: Rationale for Early Intervention. Epilepsia. 2005;46:561–567. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.03504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baca CB, Vickrey BG, Vassar S, et al. Time to pediatric epilepsy surgery is related to disease severity and nonclinical factors. Neurology. 2013;80:1231–1239. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182897082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ACGME. ACGME Program requirement for graduate medical education in pediatrics.: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodin D, Aminoff M. Does the interictal EEG have a role in the diagnosis of epilepsy? Lancet. 1984;1:8381:1837–1839. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salinsky M, Kanter R, Dasheiff R. Effectiveness of multiple EEGs in supporting diagnosis of epilepsy: an operational curve. Epilepsia. 1987;28:331–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1987.tb03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiner A, Pohlmann-Eden B. Value of the early electroencephalogram after a first unprovoked seizure. Clinical Electroencephalography. 2003;34:140–144. doi: 10.1177/155005940303400307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King M, Newton M, Jackson G, et al. Epileptology of the first seizure presentation: a clinical electroencephalographic, and magnetic resonance imaging study of 300 consecutive patients. Lancet. 1998;352:1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03543-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharbrough F, Chatrian G, Lesser R, et al. American Electroencephalographic Society guidelines for standard electrode position nomenclature. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1991;8:200–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liporace J, Tatum W, Morris GL, 3rd, et al. Clinical utility of sleep-deprived versus computer-assisted ambulatory 16-channel EEG in epilepsy patients: a multi-center study. Epilepsy Research. 1998;32:357–362. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benbadis S, Lin K. Errors in EEG interpretation and misdiagnosis of epilepsy. Which EEG patterns are over-read? Eur Neurol. 2008;59:267–271. doi: 10.1159/000115641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert DL, Sethuraman G, Kotagal U, et al. Meta-analysis of EEG test performance shows wide variation among studies. Neurology. 2003;60:564–570. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000044152.79316.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rose KD, Ross JS, Horwitz LI. Advanced access scheduling outcomes: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1150–1190. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Guglielmo MD, Plesnick J, Greenspan JS, et al. A New Model to Decrease Time-to-Appointment Wait for Gastroenterology Evaluation. Pediatrics. 2013 May 1;131:e1632–e1638. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2372. 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toomey SL, Chien AT, Elliott MN, et al. Disparities in unmet need for care coordination: the national survey of children's health. Pediatrics. 2013;131:217–224. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Homer CJ, Patel KK. Accountable care organizations in pediatrics: Irrelevant or a game changer for children? JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:507–508. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bisgaier J, Rhodes KV. Auditing Access to Specialty Care for Children with Public Insurance. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;364:2324–2333. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1013285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berg AT, Baca CB, Loddenkemper T, et al. Priorities in pediatric epilepsy research: improving children's futures today. Neurology. 2013 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a55fb9. accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.NICE. The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care: NICE clinical guidance 137. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scattone D, Raggio DJ, May W. Comparison of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, second edition, and the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, third edition. Pschol Reports. 2011;109:626–634. doi: 10.2466/03.10.PR0.109.5.626-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.IOM. Epilepsy across the spectrum: promoting health and understanding. Washington DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Healthy People 2020. [Accessed 3-31-2013];2013 Available at: http://healthypeople.gov/2020/default.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.