Abstract

Aims

To predict South Florida family care-givers’ need for and use of informal help or formal services; specifically, to explore the predictive power of variables suggested by the Caregiver Identity Theory and the literature and develop and test a structural model 0.

Background

In the USA, most of the care to older adults is given by family members. Care-givers make economic and social sacrifices that endanger their health. They feel burdened, if they receive no assistance with their tasks; however, services available are not sufficiently used.

Design

This cross-sectional correlational study was a survey of family care-givers in their home, using standardized and/or pre-tested scales and a cognitive status test of their patients.

Methods

A random sample of 613 multiethnic care-givers of frail elders was recruited in home care and community agencies. The interviews occurred between 2006–2009. Analyses involved correlation and regression analyses and structural equation modeling. Outcome measures were need and use of family help and formal services.

Results/Findings

The model yielded excellent fit indices replicated on three random samples of 370. The patients’ functional limitations yielded the strongest predictive coefficients followed by care-giver stress. Cultural indicators played a minor role.

Conclusion

The lack of a link between resource need and use suggested access barriers. Important for policy makers and service providers are the delivery of high-quality services and the use of a personal and individualized approach with all ethnicities. Quality service includes understanding the care-giving situations and requires a trusting relationship with family care-givers.

Keywords: Family care-giving, nursing, care-giver needs, care-giver services, culture, elder function, care-giver burden, Caregiver Resources

INTRODUCTION

In the United States and world-wide, most of the aid given to older adults in their daily living activities is provided by family members (Whitlatch & Feinberg 2006). In the industrial world, the extended family is often not available. Under such conditions, caring for a loved one can have detrimental effects on the family care-givers’ physical and mental well-being (Schulz & Sherwood 2008). Multiple studies from North America, Europe and Asia have shown that their duties may increase their physical and psychological morbidity (Cormac & Tihanyi 2006, Pinquart & Sörensen 2003, Schulz & Sherwood 2008). While living with a family member with urgent health needs, family care-givers in privatized health care systems like the one in the United States are at a high risk of not being able to access the services they need (Chaix et al. 2006). This study was to inform nurses working with care-giving families by showing what factors may lead to decisions about using family help or service programs. Nurses may detect parallels or discrepancies depending on their own healthcare context and can draw informed practice conclusions.

Background

With few exceptions, the literature reviewed here includes articles written between the years 2000 and 2011. This literature shows uniformly that U.S. family care-givers underuse healthcare resources, even if they have access to them (Adams et al. 2006). Research has identified several barriers preventing the use of services like respite, home-delivered meals, or adult day care. These barriers include problems with language, resistance on the part of the care recipient to receive services, feelings of guilt or shame about needing/accessing help, having difficulties finding suitable resources, not being eligible for services (Rooney et al. 2006), or lack of knowledge about available services (Zabalegui et al. 2008). Ethnic minority care-givers tend to rely on informal support networks; they lack knowledge of formal services, often mistrust providers, or cannot pay for services (Scharlach et al. 2006).

Addressing service underuse, our study focused on the problem from a somewhat different perspective, exploring what factors may encourage the use of services or the help of family members. A perception of need of services or family help, also explored in the study, was believed to be a precursor for action to take place.

Cultural beliefs have a strong impact on an individual’s view of the care-giving role and the use of resources (Scharlach et al. 2006). Some researchers claim that diverse family care-givers therefore experience their role in different ways and that their sense of burden and willingness to commit themselves to giving care change over time (Beach et al. 2000). Each family seems to develop its own standards about care-giving responsibilities, role assignments and the appropriateness of using resources for care (Montgomery & Kosloski 2009), so that each care-giver is subject to different family demands and constraints (Franks et al. 2003).

When comparing service use by USA family care-givers from diverse ethnic groups, however, findings are inconclusive and even contradictory. Williams (2005) found no differences by race and another research team reported that Hispanic family care-givers used services more than Whites and African-Americans (Kosloski et al. 2002), while other researchers cited underuse of resources by minorities, possibly due to low acculturation and other factors (NAC & AARP 2004, Whittier et al. 2005). A telephone survey of over 1500 family care-givers showed that ethnicity alone had little influence on service use (Scharlach et al. 2008), but that education, emotional support and belief about the meaningfulness of the care-giver role significantly influenced service use. Whittier and colleagues (2005), studying the use of respite services, also concluded that ethnicity alone did not explain service use. Instead, inadequate marketing of the services, negative attitudes and cost seemed more influential.

Taken together, these studies suggest that multiethnic family care-givers provide similar types of care (Mausbach et al. 2004). Their perception of the need for outside services seems to be driven mainly by the increasing debility of the care recipient and demands for care (Scharlach et al. 2008). Nevertheless, we assumed that in this multicultural sample, the family care-givers’ perception of burden was colored by the cultural understanding of the care-giving role and family values (Phillips et al. 1996). We therefore selected variables suggested by Montgomery and Kosloski’s (2009) Care-giver Identity Theory. This theory maintains that the care-giving role evolves from existing family relationships and gender roles governed by cultural norms and rules. Such norms determine which family members carry what type of responsibility in the care-giving process and the conditions under which it is appropriate to engage help from the family or the community. Thus, family care-givers develop a distinct identity within the overall family processes. To make adjustments that are necessary in dealing with social and health care systems and with changing demands of care, care-givers may need to compromise some values and change their attitudes and consequently their behaviors. It is of prime importance for nurses to understand why some family care-givers develop burden and depression and why these care-givers have not adjusted their role norm to changing circumstances, or have not used outside resources that could have facilitated their work.

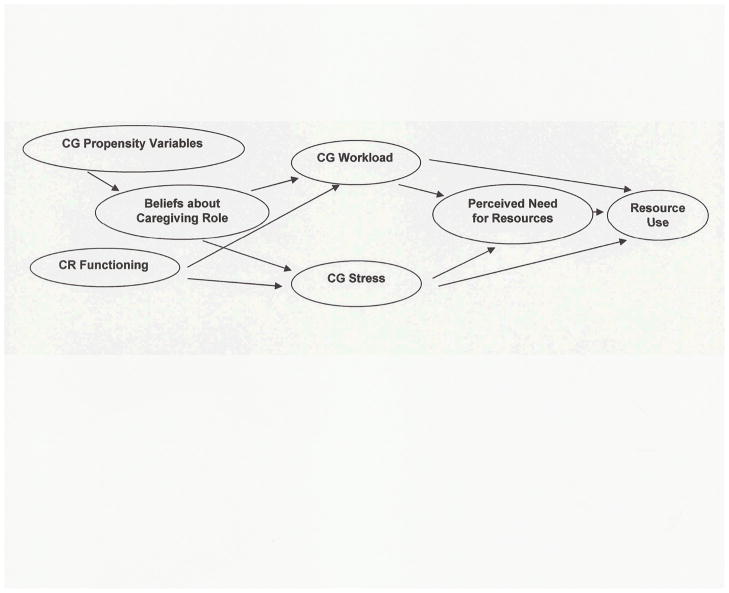

To gain a better understanding of these complex phenomena, we proposed the conceptual model pictured in Figure 1. We assumed that ethnicity, other care-giver demographics and family relationship variables (Propensity Variables) affect the care-givers’ cultural norms and, therefore, their beliefs about what their care-giving role should be (Beliefs about Care-giving Role). These beliefs, in turn, determine the willingness to perform the necessary tasks and therefore influence the care-givers’ workload (CG Workload). In addition and perhaps more so, the care-givers’ workload is defined by the care recipients’ physical and cognitive limitations (CR Functioning) that determine the demand for care. According to the Care-giver Identity Theory, crises develop when care-giving demands more involvement than the care-givers are willing to assume based on their culturally formed identity (Beliefs about Caregiving Role), causing a sense of burden or depression (CG Stress). Such crises are accelerated by declining functional abilities of the care recipient (CR Functioning), also leading to a sense of burden and depression (CG Stress). Based on their workload and the extent of stress, family care-givers define their needs for help (Perceived Need for Resources). They make decisions to either adjust their situation by using family or community resources (Resource Use) or to keep working beyond their originally set norm. Through this study we expected to learn more about the above hypothesized processes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

THE STUDY

Aims

The aim of the study was to predict South Florida family care-givers’ perception of need for family help or services and the actual family help rendered and services used. Specifically, we intended to explore the predictive power of variables suggested by Montgomery and Kosloski’s Caregiver Identity Theory and the literature by developing a structural model (SEM) and testing it with three independent samples.

Design

This cross-sectional correlational study entailed the completion of an interview schedule composed of standardized tools and pre-tested instruments with family care-givers and a mental status exam with their patients.

Sample/Participants

The study sample included 613 family care-givers of relatives with a variety of chronic ailments living in South Florida. They were eligible, if they were primary family care-givers involved in decisions about the use of services in caring for a relative age 65 or older in need of assistance with one or more activities of daily living. They had to live with the relative or be no farther away than 30 minutes by car and needed to speak either English or Spanish. The majority (573) of the care-givers was recruited from the home health nursing services of two hospitals and three private home care agencies. We considered the use of home health nursing sites to be an appropriate approach to sampling based on the findings of Kosloski et al. (1999) that the use of medical and home care after a hospitalization is covered by the medical insurance for seniors, does not vary among ethnic groups, is ordered by the physician and should not be considered a discretionary service like the services studied here. All our sites allowed access to family care-givers of various ethnicities and socioeconomic levels who used formal services or did not. The institutions picked clients uniformly, according to a randomization scheme, from a list of qualified cases. Visiting agency staff obtained permission from the sampled clients and their care-givers to be contacted by the researchers. About 20%, primarily Black family care-givers, declined participation. Due to these difficulties, minority nursing students and community leaders in black neighborhood organizations made contact with potential participants and recommended the study. This non-random procedure provided about 40 participants from the Caribbean islands and Latin America.

A sample size estimation for the analysis using a structural equations approach requires an a priori specification of the number of parameters to be estimated in the final model. Since 5–10 subjects per parameter are suggested (Bearden et al. 1982) and we estimated 37 parameters, we judged three independent samples of 370 participants, sampled with replacement from the total sample of 613, sufficient. (See Data Analysis for exact procedure)

Data Collection

Procedure

The data collection occurred over 32 months from 2006–2009. With the exception of a mental status exam of the care recipient, all data were collected through structured interviews with care-givers conducted in English or Spanish by trained interviewers in the participants’ homes.

Instruments

Some of the instruments employed to measure the concepts in Figure 1 were standardized scales; others were constructed and pre-tested for this study.

Care-giver Propensity Variables

The care-giver variables included age, ethnicity, gender, relationship to the care recipient, education and income derived from the survey.

Beliefs about Care-giving Role

This concept involved ethnic patterns related to care-giving. Persons Providing Care is rooted in family values and expresses the care-givers’ opinion about the appropriateness of family members of different gender and relations to perform certain care-giving tasks. We assumed that such attitudes formed the care-giver identity. The Caregiving Roles Instrument developed and pretested for this study (Friedemann 2009) consists of eight items expressing types of care-giving tasks: (1) Visits and rides; (2) walks and exercise; (3) transportation, errands; (4) laundry and meals; (5) bathing; dressing; (6) cleanup after accidental urine and bowel movements; (7) medical procedures; and (8) handling of a confused patient. For each task, the participants indicated what relatives (daughter, daughter-in-law, son, granddaughter, grandson/brother, sister, wife, husband, other relative/friend) and/or paid help they think should or should not do the task if they were available [check yes (1) or no (2)]. The score for Persons Providing Care (range 1 to 10) sums up the different types of helpers that should do all eight tasks if they were available. The pretested reliability of the Caregiving Roles Instrument ranged from 0.93 to 0.99 (Friedemann 2009).

For the variable Agreement with Norm of Caregiving Role, we used the scores for the same eight tasks on the Caregiving Roles Instrument pertaining to the family care-giver’s relationship to the care recipient (e.g. daughter), and deducted the actual tasks performed by the care-giver, also scored on the Caregiving Roles Instrument (see Care-giver Workload below). We then summed up the squared discrepancies to eliminate negative values and to obtain a measure of incongruence between the belief what the culturally ideal role (care-giver identity) should be and the actual performance of the role.

Care Recipient functioning

Measures concerning the functioning of the care recipient included (1) the Montgomery 12-item ADL/IADL Scale measuring physical and instrumental ability with an overall reliability coefficient of 0.86 (Montgomery & Borgotta 1985, Montgomery & Kosloski 2001); (2) The Mini Mental Status Exam (Folstein et al. 1975) as a screen for cognitive status and (3) the Problematic Behavior Scale (Pearlin et al. 1980) measuring the relative’s cooperativeness with the family care-giver. The latter scale has 13 items by which care-givers estimate the number of days in the past week that the relative had exhibited behaviors such as irritability, threatening people and others. Our pretest yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.87.

Care-giver Workload

For Number Care-giver Tasks, we again used the eight tasks of the Caregiving Roles Instrument (Friedemann 2009), this time inquiring which tasks the care-givers actually performed themselves and summed up the tasks checked off.

Care-giver Stress was measured by two scales: (1) the Montgomery Subjective Burden Scale of 10 items (Montgomery & Borgotta 1989, Savundranayagam et al. 2011); and (2) the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) depression scale (Kroenke et al. 2001). The Subjective Burden Scale has two dimensions. Five items of stress burden measure the effect on care-givers’ emotions such as worry, anxiety and depression. The other 5 items of relationship burden address the care-givers’ perception of being taken advantage of or manipulated. Testing the two scales locally, we obtained a Cronbach alpha of 0.78 and 0.80. The PHQ-9 is a 9-item screening tool to assess the severity of depression. Two recent studies with 5,000 multiethnic participants yielded a stable factor structure for all ethnic groups and Cronbach Alpha ranging from 0.79–0.89 (Huang et al. 2006).

Perceived Need for Resources

Perceived Need for Family Assistance was measured by the 8 tasks listed in the Caregiving Roles instrument, asking how many additional hours of family help were needed per week. Perceived Need for (Community) Services entailed a List of 15 discretionary Services (not including home care) offered in the area. Care-givers checked whether they needed each service not at all (1), maybe (2), or definitely yes (3) (Friedemann 2009).

Resource Use

For Use of Informal Help, we once more employed the eight items of the Caregiving Roles Instrument (Friedemann 2009), asking how many hours of assistance care-givers received from family or friends. We assessed the Use of Formal (Community) Services with the same List of 15 local Services (see above). This time, care-givers marked the services they actually used in the last month and we summed up the services checked.

Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the university review board as well as the ethics committee of the participating agencies, if they had one. Care-givers signed an Informed Consent form before the interview took place and the elderly persons also signed a form consenting to a quick mental status exam. Elders unable to sign were not tested. Interviewers visited in pairs for reasons of safety and mutual supervision.

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses

Due to the ethnically diverse sample, we confirmed the reliability and factor structures of all the published and unpublished instruments and inspected the measures for univariate and multivariate normality.

Model development and testing

First, we conducted a series of correlations with the entire sample of 613 participants. This guided the selection of variables serving as indicators to measure the theoretical concepts. With these variables, we conducted an exploratory path analysis using linear regressions along the paths drawn in Figure 1 and constructed a tentative model. To test the pre-determined variables of this tentative model, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 17.0 (Arbuckle 2009) and employed three fit indices to assess the adequacy of each measure inserted in the model: a) the model chi square value (ideally χ2/df < 2.00) (Byrne 2001), b) the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ideally ≤ 0.05 (Hu & Bentler 1999) and c) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), ideally > 0.95 (Hu & Bentler 1999).

Model Confirmation

Following the recommendations of Byrne (2001) we confirmed the fit of the tested model on three independent random samples of 370 participants (sampled with replacement), using the same goodness of fit criteria.

Validity and reliability of instruments

Instrument properties and reliability coefficients are listed in the section Data Collection. All instruments included in the interview schedule had been translated into Spanish, using recommended translating and back-translating procedures (White & Erlander 1992). The instrument developed for this study (Beliefs about Caregiving Role) was pretested for reliability with a mixed ethnic sample of 120 family care-givers. The list of 15 services was found representative and exhaustive for the local area by a team of 6 service professionals.

RESULTS

Description of the Sample

The demographic and family characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. The sample included 228 (37.2%) White non-Hispanic; 77 (12.6%) Black non-Hispanic, predominantly from the Caribbean; 294 Hispanic (48.0%), seven (1.1%) Asian and seven (1.1%) care-givers of a mixed race. Of the Hispanics, 187 originated in Cuba and 109 in South America, Central America and Puerto Rico. The family care-givers ranged in age from 19–98 years with an average of 60.85 years (SD 14.65). They had assisted their relative with physical care for an average of two years and with instrumental care for nine years.

Table 1.

Care-giver Demographic and Family Variables

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 489 | 79.8 |

| Male | 124 | 20.2 | |

| Relationship to Elder | Spouse | 212 | 34.6 |

| Adult Child/In-Law | 338 | 55.2 | |

| Other | 63 | 10.2 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 77 | 12.6 |

| Married | 381 | 62.2 | |

| Divorced/Separated | 117 | 19.0 | |

| Widowed | 38 | 6.2 | |

| Living Situation | Living with elder | 536 | 87.4 |

| Living in own home | 77 | 12.6 | |

| Family members in household | Spouse | 376 | 61.3 |

| 1 or 2 Parents | 280 | 40.8 | |

| Children | 188 | 30.7 | |

| Siblings | 60 | 9.8 | |

| Other relatives/friends | 99 | 16.2 | |

| Education | 8th grade or less | 193 | 31.5 |

| Some high school | 67 | 10.9 | |

| High school graduates | 150 | 24.5 | |

| Advanced education | 89 | 14.5 | |

| College degree | 105 | 17.1 | |

| Missing | 9 | 1.5 | |

| Income | Less than $15,000 | 141 | 23.0 |

| $15,000 to $39,900 | 197 | 32.1 | |

| $40,000 to $60,000 | 91 | 14.8 | |

| More than $60,000 | 150 | 24.6 | |

| Not reported | 34 | 5.5 |

The care recipients were predominantly female (66.6%) and widowed (44.5%). Only 55 (9%) lived by themselves. They ranged in age from 65–103 years with an average of 80.22 years (SD 8.54). Their ailments included aftereffects of accidents, chronic conditions like cancer, cardiac problems, strokes, respiratory illness, Alzheimer’s disease and frailness from old age.

Description of the Model Concepts

This section offers a description of the model variables

Propensity Variables

The demographic information about this sample is listed in Table 1.

Beliefs about Caregiving Role

The family care-givers were generally open to accept help, believing that an average of 6 people (SD 3.54) out of 10 possible family relations could do all possible care-giving tasks on the Care-giving Roles Instrument. The answers ranged from 0–10 persons. On the variable Agreement with Norm of Care-giver Role care-givers scored 3.68 (SD 0.43) on a scale from 1–4, signifying overall high satisfaction with their role.

Care Recipient Functioning

The ADL/IADL score for the patients was 21.65 (SD 6.62) on a possible range of 12 to 36. Since higher scores mean higher functioning, these care recipients were moderately impaired. Their average score on the Mini Mental Status Exam was 17.14 of a possible 30 points. Patients unable to follow directions (25% of the sample) received 0 points without taking the exam. Including these people, care recipients with dementia (scores of < 24) comprised 60%. Nevertheless, the family care-givers reported a relatively low score of 23.33 (SD 7.65) on the average on a range from 14–56 for the care recipients’ problem behaviors.

Care-giver Stress

The average score on the Burden Scale was 21.08 (SD 8.47) points and therefore moderate; the range of the scale was 8–40. The care-giver depression score on the PHQ9 was 5.08 (SD 4.61) on a scale of 0–27. This signified minimal symptoms. Nevertheless, 5.5% of the sample had moderately severe depression of 15 points or more with one person scoring 20 points, meaning severe depression (Hueng et al. 2006).

Care-giver Workload

Of the eight tasks listed, the family care-givers performed an average of 4.5 tasks daily. This amounted to almost 17 hours per week, somewhat less than the national average of 21 hours (Gibson & Houser 2007). The time commitment would have been much higher, however, if hours for supervision had been added for care-givers of persons with severe dementia.

Perceived Need for Resources

Of the possible 15 services on the list, family care-givers were asked whether they needed the services (1= Definitely No; 2=Maybe; 3=Definitely Yes). Their average score on the range of 15–45 was 29.03 (SD 7.48). Care-givers who had family help reported that they would like an average of 1.99 (SD 3.07) hours of additional help.

Resource Use

Of a possible 15 services, family care-givers used only 1.26 (SD 2.20) on the average and the use of those services was only 6 days or times per month. Family help was 5.76 hours (SD 9.88) per week on the average and ranged from 0–56.5 hours.

Model Development

The independent variables (indicators) selected for testing the tentative model (propensity variables, beliefs about care-giving role, care recipient functioning, care-giver stress and workload) (Figure 1) were based on our conceptual model (Figure 1) derived from Montgomery and Kosloski’s (2009) Caregiver Identity Theory and the literature. For these indicators to serve as predictors, they needed to correlate with the outcome variables Perceived Need for Services and Family Help (perceived need for resources); and Number of Services Used and Actual Hours of Family Help (resource use). We therefore tested the paths indicated with arrows in the conceptual model pictured in Figure 1. Table 2 lists the paths in italics and indicators that yielded significant findings in linear regressions, individually and as groups, relative to the concepts in the conceptual model. Based on their coefficients of determination (R2) that shows the percentage of variance explained, the strongest predictors were the care recipients’ ADL/IADL and Problem Behaviors. Weak predictors throughout were the propensity variables and the care recipients’ Cognitive Status.

Table 2.

Regressions of Model Variables

| Independent Variables | Dependent Variables | β | p | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG Propensity Variables ➝ Beliefs about Care-giving Role | ||||

| Gender | Agreement with Norm of Care-giver Role | 0.137 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| Gender + Relationship | Agreement with Norm of Care-giver Role | 0.152+ −.089 <.001 | 0.03 | |

| Ethnicity | Persons Proving Care | 0.145 | <.001 | 0.03 |

| Beliefs About Care-giving Role ➝ Care-giver Workload | ||||

| Agreement with Norm of Care-giver Role | Number Care-giver Tasks | 0.117 | 0.004 | 0.12 |

| Beliefs About Care-giving Role ➝ Care-giver Stress | ||||

| Persons Providing Care | Perceived Burden | −.095 | 0.019 | 0.01 |

| Persons Providing Care | Depression | −.150 | 0.033 | 0.02 |

| Care Recipient Functioning ➝ Care-giver Workload | ||||

| ADL/IADL | Number Care-giver Tasks | −.501 | <.001 | 0.25 |

| Cognitive Status | Number Care-giver Tasks | −.271 | <.001 | 0.07 |

| Problem Behaviors | Number Care-giver Tasks | 0.355 | <.001 | 0.13 |

| ADL/IADL+ Cogn. Status+Problem Behaviors | Number Care-giver Tasks | −.492+ 0.097+.182 | <.001 | 0.29 |

| Care Recipient Functioning ➝ Care-giver Stress | ||||

| Problem Behaviors | Perceived Burden | 0.455 | <.001 | 0.19 |

| Cognitive Status | Perceived Burden | − 0.137 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| ADL/IADL | Perceived Burden | −.213 | <.001 | 0.05 |

| Problem Behaviors+ Cogn. Status+ ADL/IADL | Care-giver Perceived Burden | 0.428+ 0.065+ 0.051 | <.001 | 0.19 |

| CR Problem Behaviors | Care-giver Depression | 0.400 | <.001 | 0.21 |

| Care-giver Workload ➝ Perceived Need for Resources | ||||

| Number Care-giver Tasks | Perceived Need for Services | 0.357 | <.001 | 0.13 |

| Number Care-giver Tasks | Perceived Need for Family Help | 0.330 | <.001 | 0.11 |

| Care-giver Stress ➝ Perceived Need for Resources | ||||

| CG Perceived Burden | Perceived Need for Services | 0.406 | <.001 | 0.14 |

| CG Depression | Perceived Need for Family Help | 0.210 | 0.002 | 0.04 |

| Care-giver Workload ➝ Resource Use | ||||

| Number Care-giver Tasks | Number Services Used | 0.091 | 0.024 | 0.09 |

| Number Care-giver Tasks | Actual Hours of Family Help | 0.209 | <.001 | 0.11 |

| Care-giver Stress ➝ Resource Use | ||||

| Perceived Burden | Number Services Used | 0.147 | <.001 | 0.02 |

| Depression | Number Services Used | 0.164 | 0.019 | 0.03 |

| Perceived Need for Resources ➝ Resource Use | ||||

| Perceived Need for Services | Number of Services Used | 0.224 | <.001 | 0.22 |

| Perceived Need for Family Help | Actual Hours of Family Help | 0.118 | 0.004 | 0.12 |

Model Testing

The Tentative Model

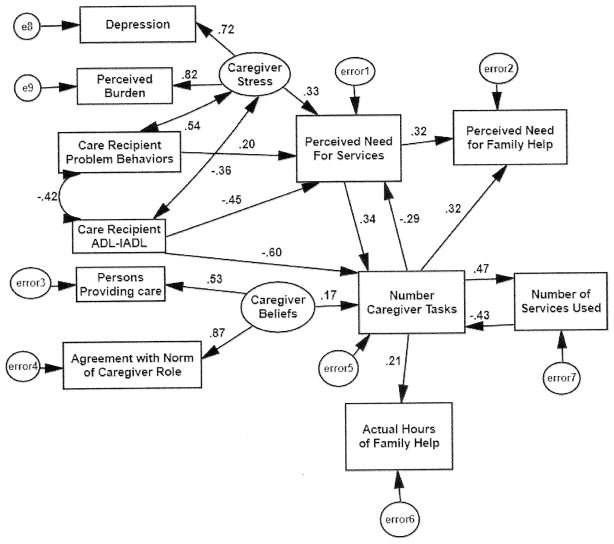

Based on the above established path model, we tested a potential SEM model with confirmatory analyses. For the sake of fit, as recommended by Cohen (1988), we eliminated weak predictors. The adjusted SEM model tested on the full sample of 613 is shown in Figure 2. In this model, compared with the conceptual model (Figure 1), propensity variables had to be excluded. The concept care-giver beliefs about the care-giving role (Figure 1) yielded a composite of Persons Providing Care and Agreement with Norm of Care-giver Role (Figure 2). Care recipient functioning (Figure 1) was represented in the tentative model by two indicators, Care Recipient ADL-IADL and Problem Behaviors (Figure 2) and care-giver stress (Figure 1) by Depression and Burden (Figure 2). Care-giver workload (Figure 1) was measured by Number Care-giver Tasks performed (Figure 2). Perceived Need for Resources (Figure 1) was represented in the tentative model by Perceived Need For Services and Perceived Need for Family Help (Figure 2). Resource Use (Figure 1) in the tentative model was measured by Actual Hours of Family Help and Number of Services Used (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Final SEM Model (N = 613)

In the tentative model (Figure 2), the most significant predictor of Care-giver Stress was the Care Recipients’ Problem Behaviors. The largest predictive coefficient of Number Care-giver Tasks (care-giver workload) was the Care Recipients’ ADL/IADL scores. In comparison, Care-giver Beliefs had a relatively small but statistically significant effect on the same variable. While the care-givers’ workload, as expected, was predicting Family Help and Number Services Used, the expected path between perceived need for resources and resource use (Figure 1) could not be maintained in the tentative model. Thus, perceived Need for Family Help or Need for Services was not connected to the actual use of these resources. All regression coefficients remaining in the model were statistically significant and most fit statistics for the tentative model surpassed the ideal criteria, as shown in Table 3, Full Model.

Table 3.

Goodness of Fit Tests for Total Sample, Three Random Samples and Demographic Groups

| Sample | N | ChiSquare | CFI* | RMSEA** | 90% CI | Model p | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Ideal Criteria | < 2.00 | ≥ 0.95 | ≤ 0.05 | 0.500 (.10)*** | < 1.00) | ||

| Full Model | 613 | 1.864 | 0.977 | .038 | 0.024 – 0.052 | 0.916 | 0.299 |

| Random Sample 1 | 370 | 1.410 | 0.984 | .033 | <.001 – 0.053 | 0.911 | 0.279 |

| Random Sample 2 | 370 | 1.603 | 0.974 | .040 | 0.019 – 0.059 | 0.784 | 0.386 |

| Random Sample 3 | 370 | 1.568 | 0.978 | .037 | 0.013 – 0.056 | 0.854 | 0.238 |

| Spouse Care-givers | 212 | 1.832 | 1.000 | .025 | <.001 – 0.036 | 0.961 | 0.315 |

| Adult Child Care-givers | 338 | 1.838 | 0.960 | .052 | 0.032 – 0.072 | 0.396 | 0.324 |

| Black Care-givers | 77 | Insufficient N; Minimization Not Achieved to Obtain Fit Parameters | |||||

| White NH Care-givers | 228 | 2.016 | 0.935 | .067 | 0.044 – 0.089 | 0.372 | 0.381 |

| Cuban Care-givers | 186 | 1.147 | 0.987 | .028 | <.001 – 0.062 | 0.587 | 0.233 |

| Other Hispanic Care-givers | 108 | 1.390 | 0.940 | .060 | <.001 – 0.098 | 0.650 | 0.249 |

Comparative Fit Index

Root Mean Square Error of Approximation

mean (SD) Values listed are considered acceptable

Model Confirmation

Since we had neither the time nor the resources to collect an additional sample, the next best approach was to test the tentative model with three groups of 370 randomly sampled participants (sampled with replacement). All three analyses yielded satisfactory fit criteria. The fit statistics are listed in Table 3. Recursive Stability Coefficients were all < 0.500 and therefore met the requirement of <1.00. The p value was higher than ideal for all models but considered acceptable (Byrne, 2001). We also tested the model with all ethnic subgroups and with spouse and adult-child care-giver. These model fit statistics are also listed in Table 3. The indices were satisfactory for most sub-groups and the coefficients were statistically significant at p<.05 with the exception of some paths with coefficients of less than 0.30 in the tentative model (see Figure 2). A traditional interpretation is that the variables play a role in the model but for relationships, to be statistically significant, need a larger sample size would be needed. Minimization to obtain fit was not achieved for Caribbean Black family care-givers due to a relatively small sample size of 77.

DISCUSSION

Nationwide, an estimated 30–38 million adults (ages 18 and older) provide care to someone. In this sample, most family care-givers had a positive attitude about their role. They were committed to caring for the relatives despite a 60% rate of cognitive deficiencies and had low burden and depression scores on the average. The care-givers’ usage of services was low with 66% not using any. In contrast, only 2.3% reported that they had no need for any services. Thus, the gap between need and usage was large.

What influences the Use of Services?

The patients’ functional deficit was the driving force determining how much family care-givers worked and what resources they needed. Contrary to their hypothesized importance, cultural beliefs only minimally influenced the workload of family care-givers and had no direct effect on the use of resources. Other researchers (Mausbach et al. 2004, Robinson et al. 2005,Williams 2005, Scharlach et al 2008) also found that family care-givers responded to patient needs independently of cultural beliefs. Thus, irrespective of cultural differences, the primary motivation to care was the elders’ disabilities and need for care, a result salient across ethnicities.

Even though the average family care-giver’s burden and depression were mild, the patients’ problem behaviors and functional limitations clearly created stress in some care-givers and highly stressed care-givers were more burdened and expressed a greater need for services. Confirming findings of other researchers (Cormac & Tihanyi 2006), problematic patient behaviors triggered stress reactions in family care-givers who felt a greater need for services to relieve the situation.

Cultural beliefs about care-giving were of some importance in the prediction of how much family care-givers worked. This finding agrees with the care-giver identity theory (Montgomery & Koslosky 2009) and implies that the perception of the role of a family care-giver is derived from a cultural understanding of family duties.

In addition to the care recipients’ functional status, three other factors influenced the family care-givers’ perception of need for services: (1) care-giver stress; (2) the patients’ problem behaviors; and (3) care-giver workload. The first two relationships seem logical. The relationship between the family care-givers’ workload and their perception of service need, however, was recursive. Understandably, in all groups, a greater need for services appeared when the workload of the care-givers was heavy. Seemingly against logic, however, with a growing workload, family care-givers reported less need for services. Perhaps, a response of resignation due to their inability to access services may have been a reason. Nevertheless, an explanation is difficult to advance and the issue needs further study.

Also not expected was the lack of a direct relationship between the perceived need for services and service use in the final models. In an ideal healthcare environment, one would expect the perception of need to be highly predictive of service use. The lack of such a relationship also seems to point to barriers such as cost, access and lack of knowledge about services mentioned in the literature (Pinquart & Sörensen 2005).

Limitations

To recruit sufficient Black care-givers, we had to drop random recruitment procedures. Despite this, the numbers were insufficient to conduct the final model testing with Black care-givers. Sample size was a limiting factor also for the confirmation of the model, since restricted resources did not allow for a second sample of previously untested participants. Finally, the instruments to measure culture may not have been sufficiently sensitive. Culture as evidenced in the care-giving role may involve yet unexplored variables, such as family relationships (Nolan et al. 2001), gender roles, or work values.

Despite these limitations, some of the findings are particularly relevant for researchers and policy makers. We suspect that a great number of care-givers, mainly from minority groups, cannot sufficiently meet their needs. Unmet needs over time can lead to distress. Therefore, understanding barriers to service use is crucial for tailoring interventions for this population. Barriers may be based on flaws of the health care system or psychosocial factors in care-giving families (Rooney et al. 2006). Future investigations need to examine health care systems internationally and their success in meeting the needs of family care-givers. Other studies should focus on the entire family and factors interfering with caring, such as family-work conflicts or child rearing obligations.

CONCLUSION

The most striking result was the behavioral uniformity of the cultural groups, a finding that suggests that these study results may not be unique to the United States; this may be of interest to the international readers. The effect of the care recipients’ functional limitations was extremely powerful in all ethnic groups. Along the Caregiver Identity Theory (Montgomery & Koslosky 2009), we assume that, across ethnicities, most of the family care-givers develop a strong identity based on the needs of the patients. The finding that care-giver stress is higher with more functional impairment of the patients seems to indicate that the family care-givers’ role identity does not always translate into unquestioned willingness to perform the growing workload. According to Montgomery and Kosloski (2009), role discrepancy needs to be resolved by either adjusting the identity of the family care-giver or changing the situation in a way that the identity can be maintained.

Consequently, nurses need to assess the family care-givers’ role understanding and possible conflict between the ideal role and reality and work with the family in making the necessary changes (e.g. rendering informal help or using assistive services). The findings, however, also suggest a great diversity of role perceptions in all ethnic groups and ask for an individualized approach to care without stereotypical assumptions about cultural beliefs.

The development of successful interventions requires rigorous examination of the needs of family care-givers. As this study shows, needs cannot easily be categorized according to ethnic groups. Instead, the approach of nursing professionals needs to be highly personal and attuned to family-specific beliefs and values. Family care-givers in our study used family help when available. Where families are not available, assistance with accessing services may be of critical importance to decrease care-giver vulnerability.

SUMMARY STATEMENT.

Why is this research needed?

Most research in the area of resource use of care-givers has been conducted with White participants. This study uses a multicultural perspective.

The understanding about minority populations in the U.S. is often stereotypical, thereby leading to bias. The study is needed to show the fallacy of family and care-giving myths.

The emphasis on cultural differences in the literature is great. The study is needed to explore what care-givers have in common.

What are the three key findings?

The elder’s level of disability was the driving force in determining the extent of care-giver involvement in all ethnic groups.

The family care-givers’ perception of need for resources is relative to their workload, their stress level and the elders’ problem behaviors and level of disability.

The family care-givers’ perception of need for resources is related to their workload, but does not predict the actual use of resources.

How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

Instead of treating minority ethnic care-givers differently, nurses and other providers need to assess all care-givers on an individual/family basis and determine their specific needs.

High-quality services for care-givers may be suitable for minority ethnic care-givers, but access to such services needs to be facilitated and services need to be better publicized.

Education should focus on common values and stresses of family care-givers and deemphasize cultural differences.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by Florida International University MBRS grant, SCORE Project NIHSO6GM08205, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

Author Contributions:

- substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data;

- drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. * http://www.icmje.org/ethical_1author.html

Contributor Information

Marie-Luise Friedemann, Email: friedemm@fiu.edu, Professor Emerita, Florida International University, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, 14700 Dade Pine Ave, Miami Lakes, Florida 33014, Telephone 305 826-3264 or 305 310-1602

Frederick L. Newman, Professor Emeritus, Florida International University, Stempel School of Public Health

Kathleen C. Buckwalter, Professor Emerita, The University of Iowa, College of Nursing.

Rhonda J. V. Montgomery, Helen Bader Endowed Chair in Applied Gerontology, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

References

- Adams CE, Horn K, Bader J. Hispanic access to hospice services in a predominantly Hispanic community. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine. 2006;23(1):9–16. doi: 10.1177/104990910602300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 17.0. Chicago: Small Waters Corporation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Schulz R, Yee JL, Jackson S. Negative and positive health effects of caring for a disabled spouse: longitudinal findings from the caregiver health effects study. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15:259–271. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS. 2. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, New Jersey: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chaix B, Navaie-Waliser M, Viboud C, Parizot I, Chauvin P. Lower utilization of primary, specialty and preventive care services by individuals residing with persons in poor health. European Journal of Public Health. 2006;16:209–216. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, New Jersey: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cormac I, Tihanyi P. Meeting the mental and physical healthcare needs of carers. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2006;6(12):162–172. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH. Health care triads and dementia care: integrative framework and future directions. Aging & Mental Health, Suppl. 2001;1:S35–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann ML. The Framework of Systemic Organization: A Conceptual Approach to Families and Nursing. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, California: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann ML. Culture, Family Patterns and Caregiver Resource Use. (Final Study Report, Project SO6GM08205) National Institute of General Medical Sciences; Washington DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Franks MM, Pierce LS, Dwyer JW. Expected parent-care involvement of adult children. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2003;22(1):104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson MJ, Houser A. Valuing the Invaluable: A New Look at the Economic Value of Caregiving (Issue Brief) AARP Public Policy Institute; Washington D.C: Jun, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueng FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Measure Depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2006;21:547. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jolicoeur PM, Madden T. The good daughters: acculturation and caregiving among Mexican-American women. Journal of Aging Studies. 2002;16:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kosloski K, Montgomery RJ, Karner TX. Differences in the perceived need for assistive services by culturally diverse caregivers of persons with dementia. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 1999;18:239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Kosloski K, Schaefer JP, Allwardt D, Montgomery RJ, Karner TX. The role of cultural factors on clients’ attitudes toward caregiving: perceptions of service delivery and service utilization. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2002;21(3/4):65–88. doi: 10.1300/J027v21n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Coon DW, Depp C, Rabinowitz YG, Wilson-Arias E, Kraemer HC, Thompson LW, Lane G, Gallagher-Thompson D. Ethnicity and time to institutionalization of dementia patients: a comparison of Latina and Caucasian female family caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:1077–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJ, Kosloski Caregiving as a process of changing identity: implications for caregiver support. Update on Dementia. 2009;33(1):47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJ, Kosloski C. Unpublished manuscript. Gerontology Center University of Kansas; Lawrence, Kansas: 2001. Executive summary: AOA further analysis and evaluation of the ADDGS project. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJ, Borgotta EF. Family Support Project. Final report to the Administration on Aging. University of Washington Institute on Aging/Long-term Care Center; Seattle, Washington: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJ, Borgotta EF. The effects of alternative support strategies on family caregiving. The Gerontologist. 1989;29:457–464. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving (NAC) & AARP. Caregiving in the US: findings from the National Caregiver Survey. Bethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan M, Keady J, Aveyard B. Relationship-centered care is the next logical step. British Journal of Nursing. 2001;10:757. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2001.10.12.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papastavrou E, Kalokerinou A, Papacostas SS, Tsangari H, Sourtzi P. Caring for a relative with dementia: family caregiver burden. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58(5):446–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:583–594. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and non-caregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging. 2003;18:250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Ethnic differences in stressors, resources and psychological outcomes of family caregiving: a meta-analysis. The Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):90–106. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips L, Luna I, Russell C, Baca G, Lim Y, Cromwell S, Torres de Ardon E. Toward a cross-cultural perspective of family caregiving. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 1996;18:236–251. doi: 10.1177/019394599601800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KM, Buckwalter KC, Reed D. Predictors of use of services among dementia caregivers. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27(2):126–140. doi: 10.1177/0193945904272453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney R, Wright B, O’Neil K. Issues faced by carers of people with a mental illness from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds: carers’ and practitioners’ perceptions. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health. 2006;5(2):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Savundranayagam MY, Montgomery RJ, Kosloski K. A dimensional analysis of caregiver burden among spouses and adult children. The Gerontologist. 2011;51:321–331. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savundranayagam MY, Montgomery RJ, Kosloski K, Little TD. Impact of a psychoeducational program on three types of caregiver burden among spouses. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2011;26(4):388–396. doi: 10.1002/gps.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach AE, Gustavson K, Dal Santo T. Assistance received by employed caregivers and their care recipients: who helps care recipients when caregivers work full time? The Gerontologist. 2007;47:752–762. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.6.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach AE, Giunta N, Chun-Chung CJ, Lehning A. Racial and ethnic variations in caregiver service use. Journal of Aging and Health. 2008;20:326–346. doi: 10.1177/0898264308315426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharlach AE, Kellam R, Ong N, Baskin A, Goldstein C, Fox PJ. Cultural attitudes and caregiver service use: lessons from focus groups with racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Social Work. 2006;47(1/2):133–156. doi: 10.1300/J083v47n01_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Sherwood P. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. American Journal of Nursing. 2008;108(9):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Select Committee on Aging, Subcommittee on Human Services. Exploding the Myths: Caregiving in America (Publication No. 99-611) U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- White M, Erlander E. Translation of an instrument: the US-Nordic family dynamics nursing research project. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 1992;6:161–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1992.tb00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittier S, Scharlach AE, Dal Santo TS. Availability of caregiver support services: Iimplications for implementation of the National Family Caregiver Support Program. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2005;17(1):45–62. doi: 10.1300/J031v17n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch C, Feinberg L. Family and friends as respite providers. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2006;18(3):127–138. doi: 10.1300/J031v18n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams I. Emotional health of black and white dementia caregivers: a contextual examination. Journal of Gerontology. 2005;60B(6):287–295. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.6.p287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabalegui A, Bover A, Rodriguez E, Cabrera E, Diaz M, Gallart A, Gonzalez A, Gual P, Izquierdo MD, Lopez L, Pulpon AM, Ramirez A. Informal Caregiving: Perceived Needs. Nursing Science Quarterly. 2008;21:165–172. doi: 10.1177/0894318408314978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]