Abstract

Seroadaptation describes a diverse set of potentially harm-reducing behaviors that use HIV status to inform sexual decision making. Men who have sex with men (MSM) in many settings adopt these practices, but their effectiveness at preventing HIV transmission is debated. Past modeling studies have demonstrated that serosorting is only effective at preventing HIV transmission when most men accurately know their HIV status, but additional modeling is needed to address the effectiveness of broader seroadaptive behaviors. The types of information with which MSM make seroadaptive decisions is expanding to include viral load, treatment status, and HIV status based on home-use tests, and recent research has begun to examine the entire seroadaptive process, from an individual’s intentions to seroadapt to their behaviors to their risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV and other STIs. More research is needed to craft clear public health messages about the risks and benefits of seroadaptive practices.

Keywords: Serosorting, Seropositioning, HIV/AIDS, Prevention, Risk reduction, Behavioral aspects, Men who have sex with men (MSM), STIs, Seroadaptive practices

Introduction

Seroadaptation is a potential harm reduction strategy that includes a diverse set of behaviors that use HIV status to inform sexual decision-making [1], including serosorting, which is defined by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as “a person choosing a sexual partner known to be of the same HIV serostatus often to engage in unprotected sex, in order to reduce the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV [2].” These community-originating strategies are commonly used by both HIV infected and uninfected men who have sex with men (MSM), but the risks and benefits of these practices are unclear, particularly their effectiveness at preventing HIV transmission. Certain seroadaptive behaviors may result in increased risk of HIV transmission if 1 partner has an undiagnosed HIV infection, and forgoing condom use in actual or perceived seroconcordant partnerships may also result in increased transmission of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs). In order to provide guidance regarding the potential benefits and risks of seroadaptive behaviors, additional research is needed to understand when and why men choose to adopt seroadaptive practices, in what situations they can be effective at preventing HIV transmission, and their potential for increased STI transmission.

An increasing number of studies have addressed seroadaptive practices among MSM. In this review, we first focus on a number of recent studies that have clarified complex definitions of seroadaptation and provided evidence that diverse MSM engage in seroadaptive practices. An emerging agenda in seroadaptation research is the issue of intentionality. Studies are being deployed to capture information on whether prior intentions predict future seroadaptive behaviors as well as behaviors that cannot be identified through sexual histories, such as episodes when men decide not to have sex. Next, the effectiveness of seroadaptive practices as a strategy to prevent HIV transmission remains unclear. We review some recent empirical studies examining seroadaptive effectiveness and discuss the role of mathematical modeling in effectiveness studies. Lastly, we consider the potential for the emergence of home-use HIV tests to alter the landscape of seroadaptive strategies since research suggests that men intend to use these tests with their partners before sex. We end the review with a call to use novel methods to understand the effectiveness of different seroadaptive strategies at preventing HIV transmission and how this may change with the introduction of home-use HIV tests.

Seroadaptive Practices: Definitions and Evidence

For more than 20 years, many MSM have chosen their sex partners and selectively used condoms based on their partners’ perceived HIV status [3-5]. Researchers have attempted to identify the specific steps MSM take to diminish their risk for acquiring or transmitting HIV, and this has led to a number of terms defining diverse ‘harm reduction’ strategies that men employ to protect themselves and their sex partners [6]. Table 1, adapted from Vallabhaneni and colleagues [7••], includes a list of terms and definitions for seroadaptive behaviors from the perspective of an HIV-uninfected individual. Seroadaptation and seroadaptive behaviors are umbrella terms to define sexual decision making based on HIV status [1], which includes serosorting and seropositioning, as well as other behaviors, such as selectively having only oral sex. Serosorting refers to the practice of choosing sex partners or selectively using condoms based on a partner’s perceived HIV status. Strategic or seropositioning refer to selectively practicing insertive or receptive anal sex or selectively using condoms in certain positions based on a partner’s HIV status. Men have also chosen to use viral load and treatment status to negotiate whether to have sex or adopt a certain role [8-10]. As we promote treatment as prevention, this practice may increase as more MSM become aware that antiretroviral therapy reduces the likelihood of transmission. Lastly, some men make sexual agreements with their main sexual partners about acceptable sexual behaviors with additional outside partners [11], a seroadaptive strategy that is becoming more recognized in the scientific community [12-15]. Negotiated safety is a seroadaptive practice, in which men in a partnership agree to practice safe sex with outside partners so that they can have sex without condoms together [13, 16].

Table 1.

Seroadaptive practices defined from the perspective of an HIV-uninfected man who has sex with men

| Sexual behavior a | |

|---|---|

| No UAI | No sex of any kind, only oral sex, or consistent condom use during all anal sex |

| Exclusive top | Some UAI if insertive, no receptive anal intercourse |

| Unprotected top | UAI only if insertive, condom protected receptive anal intercourse |

| Pure serosorting | Both insertive and receptive UAI with perceived HIV-negative partners only |

| Condom serosorting | Both insertive and receptive UAI with perceived HIV-negative partners; condom protected anal intercourse with potentially discordant partners |

| Pure seropositioning | Some UAI, but only insertive anal intercourse with potentially discordant partners |

| Condom seropositioning | Receptive UAI with perceived HIV-negative partners, condom protected anal intercourse with potentially discordant partners |

| No seroadaptive behavior | Some UAI; some receptive anal intercourse with potentially discordant partners with or without condoms |

| Nonconcordant receptive UAI | Receptive UAI with potentially discordant partners |

The definitions in this table are from the perspective of an HIV-uninfected man, whereas HIV-infected men could do the inverse, such as purposely choosing to be the receptive male during UAI

A number of studies over the years [10, 17-23], including many since 2012 [7••, 8, 11, 28-32, 33••, 34-36, 37•, 38-41], provide evidence that men engage in seroadaptation and estimate prevalence of seroadaptive behaviors among unique populations of MSM. Studies conducted in the US, Europe, and Australia have found that 14 %–44 % of HIV positive MSM and 25 %–38 % of HIV negative MSM serosort, and that 14 %–35 % and 6 %–15 %, respectively, seroposition [6, 42-44].

A few recent papers have identified high-risk subgroups that have adopted seroadaptive practices, recognizing that, although imperfect, seroadaptation may be used as a strategy intended to reduce HIV risk in settings with significant barriers to prevention strategies known to be effective, such as consistent condom use or pre-exposure prophylaxis [26, 27•]. First, in a study of low income MSM in Los Angeles, HIV-positive men but not HIV-negative men engaged in serosorting more than would be expected by chance [27•]. Both groups seemed to adopt seropositioning as a risk management strategy: HIV-positive men were more likely to report unprotected receptive anal intercourse, while HIV-negative men were more likely to engage in unprotected insertive anal intercourse. Another recent study demonstrated that low income, urban Native American MSM also practice seroadaptive strategies, but the authors raise concern that these strategies may not be protective since half of the men did not disclose their HIV status and very few had a recent HIV test [26].

Intentionality of Seroadaptive Behaviors

Whether men intend to practice seroadaptive behaviors and how these behaviors change over time are important emerging themes in seroadaptation literature. Indeed, the CDC definition of serosorting implies intent, since the choice of a partner of the same status is made “in order to reduce risk” [2]. Most studies examine patterns of men’s sexual risk behavior as a function of their own and partner’s HIV status, which provides data for a behavioral definition of seroadaptation. Studies with behavioral definitions of seroadaptation are limited in assessing whether these men are specifically and purposely using these strategies to reduce the risk of acquiring or transmitting HIV [11]. Second, most evidence of seroadaptation is based upon sexual histories and can only capture sex that occurred, a strategy that may underestimate the effectiveness of seroadaptive practices that include men choosing not to have sex with discordant partners. Emerging research recognizes that capturing intentional seroadaptive behavior is critical in evaluating the prevalence and correlates of these practices as well as in assessing the effectiveness of seroadaptation for HIV prevention. More research is needed to understand the dynamic seroadaptive process from intentions to sexual behavior to HIV transmission risk.

An innovative longitudinal study of MSM in San Francisco found that some, but not all, seroadaptive behaviors were the result of consciously adopted HIV risk-reduction strategies [33••], thereby confirming the distinction between measuring behaviors consistent with seroadaptive strategies and measuring purposeful decisions to adopt behaviors designed to diminish HIV risk. The authors collected data to determine seroadaptation intentions at baseline and to define seroadaptive behaviors practiced by MSM during follow-up at 12 months. They found that some, but not all, MSM who practiced seroadaptive behaviors based on sexual histories did so intentionally. Men who intended to adopt these behaviors did so more often than those who did not, particularly in the case of pure serosorting among HIV-negative men and seropositioning among HIV-positive men. However, many men did engage these behaviors without specifically intending to do so, and although condom serosorting was intended by many, very few HIV-positive or negative men actually carried it out [33••].

Although not designed to directly measure intentionality, studies that compare patterns of seroadaptive behavior before and after HIV seroconversion can indirectly assess intentionality by controlling for some (but not all) external factors that may influence patterns of seroadaptive behaviors [24, 45]. Men who have sex with men in San Francisco with recent HIV infection appeared to rapidly adopt seroadaptive practices and maintain them over time [24]. The most drastic sexual risk behavior change was a decline in insertive UAI, especially with potentially discordant partners, which reduces the likelihood of sexual transmission to uninfected partners. In a cohort of MSM in Southern California, the percent of men reporting an HIV-infected partner increased after diagnosis of recent infection [45]. One limitation of this type of study design is that it assumes that behavioral patterns at the time of HIV infection represent typical behavioral patterns of the individual while he was uninfected. Indeed, it is possible that risk behaviors prior to HIV infection are not typical and that atypical increased levels of risk lead to infection. Longitudinal studies comparing behavior in periods prior with the last negative test with behaviors after diagnosis or comparing risk behaviors before and after diagnosis with a chronic infection may therefore be more suitable for examining the intentionality of seroadaptive behaviors after diagnosis.

Last, a study of seroadaptive practices using data from 4 longitudinal HIV prevention studies found that 25 % of men were classified into the same seroadaptive strategy, according to self-reported behaviors, across 5 or more study visits [7••]. This may represent indirect evidence of intention, but only if their partnership conditions, upon which they were making seroadaptive decisions, were the same across all study visits.

The next logical question in the intentionality literature is to test whether HIV risk behaviors differ between intentional and unintentional seroadapters. For example, if serosorting behaviors are intended, then men who intend to engage in these behaviors may be more likely to engage in UAI with seroconcordant partners than men who unintentionally serosort. However, a study using data from a national, online survey of MSM found no support for this hypothesis [25]. Their secondary analysis of the national data found that most men in seroconcordant HIV-negative relationships and about half of men in seroconcordant HIV-positive relationship intended to be in such a partnership. However, for both HIV-positive and negative men, intentional seroconcordance was not more strongly associated with UAI in seroconcordant partnerships than any seroconcordance regardless of intent. The authors conclude that intentionality may not be critical in understanding the relationship between seroconcordance and UAI and that future studies should continue to include a behavioral measure of serosorting and not rely solely on intentional measures [25]. However, the relationship between intentions and enacted behaviors needs to be examined for other seroadaptive behavior beyond serosorting, and the many factors that may influence an individual’s decision making process from intent to enacted behavior, including a partner’s behavior or intentions, need to be better understood.

More research is clearly needed on each step of the process of seroadaptive behaviors and effectiveness: from intention, to uptake, maintenance, and last, risk of HIV transmission [7••]. Longitudinal studies can identify intentional switching of adaptive strategies, or inconsistent use [34], but this research will need to account for a number of external factors that may influence each step of the seroadaptive process. Partner choice may be a function of who is eligible. Men may be more likely to choose an HIV-negative partner by chance since in most populations, HIV-negative men outnumber HIV-positive men. HIV-positive MSM may adopt seropositioning as a risk reduction strategy more often than serosorting to enable them to expand their choice of potential partners while still reducing risk of HIV transmission [33••]. Type of sex (oral vs anal), sexual position (top, bottom, or both (flipping)), or selective condom use may be a function of demographics, sexual networks, attraction, preferences, age, partnership types and venue [46]. For example, HIV infected men may more often be receptive in discordant relationships because they are seropositioning. However, HIV infected MSM may also be more likely to be receptive because men who frequently practice receptive anal sex are more likely to acquire HIV. A large study is ongoing at the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD Clinic to bridge the intentionality research with seroadaptation effectiveness by elucidating the context of seroadaptive decision-making at each step in the process of partnership formation [46] and testing the association between intentionally adopted seroadaptive behaviors and the risk of testing positive for HIV and bacterial STIs. This work will account for both intentionality as well as other key factors in order to accurately represent the true prevention efficacy of seroadaptive behaviors as an active HIV risk reduction strategy.

Effectiveness of Seroadaptive Behavior to Reduce HIV Transmission by HIV-Negative MSM

Among HIV-positive men, adoption of seroadaptive practices is fairly effective at reducing HIV transmission [17, 23]; however, seroadaptive behaviors can increase STI transmission [35, 36, 47] and has the potential for risk of HIV superinfection [48]. The effect of seroadaptive behaviors by HIV-negative men on HIV acquisition and STI risk is less understood. In order for seroadaptive practices to be effective, an individual needs to correctly identify not only their own HIV status but that of their partner’s as well. In the United States, about 20 % of individuals infected with HIV do not know their status [49], and even among persons who are aware of their infection, disclosing their status may be challenging.

Seroadaptive behaviors typically rely on a partner’s self-reported serostatus or other potentially unreliable alternate measures of a partner’s status, such as how a partner looks, assumptions that a partner will disclose his status if he perceives himself to be discordant, or serostatus reported in online profiles [50]. How accurately each individual in a partnership knows his own serostatus and whether partners are able to communicate their status with each other will, to a large extent, determine the effectiveness of seroadaptive behaviors at preventing HIV transmission. Couples counseling [51, 52] and home testing with partners, discussed further below, are potential methods for increasing the effectiveness of seroadaptive behaviors by improving communication and serostatus disclosure within partnerships.

A significant challenge in evaluating the effectiveness of seroadaptive behaviors is that studies over the years define seroadaptive behaviors differently and compare their effectiveness against different behaviors. Some of the earliest case control and prospective longitudinal studies of MSM evaluating risks for HIV acquisition reported higher odds ratios for having unprotected sex with known HIV positive partners than for having unprotected sex with partners thought to be HIV negative [53-55]. More recent studies evaluated the effectiveness of seroadaptive strategies more broadly, suggest that serosorting is associated with a lower risk of HIV acquisition than non-concordant unprotected anal intercourse (UAI), but a higher risk than consistent condom use [7••, 16, 21, 37•, 56]. The EXPLORE study found slightly lower HIV incidence among MSM who condom serosorted, but not among MSM who practiced seropositioning [56]. Another study of HIV-negative men in Sydney, Australia showed that among MSM who self-identified as serosorters and engaged in UAI with a seroconcordant regular partner had an increased risk of seroconversion compared with those who did not engage in UAI [16].

Using data from 4 longitudinal HIV prevention studies of MSM from North America, a recent study assessed the association of a wide range of seroadaptive practices with HIV acquisition [7••]. Pure serosorting, condom serosorting, and condom seropositioning were each associated with increased risk of HIV compared with no UAI. However, MSM who reported these behaviors as well as other seroadaptive practices were at lower risk than MSM who reported no seroadaptive strategies, defined as receptive anal sex with HIV-positive or HIV-unknown partners. Behavioral data and data on HIV seroconversion from men were categorized in 6-month intervals. Interestingly, nearly half of intervals were categorized as no UAI, which includes oral sex or 100 % condom protected anal intercourse, yet more than a quarter of HIV seroconversions occurred during these intervals. Most likely this result is due to under-reporting of UAI. A number of other studies have also suggested that seroadaptive behaviors are generally safer than no seroadaptive practices, but serosorting is riskier than no UAI at all [16, 21, 57]. Similar to a study among MSM in Sydney, Australia, having only insertive sex, with or without condoms, appeared to be safer than no UAI [58]. This may be due to either the fact that insertive anal intercourse is associated with less risk of HIV acquisition than receptive anal intercourse or due to under-reporting of UAI. A limitation of this and most other studies of seroadaptive behaviors is that they rely on self-reported measures of intentions, serostatus of partners, reports of disclosure, and sexual behaviors. This may affect our ability to accurately determine the prevalence, costs, benefits, and population-level effects of these behaviors.

Differences in prevalence of seroadaptive behaviors and the efficacy of seroadaptation by race have been debated in the last year. Black MSM are disproportionately affected by HIV, but individual sexual risk behavior such as number of partners or rates of UAI do not explain racial disparities [59]. In a recent secondary analysis of data from the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD Clinic, serosorting was common among White and Black MSM, but serosorting was only associated with a significantly lower risk of testing HIV positive for White MSM [37•]. The authors were unable to identify why serosorting might be less effective for Black MSM. One hypothesis is that rates of testing might differ by race, resulting in higher rates of undiagnosed infections among Black MSM [60]; however, testing histories did not appear to differ by race among MSM attending this clinic. The authors postulate that race assortative sexual mixing and infrequent disclosure among blacks—HIV-positive black MSM may be less likely to discuss serostatus before UAI [29]—could explain why serosorting was not protective among black MSM in their study [37•]. In contrast, other studies found that serosorting among Black MSM was an effective risk reduction strategy compared with UAI without seroadaptive strategies [7••, 57]. The reason for these inconsistent findings is not evidently clear, but might be due to true differences in study populations (Seattle vs New York and Philadelphia).

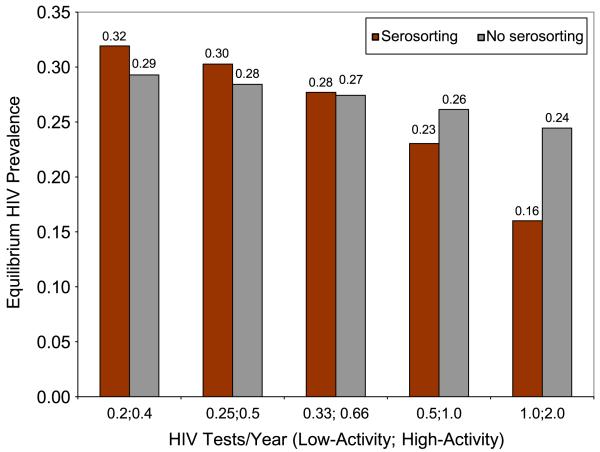

To measure the true effectiveness of seroadaptation, one would need to compare HIV risk among a population of men who practice seroadaptive behaviors, including forgoing sex acts with potentially serodiscordant partners, to a counterfactual scenario in which these same (or similar) men did not practice seroadaptive behaviors. A mathematical model may be the most effective way to explore these hypothetical counterfactuals and predict the impact of seroadaptation on HIV incidence. Mathematical modeling is also an important tool to understand the potentially unintuitive ways that seroadaptive behaviors may affect HIV transmission. In the past, mathematical models have contributed to the understanding of how the acute stage of HIV infection and the proportion of undiagnosed HIV-positive men in a population may influence the effectiveness of serosorting. One of the first models in the field suggested that serosorting is not an effective prevention strategy, and that, because of the high transmission probability associated with acute infection, the practice may pose greater risk than having UAI with a partner with established infection [61]. This simple multiplicative model sparked a number of additional, more complex mathematical models of serosorting. Mathematical models that followed suggest that serosorting can either increase or decrease a person’s risk of acquiring HIV depending on the accuracy of HIV status disclosure, which largely depends on the population’s HIV testing frequency [62-65]. One model found serosorting to be partially effective in the context of Seattle, Washington [65], while another model published within weeks suggested it may be a harmful strategy generally [64]. The results at first glance seemed contradictory, but the two modeled different populations, with Seattle having a much higher rate of testing than is found in many other locations. Figure 1 shows how the relationship between serosorting and HIV prevalence varies significantly by testing frequency. In populations with low rates of testing, serosorting is predicted to be detrimental, whereas in populations with frequent testing, serosorting may be beneficial [62]. Both models conclude that if the percent of HIV-infected MSM unaware of their infection is greater than 20 % or if testing were less frequent than reported in the Seattle area, serosorting may increase transmission [62, 63]. Indeed, the prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection among MSM in the U.S. may be well above 20 % in most cities [66], suggesting that serosorting may not be an effective harm reduction strategy in many settings. However, the proportion of MSM unaware of their infection is lowest in Seattle, around 7 %. At this level, both models suggest that serosorting might be beneficial.

Fig. 1.

Estimated relationship between serosorting, testing frequency, and HIV prevalence from a model simulation of HIV transmission dynamics among men who have sex with men. Serosorting is predicted to have little impact on equilibrium HIV prevalence or risk of HIV acquisition when low- and high-activity MSM test every 3 and 1.5 years, respectively. Serosorting is potentially protective at high testing frequencies and has a small deleterious effect at lower testing frequencies. Low-activity men are defined as having 1 anal sex partner per year, and high-activity men are defined as having an average of 10 anal sex partners per year. Data for the model are from 2003 random-digit-dial study of MSM in Seattle. The figure is adapted from a previously published model of serosorting among MSM [62, 65]

Mathematical models should continue to be used to examine the role of seroadaptation and HIV transmission dynamics, incorporating more comprehensive seroadaptive strategies, and accounting for the rapidly changing landscape of HIV testing.

Novel Testing Strategies and Seroadaptation

The efficacy of serosorting and seroadaptive behaviors is decidedly dependent on HIV testing frequency. It is clear that the more accurately individuals in a population know their true HIV status, the more efficacious seroadaptive strategies will be [62, 64]. A number of new testing strategies and types of tests are available to MSM in the US, including antigen-antibody combination assays, couples-based HIV testing, and home-use tests. Changes in types and frequency of HIV testing will influence seroadaptive strategies in significant ways; here we focus on home-use testing.

The first home-use HIV test, the OraQuick In-Home HIV Test (OraSure Technologies, Inc.), became available over-the-counter in October 2012. Although these tests have been approved for self-testing, research suggests that MSM will also test with sex partners to inform sexual decision-making, which we call point-of-sex testing [67-69]. Home-use tests offer the opportunity to base seroadaptive decisions on the results of tests conducted prior to sex instead of self-disclosed or implied HIV status. If MSM trust the results of a partner’s home-use test more than his self-reported status and are therefore more likely to engage in UAI after testing together prior to sex, the decreased sensitivity of the available home-use test during the highly infectious acute stage may lead to increased transmission of HIV [70]. However, home-use tests may increase individual testing frequency and results from point-of-sex testing may be more accurate than the self-reported or implied HIV status of a sex partner, which may decrease UAI between serodiscordant partners.

Two studies have examined point-of-sex testing and its potential impact on seroadaptive behaviors. In a small pilot study, 27 high risk MSM in New York were given home-use tests to use with their partners [67] and were monitored weekly for 3 months. Participants of the study found the tests acceptable, and were likely to use home tests with their sex partners. In 100 sexual partnerships, there was no evidence that men were more likely to engage in UAI after testing, and no sexual intercourse was reported in 10 partnerships where a partner had a reactive antibody test. A larger trial of home self-testing among high risk MSM in Seattle (the iTest Study) examined intentions to point-of-sex test. One-quarter of high risk MSM reported that they would be very likely to test with a partner prior to sex, and men were twice as likely to report being very likely to engage in UAI if both partners tested negative at home than if a partner only disclosed being negative. Participants’ likelihood of using home-use tests for point-of-sex testing depended on how long the test takes to produce results, the type of sex partner, and the perceived risk of the encounter [71].

As with the early literature on serosorting, mathematical modeling can be used to elucidate important components of home-use testing and its influence on the effectiveness of seroadaptation for HIV prevention. One mathematical model has quantified potential risk reduction that could be attained by using home-use tests to screen sexual partners vs using condoms in different proportions of anal intercourse occasions among MSM. They find that the benefit of home-use tests is very closely tied to underlying HIV incidence in the population as well as rates or supplementation of condom use [72, 73]. Much more work, including additional mathematical modeling, is needed to determine whether home-use tests can be safely used to increase the accuracy of seroadaptive behaviors.

Conclusions

Recent research suggests that many different populations of MSM are engaging in seroadaptive behaviors, and many are doing so intentionally. In general, seroadaptive behaviors seem to be associated with less risk compared with no seroadaptive behavior, but a number of seroadaptive behaviors are associated with increased risk compared with no UAI. Emerging research is testing whether accounting for intentionality will influence estimates of risk associated with seroadaptation. The CDC does not recommend serosorting as a safer sex practice [74]. Whether other seroadaptive strategies should be encouraged, discouraged, or ignored for MSM is a different question and depends on whether they are effective HIV prevention strategies [25]. Not surprisingly, health departments and HIV prevention programs increasingly wrestle with how to advise MSM about seroadaptation [75], and at least 1 study has investigated an intervention to promote seroadaptive practices in HIV-negative MSM [76].

New and innovative methods are needed to understand complex dynamics of seroadaptation and the effectiveness of preventing HIV transmission at individual and population levels. Mathematical modeling is a particularly useful tool to explore counterfactual scenarios of seroadaptation, since its efficacy at preventing HIV infection is a function of actual and avoided risk, as well as perceived and actual serostatus. Perceived and actual serostatus is in turn dependent on underlying testing rates, testing technologies, strategies for disclosing HIV status, and HIV prevalence in the community. Furthermore, the types of information with which men are making seroadaptive decisions, such as viral load and treatment status, and how the information is obtained, such as home-use HIV testing, is constantly changing. The public health community needs to keep abreast of the changing face of seroadaptation among MSM and craft clear public health messages about these practices as HIV risk reduction strategies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NICHD (R00 HD057533) and the UW Center for AIDS Research Sociobehavioral and Prevention Research Core (P30 AI027757). Additional support was provided by a NICHD research infrastructure grant (5R24HD042828), to the UW Center for Studies in Demography & Ecology. The authors would like to thank Christine Khosropour for support with the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Susan Cassels declares that she has no conflict of interest. David A. Katz declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Contributor Information

Susan Cassels, Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; Department of Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA; University of Washington, 325 9th Avenue, Box 359931, Seattle, WA 98104, USA.

David A. Katz, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

• Of importance

•• Of major importance

- 1.Snowden JM, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Prevalence of seroadaptive behaviours of men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2004. Sex Transm Infect. 2009;85:469–76. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.036269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control Consultation on serosorting practices among men who have sex with men. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/research/resources/other/serosorting.htm.

- 3.Dawson JM, Fitzpatrick RM, Reeves G, Boulton M, McLean J, Hart GJ, et al. Awareness of sexual partners’ HIV status as an influence upon high-risk sexual behaviour among gay men. AIDS. 1994;8:837–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marks G, Crepaz N. HIV-positive men’s sexual practices in the context of self-disclosure of HIV status. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:79–85. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200105010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoff CC, Stall R, Paul J, Acree M, Daigle D, Phillips K, et al. Differences in sexual behavior among HIV discordant and concordant gay men in primary relationships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:72–8. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199701010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDaid LM, Hart GJ. Sexual risk behaviour for transmission of HIV in men who have sex with men: recent findings and potential interventions. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5:311–5. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a0b86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7••.Vallabhaneni S, Li X, Vittinghoff E, Donnell D, Pilcher CD, Buchbinder SP. Seroadaptive practices: association with HIV acquisition among HIV-negative men who have sex with men. Plos One. 2012;7(10):e45718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045718. This paper provides clear definitions to a number of different forms of seroadaptation. The authors test whether these forms of seroadaptive behaviors may be effective risk reduction strategies, compared with both no seroadaptation strategies or no UAI.

- 8.Horvath KJ, Smolenski D, Iantaffi A, Grey JA, Rosser BR. Discussions of viral load in negotiating sexual episodes with primary and casual partners among men who have sex with men. Aids Care. 2012;24:1052–5. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prestage G, Mao L, Kippax S, Jin F, Hurley M, Grulich A, et al. Use of viral load to negotiate condom use among gay men in Sydney, Australia. Aids Behav. 2009;13:645–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9527-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van de Ven P, Mao L, Fogarty A, Rawstorne P, Crawford J, Prestage G, et al. Undetectable viral load is associated with sexual risk taking in HIV serodiscordant gay couples in Sydney. AIDS. 2005;19:179–84. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200501280-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell JW. HIV-negative and HIV-discordant gay male couples’ use of HIV risk-reduction strategies: differences by partner type and couples’ HIV-status. Aids Behav. 2013;17:1557–69. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0388-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darbes LA, Chakravarty D, Beougher SC, Neilands TB, Hoff CC. Partner-provided social support influences choice of risk reduction strategies in gay male couples. Aids Behav. 2012;16:159–67. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9868-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoff CC, Beougher SC, Chakravarty D, Darbes LA, Neilands TB. Relationship characteristics and motivations behind agreements among gay male couples: differences by agreement type and couple serostatus. Aids Care. 2010;22:827–35. doi: 10.1080/09540120903443384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoff CC, Chakravarty D, Beougher SC, Darbes LA, Dadasovich R, Neilands TB. Serostatus differences and agreements about sex with outside partners among gay male couples. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21:25–38. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoff CC, Beougher SC. Sexual agreements among gay male couples. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39:774–87. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9393-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin FY, Crawford J, Prestage GP, Zablotska I, Imrie J, Kippax SC, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. AIDS. 2009;23:243–52. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb51a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McConnell JJ, Bragg L, Shiboski S, Grant RM. Sexual seroadaptation: lessons for prevention and sex research from a cohort of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. PloS One. 2010;5(1):e8831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei CY, Raymond HF, Guadamuz TE, Stall R, Colfax GN, Snowden JM, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in seroadaptive and serodisclosure behaviors among men who have sex with men. Aids Behav. 2011;15:22–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFarland W, Chen YH, Raymond HF, Binh N, Colfax G, Mehrtens J, et al. HIV seroadaptation among individuals, within sexual dyads, and by sexual episodes, men who have sex with men, San Francisco, 2008. Aids Care. 2011;23:261–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.507748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elford J. Changing patterns of sexual behaviour in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:26–32. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000199018.50451.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Golden MR, Stekler J, Hughes JP, Wood RW. HIV serosorting in men who have sex with men: is it safe? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49:212–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons JT, Schrimshaw EW, Wolitski RJ, Halkitis PN, Purcell DW, Hoff CC, et al. Sexual harm reduction practices of HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men: serosorting, strategic positioning, and withdrawal before ejaculation. AIDS. 2005;19:S13–25. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167348.15750.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Truong HHM, Kellogg T, Klausner JD, Katz MH, Dilley J, Knapper K, et al. Increases in sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk behaviour without a concurrent increase in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: a suggestion of HIV serosorting? Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:461–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vallabhaneni S, McConnell JJ, Loeb L, Hartogensis W, Hecht FM, Grant RM, et al. Changes in Seroadaptive practices from before to after diagnosis of recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men. PloS One. 2013;8(2):e55397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegler AJ, Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM, Rosenberg ES. The role of intent in serosorting behaviors among MSM sexual partnerships. J Acq Immune Def Synd. 2013 doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182a0e880. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson CR, Walters KL, Simoni JM, Beltran R, Nelson KM. A cautionary tale: risk reduction strategies among urban American Indian/Alaska Native men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2013;25:25–37. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27•.Murphy RD, Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Hucks-Ortiz C, Shoptaw SJ. Seroadaptation in a sample of very poor Los Angeles area men who have sex with men. Aids Behav. 2013;17:1862–72. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0213-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balan IC, Carballo-Dieguez A, Ventuneac A, Remien RH, Dolezal C, Ford J. Are HIV-negative men who have sex with men and who bareback concerned about HIV infection? Implications for HIV risk reduction interventions. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42:279–89. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9886-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winter AK, Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM, Rosenberg ES. Discussion of HIV status by serostatus and partnership sexual risk among internet-using MSM in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:525–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318257d0ac. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Boom W, Stolte I, Sandfort T, Davidovich U. Serosorting and sexual risk behaviour according to different casual partnership types among MSM: the study of one-night stands and sex buddies. Aids Care. 2012;24:167–73. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.603285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uuskula A, Abel-Ollo K, Markina A, McNutt LA, Heimer R. Condom use and partnership intimacy among drug injectors and their sexual partners in Estonia. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:58–62. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenberg J. Association between serosorting and HIV risk differs by race among men with male partners. Perspect Sex Repro H. 2012;44(4):272–3. [Google Scholar]

- 33••.McFarland W, Chen YH, Nguyen B, Grasso M, Levine D, Stall R, et al. Behavior, intention or chance? A longitudinal study of HIV Seroadaptive behaviors, abstinence and condom use. Aids Behav. 2012;16:121–31. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9936-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McDaid LM, Hart GJ. Serosorting and Strategic positioning during unprotected anal intercourse: are risk reduction strategies being employed by gay and bisexual men in Scotland? Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:735–8. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31825a3a3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin FY, Prestage GP, Templeton DJ, Poynten IM, Donovan B, Zablotska I, et al. The impact of HIV seroadaptive behaviors on sexually transmissible infections in HIV-negative homosexual men in Sydney, Australia. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:191–4. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182401a2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hotton AL, Gratzer B, Mehta SD. Association between serosorting and bacterial sexually transmitted infection among HIV-negative men who have sex with men at an urban lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health center. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:959–64. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31826e870d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Golden MR, Dombrowski JC, Kerani RP, Stekler JD. Failure of serosorting to protect African American men who have sex with men from HIV Infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:659–64. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31825727cb. This study finds that serosorting is associated with lower risk of testing positive for HIV among White MSM but not Black MSM. The authors provide a nice discussion as to why serosorting effectiveness might differ by race, and compare their findings with other conflicting results.

- 38.Dubois-Arber F, Jeannin A, Lociciro S, Balthasar H. Risk reduction practices in men who have sex with men in Switzerland: serosorting, strategic positioning, and withdrawal before ejaculation. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(5):1263–72. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9868-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YH, Vallabhaneni S, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Predictors of serosorting and intention to serosort among men who have sex with men, San Francisco. Aids Educ Prev. 2012;24:564–73. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2012.24.6.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berg RC. High rates of unprotected sex and serosorting among men who have sex with men: a national online study in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2012;40:738–45. doi: 10.1177/1403494812465032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benotsch EG, Hood K, Rodriguez V, Martin AM, Snipes D, Cejka A, et al. Serosorting assumptions and HIVrisk behavior in men who have sex with men. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43:S268–S. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snowden JM, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Seroadaptive behaviours among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: the situation in 2008. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:162–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.042986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Velter A, Bouyssou-Michel A, Arnaud A, Semaille C. Do men who have sex with men use serosorting with casual partners in France? Results of a nationwide survey (ANRS-EN17-Presse Gay 2004) Euro Surveill. 2009;14(47):1–6. doi: 10.2807/ese.14.47.19416-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Johnson TP, Pollack LM. Sexual risk behavior and drug use in 2 Chicago samples of men who have sex with men: 1997 vs 2002. J Urban Health. 2010;87:452–66. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9432-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gorbach PM, Weiss RE, Jeffries R, Javanbakht M, Drumright LN, Daar ES, et al. Behaviors of recently HIV-infected men who have sex with men in the year postdiagnosis: effects of drug use and partner types. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:176–82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181ff9750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khosropour CM, Golden MR, editors. UW/FHCRC CFAR Sociobehavioral and Prevention Research Core (SPRC) & Public Health-Seattle & King County Brownbag Series. May 28, 2013. Challenges and success in recruiting research study participants from an STD Clinic: evidence from a behavioral risk study of MSM in public health—Seattle and King County STD Clinic. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marcus U, Schmidt AJ, Hamouda O. HIV serosorting among HIV-positive men who have sex with men is associated with increased self-reported incidence of bacterial sexually transmissible infections. Sex Health. 2011;8:184–93. doi: 10.1071/SH10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Redd AD, Quinn TC, Tobian AA. Frequency and implications of HIV superinfection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:622–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control HIV Surveillance—United States, 1981-2008. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:689–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, O’Connell DA, Karchner WD. A strategy for selecting sexual partners believed to pose little/no risks for HIV: serosorting and its implications for HIV transmission. Aids Care. 2009;21:1279–88. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stephenson R, Sullivan PS, Salazar LF, Gratzer B, Allen S, Seelbach E. Attitudes towards couples-based HIV testing among MSM in 3 US cities. Aids Behav. 2011;15(Suppl 1):S80–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9893-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wagenaar BH, Christiansen-Lindquist L, Khosropour C, Salazar LF, Benbow N, Prachand N, et al. Willingness of US men who have sex with men (MSM) to participate in Couples HIV Voluntary Counseling and Testing (CVCT) PloS One. 2012;7:e42953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Buchbinder SP, Vittinghoff E, Heagerty PJ, Celum CL, Seage GR, Judson FN, et al. Sexual risk, nitrite inhalant use, and lack of circumcision associated with HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:82–9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134740.41585.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koblin BA, Husnik MJ, Colfax G, Huang YJ, Madison M, Mayer K, et al. Risk factors for HIV infection among men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20:731–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000216374.61442.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thiede H, Jenkins RA, Carey JW, Hutcheson R, Thomas KK, Stall RD, et al. Determinants of recent HIV infection among Seattle-area men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 1):S157–64. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Philip SS, Yu XS, Donnell D, Vittinghoff E, Buchbinder S. Serosorting is associated with a decreased risk of hiv seroconversion in the EXPLORE study cohort. PloS One. 2010;5(9):e12662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marks G, Millett GA, Bingham T, Lauby J, Murrill CS, Stueve A. Prevalence and protective value of serosorting and strategic positioning among Black and Latino men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:325–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181c95dac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van de Ven P, Kippax S, Crawford J, Rawstorne P, Prestage G, Grulich A, et al. In a minority of gay men, sexual risk practice indicates strategic positioning for perceived risk reduction rather than unbridled sex. Aids Care. 2002;14:471–80. doi: 10.1080/09540120208629666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Millett GA, Peterson JL, Wolitski RJ, Stall R. Greater risk for HIV infection of black men who have sex with men: a critical literature review. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1007–19. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oster AM, Wiegand RE, Sionean C, Miles IJ, Thomas PE, Melendez-Morales L, et al. Understanding disparities in HIV infection between black and white MSM in the United States. AIDS. 2011;25:1103–12. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283471efa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Butler D, Smith D. Serosorting can potentially increase HIV transmissions. AIDS. 2007;21:1218–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32814db7bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cassels S, Menza TW, Goodreau SM, Golden MR. Available evidence does not support serosorting as an HIV risk reduction strategy: author’s reply. AIDS. 2010;24:936–8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337afa9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heymer KJ, Wilson DP. Available evidence does not support serosorting as an HIV risk reduction strategy. AIDS. 2010;24:935–6. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337b029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilson DP, Regan DG, Heymer KJ, Jin FY, Prestage GP, Grulich AE. Serosorting may increase the risk of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37:13–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b35549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cassels S, Menza TW, Goodreau SA, Golden MR. HIV serosorting as a harm reduction strategy: evidence from Seattle, Washington. AIDS. 2009;23:2497–506. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330ed8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith A, Miles I, Le B, Finlayson T, Oster A, DiNenno E. Prevalence and awareness of HIV infection among men who have sex with men—21 cities, United States, 2008. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1201–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Balan I, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C. Use of a rapid HIV home test prevents HIV exposure in a high risk sample of men who have sex with men. Aids Behav. 2012;16:1753–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0274-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Carballo-Dieguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, Balan I. Will gay and bisexually active men at high risk of infection use over-the-counter rapid HIV tests to screen sexual partners? J Sex Res. 2012;49:379–87. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.647117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katz DA, Golden MR, Stekler JD. Use of a home-use test to diagnose HIV infection in a sex partner: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:440. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Dragavon J, Thomas KK, Brennan CA, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:444–53. doi: 10.1086/600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katz DA, Golden MR, Stekler J. Point-of-sex testing: intentions of men who have sex with men to use home-use HIV tests with sex partners; 2012 National Summit on HIV and Viral Hepatitis Diagnosis, Prevention, and Access to Care; Washington, D.C.. 2012.Nov 26-28, [Google Scholar]

- 72.Leu CS, Ventuneac A, Levin B, Carballo-Dieguez A. Use of a rapid HIV home test to screen sexual partners: a commentary on Ventuneac, Carballo-Dieguez, Leu, et al. 2009. Aids Behav. 2012;16:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9920-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ventuneac A, Carballo-Dieguez A, Leu CS, Levin B, Bauermeister J, Woodman-Maynard E, et al. Use of a rapid HIV home test to screen sexual partners: an evaluation of its possible use and relative risk. Aids Behav. 2009;13:731–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9565-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Centers for Disease Control [Accessed 9 Jul 2013];Serosorting among Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/msmhealth/Serosorting.htm.

- 75.County PH-SK. In: Serosorting among gay and bisexual men. County PH-SK, editor. Am J Publ Health.; Seattle, WA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eaton LA, Cherry C, Cain D, Pope H. A novel approach to prevention for at-risk HIV-negative men who have sex with men: creating a teachable moment to promote informed sexual decision-making. Am J Public Health. 2011;101:539–45. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.191791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]