Abstract

Dysfunctional glial glutamate transporters and over production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (including interleukin-1β, IL-1β) are two prominent mechanisms by which glial cells enhance neuronal activities in the spinal dorsal horn in neuropathic pain conditions. Endogenous molecules regulating production of IL-1β and glial glutamate functions remain poorly understood. In this study, we revealed a dynamic alteration of GSK3β activities and its role in regulating glial glutamate transporter 1 (GLT-1) protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn and nociceptive behaviors following the nerve injury. Specifically, GSK3β was expressed in both neurons and astrocytes in the spinal dorsal horn. GSK3β activities were suppressed on day 3 but increased on day 10 following the nerve injury. In parallel, protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn was enhanced on day 3 but reduced on day 10. In contrast to these time-dependent changes, the activation of astrocytes and over-production of IL-1β were found on both day 3 and day 10. Meanwhile, thermal hyperalgesia was observed from day 2 through day 10 and mechanical allodynia from day 4 through day 10. Pre-emptive pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β activities significantly ameliorated thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia at the late stage but did not have effects at the early stage. These were accompanied with the suppression of GSK3β activities, prevention of decreased GLT-1 protein expression, inhibition of astrocytic activation, and reduction of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn on day 10. These data indicate that the increased GSK3β activity in the spinal dorsal horn is attributable to the downregulation of GLT-1 protein expression in neuropathic rats at the late stage. Further, we also demonstrated that the nerve-injury-induced thermal hyperalgesia on day 10 was transiently suppressed by pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β. Our study suggests that GSK3β may be a potential target for the development of analgesics for chronic neuropathic pain.

Keywords: GSK3β, GSK3beta, IL-1β, interleukin-1beta, glutamate transporter, dorsal horn, pain, nociception

Introduction

Effective treatment of neuropathic pain remains a clinical challenge. Understanding endogenous molecules regulating aberrant neuronal activities along the pain signaling pathway is a critical step towards the development of therapeutics for managing neuropathic pain. Dysfunctional glial glutamate transporters and over production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (including interleukin-1β, IL-1β) are two prominent mechanisms by which glial cells enhance neuronal activities in the spinal dorsal horn (Milligan and Watkins, 2009, Ren and Dubner, 2010).

Glutamate transporters play a crucial role in regulating the activation of glutamate receptors in the spinal dorsal horn. The glutamate released from presynaptic terminals is not metabolized extracellularly. The clearance of presynaptic released glutamate and maintenance of glutamate homeostasis depend on glutamate transporters (Danbolt, 2001). We and others have demonstrated that the downregulation of astrocytic glutamate transporter protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn is associated with neuropathic pain induced by repeated treatments of taxol (Weng et al., 2005, Doyle et al., 2012) or nerve injury (Sung et al., 2003, Nie and Weng, 2010, Nie et al., 2010). Deficient glial glutamate uptake enhances the activation of AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptors, and causes glutamate to spill to the extrasynaptic space and the activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in spinal sensory neurons (Weng et al., 2007, Nie and Weng, 2009; 2010). Despite the critical role of glial glutamate transporters in spinal nociceptive process, the molecular mechanisms regulating protein expression of glial glutamate transporters in the spinal dorsal horn in neuropathic pain remains obscure.

IL-1β is critically involved in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain. Following peripheral nerve injury the activation of glial cells (microglia and astrocytes) in the spinal dorsal horn results in increased production and subsequent release of IL-1β from glial cells (DeLeo et al., 1997, Shamash et al., 2002, Lee et al., 2004). Treatment with antagonists of IL-1β (Sommer et al., 1999, Milligan and Watkins, 2009) or knocking out IL-1β receptors (Wolf et al., 2006, Kleibeuker et al., 2008) reduces behavioral hypersensitivity induced by nerve injury. Expression of IL-1β and the activation of glial cells in the spinal dorsal horn as well as behavioral hyperalgesia in neuropathic rats are attenuated by suppression of astrocytic and microglial activation with a glial inhibitor such as propentofylline or minocycline (Sweitzer et al., 2001, Raghavendra et al., 2003). However, endogenous molecules regulating the activation of glial cells and production of IL-1β remain elusive.

Studies in recent years have shown that glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) is an important endogenous molecule involved in the regulation of glial activation and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the CNS (Jope et al., 2007). GSK3β, a serine/threonine protein kinase, is constitutively active and mainly regulated by phosphorylation at the serine-9 residue by its up-stream kinases (Jope et al., 2007). Differing from most of kinases whose activities are increased upon phosphorylation, GSK3β is inactivated (Woodgett, 1990, Sutherland et al., 1993, Grimes and Jope, 2001) when it is phosphorylated at the serine-9 residue. Activities of GSK3β are increased in many types of neuroinflammation related diseases like Alzheimer’s disease and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Treatment with GSK3β inhibitors ameliorates symptoms in these disease animal models through the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokine production (Sun et al., 2002, De Sarno et al., 2008). The role of GSK3β in pathologic pain conditions has recently been reported. In mice, pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β attenuates nociceptive responses induced by acetic acid or formalin injections (Martins et al., 2011) and decreases morphine tolerance (Parkitna et al., 2006). Inhibition of GSK3β attenuates pre-existing mechanical and cold hyperalgesia induced by pSNL in mice (Martins et al., 2012). The relationship between levels of the endogenous GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn and nociceptive behaviors in rats following nerve injury is unknown. More importantly, molecular signaling pathways regulated by GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn in neuropathic pain conditions remain unexplored.

Our present study demonstrated that following partial sciatic nerve ligation, activities of GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn exhibit a time dependent alteration and inhibition of GSK3β prevents and attenuates the nerve injury-induced thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia at the late stage. Further, glial activation, production of IL-1β and suppressed expression of glial glutamate transporters in the spinal dorsal horn at the late stage (day 10) following nerve injury are at least in part ascribed to increased GSK3β activities.

Material and Methods

Animals

Young adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight range 225g–305g, Harlan) were used. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Georgia and were fully complicate with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals.

Partial sciatic nerve ligation

In this study, we adopted a well-established neuropathic pain animal model induced by partial sciatic nerve ligation. Previous studies have shown that allodynia and hyperalgesia are consistently produced in this model (Seltzer et al., 1990, Cruz Duarte et al., 2012, Dimitrov et al., 2013, Liou et al., 2013). Animals were randomly divided into partial sciatic nerve ligation (pSNL) or sham-operated groups. Briefly, under isoflurane-induced (2–3%) anesthesia, the left sciatic nerve at the upper thigh was exposed and ligated approximately two-thirds the thickness of the sciatic nerve with a 5-0 silk suture as previously described (Seltzer et al., 1990). Following surgery, the wound was closed with skin stables. In sham-operated rats, the left sciatic nerve was exposed and not ligated.

Behavior tests

To determine nociceptive behaviors in rats, the animals were placed on a glass surface at 30°C while loosely restrained under a Plexiglas cage (12 × 20 × 15 cm), and allowed to acclimate for at least 30 minutes. To test the thermal sensitivity in the animals, a radiant heat source was applied from below to the mid-plantar surface of the hind left paw using a light source to evoke a withdrawal response. The latency of paw withdrawal responses, i.e., the time between the stimulus onset and paw withdrawal responses, was recorded (Hargreaves et al., 1988). A cutoff time of 20 seconds was used to avoid damages to the skin. Each hind paw was stimulated 3 times with an interval of at least 2 min and the 3 latencies obtained from each paw were averaged.

To test the mechanical sensitivities, the protocols used previously by others (Tao et al., 2003, Liaw et al., 2005) and us (Cata et al., 2008) were used. Two von Frey monofilaments with bending forces of 1.49 g and 5.96 g were used to generate response-frequency functions for each animal. Each von Frey filament was applied ten times to the mid-plantar side of each hind paw from beneath for about 1 s. The values for each animal were averaged across all animals in each group to yield a group stimulus–response function. The response-frequency [(number of responses/10)×100%] for each von Frey filament was determined. Behavior tests were performed before surgery (day 0, baseline) and then every other day up to day 10 after the surgery.

Drug administration

To determine the effects of pre-emptive treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor on the development of neuropathic pain, the GSK3β inhibitor (AR-014418, 0.3mg/kg) in a volume of 1 ml saline or equal volume of vehicle (saline) was intraperitoneally (i.p) injected into the rats. The intraperitoneal administration was made 1 hr prior to pSNL or sham surgery on day 0, and then daily up to day 9. When behavior tests and the drug administration were made on the same day, behavior tests were completed before the drug administration.

To test the effects of GSK3β inhibitors on pre-existing neuropathic pain, a polyethylene (PE-10) catheter that ended at the spinal L4 segment was intrathecally placed following the technique previously described (Yaksh and Rudy, 1976). Briefly, rats were anesthetized under isoflurane (2–3%) and the atlanto-occipital membrane was exposed by dissection. A PE-10 catheter was carefully advanced through an opening in the atlanto-occipital membrane to the lumbar enlargement. The wound was then closed in layers. The animals were allowed to recover for 7 days before we conducted behavioral tests and then performed pSNL or sham operation. The latencies of paw withdrawal responses collected under such condition were similar to those in rats without the intrathecal catheter (see baseline data in Figs 4 and 8). Ten days after the operation, latencies of paw withdrawal responses were measured prior to and then 15, 30, 60, 90 min and 24 hrs after intrathecal (i.t.) administration of the GSK3β inhibitors (AR-A014418, SB216763), or saline. The GSK3β inhibitors were prepared in saline and injected onto the spinal lumbar enlargement through the pre-implanted catheter in a volume of 10 μl, followed by 20 μl of saline to flush. Vehicle (saline, 10 μl) was also injected in the same fashion in control groups. The experimenter who conducted the behavioral tests was blinded to the treatments given to the rats. Following behavior experiments, rats were i.t. injected with 50 μl of 2% lidocaine. If hindpaw paralysis did not ensue, rats were omitted from the experiment.

Figure 4.

Pre-emptive treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor prevents the development of thermal hyperalgesia at the late stage. Line plots show summaries of the withdrawal latency (mean ± S.E.) to heat stimuli during the 11-day observation period in 4 groups of rats. Baseline (day 0) indicates the baseline measurement before animals received surgery. Comparisons between baseline and at each time point are indicated with + for the pSNL+saline group, ^ for the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group. Comparisons between the pSNL+saline group and the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group are labeled with #. One symbol: p<0.05; Two symbols: p<0.01; Three symbols: p<0.001.

Figure 8.

Pharmacological suppression of GSK3β activities attenuates pre-existing thermal hyperalgesia induced by pSNL. Line plots show summaries of the behavioral data collected at baseline (day 0), 10 days post surgery (10 DPS), and then 15, 30, 60, 90 min and 24 hrs after the intrathecal administration of the tested agents. Baseline (day 0) indicates the baseline measurement before animals received surgery. (A) shows the effects on the withdrawal latency (mean ± S.E.) to heat stimuli induced by a GSK3b inhibitor (SB216763) at two doses (100 nM and 1 μM). Comparisons between data collected on 10 DPS and at each time point are indicated with + for the pSNL+ GSK3β inhibitor (100 nM) group, ^ for the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor (1 μM) group. Comparisons between the pSNL+saline group and the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor (1 μM) group are labeled with #. (B) shows the effects on the withdrawal latency (mean ± S.E.) to heat stimuli induced by another GSK3β inhibitor (AR-A014418) at a dose of 100 ng. Comparisons between data collected on 10 DPS and at each time point are indicated with + for the pSNL+ GSK3β inhibitor group. Comparisons between the pSNL+saline group and the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group are labeled with #. p<0.05; Two symbols: p<0.01.

Immunohistochemical studies

Immunocytochemistry was used to determine the expression of phosphorylated GSK3β and total GSK3β in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia in rats with pSNL or sham operation. On day 10 post pSNL or sham operation, rats were deeply anesthetized with urethane (1.3–1.5g/kg, i.p) and perfused intracardially with 200 ml heparinized phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) pH=7.35 followed by a solution of 4% formaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) pH=7.35. The L4-L5 spinal cord was removed, post-fixed for 24 hours at 4°C in the same fixative, cryoprotected in 15% sucrose in 0.1M PBS for 24 hours at 4°C, and then placed in a 30% sucrose in 0.1M PBS solution at 4°C. Serial transverse sections 30 μm thick were cut on a freezing microtome at −20°C and collected in 0.1M PBS and processed while free floating. The sections were washed three times in 0.1M PBS and then blocked with 10% normal goat serum plus 0.3% Triton X-100 in 0.1M PBS (pH=7.35) for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then incubated for 1 hour at room temperature followed by overnight at 4°C with rabbit anti-GSK3β (1:200, Abcam), rabbit anti-GSK3β phospho S9 (1:100, Abcam), mouse anti-GFAP (a marker for astrocytes, 1:1000, Cell Signalling), and rat anti-OX-42 (a marker for microglia, 1:500, AbD Serotec) antibodies. The sections were washed 3 times in 0.1M PBS and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature with the corresponding Texas Red antibody (1:500 Vector Laboratories), Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:500 Life Technologies), or Mouse Anti-NeuN (a neuronal marker) Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated antibody (1:200 Millipore). After rinsing three times with 0.1M PBS, the sections were mounted onto gelatin-coated slides, air-dried, and cover-slipped with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories). Nonadjacent sections were selected randomly, and the immunostaining for each antibody was recorded on an Olympus BX43 microscope with an Olympus U-CMAD3 camera. Images were processed using Olympus-cellSens Dimensions.

Western Blot experiments

Animals were deeply anesthetized with urethane (1.3–1.5g/kg, i.p.). The L4 to L5 spinal segment was exposed by surgery and removed from the rats. The animals were then euthanized with 5% isoflurane. In order to determine changes of molecular markers in the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to the nerve injury site, the dorsal quadrant of the spinal segment ipsilateral to the nerve injury site or sham operation site was isolated. The isolated tissues were quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for later use. The frozen tissues were homogenized with a hand-held pellet in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% deoxycholic acid, 2 mM orthovanadate, 100 mM NaF, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 20 μM leupeptin, 100 IU ml−1 aprotinin) for 0.5 hr at 37°C. The samples were then centrifuged for 20 min at 12,000 g at 4°C and the supernatants containing proteins were collected. The quantification of protein contents was made by the BCA method. Protein samples (40 μg) were electrophoresed in 8 % SDS polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membranes were blocked with 5% milk and incubated overnight at 4°C with a polyclonal goat anti-IL-1β (1:500, Millipore, Bedford, MA), anti-GLT-1 (1:1000 millipore), anti-GFAP (1:1000 Cell Signaling), anti-phosphorylated Akt (1:500 Cell Signaling), anti-Akt (1:500 Cell Signaling), anti-GSK3β phospho S9 (1:1000 Cell Signaling), and anti-GSK3β (1:1000 Cell Signaling) antibodies, or a monoclonal mouse anti-β-actin (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) primary antibody as a loading control. The blots were then incubated for 1 hr at room temperature (RT) with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), visualized in ECL solution (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) for 1 min, and exposed onto FluorChem HD2 System. The intensity of immunoreactive bands was quantified using ImageJ 1.46 software (NIH). Results were expressed as the ratio of each marker over β-actin control unless otherwise indicated.

Materials

Both AR-A014418 and SB216763 were purchased from Tocris bioscience.

Data Analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± S.E. Student’s t-test used to determine the statistical difference between data obtained from the same group (paired t-test) or between groups (nonpaired t-tests). A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

GSK3β signaling activities in the spinal dorsal horn are suppressed in the early stage but enhanced in the late stage following partial sciatic nerve injury

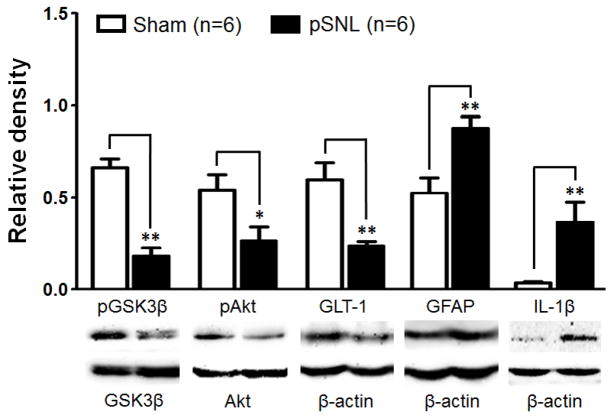

To determine the relationship between GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn and the altered nociceptive behaviors following partial sciatic nerve ligation (pSNL), levels of GSK3β phosphorylated at the serine 9 residue (the inactive form of GSK3β, p-GSK3β) and total GSK3β (t-GSK3β) in the spinal dorsal horn were analyzed in rats 3 and 10 days after pSNL or sham operation. Withdrawal response latencies to radiant heat stimuli in rats with pSNL on day 3 (7.38 ± 0.41, n=6) and 10 (5.45 ± 0.47, n=6) were significantly (p<0.01) shorter than those in sham-operated rats on days 3 (11.56 ± 0.54, n=6) and 10 (12.02 ± 1.12, n=6), indicating a clear sign of thermal hyperalgesia at both time points. Protein levels of t-GSK3β on day 3 (1.24 ± 0.12, n=8) and day 10 (1.07 ± 0.06, n=6) in pSNL rats were similar to those of sham-operated rats on day 3 (1.25X ± 0.18, n=5) and day 10 (1.02 ± 0.07, n=6). Ratios of p-GSK3β protein expression over t-GSK3β protein expression (p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β) in pSNL rats (0.18 ± 0.05, n=6) 10 days after pSNL were significantly (p<0.01) lower than that in sham-operated rats (0.66 ± 0.05, n=6) (Fig. 1), indicating increased activities of GSK3β on day 10 following pSNL. Interestingly, when we analyzed ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β in pSNL rats 3 days after pSNL, we found that the ratio of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β in pSNL rats (0.64 ± 0.07, n=8) were significantly (p<0.01) higher than that in sham-operated rats (0.40 ± 0.07, n=5) (Fig. 2), indicating the pSNL causes a decreased activity of GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn at this time point.

Figure 1.

Ten days after the nerve injury, protein expressions of p-GSK3β, p-AKT, and GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to the injury site are suppressed whereas GFAP and IL-1β are increased. Bar graphs show the mean (+S.E.) ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, and p-AKT/t-AKT, as well as the mean (+S.E.) relative density of GLT-1, GFAP, and IL-1β to β-actin in the spinal dorsal horn of the pSNL and sham-operated rats. Samples of each molecule protein expression in both groups are shown below. * p< 0.05; ** p< 0.01.

Figure 2.

Three days after the nerve injury, protein expressions of p-GSK3β, p-AKT, GLT-1, GFAP, and IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to the injury site are increased. Bar graphs show the mean (+S.E.) ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, and p-AKT/t-AKT, as well as the mean (+S.E.) relative density of GLT-1, GFAP, and IL-1β to β-actin in the spinal dorsal horn of the pSNL and sham-operated rats. Samples of each molecule protein expression in both groups are shown below. * p< 0.05.

Akt (also called protein kinase B) is a major upstream signaling molecule regulating GSK3β activities (Beurel et al., 2010). Increased phosphorylation of Akt (increased Akt activities) causes phosphorylation of GSK3β (suppression of GSK3β activities) at the serine 9 residue while reduced phosphorylation of Akt (reduced Akt activities) decreases levels of phosphorylation of GSK3β (increased GSK3β activities). Thus, we reasoned that phosphorylation levels of Akt should be altered at the same direction and time point as those of GSK3β following pSNL. As expected, we found that ratios of phosphorylated Akt protein (p-Akt) expression over total Akt protein (t-Akt) expression in the spinal dorsal horn on day 10 were significantly (p<0.05) lower in pSNL rats (Fig. 1) compared to those in sham-operated rats. In contrast, ratios of p-Akt/t-Akt in the spinal dorsal horn on day 3 were significantly higher (p<0.05) in pSNL rats than those in sham-operated rats (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, we did not find significant differences in t-Akt expressions between the pSNL group and sham group at either time point (data not shown). These data substantiates the time-dependent alteration of GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn following pSNL. Together, these data indicate that following nerve injury GSK3β signaling activities in the spinal dorsal horn are suppressed at the early stage (day 3) but enhanced at the late stage (day 10) even though thermal hyperalgesia is apparent at both early and late stages.

GSK3β is expressed in dorsal horn astrocytes and neurons

Cellular location of GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn has not been reported. To address this issue, immunohistologic experiments were performed from pSNL and sham-operated rats 10 days post operation. Withdrawal response latencies (7.55 ± 0.57 s, n=6) in pSNL rats on day 10 were shorter than those (13.66 ± 1.22 s, n=6) in sham-operated rats obtained on the same day, indicating pSNL caused thermal hyperalgesia in rats. Astrocytes, microglia, and neurons in spinal slices were respectively labeled with GFAP, OX-42, and NeuN. The slices were doubled-labeled with p-GSK3β or t-GSK3β. We found that in both pSNL rats and sham-operated rats, p-GSK3β staining was colocalized with GFAP staining and NeuN staining. Similarly, t-GSK3β staining was colocalized with GFAP staining and NeuN staining in both pSNL rats and sham-operated rats. Samples of colocalization in pSNL rats are shown in Figure 3A. We did not find colocalizaton between OX42 and p-GSK3β or t-GSK3β in either pSNL (Fig. 3A) or sham-operated rats. These data indicate that p-GSK3β and t-GSK3β are present in astrocytes and neurons in the spinal dorsal horn in both normal and neuropathic rats.

Figure 3.

GSK3β is expressed in astrocytes and neurons but not in microglia in the spinal dorsal horn. A. Samples of double labelings obtained from the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to the pSNL 10 days after the nerve injury. Astrocytes, microglia, and neurons in spinal slices were respectively labeled with GFAP, OX-42, and NeuN antibodies (in green). Total GSK3β (t-GSK3β) and phosphorylated GSK3β (p-GSK3β) are in red. Arrows show colocalization between the red and green stains. Scale bar: 20 μm. B. Samples of t-GSK3β and p-GSK3β stains at the spinal dorsal horn in the pSNL rats and sham-operated rats. Note p-GSK3β stains in the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to the operation site in the neuropathic rats were weaker than in the sham-operated rats. Scale bar: 100 μm.

We also assessed the overall protein expressions of p-GSK3β and t-GSK3β 10 days post the nerve injury. As shown in Figure 3B, immunohistochemical staining of p-GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to the injury site was less than that in the contralateral site. Expressions of t-GSK3β on both sides of the spinal dorsal horn were similar. These data further confirmed that GSK3β activities are enhanced in the spinal dorsal horn ipsilateral to the injury site 10 days after peripheral nerve injury.

GLT-1 expression in the spinal dorsal horn of rats is enhanced at the early stage but decreased at the late stage following partial sciatic nerve injury

Previous studies of astrocyte cultures show that protein expression of GLT-1 is regulated by AKT signaling through transcriptional regulation (Li et al., 2006). Thus, levels of protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn of pSNL rats on days 3 and 10 following nerve injury were analyzed using Western blot. Similar to the time dependent changes of phosphorylated levels of AKT aforementioned, we found that in comparison with sham-operated rats protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn of pSNL rats was increased on days 3 (Fig. 2), but decreased on day 10 (Fig. 1).

Partial sciatic nerve injury induces activation of astrocytes and increased-production of IL-1β on both day 3 and day 10

In contrast to the time-dependent alterations in GLT-1 protein expression, and activities of GSK3β and AKT, we found that expressions of GFAP and IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn on days 3 and 10 following nerve injury were significantly increased in comparison with sham-operated rats.

Pre-emptive treatment with the GSK3β inhibitor prevents the development of thermal hyperalgesia at the late stage

To determine whether the increased GSK3β activities contribute to the development of thermal hyperalgesia following pSNL, rats were randomly assigned into four groups: sham+saline group, sham+GSK3β inhibitor group, pSNL+saline group, and pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group. AR-A014418 was used to inhibit GSK3β activities. AR-A014418 is a thiazole which is an ATP competitive inhibitor of GSK3β (Bhat et al., 2003). Rats of the sham+GSK3β inhibitor group and the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group were treated with AR-A014418 at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg (Martins et al., 2012) (in a volume of 1 ml saline) injected intraperitoneally prior to the surgery and then daily. Saline (1 ml) was also intraperitoneally injected into the rats of the pSNL+saline group and the sham+saline group. As shown in Figure 4, withdrawal response latencies to radiant heat stimuli obtained from the pSNL+saline on days 2 to 10 following the nerve injury were significantly (n=10, p values ranging from 0.05 to 0.001) reduced compared to their baseline prior to the surgery, indicating a clear sign of thermal hyperalgesia. Withdrawal response latencies to radiant heat stimuli in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group at baseline, and on days 2 to 4 were similar to those in the pSNL+saline group, but became significantly longer than those in the pSNL+saline group on day 8 (n=10, p<0.05) and day 10 (n=10, p<0.01). Meanwhile, withdrawal response latencies to radiant heat stimuli in the sham+saline group and sham+GSK3β inhibitor group remained stable during the 10 day observatory period. Together, our results indicate that daily treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor does not prevent the development of the thermal hyperalgesia induced by pSNL at the early stage (days 2 to 4) but attenuates the development of the thermal hyperalgesia at the late stage (days 8 and 10).

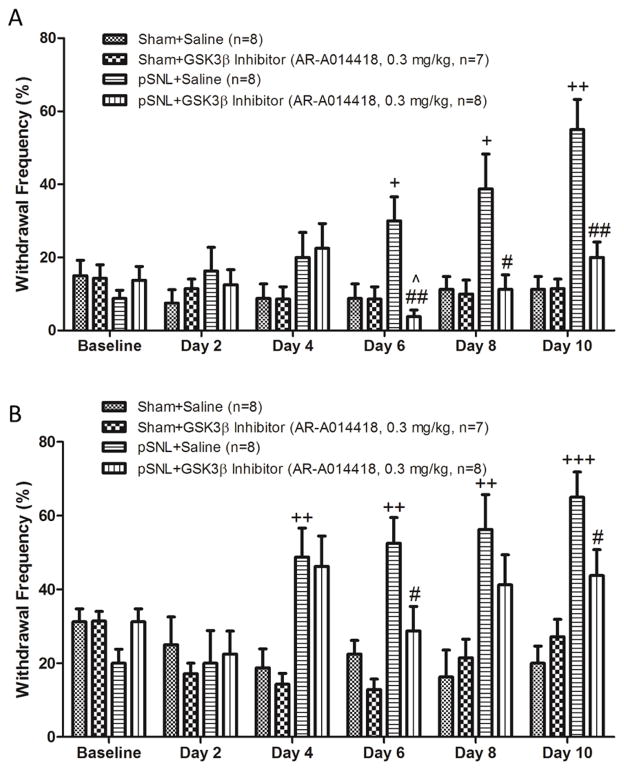

Pre-emptive treatment with the GSK3β inhibitor prevents the development of mechanical allodynia at the late stage

We further determined the effects of GSK3β inhibitors on the development of mechanical allodynia in four groups of rats: sham+saline group, sham+GSK3β inhibitor group, pSNL+saline group, and pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group. These groups of rats received the same treatments as described for the thermal test described above. Changes of mechanical sensitivities in the rats were evaluated with 2 von Frey monofilaments with different bending forces (one at 1.49 g, another at 5.96 g). As shown in Figure 5, prior to the surgery (at baseline) the mean percentage of responses to the von Frey filament with 1.49 g was below 20% and to the von Frey filament with 5.96 g was below 35% in all the 4 groups. Four days after the nerve injury, percentages of withdrawal responses to both von Frey filaments were increased with a significant difference found in the von Frey filament with a bending force of 5.96 g, indicating the development of mechanical allodynia. These increased responses lasted through day 10 after the nerve injury. We found that percentages of withdrawal responses to the 1.49 g von Frey monofilament in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group were significantly reduced in comparison with those in the pSNL+saline group on days 6 to 10 (Fig. 5A). Similarly, percentages of withdrawal responses to the 5.96 g von Frey monofilament in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group were lower in comparison with those in the pSNL+saline group during the same period with a significant difference on days 6 and 10 (Fig. 5B). However, response frequencies to both the filaments on day 4 between the pSNL+saline group and the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group were similar, indicating that GSK3β inhibitors have no significant effects on mechanical allodynia at this time point. The lack of effects of GSK3β inhibitors on mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia during the early stage are in line with our Western blot data showing that GSK3β activities are suppressed on day 3. Meanwhile, the analgesic effects induced by the GSK3β inhibitor at the late stage are consistent with the increased GSK3β activities on day 10 found from the Western blot experiments (Fig. 1).

Figure 5.

Pre-emptive treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor prevents the development of mechanical allodynia at the late stage. Bar graphs show the mean (+S.E.) withdrawal response frequencies to a von Frey filament with a bending force of 1.49 g (A) and to another with a bending force of 5.96 g (B) in 4 groups of rats during 11 day observation period. Baseline (day 0) indicates the baseline measurement before animals received surgery. Comparisons between baseline and at each time point are indicated with + for the pSNL+saline group, ^ for the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group. Comparisons between the pSNL+saline group and the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group are labeled with #. One symbol: p<0.05; Two symbols: p<0.01; Three symbols: p<0.001.

Pre-emptive treatment with the GSK3β inhibitor prevents increased GSK3β activities and the suppressed GLT-1 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn of rats with pSNL 10 days after the nerve injury

To understand the spinal molecular mechanisms underlying the changes of nociceptive behaviors in the above experiments, the rats from the above four groups that completed the behavioral tests above were further used for Western blot experiments. We found that ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β expressions in in the spinal dorsal horn in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group (0.43 ± 0.07, n=5) were significantly (p<0.01) higher than those in the pSNL+saline group (0.15 ± 0.03, n=5) (Fig. 6). In contrast, ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β expressions in the sham+GSK3β inhibitor group (0.58 ± 0.08, n=5) were similar to those in the sham+saline group (0.59 ± 0.04, n=5). Ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β expressions in the spinal dorsal horn in the pSNL+saline group (0.15 ± 0.03, n=5) were significantly lower than those in the sham+saline group (0.59 ± 0.04, n=5). We also found that the p-Akt/t-Akt expression ratio in the pSNL+inhibitor group was higher than those in the pSNL+saline group (Fig. 6). No significant differences in the p-Akt/t-Akt expression ratio were found between the sham+GSK3β inhibitor group and sham+saline group (Fig. 6). The p-Akt/t-Akt expression ratio in the pSNL+saline group was significantly lower than that in the sham-saline group (Fig. 6). In contrast to p-GSK3β and p-Akt expression levels, t-GSK3β and t-Akt expression did not vary across all four groups (data not shown). These data indicate that suppression of GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn contributes to the ameliorated nociceptive behaviors observed on day 10 in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group. Further, treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor significantly improved the down-regulation of GLT-1 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn 10 days after the nerve injury (Fig. 6). This indicates that the increased GSK3β activity in the spinal dorsal horn is attributable to the downregulation of GLT-1 protein expression in neuropathic rats at the late stage. We also found that expressions of p-GSK3β, t-GSK3β, p-Akt, t-Akt, and GLT-1 in the sham+GSK3β inhibitor group and the sham+saline group were similar, indicating the GSK3β inhibitor has no effects on the expression of these molecules in normal conditions.

Figure 6.

Pre-emptive treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor for 10 days attenuates the nerve-injury induced increase of GSK3β activities, and ameliorates GLT-1 expression. Bar graphs show the mean (+S.E.) ratios of p-GSK3β/t-GSK3β, and p-AKT/t-AKT, as well as the mean (+S.E.) relative density of GLT-1 to β-actin in the spinal dorsal horn of the sham+saline (Sham), sham+GSK3β inhibitor (Sham-Inhibitor), pSNL+saline (pSNL), and pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor (pSNL-Inhibitor) groups. Samples of each molecule protein expression in each group are shown below. * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01.

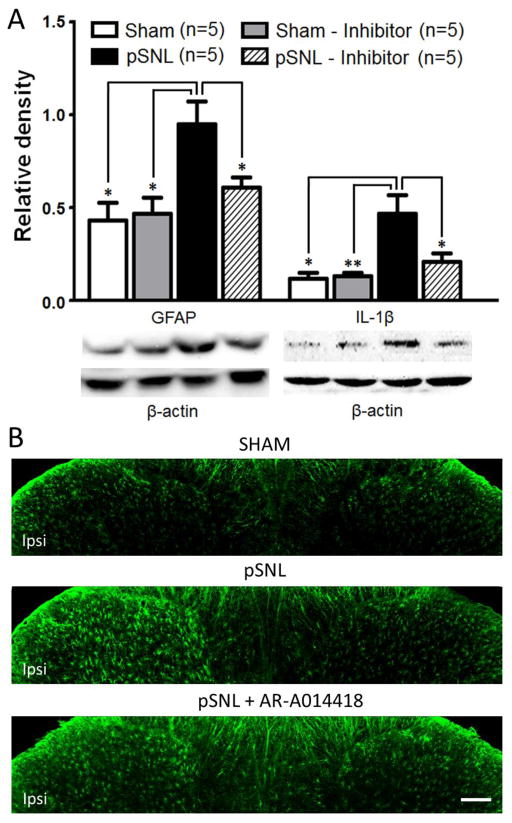

Pre-emptive treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor suppresses activation of astrocytes and over-production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn of rats with pSNL 10 days after the nerve injury

We next investigated protein expression of GFAP and IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn. We found that the increased expression of GFAP induced by the nerve injury was significantly reduced by 10 day treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor as shown in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group in Figure 7A. These were further supported in the immunohistologic experiments. Spinal dorsal horn astrocytes ipsilateral to the nerve injury displayed hypertrophy with thicker processes and soma, a sign of activation of astrocytes. Treatment with the GSK3β inhibitor significantly suppressed the pSNL induced activation of astrocytes (Fig. 7B). At the same time, the over-expression of IL-1β in the dorsal horn induced by pSNL on day 10 following the nerve injury were significantly suppressed by 10 day treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group (Fig. 7A). We also found that expressions of GFAP and IL-11β in the sham+GSK3β inhibitor group and the sham+saline group were similar, indicating the GSK3β inhibitor has no effects on the expression of these molecules in normal conditions. Taken together, these results indicate that suppression of astrocytic activation and production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn all contribute to the inhibitory effect induced by the GSK3β inhibitor on thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia in pSNL rats at the late stage.

Figure 7.

Pre-emptive treatment of the GSK3β inhibitor for 10 days attenuates the nerve-injury induced increase of expressions of GFAP and IL-1β. (A). Bar graphs show the mean (+S.E.) relative density of GFAP and IL-1β to β-actin in the spinal dorsal horn of the sham+saline (Sham), sham+GSK3β inhibitor (Sham-Inhibitor), pSNL+saline (pSNL), and pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor (pSNL-Inhibitor) groups. Samples of each molecule protein expression in each group are shown below. * p< 0.05, ** p< 0.01. (B) Shown are samples GFAP staining for astrocytes in the spinal dorsal horn from the sham+saline (Sham), pSNL+saline (pSNL), and pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor (pSNL-AR-A014418) groups. Note the characteristic hypertrophy with thicker processes and soma in the activated astrocytes on the ipsilateral dorsal horn of saline-pSNL rats. Treatments with the GSK3β inhibitor reduce the pSNL-induced activation of astrocytes. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Pharmacological suppression of GSK3β activities attenuates pre-existing thermal hyperalgesia induced by pSNL

Finally, we determined whether the increased GSK3β activities contribute to the maintenance of thermal hyperalgesia on day 10 following pSNL. Three groups of rats pre-implanted with intrathecal catheters were used: sham+saline group, pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group, and pSNL+saline group. After taking baseline withdrawal response latencies to radiant heat stimuli, we performed either pSNL or sham-operation on rats. Ten days post operation, withdrawal response latencies to radiant heat stimuli in both the pSNL+saline group and the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group were significantly reduced in comparison with their baseline values (Fig. 8A), a sign of thermal hyperalgesia. Meanwhile, withdrawal response latencies to heat stimuli in the sham operated group remained unchanged. We first topically applied SB216763 (a GSK3β inhibitor) onto the spinal lumbar enlargement through a pre-implant intrathecal catheter. SB216763 is a maleimide and has been shown to inhibit GSK3β activity through an ATP competitive manner (Coghlan et al., 2000). Intrathecal injection of SB216763 at 100 nM and 1μM in a volume of 10 μl were respectively made in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group. The pSNL+saline group and the sham+saline group received intrathecal injection of 10 μl saline. As shown in Figure 8A, inhibition of GSK3β ameliorated thermal hyperalgesia in a dose dependent manner. In comparison with their counterparts prior to the administration of SB216763, withdrawal response latencies to heat stimuli in the pSNL rats receiving SB216763 at 100 nM or 1μM were significantly increased within 30 min, which lasted up to 90 minutes, and disappeared within 24 hrs after the drug administration (Fig. 8A). Further, withdrawal response latencies to heat stimuli in the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group were significantly increased at 60 min (p<0.05) and 90 min (p<0.05) in the pSNL rats receiving 1μM SB216763 in comparison with the pSNL+saline group. Withdrawal response latencies to heat stimuli in the pSNL rats receiving 100 nM SB216763 were not significantly different from those in the pSNL+saline group (Fig. 8A).

We next assessed the effects of another GSK3β inhibitor AR-A014418 on the thermal hyperalgesia induced by pSNL 10 days after the nerve injury. Another 3 groups of rats pre-implanted with intrathecal catheters were used: sham+saline group, pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group, and pSNL+saline group. Ten days after pSNL, rats with a clear sign of thermal hyperalgesia received intrathecal injection of either AR-A014418 (concentration: 10 ng/μl, in a volume of 10 μl) for the pSNL+GSK3β inhibitor group or saline (10 μl) for the pSNL+saline group (Fig. 8B). At the same time, the sham+saline group received intrathecal injection of saline (10 μl). Intrathecal administration of AR-A014418 significantly reduced the thermal hypersensitivity induced by pSNL as evidenced by a significant (p<0.01) increase of withdrawal response latencies to heat stimuli from 6.96 ± 0.43 s prior to the intrathecal injection to 11.55 ± 1.14 s at 30 min after the injection. Withdrawal response latencies to heat stimuli in the pSNL rats at 30 min after injection of AR014418 were also significantly (p<0.05) longer than those in the pSNL receiving saline difference at the same time (Fig. 8B). Meanwhile, saline injection into the sham-operated rats or the pSNL rats did not alter their withdrawal response latencies to heat stimuli.

Together, results collected from both GSK3β inhibitors indicate that increased activities of GSK3β in the spinal cord contribute to the maintenance of thermal hyperalgesia induced pSNL on day 10 following the nerve injury.

Discussion

In this study, we for the first time revealed a dynamic alteration of GSK3β activities and its role in regulating GLT-1 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn and nociceptive behaviors following the nerve injury. Specifically, we showed that GSK3β was expressed both in neurons and astrocytes in the spinal dorsal horn. GSK3β activities were suppressed on day 3 but increased on day 10 following the nerve injury. In parallel to this time-dependent alteration, protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn was enhanced on day 3 but reduced on day 10. In contrast to these time-dependent changes, activation of astrocytes and over-production of IL-1β were found on both day 3 and day 10. Meanwhile, thermal hyperalgesia was observed from day 2 through day 10 and mechanical allodynia from day 4 through day 10. We demonstrated that pre-emptive pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β activities ameliorated thermal hyperalgesia on days 8 to 10 and mechanical allodynia on days 6 to 10, but did not have effects on thermal hyperalgesia on days 2 to 4 and mechanical allodynia on day 4. These were accompanied with the suppression of GSK3β activities, prevention of decreased GLT-1 protein expression, inhibition of astrocytic activation and reduction of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn on day 10. Further, we also demonstrated that inhibition of GSK3β on day 10 attenuated the nerve-injury-induced thermal hyperalgesia. These data indicate that suppression of GSK3β activities is a powerful approach to prevent and attenuate chronic neuropathic pain.

Role of GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn in the genesis of pathologic pain

Studies in recent years have shown that activities of GSK3β are involved in the pain signaling system. Pharmacological inhibition of GSK3β activities suppresses second phase formalin nociceptive responses in mice (Martins et al., 2011). Activation of GSK3β in the spinal dorsal horn is ascribed to the regulation of NMDA receptor subunits (NR1 and NR2B) trafficking in the spinal cord in an animal model of post-operative hyperalgesia induced by remifentanil (Yuan et al., 2013). The analgesic effect of morphine in morphine-tolerant rats is restored by intrathecal injection of the GSK3β inhibitor (Parkitna et al., 2006). In neuropathic mice induced by partial sciatic nerve ligation, intraperitoneal injection of GSK3β inhibitors between day 7 to day 11 after the nerve injury transiently attenuates mechanical allodynia induced by the nerve injury (Mazzardo-Martins et al., 2012). Our data for the first time show that pre-emptive treatment of GSK3β inhibitors attenuates the development of thermal hyperalgesia at the late stage (day 8 to day 10), but not at the early stage (days 2 to 4). Similarly, pre-emptive inhibition of GSK3β prevents the development of mechanical allodynia on day 6 to day 10, but not on day 4 after the nerve injury. Currently, relationship between endogenous GSK3β activities and nociceptive behaviors following peripheral nerve injury remains unknown. In this study, we found while thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia were observed both at the early and late stages, GSK3β activities undergo a dynamic alteration following the sciatic nerve injury, being suppressed (increased p-GSK3β expression) on day 3 but increased (decreased p-GSK3β expression) on day 10. In parallel, p-AKT expression was increased on day 3 but reduced on day 10. The AKT/GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathway is well recognized. Increased p-AKT expression (increased AKT activities) leads to increased p-GSK3β (suppression of GSK3β activities). Increased p-GSK3β results in the increased activity of β-catenin (Sugden et al., 2008). The increased p-GSK3β (reduced GSK3β activities) during the acute (day 3) phase found in the present study is indirectly supported by several previous studies. Increased p-AKT in the spinal dorsal horn is observed 1 hr after intraplantar carrageenan injections (Xu et al., 2011). More relevantly, 3 days after L5 spinal nerve ligation, p-AKT expression in the spinal dorsal horn is increased (Xu et al., 2007). In a spared injury-induced neuropathic model, β-catenin has shown to be significantly increased 1 and 3 days following injury in the rat spinal cord (Zhang et al., 2010). Currently, activities of the AKT/GKS3β/β-catenin signaling pathway in the chronic phase of pathologic pain conditions (including neuropathic pain) are unknown. Our study advances this research area by showing that p-AKT and p-GSK3β levels in the spinal dorsal horn are reduced on day 10 following the nerve injury. Further, we demonstrated that increased GSK3β activity in the spinal dorsal horn was a critical mechanism contributing the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain at the late stage.

Role of GLT-1 in spinal nociceptive process and its regulation

Excessive activation of glutamate receptors in the spinal dorsal horn is a culprit causing aberrant neuronal activities in the spinal dorsal horn in neuropathic pain (Ren and Dubner, 2008, Milligan and Watkins, 2009). Activation of glutamate receptors is governed by three essential factors: the amount of synaptically released glutamate, the rate at which glutamate is removed by glutamate transporters, and the properties of postsynaptic glutamate receptors (Clements, 1996, Anderson and Swanson, 2000). Glial glutamate transporters account for over 90% of all CNS synaptic glutamate uptake (Tanaka et al., 1997). It is believed that GLT-1 is a major glial glutamate transporter in the CNS (Tanaka et al., 1997, Danbolt, 2001). Previous studies show that GLT-1 protein expression is increased on day 3 and reduced on days 7 and 14 in the spinal dorsal horn of neuropathic rats induced by chronic constrictive injury of the sciatic nerve (Sung et al., 2003). Our current study confirm this notion by showing increased GLT-1 protein expression on day 3 and decreased protein expression of GLT-1 on day 10 in another neuropathic pain model induced by pSNL, suggesting that a time dependent alteration of GLT-1 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn is a general pathological changes in rats with nerve injury.

We and other have shown that pharmacological inhibition of spinal glial glutamate transporters induces mechanical and thermal allodynia (Liaw et al., 2005, Weng et al., 2006). At the synaptic level, we demonstrate that deficient glial glutamate uptake enhances activation of AMPA and NMDA receptors, and causes glutamate to spill to the extrasynaptic space and the activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in spinal sensory neurons (Weng et al., 2007, Nie and Weng, 2009; 2010). Furthermore, we also show that deficiency of glial glutamate uptake in the spinal dorsal horn results in a decrease in GABAergic synaptic activities due to impairment in GABA synthesis through the glutamate-glutamine cycle (Jiang et al., 2012). Reduced GABA concentrations and suppression of GLT-1 protein expression are found in the spinal dorsal horn of neuropathic rats (Cirillo et al., 2011). Only a handful of studies have investigated mechanisms leading to dysfunction of spinal glial glutamate transporter function in the spinal dorsal horn. Down-regulation of GLT-1 expression and increased glutamate concentrations in the spinal dorsal horn induced by nerve injury are reversed when animals receive seven-day treatments of nerve growth factor (Cirillo et al., 2011, Colangelo et al., 2012). Glutamate transporter activities are decreased by increased arachidonic acid in nerve-injury induced neuropathic rats (Sung et al., 2007). In taxol-induced neuropathic rats, nitration of glial glutamate transporters by peroxynitrite reduces glial glutamate transporter function (Doyle et al., 2012). Previously we also showed that suppression of glial activation with minocycline prevents the downregulation of GLT-1 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn in rats following pSNL. Our current study identifies GSK3β as a novel molecule regulating protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn in neuropathic rats induced by the nerve injury. This notion is in agreement with a previous study in astrocyte cultures showing that increased activities of AKT (an upstream molecule to GSK3β) enhances protein expression of GLT-1 through transcriptional regulation (Li et al., 2006).

Role of IL-1β in spinal nociceptive process and its regulation in neuropathic pain

Activation of glial cells and the subsequent increased production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn are shown in pathological pain animal models induced by nerve injury (DeLeo et al., 1997), peripheral inflammation (Raghavendra et al., 2004) or bone cancer (Zhang et al., 2005). In a rat model of inflammatory pain induced by injecting complete Freund’s adjuvant, IL-1β produced by activated astrocytes increases phosphorylation of NMDA receptors in the spinal dorsal horn (Zhang et al., 2008). Exogenous application of IL-1β onto the spinal slices enhances both the release of glutamate from presynaptic neurons, and functions of AMPA and NMDA receptors in postsynaptic neurons in normal rats (Kawasaki et al., 2008b). Recently, we further demonstrated that endogenous IL-1β in neuropathic rats enhances non-NMDA glutamate receptor activities in postsynaptic neurons, and glutamate release from the primary afferents through coupling with presynaptic NMDA receptors in the spinal dorsal horn (Yan, 2012). Exoggenous application of IL-1β also reduces activities of GABA receptors and glycine receptors in dorsal horn neurons (Kawasaki et al., 2008b). Efforts in recent years have been made towards understanding endogenous molecules controlling glial activation and IL-1β production in pathological pain conditions. IL-1β production is attenuated through suppressing a protease that is required to activate IL-1β through cleavage. Proteases like cathepsin B, caspase-1, and MMP2 are implicated in different pathological pain conditions. Suppression of cathepsin B (Sun et al., 2012), caspase-1 activities (Samad et al., 2001) in the spinal dorsal horn attenuates inflammatory pain induced by CFA through reducing production of IL-1β. In rats with neuropathic pain, production of IL-1β and abnormal nociceptive behaviors are reduced by inhibiting MMP2 activities (Kawasaki et al., 2008a). Modulation of kinases is another important mechanism regulating production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn under neuropathic pain conditions. For example, p38 MAP kinase in spinal microglia is activated by nerve injury (Kim et al., 2002, Jin et al., 2003, Clark et al., 2007). Inhibition of p38 suppresses IL-1β release (Clark et al., 2006) and synthesis of IL-1β via transcriptional regulation (Ji and Suter, 2007), as well as diminish pain hypersensitivity in animals with nerve injury (Jin et al., 2003). GSK3β is an important kinase implicated in glial activation and cytokine production in many CNS diseases. Suppression of GSK3β activities has been shown to improve clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis and reduce glial activation and production of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β (Sun et al., 2002, De Sarno et al., 2008). The effects of GSK3β inhibitors on production of IL-1β in the spinal cord in pathological pain was only reported in one recent study, where daily intraperitoneal injection of a GSK3β inhibitor between days 7 to day 11 reduces production of IL-β induced by partial sciatic nerve ligation in mice. Currently, it remains unknown whether glial activation and the production of IL-1β in the spinal dorsal horn in animals with nerve injury are correlated with alterations of GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn. Our study for the first time demonstrated that pre-emptive treatment with the GSK3β inhibitor is effective in the prevention of activation of astrocytes and over-production of IL-1β following nerve injury, and such effects are related to the suppression of GSK3β activities in the spinal dorsal horn.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that increased GSK3β activities are implicated in the development of thermal hyperalgesia and mechanical allodynia at the late stage but not at the early stage. Increased GSK3β activities are related to activation of astrocytes and overproduction of IL-1β, as well as suppression of GLT-1 protein expression of GLT-1 in the spinal dorsal horn at the late stage. Hence, GSK3β is a potential target for the development of analgesics to treat neuropathic pain at the chronic stage but not for the acute stage.

Highlights.

The role of spinal GSK3β in the genesis of neuropathic pain is determined.

Partial sciatic nerve ligation induces a dynamic alteration of spinal GSK3β activities.

The increased GSK3β activity causes downregulation of GLT-1 protein expression.

The increased GSK3β activity causes over-production of interleukin-1β.

GSK3β may be a potential target for the development of analgesics for chronic neuropathic pain.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the NIH RO1 grant (NS064289) to H.R.W.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson CM, Swanson RA. Astrocyte glutamate transport: review of properties, regulation, and physiological functions. Glia. 2000;32:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beurel E, Michalek SM, Jope RS. Innate and adaptive immune responses regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) Trends Immunol. 2010;31:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat R, Xue Y, Berg S, Hellberg S, Ormö M, Nilsson Y, Radesäter AC, Jerning E, Markgren PO, Borgegård T, Nylöf M, Giménez-Cassina A, Hernández F, Lucas JJ, Díaz-Nido J, Avila J. Structural Insights and Biological Effects of Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3-specific Inhibitor AR-A014418. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:45937–45945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cata JP, Weng HR, Dougherty PM. The effects of thalidomide and minocycline on taxol-induced hyperalgesia in rats. Brain Res. 2008;1229:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo G, Bianco MR, Colangelo AM, Cavaliere C, Daniele de L, Zaccaro L, Alberghina L, Papa M. Reactive astrocytosis-induced perturbation of synaptic homeostasis is restored by nerve growth factor. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41:630–639. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AK, D’Aquisto F, Gentry C, Marchand F, McMahon SB, Malcangio M. Rapid co-release of interleukin 1beta and caspase 1 in spinal cord inflammation. J Neurochem. 2006;99:868–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark AK, Yip PK, Grist J, Gentry C, Staniland AA, Marchand F, Dehvari M, Wotherspoon G, Winter J, Ullah J, Bevan S, Malcangio M. Inhibition of spinal microglial cathepsin S for the reversal of neuropathic pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:10655–10660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610811104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements JD. Transmitter timecourse in the synaptic cleft: its role in central synaptic function. Trends in Neuroscience. 1996;19:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghlan MP, Culbert AA, Cross DAE, Corcoran SL, Yates JW, Pearce NJ, Rausch OL, Murphy GJ, Carter PS, Roxbee Cox L, Mills D, Brown MJ, Haigh D, Ward RW, Smith DG, Murray KJ, Reith AD, Holder JC. Selective small molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 modulate glycogen metabolism and gene transcription. Chemistry & Biology. 2000;7:793–803. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colangelo AM, Cirillo G, Lavitrano ML, Alberghina L, Papa M. Targeting reactive astrogliosis by novel biotechnological strategies. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz Duarte P, St-Jacques B, Ma W. Prostaglandin E2 contributes to the synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in primary sensory neuron in ganglion explant cultures and in a neuropathic pain model. Experimental neurology. 2012;234:466–481. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:1–105. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarno P, Axtell RC, Raman C, Roth KA, Alessi DR, Jope RS. Lithium prevents and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;181:338–345. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLeo JA, Colburn RW, Rickman AJ. Cytokine and growth factor immunohistochemical spinal profiles in two animal models of mononeuropathy. Brain Research. 1997;759:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov EL, Kuo J, Kohno K, Usdin TB. Neuropathic and inflammatory pain are modulated by tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:13156–13161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1306342110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle T, Chen Z, Muscoli C, Bryant L, Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S, Dagostino C, Ryerse J, Rausaria S, Kamadulski A, Neumann WL, Salvemini D. Targeting the overproduction of peroxynitrite for the prevention and reversal of paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:6149–6160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6343-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3β in cellular signaling. Progress in Neurobiology. 2001;65:391–426. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain. 1988;32:77–88. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji RR, Suter MR. p38 MAPK, microglial signaling, and neuropathic pain. Molecular pain. 2007;3:33. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang E, Yan X, Weng HR. Glial glutamate transporter and glutamine synthetase regulate GABAergic synaptic strength in the spinal dorsal horn. J Neurochem. 2012;121:526–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07694.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin SX, Zhuang ZY, Woolf CJ, Ji RR. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is activated after a spinal nerve ligation in spinal cord microglia and dorsal root ganglion neurons and contributes to the generation of neuropathic pain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:4017–4022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04017.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jope RS, Yuskaitis CJ, Beurel E. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): inflammation, diseases, and therapeutics. Neurochem Res. 2007;32:577–595. doi: 10.1007/s11064-006-9128-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Xu ZZ, Wang X, Park JY, Zhuang ZY, Tan PH, Gao YJ, Roy K, Corfas G, Lo EH, Ji RR. Distinct roles of matrix metalloproteases in the early- and late-phase development of neuropathic pain. Nat Med. 2008a;14:331–336. doi: 10.1038/nm1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki Y, Zhang L, Cheng JK, Ji RR. Cytokine mechanisms of central sensitization: distinct and overlapping role of interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in regulating synaptic and neuronal activity in the superficial spinal cord. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008b;28:5189–5194. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3338-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Bae JC, Kim JY, Lee HL, Lee KM, Kim DS, Cho HJ. Activation of p38 MAP kinase in the rat dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord following peripheral inflammation and nerve injury. Neuroreport. 2002;13:2483–2486. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200212200-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleibeuker W, Gabay E, Kavelaars A, Zijlstra J, Wolf G, Ziv N, Yirmiya R, Shavit Y, Tal M, Heijnen CJ. IL-1 beta signaling is required for mechanical allodynia induced by nerve injury and for the ensuing reduction in spinal cord neuronal GRK2. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HL, Lee KM, Son SJ, Hwang SH, Cho HJ. Temporal expression of cytokines and their receptors mRNAs in a neuropathic pain model. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2807–2811. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LB, Toan SV, Zelenaia O, Watson DJ, Wolfe JH, Rothstein JD, Robinson MB. Regulation of astrocytic glutamate transporter expression by Akt: evidence for a selective transcriptional effect on the GLT-1/EAAT2 subtype. J Neurochem. 2006;97:759–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw WJ, Stephens RL, Jr, Binns BC, Chu Y, Sepkuty JP, Johns RA, Rothstein JD, Tao YX. Spinal glutamate uptake is critical for maintaining normal sensory transmission in rat spinal cord. Pain. 2005;115:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou JT, Lee CM, Lin YC, Chen CY, Liao CC, Lee HC, Day YJ. P-selectin is required for neutrophils and macrophage infiltration into injured site and contributes to generation of behavioral hypersensitivity following peripheral nerve injury in mice. Pain. 2013;154:2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins DF, Rosa AO, Gadotti VM, Mazzardo-Martins L, Nascimento FP, Egea J, Lopez MG, Santos AR. The antinociceptive effects of AR-A014418, a selective inhibitor of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta, in mice. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2011;12:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins LM, Martins DF, Stramosk J, Cidral-Filho FJ, Santos ARS. Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3-Specific Inhibitor AR-A014418 Decreases Neuropathic Pain in Mice: Evidence for The Mechanisms of Action. Neuroscience. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzardo-Martins L, Martins DF, Stramosk J, Cidral-Filho FJ, Santos AR. Glycogen synthase kinase 3-specific inhibitor AR-A014418 decreases neuropathic pain in mice: evidence for the mechanisms of action. Neuroscience. 2012;226:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan ED, Watkins LR. Pathological and protective roles of glia in chronic pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:23–36. doi: 10.1038/nrn2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie H, Weng HR. Glutamate transporters prevent excessive activation of NMDA receptors and extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the spinal dorsal horn. Journal of neurophysiology. 2009;101:2041–2051. doi: 10.1152/jn.91138.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie H, Weng HR. Impaired glial glutamate uptake induces extrasynaptic glutamate spillover in the spinal sensory synapses of neuropathic rats. Journal of neurophysiology. 2010;103:2570–2580. doi: 10.1152/jn.00013.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie H, Zhang H, Weng HR. Minocycline prevents impaired glial glutamate uptake in the spinal sensory synapses of neuropathic rats. Neuroscience. 2010;170:901–912. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkitna JR, Obara I, Wawrzczak-Bargiela A, Makuch W, Przewlocka B, Przewlocki R. Effects of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta and cyclin-dependent kinase 5 inhibitors on morphine-induced analgesia and tolerance in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:832–839. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.107581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra V, Tanga F, DeLeo JA. Inhibition of microglial activation attenuates the development but not existing hypersensitivity in a rat model of neuropathy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:624–630. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavendra V, Tanga FY, DeLeo JA. Complete Freund adjuvnat-induced peripheral inflammation evokes glial activation and proinflammatory cytokine expression in the CNS. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;20:467–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren K, Dubner R. Neuron-glia crosstalk gets serious: role in pain hypersensitivity. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008;21:570–579. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32830edbdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren K, Dubner R. Interactions between the immune and nervous systems in pain. Nat Med. 2010;16:1267–1276. doi: 10.1038/nm.2234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samad TA, Moore KA, Sapirstein A, Billet S, Allchorne A, Poole S, Bonventre J, Woolf CJ. Interleukin-1á-mediated induction of Cox-2 in the CNS contributes to inflammatory pain hypersensitivity. Nature. 2001;410:471–475. doi: 10.1038/35068566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer Ze, Dubner R, Shir Y. A novel behavioral model of neuropathic pain disorders produced in rats by partial sciatic nerve injury. Pain. 1990;43:205–218. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(90)91074-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamash S, Reichert F, Rotshenker S. The cytokine network of Wallerian degeneration: tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1alpha, and interleukin-1beta. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002;22:3052–3060. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03052.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer C, Petrausch S, Lindenlaub T, Toyka KV. Neutralizing antibodies to interleukin 1-receptor reduce pain associated behavior in mice with experimental neuropathy. Neuroscience Letters. 1999;270:25–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00450-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden PH, Fuller SJ, Weiss SC, Clerk A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) in the heart: a point of integration in hypertrophic signalling and a therapeutic target? A critical analysis. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(Suppl 1):S137–153. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Wu Z, Hayashi Y, Peters C, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Nakanishi H. Microglial cathepsin B contributes to the initiation of peripheral inflammation-induced chronic pain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:11330–11342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0677-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Sato S, Murayama O, Murayama M, Park JM, Yamaguchi H, Takashima A. Lithium inhibits amyloid secretion in COS7 cells transfected with amyloid precursor protein C100. Neuroscience letters. 2002;321:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung B, Lim G, Mao J. Altered expression and uptake activity of spinal glutamate transporters after nerve injury contribute to the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain in rats. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23:2899–2910. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02899.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung B, Wang S, Zhou B, Lim G, Yang L, Zeng Q, Lim JA, Wang JD, Kang JX, Mao J. Altered spinal arachidonic acid turnover after peripheral nerve injury regulates regional glutamate concentration and neuropathic pain behaviors in rats. Pain. 2007;131:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland C, Leighton IA, Cohen P. Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta by phosphorylation: new kinase connections in insulin and growth-factor signalling. The Biochemical Journal. 1993;296 (Pt 1):15–19. doi: 10.1042/bj2960015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweitzer SM, Schubert P, DeLeo JA. Propentofylline, a glial modulating agent, exhibits antiallodynic properties in a rat model of neuropathic pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:1210–1217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Watase K, Manabe T, Yamada K, Watanabe M, Takahashi K, Iwama H, Nishikawa T, Ichihara N, Kikuchi T, Okuyama S, Kawashima N, Hori S, Takimoto M, Wada K. Epilepsy and exacerbation of brain injury in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLT-1. Science. 1997;276:1699–1702. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao F, Tao YX, Mao P, Johns RA. Role of postsynaptic density protein-95 in the maintenance of peripheral nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain in rats. Neuroscience. 2003;117:731–739. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Aravindan N, Cata JP, Chen JH, Shaw AD, Dougherty PM. Spinal glial glutamate transporters downregulate in rats with taxol-induced hyperalgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2005;386:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Chen JH, Cata JP. Inhibition of glutamate uptake in the spinal cord induces hyperalgesia and increased responses of spinal dorsal horn neurons to peripheral afferent stimulation. Neuroscience. 2006;138:1351–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng HR, Chen JH, Pan ZZ, Nie H. Glial glutamate transporter 1 regulates the spatial and temporal coding of glutamatergic synaptic transmission in spinal lamina II neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;149:898–907. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.07.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G, Gabay E, Tal M, Yirmiya R, Shavit Y. Genetic impairment of interleukin-1 signaling attenuates neuropathic pain, autotomy, and spontaneous ectopic neuronal activity, following nerve injury in mice. Pain. 2006;120:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgett JR. Molecular cloning and expression of glycogen synthase kinase-3/Factor A. EMBO Journal. 1990;9:2431–2438. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JT, Tu HY, Xin WJ, Liu XG, Zhang GH, Zhai CH. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase B/Akt in dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord contributes to the neuropathic pain induced by spinal nerve ligation in rats. Experimental neurology. 2007;206:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Fitzsimmons B, Steinauer J, O’Neill A, Newton AC, Hua XY, Yaksh TL. Spinal Phosphinositide 3-Kinase–Akt–Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Signaling Cascades in Inflammation-Induced Hyperalgesia. The Journal of neuroscience. 2011;31:2113–2124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2139-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Rudy TA. Analgesia mediated by a direct spinal action of narcotics. Science. 1976;192:1357–1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1273597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan X, Weng HR. 2012 Neuroscience Meeting Planner (Online) Vol. 2012. New Orleans, LA: Society for Neuroscience; 2012. Presynaptic NMDA receptors are used by interleukin-1β to enhance glutamate release from primary afferent terminals in the spinal dorsal horn. Program No. 180.10/II8. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y, Wang JY, Yuan F, Xie KL, Yu YH, Wang GL. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta contributes to remifentanil-induced postoperative hyperalgesia via regulating N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor trafficking. Anesth Analg. 2013;116:473–481. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318274e3f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RX, Li A, Liu B, Wang L, Ren K, Zhang H, Berman BM, Lao L. IL-1ra alleviates inflammatory hyperalgesia through preventing phosphorylation of NMDA receptor NR-1 subunit in rats. Pain. 2008;135:232–239. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang RX, Liu B, Wang L, Ren K, Qiao JT, Berman BM, Lao L. Spinal glial activation in a new rat model of bone cancer pain produced by prostate cancer cell inoculation of the tibia. Pain. 2005;118:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Chen G, Xue Q, Yu B. Early Changes of β-Catenins and Menins in Spinal Cord Dorsal Horn after Peripheral Nerve Injury. Cellular and molecular neurobiology. 2010;30:885–890. doi: 10.1007/s10571-010-9517-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]