Abstract

Purpose

Despite hypothesized relationships between lack of partner support during a woman’s pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes, few studies have examined partner support among teens. We examined a potential proxy measure of partner support and its impact on adverse birth outcomes (low birth weight (LBW), preterm birth (PTB) and pregnancy loss) among women who have had a teenage pregnancy in the United States.

Methods

In a secondary data analysis utilizing cross-sectional data from 5609 women who experienced a teen pregnancy from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), we examined an alternative measure of partner support and its impact on adverse birth outcomes. Bivariate and multivariable logistic regression were used to assess differences in women who were teens at time of conception who had partner support during their pregnancy and those who did not, and their birth outcomes.

Results

Even after controlling for potential confounding factors, women with a supportive partner were 63% less likely to experience LBW [aOR: 0.37, 95% CI: (0.26 - 0.54)] and nearly two times less likely to have pregnancy loss [aOR: 0.48, 95% CI: (0.32-0.72)] compared to those with no partner support.

Conclusions

Having partner support or involvement during a teenager’s pregnancy may reduce the likelihood of having a poor birth outcome.

Keywords: teenager, birth weight, health survey, partner, pregnancy outcome

Introduction

In 2010, the rate of pregnancy in the US was 34.3 per 1,000 women in the 15-19 year age group.1 Although the rate has decreased 9% since 2009, it is still higher when compared to other Western industrialized nations.1,2 Despite the decrease in overall rate, racial disparities in teen pregnancy rates and complications persist.3 Teen pregnancies not only account for over $10 billion of US healthcare costs, but they are also linked to a wide variety of consequences for the mother including incarceration, failure to complete high school and poor birth outcomes.1,4 Studies have shown that teenage pregnancies are associated with an increase in pregnancy complications such as premature labor, low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction, and perinatal mortality.5-8 Birth weight is an important determinant of infant health and survival. Infants born with low birth weight (<2500 grams) are a major contributor to rates of infant mortality and are also at increased risk for both immediate health problems and long-term health problems.9,10 In 2007, the average medical costs for a healthy baby for the first year of life were $4,551.11 For a preterm baby, the average costs were $33,20012. Decreasing the numbers of preterm births would decrease the number of low birth weight babies and in turn, reduce infant mortality.13

During the course of a woman’s pregnancy, social support is essential to both her health and well-being.14 Stress, including anxiety and depression, is a key risk factor in the etiology of poor birth outcomes such as preterm birth and low birth weight.15 ENREF 15 Lack of social support or perceived social support during pregnancy has been associated with increased stress and anxiety.16,17 Limited improvement in birth outcomes in response to current interventions, including stress reduction 18,19, indicates that our understanding of both the biological impact of stress on the mother and its relation to birth outcomes is inadequate. Paternal involvement has been examined in relation to birth outcomes20-23, particularly as a moderator of the stress-poor birth outcome axis.15

_ENREF_13_ENREF_14Paternal support may moderate or alleviate the stress on pregnant women which in turn may decrease a woman’s chance of having a poor birth outcome.24 Paternal age, education, occupation, physical characteristics, and socio-economic status have all been examined in relation to their partner having adverse birth outcomes,20,25-27 however, findings have often been inconsistent.

Paternal, or partner, support during pregnancy has been difficult to define and to quantify. Some studies have defined paternal involvement from a social standpoint, examining his feelings towards or affection for the partner, 24 criticism of the partner, 24 willingness to offer financial support or talking about feelings, and reliability in child care.24,28 Others have looked at how the partner’s behavior has changed since finding out about the pregnancy (listening to worries, helping with errands, showing he cared).29 Some have even examined the presence or lack of paternal name on the birth certificate as indicative of support,20,30_ENREF_22 while others have studied paternal wantedness of pregnancy, father’s attitudes and behaviors during pregnancy and father’s substance abuse (smoking and alcohol intake) as indicators of level of involvement by the father.31,32 Feldman et al. looked at a baby’s father support scale, which asked if the father would provide financial assistance if it was needed, would be there if he was needed, and if he would provide help when the baby comes. Findings showed that married women reported a significantly greater support from the baby’s father than women who were not married, suggesting that marital status may be indirectly associated with birth weight.33 Stapleton et al. looked at partner support as prenatal support from the baby’s father with a combination of two measures, with a combination of two measures, support effectiveness and pregnancy-specific received support, and its relation to postpartum maternal emotional distress.34

_ENREF_1_ENREF_3_ENREF_5_ENREF_12 Previous research has examined paternal involvement and support on poor pregnancy outcomes among teenagers and women over twenty years of age35, women 20 years of age and above 30, and only among married women (regardless of age).36 Turner and colleagues28 looked at three indices of support: partner, family and friend and their relationship to poor pregnancy outcomes among teenagers in Canada and found a relationship with support and low birth weight. Only one researcher to date has looked exclusively at partner support and birth outcomes among teenage pregnancies in the United States. 20 The purpose of ourstudy was to examine the association between an indicator of partner support and poor birth outcomes—low birth weight, preterm birth, and pregnancy loss—among a national sample of female respondents who were teens at the time of their pregnancy from the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG).

Methods

This secondary study utilized cross-sectional data from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). The NSFG, conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a national household survey from 110 primary sampling units (major areas) using probability sampling methods. Teens, females, Blacks and Hispanics are oversampled to maximize generalizability and to allow a focus on particular groups of public health interest. The NSFG collects information on family life, marriage, pregnancy and preconception related topics as well as men’s and women’s health. Once households are selected, a screen is conducted to see if anyone aged 15-44 is living the in the household, including those residing away from home, and then one member is randomly selected to be interviewed. Respondents ages 18 and older provided informed consent, while those aged 15-17 provided assent after parental consent. The 2006–2010 NSFG utilized a continuous design, allowing for more questions to be added to the survey each year, and contains 22,682 face-to-face quantitative interviews. Interviews were conducted by trained female interviews from Michigan’s Institute for Social Research using computer-assisted personal interviewing with response cards and a list of definitions of terms. Respondents are compensated for their time. 37 The 2006-2010 NSFG sample is representative of the U.S. household population aged 15–44, with 12,279 woman and 10,403 men. The 2006-2010 NSFG response rate was 77%.

Female respondents who are not pregnant or have never been pregnant are asked the respondent questionnaire. Those who are pregnant or have been pregnant are then asked the pregnancy questionnaire. Data from the female respondent and female pregnancy respondent files were combined through the NSFG data use protocol. Participants who were less than 20 years of age at the time of conception for (any of) their pregnancy(ies) were defined as having a teen pregnancy. The sample utilized for analysis was 5609 females who were 10-19 years of age at time of conception and any parity.

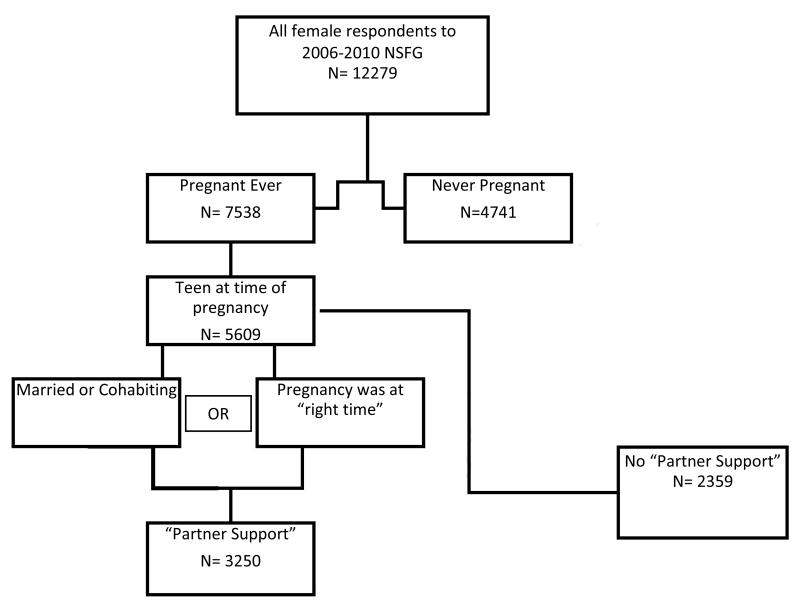

Our primary exposure of interest was alternative or proxy measure of partner support or involvement, referred to throughout the paper as partner support. Although research has examined partner support and other paternal support, we chose partner support as there was no definitive way of knowing whether the father of the baby was the baby’s father or the woman’s partner or both. Women were asked about their partner’s attitude toward the pregnancy of interest. Positive support was measured as the woman reporting that her partner felt that the timing of pregnancy was the “right time” or if the respondent was either married or cohabiting at the time of pregnancy. Lack of support was defined as the woman reporting that her partner felt that the pregnancy was either “later or overdue”,” “too soon, mistimed”, “didn’t care, indifferent”, “unwanted”, or “don’t know, not sure” [See Figure 1]. Primary outcomes of interest included low birth weight (birth weight <2500 grams), preterm birth (respondents <37 weeks gestation), and whether the infant was not alive at time of delivery, pregnancy loss (spontaneous abortion (miscarriage), induced abortions, or stillbirth). The NSFG includes induced abortion among their “pregnancy loss” coding, and we chose to keep that as an indicator of pregnancy loss due to literature supporting lack of partner support and induced abortions.38-41

Figure 1.

Selection of “Partner Support”

A variety of risk factors for the outcome and for the exposure of interest were examined. These included, at time of conception, education (9th or less, 10th grade-12th grade, and more than 12th grade), race (white, black, other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic), income (less than $10,000, less than $15,000, less than $30,000 and $30,000 or higher), and smoking status during pregnancy, if the respondent was living with biological or adoptive parents or no parents at all (proxy for parental support), and first trimester entry into prenatal care.

Statistical Analyses

We used descriptive statistics to examine partner support status, birth outcomes, and respondent characteristics. Bivariate analysis, including Rao-Scott Chi Square tests, and crude and adjusted odds ratios with multivariable logistic regression were utilized to examine the association between partner support status and birth outcomes. All analyses were weighted per National Center for Health Statistics protocol and conducted with SAS version 9.2 using PROC SURVEY procedures. Potential confounders were added into the adjusted models if a significant relationship (p<.0001) was determined between the partner support group and the no partner support group as well as a significant relationship between these factors and our outcomes of interest and a change of ≥ 10% in the crude estimates when these factors were controlled. Effect modification by age, income, race, and ethnicity were examined.

Results

The characteristics of female respondents with a teen pregnancy by partner support (at time of pregnancy) status are presented in Table 1. As expected, a higher prevalence of women who were younger teens (aged 10-13) at time of conception, and had no partner support (.63% to 3.9%, p=.001, respectively). When looking at race, a higher proportion of Black women did not have partner support than those who did (34.4% to 18.0%, p<0.001), in contrast, there was a higher prevalence of partner support among White woman (67.3% to 55.8%, p<0.001, respectively). A higher proportion of Hispanic women who experienced a teen pregnancy had partner support (28.6% to 14.9 %, p<0.001) compared to non-Hispanic women. Women with teen pregnancies who smoked at time of conception had a higher prevalence of partner support (18.1% compared to 13.1%, p<0.001). There were no significant differences in partner support status by income or living situation.

Table 1.

Characteristics by Partner Support

| Partner Support (N=3250) | No Partner Support (N=2359) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted N | Weighted % | Weighted N | Weighted % | P-Value | |

| Age | 0.001* | ||||

| 10 | . | . | 1,588 | 0.0 | |

| 11 | . | . | 29,471 | 0.3 | |

| 12 | 24,677 | 0.2 | 90,620 | 0.9 | |

| 13 | 71,967 | 0.5 | 287,347 | 2.8 | |

| 14 | 392,016 | 2.5 | 640,183 | 6.2 | |

| 15 | 842,568 | 5.4 | 1,287,722 | 12.4 | |

| 16 | 1,767,320 | 11.4 | 1,661,132 | 16.0 | |

| 17 | 2,759,738 | 17.8 | 2,062,159 | 19.8 | |

| 18 | 4,229,991 | 27.3 | 2,188,860 | 21.1 | |

| 19 | 5,383,148 | 34.8 | 2,147,394 | 20.7 | |

| Education | <.001* | ||||

| 9th grade or less | 7,941,290 | 11.4 | 1,201,053 | 10.9 | |

| 10th-12th grade | 23,001,862 | 33.1 | 5,003,398 | 45.3 | |

| More than 12th grade | 38,588,784 | 55.5 | 4,844,663 | 43.8 | |

| Race | <.001* | ||||

| Black | 10,418,085 | 18.0 | 5,804,319 | 34.4 | |

| White | 2,779,246 | 67.3 | 3,585,190 | 55.7 | |

| Other | 2,274,096 | 14.7 | 1,022,620 | 9.8 | |

| Ethnicity | <.001* | ||||

| Hispanic | 4,416,693 | 28.5 | 1,556,068 | 14.9 | |

| Income | 0.014* | ||||

| <$10,000 | 2,896,224 | 18.7 | 2,052,654 | 19.7 | |

| <$15,000 | 3,230,971 | 20.9 | 1,870,726 | 18.0 | |

| <$30,000 | 4,688,777 | 30.3 | 2,784,952 | 26.7 | |

| $30,000+ | 4,655,455 | 30.1 | 3,703,797 | 35.6 | |

| Living with Parents | 0.141 | ||||

| 448,399 | 2.9 | 426,401 | 4.1 | ||

| Smoked during pregnancy | <.001* | ||||

| Yes | 475,452 | 18.1 | 203,033 | 13.1 | |

| Prenatal Care First Trimester | 0.0002* | ||||

| 1,995,054 | 76.0 | 952,461 | 61.6 | ||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SD | P-Value | |

| Age | 17.64 | 0.0 | 16.86 | 0.1 | <.001* |

*Pearson’s Chi Square Test, significant differences at p<.05; data based on missing values

*independent T-test, significant differences at p<.05; data based on missing values

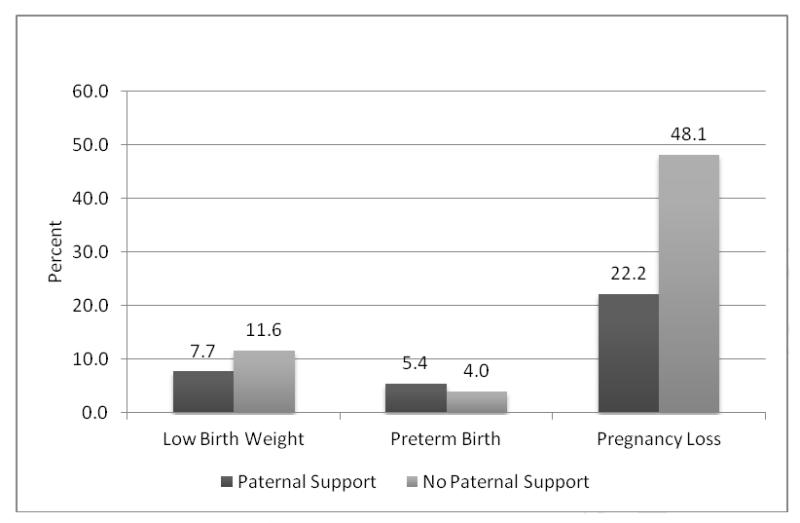

Figure 2 shows the outcomes of interest by partner support status. Surprisingly, those with partner support had a greater number of preterm births than those who had no partner support (5.4 %(n=833511) compared to 4.0%(n=416148), p=.042). However, women with partner support during pregnancy did have a lower prevalence of low birth weight (7.7 %(n=917071) compared to 11.67% (n=614840), p=.002) and lower prevalence of pregnancy loss (22.2%(n=3410264) compared to 48.1% (n=4919731), p<.001).

Figure 2.

Outcomes of Interest by Partner Support

The crude (OR) and adjusted (aOR) odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) quantifying the association between partner support and birth outcomes are presented in Table 2. Crudely, those with partner support were less likely to have a low birth weight baby (OR: 0.64, 95% CI: 0.47 - 0.85) and less likely to have pregnancy loss (OR: 0.31, 95% CI: 0.28 – 0.34). After adjusting for gestational age, age, race, income level, and smoking, pregnant teens with partner support remained significantly less likely to have a low birth weight baby (aOR: 0.37, 95% CI: 0.26-0.54), and after adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, education, income, smoking and prenatal care, they were less likely to have pregnancy loss (aOR: 0.48, 95% CI: 0.32 - 0.72) than those without partner support. Although, not significant, it is important to note that after controlling for important confounders, teens with partner support were also less likely to have a preterm birth than whose without partner support (aOR: 0.65, 95% CI: 0.22 – 1.92) and there appeared to be evidence of qualitative confounding. Qualitative confounding occurs when the direction of the association between outcome and exposure is reversed.

Table 2.

Crude and Adjusted Associations between Paternal Support and Outcomes of Interest

| Outcome | OR | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| Low Birth Weight | 0.64 | (0.47-0.85) |

| Preterm Birth | 1.37 | (1.02 - 1.84) |

| Pregnancy Loss | 0.31 | (0.28 - 0.34) |

| Adjusted Associations | ||

| aOR | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Low Birth Weight1 | 0.37 | (0.26- 0.54) |

| Preterm Birth2 | 0.65 | (0.22- 1.92) |

| Pregnancy Loss3 | 0.48 | (0.32 - 0.72) |

OR, Odds Ratio; aOR, Adjusted Odds Ratio

Accounting for gestational age, race, income and smoking

Accounting for low birth weight, race, and smoking

Accounting for age, race, ethnicity, education, income, smoking and prenatal care

We did not detect any significant interaction between partner support and age, income, race, or ethnicity.

Discussion

In this national sample of women ages 10 to 19 years who experienced pregnancy, we observed that lack of partner support was associated with adverse birth outcomes. Findings corroborate those from previous studies on adultswho had an increased likelihood of low birth weight and infant mortality/pregnancy loss for teen pregnancies with no paternal support. 20,35 Even after adjusting for key confounding factors, pregnancy loss and low birth weight remained lower in the group with higher partner support. Teens with partner support were less likely to have a preterm birth than those without support from the partner, although this difference was not statistically significant.

There are many potential explanations for our findings. Paternal, or partner, support has been shown to have effects on maternal behaviors prenatally and perinatally. Those who have paternal support may experience less stress and be more likely to enter prenatal care.42 They also may be more likely to indicate a desired pregnancy41 which may reduce their risk of poor birth outcomes due to decreased stress and potentially, planning for pregnancy. However, wanting a pregnancy within this age group may also be associated with other lifestyle or sociodemographic characteristics that may not be associated with a healthy birth outcome and perhaps preterm birth in particular. Teenage girls who decide to parent may be more likely to come from impoverished backgrounds, where violence is high, economic opportunities are lacking, and where schooling is not considered important.43,44 These teen moms have also been shown to have greater exposure to physical abuse or neglect45 greater barriers to condom use 46, have low self-esteem, and perceive low family support.47 Pregnancy may be a test of male partner commitment, a desire to be loved, an attempt at creating a traditional family life, or as a way of escaping an unhappy childhood. 48 Nonetheless, findings suggest that even among teens, partner support may be an important factor in a positive birth outcome. Social support can foster self-efficacy in life decision-making, which in turn may increase healthy behaviors in pregnancy and prevent poor birth outcomes.49

Despite important findings, this study is not without limitations. The definition of partner support we used differs from many other studies because of the wide variation in conceptualizing and defining paternal support in the field.20,34 Many teens are not married nor are they cohabiting with their partner, therefore not being married or not cohabiting are not necessarily indicators of lack of partner or paternal support. Also, many teens are not divorced or separated from their partner, which, by our definition of partner support, increased the number of teens in the ‘no partner support group’. Some teens may be unaware of their partner’s wantedness of the pregnancy, especially since 81% of teen pregnancies are unwanted, which also may have affected our exposure.50 Also, a teen’s partner could not have wanted the pregnancy but still could have been supportive. Other study limitations include the use of survey data, which is subject to non-sampling error, social desirability and recall biases. Although this limitation is minimized through survey design, it is still retrospective and women who had a teenage pregnancy may not clearly remember pregnancy experiences or intentions. The NSFG is a cross-sectional survey, which does not permit examination of temporal relationships between support and eventual birth outcome.

Because partner support and involvement has been difficult to define, this study utilized two potential indicators of supportiveness: respondent’s partner’s wantedness of pregnancy, and informal and formal marital status at time of delivery. Pregnancy wantedness and pregnancy intendedness are complex constructs. An unintended pregnancy is one where the pregnancy was unwanted and mistimed. An intended pregnancy is when the baby is desired. A wanted pregnancy includes both intended pregnancies and mistimed pregnancies. 51 A study by D’Angelo and colleagues 52 found 43% of births were unintended. When the unintended was broken down by mistimed and unwanted, it was found that 11% of the births were unwanted. 52 A mistimed pregnancy does not necessarily mean it was unwanted; therefore, these two concepts differ. Pregnancy wantedness and intendedness might not be accurate indicators of actual feelings about having a baby. 51 In addition, those who might have thought it was the “wrong time” to have a baby during pregnancy might eventually be happy with the pregnancy. 51

Unwanted pregnancies are also associated with poor maternal health indicators, such as depression, low self-efficacy, social support and negative paternal support 53, and unintended pregnancies are associated with a variety of poor birth outcomes.3 Future studies may employ a stronger definition of partner support, e.g., using name on the birth certificate and paternal/maternal wantedness combined. Additionally, parent support, sibling support, or participation in social and health programs should also be examined in relation to support during pregnancy. Lastly, the NSFG did not ask about many birth outcomes, or maternal pregnancy complications which could have acted as confounding factors. Data from the NSFG could be combined with other national data sets to assess other adverse birth and pregnancy outcomes and complications, as well as adapting other measures of partner support.

Findings confirm the important role that partners may play in teenage pregnancies and birth outcomes and greater partner involvement in pregnancies among teenage girls should be emphasized. Additionally, these findings could be used to encourage support for programs that foster partner involvement in teen pregnancies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, NIH (1R01ES020447-01 to K.P.T.) and the Frost Foundation (to K.P.T.). There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: None of the authors have a conflict of interest

References

- 1.Hamilton B, Martin J, Ventura S. National Vital Statistics Reports. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Nov 17, 2011. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh S, Darroch J. Adolescent pregnancy and childbearing: levels and trends in developed countries. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000 Jan-Feb;32(1):14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kost K, Henshaw S, L C. U.S. Teenage Pregnancies, Births and Abortions. National and State Trends and Trends by Race and Ethnicity; Guttmacher: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends.pdf>.2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert W, Jandial D, Field N, Bigelow P, Danielsen B. Birth outcomes in teenage pregnancies. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004 Nov;16(5):265–270. doi: 10.1080/14767050400018064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amini SB, Catalano PM, Dierker LJ, Mann LI. Births to teenagers: trends and obstetric outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 1996 May;87(5 Pt 1):668–674. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith GC, Pell JP. Teenage pregnancy and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes associated with first and second births: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2001 Sep 1;323(7311):476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser AM, Brockert JE, Ward RH. Association of young maternal age with adverse reproductive outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1995 Apr 27;332(17):1113–1117. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hediger ML, Scholl TO, Schall JI, Krueger PM. Young maternal age and preterm labor. Ann Epidemiol. 1997 Aug;7(6):400–406. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matthews TJ, MF M. Infant mortality statistics from the 2006 period linked birth/infant death data set. Hyattsville, MD: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dimes Mo. Your premature baby: Low birthweight. 2012 http://www.marchofdimes.com/baby/premature_lowbirthweight.html.

- 11.Reuters T. The Cost of Prematurity and Complicated Deliveries to U.S. Employers. Oct 29, 2008. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medicine Io. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams EK, Nishimura B, Merritt R, C M. Costs of poor birth outcomes among privately insured. Journal of Health Care Finance. 2003;29(3):16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oakley A. Is social support good for the health of mothers and babies? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 1988;6(1) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological Science on Pregnancy: Stress Processes, Biopsychosocial Models, and Emerging Research Issues. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62(1):531–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman S, Hatch MC. Stress, social support and pregnancy outcome: a reassessment based on recent research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1996 Oct;10(4):380–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1996.tb00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rini C, Schetter CD, Hobel CJ, Glynn LM, Sandman CA. Effective social support: Antecedents and consequences of partner support during pregnancy. Pers Relationship. 2006 Jun;13(2):207–229. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodnett E, Fredericks S, Weston J. Support during pregnancy for women at increased risk of low birthweight babies. Cochran Library; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu M, Hogan V, Wright K. Closing the Black-White Gap in Birth Outcomes: A Life-Course Approach Ethnicity and Disease. 2010;20(Supp 2):s2–62. s62–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alio AP, Mbah AK, Grunsten RA, Salihu HM. Teenage pregnancy and the influence of paternal involvement on fetal outcomes. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2011 Dec;24(6):404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bainbridge J. Teenage fathers: risky business for unborn babies. British Journal of Midwifery. 2008;16(3):183–183. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fau JD, Swaminathan S, Alexander G, et al. Significant paternal contribution to the risk of small for gestational age. 20050124 DCOM-20050217 2005(1470-0328 (Print)) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngui E, Cortright A, Blair K. An investigation of paternity status and other factors associated with racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Matern Child Health J. 2009 Jul;13(4):467–478. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0383-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghosh JK, Wilhelm MH, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lombardi CA, Ritz BR. Paternal support and preterm birth, and the moderation of effects of chronic stress: a study in Los Angeles county mothers. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2010 Aug;13(4):327–338. doi: 10.1007/s00737-009-0135-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen XK, Wen SW, Krewski D, Fleming N, Yang QY, Walker MC. Paternal age and adverse birth outcomes: teenager or 40+, who is at risk? Hum Reprod. 2008 Jun;23(6):1290–1296. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumenshine PM, Egerter SA, Libet ML, Braveman PA. Father’s education: an independent marker of risk for preterm birth. Matern Child Health J. 2011 Jan;15(1):60–67. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0559-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah PS. Paternal factors and low birthweight, preterm, and small for gestational age births: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb;202(2):103–123. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turner RJ, Grindstaff CF, Phillips N. Social support and outcome in teenage pregnancy. J Health Soc Behav. 1990 Mar;31(1):43–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins NL, Dunkel-Schetter C, Lobel M, Scrimshaw SC. Social support in pregnancy: psychosocial correlates of birth outcomes and postpartum depression. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1993 Dec;65(6):1243–1258. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.6.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teitler JO. Father involvement, child health and maternal health behavior. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(4-5):403–425. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Misra D, Caldwell C, Young A, Abelson S. Do fathers matter? Paternal contributions to birth outcomes and racial disparities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb;202(2):99–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haug K, Irgens LM, Skjaerven R, Markestad T, Baste V, P S. Maternal smoking and birthweight: effect modification of period, maternal age and paternal smoking. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000 Jun;79(6):485–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feldman PJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD. Maternal social support predicts birth weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000 Sep-Oct;62(5):715–725. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stapleton LR, Schetter CD, Westling E, et al. Perceived partner support in pregnancy predicts lower maternal and infant distress. J Fam Psychol. 2012 Jun;26(3):453–463. doi: 10.1037/a0028332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan H, Wen SW, Walker M, Demissie K. Missing paternal demographics: A novel indicator for identifying high risk population of adverse pregnancy outcomes. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2004 Nov 13;4(1):21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-4-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guadino J, Jenkins B, Rochat R. No fathers’ names: a risk factor for infant mortality in the State of Georgia, USA. Soc Sci Med. 1999 Jan;48(2):253–265. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groves RMMW, Lepkowski J, Kirgis NG. Planning and development of the continuous National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2009;48(1):53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Reasons US women have abortions: Quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2005 Sep;37(3):110–118. doi: 10.1363/psrh.37.110.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ney P, Peeters-ney M, Fung T, Sheils C. How Partner Support of an Adolescent Affects Her Pregnancy Outcome. WebmedCentral PUBLIC HEALTH. 2013;4(2) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Major B, Cozzarelli C, Testa M, Mueller P. Male Partners’ Appraisals of Undesired Pregnancy and Abortion: Implications for Women’s Adjustment to Abortion. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1992;22(8):599–614. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroelinger CD, Oths KS. Partner Support and Pregnancy Wantedness. Birth. 2000;27(2):112–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinez G, Copen C, Abma J. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, 2006-2010. National Survey of Family Growth; Oct, 2011. 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubin V, East PL. Adolescents’ pregnancy intentions: Relations to life situations and caretaking behaviors prenatally and 2 years postpartum. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;24(5):313–320. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00082-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Unger JB, Molina GB, Teran L. Perceived consequences of teenage childbearing among adolescent girls in an urban sample. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;26(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Curry M, Doyle B, Gilhooley J. Abuse among pregnant adolescents: differences by developmental age. Maternal Child Nursing. 1998;23:144–150. doi: 10.1097/00005721-199805000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davies SL, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Harrington KF, Crosby RA, Sionean C. Pregnancy Desire Among Disadvantaged African American Adolescent Females. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2003;27(1):55–62. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herrenkohl EC, Herrenkohl RC, Egolf BP, Russo MJ. The relationship between early maltreatment and teenage parenthood. Journal of Adolescence. 1998;21(3):291–303. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hanna B. Negotiating motherhood: the struggles of teenage mothers. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;34(4):456–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolkow KE, Ferguson HB. Community Factors in the Development of Resiliency: Considerations and Future Directions. 6. Dec 01, 2001. pp. 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Medicine Io. The Best Intentions: Unintended Pregnancy and the Well-Being of Children and Families. 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaufmann RB, Morris L, Spitz AM. Comparison of two question sequences for assessing pregnancy intentions. Am J Epidemiol. 1997 May 1;145(9):810–816. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D’Angelo DV, Gilbert BC, Rochat RW, Santelli JS, Herold JM. Differences Between Mistimed and Unwanted Pregnancies Among Women Who Have Live Births. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(5):192–197. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.192.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maxson P, Miranda ML. Pregnancy intention, demographic differences, and psychosocial health. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2011 Aug;20(8):1215–1223. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2010.2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]