Summary

Membrane lipid regulation of cell function is poorly understood. In early development, sterol efflux and the ganglioside GM1 regulate sperm acrosome exocytosis (AE) and fertilization competence through unknown mechanisms. Here, we show that sterol efflux and focal enrichment of GM1 trigger Ca2+ influx necessary for AE through CaV2.3, whose activity has been highly controversial in sperm. Sperm lacking CaV2.3’s pore-forming α1E subunit showed altered Ca2+ responses, reduced AE, and a strong sub-fertility phenotype. Surprisingly, AE depended on spatio-temporal information encoded by flux through CaV2.3—not merely the presence/ amplitude of Ca2+ waves. Using both studies in sperm and voltage clamp of Xenopus oocytes, we define a molecular mechanism for GM1/CaV2.3 regulatory interaction, requiring GM1’s lipid and sugar components and CaV2.3’s α1E and α2δ subunits. Our results provide mechanistic understanding of membrane lipid regulation of Ca2+ flux and therefore Ca2+-dependent cellular and developmental processes such as exocytosis and fertilization.

Introduction

Determining the mechanisms by which membrane lipids can change cell function is of rapidly growing interest. Here, we study aspects of the initiating event of developmental biology—fertilization—as a model for lipid regulation of cell function. Although it has long been known that lipids govern the sperm’s ability to undergo acrosome exocytosis (AE) and complete the subsequent steps of fertilization, the molecular mechanisms through which this control is exerted have remained unclear for decades.

Lipids are intimately involved in both the positive and negative regulation of sperm fertilization competence. Removal of sterols from the plasma membrane is strictly required for sperm to become able to fertilize, during a process known as “capacitation” (Travis and Kopf, 2002). Conversely, the seminal plasma protein, SVS2, has been shown to bind the ganglioside GM1 in murine sperm, and act as a “decapacitation factor,” keeping the sperm quiescent (Kawano et al., 2008). Co-localization of sterols and GM1 is highly conserved among mammals (Buttke et al., 2006), occurring within dynamic micro-domains segregated to a plasma membrane macro-domain overlying the acrosome (APM), the sperm’s single exocytotic vesicle (Selvaraj et al., 2006, Selvaraj et al., 2009).

In this position, sterols and GM1 could regulate membrane fusion through several potential mechanisms including modulation of Ca2+ flux, which is a known trigger for AE. Interestingly, in several cell types GM1 has been suggested to influence flux through membrane Ca2+ ATPases and exchangers (Ravichandra and Joshi, 1999; Zhao et al., 2004), and voltage-independent gating of CaV1.2 channels (Carlson et. al., 1994, Fang et al., 2002), though no molecular mechanisms have been described.

In an attempt to identify Ca2+ channels involved in regulating sperm function, recent studies have focused on the CatSper channel complex in both human and mouse sperm. CatSper is pH sensitive and weakly voltage dependent (Ren and Xia, 2010); it mediates progesterone (P4)-induced activation of human sperm (Lishko et al., 2011), and its absence in mouse genetic models results in abnormal motility and infertility (Ren and Xia, 2010). Failure to detect other channel activities in electrophysiological recordings has led some to the highly controversial conclusion that CatSper is the only Ca2+ channel in sperm. However, patch-clamp experiments in mouse sperm are typically performed on immature cells that have not completed membrane maturation in either the epididymis or the female tract. Both of these maturational processes involve substantive changes in membrane lipid composition, such as sterol efflux during capacitation. Thus, if sperm Ca2+ flux is in some way modulated by membrane lipids, it would likely avoid detection in those highly constrained experimental systems (additional technical limitations to electrophysiological detection of other channels are described in the discussion). Indeed, it has been suggested that other channels could be present, but are undetectable by existing patching methods (Kirichok and Lishko, 2011). This possibility is supported by the findings of a study in which the sperm head itself was patched, and revealed multiple channel activities that were spatially organized (Jimenez-Gonzalez et al., 2007).

Before the current controversy over whether CatSper is responsible for all Ca2+ flux in sperm, it was believed that the increase in intracellular Ca2+ in the sperm head leading to AE occurs in discrete steps (Florman et al., 2008), where the upstream stimuli include alkalinization and hyperpolarization. CatSper could play this upstream role in this model as it is pH-sensitive and also raises resting Ca2+ concentrations upon sterol efflux (Xia and Ren, 2009). Next, an un-identified voltage-gated Ca2+ channel (VGCC) would mediate focal, transient Ca2+ elevations (Arnoult et al., 1999). Together with the activation of phospholipase Cδ4 (Fukami et al., 2003), these events would trigger a final, sustained elevation in intracellular Ca2+ that in mouse sperm is most likely mediated by TRPC2 channels (Jungnickel et al., 2001). As a result, SNARE-mediated fusion of the APM and the outer acrosomal membrane would occur (Yunes et al., 2000).

Inability to characterize the VGCC has certainly contributed to the controversy surrounding models of Ca2+ flux and initiation of AE. VGCCs are heteromeric complexes comprised of a pore-forming α1 subunit and auxiliary α2δ, β, and γ subunits (Catterall, 2000). Several subtypes of VGCCs have been described in sperm (Darszon et al., 2006), but their in vivo activity has been difficult to characterize. Patch-clamp recordings from developing male germ cells and pharmacological studies suggested the activity of T-type currents (Arnoult et al., 1998). However, mice lacking T-type Ca2+ channels CaV3.1 (Stamboulian et al., 2004) and CaV3.2 (Escoffier et al., 2007) are fertile, and the remaining current in these mice displays characteristics that differ slightly from somatic cell T-type currents (Stamboulian et al., 2004). Additionally, work characterizing depolarization-induced Ca2+ influx to simulate zona pellucida (ZP)-induced Ca2+ rise in mature mouse sperm proved to be insensitive to blockers of L-, P/Q-, and T-type channels (Wennemuth et al., 2000).

One candidate not ruled out by previous studies is VGCC CaV2.3. Despite considerable investigation in multiple cell types, its physiological role remains the least understood of all VGCCs (Weiergraber et al., 2006). These channels introduce large inward Ca2+ currents (Bourinet et al., 1996) and are responsible for the majority of the “residual”, or R-type current (Randall and Tsien, 1995). R-type channels have been defined based on their resistance to inhibitors of other high-voltage activated (L-, N-, and P/Q-type) Ca2+ channels and by their sensitivity to the spider venom peptide SNX-482 (Bourinet et al., 2001). The CaV2.3 VGCC is widely distributed, being found in the central nervous system, endocrine (Pereverzev et al., 2005), cardiovascular (Weiergraber et al., 2005), reproductive (Sakata et al., 2002) and gastrointestinal systems (Grabsch et al., 1999). Several studies have shown their modulation by membrane binding partners, including SNARE proteins (Wiser et al., 2002, Cohen and Atlas, 2004), and confirmed their involvement in exocytosis in various cell types (Wang et al., 1999; Albillos et al., 2000; Vajna et al., 2001). Although involvement of CaV2.3 channels in sperm function has been suggested (Westenbroek and Babcock, 1999; Wennemuth et al., 2000; Sakata et al., 2001, 2002), no conclusive evidence has been provided. Interestingly, sperm from CaV2.3 null mice have been reported to display aberrant motility and to have different responses in Ca2+ uptake in the sperm head, though direct involvement in AE or fertilization apparently was not investigated.

We now describe a mechanism through which membrane lipids can modulate an R-type VGCC. Cell biological, pharmacological, and genetic evidence confirm that focal clustering of the extracellular sugars of GM1, or loss of sterols from the membrane, help stimulate AE through the activation of CaV2.3 channels. Notably, mice lacking the α1E subunit of this channel have marked subfertility in natural matings and severe defects in AE and in vitro fertility. In addition, our comparisons between sperm from CaV2.3 null and wild type mice show the exquisite spatial and temporal control of Ca2+ flux needed to achieve AE. Remarkably, the presence or amplitude of a wave is not sufficient to induce exocytosis, a point of considerable potential importance for the multiple cell types whose functions rely on regulated exocytosis. Lastly, using a reductionist, heterologous expression system and voltage-clamping, we show that GM1’s ability to exert these effects is not restricted to sperm and is mechanistically dependent upon the presence of the α2δ subunit. Together, our data led us to create a molecular model for GM1/lipid regulation of CaV2.3 function in sperm, thereby controlling AE and fertilization.

Results

Focal enrichment of GM1 induces AE in sperm incubated under capacitating conditions

Our prior characterization of the conservation of GM1 segregation to the APM, as well as the temporary binding of SVS2 to GM1 to maintain functional quiescence (Kawano et al., 2008), led us to hypothesize that this lipid plays an important role in fertilization. Upon adding the pentavalent B subunit of cholera toxin (CTB) to live, capacitated sperm, we noted that a sub-population exhibited clearing of labeled CTB signal over the apical acrosome (AA), potentially consistent with AE (Selvaraj et al., 2007). To investigate whether this clearing involved loss of the membrane alone or was also associated with a loss of acrosome matrix as occurs during physiologic AE, we assessed acrosome status with Coomassie staining after treatment with CTB or commonly employed agonists for AE (P4 or solubilized ZP). Addition of Ca2+ ionophore (A23187) provided a positive control, and sperm incubated under capacitating conditions alone gave a baseline for spontaneous AE or loss of acrosome matrix as a result of experimental handling. Exposure to CTB induced AE in sperm incubated in capacitating conditions at levels statistically similar to sperm incubated with P4 or ZP (Figure 1B), and which were significantly higher than seen in the control capacitated sperm.

Figure 1. CTB and GM1 induce acrosome exocytosis (AE).

A) Representative Coomassie staining patterns of sperm having undergone AE (left) or acrosome intact (right). Arrows point to absence or presence of staining of acrosome matrix proteins. B) Box whisker plots of percentage of capacitated (C) wild-type sperm undergoing AE in response to Ca2+ ionophore (A23187), progesterone (P4), solubilized zona pellucida (ZP), or CTB (n=4 trials, ≥100 sperm counted for each condition). Sperm were incubated under capacitating conditions for 50 minutes and treated with P4 (3 µg/ml), ZP (2 ZP/µl), or CTB (1.5 µg/ml) to induce AE for 10 minutes prior to Coomassie assessment. As shown, CTB induced a significant increase in the percent of AE (p<0.0001) that was statistically similar to AE% induced by P4 or ZP. C) Box whisker plots of percentage of capacitated sperm (C) undergoing AE in response to 25µM of exogenous GM1, asialo-GM1 (Asialo), ceramide (Cer), or solvent control (DMSO, data not shown) (n=4). Exogenous GM1 induced a significant increase in AE% (p=0.005) compared to capacitated sperm (C), Asialo, Cer or a solvent control (DMSO, data not shown). D) Box whisker plots of the percentage of sperm undergoing AE in response to CTB in the presence of nickel (Ni). Ni significantly inhibited CTB-induced AE at 30 and 100μM (p=0.02).

To determine whether the observed effect of CTB was due to focal enrichment from CTB’s ability to bind up to 5 molecules of GM1, as opposed to non-specific membrane perturbations, AE was measured following addition of 25µM exogenous GM1. This concentration of GM1 has been shown to stimulate GM1–induced signaling events in somatic cells without affecting overall membrane integrity or cholesterol efflux (Yatomi et al., 1996). As seen with the addition of CTB, exogenous GM1 significantly increased the incidence of AE in capacitated sperm (Figure 1C), but neither GM1 nor CTB affected the viability or AE of non-capacitated sperm (data not shown; n=4).

Glycosphingolipids like GM1 are complex molecules capable of interacting via their sugar and/or lipid components. Our first investigation into the molecular mechanism of GM1’s effects revealed that neither ceramide nor asialo-GM1 (lacking the extracellular sialic acid), were able to induce a significant elevation in AE as compared to GM1 (Figure 1C). Similarly, addition of sialic acid alone did not induce AE (data not shown). These results suggest that GM1 exerted its effects in sperm by means of the extracellular sugars, particularly the sialic acid, but only if specifically oriented by the ceramide tail in the outer leaflet.

To identify whether the effects of GM1 on AE were being mediated by a regulation of Ca2+ flux, we tested the effect of co-incubation with nickel, a non-specific inhibitor of Ca2+ conducting channels. CTB-induced AE was inhibited by nickel in a concentration dependent manner (Figure 1D). Investigating further, we found that extracellular Ca2+ was essential for evoked membrane exocytosis, and that inhibition of Ca2+ influx (including block of SOCC) with either Cd2+ (100µM) or La3+ (10µM) prevented CTB-induced AE (Figure 2A). The effect of 30μM Ni2+ suggested that T- and L-type Ca2+ channels were not involved in GM1-mediated AE. In support of this, nifedipine, which has reported selectivity for L-type channels, failed to inhibit CTB-induced AE even at concentrations up to 100μM. Kurtoxin type KL1, which has been shown to inhibit LVA Ca2+ channels and specifically T-type CaV3.1 and CaV3.2 in sperm (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2003), had no effect, suggesting that T-type channels were not involved. However, in agreement with our Ni2+ and Cd2+ data, blocking CaV2.3 Ca2+ channels with SNX-482 prevented the CTB-induced AE (Figure 2A; it also inhibited GM1-induced AE [data not shown]). Together, these pharmacological data suggested that both CaV2.3 channels and SOCC were necessary for GM1-mediated AE. No further increase in the occurrence of AE was seen with the combination of both P4 and CTB or P4 and GM1, suggesting that these combinations were acting on the same physiologically relevant population of cells (data not shown).

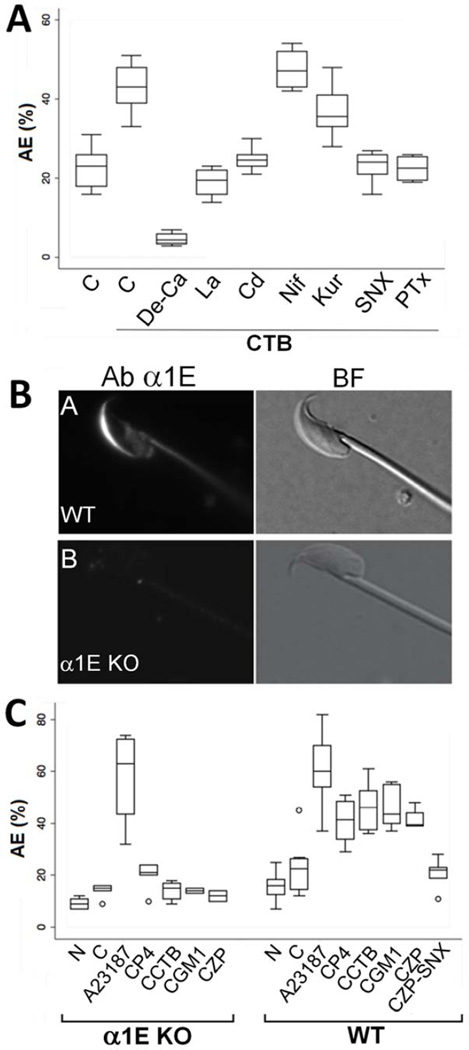

Figure 2. Pharmacologic and genetic data suggesting the importance of α1E in AE.

A) The effect of various pharmacological inhibitors on AE in capacitated sperm (C) in response to CTB. CTB-induced AE required extracellular Ca2+ as shown by the lack of response in Ca2+-depleted media (de-Ca). CTB-induced AE was inhibited by nonspecific Ca2+ influx inhibitors La3+ (La) or Cd2+ (Cd), but not L-type channel inhibitor nifedipine (Nif) or T-type channel inhibitor kurtoxin KL1 (Kur). The CaV2.3 inhibitor SNX-482 (SNX, 500nM) inhibited CTB-induced AE (n=4 trials, p<0.005). B) Indirect immunofluorescence images of wild-type (upper) or an α1E homozygous null mouse sperm labeled with antibodies against the α1E subunit of the CaV2.3. A high magnification view of representative single sperm is shown (n=4 separate experiments with both wild-type and α1E-null sperm, with >100 sperm assessed for each). C) Percentages of AE in α1E null sperm (KO) and wildtype sperm (WT) in response to Ca2+ ionophore A23187, P4, CTB, GM1, and ZP (n=4). See also Figure S1.

Genetic investigation of CaV2.3 involvement in AE

We next took a genetic approach to determine whether CaV2.3 plays a role in AE, to complement the pharmacological data. Sperm from mice lacking the α1E subunit of CaV2.3 have previously been described as having normal intracellular Ca2+ concentrations, but altered Ca2+ dynamics (Sakata et al., 2002). These sperm had a straightened flagellar wave-form and delayed and lower Ca2+ rises in response to mannosylated-BSA, an agent that can induce AE in human sperm (Amin et al., 1996). However, a direct role for this channel in AE or other steps of fertilization has not been described. We therefore utilized a mouse model null for the α1E subunit (Figure S1) to investigate this further.

Consistent with a previous report (Wennemuth et al., 2000), α1E was expressed in the AA of mature sperm, but was absent in sperm from the null mice (Figure 2B). During in vitro assays of AE, sperm from α1E-null mice showed severe defects, failing to undergo AE in response to P4, CTB, GM1, or ZP (Figure 2C). Occurrence of AE in response to Ca2+ ionophore was normal in these sperm, suggesting that membrane fusion machinery was intact and functional in these sperm (Figure 2C). Defects in fertility were also noted in natural matings, with α1E-null mice having significantly smaller litters than age and season-matched wild type mice of the background strain (null: 4 pups ± 2.1 S.D. [n=13] versus WT: 7.1 pups ± 1.6 S.D. [n=11], p=0.001). Matings of null males with wild type females and vice versa demonstrated that the subfertility was solely due to a male factor (null male/WT female: 3.5 pups ± 3.5 S.D. [n=4] versus WT male/null female: 7.25 pups ± 1.7 S.D. [n=8], p=0.00002). Careful investigation using in vitro fertilization (IVF) assays revealed that the presence or absence of the cumulus cells did not significantly impact the relative fertility of the sperm from the null mice (Table 1). Importantly, removal of the ZP from the oocytes resulted in complete rescue of the phenotype (Table 1), providing compelling demonstration that the defect was early in sperm-egg interactions, consistent with a physiologic failure in AE and/or penetration of the ZP.

Table I.

Average success of in vitro fertilization for homozygous and heterozygous matings.

| Oocyte Status | Sperm Genotype |

% Fertilized (n) | SEM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zona intact | Cumulus intact | WT | 69% (134) | 7.3 |

| Cumulus intact | KO | 26% (121) | 9.2 | |

| Zona intact | cumulus free | WT | 65% (106) | 6.4 |

| cumulus free | KO | 19% (104) | 8.4 | |

| Zona free | WT | 68% (91) | 3.3 | |

| KO | 78% (148) | 7.8 | ||

Single cell Ca2+ imaging

Our observation of significant defects in AE in the α1E-null sperm led us to hypothesize that a functional interaction between GM1 and α1E might be involved in Ca2+ mobilization required for membrane fusion and AE. Thus, we sought to investigate the early steps in sperm Ca2+ response to addition of exogenous GM1 or CTB and in response to sterol efflux, a physiological requirement for sperm to become able to fertilize. For these experiments we utilized high speed Ca2+ imaging of single sperm with a controlled delivery system for local administration of GM1, CTB, or 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (2-OHCD). To stimulate Ca2+ mobilization, a short (10 sec) puff of stimulant was applied to individual sperm at 37°C, while recording the changes in Fluo4 fluorescence intensity at image rates of up to 50 frames per second.

Using GM1 or CTB, we observed two major types of spatially and temporally resolved Ca2+ mobilization dynamics in individual sperm. As illustrated in Figure 3A, Ca2+ “transients” typically initiated within seconds after the addition of GM1 or CTB. In some cells, Ca2+ transients were followed by a Ca2+ rise that most often initiated from the connecting piece/midpiece (Ho and Suarez, 2001), and propagated towards the AA; we refer to these sustained elevations as “waves”.

Figure 3. Single cell imaging reveals altered CTB- or GM1-mediated Ca2+ transients in α1E-null sperm.

A) Fluorescence changes as measured in a CD1 sperm loaded with Fluo4-AM, representing the changes in Ca2+ over time in the region of interest (ROI) indicated by the yellow circle on left panel. B) Distribution of Ca2+ transient events over sperm heads (each green dot represents the location of a single transient in a different sperm, compiled here into single images), following CTB addition to CD1 or KO sperm. C) Summary of Ca2+ transient events that occurred in CD1 or α1E KO sperm upon various experimental conditions. D) Statistical analysis of transient lag time, as measured from the beginning of stimulation to the onset of the Ca2+ signal. E) Statistical analysis of integrated Ca2+ influx for the duration of the transient rise phase. Sperm from 3 or more mice were imaged for each experimental condition (n>25 for each condition tested; p value indications are as follows: 0.05<**>0.01, ***<0.005). See also Figure S2.

In terms of transient and wave characteristics, we found no difference between sperm from strain-matched controls and CD1 mice, which are a standard outbred model for sperm cell physiology studies (data not shown). We observed GM1- and CTB-induced Ca2+ transients in ~50% of both α1E-null or control CD1 sperm (Figure 3C). However, in sperm from control mice the Ca2+ transients typically localized along the AA whereas no consistent spatial pattern was observed for transients in the α1E-null sperm, with the majority occurring in the equatorial segment (Figure 3B). Notably, in CD-1 sperm the spatial distribution of Ca2+ transients corresponded precisely with the localization pattern of the α1E subunit as determined by indirect immunofluorescent labeling (Figure 2B). Addition of GM1 in the presence of 10µM La3+ significantly reduced Ca2+ transient occurrence, consistent with an influx of extracellular Ca2+ rather than release from internal stores. Interestingly, upon addition of exogenous GM1 to CD1 sperm incubated under non-capacitating conditions (NON-CAP), we observed high variability in the occurrence of transients. Identification of Ca2+ transients in non-capacitated sperm suggests that signaling processes dependent upon exposure to stimuli for capacitation are not required for activation of the involved Ca2+ channel when GM1 is enriched in the membrane by exogenous addition.

Although Ca2+ transients occurred in equivalently sized populations of both α1E-null sperm and wild type CD1 sperm, there were several dynamic differences in these responses in addition to having different spatial localizations. Transient Ca2+ responses in control sperm initiated 8.9±1.5 seconds following addition of CTB, whereas these transients appeared significantly earlier in response to GM1 (2.2±0.4 seconds; Figure 3D). Comparable differences in transient lag time were observed in the α1E null sperm in response to GM1 or CTB. This difference would be consistent with slower GM1 clustering kinetics that depended upon multivalent binding with CTB versus a more rapid process of GM1 membrane integration.

Strikingly, there was a ~3 fold decrease in total Ca2+ influx in the α1E-null sperm during the transient response upon addition of either GM1 or CTB (Figure 3E). Also of note, mild depolarization of the sperm membrane by addition of high K+ (60mM) failed to stimulate Ca2+ transients (Figure S2A), further suggesting that in sperm, CaV2.3 voltage dependent activation is strongly modulated by its lipid environment.

Although capable of responding to exogenous GM1 (Figure 3C), sperm incubated under non-capacitating conditions demonstrated a reduced Ca2+ influx in response to GM1 similar to that seen in the null sperm (Figure 3E). This observation suggested that an α1E-activating/potentiating process during capacitation is required for increasing open probability and/or conductance. In support of this, puffing 2-OHCD, which stimulates capacitation by mediating sterol efflux, onto non-capacitated sperm resulted in Ca2+ transients with similar characteristics to the addition of GM1 or CTB (Figure S2A and B), suggesting a common mechanism to channel modulation by sterol efflux and focal ganglioside enrichment. Indeed, sterol efflux would be predicted to be the most physiologically relevant means of modulating GM1 dynamics within the plasma membrane. Our observations are consistent with physiological regulation of sperm function through sterol efflux and GM1, and are explored further below.

In most cases, sperm showing the transient increase also demonstrated a secondary Ca2+ mobilization typically propagating from the connecting piece towards the AA as waves, and resulting in a sustained elevation in cytosolic Ca2+ levels (Figure 4A). We observed these Ca2+ waves in over 70% of both the CD1 or α1E-null sperm (Figure 4B). Interestingly, 40% of all control sperm underwent AE following the CTB-mediated Ca2+ wave, whereas only 5% of the α1E null sperm demonstrated subsequent AE (as determined by the loss of fluorescence in the AA, Figure S3 and Movie S1). These results suggest that in response to clustering of GM1 with CTB, cytosolic Ca2+ elevation by itself is required but is not sufficient for induction of AE. In addition, although α1E null mice demonstrated high Ca2+ wave occurrence, they had significantly decreased AE percentage in response to ZP addition (Figure S2A), consistent with a central role for CaV2.3-mediated transients to facilitate AE.

Figure 4. α1E-null sperm have severe defects in ability to undergo AE and altered Ca2+ wave dynamics.

A) Time line analysis of a CD1 sperm loaded with Fluo4-AM, representing the changes in Ca2+ over time as they occur along the line indicated in the left panel. Brighter colors correspond to higher Ca2+ concentrations. In the time line panel, white arrows indicate a Ca2+ transient (left arrow) followed by a Ca2+ wave (right arrow). B) Summary of CTB-induced Ca2+ wave occurrence in CD1 or α1E KO sperm incubated under capacitating conditions (5.5mM glucose and 2mM 2-OHCD), with relative occurrence of AE (cells that demonstrated AE as percentage of cells with Ca2+ waves; yellow area). C) Statistical analysis of wave rise time, calculated from a single exponent fit to individual traces. D) Average Ca2+ elevation at wave peak (relative to baseline Ca2+). E) Integrated Ca2+ influx during the rise phase of Ca2+ waves. Data are presented as AVG±SEM (n>25). Sperm from 3 or more mice were imaged for each experimental condition. p values are 0.05>**>0.01. See also Figure S3 and Movie S1.

Both CD1 and α1E null sperm demonstrated comparable lag time in Ca2+ wave initiation upon CTB addition (89.1±10.2 and 89.9±10.0 sec, respectively). However, the rise time of Ca2+ waves was significantly shorter in the α1E null sperm (502±77 msec) compared to CD1 sperm (842±108 msec; p<0.05 Figure 4C). Although the relative fluorescence increase was slightly but significantly higher in the α1E null sperm (p=0.05, Figure 4D), the waves in these cells diminished faster resulting in a 2-fold decrease in the integrated Ca2+ influx compared to CD1 sperm upon CTB addition (Figure 4E). Finally, we found comparable wave velocities in CD1 and α1E null sperm (5.18±0.56 and 4.5±0.58 µm/sec respectively), consistent with an intact Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release mechanism that supports wave propagation independently of CaV2.3 activation. Together, our data suggest that the spatial and temporal information contained within the transients either influences the resulting wave and/or locally changes the subsequent wave’s ability to facilitate/promote AE. The spatial and temporal relationship between the transient and wave are therefore critical in determining whether the flux will result in AE.

The α2δ1 subunit is involved in GM1-mediated sperm Ca2+ flux

In light of the partitioning of α2δ into membrane rafts (e.g. Robinson et al., 2011), and because both GM1 and α2δ are similar in having highly charged extracellular sugars, we hypothesized that this subunit might play a significant role in channel modulation. First, we confirmed the expression of α2δ1/2/4 in developing male germ cells using RT-PCR (data not shown). Next, we localized α2δ isoforms expressed in sperm, finding both α2δ1 and α2δ4 in the AA (Figure 5A–B), with higher correspondence of α2δ1 with α1E. To verify the specificity of α2δ1 localization, we performed a peptide block of the antibody by pre-adsorbing it with the peptide against which it was generated (Figure S4). The localization patterns of the α2δ subunits were only marginally different in the α1E null sperm (Figure 5B), suggesting coupling to other α1 subunits reported in mouse sperm (Westenbroek and Babcock, 1999). To investigate a possible functional role of α2δ1 in GM1 regulation of sperm Ca2+ flux, we utilized the α2δ1/2-specific inhibitor, gabapentin (GBP, Taylor, 2009). A 20–40 minute exposure to GBP (100µM) induced a significant reduction in Ca2+ transient occurrence and AE (Figure 5C–D), which taken together with our localization results, suggest that α2δ1 subunits are likely involved in regulating Ca2+ transients and demonstrate again the strong functional association between Ca2+ transients and AE.

Figure 5. The α2δ1 subunit is involved in GM1-mediated sperm Ca2+ flux.

A) Representative images of localization of α2δ subunits. B) Quantification of α2δ localization patterns for wild-type (wt) verus α1E null sperm (data collected from 4 wt and 2 α1E null mice with >110 sperm for each). Different regions of the sperm head are abbreviated as indicated in the inset: AA-apical acrosome, PA-post acrosome, ES-equatorial segment, ND-not detected. C) Ca2+ transient occurrence in CD1 sperm stimulated with GM1 (blue bar, n=42 from 3 mice) or with GM1 in the presence of 100µM GBP (white bar, n=32 from 3 mice). D) GM1-induced Ca2+ wave occurrence with or without GBP (100µM), with relative occurrence of AE (cells that demonstrated AE as percentage of cells with Ca2+ waves denoted by yellow shading). E) Six days after cRNA injection with α1E (2 ng/oocyte), β2A (5 ng/oocyte), and/or α2δ (5 ng/oocyte), Xenopus oocytes were two electrode voltage clamped. Ca2+ currents were elicited from a holding potential of –80 mV by voltage steps applied at 5-sec intervals to test potentials between –35 to +45 mV in response to 160 ms pulse duration. G/V curves of α1E and β2A (open circles) or CaV2.3 (closed circles). F) Effect of GM1 on G/V curves (CaV2.3 red-filled circles, α1E + β2A open circles). See also Figure S4.

To investigate the molecular mechanism by which CaV2.3 is modulated by GM1, we utilized the Xenopus oocyte heterologous expression system, injecting various combinations of cRNA of α1E, α2δ1 and β2A into stage V–VI Xenopus oocytes (Note that both β1 and β2 have been reported in the AA (Serrano et al., 1999)). Six days later we utilized the two electrode voltage clamp technique to measure Ca2+ currents elicited by various test potentials. As expected (Qin et al., 1998), co-expression of the α2δ1 and α1E subunits in the oocytes resulted in a moderate reduction in voltage sensitivity (as demonstrated by the right shift of the G/V curve) of the channel conductance (Figure 5E). However, the G/V relationship of CaV2.3 clearly showed a significant left shift in the presence of GM1 (Figure 5F). The substantial left shift in α1E voltage dependence in the presence of α2δ1 strongly suggests that this subunit is required for mediating the activation of the functional channel complex by its lipid environment, specifically by GM1.

Because these experiments were conducted under voltage clamp conditions, the data collected were insensitive to any additional effects GM1 might be exerting on membrane potential. Therefore, we investigated sperm membrane potential and found that GM1 indeed caused significant depolarizations. When data from single sperm incubated with 3mM 2-OHCD and then exposed to 25µM GM1 were analyzed as a single population, the GM1 induced average potential changes of +23.1mV±15 mV. However, we observed a larger depolarization (+30.3mV±15 mV) in the capacitated subpopulation (as indicated by a more hyperpolarized membrane potential of <−40mV (De La Vega-Beltran et al., 2012)) versus those being less hyperpolarized (>−40mV and considered non-capacitated, +18.9mV±14 mV, p=0.03 for comparison of randomly chosen paired samples, or p=0.02 if analyzed as unpaired samples; Figure S4). Together, these data show that not only did GM1 increase voltage sensitivity, making it more likely that the channel would open under more negative potentials, but it also shifted the membrane to a more depolarized state, and this change was enhanced in cells that had undergone sterol efflux.

Discussion

It is now recognized that the exquisite regulation of sperm function by lipids makes these cells useful models for fundamental studies of how lipids regulate cell function (Levental et al., 2011). As in sperm, sterols and GM1 play key regulatory roles in many physiological and pathological processes. Though examples include some of our most pressing medical problems ranging from diabetes to Alzheimer’s disease to atherosclerosis, our understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms through which lipids act in these processes is at a nascent stage. It is in the context of this larger challenge of cell biological understanding that we have explored how lipids control sperm function in fertilization, the initiating process of developmental biology.

Positive regulation of sperm function by lipids has been known for decades in the form of a strict requirement for sterol efflux. Conversely, SVS2 provides negative regulation, binding GM1 and retarding the capacitation process. Our investigations revealed that these lipids modulated CaV2.3 activity, which mediates a transient rise in Ca2+ that spatiotemporally encodes information required for subsequent AE. Mechanistically, we show that this functional regulation depended both on sugar and lipid components of GM1 and multiple subunits of CaV2.3.

The identity of sperm Ca2+ channels involved in fertilization has been controversial for some time, though the nature of that controversy has recently changed. High expression of CaV2.3 message in developing male germ cells (Lievano et al., 1996), was at odds with a lack of electrophysiological activity in those immature male germ cells (Arnoult et al., 1998; Sakata et al., 2001). Similarly, reports from Ca2+ imaging and pharmacologic studies in mature sperm that suggested possible CaV2.3 activity (Sakata et al., 2002; Wennemuth et al., 2000), stood in contrast with recent patch clamping experiments that show only CatSper activity (Lishko et al., 2011; Ren and Xia, 2010).

Several methodological differences can account for discrepancies between data obtained by patch clamping and our data (and those of others). First, reports that only CatSper (Kirichok and Lishko, 2011) or CatSper and Ksper activity (Zeng et al., 2013) are detectable note that channels gated or sensitized by other factors (e.g. changes in lipid composition such as sterol efflux or alteration of membrane rafts) would be missed. Second, sperm have scant cytoplasmic space and the membrane is tightly affixed to the underlying cytoskeleton (Noiles et al., 1997). Therefore, patching of mouse sperm is typically performed on residual blebs of cytoplasm lost from normal sperm, and these cells are also often swollen by incubation in hypotonic solutions. Channel activities dependent upon membrane organization or interactions with intracellular partners would likely be perturbed. Third, data presented here were collected at 37°C, whereas patch clamping was performed at room temperature (22–25°C), and phase transitions occur in sperm membranes between these temperatures (Holt and North, 1984; Wolf, 1990). This is potentially an important point for membrane lipid regulation of the channel, and one that should be investigated further using biophysical approaches. Fourth, our data were collected directly from the heads of motile, live sperm as opposed to cytoplasmic or proximal droplets from immotile, immature sperm. Lastly, the signal from a localized transient might be diminished in a whole cell patch at the cytoplasmic droplet (approximately 35 µm away). This distance could impart “space clamp” issues that arise from the fact that current signals are summed from areas with heterogeneous membrane potentials due to non-linear clamping of membrane domains with varying conductance (Bar-Yehuda and Korngreen, 2008). This problem is exacerbated in cells with elongated morphologies, such as sperm, in which multiple membrane micro- and macro-domains and diffusion barriers would have to be crossed for a transient in the apical acrosome to be detected in a cytoplasmic droplet at the flagellar annulus. Our finding of capacitation-dependent, lipid regulation of CaV2.3 provides a clear reason why CaV2.3 activity largely escaped detection previously, potentially resolving both sets of discrepancies in the literature.

These findings led us to generate the following model (Figure 6) of membrane lipid regulation of sperm function: 1) Under normal physiological conditions, GM1 and the α1E subunit co-localize to the fusogenic AA. 2) Binding of GM1 to components of seminal plasma such as SVS2 provides negative regulation, preventing the interaction of GM1’s extracellular sugars with the α2δ subunit. 3) High concentrations of membrane sterols reduce membrane fluidity and lateral diffusion of GM1, further decreasing the probability for stimulatory interactions. 4) During capacitation, SVS2 is lost from the plasma membrane. 5) Sterol efflux causes changes in membrane fluidity and dynamics promoting or altering interactions between GM1 and the CaV2.3 α2δ1 subunit, in addition to GM1’s local depolarizing effect on the membrane, leading to a focal Ca2+ transient. 6) That transient primes the sperm for a subsequent wave, originating from the direction of the posterior ring/connecting piece/flagellum, to facilitate AE.

Figure 6. Model for the regulation of sperm Ca2+ flux by the membrane lipid environment.

This model builds upon reports that sterol efflux can activate CatSper via alkalinization and hyperpolarization, and reports that SVS2 inhibits capacitation by binding GM1. Data presented in the current paper demonstrate that GM1 functionally regulates the activity of the CaV2.3 channel and that this is dependent upon the α2δ subunit. Transient Ca2+ rise through the α1E pore-forming subunit spatially and/or temporally encodes information that allows a subsequent Ca2+ wave to result in acrosome exocytosis. Future experiments will be needed to determine how the transient interacts with the wave and/or modulates the local membrane environment to enable fusion and exocytosis. In the figure, voltage dependent inactivation is abbreviated as “VDI.”.

In support of this last step of the model, our data showed that although alternative, compensatory GM1-Ca2+ mobilization pathways were present in sperm lacking CaV2.3, those transients were mis-localized and did not enable subsequent waves to culminate in AE. One possible explanation for the importance of the spatiotemporal properties of the transient is that it is involved in the assembly or priming of a functional excitosome complex consisting of SNAREs, synaptotagmin and CaV2.3 (Cohen and Atlas, 2004) which is required to enable acrosome and plasma membrane fusion in AE.

Our model could include alternative cellular events that would also increase GM1-CaV2.3 interactions. For example, point fusion events between the plasma membrane and acrosomal membrane are believed to occur late in capacitation and early in AE (Jin et al., 2011; Kim and Gerton, 2003). These fusions might result in lipid transfer between these membranes, providing additional GM1 in the APM or changing lipid dynamics within the plane of the plasma membrane. Note that the multiple possible factors promoting GM1-CaV2.3 interactions (SVS2 removal, sterol efflux, membrane fusions leading to more GM1 on the surface) are not mutually exclusive.

Through one or more of these factors, clustering of GM1 might promote voltagegated Ca2+ current in several ways: 1) modification of upstream or secondary signaling molecules (Maehashi et al., 2003); 2) direct interaction with channel subunits (Zhang et al., 2005); 3) induction of a local change in membrane potential by accumulation of negative surface charges (Piret et al., 2005); 4) local increase in driving force of current flow through open channels by concentrating cations, including Ca2+, in the extracellular space immediately adjacent to the plasma membrane due to the negative charge provided by GM1’s sialic acid residue; or 5) alteration of the electric field sensed by the channel’s gating elements induced by the sialic acid (Bennett et al., 1997).

One aspect of VGCC regulation that is in accordance with our data has been well established; namely, the role of the highly glycosylated, extracellular auxiliary α2δ subunit in increasing channel conductivity (see Davies et al., 2007 for review). Segregation of the α2δ subunit to membrane rafts has been hypothesized to prevent full activation of the channel until raft-association of the pore-forming subunit occurs (Davies et al., 2006). In contrast to some reports on its chronic effects (e.g. Hendrich et al., 2008), but in agreement with others (e.g. Peng et al., 2011), our data revealed an acute inhibition of Ca2+ transients and AE by GBP, which together with our voltage clamp data support a hypothesis in which the GM1-CaV2.3 regulatory interaction depends in part upon the α2δ1 subunit. Like the α2δ subunit itself, GM1 has both extracellular sugars and a domain within the membrane, and both GM1 and sterols are focally organized in dynamic raft microdomains in sperm (Selvaraj et al., 2009; Asano et al., 2009). Our finding that depolarization alone was not sufficient to activate the CaV2.3 channel-mediated transients (Figure S2), suggests that the α2δ might be segregated from the α1E subunit in the sperm head, leading to a significant reduction of the voltage sensitivity of the channel as evidenced by our voltage clamp data. In our growing appreciation of the functional effects of lipids, it is clear that not only are the species of lipid important, but also the organization and dynamics of those lipids in the local membrane microenvironment.

Our studies have answered some long-standing questions in development, such as how sterol efflux or the ganglioside GM1 can control whether a sperm can fertilize. We revealed surprising spatiotemporal complexities in how Ca2+ transients or waves can or can’t lead to exocytosis. Mechanistically, we defined requirements for the sugar and lipid components of GM1 to regulate the activity of the CaV2.3 channel in sperm, and using a reductionist, heterologous expression system, we showed that this interaction requires the α2δ1 subunit of the channel. These improvements in understanding the molecular nature of how lipids can alter cell function might lead to new pharmacological targets or manipulations not only in sperm, but also in the many other cell types in which lipids regulate physiological and pathological processes.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents and Animals

All reagents were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), unless otherwise noted. Monoclonal antibody against mouse α1E, α2δ subunits, and blocking peptide were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA) or AbGent (AbGent, SD). Goat anti-mouse serum secondary antibodies (Alexa-488 or Alexa-555 conjugated) were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Male CD-1 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Kingston, NY). Male and female B6129SF/J mice were purchased from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Sperm from young males (3–6 months) were used for all assays of function, but retired breeder CD-1 mice were used for preliminary studies and for some localization studies. All animal procedures were performed under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cornell University.

Sperm Collection and Handling

For murine sperm, a modified Whitten’s medium (MW; 22mM HEPES, 1.2mM MgCl2, 100mM NaCl, 4.7mM KCl, 1mM pyruvic acid, 4.8mM lactic acid hemi-Ca2+ salt, pH 7.35; (Travis et al., 2004)) was used for all incubations. Glucose (5.5mM), NaHCO3 (10mM), and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (2-OHCD; 3mM) were supplemented as needed. Cauda epididymal murine sperm collection was described previously (Travis et al., 2001). All steps of collection and washing were performed at 37°C using MW medium, using methods to minimize membrane damage. After the initial washes but prior to experimental incubations, motility assessment was carried out, and samples showing <60% motility were not used.

Sperm Capacitation and Induction of AE

2×106 sperm were incubated in 300µl of MW with glucose (base media) as non-capacitating media or MW base media supplemented with both 10mM NaHCO3 and 1mM 2-OHCD as capacitating conditions (pH=7.35). The dead spaces of tubes used for all incubations were filled with nitrogen to avoid the generation of bicarbonate anions in the aqueous media. Ca2+ channel inhibitors were added 10 minutes prior to the addition of AE agonists. Progesterone (3μg/ml final concentration, in DMSO) was used as a positive control to induce AE in capacitated murine sperm after 50 minutes of incubation. CTB (1.5μM final concentration, in PBS) was added where indicated to assess its affect on AE. The exogenous lipids ceramide, asialo-GM1, and GM1 (in DMSO; 25mM stock concentration) were also added (25μM) where indicated. Sperm were then processed for Coomassie assessment of AE as described previously (Visconti et al., 1999). Groups were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis/Wilcoxon test in Kaleidagraph and SAS v9.3.

Single Cell Ca2+ Imaging

Sperm from single mice were incubated with glucose (5.5mM) and fluo4-AM (0.5µM) for 1h at 37°C, with 2-OHCD (2mM) included where indicated. Following capacitation and dye loading, sperm were plated on poly-D-lysine-coated 35mm coverslip dishes (MatTek Corp. Ashland, MA), and 2ml of warm MW base media supplemented with 20mM CaCl2 were added. The dish with the sperm was then mounted on a Zeiss 510 microscope with a heated 100X oil immersion objective (37°C). Fluo4 was excited using the 488 nm line of a krypton/argon laser and viewed with a 505–550 nm BP filter. Selected cells were approached with a ~5 μm-diameter pulled-glass capillary, positioned within 100 μm from the cell and prefilled with stimulating solution. The stimulating solutions were made at 5X the normal concentration (e.g. GM1 or A-GM1=125µM, CTB=25µM), to compensate for the diffusion distance between the capillary and the cell. Sperm cells were imaged at 5–50 Hz while applying a puff of 10s/5psi from the pipette, controlled by a Picospritzer III (FMI Medical Instruments). Unless otherwise stated, all data are presented as mean±SEM. For each of the experiments, the number of cells analyzed (n) is presented in the text. Data were processed and plotted using Origin 8 (OriginLab) and Excel (Microsoft). Statistical comparisons were performed using either a Student’s t-test or a Wilcoxon test with indications as follows: *>0.05, **>0.01, ***<0.005.

Expression of CaV2.3 and Two-Electrode Voltage Clamp in Xenopus Oocytes

Human α1E CaV2.3 (#L27745) and rat β2A (#M80545) were kindly donated by N. Qin and L. Birnbaumer (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC). Rabbit skeletal α2δ1 (#M86621) was from A. Schwartz (University of Ohio, Athens, OH). Expression of channel subunits and two-electrode voltage clamp were preformed as previously described (Cohen and Atlas, 2004). Bath solutions contained 5 mM Ca(OH)2, 50 mM N-methyl-D-glucamine, 1 mM KOH, 40 mM tetraethyl ammonium, 5 mM HEPES, titrated to pH 7.5 with methanesulfonic acid CH3SO3HE. Experiments were carried out 3 times, with n>8 for each group in every experiment. GM1 was added to the bath solution prior to current recording. Peak current and G/Gmax values were analyzed by Clampfit 9.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

CaV2.3 mediates spatiotemporal regulation of acrosome exocytosis (AE)

GM1 regulates sperm Ca2+ influx, AE & fertilization via CaV2.3’s α1E & α2δ1 subunits

Mechanism of α1E regulation involves GM1’s lipid & sugar moieties & α2δ1

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-HD-045664 and DP-OD-006431 (A.J.T.), the Cornell College of Veterinary Medicine Dual DVM/PhD Degree Program (D.E.B.), and the Baker Institute for Animal Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Albillos A, Neher E, Moser T. R-Type Ca2+ channels are coupled to the rapid component of secretion in mouse adrenal slice chromaffin cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8323–8330. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-22-08323.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin AH, Bailey JL, Storey BT, Blasco L, Heyner S. A comparison of three methods for detecting the acrosome reaction in human spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:741–745. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoult C, Kazam IG, Visconti PE, Kopf GS, Villaz M, Florman HM. Control of the low voltage-activated calcium channel of mouse sperm by egg ZP3 and by membrane hyperpolarization during capacitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:6757–6762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnoult C, Villaz M, Florman HM. Pharmacological properties of the T-type Ca2+ current of mouse spermatogenic cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:1104–1111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano A, Selvaraj V, Buttke DE, Nelson JL, Green KM, Evans JE, Travis AJ. Biochemical characterization of membrane fractions in murine sperm: identification of three distinct sub-types of membrane rafts. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:537–548. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Yehuda D, Korngreen A. Space-clamp problems when voltage clamping neurons expressing voltage-gated conductances. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:1127–1136. doi: 10.1152/jn.01232.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett E, Urcan MS, Tinkle SS, Koszowski AG, Levinson SR. Contribution of sialic acid to the voltage dependence of sodium channel gating. A possible electrostatic mechanism. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:327–343. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Stotz SC, Spaetgens RL, Dayanithi G, Lemos J, Nargeot J, Zamponi GW. Interaction of SNX482 with domains III and IV inhibits activation gating of alpha(1E) (Ca(V)2.3) calcium channels. Biophys J. 2001;81:79–88. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75681-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourinet E, Zamponi GW, Stea A, Soong TW, Lewis BA, Jones LP, Yue DT, Snutch TP. The alpha 1E calcium channel exhibits permeation properties similar to low-voltage-activated calcium channels. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4983–4993. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-04983.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttke DE, Nelson JL, Schlegel PN, Hunnicutt GR, Travis AJ. Visualization of GM1 with cholera toxin B in live epididymal versus ejaculated bull, mouse, and human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:889–895. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.046219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson RO, Masco D, Brooker G, Spiegel S. Endogenous ganglioside GM1 modulates L-type calcium channel activity in N18 neuroblastoma cells. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2272–2281. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02272.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:521–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R, Atlas D. R-type voltage-gated Ca(2+) channel interacts with synaptic proteins and recruits synaptotagmin to the plasma membrane of Xenopus oocytes. Neuroscience. 2004;128:831–841. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darszon A, Acevedo JJ, Galindo BE, Hernandez-Gonzalez EO, Nishigaki T, Trevino CL, Wood C, Beltran C. Sperm channel diversity and functional multiplicity. Reproduction. 2006;131:977–988. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A, Douglas L, Hendrich J, Wratten J, Tran Van Minh A, Foucault I, Koch D, Pratt WS, Saibil HR, Dolphin AC. The calcium channel alpha2delta-2 subunit partitions with CaV2.1 into lipid rafts in cerebellum: implications for localization and function. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8748–8757. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2764-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A, Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Wratten J, Douglas L, Dolphin AC. Functional biology of the alpha(2)delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Vega-Beltran JL, Sanchez-Cardenas C, Krapf D, Hernandez-Gonzalez EO, Wertheimer E, Trevino CL, Visconti PE, Darszon A. Mouse sperm membrane potential hyperpolarization is necessary and sufficient to prepare sperm for the acrosome reaction. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:44384–44393. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.393488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffier J, Boisseau S, Serres C, Chen CC, Kim D, Stamboulian S, Shin HS, Campbell KP, De Waard M, Arnoult C. Expression, localization and functions in acrosome reaction and sperm motility of Ca(V)3.1 and Ca(V)3.2 channels in sperm cells: an evaluation from Ca(V)3.1 and Ca(V)3.2 deficient mice. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:753–763. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Xie X, Ledeen RW, Wu G. Characterization of cholera toxin B subunit-induced Ca(2+) influx in neuroblastoma cells: evidence for a voltage-independent GM1 ganglioside-associated Ca(2+) channel. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:669–680. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florman HM, Jungnickel MK, Sutton KA. Regulating the acrosome reaction. Int J Dev Biol. 2008;52:503–510. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082696hf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami K, Yoshida M, Inoue T, Kurokawa M, Fissore RA, Yoshida N, Mikoshiba K, Takenawa T. Phospholipase Cdelta4 is required for Ca2+ mobilization essential for acrosome reaction in sperm. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:79–88. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabsch H, Pereverzev A, Weiergraber M, Schramm M, Henry M, Vajna R, Beattie RE, Volsen SG, Klockner U, Hescheler J, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of alpha1E voltage-gated Ca(2+) channel isoforms in cerebellum, INS-1 cells, and neuroendocrine cells of the digestive system. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47:981–994. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Heblich F, Nieto-Rostro M, Watschinger K, Striessnig J, Wratten J, Davies A, Dolphin AC. Pharmacological disruption of calcium channel trafficking by the alpha2delta ligand gabapentin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3628–3633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708930105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HC, Suarez SS. An inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor-gated intracellular Ca(2+) store is involved in regulating sperm hyperactivated motility. Biol Reprod. 2001;65:1606–1615. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod65.5.1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt WV, North RD. Partially irreversible cold-induced lipid phase transitions in mammalian sperm plasma membrane domains: freeze-fracture study. J Exp Zool. 1984;230:473–483. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402300316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Gonzalez MC, Gu Y, Kirkman-Brown J, Barratt CL, Publicover S. Patch-clamp 'mapping' of ion channel activity in human sperm reveals regionalisation and co-localisation into mixed clusters. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:801–808. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin M, Fujiwara E, Kakiuchi Y, Okabe M, Satouh Y, Baba SA, Chiba K, Hirohashi N. Most fertilizing mouse spermatozoa begin their acrosome reaction before contact with the zona pellucida during in vitro fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:4892–4896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018202108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungnickel MK, Marrero H, Birnbaumer L, Lemos JR, Florman HM. Trp2 regulates entry of Ca2+ into mouse sperm triggered by egg ZP3. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:499–502. doi: 10.1038/35074570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano N, Yoshida K, Iwamoto T, Yoshida M. Ganglioside GM1 mediates decapacitation effects of SVS2 on murine spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 2008;79:1153–1159. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.069054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KS, Gerton GL. Differential release of soluble and matrix components: evidence for intermediate states of secretion during spontaneous acrosomal exocytosis in mouse sperm. Dev Biol. 2003;264:141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirichok Y, Lishko PV. Rediscovering Sperm Ion Channels with the Patch-Clamp Technique. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17:478–499. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levental I, Grzybek M, Simons K. Raft domains of variable properties and compositions in plasma membrane vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:11411–11416. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105996108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievano A, Santi CM, Serrano CJ, Trevino CL, Bellve AR, Hernandez-Cruz A, Darszon A. T-type Ca2+ channels and alpha1E expression in spermatogenic cells, and their possible relevance to the sperm acrosome reaction. FEBS Lett. 1996;388:150–154. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00515-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishko PV, Botchkina IL, Kirichok Y. Progesterone activates the principal Ca2+ channel of human sperm. Nature. 2011;471:387–391. doi: 10.1038/nature09767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Gonzalez I, Olamendi-Portugal T, De la Vega-Beltran JL, Van der Walt J, Dyason K, Possani LD, Felix R, Darszon A. Scorpion toxins that block T-type Ca2+ channels in spermatogenic cells inhibit the sperm acrosome reaction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;300:408–414. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02859-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehashi E, Sato C, Ohta K, Harada Y, Matsuda T, Hirohashi N, Lennarz WJ, Kitajima K. Identification of the sea urchin 350-kDa sperm-binding protein as a new sialic acid-binding lectin that belongs to the heat shock protein 110 family: implication of its binding to gangliosides in sperm lipid rafts in fertilization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42050–42057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307493200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noiles EE, Thompson KA, Storey BT. Water permeability, Lp, of the mouse sperm plasma membrane and its activation energy are strongly dependent on interaction of the plasma membrane with the sperm cytoskeleton. Cryobiology. 1997;35:79–92. doi: 10.1006/cryo.1997.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng BW, Justice JA, Zhang K, Li JX, He XH, Sanchez RM. Gabapentin promotes inhibition by enhancing hyperpolarization-activated cation currents and spontaneous firing in hippocampal CA1 interneurons. Neurosci Lett. 2011;494:19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereverzev A, Salehi A, Mikhna M, Renstrom E, Hescheler J, Weiergraber M, Smyth N, Schneider T. The ablation of the Ca(v)2.3/E-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel causes a mild phenotype despite an altered glucose induced glucagon response in isolated islets of Langerhans. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;511:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piret J, Schanck A, Delfosse S, Van Bambeke F, Kishore BK, Tulkens PM, Mingeot-Leclercq MP. Modulation of the in vitro activity of lysosomal phospholipase A1 by membrane lipids. Chem Phys Lipids. 2005;133:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Olcese R, Stefani E, Birnbaumer L. Modulation of human neuronal alpha 1E-type calcium channel by alpha 2 delta-subunit. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1324–C1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.5.C1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall A, Tsien RW. Pharmacological dissection of multiple types of Ca2+ channel currents in rat cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2995–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02995.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandra B, Joshi PG. Regulation of transmembrane signaling by ganglioside GM1: interaction of anti-GM1 with Neuro2a cells. J Neurochem. 1999;73:557–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren D, Xia J. Calcium signaling through CatSper channels in mammalian fertilization. Physiology (Bethesda) 2010;25:165–175. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00049.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P, Etheridge S, Song L, Shah R, Fitzgerald EM, Jones OT. Targeting of voltage-gated calcium channel alpha2delta-1 subunit to lipid rafts is independent from a GPI-anchoring motif. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata Y, Saegusa H, Zong S, Osanai M, Murakoshi T, Shimizu Y, Noda T, Aso T, Tanabe T. Analysis of Ca(2+) currents in spermatocytes from mice lacking Ca(v)2.3 (alpha(1E)) Ca(2+) channel. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:1032–1036. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata Y, Saegusa H, Zong S, Osanai M, Murakoshi T, Shimizu Y, Noda T, Aso T, Tanabe T. Ca(v)2.3 (alpha1E) Ca2+ channel participates in the control of sperm function. FEBS Lett. 2002;516:229–233. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02529-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj V, Asano A, Buttke DE, McElwee JL, Nelson JL, Wolff CA, Merdiushev T, Fornes MW, Cohen AW, Lisanti MP, et al. Segregation of micron-scale membrane sub-domains in live murine sperm. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:636–646. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj V, Asano A, Buttke DE, Sengupta P, Weiss RS, Travis AJ. Mechanisms underlying the micron-scale segregation of sterols and GM1 in live mammalian sperm. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:522–536. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraj V, Buttke DE, Asano A, McElwee JL, Wolff CA, Nelson JL, Klaus AV, Hunnicutt GR, Travis AJ. GM1 dynamics as a marker for membrane changes associated with the process of capacitation in murine and bovine spermatozoa. J Androl. 2007;28:588–599. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.002279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano CJ, Trevino CL, Felix R, Darszon A. Voltage-dependent Ca(2+) channel subunit expression and immunolocalization in mouse spermatogenic cells and sperm. FEBS Lett. 1999;462:171–176. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01518-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamboulian S, Kim D, Shin HS, Ronjat M, De Waard M, Arnoult C. Biophysical and pharmacological characterization of spermatogenic T-type calcium current in mice lacking the CaV3.1 (alpha1G) calcium channel: CaV3.2 (alpha1H) is the main functional calcium channel in wild-type spermatogenic cells. J Cell Physiol. 2004;200:116–124. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CP. Mechanisms of analgesia by gabapentin and pregabalin--calcium channel alpha2-delta [Cavalpha2-delta] ligands. Pain. 2009;142:13–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis AJ, Jorgez CJ, Merdiushev T, Jones BH, Dess DM, Diaz-Cueto L, Storey BT, Kopf GS, Moss SB. Functional relationships between capacitation-dependent cell signaling and compartmentalized metabolic pathways in murine spermatozoa. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7630–7636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis AJ, Kopf GS. The role of cholesterol efflux in regulating the fertilization potential of mammalian spermatozoa. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:731–736. doi: 10.1172/JCI16392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis AJ, Tutuncu L, Jorgez CJ, Ord TS, Jones BH, Kopf GS, Williams CJ. Requirements for glucose beyond sperm capacitation during in vitro fertilization in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 2004;71:139–145. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.025809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vajna R, Klockner U, Pereverzev A, Weiergraber M, Chen X, Miljanich G, Klugbauer N, Hescheler J, Perez-Reyes E, Schneider T. Functional coupling between 'R-type' Ca2+ channels and insulin secretion in the insulinoma cell line INS-1. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:1066–1075. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.01969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visconti PE, Galantino-Homer H, Ning X, Moore GD, Valenzuela JP, Jorgez CJ, Alvarez JG, Kopf GS. Cholesterol efflux-mediated signal transduction in mammalian sperm. beta-cyclodextrins initiate transmembrane signaling leading to an increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation and capacitation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3235–3242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Dayanithi G, Newcomb R, Lemos JR. An R-type Ca(2+) current in neurohypophysial terminals preferentially regulates oxytocin secretion. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9235–9241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09235.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiergraber M, Kamp MA, Radhakrishnan K, Hescheler J, Schneider T. The Ca(v)2.3 voltage-gated calcium channel in epileptogenesis--shedding new light on an enigmatic channel. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30:1122–1144. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wennemuth G, Westenbroek RE, Xu T, Hille B, Babcock DF. CaV2.2 and CaV2.3 (N- and R-type) Ca2+ channels in depolarization-evoked entry of Ca2+ into mouse sperm. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21210–21217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westenbroek RE, Babcock DF. Discrete regional distributions suggest diverse functional roles of calcium channel alpha1 subunits in sperm. Dev Biol. 1999;207:457–469. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiser O, Cohen R, Atlas D. Ionic dependence of Ca2+ channel modulation by syntaxin 1A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3968–3973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052017299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf DE, Maynard VM, McKinnon CA, Melchior DL. Lipid domains in the ram sperm plasma membrane demonstrated by differential scanning calorimetry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:6893–6896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia J, Ren D. The BSA-induced Ca2+ influx during sperm capacitation is CATSPER channel-dependent. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:119. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatomi Y, Igarashi Y, Hakomori S. Effects of exogenous gangliosides on intracellular Ca2+ mobilization and functional responses in human platelets. Glycobiology. 1996;6:347–353. doi: 10.1093/glycob/6.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunes R, Michaut M, Tomes C, Mayorga LS. Rab3A triggers the acrosome reaction in permeabilized human spermatozoa. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1084–1089. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.4.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng XH, Navarro B, Xia XM, Clapham DE, Lingle CJ. Simultaneous knockout of Slo3 and CatSper1 abolishes all alkalization- and voltage-activated current in mouse spermatozoa. J Gen Physiol. 2013;142:305–313. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhao Y, Duan J, Yang F, Zhang X. Gangliosides activate the phosphatase activity of the erythrocyte plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2005;444:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Fan X, Yang F, Zhang X. Gangliosides modulate the activity of the plasma membrane Ca(2+)-ATPase from porcine brain synaptosomes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;427:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.