Abstract

Background

Maté tea is non-alcoholic infusion widely consumed in southern South America, and may increase risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and other cancers due to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and/or thermal injury.

Methods

We pooled two case-control studies: a 1988–2005 Uruguay study and a 1986–1992 multinational study in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, including 1,400 cases and 3,229 controls. We computed odds ratios (OR) and fitted a linear excess odds ratio (EOR) model for cumulative maté consumption in liters/day-year (LPDY).

Results

The adjusted OR for ESCC with 95% confidence interval (CI) by ever compared with never use of maté was 1.60 (1.2,2.2). ORs increased linearly with LPDY (test of non-linearity, P=0.69). The estimate of slope (EOR/LPDY) was 0.009 (0.005,0.014) and did not vary with daily intake, indicating maté intensity did not influence the strength of association. EOR/LPDY estimates for consumption at warm, hot and very hot beverage temperatures were 0.004 (−0.002,0.013), 0.007 (0.003,0.013) and 0.016 (0.009,0.027), respectively, and differed significantly (P<0.01). EOR/LPDY estimates were increased in younger (<65) individuals and never alcohol drinkers, but these evaluations were post hoc, and were homogeneous by sex.

Conclusions

ORs for ESCC increased linearly with cumulative maté consumption and were unrelated to intensity, so greater daily consumption for shorter duration or lesser daily consumption for longer duration resulted in comparable ORs. The strength of association increased with higher mate temperatures.

Impact

Increased understanding of cancer risks with maté consumption enhances the understanding of the public health consequences given its purported health benefits.

1.0 Introduction

Maté tea is an infusion made from leaves of the tree Ilex paraguariensis, a member of the Aquifoliaceae (holly) family (1, 2). It is a non-alcoholic beverage consumed throughout southern South America, and is gaining broader acceptance in other areas of the world as a tea and dietary supplement based on purported health benefits, such as lowered cholesterol levels, improved cardiovascular health and obesity management (2, 3). However, studies have linked maté consumption with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), as well as cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, lung, kidney and bladder (4–13). The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) designated hot maté drinking a probable human carcinogen (group 2A) (1). Proposed carcinogenic mechanisms include thermal injury from repeated high temperature exposure and exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), a production-related contaminant (1, 14–17).

While studies have associated maté consumption with ESCC, there has been no quantitative evaluation of the relationship between ESCC and total exposure, as measured by liters/day-year (LPDY), the product of lifetime mean liters/day (LPD) and years of consumption. In addition, evaluations of potential effect modifiers, such as age, sex, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption, have been limited.

We pooled data from two large case-control studies of ESCC, one an aggregation of five component studies. Our goals were to evaluate: (i) the quantitative relationship between ESCC and LPDY of maté consumption; (ii) the impact of LPD on the strength of association; and (iii) potential effect modifiers, including maté temperature, sex, age, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption.

2.0 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study data

Uruguay case-control study (5)

Cases included patients who were incident between 1990–2004, aged 35–85 years in medical records of the Oncology Institute Cancer Registry with histopathologically confirmed ESCC. Patients had to be mentally competent for interview, diagnosed within the previous four months and resident in Uruguay for ≥10 years.

Controls included patients admitted to the same institution during the same period with conditions unrelated to tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption and with comparable residency, and were frequency matched to cases by age and sex. Within the frequency matched groups, investigators enrolled greater numbers of female controls.

Interviews occurred shortly after hospital admittance. Questionnaires collected information on demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, personal and family history, maté drinking, alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking. For alcohol intake, we calculated milliliters (ml) of ethanol/day by summing ethanol/day for a standard serving of each beverage type.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Multinational Case-Control Study (4, 18)

Between 1986 and 1992, investigators conducted four hospital-based case-control studies of ESCC in Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, the latter independent of the Uruguay Study described above. Investigators further extended this Uruguay component, which represented a fifth study. IARC coordinated the studies, which we have collectively denoted as the IARC Multinational Study. Results have been published previously (4, 18–22). The components utilized similar protocols and questionnaires, allowing for local adaptations.

Cases included histologically confirmed ESCC patients (the Paraguay component also accepted cytological or radiological diagnoses), diagnosed within the previous 3–6 months, resident in the area for ≥5 years and competent for interview. In Argentina, cases were ascertained from the 10 main hospitals of greater La Plata (19). In Brazil, cases were ascertained from the 8 main hospitals and 3 radiotherapy units of Port Alegre and Pelotas, at the time the 2 largest cities in the state of Rio Grande do Sul (21). In Uruguay, cases came from the 4 main hospitals in Montevideo, which covered about 45% of the city's population and about 55% of the population of the rest of the country (4, 22). Investigators checked identification numbers and names to ensure there was no duplication or overlap of cases among the various Uruguay component studies. In Paraguay, subjects were ascertained from the 4 hospitals, private clinics, pathology laboratories and radiology clinics in Asuncion (20). The case participation rate in all studies was high (90.0 to 99.2%).

Controls who were admitted during the same period were frequency matched to cases on hospital, gender, age and residence period, and included patients with diseases unrelated to alcohol or tobacco. Diagnostic categories were given previously (13, 19–22). Investigators replaced controls that refused to participate, except in Paraguay, although control participation rate was high (97.0%).

Questionnaires ascertained information on demographic and socio-economic characteristics, tobacco smoking, alcohol drinking and consumption of hot beverages including mate, tea and coffee. Beverage temperatures were self-assessed. Proxy interviews were not accepted.

The Institutional Review Board or Research Ethics Committee for each study approved data collection and, if required, participation in the pooling.

2.2 Statistical methods

For categorical variables, we computed odds ratios (OR) using standard logistic regression (23). For continuous LPDY, d, ORs were not log-linear. We thus fitted the model OR(d,z) = exp(αz)×OR(d), where

| (1) |

z was a vector of adjustment variables with parameters α, while β was the excess odds ratio per LPDY (EOR/LPDY), a measure of strength of association. We replaced d with d×exp{θ ln(d)}=d1 + θ and used the likelihood ratio to test no departure from linearity (θ=0).

We evaluated effect modification by examining variations in the trend of ORs by LPDY across a categorical factor (f). For factor f with S categories, s=1,…,S, we fitted

| (2) |

where βs parameters replaced β and ds equaled d within category s and zero otherwise. If f was unrelated to maté consumption, e.g., sex, then z included f as an adjustment variable. If f was related to maté consumption, e.g., LPD or beverage temperature, then z did not include f since no adjustment in never-drinkers was required. We compared deviances for model (1) and model (2) to test homogeneity of slopes, β1 =…= βS = β, i.e., no effect modification. We replaced ds with ds × exp{θs ln(ds)} to test no departure from linearity within category (θs=0).

We used the Epicure program to estimate ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CI), fit models and derive likelihood-based CIs for β estimates (24).

2.3 Model adjustment factors

Analyses adjusted for joint categories of study/component (6 levels), cigarette smoking in pack-years (0, <30, 30–39, 40–59, 60–79, ≥80) and alcohol consumption in ml-ethanol/day-years (0, <1,170, 1,170–2,439, 2,440–4,679, 4,680–9,359, ≥9,360), and for age (<55, 55–64, 65–74, ≥75 years), sex, cigarettes/day (<10, 10–19,20–29, ≥30), ml-ethanol/day (<32, 33–77, 78–155, ≥156), years of education (<3, 3–5, ≥6 for the Uruguay Study and <4, 4–6, ≥7 for the IARC Study) and for the Uruguay Study income (< US$120, ≥US$120, missing) and residency (urban, rural).

ORs by LPDY increased linearly in the IARC data and in the Uruguay data, but only among maté drinkers in the latter. For Uruguay data, we defined a fixed offset to adjust for ever and never maté drinkers using the model OR(d) = exp{α I(d)} × {1 + β d}, where I(d) equaled one for d>0 and zero otherwise. The estimate, exp{α}, was 2.42 (95% CI, 1.5, 2.9), and represented the LPDY-adjusted OR of ever relative to never consumed maté. A detailed examination identified a small subgroup responsible for the excess. The subgroup included male (3 cases and 53 controls) and female (1 case and 61 controls) urban residents who abstained from alcohol, with ORs for ever consumed maté of 4.24 (1.1, 16.7) and 13.8 (1.8, 105.8), respectively. We fixed the offset to −ln(4.24) and −ln(13.8) for Uruguay male and female urban residents who never consumed alcohol or maté and zero otherwise. The offset essentially served to replace the observed case to control odds with the expected odds, eliminating the non-linearity. See details in Supplemental Material and comments in the Discussion. The use of a fixed offset was an a priori decision, due to a concern about the possibility of broad impact on ORs from this small, highly influential subgroup. Alternatively, we could have introduced an indicator variable for this subgroup and estimated its effect, or have omitted these subjects. Regardless of approach, inference was unaffected.

3.0 Results

3.1 Odds ratios for adjustment and other factors

There were 1,400 cases (1,085 males and 315 females) and 3,229 controls (2,279 males and 950 females) (Table 1). ORs increased with pack-years of smoking, cigarettes/day, cumulative alcohol consumption and alcohol intensity in both studies (P<0.01). ORs increased with use of mixed/black-only tobacco cigarettes compared to blond-only tobacco cigarettes, achieving statistical significance in the IARC Study and the pooled data.

Table 1.

Odds ratios (OR) by characteristics of data from the Uruguay and IARC Multinational Case-Control Studies.

| Uruguay Study | IARC Study | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | ORa | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | ORa | 95% CI | |

| Subjects | 612 | 1,518 | 788 | 1,711 | ||||

| Study componentb | ||||||||

| Argentina | 125 | 254 | ||||||

| Brazil | 159 | 323 | ||||||

| Paraguay | 122 | 368 | ||||||

| Uruguay-I | 247 | 497 | ||||||

| Uruguay-II | 135 | 269 | ||||||

| Ageb | ||||||||

| <55 | 89 | 227 | 145 | 334 | ||||

| 55–64 | 151 | 342 | 261 | 550 | ||||

| 65–74 | 218 | 563 | 250 | 581 | ||||

| ≥75 | 154 | 386 | 132 | 246 | ||||

| Sexb | ||||||||

| Males | 465 | 930 | 620 | 1349 | ||||

| Female | 147 | 588 | 168 | 362 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| Ic | 168 | 425 | 1.00 | 423 | 755 | 1.00 | ||

| II | 225 | 571 | 1.21 | (0.9,1.6) | 320 | 803 | 0.75 | (0.6,0.9) |

| III | 219 | 522 | 1.55 | (1.2,2.1) | 45 | 153 | 0.54 | (0.4,0.8) |

| Pd | 0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Income/monthe | ||||||||

| <$US120 | 288 | 673 | 1.00 | |||||

| ≥$US120 | 258 | 665 | 0.94 | (0.7–1.2) | ||||

| Missing | 66 | 180 | 0.72 | (0.5–1.0) | ||||

| P | 0.57 | |||||||

| Residencee | ||||||||

| Urban | 433 | 1,168 | 1.00 | |||||

| Rural | 179 | 350 | 1.38 | (1.1–1.8) | ||||

| P | 0.01 | |||||||

| Pack-years | ||||||||

| 0 | 133 | 743 | 1.00 | 138 | 611 | 1.00 | ||

| <30 | 113 | 363 | 1.81 | (1.3–2.6) | 250 | 598 | 2.07 | (1.5,2.8) |

| 30–39 | 51 | 107 | 2.80 | (1.8–4.4) | 78 | 119 | 3.31 | (2.2,5.0) |

| 40–59 | 141 | 181 | 4.00 | (2.7–5.8) | 159 | 187 | 3.93 | (2.7,5.6) |

| 60–79 | 74 | 60 | 5.91 | (3.7–9.5) | 62 | 79 | 3.06 | (1.9,4.9) |

| ≥80 | 100 | 64 | 8.09 | (5.2–12.6) | 101 | 117 | 3.05 | (2.0,4.6) |

| P | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Cigarettes/day | ||||||||

| 0 | 133 | 743 | 1.00 | 138 | 611 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–10 | 51 | 186 | 1.64 | (1.1–2.5) | 135 | 336 | 1.95 | (1.4,2.7) |

| 10–19 | 88 | 263 | 1.82 | (1.2–2.7) | 144 | 257 | 2.86 | (2.0,4.1) |

| 20–29 | 160 | 214 | 3.88 | (2.7–5.6) | 201 | 279 | 3.35 | (2.4,4.7) |

| ≥30 | 180 | 112 | 8.30 | (5.6–12.2) | 170 | 228 | 2.89 | (2.0,4.1) |

| P | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Type of tobaccof | ||||||||

| Blond-only | 164 | 316 | 1.00 | 230 | 509 | 1.00 | ||

| Mixed/black-only | 273 | 373 | 1.19 | (0.9–1.6) | 356 | 508 | 1.62 | (1.2,2.1) |

| P | 0.24 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Ethanol (ml)/day-years | ||||||||

| 0 | 210 | 842 | 1.00 | 172 | 761 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–1,169 | 41 | 142 | 0.94 | (0.6–1.4) | 143 | 374 | 2.01 | (1.5,2.7) |

| 1,170–2,339 | 52 | 147 | 1.03 | (0.7–1.5) | 110 | 192 | 3.05 | (2.2,4.3) |

| 2,340–4,679 | 78 | 161 | 1.26 | (0.9–1.8) | 133 | 191 | 3.99 | (2.8,5.6) |

| 4,680–9,359 | 121 | 160 | 2.00 | (1.4–2.8) | 113 | 124 | 5.46 | (3.8,7.9) |

| ≥9,360 | 110 | 66 | 3.73 | (2.5–5.6) | 117 | 69 | 10.0 | (6.7,15.1) |

| P | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

| Ethanol (ml)/day | ||||||||

| 0 | 210 | 842 | 1.00 | 172 | 761 | 1.00 | ||

| 1–32 | 50 | 161 | 1.03 | (0.7,1.5) | 146 | 368 | 2.10 | (1.6,2.8) |

| 32–77 | 77 | 221 | 0.92 | (0.6,1.3) | 136 | 267 | 2.73 | (2.0,3.7) |

| 78–155 | 110 | 169 | 1.72 | (1.2,2.4) | 171 | 201 | 5.21 | (3.7,7.2) |

| ≥156 | 165 | 125 | 3.10 | (2.2,4.4) | 163 | 114 | 8.20 | (5.7,11.7) |

| P | <0.01 | <0.01 | ||||||

ORs and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from logistic regression that included all variables in the table as well as cumulative and liters/day of mate consumption. Models included a sex-specific fixed offset variable for the Uruguay data to account for differential effects of mate consumption in urban, never alcohol consumers. Adjustment variables for ORs by pack-years (cigarettes/day) omit cigarettes/day (pack-years). Adjustment variables for ORs by ethanol/day-years (ethanol/day) omit ethanol/day (ethanol/day-years).

Study, age and sex were design variables and OR were omitted.

For Uruguay: levels represent 0–2, 3–5, 6+ years; and for IARC, levels represent 0–3, 4–6, 7+ years.

P-value for one degree of freedom score test of trend.

Information collected only for the Uruguay Study.

Males only. ORs relative to blond tobacco only smokers and adjusted for variables in the table.

3.2 Marginal odds ratios for maté consumption

In the Uruguay Study, 95.6% of cases and 87.5% of controls and in the IARC Study 92.9% of cases and 87.0% of controls ever drank maté. Among drinkers, Uruguay cases had greater mean intensity, duration and total intake (1.2 liters/day, 52.3 years and 64.8 LPDY, respectively) compared to IARC cases (1.1 liters/day, 47.0 years and 54.3 LPDY). For controls, these maté-related metrics were also greater in the Uruguay Study (1.1, 50.8 and 55.3) than in the IARC Study (0.9, 44.9 and 40.8). Intake for the two Uruguay components of the IARC Study was comparable to intake for the Uruguay Study, and generally exceeded intake for the Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay components of the IARC Study (see Supplemental Table B1).

The overall adjusted OR for ESCC by ever compared with never use of maté was 1.60 (1.2,2.2) (Table 2) ORs by cumulative maté consumption and maté intensity increased in each study and the pooled data, with stronger associations in the IARC data. The offset modification greatly influenced the Uruguay results, as without the offset ORs were 1.0, 2.3, 2.8, 3.5, 2.0, 3.3 for LPDY (P<0.01) and 1.0, 2.5 2.8, 3.2, 2.6 for LPD (P=0.04) for their respective categories.

Table 2.

Numbers of subjects, odds ratiosa (ORs) and 95% confidence limits (CI) for mate intake in liters/day (LPD), cumulative mate consumption in liters/day-years (LPDY) and related variables. Data from the Uruguay and IARC Multinational Case-Control Studies.

| Uruguay Study | IARC Study | Pooled Data | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | OR | 95% CI | Cases | Controls | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Never-drinkerb | 27 | 190 | 1.00 | 56 | 223 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Ever-drinker | 583 | 1,311 | 1.56 | (0.9,2.6) | 725 | 1,480 | 1.61 | (1.1,2.3) | 1.60 | (1.2,2.2) |

| Cumulative mate consumption (LPDY) | ||||||||||

| 1–29 | 101 | 340 | 1.29 | (0.8,2.2) | 248 | 675 | 1.38 | (0.9,2.1) | 1.34 | (1.0,1.8) |

| 30–49 | 133 | 319 | 1.58 | (0.9,2.7) | 167 | 389 | 1.37 | (0.9,2.1) | 1.45 | (1.0,2.0) |

| 50–69 | 178 | 334 | 1.95 | (1.1,3.3) | 134 | 223 | 2.01 | (1.3,3.1) | 1.99 | (1.4,2.8) |

| 70–99 | 67 | 178 | 1.12 | (0.6,2.0) | 82 | 109 | 2.54 | (1.5,4.2) | 1.64 | (1.1,2.4) |

| ≥100 | 106 | 157 | 1.89 | (1.1,3.3) | 101 | 92 | 3.60 | (2.2,6.0) | 2.53 | (1.8,3.6) |

| Pc | 0.08 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Mate intake (liters/day) | ||||||||||

| 0.1–1.0 | 149 | 455 | 1.41 | (0.8,2.4) | 318 | 861 | 1.28 | (0.9,1.9) | 1.33 | (1.0,1.8) |

| 1.0–1.9 | 299 | 661 | 1.58 | (1.0,2.6) | 264 | 481 | 1.85 | (1.2,2.8) | 1.71 | (1.3,2.3) |

| 2.0–2.9 | 104 | 169 | 1.82 | (1.0,3.2) | 103 | 108 | 3.14 | (1.9,5.4) | 2.38 | (1.7,3.4) |

| ≥3.0 | 33 | 43 | 1.46 | (0.7,3.0) | 47 | 38 | 4.69 | (2.5,8.8) | 2.77 | (1.7,4.4) |

| P | 0.37 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Temperature | ||||||||||

| Warm | 48 | 212 | 0.93 | (0.5,1.7) | 120 | 285 | 1.38 | (0.9,2.2) | 1.20 | (0.8,1.7) |

| Hot | 417 | 914 | 1.64 | (1.0,2.7) | 512 | 1085 | 1.53 | (1.0,2.2) | 1.61 | (1.2,2.2) |

| Very hot | 120 | 202 | 1.79 | (1.0,3.1) | 93 | 110 | 2.61 | (1.6,4.2) | 2.15 | (1.5,3.1) |

| P | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |||||||

| Years since last mated | ||||||||||

| 0 | 523 | 1201 | 1.00 | 630 | 1303 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1–4 | 37 | 50 | 1.50 | (0.9,2.5) | 44 | 70 | 1.41 | (0.9,2.2) | 1.45 | (1.0,2.0) |

| 5+ | 23 | 60 | 0.87 | (0.5,1.5) | 51 | 107 | 1.04 | (0.7,1.6) | 0.96 | (0.7,1.3) |

| Pd | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.22 | |||||||

| Age 1st mated | ||||||||||

| <12 | 239 | 362 | 1.00 | 238 | 438 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 12–16 | 217 | 623 | 0.44 | (0.3,0.6) | 234 | 380 | 1.31 | (1.0,1.8) | 0.74 | (0.6,0.9) |

| ≥17 | 127 | 326 | 0.58 | (0.4,0.8) | 253 | 662 | 0.93 | (0.7,1.3) | 0.71 | (0.6,0.9) |

| P | <0.01 | 0.55 | <0.01 | |||||||

ORs from logistic regression for the mate consumption variable, adjusted by smoking (pack-years, cigarettes/day), alcohol consumption (drink-years, drinks/day), age, sex, sex by education and for Uruguay income and urban/rural residence. Pooled ORs further adjusted for study. Models included a sex-specific fixed offset variable for the Uruguay data to account for differential effects of mate consumption in urban, never alcohol consumers. Numbers of cases and controls differ slightly from Table 1 due to missing data.

Referent category, except where noted. Numbers of cases and controls vary due to missing data.

P-value for the score test of no trend.

ORs and P-values computed among mate drinkers only relative to the lowest category.

We evaluated ORs by self-reported maté temperature, warm, hot or very hot, and found that ORs increased significantly with temperature, although the OR for warm maté consumption was not statistically significant. Few users ceased consumption (8.4% and 12.0% in Uruguay and IARC controls, respectively) and ORs varied inconsistently with years since cessation. Among drinkers, ORs were increased at younger age at first use in the Uruguay data and unrelated in the IARC data.

OR trends were homogeneous across studies for maté temperature (p=0.85) and cessation (p=0.84), but differed for cumulative intake, intensity and age at first use (p<0.01) (not shown).

3.3 Joint odds ratios for cumulative liters/day-years and liters/day of maté consumption

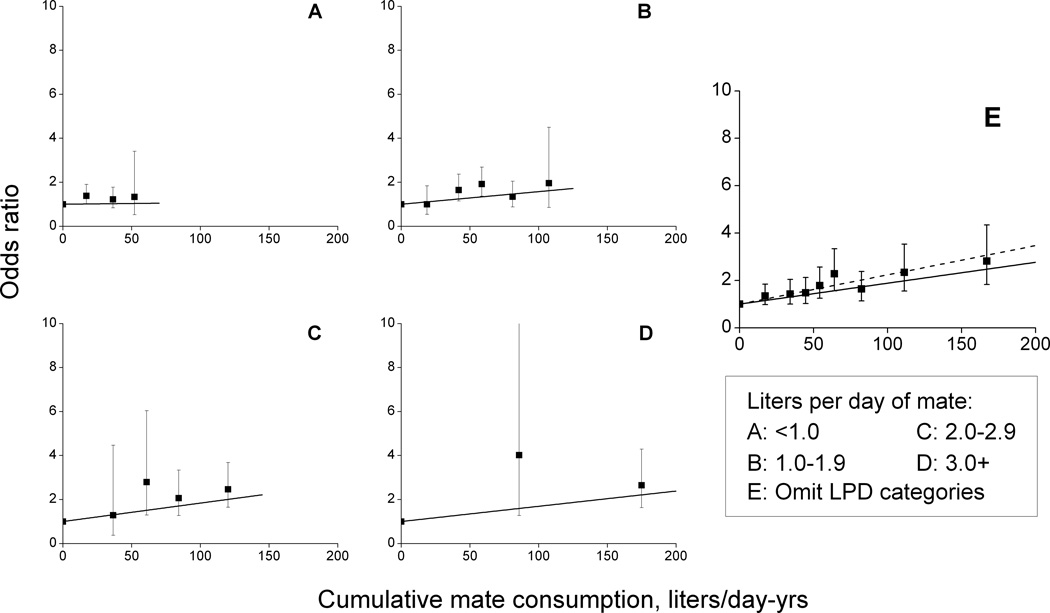

We first examined LPD as a modifier of the LPDY association, i.e., whether the strength of association varied by intensity or alternatively whether for a fixed total LPDY low intensity for long duration resulted in greater, equal or lesser risk compared to high intensity for short duration. For joint categories of LPDY and LPD, ORs relative to never drinkers increased with LPDY within each LPD category (Figure 1, panels A–D, solid symbol), with trends consistent with linearity, except for 1.0–1.9 LPD (P=0.03). EOR/LPDY estimates for the four LPD categories were 0.001, 0.006, 0.008 and 0.007, respectively, revealing minimal variation in strength of association (test of homogeneity, P=0.35). Across the full range of continuous LPDY, a linear relationship described maté-related ORs (Figure 1, panel E) (P=0.76 for the test of no departure from linearity). The EOR/LPDY estimate with 95% CI was 0.009 (0.005,0.014). After omitting low intensity drinkers (LPD<0.5), model fit improved slightly (dash line) and the EOR/LPDY estimate was 0.012 (0.007,0.020).

Figure 1.

Odds ratios (OR) for cumulative maté consumption in liters/day-year (LPDY) within categories of mean daily intake in liters/day (LPD) (panels: A <1.0; B 1.0–1.9; C 2.0–2.9; D: ≥3.0) and overall (panel E), and fitted linear models for the excess OR using all data (solid line) or restricted data (never and ≥0.5 liters/day maté drinkers). Pooled data from the Uruguay Case-Control Study and the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) Multinational Case-Control Study.

3.4 Effect modification of the association of cumulative maté use

There was significant variation of EOR/LPDY estimates with temperature, years since maté cessation and age at first consumption (P<0.01) (Table 3). The EOR/LPDY estimates increased with temperature, 0.004 (−0.002,0.013), 0.007 (0.003,0.013) and 0.016 (0.009,0.027) for warm, hot and very hot consumers, respectively. In warm maté consumers, ORs by LPDY categories increased monotonically; however, the test of no trend did not reject (P=0.14). EOR/LPDY estimates varied with years since cessation, 0.009 (0.004,0.015), 0.020 (0.006,0.044) and 0.005 (−0.003,0.022) for 0, 1–4 and ≥5 years since cessation, respectively, but was not monotonic. Since prodromal symptoms may have influenced consumption, we applied a post hoc categorization <5 and ≥5 years since cessation and found that the EOR/LPDY estimate was greater in current and recent former drinkers, 0.009 (0.004,0.015) than in long-term former drinkers 0.005 (−0.003,0.021), with the difference nearly significant (P=0.08). Subjects ages <12 years at first maté consumption exhibited the strongest association, 0.012 (0.006,0.020), compared with older initiators, 0.005 (0.001,0.011) at 12–16 years and 0.008 (0.001,0.017) at ≥17 years (P=0.01).

Table 3.

Odds ratios (OR) by categories of cumulative liter/day-years (LPDY) of mate consumption relative to never-drinkers and excess OR per LPDY (EOR/LPDY) estimates from a linear model within levels of potential effect modifiersa. Pooled data from the Uruguay and IARC Multinational Case-Control Studies.

| ORs by liters/day-years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modifier | 1–29 | 30–49 | 50–69 | 70–99 | ≥100 | EOR/LPDYb | 95% CIc | Pd |

| Temperature | ||||||||

| Warm | 0.88 | 1.16 | 1.79 | 2.11 | 2.15 | 0.004 | (−0.002,0.013) | <0.01 |

| Hot | 1.56 | 1.52 | 1.94 | 1.46 | 2.06 | 0.007 | (0.003,0.013) | |

| Very hot | 0.88 | 1.56 | 2.58 | 2.21 | 4.56 | 0.016 | (0.009,0.027) | |

| Years since last mate | ||||||||

| 0 | 1.27 | 1.41 | 1.98 | 1.74 | 2.45 | 0.009 | (0.004,0.015) | <0.01 |

| 1–4 | 2.58 | 1.76 | 2.92 | 1.18 | 5.07 | 0.020 | (0.006,0.044) | |

| ≥5 | 1.46 | 2.07 | 2.00 | 0.31 | 2.78 | 0.005 | (−0.003,0.022) | |

| Age 1st mate | ||||||||

| <12 | 1.43 | 1.68 | 2.28 | 1.91 | 3.19 | 0.012 | (0.006,0.020) | <0.01 |

| 12–16 | 1.20 | 1.56 | 1.78 | 1.13 | 1.96 | 0.005 | (0.001,0.011) | |

| ≥17 | 1.39 | 1.14 | 2.03 | 2.12 | 2.47 | 0.008 | (0.001,0.017) | |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Males | 1.29 | 1.42 | 1.96 | 1.48 | 2.24 | 0.007 | (0.003,0.013) | 0.29 |

| Females | 1.52 | 1.55 | 2.09 | 2.25 | 3.64 | 0.013 | (0.004,0.032) | |

| Attained age | ||||||||

| <65 | 1.20 | 1.64 | 2.17 | 2.13 | 2.92 | 0.015 | (0.007,0.029) | 0.14 |

| 65–74 | 2.11 | 2.13 | 2.86 | 1.72 | 2.98 | 0.006 | (0.001,0.015) | |

| ≥75 | 1.20 | 0.69 | 1.10 | 0.97 | 1.84 | 0.006 | (0.001,0.016) | |

| Smoking status | ||||||||

| Never | 1.18 | 1.14 | 1.73 | 2.27 | 4.03 | 0.018 | (0.007,0.038) | 0.02 |

| Former | 1.69 | 1.15 | 2.17 | 1.80 | 3.03 | 0.009 | (0.002,0.022) | |

| Current | 1.32 | 1.78 | 1.96 | 1.27 | 1.69 | 0.003 | (−0.001,0.009) | |

| Tobacco type (males only) | ||||||||

| Never | 0.89 | 0.35 | 1.36 | 2.06 | 2.44 | 0.011 | (0.000,0.041) | <0.01 |

| Blond-only | 1.17 | 1.36 | 1.96 | 1.05 | 0.93 | −0.002 | (--e ,0.005) | |

| Mixed/black-only | 2.18 | 2.54 | 3.28 | 2.80 | 4.93 | 0.014 | (0.005,0.032) | |

| Alcohol status | ||||||||

| Never | 1.74 | 1.92 | 2.57 | 2.68 | 3.89 | 0.017 | (0.006,0.037) | 0.12 |

| Former | 1.08 | 1.30 | 1.29 | 0.95 | 1.95 | 0.004 | (−0.001,0.014) | |

| Current | 1.26 | 1.27 | 2.03 | 1.52 | 2.22 | 0.008 | (0.002,0.018) | |

ORs adjusted for study, cigarette smoking (pack-years, cigarettes/day), alcohol consumption (drink-years, ml ethanol/day), age, sex, education and for Uruguay income and urban/rural residence. Models included a sex-specific fixed offset variable to account for differential effects of mate consumption in urban, never alcohol consumers for the Uruguay data. ORs relative to never mate consumers.

Estimated EOR/liter/day-year based on linear odds ratios for liter/day-years relative to never-drinkers within levels of a modifier: OR(d) = 1 + Σi γi di for the ith level, where di and γi are the cumulative LPDY and EOR/LPDY within the ith level, respectively. For all data, the EOR/LPDY estimate with 95% confidence interval was 0.009 (0.005, 0.14).

Likelihood-based 95 percent confidence interval (CI) for the EOR/LPDY.

P-value for test of homogeneity of EOR/LPDY across levels of the modifier.

Not estimable.

The LPDY association was statistically homogeneous by sex (P=0.29), although category-specific ORs by LPDY were larger in females and EOR/LPDY estimates were 0.013 (0.004,0.032) in females and 0.007 (0.003,0.013) in males. For attained ages <65, 65–74 and ≥ 75 years, EOR/LPDY estimates were 0.015 (0.007,0.029), 0.006 (0.001,0.015) and 0.006 (0.001,0.016), respectively, suggesting an enhanced trend at younger ages (P=0.14). A post hoc categorization of ages <65 and ≥65 years resulted in EOR/LPDY estimates of 0.015 (0.005,0.033) and 0.006 (0.001,0.013), which differed significantly (P=0.05).

Modification of the EOR/LPDY was inconsistent for smoking related variables. ORs by LPDY varied by cigarette smoking status (P=0.02), with the strongest association in never smokers, 0.018 (0.007,0.038), decreasing in former, 0.009 (0.002,0.022), and current smokers, 0.003 (−0.001,0.009). However, ORs at higher LPDY levels drove the variation, as ORs for <70 LPDY were similar (Table 3). For <70 LPDY, the EOR/LPDY estimates for never, former and current smokers were 0.006 (−0.004,0.023), 0.007 (−0.003,0.026) and 0.018 (0.005,0.042), respectively, and homogeneous (P=0.32). Tobacco type was a significant effect modifier, with trends increased in never smokers and in mixed/black-only tobacco users, but not in blond tobacco users (P<0.01). However, for <70 LPDY, ORs for blond-only tobacco smokers were elevated and the EOR/LPDY estimate was 0.013 (0.001,0.035), consistent with estimates for never and mixed/black-only tobacco users (P=0.22).

Category-specific ORs by LPDY were highest in never alcohol drinkers, with EOR/LPDY estimates for never, former and current alcohol drinkers of 0.017 (0.006,0.037), 0.004 (−0.001,0.014) and 0.008 (0.002,0.018), respectively. However, the test of homogeneity of trends was not rejected (P=0.12). A post hoc evaluation of EOR/LPDY estimates for never and ever alcohol drinkers rejected homogeneity (P=0.04).

3.5 Consistency of results across studies

ORs by LPDY were consistent with linearity among exposed in the Uruguay Study (P=0.91) and among all subjects in the IARC Study (P=0.11), with EOR/LPDY estimates of 0.003 (−0.001,0.009) and 0.015 (0.008,0.025), respectively. Homogeneity of EOR/LPDY estimates was rejected (P=0.01) (Supplemental Table B2).

Adjusted for study differences, variations in EOR/LPDY patterns across the potential modifiers were consistent for the studies, and tests of homogeneity of effect modification did not reject, except for age at first maté consumption (P<0.01). The EOR/LPDY estimate was largest for ages <12 years in the Uruguay Study and for ages 12–16 years in the IARC Study (Supplemental Table B2.)

Discussion

This analysis represents the first detailed assessment of the exposure-response association for maté consumption and ESCC risk and of the potential modifying effects for a broad range factors. In particular, we evaluated: (i) the relationship of ESCC and cumulative maté consumption; (ii) the influence of maté consumption intensity on the strength of association; and (iii) the impact of potential effect modifiers. The pooled results were consistent with the constituent studies (4, 5, 18–22), with marginal ORs increasing significantly with ever use, cumulative intake and intensity. Our pooled results extended prior analyses to demonstrate that ORs increased linearly with LPDY (Figure 1), rising to 2.0-fold for ≥100 LPDY consumers. Moreover, maté intensity did not alter the linear association with LPDY, suggesting that the main determinant of risk was cumulative intake and that for a given intake, higher intensity consumption for shorter duration or lower intensity consumption for longer duration resulted in comparable ORs. We could not however rule out an enhanced association in low (<0.5 LPD) intensity drinkers, although this enhancement may have reflected differential misclassification, with lower maté intensity cases underreporting cumulative intake.

Epidemiologic studies have linked ESCC to repeated ingestion of high temperature liquids, such as tea, coffee and maté (7, 15, 25–27), implicating thermal injury as a carcinogen. Although estimates of the association have varied, increased ORs with beverage temperature are observed in many countries and across diverse beverage types (15). Intra-esophageal temperatures are sensitive to initial fluid temperature, time between sips and sip volume, suggesting substantial inherent variability (28, 29). Moreover, temperatures were self-assessed, further increasing misclassification. In spite of the substantial misclassification, the strength of association in the current analysis increased with temperature; EOR/LPDY estimates were 0.004, 0.007 and 0.016 for consumption at warm, hot and very hot temperatures, respectively (Table 3), consistent with thermal injury damaging the epithelial lining of the esophagus and thereby directly affecting risk or enabling other factors. Experimental animal studies involving high temperature liquids support this pattern (30–32). Nonetheless, risks for warm maté drinkers remain uncertain. While category-specific ORs increased monotonically, the test of no trend was not rejected (P=0.14).

Although there have been relatively few studies and results to date are not conclusive, studies have associated maté consumption with diverse cancer sites, including oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, lung, kidney and bladder (4–12, 16). Thus, the etiology of ESCC may potentially involve maté-associated non-thermal factors. Attention has focused on PAHs, in particular benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), a possible production-acquired contaminate (16, 33), which IARC has classified as a human carcinogen (34, 35). Since cigarette smoke contains PAHs, residual confounding may have influenced maté-related ORs (2, 8). However, substantial confounding in the current analysis seems unlikely, since among users the Pearson correlation between liters/day of maté and cigarettes/day was small (0.11 in controls), urinary measurements of 1-hydroxypyrene glucuronide, a stable PAH metabolite, correlated positively with maté consumption (14) and, importantly, we observed significant trends in ORs with LPDY in never smokers and in smokers after extensive smoking adjustment.

Conclusions were not definitive regarding modification by other maté-related variables. Cessation of maté drinking significantly modified EOR/LPDY estimates (P<0.01); however, the largest estimate occurred in recent (1–4 years) former drinkers (=0.020), with lower estimates in both current (=0.009) and long-term (≥5 years) former drinkers (=0.005) (Table 3). Because prodromal symptoms may have influenced responses, we recalculated EOR/LPDY for <5 and ≥5 years cessation and found estimates of 0.009 and 0.006, respectively, indicating reduced maté effects with increased cessation (P<0.01). This result agreed with two previous studies that found higher ORs in former compared to current drinkers (4, 7), but not another which found monotonically decreasing ORs with cessation (13). Our analyses were necessarily limited due to few long-term quitters (74 cases and 167 controls). Younger ages at initiation increased the strength of the LPDY association; however, interpretation was problematic since variations in EOR/LPDY estimates were inconsistent across studies (P<0.01) (Table B2).

Cumulative maté effects were statistically homogeneous by sex for each study and the pooled data; however, category-specific ORs with LPDY and EOR/LPDY estimates were greater in females. These results corresponded to previous findings for the IARC Study (4). Although not significant, consistency in the enhanced effects in females suggested the need for further evaluation in other study populations.

No definitive conclusions were possible for the roles of age, cigarette smoking and alcohol as effect modifiers. The largest EOR/LPDY estimate occurred for ages <65 years in each study and in the pooled data (Table C2); however, homogeneity of EOR/LPDY estimates was not rejected (P=0.14). Only under post hoc evaluation did EOR/LPDY estimates vary significantly for ages <65 years. In the pooled data, smoking status and type of tobacco were significant modifiers of the maté association, but higher LPDY consumers drove results. For <70 LPDY (representing 83% of controls), EOR/LPDY estimates were 0.006, 0.007 and 0.018 for never, former and current smokers, respectively, and homogeneous (P=0.32), which was concordant with a previous result (13). Estimates were −0.002, 0.013, 0.020 in never smokers, blond-only, mixed/black-only tobacco users (P=0.22). Finally, while ORs and the EOR/LPDY estimate were greatest in those who never consumed alcohol and homogeneity was not statistically rejected (P=0.12), the differential EOR/LPDY estimates occurred only in the IARC Study (Table 2).

Initial analyses revealed that ORs by LPDY increased linearly in both the IARC and Uruguay datasets, with linearity in the latter dataset occurring only in maté consumers. While maté-related ORs could vary in populations due to different methods of preparation and consumption, trends with consumption should be roughly comparable. Exploratory analysis of the Uruguay dataset identified a small subgroup of urban residents who never consumed alcohol (4 cases and 114 controls) with significant ORs by ever consumed maté of 4.2 for males and 13.8 for females. The inclusion of a fixed offset eliminated non-linearity in the Uruguay data. An alternative approach could have specified a non-linear relationship for ORs with LPDY in the Uruguay data, and derived an offset for the IARC data that induced a curvilinear pattern to mimic the Uruguay data. We did not apply this approach, since it increases model complexity and since linearity typically represents the preferred first order approximation (Occam’s Razor). A second alternative could have omitted the offset and used a combined linear relationship for the IARC data and a curvilinear relationship for the Uruguay data. Under this approach, the inference in Table 3 was largely unchanged, except EOR/LPDY variations were not significant for attained age (P=0.87 and P=0.63 for post hoc categories of ages <65 and ≥65) but were significant for alcohol status (P<0.01) (not shown).

In summary, our results confirmed the hypothesis that drinking maté increases risk of ESCC, with ORs consistent with a linear relationship in cumulative intake. Moreover, the strength of association with cumulative intake was not influenced by consumption intensity, so that greater daily consumption for a shorter duration or less daily consumption for a longer duration resulted in comparable ORs. The increased ORs also occurred at all beverage temperatures, but were greater with higher mate temperatures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support:

A grant from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), Lyon, France supported the Uruguay Study and E. De Stefani, H. Deneo-Pellegrini, A. L. Ronco and G. Acosta (IARC/CRA ECE/98/17). X. Castellsagué, C Victora and E. De Stefani, the IARC Study and its components were supported with grants from IARC to Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (Spain) (FIS 97/0662), Fondo para la Investigacion Cientifica y Tecnologica (Argentina), Institut Municipal d’Investigacio Medica (Barcelona), Fundacao de Amparo a Pesquisa no Estado de Sao Paulo (01/01768-2), and from the European Commission (IC18-CT97-0222), the Comision Honoraria de Lucha contra el Cancer (Montevideo, Uruguay)(5471-066), the International Union Against Cancer, the International Cancer Research Data Bank Program of the National Cancer Institute and the NIH (USA) (N01-CO-65341). J. H. Lubin, C. C. Abnet, B. I. and S. M. Dawsey were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

All co-authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with the research topics covered in this manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Volume 51 Coffee, Tea, Mate, methylxanthines and methylglyoxal. Lyon, France: IARC; 1991. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1991) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heck CI, De Mejia E. Yerba Mate tea (Ilex paraguariensis): A comprehensive review on chemistry, health implications, and technological considerations. J Food Sci. 2007;72(9):R138–R151. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bracesco N, Sanchez A, Contreras V, Menini T, Gugliucci A. Recent advances on Ilex paraguariensis research: Minireview. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136(3):378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castellsague X, Munoz N, De Stefani E, Victora CG, Castelletto R, Rolon PA. Influence of mate drinking, hot beverages and diet on esophageal cancer risk in South America. Int J Cancer. 2000;88(4):658–664. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20001115)88:4<658::aid-ijc22>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Stefani E, Moore M, Aune D, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Ronco AL, Boffetta P, et al. Mate consumption and risk of cancer: a multi-site case-control study in Uruguay. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(4):1089–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Stefani E, Fierro L, Mendilaharsu M, Ronco A, Larrinaga MT, Balbi JC, et al. Meat intake, 'mate' drinking and renal cell cancer in Uruguay: a case-control study. Br J Cancer. 1998;78(9):1239–1243. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Szymanska K, Matos E, Hung RJ, Wuensch-Filho V, Eluf-Neto J, Menezes A, et al. Drinking of mate and the risk of cancers of the upper aerodigestive tract in Latin America: a case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(11):1799–1806. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9606-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Stefani E, Boffetta P, Deneo-Pellegrini H, Correa P, Ronco AL, Brennan P, et al. Non-alcoholic beverages and risk of bladder cancer in Uruguay. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates MN, Hopenhayn C, Rey OA, Moore LE. Bladder cancer and mate consumption in Argentina: A case-control study. Cancer Letters. 2007;246(1–2) doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Stefani E, Fierro L, Correa P, Fontham E, Ronco A, Larrinaga M, et al. Mate drinking and risk of lung cancer in males: A case-control study from Uruguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1996;5(7):515–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasanayake AP, Silverman AJ, Warnakulasuriya S. Mate drinking and oral and oro-pharyngeal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncology. 2010;46(2):82–86. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldenberg D, Golz A, Joachims HZ. The beverage mate: A risk factor for cancer of the head and neck. Head and Neck-Journal for the Sciences and Specialties of the Head and Neck. 2003;25(7):595–601. doi: 10.1002/hed.10288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sewram V, De Stefani E, Brennan P, Boffetta P. Mate consumption and the risk of squamous cell esophageal cancer in Uruguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(6):508–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagundes RB, Abnet CC, Strickland PT, Kamangar F, Roth MJ, Taylor PR, et al. Higher urine 1-hydroxy pyrene glucuronide (1-OHPG) is associated with tobacco smoke exposure and drinking mate in healthy subjects from Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Islami F, Boffetta P, Ren J-S, Pedoeim L, Khatib D, Kamangar F. High-temperature beverages and foods and esophageal cancer risk-A systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2009;125(3):491–524. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamangar F, Schantz MM, Abnet CC, Fagundes RB, Dawsey SM. High levels of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in mate drinks. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(5):1262–1268. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamangar F, Chow WH, Abnet CC, Dawsey SM. Environmental causes of esophageal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38(1):27–57. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellsague X, Munoz N, De Stefani E, Victora CG, Castelletto R, Rolon PA, et al. Independent and joint effects of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on the risk of esophageal cancer in men and women. Int J Cancer. 1999;82(5):657–664. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990827)82:5<657::aid-ijc7>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castelletto R, Castellsague X, Munoz N, Iscovich J, Chopita N, Jmelnitsky A. Alcohol, tobacco, diet, mate drinking, and esophageal cancer in Argentina. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3(7):557–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolon PA, Castellsague X, Benz M, Munoz N. Hot and cold mate drinking and esophageal cancer in Paraguay. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1995;4(6):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Victora CG, Munoz N, Day NE, Barcelos LB, Peccin DA, Braga NM. Hot beverages and esophageal cancer in southern Brazil - a case-control study. Int J Cancer. 1987;39(6):710–716. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910390610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Stefani E, Munoz N, Esteve J, Vasallo A, Victora CG, Teuchmann S. Mate drinking, alcohol, tobacco, diet, and esophageal cancer in Uruguay. Cancer Res. 1990;50(2):426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslow NE, Day NE. The analysis of case-control studies. Vol. I. Lyon: IARC; 1980. Statistical methods in cancer research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preston DL, Lubin JH, Pierce DA, McConney ME. Epicure User's Guide. Seattle, Washington, USA: HiroSoft International Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gao Y, Hu N, Han XY, Ding T, Giffen C, Goldstein AM, et al. Risk factors for esophageal and gastric cancers in Shanxi Province, China: A case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;35(6):E91–E99. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J, Zeng R, Cao W, Luo R, Chen J, Lin Y. Hot beverage and food intake and esophageal cancer in southern China. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(9):2189–2192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islami F, Pourshams A, Nasrollahzadeh D, Kamangar F, Fahimi S, Shakeri R, et al. Tea drinking habits and oesophageal cancer in a high risk area in northern Iran: population based case-control study. Br Med J. 2009;338 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dejong UW, Day NE, Mounierk PL, Haguenau JP. Relationship between ingestion of hot coffee and intraesophageal temperature. Gut. 1972;13(1):24–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.13.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Candreva EC, Keszenman DJ, Barrios E, Gelos U, Nunes E. Mutagenicity induced by hyperthermia, hot mate infusion, and hot caffeine in saccharomyces-cerevisiae. Cancer Res. 1993;53(23):5750–5753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yioris N, Ivankovic S, Lehnert T. Effect of thermal-injury and oral-administration of N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine on the development of esophageal tumors in Wistar rats. Oncology. 1984;41(1):36–38. doi: 10.1159/000225787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li ZG, Shimada Y, Sato F, Maeda M, Itami A, Kaganoi J, et al. Promotion effects of hot water on N-nitrosomethylbenzylamine-induced esophageal tumorigenesis in F344 rats. Oncology Reports. 2003;10(2):421–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tobey NA, Sikka D, Marten E, Caymaz-Bor C, Hosseini SS, Orlando RC. Effect of heat stress on rabbit esophageal epithelium. Am J Physiology-Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1999;276(6):G1322–G1330. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.6.G1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vieira MA, Maraschin M, Rovaris AA, de Mello Castanho Amboni RD, Pagliosa CM, Mendonca Xavier JJ, et al. Occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons throughout the processing stages of erva-mate (Ilex paraguariensis) Food Addit Contaminants Part A-Chem Anal Control Exposure Risk Assessment. 2010;27(6):776–782. doi: 10.1080/19440041003587310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cogliano VJ, Baan R, Straif K. Updating IARC's Carcinogenicity Assessment of Benzene. Am J Ind Med. 2011;54(2):165–167. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Volume 92 Some Non-heterocyclic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Some Related Exposures. Lyon, France: IARC; 2010. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans(2010) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.