Abstract

PURPOSE

Both 131I- and 123I-labeled meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) have been widely used in the clinic for targeted imaging of the norepinephrine transporter (NET). The human NET (hNET) gene has been imaged successfully with 124I-MIBG PET at time points of >24 h post-injection. [18F]Fluorine-labeled MIBG analogs may be ideal to image hNET expression at time points of <8 h post-injection. We developed improved methods for the synthesis of known MIBG analogs, [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG and evaluated them in hNET reporter gene-transduced C6 rat glioma cells and xenografts.

METHODS

[18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were synthesized manually using a 3-step synthetic scheme. Wild-type and hNET reporter gene-transduced C6 rat glioma cells and xenografts were used to comparatively evaluate the 18F-labeled analogs with 123I/[124I]MIBG.

RESULTS

The fluorination efficacy on benzonitrile was predominantly determined by the position of the trimethylammonium group. The para-isomer afforded higher yields (75±7%) than meta-isomer (21±5%). The reaction of [18F]fluorobenzylamine with 1H–pyrazole-1-carboximidamide was more efficient than with 2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea. The overall radiochemical yields (decay-corrected) were 11±2% (n = 12) for [18F]MFBG, and 41±12% (n = 5) for [18F]PFBG, respectively. The specific uptakes of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were similar in C6-hNET cells, but 4-fold less than that of 123I/[124I]MIBG. However, in vivo [18F]MFBG accumulation in C6-hNET tumors was 1.6-fold higher than that of [18F]PFBG at 1 h p.i., whereas their uptakes were similar at 4 h. Despite [18F]MFBG having a 2.8-fold lower affinity to hNET and approximately 4-fold lower cell uptake in vitro compared to 123I/[124I]MIBG, PET imaging demonstrated that [18F]MFBG was able to visualize C6-hNET xenografts better than [124I]MIBG. Biodistribution studies showed [18F]MFBG and 123I-MIBG had a similar tumor accumulation, which was lower than that of no-carrier-added [124I]MIBG; but [18F]MFBG showed a significantly more rapid body clearance and lower uptake in most non-targeting organs.

CONCLUSION

[18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were synthesized in reasonable radiochemical yields under milder conditions. [18F]MFBG is a better PET ligand to image hNET expression in vivo at 1 to 4 h post injection, than both [18F]PFBG and 123I/[124I]MIBG.

Keywords: [18F]MFBG, [18F]PFBG, hNET reporter gene, PET imaging

INTRODUCTION

The human norepinephrine transporter (hNET) is a transmembrane protein (617 amino acids) that functions as a rapid norepinephrine reuptake system located at or near presynaptic terminals and terminates noradrenergic signaling by rapid reuptake of neuronally released norepinephrine [1]. The in vivo expression of NET is almost exclusively restricted to the central and peripheral sympathetic nervous system [2]. Thus, hNET has recently been suggested as a human reporter gene because of its localized expression in the body [3, 4].

An additional advantage of hNET as a human reporter gene is the availability and established efficacy of several different radiotracers for clinical imaging of endogenous hNET expression. They include different radioiodine- and radiobromine-labeled benzylguanidine analogs. For example, meta-iodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) is a metabolically stable analog of norepinephrine, and 131I-labeled MIBG has been widely used for targeted imaging using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or planar imaging and treatment of hNET expressing cancer for several decades [5]. Although MIBG labeled with 131I (t1/2 = 8.04 d; Eβ = 606 keV, 89%; Eγ = 364 keV, 81%) is still used for targeted radiotherapy [5, 6], MIBG labeled with 123I (t1/2 = 13.3 h; Eγ = 159 keV, 89%) has largely replaced [131I]MIBG for diagnostic studies [7]. However, both [123I]MIBG and [131I]MIBG have several disadvantages with respect to diagnostic imaging [8, 9]. These include: 1) semi-quantitative measures of 123/131I-MIBG accumulation; 2) inability to image small lesions due to limited spatial-resolution; and 3) residual radioactivity due to the long physical half-life that limits daily imaging protocols to assess treatment response, even with [123I]MIBG.

Efforts to develop improved radiolabeled norepinephrine analogs continue, with a particular focus on MIBG analogs labeled with a positron emitter. They include 124I- (t1/2 = 4.18 d; β+, 23%, Emax(β+) = 0.60 MeV), 76Br- (t1/2 = 16.1 h; β+, 57%, Emax (β+) = 0.61 MeV), 18F- (t1/2 = 110 min; β+, 98%, Emax(β+) = 0.63 MeV) and 11C- (t1/2 = 20.4 min; β+, 99%, Emax(β+) = 0.96 MeV) [10] labeled analogs. However, [124I]MIBG [4, 11] and [76Br]MBBG [12] require imaging at a late time point in order to achieve optimal image contrast. Our previous kinetic studies demonstrated that the optimal time for 124I-MIBG PET imaging is between 48 and 72 h post injection (p.i.) when tissue background radioactivity is low [4].

Several 18F-labeled benzylguanidine analogs, such as [18F]PFBG [13–15], [18F]MFBG [13], [18F]FIBG [16, 17], [18F]FPBG [18], [18F]4-FMHPG [19], and LMI1195 [20], have already been developed for imaging hNET expression in cancer and for imaging cardiac dysfunction. Many of these ligands were designed to have a logP value similar to that of MIBG, with the objective of achieving an in vitro uptake and in vivo distribution similar to that of MIBG. Specific accumulation of these agents in hNET-expressing SK-K-SH neuroblastoma cells has been demonstrated. However, none of the above radioligands were evaluated for imaging hNET expression in xenografts, nor was the optimal time for imaging determined (in order to achieve maximum target-to-background ratios). Furthermore, none of these radioligands have ever been tested or utilized for PET imaging of hNET reporter gene transduced cells or xenografts.

The focus of the study reported here was to determine whether a [18F]fluorine-labeled MIBG analog could be synthesized with a reasonable yield for clinical imaging, and whether the resultant PET images of hNET expression would be optimal within 1–4 hours after administration of the radiotracer. To further explore the use of [18F]fluorine-labeled MIBG analogs in the hNET human reporter gene system, [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were tested and compared to 123I/[124I]MIBG, using our established C6-hNET cells and xenografts [4]. We sought to: 1) optimize a synthetic approach for preparing useful amounts of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG, 2) evaluate these radioligands in C6 wild-type rat glioma cells (WT) and hNET stably transduced C6 cells and in corresponding xenografts, and 3) compare [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG with [124I]MIBG PET of hNET expression in the animals, bearing C6-hNET and C6-WT xenografts.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

General

All chemicals were obtained from commercial sources and were used without further purification. 3-Cyano-N,N,N-trimethylbenzenaminium triflate (precursor of [18F]MFBG), 4-Cyano-N,N,N-trimethylbenzenaminium triflate (precursor of [18F]PFBG), PIBG and MFBG were supplied by Nanocs (New York, NY, USA). The no-carrier-added [124I]MIBG (> 12 GBq/µmol) was synthesized using a published protocol [21]. 123I-MIBG (~0.31 GBq/µmol), synthesized by an exchange radioiodination method, was obtained from Nuclear Diagnostics Products (Rockaway, NJ). The C6-hNET cell line was generated as previously described [4]. Radioactivity was quantified with a WIZARD™ 3” 1480 γ-counter (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) or a dose calibrator (CAPINTEC ®CRC-30BC, Ramsey, NJ).

Synthesis of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG

[18F]MFBG was synthesized manually with a procedure (Figure 1) that was modified from previously published methods [13, 22]. Dry tetrabutylammonium [18F]fluoride (TBA[18F]F) was prepared with azeotropic evaporation under a mild flow of nitrogen [23]. A solution of 3-cyano-N,N,N-trimethylbenzenaminium triflate (5–10 mg, Nanocs, New York, NY, USA) in 0.5 mL anhydrous acetonitrile (MeCN) was added to the TBA[18F]F, and the vial was heated at 90 °C for 15 min in a microwave system. After dilution with 5 mL H2O, the crude 3-[18F]fluorobenzonitrile was trapped on a HLB cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA). The cartridge was dried with a mild flow of nitrogen for 3 min, and then its outlet was connected to the inlet of an anhydrous MgSO4 column. The dry 3-[18F]fluorobenzonitrile was eluted from the cartridge using two volumes of 3 mL anhydrous ether. Three hundred µL of LiAlH4 ether solution (1 M) was slowly added to the ether solution of 3-[18F]fluorobenzonitrile, and the reaction mixture was left at room temperature for 5 min and then quenched with 1 mL of H2O and 0.3 mL of 1 N NaOH. After the ethereal phase containing 3-[18F]fluorobenzylamine was transferred to another vial, the aqueous phase was again extracted with 2 mL of ether. After evaporating the ether from the combined ethereal solution, 1H–pyrazole-1-carboximidamide (10 mg in 0.5 mL H2O) and triethylamine (6 µL) were added to the residue. The mixture was heated at 100 °C for 20 min. Pure [18F]MFBG was obtained by HPLC purification (Phenomenex® Luna C18(2) column: 250 mm × 10.0 mm, 5 m, 100 Å; UV detector: 262 nm; flow rate: 5 mL/min; mobile phase: 0.1% TFA (trifluoroacetic acid) in water and MeCN; gradient: 0–1 min, 2%–10% MeCN, 1–16 min, 10%–20% MeCN, 16–18.5 min, 20%–100% MeCN, 24.5 min, 100% MeCN, 25 min, 2% MeCN). After the solvents were removed with a rotary evaporator, [18F]MFBG was re-dissolved in saline for further experiments. An aliquot of [18F]MFBG was characterized with analytical HPLC (Alltima HP C18 column: 250 mm × 4.6 mm; flow rate: 1 mL/min; mobile phase: 0.1% TFA in each water and MeCN; gradient: 0–2 min, 2–10% MeCN, 14 min, 10% MeCN, 14–16.5 min, 10–100% MeCN, 24 min, 100% MeCN, 25 min, 2% MeCN). [18F]PFBG was synthesized following the same procedure used for [18F]MFBG synthesis but using 4-cyano-N,N,N-trimethylbenzenaminium triflate as the starting material. Specific activity of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG was determined with UPLC-MS after sufficient decay of radioactivity.

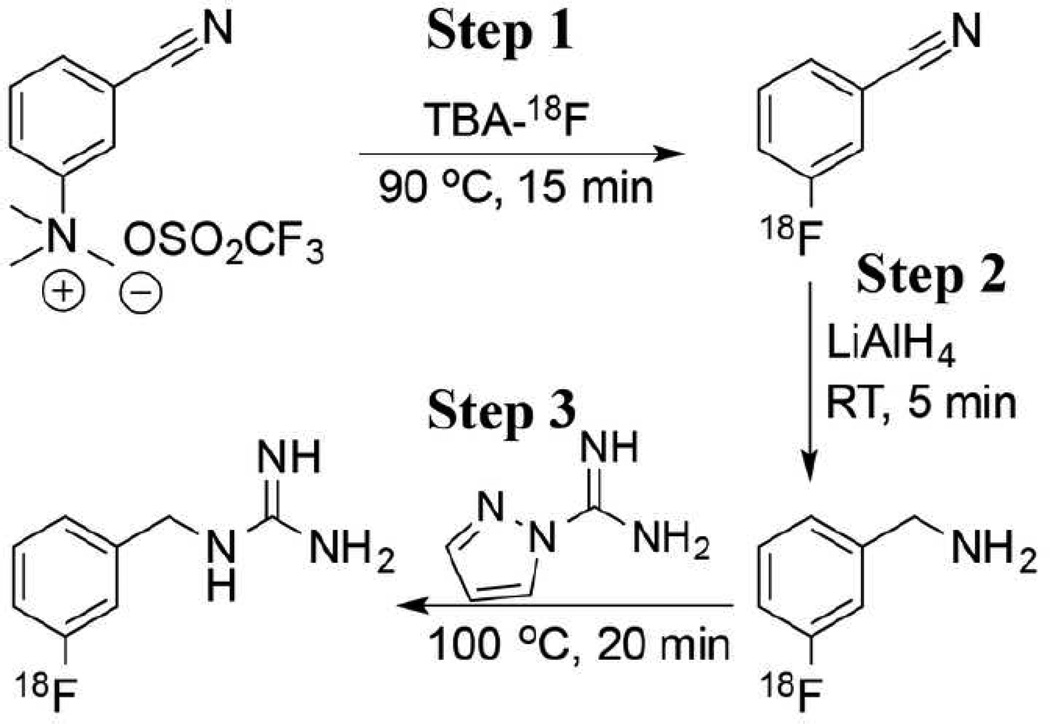

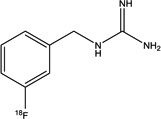

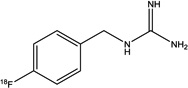

Figure 1.

Synthetic scheme for radiolabeling benzylguanidine analogs ([18F]MFBG).

Lipophilicity and plasma protein binding of [18F]MFBG, [18F]PFBG and 123I-MIBG

Lipophilicity

The distribution coefficients of [18F]MFBG, [18F]PFBG and 123I-MIBG were determined by partitioning them between 1-octanol and phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) (v/v = 1/1). The 1-octanol/PBS mixture was pre-equilibrated for 24 h. Ten µL of radioligand solution (123I-MIBG: ~3.7 kBq; [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG: ~11.1 kBq) was added into the mixture of 1-octanol/PBS (200 µL/190 µL). Samples, in triplicate, were vigorously shaken for 2 h at room temperature to reach equilibrium. Then the samples were centrifuged (5 min at 2,000 rpm) and radioactivity in 50 µL aliquots from each of the aqueous and the organic phase was measured with the γ-counter. The distribution coefficient (logD) was calculated using the formula: logD = log10 (counts in octanol layer / counts in PBS layer).

Plasma protein binding

Ten µL of radioligand solution (123I-MIBG: ~3.7 kBq; [18F]MFBG: ~7.4 kBq) was added to 190 µL of human or mouse plasma. Samples, in triplicate, were gently shaken at 37 °C for 0.5 h. Then the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 9,000 rpm in 0.5 mL ultrafiltration tubes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The radioactivity in 20 µL of the plasma before filtration (to determine total added radioactivity) and 20 µl of ultrafiltrate (to determine the activity that was not bound to plasma protein) were measured in a γ-counter.

In vitro uptake in hNET-transduced and wild-type C6 cells

C6-hNET and C6-WT cells were cultured in DMEM HG cell medium. Cells (1.0 × 106 in a total volume of 1.0 mL cell medium) in triplicate were mixed with [18F]MFBG, [18F]PFBG (approximately 11.1 kBq of each), 123I-MIBG, or [124I]MIBG (approximately 3.7 kBq) and the mixtures were gently shaken at 37 °C for 2 h. The cells were isolated by rapid filtration through glass microfiber filters (Cat. No.: FP-100, Brandel, Gaithersburg, MD) and washed with 3 × 2 mL of ice-cold tris-buffered saline (pH 7.4). The radioactivity in the cells was measured with a γ-counter. Nonspecific uptake was determined by co-incubating with 200 µM of MIBG (final concentration).

Competitive inhibition of 123I-MIBG binding by halogenated benzylguanidine analogs

Competitive binding studies were performed with C6-hNET cells using 123I-MIBG and varied concentrations of MIBG, PIBG, PFBG and MFBG. Briefly, triplicate samples containing ~0.5 × 106 cells, ~3.7 kBq of 123I-MIBG and 0.005–50 nmol of MFBG, MIBG, PIBG or PFBG in 0.5 mL cell medium were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h and processed for radioactivity measurement as described above. Radioactivity accumulated in C6-hNET cells was plotted as a function of the concentration of the unlabeled analogs. The IC50 values were estimated using a least squares fitting routine (GraphPad Prism 5, San Diego, CA).

In vivo imaging of hNET transduced and wild-type xenografts

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Utilization Committee of MSKCC. C6-hNET and C6-WT rat glioma cancer cells were suspended in 200 µL of cell culture medium/matrigel (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ) (v/v = 1/1), respectively. Male athymic NCr-nu/nu mice (7 to 9-week old, TACONIC, Albany, NY) were used for subcutaneous implantation. Animals were inoculated with 5 × 106 C6-hNET cells on the right shoulder and 5 × 106 C6-WT cells on the left shoulder. Twenty days after the inoculation, imaging and tissue sampling were performed when the tumor sizes were between 150 and 350 mm3.

PET imaging

[18F]MFBG or [18F]PFBG (3.7 to 11.1 MBq) or [124I]MIBG (5.1 MBq) in 100 to 200 µL saline was injected into a tail vein. PET imaging was performed on an R4 microPET scanner (Concorde Microsystems, Knoxville, TN), with the tumors centered in the field of view, and the animal was under 2% isoflurane anesthesia. PET acquisition time was 10 min for each time point, with an energy window of 350–750 keV and a coincidence-timing window of 6 ns. The calibration factor of the R4 microPET scanner was measured with a mouse-size phantom composed of a cylinder uniformly filled with an aqueous solution of 18F of known activity concentration. Region-of-interest (ROI) analysis of the acquired images was performed using ASIPro software (Siemens, Malvern, PA), and the observed maximum pixel value (%ID/mL) was utilized to diminish partial volume effects of tumor.

Biodistribution of [124I]MIBG, 123I-MIBG and [18F]MFBG

After the radiotracers were administrated via tail vein injection (2.8 MBq of 123I-MIBG, 5.1 MBq of [124I]MIBG, or 5.9 MBq of [18F]MFBG), the animals were sacrificed at 4 h or 24 h (only for [124I]MIBG) post injection. C6 xenografts and other organs of interest were harvested for analysis. The total injected radioactivity per animal was calculated from the measured radioactivity in an aliquot of the injectate. Data were expressed as percent of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

Statistical analysis

Data calculated using Microsoft Excel are expressed as mean ± SD. The Student’s unpaired t-test (GraphPad Prism 5, San Diego, CA) was used to determine statistical significance at the 95% confidence level. Differences with P values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Synthesis of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG

[18F]MFBG was synthesized in three steps within ~3 h, using 3-cyano-N,N,N-trimethylbenzenaminium triflate as the starting material (Fig. 1). All isolated yields presented here are decay-corrected. Starting with 1.85 – 4.62 GBq of [18F]fluoride, the overall radiochemical yield of [18F]MFBG was 11±2% (n = 12), with a specific activity of 18.7±1.1 GBq/µmol (Table 1). In step 1, the yield of 3-[18F]fluorobenzonitrile was 21±5% (n = 15) following fluorination and HLB cartridge purification. In step 2, quantitative reduction of 3-[18F]fluorobenzonitrile to 3-[18F]fluorobenzylamine was achieved by incubation with LiAlH4 for 5 min. The isolated yield of 3-[18F]fluorobenzylamine was 88±3% (n = 15). In step 3, the reaction between 3-[18F]fluorobenzylamine and 1H–pyrazole-1-carboximidamide to generate [18F]MFBG was monitored by analytical HPLC. Conversion to [18F]MFBG was greater than 80% following heating at 100 °C for 20 min (Fig. S1), and the isolated yield of [18F]MFBG was 67±9% (n = 12). [18F]MFBG was characterized by co-injection of standard MFBG (Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Radiochemical yields (decay-corrected) for each step of the synthesis of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG. The value given in parentheses is the number of repetitions of each reaction.

| Radioligand | [18F]MFBG (%) |

[18F]PFBG (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorination step (Fluorination & HLB extraction) | 21±5 (15) | 75±7 (10) |

| Reduction step (LiAlH4 reduction & ether extraction) | 88±3 (15) | 88±5 (7) |

| Coupling step (Coupling & HPLC purification) | 67±9 (12) | 66±14 (5) |

| Overall synthesis | 11±2 (12) | 41±12 (5) |

The overall radiochemical yield of [18F]PFBG was 41±12% (n = 5). The higher yield of [18F]PFBG reflects the more efficient fluorination on the para-isomer (step 1: 75±7%, n = 10).

Lipophilicity (logD) and plasma protein binding

The logD values (Table 2) indicate that a more hydrophilic molecule is obtained by substituting fluorine for iodine at the meta-position of the benzyl group. Approximately 70% of [18F]MFBG was unbound in both human and murine serum protein, whereas only 12% of 123I-MIBG was unbound in human serum, and 29% in murine serum.

Table 2.

Specific activity estimates, logD, IC50, and serum protein binding data, and doses used for various studies.

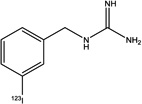

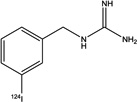

| [18F]MFBG | [18F]PFBG | 123I-MIBG | [124I]MIBG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure |

|

|

|

|

| Specific activity (GBq/µmol) | 18.7±1.1 (n = 3) | >18 | ~0.31 | > 12 |

| LogD (1-Octanol/PBS) | −0.52±0.01 (n = 2) | −0.48±0.01 (n = 2) | 0.42±0.01 (n = 3) | |

| IC50(µM) | 4.9±0.6 (n = 4) | 9.8±2.5 (n = 2) | 1.7±0.6 (n = 4) | |

| % unbound to human serum protein | 69.5±3.3 (n = 2) | NT | 12.4±0.5 (n = 2) | |

| % unbound to mouse serum protein | 66.9±1.1 (n = 2) | NT | 29.2±2.0 (n = 2) | |

| Dose for in vitro cell uptake (kBq/well) | 11.1 | 11.1 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Dose for in vivo image (MBq/mouse) | 5.5±1.8 (n = 7) | 7.4±1.8 (n = 5) | NT | 5.1 (n = 5) |

| Dose for biodistribution (MBq/mouse) | 5.9 | NT | 2.8 | 5.1 |

The number of independent studies is given in parentheses; with triplicates in each experiment. NT, not tested.

Competitive inhibition of 123I-MIBG binding by halogenated benzylguanidine analogs

Affinity studies were performed with C6-hNET cells using 123I-MIBG as the radioligand and various concentrations of MIBG, PIBG, PFBG and MFBG to compete for uptake (Table 2). The IC50 values were 1.72±0.58 µM for MIBG, 7.2±0.5 µM for PIBG, 9.8±2.5 µM for PFBG, and 4.86±0.59 µM for MFBG, respectively. Halogenation on the para-position resulted in a lower affinity than halogenation on the meta-position. Furthermore, the substitution of fluorine for iodine on the meta-position caused a ~2.8-fold loss in competitive affinity (Table 2). Typical competitive uptake curves are shown in Fig. S2.

In vitro uptake in hNET-transduced and wild-type C6 rat glioma cells

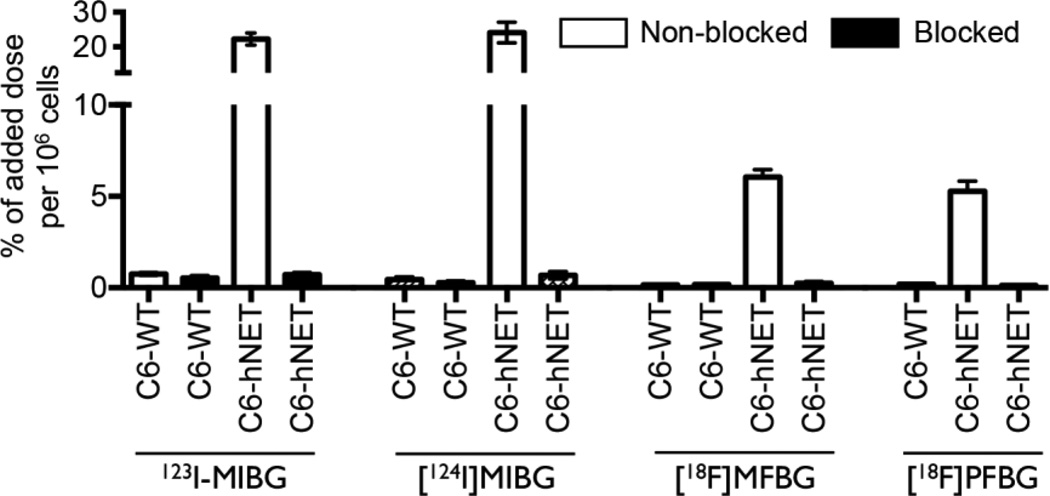

The uptake of all four ligands was significantly higher in hNET-transduced C6 compared to C6-WT cells (Fig. 2). [124I]MIBG displayed a slightly higher uptake than 123I-MIBG. The uptake of 123I-MIBG was ~4-fold greater than that of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG in the hNET-transduced cell lines (Fig. 2): 22.2±3.6 vs. 6.1±0.3 and 5.2±0.4% of added radioactivity per 106 cells, respectively. The uptake of all radioligands was specific, as MIBG (200 µM) effectively blocked their accumulation in C6-hNET cells (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

In vitro uptake of [18F]MFBG, [18F]PFBG, 123I-MIBG and [124I]MIBG in the hNET-transduced and wild-type C6 cells after 2 h incubation at 37 °C. [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG showed a similar uptake (P = 0.94), which was 4-fold lower than that of 123I/[124I]MIBG (P < 0.01). MIBG (200 µM) was used in the blocking experiments. The results (mean ± SD) are from 2–5 independent studies with triplicates in each experiment.

In vivo imaging of hNET transduced and wild-type xenografts

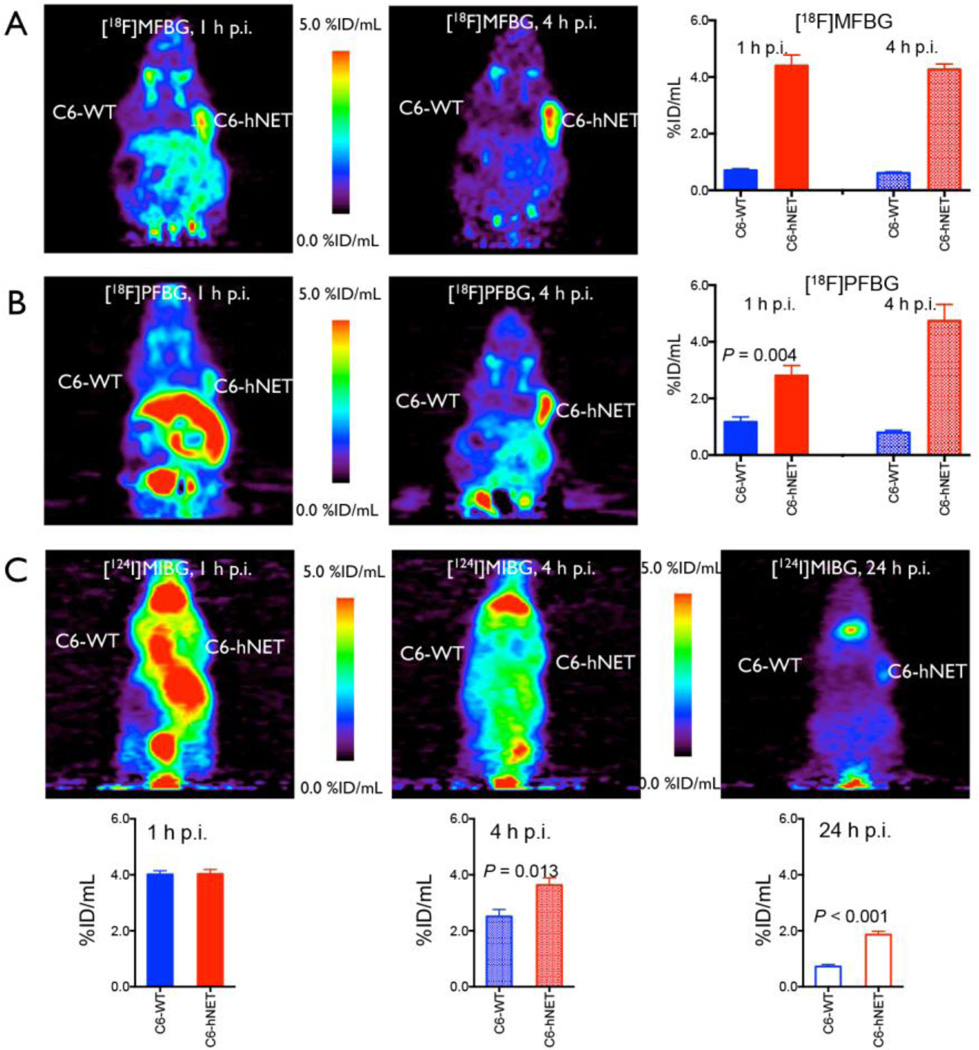

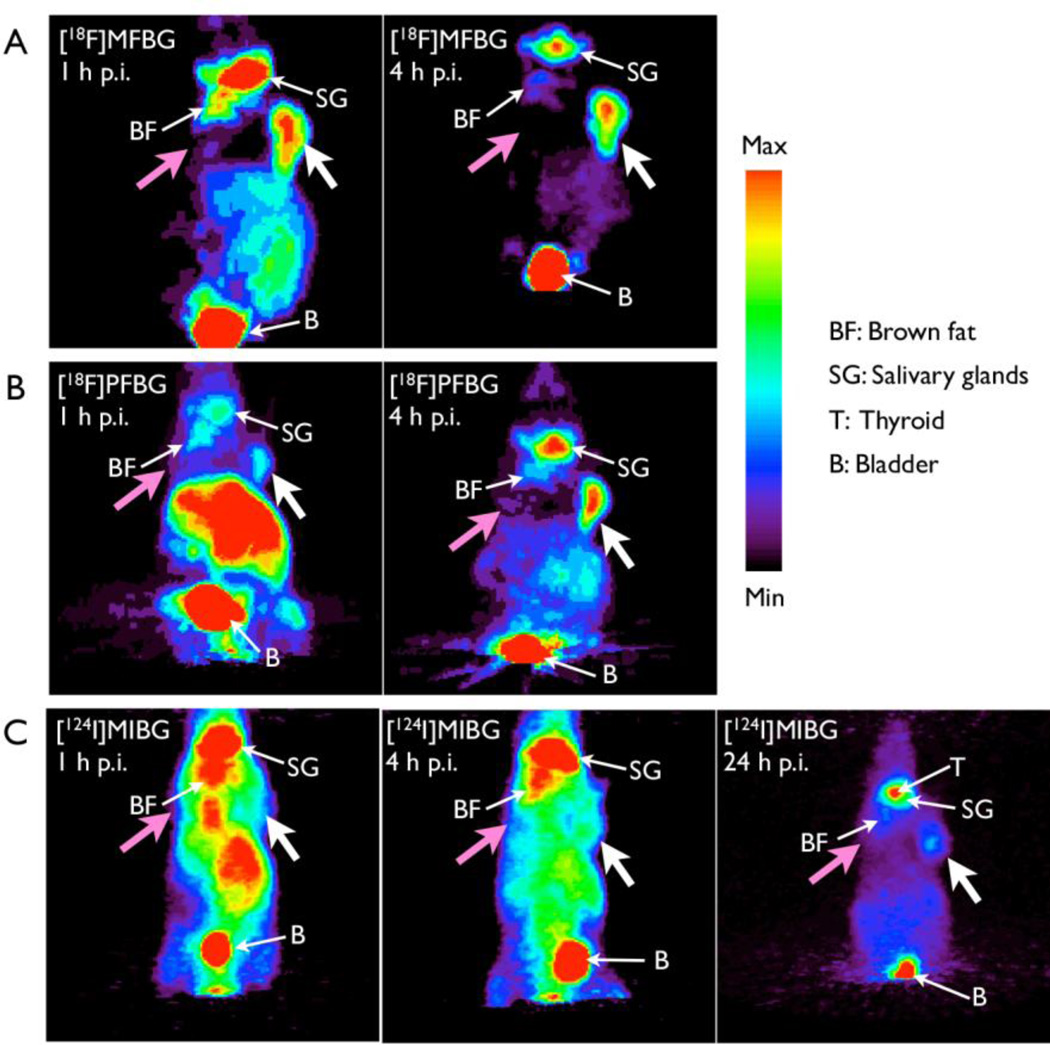

PET images of both [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG clearly delineated the hNET-transduced xenografts from the wild-type xenografts and from adjacent background radioactivity at 1 h and 4 h post injection (Figs. 3 and 4). In contrast, [124I]MIBG PET imaging visualized the C6-hNET xenografts best at 24 h or later (Figs. 3C and 4C). ROI measurements of radioactivity of all three ligands in the xenografts (obtained from the R4 PET images) showed significantly higher uptake in C6-hNET than in C6-WT xenografts at 1 h and 4 h post injection (Fig. 3), which is consistent with the results obtained from the biodistribution studies (Table 3). The ROI analysis also demonstrated that the accumulation of [18F]MFBG in C6-hNET xenografts was significantly higher than that of [18F]PFBG (P = 0.015) at 1 h p.i. (Fig. 3A and 3B), whereas the radioactivity levels were similar at 4 h (P = 0.40). The 4 h uptake of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were both significantly higher than that of [124I]MIBG at 4 h (P < 0.05) and 24 h (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3). A comparison of PET image-based tumor-to-intestine signal ratios showed that these values for [18F]MFBG (1.3±0.2 at 1 h and 2.4±0.3 at 4 h) were higher than that of [18F]PFBG (0.4±0.1 at 1 h and 1.5±0.3 at 4 h) and [124I]MIBG (0.7±0.1 at 4 h and 1.0±0.1 at 24 h). Projection of PET images (Fig. 4) also displayed a high accumulation of [18F]MFBG in C6-hNET xenografts as well as in bladder and salivary glands, and comparatively lower uptake in other normal organs, including brown fat, liver and intestine. On the other hand, [18F]PFBG showed a much higher uptake than that of [18F]MFBG in the liver area 1 h p.i. (Fig. 3B). [124I]MIBG displayed a slow washout from body. The thyroid was visualized well by [124I]MIBG PET imaging at 24 h post injection (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

In vivo accumulation of [18F]MFBG, [18F]PFBG and [124I]MIBG in animals bearing dual xenografts (C6-hNET (right) and C6-WT (left)).

(A) and (B) PET images (coronal) and ROI analysis of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG accumulation at 1 h and 4 h post injection; (C) PET images (coronal) and ROI analysis of [124I]MIBG accumulation at 1 h, 4 h and 24 h post injection. The maximum pixel value (%ID/mL) was utilized to diminish partial volume effects. The results (mean ± SD) of ROI analysis are from groups of seven ([18F]MFBG) or five ([18F]PFBG and [124I]MIBG) animals each. [18F]MFBG visualized C6-hNET xenografts with a higher tumor-to-background ratio.

Figure 4.

Typical PET projection images of [18F]MFBG, [18F]PFBG and [124I]MIBG in animals bearing dual xenografts (C6-hNET (right) and C6-WT (left)). [18F]MFBG (A) and [18F]PFBG (B) PET imaged at 1 h and 4 h p.i., respectively; (C) PET images of [124I]MIBG at 1 h, 4 h and 24 h post injection. The projection images are from the same animals shown in Figure 3. A color threshold was optimized to visualize the C6-hNET tumor (white arrow) on the projection image; the C6 wild-type tumor (pink arrow) was not visualized.

Table 3.

Biodistribution of [18F]MFBG, 123I-MIBG and [124I]MIBG in animals bearing dual C6-hNET and C6-WT xenografts.

| % Injected Dose/g tissue | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organs | [18F]MFBG* | 123I-MIBG† | [124I]MIBG* | |

| 4 h p.i. (n = 6) |

4 h p.i. (n = 4) |

4 h p.i. (n = 5) |

24 h p.i. (n = 5) |

|

| C6-hNET | 4.25±0.95 | 4.02±0.35 | 6.02±0.51 | 3.58±0.55 |

| C6-WT | 0.57±0.08 | 0.49±0.04 | 1.27±0.10 | 0.22±0.02 |

| Blood | 0.25±0.05 | 0.66±0.10 | 0.76±0.15 | 0.21±0.02 |

| Stomach | 0.46±0.12 | 0.77±0.34 | 2.85±0.54 | 1.08±0.08 |

| Kidneys | 0.99±0.29 | 0.84±0.11 | 2.09±0.10 | 0.64±0.04 |

| Intestinal wall (S) | 2.16±0.26 | 3.67±1.05 | 10.3±0.6 | 2.66±0.18 |

| Intestinal contents (S) | 1.36±0.11 | 5.24±0.46 | 6.92±1.79 | 1.76±0.40 |

| Intestinal wall (L) | 1.72±0.52 | 2.96±0.74 | 7.88±0.74 | 3.18±0.45 |

| Intestinal contents (L) | 1.26±0.23 | 2.25±0.29 | 3.62±0.89 | 2.00±0.06 |

| Pancreas | 0.78±0.06 | 1.15±0.13 | 3.48±0.31 | 0.75±0.10 |

| Spleen | 1.50±0.19 | 2.51±0.29 | 4.43±0.35 | 1.36±0.27 |

| Liver | 2.05±0.30 | 2.27±0.18 | 5.42±0.44 | 1.00±0.05 |

| Muscle | 0.62±0.09 | 0.95±0.13 | 3.21±0.28 | 0.69±0.07 |

| Heart | 2.21±0.66 | 2.10±0.14 | 19.6±2.5 | 2.93±0.17 |

| Lungs | 1.30±0.20 | 2.84±0.38 | 9.50±2.26 | 1.55±0.37 |

| Adrenals | 5.56±2.34 | 7.34±2.63 | 13.9±1.7 | 7.46±1.78 |

| Bone | 0.89±0.16 | 0.71±0.10 | 2.56±0.27 | 0.45±0.09 |

| Salivary glands | 6.09±1.02 | 8.41±0.83 | 29.1±1.8 | 7.95±0.81 |

| C6-hNET/tissue ratio | ||||

| Blood | 17.1±4.4 | 6.4±1.3 | 8.4±1.9 | 17.0±3.1 |

| Muscle | 6.8±0.9 | 4.3±0.4 | 1.9±0.3 | 5.2±0.4 |

| Liver | 2.1±0.4 | 1.8±0.2 | 1.1±0.2 | 3.6±0.7 |

| Intestine wall (S) | 1.9±0.4 | 1.4±0.3 | 0.6±0.1 | 1.4±0.2 |

| Intestine wall (L) | 1.8±0.7 | 1.7±0.2 | 0.8±0.1 | 1.1±0.2 |

| Heart | 0.6±0.4 | 1.9±0.1 | 0.3±0.1 | 1.2±0.2 |

| Adrenal | 1.9±0.7 | 0.7±0.2 | 0.4±0.0 | 0.5±0.1 |

| Salivary gland | 0.7±0.1 | 0.5±0.0 | 0.2±0.0 | 0.5±0.1 |

No carrier added synthesis;

Carrier-added (~0.31 GBq/µmol); Values: Mean ± SD.

Since the accumulation of [18F]MFBG in C6-hNET xenografts (Fig. 3A) was essentially the same at 1 h and 4 h post injection (P = 0.75), these observations suggested that the accumulation of [18F]MFBG in the hNET-positive tumor was much faster than that of [18F]PFBG, and reached a plateau at 1 hour post injection (Fig. 3A and 3B). Another important observation is the more rapid clearance of [18F]MFBG radioactivity from the non-targeted organs (e.g. GI tract) compared to [18F]PFBG and [124I]MIBG (no-carrier-added) or 123I-MIBG (carrier-added), and [18F]MFBG was excreted predominantly through the urinary system (Fig. 3). The higher levels of 123I/[124I]MIBG in the liver and intestine, suggest a slower clearance by the hepatobiliary system, and the higher levels of radioactivity in the stomach suggest de-iodination of MIBG (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Imaging the norepinephrine transporter (NET) has been used to diagnose and identify the extent of neuroendocrine tumors [5, 7, 24] and to document sympathetic nervous system dysfunction in congestive heart failure and other heart diseases [2, 25]. Both 131I-and 123I-labeled MIBG have been utilized extensively in the clinic for many years, and recently [124I]MIBG also has been developed for targeted imaging of NET with PET. Although a number of [18F]fluorine-labeled MIBG analogs have been developed previously, none attracted much attention for imaging hNET expression in human cancer or for use with the hNET reporter system. We assumed that the more hydrophilic ligand could be excreted quickly from non-target tissues and allow imaging at 1–4 h post injection. Among all [18F]fluorine-labeled benzylguanidine analogs that have been synthesized, only [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were more hydrophilic than MIBG. Thus, we focused on optimizing the synthesis of these two ligands and performing direct in vitro and in vivo comparisons with 123I/[124I]MIBG.

Radiosynthesis of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG

To synthesize both [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG, a three-step approach (Figure 1) was utilized. The overall radiochemical yields for both [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were slightly higher than the published results [13] as a result of a shorter reaction time (50 versus 60 min) and slightly higher yields in each step. More importantly, our synthesis was performed at much lower reaction temperatures. For example, the fluorination at the meta-substituted precursor to yield 3-[18F]fluorobenzonitrile was performed at 90 °C for 15 min resulting in isolated yields of 21±5% (n = 15), with a radiochemical purity of > 98% after HLB cartridge purification. In comparison, Garg et al. performed the reaction at 150–160 °C for 30 min and obtained 3-[18F]fluorobenzonitrile in 10–20% radiochemical yields, with a radiochemical purity of 90–94% [13]. In the third step, the reaction of [18F]fluorobenzylamine with 1H–pyrazole-1-carboximidamide is more efficient than that reported by Garg et al. using 2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea sulfate. Our radiochemical yields for this step (at 100 °C for 20 min) including HPLC purification were 67±9% (n = 12) for [18F]MFBG, and 66±14% (n = 5) for [18F]PFBG, respectively. On the other hand, the yields obtained by Garg et al., using 2-methyl-2-thiopseudourea sulfate as the guanidinylation agent was 50% (120–130 °C for 20–25 min) [13].

When 3.7 GBq of [18F]fluoride is used at the beginning of the synthesis, our current approach consistently provided more than 111 MBq of [18F]MFBG at the end of radiosynthesis (EOS), which will be a sufficient dose for one pediatric patient in the future. One has to start with approximate 11.1 GBq of [18F]fluoride to obtain 370 MBq [18F]MFBG at EOS for adult patients. It may be necessary to further optimize the first fluorination step in order to provide large-scale synthesis and to translate this manual approach to an automatic synthesizer for routine imaging in the clinic.

In vitro validation

Both [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG are more hydrophilic than 123I-MIBG and other [18F]fluorine-labeled MIBG analogs [16]. Our data from the octanol-PBS (pH 7.4) partition coefficient studies are in agreement with the calculated values that have been reported (20). We also show that [18F]MFBG is 70% unbound in human serum, whereas 123I-MIBG is only 12% unbound in human serum. We expected that [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG, which are more hydrophilic and less protein binding, would be transported more effectively into hNET-expressing cells, both in vitro and in vivo, when compared to the more hydrophobic MIBG. However, this was not the case as the uptake of 123I/[124I]MIBG was significantly higher in C6-hNET cells, compared to that of [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG. Garg et al. previously reported that the magnitude of both [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG uptake in SK-N-SH cells (neuroblastoma cell line expressing hNET) was lower than that of 131I-MIBG [13]. In addition, our IC50 value for MIBG uptake was significantly lower than that obtained with MFBG and PFBG. Nevertheless, the in vitro uptake of all three tracers in C6-hNET cells was highly specific as demonstrated by the low uptake in C6 wild-type cells and by the effective blocking of uptake in C6-hNET cells with excess of MIBG.

In vivo validation

The in vivo PET imaging studies showed that both [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG were able to visualize C6-hNET xenografts well at early time points, especially at 4 h post injection. The [18F]MFBG uptake tended to plateau after 1 h, and further improvement in image quality (tumor/background contrast) was achieved by the more rapid whole-body clearance of radioactivity. Compared to [18F]PFBG PET imaging (1 h and 4 h p.i.) and [124I]MIBG PET imaging (4 h and 24 h p.i.), [18F]MFBG PET imaging was able to more clearly distinguish the C6-hNET xenografts within hours of tracer administration. To achieve similar target-to-background resolution with [124I]MIBG requires PET imaging at late time points; e.g., 2–3 days post injection [4]. It is of note that [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG may display a varied accumulation though neuronal uptake-1 and nonneuronal catecholamine uptake-2 mechanism in different species [19] and different NET-positive organs within the same species. This may explain why [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG displayed differences in heart and adrenal uptake [13] in the mice.

In contrast to the in vitro uptake data, [18F]MFBG accumulation in C6-hNET xenografts in vivo was similar to that of 123I-MIBG of relatively low specific activity, but lower than that of no-carrier-added [124I]MIBG (including NET-positive organs such as heart and adrenals). Several reasons for this observation are possible. One key-contributing factor may be that [18F]MFBG has a lower affinity to NET, but less serum protein binding due to its higher hydrophilicity resulting in a higher free, unbound fraction.

Our in vitro competitive uptake studies suggested that specific activity might significantly affect hNET-mediated accumulation in cells, when the specific activity was less than 3.7 MBq/µmol (see Fig. S2). Carrier-added 123I-MIBG (~0.31 GBq/µmol) administered to athymic nude mice (2.8 MBq, ~9 nmol) resulted in lower in vivo uptake in most organs and in both C6-hNET and C6-wild type xenografts compared to that seen with no-carrier-added [124I]MIBG (>12 GBq/µmol) at 4 h. Similar in vivo results have been reported comparing the uptake between carrier-added 123I-MIBG (0.5 MBq, ~0.006 nmol per mouse) and no-carrier-added [123I]MIBG [26] in BALB/c mice. Vaidyanathan et al. reported that no-carrier-added [123I]MIBG had a significantly higher accumulation in NET-positive organs and also in some background tissues, such as liver, lungs and kidneys [26].

Image contrast in vivo is determined not only by specific uptake in tumor, but also by nonspecific uptake in the surrounding normal tissues. [18F]MFBG background radioactivity in non-NET expressing organs was generally less than that of 123I-MIBG, and significantly less than that of [124I]MIBG at 4 h post injection. These results reflect the more rapid body clearance of [18F]MFBG compared to that of 123I/[124I]MIBG. The more hydrophilic ligand ([18F]MFBG) would be excreted more rapidly from the body and non-target tissues through the urinary system, whereas the more hydrophobic ligand (123I/[124I]MIBG) clears preferentially via the hepatobiliary route resulting in significantly higher radioactivity levels in the intestinal contents. Other factors may include differences in the rate of oxidative metabolism and degradation; for example, 123I- and 124I-labeled MIBG and [76Br]MBBG did show in vivo dehalogenation [12], whereas [18F]MFBG has a stronger carbon-halogen bond and is less susceptible to dehalogenation. Our PET imaging and biodistribution studies showed a similar background accumulation of radioactivity in bone at 4 h post injection with [123I]MIBG and [18F]MFBG, suggesting there is little or no defluorination for [18F]MFBG. Although free iodide from deiodination of MIBG is accumulated by the thyroid gland, the thyroid was visualized most clearly in the 24 h images, which implies that deiodination of MIBG occurred slowly.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that [18F]MFBG and [18F]PFBG radiosynthesis can be accomplished in 3 steps. Starting with 11.1 GBq of [18F]fluoride, 370 MBq of [18F]MFBG was obtained. Our in vivo imaging studies clearly showed that [18F]MFBG yielded higher quality PET images (target-to-background) compared to [18F]PFBG between 1–4 h after administrating the tracer. We also showed that better quality images were obtained with [18F]MFBG at 4 h compared to those obtained with 123I/[124I]MIBG (at 24 h or earlier), which was due to the more rapid whole body clearance of [18F]MFBG and to higher C6-hNET-to-body organ radioactivity ratios. These results indicate that greater diagnostic accuracy with reduced radiation exposure can be obtained with [18F]MFBG PET, in comparison to 123I-MIBG SPECT or [124I]MIBG PET. In addition, the short physical half-life of 18F allows for repeated imaging studies to monitor treatment of hNET expressing neuroendocrine tumors (such as neuroblastoma), and to sequentially monitor hNET reporter gene expression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant P50 CA84638. We appreciate the assistance of staff from the MSKCC Small Animal Imaging Core Facility for the PET imaging and the MSKCC Radiochemistry & Molecular Imaging Probe Core for 18F production. These MSKCC Cores were supported by the NIH Center grant P30 CA08748. DLJT was supported by the R25T Molecular Imaging Fellowship: Molecular Imaging Training in Oncology (5R25CA096945–07; Principal investigator H. Hriack). We also thank Dr. Diane Abou for PET imaging assistance and valuable discussion. Dedicated to Prof. H. Maecke on the occasion of his 70th birthday.

Abbreviation list

- NET

norepinephrine transporter

- hNET

human norepinephrine transporter

- MIBG

meta-iodobenzylguanidine

- [18F]MFBG

meta-[18F]fluorobenzylguanidine

- [18F]PFBG

para-[18F]fluorobenzylguanidine

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

- PET

positron emission tomography

- [76Br]MBBG

meta-[76Br]Bromobenzylguanidine

- [18F]FIBG

4-[18F]fluoro-3-iodobenzylguanidine

- LMI1195

N-[3-bromo-4-(3-(18)F-fluoro-propoxy)-benzyl]-guanidine

- C6-WT

C6 wild-type rat glioma cells

- C6-hNET

hNET gene stably transduced C6 cells

- PIBG

para-iodobenzylguanidine

- TBA[18F]F

Tetrabutylammonium [18F]fluoride

- MeCN

acetonitrile

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- ROI

Region-of-interest

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

Reference

- 1.Pacholczyk T, Blakely RD, Amara SG. Expression cloning of a cocaine- and antidepressant-sensitive human noradrenaline transporter. Nature. 1991;350:350–354. doi: 10.1038/350350a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axelrod J, Kopin IJ. The uptake, storage, release and metabolism of noradrenaline in sympathetic nerves. Prog Brain Res. 1969;31:21–32. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anton M, Wagner B, Haubner R, Bodenstein C, Essien BE, Bonisch H, et al. Use of the norepinephrine transporter as a reporter gene for non-invasive imaging of genetically modified cells. J Gene Med. 2004;6:119–126. doi: 10.1002/jgm.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moroz MA, Serganova I, Zanzonico P, Ageyeva L, Beresten T, Dyomina E, et al. Imaging hNET reporter gene expression with 124I-MIBG. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:827–836. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.106.037812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunwald F, Ezziddin S. 131I–metaiodobenzylguanidine therapy of neuroblastoma and other neuroendocrine tumors. Semin Nucl Med. 2010;40:153–163. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brisse HJ, McCarville MB, Granata C, Krug KB, Wootton-Gorges SL, Kanegawa K, et al. Guidelines for imaging and staging of neuroblastic tumors: consensus report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Project. Radiology. 2011;261:243–257. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pryma D, Divgi C. Meta-iodobenzyl guanidine for detection and staging of neuroendocrine tumors. Nucl Med Biol. 2008;35:5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobson AF, Deng H, Lombard J, Lessig HJ, Black RR. 123I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy for the detection of neuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma: results of a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2596–2606. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonte JS, Robles JF, Chen CC, Reynolds J, Whatley M, Ling A, et al. False-negative 123I-MIBG SPECT is most commonly found in SDHB-related pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma with high frequency to develop metastatic disease. Endocrol Relat Cancer. 2012;19:83–93. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaidyanathan G. Meta-iodobenzylguanidine and analogues: chemistry and biology. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;52:351–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee CL, Wahnishe H, Sayre GA, Cho HM, Kim HJ, Hernandez-Pampaloni M, et al. Radiation dose estimation using preclinical imaging with 124I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) PET. Med Phys. 2010;37:4861–4867. doi: 10.1118/1.3480965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watanabe S, Hanaoka H, Liang JX, Iida Y, Endo K, Ishioka NS. PET imaging of norepinephrine transporter-expressing tumors using 76Br-meta-bromobenzylguanidine. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1472–1479. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.075465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garg PK, Garg S, Zalutsky MR. Synthesis and preliminary evaluation of para-and meta-[18F]fluorobenzylguanidine. Nucl Med Biol. 1994;21:97–103. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)90135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berry CR, Garg PK, Zalutsky MR, Coleman RE, DeGrado TR. Uptake and retention kinetics of para-fluorine-18-fluorobenzylguanidine in isolated rat heart. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:2011–2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry CR, DeGrado TR, Nutter F, Garg PK, Breitschwerdt EB, Spaulding K, et al. Imaging of pheochromocytoma in 2 dogs using p-[18F] fluorobenzylguanidine. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2002;43:183–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2002.tb01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Zalutsky MR. (4-[18F]fluoro-3-iodobenzyl)guanidine, a potential MIBG analogue for positron emission tomography. J Med Chem. 1994;37:3655–3662. doi: 10.1021/jm00047a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Zalutsky MR. Validation of 4-[fluorine-18]fluoro-3-iodobenzylguanidine as a positron-emitting analog of MIBG. J Nucl Med. 1995;36:644–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee BC, Paik JY, Chi DY, Lee KH, Choe YS. Potential and practical adrenomedullary PET radiopharmaceuticals as an alternative to m-iodobenzylguanidine: m-(omega-[18F]fluoroalkyl)benzylguanidines. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:104–111. doi: 10.1021/bc034115e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rischpler C, Fukushima K, Isoda T, Javadi MS, Dannals RF, Abraham R, et al. Discrepant uptake of the radiolabeled norepinephrine analogues hydroxyephedrine (HED) and metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) in rat hearts. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:1077–1083. doi: 10.1007/s00259-013-2393-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu M, Bozek J, Lamoy M, Guaraldi M, Silva P, Kagan M, et al. Evaluation of LMI1195, a novel 18F-labeled cardiac neuronal PET imaging agent, in cells and animal models. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4:435–443. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.962126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaidyanathan G, Affleck DJ, Alston KL, Zalutsky MR. A tin precursor for the synthesis of no-carrier-added [*I]MIBG and [211At]MABG. J Label Compd Radiopharm. 2007;50:177–182. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohara K, Vasseur JJ, Smietana M. NIS-promoted guanylation of amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:1463–1465. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Huang R, Lewis JS, Blasberg RG. Imaging human norepinephrine transporter (hNET) expressing reporter cells and tumors with 4-18F-Fluorobenzylguanidine. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1584. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howman-Giles R, Shaw PJ, Uren RF, Chung DK. Neuroblastoma and other neuroendocrine tumors. Semin Nucl Med. 2007;37:286–302. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Travin MI. Cardiac neuronal imaging at the edge of clinical application. Cardiol Clin. 2009;27:311–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaidyanathan G, Zalutsky MR. No-carrier-added meta-[123I]iodobenzylguanidine: synthesis and preliminary evaluation. Nucl Med Biol. 1995;22:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(94)00078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.