Abstract

Background

Infections occurring among vaccinated persons (vaccine failures) are known to occur in vaccines with imperfect efficacy. Failures among vaccinated children who were infected with vaccine-matched influenza B virus strain have not been adequately characterized.

Methods

Taking advantage of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of trivalent seasonal influenza vaccine (TIV), the viral shedding and clinical symptoms associated with RT-PCR confirmed influenza B infection, and serum haemaggluttination inhibiting antibody response to vaccine were compared between children 6-17y receiving TIV and placebo.

Results

Vaccine failures were observed to show lower antibody response to TIV compared to other vaccine recipients. We did not find any evidence that vaccination reduced the severity or duration of clinical symptoms of RT-PCR confirmed vaccine-matched influenza B infections. Vaccination was not observed to alter viral load or shedding duration.

Conclusion

TIV was not observed to ameliorate clinical symptoms or viral shedding among vaccine failures compared with infected placebo recipients. Lower antibody response might have explained vaccine failure and also lack of effect in reducing clinical symptoms and viral shedding upon infection. Our results are based on a RCT of split virus inactivated vaccine and may not be applicable to other vaccine types. Further studies in vaccine failure among children will be important in future vaccine development.

Keywords: vaccine, randomized controlled trial, viral shedding, illness

BACKGROUND

Influenza vaccine is efficacious in preventing influenza infections in school-age children (1). While infections in vaccinated persons, referred to as vaccine failures, are known to occur in vaccines with imperfect efficacy (2), few studies have investigated whether trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine (TIV) can reduce seriousness of illness or the degree or duration of viral shedding in vaccine failures in children (3). In a large randomized controlled trial in children aged 6-17y, TIV had moderate to high efficacy in preventing confirmed influenza B virus infections (4). In further analysis of data from that trial, here we examined the effect of TIV on patterns in viral shedding and illness associated with confirmed influenza B virus infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and follow up

796 children 6-17y of age were randomly allocated to receive 1 dose of TIV (0.5 mL VAXIGRIP; Sanofi Pasteur) or saline placebo from August 2009 through February 2010. Vaccines and placebos were repackaged as part of the double-blind study design. One of the vaccine strains included a B/Brisbane/60/2008-like (Victoria-lineage) virus. After vaccination, subjects and their households were intensively monitored for 9-12m for acute upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) and healthcare utilization through daily symptom diaries and biweekly telephone follow-up. Participants were asked to report to the study hotline immediately if any household members developed signs or symptoms of URTI (any 2 of: tympanic temperature ≥37.8°C, chills, headache, sore throat, cough, runny nose or muscle pain), which would trigger a home visit. During home visits, nose and throat swabs (NTS) were collected from all household members regardless of illness by a study nurse. The NTS were pooled in a single tube of viral transport medium, and transported to the central laboratory within 24 hours and frozen at −70°C. The home visits were arranged immediately upon receipt of illness report, and were repeated at 3d intervals until URTIs resolved. Serum specimens were collected immediately before and 1m after receipt of TIV/placebo and stored at −70°C. Proxy informed consent was obtained from legal guardians for all children and written assent was obtained from children aged 8-17y. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong. Additional details of the study are reported elsewhere (4).

Matrix gene-specific quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR assays were used to detect influenza A and B viruses from NTS, and determine viral load. The lower detection limit was approximately 900 virus gene copies per milliliter (5). Influenza B lineage differentiation was done by lineage-specific PCR assay targeting the HA gene. Serum specimens were tested in parallel by a haemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay against the vaccine strain B/Brisbane/60/2008-like (Victoria-lineage), in serial doubling dilutions from an initial dilution of 1:10 to endpoint (4).

Statistical methods

The present analyses included subjects with PCR-confirmed influenza B virus infections. The swab collection dates were matched within 3 days before and 7 days after date of illness onset recorded in the symptom diary and telephone follow-up. Information on signs or symptoms of URTI from 5d before to 15d after the date of illness onset was also extracted. Viral loads were analyzed using a log-linear mixed-effects model using unstructured covariance structure (6). The model allows for repeated measures for each subject and inclusion of vaccination status and day from symptom onset as covariates. Subsequent negative swabs collected in the same URTI episode (within a 14 day period) were also included in the model and they were regarded as left-censored at the lower limit of detection of the PCR assay. Time to alleviation of respiratory symptoms (cough, sore throat or runny nose), systemic symptoms (chills, headache, fever or muscle pain) and fever was compared between TIV and placebo groups using Weibull accelerated failure time models (7). In these models, the effect of TIV was assumed to either proportionally increase or decrease the median time to alleviation of symptoms, and the effect could be assessed for statistical significance. We stratified by age (6-8y versus 9-17y) in sensitivity analyses. The HAI titers before and 1 month after vaccination were compared between subjects with PCR-confirmed infection versus those without PCR-confirmed influenza using Wilcoxon signed-ranked tests for the TIV and placebo groups separately. Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 2.15.2.

RESULTS

Of 796 randomized children, 470 (TIV) and 312 children (placebo) completed follow-up. Among these 782 children, we collected 1471 NTS and were able to identify 60 episodes of PCR-confirmed influenza. Due to small numbers of PCR-confirmed influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, A(H3N2) and B(Yamagata-lineage) infections, the present analyses focused on the 32 episodes of confirmed influenza B(Victoria-lineage) infections. These episodes occurred a median of 127 days (range=48-251 days) following vaccination. The circulating influenza B viruses remained antigenically close to the vaccine strain based on phylogenetic analyses of their HA gene (9). Overall, 20 (63%) of the PCR-confirmed influenza B infections could be matched with a URTI episode. While TIV showed 66% (95%CI: 33-83%) efficacy in preventing PCR-confirmed influenza B (4), the proportion of PCR-confirmed infections that could be matched with illness episodes did not differ by vaccination status (p=0.83). One TIV recipient (0.22%) was hospitalized for 3 days for pneumonia with unknown etiology and one placebo recipient (0.32%) were hospitalized overnight for tachycardia with no URTI symptoms. Vaccine failures had lower post-vaccination HAI titers compared to the other TIV recipients (p=0.04) while the difference in pre-vaccination titer (p=0.31) and geometric HAI titer rise following vaccination (p=0.10) were not statistically significant (Appendix Figure 2). The age (p=0.75) and vaccination history (p=0.65) of vaccine failures were comparable to other TIV recipients.

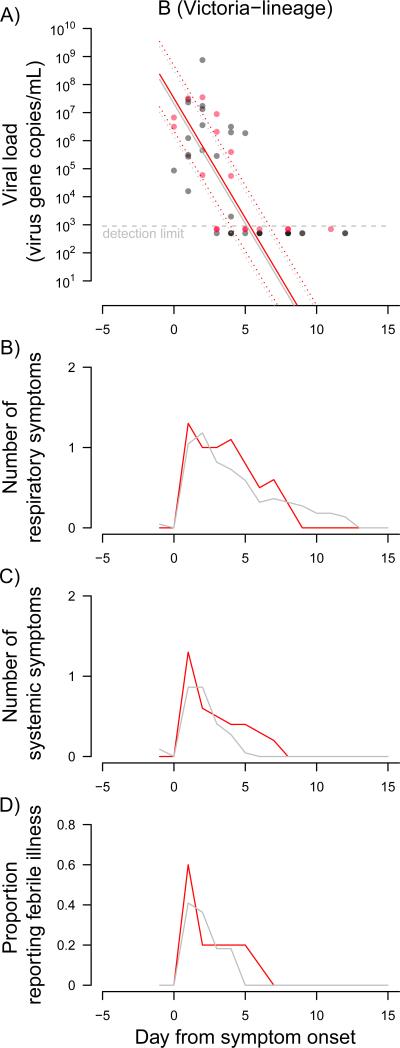

Figure 1 shows the patterns in daily viral shedding and mean number of symptoms in the 20 confirmed infections. Viral shedding was observed to decline following a log-linear trend and was projected to cease at around day 10 with no significant difference between the TIV group (i.e. vaccine failures) compared to the placebo group (p=0.78). Patterns in illness were similar (Figure 1), and there was no significant difference between confirmed infections in the TIV versus placebo recipients in median time to alleviation of respiratory symptoms (p=0.21), systemic symptoms (p=0.44), or fever (p=0.89). Results were similar when stratifying into 6-8y and 9-17y age groups, although the lower sample sizes led to wider confidence intervals in these comparisons (data not shown).

Figure 1.

A) Patterns in viral shedding of 20 episodes of symptomatic PCR-confirmed influenza B (Victoria-lineage) infections among children who were randomly allocated to trivalent inactivated vaccine (TIV) (red circles) or placebo (gray circles). The patterns in viral shedding were compared between TIV and placebo recipients using linear mixed-effect models allowing for multiple nose and throat swabs collected from the same subjects on different day within the same illness episode. The fitted regression lines are shown (red: TIV; gray: placebo) with 95% confidence intervals (dashed lines). B) & C) Mean number of reported respiratory (cough, sore throat or runny nose) and systemic (chills, headache, fever or muscle pain) signs/symptoms. D) Proportion of symptomatic PCR-confirmed cases reporting fever ≥37.8°C. Illness onset was defined as the first day of respiratory or systemic sign/symptom within an episode of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI). Absence of any signs/symptom for 3 days was used to determine the end of an URTI episode.

DISCUSSION

We previously reported TIV to be efficacious (VE=66%; 95%CI 33-83%) in preventing PCR-confirmed infection with influenza B (4). In this study we did not find any evidence that TIV additionally reduced the duration of illness, or the degree or duration of influenza B virus shedding in PCR-confirmed cases. Most importantly, low antibody response to TIV was observed among vaccine failures although their age and vaccination history did not differ from other TIV recipients.

There is ongoing discussion on whether inactivated vaccines can affect illness severity in vaccine failures. There have been very few studies in children (10,11). A case-control study in younger children found inactivated vaccine associated with lower occurrence of high fever (12). Previous volunteer challenge studies in sero-negative (HAI titer ≤1:8) adults estimated inactivated vaccine to be 40% effective in reducing infectiousness and 67% effective in preventing illness given infection (3). Our study, however, differs from those volunteer challenge studies which did not involve children, typically screened out seropositive participants, and involved a much shorter delay between vaccination and infection. In our study, a significant proportion of children had detectable antibodies before vaccination suggesting they may be protected by some degree of pre-existing immunity.

There are studies suggesting HAI antibody is associated with reduced illness severity (13,14) and inactivated vaccines are designed primarily to elicit immune response involving HA antibodies (15). With varying antigenic contents in the vaccines, it is not surprising some studies have demonstrated neuraminidase antibodies, CD4+ T cells, IL-8 and TNF- α response to inactivated vaccines (15-17). Other short-lasting cell mediated immune responses to inactivated vaccines have also been documented (18). Infections in our study occurred on average 3-5 months after vaccination while some of the antibody response to TIV should still persist. However, vaccine failures both in our study and other studies (2) have been characterized by low post-vaccination HAI antibody titers to influenza B. A low level of post-vaccination HAI titer in vaccine failures may therefore explain why those subjects were not protected against influenza B infection, and why there was no apparent effect on the degree and duration of illness and viral shedding. Further understanding on factors associated with vaccine failure is required as studies analyzing other RCTs reported that A(H3N2) vaccine failures had good HA antibody response to inactivated vaccination (19).

The major strength of our study is that confounding is minimized by randomization, and double blinding should have ensured minimal bias in ascertainment of infections. Confounding may still exit in our study because vaccine recipients who were still infected despite vaccination may have different unmeasured immunological characteristics compared with those infected in the placebo group (20). Our study also suffers from the limitation of under-ascertainment of PCR-confirmed infections in cohort studies (21,22). Although our RCT is relatively large, it was underpowered to identify the effects of TIV on risk of severe disease. Considerably larger studies would be needed given that influenza virus infection tends to cause mild disease in school-age children. Unlike volunteer challenge studies, our study design did not allow detailed examination of asymptomatic infections. The volunteer challenge model may permit greater characterization of asymptomatic infections but this approach could not provide information on children. In addition, the generalizability of challenge studies is uncertain because the delivered dose and site of virus infection in the respiratory tract may not be comparable for challenge studies and naturally acquired infections. Although we collected post-study serology from our study subjects (4), illness episodes in subjects with serologic evidence of influenza infection could be associated with influenza or other infections. Moreover, serology can fail to identify infections in vaccinated children because of antibody ceiling effects following vaccination (2).

In our study, children aged 6-8y were given 1 dose of TIV, presuming children in Hong Kong are more experienced with influenza infection and a priming dose might not be required (23). We did not find evidence of lower vaccine efficacy among children aged 6-8y. Finally, our findings do not apply to whole virus inactivated vaccines as its antigenic content may differ from the split virus vaccine used in our study.

Supplementary Material

Appendix Figure 1. Geometric titer rise one month after receipt of TIV/ placebo among subjects with (dark gray) and without (light gray) subsequent PCR-confirmed influenza B (Victoria-lineage) during the follow-up period. The median and inter-quantile ranges are marked alongside the individual values. The distributions of geometric titer rises were compared with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Calvin Cheng, Daniel Chu, Winnie Lim, Edward Ma, Hau Chi So and Jessica Wong for research support.

SOURCES OF FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This project was supported by the Harvard Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant no. U54 GM088558), the Research Fund for the Control of Infectious Disease, Food and Health Bureau, Government of the Hong Kong SAR (grant nos. CHP-CE-03 and PHE-2), and the Area of Excellence Scheme of the Hong Kong University Grants Committee (grant no. AoE/M-12/06). The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, preparation of the manuscript, or the decision to publish.

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

DKMI has received research funding from F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd. JSMP receives research funding from Crucell NV and serves as an ad hoc consultant for GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi Pasteur. BJC has received research funding from MedImmune Inc., and consults for Crucell NV. The authors report no other potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrie JG, Ohmit SE, Johnson E, Cross RT, Monto AS. Efficacy studies of influenza vaccines: effect of end points used and characteristics of vaccine failures. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1309–1315. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basta NE, Halloran ME, Matrajt L, Longini IM., Jr. Estimating influenza vaccine efficacy from challenge and community-based study data. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1343–1352. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowling BJ, Ng S, Ma ES, et al. Protective efficacy against pandemic influenza of seasonal influenza vaccination in children in Hong Kong: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55:695–702. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ip DK, Schutten M, Fang VJ, et al. Validation of self-swab for virologic confirmation of influenza virus infections in a community setting. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:631–634. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pan W, Louis TA. A linear mixed-effects model for multivariate censored data. Biometrics. 2000;56:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collett D. Modelling survival data in medical research. 2 ed: Chapman & Hall/CRC; FL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akaike H. Citation Classic - a New Look at the Statistical-Model Identification Current Contents/Engineering Technology & Applied Sciences. 1981:22–22. [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Medical Research Report prepared for the WHO annual consultation on the composition of influenza vaccine for the Southern Hemisphere. 2010. September 2010.

- 10.Johnson PR, Feldman S, Thompson JM, Mahoney JD, Wright PF. Immunity to influenza A virus infection in young children: a comparison of natural infection, live cold-adapted vaccine, and inactivated vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:121–127. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suess T, Remschmidt C, Schink SB, et al. Comparison of shedding characteristics of seasonal influenza virus (sub)types and influenza A(H1N1)pdm09; Germany, 2007-2011. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamada M, Nagai T, Kumagai T, et al. Efficacy of inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine in alleviating the febrile illness of culture-confirmed influenza in children in the 2000-2001 influenza season. Vaccine. 2006;24:3618–3623. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Couch RB, Atmar RL, Franco LM, et al. Antibody correlates and predictors of immunity to naturally occurring influenza in humans and the importance of antibody to the neuraminidase. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:974–981. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monto AS, Kendal AP. Effect of neuraminidase antibody on Hong Kong influenza. Lancet. 1973;1:623–625. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)92196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couch RB, Atmar RL, Keitel WA, et al. Randomized comparative study of the serum antihemagglutinin and antineuraminidase antibody responses to six licensed trivalent influenza vaccines. Vaccine. 2012;31:190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Couch RB. Seasonal inactivated influenza virus vaccines. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 4):D5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramakrishnan A, Althoff KN, Lopez JA, Coles CL, Bream JH. Differential serum cytokine responses to inactivated and live attenuated seasonal influenza vaccines. Cytokine. 2012;60:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He XS, Holmes TH, Zhang C, et al. Cellular immune responses in children and adults receiving inactivated or live attenuated influenza vaccines. J Virol. 2006;80:11756–11766. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01460-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohmit SE, Petrie JG, Cross RT, Johnson E, Monto AS. Influenza hemagglutination-inhibition antibody titer as a correlate of vaccine-induced protection. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1879–1885. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hudgens MG, Halloran ME. Causal Vaccine Effects on Binary Postinfection Outcomes. J Am Stat Assoc. 2006;101:51–64. doi: 10.1198/016214505000000970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horby P, Mai le Q, Fox A, et al. The epidemiology of interpandemic and pandemic influenza in Vietnam, 2007-2010: the Ha Nam household cohort study I. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1062–1074. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skowronski DM, De Serres G, Crowcroft NS, et al. Association between the 2008-09 seasonal influenza vaccine and pandemic H1N1 illness during Spring-Summer 2009: four observational studies from Canada. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu SS, Peiris JSM, Chan KH, Wong WHS, Lau YL. Immunogenicity and safety of intradermal influenza immunization at a reduced dose in healthy children. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1076–1082. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix Figure 1. Geometric titer rise one month after receipt of TIV/ placebo among subjects with (dark gray) and without (light gray) subsequent PCR-confirmed influenza B (Victoria-lineage) during the follow-up period. The median and inter-quantile ranges are marked alongside the individual values. The distributions of geometric titer rises were compared with the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.