Abstract

The social disruption of losing a partner may have particularly strong adverse effects on psychological and physiological functioning. More specifically, social stressors may play a mediating role in the association between mood disorders and cardiovascular dysfunction. This study investigated the hypothesis that the disruption of established social bonds between male and female prairie voles would produce depressive behaviors and cardiac dysregulation, coupled with endocrine and autonomic nervous system dysfunction. In Experiment 1, behaviors related to depression, cardiac function, and autonomic nervous system regulation were monitored in male prairie voles during social bonding with a female partner, social isolation from the bonded partner, and a behavioral stressor. Social isolation produced depressive behaviors, increased heart rate, heart rhythm dysregulation, and autonomic imbalance characterized by increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic drive to the heart. In Experiment 2, behaviors related to depression and endocrine function were measured following social bonding and social isolation in both male and female prairie voles. Social isolation produced similar levels of depressive behaviors in both sexes, as well as significant elevations of adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticosterone. These alterations in behavioral and physiological functioning provide insight into the mechanisms by which social stressors negatively influence emotional and cardiovascular health in humans.

Keywords: adrenocorticotropic hormone, autonomic nervous system, behavior, cardiovascular, corticosterone, depression, heart rate variability, microtus, respiratory sinus arrhythmia, social isolation, stress

1. Introduction

Supportive social relationships have a positive influence on mood and emotion as well as physiological functioning. For instance, they help protect against cardiovascular disease (CVD), improve responses to depression, and facilitate adaptive stress coping reactions (Blazer, 1982; Cacioppo, & Cacioppo, 2012; Eisenberger, 2013; Frasure-Smith et al., 2000; Kikusui et al., 2006; Norman et al., 2013; Orth-Gomer et al., 1993). Frasure-Smith et al. (2000) assessed baseline depression and social support in patients suffering from myocardial infarction, along with cardiac prognosis and changes in depression symptoms after the infarction. High levels of perceived social support were associated with improvements in depressive symptoms and a reduced impact of depression on mortality over the first year following the infarction.

Conversely, disruption of social bonds, social isolation, and perceived isolation (loneliness) are associated with various forms of dysfunction and mortality both in humans and animal models (Barger, 2013; Cacioppo, & Hawkley, 2003; Grippo et al., 2007c; Grippo et al., 2011; Seeman, & Crimmins, 2001; Uchino, 2006). For example, individuals with low levels of social engagement experience an increased risk of general and CVD-related mortality (Ramsay et al., 2008); and both social isolation and feelings of loneliness are correlated with increased mortality in older men and women (Steptoe et al., 2013). Men and women may respond differently to social and environmental stress. While some studies indicate that women are more likely than men to experience depressive or anxiety disorders, men are more likely to report greater impairment in everyday functioning as a result of these psychological disturbances (Scott, 2011).

The specific neurobiological mechanisms that underlie emotional and cardiovascular dysfunction are not well defined, however, both types of disorders share similar physiological dysfunctions and both appear to be influenced by the social environment. A better understanding of the influence of social experiences on health may lead to improved outcomes for millions of individuals worldwide affected by CVD and/or depressive disorders (American Heart Association, 2011; Murray & Lopez, 1996; National Institute of Mental Health, 2009). Both depression and CVD are characterized by an imbalance of autonomic cardiac regulation, altered heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV), vascular disturbances, and neurohumoral and immune dysregulation (Burg et al., 2013; Carney, & Freedland, 2003; Hance et al., 1996; Dantzer, 2006; Penninx et al., 2001). Similarly, endocrine dysregulation (such as increased cortisol) is linked with atherosclerosis of carotid arteries (Dekker et al., 2008), and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction has been implicated in depression (Hinkelmann et al., 2009; Holsboer et al., 1984). These endocrine and autonomic mechanisms may be disrupted during social stress, which are likely to influence stress reactivity in both depressive and cardiovascular disorders. Social support has been suggested to have a positive influence on health by increasing an individual's valuation of self-esteem, control, and health behaviors; and decrease his/her appraisal of stress (Uchino et al., 1999). This down-regulation of responses to adverse events may in turn decrease the stress placed on the individual's body, resulting in more adaptive responses to stressors and greater overall health (Uchino et al., 1999).

Studies involving animal models provide insight into the neurobiological and biobehavioral mechanisms that underlie the associations among social stress, emotion, and cardiovascular dysfunction. In particular, the prairie vole is a socially monogamous rodent species that provides an excellent tool for studying relationships among the social environment, behavior, and physiology. These rodents form monogamous social bonds between males and females, live in extended families, and engage in bi-parental and allo-parental care of offspring, similar to human social systems (Carter, 2001; Getz et al., 1981; Cushing et al., 2001; Young, & Wang, 2004). Prairie voles have been employed previously to investigate the neurobiological basis of attachment behavior (Aragona et al., 2003; Cushing et al., 2003; DeVries et al., 1995) and several aspects of dysfunction as a result of isolation and the disruption of social bonds (Bosch et al., 2009; Grippo et al., 2012; Lieberwirth et al., 2012; Pournajafi-Nazarloo et al., 2011).

Substantial evidence indicates that prairie voles are sensitive to disruptions of the social environment. For example, female prairie voles exposed to long-term social isolation from a family member exhibit several deleterious changes in behavioral, endocrine, and autonomic function including depressive and anxiety behaviors, increased HR, decreased HRV, exaggerated cardiac and neuroendocrine reactivity to acute stressors, dysregulated autonomic cardiac control, and endothelial dysfunction (Bales et al., 2006; Grippo et al., 2007c; Grippo et al., 2012; Stowe et al., 2005; Peuler et al., 2012). Further, early life social isolation has been associated with anxiogenic behaviors and altered social interactions, in addition to increased expression of stress hormones in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (Pan et al., 2009). Finally, male prairie voles exposed to short-term social isolation from a female social partner exhibit poor stress-coping behaviors and increased circulating hormone levels following separation (Bosch et al., 2009). These characteristics contribute to the utility of the prairie vole for the investigation of neurobiological mechanisms underlying social stress and negative health consequences.

The specific autonomic and endocrine mechanisms underlying the effects of disrupted pair bonds are not well understood. As such, the study of disrupting male-female social bonds in prairie voles, such as that described by Bosch et al. (2009), offers a unique opportunity to investigate the neurobiological mechanisms that may influence physiological and psychological dysfunction following partner loss. The present experiments investigated the disruption of an established social bond between male and female prairie voles. Experiment 1 investigated the specific effects of social bond disruption on depressive behaviors, and autonomic and cardiac function in male prairie voles. Experiment 2 extended the investigation of the deleterious effects of disrupted social bonds on behavior and neuroendocrine function in both male and female prairie voles. These experiments tested the hypothesis that the disruption of established social bonds would result in: (a) adverse changes in autonomic and cardiac regulation during basal and stress periods, including increased HR, decreased HRV, and autonomic imbalance; (b) increased neuroendocrine reactivity following exposure to stress; and (c) behavioral responses to stress that are associated with negative affective states. The investigation of these changes in a translational animal model will help explain the underlying mechanisms by which social stressors deleteriously influence behavior and physiology in humans.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Experiment 1

2.1.1. Animals

Seventeen male prairie voles (60–90 days old) were bred in-house at Northern Illinois University. Offspring were removed from breeding pairs at 21 days of age, and housed in same-sex sibling pairs until the commencement of experimentation. Animals were allowed ad libitum access to food and tap water, maintained at a room temperature of 20–21°C and a relative humidity of 40–50%, and under a standard 14:10 light/dark cycle (lights on at 0630). All experimental protocols were approved by the Northern Illinois University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed National Institute of Health guidelines as stated in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.1.2. General Experimental Design

Table 1 depicts the timeline of all procedures in Experiment 1. Briefly, a radiotelemetry transmitter was implanted into each male prairie vole for the recording of continuous electrocardiogram (ECG) and activity variables. Following recovery, animals underwent a baseline period of ECG and activity recordings. Each experimental animal was then removed from its home cage and paired with an unrelated female prairie vole. A social bonding assessment was conducted during this period to determine whether the prairie vole pairs had formed a bond. Five days after pairing, half of the pairs were housed individually (n = 9), while the other half remained as pair-housed controls (n = 8) for an additional 5 days. A forced swim test (FST) and assessments of autonomic nervous system function were conducted following the social isolation/pairing period (while the experimental group remained isolated). Handling and cage changes were matched between the groups.

Table 1.

Experimental Timeline for Experiment 1

| Procedure | Schedule |

|---|---|

| Telemetric Transmitter Implantation | Days 1–2 |

| Recovery in Divided Cages | Days 2–6 (depending on date of transmitter implantation) |

| - ECG and activity measurements | |

| Recovery in Standard Cages | Days 6–12 (depending on date of transmitter implantation) |

| - ECG and activity measurements | |

| Baseline Period | Days 12–15 |

| - ECG and activity measurements | |

| 5 Day Social Bonding Period | Days 15–20 |

| - ECG and activity measurements | |

| Social Bond Assessment | Day 17 |

| - Digital video recording of behavior | |

| 5 Day Isolation Period | Days 20–25 |

| - ECG and activity measurements | |

| Forced Swim Test | Days 25–26 |

| - With continued isolation | |

| - Digital video recording of behavior | |

| - ECG and activity measurements | |

| Assessment of Autonomic Nervous System Function | Days 28–34 |

| - With continued isolation | |

| - ECG and activity measurements |

2.1.3. Telemetric Transmitter Implantation

Wireless radiofrequency transmitters (model TA10ETA-F10; Data Sciences International, St. Paul, Minnesota) were implanted intraperitoneally into male prairie voles similar to methods used previously (Grippo et al., 2007b). Animals were anesthetized with a mixture of isoflurane (Baxter, IL USA) and oxygen throughout the surgical procedures. Briefly, the body of the transmitter was implanted into the intraperitoneal space, and wire leads were sutured (subcutaneously) to the muscle on the left and right of the heart. Following transmitter implantation, animals were housed for 5 days in custom designed divided cages that permitted adequate healing of suture wounds (see Grippo et al., 2007b). All animals were then returned to standard cages (with the respective sibling) to recover for an additional 5–6 days. Animals were assessed for the following characteristics of recovery: (a) visible signs of eating and drinking, (b) adequate urination and defecation, (c) adequate activity level (approximately 2 counts per minute or higher), (d) adequate body temperature (approximately 37.5° C), and (e) stabilization of HR.

2.1.4. Electrocardiographic Recordings

ECG signals were collected via radiotelemetric recordings (sampling rate 5 kHz, 12-bit precision digitizing), either continuously or at hourly intervals throughout all experimental protocols. Multiple segments of 1–5 minutes of stable, continuous data were used to evaluate HR, HRV and activity level. Because activity levels are high in prairie voles and occur in approximately 2–3 hour ultradian rhythms throughout the light and dark periods (Grippo et al., 2007b), resting cardiac parameters were derived from ECG data sampled during a period of minimal activity (5 counts per minute or lower; 256 Hz sampling rate), during which time the animal may have been sitting, resting quietly, or sleeping.

2.1.5. Quantification of Cardiac Variables

All ECG signals were exported into a data file and examined manually with custom-designed software to ensure all R-waves were detected (Brain-Body Center, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL; Porges, 1985; Porges, & Bohrer, 1990). HR was evaluated using the number of beats per unit time (beats per minute, bpm). HRV was evaluated using the standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN index) and amplitude of respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). The SDNN index was calculated from the standard deviation of all R-R intervals from each data segment (Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, 1996).

The amplitude of RSA has been hypothesized to represent the functional impact of myelinated vagal efferent pathways originating in the nucleus ambiguus on the sinoatrial node (see Porges, 2007). RSA was assessed with previously-published time-frequency procedures that have been validated in humans (Porges, 1985; Porges, & Bohrer, 1990), applied to small mammals (Yongue, 1982), modified for the prairie vole (Grippo et al., 2007b), and are appropriate for use during period of both low activity and exercise (Byrne et al., 1996; Houtveen et al., 2002; Porges et al., 2007).

2.1.6. Baseline Measurement Period

Following recovery from the implantation of the radiotelemetry transmitter, the baseline period consisted of 3 days during which time the animals were housed in sibling pairs.

2.1.7. Social Bonding Period

After baseline measurements, all male animals were separated from their respective siblings and paired with an unrelated female of approximately the same age and body weight in a new, clean cage, for 5 days. To determine whether male and female pairs formed a social bond, a 3-hour assessment of behavior was conducted 48 hours following initial pairing. Based on previous research involving the study of pair bonding in prairie voles (Williams et al., 1992), male-female pairs typically bond within 48 hours of introduction. This has been observed in a 3-hour partner preference test in which the experimental animal spent the majority of its time in side-by-side contact with a familiar animal versus an unfamiliar animal, when allowed to choose freely between these 2 animals (Williams et al., 1992). Video data were scored manually by an experimentally-blind investigator for affiliative behaviors, individual behaviors of each animal in the pair, and to determine the amount of time the animals spent in side-by-side contact, an operational index of attachment (Williams et al., 1992).

2.1.8. Isolation Period

Following 5 days of social pairing, the male-female pairs were randomly assigned to isolated (n = 9 males and 9 females) or paired (control, n = 8 males and 8 females) conditions, similar to the methods described by Bosch et al. (2009). Male prairie voles in the isolated group were separated from the females for the remainder of the experiment and housed individually without auditory, olfactory, or visual cues. Paired animals were continually housed with the female partners.

2.1.9. Learned Helplessness Assessment

Following the period of isolation or continued pairing (while the experimental group remained isolated), the FST was used as an index of learned helplessness (e.g., “behavioral despair”). This task consisted of a training period (15-minute swim period), followed by a test period (5 minutes), separated by 24 hours (Cryan et al., 2005). The swim tank was a clear Plexiglas cylinder (height 46 cm, diameter 20 cm) filled with 18 cm of 25 ± 1° C clean tap water. Following the FST, animals were returned to the home cage and allowed access to a heat lamp for 10 minutes.

Behaviors were digitally video recorded and then imported into analysis software (Noldus Observer XT 8.0, Noldus Information Technology, Wageningen, Netherlands). Behaviors during the FST were categorized manually by 2 trained observers who were blind to the experimental conditions, according to the following criteria: (a) struggling, movements during which the forelimbs break the water surface; (b) climbing, movements during which the forelimbs break the water surface and are in direct contact with the wall of the apparatus; (c) swimming, movements of the fore and hind limbs resulting in purposeful motion without breaking the water surface; and (d) immobility, idle floating or treading water during which time the animal uses limb movement to maintain its equilibrium without any directed movement of the limbs or trunk. Struggling, climbing and swimming were summed to provide one index of active coping behaviors; immobility was used as the operational index of learned helplessness (Cryan et al., 2005).

2.1.10. Autonomic Nervous System Function Assessment

Forty-eight hours following the FST (while the experimental group remained isolated), HR was measured under the following pharmacological conditions: (a) sympathetic receptor antagonism (β1-adrenergic receptor blockade; atenolol, 8 mg/kg IP; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); (b) parasympathetic receptor antagonism (cholinergic receptor blockade; atropine methyl nitrate, 4 mg/kg IP; Sigma-Aldrich); and (c) dual blockade (both drugs). Drugs were administered in a counterbalanced manner, during a 6-day period, with 48 hours between injections. The data were manually examined to determine the peak HR response following each drug injection, during a period of stable ECG recording that was not confounded by animal movement.

2.1.11. Statistical Analyses

The data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) for all analyses and figures. A probability value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Any periods of ECG involving animal movement artifact were excluded from the analyses. The data were analyzed with 2-factor mixed-design analyses of variance (ANOVA) and Student's t-tests.

2.2. Experiment 2

2.2.1. Animals

Twenty adult male (60–90 days old) and 20 adult female (60–90-days old) prairie voles were used for the experimental procedures in Experiment 2. All breeding, housing, and handling conditions were identical to those described in Experiment 1.

2.2.2. General Experimental Design

Table 2 shows the timeline for all procedures employed in Experiment 2. Briefly, each male and female experimental animal was removed from its home cage and paired with an unrelated animal of the opposite sex for a total of 5 days. Half of the pairs (n = 10) were then housed individually, while the other half remained as pair-housed controls (n = 10), identical to the methods described in Experiment 1. Each animal was exposed to the FST (while the experimental group remained isolated), and plasma was collected 10 minutes following the 5-minute FST.

Table 2.

Experimental Timeline for Experiment 2

| Procedure | Schedule |

|---|---|

| 5-Day Pairing Period | Days 1–5 |

| 5-Day Isolation Period | Days 6–10 |

| Forced Swim Test | Days 10–11 |

| - With continued isolation | |

| - Digital video recording of behavior | |

| Assessment of Endocrine Function | Day 11 |

| - With continued isolation | |

| - Plasma collected 10 minutes after Forced Swim Test |

2.2.3. Social Bonding Period

All male and female prairie voles were removed from their respective siblings and paired with an unrelated opposite-sex animal of approximately the same age and body weight, in a new, clean cage, for 5 days, as described in Experiment 1.

2.2.4. Isolation Period

Male-female prairie vole pairs were randomly assigned to isolated (n = 10 males and 10 females) or paired (control, n = 10 males and 10 females) conditions for the remainder of the experiment, as specified in Experiment 1.

2.2.5. Learned Helplessness Assessment

The FST was used as an assessment of behavioral response to an inescapable stressor, as described in Experiment 1.

2.2.6. Collection of Plasma

Ten minutes following the end of the 5-minute FST, all animals were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine (67 mg/kg, sc; NLS Animal Health, Owings Mills, MD) and xylazine (13.33 mg/kg, sc; NLS Animal Health). Blood was sampled within 2 minutes of the anesthetic injection, from the periorbital sinus via a heparanized capillary tube, and was collected during a period not exceeding 1.5 minutes. The blood was placed immediately on ice, and then centrifuged at 4° C, at 3500 rpm, for 15 minutes to obtain plasma. Plasma aliquots were stored at −80° C until assayed for circulating ACTH and corticosterone.

2.2.7. Circulating Hormone Analyses

Plasma levels of ACTH and corticosterone were determined using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits (ACTH, EK-001-21, Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Burlingame, CA; corticosterone, ADI-900-097, Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY). Plasma samples were diluted according to the kit instructions to give results reliably within the linear portion of the standard curve (ACTH, 1:7; corticosterone, 1:500). The sensitivity of the kit for ACTH is 0.08 ng/ml (range 0–25 ng/ml) and for corticosterone is 27.0 pg/ml (range 32–20,000 pg/ml).

2.2.8. Data Analyses

Data were analyzed as specified in Experiment 1.

3. Results

3.1. Experiment 1

3.1.1. Social Bonding Assessment

All male-female pairs displayed similar side-by-side contact scores during the social bonding assessment, and additional measures of pair behaviors yielded no significant group differences. During the 3-hour assessment, all animals engaged in side-by-side contact, and all pairs engaged in side-by-side contact within two standard deviations of the mean of the pairs. The amount of time the male-female pairs spent in side-by-side contact was normally distributed. However, the animals assigned to the isolated group spent slightly more time in side-by-side contact than those assigned to the paired control group [paired, 5357 ± 199 seconds; isolated: 6164 ± 291 seconds; t(15) = 2.234, p = 0.041].

Additional behaviors during the social bonding assessment were collapsed into two general categories, affiliative and individual behaviors. Observed behaviors that appeared pro-social were categorized as affiliation behaviors, and included: (a) sniffing; (b) one animal grooming itself while in side-by-side contact; (c) one animal grooming its partner while in side-by-side contact; and (d) mating. There were no group differences in affiliation behavior scores between the male-female prairie vole pairs (p > 0.05 for all comparisons; data not shown).

Total individual behaviors represented a collection of behaviors exhibited by the male-female pairs during which time the animals were separated from one another. These behaviors were defined by one or both of the animals' activity around an observed resting location for the male-female prairie vole pair. This location was operationalized as a “home base” for behavioral scoring purposes. The activities that comprised total individual behaviors included: (a) one animal away from the home base; (b) both animals eating or drinking; (c) one animal eating or drinking and one animal away from the home base; (d) both animals away from the home base; and (e) one animal eating or drinking while the other animal was in the home base. Similar to total affiliative behaviors, there were no between-group differences in individual behaviors (p > 0.05 for all comparisons; data not shown).

3.1.2. Resting Cardiac Parameters

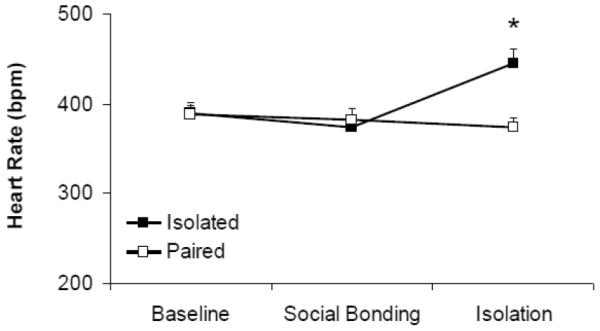

Social bond disruption significantly increased HR in isolated male prairie voles compared to pair-housed animals, and increased HR and reduced HRV when compare to pre-isolation values (Figure 1). The ANOVA for HR yielded a non-significant main effect of time [F(2,45) = 3.060, p = 0.057], but a significant main effect of group [F(1,45) = 4.147, p = 0.048], and a group by time interaction [F(2,45) = 5.941, p = 0.005]. The HR of the two groups did not differ during the baseline (p > 0.05) or social bonding period (p > 0.05). However, during the isolation period, HR in the isolated group was higher than its respective HR during social bonding with the female partner [t(8) = 5.901, p = 0.000] and that of the paired group [t(15) = 3.392, p = 0.004].

Figure 1.

Mean (+ SEM) HR in prairie voles at baseline, following 5 days of social bonding, and following 5 days of social isolation or continued pairing. *P < 0.05 versus respective paired value; #p < 0.05 versus respective baseline value.

The ANOVA for SDNN index yielded no significant main effects of group (p > 0.05), time (p > 0.05), or group by time interaction (p > 0.05). The ANOVA for RSA amplitude yielded no significant main effects of group (p > 0.05) time (p > 0.05), or group by time interaction (p > 0.05). No follow-up comparisons were conducted (data not shown).

3.1.3. Learned Helplessness

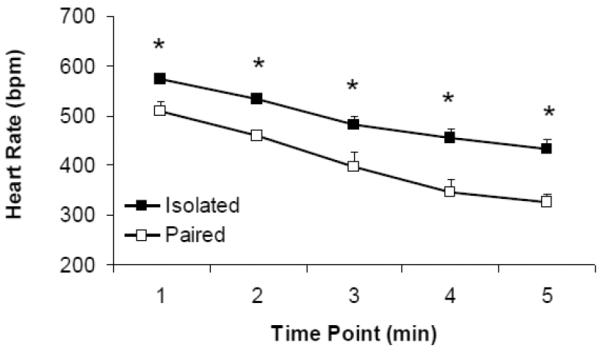

Social bond disruption altered depressive behaviors, and resulted in a significant increase in HR in isolated male prairie voles during the FST (Figure 2). Isolated animals exhibited relatively higher immobility levels (92.7 ± 21.0 seconds) than paired animals (40.6 ± 15.3 seconds; t(14) = 2.069, p = 0.058]. The ANOVA for HR during the FST yielded significant main effects of group [F(1,49) = 42.702, p = 0.000] and time [F(4,49) = 20.544, p = 0.000], but no significant group by time interaction (p > 0.05). Between-group minute-by-minute comparison indicated that the isolated group exhibited a higher HR than the paired group across all 5 time points: (a) minute 1 [t(1,9) = 2.890, p = 0.018]; (b) minute 2 [t(1,10) = 3.659, p = 0.004]; (c) minute 3 [t(1,9) = 2.593, p = 0.029]; (d) minute 4 [t(1,11) = 3.347, p = 0.007]; and (e) minute 5 [t(1,10) = 2.799, p = 0.019]. The ANOVA for SDNN index yielded non-significant main effects of group (p > 0.05) and time (p > 0.05), and no group by time interaction (p > 0.05; data not shown). Comparisons of cardiac data 3 hours following the FST indicated no differences in HR (p > 0.05) or SDNN index (p > 0.05) between the paired and isolated groups (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Mean (+ SEM) HR in paired and isolated prairie voles during the 5-minute FST. *P < 0.05 versus respective paired value. Note: the HR decrease in both groups corresponds to a decrease in body temperature across the 5-minute swim period.

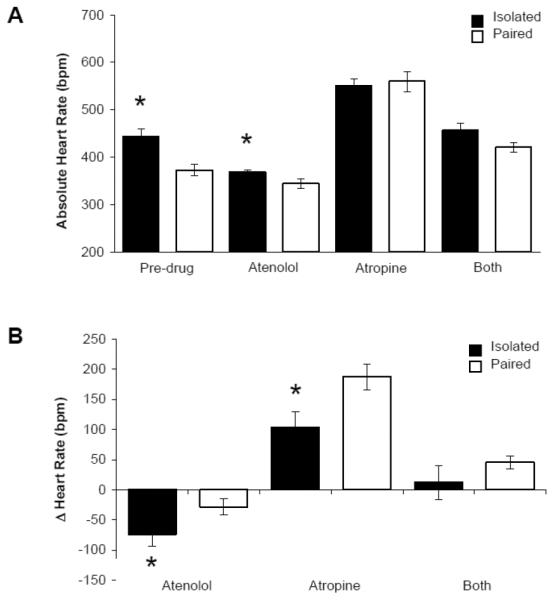

3.1.4. Autonomic Nervous System Function

Social bond disruption resulted in autonomic imbalance characterized by increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic drive to the heart, compared to paired animals (Figure 3). Prior to administration of the autonomic nervous system receptor antagonists, the isolated group displayed a significantly elevated HR relative to the paired group [t(15) = 3.392, p = 0.004].

Figure 3.

Mean (+ SEM) absolute HR (Panel A) and change in HR from pre-drug values (Panel B) in paired and isolated prairie voles prior to and during autonomic receptor antagonism with atenolol, atropine methyl nitrate, and a combination of both drugs. *P < 0.05 versus respective paired value.

The ANOVA for absolute HR values, relative to pre-drug HR values, yielded a main effect of drug treatment [F(3,53) = 87.734, p = 0.000] and a drug treatment by group interaction [F(3,53) = 4.408, p = 0.008]. Following atenolol administration, absolute HR was significantly greater in the isolated group versus the paired group [t(14) = 2.169, p = 0.048]. However, isolated prairie voles displayed a greater reduction in HR (from pre-drug values) versus paired animals [t(1,14) = 2.292, p = 0.038]. Following atropine administration, absolute HR did not differ between paired and isolated groups (p > 0.05). However, isolated prairie voles exhibited an attenuated increase in HR (from pre-drug values) versus paired animals [t(1,13) = 3.190, p = 0.007]. There were no significant differences in absolute HR or change from pre-drug values between paired and isolated groups following dual autonomic blockade (p > 0.05 for both comparisons).

3.2. Experiment 2

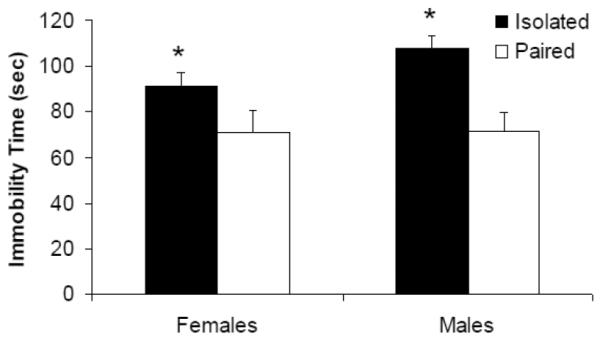

3.2.1. Learned Helplessness

Social bond disruption resulted in an increase in depressive behaviors in both male and female isolated groups, compared to paired males and females; however no sex difference was observed (Figure 4). The ANOVA for immobility yielded a main effect of group [F(1,36) = 43.069, p = 0.000], but no significant main effect of sex (p > 0.05) or group by sex interaction (p > 0.05). Given the lack of a significant interaction, males and females were collapsed for the purposes of pairwise comparisons. Isolated animals displayed significantly more immobility during the FST versus paired animals [t(38) = 6.354, p = 0.000].

Figure 4.

Mean (+ SEM) immobility time in male and female paired and isolated prairie voles during the 5-minute FST. *P < 0.05 versus respective paired value.

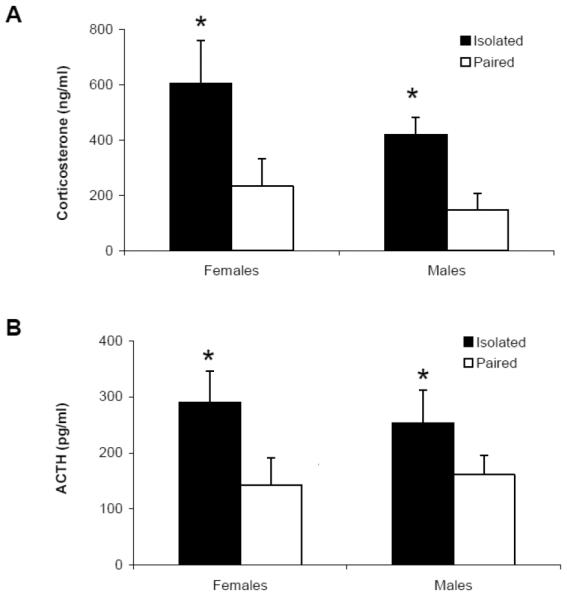

3.2.2. Circulating Hormones

Social bond disruption resulted in elevated levels of both ACTH and corticosterone in males and females, versus paired animals (Figure 5). A sex difference was not observed in either ACTH or corticosterone levels. The ANOVA for ACTH levels yielded a main effect of group [F(1,36) = 5.801, p = 0.024], but no significant main effect of sex (p > 0.05) or group by sex interaction (p > 0.05). Males and females were collapsed for the purposes of pairwise comparisons. Isolated animals displayed significantly greater levels of ACTH than paired animals [t(28) = 2.65, p = 0.006].

Figure 5.

Mean (+ SEM) ACTH (Panel A) and corticosterone (Panel B) levels in male and female paired and isolated prairie voles 10 minutes following the 5-minute FST. *P < 0.05 versus respective paired value.

The ANOVA for corticosterone levels yielded a main effect of group [F(1,36) = 10.192, p = 0.004], but no significant main effect of sex (p > 0.05) or group by sex interaction (p > 0.05). Males and females were collapsed for the purposes of pairwise comparisons. Isolated animals displayed significantly greater levels of corticosterone than paired animals [t(28) = 3.11, p = 0.002].

4. Discussion

The disruption of social bonds can have significant effects on psychological and cardiovascular health. The current series of experiments used the prairie vole model to investigate the behavioral and physiological consequences resulting from the disruption of established social bonds between mated pairs. The present experiments focused on prairie voles because these animals display a number of analogous social behaviors to humans and are an excellent translational model for investigating the influence of social experiences on health (Getz, & Hofmann, 1986; Williams et al., 1992; Grippo et al., 2007c; Roberts et al., 1998). The present studies demonstrate that the disruption of a pair bond produces behavioral disturbances associated with depression and cardiac dysfunction, coupled with indices of both neuroendocrine and autonomic dysregulation.

The findings from these experiments provide insight into negative emotional consequences of disrupted social bonds. The assessment of learned helplessness during the FST was investigated due to its relevance to the relationship between depression and ineffective coping styles (Lazarus, 2006). Both male and female prairie voles displayed an increase in passive behavioral responding during the FST, which has been described as a valid operational measure of learned helplessness or behavioral despair (Cryan et al., 2005; Bielajew et al., 2003). The behavioral results from both males and females show the same pattern; isolated animals displayed increased helpless behaviors (immobility) compared to paired animals. The disruption of established social bonds in prairie voles adversely influences behavioral reactivity to a stressor, predisposing them to depressive behaviors. These results are consistent with previous findings from both long-term (Grippo et al., 2007c) and short-term (Bosch et al., 2009) social isolation in prairie voles, and studies of social stressors in both men and women (see Kiecolt-Glaser, & Newton, 2001; Phillipson, 1997; Rehman et al., 2008).

In addition to inducing depression-relevant behaviors, the disruption of an established social bond produces changes in both resting and stressor-induced HR. In Experiment 1, male prairie voles displayed a significantly higher resting HR after the loss of a female partner, compared to pre-isolation values and paired control animals. These findings are in line with previous studies of the cardiovascular consequences of long-term social isolation in prairie voles (Grippo et al., 2007c; Grippo et al., 2011). Interestingly, in the present study, the disruption of a social bond between mated prairie vole pairs produced a significant elevation in HR much earlier (after 5 days) than in previous studies that have investigated the effects of disrupting family bonds in this species (after 2–4 weeks; Grippo et al., 2007c). However, in contrast to HR alterations, HRV was not significantly affected by 5 days of social bond disruption in the present study. This is consistent with previous data indicating that 2–4 weeks of disruption of a family bond was necessary to produce a reduction in HRV (Grippo et al., 2007c). Five days of social isolation from either family members or mated partners is not sufficient to induce significant HRV alterations.

In addition to an elevation of HR during resting periods, HR also was increased in isolated male prairie voles during the FST. Compared to pair-housed control animals, the isolated animals displayed a significantly higher HR across the 5-minute swim period. Our laboratory was the first to characterize cardiac variables during the FST in prairie voles, showing that long-term social isolation in females is associated with increased HR, reduced HRV, and arrhythmias during this behavioral stressor (Grippo et al., 2012). The present findings shed further light on the integration of behavioral and physiological reactions to stress in this species. Isolated prairie voles are more reactive to the stress of the FST, and are unable to regulate their physiological state as well as pair-housed animals. In particular, it is notable that, while isolated prairie voles were less active than their paired counterparts during the FST (i.e., displaying higher rates of immobility), this group exhibited an exaggerated cardiac response to the stressor. These findings therefore suggest that an inability to maintain appropriate cardiovascular control during periods of stress may influence cardiac morbidity and mortality in depressed individuals.

The resting and stressor-associated cardiac dysfunction may be mediated by autonomic dysregulation. Compared to pair-housed control animals, isolated male prairie voles displayed autonomic nervous system disturbances, characterized by increased sympathetic and decreased parasympathetic innervation to the heart. This imbalance of autonomic regulation contributed to the increased HR observed during the isolation period and during the FST, but did not appear to influence HRV. An imbalance of autonomic cardiac control has been reported in both CVD and depression in humans (Carney et al., 2005; Udupa et al., 2007), and in animal models (Grippo et al., 2002; Grippo et al., 2007c). An increase in sympathetic drive coupled with a decrease in parasympathetic drive contributes to morbidity and mortality from CVD (Carney et al., 2001; Carney et al., 2008; Cheng et al., 2003). The present findings suggest that social support from a partner can be protective against autonomic imbalance and associated HR dysfunction.

The disruption of social bonds also influences neuroendocrine regulation. In Experiment 2, both male and female isolated groups exhibited increased circulating concentrations of ACTH and corticosterone following the FST, when compared to their respective pair-housed controls. These findings are in line with Bosch et al. (2009), who reported increased corticosterone and depression-relevant behaviors following male-female social bond disruption. The lack of a sex difference in HPA axis reactivity to a short-term stressor in the present study indicates that both males and females are sensitive to the loss of a socially-bonded partner. Similarly, studies with humans suggest that various forms of morbidity and mortality are influenced by social stress in both sexes (for instance, Kiecolt-Glaser, & Newton, 2001; Steptoe et al., 2013).

When the findings from Experiments 1 and 2 are considered together, they suggest that the loss of a socially-bonded partner has significant negative consequences for behavior, stress reactivity, neuroendocrine function, and autonomic regulation of the heart. These consequences might represent an evolutionary adaption favoring monogamy through adverse responses to separation, encouraging an organism to remain with a social partner or reconnect with its missing partner. Two parents remaining together - and thus providing for the offspring - would be adaptive, and increase the survival of the progeny (Carter, 1998).

The findings from the present experiments inform our understanding of mechanisms by which social stress deleteriously influences behavioral and physiological processes. Indeed, an inability to adequately cope with stressors has been shown to adversely affect several behavioral and physiological functions, and is observed in humans suffering from depression and CVD (Cryan et al., 2005; Sapolsky, 1996; Porges, 2009; Thayer, & Brosschot, 2005). Alterations in central nervous system functioning may explain the current findings and additional negative responses to stress, biasing an organism toward more passive behavioral strategies and visceral regulation (Bielajew et al., 2003; Cryan et al., 2005). Behavior and biological function are theorized to form a circuit involving cortical direction of brainstem nuclei responsible for control of autonomic efferent projections (Thayer, & Brosschot, 2005). When this cortical-subcortical circuit is disrupted - for instance via social stress - it can produce a corresponding withdrawal of parasympathetic regulation of the heart (Porges, 2009). The resulting change in autonomic regulation is associated with increased basal HR, heart rhythm dysfunction, an excess of sympathetic drive, and behavioral despair (Grippo et al., 2010; Grippo, & Johnson, 2009; Pieper, & Brosschot, 2005).

In addition to altering autonomic nuclei, chronic stress has been shown to differentially affect key neuronal structures involved in the stress response (e.g., decreased dendritic arborization in the hippocampus and increased dendritic arborization in the amygdala; Vyas et al., 2002). Likewise, high levels of circulating stress hormones such as corticosterone are linked with adverse behavioral and health consequences (McEwen, 2003; Sapolsky, Romero, et al., 2000). HPA axis hyperactivity to stressors and latency in returning to basal levels of HPA functioning may be facilitated by morphological or functional changes in neuronal structures that regulate the stress response. The social stress-induced changes observed in the present experiments highlight the interrelatedness of physiological and psychological states with an organism's social environment. The disruption of established social bonds may therefore adversely affect processes responsible for maintaining appropriate regulatory activity in the brain.

The social disruption of losing a partner negatively influences physiological and behavioral functioning in socially monogamous prairie voles. This research is important in the context of humans suffering from social isolation and other forms of social stress which often result in negative consequences such as depression, poor stress coping, HR and rhythm dysfunction, and autonomic imbalance (Sapolsky, 1996; Sapolsky et al., 2000; Ramsay et al., 2008; Uchino et al., 1999). Future studies will benefit from focusing on long-term structural and functional changes in brain regions that regulate social behavior, stress reactivity, and autonomic and endocrine function. Additional studies with socially monogamous rodents will inform new treatment strategies to improve the quality of life for individuals who experience negative health consequences from partner loss or loneliness.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants MH77583 and HL112350 (AJG), HL-108475 (M-ALS), and funding from Northern Illinois University. The authors would like to thank Stephanie Allen, Christina Bishop, Deirdre Clarke, Parag Davé, Vitoria McDaniel, Brett Pinkepank, Kristin Preihs, and Loren Weese for assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- American Heart Association Cardiovascular Disease Statistics. 2011 Online, http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml?identifier=4478.

- Aragona BJ, Liu Y, Curtis JT, Stephan FK, Wang Z. A critical role for nucleus accumbens dopamine in partner-preference formation in male prairie voles. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3483–3490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03483.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bales KL, Kramer KM, Lewis-Reese AD, Carter CS. Effects of stress on parental care are sexually dimorphic in prairie voles. Physiol. Behav. 2006;87:424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barger SD. Social integration, social support, and mortality in the US National Health Interview Survey. Psychosom. Med. 2013;75:510–517. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318292ad99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielajew C, Konkle ATM, Kentner AC, Baker SL, Stewart A, Hutchins AA, Santa-Maria Barbagallo L, Fouriezos G. Strain and gender specific effects in the forced swim tests: effects of previous stress exposure. Stress. 2003;6:269–280. doi: 10.1080/10253890310001602829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG. Social support and mortality in an elderly community population. Am. J. of Epidemiol. 1982;115:684–694. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch OJ, Nair HP, Ahern TH, Neumann ID, Young LJ. The CRF system mediates increased passive stress-coping behavior following the loss of a bonded partner in a monogamous rodent. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1406–1415. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg MM, Edmondson D, Shimbo D, Shaffer J, Kronish IM, Whang W, Alcántara C, Schwartz JE, Muntner P, Davidson KW. The `perfect storm' and acute coronary onset: Do psychosocial factors play a role? Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2013;55:601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne EA, Fleg JL, Vaitkevicius PV, Wright J, Porges SW. Role of aerobic capacity and body mass index in the age-associated decline in heart rate variability. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996;81:743–50. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.2.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspect. Biol. Med. 2003;46:39–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo S, Cacioppo JT. Decoding the invisible forces of social connections. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 2012;6:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Freedland KE. Depression, mortality, and medical morbidity in patients with coronary heart disease. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Blumenthal JA, Stein PK, Watkins L, Catellier D, Berkman LF, Czajkowski SM, O'Connor C, Stone PH, Freedland KE. Depression, heart rate variability, and acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:2024–2028. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Freedland KE, Veith RC. Depression, the autonomic nervous system, and coronary heart disease. Psychosom. Med. 2005;67:29–33. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000162254.61556.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carney RM, Steinmeyer B, Freedland KE, Blumenthal JA, Stein PK, Steinhoff WA, Howells WB, Berkman LF, Watkins LL, Czajkowski SM, Domitrovich PP, Burg MM, Hayano J, Jaffe AS. Nighttime heart rate and survival in depressed patients post acute myocardial infarction. Psychosom. Med. 2008;70:757–763. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181835ca3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS. Neuroendocrine perspectives on social attachment and love. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;238:799–818. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS. Is there a neurobiology of good welfare? In: Broom DM, editor. Coping with challenge: Welfare in animals including humans. Dahlem University Press; Berlin, Germany: 2001. pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng YJ, Lauer MS, Earnest CP, Church TS, Kampert JB, Gibbons LW, Blair SN. Heart rate recovery following maximal exercise testing as a predictor of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in men with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2052–2057. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.7.2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Valentino RJ, Lucki I. Assessing substrates underlying the behavioral effects of antidepressants using the modified rat forced swimming test. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;29:547–569. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing BS, Martin JO, Young LJ, Carter CS. The effects of peptides on partner preference formation are predicted by habitat in prairie voles. Horm. Behav. 2001;39:48–58. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing BS, Mogekwu N, Le WW, Hoffman GE, Carter CS. Cohabitation induced Fos immunoreactivity in the monogamous prairie vole. Brain Res. 2003;965:203–211. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)04199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R. Cytokine, sickness behavior, and depression. Neurol. Clin. 2006;24:441–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker MJ, Koper JW, van Aken MO, Pols HA, Hofman A, de Jong FH, Kirschbaum C, Witteman JC, Lamberts SW, Tiemeier H. Salivary cortisol is related to atherosclerosis of carotid arteries. J.Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:3741–3747. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries AC, DeVries BM, Taymans S, Carter CS. Modulation of pair bonding in female prairie voles (microtus ochrogaster) by corticosterone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:7744–7748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI. An empirical review of the neural underpinnings of receiving and giving social support: implications for health. Psychosom. Med. 2013;75:545–556. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31829de2e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, Masson A, Juneau M, Talajic M, Bourassa MG. Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101:1919–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Getz LL, Hofmann JE. Social organization in free-living prairie voles, microtus ochrogaster. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1986;18:275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Getz LL, Carter CS, Gavish L. The mating system of the prairie vole, Microtus ochrogaster: field and laboratory evidence for pair-bonding. Behav. Ecol.Sociobiol. 1981;8:189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Johnson AK. Stress, depression and cardiovascular dysregulation: a review of neurobiological mechanisms and the integration of research from preclinical disease models: review. Stress: Int. J. Biol. Stress. 2009;12:1–21. doi: 10.1080/10253890802046281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Carter CS, McNeal N, Chandler DL, LaRocca MA, Bates SL, Porges SW. 24-Hour autonomic dysfunction and depressive behaviors in an animal model of social isolation: implications for the study of depression and cardiovascular disease. Psychosom. Med. 2011;73:59–66. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31820019e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Cushing BS, Carter CS. Depression-like behavior and stressor-induced neuroendocrine activation in female prairie voles exposed to chronic social isolation. Psychosom. Med. 2007a;69:149–157. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802f054b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Cardiac regulation in the socially monogamous prairie vole. Physiol. Behav. 2007b;90:386–393. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Lamb DG, Carter CS, Porges SW. Social isolation disrupts autonomic regulation of the heart and influences negative affective behaviors. Biol.Psychiatry. 2007c;62:1162–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Moffitt JA, Johnson AK. Cardiovascular alterations and autonomic imbalance in an experimental model of depression. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002;282:1333–1341. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00614.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Moffitt JA, Sgoifo A, Jepson AJ, Bates SL, Chandler DL, McNeal N, Preihs K. The integration of depressive behaviors and cardiac dysfunction during an operational measure of depression: investigating the role of negative social experiences in an animal model. Psychosom. Med. 2012;74:612–619. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31825ca8e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo AJ, Sgoifo A, Mastorci F, McNeal N, Trahanas DM. Cardiac dysfunction and hypothalamic activation during a social crowding stressor in prairie voles. Auton. Neurosci. 2010;156:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hance M, Carney RM, Freedland KE, Skala J. Depression in patients with coronary heart disease: a 12-month follow-up. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 1996;18:61–65. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(95)00100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkelmann K, Moritz S, Botzenhardt J, Riedesel K, Wiedemann K, Kellner M, Otte C. Cognitive impairment in major depression: association with salivary cortisol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2009;66:879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsboer F, Von Bardeleben U, Gerken A, Stalla GK, Müller OA. Blunted corticotropin and normal cortisol response to human corticotropin-releasing factor in depression. N. Engl. J. Med. 1984;311:1127–1139. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410253111718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtveen JH, Rietveld S, de Geus EJC. Contribution of tonic vagal modulation of heart rate, central respiratory drive, respiratory depth, and respiratory frequency to respiratory sinus arrhythmia during mental stress and physical exercise. Psychophysiology. 2002;39:427–36. doi: 10.1017.S0048577202394022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychol.l Bull. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikusui T, Winslow JT, Mori Y. Social buffering: relief from stress and anxiety. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2006;361:2215–2228. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Stress and emotion: a new synthesis. Springer; New York, USA: 2006. pp. 101–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberwith C, Liu Y, Jia X, Wang Z. Social isolation impairs adult neurogenesis in the limbic system and alters behaviors in female prairie voles. Horm. Behav. 2012;62:357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Mood disorders and allostatic load. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54:200–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00177-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from disease, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- National Heart Lung and Blood Institute US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institute of Health Diseases and conditions index. 2009 Online, http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/dci/Diseases/Atherosclerosis/Atherosclerosis_WhatIs.html.

- Norman GJ, Hawkley L, Ball A, Berntson GG, Cacioppo JT. Perceived social isolation moderates the relationship between early childhood trauma and pulse pressure in older adults. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2013;88:334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth-Gomér K, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Lack of social support and incidence of coronary heart disease in middle-aged Swedish men. Psychosom. Med. 1993;55:37–43. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Liu Y, Young KA, Zhang Z, Wang Z. Post-weaning social isolation alters anxiety-related behavior and neurochemical gene expression in the brain of male prairie voles. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;454:67–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.02.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penninx BWJH, Beekman ATF, Honig A, Deeg DJH, Schoevers RA, van Eijk JTM, van Tilburg W. Depression and cardiac mortality: results from a community-based longitudinal study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2001;58:221–227. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peuler JD, Scotti MA, Phelps LE, McNeal N, Grippo AJ. Chronic social isolation in the prairie vole induces endothelial dysfunction: implications for depression and cardiovascular disease. Physiol. Behav. 2012;10(4):476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson C. Social relationships in later life: a review of the research literature. Int. J. of Geriatr. Psychiatry. 1997;12:505–512. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199705)12:5<505::aid-gps577>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper S, Brosschot JF. Prolonged stress-related cardiovascular activation: is there any? Ann. Behav. Med. 2005;30:91–103. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal perspective. Biol. Psychology. 2007;74:116–143. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, Heilman KJ, Bazhenova OV, Bal E, Doussard-Roosevelt JA, Koledin M. Does motor activity during psychophysiological paradigms confound the quantification and interpretation of heart rate and heart rate variability measures in young children? Devel. Psychobiol. 2007;49:485–494. doi: 10.1002/dev.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 2009;76:S86–S90. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW. Method and apparatus for evaluating rhythmic oscillations in aperiodic physiological response systems. US Patent Number 4520944. 1985 Apr 16; 1985.

- Porges SW, Bohrer RE. Analyses of periodic processes in psychophysiological research. In: Cacioppo JT, Tassinary LG, editors. Principles of Psychophysiology: Physical, Social, and Inferential Elements. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1990. pp. 708–53. [Google Scholar]

- Porges SW, Byrne EA. Research methods for measurement of heart rate and respiration. Biol. Psychology. 1992;324:93–130. doi: 10.1016/0301-0511(92)90012-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pournajafi-Nazarloo H, Partoo L, Yee J, Stevenson J, Sanzenbacher L, Kenkel W, Mohsenpour SR, Hashimoto K, Carter CS. Effects of social isolation on mRNA expression for corticotrophin-releasing hormone receptors in prairie voles. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36:780–789. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay S, Ebrahim S, Whincup P, Papacosta O, Morris R, Lennon L, Wannamethee SG. Social engagement and the risk of cardiovascular disease mortality: results of a prospective population-based study of older men. Ann. Epidemiol. 2008;18:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehman US, Gollan J, Mortimer AR. The marital context of depression: research, limitations, and new directions. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008;28:179–198. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RL, Williams JR, Wang AK, Carter CS. Cooperative breeding and monogamy in prairie voles: influence of the sire and geographical variation. Anim. Behav. 1998;55:1131–1140. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1997.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM. Stress, glucocorticoids, and damage to the nervous system: the current state of confusion. Stress. 1996;1:1–19. doi: 10.3109/10253899609001092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr. Rev. 2000;21:55–89. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.1.0389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott KM. Sex differences in the disability associated with mental disorders. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2011;24:331–335. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283477ad5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Crimmins E. Social environment effects on health and aging: integrating epidemiologic and demographic approaches and perspectives. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001;954:88–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steptoe A, Shankar A, Demakakos P, Wardle J. Social isolation, loneliness, and all-cause mortality in older men and women. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013;110:5797–5801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219686110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowe JR, Liu Y, Curtis JT, Freeman ME, Wang Z. Species differences in anxiety-related responses in male prairie and meadow voles: the effects of social isolation. Physiol. Behav. 2005;86:369–378. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer JF, Brosschot JF. Psychosomatics and psychopathology: looking up and down from the brain. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:1050–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J. Behav. Med. 2006;29:377–387. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchino BN, Uno D, Holt-Lunstad J. Social support, physiological processes, and health. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1999;8:145–148. [Google Scholar]

- Udupa K, Sathyaprabha TN, Thirthalli J, Kishore KR, Lavekar GS, Raju TR, Gangadhar BN. Alteration of cardiac autonomic functions in patients with major depression: a study using heart rate variability measures. J. Affect. Disord. 2007;100:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A, Mitra R, Roa BSS, Chattarji S. Chronic stress induces contrasting patterns of dendritic remodeling in hippcampal and amygdaloid neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:6810–6818. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06810.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JR, Catania KC, Carter CS. Development of partner preferences in female prairie voles (microtus ochrogaster): the role of social and sexual experience. Horm. Behav. 1992;26:339–349. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(92)90004-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yongue BG, McCabe PM, Porges SW, Rivera M, Kelley SL, Ackles PK. The effects of pharmacological manipulations that influence vagal control of the heart on heart period, heart period variability and respiration in rats. Psychophysiology. 1982;19:426–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1982.tb02499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young LJ, Wang Z. The neurobiology of pair bonding. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:1048–54. doi: 10.1038/nn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]