Abstract

Endothelial cell (EC) dysfunction is involved in the pathogenesis of contrast-induced acute kidney injury, which is a major adverse event following coronary angiography. In this study, we evaluated the effect of contrast media (CM) on human EC proliferation, migration, and inflammation, and determined if heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) influences the biological actions of CM. We found that three distinct CM, including high-osmolar (diatrizoate), low-osmolar (iopamidol), and iso-osmolar (iodixanol), stimulated the expression of HO-1 protein and mRNA. The induction of HO-1 was associated with an increase in NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) activity and reactive oxygen species (ROS). CM also stimulated HO-1 promoter activity and this was prevented by mutating the antioxidant responsive element or by overexpressing dominant-negative Nrf2. In addition, the CM-mediated induction of HO-1 and activation of Nrf2 was abolished by acetylcysteine. Finally, CM inhibited the proliferation and migration of ECs and stimulated the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 and the adhesion of monocytes on ECs. Inhibition or silencing of HO-1 exacerbated the anti-proliferative and inflammatory actions of CM but had no effect on the anti-migratory effect. Thus, induction of HO-1 via the ROS-Nrf2 pathway counteracts the anti-proliferative and inflammatory actions of CM. Therapeutic approaches targeting HO-1 may provide a novel approach in preventing CM-induced endothelial and organ dysfunction.

Keywords: radiocontrast media, endothelial cells, heme oxygenase-1, inflammation

1. Introduction

Intravascular injections of iodine-based contrast media (CM) are widely used in radiology for both diagnostic and interventional procedures such as enhanced X-ray imaging, computerized tomography, and coronary artery interventions. Despite their widespread and growing use in clinical medicine, CM can precipitate adverse effects that increase in-hospital and long-term complications. One of the most clinically important complications of coronary angiography is contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI), which is the third most common cause of hospital-acquired acute kidney injury [1]. CI-AKI is associated with several severe adverse events, including permanent renal impairment, increased mortality, recurrent ischemic events, and higher health care costs [2,3]. The pathophysiology underlying CI-AKI is complex, multifactorial, and not completely understood but a combination of endothelial dysfunction, renal tubular toxicity, and oxidative stress have been implicated in the pathogenesis of this disorder [4–8].

The endothelium is a crucial organ that regulates many aspects of vascular homeostasis, including vascular tone, coagulation, thrombosis, fibrinolysis, inflammation, and vascular permeability. Endothelial cells are transiently exposed to high concentrations of CM immediately after intravascular administration, and more persistently to low concentrations of CM as the diagnostic agents are gradually eliminated from the body. Clinical and experimental studies indicate that CM provokes endothelial dysfunction, reflected by alterations in cell viability, growth, and morphology [9–11]. CM inhibits endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS) expression and NO release, suppresses the endothelial synthesis of prostacyclin, and increases the generation of endothelin [12,13]. The alteration in the release of vasoactive factors by CM promotes renal vasoconstriction leading to renal medullary hypoxia and renal tubular failure. In addition, endothelial dysfunction negatively impacts the anti-thrombotic and anti-inflammatory property of the blood vessel wall and may further precipitate the development of systemic and organ-specific (e.g., renal, cardiac) complications.

Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) is an inducible enzyme that catalyzes the degradation of heme to carbon monoxide (CO), biliverdin, and free iron, with biliverdin subsequently being metabolized to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase [14,15]. Although initial interest in HO-1 focused on its ability to degrade heme, recent findings indicate that HO-1 serves as a key regulator of endothelial cell function. HO-1 is markedly induced by oxidative and nitrosative stress, and its induction in endothelial cells provides an important cellular defense mechanism against tissue injury [16–18]. In addition, HO-1 facilitates endothelial cell proliferation and migration, and impedes inflammatory responses in these cells [14,15,19]. Several studies have confirmed the protective role of HO-1 in several pathologic states, including CI-AKI [20]. However, the ability of HO-1 to influence CM-induced endothelial dysfunction is not known.

In the present study, we investigated the effect of three different types of CM on HO-1 gene expression in human endothelial cells. In addition, we determined the effect of distinct CM on the proliferation, migration, and inflammation of endothelial cells. Finally, we also assessed whether HO-1 modulates the biological actions of CM on endothelial cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents

Penicillin, gelatin, streptomycin, Nonidet P40, dithiothreitol, bromophenol blue, SDS, NaCl, EDTA, DMSO, glycerol, ethidium bromide, Triton X-100, heparin, trypan blue, agarose, trypsin, high-osmolar CM (HOCM) sodium diatrizoate, Tris, HEPES, and N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) were from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin A were from Roche Applied Sciences (Indianapolis, IN). M199 medium, bovine calf serum, lipofectamine, and 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2,7-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA) were from Life Technologies Corporation (Carlsbad, CA). Endothelial cell growth factor was from Becton Dickinson (Bedford, MA). Tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPPIX) was from Frontier Scientific (Logan, UT, USA). Human recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) was from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). A polyclonal antibody against HO-1 was from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) while antibodies against NF-E2-related factor-2 (Nrf2), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and β-actin were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). α-[32P]dCTP (3000Ci/mmol) and [3H]thymidine (90Ci/mmol) was from Amersham Life Sciences (Arlington Heights, IL). Low-osmolar CM (LOCM) iopamidol solution (Iopamiro-370) was from Bracco, Italy and iso-osmolar CM iodixanol solution (Visipaque-320) was from GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI.

2.2 Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Lonza Incorporated (Allendale, NJ) and serially cultured on gelatin-coated plates in M199 medium supplemented with 20% bovine calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 μg/ml endothelial cell growth factor, 90 μg/ml heparin, and 100 U/ml of penicillin and streptomycin. The human monocytic cell line U937 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was grown in suspension in RPMI-1640 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 2 mm L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/L glucose, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin. HUVEC and U937 cells were incubated in an atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.3 Western blotting

Cells were scrapped in lysis buffer (125 mM Tris [pH 6.8], 12.5% glycerol, 2% SDS, and bromophenol blue) and proteins separated by SDS-PAGE. Following transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, blots were blocked with PBS containing Triton X-100 (0.25%) and nonfat milk (5%) and then incubated with antibodies against HO-1 (1:1,500), Nrf2 (1:200), ICAM-1 (1:500), or β-actin (1:1000). Membranes were then washed, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, and developed with commercial chemoluminescence reagents (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). Protein expression was quantified by densitometry and normalized with respect to β-actin.

2.4 Northern blotting

Total RNA was loaded onto 1.2% agarose gels, fractionated by electrophoresis, and transferred to Gene Screen Plus membranes. Membranes were prehybridized in rapid hybridization buffer (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) and then incubated overnight at 68°C in hybridization buffer containing [32P]DNA probes (1 × 108 cpm) for HO-1, Nrf2, or 18S mRNA [21,22]. Following hybridization, membranes were washed, exposed to X-ray film, and mRNA expression quantified by densitometry and normalized with respect to 18 S rRNA.

2.5 HO-1 promoter analysis

HO-1 promoter activity was determined using HO-1 promoter/firefly luciferase constructs that were generously supplied by Dr. Jawed Alam (Ochsner Clinic Foundation, New Orleans, LA). These constructs consisted of the wild type enhancer (E1) that contains three antioxidant responsive elements (ARE) core sequences coupled to a minimum HO-1 promoter as well as the mutant enhancer (M739) that has mutations in its three ARE sequences. In some experiments, a plasmid expressing dominant-negative Nrf2 (dnNrf2) was employed. Transfection efficiency was controlled by introducing a plasmid encoding Renilla luciferase (Promega, Madison, WI) into cells. Cells were transfected with plasmids using lipofectamine (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), incubated for 48 h, and then exposed to CM for 8 h. Firefly luciferase activity was determined using a Glomax luminometer (Promega, Madison, WI) and normalized with respect to Renilla luciferase activity, and this ratio was expressed as fold induction over control cells.

2.6 Small interference RNA

HO-1 was silenced by transfecting cells with HO-1 small interference RNA (siRNA) (100nM) or a non-targeting (NT) siRNA (100nm) that was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO), as we previously described [21].

2.7 Nrf2 activation

Cells were incubated in lysis buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml aprotonin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.4% Nonidet P-40) for 10 minutes and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 3 minutes. Nuclear pellets were resuspended in extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 0.4 M NaCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μg/ml aprotonin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 10% glycerol), and centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 5 minutes. The supernatant containing nuclear protein was collected and Nrf2 activity determined by measuring the binding of Nrf2 to the ARE using an ELISA-based TransAM Nrf2 kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA). Nuclear extracts (5 μg) were incubated with ARE consensus site oligonucleotides (5′-GTCACAGTGACTCAGCAGAATCTG-3′) immobilized to 96-well plates. Bound protein was detected using an antibody specific to DNA-bound Nrf2, visualized by colorimetric reaction catalyzed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, and absorbance measured at 405 nm.

2.8 Measurement of intracellular ROS

ROS production was assessed by microscopy using the cell-permeable probe CM-H2-DCFDA. The dye (10μM) was preloaded to cells and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C. The cells were then washed with PBS twice and light protected before further analysis. The fluorescence images were obtained with a Bio-Rad Radiance 2000 confocal system coupled to an inverted microscope (Zeiss LSM 510; Carl Zeiss Incorporated, Thornwood, NY) at 200 × magnification using excitation and emission wavelengths of 480 nm and 520 nm, respectively. Mean fluorescence intensity per image was quantified by Image J analysis software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

2.9 Cell proliferation

Cells were seeded (2–5 × 104 cells) onto six-well plates in serum-containing media and grown overnight. After 24 hours, the cells were incubated with fresh culture media in the absence or presence of CM. Cell number determinations were made by dissociating cells with trypsin(0.05%):EDTA(0.53mM) and counting cells in a Beckman Z1 Coulter Counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

2.10 Cell migration

Cell migration was determined by using a scratch wound assay. Confluent cell monolayers were scraped with a pipette tip and injured monolayers incubated in the presence and absence of CM. Cell monolayers were photographed immediately and 20 hours after scratch injury, and the degree of wound closure determined by planimetry, as we previously described [23]

2.11 Monocyte adhesion

U937 cells were labeled with [3H]thymidine (1μCi/ml for 24 hours) and layered onto endothelial cell monolayers. Following a one hour incubation, non-adherent monocytes were removed and radioactivity associated with adherent monocytes quantified by scintillation spectrometry [21].

2.12 Statistical analyses

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed with the use of a Student’s two-tailed t-test and an analysis of variance with the Tukey post hoc test when more than two treatment regimens were compared. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

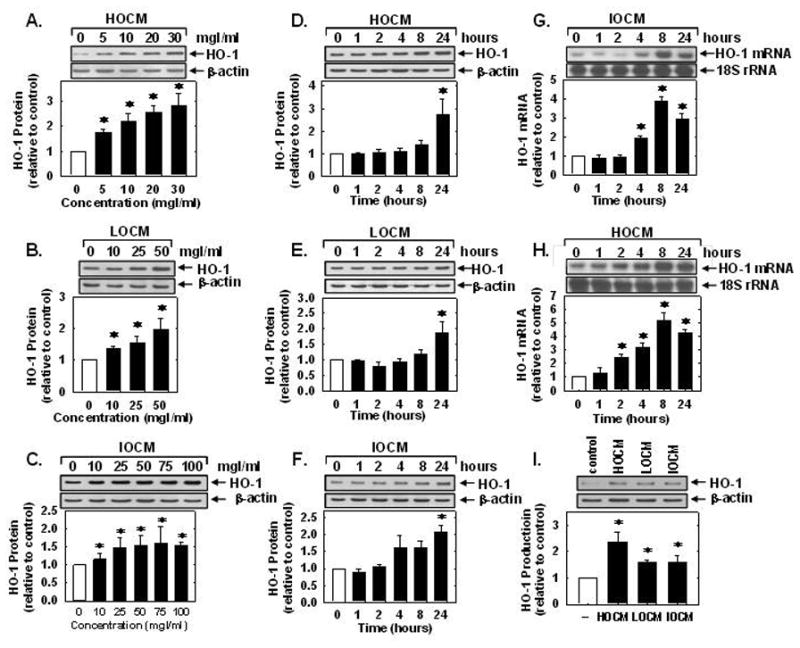

Treatment of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) with high-osmolar contrast media (HOCM, sodium diatrizoate), low-osmolar contrast media (LOCM, iopamidol) and iso-osmolar contrast media (IOCM, iodixanol), for 24 hours resulted in a concentration-dependent increase in HO-1 protein (Figure 1A, B, and C). At the same concentration of iodine, HOCM induced HO-1 protein expression more than LOCM, and LOCM more than IOCM. The maximum induction of HO-1 protein was 2.43-fold at 30 mgI/mL of HOCM, 1.73-fold at 50 mg iodine (I)/mL of LOCM, and 1.59-fold at 75 mgI/mL of IOCM. A significant increase in HO-1 protein was detected at 24 hours after CM exposure at these concentrations (Figure 1D, E, and F). The induction of HO-1 protein by CM was preceded by a rise in HO-1 mRNA expression (Figure 1G and H). A significant increase in HO-1 mRNA was first detected 2 to 4 hours after CM exposure and peaked at 8 hours (Figure 1G and H). Finally, to determine whether exposing endothelial cells to transiently high concentrations of CM induced HO-1 expression, HUVECs were treated with 250 mgI/mL of HOCM, LOCM or IOCM for 5 minutes. A significant increase in HO-1 protein was observed 24 hours following this exposure (Figure 1I).

Figure 1.

CM stimulated HO-1 expression in human endothelial cells. (A–C) Effect of CM concentration on HO-1 protein expression 24 hours after exposure to HOCM, LOCM, or IOCM. (D–F) Time-course of HO-1 protein expression following exposure to HOCM (30mgI/mL), LOCM (50mgI/mL), or IOCM (75mgI/mL). (G) Time-course of HO-1 mRNA expression after IOCM (50mgI/mL) exposure. (H) Time-course of HO-1 mRNA expression after HOCM (30mgI/mL) exposure. (I) Effect of short-term, high concentration (5 min at 250 mgI/mL) CM exposure on HO-1 protein expression 24 hours after CM exposure. HO-1 protein and mRNA expression was quantified by scanning laser densitometry and normalized with respect to β-actin and18S rRNA, respectively, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells (open bars). Results are means ± SEM (n=3–5). *Statistically significant effect of CM.

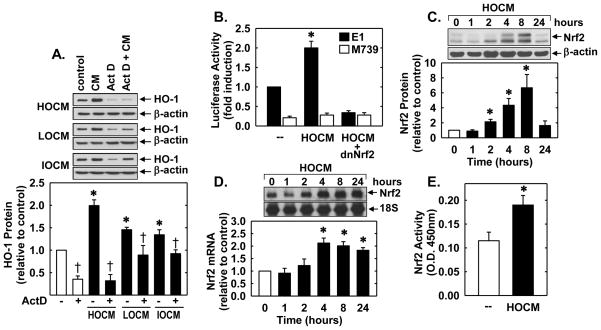

Incubation of HUVECs with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D abolished basal and CM-induced HO-1 protein expression (Figure 2A), suggesting that CM-mediated HO-1 expression required de novo RNA synthesis. To further examine the molecular mechanism by which CM stimulates HO-1 expression, HUVEC were transfected with an HO-1 promoter construct and reporter activity was monitored. Treatment of the HUVECs with HOCM stimulated an increase in HO-1 promoter activity that was abolished by mutating the antioxidant responsive element (ARE) sequences in the promoter (Figure 2B). Mutation of the ARE sequences also reduced basal promoter activity. Since the transcription factor Nrf2 plays a major role in ARE-mediated gene activation [24], we investigated whether Nrf2 contributed to the activation of HO-1 by CM. Transfection of the HUVECs with a dominant-negative mutant Nrf2 (dnNrf2) that had its activation domain deleted inhibited basal promoter activity and the CM-mediated elevation in HO-1 promoter activity (Figure 2B). In addition, HOCM evoked a significant increase in Nrf2 protein and mRNA beginning 2 and 4 hours, respectively, after CM exposure (Figure 2C and D). HOCM also stimulated the activation of Nrf2, as reflected by the increase in binding of nuclear Nrf2 to the ARE (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

CM stimulated HO-1 promoter activity via the Nrf2/ARE complex in human endothelial cells. (A) CM-mediated HO-1 gene expression required de novo RNA synthesis. Effect of actinomycin D (ActD; 0.05–0.10μg/ml) on CM (HOCM 30mgI/mL, LOCM 50mgI/mL, or IOCM 75mgI/mL for 24 hour)-mediated increase in HO-1 protein. (B) HOCM stimulated HO-1 promoter activity. Cells were transfected with a HO-1 promoter construct (E1) or a mutated HO-1 promoter construct (M739) and a Renilla luciferase construct, treated with HOCM (30mgI/mL for 8 hour), and then analyzed for luciferase activity. In some instances, a dominant-negative Nrf2 (dnNrf2) construct was co-transfected into the cells. (C) Time-course of Nrf2 protein expression after administration of HOCM (30mgI/mL). (D) Time-course of Nrf2 mRNA expression after administration of HOCM (30mgI/mL). (E) CM stimulated Nrf2 activity. Cells were treated with HOCM (30mgI/ml) for 8 hours and nuclear extracts analyzed for Nrf2 binding by ELISA. O.D., optical density. Protein and mRNA expression was quantified by scanning laser densitometry and normalized with respect to β-actin and 18 S rRNA, respectively, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells (open bars). Results are means ± SEM (n=3–5). *Statistically significant effect of CM. †Statistically significant effect of ActD.

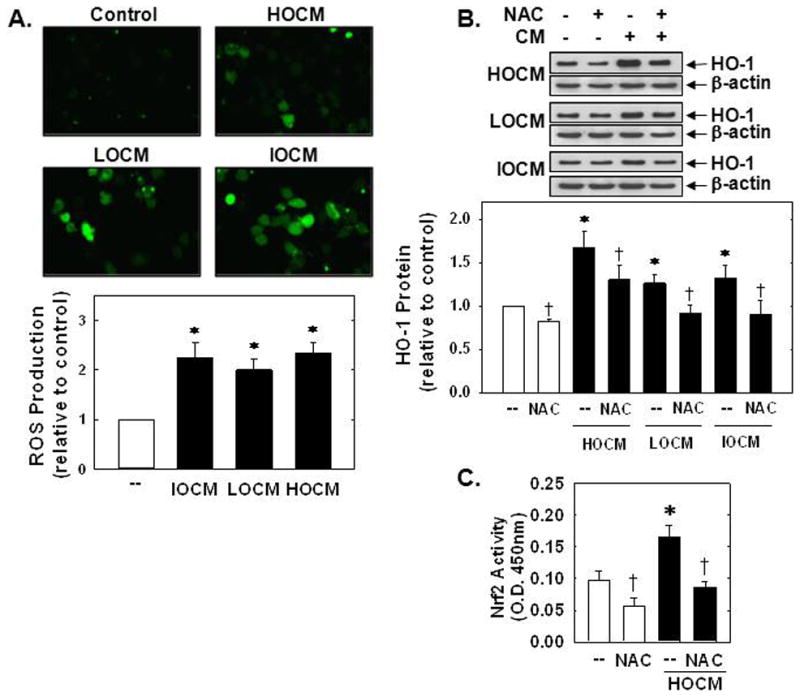

In subsequent experiments, we determined the upstream signaling pathway that stimulated HO-1 expression. Since oxidative stress has been implicated in the activation of Nrf2 [24], the contribution of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the induction of HO-1 was investigated. Incubation of HUVEC with any of the three contrast agents evoked a significant rise in ROS production (Figure 3A). Moreover, pretreatment of HUVEC with the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC;10 mM) blocked the increase in HO-1 protein expression and Nrf2 activation by CM (Figure 3B and C).

Figure 3.

CM-induced HO-1 expression was dependent on oxidative stress. (A) Representative images of the fluorescence of the ROS-sensitive dye CM-H2DCFDA in human endothelial cells after exposure to CM (HOCM 30mgI/mL, LOCM 50mgI/mL, or IOCM 75mgI/mL) for 24 hours. (B) Effect of N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC; 10mM) on CM (HOCM 30mgI/mL, LOCM 50mgI/mL, or IOCM 75mgI/mL for 24 hour) -mediated HO-1 protein expression. (C) Effect of NAC (10mM) on HOCM (30mgI/mL for 8 hour)-mediated Nrf2 activation. O.D., optical density. HO-1 protein expression was quantified by scanning laser densitometry and normalized with respect to β-actin, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells (open bars). Results are means ± SEM (n=3–6). *Statistically significant effect of CM. †Statistically significant effect of NAC.

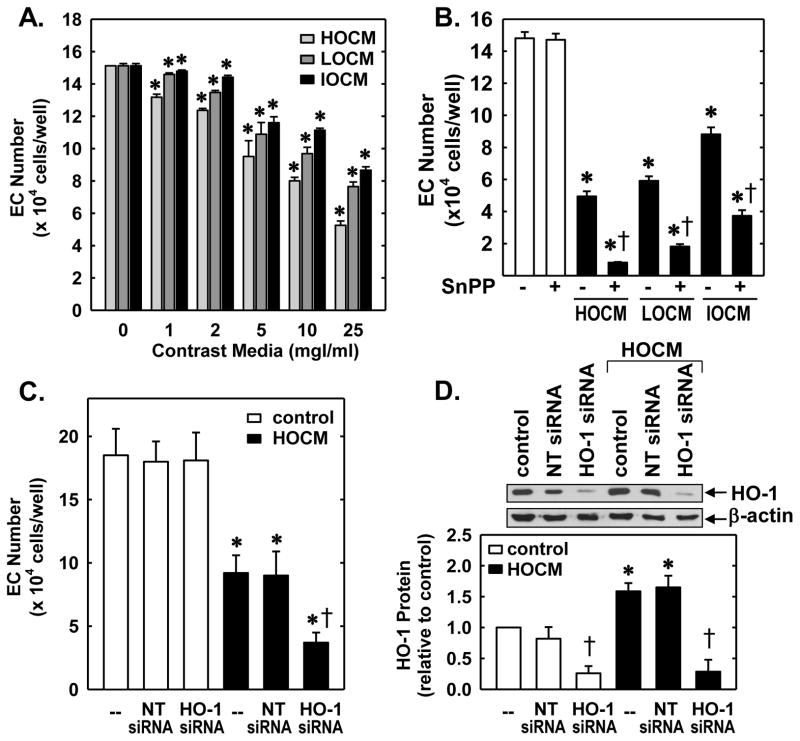

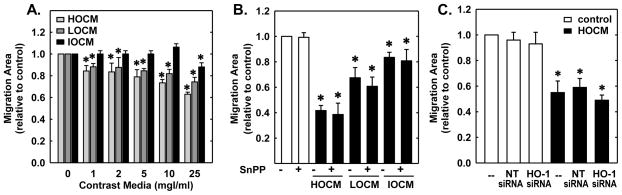

Next, the functional significance of the induction of HO-1 by CM was investigated. Treatment of HUVEC with HOCM, LOCM, or IOCM inhibited endothelial cell growth in a concentration-dependent manner without affecting endothelial cell viability (Figure 4A). HOCM exhibited the greatest anti-proliferative effect, but all three CM were effective inhibitors of cell growth with inhibitory actions observed at concentrations as low as 1mgI/mL. Interestingly, administration of the HO-1 inhibitor, SnPPIX (10μmol/L) markedly increased the anti-proliferative action of all three CM (Figure 4B). Alone, SnPPIX had no effect on cell proliferation. Similarly, transfection of HUVEC with HO-1 siRNA (100nM) potentiated the anti-proliferative effects of HOCM whereas a non-targeting (NT) siRNA had no effect (Figure 4C). In the absence of contrast agents, HO-1 or NT siRNA failed to influence cell growth. Transfection of HUVEC with HO-1 siRNA abolished basal and CM-induced HO-1 (Figure 4D). In contrast, the NT siRNA had no effect on HO-1 protein expression, confirming the efficacy and specificity of the HO-1 knockdown approach. Aside from inhibiting cell growth, all three contrast agents significantly retarded the migration of HUVEC in a concentration-dependent fashion (Figure 5A). However, pharmacological inhibition of HO-1 activity (Figure 5B) or silencing HO-1 expression (Figure 5C) failed to modify the anti-migratory action of the CM.

Figure 4.

CM-induced inhibition of human endothelial cell (EC) proliferation was attenuated by HO-1. (A) CM inhibited EC proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. (B) HO-1 inhibition potentiated CM-mediated inhibition of EC proliferation. Cells were treated with HOCM, LOCM or IOCM (25mgI/mL) in the presence or absence of the HO-1 inhibitor SnPPIX (10μM). (C) HO-1 silencing potentiated CM-mediated inhibition of cell proliferation. Cells transfected with HO-1 siRNA (0.1μM) or non-targeting (NT) siRNA (0.1μM) were exposed to HOCM (25mgI/mL) for two days. (D) HO-1 protein expression in cells transfected with HO-1 siRNA (0.1μM) or NT siRNA (0.1μM) and exposed to HOCM (25mgI/ml) for 24 hours. HO-1 protein was quantified by scanning densitometry, normalized with respect to β-actin, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells (open bars). Results are means ± SEM (n=3–6). *Statistically significant effect of CM. †Statistically significant effect of HO-1 inhibition or silencing.

Figure 5.

CM inhibited the migration of human endothelial cells. (A) CM exposure for 20 hours inhibited cell migration in a concentration-dependent manner. (B) HO-1 inhibition had no effect on CM-mediated inhibition of cell migration. Cells were treated with HOCM, LOCM or IOCM (25mgI/mL) for 20 hours in the presence or absence of the HO-1 inhibitor SnPPIX (10μM). (C) HO-1 silencing had no effect on CM-mediated inhibition of cell migration. Cells transfected with HO-1 siRNA (0.1μM) or non-targeting (NT) siRNA (0.1μM) were exposed to HOCM (25mgI/mL) for 20 hours. Results are means ± SEM (n=3–5). *Statistically significant effect of CM.

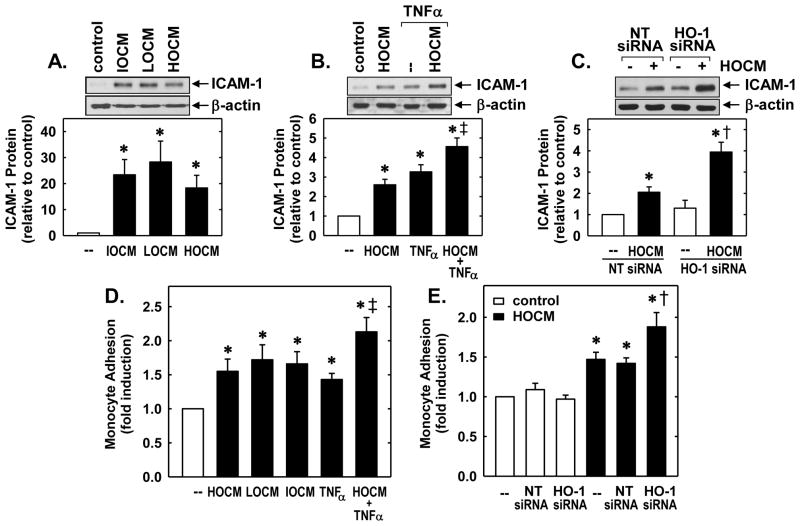

Finally, since inflammation has been implicated in CM-induced organ dysfunction [2], we explored the ability of CM to evoke inflammatory responses in endothelial cells. Treatment of HUVEC with HOCM, LOCM, or IOCM stimulated a pronounced increase in ICAM-1 expression (Figure 6A). Moreover, CM increased the induction of ICAM-1 by a low concentration of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα; 1ng/ml) (Figure 6B). Interestingly, knockdown of HO-1 further elevated the expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) by HOCM (Figure 6C). Incubation of HUVEC with HOCM, LOCM, or IOCM also stimulated a significant increase in monocyte adhesion and augmented the adhesive response of HUVEC to TNFα (Figure 6D). Moreover, HO-1 siRNA increased the ability of HOCM to stimulate monocyte adhesion while a NT siRNA had no effect (Figure 6D). In the absence of CM, neither HO-1 nor NT siRNA modified monocyte binding to HUVEC.

Figure 6.

CM-induced inflammatory responses in human endothelial cells were attenuated by HO-1. (A) CM exposure (HOCM 30mgI/mL, LOCM 50mgI/mL or IOCM 75mgI/mL) for 24 hours stimulated ICAM-1 protein expression. (B) CM enhances tumor necrosis factor (TNFα)-mediated ICAM-1 protein expression. Cells were treated with HOCM (30mgI/ml) in the presence and absence of TNFα (1ng/ml) for 24 hours. (C) HO-1 silencing potentiated CM-mediated ICAM-1 expression. Cells transfected with HO-1 siRNA (0.1μM) or non-targeting (NT) siRNA (0.1μM) were exposed to HOCM (30mgI/mL) for 24 hours. (D) CM exposure (HOCM 30mgI/mL, LOCM 50mgI/mL or IOCM 75mgI/mL) for 24 hours stimulated monocyte adhesion. Cells were treated with CM in the presence and absence of TNFα (1ng/ml). (E) HO-1 silencing potentiated CM-mediated ICAM-1 expression. Cells transfected with HO-1 siRNA (0.1μM) or NT siRNA (0.1μM) were exposed to HOCM (30mgI/mL) for 24 hours. ICAM-1 protein was quantified by scanning densitometry, normalized with respect to β-actin, and expressed relative to that of control, untreated cells (open bars). Results are means ± SEM (n=3–5). *Statistically significant effect of CM or TNFα. ‡Statistically significant effect of HOCM+TNFα compared to either treatment alone. †Statistically significant effect of HO-1 silencing.

4. Discussion

In the present study, we identified CM as a novel inducer of HO-1 gene expression in human vascular endothelium. The induction of HO-1 is dependent on the type and concentration of CM, requires the production of ROS, and is mediated by the Nrf2-ARE complex. In addition, we found that CM suppresses the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells and elicits inflammatory responses in these cells. Moreover, we demonstrated that the induction of HO-1 counteracts the anti-proliferative and inflammatory actions of CM. Thus, therapeutic strategies directed at HO-1 represent a promising approach in preserving endothelial function and limiting clinical complications associated with the use of CM.

Treatment of endothelial cells with three different iodine-based CM that possess distinct physicochemical properties stimulates the expression of HO-1. The induction of HO-1 is dependent on the type, concentration, and duration of CM exposure, with HOCM being the most potent inducer. Prolonged incubation (hours) of endothelial cells with low concentrations of CM (5–10μM) that are readily attained and persist in the plasma during coronary angiograms are sufficient to induce HO-1 expression. Furthermore, brief exposure (minutes) to high concentrations of CM (250μM) that are transiently found in the circulation shortly after CM administration are also able to stimulate HO-1 expression [25]. Thus, exposure to chronic low or acute high concentrations of CM that are observed clinically stimulates HO-1 expression in vascular endothelium.

The induction of HO-1 by CM is dependent on de novo RNA synthesis and is likely due to the transcriptional activation of the gene since transient luciferase reporter assays demonstrate that CM directly stimulates HO-1 promoter activity. The induction of HO-1 gene transcription requires the presence of AREs since mutation of this responsive element abrogates the stimulation of promoter activity by CM. While several transcription factors bind to AREs, Nrf2 plays a predominate role in ARE-dependent HO-1 gene expression [24]. In agreement with this, we found that CM increases Nrf2 protein and mRNA, and nuclear Nrf2 binding to the AREs. Interestingly, CM-induced increases in Nrf2 protein proceeds elevations in Nrf2 mRNA, suggesting that CM stimulates both the de novo synthesis and stability of the protein. Moreover, transfection of endothelial cells with a dominant-negative Nrf2 construct abrogates the activation of HO-1 promoter activity in response to CM. Thus, mobilization of Nrf2 plays an integral role in mediating HO-1 gene transcription by CM in endothelial cells and may underlie the induction of HO-1 observed in the renal cortex of rats treated with CM [20].

The ability of CM to stimulate HO-1 expression is dependent on oxidative stress. Incubation of endothelial cells with CM evokes a marked increase in ROS production. The elevation in oxidative stress is observed with all three CM and is likely related to the presence of iodine, which is a known inducer of ROS [26]; however, direct activation of ROS-generating enzymes may also be involved [27]. Importantly, the antioxidant NAC blocks the induction of HO-1 and the activation of Nrf2 by CM. Although the mechanism by which oxidative stress activates Nrf2 is not fully known, the oxidation of specific cysteine residues in Kelch-like erythroid cell-derived protein-1 (Keap1) has been implicated in the release and/or inhibition of Keap1-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of Nrf2 [28].

Previous work reported that brief, high-concentration CM exposure causes injury to endothelial cells and retards their subsequent growth[10,29–31]. In the present study, we demonstrate that prolonged exposure to clinically relevant, low concentrations of CM inhibits the proliferation of endothelial cells. Moreover, we also show for the first time that CM also blocks the migration of endothelial cells. The anti-proliferative and anti-migratory action of CM is observed in the absence of cell toxicity. A significant inhibition of endothelial cell proliferation and migration is detected even at very low concentrations of CM (1mgI/ml). This is of clinical concern, especially in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a diminished clearance capacity which would allow the CM to remain in the circulation at inhibitory concentrations for longer periods of time. The ability of CM to suppress endothelial cell growth and migration may hinder the restoration of endothelial integrity and function of injured blood vessels and adversely affect the vasomotor, coagulative, and thrombotic properties of the vessel wall.

Vascular endothelial cells also play a key role in the recruitment and infiltration of circulating inflammatory cells to sites of inflammation [32], which is involved in the initiation and progression of AKI. Endothelial dysfunction, especially of the vasa recta in the peritubular area of the kidney, initiate early inflammatory responses that result in infiltration of leukocytes including neutrophils, macrophages, natural killer cells, and lymphocytes. The recruited leukocytes lead to renal tubular injury via the generation of ROS. TNFα, which is chiefly released by macrophages, is greatly induced after ischemic and reperfusion insults and contributes to early kidney inflammation and injury [33]. Furthermore, leukocyte-endothelial interactions can cause activation of coagulation pathways resulting in impairment of microvascular blood flow and oxygen delivery to critical areas of the outer renal medulla or plaque [34,35]. In our study, we found that CM induces inflammatory responses in endothelial cells. Treatment of endothelial cells with any of the three CM stimulates the expression of ICAM-1, which plays a crucial role in recruiting inflammatory cells to sites of active inflammation and promoting their transmigration to the extravascular space [36]. In addition, CM enhances the ability of TNFα to elevate adhesion receptor expression. These findings are in-line with previous work showing that endothelial P-selectin expression is augmented by CM and that secretion of proinflammatory products is strongly stimulated by incubation of endothelial cells with iodixanol and TNF-α [37,38]. We also demonstrated that CM stimulates the adhesion of monocytes to endothelial cells and augments TNFα-mediated monocyte adhesion. Thus, CM is able to both initiate and promote inflammatory responses in endothelial cells. Given the central role of inflammation in renal disease and atherosclerosis, the inflammatory actions of CM may contribute to the development and progression of CI-AKI and exacerbate atherosclerotic complications in patients with coronary artery disease that undergo coronary angiograms.

Interestingly, the induction of HO-1 in endothelial cells functions in an adaptive manner to limit the anti-proliferative and inflammatory effects of CM. We found that HO-1 inhibition with SnPPIX or knockdown of HO-1 using a siRNA approach augments the anti-proliferative action of CM and enhances CM-mediated ICAM-1 expression and monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells. These findings indicate that the induction of HO-1 by CM counteracts its anti-proliferative and inflammatory actions on endothelial cells. These results are in agreement with earlier studies showing that HO-1 accelerates endothelial cell proliferation and impedes endothelial inflammation [19,39–41]. In contrast, the induction of HO-1 does not modulate the anti-migratory action of CM. Although HO-1 stimulates endothelial cell migration [39], inhibition or silencing of HO-1 had no effect on the ability of CM to repress cell migration. In this case, levels of HO-1 may be insufficient to modulate cell movement. In support, of this notion we previously reported that HO-1 reaction products are more effective regulators of vascular cell growth than migration [42]. Interestingly, inhibition of HO-1 activity or expression does not influence basal endothelial cell proliferation or migration. This may reflect the more limited expression of HO-1 observed in the absence of CM and the requirement for a threshold level of enzyme to affect endothelial cell properties.

Current strategies for preventing CM-induced organ pathologies are limited and related to pre-procedural use of hydration, bicarbonate, and NAC, which remain controversial [43]. However, HO-1 represents an attractive target in averting CM-associated complications. HO-1 blocks CI-AKI in rats and this is associated with a decline in renal cell apoptosis [20,44]. Additionally, the present study found that HO-1 counteracts the deleterious effects of CM on endothelial cell growth and inflammation. Furthermore, the induction of HO-1 by CM may compensate for the CM-mediated loss of eNOS and NO in endothelial cells and help maintain vascular homeostasis by releasing CO. Similar to NO, CO exerts many beneficial effects in the circulation, including inhibition of vascular tone, thrombosis, apoptosis, and inflammation [14,15]. Intriguingly, our finding that NAC blocks the induction of HO-1 by CM may contribute to the failure of this agent to prevent CI-AKI [43]. Thus, pharmacological approaches targeting HO-1 or its reaction products provides a promising strategy in ameliorating endothelial dysfunction and the systemic and organ complications associated with the use of CM. Numerous inducers of HO-1 have been identified, including its substrate heme which is already approved for the treatment of acute porphyria (15,45,46). In addition, upstream signaling pathways that mediate the induction of HO-1 may be useful targets. In this respect, activation of Akt is particularly attractive since this kinase is an established inducer of HO-1 in endothelial cells that exerts beneficial effects in the vasculature (47–49). Furthermore, a host of dietary antioxidants have been found to enhance HO-1 expression and may provide a nutritional approach in mitigating CM-induced endothelial and organ dysfunction (50). As an alternative strategy, the products of the HO-1 reaction, CO and biliverdin, may be directly administered since both compounds elicit salutary effects on endothelial function (51–53).

Our current in vitro study provides strong evidence that HO-1 counteracts the negative effects of CM on human endothelial cell function. However, caution is needed when extrapolating findings with cultured endothelial cells to vascular endothelium in intact animals. Cultured endothelial cells do not fully simulate the complex natural environment of these cells within blood vessels and the intricate biochemical and biophysical regulatory mechanisms that occur in vivo. However, in support of our in vitro findings, detrimental effects on endothelial cell function have been reported in both humans and animals following the administration of clinically relevant concentrations of CM (7,12,54–56). Moreover, HO-1 is induced in animals following intravenous administration of CM and protects against CI-AKI in rats (22,44). Future studies employing endothelial cell-specific HO-1-deficient animals will further clarify the importance of endothelial HO-1 in ameliorating CM-associated pathologies.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that CM induces HO-1 gene expression in endothelial cells via the activation of the ROS-Nrf2 signaling pathway. In addition, it found that CM inhibits endothelial cell proliferation and migration, and stimulates the expression of ICAM-1 and the adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelium. Moreover, it showed that the induction of HO-1 antagonizes the anti-proliferative and inflammatory actions of CM. HO-1 represents an attractive therapeutic target in blocking CM-related endothelial and organ dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL59976. Chao-Fu Chang was partially supported by a grant from the Department of Health, Taipei City Government (96001-61-001-055).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nash K, Hafeez A, Hou S. Hospital-acquired renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:930–6. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marenzi G, Lauri G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, De Metrio M, Marana I, et al. Contrast-induced nephropathy in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1780–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dangas G, Iakovou I, Nikolsky E, Aymong ED, Mintz GS, Kipshidze NN, et al. Contrast-induced nephrology after percutaneous coronary interventions in relation to chronic kidney disease and hemodynamic variables. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:13–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Persson PB, Hansell P, Liss P. Pathophysiology of contrast medium-induced nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2005;68:14–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beierwaltes WH. Endothelial dysfunction in the outer medullary vasa recta as a key to contrast media-induced nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304:F31–2. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00555.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scoditti E, Massaro M, Montinari MR. Endothelial safety of radiological contrast media: Why being concerned. Vascul Pharmacol. 2013;58:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sendeski MM, Persson AB, Liu ZZ, Busch JF, Weikert S, Persson PB, et al. Iodinated contrast media cause endothelial damage leading to vasoconstriction of human and rat vasa recta. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F1592–8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00471.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heyman SN, Rosen S, Khamaisi M, Idee JM, Rosenberger C. Reactive oxygen species and the pathogenesis of radiocontrast-induced nephropathy. Invest Radiol. 2010;45:188–95. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181d2eed8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aspelin P, Stacul F, Thomsen HS, Marcos SK, von der Molen AJ. Effects of iodinated contrast media on blood and endothelium. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1041–9. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0081-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Holt CM, Malik N, Shepherd L, Marcos SK. Effects of radiographic contrast media on proliferation and apoptosis of human vascular endothelial cells. Br J Radiol. 2000;73:1034–41. doi: 10.1259/bjr.73.874.11271894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franke R-P, Fuhrmann R, Hiebi B, Jung F. Influence of various radiographic contrast media on the buckling of endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:110–3. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y, Tao Z, Xu Z, Chen B, Wang L, Li C, et al. Toxic effect of a high dose of non-ionic iodinated contrast media on renal glomerular and aortic endothelial cells in aged rats in vivo. Toxicol Lett. 2011;202:253–60. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heyman SN, Rosen S, Brezis M. Radiocontrast nephropathy: a paradigm for the synergism between toxic and hypoxic insults in the kidney. Exp Nephrol. 1994;2:153–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durante W, Johnson FK, Johnson RA. Role of carbon monoxide in cardiovascular function. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:672–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00427.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durante W. Targeting heme oxygenase-1 in vascular disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2010;11:1504–16. doi: 10.2174/1389450111009011504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouard S, Otterbein LE, Anrather J, Tobiasch E, Bach FH, Choi AM, et al. Carbon monoxide generated by heme oxygenase 1 suppresses endothelial cell apoptosis. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1015–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motterlini R, Foresti R, Intaglietta M, Winslow RM. NO-mediated activation of heme oxygenase: Endogenous cytoprotection against oxidative stress to endothelium. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H107–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.1.H107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yachie A, Niida Y, Wada T, Igarishi N, Kaneda H, Toma T, et al. Oxidative stress causes enhanced endothelial cell injury in human heme oxygenase-1 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:129–35. doi: 10.1172/JCI4165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Volti G, Wang J, Traganos F, Kappas A, Abraham NG. Differential effect of heme oxygenase-1 in endothelial and smooth muscle cell cycle progression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;296:1077–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman AI, Olszanecki R, Yang LM, Quan S, Li M, Omura S, et al. Heme oxygenase-1 protects against radiocontrast-induced acute kidney injury by regulating anti-apoptotic proteins. Kidney Int. 2007;72:945–53. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin C-C, Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Wang H, Yang WC, Lin SJ, et al. Far infrared therapy inhibits vascular endothelial inflammation via the induction of heme oxygenase-1. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:739–45. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.160085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Durante W. Physiological cyclic strain promotes endothelial cell survival via the induction of heme oxygenase-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;302:H1634–43. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00872.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peyton KJ, Liu XM, Yu Y, Yates B, Durante W. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits the proliferation of human endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342:827–34. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.194712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam J, Cook JL. Transcriptional regulation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene via the stress response pathway. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:2499–2511. doi: 10.2174/1381612033453730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomsen HS, Morcos SK. Radiographic contrast media. BJU International. 2000;86(Suppl 1):1–10. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joanta AE, Filip A, Clichici S, Andrei S, Daicoviciu D. Iodide excess exerts oxidative stress in some target tissues of the thyroid hormones. Acta Physiol Hung. 2006;93:347–59. doi: 10.1556/APhysiol.93.2006.4.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakris GL, Lass N, Gaber AO, Jones JD, Burnett JC., Jr Radiocontrast medium-induced declines in renal function: a role for oxygen free radicals. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:F115–F120. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1990.258.1.F115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang DD, Hannink M. Distinct cysteine residues in keap1 are required for keap1-dependent ubiquitination of Nrf2 and for stabilization of Nrf2 by chemopreventative agents and oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:137–51. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.8137-8151.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laerum F. Cytotoxic effects of six angiographic contrast media on human endothelium in culture. Acta Radiol. 1987;28:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabelmann A, Haberstroh J, Weyrich G. Ionic and non-ionic contrast agent-mediated endothelial injury. Quantitative analysis of cell proliferation during endothelial repair. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:422–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sawmiller CJ, Powell RJ, Quader M, Dudrick SJ, Sumpio BE. The differential effect of contrast agents on endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell growth in vitro. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27:1128–40. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(98)70015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akcay A, Nguyen Q, Edelstein CL. Mediators of inflammation in acute kidney injury. Mediators Inflamm. 2009;2009:137072. doi: 10.1155/2009/137072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donnahoo KK, Meng X, Ayala A, Cain MP, Harken AH, Medlrum DR. Early kidney tnf-alpha expression mediates neutrophil infiltration and injury after renal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:R922–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.277.3.R922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sheridan AM, Bonventre JV. Cell biology and molecular mechanisms of injury in ischemic acute renal failure. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2000;9:427–34. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200007000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Asmuth EJ, Buurman WA. Endothelial cell associated platelet-activating factor (paf), a costimulatory intermediate in tnf-alpha-induced h2o2 release by adherent neutrophil leukocytes. J Immunol. 1995;154:1383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecules. Blood. 1994;84:2068–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abeyama K, Oh S, Kawano K, Nakajima T, Soejima Y, Nakano K, et al. Nonionic contrast agents produce thrombotic effect by inducing adhesion of leukocytes on human endothelium. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:776–83. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ronda N, Poti F, Palmisano A, Gatti R, Orlandini G, Maggiore U, et al. Effects of the radiocontrast agent iodixanol on endothelial cell morphology and function. Vascul Pharmacol. 2013;58:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deshane J, Chen S, Caballero S, Grot-Przeczek A, Was H, Li Calzi S, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor 1 promotes angiogenesis via a heme oxygenase 1-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:605–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bussolati B, Ahmed A, Pemberton H, Landis RC, Di Carlo F, Haskard DO, et al. Bifunctional role for vegf-induced heme oxygenase-1 in vivo: Induction of angiogenesis and inhibition of leukocytic infiltration. Blood. 2004;103:761–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deramaudt BM, Braunstein S, Remy P, Abraham NG. Gene transfer of human heme oxygenase into coronary endothelial cells potentially promotes angiogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 1998;68:121–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(19980101)68:1<121::aid-jcb12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peyton KJ, Shebib AR, Azam MA, Liu XM, Tulis DA, Durante W. Bilirubin inhibits neointima formation and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:48. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.ACT Investigators. Acetylcysteine for prevention of renal outcomes in patients undergoing coronary and peripheral vascular angiography: main results from the Randomized Acetylcysteine for Contrast-Induced Nephropathy Trial (ACT) Circulation. 2011;124:1250–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.038943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duan BJ, Huang L, Ding H, Huang WY. Curcumin attenuates contrast-induced nephropathy by upregulating heme oxygenase-1 expression in rat. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2013;41:116–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrandiz ML, Devesa I. Inducers of heme oxygenase-1. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:473–86. doi: 10.2174/138161208783597399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morimoto Y, Durante W, Lancaster DG, Klattenhoff J, Tittel FK. Real-time measurements of endogenous CO production from vascular cells using an ultrasensitive laser sensor. Am J Physiol Hear Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H483–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.1.H483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamdulay SS, Wang B, Birdsey GM, Ali F, Dumont O, Evans PC, et al. Celecoxib activates PI-3K/Akt and mitochondrial redox signaling to enhance heme oxygenase-1-mediated anti-inflammatory activity in vascular endothelium. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1013–23. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu BJ, Chen K, Shrestha S, Ong KL, Barter PJ, Rye KA. High-density lipoproteins inhibit vascular endothelial inflammation by increasing 3β-hydroxysteroid-Δ24 reductase expression and inducing heme oxygenase-1. Circ Res. 2013;112:278–88. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mukai Y, Rikitake Y, Shiojima I, Wolfrum S, Satoh M, Takeshita K, et al. Decreased vascular lesion formation in mice with inducible endothelial-specific expression of protein kinase Akt. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:334–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI26223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogborne RM, Rushworth SA, Charalambos CA, O’Connell MA. Heme oxygenase-1: a target for dietary antioxidants. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:1003–5. doi: 10.1042/BST0321003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei Y, Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Wang H, Johnson FK, Johnson RA, et al. Hypochlorous acid-induced heme oxygenase-1 gene expression promotes human endothelial cell survival. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawamura K, Ishikawa K, Wada Y, Kimura S, Matsumoto H, Kohro T, et al. Bilirubin from heme oxygenase-1 attenuates vascular endothelial activation and dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005:155–60. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000148405.18071.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weigel B, Gallo DJ, Raman KG, Karlsson JM, Ozanich B, Chin BY, et al. Nitric oxide-dependent bone marrow progenitor mobilization by carbon monoxide enhances endothelial repair after vascular injury. Circulation. 2010;121:537–48. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blann AD, Adams R, Ashleigh R, Naser S, Kirkpatrick U, McCollum CN. Changes in endothelial, leukocyte and platelet markers following contrast medium injection during angiography in patients with peripheral artery disease. Br J Radiol. 2001;74:811–7. doi: 10.1259/bjr.74.885.740811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murakami R, Machida M, Tajima H, Hayashi H, Uchiyama N, Kumazaki T. Plasma endothelin, nitric oxide and atrial natriuretic peptide levels in humans after abdominal angiography. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:340–3. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0455.2002.430319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernandez-Rodriguez S, Edwards DH, Newton B, Griffith TM. Attenuated store-operated Ca2+ entry underpins the dual inhibition of nitric oxide and EDHF-type relaxations by iodinated contrast media. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;84:470–8. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]