Abstract

Exosomes are a class of naturally occurring nanomaterials that play crucial roles in the protection and transport of endogenous macromolecules, such as microRNA and mRNA, over long distances. Intense effort is underway to exploit the use of exosomes to deliver synthetic therapeutics. Herein, we use transmission electron microscopy to show that when spherical nucleic acid (SNA) constructs are endocytosed into PC-3 prostate cancer cells, a small fraction of them (< 1%) can be naturally sorted into exosomes. The exosome-encased SNAs are secreted into the extracellular environment from which they can be isolated and selectively re-introduced into the cell type from which they were derived. In the context of anti-miR21 experiments, the exosome-encased SNAs knockdown miR-21 target by approximately 50%. Similar knockdown of miR-21 by free SNAs requires a ~3000-fold higher concentration.

Keywords: gold nanoparticles, exosomes, microRNA, cancer therapy, gene regulation

1. Introduction

The development of nanotechnology-based carriers is increasingly recognized as a promising approach for efficient antisense oligonucleotide delivery.[1] Examples of synthetic nano-delivery vehicles and gene regulation agents include liposomes,[2] polymeric nanoparticles,[3] viral vectors,[4] and most recently spherical nucleic acids (SNAs).[5] Liposomes have been the most extensively studied platform and have shown promise with respect to their ability to efficiently stabilize nucleic acids.[6] Synthetic liposomes, however, often exhibit cytotoxicity and low cellular uptake efficiencies when utilized for in vivo drug delivery.[7] SNAs overcome many of these limitations but often get trapped in endosomes, which can decrease their potency. One intriguing strategy is to utilize natural, cell-produced nanocarriers such as exosomes, in combination with synthetic antisense agents, to bypass some of the limitations of the synthetic structures, including instability against enzymatic degradation, immunogenicity, cell membrane penetration, and endosomal escape.

Exosomes are being explored as promising endogenous nanocarriers to deliver therapeutic biomolecules such as siRNA to specific tissues within living organisms.[8] They are formed by the inward budding of the inner endosomal membrane during the development of early endosomes into mutlivascular bodies (MVBs), followed by exosome secretion into the extracellular lumen upon fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane.[9] Exosomes (40-100 nm in diameter) are naturally secreted from various cell types to transport endogenous microRNAs (miRNAs, miR) and mRNAs from one cell to another.[10] In this way, exosomes serve the function of long distance signal carriers. Interestingly, exosomes loaded with endogenous miRNAs can reach blood circulation when secreted from one tissue, and provide a means of protecting their miRNA cargo from various serum nucleases during transit.[11] This unique property is particularly important for enhancing the stability of many oligonucleotide-based therapeutic agents, which could lead to more potent treatments.

SNAs are an important new class of potential therapeutic agents that often consist of a gold nanoparticle core with a dense shell of highly oriented oligonucleotides (Scheme 1A). They exhibit unique properties that make them good candidates for exosomal loading such as enhanced serum stability,[12] rapid cell uptake without transfection agents,[13] low immunogenicity,[14] and the ability to control gene regulation.[5, 15] These unique properties are mediated by the dense shell of oligonucleotides around the gold nanoparticle, where oligonucleotides also could serve as signaling molecules for SNAs to be taken up by endogenous exosomes.[7] Taken together, these unique properties allow SNAs to overcome many biological barriers ranging from resisting serum nucleases to crossing the cell membrane in order to be internalized within exosomes by utilizing the natural exosomal sorting process of cytoplasmic biomolecules. Therefore, we hypothesized that we could use cells and their natural pathways to engage with SNAs, internalize them in exosomes, and then subsequently use such exosomes as novel and effective nucleic acid delivery vehicles. Herein, we show that this is in fact the case, and that such structures can be used as potent miRNA regulation agents in the context of PC-3 prostate cancer cell lines to down-regulate endogenous miR-21. miR-21 is linked to many forms of cancer, including prostate cancer[16] and at high levels has been shown to stimulate cancer proliferation, invasion, and metastasis by down regulating tumor suppressors such as PTEN.[16b, 17]

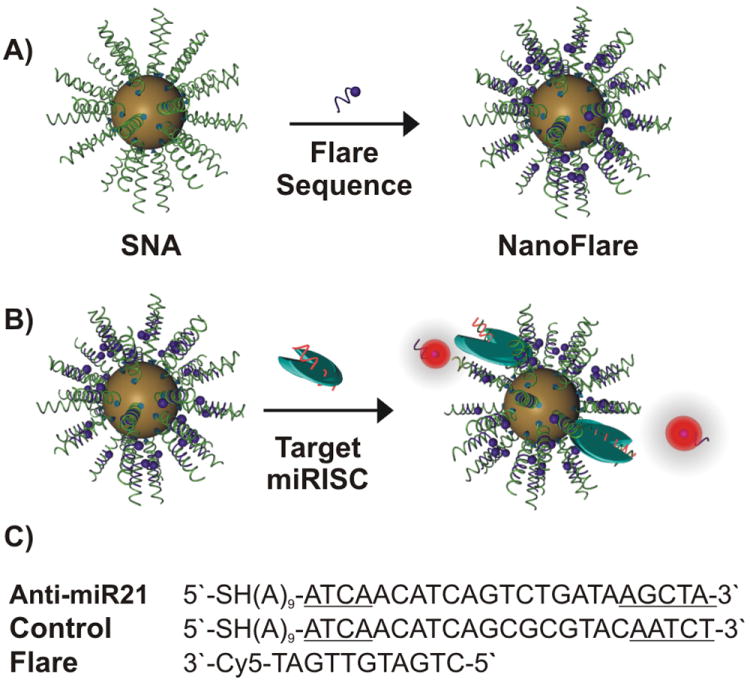

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of spherical nucleic acids (SNAs) hybridized with flare sequences: A) Gold nanoparticles (13 ± 1 nm) surface functionalized with propylthiol-terminated antisense DNA were hybridized with short complementary fluorophore-labeled DNA (Flare). B) Incubation of the synthesized nanoconjugates (A) with complementary miRNA targets while loaded into RISC (miRISC) causes an increase in fluorescence signal. C) The DNA/LNA gapmer sequences (target and control), which serve as antisense strands (The underlined bases are LNA), and the flare sequence used to make the nanoflare conjugates.

2. Results and Discussion

One embodiment of SNAs are structures called nanoflares, which have short oligonucleotides with fluorophores hybridized with the SNA in such a way that the fluorophore is near the gold and quenched (Scheme 1A).[18] These structures, when they enter cells, can bind to mRNA targets and release the fluorophore-labeled oligonucleotide, which turns on fluorescence. Therefore, nanoflares provide a convenient way of tracking specific RNA concentrations in live cells. In this manuscript, we use nanoflares to track the ability of SNAs to engage in miRNA binding and gene regulation (Scheme 1B).

To construct nanoflares for the specific detection of the intracellular levels of miRNA targets, we first synthesized SNAs that consist of a DNA/LNA gapmer recognition sequence that targets mature miR-21 (Scheme 1C).[18b, 19] The LNA (locked nucleic acid) bases are located at the two ends of the recognition sequence, where one end (3′-end) is required to facilitate and increase binding affinity to the seeding region of the intracellular miR-21 target, while the other terminus (5′-end) enhances the hybridization efficiency of the flare sequence. Following a “salt-ageing” process, SNAs that antagonize miR-21 (denoted “anti-miR21 SNA”) can be synthesized with a high surface density of anti-miR21 DNA (77 ± 4 DNA strands per gold nanoparticle) following published protocols.[20] Analogous SNAs functionalized with nonsense DNA (denoted “a scrambled SNA”) that lack the correct antisense seeding sequence were also synthesized at a similar oligonucleotide loading (71 ± 9 DNA strands per gold nanoparticle) to serve as a negative control. Both anti-miR21 SNAs and scrambled SNAs were subsequently hybridized with short complementary fluorophore-labeled DNA (~10 fluorophore-labeled strands per gold nanoparticle) (See sequences in Scheme 1C and Table S1). The specificity of anti-miR21 SNAs for synthetic (Figure S1) and endogenous (Figure 1A) miR-21 targets was investigated using a fluorescence plate reader and flow cytometry, respectively. Interestingly, anti-miR21 SNA exhibited a ~9 fold higher cell-associated fluorescence relative to scrambled SNA after incubating both nanoconjugates with the PC-3 cells (Figure 1A). This experiment emphasizes the ability of SNAs to reach intracellular biomolecules such as miRNAs that are often incorporated into the RNA-inducing silencing complex (miRISC) (Scheme 1B).

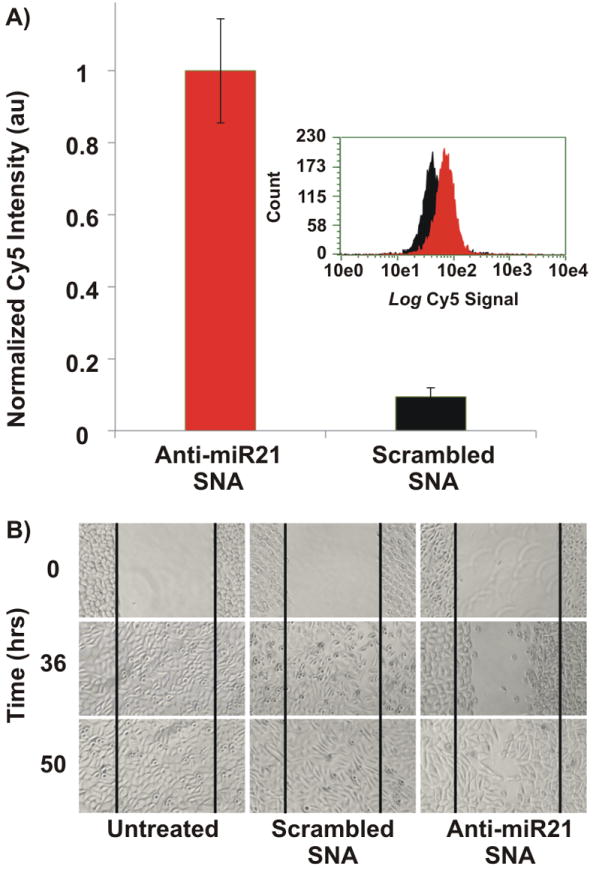

Figure 1.

Investigating the ability of nanoconjugates to reach intracellular targets. A) The specificity of the anti-miR21 SNAs for intracellular miR-21 was investigated using the nanoflare architecture. A nine fold increase in cell-associated fluorescence is observed versus control (a scrambled sequence). Nanoconjugates were incubated with PC-3 prostate cancer cells for 12 hours followed by quantifying the cell-associated fluorescence using a Guava easyCyte 8HT Flow Cytometry System. The smaller inset is a representative histogram of the flow cytometry data. B) Monitoring the migration rate of PC-3 cells following incubation with anti-miR21 SNAs. Anti-miR21 SNA reduced PC-3 cell migration rate significantly as indicated by the slow closure of the wound-like scratch that was made within the confluent PC-3 cells relative to scrambled SNAs and untreated systems.

We next investigated the functional performance of anti-miR21 SNAs and scrambled SNAs by using conjugates that do not contain the flare sequence. The migration rate of PC-3 cells was monitored using a wound healing experiment following literature reports.[15] In short, an artificial wound was made within confluent PC-3 cells followed by incubation with either anti-miR21 SNA or scrambled SNAs for up to 50 hours. PC-3 cells treated with anti-miR21 SNAs exhibited significantly slower wound closure relative to PC-3 cells that are either untreated or incubated with scrambled SNAs (Figure 1B). Such reduction in cell progression and migration is consistent with literature reports describing the consequences of reduced expression levels of the miR-21target.[16a] These results suggest that SNAs could be utilized as potential therapeutic agents to antagonize miR-21targets.

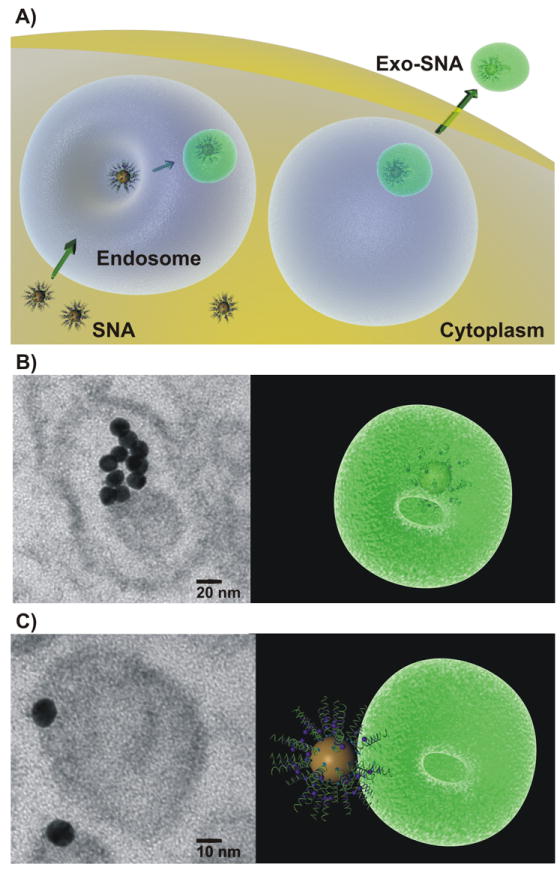

After confirming that anti-miR21 SNA can reach intracellular targets and exhibit a functional response, we studied how these SNA constructs can be encased in exosomes by harnessing natural cellular machinery (Figure 2A). Following cellular treatment with SNAs, we have estimated that <1% of the intracellular SNA nanoconjugates are found localized in exosomes (denoted “exo-SNAs”) based upon analysis by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Figure 2B-C). Both the cup shape and the size (40-100 nm) of the vesicle loaded with SNAs are characteristic of exosomes.[21] The TEM results suggest that SNAs can be internalized within exosomes (Figure 2B) or bound to the membrane surface (Figure 2C). The fact they are bound internally and on the surface of the exosome suggest that there are different pathways for processing SNAs (vide infra). Moreover, we further isolated exo-SNAs that are secreted by PC-3 cells to verify the identity of these small vesicles, and confirmed by ELISA that they express CD9, a known exosomal surface marker (2.8 ± 0.76 × 108 exosomes expressing CD9).[22] In summary, both the TEM imaging and ELISA data support the notion that SNAs can be naturally sorted by an endosomal-exosomal pathway.

Figure 2.

Loading SNAs into Exosomes: A) Scheme of potential mechanism of loading SNAs into exosomes through a known exosomal-endosomal pathway. B) TEM image demonstrates the internalization of SNAs within exosomes. Scale bar 20 nm. C) TEM image of SNA bound to the outer surface of exosome. Scale bar 10 nm.

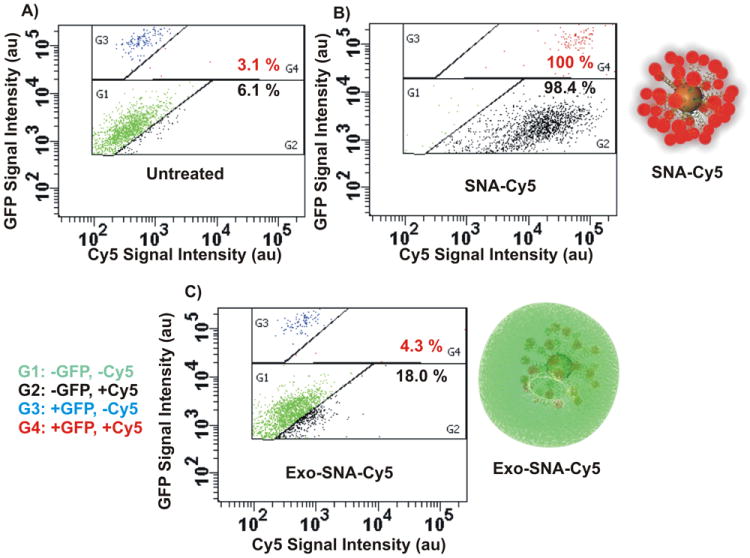

We next compared the relative ability of exo-SNAs and exosome-free SNAs to enter specific cell types. A co-cultured model was utilized to monitor the selective cellular uptake of SNAs; resting cancerous PC-3 cells were co-grown with non-cancerous endothelial C166 cells expressing GFP (C166-GFP).[23] The differential populations of PC-3 and C166-GFP cells can be distinguished by their ability to fluoresce, as revealed by FACS analysis (Figure 3A). Next, Cy5-labeled SNAs were synthesized to aid in the determination of cellular uptake of the nanoconjugates (Table S1). To achieve this goal, one fraction of the Cy5-SNAs was treated with PC-3 cells to allow for exosome internalization (denoted “exo-SNA-Cy5”). As a control, another fraction of the Cy5-SNAs did not receive cellular treatment, and therefore was free of exosomes. This control was used to investigate the uptake selectivity of free SNAs by both cell types (PC-3 and C166 cells). By FACS analysis, Cy5-SNAs can be internalized into 98.4% of PC-3 and 100% of C166 cells (Figure 3B) showing no selectivity in uptake by specific cell types. By contrast, Cy5-labeled exo-SNAs that were isolated from PC-3 cells showed preferential delivery (~4 fold excess) into resting PC-3 cells relative to C166-GFP cells (18% and 4.3%, respectively) (Figure 3C). Notably, the Cy5 fluorescence of cells treated with SNAs was significantly higher (~2 fold) than the values for those treated with exo-SNAs. While this can be explained by the 3 order-of-magnitude difference in concentrations of SNAs incubated with cells in the two experiments (0.35 pM, exo-SNAs; and 300 pM, free SNAs), it also reinforces our conclusion that the exosomal encasement endows SNAs with the specific ability to target cancer cells, consistent with literature reports that exosomes derived from PC-3 express surface antigens that are specific to prostate cancer cells.[22, 24] This latter experiment is important since both the TEM and FACS analysis demonstrate the ability of SNAs to be sorted by the endosomal-exosomal pathway (vide supra), but they do not fully confirm the encasement of SNAs by exosomes (Figure 2B).

Figure 3.

Exosome-Loaded SNAs Exhibit Targeting Ability: FACS analysis of cellular interaction with SNA systems in a co-culture model. Resting cancer PC-3 cells were co-grown with non-cancerous endothelial C166 cells expressing GFP (C166-GFP). A) A representative dot plot by FACS analysis shows the untreated co-culture of two cell populations; PC-3 (G1, green) and C166-GFP (G3, blue). B) A representative dot plot of co-culture treated with Cy5-labeled SNAs, where SNA-Cy5 bind to PC-3 (G2, black) and C166 cells (G4, red) with similar efficiencies (98.4% and 100%, respectively). C) Co-culture treated with PC-3 derived exosome-loaded SNA-Cy5 (exo-SNA-Cy5) demonstrates that PC-3 cells preferentially take up exo-SNA-Cy5s. An increase in the number of black dots (G2) corresponds to the high PC-3 cell-associated exo-SNA-Cy5. Red dots in G4 correspond to C166 cell-associated exo-SNA-Cy5.

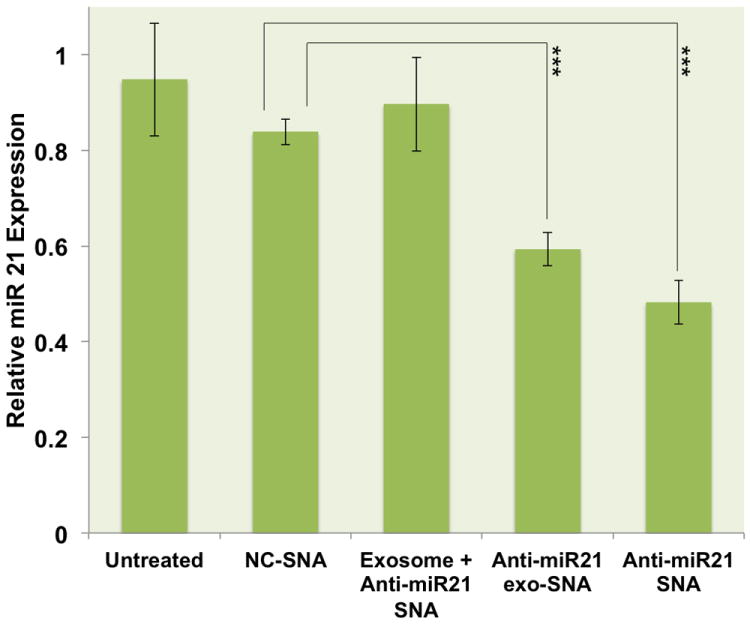

A functional assessment of exo-SNAs that specifically antagonize miR-21 (anti-miR21 exo-SNA) confirmed the localization of SNAs within exosomes. Indeed, although obtained at extremely low concentrations (0.35 pM of SNAs), the isolated anti-miR21 exo-SNAs were able to reduce 50% of the expression levels of miR-21 in PC-3 cells (Figure 4). In contrast, qRT-PCR results show no reduction in the expression levels of miR-21 when cells were treated with exogenous anti-miR21 SNAs that are physically mixed with exosomes (denoted “exosome + anti-miR21 SNA”) at identical concentrations (0.35 pM). Thus, to account for the observed aforementioned knockdown results, SNAs must be loaded into exosomes with the natural cellular machinery. Note that similar knockdown efficiency (50%) can be obtained by treating PC-3 cells with ~3000 fold higher concentrations (1 nM) of free anti-miR21 SNAs (Figure 4), which quantifies the performance advantage one obtains by loading SNAs into exosomes prior to cellular transfection. Also, no significant off-target knockdown was observed when measuring the expression levels of randomly selected miRNA targets (let7d, miR-141, -20a, -200c, and -205) (Figure S2). These results are consistent with the conclusion that the reduced levels in miR-21 expression originate from SNAs that were encased by exosomes. Presumably, the degree of knockdown obtained by anti-miR21 exo-SNAs is due to the expression of tetraspanin CD9 on the surface of exosomes that facilitates direct membrane fusion with the resting cells followed by anti-miR21 SNAs release in the cytosol.[25]

Figure 4.

qRT-PCR quantification of miR-21 expression in PC-3 cells following treatment with 1 nM scrambled SNAs, SNAs specific to miR-21 target (anti-miR21 SNA at 1 nM concentrations), PC-3 derived exosome-loaded SNAs specific to miR-21 (anti-miR21 exo-SNA at 0.35 pM), or PC-3 derived exosomes that were mixed with 0.35 pM exogenous anti-miR21 SNA (exosome + anti-miR21 SNA). (p= 0.00032, anti-miR21 SNA; p= 0.00047, anti-miR21 exo-SNA).

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have shown that nanoflare-SNAs for anti-miR21 can be used to detect intracellular levels of miR-21 and simultaneously reduce expression levels of the target. Interestingly, the anti-miR21 SNA nanoconjugates can be loaded into exosomes and used as transfection agents to selectively target PC-3 cancer cells in cell culture and exhibit significant gene knockdown. The fact that exo-SNAs are approximately 3000 times more effective at knocking down miRNA targets (based upon concentration) suggest that exosomal encasement by the natural cellular machinery is a very promising approach to increasing the effectiveness of an already potent gene regulation platform. The approach used to encase SNAs in this manuscript is impractical in its current state, due to the inefficiency of SNA loading in the exosome and the scale at which it can be done. However, the results stand as a challenge to the chemistry and biology communities to create synthetic exosome mimics that can be readily loaded with SNA and related oligonucleotide cargo.

4. Experimental Section

Synthesis of Spherical Nucleic Acid (SNA) Nanoconjugates

All LNA-containing oligonucleotide sequences used in this study to regulate the expression levels of endogenous miR-21 were purchased from Exiqon. The underlined bases were LNA modified nucleotides to produce chimeric oligonucleotide strands containing LNA and DNA bases. Anti-miR21 DNA, 5′-SH-(A)9-ATCAACATCAGTCTGATAAGCTA-3′; scrambled control, 5′-SH-(A)9-ATCAACATCAGCGCGTACAATCT-3′; Cy5-labeled anti-miR21 DNA, 5′-SH-(A)9-ATCAACATCAGTCTGATAAGCTA-Cy5-3′. 4 nM thiol-modified nucleic acid strands were incubated with 10 nM gold nanoparticle (13 ± 1 nm in diameter) solutions for 1 hour at 25 °C. Following incubation, 0.01% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and 0.1 M sodium chloride were added, and the mixture was incubated for an additional hour while shaking at 25 °C. Two additional aliquots of 0.1 M sodium chloride were added to achieve a final concentration of 0.3 M sodium chloride, followed by overnight incubation while shaking at 25 °C. Unreacted materials were washed away by three rounds of centrifugation (16000 rcf, 15 min), supernatant removal, and re-suspension in PBS (10 mM phosphate, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4).

Determining Oligonucleotide Loading

To determine the number of oligonucleotide per nanoparticle, the concentrations of gold nanoparticles were first measured using UV/vis spectroscopy (ε524nm= 2.7 × 108 M-1cm-1). Next, synthesized SNAs were incubated with 0.1 M KCN solution to release the surface-functionalized oligonucleotides by oxidatively dissolving gold nanoparticles. The number of the released DNA strands was quantified using oligonucleotide determination kit following the manufacturer’s protocols (Oligreen, Invitrogen) to yield the number of oligonucleotides per nanoparticle.

Nanoflare Formation

Short complementary Cy5-labeled DNA sequence used in this study to form the nanoflare duplex (Flare: 5′-CTGATGTTGAT-Cy5-3′) was purchased from IDT. 100 nM of target SNAs were incubated with 1μM flare in PBS at 70 °C for 30 minutes. The flare sequence was annealed by slowly cooling down this hybridization mixture at 25 °C overnight.

Cell Culture

All cell lines used in this study were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Human prostate cancer cells (PC-3) were grown in PRMI, while mouse endothelial cells (C166, and GFP+ C166) were grown in DMEM, in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Both media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Buffer Testing of anti-miR21 SNAs and Intracellular Detection of miR-21 target

First, the performance of the nanoflare architecture was investigated by performing extracellular fluorescence experiments using synthetic miR-21. All reagents used to synthesize synthetic miR-21 target were purchased from Glen Research. Synthetic miR-21 (5′-UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGAU-3′) was synthesized on a MerMade 6 (Bioautomation) synthesizer using standard solid-phase phosphoramidite chemistry. The RNA was purified using reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with RNase-free solutions. 200 nM synthetic miR-21 was added to 5 nM anti-miR21 SNAs hybridized to Cy5-labeled flares in PBS containing 3 mM MgCl2. The Cy5 signals were recorded after 10 minutes of incubating the synthetic miR-21 with nanoflares using Photon Technology International FluoDia T70 fluorescence plate reader. For the intracellular detection of miR-21 target, PC-3 cells were seeded in 96 well plates and allowed to reach 70% confluency (~1.7 × 104 cells). Anti-miR21 SNAs pre-sterilized using a 0.2 μm acetate filter (GE Healthcare) were then added directly to the cells at final concentration of 1 nM and incubated for 12 hours. Analogous nonsense control was used to probe the nonspecific binding (a scrambled SNA). Following incubation, the cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, suspended in PBS, and the cell associated fluorescence was quantified using Guava easyCyte 8HT Flow Cytometry System (Millipore). All samples were measured in triplicates. All data were normalized to background signals generated from cells treated with control SNA that lack the fluorescence reporter.

Wound Healing Assay

PC-3 cells were seeded in 6 well plates and allowed to reach high confluency (~100%) prior to transfection with SNAs. Artificial wounds were created by scrapping the cells in a straight line using sterile P-200 pipet tips. Detached cells were washed away, and the remaining cells were re-incubated in PRMI growth media. Next, the cells were transfected with 10 nM of sterilized anti-miR21 SNAs and scrambled SNAs in separate wells. Untreated cells were used as a negative control. Cell migration was monitored as a function of full closure of the wound in negative controls by taking images at 0, 36, and 50 hours using a Zeiss Invertoskop microscope.

TEM Imaging of Exosome-Loaded SNAs

After transfecting C166 cells with SNAs as shown in the wound healing experiments, the ability of SNAs to be internalized within exosomes was examined using TEM imaging. Cell pellets were re-suspended in 0.2 mL of molten 4% gelatin in PBS, and pelleted again by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 5 minutes. Embedded in congealed gelatin, cells were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 100 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH = 7.4), stained by 1% OsO4, and by 0.9% OsO4 and 0.3% K4Fe(CN)6, with all steps carried out at 4 °C for 2 hours. After gradual dehydration with ethanol and propylene oxide, cell pellets were embedded in Epon 812 resins (Electron Microscopy Sciences). 80 nm-thick sections were deposited on 200-mesh copper grids (EMS) and stained with 3% uranyl acetate (SPI Supplies) and Reynolds lead citrate for visualization under a JEM 1230 microscope (JEOL) using a beam voltage of 80 kV. An Orius SC 1000 CCD camera (Gatan) was used to record the images.

Isolation of Exosome-Loaded SNA

PC-3 cells were grown in 10 tissue culture flasks (T25) to 70% confluency. One day prior to treatment, cells were rinsed with PBS and grown further in serum-free growth medium to avoid exosomal contamination from serum. 1 nM of either unlabeled or Cy5-labeled anti-miR21 SNAs were added and allowed to be internalized by the PC-3 cells for 2 hours. Cells were rinsed with PBS to remove excess SNAs, supplemented with serum-free growth medium, and allowed to secret exosomes for 24 hours. Following incubation, 100 mL of culture media (10 mL per T25 flask) were collected, and exosomes were isolated using ExoQuick-TC™ exosome isolation kit (System Biosciences) following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, isolated culture media were centrifuged to remove cells and cell debris (3000 rpm, 15 minutes). The supernatant was mixed with 20 mL ExoQuick-TC™ exosome precipitation solution, and allowed to incubate at 4 °C for 12 hours. Next, the mixture was centrifuged to collect exosome pellet (1500 rpm, 30 minutes). Isolation of exosomes loaded with anti-miR21 SNAs (anti-miR21 exo-SNAs) was done in triplicates to generate three fractions of exo-SNAs. Analogous fraction of exosomes loaded with Cy5-labeld SNAs (exo-SNA-Cy5) was isolated for FACS analysis. A negative control isolate of exosomes that lack SNAs was prepared from untreated PC-3 cells as well.

Quantification of Exosome Surface Antigen (CD9)

Isolated exosome pellet from PC-3 cells were suspended in exosomes binding buffer (200 μL). First, the concentrations of gold nanoparticles (0.35 ± 0.02 pM) were measured using UV/vis spectrophotometry (ε524nm= 2.7 × 108 M-1cm-1). Next, isolated exosome pellets were subjected to CD9 surface antigen quantification using ELISA kit and exosome CD9 specific primary antibody (System Biosciences) following manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 50 μL of exosome pellet was immobilized onto micro-titer plate at 37 °C for 16 hours. Unbound exosomes were washed away by three successful rounds of washing, followed by immobilization of 50 μL exosome CD9 specific primary antibody solution at room temperature for 1 hour. Unreacted antibody was washed away, and 50 μL secondary antibody was immobilized at room temperature for 1 hour. After rinsing the antibody complex, 50 μL of the super-sensitive TMB ELISA substrate was added and allowed to incubate for 45 minutes at room temperature. The concentrations of exosomes amount of CD9 surface antigen was determined by monitoring A450nm using multiskan spectrum plate reader (Thermo). The standard error of the exosome numbers was determined from three independent experiments.

FACS Analysis

A co-cultured model was created by co-seeding tumor-derived PC-3 cells with non-cancerous endothelial C166 cells expressing GFP (C166-GFP) in 48 well plates and cells were allowed to grow for 6 hours prior to treatment. 0.35 pM of Cy5-labeled anti-miR21 SNAs that were internalized within exosomes (Exo-SNA-Cy5) was isolated from PC-3 cells and added to the co-cultured model for 3 hours. 300 pM of exosome-free Cy5-labeld anti-miR21 SNAs (SNA-Cy5) was added to a separate well of co-cultured cells. Following incubation, co-cultured cells were washed with PBS, trypsinized, suspended in PBS, and subjected to FACS analysis on a BD LSR II Flow Cytometry (BD Biosciences) to quantify the Cy5 and GFP fluorescence signals. The cell associated fluorescence signals were detected with laser excitations at 405 nm (GFP) and 633 nm (Cy5).

Knockdown Experiments and qRT-PCR Analysis of miR-21

PC-3 cells were cultured in 24 well plates and allowed to reach 50% confluency. In separate wells, free SNAs (anti-miR21 SNAs and scrambled SNAs) were added at 1 nM concentrations, while exosomes loaded with anti-miR21 SNAs (anti-miR21 exo-SNA) were added at 0.35 pM concentrations. One concentration of SNAs was studied in order to investigate how critical the formation of exo-SNAs is. To confirm that SNAs are loaded into exosomes, analogous treatment was prepared containing free exosomes that were derived from PC-3 cells and exogenous anti-miR21 SNAs (denoted “exosome + anti-miR21 SNA”). 7.5 pM exosomes were incubated with 0.35 pM exogenous anti-miR21 SNAs in serum-free PRMI growth media for 3 hours in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The treated and untreated PC-3 cells were allowed to grow for 48 hours, washed with PBS, detached with trypsin enzyme, and the total RNA was isolated using mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion). In short, cell pellets were washed with PBS, and lysed with 300 μL of cell disruption and 300 μL of 2X denaturing buffers. Total RNA was extracted by adding 600 μL of acid/phenol/chloroform, aqueous phase separation, and adding 100% ethanol at a 1:1.25 volume ratio. Next, RNA was column filtered and eluted with 100 μL of pre-warmed elution buffer. 10 ng of total RNA was analyzed using TaqMan RT kit (PN 4366596), TaqMan U6- snRNA, and hsa-miR-21 primers following manufacturer’s protocol (Applied Biosystems, TaqMan MicroRNA Assays, PN 4324018). PCR reactions were carried out on RT products using TaqMan PCR master mix, TaqMan U6-snRNA, and hsa-miR-21 probes. Expression levels of miR-21 were quantified using LightCycler® 480 (Roche) and normalized to an endogenous U6 snRNA control. The standard errors for this experiment were obtained from three independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the following awards: DARPA HR0011-13-2-0018, NIH/CCNE initiative U54 CA151880, and NIH/NIAMS R01AR060810 and R21AR062898. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the sponsors. A. H. A. acknowledges the King Abdullah Scholarships Program funded by the Ministry of Higher Education of Saudi Arabia for doctoral scholarship support. C.H.J.C. acknowledges a postdoctoral research fellowship from The Croucher Foundation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available online from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Ali H. Alhasan, Department of Chemistry and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208-3113, USA Interdepartmental Biological Sciences Program, Northwestern University, 2205 Tech Drive, Evanston, IL 60208-3113, USA.

Pinal C. Patel, AuraSense Therapeutics, LLC, 8045 Lamon Avenue, Suite 410, Skokie, IL 60077

Chung Hang J. Choi, Department of Chemistry and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208-3113, USA

Prof. Chad A. Mirkin, Email: chadnano@northwestern.edu, Department of Chemistry and International Institute for Nanotechnology, Northwestern University, 2145 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208-3113, USA.

References

- 1.a) Meng H, Xue M, Xia T, Zhao YL, Tamanoi F, Stoddart JF, Zink JI, Nel AE. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12690–12697. doi: 10.1021/ja104501a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lu J, Liong M, Sherman S, Xia T, Kovochich M, Nel AE, Zink JI, Tamanoi F. Nanobiotechnol. 2007;3:89–95. doi: 10.1007/s12030-008-9003-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Agbasi-Porter C, Ryman-Rasmussen J, Franzen S, Feldheim D. Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1178–1183. doi: 10.1021/bc060100f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Kim CS, Tonga GY, Solfiell D, Rotello VM. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Cullis PR, Hope MJ, Bally MB, Madden TD, Mayer LD, Fenske DB. Biochim et Biophys Acta. 1997;1331:187–211. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(97)00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zimmermann TS, Lee AC, Akinc A, Bramlage B, Bumcrot D, Fedoruk MN, Harborth J, Heyes JA, Jeffs LB, John M, Judge AD, Lam K, McClintock K, Nechev LV, Palmer LR, Racie T, Rohl I, Seiffert S, Shanmugam S, Sood V, Soutschek J, Toudjarska I, Wheat AJ, Yaworski E, Zedalis W, Koteliansky V, Manoharan M, Vornlocher HP, MacLachlan I. Nature. 2006;441:111–114. doi: 10.1038/nature04688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Gonzalez H, Hwang SJ, Davis ME. Bioconjug Chem. 1999;10:1068–1074. doi: 10.1021/bc990072j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Davis ME. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:659–668. doi: 10.1021/mp900015y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) McAllister K, Sazani P, Adam M, Cho MJ, Rubinstein M, Samulski RJ, DeSimone JM. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:15198–15207. doi: 10.1021/ja027759q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Perry JL, Reuter KG, Kai MP, Herlihy KP, Jones SW, Luft JC, Napier M, Bear JE, DeSimone JM. Nano Lett. 2012;12:5304–5310. doi: 10.1021/nl302638g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee S, Johnson PR, Wong KK., Jr Science. 1992;258:1485–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.1359646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosi NL, Giljohann DA, Thaxton CS, Lytton-Jean AKR, Han MS, Mirkin CA. Science. 2006;312:1027–1030. doi: 10.1126/science.1125559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenske DB, Cullis PR. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:25–44. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kooijmans SA, Vader P, van Dommelen SM, van Solinge WW, Schiffelers RM. Int J Nanomed. 2012;7:1525–1541. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S29661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alvarez-Erviti L, Seow Y, Yin H, Betts C, Lakhal S, Wood MJ. Nature Biotechnol. 2011;29:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:569–579. doi: 10.1038/nri855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valadi H, Ekstrom K, Bossios A, Sjostrand M, Lee JJ, Lotvall JO. Nature Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O’Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10513–10518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804549105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prigodich AE, Alhasan AH, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:2120–2123. doi: 10.1021/ja110833r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Patel PC, Millstone JE, Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. Nano Lett. 2007;7:3818–3821. doi: 10.1021/nl072471q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massich MD, Giljohann DA, Seferos DS, Ludlow LE, Horvath CM, Mirkin CA. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1934–1940. doi: 10.1021/mp900172m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hao L, Patel PC, Alhasan AH, Giljohann DA, Mirkin CA. Small. 2011;7:3158–3162. doi: 10.1002/smll.201101018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Krichevsky AM, Gabriely G. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:39–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schramedei K, Morbt N, Pfeifer G, Lauter J, Rosolowski M, Tomm JM, von Bergen M, Horn F, Brocke-Heidrich K. Oncogene. 2011;30:2975–2985. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu S, Wu H, Wu F, Nie D, Sheng S, Mo YY. Cell Research. 2008;18:350–359. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Hill HD, Prigodich AE, Mirkin CA. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:15477–15479. doi: 10.1021/ja0776529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Prigodich AE, Seferos DS, Massich MD, Giljohann DA, Lane BC, Mirkin CA. ACS Nano. 2009;3:2147–2152. doi: 10.1021/nn9003814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seferos DS, Giljohann DA, Rosi NL, Mirkin CA. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1230–1232. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alhasan AH, Kim DY, Daniel WL, Watson E, Meeks JJ, Thaxton CS, Mirkin CA. Anal Chem. 2012;84:4153–4160. doi: 10.1021/ac3004055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varkouhi AK, Scholte M, Storm G, Haisma HJ. J Control Release. 2011;151:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gyorgy B, Szabo TG, Pasztoi M, Pal Z, Misjak P, Aradi B, Laszlo V, Pallinger E, Pap E, Kittel A, Nagy G, Falus A, Buzas EI. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2667–2688. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang T, Petrenko VA, Torchilin VP. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:1007–1014. doi: 10.1021/mp1001125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Nedawi K, Meehan B, Micallef J, Lhotak V, May L, Guha A, Rak J. Nature Cell Biol. 2008;10:619–624. doi: 10.1038/ncb1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van den Boorn JG, Schlee M, Coch C, Hartmann G. Nature Biotechnol. 2011;29:325–326. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.