Abstract

Moscow has a large population of immigrants and migrants from across the Former Soviet Union. Little is studied about men who have sex with men (MSM) within these groups. Qualitative research methods were used to explore identities, practices, and factors affecting HIV prevention and risks among immigrant/migrant MSM in Moscow. Nine interviews and three focus group discussions were conducted between April–June 2010 with immigrant/migrant MSM, analyzed as a subset of a larger population of MSM who participated in qualitative research (n=122). Participants were purposively selected men who reported same sex practices (last 12 months). Migrants were men residing in Moscow but from other Russian regions and immigrants from countries outside of Russia. A socio-ecological framework was used to describe distal to proximal factors that influenced risks for HIV acquisition. Stigma and violence related to homophobia in homelands, and concerns about xenophobia and distrust of migrants in Moscow emerged as key themes. Participants reported greater sexual freedom in Moscow but feared relatives in homelands would learn of behaviors in Moscow, often members of their own ethnicity. Internalized homophobia was prevalent and linked to traditional sexual views. MSM ranged from heterosexual to gay-identified. Sexual risks included sex work, high numbers of partners, and inconsistent condom use. Avoidance of HIV testing or purchasing false results was related to reporting requirements in Russia, which may bar entry or expel those testing positive. HIV prevention for MSM should consider immigrant/migrant populations, the range of sexual identities, and risk factors among these men. The willingness of some men to socialize with immigrants/migrants of other countries may provide opportunities for peer-based prevention approaches. Immigrants/migrants comprise important proportions of the MSM population, yet rarely acknowledged in research. Understanding their risks and how to reach them may improve the overall impact of prevention for MSM and adults in Russia.

Keywords: men who have sex with men, migrant, immigrant, HIV risk, stigma, Russia

Introduction

Labor demands and economic growth have encouraged migration into and within Russia. Moscow, the capital of the Russian Federation (pop. 11.5 million persons, 2011) attracts both migrants from across Russia and immigrants (documented and irregular from across the wider Former Soviet Union (FSU) and nearby countries.(IOM, 2012; Mosmuller, 2011; Williams & Aktoprak, 2010) Russia also serves as a migration route to the West from countries such as Afghanistan and Kyrgyzstan, among others.(2006; Williams & Aktoprak, 2010) Figure 1 illustrates the countries providing both long-term and transit migrants into or through Russia. Currently, there are an estimated 13–17 million registered and irregular (undocumented) migrants in Russia.(Mosmuller, 2011)

Figure 1.

Countries contributing migrant populations into and irregular migrant flows through Russia

Note: Some countries contribute irregular and permanent migrant populations, there are coded as those contributing migrants into the Russian Federation (dark red); Dots represent large cities. Map adapted from reports provided by the International Organization for Migration (IOM, 2012; Williams & Aktoprak, 2010)

Differing norms and values related to gender and sexuality among immigrants/migrants compared to Moscovites are pronounced. In many Russian regions and the FSU, sexual and gender minorities face more restrictive and intolerant situations than in Moscow. Homosexuality remains a criminal offense in Turkmenistan (2000) and Uzbekistan (1994), and a bill criminalizing the promotion of homosexuality has recently been passed in Ukraine.(2012) Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) persons in these areas may be pressured to leave their homelands and Moscow is a common destination. Stigma and prejudice against non-Russian ethnicities and cultures arriving in Moscow may, however, introduce other limitations in opportunity, employment, and safety.(Amirkhanian, Kuznetsova, et al., 2011; IOM, 2012)

HIV was recently recognized as the first and third leading causes of premature disability and mortality in Russia, respectively.(IHME, 2013) It is characterized as a complex concentrated epidemic, with an prevalence reaching 1% among adults.(UNAIDS, 2012) Though initially concentrated and still prevalent among injecting drug users (IDU) and their sex partners, (Burchell, Calzavara, Orekhovsky, & Ladnaya, 2008; Lowndes, Alary, & Platt, 2003; MoH Russian Fed, 2008; Rhodes et al., 2002; Rhodes et al., 2003) transmission was later reported among men who have sex with men (MSM).(UNAIDS, 2012)

Recent studies have identified significant risks for HIV and prevalence estimates of 5.5–6.0% among MSM in St. Petersburg and Moscow.(S. Baral et al., 2010; S. Baral et al., 2012; Kelly et al., 2002) HIV prevalence was greater (16%) among Moscow male sex workers with estimated incidence of 4.8/100PY.(S. Baral et al., 2010; S. Baral et al., 2012) Few studies of MSM in Russia assess migration status. Approximately 40% of a cohort population of male sex workers in Moscow was not originally from Russia and only 16% of the sample was originally from Moscow.(S. Baral et al., 2010) Beyond this, most epidemiologic studies of MSM in Russia have not reported detailed ethnicity or nationality data.

To better characterize the HIV epidemic, identify targets for prevention, and provide HIV counseling and testing to MSM in Moscow, our collaborative group initiated the BeSafe study in 2010. The first phase of the study included formative, qualitative research to better understand the subgroups who comprise the MSM population, so as to inform subsequent recruitment, quantitative assessments, and intervention efforts.

Methods

Qualitative research methods included in-depth interviews and focus group discussions conducted between April – June 2010. Qualitative participants were purposively selected men recruited from various venues, referred from health, social or gay organizations, recruited from the internet, and through peer recruitment methods.

Study Site

Interviews and focus groups were conducted in a private clinic, centrally located and known to be friendly to LGBT populations.

Study Population

Eligibility requirements included men, aged 18 years or older, having resided in Moscow for at least one year, and reported same sex practices within the last year. For this analysis, we selected transcripts from 9 interviews and 3 focus groups (12 participants) self-identified as immigrant or migrant MSM, from the total of 25 interviews and 23 focus group discussions (97 participants)

Measures and analysis

Semi-structured interview and discussion guides were used for interviews and discussions, concentrating on several key areas: social experiences living in Moscow as a MSM; experiences of discrimination and stigma; sexual practices; knowledge and use of HIV/STI prevention methods; and experiences pre- and post-migration.

Interviewers and group facilitators were trained to provide details on the study purpose, obtain verbal informed consent prior to data collection, and provide information about additional local HIV prevention resources. Discussions and interviews were 60–90 minutes in duration and conducted in Russian. They were recorded, with permission, and later transcribed for analysis. Anonymous audio transcriptions and summary notes were translated to English for coding and analysis using Atlast.ti (Cincom Systems, Berlin).

Data analysis began with pre-identified codes, based on qualitative guide questions, and then followed a grounded theory approach, allowing for in-depth exploration of emerging themes in the participants’ narrative responses.(Strauss & Corbin, 1998) Topical codes were applied to sort quotations according to key domains and open interpretive coding was utilized to identify and analyze any emerging themes observed within and between topical areas. Codes were then reviewed a second time to map to the socio-ecologic framework, adapted from Baral and colleagues,(S Baral, Logie, Grosso, Wirtz, & Beyrer, 2012) for analysis of proximate and distal factors related to risk for HIV acquisition and transmission.

Quotations have been selected to highlight key themes with additional quotations provided in the Online Supplement (referenced in the text below as Q#). References to specific ethnicity and origin have been removed to prevent any potential negative social consequences towards minority groups that could result from discussing sensitive topics.

Human Subjects Protection

The study was conducted in partnership with a local non-governmental organization, AIDS Infoshare, and approved by both the Ethics Committee of the State Medical University, IP Pavlov, Saint Petersburg, Russia and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board, Baltimore, Maryland.

Findings

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the immigrant/migrant interview and focus group participants. Among the participants, 13 different ethnicities or countries of origin were represented and age range was 19 to 40 years.

Table 1.

Description of immigrant/migrant qualitative participants

| Participant type: | Age (years) |

Reported Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|

| Focus group 1 participant | 38 | Armenian |

| Focus group 1 participant | 42 | Daghestani |

| Focus group 1 participant | 26 | Yazidi |

| Focus group 1 participant | 35 | Uzbek |

| Focus group 2 participant | 24 | Ukrainian |

| Focus group 2 participant | 26 | Tajik |

| Focus group 2 participant | 24 | Uzbek |

| Focus group 2 participant | 28 | Russian (internal migrant) |

| Focus group 3 participant | 24 | Tajik |

| Focus group 3 participant | 19 | Daghestani |

| Focus group 3 participant | 29 | Afghani |

| Focus group 3 participant | 28 | Tajik |

| In-depth interview participant | 40 | Armenian |

| In-depth interview participant | 35 | Tajik |

| In-depth interview participant | 24 | Tajik |

| In-depth interview participant | 25 | Belarus |

| In-depth interview participant | 25 | Chechen |

| In-depth interview participant | 38 | Belarus |

| In-depth interview participant | 27 | Azerbaijani |

| In-depth interview participant | 29 | Ingush |

| In-depth interview participant | 28 | Tatar |

| Total: 21 participants | Median age: 28 years (Range: 19–40) | |

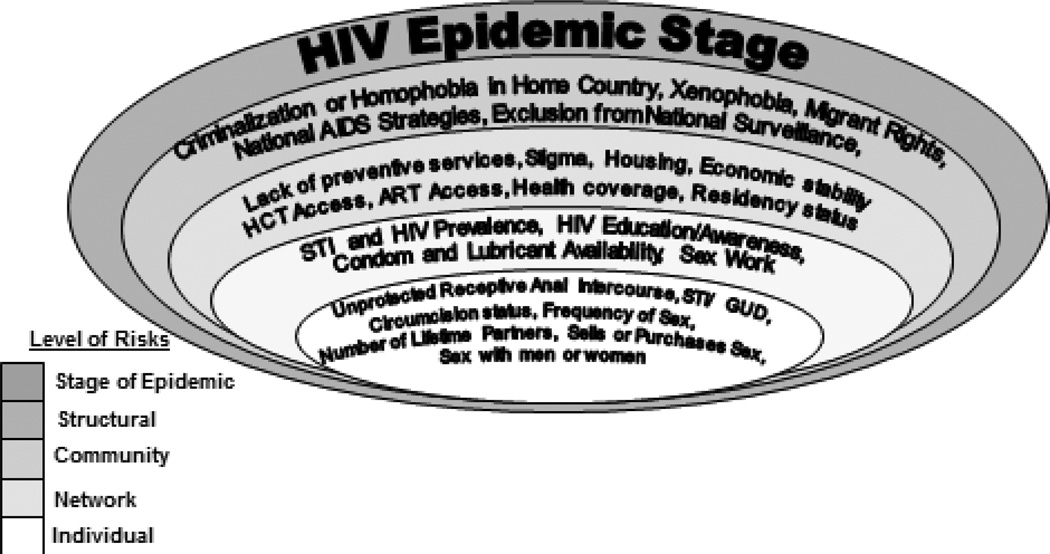

Analysis of coded transcripts suggest that macro-level factors play a highly influential role in the individual social and sexual risk factors for HIV /STI transmission and acquisition among immigrant/migrant MSM residing in Moscow. Figure 2, presents the socio-ecological layers that influence risk for infection among these participants. We first present the most distal layer, public policy and broader structural factors, and move toward the inner, individual layer, describing each layer with examples.

Figure 2.

Modified ecological model for HIV risk in MSM

Adapted from Baral and colleagues’ Modified Social Ecological Model(S Baral et al., 2012)

Public policy and structural

Salient themes included the effects of economic and migration status, the presence of homophobia in the home country/region, and xenophobia and discrimination of immigrant/migrant populations in Moscow.

Immigrant/migrant men reported relocating to Moscow primarily to seek economic opportunity. Several participants reported finding themselves in subsequently worse conditions, experiencing difficulty in attaining employment, job loss, or theft of property.

KI1019, Age 27 yrs. People come to Moscow to earn money. They decide to go back home, but documents-money is stolen from them. They have nowhere to go. They have no money in their pockets. No work. They need only one thing – to go and eat somewhere.

For some, poor living conditions, the need for food and accommodations, and lack of resources and support upon entry to Moscow led to sex work for financial gain and/or lodging (Q1). Sometimes sex work was conducted for pleasure, but was not always the case (Q2).

Other motivations for migration to Moscow were reported, ranging from persecution and blackmail in the home country (Q3–4) to general desire for freedom of sexuality and opportunity.

KI1021, Age 29 yrs. [At home] It was broadcasted by [national TV channel] that three guys were murdered…killed for being gays. But nobody says anything. Even these law-enforcement agencies, if they saw how a person was murdered, they wouldn’t carry out investigation. But if he is [gay] he is nobody, he is buried and forgotten.

FGD01 I’m in Moscow for 11 years already. Frankly speaking the initial reason for me coming to Moscow is exactly gay-life. It’s because I’m from a provincial town where there was no gay-life as it is.

Experiences of homophobia and violence on the basis of sexuality were not reported in Moscow, though some reported perceived stigmatization of homosexuality. Other experiences of stigma and social violence, however, were related to xenophobia. This did not appear to manifest as physical violence in Moscow, according to participants, though immigrant/migrants were vulnerable to police harassment and exploitation (Q5).

Stigma and human rights concerns in the home country were also associated with diagnosis of HIV infection, where a positive test could result in physical and social isolation (Q6). For many, this led to an avoidance of HIV testing. Because of reporting requirement in Russia, participants also feared refusal of entry or expulsion from Russia if diagnosed with HIV infection (Q18).

Community

Community-level factors include the range of cultural, social, religious, geographic or other social ties that facilitate or hinder realization of health and wellbeing.(S Baral et al., 2012) For participants of this study, relevant communities included those in Moscow as well as in the home country/region. While participants reported greater sexual freedom in Moscow, many felt there was significant need to avoid others of their same ethnicity, even in Moscow, for fear of unintentional disclosure and family rejection (Q7–8). Focus group participants reported that men of certain ethnic groups often gather together to socialize, but ‘gays do not’. Some men maintained a heterosexual identity when socializing or simply avoided discussion of sexual practices (Q9).

KI1021, Age 29 yrs. When people move to Moscow, there is freedom… But, [migrant MSM] are afraid that if somebody of your nationality sees you in Moscow, they may say it at home and that’s the “end!”

Several ethnic MSM exhibited internalized homophobia that seemed to be related to shame and fear of disclosure to family, friends, and broader society. Often, this manifested in overt disdain for other gay men. Some considered insertive sex with men only acceptable for financial purposes, or while in prison (Q10–11).

KI1019, Age 27 yrs. Moscow gays, you know, they… They are not people, I don’t consider them people, they are like some animals. Eight people, ten people are invited to one sauna. One rents the whole sauna and jumps like a rabbit here and there, here and there…. They don’t care, because it’s not prohibited by law. It’s their disease. As a drug-user, drugs every day.

Overall, among migrant and Moscovite MSM, there were mixed perceptions about the MSM community and the support it offered (Q12).

Network

Network-level factors were predominantly associated with sexual partnerships and relationships with sex work clientele. Sexual relationships were hidden, often short-term and in risky settings. Others considered short-term relationships with high numbers of partners as simply a matter of preference (Q13).

With respect to sex work, there was a high demand for ethnic populations due to novelty, perceived willingness to participate in certain sexual practices, and perceptions that low social connectedness would prevent migrant male sex workers from blackmailing clients (Q14).

KI1016, Age 25 yrs. The messages board at [website] that are posted by ‘natives from Caucasus’ proposing sex for payment are often placed by persons not of Caucasus origin, but may be, for example, Tadjiks or Uzbeks. The word “kavkazets” (Caucasian) that is used in the title of an advert attracts more potential clients.

For those involved in sex work, the physical, sexual and social risks were highly variable and influenced by the mode or venue for advertising and selling sex, as well as the clientele who frequented these venues. Venues ranged from the traditional pleshkas, public areas that are known for sex work, public toilets at railway/metro stations and saunas, to more technology-based sources (Q15). Meeting clients via internet or pleshkas conveyed the possibility of different sexual and physical risks, including violence, though most reports of violence were hearsay. Vicarious experiences of drugging with clonidine for rape or theft was reported by several participants.

KI1021, Age 29 yrs. Criminal elements give themselves for gays, may pull a fast one for a big sum of money. There are those who add clonidine to drinks. You drink clonidine - you smile and disappear. And everything you had - money, telephone etc. they will take away from you. If it happens at the flat, they take everything possible. You wake up in the morning and you remember nothing.

Individual

The effects of structural, community, and network factors become apparent amidst individual risks for HIV/STI transmission and acquisition. Low prevention and health seeking behaviors were related to disclosure fears. Transactional sex with a high number of anonymous partners was reported for financial incentive or housing needs.

Condom use was reported often, but in-depth discussions revealed the decision was based on perceptions of the partner or client, including appearance of infection or the venue where they met (Q16). Ineffective prevention methods, such as washing and disinfecting after sex, or using soaps in place of lubricants were also reported.

KI1011, Age 35 yrs. A man called me and he asks [for sex] without a condom. I say, we decide on the spot. I want to see the person. I know myself from my side… Even if I make sex with somebody unknown, I follow the whole procedure, to wash there, disinfect, do everything, well. And, if he proposes without a condom and a good sum, [I would say] ‘no’. I already noticed on his body diseases. It’s “no” already, I would not start without a rubber by any means.

Some men doubted that men living with HIV infection would willingly disclose their serostatus to sexual partners, while others still felt the risk was generally inherent.

FDG02 The problem is that the attitude towards a person can change only when he knows that he is HIV-infected, but continues on purpose to have sex with other people, infecting them on purpose. He doesn’t practice safe sex, such a [liar]… I will take my risk, either I will go with him or not. I take my risk. Either a condom will get torn or not.

Reports of HIV testing frequency were mixed. Some, particularly those involved in sex work, reported regular HIV testing (Q17). Others avoided testing due to the shame associated with having engaged in HIV risk behaviors or cost, or fear of isolation or expulsion. For entry or to avoid expulsion, some immigrant/migrant men are known to obtain false documents and results for their registration (Q18).

Discussion

Stigma and violence related to homophobia in participants’ homelands, and concerns about xenophobia and distrust of migrants in Moscow, emerged as key themes. These issues were connected to individual level sexual and social risks among ethnic minority MSM. The perceived need to prevent disclosure of sexual practices to communities in the home country often led to concealed behaviors for these men. Such concealment, may impact access and uptake of important HIV prevention and testing services.

Understanding health risks among immigrant/migrant MSM are important as access to government health services is determined by the propiska and other relevant documents. Though the propiska, one of the internal residency documents required to access public health services, was formally repealed in 1993, the ‘propiska-like’ registration system is still considered to be in practice in Moscow.(Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, 2003) Immigrant/migrant men may not be registered according to this system and may not afford private clinic fees, ultimately reducing their access to HIV prevention services.(Todrys & Amon, 2009) The perceived implications of a positive HIV test result, e.g. expulsion from Russia, serve as additional barriers to HIV testing.

Participants expressed a range of sexual identities, sexual preferences, and risk behaviors. Several participants were married to women. Orientations ranged from completely heterosexual to completely homosexual. The significant heterogeneity and intolerance of homosexuality among those who did not report gay identities was notable. To date, most HIV research among MSM in Russia have used venue-based recruitment,(Amirkhanian et al., 2006; Amirkhanian, Kelly, et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2002) which may limit the inclusion of heterogeneous and potentially high-risk MSM.(Magnani, Sabin, Saidel, & Heckathorn, 2005) HIV prevention programs should dually be flexible to the range of identities and partnerships among MSM.

These findings suggest that socio-behavioral and sexual risks should be taken into account during provision of services to immigrant/migrant populations in Moscow and across Russia. The International Organization for Migration has substantial funds allocated to assess risks related to HIV/STI among migrant populations,(IOM, 2012) suggesting an opportunity to clearly assess the full range of HIV/STI risks and provide targeted prevention to migrant populations, including migrant MSM. A range of interventions, including condom and condom-compatible lubricants, HIV testing and counseling, and treatment as prevention, are recommended interventions for MSM.(Sullivan et al., 2012) The willingness of some men to socialize with immigrants/migrants of other countries may provide opportunities for peer-based prevention approaches.(ECDC, 2009)

Findings should also be considered within the recently evolving political climate. While homosexuality is no longer criminalized in post-soviet law, there remains uncertainty about the future as new laws have restricted LGBT and human rights organizations,(Herszenhorn & Roth, 2013) limited LGBT content on the Internet,(HRW, 2012, 2013; Schwirtz, 2012) and restricted international funding for all non-governmental organizations, including AIDS Service organizations and LGBT groups.(ICNL, 2012; Russian Federation, 2012) Recent violence targeting LGBT populations suggest that the environment may be worsening.(AP, 2012; Roth, 2012)

Limitations

The eligibility requirement for one year of residency excluded recent immigrant/migrants and short-term residents in Moscow. Some responses may have been influenced by social desirability biases, though given the extreme experiences we heard, we believe these biases were minimized as participants became comfortable during the interview process. The implementation of study activities by a non-governmental organization likely reduced participants’ concerns for privacy and confidentiality. Details on origin were deleted from quotes to reduce potential social harms.

Conclusions

These findings helped to develop internet-based and respondent-driven sampling recruitment strategies to reach a range of Moscovite, migrant, and immigrant MSM who express a range of sexual orientations, preferences, and HIV/STI risks. The importance of anonymity and confidentiality to these participants suggested that these rights be paramount and emphasized in all research and HIV testing activities in Russia. Further research and health programming for MSM in Russia should also take these findings into consideration, particularly in cities where immigrant/migration is an important component of society.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank SANAM clinic and Tatiana Bonderenko for insight, support, and use of the SANAM clinic for conduct of qualitative research and the Be Safe study. We extend our appreciation to Ronald Stall of the Center for LGBT Health Research at University of Pittsburgh for his contribution into the study measures. We are deeply thankful to the participants who contributed their time and personal experiences to this study.

Funding:

Funding for this study came from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH R01 MH085574-01A2) “High Risk Men: Identity, Health Risks, HIV and Stigma” funded from 2009 – 2014.

Footnotes

Contributions

CB, AW, CZ, NG, VM, AP, and CL collaborated in the design and oversight of the overall study. AW, CZ, and CL contributed to the design and analysis of qualitative research. KD conducted in-depth interviews and focus group discussions. AW wrote the initial drafts of this manuscript. All authors had full access to the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and all take responsibility for its integrity as well as the accuracy of the analysis.

References

- Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Kirsanova AV, DiFranceisco W, Khoursine RA, Semenov AV, Rozmanova VN. HIV risk behaviour patterns, predictors, and sexually transmitted disease prevalence in the social networks of young men who have sex with men in St Petersburg, Russia. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2006;17(1):50–56. doi: 10.1258/095646206775220504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhanian YA, Kelly JA, Kuznetsova AV, DiFranceisco WJ, Musatov VB, Pirogov DG. People with HIV in HAART-era Russia: transmission risk behavior prevalence, antiretroviral medication-taking, and psychosocial distress. AIDS and behavior. 2011;15(4):767–777. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9793-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amirkhanian YA, Kuznetsova AV, Kelly JA, Difranceisco WJ, Musatov VB, Avsukevich NA, McAuliffe TL. Male labor migrants in Russia: HIV risk behavior levels, contextual factors, and prevention needs. Journal of immigrant and minority health / Center for Minority Public Health. 2011;13(5):919–928. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9376-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AP. 3 Russians injured in attack on Moscow gay club in 7th violent attack on gays this year. Associated Press. 2012 Oct 12; Retrieved from http://bigstory.ap.org/article/3-russians-injured-attack-moscow-gay-club.

- Baral S, Logie C, Grosso A, Wirtz AL, Beyrer C. Modified Social Ecological Model: A tool to guide the assessment of risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482. (Accepted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S, Kizub D, Masenior NF, Peryskina A, Stachowiak J, Stibich M, Beyrer C. Male sex workers in Moscow, Russia: a pilot study of demographics, substance use patterns, and prevalence of HIV-1 and sexually transmitted infections. AIDS care. 2010;22(1):112–118. doi: 10.1080/09540120903012551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baral S, Sifakis F, Peryskina A, Mogilnii V, Masenior NF, Sergeyev B, Beyrer C. Risks for HIV infection among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 2012;28(8):874–879. doi: 10.1089/AID.2011.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burchell AN, Calzavara LM, Orekhovsky V, Ladnaya NN. Characterization of an emerging heterosexual HIV epidemic in Russia. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2008;35(9):807–813. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181728a9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre on Migration Policy and Society. Causes and characteristics of transit migrations, crossing the fringes of Europe: Transit migration in the EU's neighborhood. In: Centre on Migration Policy and Society, editor. Working Paper. Vol. No. 33. Oxford: Univ of Oxford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- ECDC. ECDE Technical Report: Migrant health: Access to HIV prevention, treatment, and care for migrant populations in EU/EEA countries. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herszenhorn D, Roth A. Russian Authorities Raid Amnesty International Office. NY Times. 2013 Mar 25; Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/26/world/europe/russian-authorities-raid-amnesty-international-office.html?_r=0.

- HRW. Russia: Reject Homophobic Bill. Human Rights Watch. 2012 Dec 10; Retrieved from www.hrw.org/news/2012/12/10/russia-reject-homophobic-bill.

- HRW. World Report 2013. NY: Human Rights Watch; 2013. Country Summary: Russia. [Google Scholar]

- ICNL. [Retrieved 24 Nov, 2012];NGO Law Monitor. 2012 from http://www.icnl.org/research/monitor/russia.html.

- IHME. Global Burden of Disease. Seattle: Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; 2013. Global Burden of Disease Profile: Russia. [Google Scholar]

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. Russia: Information on the propiska or propiska-like registration system in Russia; regions with propiska-like registration systems; governing authority; its application in practice; effect on individuals lacking registration; reports of corruption in registration. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration, editor. IOM. Migration Initiatives 2012. Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, Amirkhanian YA, McAuliffe TL, Granskaya JV, Borodkina OI, Dyatlov RV, Kozlov AP. HIV risk characteristics and prevention needs in a community sample of bisexual men in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS care. 2002;14(1):63–76. doi: 10.1080/09540120220097946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowndes CM, Alary M, Platt L. Injection drug use, commercial sex work, and the HIV/STI epidemic in the Russian Federation. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2003;30(1):46–48. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200301000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnani R, Sabin K, Saidel T, Heckathorn D. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 2):S67–S72. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000172879.20628.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MoH Russian Fed. Country Progress Report of the Russian Federationon the Implementation of the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS (Report Period: Jan 2006 – December 2007) Moscow: Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mosmuller Herbert. Migrants Turn Moscow Into Europe's Biggest City. Moscow Time. 2011 Apr 20; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.themoscowtimes.com/news/article/migrants-turn-moscow-into-europes-biggest-city/435371.html.

- Radio Free Europe. Ukrainian antigay bill clears first hurdle. Radio Free Europe. 2012 Oct 02; Retrieved from http://www.rferl.org/content/ukraine-antigay-bill-clears-first-hurdle/24727046.html.

- Rhodes T, Lowndes C, Judd A, Mikhailova LA, Sarang A, Rylkov A, Renton A. Explosive spread and high prevalence of HIV infection among injecting drug users in Togliatti City, Russia. AIDS. 2002;16(13):F25–F31. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200209060-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Mikhailova L, Sarang A, Lowndes CM, Rylkov A, Khutorskoy M, Renton A. Situational factors influencing drug injecting, risk reduction and syringe exchange in Togliatti City, Russian Federation: a qualitative study of micro risk environment. Social science & medicine. 2003;57(1):39–54. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth A. Masked men attack crowd at gay bar in Moscow. New York Times. 2012 Oct 12; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/13/world/europe/masked-thugs.

- Introducing Amendments to Certain Legislative Acts of the Russian Federation Regarding the Regulation of Activities of Non-commercial Organizations Performing the Function of Foreign Agents. 2012

- Schwirtz M. Anti-gay law stirs fears in Russia. New York Times. 2012 Feb 29; 2012. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/world/asia/anti-gay-law-stirs.

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Grounded theory methodology: an overview. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Strategies of qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 158–183. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Carballo-Dieguez A, Coates T, Goodreau SM, McGowan I, Sanders EJ, Sanchez J. Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):388–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todrys KW, Amon JJ. Within but without: human rights and access to HIV prevention and treatment for internal migrants. Global Health. 2009;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penal Code 1997/98 (revised 2000), Article 135, Muzhelozhstvo. 2000

- UNAIDS. [Retrieved Nov, 2012];Russian Federation: HIV and AIDS Estimates. 2012 (2009) from http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/russianfederation/

- Article 120. Besoqolbozlik* (Homosexual Intercourse) 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Williams L, Aktoprak S. In: Migration between Russia and the European Union: Policy implication from a small-scale study of irregular migrants. International Organization for Migration, editor. Moscow: 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.