Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Obesity and hypertension, known pro-inflammatory states, are identified determinants for increased retinal microvascular abnormalities. However, the molecular link between inflammation and microvascular degeneration remains elusive. Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) is recognised as an activator of the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome. This study aims to examine TXNIP expression and elucidate its role in endothelial inflammasome activation and retinal lesions.

Methods

Spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and control Wistar (W) rats were compared with groups fed a high-fat diet (HFD) (W+F and SHR+F) for 8–10 weeks.

Results

Compared with W controls, HFD alone or in combination with hypertension significantly induced formation of acellular capillaries, a hallmark of retinal ischaemic lesions. These effects were accompanied by significant increases in lipid peroxidation, nitrotyrosine and expression of TXNIP, nuclear factor κB, TNF-α and IL-1β. HFD significantly increased interaction of TXNIP–NLRP3 and expression of cleaved caspase-1 and cleaved IL-1β. Immunolocalisation studies identified TXNIP expression within astrocytes and Müller cells surrounding retinal endothelial cells. To model HFD in vitro, human retinal endothelial (HRE) cells were stimulated with 400 μmol/l palmitate coupled to BSA (Pal-BSA). Pal-BSA triggered expression of TXNIP and its interaction with NLRP3, resulting in activation of caspase-1 and IL-1β in HRE cells. Silencing Txnip expression in HRE cells abolished Pal-BSA-mediated cleaved IL-1β release into medium and cell death, evident by decreases in cleaved caspase-3 expression and the proportion of live to dead cells.

Conclusions/interpretation

These findings provide the first evidence for enhanced TXNIP expression in hypertension and HFD-induced retinal oxidative/inflammatory response and suggest that TXNIP is required for HFD-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and the release of IL-1β in endothelial cells.

Keywords: Caspase-1, High-fat diet, Hypertension, IL-1β, Inflammasome, Inflammation, NLRP3, Obesity, Oxidative stress, Retinal acellular capillaries, TXNIP

Introduction

Obesity and hypertension, the hallmarks of metabolic syndrome characterised by insulin resistance, are identified as independent risk factors for the development of retinopathy [1, 2]. Population studies have established obesity and hypertension as determinants for increased incidence of retinopathy and retinal microvascular abnormalities in the general non-diabetic population [3, 4]. Increased energy intake and consumption of saturated/trans-fat and cholesterol are the most plausible reasons behind the alarming epidemic rates of obesity and metabolic syndrome [5]. High levels of plasma NEFA, and the saturated fatty acid palmitate in particular, are the result of high fat intake [6, 7] and contribute to metabolic syndrome-associated inflammation and insulin resistance [8, 9]. Palmitate has been shown to induce the activation of the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome [6, 10, 11], a well-established multi-protein complex responsible for instigating obesity-induced inflammation [12, 13]. Activated NLRP3 oligomerises with the ASC (apoptosis-associated specklike) adaptor protein, which recruits procaspase-1, allowing its autocleavage and activation. Activated caspase-1 (cleaved caspase-1) enzyme in turn cleaves upregulated premature pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 and causes their release [14].

Thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) is the endogenous inhibitor and regulator of thioredoxin, a major cellular antioxidant and anti-apoptotic system [15]. TXNIP expression, a well-established mediator of insulin resistance, has been shown to be consistently elevated in the muscles of insulin-resistant and diabetic individuals [16, 17]. In THP-1 human macrophages, inflammasome activators induce the dissociation of TXNIP from thioredoxin in a reactive oxygen species (ROS)-sensitive manner, allowing it to bind and activate NLRP3 [18]. We and others have demonstrated a pivotal role of enhanced retinal TXNIP expression in the induction of the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1) and TNF-α, in vivo and in isolated retinal cultures [19–22]. Increased levels of IL-1β were shown to increase the number of retinal acellular capillaries in vivo [23]. Nevertheless, there is a gap in knowledge concerning whether TXNIP can mediate high-fat diet (HFD)-induced retinal inflammasome activation and whether this can occur directly within retinal endothelial cells to trigger inflammation and microvascular degeneration. Here, we test the hypothesis that HFD, as an essential component of the metabolic syndrome, results in upregulation of retinal TXNIP expression, NLRP3-inflammasome activation and microvascular degeneration in vivo and in vitro.

Methods

Animal preparation

All animal studies were in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) and the Georgia Reagents University Animal Care and Use Committee. Retinas were obtained from two separate animal studies that examined the effect of HFD, either alone or in combination with hypertension. In the first study, 8-week old male Wistar Kyoto control rats (W) and spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) (Charles River, Wilmington, MA, USA) were randomly assigned to four groups: W and SHR control groups, fed ad libitum with normal rat chow (7% fat) for 10 weeks; W+F and SHR+F groups, fed with HFD (36 g %, 251 kJ [60 kcal] % fat, F2685 Bioserv [Frenchtown, NJ, USA]) for 10 weeks. Rats were weighed weekly and metabolic variables, plasma insulin and blood glucose were measured and published previously [24]. In the second study, retinas were obtained from sham control 5-week-old male Wistar control rats (W) (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA) fed ad libitum for 8 weeks with an isoenergetic control diet (10% fat), and compared with retinas from W group rats fed with HFD (24 g %, 188 kJ [45 kcal] % fat, D12451 Research Diets [New Brunswick, NJ, USA]) (W+F) for 8 weeks. Rats were weighed weekly and metabolic variables were examined and published recently [25]. Of note, in both studies, HFD resulted in significant increases in total body weight as an indicator for obesity. HFD induced increases in plasma cholesterol levels in the first study [24] but not in the second study [25] and there was no effect on blood pressure, blood glucose levels or insulin resistance in either study.

Determination of retinal acellular (degenerated) capillaries

Retinal vasculatures were isolated as described previously [26]. Transparent vasculatures were laid out on slides and stained with periodic acid-Schiff and haematoxylin. Acellular capillaries were identified as capillary-sized blood-vessel tubes having no nuclei anywhere along their length. The number of acellular capillaries was averaged from eight different fields of the mid-retinal area and calculated as the average number/mm2 of retinal area using AxioObserver.Z1 Microscope (Zeiss North America, Thornwood, NY, USA).

Immunoprecipitation and western blot analysis

Retinas were lysed in modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and 30 μg of total protein were separated by SDS-PAGE. Antibodies used were: anti-TXNIP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA and Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), anti-NFκB p65 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Anti-TNF-α (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), Anti-caspase-1, Anti-NLRP3 (Enzo lifesciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA), Anti-cleaved caspase-3 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and anti-IL-1β (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA). One-hundred microgrammes of total protein was immunoprecipitated with anti-TXNIP antibody (5 μg/ml) and incubated with A/G agarose beads overnight. Precipitated proteins were analysed by SDS-PAGE and blotted with primary antibodies (anti-TXNIP and anti-NLRP3). Band intensities were quantified using Alpa Innotech Fluorchem (Santa Clara, CA, USA) imaging and densitometry software and expressed as relative optical density (ROD).

Detection of lipid peroxides

Levels of lipid peroxides (malondialdehyde, MDA) were assayed using thiobarbituric acid reactive substances as described previously [26]. The Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) was performed to determine the protein concentration of retinal lysate. Lipid peroxides were expressed in μmol MDA/mg total protein.

Detection of retinal nitrative stress

Slot-blot analysis was used to measure nitrative stress marker, nitrotyrosine (NY) as described previously [26]. Five microgrammes of retinal homogenate were immobilised onto a nitrocellulose membrane and reacted with polyclonal anti-NY (Calbiochem/EMD Bioscience, La Jolla, CA, USA) and ROD was calculated compared with controls.

Quantitative real-time PCR

The One-Step qRT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) was used to amplify 10 ng retinal mRNA as described previously [27]. PCR primers (listed in electronic supplementary material [ESM] Table 1) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed using a Realplex Master cycler (Eppendorf North America, Hauppauge, NY, USA). The expression of Txnip, Nlrp3, Nlrc4 and Casp1 was normalised to the 18S level and expressed relative to W control.

Immunolocalisation studies

Optimal cutting temperature compound (OCT)-frozen sections of the eyes (10 μmol/l) were fixed using 2% paraformaldehyde and reacted with the primary antibody (1:200 dilution), including polyclonal anti-TXNIP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), polyclonal anti-GFAP (Pierce Biotect, Rockford, IL, USA), monoclonal anti-GFAP, monoclonal anti-glutamine synthetase (Chemicon-Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) or negative control at 4°C overnight, followed by Oregon-green-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody or Texas-red goat anti-mouse antibody (Invitrogen). Retinal vasculature was localised using isolectin-B4 (Invitrogen). Images were collected using an AxioObserver.Z1 Microscope (Zeiss North America).

Human retinal endothelial cell culture studies

All human retinal endothelial (HRE) cell studies were in accordance with the ARVO and the Charlie Norwood Veterans Affairs Medical Center, research and ethics committee. HRE cells and supplies were purchased from Cell Systems Corporations (Kirkland, WA, USA) and VEC Technology (Rensselaer, NY, USA) as described previously [27]. Sodium palmitate (catalogue No. P9767; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in 50% ethyl alcohol solution, then added drop-wise to pre-heated 10% endotoxin- and fatty acid-free BSA (catalogue No. A8806; Sigma) in M199 at 50°C to create an intermediate stock solution of palmitate coupled to BSA (Pal-BSA). Confluent cells were switched to serum-free medium for 6 h then treated for 12 h with Pal-BSA solutions in a ratio of 1:10 to produce final concentrations of 200, 400 and 800 μmol/l of Pal-BSA. Equal volumes of 50% ethyl alcohol solution without any palmitate dissolved in BSA served as a control (BSA alone). Peroxynitrite (PN) was purchased from Calbiochem and diluted in 100 mmol/ NaOH and added at a final concentration of 100 μmol/l.

Silencing of TXNIP expression

Transfection of HRE cells with 0.6 μmol/l Txnip small interfering RNA (siRNA) was performed using Amaxa nucleofector primary endothelial cells kit (Lonza, Germany) as described previously [27]. In addition, a chemical-transfection kit was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). HRE cells (80% confluent) were incubated in the conditioned transfection medium with 300 ng of FITC-labelled scrambled (SC) or Txnip siRNA for 6 h, then left to recover in complete medium for 24 h before experiments were performed. Transfection efficiency was 70–80% for both methods as indicated by the number of cells expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) or FITC-labelled SC siRNA (data not shown). Silencing of TXNIP expression was verified by western blot analysis.

Determination of IL-1β release

Secretion of cleaved IL-1β into the HRE cell conditioned media was determined using IL-1β ELISA sensitive kit (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Briefly, equal volumes of conditioned media for each group were concentrated using Ambion10K concentration columns (Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA), then loaded into IL-1β capture antibody pre-coated wells and processed according to the manufacturer’s protocol. IL-1β concentrations were expressed as pg/ml of the cell conditioned media used.

Life and death cell viability assay

HRE cell viability was tested by a Live/Dead assay (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. A working assay solution of 4 μmol/l ethidium homodimer-1 and 2 μmol/l calcein-AM was prepared and was added to the top of each culture well for 15 min at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere (20% O2 with 5% CO2). The staining solution was removed and samples were then viewed under a Ziess fluorescence microscope with filters (494 nm, green, viable; 528 nm, red, non-viable) and the percentage was calculated.

Data analysis

Results were expressed as means ± SEM. Two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni multiple comparison test were used for testing differences among all the multiple experimental groups and for testing the interaction between the types of diet (HFD vs normal diet) across the groups of rats (W control vs SHR group, for the animal experiments) and between the presence or absence of PN across palmitate-treated or control cell groups (for the in vitro studies). Two-sided Student’s t test was used for testing differences between two experimental groups (W and W+F). Significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

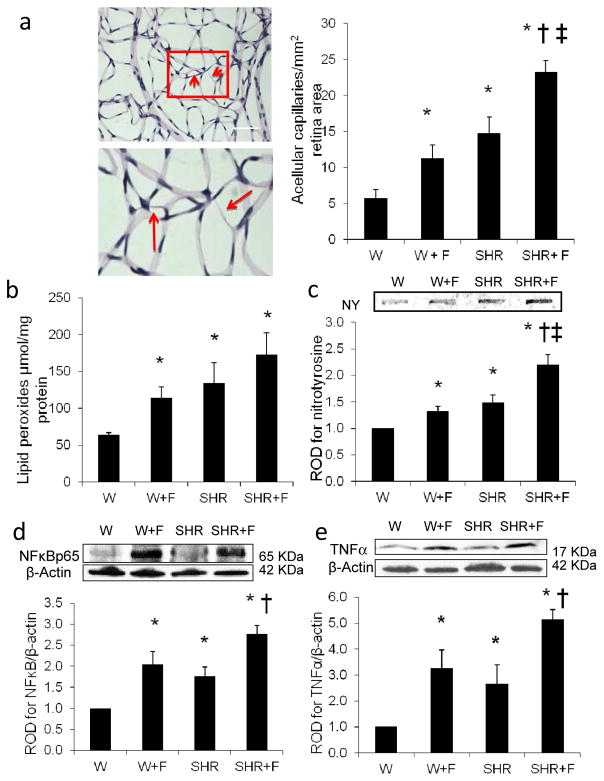

HFD causes retinal microvascular degeneration and oxidative and inflammatory stress

To assess the impact of HFD by itself or in combination with the co-morbid condition of hypertension on the development of retinopathy lesion, we examined the effect of 10 weeks of HFD in W or SHR on retinal microvascular degeneration. As shown in Fig. 1a (and ESM Fig. 1), HFD alone (W+F) significantly induced the number of acellular capillaries by twofold, compared with the control group (W). The SHR group had a significantly increased number of acellular capillaries (by 2.6-fold) compared with W, which was further exacerbated (by fourfold) upon combination with HFD. These effects were associated with increases in retinal oxidative and inflammatory stress (Fig. 1b–e). Retinal lipid peroxides were higher in the W+F group (1.7-fold) than in the control W group. The SHR and combined SHR+F groups had higher levels (2- and 2.7-fold, respectively) compared with the control W group (Fig. 1b). Retinal NY levels were higher, by 1.3- and 1.5-fold, in the W+F and SHR groups, which was exacerbated to twofold in the SHR+F, relative to the control W group (Fig. 1c). Oxidative stress occurred in parallel with a twofold increase in NFκB p65 expression in the W+F group, a 1.8-fold increase in the SHR group and a 2.8-fold increase in the combined SHR+F group, when compared with the control W group (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, levels of TNF-α, a downstream target of the NFκB pathway, were also higher in the W+F group by 3.3-fold and in the SHR group by 2.7-fold. This increase was further exacerbated in the combined SHR+F group to 5.2-fold, when compared with the control W group (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

HFD causes retinal microvascular degeneration and oxidative and inflammatory stress. (a) Representative images and quantification of retinal trypsin digests with enlarged subset identifying retinal acellular capillaries (arrows) in control rats (W) and SHR fed with normal diet or with HFD (W+F) and (SHR+F), respectively, for 10 weeks. Magnification, ×200; scale bar, 25 μm. Two-way ANOVA showed significant interaction between HFD and hypertension. Oxidative stress markers were assessed using retinal lipid peroxidation levels (b) and NY levels (c) in all groups. Two-way ANOVA showed significant interaction between HFD and hypertension in retinal NY levels. Representative blots and western blot analyses of NFκB p65 expression (d) and TNF-α expression (e) in all groups. Protein levels were normalised to β-actin and respective control group. n=4 or 5; *p<0.05 vs W; †p<0.05 vs SHR; ‡p<0.05 vs W+F

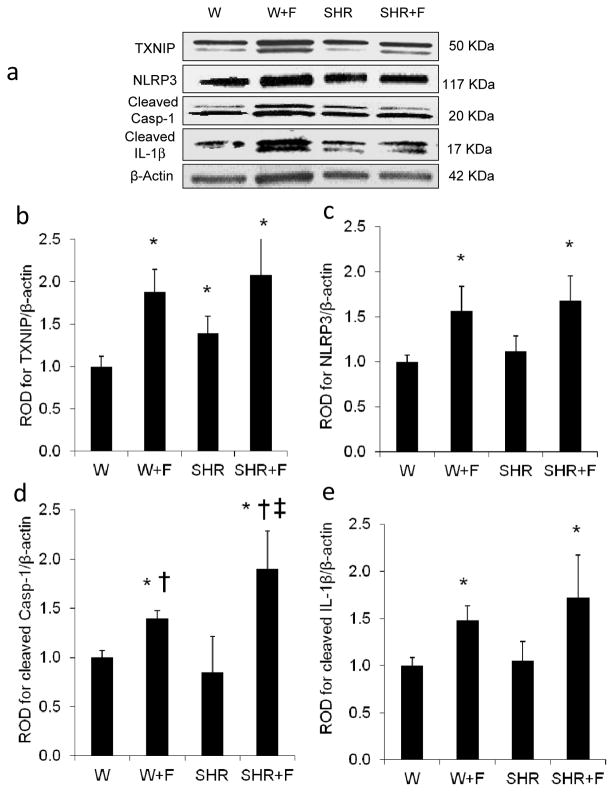

HFD induces retinal TXNIP expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation

TXNIP has been shown to be an effective link between increased oxidative stress and inflammation and activation of the innate immune response mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome [17, 18, 21]. Therefore, we sought to examine the potential involvement of HFD-induced TXNIP expression in mediating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. As shown in Fig. 2, HFD alone (W+F) or in combination with hypertension (SHR+F) significantly induced retinal TXNIP expression by 1.9- and 2-fold, and NLRP3 by 1.6- and 1.7-fold, respectively, compared with W controls (Fig. 2a–c). The expression of cleaved caspase-1 and cleaved IL-1β, the final products of inflammasome activation, was also higher in the W+F (1.4- and 1.5-fold, respectively) and in the SHR+F groups (1.9- and 1.7-fold, respectively) compared with the W controls (Fig. 2d,e). In comparison with W controls, SHR did not show significant changes in inflammasome protein expression, except for a1.4-fold increase in TXNIP (Fig. 2b). These results highlight the selective effect of HFD alone, independently from other components of the metabolic syndrome such as hypertension. Therefore, the rest of the study focused on studying the effects of HFD alone, in a parallel study using Wistar rats fed with HFD for 8 weeks.

Fig. 2.

HFD induces retinal TXNIP expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Representative blots (a) and western blot analysis of TXNIP (b), NLRP3 (c), cleaved caspase-1 (Casp-1) (d) and cleaved IL-1β (e) protein levels in retinas of control rats (W) or SHR fed with normal diet or HFD (W+F and SHR+F) for 10 weeks. Protein levels were normalised to β-actin and respective W controls. n = 3–8; *p<0.05 vs W; †p<0.05 vs SHR; ‡p<0.05 vs W+F

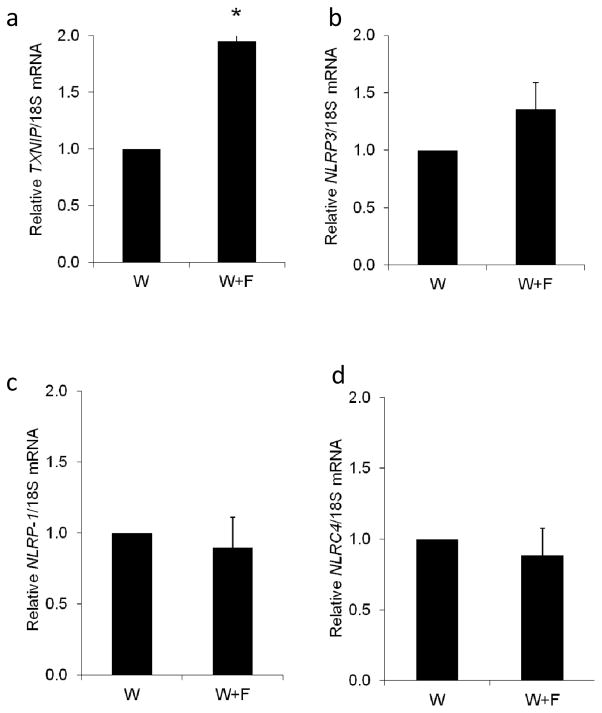

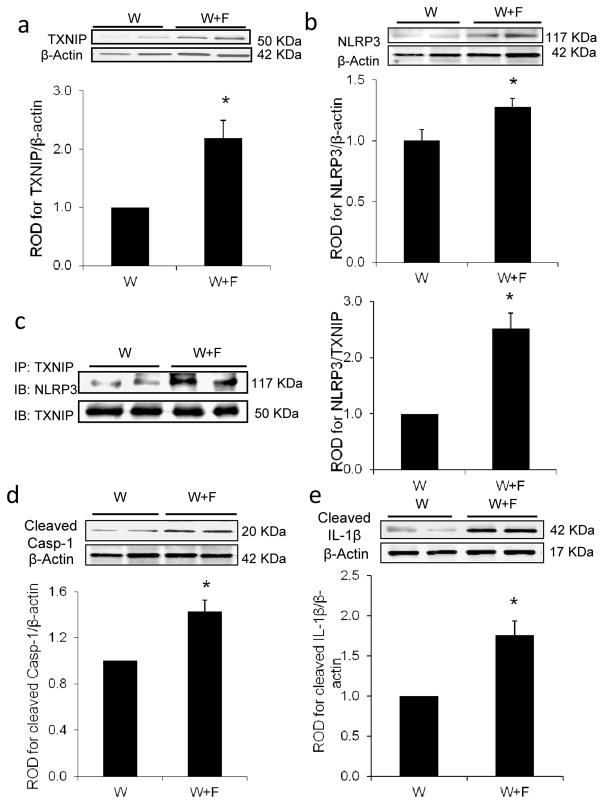

HFD induces TXNIP–NLRP3 interaction associated with retinal inflammasome activation

Other inflammasome members, such as NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing-1 (NLRP1) and NOD-like receptor CARD containing-4 (NLRC4), have been also suggested to play a role in HFD-induced inflammatory pathologies [28, 29]. At the mRNA level, HFD induced a significant twofold increase in Txnip mRNA expression (Fig. 3a) and a strong trend in the expression of Nlrp3 mRNA (Fig. 3b). However, the HFD had no effect on Nlrp1 (Fig. 3c) or Nlrc4 mRNA expression levels (Fig. 3d). At the protein expression and interaction level, HFD-induced a twofold increase in TXNIP expression (W+F) compared with W controls (Fig. 4a). This effect was associated with a 1.3-fold increase in the expression of NLRP3, the intracellular receptor for the inflammasome (Fig. 4b) and a 2.5-fold increase in TXNIP–NLRP3 interaction, as assessed by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 4c). Moreover, HFD stimulated the expression of cleaved caspase-1 and cleaved IL-1β by 1.4- and 1.7-fold, respectively, compared with the control W group (Fig. 4d,e). These results suggest that TXNIP-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome occurs in the retina in response to HFD

Fig. 3.

Gene expression levels of Txnip (a) and other inflammasome members (Nlrp3 [b], Nlrp1 [c] and Nlrc4 [d]) in W+F rats fed with HFD for 8 weeks compared with control W rats. The HFD induced a significant increase in Txnip gene expression, compared with control, and a strong trend in that of Nlrp3. n = 3–6; *p<0.05 vs W

Fig. 4.

HFD induces TXNIP–NLRP3 interaction associated with retinal inflammasome activation. Representative blots and western blot analyses of TXNIP (a) and NLRP3 (b) protein expression in W+F rats after 8 weeks of HFD vs W controls (n=4 or 5; *p<0.05 vs W). (c) Representative blot and quantification of immunoprecipitation (IP) with TXNIP and blotting (IB) with NLRP3 showed higher association of TXNIP with NLRP3 (n=3 or 4; p<0.05 vs W), which was associated with increased cleaved caspase-1 (Casp-1) (d) and cleaved IL-1β expression (e) in W+F compared with the control W group. Protein levels were normalised to β-actin and respective wild-type controls. n=4; p<0.05 vs W

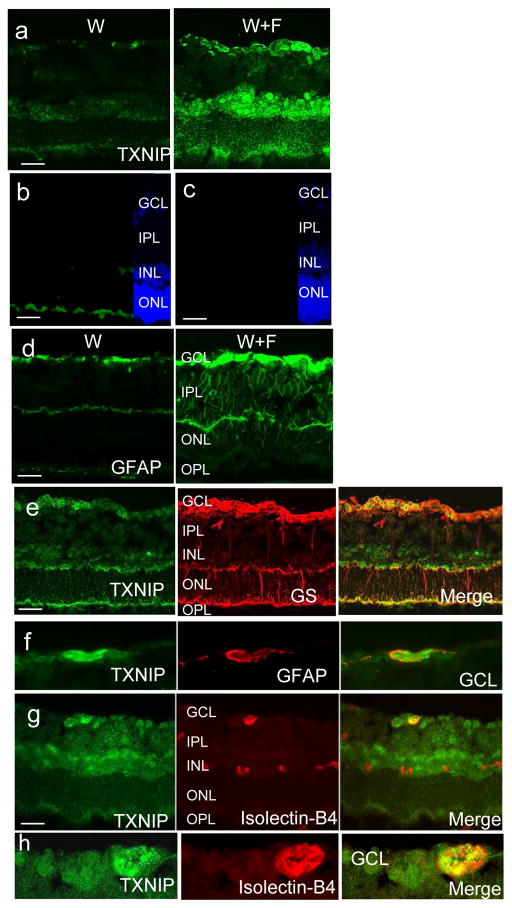

HFD-induced TXNIP expression co-localises within retinal glia and microvasculature

TXNIP expression was found to be highly glucose-responsive in retinal endothelial cells and diabetic vasculature [19, 22]. On the other hand, TXNIP-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation was reported in rat Müller glia cells cultured in hyperglycaemic conditions [21]. Hence, we next investigated the HFD-induced TXNIP expression colocalisation within different retinal layers. As shown in Fig. 5a, W+F retinas showed higher level of TXNIP expression in the ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner nuclear layer (INL) and, to a lesser extent, in the outer nuclear layer (ONL), compared with W controls. Specificity of the TXNIP antibody was demonstrated in Fig. 5b, c. Retinas from HFD also showed increased staining of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker for astrocytes and activated glial Müller cells, in the W+F group compared with the control W group (Fig. 5d). Colocalisation with glutamine synthase, a specific Müller cell marker, showed the association of TXNIP within Müller cell end feet especially within the GCL and, to a lesser extent, within the ONL (Fig. 5e). Colocalisation of TXNIP and GFAP showed strong association within the GCL, suggesting astrocytes and Müller cell endfeet surrounding retinal blood vessels (Fig. 4f). Colocalisation of TXNIP expression with the vascular endothelial marker isolectin-B4 showed strong TXNIP expression within retinal cappilaries in the GCL as well as deep retinal blood vessels in the INL (Fig. 4g,h). These findings highlight retinal endothelial cells and glial cells for HFD-induced TXNIP expression.

Fig. 5.

HFD-induced TXNIP expression co-localises within retinal vasculature and glial cells. (a) Increased TXNIP expression was observed in the GCL, INL and, to a lesser extent, ONL in the W+F group relative to the control W group. (b, c) Negative controls (b, normal rabbit serum; c, no primary antibody) showed specific binding for TXNIP antibody in the GCL and INL but not in the ONL. (d) HFD induced GFAP activation in the W+F group. Co-localisation of TXNIP with glutamine synthase (GS) (e), GFAP (f) and isolectin-B4 (g) staining showed strong association in the GCL, suggesting astrocytes, Müller cell endfeet and retinal microvasculature in GCL (enlarged in h), as well as deep retinal capillaries in the INL. Magnification, ×200, scale bars, 25 μm

Palmitate induces TXNIP and activates caspase-1/IL-1β in HRE cells

Palmitate is a commonly elevated saturated NEFA in plasma, with a well-established pro-inflammatory effect, compared with other unsaturated fatty acids [7, 30, 31]. In addition, palmitate is a major component (60%) of the saturated fatty acids both in the F2685-Bioserv and D12451-Research Diets. To test the hypothesis that HFD can directly activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in endothelial cells, we examined different levels of palmitate coupled to BSA (Pal-BSA 200 μmol/l, 400 μmol/l and 800 μmol/l) in HRE cells. Pal-BSA induced a bell-shaped dose–response curve (ESM Fig. 2), reaching a maximum response at 400 μmol/l, at which point TXNIP, cleaved caspase-1 and cleaved IL-1β expression was increased by 1.6-, 1.8- and 1.75-fold, respectively, compared with BSA controls. Of note, 800 μmol/l induced HRE cell toxicity; hence 400 μmol/l of Pal-BSA was used for the rest of the in vitro studies to probe the role of HFD in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in endothelial cells

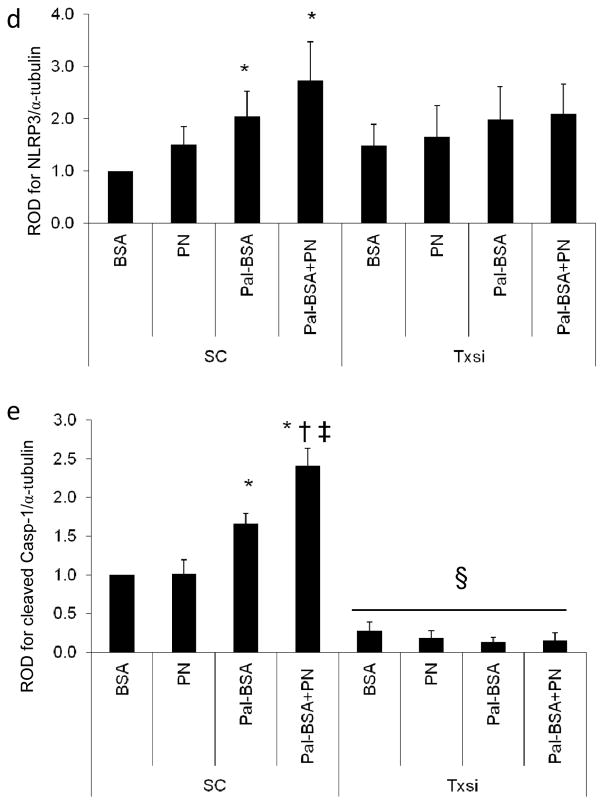

TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in HRE cells

TXNIP, as an oxidative stress sensor, was shown to induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation in a ROS-sensitive manner [18, 32]. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that TXNIP is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in HRE cells and that combining 100 μmol/l PN with 400 μmol/l Pal-BSA (Pal-BSA+PN) would exacerbate palmitate-induced inflammasome activation. Pal-BSA alone or in combination with PN resulted in significant increases in TXNIP–NLRP3 interaction (two and 2.5-fold, respectively) compared with control BSA treatment. PN alone resulted in neither a significant increase in TXNIP–NLRP3 interaction nor a significant exacerbation of the Pal-BSA effect (Fig. 6a). Next, we tested the hypothesis that TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in HRE cells. As shown in Fig 6b–e, Pal-BSA alone or in combination with PN, but not PN alone, increased TXNIP, NLRP3 and cleaved caspase-1 by 2.7-, 2- and 1.7-fold for PAL-BSA and 2.45- 2.7- and 2.4-fold for PAL+PN, respectively, relative to BSA controls in the SC siRNA group. Silencing Txnip using siRNA abolished such responses (Fig. 6b–e).

Fig. 6.

TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in HRE cells. (a) Representative blot and quantification of immunoprecipitation (IP) with TXNIP and blotting (IB) with NLRP3 after incubation with 100 μmol/l PN alone, 400 μmol/l palmitate alone (Pal-BSA) or both (Pal-BSA+PN). There was a higher association of TXNIP with NLRP3 in Pal-BSA and Pal-BSA+PN treatments only. n= 4; *p<0.05 vs BSA. Representative blots (b) and western blot analysis of TXNIP (c), NLRP3 (d) and cleaved caspase-1 (Casp-1) (e) in HRE cells transfected with either 0.6 μmol/l scrambled siRNA (SC) or Txnip siRNA after incubation with PN alone, Pal-BSA alone or both (Pal-BSA+PN) in comparison with control BSA in the SC group. TXNIP knockdown resulted in abrogation of the Pal-BSA-mediated activation of cleaved caspase-1. Two-way ANOVA showed significant interaction between PN and Pal-BSA in the combined Pal-BSA+PN group for cleaved caspase-1 expression in the SC group. Protein levels were normalised to α-tubulin and SC BSA control. n=3 or 4; *p<0.05 vs SC BSA; †p<0.05 vs SC Pal-BSA ‡p<0.05 vs SC PN-BSA; §p<0.05 vs all SC groups

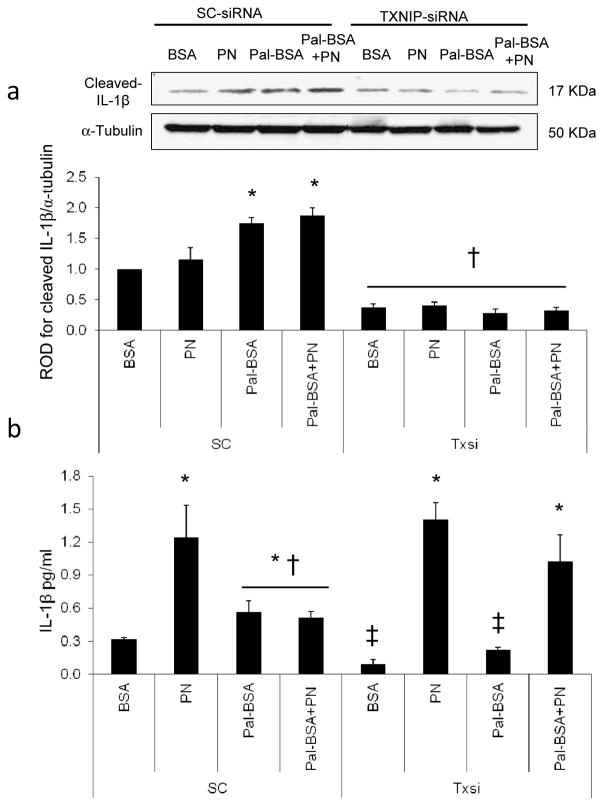

TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced IL-1β maturation in HRE cells

As shown in Fig. 7a, Pal-BSA and Pal-BSA+PN, but not PN alone, increased cleaved IL-1β expression by 1.75- and 1.9-fold, respectively, compared with control BSA in SC siRNA-treated groups. Silencing Txnip significantly abolished cellular IL-1β expression. The levels of IL-1β released into the conditioning medium were assessed by an ELISA assay. In the scrambled siRNA-treated control group, PN alone stimulated the maximum release of IL-1β by fourfold compared with BSA controls. Pal-BSA alone and Pal-BSA+PN significantly induced IL-1β release by 1.8- and 1.6-fold, respectively, relative to BSA controls. Silencing Txnip blunted the Pal-BSA-mediated, but did not affect PN alone or Pal-BSA+PN-stimulated, release of IL-1β compared with BSA control (Fig. 7b). These results indicate that TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced intracellular inflammasome activation and IL-1β maturation but not for PN-mediated mature IL-1β release.

Fig. 7.

TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced IL-1β maturation in HRE cells. Representative blot and western blot analysis of cleaved IL-1β (a) in HRE cells transfected with either 0.6 μmol/l scrambled siRNA (SC group) or Txnip siRNA after incubation with PN alone, Pal-BSA alone or both (Pal-BSA+PN), in comparison with control BSA in the SC group. TXNIP knockdown resulted in abrogation of the Pal-BSA-mediated maturation of cleaved IL-1β. Protein levels were normalised to α-tubulin and SC BSA control. n=3 or 4; *p<0.05 vs SC BSA; †p<0.05 vs all SC groups. (b) IL-1β release into the HRE cell conditioned media was quantified using an IL-1β sensitive ELISA kit. n=3–4; *p<0.05 vs SC BSA; †p<0.05 vs SC PN-BSA, Txnip siRNA PN-BSA and Txnip siRNA Pal-BSA+PN; ‡p<0.05 vs all other groups

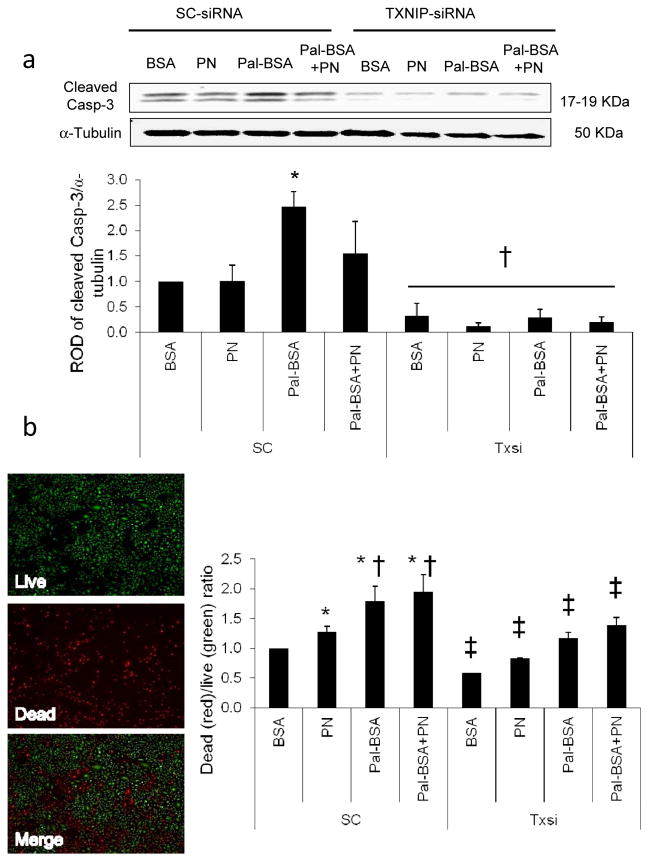

TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced apoptosis and cell death in HRE cells

We next assessed the impact of Pal-BSA-induced IL-1β release on HRE cell death. As shown in Fig. 8a, Pal-BSA induced expression of the apoptotic marker cleaved caspase-3 by 2.5-fold compared with BSA controls in the scrambled siRNA-treated group (SC). This effect was abolished by silencing Txnip. Furthermore, reduced cell viability was also observed in HRE cells after treatment with PN, Pal-BSA and Pal-BSA+PN in the SC group by 1.3-, 1.8- and 2-fold respectively, compared with SC control BSA group. Silencing Txnip expression resulted in a significant decrease in cell death in all Txnip siRNA-treated groups compared with their relative SC treatment group (Fig. 8b and ESM Fig. 3).

Fig. 8.

TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced apoptosis and cell death in HRE cells. Representative blot and western blot analysis of cleaved caspase-3 (Casp-3) (a) in HRE cells transfected with either 0.6 μmol/l scrambled siRNA (SC group) or Txnip siRNA after incubation with PN alone, Pal-BSA alone or both (Pal-BSA+PN) in comparison with control BSA in the SC group. TXNIP knockdown resulted in abrogation of the Pal-BSA-mediated increase in cleaved caspase-3 expression. Protein levels were normalised to α-tubulin and SC BSA control. n=3 or 4; *p<0.05 vs SC BSA; †p<0.05 vs all SC groups. (b) Representative image of HRE cell viability quantified using the ratio of dead cells (stained red) to the live cells (stained green) in both SC siRNA-treated and Txnip siRNA-treated groups. TXNIP knockdown resulted in significant decrease in cell death in all Txnip siRNA-treated groups compared with their relative SC treatment group. n=3; *p<0.05 vs SC BSA; †p<0.05 vs SC PN; ‡p<0.05 vs corresponding SC group

Discussion

Although clinical evidence implicates metabolic syndrome in increasing the risk for retinopathy [3, 4], data from experimental models are lacking. Therefore, we attempted to model and characterise the detrimental elements of the metabolic syndrome on the early development of retinal microvascular lesions. The current study produced several major findings: (1) HFD-induced obesity or hypertension, or their combination, resulted in early retinal microvascular lesions, significant increases in retinal TXNIP expression, oxidative stress and inflammation; (2) HFD selectively induces retinal TXNIP–NLRP3 interaction and inflammasome activation resulting in increased expression of cleaved caspase-1 and IL-1β; (3) palmitate-induced TXNIP expression is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in retinal endothelial cells. Population studies have shown that individuals with various components of the metabolic syndrome, including obesity, dyslipidaemia and hypertension, are more likely to have retinal microvascular abnormalities such as focal and generalised retinal arteriolar narrowing and venular dilatation [33, 34]. In our study, HFD-induced obesity or hypertension alone produced a significant increase in the formation of retinal acellular capillaries and this was further exacerbated upon their combination as early as 10 weeks. Accelerated retinal capillary dropout, vascular tortuosity and vascular leakage were previously reported in obese SHR rats starting at 12 weeks. [35].

The thioredoxin system is one of the major antioxidant and anti-apoptotic defence mechanisms, and is directly inhibited by TXNIP. Increased levels of TXNIP bind more thioredoxin, limiting its availability for scavenging cellular ROS [15]. Indeed, exposure of rats to HFD or hypertension, or their combination, significantly triggered retinal TXNIP expression, retinal lipid peroxides and NY levels, the footprint of PN formation, implicating endothelial dysfunction compared with controls (Figs 1, 2). Increased lipid peroxidation and PN generation and endothelial dysfunction were also reported in patients with hypertension-related microvascular changes [36, 37] and in retinas from BBZ rats, an obese and noninsulin-dependent model of diabetes [38], as well as coronary endothelial cells in response to HFD [39, 40]. Nevertheless, this is the first report to demonstrate increases in retinal TXNIP expression in HFD rats, SHR, or their combination. TXNIP can directly activate the redox-sensitive NFκB and its downstream inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules. HFD alone, hypertension alone or their combination significantly enhanced levels of NFκB and downstream TNF-α. In line with our findings, rats fed with an HFD or a high sucrose and cholesterol diet had a higher degree of inflammation in isolated retinal vasculature and higher levels of retinal microaneurysms, respectively [41, 42].

Lipotoxicity or impaired tissue homeostasis occurs as a result of lipid-induced changes in intracellular signalling or increased lipid use [9, 43]. Previous reports have established that saturated fatty acids, mainly palmitate but not unsaturated fatty acids, were able to induce pro-inflammatory responses in human coronary endothelial cells [7, 31] and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in cultured macrophages [6]. Accumulated literature provides evidence supporting TXNIP as an important mediator of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. However, the relationship between HFD-induced retinal and endothelial TXNIP expression and inflammasome activation in HFD-induced obesity has not been examined. Here we show that HFD alone selectively induced expression and interaction of TXNIP and NLRP3 resulting in cleaved caspase-1 and IL-1β expression independent of hypertension (Figs 3, 4). These results lend further support to previously documented TXNIP-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in lung endothelial cells, macrophages, adipose tissue and pancreatic beta cells in response to ROS, obesity/hyperglycaemia and endoplasmic reticulum stress [18, 32, 44, 45]. To model HFD in vitro, we examined the effects of the saturated fatty acid palmitate alone or in combination with exogenous PN in HRE cells. Indeed, silencing Txnip abrogated palmitate-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its associated increases in pro-apoptotic caspase-3 expression and reduced cell viability of HRE cells (Figs 6–8). These findings establish TXNIP as an essential activator of the NRLP3 inflammasome in HRE cells, a process which can result in increased retinal endothelial death/apoptosis. In line with our findings, pharmacological inhibition of caspase-1 or deletion of the IL-1 receptor suppressed the IL-1β-dependent formation of retinal acellular capillaries in diabetic animals [23, 46]. These findings support the proposed link between inflammasome activation and accelerated retinal microvascular degeneration. While the role of TXNIP expression was examined in retinal endothelial cells, the contribution of non-vascular retinal cell types is acknowledged and warrants further characterisation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of increased retinal TXNIP expression and activation of endothelial TXNIP–NLRP3 inflammasome in experimental models of HFD.

Our data suggest an inverse relationship between the accumulation of intracellular cleavage/maturation of IL-1β and its release. Pal-BSA alone was able to induce both intracellular maturation and release of IL-1β in HRE cells and this was mitigated by silencing Txnip (Fig. 7). On the other hand, exogenous PN alone resulted in a higher surge of IL-1β release, which was independent of TXNIP inhibition, although it was not able to induce significant changes in its intracellular cleavage/maturation, suggesting accelerated activation and trafficking of IL-1β. Furthermore, this effect was quenched when exogenous PN was combined with Pal-BSA in the presence of TXNIP, whereas TXNIP inhibition reversed this process and facilitated PN-induced IL-1β release despite its combination with Pal-BSA. This data indicate that, while TXNIP is required for palmitate-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β maturation in HRE cells, it does not facilitate the maximum IL-1β release. Recent evidence suggests that caspase-1 activation/processing of pro-IL-1β by caspase-1 and the release of mature IL-1β from human monocytes are distinct and separable events [47]. TXNIP has been shown to shuffle between different cellular compartments, including the nucleus, mitochondria [48] and plasma membrane [49]. A possible explanation for this intriguing observation might be due the nature of TXNIP as a member of the alpha arrestin scaffolding proteins, which are believed to play an important role in intracelleular cargo trafficking and/or internalisation of different proteins [49, 50]. Hence, subcellular localisation of TXNIP in response to different insults might reflect an enhancement or inhibition of mature IL-1β release.

In summary, our findings, in conjunction with the fact that obesity has been upgraded from a mere risk factor to a disease state, highlight the detrimental effect of HFD-induced obesity on the vasculature in general and development of retinal microvascular lesions even before reaching a state of hyperglycaemia and frank diabetes. Characterising the early impact of HFD-induced obesity on development of retinopathy and developing TXNIP as a therapeutic target will help to identify innovative strategies for intervention in obesity- and related vascular complications affecting millions of patients worldwide.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the technical expertise of S. Matragoon and B. A. Pillai (Program in Clinical and Experimental Therapeutics, University of Georgia, Augusta, GA, USA). A. B. El-Remessy and A. Ergul are research pharmacologists at the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center, Augusta, GA, USA.

Funding

This work was supported in part by grants from EY-022408, JDRF (4-2008-149) and Vision Discovery Institute to ABE, HL59699 to JDI, VA Merit Award BX00347 and NS054688 to AE and an American Heart Association pre-doctoral fellowship (12PRE10820002) for INM.

Abbreviations

- ARVO

Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology

- GCL

Ganglion cell layer

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- HFD

High-fat diet

- HRE

Human retinal endothelial

- INL

Inner nuclear layer

- IPL

Inner plexiform layer

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- NFκB

Nuclear factor κB

- NLRC4

NOD-like receptor CARD containing-4

- NLRP1

NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing-1

- NLRP3

NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing-3

- NY

Nitrotyrosine

- ONL

Outer nuclear layer

- Pal-BSA

Palmitate coupled to BSA

- PN

Peroxynitrite

- ROD

Relative optical densitometry

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SC

Scrambled

- SHR

Spontaneously hypertensive rats

- SHR+F

SHR fed HFD

- SiRNA

Small interfering RNA

- TXNIP

Thioredoxin-interacting protein

- W

Wistar control group rats

- W+F

Wistar control rats fed HFD

Footnotes

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

INM and ABE conceived the hypothesis, and wrote and edited the manuscript. INM, SSH, AF and ABE performed experiments and analyzed data to generate final figures, and edited the manuscript. AE and JDI helped with acquisition and interpretation of data and critically edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Nguyen TT, Wong TY. Retinal vascular manifestations of metabolic disorders. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liew G, Wang JJ. Retinal vascular signs in diabetes and hypertension--review. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2007;51:352–362. doi: 10.1590/s0004-27302007000200027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein R, Myers CE, Lee KE, Klein BE. 15-year cumulative incidence and associated risk factors for retinopathy in nondiabetic persons. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1568–1575. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Leiden HA, Dekker JM, Moll AC, et al. Risk factors for incident retinopathy in a diabetic and nondiabetic population: the Hoorn study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:245–251. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kratz M, Baars T, Guyenet S. The relationship between high-fat dairy consumption and obesity, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52:1–24. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wen H, Gris D, Lei Y, et al. Fatty acid-induced NLRP3-ASC inflammasome activation interferes with insulin signaling. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:408–415. doi: 10.1038/ni.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Staiger H, Staiger K, Stefan N, et al. Palmitate-induced interleukin-6 expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Diabetes. 2004;53:3209–3216. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boden G. Obesity, insulin resistance and free fatty acids. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2011;18:139–143. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283444b09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karpe F, Dickmann JR, Frayn KN. Fatty acids, obesity, and insulin resistance: time for a reevaluation. Diabetes. 2011;60:2441–2449. doi: 10.2337/db11-0425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pejnovic NN, Pantic JM, Jovanovic IP, et al. Galectin-3 deficiency accelerates high-fat diet-induced obesity and amplifies inflammation in adipose tissue and pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2013;62:1932–1944. doi: 10.2337/db12-0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuzaka T, Atsumi A, Matsumori R, et al. Elovl6 promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2012;56:2199–2208. doi: 10.1002/hep.25932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stienstra R, van Diepen JA, Tack CJ, et al. Inflammasome is a central player in the induction of obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15324–15329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100255108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vandanmagsar B, Youm YH, Ravussin A, et al. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2011;17:179–188. doi: 10.1038/nm.2279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroder K, Zhou R, Tschopp J. The NLRP3 inflammasome: a sensor for metabolic danger? Science. 2010;327:296–300. doi: 10.1126/science.1184003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nishiyama A, Matsui M, Iwata S, et al. Identification of thioredoxin-binding protein-2/vitamin D(3) up-regulated protein 1 as a negative regulator of thioredoxin function and expression. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21645–21650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parikh H, Carlsson E, Chutkow WA, et al. TXNIP regulates peripheral glucose metabolism in humans. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muoio DM. TXNIP links redox circuitry to glucose control. Cell Metab. 2007;5:412–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou R, Tardivel A, Thorens B, Choi I, Tschopp J. Thioredoxin-interacting protein links oxidative stress to inflammasome activation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:136–140. doi: 10.1038/ni.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perrone L, Devi TS, Hosoya K, Terasaki T, Singh LP. Thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) induces inflammation through chromatin modification in retinal capillary endothelial cells under diabetic conditions. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221:262–272. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Gayyar MM, Abdelsaid MA, Matragoon S, Pillai BA, El-Remessy AB. Thioredoxin interacting protein is a novel mediator of retinal inflammation and neurotoxicity. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:170–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devi TS, Lee I, Huttemann M, Kumar A, Nantwi KD, Singh LP. TXNIP links innate host defense mechanisms to oxidative stress and inflammation in retinal Müller glia under chronic hyperglycemia: implications for diabetic retinopathy. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:438238. doi: 10.1155/2012/438238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulze PC, Yoshioka J, Takahashi T, He Z, King GL, Lee RT. Hyperglycemia promotes oxidative stress through inhibition of thioredoxin function by thioredoxin-interacting protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:30369–30374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kowluru RA, Odenbach S. Role of interleukin-1beta in the development of retinopathy in rats: effect of antioxidants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:4161–4166. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Knight SF, Quigley JE, Yuan J, Roy SS, Elmarakby A, Imig JD. Endothelial dysfunction and the development of renal injury in spontaneously hypertensive rats fed a high-fat diet. Hypertension. 2008;51:352–359. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Prakash R, Chawla D, et al. Early effects of high-fat diet on neurovascular function and focal ischemic brain injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R1001–R1008. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00523.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Gayyar MM, Abdelsaid MA, Matragoon S, Pillai BA, El-Remessy AB. Neurovascular protective effect of FeTPPs in N-methyl-D-aspartate model: similarities to diabetes. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1187–1197. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdelsaid MA, Matragoon S, El-Remessy AB. Thioredoxin interacting protein (TXNIP) expression is required for VEGF-mediated angiogenic signal in endothelial cells. Antioxidant and Redox Signal. 2013 doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faustin B, Reed JC. Reconstituting the NLRP1 inflammasome in vitro. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;1040:137–152. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-523-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo X, Yang Y, Shen T, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid ameliorates palmitate-induced lipid accumulation and inflammation through repressing NLRC4 inflammasome activation in HepG2 cells. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012;9:34. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Knopp RH, Retzlaff B, Walden C, Fish B, Buck B, McCann B. One-year effects of increasingly fat-restricted, carbohydrate-enriched diets on lipoprotein levels in free-living subjects. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 2000;225:191–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1373.2000.22524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krogmann A, Staiger K, Haas C, et al. Inflammatory response of human coronary artery endothelial cells to saturated long-chain fatty acids. Microvasc Res. 2011;81:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiang M, Shi X, Li Y, et al. Hemorrhagic shock activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in lung endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:4809–4817. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong TY, Duncan BB, Golden SH, et al. Associations between the metabolic syndrome and retinal microvascular signs: the Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2949–2954. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kawasaki R, Tielsch JM, Wang JJ, et al. The metabolic syndrome and retinal microvascular signs in a Japanese population: the Funagata study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:161–166. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.127449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang SS, Khosrof SA, Koletsky RJ, Benetz BA, Ernsberger P. Characterization of retinal vascular abnormalities in lean and obese spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl. 1995;22:S129–S131. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferroni P, Basili S, Paoletti V, Davi G. Endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress in arterial hypertension. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;16:222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coban E, Nizam I, Topal C, Akar Y. The association of low-grade systemic inflammation with hypertensive retinopathy. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32:528–531. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2010.496519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellis EA, Grant MB, Murray FT, et al. Increased NADH oxidase activity in the retina of the BBZ/Wor diabetic rat. Free Radic Biol Med. 1998;24:111–120. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(97)00202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galili O, Versari D, Sattler KJ, et al. Early experimental obesity is associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H904–H911. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00628.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jebelovszki E, Kiraly C, Erdei N, et al. High-fat diet-induced obesity leads to increased NO sensitivity of rat coronary arterioles: role of soluble guanylate cyclase activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2558–H2564. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01198.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gustavsson C, Agardh CD, Zetterqvist AV, Nilsson J, Agardh E, Gomez MF. Vascular cellular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) expression in mice retinal vessels is affected by both hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Helfenstein T, Fonseca FA, Ihara SS, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance plus hyperlipidaemia induced by diet promotes retina microaneurysms in New Zealand rabbits. Int J Exp Pathol. 2011;92:40–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2010.00753.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Symons JD, Abel ED. Lipotoxicity contributes to endothelial dysfunction: a focus on the contribution from ceramide. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s11154-012-9235-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koenen TB, Stienstra R, van Tits LJ, et al. Hyperglycemia activates casp-1 and TXNIP-mediated IL-1beta transcription in human adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2011;60:517–524. doi: 10.2337/db10-0266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lerner AG, Upton JP, Praveen PV, et al. IRE1alpha induces thioredoxin-interacting protein to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and promote programmed cell death under irremediable ER stress. Cell Metab. 2012;16:250–264. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vincent JA, Mohr S. Inhibition of casp-1/interleukin-1beta signaling prevents degeneration of retinal capillaries in diabetes and galactosemia. Diabetes. 2007;56:224–230. doi: 10.2337/db06-0427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galliher-Beckley AJ, Lan LQ, Aono S, Wang L, Shi J. Casp-1 activation and mature interleukin-1beta release are uncoupled events in monocytes. World J Biol Chem. 2013;4:30–34. doi: 10.4331/wjbc.v4.i2.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lane T, Flam B, Lockey R, Kolliputi N. TXNIP shuttling: missing link between oxidative stress and inflammasome activation. Front Physiol. 2013;4:50. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Park SY, Shi X, Pang J, Yan C, Berk BC. Thioredoxin-interacting protein mediates sustained VEGFR2 signaling in endothelial cells required for angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:737–743. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu N, Zheng B, Shaywitz A, et al. AMPK-Dependent degradation of TXNIP upon energy stress leads to enhanced glucose uptake via GLUT1. Mol Cell. 2013;49:1167–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.