Abstract

Purpose

RECIST evaluation does not take into account the pre-treatment tumor kinetics and may provide incomplete information regarding experimental drug activity. Tumor Growth Rate (TGR) allows for a dynamic and quantitative assessment of the tumor kinetics. How TGR varies along the introduction of experimental therapeutics and is associated with outcome in phase I patients remains unknown.

Experimental designs

Medical records from all patients (n=253) prospectively treated in 20 phase I trials were analyzed. TGR was computed during the pre-treatment period (REFERENCE) and the EXPERIMENTAL period. Associations between TGR, standard prognostic scores (RMH score) and outcome (PFS, OS) were computed (multivariate analysis).

Results

We observed a reduction of TGR between the REFERENCE vs. EXPERIMENTAL periods (38% vs. 4.4%, P<.00001). Although most patients were classified as stable disease (65%) or progressive disease (25%) by RECIST at the first evaluation, 82% and 65% of them exhibited a decrease in TGR, respectively. In a multivariate analyses, only the decrease of TGR was associated with PFS (P=.004), whereas the RMH score was the only variable associated with OS (P=.0008). Only the investigated regimens delivered were associated with a decrease of TGR (P<.00001, multivariate analysis). Computing TGR profiles across different clinical trials reveals specific patterns of antitumor activity.

Conclusions

Exploring TGR in phase I patients is simple and provides clinically relevant information: (i) an early and subtle assessment of signs of antitumor activity; (ii) indpendent association with PFS; and (iii) It reveals drug-specific profiles; suggesting potential utility for guiding the further development of the investigational drugs.

Introduction

The introduction of the RECIST system (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors) represented a major improvement in the assessment of the tumor response to antineoplastic agents in the setting of clinical trials (1,2). Its criteria are based on the variation of the sum of the longest diameters of selected target lesions over time. However, the ability of RECIST to evaluate recent molecular targeted agents (MTA) is highly discussed since these drugs may induce tumor density or perfusion changes responsible of long lasting stabilizations rather than tumor shrinkage(3–6). This is especially relevant since the thresholds that dictate the decision-making for patients are somewhat arbitrary cut-offs on the continuous response scale: −30% for Partial Response (PR), +20% or occurrence of new lesions for Progressive Disease (PD), and between these two values for Stable Disease (SD). A number of alternative methods exploring tumor metabolism (5,7), tumor perfusion (8,9) or the immune component of the response (10) have been proposed to overcome these inadequacies. However, most of them require extra imaging exams (e.g. Positron Emision Tomography with 18-FDG, Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography) or did not reach the warranted level of evidence to be used in daily practice.

We and others have previously reported on the potential value of tumor kinetics in phase I trials to better evaluate tumor response (11–16). In a hypothetical trial testing an active drug, fast growing tumors at inclusion are more likely to be classified as stable disease or progression even if there is an antitumor activity (Supplementary Figure 1). This would lead to discard the patient from the trial and hamper the drug development. On the opposite, in a non-active drug configuration, patients enrolled with slow-growing tumors are likely to be classified as stable disease (Supplementary Figure 2) and lead to continue the unnecessary patient exposure to the drug. The analysis of Tumor Growth Rate (TGR) combines the RECIST sums of target lesions and the time between the tumor evaluations. It allows for a dynamic and quantitative evaluation of the tumor kinetics. Still, how the TGR varies along the introduction of experimental therapeutics and is associated with the outcome in phase I patients remains unknown.

Patients and Methods

Patients

The medical records of all consecutive patients (n=253) prospectively enrolled and treated in 20 phase I clinical trials at Gustave Roussy between July 2008 and June 2012 were analyzed. All the CT-scans were independently reviewed by two senior radiologists (CD and SA).

Definition of the Tumor Growth Rate (TGR)

Tumor size (D) was defined as the sum of the longest diameters of the target lesions as per the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria (1). Let t be the time expressed in months at the tumor evaluation. Assuming the tumor growth follows an exponential law, Vt the tumor volume at time t is equal to Vt=V0 exp(TG.t), where V0 is volume at baseline, and TG is the growth rate. We approximated the tumor volume (V) by V = 4 π R3 / 3, where R, the radius of the sphere is equal to D/2. Consecutively, TG is equal to TG=3 Log(Dt/D0)/t. To report the tumor growth rate (TGR) results in a clinically meaningful way, we expressed TGR as a percent increase in tumor volume during one month using the following transformation: TGR = 100 (exp(TG) −1), where exp(TG) represents the exponential of TG.

We calculated the TGR across clinically relevant treatment periods (Figure 1): (i) TGR REFRENCE assessed during the wash-out period (off-therapy) before the introduction of the experimental drug, (ii) TGR EXPERIMENTAL assessed during the first cycle of treatment (i.e.: between the drug introduction and the first evaluation, on-therapy). To compute the TGR REFERENCE, additional imaging exploring the wash-out period (off-therapy) immediately before the introduction were included when available. As per the RECIST system, patients with non-measurable disease only at baseline could not be assessed by TGR. For patients who progressed with new lesions, the TGR was computed on the target lesions only (new lesions not included in the RECIST sum).

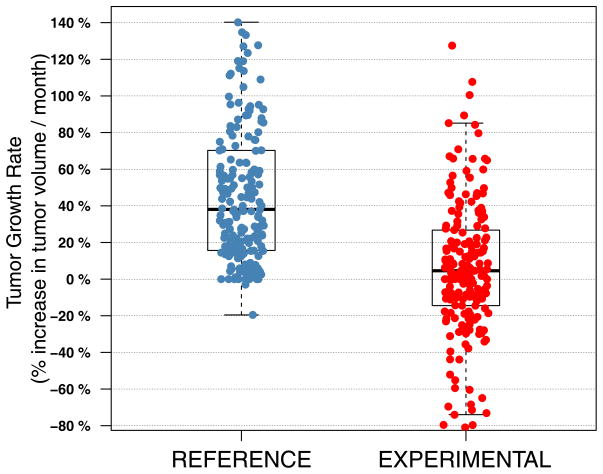

Figure 1.

Distribution of TGR across the REFENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL periods.

Statistical analysis

We performed pairwise comparisons to test the variations of TGR along the treatment sequences using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. Progression-free survival (PFS) was determined as the time between the date of randomization and the earliest sign of disease progression or death from any cause. Overall survival (OS) was determined as the time between the date of randomization and the death from any cause. The tumor progression was assessed using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (1,2) at the first treatment evaluation after the onset of the experimental drug. OS and PFS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between treatment groups using the log-rank test. To avoid the potential bias introduced by the fact that responders must live long enough for a response to be observed and for TGR to be measured, all associations between survival and TGR were performed using landmark method(16). As per the different protocols, all the patients had to be evaluated after 6 to 8 weeks of drug exposure. Consequently, we set the landmark point at 56 days. Hazard ratios (HR) were estimated from Cox proportional hazard models and were adjusted to the standard clinico-pathological prognostic factors, assessed by the Royal Marsden prognostic score (RMH), as previously described(17). All the tests were two-sided and significance was assumed if P<.05. All the analyses were carried out using the R statistical software (R version 2.15.0, http://www.R-project.org/.), the ‘survival’ R package (version 2.37.4, published by T. Therneau), and controlled by a senior statistician (S.K.).

Results

Description of the cohort

The calculation of TGR for both the REFERENCE and TGR EXPERIMENTAL periods could be computed in 201 out of 253 patients (79%): 47 patients did not have a tumor evaluation before the baseline, 3 patients exhibited a clinical tumor progression before the first tumor evaluation and 2 patients stopped because of toxicity before the first evaluation. Patient characteristics are described in the Table 1. The distribution of the patients according to the clinical trials (n=20) characteristics is described in Supplementary table 1.

Table 1.

Patients characteristics

| Patients N (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age | Mean (range) | 56 (20–77) |

|

| ||

| Gender | Males | 101 (50%) |

| Females | 100 (50%) | |

|

| ||

| Histological type | Thoracic | 35 (17%) |

|

| ||

| Colorectal | 33 (16%) | |

|

| ||

| Breast | 20 (10%) | |

|

| ||

| Mesothelioma | 17 (8%) | |

|

| ||

| Genitourinay (Renal, Bladder, prostate) | 14 (7%) | |

|

| ||

| Melanoma | 10 (5%) | |

|

| ||

| Non-colorectal GI (upper-GI, pancreas) | 17 (8%) | |

|

| ||

| head-and-neck cancer | 8 (4%) | |

|

| ||

| Sarcoma | 8 (4%) | |

|

| ||

| Gynecologic (ovarian, endometrial, cervix) | 10 (5%) | |

|

| ||

| other (thyroid, carcinoma of unknown origin, adrenocortical carcinoma, etc.) | 29 (14%) | |

|

| ||

| Previous lines of chemotherapy (N) | 0 | 21 (10%) |

| 1 | 22 (11%) | |

| 2 | 43 (21%) | |

| 3 | 48 (24%) | |

| 4–8 | 67 (33%) | |

|

| ||

| Number of metastatic sites (N) | 0–1 | 51 (25%) |

| 2 | 87 (43%) | |

| 3 | 52 (26%) | |

| > 4 | 11 (5%) | |

|

| ||

| Royal Marsden Hospital (RMH) prognostic score | 0 | 40 (21%) |

| 1 | 83 (44%) | |

| 2 | 51 (27%) | |

| 3 | 14 (7%) | |

Variation of TGR across the REFERENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL periods, according to the RECIST

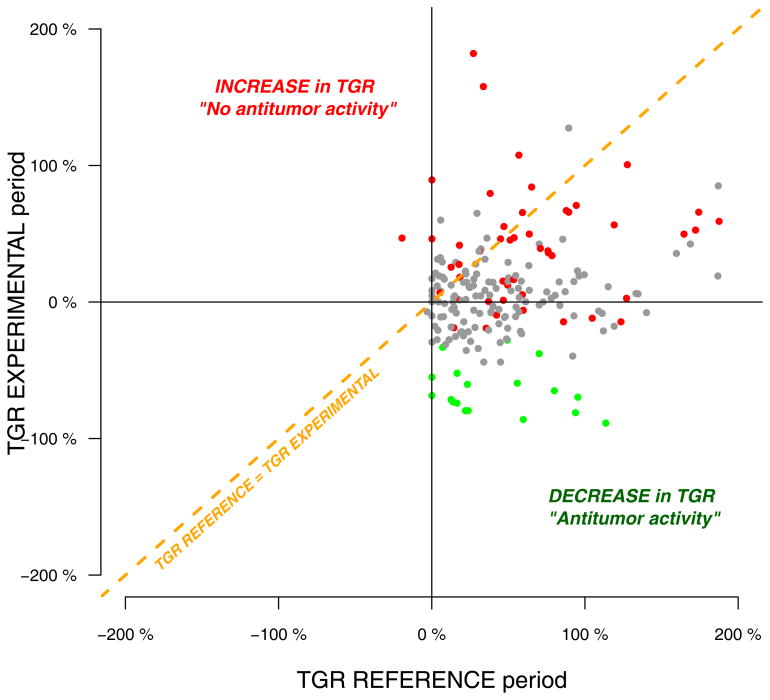

The distribution of TGR across the REFERENCE (median: 38; 95%CI: 0 – 140) and the EXPERIMENTAL periods (median: 4.4; 95%CI: 65 – 80) is described in Figure 1. At the first tumor evaluation, whatever the treatment delivered, most evaluable patients (131 patients, 65%) were classified as Stable Disease (SD) according to RECIST criteria (Figure 2, table 3), which is not very informative regarding for decision making and for evaluating the antitumor activity of a drug.. Meanwhile, 51 patients (26%) and 19 patients (9%) were classified as progressive disease (PD) and partial response (PR), respectively. Conversely, we observed that 82% and 65% of the patients initially classified as SD and PD exhibited a decrease in TGR, respectively. Overall, there was a significant decrease in the TGR between the REFERENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL periods in 159 patients (79%) (Pairwise comparison: Wilcoxon signed-rank test P<1e-05) (Figure 2, Supplementary table 2). Interestingly, we also observed that 20 out of the 28 patients (71%) progressing with new lesions at the first tumor evaluation experienced simultaneously a decrease of TGR, suggesting evidence of drug activity on the target lesions in this subset of patients as well. All together, these results suggest that TGR profiling is able to detect early anti-tumoral activity in patients receiving an experimental compound as early as in the first drug evaluation period.

Figure 2.

Pairwise comparisons of TGR between the REFERENCE and THE EXPERIMENTAL periods in 201 patients treated in 20 phase I clinical trials (P values are computed from wilcoxon pairwise tests, n represent the number of samples with pairwise TGR information). Red, grey and green colors indicate progressive disease, stable disease and partial response as per RECIST criteria, respectively.

Table 3.

distribution of the stage of development, the decrease of TGR and the tumor response (RECIST) across the different trials

| Investigational regimen | Decrease of TGR* | RECIST Evaluation | Total number of patients (N) | Current development status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive Disease (N) | Stable Disease (N) | Partial Response (N) | ||||

| Trial # 1: HSP inhib. | Not Significant | 3 | 5 | 0 | 8 | Stopped |

| Trial # 2: HSP inhib. | Not Significant | 10 | 11 | 0 | 21 | Ongoing |

| Trial # 3: Cell-Cycle inhib. | Not Significant | 3 | 9 | 0 | 12 | Stopped |

| Trial # 4: PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhib. | Not Significant | 2 | 7 | 0 | 9 | Ongoing |

| Trial # 5: Antiangiogenic | Not Significant | 3 | 4 | 1 | 8 | Ongoing |

| Trial # 6: HDAC inhib. | Not Significant | 9 | 11 | 0 | 20 | Ongoing |

| Trial # 7: PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhib. | Significant | 3 | 7 | 2 | 12 | Ongoing |

| Trial # 8: MEK inhib. | Significant | 3 | 8 | 2 | 13 | Stopped |

| Trial # 9: Antiangiogenic | Significant | 3 | 9 | 2 | 14 | Ongoing |

| Trial # 10: HER family inhibitor | Significant | 6 | 11 | 0 | 17 | Stopped |

| Trial # 11: Antiangiogenic | Significant | 3 | 15 | 2 | 20 | Ongoing |

| Trial # 12: PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhib. | Significant | 2 | 14 | 3 | 19 | Ongoing |

Significance of the decrease of TGR between the REFRENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL period (pairwise comparison, wilcoxon signed-rank test).

The decrease of TGR between the REFERENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL periods is associated with Progression-Free Survival (multivariate analysis)

We assessed whether the decrease of TGR between the REFRENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL was associated with outcome using the landmark method (Table 2). In a multivariate cox regression analysis (n=157), the decrease of TGR was significantly associated with progression free survival (PFS) (HR 0.91 95%CI: 0.85 0.96; P=0.004), but not with overall survival (OS) (HR 0.95 95%CI: 0.88 1.04; P=0.27). As such, every 10% decrease in the TGR between the REFRENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL periods results in a 9% decrease in the progression hazard of Progression. Conversely, the RMH prognostic score was nearly associated with PFS (HR 1.42 95% 0.96 2.08; P=0.08) and remained strongly associated with OS (HR 2.53 95% 1.47 4.34; P=0.0008). To note, the interaction tests between the decrease of TGR and RMH was not significant for PFS (P=.63) nor for OS (P=.15). Finally, when adding the tumor volume at baseline (V0, estimated by the RECIST sum) to the model combining the TGR and the RMH score, V0 appears to have no effect on survival (hazard ratios consistently very close to 1 and not significant p values) (data not shown). This confirms that the tumor burden at baseline (V0 estimated by the RECIST sum) has no or marginal effect on survival when TGR is incorporated in the model. All together, these results reveal that the decrease of TGR is strongly and independently associated with PFS but not with OS. On the opposite, when adjusting for a decrease in TGR, the RMH prognostic score remains the only independent variable associated with OS.

Table 2.

Multivariate cox regression analysis of the decrease of TGR and the RMH prognostic score for Progression-free survival (PFS) and Overall survival (OS).

| Progression-free survival (PFS) | Overall survival (OS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio 95% CI | P Value | Hazard ratio 95% CI | P Value | |

| Decrease of Tumor Growth Rate* | 0.91 0.85 – 0.96 |

0.004 | 0.95 0.88 – 1.04 |

0.27 |

| RMH prognostic score low score (0–1) vs. high score (2–3) | 1.42 0.96 – 2.08 |

0.08 | 2.53 1.47 – 4.34 |

0.0008 |

All the analyses reported are performed with the landmark method (landmark point was set to 56 days, n=157 patients analyzed).

To be clinically meaningfull, hazard ratios are computed for 10% variation in Tumor Growth Rate. Here, every 10% decrease in TGR between the REFRENCE and the EXPERIMENTAL periods results in a 9% decrease in the progression hazard.

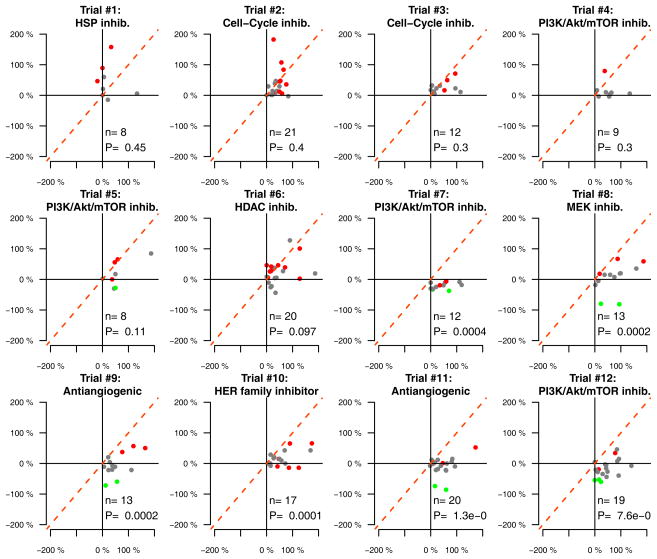

TGR profiling across investigational regimens reveals specific patterns of antitumor activity

Since the decrease of TGR was independently associated with PFS but not with OS, we assumed that the decrease of TGR might be influenced by the investigational regimen. To investigate this hypothesis, we computed a multivariate linear model incorporating the investigational regimen, the RMH prognostic score, the age, the gender and the number of previous lines of treatment. We empirically restricted our analysis on the trials with a minimum of 8 patients enrolled per trial (12 / 20 trials). Importantly, only the investigational regimen was associated with the decrease of TGR (P<.00001), accounting for 31% of the explained variance (R2) (Supplementary table 3, Figure 3). The TGR analysis (REFERENCE vs. EXPERIMENTAL periods) across the different clinical trials clearly shows specific patterns of anti-tumor activity (Figure 3). Interestingly, we observed that some regimens without objective tumor response by RECIST (e.g. Trial #10: HER family inhibitor) but exhibiting a significant decrease of TGR are now stopped in development(Table 3).

Figure 3.

TGR profiling reveals specific patterns of antitumor activity across twelve phase 1 clinical trials (P values are computed from wilcoxon pairwise tests; n represent the number of samples with pairwise TGR information; only clinical trials with more than 7 patients were analyzed). Red, grey and green colors indicate progressive disease, stable disease and partial response as per RECIST criteria, respectively.

Discussion

Within this study, TGR demonstrates a strong potential for translation in the early drug development setting in several ways: (i) TGR allows for an earlier and more precise detection of signs of antitumor activity as compared to the RECIST criteria, (ii) it is independently associated with progression-free survival in a prospective cohort of phase I patients, (iii) the TGR profiles reveal clear antitumor activity patterns specific to the investigated regimens.

Interestingly, neither the RECIST criteria were developed in the specific early drug development context nor the aim of phase I trials are primarily to evaluate the antitumor efficacy. However, it is notable and logical that the studies exhibiting objective tumor response (as per RECIST) receive more attention from the oncology community and are thus more prone to be further developed. The present study clearly confirms that early signs of antitumor activity (i.e. as soon as at the first planned tumor evaluation) are not well estimated using the conventional RECIST criteria in phase I patients since most of the patients (65%) are classified as stable disease, which is not very informative for assessing a drug efficacy. Furthermore, our study reveals that most of the patients (79%) exhibit signs of antitumor activity, confirming the risk of discarding, at wrong, potentially responder patients and ultimately, potential active drugs.

It is expected that greater tumor shrinkage is correlated with outcome, though this link remains highly debated across tumor types (18–21). Other authors have recently described a correlation between change in tumor response by RECIST- taken as a continuous variable - with overall survival in the context of phase I trials (22). However, such results were not adjusted for the standard prognostic score (RMH), which has been shown to be highly prognostic for overall survival (17). While this study confirmed that the RMH score the only variable associated with overall survival, the decrease of TGR was the only independent variable associated with progression-free survival. Additionally, we showed that the investigated regimen is the only variable associated with the decrease of TGR. These results underscore the importance of TGR profiles as a tool for evaluating the antitumor activity of the investigational regimens in phase I trials and for guiding the “Go / No Go” decision in the early drug development setting. Such findings are nevertheless limited by the retrospective nature of our analyses and warrant further validation.

The Tumor Growth Rate assessment is feasible for most patients (79% patients enrolled) and requires minor additional costs, mainly imputable to the retrieval and analysis of the pre-treatment imaging. Moreover, TGR are simple to compute at bedside: web and smartphone applications even exist (e.g. CancerPal©). We are releasing within this article a free TGR calculator web tool (http://www.gustaveroussy.fr/doc/tgr_calculator/index_en.html) to help oncologists and clinical researchers to ease its assessment. These practical considerations reinforce our belief that translating the TGR into the clinical research could substantially impact the decision making process in phase I trials, by providing an earlier and precise evaluation of the drug activity of patients and by improving the evaluation of investigational new drugs.

Supplementary Material

Statement of translational relevance.

In addition to explore the safety profiles of the investigated regimens, phase I trials play a major role in the drug development by revealing the early signs of antitumor activity of the drugs. We evaluated the variation of the tumor growth kinetics (assessed by Tumor Growth Rate or TGR) across the REFERENCE (wash-out period before treatment) and the EXPERIMENTAL periods in 201 patients prospectively treated in 20 phase I trials. Although most of the patients were classified as stable disease (65%) or progressive disease (25%) by RECIST at the first tumor evaluation, 82% and 65% of them exhibited a decrease of TGR, respectively. The decrease of TGR was the only independent variable associated with PFS (multivariate analysis) and was only influenced by the prescribed investigational regimen (multivariate analysis). Such findings suggest the usefulness of TGR profiling to guide the “go / no go” decision making in early drug development.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: During this project, Charles Ferté was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (U54CA149237).

Footnotes

Potential disclosure of interest: the authors declare no conflict of interest for this work.

This study has been previously presented during the 2013 ASCO Annual Meeting at the Poster Discussion Session, Developmental therapeutics. Charles Ferté received an ASCO Merit Award for this work.

References

- 1.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, et al. New Guidelines to Evaluate the Response to Treatment. 2000:92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenhauer E, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer Elsevier Ltd. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maitland ML, Bies RR, Barrett JS. A time to keep and a time to cast away categories of tumor response. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3109–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crabb SJ, Patsios D, Sauerbrei E, Ellis PM, Arnold A, Goss G, et al. Tumor cavitation: impact on objective response evaluation in trials of angiogenesis inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin RS, Choi H, Macapinlac Ha, Burgess Ma, Patel SR, Chen LL, et al. We should desist using RECIST, at least in GIST. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1760–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy A, Hollebecque A, Ferté C, Koscielny S, Fernandez M, Soria J-C, et al. Tumor assessment criteria in phase I trials: beyond RECIST. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahl RL, Jacene H, Kasamon Y, Lodge Ma. From RECIST to PERCIST: Evolving Considerations for PET response criteria in solid tumors. J Nucl Med. 2009;50(Suppl 1):122S–50S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frampas E, Lassau N, Zappa M, Vullierme M-P, Koscielny S, Vilgrain V. Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: early evaluation of response to targeted therapy and prognostic value of Perfusion CT and Dynamic Contrast Enhanced-Ultrasound. Preliminary results. Eur J Radiol. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lassau N, Chami L, Benatsou B, Peronneau P, Roche A. Dynamic contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (DCE-US) with quantification of tumor perfusion: a new diagnostic tool to evaluate the early effects of antiangiogenic treatment. Eur Radiol Suppl. 2008;17:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s10406-007-0233-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, Weber JS, Hamid O, Lebbé C, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7412–20. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gomez-Roca C, Koscielny S, Ribrag V, Dromain C, Marzouk I, Bidault F, et al. Tumour growth rates and RECIST criteria in early drug development. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2512–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Le Tourneau C, Servois V, Diéras V, Ollivier L, Tresca P, Paoletti X. Tumour growth kinetics assessment: added value to RECIST in cancer patients treated with molecularly targeted agents. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:854–7. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferté C, Koscielny S, Albiges L, Rocher L, Soria J-C, Iacovelli R, et al. Tumor Growth Rate Provides Useful Information to Evaluate Sorafenib and Everolimus Treatment in Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Patients: An Integrated Analysis of the TARGET and RECORD Phase 3 Trial Data. Eur Urol. 2013:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2013.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neal ML, Trister AD, Ahn S, Baldock A, Bridge CA, Guyman L, Lange J, Sodt R, Cloke T, Lai A, Cloughesy TF, Mrugala MM, Rockhill JK, Rockne RC, Swanson KR. Response classification based on a minimal model of glioblastoma growth is prognostic for clinical outcomes and distinguishes progression from pseudoprogression. Cancer Res. 2013 May 15;73(10):2976–86. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stein WD, Wilkerson J, Kim ST, Huang X, Motzer RJ, Fojo AT, et al. Analyzing the pivotal trial that compared sunitinib and IFN-α in renal cell carcinoma, using a method that assesses tumor regression and growth. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2374–81. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein WD, Yang J, Bates SE, Fojo T. Bevacizumab reduces the growth rate constants of renal carcinomas: a novel algorithm suggests early discontinuation of bevacizumab resulted in a lack of survival advantage. Oncologist. 2008;13:1055–62. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2008-0016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson JR, Cain KC, Gelber RD. Analysis of survival by tumor response. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1:710–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.11.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arkenau H-T, Barriuso J, Olmos D, Ang JE, de Bono J, Judson I, et al. Prospective validation of a prognostic score to improve patient selection for oncology phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2692–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buyse M, Thirion P, Carlson RW, Burzykowski T, Molenberghs G, Piedbois P. Relation between tumour response to first-line chemotherapy and survival in advanced colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2000;356:373–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkerson J, Fojo T. Progression-free survival is simply a measure of a drug’s effect while administered and is not a surrogate for overall survival. Cancer J. 2009;15:379–85. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181bef8cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oye RK, Shapiro MF. Reporting results from chem- otherapy trials. Does response make a difference in patient survival? JAMA. 1984;252:2722–2725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pazdur R. Response rates, survival, and chemotherapy trials. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1552–3. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.19.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain RK, Lee JJ, Ng C, Hong D, Gong J, Naing A, et al. Change in tumor size by RECIST correlates linearly with overall survival in phase I oncology studies. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2684–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.