Abstract

Gene therapy is a promising strategy to treat various genetic and acquired diseases. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) is a revolutionary tool for gene therapy and the analysis of gene function. However, the development of a safe, efficient, and targetable non-viral siRNA delivery system remains a major challenge in gene therapy. An ideal delivery system should be able to encapsulate and protect the siRNA cargo from serum proteins, exhibit target tissue and cell specificity, penetrate the cell membrane, and release its cargo in the desired intracellular compartment. Nanomedicine has the potential to deal with these challenges faced by siRNA delivery. The unique characteristics of rigid nanoparticles mostly inorganic nanoparticles and allotropes of carbon nanomaterials, including high surface area, facile surface modification, controllable size, and excellent magnetic/optical/electrical properties, make them promising candidates for targeted siRNA delivery. In this review, recent progresses on rigid nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery systems will be summarized.

Keywords: Gene therapy, RNA interference (RNAi), small-interfering RNA (siRNA), Gene delivery, Nanoparticles

1 Introduction

RNA interference (RNAi) is highly effective in knocking down the target post-transcriptional mRNA sequence that regulates the specific biological/pathological pathway at the translation level (Fire et al., 1998). The discovery of RNAi methodology begins a new epoch in the development of gene therapeutics for the treatment of various genetic and acquired diseases that are incurable by conventional drugs. Small-interfering RNA (siRNA), a class of double-stranded RNA molecules consisting of 20–25 base pairs, is most notable in the RNAi pathway (Elbashir et al., 2001) where it interferes with the expression of specific genes. The synthesis of these functional macromolecules is straightforward, which facilitates the translational research with clinical promise (Sah, 2006). However, the naked siRNA can activate the immune system and is susceptible to enzyme degradation, thus not able to survive in biological fluids for a long time (de Fougerolles et al., 2007, Oh and Park, 2009). Moreover, the high anionic charge and high molecular weight (~15 KDa) restrict the naked siRNA with limited penetration of the cell membrane. Although virus-based siRNA delivery strategies are highly effective, the biosafety concerns, such as endogenous virus recombination and immunogenicity response, remain an issue (Edelstein et al., 2007, Woods et al., 2006).

To date, much effort has been made to overcome the challenges related to the delivery, stability, off-target gene silencing and immunostimulatory effects of siRNA. In the past decade, nanovehicles gained wide attention in biomedical applications, especially in drug/gene delivery, because they can avoid virus-based deleterious responses and also possess highly tunable surface properties, size, shape and composition. A variety of carriers made of lipids, polymers, carbohydrates and inorganic nanomaterials have been developed for siRNA delivery. Among them, the polymer or lipid-based vehicles have shown successful improvements in delivering therapeutic genes because of their special advantages including possibility of high experimental repeatability, facile manufacturing, the ease of functional modification and no oncogenesis (Park et al., 2006). However, complicated chemical synthetic procedures and some harsh chemical reaction conditions limit their applications. Rigid nanomaterials, such as gold, calcium phosphate, quantum dots, iron oxide and allotropes of carbon nanomaterials, have monumental value arising from their unique material- and size-dependent physical properties, such as optical, electrical and magnetic (Bhattacharyya et al., 2011). These functionalities are far beyond the traditional organic molecules, polymers, and besides, the nanocomposites combining biocompatible organic materials and inorganic nanoparticles are endowed with highly ordered biofunction and biocompatibility. The resulting nanocomposites based delivery systems are expected to play a significant role in the dawning era of gene therapy, with hope to overcome the barriers which hinder the RNAi therapy.

The push provided by advances in nanotechnology has already made siRNA delivery systems a research hotspot. Recently, numerous rigid nanomaterials have been widely investigated for siRNA delivery. However, rigid nanoparticle-based gene therapy platforms are struggling to advance into clinical trials and most of which are still in their early stages of development (Cheng et al., 2012). This review attempts to give a summary of the challenges faced by siRNA nanocarriers for cancer therapy and highlight the recent advances in rigid nanoparticle-based siRNA nanocarriers, arranged by the category of their core nanomaterial, that hold potential for clinical translation.

2 The challenges faced by nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery

2.1 In the systemic circulation

Systemic targeted delivery aided with blood circulation is a very promising technology for nanoparticle-based siRNA therapy. However, a number of factors would have fundamental impact on the transport of nanoparticles in systemic use, which influence the extent and duration of siRNA function, such as targeting efficiency, immune response, stability of vehicle, and so on. Unlike other kinds of chemotherapy drug (e.g. doxorubicin and paclitaxel), which can be formulated with nanoparticles via bioconjugation techniques, the siRNA loading onto nanoparticles is mostly achieved via physical means, such as electrostatic interaction. Thus, a number of siRNA molecules are lost during the journey to the tumor site due to the carrier’s disorientation (Luo and Saltzman, 2000). Understanding the bio-behavior of these nanovehicles in the systemic circulation is essential for the development of safe and efficient siRNA delivery systems (Stark, 2011).

2.1.1 Innate immune response and system clearance

Naked siRNA is unstable and has a half-life of less than 5 min in blood due to the degradation by enzymes in serum and capture of tissues/organs (Layzer et al., 2004). The free extrinsic nucleotide is easily recognized by scavenger receptors, leading to non-parenchymal cell internalization (i.e., the kupffer cells in liver). Furthermore, the naked siRNA has the potential to trigger immune response. Nanoparticle formulation has the potential to protect siRNA from the degradation and prevent interactions with immune receptors, through encapsulating or combining nucleotide molecules inside the nanocarries or on their surface and neutralizing the polyanionic nature of nucleotide (Hashida et al., 1996, Pouton and Seymour, 2001).

However, the nanocarriers themselves are usually recognized as harmful agents and then are cleared from systemic circulation. Generally, size and surface characteristics of nanoparticles are related to the rate of clearance from the body (Moghimi et al., 2001). Nanoparticles in the range of 50–150 nm often have relatively slow clearance (Moghimi et al., 2001), but the nanoparticles with size smaller than 10 nm can be rapidly leaked into blood capillaries or removed via kidney excretion (Malam et al., 2009). Besides the influence of size, the surface characteristics of nanoparticles also directly affect their fate in vivo. Not only the positively charged nanocarriers but also the negatively charged delivery systems can bind with opsonins such as immunoglobulin, complement proteins, and so on (Li and Szoka, 2007). The opsonized nanoparticles lead to the activation of a cascade of signaling pathways and then are actively phagocytosed in the reticuloendothelial system (RES), which can cause liver injury and splenomegaly (Scherphof and Kamps, 2001). Thus, understanding the mechanism of immunogenicity and toxicological response is important for developing rigid nanoparticle-based siRNA nanocarriers.

It is well known that blood circulation and extravasations directly affect the accumulation of nanoparticles in the destined site. Extending systemic circulation time can increase the probability of nanoparticles to reach the target place. Hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) is often applied to modify the surface of nanoparticles to shield the undesirable surface charge, prevent triggering the RES response and slow down the clearance from blood (Seth et al., 2012). The molecular weight and density of PEG play crucial roles in regulating the pharmacokinetics. For example, the circulation half-life of small PEG with molecular weight of 6,000 is less than 20 min, while it is extended to a day with the PEG of 190,000 (Yamaoka et al., 1994). In another example, the PEGylated liposome-protamine-DNA nanoparticles with sufficient PEG density (10%) in a brush configuration can decrease liver retention (12% input dose at 4 h) and obtain an increased accumulation in the tumor tissue (>30% input dose at 4 h) (Li and Huang, 2009, 2010). However, it is of note that the PEGylated nanoparticles can also induce production of specific anti-PEG IgMs and thus speed up the blood clearance of particles (Ishida et al., 2006). Meanwhile, these hydrophilic materials may also impact the stability of nanoparticles formed by amphiphilic materials via the hydrophobic assembly, especially by reducing the critical micelle concentration (CMC) (Collnot et al., 2006).

2.1.2 Biomolecular corona

The characteristics of rigid nanoparticle including the chemical composition, shape, size, zeta potential, hydrophobicity or hydrophilicity, are key parameters for the biological outcomes. It is well acknowledged that the biological system would initiate stress reaction with the foreign agents and lead to a dynamic physicochemical interaction of kinetics and thermodynamic exchanges between nanocarriers and the biological components (Hellstrand et al., 2009). A common phenomenon was found that lipids and proteins would form a shield corona on the pristine surface of the nanomaterial (Nel et al., 2009). It was reported that amphiphilic poly(maleic anhydride alt-1-tetradecene)-coated FePt and CdSe/ZnS nanoparticles could take up human serum albumin (HSA) to form a 3.3-nm-thick monolayer of corona in less than 2 min (Rocker et al., 2009). Additionally, the components of the corona are under a dynamic exchange based on the different surface bonding energy (Hellstrand et al., 2009). For example, as a result of HSA’s low affinity to N-isopropylacrylamide-co-N-tert-butylacrylamide copolymer nanoparticles, the HSA corona could be rapidly replaced by the higher affinity and slower exchanging apolipoproteins (Cedervall et al., 2007). It is possible that amphiphatic α-helices in apolipoprotein make the protein flexible to bind nanoparticles (Cedervall et al., 2007, Frank and Marcel, 2000).

Nanoparticles modified with targeting ligands have large attractive force to bind with the specific cells for targeted anti-cancer gene therapy (Lynch et al., 2009). However, the receptor-ligand reaction will be definitely affected by the shielding of corona, especially when foreign proteins reside on the surface of nanoparticles for long time (Salvati et al., 2013). The coronas formed with a specific composition to different nanoparticles are very important for cell-nanoparticle interactions (Lynch et al., 2009). As known, it is a two-step process for nanoparticle uptake, wherein the nanoparticles initially adhere to the cell membrane and then are internalized via the energy-dependent process. In such an active process, the contact between nanoparticles and cells is mediated by protein corona (Walczyk et al., 2010, Watson et al., 2005). It would strongly reduce the nonspecific interactions between the nanoparticles and cells if the protein corona does not have receptor-binding sequence.

The shield corona coating on the nanocarriers can also influence the body’s immune defense system in the blood before reaching the target. For example, a very important aspect of protein adsorption onto nanoparticles surfaces is that structural changes of the protein may occur, leading to the exposure of new peptide epitopes. The exposure of new antigenic sites may elicit an immune response, which could promote autoimmune diseases. In a word, the protein corona affects the structure and function of the protein itself as well as the cellular uptake of the nanocarriers. Thus, understanding the formation and consequences of the protein corona is of great importance for the elucidation and assessment of the RNAi effects of nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery systems.

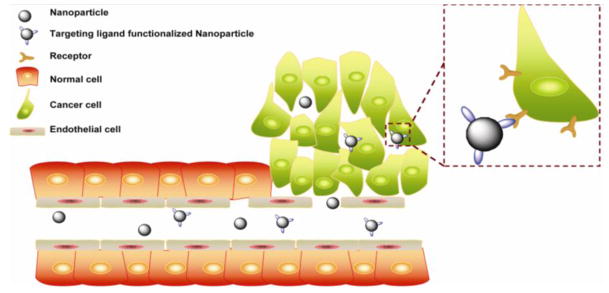

2.1.3 Passive targeting and active targeting based gene delivery

There are two strategies in cancer targeted gene delivery: “passive targeting” and “active targeting” (Figure 1). Matsumura and Maeda proposed the principle of enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect of delivery systems, which leads to tumor accumulation of nanoparticles through the leaky vasculature (Matsumura and Maeda, 1986). Subsequently, this principle is regarded as the main mechanism of passive targeting strategy. The fast-growing tumors have numerous endothelial pores in tumor vessels with size varying from 10 to 1000 nm that make tumor vessels highly permeable (Carmeliet and Jain, 2000, Torchilin, 2000). Thus, the pathological characteristics enable nanocarriers to retain in tumor tissue (Cho et al., 2008, Maeda, 2001). Systemic circulation and suitable nanoparticle size are significant factors that affect the tumor accumulation kinetics of nanocarriers. Nevertheless, the microenvironment in the tumor also impacts the EPR effect, for example the pressure gradient.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the EPR effect and “active targeting process”. Blood flow is the essential driving force for nanocarrier delivery.

The difference of pressure makes the convective fluid flow, which takes nanocarriers from the distant place to targeted side. However, most solid tumors exhibit higher interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) than the normal tissue (Milosevic et al., 2004). The increased IFP at the center of solid tumors hinders trans-capillary transport and affects the diffusion of gene-nanocarrier (Danhier et al., 2010, Heldin et al., 2004). It was reported that bound antibody against human epithelial cell adhesion molecule highly expressed in a variety of clinical tumors was only detected close to the perfused blood vessels due to the higher IFP at the center of tumor (Heine et al., 2012). In addition, the passive targeting delivery is mainly dependent on the degree of tumor vascularization. However, angiogenesis is usually formed under a state of cellular hypoxia (Bergers and Benjamin, 2003). At the early stage, oxygen and nutrients can easily diffuse into the center of tumor; accordingly, the tumor is poorly vascularized and difficult to evoke EPR that make the treatment complicated. In other cases, some types of cancers (e.g. gastric and pancreatic cancer) don’t have evidence of EPR effect (Kano et al., 2007). Therefore, it is still a very intricate problem to evaluate the effectiveness of EPR mechanism. As discussed above, further understanding about passive targeting gene delivery is requested. Recently, active targeting gene delivery systems become increasingly prominent and valuable in an effort to determine the biological outcome via conjugation with biofunctional moieties.

Active targeted gene delivery usually means specific ligand-receptor mediated interactions between nanocarriers and cancer cells (Table 1). It seems that the modified ligand on nanocarriers only enhances the possibility of affinity binding to the receptor and then increases cellular uptake, instead of tumor localization. For example, Nie et al. utilized three different ligands (single-chain variable fragment (ScFv) peptide, amino terminal fragment (ATF) peptide and cyclic arginine-glycine-aspartic (cRGD) peptide conjugated colloidal gold nanorods to explore the targeted delivery mechanisms in A549 xenograft model (Huang et al., 2010). Through quantitative pharmacokinetic and biodistribution analysis, it was found that the targeting ligands improved intracellular uptake of the nanosystem. The non-targeted vehicles were trapped in the tumor stromal matrix, around blood vessels or inside some macrophage cells, while the targeted vehicles were localized in the tumor cells (Huang et al., 2010). Subsequently, the circulation half-life of the receptor targeted nanorods was shortened and the accumulation at the tumor site was not significantly improved in comparison with the non-targeted control ones. Similar results have also been reported in some functional ligands or monoclonal antibody modified immunoliposomes (van Rooy et al., 2011). It is still a challenge to select or design the appropriate ligand/antibody. The optimal ligand/antibody is required to be easily incorporated into rigid nanoparticles, has a high affinity for cancer cell surface receptors, and has the ability to efficiently cause internalization of the siRNA.

Table 1.

Common ligands and biomarkers for cancer targeted delivery.

| Trageting ligands and antibodies | Target biomarker | Expression in human cancer tissues (% of primary carcinoma that high express biomarker) | Exemplary high level biomarker expression cell lines | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Folate | Folate receptor | Solid tumor: ovarian cancer (100%), renal cancer (86%), breast cancer (43%), lung cancer (36%), brain cancer (25%), pancreatic cancer (10%) | A2780, KB, SKOV-3, OVCAR-3, L1210, M109, HeLa. | (Ke et al., 2005, Nukolova et al., 2011, Parker et al., 2005, Saul et al., 2006, Werner et al., 2011, Zhang et al., 2010a) |

| RGD, cRGD, iRGD | Integrin | Tumor endothelial cells: ovarian cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, glioblastoma, cervical cancer. | U87MG, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-468, MDPC-23, HUVEC. | (Cai et al., 2010, Desgrosellier and Cheresh, 2010, Hill et al., 2007, Liu et al., 2009a, Liu et al., 2009b, Sugahara et al., 2010, Valencia et al., 2011) |

| Anti-EGFR, Necitumumab, GE11 peptide | EGFR | Solid tumor: head and neck (80–100%), breast cancer (14–91%), colorectal cancer (25–80%), non-small-cell lung cancer (40–80%), glioma (40–80%), ovarian cancer (35–70%), bladder cancer (31–72%). | MDA-MB-231, A431, HCT-116, DU-145, HuH7, 32D. | (Chan et al., 2013, Gao et al., 2011a, Herbst and Shin, 2002, Kuenen et al., 2010, Mickler et al., 2012, Nair, 2005, Rehder et al., 2008, Yip et al., 2007) |

| Trastuzumab, Herceptin, anti-HER2 | HER2 | Solid tumor: colorectal cancer (26–90%), glioma (20–54%), gastric (38–45%), non-small-cell lung cancer (18–37%), breast cancer (25–30%), bladder cancer (9–36%), ovarian cancer (10–15%). | SKBR3, MGC803, SKOV3, BT-474. | (Crow et al., 2005, Gao et al., 2011b, Miyano et al., 2010, Nair, 2005, Ruan et al., 2012, Stefanick et al., 2013) |

| Transferrin | Transferrin receptor | Solid tumor: kidney cancer, ovarian cancer, colon cancer, breast cancer, stomach cancer, lung cancer. | A2780, OVCAR-3, HEY, U251, HepG2 | (Calzolari et al., 2007, Gatter et al., 1983) |

| Anti-VEGF, Bevacizumab | VEGF | Tumor endothelial cells: vasculature endothelial cells | HUVEC, HepG2, PC-3 | (Ferrara et al., 2005, Kim et al., 2006, Liu et al., 2011c, Stefanou et al., 2004, Willis et al., 1998) |

Ideally, the efficient ligand-receptor interaction needs the corporation of a variety of factors: 1) pathological cell surface antigens/receptors are selectively over-expressed relative to those of healthy cells; 2) receptors are required to be homogeneously and availably distributed on the cell surface; 3) high ligand-mediated specific binding. Furthermore, the density of the target receptor is also a key factor. It was reported that radiolabeled dimeric RGD peptide showed a 10-fold higher affinity than the monomer analogue in vitro and exhibited significantly higher target accumulation at 4 h post injection in the OVCAR-3 ovarian carcinoma xenograft model (Janssen et al., 2002). However, nanostructure system is different from the simple macromolecular targeting delivery system. In one example, iron oxide nanoparticles modified with HER2/neu targeting affibodies didn’t show linear relationship between ligand density and targeting effect. The nanoparticles with 23 ligands/SPIO exhibited higher cell targeting efficiency compared than those with lower density (11.5 ligands/SPIO) and higher density (35.8 ligands/SPIO) in T6-17 cells in vitro (Elias et al., 2013). Theoretically, different ligand densities induce different physical and biological properties such as different surface energy, leading to different therapeutic outcomes. Moreover, tumor, as a biological system, can actively regulate the expression of specific biomarkers to against the nanoparticles coated with antibodies, and in turn, the nanoparticles also play an active role in mediating biologic effects (Jiang et al., 2008).

A typical experiment to test the nanocarrier targeting effectiveness is using cultured cells in vitro that express a unique surface biomarker (Liu et al., 2012). Although some nanocarriers exhibit efficient siRNA silencing effect in vitro, the interaction between nanocarriers and cells may be driven by the physical proximity (e.g. precipitation) but not the ligand-reporter mediated force, and then in vitro experiments are hard to simulate the nanocarrier transport process (Bae and Park, 2011, Kwon et al., 2012). Similarly, static 3D cell culture models are also hard to simulate the nanocarrier transport process without fluid condition. Traditionally, xenograft models are widely used to evaluate nanocarriers and explore basic pathophysiological mechanisms. However, it is noticeable that the xenografts only maintain some but not all biological properties of human tumors. Human tumors are often much more complex than the tumor xenografts in mice (Seok et al., 2013). These intrinsic drawbacks hinder the development of targeting nanocarriers.

2.1.4 Evaluation of gene delivery efficiency

In addition to the issues above, the effectiveness and safety of siRNA delivery are often hampered by the lack of exact method to monitor the fate of siRNA and/or nanocarriers in vivo. Conventional therapeutic outcome based evaluation, such as tumor size measurement and histology, would miss a lot of valuable information. However, the emergence of molecular imaging techniques has been pivotal in optimizing siRNA delivery and estimating therapeutic efficacy. Advanced molecular imaging techniques enable real-time assessment of the therapeutic process and non-invasive visualization of molecular pathways in vivo (Knipe et al., 2013).

In order to facilitate effective tracking of siRNA delivery by imaging methods, the siRNA and/or nanocarriers would be pre-labeled with imaging probes. Visualizing siRNA and/or nanocarriers are usually achieved by direct labeling with fluorophores or radioisotopes. Due to the unique properties, some inorganic nanoparticles (e.g., magnetic nanoparticles, gold nanoparticles, and quantum dots) are confirmed as effective gene vectors and capable of tracking the delivery process. Integrating genetic components with molecular imaging probes into a single formulation facilitates investigation of the basic pharmacokinetics and diffusion of nanocarriers. Even though some images report the biodistribution of nanocarriers and reflect therapeutic effect noninvasively, some notable questions remain. Imaging probes may not always faithfully represent the intact siRNA and/or nanocarriers they attach to. Indistinguishable label signals may come from intact siRNA and detach free probes. In addition, signals from probes may be absorbed or scattered inside deep tissues/cells, rendering quantification unreliable.

Several imaging modalities have been widely used in the clinic, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and X-ray computed tomography (CT). However, each type of imaging modality has its own pros and cons. For instance, MRI has high spatial resolution (25–100 μm) and deep tissue penetration without radiation, nevertheless, its sensitivity is several orders of magnitude lower than PET and optical imaging (Massoud and Gambhir, 2003). There has been a trend to combine different imaging components together to form multi-modality imaging agents which utilize the advantages of each modality and offset respective weaknesses (Massoud and Gambhir, 2003). The multifunctional agents provide registered images that improve the ability to quantify and interpret biological processes as well as the development of targeted siRNA delivery.

2.2 In the cellular environment

2.2.1 siRNA protection in the cell

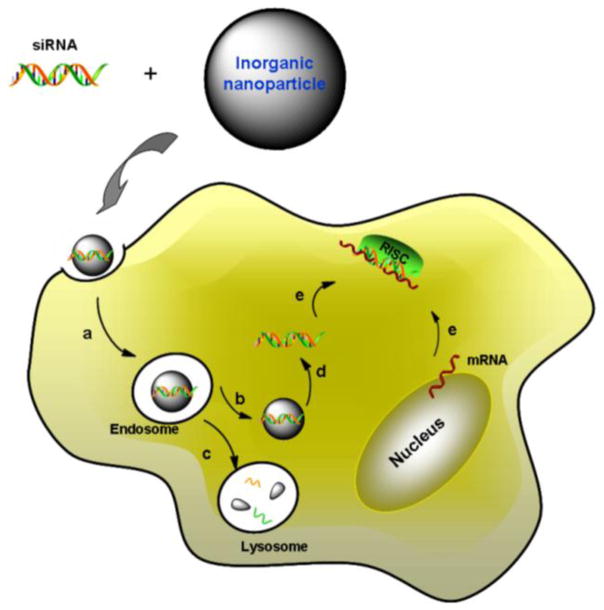

After reaching the target site, the nanocarriers need to be phagocytized by the cells to perform the siRNA therapy (Figure 2). However, the penetration of cell membrane is the first challenge faced by any nano-delivery system. Cell membrane is a biological membrane and consists of a negatively charged lipid bilayer and some embedded proteins, which protects the interior organelles from the extracellular space. Cells rely on the membrane to selectively acquire ions and some biologic molecules, and control the substances moving in and out (Kievit and Zhang, 2011). Nanoparticles are different from small molecules, and unable to enter cells by direct passive diffusion mechanisms due to their large size. The siRNA loaded nanoparticles need to translocate the cell membrane or be taken up by endocytosis process.

Figure 2.

Schematic illustration of siRNA delivery and the mechanism of RNA interference. The delivery process is divided into two phases. Phase I: Nanocarrier based siRNA loading. Phase II: intracellular siRNA release and gene silencing. (a) Internalization of siRNA nanocomplex by endocytosis; (b) the nanocomplex escapes from endosome while (c) avoiding lysosomal destruction. (d) Nanocomplex disassembles and then siRNA is released into cytoplasm; (e) siRNA and mRNA are incorporated with RISC complex for mRNA degradation.

It is an effective method to achieve intracellular access by using cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) to functionalize the nanoparticles (Veiseh et al., 2011). These peptides are typically of short cationic sequence, for example, polyarginine and the HIV transactivator TAT peptide. The CPPs have been widely adopted for delivery of therapeutic agents, such as antibodies, siRNAs, etc. (Anderson et al., 1993, Chiu et al. 2004, Santra et al., 2005). Although the mechanisms of these peptides penetrating through the cell membrane have been widely explored, the roles that the molecule size, charge delocalization, cargo, cell line and other factors play are not unified (Fonseca et al., 2009).

Many reported nanosystems are phagocytized through cell endocytosis. The cell surface is negatively charged which is beneficial for cationic nanoparticles to absorb onto the membrane via electrostatic interaction. It is interesting that negatively charged CdSe/ZnS quantum dots (QDs) with polyacrylic acid coating showed higher cellular uptake efficiency than the PEG-amine coated positively charged ones in HEK cells. The enhanced cellular uptake is due to the lipid raft/caveolae mediated endocytosis pathway but not the clathrin dependent pathway (Zhang and Monteiro-Riviere, 2009). The different distinctive endocytosis mechanisms also determine subsequent intracellular trafficking (Iversen et al., 2011). Generally, nanoparticles would be transported to acidic endosomes by clathrin-mediated endocytosis process and on the other hand, nanoparticles taken up via caveolae in lipid rafts would be directly transported to the cytoplasm. Therefore, the mode of uptake for a specific nanocarrier can strongly affect gene therapy efficacy (Rejman et al., 2005). It was found that DNA plasmids in branched PEI (25000 g/mol) complexes could exhibit effective gene expression by caveolae-mediated uptake but failed to escape from the lysosomal degradation through clathrin-mediated endocytosis.

Direct penetration through membrane barriers is an ideal method to make the nanocarrier reach the cytoplasm. However, most reported nanosystems have to quickly escape from the early endosome to prevent siRNA degradation. Because the ATP-mediated proton accumulation will make the endosome significantly acidic (pH 5.0-6.2), which then triggers the fusion of the endosomes with the degradative lysosomes (Ohkuma and Poole, 1978, Ouyang et al., 2010). Generally, the cationic lipid formed nanocarriers (e.g., liposome) can reorganize and bind the anionic phospholipids on the endosomal membrane. The binding destabilizes the endosome, and then the therapeutic siRNA is released into the cytoplasm (Xu and Szoka, 1996, Zelphati and Szoka, 1996). Moreover, “proton sponge hypothesis” is used to describe another strategy with effective buffer effect of the high concentration of protons in the endosome/lysosome and prolong the residence time of siRNA loaded onto biomaterials with low pKa values in the range of 5.5–7.0 (Mintzer and Simanek, 2009). The buffer effect of these materials increases ionic concentration, leading to the augmentation of the osmotic pressure that causes endosome swelling and rupture. Therefore, the entrapped siRNA-nanocomplexes gain access to the cytoplasm and the likelihood of siRNA release is increased.

2.2.2 siRNA release or nanocomplex disassembly

After arriving at the functional site, the siRNA should become available to interact with its target mRNA. Therefore, dissociation of siRNA from nanocarrier is considered as a key step in therapy, which is closely related to the high level of gene silencing efficacy.

Generally, the spontaneous strong electrostatic interaction between cationic nanovector and anionic siRNA is used to form the complexes. Thus, the sulfated glycosaminoglycan and other biological polyanions are employed to replace the nucleic acids on nanoparticles (Okuda et al., 2004). For example, PEI is a well-known polycationic polymer that displays excellent results in condensation of nucleic acids and transfection efficiency. In the cellular environment, various highly charged polyanions, such as heparin, chondroitin sulfate and other analogues, with high affinity for PEI would relax the nanocomplexes and release the nucleic acid cargos (Moret et al., 2001). This disassembly method has been often used to evaluate the release capacity of some cationic gene-vector (Gao et al., 2013, Wan et al., 2013). However, the competitive displacement process may be very slow because the anionic biocomponents have spatially limited access to nucleic acids complexed inside the cell (Kwon, 2012). Moreover, it is not yet fully elucidated which kind of biocomponents plays a decisive role in dissociating siRNA from the nanocomplexes in the cytoplasm.

Another approach to induce siRNA release is based on the response of the nanocarrier to intracellular stimuli (Kwon, 2012). The nanoparticle is designed to possess the functional property, including acid-responsive degradation, glutathione (GSH)-mediated reduction or other stimulation responsiveness. The stimulus reduces the charge density of the carrier, increases the space distance between the carrier and nucleic acid, and/or changes the branched structure and the hydrophilicity. Hence, the functional nanocarriers can regulate the molecular affinity to siRNA, and subsequently, rapidly release siRNA into the cytoplasm. These stimuli responsive nano-carrier systems have enormous potential in targeted cancer therapy.

3 Rigid nanoparticle based siRNA delivery

One major obstacle of siRNA therapy strategy is the lack of safe and effective delivering system. With the development of chemical synthesis methods, inorganic nanoparticles and allotropic carbon nanomaterials exhibit unique tunable properties which are suitable for biomedical applications, such as the physicochemical properties, large surface area to volume ratios and rich functional modifications (Xu et al., 2006). The rigid formulations afford the chance of payload protection and the potential of targeted siRNA delivery. Iron oxide nanoparticles, quantum dots, gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes and silica nanoparticles, have all been well investigated in the siRNA therapy and are good candidate nanoplatforms for building up rigid nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery systems.

3.1 Iron oxide nanoparticles

Iron oxide nanocrystals (IONs) are an illustrious drug delivery system and contrast agent for MR imaging due to the superparamagnetism and biodegradability. The traditional synthesis method of the magnetic nanocrystals is the precipitation of ferric and ferrous ions in aqueous solutions. This technique is facile and without the use of harmful substances. However, the products exhibit broad size distribution and present defects in the crystal structure (Ai et al., 2005). Recently, high-quality iron oxide nanoparticles have been prepared via thermal decomposition in organic phase (Sun et al., 2004). The naked nanoparticles are unstable colloids due to high surface energy and then the modification of nanocrystals becomes necessary to stabilize the particles and for biological applications. To date, lots of methods have been carried out to render IONs water-soluble. Ligand binding and amphiphilic micelle coating are the two mostly used methods.

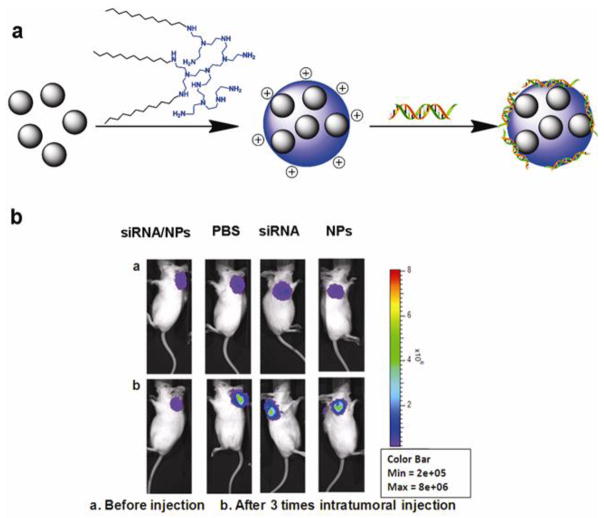

In general, electrostatic binding force is the first consideration to complex siRNA and nanocarriers. PEIs possess excessive primary and secondary amine groups in the chemical structure that enables the gene complexes to escape from endosomes through the “proton sponge” effect. Consequently, it is natural to employ PEI to conjugate IONs for binding with the oligonucleotides and form MR imaging visible agents (Zhang et al., 2010b). However, nanoparticles, modified with PEI via the ligand binding method, are usually monodispersed single nanocrystals that do not have high imaging sensitivity (Chen et al., 2009). Moreover, the nanocomposite size is not tunable and the biological application is limited. Micelles formed with amphiphiles own a hydrophobic core and hydrophilic shell, and serve as the powerful platform to carry hydrophobic agents. Hence, multiple hydrophobic SPIO nanocrystals could be gathered together into nanoclusters via the self-assemble process (Liu et al., 2011a, Wang et al., 2012, Wang et al., 2009). It is important to note that amphiphilic materials can encapsulate one or more SPIO nanocrystals inside the micelle core, depending on different formula ratios, which means that the size can be tuned (Liu et al., 2011b). Recently, Liu et al. reported a nonviral genetic nanocarrier which was constructed with a core of multiple hydrophobic IONs and a shell of alkylated polyethylenimine with low molecular weight (Liu et al., 2011b). The nanocarrier could efficiently bind with siRNA, protect siRNA from enzymatic degradation and release the complexed siRNA in the presence of heparin. Furthermore, the siRNA loading nanocarriers sufficiently silenced the target gene of interest in 4T1 cells both in vitro and in a tumor xenograft model (Figure 3) (Liu et al., 2011b). Based on the amount of amine groups of PEI on the nanoparticle surface, the nanocarrier could be easily modified with various functional ligands such as PEG or chitosan (Kievit et al., 2009, Veiseh et al., 2010, Xing et al., 2011).

Figure 3.

a) Schematic illustration of the preparation of Alkyl-PEI2k-IOs/siRNA complexes. b) The in vivo optical images of gene-silencing effect by Alkyl-PEI2k-IOs/siRNA complexes in 4T1 cells expressing firefly luciferase (Adapted with permission from Liu et al., 2011b).

However, the non-biodegradable property of PEI leads to cellular cytotoxicity. Thus, these MRI-visible transfection agents will have limited clinical use. Instead of PEI, polyarginine, polylysine, cationic lipid and some biodegrade materials are utilized to modify IONs for gene therapy (Gao et al., 2013, Veiseh et al., 2011, Wan et al., 2013). Moreover, dendrimers, with exact molecular architectures, have been considered as attractive materials for the development of nanomedicine (Dufes et al., 2005). For example, generation five poly(propyleneimine) dendrimers (PPI G5) were used to encapsulate magnetic nanoparticles, as well as coupling with PEG and specific cancer recognition peptide, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH), and the siRNA was absorbed on the surface via electrostatic attraction (Taratula et al., 2011). Such nanocomplexes efficiently suppressed BCL2 gene expression in Human LHRH positive A549 lung carcinoma cells in vitro, on the contrary, there is no evident gene silence effect in the SKOV-3 LHRH negative ovarian cancer cells (Taratula et al., 2011). Recently, stimuli-responsive nanocarries, as “smart” drug delivery tools, have been adopted to enhance the charged payloads release. For instance, the utilization of repulsive electrostatic interaction to controlled release of siRNA received a great deal of attention (Bigall et al., 2011, Curcio et al., 2012, Mok et al., 2010). After penetration into the subcellular compartments, versatile systems can invert the surface charge for a faster release and produce biodegradable monomers.

The principle of magnetic guidance has been applied for selective delivery of therapeutic agents to target sites aided by an external permanent magnetic field, which can greatly improve transfection rates due to high local accumulation of the magnetic vector (Shubayev et al., 2009). For example, cationic lipid coated magnetic nanoparticles exhibit excellent stability under a fluidic condition and can accumulate at desired places with a gradient magnetic field (del Pino et al., 2010). The siRNA silencing efficiency of magnetic vector is greatly enhanced with the magnetic force-assisted transfection. However, the therapeutic range is only restricted to areas near the magnet in HeLa cells in vitro (del Pino et al., 2010). In another study, PEI coated iron oxide nanoparticles were designed to deliver siRNA and green fluorescent protein (GFP) plasmids. Driven by an external magnetic field, nanovector introduced high transfection efficiency, but showing maximum transfection depth of only about 2.1~2.3 mm in 3D culture of NIH 3T3 cells with the help of an external magnetic field (Zhang et al., 2010b). It is worthwhile to note that magnetic localization process of the nanoparticles is likely assisted via the EPR effect. However, there is no proof that magnetic targeted delivery is better than EPR effect mediated passive delivery or active targeting delivery yet.

3.2 Quantum dots

Semiconductor quantum dots (QDs), exhibit special electronic and optical properties that are tunable with different sizes and shapes (Alivisatos, 1996). QDs can emit narrow symmetric bands under a wide excitation range, and possess anti-photobleaching stability, which is superior to the traditional organic dyes and exhibit advanced molecular imaging possibilities as well as ultrasensitive bioassays and diagnostics (Gao et al., 2004, Zhang and Wang, 2012). Current researches show more interest in using QDs as an effective theranostic agent to deliver siRNA and track individual molecules (Knipe et al., 2013, Law et al., 2012).

The charge to charge complexation of cationic QDs with anionic siRNA shows effective siRNA binding and intracellular delivery. For example, a kind of cationic arginine-functional-modified CdSe/ZnSe QDs were prepared as cationic carriers and showed very low cytotoxicity and efficient knocking down effect of HPV18 E6 gene in the HeLa cells (Li et al., 2011). Different from noncovalent bonding, the thiol-ene chemistry was reported to have highly effective siRNA delivery on the PEGlyated multifunctional QDs (Derfus et al., 2007). In another report, however, it showed greater silencing effect when siRNA was attached to the PEGlyated QDs by labile disulfide cross-linkers (Derfus et al., 2007) than by nonlabile thioether bond.

To reconcile these seemingly contradictory findings, Singh et al. presented a systematic study to evaluate siRNA coupling strategies using a PEGylated QDs system loaded with three siRNA macromolecules per nanoparticle (Singh et al., 2010). It was found that the target gene (GFP-Ago2/Luc-CXCR4) in HeLa cells was efficiently knocked down by the labile formulation (>90%). The result was probably due to the susceptible bond which can be cleaved in the reducing intracellular environment, then siRNA were released from the nanoparticle, subsequently, become available to complex with the RISC for efficient silencing effect. However, in the other groups, the siRNA was firmly bound with QDs and exhibited different outcomes. The poor result was only found in QDs system with the short length stable cross-linker about 24.6 Å. The gene silencing efficiency improved with the linker spacer arm length increase, which is likely due to the space distance between nanosystem and the RISC. The steric hindrance of nanoparticle caused the poor availability of siRNA to combine the RISC. However, the nanoparticle with a longer tether may enhance the macromolecule flexibility and improve accessibility of siRNA (Singh et al., 2010).

The use of QDs in clinical application has been questioned due to their inherent cytotoxicity. Most of QDs contain highly toxic elements such as cadmium (Cd) or tellurium (Te). Taken CdSe QDs as an example, the Cd2+ ions would release into the cytoplasm during the biodegradation process in the cell. Subsequently, the ions bind to the sulfohydryl groups of mitochondria proteins and then inhibit mitochondrial respiration (Klein et al., 2009, Rikans and Yamano, 2000). Although coating with biocompatible materials on QDs would reduce the toxicity, the hidden risks still exist (Zhang et al., 2006). In response to the above issues, non-toxic QDs have been investigated in the recent years, such as AgInS2 and CuInS2 which are typical I-III-VI type nanoparticles and offer better control of band-gap energies (Castro et al., 2004, Torimoto et al., 2007).

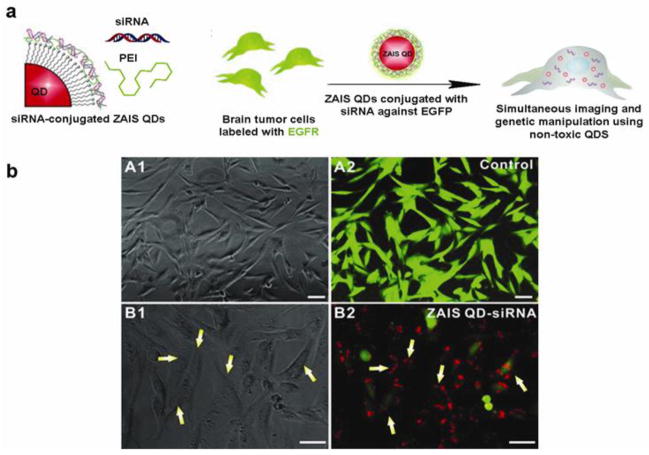

Recently, Subramaniam et al. developed a library of biocompatible ZnxS-AgyIn1-yS2 (ZAIS) QDs with tunable physical properties using a facile sonochemical synthetic method. The physicochemical properties of ZAIS QDs can be easily tuned over the entire visible spectrum by varying the chemical composition of the precursors. Advantages of the sonochemical synthetic approach include a fast reaction rate, controllable reaction conditions and the ability to form nanoparticles with uniform shapes and narrow size-distributions. The functional nanocomposites loaded with siRNA showed efficient cell uptake and target gene silencing effects as evidenced by the intracellular red fluorescence of the QDs in U87-EGFP cells with negligible cytotoxicity (Figure 5) (Subramaniam et al., 2012), thereby allowing them to be used for molecular imaging and effective delivery of siRNA.

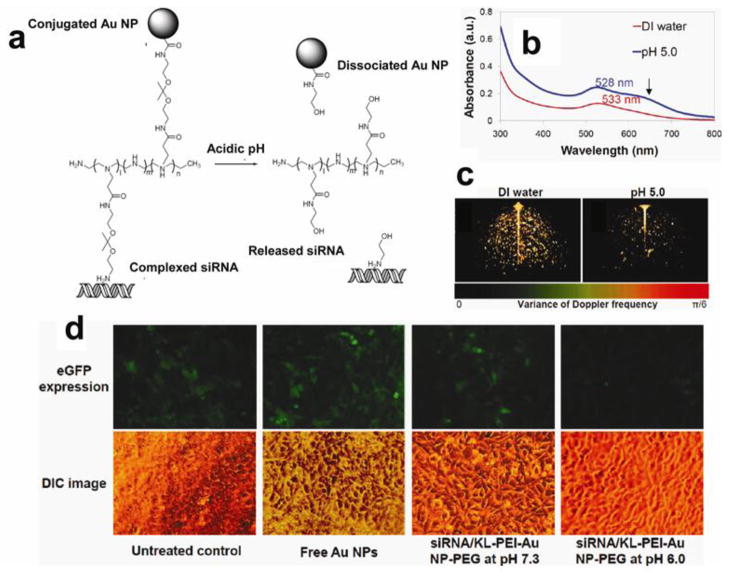

Figure 5.

(a) Au nanoparticles modified with pH sensitive macromolecules. (b) UV absorbance changes of the acid-responsive nanoparticles before (red) and after (blue) acid hydrolysis. (c) Three-dimensional SD-OCT images showed the optical coherence property changes of the acid-responsive nanoparticles with acid-hydrolysis. (d) Gene silencing efficiency of the acid-responsive nanoparticles in vitro under a tumor-mimicking condition in eGFP-expressing NIH 3T3 cells (Adapted with permission from Shim et al., 2010).

3.3 Au nanoparticle

Due to the unique surface plasmon resonance (SPR) property, gold nanoparticles have been widely used for DNA mismatch detection, bioimaging diagnosis and photothermal therapy (Jiang et al., 2012, Zhang et al., 2013). In addition, they can be easily tailored to a desirable size and shape, and can be modified with thiolated molecules, which make gold nanoparticles an excellent gene vector. Lee et al. reported a cysteamine modified cationic gold nanovector with gold-thiol bond, which exhibited siRNA loading capability through electrostatic interactions and significantly inhibited the expression of target GFP gene with low cytotoxicity in PC-3 cells (Lee et al., 2008). Protamine, PEI, dendrons and other positively charged macromolecules have also been used to modify gold particles and deliver siRNA (DeLong et al., 2009, Kim et al., 2012, Song et al., 2010).

A new type of siRNA delivery system was recently prepared though the layer-by-layer approach (Elbakry et al., 2009, Lee et al., 2011). The layer-by-layer modification is an easy assembly procedure, which is prepared by alternating the addition of multiple oppositely charged layers on the surface of particles based on charge-charge interactions between polycations and polyanions. In one report, poly-L-lysine (a biodegradable polycation material) and siRNA (a polyanion material) were loaded onto gold nanoparticles, and these self-assembled nanoparticles could load multilayers of therapeutic siRNA. The siRNA silencing effect was demonstrated to be correlated with the number of siRNA layers in MDA-MB231-luc2 cells (Lee et al., 2011).

Shim et al. demonstrated the feasibility of achieving combined diagnosis and gene therapy for cancer based on gold nanovector with the SPR effect (Figure 5) (Shim et al., 2010). The nanovehicle was developed through acid responsive ketalized linear PEI encapsulated on the gold nanoparticles. Then siRNA was absorbed on the vector. In a mildly acidic tumor environment, the gold vector released the cargo and generated various optical signal changes such as blue-shifted UV absorbance, diminished scattering intensity, and increased variance of Doppler frequency. Then these behaviors of nanoparticle, which were triggered by molecular events in a diseased lesion, obtained a sensitive contrast image via optical coherence tomography (Shim et al., 2010). The functionalized gold nanopaticles provide a new paradigm for stimuli-responsive optical imaging and stimuli-enhanced siRNA delivery.

3.4 Calcium phosphate Nanoparticle

Calcium phosphate (CaP) has been employed as an efficient, biocompatible and biodegradable gene vector for many years (Jordan et al., 1996). CaP does not trigger immune response and does not toxic by-products, and is thus suitable for clinical application (Chen et al., 2004, Rangavittal et al., 2000). Additionally, CaP is stable under physiological condition (pH 7.4) and is dissolvable at low pH in the endosomal compartment, all of which offer great advantages in the controlled release process (Pinto et al., 2011).

However, in the conventional synthesis method, it is difficult to prepare CaP at nanoscale, because the growth of nanocrystals is uncontrollable after mixing calcium and phosphate solutions without surfactants (Kakizawa et al., 2004). Like the other inorganic nanoparticle, the colloidal stability and tunable size of CaP are very critical for siRNA delivery in vivo. In an early study, poly(ethylene glycol)-block-poly(aspartic acid) was chosen as a base material to prepare CaP nanoparticles for siRNA delivery (Kakizawa et al., 2004). These hybrid nanoparticles are of core-shell structure. The siRNA was entrapped in the CaP core and surrounded by a hydrophilic tethered layer of PEG. In addition, the size of nanoparticle was tunable depending on the polymer concentrations. Based on the acid sensitive characteristic of CaP for controlled release, the reporter gene silencing effect was successfully demonstrated in HeLa cells in vitro (Kakizawa et al., 2004). Based on this work, the PEG conjugated charge-conversion polymer (PEG-CCP), which could produce polycation in acidic endosomes and then induce the endosomal membrane destabilization, was used to improve the siRNA loading efficiency and gene knockdown efficacy in the novel CaP system (Pittella et al., 2011).

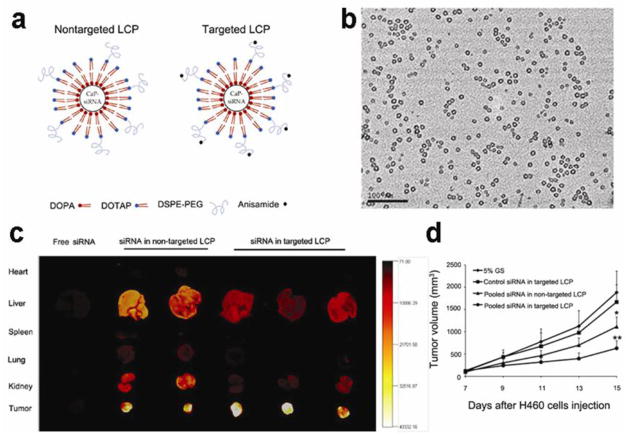

Recently, a water-in-oil microemulsion precipitation method was used to prepare nano-sized lipid modified calcium phosphate (LCP) as a siRNA vector (Li et al., 2010). After being coated by post-insertion of PEG and target ligand, the nanocomplexes silenced the luciferase report gene by about 70% and 50% for the H-460 cells in culture and in a xenograft model, respectively. Furthermore, the de-assembly process of LCP nanoparticle in the endosome was demonstrated by calcium specific dye Fura-2 which showed the increase of intracellular Ca2+ concentration (Li et al., 2010). In another study, an anionic lipid served as the outer leaflet lipid that changes hydrophiphilicity of the CaP core. With an asymmetric lipid bilayer coating, the CaP nanoparticles were about 25 to 30 nm in diameter and showed highly effective delivery of siRNA in subcutaneous H460 and A549 tumor models (Figure 6) (Yang et al., 2012).

Figure 6.

a) Illustration of the CaP nanoparticles modified with lipid and non-targeted/targeted ligands. (b) TEM images of functionalized CaP nanoparticles. c) In vivo biodistribution of CaP nanoparticles carrying Texas Red-siRNA in subcutaneous A549 tumor model. d) The oncogene silencing effect in subcutaneous H460 tumor model (Adapted with permission from Yang et al., 2012).

3.5 Carbon Nanotubes

Carbon nanotubes are well-ordered hollow cylindrical molecules in a series of hexagonal lattice structure formed through carbon atoms with π-bonding. It can be classified into two dominant forms, single walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). Both SWCNTs and MWCNTs can be functionalized with a pyrrolidine ring and then a wide variety of biomolecules, imaging agents, and drugs can be attached (Cheung et al., 2010).

The first report of utilizing carbon nanotubes as gene vector was published in 2004 (Pantarotto et al., 2004). Since then, carbon nanomaterials were widely applied in gene therapy based on their appealing features, such as unparalleled optical/electrical properties and needle-like shape. Based on the Prato reaction, the cationic ammonium-functionalized carbon nanotubes could effectively condense oligodeoxynucleotides for gene delivery (Bianco et al., 2005). More importantly, the carbon nanotubes use a nanoneedle endocytosis-independent mechanism for cell membrane penetration and show little toxic effect on the treated cells (Cheung et al., 2010, Singh et al., 2005).

Van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions between the carbon nanotube side wall and hydrophobic components have been employed as noncovalent linker to construct functional nanotubes. For example, Liu et al. used amine-terminated phospholipid-PEG to functionalize nanotubes and then linked the thiol-modified siRNA cargo molecules on the surface of nanotubes. The resulted siRNA nanocomplexes led to approximately 60% knockdown of CXCR4 receptors on human T cells (Liu et al., 2007). Notably, the strong Raman scattering, NIR fluorescence emission and photoacoustic characteristics of nanotubes can also be used to monitor the gene delivery and the therapeutic effects.

3.6 Silica nanoparticles

Silica nanoparticles can be easily modified chemically and biologically for gene delivery. Porous silica nanoparticles, in particular, possess a range of mesoporous structures with high surface area, making them interesting as nanocarriers (Hom et al., 2010, Xia et al., 2009). With the well-developed surface chemistry, functionalized silica nanomaterials have been harnessed as a promising biocompatible drug/gene delivery vehicle (Xia et al., 2009). For instance, non-covalent attachment of PEI on the surface makes the nanoparticle an efficient system to protect and deliver siRNA (Hom et al., 2010, Xia et al., 2009).

Various multifunctional platforms are expected to synergistically deliver chemotherapeutic drugs and nucleic acids to overcome chemoresistance in cancer therapy. Recently, it was reported that phosphonate modified silica nanoparticles were functionalized with PEI to transport doxorubicin (Dox) as well as P-glycoprotein (PgP) siRNA into drug-resistant cancer cells (Meng et al., 2010). As known, the expression of Pgp protein is the major cause of multiple drug resistance in cancer cells. Thus this co-delivery system effectively suppressed targeted gene activation, and improved cytotoxic killing in KB-V1 cells in vitro (Meng et al., 2010). The novel chemotherapy formulation has great potential to overcome both the dose-limiting side effects of conventional chemotherapeutics and the therapeutic failure resulting from multi-drug resistance. Furthermore, the rapid advancement of nanotechnology over the past decade has opened opportunities to develop functional silica nanoparticles with the capability to serve as both siRNA delivery vectors and molecular imaging agents. Recently, a yolk-shell nanocapsule structure was prepared with PEI coated fluorescent mesoporous SiO2 shells and Fe3O4 cores for simultaneous fluorescent tracking and magnetic imaging guided siRNA delivery in Hela cells (Zhang et al., 2012).

4 Conclusions and future perspectives

Rigid nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery systems have shown great success. In the current article, we highlighted some commonly used inorganic nanoparticle and allotropic carbon nanomaterial formulas with unique physicochemical properties for effective loading and intracellular delivery of siRNAs. Advantages of using rigid nanoparticle in siRNA delivery include the following: 1) many of the nanoparticles are biologically degradable with minimal cytotoxicity; 2) easy to modify physicochemical characteristics and simple purification procedures; 3) functional ligand conjugation for targeted delivery of siRNA; 4) rigid nanoparticles allow for co-delivery of siRNA and chemotherapeutics for additive or synergistic effect; 5) Monitoring siRNA delivery by visualizing the rigid nanoparticles themselves or through proper labeling. In a word, rigid nanoparticles constitute an efficient multifunctional platform with unique advantages in siRNA delivery, targeting, controlled release, and imaging.

Generally speaking, the size, surface modification and charge density are critical parameters that determine the interaction between the nanoparticle and siRNA and subsequently the therapeutic outcome. The most common strategy is to make rigid (mostly inorganic and carbon-based) nanovectors with high positive charge density for electrostatic interaction with siRNA. As nearly all rigid nanovectors are incorporated into the cells by means of endocytosis, the use of ligands, antibody fragments or chemical modifications to the nanovectors for specific targeting can increase cellular uptake and result in higher transfection efficiency.

Rigid nanoparticles would form interface with biological targets which is often more complex than one can predict. Only a deeper understanding of the biological physiology will help us to design intelligent rigid nanoparticles for more effective delivery of siRNA to the target of interest. Rigid nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery systems can also function as imaging agents, which means that the functional nanovector not only can load and deliver siRNA effectively, but also can be tracked by different imaging techniques. Thus, future work will likely involve development of multifunational theranostic nanoplatforms in order to obtain an efficient and nontoxic delivery method for siRNA in vitro and in vivo, which also allows to track the fate of the nanoparticles and to monitor the treatment efficacy in real time.

Despite the many proposed advantages of rigid nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery systems, increasing concerns have been expressed on their potential adverse human health effects. More in vivo work is needed to assess the applicability of these nanomaterials as siRNA delivery agents. Generally, the aggregate or disintegrated nanoparticles can be toxic and effort is needed to keep their desirable properties intact under physiological conditions. There are several potentially toxic effects associated with exposure to inorganic nanoparticles, such as the generation of reactive oxygen species, formation of apoptotic bodies, and impaired mitochondrial function, etc. Furthermore, future studies will need to carefully consider the chemical modifications to incorporate into the siRNAs to minimize the problem of off-targeting, such as activation of an off-target immune response.

The evaluation of the safety of rigid nanoparticle, especially for long-term application, is a grand challenge. The chronic toxicity and metabolism mechanisms of rigid nanoparticles in the body need to be revealed before potential clinical applications. Thus, it is crucial to establish standard guidelines/protocols for the determination of the toxicity of rigid nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo. Efforts to address the safety issues are currently ongoing, and should remain the focus in the future studies.

Figure 4.

a) Schematic illustration of the preparation of ZnS-AgInS2 QDs for simultaneous imaging and delivery of siRNA. b) In vitro testing of ZAIS QDs-siRNA nanocomplexes against EGFP in U87-EGFP glioblastoma cells. The fluorescence image showed that the silenced cells have internalized the siRNA-QDs (red) (Adapted with permission from Subramaniam et al., 2012).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Major State Basic Research Development Program of China (973 Program) (2013CB733802, 2014CB744503), National Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81101101, 81371596, 51273165, 51203177), Key Project of Chinese Ministry of Education (212149), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2013121039) and the Intramural Research Program (IRP) of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ai H, Flask C, Weinberg B, Shuai X, Pagel MD, Farrell D, et al. Magnetite-loaded polymeric micelles as ultrasensitive magnetic-resonance probes. Adv Mater. 2005;17:1949–52. [Google Scholar]

- Alivisatos AP. Semiconductor clusters, nanocrystals, and quantum dots. Science. 1996;271:933–7. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson DC, Nichols E, Manger R, Woodle D, Barry M, Fritzberg AR. Tumor-Cell Retention of Antibody Fab Fragments Is Enhanced by an Attached Hiv Tat Protein-Derived Peptide. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 1993;194:876–84. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YH, Park K. Targeted drug delivery to tumors: Myths, reality and possibility. J Control Release. 2011;153:198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:401–10. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya S, Kudgus RA, Bhattacharya R, Mukherjee P. Inorganic Nanoparticles in Cancer Therapy. Pharm Res. 2011;28:237–59. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0318-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco A, Hoebeke J, Godefroy S, Chaloin O, Pantarotto D, Briand JP, et al. Cationic carbon nanotubes bind to CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and enhance their immunostimulatory properties. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:58–9. doi: 10.1021/ja044293y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigall NC, Curcio A, Leal MP, Falqui A, Palumberi D, Di Corato R, et al. Magnetic Nanocarriers with Tunable pH Dependence for Controlled Loading and Release of Cationic and Anionic Payloads. Adv Mater. 2011;23:5645–50. doi: 10.1002/adma.201103505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai HC, Li ZB, Huang CW, Shahinian AH, Wang H, Park R, et al. Evaluation of Copper-64 Labeled AmBaSar Conjugated Cyclic RGD Peptide for Improved MicroPET Imaging of Integrin alpha(v)beta(3) Expression. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:1417–24. doi: 10.1021/bc900537f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzolari A, Oliviero I, Deaglio S, Mariam G, Biffoni M, Sposi NM, et al. Transferrin receptor 2 is frequently expressed in human cancer cell lines. Blood Cell Mol Dis. 2007;39:82–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–57. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro SL, Bailey SG, Raffaelle RP, Banger KK, Hepp AF. Synthesis and characterization of colloidal CuInS2 nanoparticles from a molecular single-source precursor. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:12429–35. [Google Scholar]

- Cedervall T, Lynch I, Foy M, Berggad T, Donnelly SC, Cagney G, et al. Detailed identification of plasma proteins adsorbed on copolymer nanoparticles. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:5754–6. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan LW, Wang YN, Lin LY, Upton MP, Hwang JH, Pun SH. Synthesis and characterization of anti-EGFR fluorescent nanoparticles for optical molecular imaging. Bioconjugate chemistry. 2013;24:167–75. doi: 10.1021/bc300355y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Chen W, Wu Z, Yuan R, Li H, Gao J, et al. MRI-visible polymeric vector bearing CD3 single chain antibody for gene delivery to T cells for immunosuppression. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1962–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen QZ, Wong CT, Lu WW, Cheung KM, Leong JC, Luk KD. Strengthening mechanisms of bone bonding to crystalline hydroxyapatite in vivo. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ZL, Al Zaki A, Hui JZ, Muzykantov VR, Tsourkas A. Multifunctional Nanoparticles: Cost Versus Benefit of Adding Targeting and Imaging Capabilities. Science. 2012;338:903–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1226338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung W, Pontoriero F, Taratula O, Chen AM, He HX. DNA and carbon nanotubes as medicine. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2010;62:633–49. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu YL, Ali A, Chu CY, Cao H, Rana TM. Visualizing a correlation between siRNA localization, cellular uptake, and RNAi in living cells. Chem Biol. 2004;11:1165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KJ, Wang X, Nie SM, Chen Z, Shin DM. Therapeutic nanoparticles for drug delivery in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:1310–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collnot EM, Baldes C, Wempe MF, Hyatt J, Navarro L, Edgar KJ, et al. Influence of vitamin E TPGS poly(ethylene glycol) chain length on apical. efflux transporters in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Control Release. 2006;111:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow DM, Williams L, Colcher D, Wong JYC, Raubitschek A, Shively JE. Combined Radioimmunotherapy and chemotherapy of breast tumors with Y-90-labeled anti-Her2 and anti-CEA antibodies with Taxol. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:1117–25. doi: 10.1021/bc0500948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio A, Marotta R, Riedinger A, Palumberi D, Falqui A, Pellegrino T. Magnetic pH-responsive nanogels as multifunctional delivery tools for small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecules and iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) Chem Commun. 2012;48:2400–2. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17223b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhier F, Feron O, Preat V. To exploit the tumor microenvironment: Passive and active tumor targeting of nanocarriers for anti-cancer drug delivery. J Control Release. 2010;148:135–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Fougerolles A, Vornlocher HP, Maraganore J, Lieberman J. Interfering with disease: a progress report on siRNA-based therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:443–53. doi: 10.1038/nrd2310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pino P, Munoz-Javier A, Vlaskou D, Rivera Gil P, Plank C, Parak WJ. Gene Silencing Mediated by Magnetic Lipospheres Tagged with Small Interfering RNA. Nano Lett. 2010;10:3914–21. doi: 10.1021/nl102485v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong RK, Akhtar U, Sallee M, Parker B, Barber S, Zhang J, et al. Characterization and performance of nucleic acid nanoparticles combined with protamine and gold. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6451–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derfus AM, Chen AA, Min DH, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN. Targeted quantum dot conjugates for siRNA delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1391–6. doi: 10.1021/bc060367e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufes C, Uchegbu IF, Schatzlein AG. Dendrimers in gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2005;57:2177–202. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelstein ML, Abedi MR, Wixon J. Gene therapy clinical trials worldwide to 2007 - an update. J Gene Med. 2007;9:833–42. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbakry A, Zaky A, Liebkl R, Rachel R, Goepferich A, Breunig M. Layer-by-Layer Assembled Gold Nanoparticles for siRNA Delivery. Nano Lett. 2009;9:2059–64. doi: 10.1021/nl9003865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;411:494–8. doi: 10.1038/35078107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias DR, Poloukhtine A, Popik V, Tsourkas A. Effect of ligand density, receptor density, and nanoparticle size on cell targeting. Nanomed-Nanotechnol. 2013;9:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Novotny W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2005;333:328–35. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu SQ, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–11. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca SB, Pereira MP, Kelley SO. Recent advances in the use of cell-penetrating peptides for medical and biological applications. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2009;61:953–64. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank PG, Marcel YL. Apolipoprotein A-I: structure-function relationships. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:853–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Liu W, Xia Y, Li W, Sun J, Chen HW, et al. The promotion of siRNA delivery to breast cancer overexpressing epidermal growth factor receptor through anti-EGFR antibody conjugation by immunoliposomes. Biomaterials. 2011a;32:3459–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JH, Chen K, Miao Z, Ren G, Chen XY, Gambhir SS, et al. Affibody-based nanoprobes for HER2-expressing cell and tumor imaging. Biomaterials. 2011b;32:2141–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.11.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L, Xie L, Long X, Wang Z, He C-Y, Chen Z-Y, et al. Efficacy of MRI visible iron oxide nanoparticles in delivering minicircle DNA into liver via intrabiliary infusion. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3688–96. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao XH, Cui YY, Levenson RM, Chung LWK, Nie SM. In vivo cancer targeting and imaging with semiconductor quantum dots. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:969–76. doi: 10.1038/nbt994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatter KC, Brown G, Trowbridge IS, Woolston RE, Mason DY. Transferrin Receptors in Human-Tissues - Their Distribution and Possible Clinical Relevance. J Clin Pathol. 1983;36:539–45. doi: 10.1136/jcp.36.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashida M, Mahato RI, Kawabata K, Miyao T, Nishikawa M, Takakura Y. Pharmacokinetics and targeted delivery of proteins and genes. J Control Release. 1996;41:91–7. [Google Scholar]

- Heine M, Freund B, Nielsen P, Jung C, Reimer R, Hohenberg H, et al. High Interstitial Fluid Pressure Is Associated with Low Tumour Penetration of Diagnostic Monoclonal Antibodies Applied for Molecular Imaging Purposes. Plos One. 2012;7:e36258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heldin CH, Rubin K, Pietras K, Ostman A. High interstitial fluid pressure - An obstacle in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:806–13. doi: 10.1038/nrc1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellstrand E, Lynch I, Andersson A, Drakenberg T, Dahlback B, Dawson KA, et al. Complete high-density lipoproteins in nanoparticle corona. Febs J. 2009;276:3372–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst RS, Shin DM. Monoclonal antibodies to target epidermal growth factor receptor-positive tumors - A new paradigm for cancer therapy. Cancer. 2002;94:1593–611. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill E, Shukla R, Park SS, Baker JR. Synthetic PAMAM-RGD conjugates target and bind to odontoblast-like MDPC 23 cells and the predentin in tooth organ cultures. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1756–62. doi: 10.1021/bc0700234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom C, Lu J, Liong M, Luo HZ, Li ZX, Zink JI, et al. Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Facilitate Delivery of siRNA to Shutdown Signaling Pathways in Mammalian Cells. Small. 2010;6:1185–90. doi: 10.1002/smll.200901966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XH, Peng XH, Wang YQ, Wang YX, Shin DM, El-Sayed MA, et al. A Reexamination of Active and Passive Tumor Targeting by Using Rod-Shaped Gold Nanocrystals and Covalently Conjugated Peptide Ligands. ACS nano. 2010;4:5887–96. doi: 10.1021/nn102055s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida T, Ichihara M, Wang X, Yamamoto K, Kimura J, Majima E, et al. Injection of PEGylated liposomes in rats elicits PEG-specific IgM, which is responsible for rapid elimination of a second dose of PEGylated liposomes. J Control Release. 2006;112:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iversen TG, Skotland T, Sandvig K. Endocytosis and intracellular transport of nanoparticles: Present knowledge and need for future studies. Nano Today. 2011;6:176–85. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen M, Oyen WJG, Massuger LFAG, Frielink C, Dijkgraaf I, Edwards DS, et al. Comparison of a monomeric and dimeric radiolabeled RGD-peptide for tumor targeting. Cancer Biother Radio. 2002;17:641–6. doi: 10.1089/108497802320970244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W, Kim BYS, Rutka JT, Chan WCW. Nanoparticle-mediated cellular response is size-dependent. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:145–50. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XM, Wang LM, Wang J, Chen CY. Gold nanomaterials: preparation, chemical modification, biomedical applications and potential risk assessment. Appl Biochem Biotech. 2012;166:1533–51. doi: 10.1007/s12010-012-9548-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan M, Schallhorn A, Wurm FM. Transfecting mammalian cells: optimization of critical parameters affecting calcium-phosphate precipitate formation. Nucleic acids Res. 1996;24:596–601. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakizawa Y, Furukawa S, Kataoka K. Block copolymer-coated calcium phosphate nanoparticles sensing intracellular environment for oligodeoxynucleotide and siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2004;97:345–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kano MR, Bae Y, Iwata C, Morishita Y, Yashiro M, Oka M, et al. Improvement of cancer-targeting therapy, using nanocarriers for intractable solid tumors by inhibition of TGF-beta signaling. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3460–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611660104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke CY, Mathias CJ, Green MA. Targeting the tumor-associated folate receptor with an In-111-DTPA conjugate of pteroic acid. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:7421–6. doi: 10.1021/ja043006n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kievit FM, Veiseh O, Bhattarai N, Fang C, Gunn JW, Lee D, et al. PEI-PEG-Chitosan-Copolymer-Coated Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Safe Gene Delivery: Synthesis, Complexation, and Transfection. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19:2244–51. doi: 10.1002/adfm.200801844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kievit FM, Zhang MQ. Cancer Nanotheranostics: Improving Imaging and Therapy by Targeted Delivery Across Biological Barriers. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H217–H47. doi: 10.1002/adma.201102313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Jeong JH, Lee SH, Kim SW, Park TG. PEG conjugated VEGF siRNA for anti-angiogenic gene therapy. J Control Release. 2006;116:123–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ST, Chompoosor A, Yeh YC, Agasti SS, Solfiell DJ, Rotello VM. Dendronized Gold Nanoparticles for siRNA Delivery. Small. 2012;8:3253–6. doi: 10.1002/smll.201201141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein S, Zolk O, Fromm MF, Schrodl F, Neuhuber W, Kryschi C. Functionalized silicon quantum dots tailored for targeted siRNA delivery. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2009;387:164–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.06.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knipe JM, Peters JT, Peppas NA. Theranostic agents for intracellular gene delivery with spatiotemporal imaging. Nano Today. 2013;8:21–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nantod.2012.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuenen B, Witteveen PO, Ruijter R, Giaccone G, Dontabhaktuni A, Fox F, et al. A Phase I Pharmacologic Study of Necitumumab (IMC-11F8), a Fully Human IgG(1) Monoclonal Antibody Directed against EGFR in Patients with Advanced Solid Malignancies. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1945–23. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon IK, Lee SC, Han B, Park K. Analysis on the current status of targeted drug delivery to tumors. J Control Release. 2012;164:108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon YJ. Before and after Endosomal Escape: Roles of Stimuli-Converting siRNA/Polymer Interactions in Determining Gene Silencing Efficiency. Accounts Chem Res. 2012;45:1077–88. doi: 10.1021/ar200241v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law WC, Mahajan SD, Kopwitthaya A, Reynolds JL, Liu MX, Liu X, et al. Gene Silencing of Human Neuronal Cells for Drug Addiction Therapy using Anisotropic Nanocrystals. Theranostics. 2012;2:695–704. doi: 10.7150/thno.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layzer JM, McCaffrey AP, Tanner AK, Huang Z, Kay MA, Sullenger BA. In vivo activity of nuclease-resistant siRNAs. Rna. 2004;10:766–71. doi: 10.1261/rna.5239604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Bae KH, Kim SH, Lee KR, Park TG. Amine-functionalized gold nanoparticles as non-cytotoxic and efficient intracellular siRNA delivery carriers. Int J Pharmaceut. 2008;364:94–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Han MS, Asokan S, Tung CH. Effective Gene Silencing by Multilayered siRNA-Coated Gold Nanoparticles. Small. 2011;7:364–70. doi: 10.1002/smll.201001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Chen YC, Tseng YC, Mozumdar S, Huang L. Biodegradable calcium phosphate nanoparticle with lipid coating for systemic siRNA delivery. J Control Release. 2010;142:416–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Zhao MX, Su H, Wang YY, Tan CP, Ji LN, et al. Multifunctional quantum-dot-based siRNA delivery for HPV18 E6 gene silence and intracellular imaging. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7978–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SD, Huang L. Nanoparticles evading the reticuloendothelial system: Role of the supported bilayer. Bba-Biomembranes. 2009;1788:2259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SD, Huang L. Stealth nanoparticles: High density but sheddable PEG is a key for tumor targeting. J Control Release. 2010;145:178–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WJ, Szoka FC. Lipid-based nanoparticles for nucleic acid delivery. Pharm Res. 2007;24:438–49. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Choi KY, Bhirde A, Swierczewska M, Yin J, Lee SW, et al. Sticky Nanoparticles: A Platform for siRNA Delivery by a Bis(zinc(II) dipicolylamine)-Functionalized, Self-Assembled Nanoconjugate. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2012;51:445–9. doi: 10.1002/anie.201105565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Wang ZY, Lu J, Xia CC, Gao FB, Gong QY, et al. Low molecular weight alkyl-polycation wrapped magnetite nanoparticle clusters as MRI probes for stem cell labeling and in vivo imaging. Biomaterials. 2011a;32:528–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu G, Xie J, Zhang F, Wang Z, Luo K, Zhu L, et al. N-Alkyl-PEI-Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanoclusters for Efficient siRNA Delivery. Small. 2011b;7:2742–9. doi: 10.1002/smll.201100825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Chen Z, Liu C, Yu D, Lu Z, Zhang N. Gadolinium-loaded polymeric nanoparticles modified with Anti-VEGF as multifunctional MRI contrast agents for the diagnosis of liver cancer. Biomaterials. 2011c;32:5167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Winters M, Holodniy M, Dai HJ. siRNA delivery into human T cells and primary cells with carbon-nanotube transporters. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:2023–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZF, Yan YJ, Chin FT, Wang F, Chen XY. Dual Integrin and Gastrin-Releasing Peptide Receptor Targeted Tumor Imaging Using F-18-labeled PEGylated RGD-Bombesin Heterodimer F-18-FB-PEG(3)-Glu-RGD-BBN. J Med Chem. 2009a;52:425–32. doi: 10.1021/jm801285t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZF, Yan YJ, Liu SL, Wang F, Chen XY. F-18, Cu-64, and Ga-68 Labeled RGD-Bombesin Heterodimeric Peptides for PET Imaging of Breast Cancer. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009b;20:1016–25. doi: 10.1021/bc9000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]