Abstract

To estimate the long term cumulative risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or worse (CIN3+ after an abnormal cervical Pap test and to assess the effect of HIV infection on that risk. Participants in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study were followed semiannually for up to 10 years. Pap tests were categorized according to the 1991 Bethesda system. Colposcopy was prescribed within six months of any abnormality. Risk for biopsy-confirmed CIN3 or worse after abnormal cytology and at least 12 months follow-up was assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using log-rank tests. Risk for CIN2 or worse was also assessed, since CIN2 is the threshold for treatment. After a median of 3 years of observation, 1,947 (85%) women subsequently presented for colposcopy (1571 [81%] HIV seropositive, 376 [19%] seronegative). CIN2 or worse was found in 329 (21%) of HIV seropositive and 42 (11%) seronegative women. CIN3 or worse was found in 141 (9%) of seropositive and 22 (6%) seronegative women. In multivariable analysis, after controlling for cytology grade HIV seropositive women had an increased risk for CIN2 or worse (H.R. 1.66, 95% C.I 1.15, 2.45) but higher risk for CIN3 or worse did not reach significance (H.R. 1.33, 95% C.I. 0.79, 2.34).HIV seropositive women with abnormal Paps face a marginally increased and long-term risk for cervical disease compared to HIV seronegative women, but most women with ASCUS and LSIL Pap results do not develop CIN2 or worse despite years of observation.

Keywords: HIV in women, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, Pap test

Introduction

HIV seropositive women have a high risk for Pap abnormalities (1). However, most of these abnormal Pap tests are atypical or low grade (1, 2), and many will regress without treatment (3). Immediate colposcopic assessment after a Pap with minor abnormalities often shows no abnormality or low grade changes consistent with infection by human papillomavirus (HPV) (4, 5); cancer is uncommon (6). This is the case despite a high prevalence of carcinogenic HPV that may persist or re-activate, especially in HIV seropositive women with severe immunodeficiency (7-9).

The 1% annual incidence of high grade Pap abnormalities in HIV seropositive women is higher than that in seronegative women (2), and cervical cancer risk is also elevated (10), although the largest U.S. cohort of HIV seropositive women showed no significant increased cancer risk (11). Studies of long term risk following an abnormal Pap are needed because suboptimal colposcopy compliance (12) and limited sensitivity of colposcopy (13, 14) may result in a delay in histologic diagnosis.

The goals of this study were to estimate the long term cumulative risk for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3, adenocarcinoma in situ or cancer (CIN3 or worse) after an abnormal cervical Pap test among HIV seropositive and seronegative women, to assess the effect of HIV infection on that risk, to determine whether long term follow-up might identify women with initially undiagnosed CIN3 or worse, and to assess the impact of risk factors including age, smoking, and HIV status on long-term risk for CIN3 or worse. Because CIN2 is the threshold for treatment, we did subsidiary analyses incorporating that endpoint.

Material and Methods

The Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) is an ongoing U.S. multicenter cohort study health outcomes among HIV seropositive women. The study also enrolled at-risk HIV seronegative comparison women who were frequency matched for demographic and key risk factors, including age, race/ethnicity, level of education, injection drug use since 1978, and total number of sexual partners since 1980. Enrollment began October 1, 1994 at 6 study consortia and over time enrolled 4,068 women, including those enrolled during an expansion from 2001-2002 (15, 16) and 2011-2012.After local human subjects committees’ review and approval, all participants gave written informed consent for study. Follow up continues, but this analysis includes information obtained between October 1, 1994 and May 30, 2012.

According to study-wide protocol, single-slide conventional Pap smears were obtained every six months using a spatula and brush. Pap tests were interpreted centrally at Qiagen (New York, NY,). All Pap smears were screened by two cytotechnologists blinded to HIV status, with 10% of all negative smears and all abnormal smears reviewed by a cytopathologist. Results were reported according to the 1991 Bethesda system for classification of cervicovaginal cytology and were classified as negative for squamous abnormality, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL), and cancer (17). Results reported as atypical squamous cells, cannot exclude HSIL (ASC-H) were also included and classified with ASCUS cytology. Results of HPV testing were not available to clinicians, and to maximize ascertainment of cervical disease, study protocol required referral for colposcopy for squamous abnormalities of any grade, though decisions on biopsy and treatment were individualized. Biopsy results were interpreted at local sites and categorized as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 1, 2, or 3, adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), or cancer. Koilocytosis and other condylomatous changes were categorized with CIN1. Unspecified high grade dysplasia was classified with CIN3. For analysis, CIN3 or worse included CIN3, AIS, and cancer. CIN2 or worse included these abnormalities and CIN2.

All WIHS enrollees with at least one abnormal Pap test result during study were eligible for the study. Among these eligible women, exclusion criteria included hysterectomy, CIN3 or worse prior to first abnormal Pap result, or a first abnormal Pap result of cancer. In addition, women who HIV seroconverted during follow-up after first abnormal Pap result and those with CIN of indeterminant grade found in follow-up were excluded given their limited number. Finally, to afford the opportunity for colposcopy and diagnosis, women without colposcopic biopsy were excluded if they did not complete at least 12 months of follow-up after an abnormal Pap result; women who had at least 12 months of follow-up but no biopsy were included.

The primary outcome of interest for this study was biopsy-confirmed CIN3 or worse, while CIN2 or worse was explored as a secondary outcome. Demographic and medical characteristics of HIV seropositive and seronegative women ever having an abnormal Pap test were described, including the proportion with various Pap test abnormalities. The proportion of women with follow-up colposcopy was described in order to estimate the impact of colposcopy noncompliance on potentially missed CIN2 or worse.

Differences between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in demographic and clinical characteristics were determined using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Cumulative incidence curves were generated using Kaplan Meier methods. For each grade of squamous Pap abnormality (ASCUS, LSIL, and HSIL), four curves were displayed on a single chart: curves of the cumulative proportion of HIV-positive and HIV-negative women ever diagnosed with CIN2 or worse, and with CIN3 or worse over follow-up times extending to 10 years. Women with multiple grades of Pap abnormality contributed follow-up time after the first abnormality of each grade. Women were allowed to contribute to multiple charts, which included follow-up after the earliest grade-specific abnormality in a hierarchical fashion. Thus, a woman with first ASCUS at t0, first LSIL at t1, and first HSIL at t2 and CIN3 or worse at t3 contributed to all charts. However, a woman with HSIL at t0 would not contribute to charts for ASCUS or LSIL, since the earlier HSIL should have prompted intervention. A chart for ASC-H was not developed, as ASC-H became a separate reportable category only in 2001. Differences by HIV status in the grade-specific cumulative incidence of CIN3 or worse and CIN2 or worse were assessed using a log rank test.

Risk factors for CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse over up to 10-years of follow-up were evaluated using Cox Proportional hazard models using only variables at the time of the first abnormal Pap. Models included factors shown in prior studies to be correlates of HPV infection, abnormal Pap, and prevalent CIN, including, HIV status, current CD4 stratum (<200, 200-349, 350-500, >500), and current tobacco use at first abnormal Pap. Sensitivity analyses were performed removing women with cervical treatment to evaluate whether their inclusion modified the study results.

All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 statistical software (Copyright 2002-2008, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined at the α=0.05 level.

Results

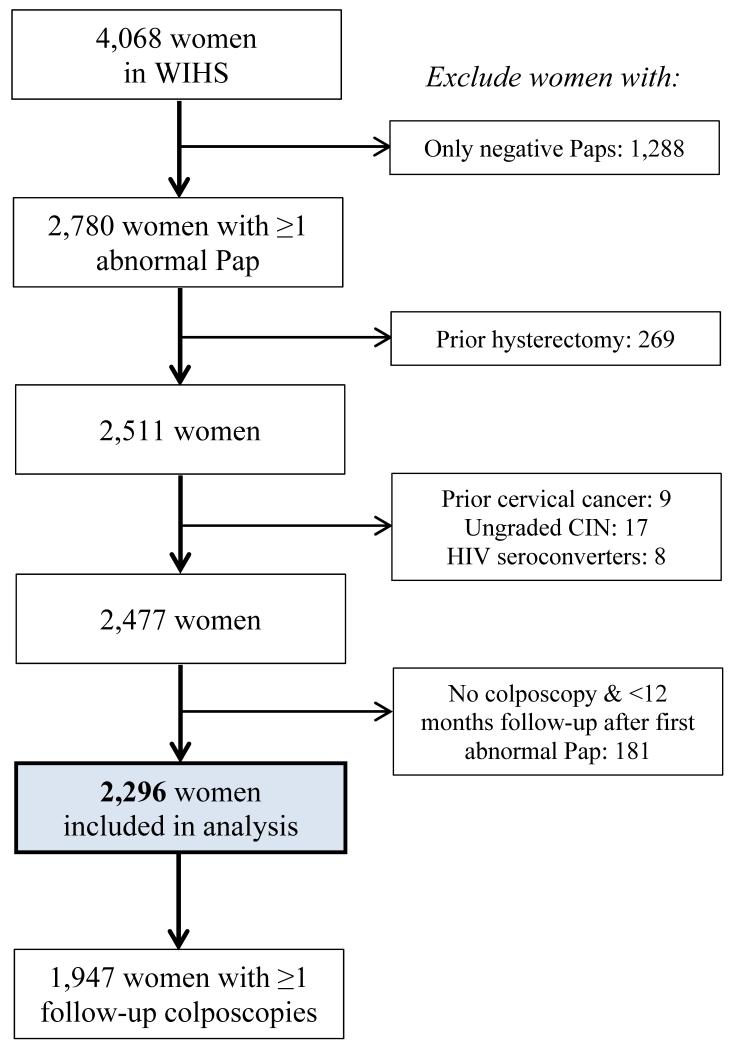

Of the 4068 women enrolled in WIHS (3030 HIV seropositive, 1015 seronegative, and 23 seroconverters), this study was limited to the 2296 (56%) women (1824 HIV seropositive and 472 seronegative) who had an abnormal Pap during follow-up and had colposcopy or at least twelve subsequent months of follow-up, and did not meet any of the other exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Of the eligible women, 923 (40%) had no prior normal Pap test result during study. Of those with an initial normal Pap result, the median time to first abnormal Pap test was 28 months (Interquartile range (IQR) 12, 65 months). Median time between last normal Pap and first abnormal Pap was six months (IQR 5.5,6.7 months).

Figure 1.

(see attachment). Application of inclusion and exclusion criteria to define final study population.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the population at the time of initial abnormal WIHS cytology. HIV seropositive women were more likely than seronegative women to be older, to have fewer lifetime and recent sexual partners, to have LSIL rather than ASCUS as their initial cytologic abnormality, and to have obtained a follow-up colposcopy. Among HIV seropositive women, the first cytologic abnormality was ASCUS in 1305 (72%, including 13 with ASC-H), LSIL in 475 (26%), and HSIL in 44 (2%). Among HIV seronegative women, ASCUS was found in 413 (88%, including 7 with ASC-H), LSIL in 51 (11%), and HSIL in 8 (2%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 2296 women with abnormal cytology.

| Characteristics at time of first abnormal Pap unless otherwise indicated |

% (N) |

p-value HIV+ vs. HIV− |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | HIV-negative | HIV-positive | ||

|

| ||||

| N=2296 | N=472 | N=1824 | ||

|

| ||||

| Age in years: median [IQR] | 36 [30, 42] | 33 [26, 40] | 37 [31, 42] | <0.001 |

| Race, %(n) | 0.70 | |||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 14% (324) | 13% (60) | 14% (264) | |

| White, Hispanic | 8% (184) | 9% (41) | 8% (143) | |

| Black, Non-Hispanic | 56% (1286) | 57% (267) | 56% (1019) | |

| Black, Hispanic | 3% (59) | 3% (16) | 2% (43) | |

| Other Race | 19% (442) | 19% (88) | 19% (354) | |

| Smoking Status | 0.88 | |||

| Current | 51% (1178) | 52% (246) | 51% (932) | |

| Former | 17% (387) | 16% (76) | 17% (311) | |

| Education at baseline | 0.58 | |||

| < high school | 38% (866) | 36% (169) | 38% (697) | |

| high school | 31% (701) | 31% (145) | 31% (556) | |

| > high school | 32%(722) | 33% (156) | 31% (566) | |

| Cumulative number of sexual partners at study baseline |

0.007 | |||

| 0-4 | 38% (869) | 32% (151) | 40% (718) | |

| 5-10 | 28% (634) | 29% (136) | 27% (498) | |

| 11-100 | 27% (613) | 32% (151) | 25% (462) | |

| >100 | 7% (171) | 7% (33) | 8% (138) | |

| Number of sexual partners in 6 months prior to 1st abnormal Pap |

<0.001 | |||

| none | 22% (499) | 11% (51) | 25% (448) | |

| 1-2 | 70% (1603) | 75% (353) | 69% (1250) | |

| >2 | 8% (182) | 14% (68) | 6% (114) | |

| 1st abnormal PAP result | <0.001 | |||

| ASCUS | 75% (1718) | 88% (413) | 72% (1305) | |

| LSIL | 23% (526) | 11% (51) | 26% (475) | |

| HSIL | 2% (52) | 2% (8) | 2% (44) | |

| Colposcopy at any time after abnormal Pap |

85% (1947) | 80% (376) | 86% (1571) | <0.001 |

| CIN3 or worse in follow-up | 8% (163/1947) | 6% (22/376) | 9% (141/1571) | |

| CIN2 or worse in follow-up | 19%(371/1947) | 11% (42/376) | 21%(329/1571) | |

| Among HIV-positive only: | ||||

| CD4 cell count: median [IQR] | 349 [199, 526] | |||

| HIV viral RNA load, copies/mL | 8900 | |||

| : median [IQR] | [360,56000] | |||

| Post HAART initiation | 36% (659) | |||

| Ever AIDS | 31% (562) | |||

Missing data: race, n=1; smoking status, n=1; education, n=7; sexual partners at baseline, n=9; sexual partners in last six months, n=12; CD4, n=49; HIV viral RNA load, n=50.

At time of first abnormal Pap unless otherwise indicated. Numbers in each category may not sum to column total because of missing data.

By chi-square test for independence for categorical variables and Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for continuous variables.

Continuous variables are presented as median [interquartile range], categorical variables as n (%)

Among HIV seropositive women only.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or adenocarcinoma in situ or invasive cancer

CIN3 or worse or CIN2

Of 2,296 women with abnormal cytology, 1,947 (85%) subsequently presented for colposcopy at some time during follow-up. Recommended colposcopic follow-up was never completed for 253 (14%) HIV seropositive and 96 (20%) seronegative women. The median follow-up time after first abnormal cytology was 3.0 (IQR 0.6, 7.7) years among 1571 HIV seropositive women and 4.5 (IQR 1.0, 9.4) years among 376 seronegative women (P < 0.001). At the time of their first abnormal Pap test, women who had colposcopy were younger (median age 36 vs 37 years for noncompliant women, P < 0.001) and more often HIV seropositive (81% vs 72%, P < 0.001) than noncompliant women. In analysis of HIV-positive women, those who had colposcopy also had higher HIV RNA levels (9700 vs 4400, P < 0.0001). Among HIV seropositive women, compliance with colposcopy did not differ by use of antiretroviral therapy, CD4 count, diagnosis of AIDS, race/ethnicity, or cytology grade.

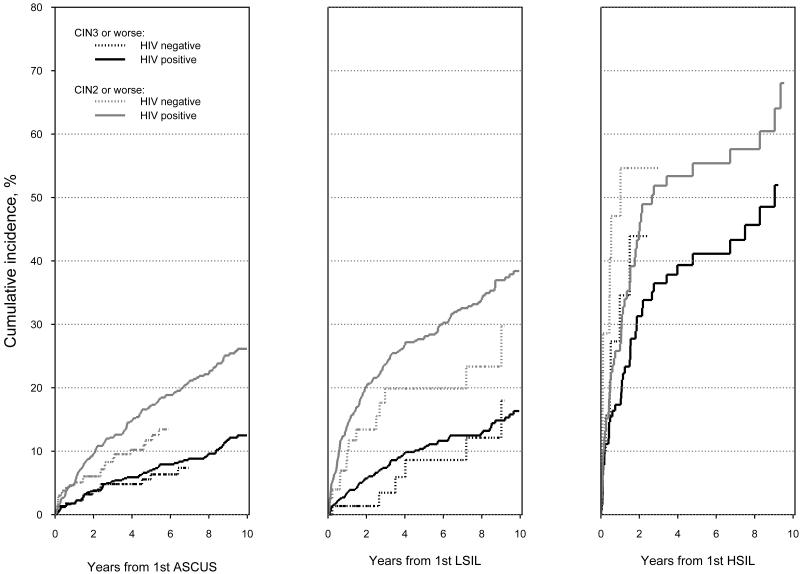

Colposcopy results were known for 1571 (86%) HIV seropositive women, of whom 329 (21%) had CIN2 or worse and 141 (9%) had CIN3 or worse. Colposcopy results were known for 376 (80%) seronegative women, with CIN2 or worse in 42 (11%) and CIN3 or worse in 22 (6%). Table 2 shows the median time from first grade-specific abnormal Pap to an abnormal biopsy or loss to follow-up and the frequency of and cumulative risk for high grade histology in HIV seropositive and seronegative women. Time to a high grade histologic abnormality, both CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse, is summarized in Figure 2. Most women with ASCUS and LSIL did not develop CIN2 or worse, despite long follow-up. For example, only 11% of HIV seropositive women with LSIL developed CIN3 or worse after 5 years. Risk for CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse was consistently higher for HIV seropositive than seronegative women but only the risk of CIN2 or worse among women after an ASCUS result reached significance (17.2% vs11.7%, P = 0.007). Cumulative risk for both CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse after HSIL was high, regardless of HIV serostatus.

Table 2.

Cumulative risk of CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse after an initial abnormal Pap test result.

| Abnormal PAP Result |

CIN3 or worse | CIN2 or worse | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| N=1947 | N=1947 | ||||

| HIV− | HIV+ | HIV− | HIV+ | ||

| ASCUS | N | 329 | 1120 | 329 | 1120 |

| Follow-up from first ASCUS Pap: median | 2.6 [0.5, 7.1] | 4.1 [0.8, 8.7] | 2.5 [0.4, 6.7] | 3.4 [0.7, 8.1] | |

| number of years [IQR] | |||||

| Number of events during follow-up (%) | 15 (5%) | 86 (8%) | 28 (9%) | 189 (17%) | |

| p-value for Log-Rank test | p=0.27 | p=0.007 | |||

| 1 year cumulative incidence | 1.8% | 1.8% | 4.6% | 5.0% | |

| 5 year cumulative incidence | 6.4% | 7.0% | 11.7% | 17.2% | |

|

| |||||

| LSIL | N | 80 | 860 | 79 | 842 |

| Follow-up from first LSIL Pap: median | 3.5 [1.4, | 3.6 [1.0, 8.5] | 2.7 [0.9, 7.5] | 2.5 [0.6, 7.5] | |

| number of years [IQR] | 8.1] | ||||

| Number of events during follow-up (%) | 6 (8%) | 88 (10%) | 14 (18%) | 229 (27%) | |

| p-value for Log-Rank test | p=0.53 | p=0.12 | |||

| 1 year cumulative incidence | 1.4% | 3.5% | 10.1% | 14.0% | |

| 5 year cumulative incidence | 8.6% | 10.6% | 19.9% | 27.7% | |

|

| |||||

| HSIL | N | 21 | 132 | 18 | 110 |

| Follow-up from first HSIL Pap: median | 0.8 [0.2, | 1.5 [0.5, 5.1] | 0.5 [0.1, 1.4] | 1.2 [0.3, 4.0] | |

| number of years [IQR] | 3.3] | ||||

| Number of events during follow-up (%) | 8 (38%) | 45 (34%) | 10 (56%) | 52 (47%) | |

| p-value for Log-Rank test | p=0.29 | p=0.14 | |||

| 1 year cumulative incidence | 34.6% | 18.3% | 7.1% | 27.0% | |

| 5 year cumulative incidence | 62.6% | 41.1% | 77.3% | 55.4% | |

Fig. 2.

(see attached pdf).Risk of CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse among HIV seropositive and seronegative women during follow-up after abnormal cytology. P > 0.10 for all comparisons of HIV seropositive women except for CIN2 or worse results after ASCUS (P = 0.007).

Direct comparison of risk for CIN3 or worse and CIN2 or worse is problematic because of differential distribution of cervical cancer risk factors by serostatus. To account for this, multivariable analyses explored risk factors for colposcopy-confirmed CIN2 or worse among women with ASCUS and LSIL. Women with ASC-H and HSIL were not analyzed because the high risk for CIN3+ associated with these Pap results precludes conservative management of women without risk factors (Figure 2). Risk for CIN2 or worse was increased among women who were HIV seropositive and younger, current smokers, women with only a high school education or less, and women with LSIL compared to ASCUS (Table 3). The increased risk for CIN2 or worse among HIV seropositive women in this analysis was only 1.66. Risk factors for CIN3 or worse appeared similar, but not statistically significant, given the smaller number of cases of CIN3 or worse (Table 3), except that age was not a risk factor for CIN3+.

Table 3.

Risk factors for CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse among 1459 HIV seropositive and 360 HIV seronegative women with ASCUS or LSIL Pap results and available covariate data.

| Characteristics at time of first | CIN3 or worse | CIN2 or worse |

|---|---|---|

| abnormal Pap | N=1819 | N=1819 |

|

| ||

| Events=133 | Events=328 | |

| HR (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||

| HIV negative | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| HIV positive | 1.33 (0.79, 2.34) | 1.66 (1.15, 2.45) |

| CD4 cells/cmma | ||

| <200 | 1.34 (0.84, 2.08) | 1.30 (0.97, 1.73) |

| 200-350 | 0.81 (0.50, 1.27) | 1.05 (0.79, 1.38) |

| ≥350 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Ever AIDSb | 0.80 (0.51, 1.22) | 0.84 (0.64, 1.10) |

| First abnormal Pap result | ||

| ASCUSc | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| LSILd | 1.18 (0.79, 1.74) | 1.81 (1.43, 2.28) |

| Age, per 5 years | 1.00 (0.89, 1.12) | 0.92 (0.85, 0.98) |

| Smoking Status | ||

| Never | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Current | 1.57 (1.04, 2.43) | 1.45 (1.12, 1.90) |

| Former | 1.02 (0.54, 1.86) | 1.07 (0.73, 1.54) |

| Education at study baseline | ||

| > high school | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| ≤ high school | 1.34 (0.90, 2.06) | 1.38 (1.07, 1.81) |

Among HIV seropositive women only

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

To consider the possible impact cervical disease treatment might have had on our results, we performed a set of parallel analyses removing all women with treatment either before or during follow-up from each of the models shown in Table 2 with an outcome of CIN3 or worse. This included 100 women (89 HIV seropositive, 11 seronegative) from the ASCUS analysis, 131 women (123 HIV seropositive, 8 seronegative) from the LSIL analysis, and 30 women (24 HIV seropositive, 6 seronegative) from the HSIL analysis. In this analysis excluding treated women, five-year cumulative incidence of CIN3 or worse after ASCUS cytology was 7.5% among HIV seropositive women and 5.9% among seronegative women. Similar results after LSIL were 11.7% and 6.7% and after HSIL were 49.7% and 76.0%. All results were similar to those from analyses including treated women and none of the cumulative incidences differed significantly by serostatus. Similar sensitivity analyses with CIN2 or worse as the outcome as showed no differences when treated women were excluded.

Discussion

HIV seropositive women face a higher risk for abnormal Pap test results than seronegative women, and their Pap tests are more severely abnormal (1, 2). However, the results of this study show that once an HIV seropositive woman has developed a Pap abnormality, her risk for CIN3 or worse is only marginally greater that of an HIV seronegative woman. Less than 40% of HIV seropositive women with ASCUS and LSIL in our study developed CIN2 or worse over 10 years, with CIN3 or worse in less than 20%. HIV seropositive women with ASCUS and LSIL do not appear to progress rapidly to CIN3 or worse. Although multivariable analysis showed that HIV infection was a risk factor for CIN2 or worse during follow-up, it was not a significant risk factor for CIN3 or worse, suggesting that HIV infection may increase CIN2 disproportionately. These results provide further support to the concept that women with HIV and abnormal cytology can be followed according to algorithms developed for U.S. women in general (18).

CIN2 is the treatment threshold for cervical disease. Immediate loop excision after colposcopic visualization to exclude obvious cancer and guide loop selection is an option for all women with HSIL Pap results (18). For women with HIV, immediate outpatient excision has high yield, low risk for overtreatment, and few short term complications (19). Observation for regression may be an option for young women concerned about the possible contribution of CIN treatment to risk for later preterm delivery. However, as shown in Fig. 2 risk for CIN2 or worse reached almost 60% within five years of a first HSIL Pap result for HIV seropositive women. Excisional treatment of all women with HSIL cytology without biopsy confirmation of CIN2 or worse may minimize risks of colposcopy noncompliance, especially among HIV seropositive women. Some factors limit the conclusions that can be drawn from this study. Central pathology of all biopsy specimens and image review of all colposcopies was not undertaken; while doing so might have changed results, the multisite nature of WIHS pathology interpretation increases the generalizability of our results. Women who did not obtain colposcopy more often had risk factors for CIN and may have had more severe disease than those who did; true rates of CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse may be higher than we report. The number of HIV seronegative women was relatively small because of their lower risk for abnormal cytology, and our failure to observe a difference in risk for CIN3 or worse over time between HIV seropositive and seronegative women with similar Pap results may reflect lack of statistical power, although this study included up to 10 years of follow-up and a clinically meaningful difference is unlikely. Larger studies with longer follow-up are unlikely to be undertaken. However, many HIV seronegative women in WIHS have high risk behaviors, and their risk for CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse after cytologic abnormality may be higher than in lower risk populations. Our results include data collected during a study that has been ongoing for almost two decades, and results may be different for contemporary women. Specifically, current risk for CIN2 or worse and CIN3 or worse after ASCUS cytology may be lower, since a finding of atypical squamous cells on cytology was subclassified in 2001 into ASC-US and ASC-H. Risk also may be lower if current antiretroviral therapy slows or reverses progression of cervical lesions. Recent studies of the sensitivity of colposcopy suggest that it may be insensitive for the detection of CIN3 or worse unless multiple biopsies are obtained (13, 14). For many women in WIHS who require repeated colposcopy, multiple biopsies across multiple colposcopy visits were not feasible. We may underestimate risk for CIN3 or worse, although missed clinically important lesions should have presented clinically as symptomatic cancers during relatively long follow-up. Finally, we may underestimate long term risk for CIN3 or worse in HIV seropositive women if they were disproportionately treated for CIN2 because of their higher risk for cancer and treatment prevented progression to CIN3 or worse.

Our results are broadly similar to those of others, although few longitudinal studies of HIV seropositive women from developed countries have been reported. Boardman and colleagues found a similar prevalence of CIN2 or worse at colposcopy among HIV seropositive and seronegative women with ASCUS or LSIL cytology, though they did not have follow-up results (20). Suwakanta and associates found that HIV seropositive women had a higher risk of CIN2 or worse than seronegative Thai women, but more than half of the women in their study had HSIL and cancer on Pap, and their results cannot be generalized to women from developed countries with more available screening (21).

Risk for cervical disease after abnormal cytology were recently published from a large cohort of women in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) health plan presumably not infected with HIV (22). Five-year risks for CIN2 or worse in the KPNC cohort were 7% after ASCUS, 16% after LSIL, and 69% after HSIL. For women in the 30-34-year-old cohort in the KPNC cohort, the age group near the median among our HIV seronegative women, five-year risks of CIN2+ were 10.7% after ASCUS and 17.2% after LSIL. Comparable results among HIV seronegative women in our study group were 12% after ASCUS and 20% after LSIL; numbers of HIV seronegative women with HSIL followed for five years were too small to calculate stable risk estimates. Thus, risk for high-grade disease in our HIV-seronegative women appears to be close to but marginally higher than risk in the KPNC cohort, consistent with recruitment of women at increased risk for HIV in our cohort and with age-based differences in risk.

We did not identify a plateau in risk for CIN2 or worse or CIN3 or worse for women with abnormal Pap results. For women with HSIL, disease detection was rapid soon after cytologic abnormality but continued to increase across time. In contrast, for women with ASCUS and LSIL, disease detection often followed a considerable lag period. HIV seropositive women with abnormal Pap results merit scrupulous surveillance. Women may require repeated colposcopy for recurrent abnormal cytology. To minimize the risk of loss to follow-up, women with abnormal Pap results should be educated to expect that cancer prevention may require repeated visits over many years.

Novelty/impact statement.

We present the longest reported follow-up to date of a large cohort of HIV seropositive and comparison HIV seronegative women with abnormal Paps. HIV seropositive women with atypical and low grade Paps face a marginally higher risk for biopsy confirmed high grade cervical disease compared to HIV seronegative women, but risk does not plateau. Regardless of HIV serostatus, high grade Pap results carry a grave risk for biopsy-confirmed cervical disease and may merit immediate treatment.

Acknowledgement

Clinical data and specimens in this manuscript were collected by the Women’s Interagency HIV Study (WIHS) Collaborative Study Group with centers (Principal Investigators) at New York City/Bronx Consortium (Kathryn Anastos); Brooklyn, NY (Howard Minkoff); Washington DC Metropolitan Consortium (Mary Young); The Connie Wofsy Study Consortium of Northern California (Ruth Greenblatt); Los Angeles County/Southern California Consortium (Alexandra Levine); Chicago Consortium (Mardge Cohen); Data Coordinating Center (Stephen Gange). The WIHS is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1-AI-35004, UO1-AI-31834, UO1-AI-34994, UO1-AI-34989, UO1-AI-34993, and UO1-AI-42590) and by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (UO1-HD-32632). The study is co-funded by the National Cancer Institute, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Funding is also provided by the National Center for Research Resources (UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR024131). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- CIN

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- WIHS

Women’s Interagency HIV Study

- ASCUS

atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance

- LSIL

low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- HSIL

high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- ASC-H

atypical squamous cells cannot exclude high grade

- AIS

adenocarcinoma in situ

- IQR

interquartile range

Contributor Information

L. Stewart Massad, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO

Christopher B. Pierce, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Howard Minkoff, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY

D. Heather Watts, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD

Teresa M. Darragh, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Lorraine Sanchez-Keeland, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Rodney L. Wright, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY

Christine Colie, Georgetown University, Washington, DC

Gypsyamber D’Souza, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

References

- 1.).Massad LS, Riester KA, Anastos KM, Fruchter RG, Palefsky JM, Burk RD, Burns D, Greenblatt RM, Muderspach LI, Miotti P. Prevalence and predictors of squamous cell abnormalities in Papanicolaou smears from women infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1. J Acquire Immun Deficiency Syndromes Hum Retrovirol. 1999;21:33–41. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.).Massad LS, Seaberg EC, Wright RL, Darragh T, Lee YC, Colie C, Burk R, Strickler HD, Watts DH. Squamous cervical lesions in women with Human Immunodeficiency Virus:long-term follow up. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:1388–93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181744619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.).Massad LS, Ahdieh L, Benning L, Minkoff H, Greeblatt RM, Watts H, Miotti P, Anastos K, Moxley M, Muderspach LI, Melnick S. Evolution of cervical abnormalities among women with HIV-1: Evidence from surveillance cytology in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. J Acquir Immunodef Human Retrovirol. 2001;27:432–42. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200108150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.).Massad LS, Schneider M, Watts H, Darragh T, Abulafia O, Salzer E, Muderspach LI, Sidawy M, Melnick S. Correlating Papanicolaou smears, colposcopic impression and biopsy. Results from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. J Lower Genital Tract Dis. 2001;5:212–8. 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.).Massad LS, Evans CT, Strickler HD, Burk RD, Watts DH, Cashin L, Darragh T, Gange S, Lee YC, Moxley M, Levine A, Passaro DJ. Outcome after negative colposcopy among human immunodeficiency virus-infected women with borderlinecytologic abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:525–32. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172429.45130.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.).Massad LS, Seaberg EC, Watts DH, Hessol NA, Melnick S, Bitterman P, Anastos K, Silver S, Levine AM, Minkoff H. Low incidence of invasive cervical cancer among HIV infected US women in a prevention program. AIDS. 2004;18:109–13. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200401020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.).Palefsky JM, Minkoff H, Kalish LA, Levine A, Sacks HS, Garcia P, Young M, Melnick S, Miotti P, Burk R. Cervicovaginal human papillomavirus infection in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 (HIV)-positive and high-risk HIV-negative women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:226–36. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.).Harris TG, Burk RD, Palefsky JM, Massad LS, Bang JY, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Hall CB, Bacon MC, Levine AM, Watts DH, Silverberg MJ, et al. Incidence of cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions associated with HIV serostatus, CD4 cell counts, and human papillomavirus test results. JAMA. 2005;293:1471–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.12.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.).Strickler HD, Burk RD, Fazzari M, Anastos K, Minkoff H, Massad LS, Hall C, Bacon M, Levine AM, Watts DH, Silverberg MJ, Xue X, et al. Natural history and possible reactivation of human papillomavirus in human immunodeficiency virus positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:577–86. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.).Abraham AG, Strickler HD, Jing Y, Gange SJ, Sterling TR, Silverberg M, Saag M, Rourke S, Rachlis A, Napravnik S, Moore RD, Klein M, et al. Invasive cervical cancer risk among HIV-infected women: A North American multi-cohort collaboration prospective study. JAIDS. 2013;62:405–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828177d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.).Massad LS, Seaberg EC, Watts DH, Minkoff H, Levine AM, Henry D, Colie C, Darragh TM, Hessol NA. Long-term incidence of cervical cancer in women with HIV. Cancer. 2009;115:524–30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.).Cejtin H, Komanoff E, Massad LS, Korn A, Schmidt JB, Eisenberger-Matityahu D, Stier E. Adherence to colposcopy among women with HIV infection. J Acquir Immun Deficiency Syndromes Hum Retrovirol. 1999;22:247–52. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199911010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.).Solomon D, Schiffman M, Tarone R, ALTS Study group Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: baseline results from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:293–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.).Massad LS, Jeronimo J, Katki HA, Schiffman M. The accuracy of colposcopic grading for detection of high grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Lower Genital Tract Dis. 2009;13:137–144. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e31819308d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.).Barkan SE, Melnick SL, Martin-Preston S, Weber K, Kalish LA, Miotti P, Young M, Breenblatt R, Sacks H, Feldman J. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study. Epidemiol. 1998;9:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.).Bacon M, von Wyl V, Alden C, Sharp G, Robison E, Hessol N, Gange S, Barranday Y, Holman S, Weber K, Young MA. The Women’s Interagency HIV Study:an observational cohort brings clinical sciences to the bench. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1013. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.9.1013-1019.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.).Kurman RJ, Solomon D. The Bethesda System for reporting cervical/vaginal cytologic diagnoses. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.).Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, Katki HA, Kinney WK, Schiffman M, Solomon D, Wentzensen N, Lawson HW, 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:829–46. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182883a34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.).Adam Y, van Gelderen CJ, Newell K. ‘Look and Lletz’--a Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital experience. S Afr Med J. 2008;98:119–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.).Boardman LA, Cotter K, Raker C, Cu-Uvin S. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in humanimmunodeficiency virus-infected women with mildly abnormal cervical cytology. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:238–43. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000320309.34046.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.).Suwankanta N, Kietpeerakool C, Srisomboon J, Khunamornpong S, Siriaunkgul S. Underlying histopathology of HIV-infected women with squamous cell abnormalities on cervical cytology. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2008;9:441–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.).Katki HA, Schiffman M, Castle PE, Fetterman B, Poitras NE, Lorey T, Cheung LC, Raine-Bennett T, Gage JC, Kinney WK. Benchmarking CIN3+ risk as the basis for incorporating HPV and Pap cotesting into cervical screening and management guidelines. J Lower Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17:S28–S35. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318285423c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]