Abstract

How necrotic areas develop in tumors is incompletely understood but can impact progression. Recent findings suggest that formation of vascular microthrombi contributes to tumor necrosis, prompting investigation of coagulation cascades. Here we report that loss of tumor suppressor p14ARF can contribute to activating the clotting cascade in glioblastoma (GBM). p14ARF transcriptionally upregulated TFPI2, a Kunitz-type serine protease in the tissue factor pathway that inhibits the initiation of thrombosis reactions. p14ARF activation in tumor cells delayed their ability to activate plasma clotting. Mechanistically, p14ARF activated the TFPI2 promoter in a p53-independent manner that relied upon c-JUN, SP1 and JNK activity. Taken together, our results identify the critical signaling pathways activated by p14ARF to prevent vascular microthrombosis triggered by glioma cells. Stimulation of this pathway might be used as a therapeutic strategy to reduce aggressive phenotypes associated with necrotic tumors including glioblastoma.

Introduction

High-grade gliomas represent the most common primary central nervous system tumors in adults and are associated with poor survival. The serious therapeutic challenge posed by these tumors, particularly glioblastoma multiforme (GBM; WHO grade IV), is due in part to their complex biology (1). In GBM, complex heterotypic interactions between tumor and stromal vascular cells lead to the formation of glomeruloid microvascular proliferations in close proximity to micronecrotic regions surrounded by pseudopalisading tumor cells (2). These structures are pathognomonic to GBM and are associated with poor patient prognosis. Understanding the mechanisms underlying their formation is important as it may lead to new therapeutic approaches (3).

It is well known that a major driver of vascular proliferation in GBM is the tumor cell secretion of VEGF stimulated by microenvironmental hypoxia (4–7). One aspect that has not been extensively studied, however, is the consequence of plasma leakage in the tumor following VEGF induced vascular permeability. GBM cells have a strong ability to activate the coagulation system by expressing Tissue Factor (TF) (8), a unique cell-associated receptor for coagulation factor VIIa, a serine protease that can initiate blood coagulation (9). Formation of a blood clot in tumor vessels is expected to render the surrounding region hypoxic and ischemic and causes micronecrosis. In response to this micro-environmental stress, tumor cells may migrate away from the obstructed vessels, possibly creating the observed pseudopalisiding cell layer surrounding a micronecrotic region containing remnants of obstructed vessels (2).

Activation of the coagulation cascade is facilitated by genetic events in the tumor. GBMs show overexpression of wild type and truncated constitutively active EGFR genes (10, 11). Activation of the EGFR signaling can upregulate the expression of TF (10), its ligand Factor VII and the protease-activated receptors (PAR-1 and PAR-2) (12). These factors come in contact with coagulation factors that have leaked out from the fenestrated vessels, and participate at the initiation step of coagulation and consequently clot formation. Activation of the PI-3 kinase pathway through PTEN gene loss (13), high activity of the nuclear factor NF-kappaB (14), and the development of hypoxia within the tumor can also contribute to the coagulopathy by increasing TF expression (13). Here, we were interested to know whether additional genetic events might facilitate thrombus formation through the loss of negative regulators of coagulation.

One of the most potent factors able to prevent the initiation of coagulation reactions is Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor-2 (TFPI2). Human TFPI2, also known as placental protein 5 (PP5) inhibits several coagulation factors including Factor VIIa, Tissue Factor, Factor Xa and Thrombin (15). TFPI2 is expressed in most human tissues, but tumors arising from these tissues display either reduced or undetectable expression. Several highly aggressive tumors lose TFPI2 expression due to gene silencing associated with promoter hypermethylation (16–18).

A frequent genetic change that occurs in GBM is loss of the CDKN2A locus. This locus encodes the tumor suppressor P14ARF (p19Arf in mice) (19–24), and its loss predisposes to diverse tumor types, including GBM (21, 23–25). P14ARF binds to and inactivates MDM2, a negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor (20), thereby mediating cell cycle arrest or inducing apoptosis (22, 23, 26). P14ARF has also additional p53-independent tumor suppressor activities, including the ability to suppress tumor angiogenesis (24, 25, 27, 28).

Here we hypothesized that the loss of P14ARF may facilitate the initiation of the coagulation cascade in tumors by reducing the expression of negative regulators. A link between the activation of the coagulation system and the loss of P14ARF activity in cancer is currently unknown. We showed that restoring P14ARF gene expression in tumor cells inhibits the clotting process. Mechanistically, we found that in human GBM, P14ARF upregulates the expression of the Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor 2 (TFPI2) in a P53-independent manner. This upregulation is mediated by the coordinated action of SP1 and AP1 on the TFPI2 gene promoter following P14ARF activation, establishing novel downstream signaling pathways for this tumor suppressor.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and transfections

Human glioblastoma cell lines LN229 (deleted for the P14ARF gene) and LN-Z308 (devoid of endogenous p53 protein) (29) were used to generate clones with doxycycline-inducible expression of HA-tagged P14ARF cDNA. Clones LN229-L16 (30) and LNZ308-C16 (31) expressing stably the reverse tetracycline-controlled transactivator (rtTA) were engineered to express dox inducible P14ARF (A5 and C19 respectively) (28). The A5 and C19 cell lines were genetically authenticated by Genetica DNA Laboratories (Burlington, NC). The E6E7/hTert/Ras transformed human astrocytes were previously described (32).

Glioma cells were routinely cultured in DMEM containing 5% tetracycline-free calf serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. All transfections with plasmids were performed using Geneporter as recommended (Gene Therapy Systems, San Diego, CA). For gene silencing experiments, cells were transfected with 35 nM final concentration of TFPI2, SP1, MDM2, c-JUN siRNAs (Ambion) or negative control siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) in serum free medium for 5–24hrs. To induce P14ARF expression, cells were cultured in medium containing 2% serum and treated with 2ug/ml dox for 48hrs.

Plasma clotting assay

Tumor cells (107) in medium containing 2% serum for 48 hrs were gently rinsed twice with cold PBS, scraped from the dish, and resuspended in 1.0 mL PBS. Two hundred microliters of cell suspension were added to 200 μL of citrated human plasma (Precision Biologic, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia) and then 200 μL of 25 mmol CaCl2 were added to the tube to initiate the clotting process. Clotting time was counted using an automated coagulation timer (Medical Laboratory Automation, Inc, Pleaseantville, NY) and when the liquid formed a semi-solid gel, it triggered the stop of the timer. Plasma clotting times induced by tumor cells were measured in triplicate with all reagents maintained at 37°C. Positive controls for each experiment included Neoplastine (Thromboplastin) clotting reagent (Diagnostica Stago, Parsippany, NJ) in place of tumor cell suspension (clot time = 16–22 seconds).

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell extracts were obtained by lysing cells in 1× Laemmli sample buffer (0.1% 2-Mercaptoethanol, 0.0005% Bromophenol blue, 10% Glycerol, 2% SDS, and 63mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) or RIPA buffer (50mM Tris, pH7.4; 150mM NaCl; 0.5 mM EDTA; 0.5% Sodium Desoxycholate; 0.1% SDS; 1% Triton X100 and 1× mini-complete anti-proteases, Roche) and protein concentrations were determined using the DC protein assay (Bio-Rad). The protein samples (50–100 μg per well) were then boiled for 5 min after adding DTT to a final concentration of 50mM and resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on either 12.5% Tris-HCl gels or 4–20% gradient gels (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) and transferred to NitroBind, pure nitrocellulose membranes (GE Water and Process Technologies). The membranes were immunoblotted using polyclonal rabbit anti-HA or goat anti-p14ARF antibodies to detect p14ARF (1:2,000 dilution, Covance; 1:1000, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), mouse anti-human p53 (clone DO-7; 1:1,000, DAKO), mouse anti-human p21 (Ab-11; 1:500, NeoMarkers), rabbit anti-SP1 (1:500, PEP2), goat anti-β-Actin (1:1,000) and mouse anti-α-Tubulin (1:500) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies); rabbit anti-c-JUN, anti-Phospho S63 and S73 c-JUN, anti-JNK1/2 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technologies), anti-JNK (1:300, Zymed), rabbit anti-TFPI2 (generously provided by Dr. Walter Kisiel, Krakow, Poland) and mouse anti-TFPI2 (B7) (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Immunodetection was performed using the corresponding secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies. Horseradish peroxidase activity was detected using Supersignal West-pico chemiluminescence kit (Pierce, Rockford).

Northern blot analysis

To generate probes specific for each human gene of interest the reverse transcription-PCR amplification was performed. The sequences of the PCR forward (Fwd) and reverse (Rev) primers were as follows: P14ARF-Fw: 5′aaa cca tgg atg gtc cgc agg ttc ttg gtg3′, P14ARF-Rev: 5′agc tgg atc cca tca tca ttg acc tgg tct tct a3′; TFPI2 Fw: 5′cga ggg caa cgc caa caa ttt cta 3, TFPI2 Rev: 5′ttc cgg att cta ctg gca aag cga 3′, c-JUN Fw:5′ acg caa acc tca gca act tca acc-3′, c-JUN Rev: 5′ ttg caa ctg ctg cgt tag cat gac-3′, CDKN1A/P21-Fw: 5′gca gtg tgt cgg gtg aag 3′ and CDKN1A/P21 Rev: 5′ctc agc aag caa cga agt g3′. The annealing temperatures used in PCR reactions were either 60°C or 62°C. Northern blots were generated as previously described (28, 33).

Luciferase reporter assay of TFPI2 promoter activity

Transcription factor binding sites in the TFPI2 gene promoter were identified using Proscan version 7.1 (http://bimas.dcrt.nih.gov/cgi-bin/molbio/proscan). A5 cells were transfected with pGL3- luciferase reporter plasmids driven by the 222bp. promoter of the TFPI2 gene; either wild type (p222-luc), or containing point mutations in the AP1 and SP1 binding sites (p222-mtAP1luc, p222-mtSP1luc and p222-mtAP-SP1luc) (34) using Fugene for 24hrs. Serum was then added to 2% final. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were left untreated or treated with 2 μg/ml of dox for 36 hrs. Cells were lysed and the relative luciferase activities were measured using a Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and a luminometer (Sirius model, Berthold Detection systems, Pforzheim, Germany) and normalized to protein content. All luciferase assays were carried out in triplicates and values represent relative light unit (RLU) of luciferase activity/ug of protein present in whole cell lysate.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation assays

The Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed with a commercial kit (Upstate Biotechnology) using the manufacturer’s protocol with minor adjustments. A5 cells were grown in 150 mm dishes at 3.106 cells/plate in medium with 2% serum +/− dox (2μg/ml) for 48hrs. Subsequently, the cells were fixed for 10 min at 37°C by adding formaldehyde directly to the culture medium to a final concentration of 1%. The cells were washed with cold PBS, lysed for 10 min with 1% SDS, 10 mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, and sonicated 4 times for 10 seconds each on ice (Sonic dismembrator Model 100, Fisher Scientific), and then cell debris were removed by centrifugation. Aliquots were taken to control for DNA input. The remainder lysate was diluted 10 times in 0.01% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1mM EDTA, 10mM Tris HCl, pH 8.0, and 150 mM NaCl, phosphatase/protease inhibitors, pre-cleared with agarose beads/Salmon sperm DNA and incubated overnight (4°C) with 1μg/ml of Acetyl-Histone H3 antibody (Cell Signaling), 1,5 μg/ml of antibodies against c-JUN (N20), SP-1 (PEP2) or with non-specific rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Formaldehyde fixed DNA–protein complexes were pulled down with protein-A conjugated agarose beads and extracted with 1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3. The protein-DNA crosslinking was reversed at 65°C for 5 hrs, and the released proteins were eliminated through digestion with proteinase K (40 μg/ml, 1hr at 45°C) The co-immunoprecipitated genomic DNA was purified using mini columns (Qiagen) and eluted with 10mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0. The primers used for PCR to amplify the TFPI2 promoter encompassing the c-JUN and SP1 binding sites were TFPI2 Fwd (−268 to −244) 5′-AGGAGAAAGTTTGGGAGGCAGGTT-3′, TFPI2 Rev (−42 to −24) 5′-TGGGCAAGGCGTCCGAGAAA-3′. The expected size of the PCR product is 244 bp. c-JUN Fwd 5′-GTG CGG GAG GCA TCT TAA T-3′ and c-JUN Rev, 5′ TTC ACG TGA GGT TAG TTT GGG-3′ primers were used to amplify the region −221 to −16 of the c-JUN promoter (205bp).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student’s t-test (two-tailed). P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

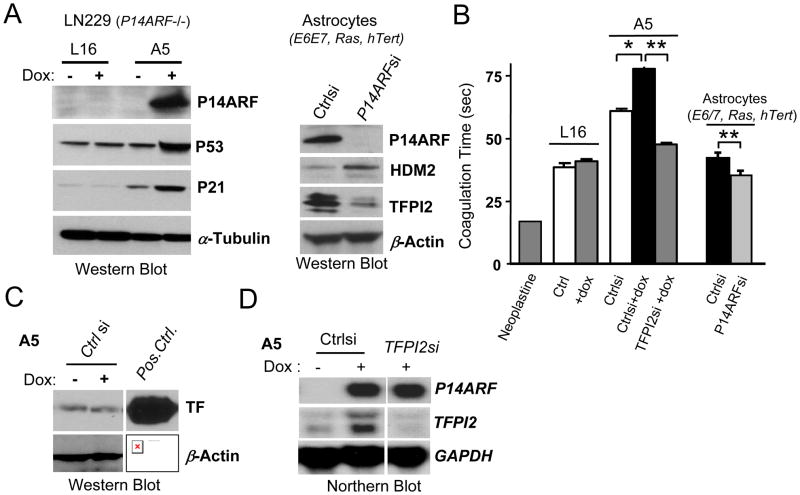

To determine whether P14ARF regulates tumor-induced clot formation, we used two cell systems: one with inducible p14ARF overexpression and the second with silencing of endogenous p14ARF. P14ARF-null human glioma cells (LN229-A5) are conditionally expressing P14ARF under a tet-on system (Fig.1A, left panel) (28). LN229-L16 parental cells (rtTA positive, but not expressing P14ARF) were used as control for the non-specific effects of doxycycline (dox). The induction of p14ARF by dox resulted in p53 stabilization and downstream increase of p21 in A5 cells. To modulate physiological endogenous P14ARF, we used RNA interference in E6/E7 Ras transformed human astrocytes (Fig1A, right panel), which led to an increase in HDM2 stability as expected (35).

Fig 1. P14ARF inhibits plasma clotting by upregulating TFPI2 expression.

(A) Left panel: Western Blot showing the tight regulation of P14ARF induction with doxycycline (dox) in LN229-A5 human glioma cells. The induction of P14ARF increases P53 levels, which in turn increases the expression of the p53 downstream target, p21. The treatment of LN229-L16 cells (P14ARF null) with dox has no effect on P53 or p21 indicating the absence of non-specific effects of dox. Right panel: Western Blot showing the reduction in TFPI2 expression upon P14ARF silencing.

(B) Induction of P14ARF in A5 cells increases the clotting time of pooled normal human plasma, which can be prevented by the silencing of TFPI2 expression. The treatment of L16 with dox has no effect on plasma coagulation time. Neoplastine was used as a positive control of plasma clotting. The unpaired 2-tailed Student’s t-test was used to assess the statistical differences between experimental groups, *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; n=3.

(C) Induction of P14ARF with dox in A5 cells does not affect the expression of Tissue Factor (TF). An extract of U87MG glioma cells cultured in 1% oxygen was used as positive control (Pos.Ctrl.) for TF expression.

(D) Northern Blot showing that the induction of P14ARF expression enhances the transcription of TFPI2 in A5 cells and that the silencing of TFPI2 with specific siRNA decreases its mRNA levels.

α-Tubulin, β-Actin and GAPDH were used as loading controls.

To test whether P14ARF could modulate thrombus formation by glioma cells, we used a plasma coagulation assay. Thromboplastin (Neoplastine) was used as positive control. Doxycycline induction of P14ARF in A5 cells delayed plasma clotting, while it had no effect in parental L16 cells used as controls (Fig.1B). We first examined whether this effect on coagulation might reflect a decrease in TF expression, but found barely detectable levels in A5 cells which were unaffected by P14ARF (Fig 1C). Because TFPI2 is a negative regulator of plasma clotting at its initiation step, we then investigated whether it was induced by P14ARF. Northern blot analysis shows that the induction of P14ARF in A5 cells induced TFPI2 gene transcription (Fig. 1D). Conversely, the specific silencing of TFPI2 in A5 cells (Fig. 1D) was able to accelerate clot formation, thus reversing P14ARF-mediated inhibition (Fig. 1B). The silencing of p14ARF in E6E7/Ras astrocytes led to a significant decrease of TFPI2 expression with a concomitant increase of plasma clotting time. These data provide evidence for the role of P14ARF in the inhibition of plasma coagulation and this control is mediated through transcriptional activation of the production of the anti-coagulant factor TFPI2.

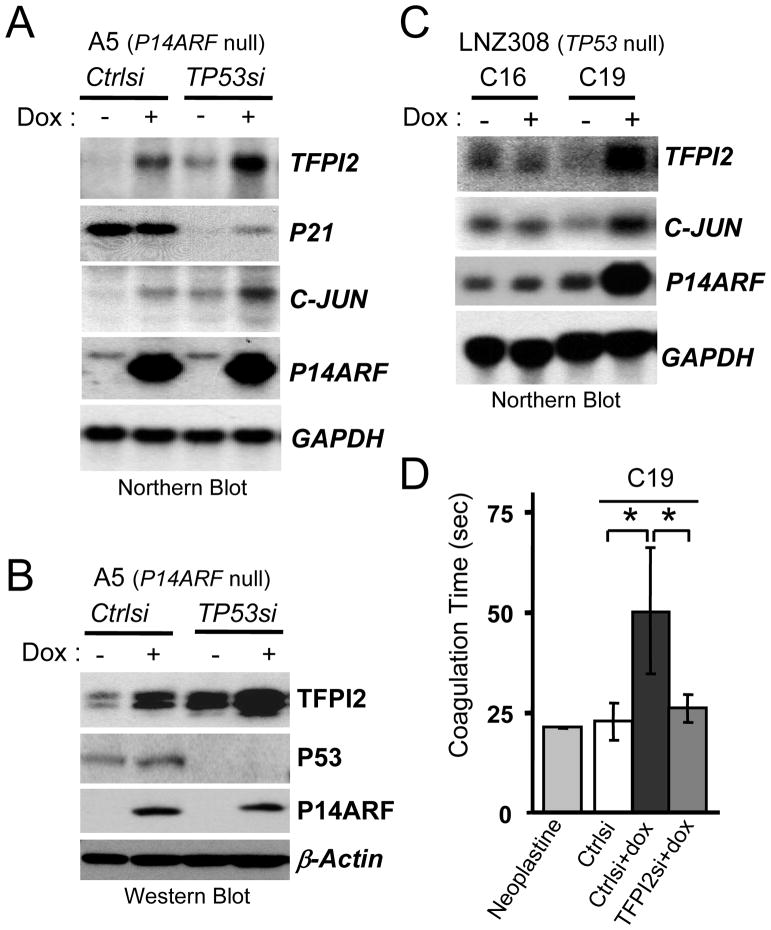

To start deciphering the signaling pathway connecting P14ARF to TFPI2, we first examined whether it was dependent on P53 as P14ARF induction activates the P53 pathway in A5 cells (Fig. 1A). As expected, siRNA mediated silencing of P53 in A5 cells caused a significant reduction of its downstream target CDKN1A/P21 transcription. Yet, it did not inhibit the activation of TFPI2 transcription by P14ARF, in fact, it even magnified its activation (Figs. 2A and B). The dispensability of P53 in P14ARF-mediated induction of TFPI2 expression (Fig. 2C) and anti coagulation activity (Fig. 2D) was further shown in TP53-null C19 human glioma cells, which stably express dox-inducible P14ARF. Dox had no effect on the parental LNZ308-C16 cells (rtTA positive, but not expressing P14ARF), which were used as controls for non-specific effects of dox. Taken together, these results confirm that the regulation of TFPI2 by P14ARF is P53 independent and suggests the existence of another cellular pathway coupling P14ARF to TFPI2.

Fig 2. TFPI2 is upregulated by P14ARF in a P53 independent manner.

(A) Specific silencing of P53 with siRNAs does not decrease the induction of TFPI2 by P14ARF. P21 mRNA levels are used as a readout of the transcriptional activity of P53.

(B) Western Blot showing the increase of TFPI2 expression following the induction of P14ARF in A5 cells.

(C) Northern blot showing TFPI2 mRNA increase upon P14ARF induction with dox in LNZ308-C19 (p53 null) glioma cells. C16, parental cells, not expressing P14ARF were used as control for the non-specific effects of dox. Note, P14ARF induces c-JUN transcription in both A5 (A) and C19 (C) cells.

(D) The induction of P14ARF in C19 cells increases clotting time of pooled normal human plasma, which can be reduced by the silencing of TFPI2 expression. *P<0.05.

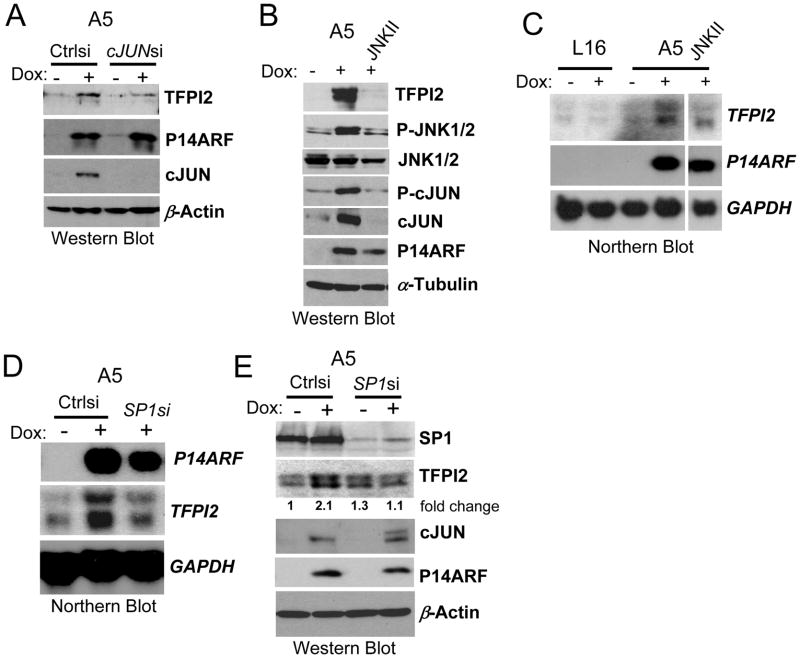

The promoter region of the human TFPI2 gene contains several putative binding sites for the transcription factor AP-1 upstream of the transcription initiation site (36), (37). Therefore, we examined whether P14ARF modulates c-JUN levels or its activity. Northern blot analysis showed an increase in c-JUN expression upon induction of P14ARF expression in A5 and C19 cells (Figs 2A and C). The role of c-JUN in the upregulation of TFPI2 by P14ARF was confirmed by silencing c-JUN in A5 cells (Fig. 3A). We then examined whether the increase in c-JUN also resulted in increased expression of its activated phosphorylated form. A robust upregulation of phospho-c-JUN was observed (Fig. 3B). We next examined whether P14ARF could directly affect the activity of JNK, the upstream kinase that activates AP-1 by phosphorylating c-JUN (38). The pharmacological inhibition of JNK decreased the levels of both total and phosphorylated c-JUN and strongly antagonized P14ARF-mediated upregulation of TFPI2 mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 3B and C). Together these results suggest that P14ARF can upregulate TFPI2 expression through the activation of JNK phosphorylation. The activated JNK can then phosphorylate its substrate c-Jun and lead to an auto-amplifying c-JUN expression loop that results in AP1 activation (38).

Fig 3. P14ARF upregulates TFPI2 gene expression through c-JUN and SP1.

(A) Western blot showing the silencing of c-JUN inhibits the induction of TFPI2 expression by P14ARF (dox) in A5 cells.

(B) Western blot showing the inhibition of JNK decreases TFPI2 expression concomitantly with the inhibition of JNK and c-JUN phosphorylation.

(C) Northern blot showing the induction of TFPI2 mRNA expression by P14ARF is diminished after pharmacological inhibition of JNK with JNKII (25μM).

(D and E) Northern and Western blots showing that the silencing of SP1 in A5 cells inhibits the induction of TFPI2 expression by P14ARF in A5 cells. GAPDH mRNA, α-Tubulin and β-Actin were used as loading controls. Relative densitometry of TFPI2 and β-Actin bands was used to calculate fold expression change.

Because the TFPI2 gene promoter can also bind SP1 (36) and we previously showed that P14ARF can upregulate the transcriptional activity of SP1 (28), we further examined whether SP1 played a role in TFPI2 activation by P14ARF. The silencing of SP1 abrogated the induction of TFPI2 mRNA and protein by P14ARF, even in the presence of induced c-JUN (Fig.3 D and E). These data suggest that SP1 and c-JUN cooperate to mediate the activation of TFPI2 gene expression by P14ARF.

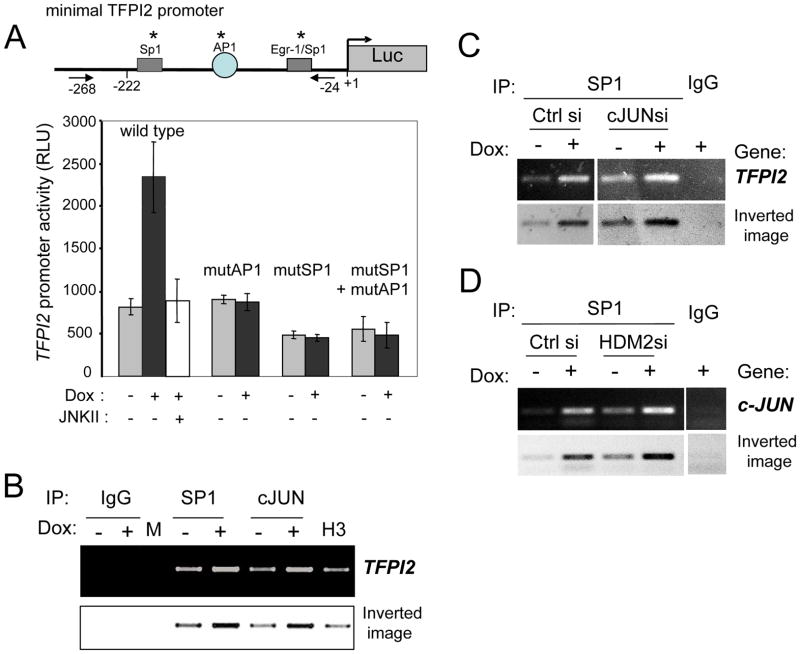

To further examine the respective roles of SP1 and AP1 in P14ARF induction of TFPI2 gene expression, we performed luciferase reporter and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays (Fig. 4). P14ARF induction by dox mediated a 2.5 fold increase in the transcription of a transiently transfected TFPI2 promoter driven luciferase reporter, which was abrogated by the pharmacological inhibition of JNK. Mutation of the AP1 and SP1 binding sites in the TFPI2 promoter singly or in combination totally abrogated the stimulatory effect of P14ARF, suggesting that both transcription factors are necessary for the gene activation (Fig.4A). These data also suggest that neither transcription factor is sufficient to mediate gene induction, but rather that they act in a cooperative fashion as each individual siRNA was sufficient to neutralize P14ARF-mediated reporter activation. SP1 (but not AP1) appears to also contribute to the basic activation of the promoter since its silencing decreases the basal reporter gene activity. We then investigated whether P14ARF increases the binding activity of c-JUN and/or SP1 to the endogenous TFPI2 promoter. ChIP assays demonstrated that the induction of P14ARF increased the binding of SP1 and c-JUN on the TFPI2 promoter (Fig. 4B). The coordinated activation of the TFPI2 promoter by SP1 and c-Jun was not due to cooperation in DNA binding as c-Jun silencing did not alter SP1 binding (Fig. 4C). IgGs served as negative control and Histone H3 as positive control. These results support a model whereby P14ARF increases TFPI2 gene transcription by stimulating the DNA binding of both SP1 and AP1. However, the P14ARF-induced mechanisms underlying the increased bindings of these transcription factors differ. P14ARF increases AP1 binding activity by indirectly augmenting the expression levels of phosphorylated c-Jun through JNK activation. In contrast, there is increased SP1 binding to the TFPI2 (Fig. 4B,C) and c-JUN (Fig. 4D) promoters without altering SP1 expression levels (Fig. 3E), in agreement with our prior findings that p14ARF enhances DNA binding and transcriptional activity of SP1 by freeing it from a negative interaction with HDM2 (28). Indeed, silencing of HDM2 further potentiated SP1 binding to the c-JUN promoter (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4. Induction of the hTFPI2 promoter activity by P14ARF.

(A) A5 cells were transiently transfected in serum free medium with TFPI2 promoter-luciferase reporter constructs +/− point mutations (*) in the AP1 and SP1 binding sites. P14ARF was induced by the addition of Dox. Luciferase activity was calculated as light units/μg of protein. Data are shown as mean +/−S.D. from one representative experiment performed in triplicate.

(B) ChIP assay showing the increase of c-JUN and SP1 binding to the TFPI2 promoter region that contains AP1 and SP1 binding sites. ChIPs with anti-histone H3 and IgGs as positive and negative binding controls, respectively.

(C) ChIP assay showing that silencing of c-JUN does not alter SP1 binding to the TFPI2 promoter. The position of primers used for the ChIP assay is indicated on the TFPI2 promoter in (A).

(D) ChIP assay showing that p14ARF (+dox) increases SP1 binding to the c-JUN promoter and that the binding is increased by HDM2 silencing.

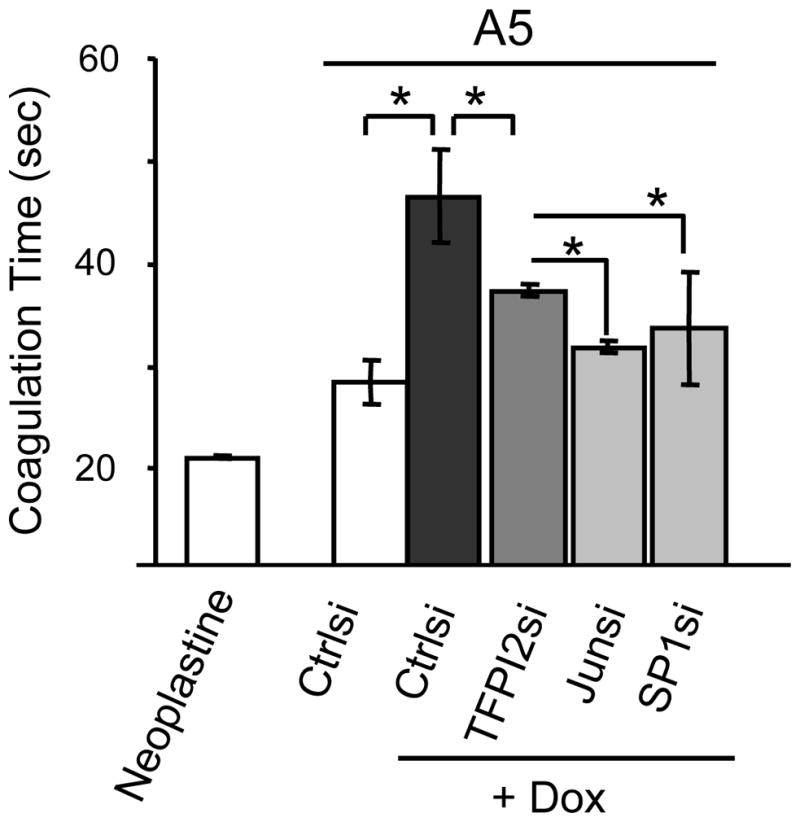

Finally, to determine whether SP1 and c-JUN are the downstream mediators of P14ARF’s negative regulation of coagulation, we silenced SP1, c-JUN and TFPI2 in A5 cells. We found that all three siRNAs were able to antagonize P14ARF’s ability to delay plasma clotting (Fig 5). These findings confirm that the anti-coagulation activity of P14ARF requires TFPI2 and its upstream regulators of transcription c-JUN and SP1.

Fig 5. The silencing of SP1 and c-JUN reverses the inhibition of plasma clotting by p14ARF.

A5 cells were transfected with negative control, TFPI2, c-JUN and SP1 siRNAs using Lipfectamine RNAimax for 72hrs. P14ARF was induced with dox for the last 48hrs and cells were prepared for the clotting assay. Neoplastine (thromboplastin) was used as positive control for the plasma clotting. Data are expressed as mean of the clotting time of three transfection experiments +/− S.D; statistical changes between groups was assessed with Student t-test. (*), p<0.05; (**), p<0.01.

Discussion

As part of their malignant phenotype, glioblastomas display distinct pathologic features including micronecrotic areas surrounded by pseudopalisading cells. The biological events triggering the appearance of these structures are incompletely understood, but there is growing evidence that they are in part initiated by vascular obstruction following blood clotting, depriving cells from oxygen and nutrients (39, 40). The genetic causes behind the GBM coagulopathy and the signaling events leading to the activation of the coagulation system in the tumor are poorly defined.

Our previous work has shown that GBM cells are able to activate coagulation by expressing Tissue Factor (TF), a unique cell-associated receptor for coagulation factor VIIa and key initiator of blood coagulation (13). Here we report that the tumor suppressor p14ARF is able to delay clot formation by inducing the transcription of TFPI2 in malignant human glioma cells, and thereby inhibiting the early steps of coagulation. TFPI2, also called Placental Protein 5 (PP5), is expressed and secreted primarily in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of a wide range of cells. TFPI2 contains three Kunitz-type inhibitor domains that mediate its anti-coagulation activity through binding the factor VIIa-TF complex (41). A tumor suppressive role for TFPI2 was initially suggested by the fact that it is abundant in normal tissue, but its expression decreases with tumor grade (42). Reduction in expression with tumor progression is in part explained by TFPI2 epigenetic silencing. The gene is methylated in over 20% of GBMs but not in normal brain (17, 43), and in many other cancers including carcinomas of the pancreas (44) gastric system (45), oesophagus (46) and prostate (18). This tumor associated epigenetic silencing of TFPI2 may be a common mechanism that causes an imbalance in tumors in favor of the local increase of procoagulation factors, which may trigger vascular thrombosis, hypoxia and necrosis.

Our findings now show that the loss of the CDKN2A locus, one of the most common genetic defects in cancers, also contributes to the regulation of TFPI2 expression in tumors. The regulation of this gene by P14ARF is new, and the underlying mechanisms are unknown. Given that P14ARF is known to exert some of its tumor suppressive functions through raising the levels of P53, we considered the involvement of p53 transcriptional activity in the regulation of TFPI2. However, we found that p14ARF upregulated the transcription of TFPI2 independently of P53, consistent with the absence of P53 binding sites in the human TFPI2 promoter. After considering candidate transcription factors with binding sites in the TFPI2 promoter region, we found that the silencing of SP1 and c-JUN, a major component of the AP1 transcription factor, significantly abrogated p14ARF-mediated induction of TFPI2. ChIP further showed that the binding of both transcriptions factors to the TFPI2 promoter was enhanced by p14ARF, and reporter assays suggested that gene activation might require cooperation of AP-1 and SP-1, as neither was sufficient. These results are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that the activation of AP1 and SP1 with phorbol esters can upregulate TFPI2 (36, 47).

The activation of AP-1 by p14ARF is the result of a signaling cascade that starts with p14ARF activating the phosphorylation of JNK. The latter then phosphorylates c-JUN, which leads to an auto-activating transcriptional loop of c-JUN expression and further amplifies phospho-c-JUN levels (38, 48). How exactly p14ARF might increase JNK phosphorylation remains to be determined. JNK has many upstream activators (49), and each one of them might be a potential target for P14ARF. Further studies are needed to explore this activation. Unlike for c-JUN, we did not observe a difference in the levels of SP1 protein upon P14ARF induction. We recently showed that P14ARF could activate SP1 DNA binding and transcription of the TIMP3 gene by freeing SP1 from a negative regulation by MDM2 (28). The same mechanism likely applies for p14ARF regulation of SP1 binding to the TFPI2 and c-JUN promoters, the latter leading to indirect amplification of AP-1 mediated TFPI2 gene activation.

In summary, we report a new tumor suppressive activity for p14ARF as an inhibitor of tumor-induced coagulation. This activity is mediated by a JNK/c-JUN activation cascade, which leads to AP-1 activation, and transcriptional upregulation of TFPI2 expression in coordination with SP-1 activation. Altogether, these findings suggest that TFPI2 expression can be a barrier to tumor development and that loss of its expression through epigenetic or genetic alteration of p14ARF or its downstream effectors may contribute to the aggressiveness of glioblastomas. These findings also point to potential therapeutic implications for TFPI2 as its specific Kunitz domains could be used to antagonize thrombosis in tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the NIH CA86335, CA116804 (to EGVM) and CA149107 (to DJB), the Southeastern Brain Tumor Foundation (to A.Z and EGVM), and P30 CA138292 to the Winship Cancer Institute. We thank Dr. Walter Kisiel, (Institute of Pharmacology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Krakow, Poland) for providing the anti-TFPI2 antibody, Dr. Christina Kast (Biotechnology Research Institute, Montreal, Canada) for providing the TFPI2-luciferase reporter plasmids and Dr. Russ Pieper (UCSF, San Francisco, USA) for providing the transformed human astrocytes.

Abbreviations

- ARF

Alternative Reading Frame

- ChIP

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

- Dox

doxycycline

- JNK

Jun Kinase

- TF

Tissue Factor

- TFPI2

Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor 2

Footnotes

Author contributions: AZ and EGVM conceived the project and designed the experiments, AZ performed and coordinated experiments in collaboration with BP for northern analyses and advice from DJB for plasma clotting assays. AZ and EGVM interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and commented on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Van Meir EG, Hadjipanayis CG, Norden AD, Shu HK, Wen PY, Olson JJ. Exciting new advances in neuro-oncology: the avenue to a cure for malignant glioma. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:166–93. doi: 10.3322/caac.20069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brat DJ, Castellano-Sanchez AA, Hunter SB, Pecot M, Cohen C, Hammond EH, et al. Pseudopalisades in glioblastoma are hypoxic, express extracellular matrix proteases, and are formed by an actively migrating cell population. Cancer Res. 2004;64:920–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong ML, Prawira A, Kaye AH, Hovens CM. Tumour angiogenesis: its mechanism and therapeutic implications in malignant gliomas. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kornyei JL, Li X, Lei ZM, Rao CV. Analysis of epidermal growth factor action in human myometrial smooth muscle cells. J Endocrinol. 1995;146:261–70. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1460261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plate KH, Mennel HD. Vascular morphology and angiogenesis in glial tumors. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 1995;47:89–94. doi: 10.1016/S0940-2993(11)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;359:843–5. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tohma Y, Gratas C, Van Meir EG, Desbaillets I, Tenan M, Tachibana O, et al. Necrogenesis and Fas/APO-1 (CD95) expression in primary (de novo) and secondary glioblastomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1998;57:239–45. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199803000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogiichi T, Hirashima Y, Nakamura S, Endo S, Kurimoto M, Takaku A. Tissue factor and cancer procoagulant expressed by glioma cells participate in their thrombin-mediated proliferation. J Neurooncol. 2000;46:1–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1006323200001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rao LV, Rapaport SI, Bajaj SP. Activation of human factor VII in the initiation of tissue factor-dependent coagulation. Blood. 1986;68:685–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rong Y, Belozerov VE, Tucker-Burden C, Chen G, Durden DL, Olson JJ, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and PTEN modulate tissue factor expression in glioblastoma through JunD/activator protein-1 transcriptional activity. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2540–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukasa A, Wykosky J, Ligon KL, Chin L, Cavenee WK, Furnari F. Mutant EGFR is required for maintenance of glioma growth in vivo, and its ablation leads to escape from receptor dependence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2616–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914356107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen J, Bierhaus A, Schiekofer S, Andrassy M, Chen B, Stern DM, et al. Tissue factor--a receptor involved in the control of cellular properties, including angiogenesis. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:334–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rong Y, Post DE, Pieper RO, Durden DL, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ. PTEN and hypoxia regulate tissue factor expression and plasma coagulation by glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1406–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie TX, Aldape KD, Gong W, Kanzawa T, Suki D, Kondo S, et al. Aberrant NF-kappaB activity is critical in focal necrosis formation of human glioblastoma by regulation of the expression of tissue factor. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:5–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanir N, Aharon A, Brenner B. Procoagulant and anticoagulant mechanisms in human placenta. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29:175–84. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takada H, Wakabayashi N, Dohi O, Yasui K, Sakakura C, Mitsufuji S, et al. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 (TFPI2) is frequently silenced by aberrant promoter hypermethylation in gastric cancer. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;197:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konduri SD, Srivenugopal KS, Yanamandra N, Dinh DH, Olivero WC, Gujrati M, et al. Promoter methylation and silencing of the tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 (TFPI-2), a gene encoding an inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases in human glioma cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4509–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribarska T, Ingenwerth M, Goering W, Engers R, Schulz WA. Epigenetic inactivation of the placentally imprinted tumor suppressor gene TFPI2 in prostate carcinoma. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2010;7:51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quelle DE, Zindy F, Ashmun RA, Sherr CJ. Alternative reading frames of the INK4a tumor suppressor gene encode two unrelated proteins capable of inducing cell cycle arrest. Cell. 1995;83:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90214-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pomerantz J, Schreiber-Agus N, Liegeois NJ, Silverman A, Alland L, Chin L, et al. The Ink4a tumor suppressor gene product, p19Arf, interacts with MDM2 and neutralizes MDM2’s inhibition of p53. Cell. 1998;92:713–23. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamijo T, Zindy F, Roussel MF, Quelle DE, Downing JR, Ashmun RA, et al. Tumor suppression at the mouse INK4a locus mediated by the alternative reading frame product p19ARF. Cell. 1997;91:649–59. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weber HO, Samuel T, Rauch P, Funk JO. Human p14(ARF)-mediated cell cycle arrest strictly depends on intact p53 signaling pathways. Oncogene. 2002;21:3207–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kelly-Spratt KS, Gurley KE, Yasui Y, Kemp CJ. p19Arf suppresses growth, progression, and metastasis of Hras-driven carcinomas through p53-dependent and -independent pathways. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E242. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamijo T, van de Kamp E, Chong MJ, Zindy F, Diehl JA, Sherr CJ, et al. Loss of the ARF tumor suppressor reverses premature replicative arrest but not radiation hypersensitivity arising from disabled atm function. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2464–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamijo T, Bodner S, van de Kamp E, Randle DH, Sherr CJ. Tumor spectrum in ARF-deficient mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radfar A, Unnikrishnan I, Lee HW, DePinho RA, Rosenberg N. p19(Arf) induces p53-dependent apoptosis during abelson virus-mediated pre-B cell transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13194–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weber JD, Jeffers JR, Rehg JE, Randle DH, Lozano G, Roussel MF, et al. p53-independent functions of the p19(ARF) tumor suppressor. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2358–65. doi: 10.1101/gad.827300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zerrouqi A, Pyrzynska B, Febbraio M, Brat DJ, Van Meir EG. P14ARF inhibits human glioblastoma-induced angiogenesis by upregulating the expression of TIMP3. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1283–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI38596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishii N, Maier D, Merlo A, Tada M, Sawamura Y, Diserens AC, et al. Frequent co-alterations of TP53, p16/CDKN2A, p14ARF, PTEN tumor suppressor genes in human glioma cell lines. Brain Pathol. 1999;9:469–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.1999.tb00536.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaur B, Brat DJ, Devi NS, Van Meir EG. Vasculostatin, a proteolytic fragment of brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1, is an antiangiogenic and antitumorigenic factor. Oncogene. 2005;24:3632–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albertoni M, Shaw PH, Nozaki M, Godard S, Tenan M, Hamou MF, et al. Anoxia induces macrophage inhibitory cytokine-1 (MIC-1) in glioblastoma cells independently of p53 and HIF-1. Oncogene. 2002;21:4212–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sonoda Y, Ozawa T, Hirose Y, Aldape KD, McMahon M, Berger MS, et al. Formation of intracranial tumors by genetically modified human astrocytes defines four pathways critical in the development of human anaplastic astrocytoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4956–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tan C, de Noronha RG, Roecker AJ, Pyrzynska B, Khwaja F, Zhang Z, et al. Identification of a novel small-molecule inhibitor of the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 pathway. Cancer Res. 2005;65:605–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kast C, Wang M, Whiteway M. The ERK/MAPK pathway regulates the activity of the human tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6787–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210935200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y, Xiong Y, Yarbrough WG. ARF promotes MDM2 degradation and stabilizes p53: ARF-INK4a locus deletion impairs both the Rb and p53 tumor suppression pathways. Cell. 1998;92:725–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81401-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hube F, Reverdiau P, Iochmann S, Cherpi-Antar C, Gruel Y. Characterization and functional analysis of TFPI-2 gene promoter in a human choriocarcinoma cell line. Thromb Res. 2003;109:207–15. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamei S, Kazama Y, Kuijper JL, Foster DC, Kisiel W. Genomic structure and promoter activity of the human tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1517:430–5. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(00)00298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minden A, Lin A, Smeal T, Derijard B, Cobb M, Davis R, et al. c-Jun N-terminal phosphorylation correlates with activation of the JNK subgroup but not the ERK subgroup of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6683–8. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shoji M, Hancock WW, Abe K, Micko C, Casper KA, Baine RM, et al. Activation of coagulation and angiogenesis in cancer: immunohistochemical localization in situ of clotting proteins and vascular endothelial growth factor in human cancer. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:399–411. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rong Y, Durden DL, Van Meir EG, Brat DJ. ‘Pseudopalisading’ necrosis in glioblastoma: a familiar morphologic feature that links vascular pathology, hypoxia, and angiogenesis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65:529–39. doi: 10.1097/00005072-200606000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sprecher CA, Kisiel W, Mathewes S, Foster DC. Molecular cloning, expression, and partial characterization of a second human tissue-factor-pathway inhibitor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:3353–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rao CN, Lakka SS, Kin Y, Konduri SD, Fuller GN, Mohanam S, et al. Expression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor 2 inversely correlates during the progression of human gliomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:570–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaitkiene P, Skiriute D, Skauminas K, Tamasauskas A. Associations between TFPI-2 methylation and poor prognosis in glioblastomas. Medicina (Kaunas) 2012;48:345–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sato N, Parker AR, Fukushima N, Miyagi Y, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Eshleman JR, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of TFPI-2 as a common mechanism associated with growth and invasion of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:850–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jee CD, Kim MA, Jung EJ, Kim J, Kim WH. Identification of genes epigenetically silenced by CpG methylation in human gastric carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1282–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jia Y, Yang Y, Brock MV, Cao B, Zhan Q, Li Y, et al. Methylation of TFPI-2 is an early event of esophageal carcinogenesis. Epigenomics. 2012;4:135–46. doi: 10.2217/epi.12.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konduri SD, Osman FA, Rao CN, Srinivas H, Yanamandra N, Tasiou A, et al. Minimal and inducible regulation of tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 in human gliomas. Oncogene. 2002;21:921–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Karin M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1996;351:127–34. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1996.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishina H, Nakagawa K, Azuma N, Katada T. Activation mechanism and physiological roles of stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase in mammalian cells. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2003;17:295–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]