The human innate immune system identifies Gram-negative bacteria by recognizing lipopolysaccharides (LPS), components of the microbial cell wall (1). This detection triggers massive inflammatory responses that help eradicate infections, but may also result in immunopathology if regulated improperly. Hence, LPS is also referred to as endotoxin. More than a century after its discovery, the molecular basis for the inflammatory activity of endotoxin was finally revealed by the discovery that Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) induces innate and adaptive immune responses to LPS (2). TLR4 is the founding member of the mammalian Toll-like receptor family, and its discovery heralded a new age in the study of host-microbe interactions. On pages 1250 and 1246 of this issue, Hagar et al. (3) and Kayagaki et al. (4), respectively, reveal the existence of cellular responses to LPS that do not depend on TLR4. The search for the new LPS receptor can now begin.

For years, it was assumed that TLR4 was solely responsible for cellular responses induced by LPS (5, 6). TLR4-deficient cells are defective for all classically defined transcriptional responses to LPS, including the expression of inflammatory cytokines and interferons (7). However, LPS can also induce nontranscriptional cellular responses, such as autophagy, endocytosis, phagocytosis, and oxidative bursts (8–11). Hagar et al. and Kayagaki et al. add to this list of atypical responses to LPS, by showing that LPS activates the formation of an atypical inflammasome governed by the enzyme caspase-11.

Inflammasomes are protein complexes that are assembled in the cytosol of macrophages in response to a variety of extracellular stimuli (12). The best-defined function of inflammasomes is to promote the processing and secretion of inflammatory cytokines of the interleukin-1 (IL-1) family. At the center of the best-characterized inflammasomes is the the precursor of IL-1 in the cytosol of macrophages. Cleaved IL-1 family members are then secreted to induce inflammation. A second class of inflammasomes also requires caspase-11 to promote IL-1 cleavage (13). These noncanonical inflammasomes are activated by intracellular bacteria and contribute to the phenotypes associated with sepsis. How these noncanonical inflammasomes are activated remains unclear.

Hagar et al. and Kayagaki et al. recognized that several species of Gram-negative bacteria can activate caspase-11–dependent IL-1 secretion (13). Thus, a molecule common to Gram-negative bacteria must be responsible for activating caspase-11. Both research groups show that LPS is the molecule of interest. For example, Hagar et al. show that when transfected into macrophages, cell lysates derived from Gram-negative bacteria, but not Gram-positive bacteria (which contain no LPS), can activate caspase-11. This effect was insensitive to proteases and nucleases, thus ruling out the actions of any protein or DNA/RNA species in the bacterial lysate. However, the effect was lost when the lysate was treated with ammonium hydroxide, a chemical that inactivates LPS. Both Hagar et al. and Kayagaki et al. showed that transfection of pure LPS into macrophages was sufficient to activate caspase-11.

Interestingly, both Hagar et al. and Kayagaki et al. found that to activate this non-canonical inflammasome, LPS must be in a complex with transfection reagents, or some other means of delivering LPS into the intra-cellular compartment(s) of the cell. Because TLR4 senses LPS in the extracellular environment, this observation suggested that TLR4 was not responsible for activating caspase-11. Indeed, macrophages lacking TLR4 retained the ability to activate caspase-11 in response to transfected LPS. Thus, an additional LPS sensor must be present within cells. These studies provide the mandate to begin the search for this protein, and understand its function in host-microbe interactions and inflammation.

Although the identity of this new LPS sensor remains unknown, the studies by Hagar et al. and Kayagaki et al. provide some clues as to where this protein may reside in the cell. That LPS must be delivered into the cell suggests that the LPS sensor is present in an intracellular location. Hagar et al. showed that LPS can activate caspase-11 if it is in a complex with the Gram-positive bacteria Listeria monocytogenes, but only if the bacteria can enter the cytosol of the host cell. This indicates that the LPS sensor is a cytosolic protein. However, both studies also used the B subunit of cholera toxin as an “LPS delivery vehicle.” Cholera toxin B follows a retrograde vesicular trafficking pathway from the plasma membrane to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum, but never accesses the cytosol (14). This raises the intriguing possibility that the LPS sensor does not reside in the cytosol, but instead in an intracellular compartment. Future genetic and cell biological studies are necessary to elucidate this fascinating new LPS sensory system.

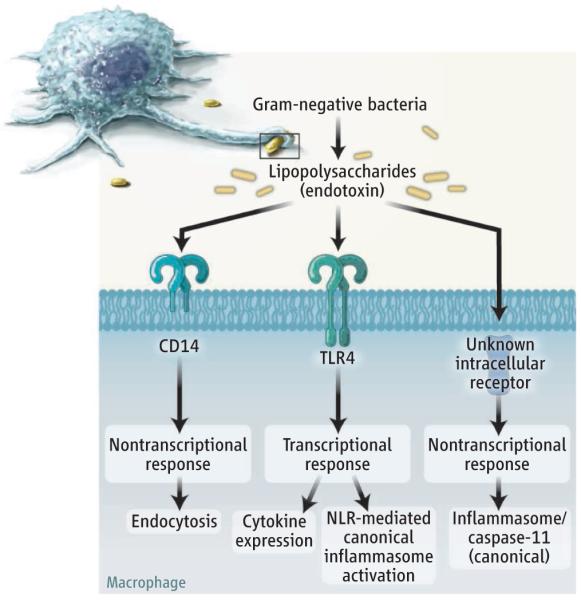

The identification of a cellular response to LPS that does not require TLR4 draws parallels with recent work on other nontranscriptional responses to LPS. For example, the ability of LPS to induce endocytosis is controlled not by TLR4, but rather by the protein CD14 (15). Thus, a theme is emerging whereby TLR4 controls all transcriptional responses to LPS, but at least some of the equally important nontranscriptional responses are controlled by receptors other than TLR4 (see the figure). A future challenge will be to define not only the regulators of this new LPS response, but also how all responses to bacteria are interconnected in space and time.

Sensing lipopolysaccharides.

Macrophages respond to Gram-negative bacteria by activating transcriptional and nontranscriptional immune responses. Some of these responses are handled by protein complexes called infl ammasomes. An intracellular sensor for lipopolysaccharides was revealed, but its identity has yet to be determined.

Footnotes

Macrophages respond to bacteria through a protein complex that promotes inflammation when activated by internalized bacterial endotoxin.

References

- 1.Gioannini TL, Weiss JP. Immunol. Res. 2007;39:249. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medzhitov R. Immunity. 2009;30:766. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hagar JA, et al. Science. 2013;341:1250. doi: 10.1126/science.1240988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kayagaki N, et al. Science. 2013;341:1246. doi: 10.1126/science.1240248. 10.1126/science.1240248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beutler B. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2000;12:20. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poltorak A, et al. Science. 1998;282:2085. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng J, et al. J. Immunol. 2011;187:3683. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Science. 2004;304:1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1096158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanjuan MA, et al. Nature. 2007;450:1253. doi: 10.1038/nature06421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West AP, et al. Nature. 2011;472:476. doi: 10.1038/nature09973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West MA, et al. Science. 2004;305:1153. doi: 10.1126/science.1099153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Immunol. Rev. 2009;227:95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ng TM, Monack DM. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;14:9. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chinnapen DJ, Chinnapen H, Saslowsky D, Lencer WI. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007;266:129. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanoni I, et al. Cell. 2011;147:868. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]