Abstract

The erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) erythropoietin and darbepoetin prevent transfusions among chemotherapy-associated anemia patients. Clinical trials, meta-analyses, and guidelines identify mortality, tumor progression, and venous thromboembolism (VTE) risks with ESA administration in this setting. Product labels advise against administering ESAs with potentially curative chemotherapy (United States) or to conduct risk–benefit assessments (Europe/Canada). Since 2007, fewer chemotherapy-associated anemia patients in the United States and Europe receive ESAs. ESAs and the erythropoietin receptor agonist peginesatide prevent transfusions among chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients; clinical trials, guidelines, and meta-analyses demonstrate myocardial infarction, stroke, VTE, or mortality risks with ESAs targeting high hemoglobin levels. U.S. labels recommend administering ESAs or peginesatide at doses sufficient to prevent transfusions among dialysis CKD patients. For dialysis CKD patients, Canadian and European labels recommend targeting hemoglobin levels of 10 to 12 g/dL and 11 to 12 g/dL, respectively, with ESAs. ESA utilization for dialysis CKD patients has decreased in the United States.

Keywords: darbepoetin, epoetin, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, peginesatide

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) treat chemotherapy- or chronic kidney disease (CKD)-associated anemia. Beginning in 1989 in the CKD setting, regulatory agencies approved erythropoietin and darbepoetin (in Canada) and erythropoietin, darbepoetin, and peginesatide (United States) to prevent transfusions, and erythropoietin and darbepoetin to treat symptomatic anemia (Europe). In 1993 and 2002, erythropoietin and darbepoetin, respectively, received regulatory approvals for prevention of transfusions or treatment of symptomatic anemia among persons with cancer and chemotherapy-associated anemia. For CKD patients receiving hemodialysis, although partial anemia correction is beneficial, one trial reported mortality/myocardial event risks with epoetin administration targeted to complete anemia correction.1 For CKD patients with diabetes not receiving hemodialysis, one trial identified cerebrovascular accident risks with darbepoetin targeting high hemoglobin levels versus rescue therapy for moderately severe anemia.2 For CKD patients not receiving hemodialysis, two trials identified myocardial infarction risks with peginesatide versus darbepoetin.3 In oncology, two trials identified poorer survival with epoetin.4,5 These trials necessitate reassessment of ESAs (▶Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of pharmaceutical company notifications; clinical guidelines; meta-analyses; CMS policy decisions; and FDA, Canada Health, and EMA Advisory Committee recommendations for ESAs

| CKD | Chemotherapy-associated anemia | |

|---|---|---|

| November 2006 (FDA) | Public health advisory issued for patients and physicians stating that in a phase III trial among CKD patients not on hemodialysis, those who received erythropoietin targeted to hemoglobin level of 13.5 g/dL experienced more death and life-threatening clinical events than those who were treated with hemoglobin target of 11.3 g/dL. |

None |

| January 2007 (FDA) | None | Dear Healthcare Professional letter from AMGEN is posted on the FDA’s Med Watch Web site. The letter states that there were 136 deaths in a darbepoetin alfa group compared with 94 deaths in a placebo group in a 16-week treatment phase of a phase III study among cancer patients with nonmyeloid malignancies receiving darbepoetin. |

| February 2007–drug information page (FDA) |

None | Increased risks of death and no reduction in transfusions observed in a phase III trial with darbepoetin versus placebo among cancer patients not receiving chemotherapy |

| March 2007–public health advisory, news release, question and answers (FDA) |

Increased death and serious cardiovascular event risks with target hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL; increased thrombotic risks with ESAs |

ESAs increased risks of death or tumor progression with breast and head and neck cancer or cancer patients not receiving therapy with target hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL; increased thrombotic risks with ESAs |

| November 2007– recommendations (FDA) |

Target hemoglobin levels between 10 and 12 g/dL; avoid administering high ESA doses to hyporesponders. |

Stop ESAs when chemotherapy treatment ends |

| November 2007–warnings (FDA) | Mortality and serious cardiovascular event risks greater with target hemoglobin levels of 13.5–14 g/dL |

Cancers for which ESA dosing targeted hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL resulted in cancer progression/ shortened survival and added lymphoid and non–small cell lung malignancies. There is no evidence of tumor progression or mortality risks when used according to regulatory indications. |

| March 2008–warnings (FDA) | No change | Added cervical cancer for which ESA dosing targeted to hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL resulted in cancer progression or shortened survival |

| June 2011 (FDA) | Public health advisory warns of cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, or mortality risks with ESA administration to nondialysis CKD patients or when ESAs are administered to CKD patients targeting high hemoglobin levels. |

- |

| December 2011 (FDA’s Oncologic Advisory Committee) |

Warns of increased safety risks with peginesatide versus darbepoetin for CKD patients not on dialysis and no increased safety risks of peginesatide versus epoetin for CKD patients on dialysis. Identifies noninferiority with every 28 days peginesatide versus every 2 weeks darbepoetin or one to three times per week dosing of epoetin among CKD patients. |

- |

| March 2012 | Approves peginesatide for treatment of anemia among CKD patients on dialysis |

- |

| December 2007–(CHMP of EMA and MHRA of United Kingdom) |

None | Hemoglobin overcorrection increased thrombosis risks. ESAs should not be administered to cancer patients not receiving chemotherapy or with hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL. |

| February 2008 (EMA) | ESAs are indicated for treatment of symptomatic anemia associated with CKD or chemotherapy; target hemoglobin levels of 10–12 g/dL; avoid achieving hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL because trials identified increased mortality for CKD and cancer patients at this level. The relevant results of the trials triggering the safety review were also added. |

ESAs are indicated for treatment of symptomatic anemia associated with CKD or chemotherapy; target hemoglobin levels of 10–12 g/dL; avoid achieving hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL because trials identified increased mortality for CKD and cancer patients at this level. Relevant results of five clinical trials triggering the safety review were added. |

| July 2008 (CHMP and MHRA) | - | Based onmeta-analysis of Bennett et al, one additional clinical trial, and unpublished data, increased risks of tumor progression, venous thromboembolism, and mortality among cancer patients receiving ESAs versus not. EMA concluded that benefits still outweighed risks in approved indications. Among cancer patients with reasonably long life expectancy, benefits may not outweigh risks of tumor progression. |

| August 2008 (CHMP) | - | Based on two additional trials and prior evidence, available evidence suggests that ESA use in cancer patients is associated with reduced survival and negative effect on progression-free survival. In authorized indication, data do not definitively show that risks outweigh benefits. However, blood transfusion should be preferred for symptomatic chemotherapy-associated anemia patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemotherapy with curative intent. ESA decision should be based on informed risk–benefit assessments. |

| September 2009 (CHMP) | - | CHMP recommends that the Summary of Product Characteristics be revised to include the Cochrane Results. |

| July 2010 (EMA) | - | Revised Summary of Product Characteristic text describes findings from the 2009 Cochrane individual patient data meta-analysis. |

| April 2007–warnings (Canada Health) |

Increased death and serious cardiovascular event risks with target hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL; increased thrombotic risks with ESAs |

ESAs increased risks of death or tumor progression with breast and head and neck cancer or cancer patients not receiving therapy with target hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL; increased thrombosis risks with ESAs. Indication to treat cancer-related anemia among patients not receiving chemotherapy was rescinded. |

| ESA manufacturer notifications | ||

| March 2007 (US) | Use lowest ESA dose required to avoid transfusion. | Use lowest ESA dose required to avoid transfusion. New boxed warning, updated warnings, and a change to the dosage and administration sections for all ESAs stating that four new studies in patients with cancer found a higher chance of serious and life-threatening side effects or death with the use of ESAs. These research studies were evaluating an unapproved dosing regimen, a patient population for which ESAs are not approved, or a new unapproved ESA. |

| April 2007 (US) | None | The manufacturer of darbepoetin issued a statement indicating that final results from the anemia of cancer trial found a higher risk of death among cancer patients receiving darbepoetin versus placebo (48.5 vs. 46%, p < 0.05) |

| November 2007 (US) | Target hemoglobin ranges should be between 10 and 12 g/dL and high ESA doses should be avoided; some QOL claims were removed. |

Revised labels indicated that clinical trials identified cancer progression and mortality risks among lymphoid and non–small cell lung cancers |

| March 2008 (US) | No change | Tumor progression and mortality risks occurred in a trial of ESA administration to cervical cancer patients receiving chemoradiotherapy. |

| July 2008 (US) | - | ESAs should not be administered to anemic cancer patients who are receiving chemotherapy for potentially curable malignancies; text indicating that it is safe to continue ESA treatment for chemotherapy-associated anemia until hemoglobin levels reach 12 g/dL was removed. |

| February 2010 (US) | - | REMS implemented requiring that all providers of ESAs to cancer patients receive education on the risks and benefits of their use in this setting. |

| June 2011 (US) | Increased mortality risks, adverse cardiovascular reactions, and stroke when administered to target hemoglobin level greater than 11 g/dL. |

- |

| September 2007 (Europe) | ESAs are indicated for the treatment of symptomatic anemia among CKD patients |

ESAs are indicated for the treatment of symptomatic anemia among patients with chemotherapyassociated anemia |

| December 2007 (Europe) | Target hemoglobin levels should be between 10 and 12 g/dL, and high hemoglobin levels should be avoided. CKD patients should be symptomatic. (MHRA) |

Overcorrection of hemoglobin or administration outside of labeled indications is associated with increased mortality and tumor progression risks. Administer lowest approved dose to adequately control symptoms. (MHRA) |

| February 2008 (Europe) | Increased mortality and cardiovascular morbidity with targeting relatively high hemoglobin levels among CKD patients. Target hemoglobin should be 10–12 g/dL and CKD patients are symptomatic; high ESAs should be avoided. (MHRA) |

Target hemoglobin should be 10–12 g/dL; high ESAs should be avoided. Amended Special Warnings indicate ESAs have not been shown to improve overall survival or decrease the risk of tumor progression in patients with anemia associated with cancer. ESA trials found unexplained excess mortality in association with target hemoglobin concentrations > 12 g/dL, including shortened time to tumor progression in patients with advanced head and neck cancer receiving radiation therapy, shortened overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving chemotherapy, and increased risk of death when administered to target a hemoglobin of 12 g/dL in patients with active malignant disease receiving neither chemotherapy nor radiation therapy. Clinical trials in patients with CKD have also observed an increased risk of death and serious cardiovascular events when ESAs were administered to target a hemoglobin > 12 g/dL. (MHRA) |

| September 2008 (Europe) | No change | Product Assessment Reports indicate that erythropoietin receptors may be on tumor cells. As a potential growth factor, ESA administration may affect these receptors and result in tumor growth and death. |

| October 2008 (Europe) | No Change | Recent data from Bennett et al and five randomized trials show consistent unexplained excess mortality in ESA-treated cancer patients. The Product Assessment Report indicates that in some clinical situations, blood transfusions should be preferred as anemia treatment for cancer patients. The decision to administer ESAs should be based on risk–benefit assessment with consideration of clinical context, tumor type, stage, degree of anemia, life expectancy, and patient preference. |

| 2009 (Canada) | Increased mortality risks with ESA administration to CKD patients with hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL. |

The Product Monograph indicates that ESA decisions should be based on risk, benefit, and patient preferences. Increased death/cardiovascular event risks with ESA use in the cancer setting targeted to higher hemoglobin levels; transfusions are preferred among patients with reasonable life expectancies; and trigger ESA hemoglobin levels are 10 g/dL. |

| Clinical guidelines | ||

| 2006 (US) | Hemoglobin should be 11.0 g/dL or greater; insufficient evidence to recommend routinely maintaining hemoglobin levels at 13.0 g/dL or greater. (KDOQI) |

ESAs should not be administered to cancer patients receiving potentially curative chemotherapy. Trigger and target hemoglobin levels were removed. Physicians were advised to provide patients with Medication Guides prior to administering ESAs. (NCCN) |

| 2007 (US) | Hemoglobin target level should generally be in the range of 11–12 g/dL; target should not be greater than 13.0 g/dL. (KDOQI) |

ESAs are recommended for cancer patients with hemoglobin levels < 10 g/dL or whose levels are approaching this level (ASCO/ASH and NCCN). (United States) |

| 2008 (US) | None | ESAs are not recommended for anemic cancer patients who are receiving potentially curative therapy or who have breast or head and neck cancer (NCCN) (United States) |

| 2009 (US) | Hemoglobin levels should be maintained between 11 and 12 g/dL and should not exceed 13 g/dL. (European Best Practices) |

All ESA-treated cancer patients should read a Patient Medication Guide prior to administration of an ESA. The first sentence of the Guide states that the most important consideration for the patient is that ESA administration to cancer patients is associated with increased risks of death and other serious adverse events. (NCCN) (United States) |

| 2010 (US) | None | ESAs are not recommended to target high hemoglobin levels and should not be used with potentially curative chemotherapy (ASCO/ASH) |

| 2011 (US) | Consider starting ESA treatment when the hemoglobin level is less than 10 g/dL. Individualize dosing and use the lowest dose of ESA sufficient to reduce need for transfusions. (FDA) |

None |

| 2008 (Canada) | Target hemoglobin levels of 10–12 g/dL for CKD patients. There is excess mortality with higher hemoglobin targets and less data supporting further QOL improvements when achieving hemoglobin levels above 11 g/dL. (Canadian Society of Nephrology) |

None |

| 2009 (Canada) | None | Higher risks of death/serious cardiovascular adverse events when cancer patients received ESAs targeted to hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL. Achieved hemoglobin levels with ESAs should be < 12 g/dL. (Cancer Care Ontario) |

| 2007 (Europe) | None | ESAs should be initiated at hemoglobin levels of 9–11 g/dL in symptomatic cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and considered in asymptomatic chemotherapy patients with hemoglobin levels of 11–11.9 g/dL (Working Party of the EORTC) |

| 2011 (United Kingdom) | Target hemoglobin levels of 10–12 g/dL for CKD patients. Among nondialysis CKD patients, targeting hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL was associated with fewer quality-adjusted life years and higher costs. (National Institutes of Health and Clinical Excellence) |

|

| Meta-analyses | ||

| Mortality | Increased mortality risk with higher versus lower target hemoglobin levels (February 2007 meta-analysis) |

1.03-fold decreased relative risk ofmortality with ESAs versus placebo/control; p > 0.05 (West Midlands Health Technology Assessment Collaborative 2007) |

| Mortality | No increased mortality risk with higher versus lower target hemoglobin levels (KDOQI 2007) |

1.10-fold increased relative risk of mortality with ESAs versus placebo/control (meta-analysis of studies reported prior to February 2008; p < 0.05) (Bennett et al 2008) |

| Mortality | Intermediate hemoglobin targets (11 g/dL) produced the largest quality-adjusted life years at incremental cost of Can$25,000 per patient lifetime versus low hemoglobin targets. (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health 2008) |

1.15-fold increased relative risk ofmortality with EASA versus placebo/control patients; p = 0.05 (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health 2009) |

| Mortality | ESAs were associated with QOL improvements and decreased cardiovascular mortality, although overall mortality was similar. (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health 2008) |

1.17-fold increased relative risk of mortality with ESAs versus placebo/control; p = 0.05 (individual patient-level meta-analysis) (Cochrane 2009) |

| Vascular events | Increased cardiovascular events with higher versus lower target hemoglobin levels among nondialysis CKD patients, but not dialysis CKD patients (KDOQI 2007) |

1.67-fold increased VTE risks with ESAs versus placebo/control; p < 0.05 (Cochrane 2006) |

| Vascular events | No increased myocardial infarction risks with higher versus lower target hemoglobin levels among CKD patients (February 2007 meta-analysis) |

1.57-fold increased VTE risks with ESAs versus placebo/control; p < 0.05 (RADAR 2008) |

| Vascular events | ESA administration was associated with decreased cardiovascular mortality (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health 2008) |

1.69-fold increased VTE risks with ESAs versus placebo/control; p < 0.05 (Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health 2009) |

| Policy decisions (US) | ||

| 2006 CMS National Coverage Decisions |

Requires 25% ESA dose reduction when hemoglobin > 13 g/dL or payment will be reduced. Sets maximal billable monthly dose at 500,000 Units per month. |

None |

| 2007 CMS National Coverage Decisions |

None | Limit initiation of ESA therapy to hemoglobin levels < 10 g/dL; ESA duration for a maximum of 8 weeks after chemotherapy ends; target hemoglobin level < 10 g/dL |

| 2008 CMS National Coverage Decisions |

Reduce reimbursement for ESAs when achieved hemoglobin level > 13 g/dL unless ESA dose decreased by 25%. No reimbursement if hemoglobin level > 13 g/dL. Lowers maximal ESA billable monthly dose to 400,000 Units. |

None |

| Advisory committee findings (US/Europe/Canada) | ||

| September 2007 (ODAC, Cardiorenal Drug & Drug Safety/ Risk Management Advisory Committees) |

No specific target hemoglobin levels were recommended (September 2007—Cardiorenal Drug & Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committees) |

FDA-approved labeling should state that ESAs not indicated for use in tumor types with adverse safety signals in clinical trials (breast, head and neck, and non–small cell lung cancer); marketing authorization should be contingent upon additional restrictions in product labeling and/or additional trials (May 2007 ODAC) |

| May 2008 (ODAC) | - | ESA indication should be modified to include statements that ESAs should not be used in patients receiving potentially curative treatments or in patients with specific tumor types with adverse safety signals in clinical trials (breast, head and neck, and non–small cell lung cancer) (May 2008) |

| October 2010 (FDA) | No additional changes or restrictions. | - |

| September 2007 (European Pharmacovigilance Working Party) |

ESAs are for treatment of symptomatic anemia, with target hemoglobin level range of 10–12 g/dL. |

ESAs are for treatment of symptomatic anemia, with target hemoglobin level range of 10–12 g/dL |

| January 2008 (Committee for Medicinal Products from Human Use) |

ESAs are indicated for treatment of symptomatic anemia associated with CKD or chemotherapy; target hemoglobin levels of 10–12 g/dL; avoid achieving hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL |

ESAs are indicated for treatment of symptomatic anemia associated with CKD or chemotherapy; target hemoglobin levels of 1012 g/dL; avoid achieving hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL |

| May 2008 (EMA’s Scientific Advisory Group on Oncology) |

No change | Issues a recommendation that ESA manufacturers should revise the package labels and indicate that in some clinical situations, transfusions should be the preferred method for correcting anemia in cancer patients. The decision should be based on risk–benefit assessment with consideration of clinical context, tumor type, stage, degree of anemia, life expectancy, and patient preference. |

| June 2008 (Committee for Medicinal Products from Human Use Pharmacovigilance Working Party) |

- | Benefits of ESAs continue to outweigh risks for chemotherapy-related anemia; however, for cancer patients with reasonably long life-expectancies, benefits of using ESAs do not outweigh tumor progression and mortality risks and chemotherapy-related anemia should be corrected with blood transfusions; overall, decisions to administer ESAs should be based on informed benefit–risk assessments, considering tumor type and stage, anemia severity, life expectancy, treatment environment, and patient preferences |

| June 2008 (Canadian Association for Drug and Technology in Health) |

Hemoglobin target levels of 9–10.5 g/dL were the least costly and second-most-effective option. Intermediate hemoglobin targets (11 g/dL) produced the largest quality-adjusted life years at incremental cost of Can$25,000 per patient lifetime versus low hemoglobin targets and were recommended. |

- |

| June 2009 (Canadian Association for Drug and Technology in Health) |

- | ESA administration for chemotherapy-associated anemia improved QOL and decreased transfusions; increased mortality/ adverse event risks; and was associated with cost-utility ratios exceeding accepted standards. Regulatory agencies should review ESA recommendations for cancer patients, taking into consideration revised safety and effectiveness assessments. |

| Manufacturer notifications to patients | ||

| Patient Medication Guides US (August 2008) |

What is themost important information I should know about ESAs? Using ESAs can lead to death or other serious side effects. You may get serious heart problems such as heart attack, stroke, heart failure, and may die sooner if you are treated with ESAs to a hemoglobin level above 12 g/dL. You may get blood clots at any time while taking ESAs. |

What is the most important information I should know about ESAs? Using ESAs can lead to death or other serious side effects. You may get serious heart problems such as heart attack, stroke, heart failure, and may die sooner if you are treated with ESAs to a hemoglobin level above 12 g/dL. You may get blood clots at any time while taking ESAs. ESAs do not improve the symptoms of anemia, QOL, fatigue, or well-being for patients with cancer. Your tumor may grow faster and you may die sooner when ESAs are used experimentally to try to raise your hemoglobin beyond the amount needed to avoid red blood cell transfusion or given to patients who are not getting strong doses of chemotherapy. It is not known whether these risks exist when ESAs are given according to FDA-approved directions for use. |

| Patient Medication Guide US (June 2011) |

You may get serious heart problems such as heart attack, stroke, heart failure, and may die sooner if you are treated with ESAs to reach a normal or near-normal hemoglobin level. You may get blood clots at any time while taking ESAs. |

- |

| European Product Assessment Report Summary for the Public (April 2009) |

If you have chronic renal failure, there is an increased risk of serious problems with your heart or blood vessels (cardiovascular events) if your hemoglobin is kept too high. |

If you are a cancer patient, you should be aware that ESAsmay act as a blood cell growth factor and in some circumstances may have a negative impact on your cancer. Depending on your individual situation, a blood transfusion may be preferable. Please discuss this with your doctor. |

| Consumer Information included in the Product Monograph for ESAs in Canada (January 2009) |

If your hemoglobin is kept too high, you have an increased risk of heart attack, heart failure, stroke, blood clots, and death. Your doctor should try and keep your hemoglobin levels between 10 and 12 g/dL. |

If you are a cancer patient and your hemoglobin is kept at > 12 g/dL, your tumor may grow faster and you have an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, blood clots, and death. Your doctor should use the lowest ESA dose to avoid transfusions. In some instances, red blood cell transfusions should be the preferred option. |

Abbreviations: ASCO/ASH, American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology; CHMP, Committee for Medical Products for Human Use; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CMS, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; dL, deciliter; EMA, European Medicines Agency; EORTC, European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; g, gram; KDOQI, KDQI: National Kidney Foundation-Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Improvement; L, liter; MHRA, Medicines and Health Regulatory Authority; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; ODAC, Oncologic Drug Advisory Committee; QOL, quality of life; RADAR, Research on Adverse Drug events and Reports; REMS, Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy; US, United States; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Methods

Data sources included reports from regulatory agencies, product manufacturers, and meta-analyses identified by Ovid and Cochrane searches (search terms: ESAs, meta-analysis, guidelines [2007 to May 2012]). Clinical trials and database studies cited in regulatory documents were reviewed.

Results

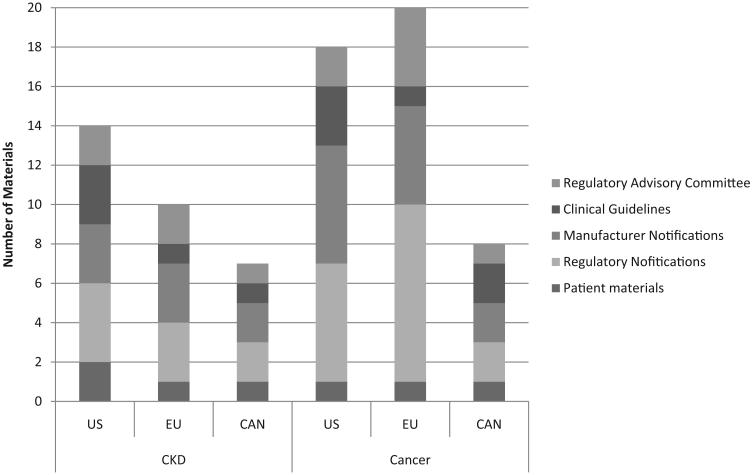

Among 75 abstracts identifying guidelines or meta-analyses, 18 were included. Studies without primary data were excluded. Sixteen regulatory documents, 16 phase III clinical trials, 13 regulatory agency advisory committee materials, and 1 database study cited in regulatory documents were reviewed (▶Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Data sources, 2007–2011, by region. CAN, Canada; CKD, chronic kidney disease; EU, European Union; US, United States.

Cancer

Meta-analyses and guidelines identified decreased transfusions when cancer patients with chemotherapy-associated anemia received ESAs.6-9 Quality of life benefit was reported in the Canadian review but not in other overviews.10 Seven phase III trials identified mortality and/or tumor progression risks when chemotherapy- or radiation therapy-treated cancer patients received ESAs; one trial identified mortality risks when cancer patients not receiving chemotherapy received ESA darbepoetin.6 One meta-analysis identified a nonsignificant 1.03-fold higher relative survival benefit when cancer patients received ESAs (p > 0.05).7 Three subsequent meta-analyses identified statistically significant 1.10-fold, 1.15-fold, and 1.17-fold mortality risks, and three meta-analyses identified statistically significant 1.57-fold, 1.67-fold, and 1.69-fold VTE risks when cancer patients received ESAs (p < 0.05 for each study).6,8-10

United States

In 2007, FDA statisticians concluded that quality of life claims for ESA-treated cancer patients were invalid.11 FDA’s Oncology Drug Advisory Committee (ODAC) warned against administering ESAs to breast, head, and neck, and non–small cell lung cancer patients because of tumor promotion concerns.12 American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology (ASCO/ASH) guidelines recommended administering ESAs to patients with chemotherapy-associated anemia and hemoglobin levels < 10 g/dL, targeting 12 g/dL hemoglobin levels, highlighting mortality concerns at higher hemoglobin levels.13 Black Box warnings described VTE, cardiovascular, and mortality risks with ESA treatment of chemotherapy-associated anemia with target hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL.11 Revised labels identified cancer progression/mortality risks among lymphoid and non–small cell lung cancer patients receiving ESAs targeted to hemoglobin levels more than 12 g/dL.

In 2008, ODAC warned that ESAs should not be administered to cancer patients receiving potentially curative chemotherapy.14,15 Medication guides warned cancer patients that ESAs can result in death or other serious toxicities; heart attack, stroke, heart failure, and early death may occur with ESA administration to hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL; blood clots may occur at any hemoglobin level or ESA dose; ESAs do not improve quality of life; tumors may grow faster and death occur sooner with ESAs targeting high hemoglobin levels.16 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines advised that ESAs were indicated to prevent transfusions among cancer patients receiving palliative, but not curatively intended, chemotherapy.17

In 2010, ESA manufacturers implemented a Risk Evaluation Mitigation System.18 ASCO/ASH guidelines advised that chemotherapy-associated anemia patients with hemoglobin levels < 10 g/dL should be informed of ESA risks and benefits; no target hemoglobin level was recommended.19

Europe

In 2007, European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs) warned against achieving hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL because of toxicity concerns. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) advised that for cancer patients with long life expectancies, risks may outweigh benefits because ESAs may stimulate tumor growth.20 EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) concluded that ESA effects on survival of chemotherapy-treated cancer patients were indeterminant; ESA benefits outweighed risks for chemotherapy-treated cancer patients; symptomatic cancer patients with chemotherapy-associated anemia should receive ESAs targeting hemoglobin levels between 10 and 12 g/dL.20 EMA’s Scientific Advisory Group on Oncology recommended individualized decisions.21

In 2008, after EMAs’ CHMP reviewed a meta-analysis and one clinical trial identifying mortality and VTE risks with ESA administration to cancer patients, they warned of tumor progression, venous thromboembolism, and mortality risks with ESAs; benefits continued to outweigh risks among chemotherapy-associated anemia patients, except for patients with long life expectancy.22 One month later, after reviewing two additional trial reports, CHMP reported tumor progression, progression-free survival, and mortality risks among cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and ESAs.22 A guidance from the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence highlighted uncertain effects of ESAs on survival, based on trials reported prior to 2005, and cost-effectiveness estimates greater than generally accepted values.23

In 2009, CHMP reviewed the 2009 Cochrane meta-analysis and warned of risks of mortality with ESA administration to cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. This warning was added to product labels in 2010.

Canada

In 2007, Canada Health reported that ESAs were not indicated for cancer patients not receiving chemotherapy; tumor progression occurred among head and neck cancer patients receiving radiation therapy with target hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL; increased mortality occurred among breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy with target hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL. Several trials identified venous thromboembolism, cancer progression, and mortality risks with ESAs.24

In 2009, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) reported a meta-analysis of chemotherapy-associated anemia patients identifying quality of life and transfusion benefits with ESAs; mortality, VTE, and other toxicity risks; and cost-utility ratios exceeding generally accepted standards.25

Chronic Kidney Disease

Three trials reported prior to 2007 found no survival/cardiovascular benefits and increased toxicity with ESAs targeted to high versus low hemoglobin target levels.1,26,27 One trial included ESA-treated nondialysis CKD patients and identified a statistically significant 1.34-fold higher relative risks (17.5 vs. 13.5%) for death, acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure hospitalization, or stroke with ESA treatment targeted to higher target hemoglobin levels.26 Secondary analyses identified ESA nonresponse as a toxicity indicator.28 Another trial of nondialysis CKD patients demonstrated a statistically nonsignificant 1.58-fold increase in cardiovascular risks in high target hemoglobin groups.27 A 2009 trial evaluating nondialysis CKD patients with type 2 diabetes receiving darbepoetin targeted to near normal hemoglobin levels versus rescue therapy for moderately severe anemia found no reduction in death/cardiovascular events and death/end-stage renal disease but 92% higher relative risks of stroke (5.0 vs. 2.6%; p < 0.05).2 Among CKD patients, one meta-analysis found no mortality difference with ESAs targeting higher hemoglobin levels.29 Another found a statistically significant 1.17-fold increased mortality risk with higher target hemoglobin levels.30 A Medicare analysis of hemodialysis patients with diabetes found mortality risks with 30,000 versus 15,000 Units of epoetin/wk of 9 and 13% between 45,000 and 15,000 U/wk (p < 0.05).31

In 2011, draft guidelines from the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes initiative of the National Kidney Foundation recommended that decisions to initiate ESAs for CKD patients should consider potential benefits of reducing blood transfusions and anemia-related symptoms against risks of harm—including stroke, vascular access loss, and hypertension (grade 1B recommendation). Great caution is urged when administering ESAs to CKD patients with malignancies or stroke (grade 1C). For CKD patients not on dialysis, with hemoglobin levels ≥ 10 g/dL, ESAs are not recommended (grade 2D); if the hemoglobin level is < 10 g/dL, ESA initiation should be based on rate of hemoglobin fall, risk of needing transfusion, risks of ESA therapy, and presence of anemia-related symptoms (grade 2C). For CKD patients on hemodialysis, ESAs should be initiated with hemoglobin levels between 9 and 10 g/dL (grade 2B), although some patients may benefit with improved quality of life if ESAs are begun at higher hemoglobin levels (not graded). ESAs should not be used to maintain hemoglobin levels > 11.5 g/dL (grade 2C) or to intentionally increase hemoglobin levels more than 13 g/dL.

United States

In 2007, the National Kidney Foundation-Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Improvement (KDOQI) group recommended target hemoglobin levels of 11 to 12 g/dL based on quality of life and transfusion benefits but avoiding hemoglobin levels > 13 g/dL.32 FDA statisticians concluded that based on under-development guidelines, quality of life claims were invalid and recommended that most of these claims be removed from labels.11

In 2008, the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory and Drug Safety/Risk Management Advisory Committees concluded that CKD patients should not receive large ESA doses and should avoid achieving hemoglobin levels > 13 g/dL.33 Black Box warnings describe death/cardiovascular event risks with ESAs targeting hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL. Clinicians were advised to administer the lowest ESA doses needed to avoid transfusions.14 Product labels removed quality of life claims with the exception of exercise tolerance and patient-reported physical function, recommended target hemoglobin levels of 10 to 12 g/dL, and warned against administering high ESA doses. Patients were advised that ESAs can lead to death/serious toxicities; heart attack, stroke, heart failure, and early death may occur if ESAs administration results in hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL; blood clots may develop.34

In 2010, the FDA’s Cardiovascular and Renal Advisory Committee recommended no additional restrictions. In 2011, the FDA warned of cerebrovascular, cardiovascular, or mortality risks associated with ESA administration to non-dialysis CKD patients or when ESAs are administered to CKD patients targeting 11 g/dL or greater hemoglobin levels.11,35,36 Boxed warnings stated that four trials found greater death, serious cardiovascular events, and stroke risks with ESA administration targeting hemoglobin levels > 13 g/dL; dosing should be individualized to achieve and maintain hemoglobin levels between 10 and 12 g/dL.37

In 2011, public health advisories indicated that trials identified death, cardiovascular, and stroke risks with ESAs administered targeting hemoglobin levels > 11 g/dL and that no trial identified target hemoglobin levels, dose, or dosing strategy that did not increase risks.38 Revised labels recommended that for CKD patients on dialysis, ESAs should be initiated when hemoglobin levels are < 10 g/dL and to administer the lowest ESA dosages sufficient to reduce red blood cell transfusions.38 For CKD patients not on dialysis, labels recommend ESA treatment with hemoglobin levels < 10 g/dL if the rate of hemoglobin decline indicates transfusion likelihood and treatment goals are to reduce transfusion-related risks.38 FDA’s Oncologic Drug Advisory Committee reviewed data on peginesatide, a synthetic erythropoietin receptor–activating peptide.3 Structurally, peginesatide is a pegylated dimeric peptide (allowing for sustained activity and once-per-month dosing). Peginesatide bears no homology to erythropoietin, hence any antibodies that form are not cross-reactive. At the FDA Committee meeting, data were presented on two phase III trials for nondialysis CKD patients not on an ESA who received subcutaneous monthly peginesatide (n = 656 patients) versus every 2-week dosing of darbepoetin (n = 327 patients). Primary analyses showed that patients who received peginesatide at one of two doses (0.025 mg/kg/4 weeks or 0.04 mg/kg/4 weeks) had similar hemoglobin levels and those who received darbepoetin had similar hemoglobin levels (11.5,11.7, and 11.4, respectively) and similar mean hemoglobin changes (0.08 with 0.025 mg/kg dose peginesatide and 0.29 with 0.04 mg/kg peginesatide vs. darbepoetin). Safety analyses identified greater rates of adverse events, serious adverse events, deaths, adverse events ≥ grade 3, and adverse events leading to permanent discontinuation of peginesatide (▶Table 2). For CKD patients who participated in two phase III trials for dialysis CKD patients (intravenous epoetin alfa administered one to three times per week as comparator in the United States and intravenous or subcutaneous epoetin alfa or β one to three times per week as comparator in the United States and Europe),3 primary analyses showed that patients who received peginesatide (n = 1066) versus epoetin (n = 542 patients) had similar hemoglobin levels at weeks 29 to 36 (11.1 vs. 11.3, respectively) and similar mean hemoglobin changes (− 0.24 vs. − 0.09). In these studies, similar proportions of patients experienced adverse events, serious adverse events, deaths, adverse events ≥ grade 3, and adverse events leading to drug discontinuation (▶Table 2).

Table 2.

Adverse events in phase III clinical trials of peginesatide versus epoetin or darbepoetin

| Peginesatide (dialysis) | Epoetin (dialysis) | Peginesatide (nondialysis) |

Darbepoetin (nondialysis) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 1066 | 542 | 656 | 327 |

| Dosing | 0.04–0.16 mg/kg based on prior ESA dose sq or iv every 28 days |

Prior maintenance dose—sq or iv |

0.025 and 0.04 mg/kg sq every 4 weeks |

0.75 mcg/kg sq every 2 weeks |

| Efficacy—mean (SD) hemoglobin (g/dL) (week: 29–36) |

11.1 (0.04) | 11.3 (0.05) | 11.1 (0.05) | 11.1 (0.06) |

| Mean hemoglobin (SD)(g/dL) —baseline |

11.3 (0.02) | 11.3 (0.03) | 11.2 (0.02) | 11.2 (0.03) |

| Adverse events, % | 95 | 93 | 94 | 91 |

| Serious adverse events, % | 54 | 57 | 49 | 43 |

| Deaths, % | 11 | 12 | 9 | 7 |

| Adverse events ≥ grade 3, % | 52 | 53 | 47 | 40 |

| Adverse events resulting in discontinuing ESA, % |

13 | 12 | 13 | 10 |

Abbreviations: dL, deciliter; ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; g, gram; iv, intravenous; kg, kilogram; mg, milligram; SD, standard deviation; sq, subcutaneous.

Source: Adapted from ODAC meeting materials, December 2011.3

In 2012, the FDA granted approval for peginesatide as an ESA for treating anemia due to CKD in adult patients on dialysis.

Europe

In 2007, European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs) warned against achieving hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL when ESAs were administered to CKD patients.

In 2008, Europe’s Pharmacovigilance Working Party recommended administering ESAs to CKD patients with symptomatic anemia, targeting hemoglobin levels between 10 and 12 g/dL. EMA’s CHMP recommended avoiding hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL.21 The Anemia Working Group of the European Renal Best Practice Work Group and the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes endorsed KDOQI guidelines.

In 2009, revised EPARs warn of risks of serious problems with heart or blood vessels if high hemoglobin levels are maintained.39

In 2010, the Anemia Working Group of the European Renal Best Practices recommended target hemoglobin values of 11 to 12 g/dL among CKD patients and that ESA doses required to achieve the target hemoglobin should be considered.40 Caution was advised when administering ESAs to patients with type 2 diabetes not undergoing dialysis.

In 2011, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence reported stroke, hypertension, and cardiovascular risks among nondialysis CKD patients and vascular access thrombosis risks among dialysis CKD patients with hemoglobin target levels of 12 g/dL versus lower levels.41 ESA initiation was recommended at hemoglobin levels < 11 g/dL or if symptoms were present, with target hemoglobin levels of 10 to 12 g/dL. Targeting hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL among nondialysis CKD patients was not cost-effective, whereas cost-effectiveness information on dialysis CKD patients was unavailable.41

Canada

In 2007, revised labels warn that maintaining high hemoglobin levels resulted in risks of heart attack, heart failure, stroke, blood clots, and death and recommended maintaining hemoglobin levels between 10 and 12 g/dL.24 Canadian Society of Nephrology guidelines recommend target hemoglobin levels of 10 to 12 g/dL, citing excess mortality with higher hemoglobin targets.42

In 2008, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health concluded that ESAs improved quality of life and decreased cardiovascular mortality.43 Targeting higher hemoglobin levels increased hospitalization, adverse events, and vascular access thrombosis. A hemoglobin target of 11 g/dL resulted in the largest quality-adjusted life years benefit (incremental costs of Can$25,000) compared with low target hemoglobin levels among CKD patients and was recommended.43

Utilization

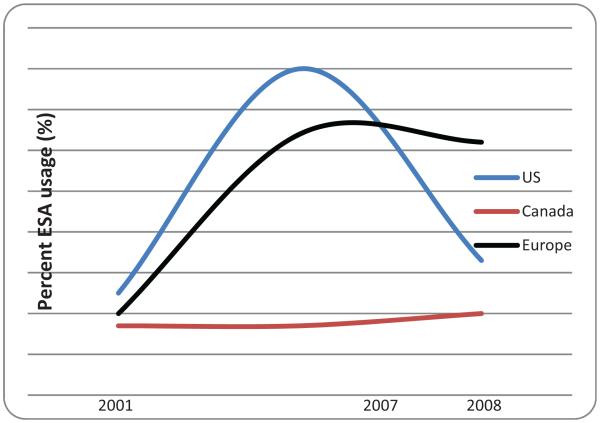

Patterns of ESA use have changed with ESAs. Among cancer patients receiving chemotherapy, ESA utilization increased 3.5-fold from 2000–2001 to 2006–2007 in the United States and Europe, and the frequency of cancer patients on chemotherapy receiving ESAs increased in the United States and Europe but not in Canada. Since 2007, ESA use among cancer patients receiving chemotherapy decreased in the United States (by 60%) compared with Europe (3% decrease) or Canada (3% increase). In 2008, among cancer patients with chemotherapy-induced anemia, rates of ESA use were 61% in Europe, 31% in the United States, and 20% in Canada (▶Fig. 2). In comparison, in 2007, among cancer patients with chemotherapy-induced anemia, rates of ESA use had been 64% in Europe, 80% in the United States, and 16% in Canada.

Fig. 2.

Erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) usage among cancer patients with chemotherapy-associated anemia, 2001, 2007, and 2008. US, United States. (Adapted from Bennett et al 2010.44)

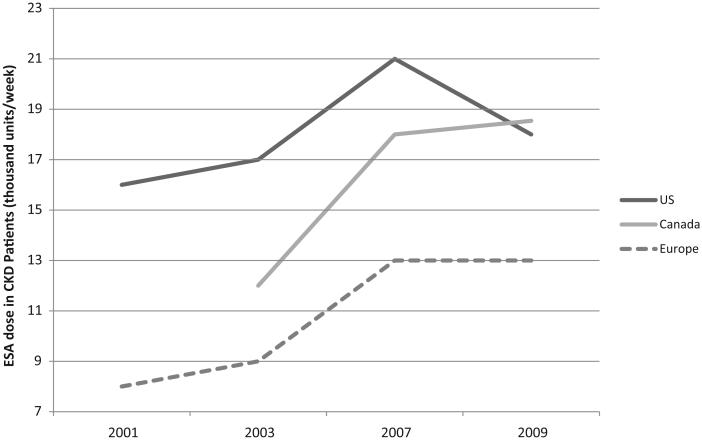

For CKD patients receiving hemodialysis, per-person ESA utilization and hemoglobin levels increased from 2000 to 2007.45 Between 2007 and 2009, per-patient ESA utilization for CKD patients decreased in the CKD setting in the United States (by 20%) but not in Canada (3% increase) or Europe (no change) (▶Fig. 3). In 2009, mean weekly erythropoietin doses for CKD patients on hemodialysis were 18,000 Units in Canada, 17,500 Units in the United States, and 13,000 Units in Europe. In comparison, in 2007, mean weekly erythropoietin doses for CKD patients on hemodialysis had been 17,500 Units in Canada, 21,000 Units in the United States, and 13,000 Units in Europe. Between 2011 and 2012, ESA use in the CKD setting for patients on hemodialysis decreased by 18%, while rates of transfusions increased by 22%. (Reimbursement for ESA use among CKD patients with hemodialysis in the United States was included as a bundled payment).

Fig. 3.

Erythropoietin utilization among chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients on hemodialysis. ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; US, United States.

Utilization data for CKD patients not on dialysis are available only from the United States. Since 2005, ESA use among nondialysis CKD patients declined from 60 to 46%, and mean monthly dose among nondialysis CKD patients who received ESAs declined 25%, with the largest decline beginning in 2007.46 The mean hemoglobin level in ESA-treated CKD patients not on dialysis declined from 11.5 to 10.6 g/dL. The percent of treated nondialysis CKD patients with hemoglobin levels > 12 g/dL decreased from 27 to 12%, and mean doses declined from 173 to 111 mcg/mo.

Discussion

Assessments of ESA safety and efficacy has undergone extensive revision. Initial ESA dosing and scheduling recommendations were based on small trials with narrow selection criteria and short follow-up.47 Initial recognition of mortality risks were identified in a phase III trial for CKD patients in 1998 and among two phase III trials of persons with cancer in 2003.1,4,5 Clinical trials with an active comparator for CKD patients and meta-analyses of clinical trials with cancer patients confirmed these safety concerns.2,6,8,10,30,41-43,48

In oncology in the United States, ESA approval is for chemotherapy patients not receiving potentially curative therapy. In Europe and Canada, regulatory approvals are less restrictive for cancer patients with symptomatic chemotherapy-associated anemia. For CKD, safety assessments are restrictive in the United States.2 In the United States, analysis of Medicare claims data for CKD patients on dialysis identifying mortality risks with higher ESA doses supported the FDA’s 2011 advisory to remove target hemoglobin levels.2,31,49 ESA labels in Europe and Canada for CKD patients include trigger and target hemoglobin levels.40,42 In 2011, ESA labels in the United States discouraged ESAs for most CKD patients not receiving hemodialysis. In Europe, this restriction is primarily for CKD patients with type 2 diabetes not receiving hemodialysis; no similar restrictions are noted in Canada.38,50,51

Conclusion

Reassessments of ESAs have occurred internationally, although responses to these reassessments vary. The result is marked decrease in ESA use in the United States but not in Canada or Europe.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This manuscript was supported by funding from a grant from the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA 102713–01), the Centers for Economic Excellence program of the state of South Carolina, and Doris Levkoff Meddin Center for Medication Safety, and a grant from the NIH (1R01CA165609-01A1), SONAR TKI.

Footnotes

Issue Theme Adverse Effects of Drugs on Hemostasis and Thrombosis; Guest Editors, Hau C. Kwaan, MD, FRCP, and Charles L. Bennett, MD, PhD, MPP

Conflict of Interest

Samuel Silver, MD, PhD: Consults for Amgen and 3M; David Goldsmith, MD: Speaking/Consulting Honoraria and Lecture Fees from Amgen, Roche, Sandoz, Takeda.

References

- 1.Besarab A, Bolton WK, Browne JK, et al. The effects of normal as compared with low hematocrit values in patients with cardiac disease who are receiving hemodialysis and epoetin. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(9):584–590. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808273390903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfeffer M, Burdmann EA, Cooper DE, et al. A trial of darbepoetin-alfa in type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FDA Briefing Document on Peginesatide for the Oncologic Drug Advisory Committee (ODAC) December 7, 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/advisorycommittees/committees-meetingmaterials/drugs/oncologicdrugsadvisorycommittee/ucm282292.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2012.

- 4.Leyland-Jones B; BEST Investigators and Study Group Breast cancer trial with erythropoietin terminated unexpectedly. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(8):459–460. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(03)01163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henke M, Laszig R, Rübe C, et al. Erythropoietin to treat head and neck cancer patients with anaemia undergoing radiotherapy: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;362(9392):1255–1260. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett CL, Silver SM, Djulbegovic B, et al. Venous thromboembolism and mortality associated with recombinant erythropoietin and darbepoetin administration for the treatment of cancer-associated anemia. JAMA. 2008;299(8):914–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.8.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilson J, Yao GL, Raftery J, et al. A systematic review and economic evaluation of epoetin alpha, epoetin beta and darbepoetin alpha in anaemia associated with cancer, especially that attributable to cancer treatment. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11(13):1–202. doi: 10.3310/hta11130. iii-iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bohlius J, Schmidlin K, Brillant C, et al. Recombinant human erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and mortality in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9674):1532–1542. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60502-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glaspy J, Crawford J, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in oncology: a study-level meta-analysis of survival and other safety outcomes. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(2):301–315. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonelli M, Hemmelgarn B, Reiman T, et al. Benefits and harms of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anemia related to cancer: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2009;180(11):E62–E71. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Epogen package insert Amgen, Inc. 2007 Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2007/103234s5158ppi.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 12.FDA Advisory Committee Briefing Document Reassessment of the risks of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) administered for the treatment of anemia associated with chronic renal failure. Joint meeting of the Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Committee. September 11, 2007. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/07/briefing/2007-4315b1-01-FDA.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 13.Rizzo JD, Somerfield MR, Hagerty KL, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology; American Society of Hematology. Use of epoetin and darbepoetin in patients with cancer: 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(1):132–149. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meeting Briefing Document ODAC Epoetin alfa and darbepoetin. 2008 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/briefing/2008-4345b2-05-amgen.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 15.Epogen FDA (Epoetin alfa) For injection package insert. 2008 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2008/103234s5195sPI.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 16.Patient Medication Guide FDA Epogen (Epoetin alfa) 2008 Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/103234s5195Medguide.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 17.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: cancer and chemotherapy–induced anemia. V.1.2009. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/anemia.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 18.US FDA FDA approves a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) to ensure the safe use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) 2010 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/CDER/ucm200847.htm. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 19.Rizzo JD, Brouwers M, Hurley P, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology; American Society of Hematology. American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Society of Hematology clinical practice guideline update on the use of epoetin and darbepoetin in adult patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(33):4996–5010. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Medicines Agency Public Statement. Epoetins and the risk of tumour growth progression and thromboembolic events in cancer patients and cardiovascular risks in patients with chronic kidney disease. October 2007. Available at: http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/press/pus/49618807en.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 21.Aapro M, Spivak JL. Update on erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and clinical trials in oncology. Oncologist. 2009;14(Suppl 1):6–15. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S1-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Conclusions from the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) – Review of safety of erythropoiesis stimulating agents (ESAs) in patients with anaemia resulting from renal insufficiency or chemotherapy in cancer patients. 2008 Available at: http://www.mhra.gov.uk/home/groups/pl-p/documents/websiteresources/con023076.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 23.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Technology Appraisal Guidance-Epoetin Alfa, Epoetin Beta, and Dar-boepoetin Alfa for Cancer Treatment Induced Anaemia. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE); London, UK: 2008. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/TA142Guidance.pdf. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health Canada Important safety information and new prescribing information for the erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, aranesp (dar-bepoetin alfa) and EPREX (epoetin alfa) 2007 Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/medeff/advisories-avis/public/2007/aranesp_eprex_pc-cp-eng.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonelli M, Lloyd A, Lee H, et al. Overview of systematic review and economic evaluation of erythropoiesis stimulating agents for anemia of cancer or of chemotherapy (technology overview number 51) Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; Ottawa: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh AK, Szczech L, Tang KL, et al. CHOIR Investigators. Correction of anemia with epoetin alfa in chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2085–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drüeke TB, Locatelli F, Clyne N, et al. CREATE Investigators. Normalization of hemoglobin level in patients with chronic kidney disease and anemia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(20):2071–2084. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cotter DJ, Stefanik K, Zhang Y, Thamer M, Scharfstein D, Kaufman J. Hematocrit was not validated as a surrogate end point for survival among epoetin-treated hemodialysis patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(10):1086–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.KDOQI KDOQI clinical practice guideline and clinical practice recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease: 2007 Update of Hemoglobin Target. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(3):471–530. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phrommintikul A, Haas SJ, Elsik M, Krum H. Mortality and target haemoglobin concentrations in anaemic patients with chronic kidney disease treated with erythropoietin: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007;369(9559):381–388. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Thamer M, Kaufman JS, Cotter DJ, Hernán MA. High doses of epoetin do not lower mortality and cardiovascular risk among elderly hemodialysis patients with diabetes. Kidney Int. 2011;80(6):663–669. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.KDOQI KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline and Clinical Practice Recommendations for anemia in chronic kidney disease: 2007 update of hemoglobin target. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50(3):471–530. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee meeting. 2008 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/08/transcripts/2008-4390t1-part1.PDF. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 34.Epogen FDA (Epoetin alfa) For injection package insert. November 19, 2008. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2008/103234s5195sPI.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 35.US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee meeting. 2010 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/CardiovascularandRenalDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM238530.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 36.US FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Cardiovascular and Renal Drugs Advisory Committee meeting. 2011 Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/Drugs/CardiovascularandRenalDrugsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM256586.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 37.Epogen package insert FDA 2010 Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2010/103234s5199lbl.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 38.Epogen/Procrit label June 24, 2011. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103234Orig1s5166_103234Orig1s5266lbl.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012.

- 39.EMA summary of product characteristics Abseamed (Epoetin alfa) October 12, 2009. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Procedural_steps_taken_and_scientific_information_after_authorisation/human/000726/WC500028289.pdf. Accessed April 4, 2012.

- 40.Locatelli F, Aljama P, Canaud B, et al. Target haemoglobin to aim for with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents: a position statement by ERBP following publication of the Trial to reduce cardiovascular events with Aranesp therapy (TREAT) study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(9):2846–2850. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Appraisal Consultation Document – Erythropoietin for anaemia induced by cancer treatment. 2011 http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/index.jsp?action=article&r=true&o=34940. Accessed May 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manns BJ, White CT, Madore F, et al. Introduction to the Canadian Society of Nephrology clinical practice guidelines for the management of anemia associated with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;110:S1–S3. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Report T Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health. Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents for anemia of chronic kidney disease: systematic review and economic evaluation. 2009 Available at: http://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/H0468_Erythropoiesis-stimulating_agents_tr_e.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bennett CL, McKoy JM, Henke M, et al. Reassessments of ESAs for cancer treatment in the US and Europe. Oncology (Williston Park) 2010;24(3):260–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McFarlane PA, Pisoni RL, Eichleay MA, Wald R, Port FK, Mendelssohn D. International trends in erythropoietin use and hemoglobin levels in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2010;78(2):215–223. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regidor D, McClellan WM, Kewalramani R, Sharma A, Bradbury BD. Changes in erythropoiesis-stimulating agent (ESA) dosing and haemoglobin levels in US non-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients between 2005 and 2009. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1583–1591. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldsmith DJ, Covic AC. Significant further evidence to bolster the link between epoetin and strokes in chronic kidney disease and cancer. Kidney Int. 2011;80(3):237–239. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Palmer SC, Navaneethan SD, Craig JC, et al. Meta-analysis: erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(1):23–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-1-201007060-00252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Medical Technology and Practice Patterns Institute (MTPPI) Citizen’s petition. 2009 Available at: http://www.mtppi.org/new/FDA-2009-P-0426-0001.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cancer Care Ontario Epoetin alfa (Eprex) Janseen Ortho Formulary. Available at: http://www.cancercare.on.ca/search/default.aspx?q=formulary%20erythropoietin&type=0,6-76,6-40484|-1, 1377-78. Accessed May 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.EMA Manufacturer’s label. Annex II. 2007 Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000726/WC500028282.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Medical Technology and Practice Patterns Institute (MTPPI) Citizen’s petition. 2009 Available at: http://www.mtppi.org/new/FDA-2009-P-0426-0001.pdf. Accessed May 2, 2012. [Google Scholar]