Abstract

Docetaxel is the first-line standard treatment for castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). However, relapse eventually occurs due to the development of resistance to docetaxel. In order to unravel the mechanism of acquired docetaxel resistance, we established docetaxel-resistant prostate cancer cells, TaxR, from castration resistant C4-2B prostate cancer cells. The IC50 for docetaxel in TaxR cells was about 70-fold higher than parental C4-2B cells. Global gene expression analysis revealed alteration of expression of a total of 1604 genes with 52% being upregulated and 48% downregulated. ABCB1, which belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, was identified among the top upregulated genes in TaxR cells. The role of ABCB1 in the development of docetaxel resistance was examined. Knockdown of ABCB1 expression by its specific shRNA or inhibitor resensitized docetaxel resistant TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment by enhancing apoptotic cell death. Furthermore, we identified that apigenin, a natural product of the flavone family, inhibits ABCB1 expression and resensitizes docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cells to docetaxel treatment. Collectively, these results suggest that overexpression of ABCB1 mediates acquired docetaxel resistance and targeting ABCB1 expression could be potential approach to resensitize docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cells to docetaxel treatment.

Keywords: docetaxel, prostate cancer, ABCB1

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer and second most frequent cause of cancer related death among the men in the United States. Most of the prostate cancer patients will initially respond to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). However, almost all of them will relapse due to development of castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) (1, 2). Docetaxel is the first-line standard treatment for CRPC. Docetaxel is a cytotoxic antimicrotubule agent that binds to beta-tubulin and prevents microtubule depolymerization, resulting in inhibition of mitotic cell division which leads to apoptotic cell death (3). However, relapse eventually occurs due to the development of resistance to docetaxel.

The molecular mechanisms of the acquired docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer cells are incompletely understand. Studies to understand the underlying mechanisms of docetaxel resistance have uncovered several potential mechanisms of docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer (4, 5). Alterations of beta-tubulin isotypes, especially the increase in isotypes III and IV has been shown to be correlated with docetaxel resistance (6). Alterations of cell survival factors that inhibit chemotherapy induced apoptotic cell death are associated with docetaxel resistance (7). Several different groups have reported that overexpression of Bcl-2 (8) and induction of clusterin by pAkt (9, 10) are related to docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer. Aberrant activation of central transcriptional factors such as NF-kB also plays an important role in the development of resistance. Recent studies have shown that inhibition of NF-kB resensitizes docetaxel resistant PC-3 cells to taxane induced apoptosis (11). Furthermore, reduced intracellular drug concentration through alteration of multidrug resistant (MDR) genes is another mechanism associated with the acquired resistance to chemotherapy (12).

In order to further understand the molecular mechanisms of the acquired docetaxel resistance and explore potential therapeutic strategies for docetaxel resistant CRPC, we generated docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cells from castration resistant C4-2B prostate cancer cells. We identified ABCB1 gene upregulation as a common mechanism involved in acquired docetaxel resistance. In addition, we demonstrate that apigenin, a natural product of the flavone family, inhibits ABCB1 expression and resensitizes docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cells to docetaxel treatment by enhancing apoptotic cell death.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

DU145 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). All experiments with cell line were performed within 6 months of receipt from ATCC or resuscitation after cryopreservation. ATCC uses Short Tandem Repeat (STR) profiling for testing and authentication of cell lines. C4-2B cells were kindly provided and authenticated by Dr. Leland Chung, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA. The cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% complete fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 100 units/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin and maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. C4-2B cells were incubated with gradually increasing concentrations of docetaxel. Cells that survived the maximum concentration of docetaxel were stored for further analysis and referred to as TaxR cells. Parental C4-2B cells were passaged alongside the docetaxel treated cells as an appropriate control. Docetaxel resistant TaxR cells were maintained in 5 nM docetaxel-containing medium. Docetaxel (CAS#114977-28-5) was purchased from TSZ CHEM (Framingham, MA). Apigenin (CAS#520-36-5) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). Antibodies against ABCB1 and GAPDH were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA).

Plasmids and cell transfection

Lentivector based ABCB1 shRNA constructs were obtained from Open Biosystems. TaxR cells were transiently transfected with shRNA specific against ABCB1 or shGFP as vector control using Attractene transfection reagent (QIAGEN). TaxR shABCB1 and vector stable clones were selected with 2.0 μg/ml puromycin within 3 weeks after being transfected with ABCB1 shRNA or control vector and then maintained in culture medium containing 2.0 μg/ml puromycin.

Preparation of whole cell extracts

Cells were harvested, washed with PBS twice, and lysed in high-salt buffer (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 0.25 M NaCl, 0.1% NP-40) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Protein concentration was determined with Coomassie Plus protein assay kit (Piece, Rockford, IL).

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of cell protein extracts were loaded on 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking in 5% non-fat milk in 1×PBS/0.1% Tween-20 at room temperature for 1 hour, membranes were washed three times with 1×PBS/0.1% Tween-20. The membranes were incubated overnight with primary antibodies at 4°C. Proteins were visualized by enhanced chemi-luminescence kit (Millipore) after incubation with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) reagent. One microgram RNA was digested using RQ1 DNase (Promega, Madison, WI). The resulting product was reverse transcribed with random primers using Im-PromII Reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI). The newly synthesized cDNA was used to perform real-time PCR. The reaction mixture contained 4 μl cDNA template and 0.5 μM specific primers for ABCB1 (Forward: 5’-ATGCT CTGGC CTTCT GGATG GGA-3’; Reverse: 5’-ATGGC GATCC TCTGC TTCTG CCCAC-3’). GAPDH primers were used as an internal control. The expression levels of ABCB1 were normalized to GAPDH. The experiments were repeated three times with triplicates.

Cell growth assay

C4-2B and TaxR cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells per well. Cells were treated as indicated and total cell numbers were counted using Coulter cell counter.

Cell death ELISA

C4-2B and TaxR cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 1×105 cells per well and were treated as indicated. DNA fragmentation in the cytoplasmic fraction of cell lysates was determined using Cell Death Detection ELISA kit (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Apoptotic cell death was measured at 405 nm.

Clonogenic ability assay

C4-2B and TaxR cells were treated with DMSO or different doses of docetaxel for 6 hours. 1×103 cells were then plated in 100 mm dish for 14 days. The cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes and then stained with 0.5% crystal violet for 30 minutes, and the numbers of colonies were counted.

cDNA microarray analysis

Twenty-four hours after plating of 1×105 C4-2B and TaxR cells, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified with Eppendorf phase-lock-gel tube. RNA quality of all samples was tested by RNA electrophoresis to ensure RNA integrity. Samples were analyzed by the Genomics Shared Resource (UC Davis Medical Center, Sacramento) using the Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST array. Microarray data have been deposited at GEO with the accession number GSE47040.

Statistical analyses

All data are presented as means ± SD. Differences between multiple groups were determined using one-way ANOVA followed by the Scheffe procedure for comparison of means. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Development and characterization of a docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cell line

We previously demonstrated that docetaxel induces p53 phosphorylation in docetaxel sensitive LNCaP and C4-2B cells, but fails to induce p53 phosphorylation in docetaxel resistant DU145 cells (13). To further confirm these findings, we established a docetaxel resistant cell line, TaxR, from C4-2B cells by culturing C4-2B cells in docetaxel in a dose-escalation manner (starting from 0.1 nM). After 9-month selection, cells were able to divide freely in 5 nM docetaxel. To test the effect of docetaxel treatment on parental C4-2B and TaxR cell viability, cell growth assay was performed. Both cell lines were treated with increasing concentrations of docetaxel for 24 h. As shown in Fig 1A, C4-2B cells are sensitive to docetaxel treatment with an IC50 of 2 nM, while TaxR cells are much more resistant to docetaxel with an IC50 of 140 nM, about 70-fold increase over parental C4-2B cells. To determine whether docetaxel induces p53 phosphorylation in TaxR cells, TaxR cells and parental C4-2B cells were treated with increasing doses of docetaxel and cell lysates were isolated for Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig 1B, docetaxel treatment induces p53 phosphorylation in C4-2B cells, but not in TaxR cells, consistent with previous report that p53 phosphorylation is associated with docetaxel sensitivity in prostate cancer cells.

Figure 1. TaxR cells are more resistant to docetaxel than parental C4-2B cells.

Parental C4-2B cells and TaxR cells were treated with indicated concentrations of docetaxel in media containing complete FBS for 24hrs. (A) Cell growth assay. Results are expressed as % of treated cells relative to untreated cells. (B) Docetaxel induces phospho-p53 expression in C4-2B cells but not in TaxR cells. Whole cell lysates were collected and subjected to Western blot analysis using the indicated antibodies.

The effect of docetaxel on clonogenic ability of both C4-2B and TaxR cells was determined. The clonogenic ability of TaxR cells was significantly higher than that of parental C4-2B cells in response to docetaxel treatment (Fig 2A-B). To test the ability of docetaxel to induce apoptotic cell death in prostate cancer cells, C4-2B and TaxR cells exposed to 5 nM docetaxel for 48 h were examined by apoptosis-specific ELISA assay as described in Methods. Docetaxel at 5 nM concentration induced significant apoptotic cell death in parental C4-2B cells but had little effect on TaxR cells (Fig 2C-D).

Figure 2. Effects of docetaxel on clonogenic ability and apoptotic cell death in TaxR cells and C4-2B cells.

(A) Effects of docetaxel on clonogenic ability. C4-2B and TaxR cells were treated with docetaxel as indicated. After 6 hours treatment, 1000 cells were plated in 100mm dish in media containing complete FBS. Visible clones were formed after 3 weeks. (B) Numbers of colonies were counted. (C) Effects of docetaxel on apoptotic cell death. C4-2B and TaxR cells were treated with 5 nM docetaxel for 48 hours. Mono and oligo-nucleosomes of cytoplasmic fraction were analyzed by cell death detection ELISA. (D) Photographs of C4-2B and TaxR cells treated with 5 nM docetaxel were taken.

ABCB1 is overexpressed in TaxR cells

Several mechanisms have been proposed for docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer, such as alteration in beta-tubulin isotypes, reduced intracellular concentration of drug through alteration of MDR genes and alteration of cell survival factors and transcription factors (6-10). In order to identify genes responsible for docetaxel resistance in TaxR cells, global gene expression analysis by cDNA microarrays (approximately 28000 genes) was performed using mRNA from parental C4-2B and TaxR cells. Gene expression analysis revealed that a total of 1604 genes were altered in TaxR cells with 52% being upregulated and 48% downregulated. The 1604 genes that are altered in TaxR cells were compared to the public data base generated from docetaxel resistant DU145DR and Rv1DR cells (14). Only nine genes altered by docetaxel were found to be overlapping in the three gene data sets (Fig 3A). ABCB1, which belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, was identified among the top upregulated genes in TaxR cells, which is also among the nine overlapped genes in the three gene data sets. To verify microarray analysis, total RNAs were isolated from C4-2B and TaxR cells, and ABCB1 mRNA level was measured using specific primers by qRT-PCR. As shown in Fig 3B, ABCB1 mRNA was highly expressed in TaxR cells but was not detectable in parental C4-2B. ABCB1 protein expression was analyzed by Western blotting in whole cell extracts of parental C4-2B and TaxR cells. Fig 3C showed that ABCB1 was overexpressed in TaxR cells but was not detectable in parental C4-2B cells. These data suggested that ABCB1 is overexpressed in docetaxel resistant TaxR cells at both mRNA and protein levels.

Figure 3. ABCB1 is overexpressed in TaxR cells.

(A) Analysis of gene expression data sets. Genes with at least 1.2-fold increase (↑) and decrease (↓) in expression on comparison of parental C4-2B and TAXR cells are listed. (B) Real-time PCR analysis of ABCB1 mRNA in C4-2B and TaxR cells. (C) ABCB1 protein expression. ABCB1 expression was determined by Western blot analysis using antibody specific against ABCB1.

Downregulation of ABCB1 reverses docetaxel resistance

Having identified that ABCB1 is overexpressed in docetaxel resistant TaxR cells, we next tested whether overexpression of ABCB1 leads to docetaxel resistance in TaxR cells. As shown in Fig 4A, inhibition of ABCB1 expression by ABCB1 shRNA resensitized TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment. Fig 4B confirmed that ABCB1 protein expression was knocked down by ABCB1 shRNA. This observation was confirmed in another docetaxel resistant DU145-R cell line, in which knockdown of ABCB1 expression by ABCB1 shRNA reversed docetaxel resistance (Suppl. Fig 1). To further confirm that downregulation of ABCB1 could restore sensitivity to docetaxel, we established stable transfectant TaxR cells expressing ABCB1 shRNA. Two independent clones (clones No. 2 and No. 30) with ABCB1 downregulation were selected for further analysis (Fig 4C). As shown in Fig 4D, down regulation of ABCB1 increased the sensitivity of TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment. The IC50 of docetaxel was reduced from 140 nM (vector control of parental TaxR cells) to about 20 nM in both clone No. 2 and No.30. Furthermore, we used ABCB1 inhibitor, Elacridar, to test whether inhibition of ABCB1 activity reverses docetaxel resistance in TaxR cells. As shown in Fig 4E, treatment with 0.5 μM Elacridar for 24 hrs resensitized TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment, leading to both growth inhibition (Fig 4E) and induction of apoptosis (Fig 4F). Collectively, these data suggested that while ABCB1 overexpression enhances docetaxel resistance, inhibition of ABCB1 expression resensitizes prostate cancer cells to docetaxel treatment.

Figure 4. Downregulation of ABCB1 expression resensitizes TAXR cells to docetaxel treatment.

(A) Transient downregulation of ABCB1 expression resensitized TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment. After 48 hrs transfection with 2 μg shABCB1 or control, TaxR cells were treated with vehicle or 50 nM docetaxel for 48 h and cell numbers were counted. (B) Efficient downregulation of ABCB1 protein levels was shown by the Western blot. (C) Stable clones (clone #2 and #30) with downregulation of ABCB1 expression were generated. TaxR cells were stably transfected with shRNA of ABCB1 or vector control. Downregulation of ABCB1 was verified in clone No. 2 and No. 30 at both mRNA and protein levels. (D) Stable downregulation of ABCB1 expression resensitized TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment. Parental C4-2B, TaxR-ctrl cells, and clones No. 2, 30 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of docetaxel for 48 h and cell numbers were counted. (E) Downregulation of ABCB1 expression by elacridar resensitized TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment. C4-2B and TaxR cells were treated with docetaxel (25 nM) alone or in the presence of the ABCB1 inhibitor Elacridar (0.5 μM) and Docetaxel (25 nM). Cell numbers were counted after 24 hrs exposure (left); growth media were collected and assayed for apoptosis by cell death ELISA (right). Bottom panel shows ABCB1 protein levels in TaxR cells treated as indicated. *, statistically significant differences between groups (P<0.05).

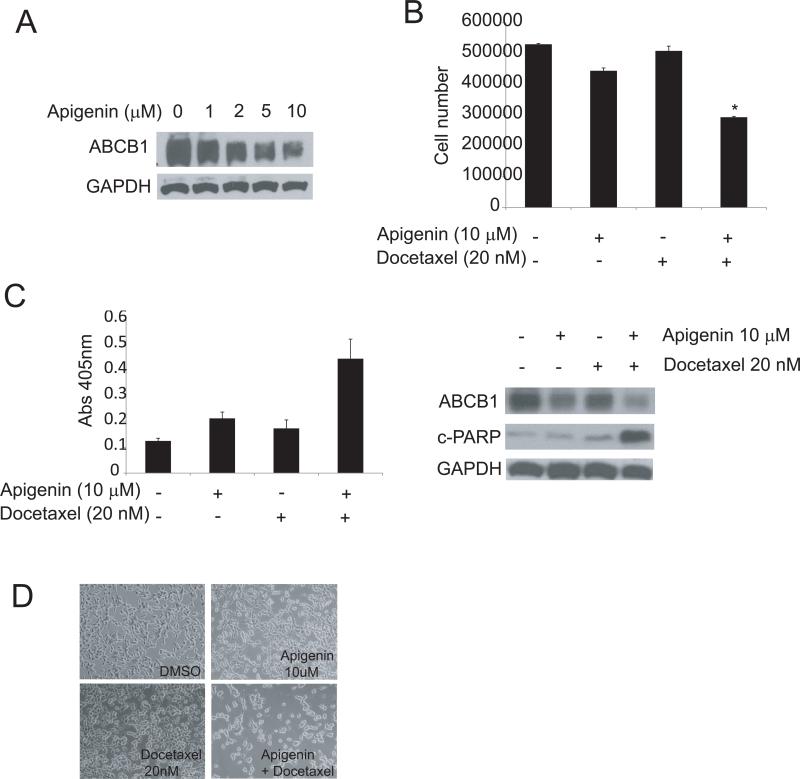

Apigenin downregulates ABCB1 expression and reverses docetaxel resistance

Since downregulation of ABCB1 reverses docetaxel resistance, we attempted to search for agents that can inhibit ABCB1 expression and therefore increase docetaxel sensitivity. Apigenin (4’,5,7-trihydroxyflavone), a natural product belonging to the flavone family, has the ability to modulate multidrug resistance genes and induce apoptosis in prostate cancer cells (15). We tested whether apigenin inhibits ABCB1 expression in docetaxel resistant TaxR cells. TaxR cells were treated with increasing concentrations of apigenin. Total proteins were extracted after 48 hrs exposure and assessed by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig 5A, apigenin downregulates ABCB1 protein expression in a dose-dependent manner. To examine whether apigenin could reverse docetaxel resistance in TaxR cells, TaxR cells were treated with 20 nM docetaxel alone or in the combination with 10 μM apigenin. As shown in Fig 5B, docetaxel alone at 20 nM had little effect on cell growth, apigenin alone at the concentration of 10 μM reduced TaxR cell growth by about 10-20%, while the combination of 20 nM docetaxel and 10 μM apigenin reduced growth of TaxR cells by about 50%. Cell death ELISA showed that the combination of apigenin and docetaxel induced apoptotic cell death (Fig 5C). The combination treatment also induced cleavage of PARP, a marker of apoptotic cell death, as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig 5D). These results demonstrate that apigenin restores docetaxel sensitivity of TaxR cells, suggesting that treatment with a combination of apigenin and docetaxel could be a potential strategy to overcome docetaxel resistance in castration resistant prostate cancer.

Figure 5. Apigenin downregulates ABCB1 expression and suppresses acquired docetaxel resistance.

(A) Apigenin inhibits ABCB1 expression. TaxR cells were treated with different doses of apigenin as indicated. After 48 hours exposure, whole cell lysates were collected. ABCB1 expression levels were analyzed by Western blot using specific antibody. (B) Apigenin resensitizes TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment. TaxR cells were treated with either 10 μM apigenin alone or with 20 nM docetaxel. After 48 hrs treatment, cell numbers were counted; (C) mono and oligo-nucleosomes of cytosolic fractions were assessed for cell death detection ELISA (left) and whole cell extracts were subjected to Western blot analysis using specific antibodies as indicated (right); (D) photographs of TaxR cells treated as indicated were taken.

Discussion

Docetaxel is used as 1st line treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer patients that failed bicalutamide therapy. However, relapse eventually occurs due to the development of resistance to docetaxel. In this study, we generated a docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cell subline, TaxR, from parental castration resistant C4-2B cells. We identified ABCB1, which belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, as the top upregulated gene in TaxR cells through global gene expression analysis and expression validation. Knockdown of ABCB1 expression by its specific shRNA or the inhibitor, Elacridar, resensitized docetaxel resistant TaxR cells to docetaxel. In addition, we demonstrate that apigenin, a natural product of the flavone family, inhibits ABCB1 expression and resensitizes docetaxel resistant TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment.

Several docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cell lines have been generated including PC3, DU145, and CWR22rv1 (11, 14, 16). Using these docetaxel resistant cell models, several genes have been identified to be associated with docetaxel resistance. Overexpression of Notch and Hedgehog signaling has been found to be linked to docetaxel resistance in DU145 and CWR22v1 cells (14). Down regulation of CDH1 and IFIH1 has been identified in docetaxel resistant PC3 and DU145 cells and verified in prostate tumors from docetaxel resistant patients (16). We generated the TaxR docetaxel resistant cell line from C4-2B cells cultured in media containing docetaxel for a long period of time. The cells are about 70-fold more resistant to docetaxel compared to parental C4-2B cells, with an IC50 of 140 nM docetaxel. Interestingly, in addition to docetaxel, TaxR cells are resistant to paclitaxel, but not to doxorubicin (Fig 6). This may be due to different mechanisms of action between taxane (docetaxel and paclitaxel) family (microtubule stabilization) and doxorubicin (DNA intercalation and topoisomerase II inhibition). Using global gene expression analysis, we identified ABCB1 as a top upregulated gene in TaxR cells vs parental C4-2B cells. Data analysis of public data bases generated from docetaxel resistant DU145DR and Rv1DR cells showed that ABCB1 is also overexpressed in both DU145DR and Rv1DR cells(14), suggesting that overexpression of ABCB1 is a common mechanism involved in acquired docetaxel resistant prostate cancer. Functional validation studies showed that inhibition of ABCB1 expression resensitized TaxR cells to docetaxel.

Figure 6. Effects of paclitaxel and doxorubicin on TaxR cells.

C4-2B and TaxR cells were treated with increasing doses of paclitaxel or doxorubucin as indicated for 48 hours. Numbers for cells untreated were expressed as 100% and numbers for cells treated with indicated concentrations of drugs were expressed as % relative to untreated group. (A) paclitaxel; (B) doxorubicin.

The results show that resensitization of TaxR cells to docetaxel treatment by downregulation of ABCB1 may have potential clinical implications. ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein, or MDR1) belongs to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters that use the energy of ATP hydrolysis to transport substrates including alkaloids, anthracyclines and taxanes across cell membranes and diminish efficacy of the drug (17). Early studies showed that increased expression of ABCB1 confers resistance to chemotherapeutic agents including docetaxel (11, 18, 19). In addition, ABCB1 expression is directly correlated with prostate tumor grade and stage (20). It is possible that while patients respond initially to docetaxel treatment, ABCB1 expression is induced by docetaxel and subsequently transports docetaxel across cell membranes, thus diminishing efficacy and resulting in development of resistance. Together with the results showing that ABCB1 is overexpressed in docetaxel resistant TaxR cells and downregulation of ABCB1 expression increases docetaxel sensitivity, induction of expression of ABCB1 by docetaxel may be one of the key mechanisms that are responsible for the acquired docetaxel resistance, and targeting ABCB1 expression could be a valid strategy to augment docetaxel efficacy and enhance the duration of treatment.

Overcoming docetaxel resistance presents a huge challenge to the treatment and management of docetaxel resistant castration resistant prostate cancer. Based on our finding that downregulation of ABCB1 resensitizes docetaxel resistant prostate cancer to docetaxel treatment, we attempted to identify inhibitors of ABCB1 and tested their ability to overcome docetaxel resistance. Toward this goal, we have identified apigenin, a natural product belonging to the flavone family, as an inhibitor of ABCB1. Apigenin, 4’, 5, 7-trihydroxyflavone, has gained particular interest in recent years because of its low cyto-toxicity and significant effects on cancer cells vs normal cells (21, 22). The anti-tumor effects of apigenin have been identified in a wide variety of malignant cells including prostate (15, 23, 24), melanoma (25, 26), breast (27, 28), leukemia (29), lung (30) and colon (31). Apigenin acts on a broad range of molecular signaling including suppression of the PI3K-Akt pathway in breast cancer (27, 28), induction of G2/M arrest by modulating cyclin-CDK regulators and MAPK activation (32), and alteration of the expression levels of pro-apoptotic factors like Bax/Bcl2, which leads to caspase activation and PARP-cleavage (23). More recently, apigenin has been shown to be able to sensitize cancer cells to taxane induced apoptotic death by promoting the accumulation of ROS in a caspase-2 dependent manner (33). Our findings showing that apigenin inhibits ABCB1 expression and overcomes docetaxel resistance provide additional evidence that apigenin may play a role in the management of castration resistant prostate cancer after failure of docetaxel therapy.

Collectively, these results suggest that overexpression of ABCB1 may be a potential mechanism that is responsible for docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer and that targeting ABCB1 expression may be an attractive approach to resensitize docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cells to docetaxel.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center Genomics Shared Resource is supported by Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA93373-01 (R.W. dV.W.) from the NCI.

Grant Support: This work is supported in part by grants NIH/NCI CA140468, CA118887, DOD PCRP PC080538 (A.C. Gao), US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development VA Merits I01 BX000526 (A.C. Gao), and by resources from the VA Northern California Health Care System, Sacramento, California.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: No potential conflict of interest

References

- 1.Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6:76–85. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SJ, Kim SI. Current treatment strategies for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Korean J Urol. 2011;52:157–65. doi: 10.4111/kju.2011.52.3.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan MA, Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:253–65. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins CF. Multiple molecular mechanisms for multidrug resistance transporters. Nature. 2007;446:749–57. doi: 10.1038/nature05630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ. Evolving standards in the treatment of docetaxel-refractory castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:192–205. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2011.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galletti E, Magnani M, Renzulli ML, Botta M. Paclitaxel And Docetaxel Resistance: Molecular Mechanisms and Development of New Generation Taxanes. ChemMedChem. 2007;2:920–42. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seruga B, Ocana A, Tannock IF. Drug resistance in metastatic castration- resistant prostate cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:12–23. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshino T, Shiina H, Urakami S, Kikuno N, Yoneda Y, Shigeno K, et al. Bcl-2 Expression as a Predictive Marker of Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer Treated with Taxane-Based Chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6116–24. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhong B, Sallman DA, Gilvary DL, Pernazza D, Sahakian E, Fritz D, et al. Induction of clusterin by AKT-Role in cytoprotection against docetaxel in prostate tumor cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1831–41. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kosaka T, Miyajima A, Shirotake S, Suzuki E, Kikuchi E, Oya M. Long-term androgen ablation and docetaxel up-regulate phosphorylated Akt in castration resistant prostate cancer. J Urol. 2011;185:2376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Neill AJ, Pencipe M, Dowling C, Fan Y, Mulrane L, Gallagher W, et al. Characterisation and manipulation of docetaxel resistant prostate cancer cell lines. Mol Cancer. 2011:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-126. doi: 10.1186/476-4598-10-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottesman MM, Fojo T, Bates S. Multidrug resistance in cancer: role of ATP-dependent transporters. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:48–58. doi: 10.1038/nrc706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu C, Zhu Y, Lou W, Nadiminty N, Chen X, Zhou Q, et al. Functional p53 determines docetaxel sensitivity in prostate cancer cells. Prostate. 2013;73:418–27. doi: 10.1002/pros.22583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domingo-Domenech J, Vidal SJ, Rodriguez-Bravo V, Castillo-Martin M, Quinn SA, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, et al. Suppression of acquired docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer through depletion of notch- and hedgehog-dependent tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:373–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shukla S, Gupta S. Suppression of constitutive and tumor necrosis factor alpha- induced nuclear factor (NF)-kappaB activation and induction of apoptosis by apigenin in human prostate carcinoma PC-3 cells: correlation with down-regulation of NF-kappaB- responsive genes. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:3169–78. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marin-Aguilera M, Codony-Servat J, Kalko SG, Fernandez PL, Bermudo R, Buxo E, et al. Identification of docetaxel resistance genes in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:329–39. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharom FJ. ABC multidrug transporters: structure, function and role in chemoresistance. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:105–27. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.1.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szakács G, Paterson JK, Ludwig JA, Booth-Genthe C, Gottesman M. Targeting multidrug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:219–34. doi: 10.1038/nrd1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez C, Mercado A, Contreras HR, Mendoza P, Cabezas J, Acevedo C, et al. Chemotherapy sensitivity recovery of prostate cancer cells by functional inhibition and knock down of multidrug resistance proteins. Prostate. 2011;71:1810–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.21398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhangal G, Halford S, Wang J, Roylance R, Shah R, Waxman J. Expression of the multidrug resistance gene in human prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2000;5:118–21. doi: 10.1016/s1078-1439(99)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta S, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Selective growth-inhibitory, cell-cycle deregulatory and apoptotic response of apigenin in normal versus human prostate carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:914–20. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shukla S, Gupta S. Apigenin: a promising molecule for cancer prevention. Pharm Res. 2010;27:962–78. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0089-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta S, Afaq F, Mukhtar H. Involvement of nuclear factor-kappa B, Bax and Bcl-2 in induction of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by apigenin in human prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3727–38. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shukla S, Gupta S. Molecular mechanisms for apigenin-induced cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis of hormone refractory human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells. Mol Carcinog. 2004;39:114–26. doi: 10.1002/mc.10168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwashita K, Kobori M, Yamaki K, Tsushida T. Flavonoids inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in B16 melanoma 4A5 cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2000;64:1813–20. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caltagirone S, Rossi C, Poggi A, Ranelletti FO, Natali PG, Brunetti M, et al. Flavonoids apigenin and quercetin inhibit melanoma growth and metastatic potential. Int J Cancer. 2000;87:595–600. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20000815)87:4<595::aid-ijc21>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Way TD, Kao MC, Lin JK. Apigenin induces apoptosis through proteasomal degradation of HER2/neu in HER2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer cells via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4479–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Long X, Fan M, Bigsby RM, Nephew KP. Apigenin inhibits antiestrogen-resistant breast cancer cell growth through estrogen receptor-alpha-dependent and estrogen receptor-alpha-independent mechanisms. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2096–108. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang IK, Lin-Shiau SY, Lin JK. Induction of apoptosis by apigenin and related flavonoids through cytochrome c release and activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3 in leukaemia HL-60 cells. Eur J Cancer. 1999;35:1517–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li ZD, Liu LZ, Shi X, Fang J, Jiang BH. Benzo[a]pyrene-3,6-dione inhibited VEGF expression through inducing HIF-1alpha degradation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;357:517–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang W, Heideman L, Chung CS, Pelling JC, Koehler KJ, Birt DF. Cell-cycle arrest at G2/M and growth inhibition by apigenin in human colon carcinoma cell lines. Mol Carcinog. 2000;28:102–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin F, Giuliano AE, Law RE, Van Herle AJ. Apigenin inhibits growth and induces G2/M arrest by modulating cyclin-CDK regulators and ERK MAP kinase activation in breast carcinoma cells. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:413–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Y, Xin Y, Diao Y, Lu C, Fu J, Luo L, et al. Synergistic effects of apigenin and paclitaxel on apoptosis of cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.