Abstract

Hypertrophic (HCM) and dilated (DCM) cardiomyopathies are inherited diseases with a high incidence of death due to electrical abnormalities or outflow tract obstruction. In many of the families afflicted with either disease, causative mutations have been identified in various sarcomeric proteins. In this review, we focus on mutations in the cardiac muscle molecular motor, myosin and its associated light chains. Despite the >300 identified mutations there is still no clear understanding of how these mutations within the same myosin molecule can lead to the dramatically different clinical phenotypes associated with HCM and DCM. Localizing mutations within myosin’s molecular structure provides insight into the potential consequence of these perturbations to key functional domains of the motor. Review of biochemical and biophysical data that characterize the functional capacities of these mutant myosins suggests that mutant myosins with enhanced contractility lead to HCM while those displaying reduced contractility lead to DCM. With gain and loss of function potentially being the primary consequence of a specific mutation, how these functional changes trigger the hypertrophic response and lead to the distinct HCM and DCM phenotypes will be the future investigative challenge.

Keywords: Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, Dilated cardiomyopathy, Myosin, Super-relaxed state, Cardiac energetics, Strain-dependent kinetics

Introduction

Dilated and hypertrophic cardiomyopathies (DCM and HCM, respectively) are the two most common forms of genetic heart muscle disease. Although the mechanisms underlying HCM and DCM phenotypes are complex and incompletely understood, the principle pathology is manifest at the level of the ventricle in both diseases 1.

HCM affects nearly 0.5% of the general population 2, contributes to a significant percentage of sudden unexpected cardiac death in any age group and is a cause of debilitating cardiac symptoms. This disease is characterized by hypertrophy, especially of the ventricles and interventricular septum, due to aberrant sarcomere replication and excessive connective tissue deposition. Hundreds of mutations, affecting at least 20 different genes have been identified; all of which affect proteins in the cardiac muscle sarcomere 3, 4. The sarcomeric proteins associated with HCM perform different functions, including enzymatic and force-generating roles (β-cardiac myosin, myosin light chains, actin), structural scaffolds (myosin binding protein C, actin, titin, desmin), and regulatory proteins (tropomyosin, troponin and myosin binding protein C).

In contrast to HCM, DCM is characterized by a thinner than normal ventricular wall, and can culminate in heart failure. While the genetics of DCM mutations are more diverse, mutations in genes encoding the sarcomeric proteins, however, are included in the list of genes responsible for this disease 5, 6, and this includes missense mutations in β-cardiac myosin.

Although many mutations have been associated specifically with either HCM or DCM, mutations in a single protein can lead to either disease. The underlying molecular basis for the differing HCM and DCM phenotypes is unknown and there is no clear mechanistic hypothesis for how individual mutations could lead to such divergent phenotypes. Several mechanistic pathways have been identified including alterations in acto-myosin force generation7, transmission of the generated forces8, 9, disruptions in calcium homeostasis10-12, and myocardial energetics 13. Here we present an overview of the HCM and DCM mutations in myosin, the force producing molecular motor of cardiac muscle, and provide evidence that altered contractile properties of mutant myosin lead to altered myocardial contraction and ATP consumption, suggesting that altered myocardial energy usage ultimately leads to the disease phenotype13, 14.

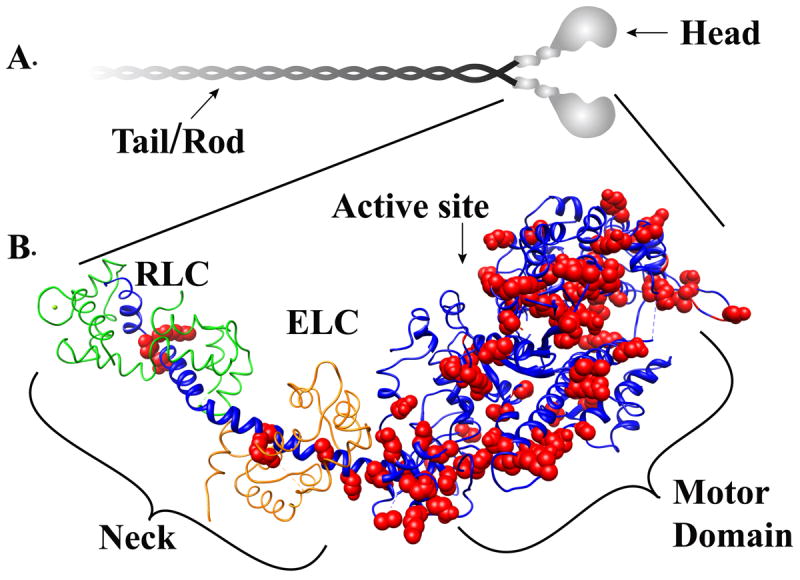

Myosin the cardiac muscle force generating molecular motor

Cardiac muscle contraction is powered by the ATP dependent interaction of myosin with actin. Myosin, the major component of the thick filament, consists of two heavy chains (MyHCs) and four light chains (two regulatory (RLCs) and two essential (ELCs)). Each MyHC associates with one of each light chain and two MyHC-LC complexes self-associate via an alpha helical coil-coil domain to form a dimeric myosin molecule (Fig. 1A). The myosin molecule can be roughly divided into the head and tail domains. An alternating 28 residue pseudo repeat of the alpha-helical coiled-coil tail domain drives myosin dimers to assemble in a head-to-tail fashion forming the core of the sarcomeric thick filaments. The head domain is more globular in shape and can be further separated into the motor domain and the neck domain. The motor domain contains the ATPase and actin binding regions of MyHC and has been shown to be the minimal subdomain sufficient for, albeit compromised, movement and force production15. To achieve full motion generation, small conformational changes in the myosin head are converted into large movements by the myosin neck region acting as a lever (Fig. 1B;) 16-20. The ELC and RLC wrap around the lever arm, supporting the neck and imparting stiffness to the lever arm 18, 21, 22. The proteolytic sub-fragment that contains the motor and neck domains has historically been referred to as the sub-fragment 1 (S1) while a domain predicted to be a less stable coiled-coil region that connects S1 to the tail domain is referred to as sub-fragment 2 (S2).

Figure. 1. Structure the myosin molecule.

Panel A Myosin is a hexameric protein consisting of two myosin heavy chain polypeptides that self-associate via an alpha helical coild-coil rod or tail domain. Each globular head domain is associated with two light chains one Essentail light chain (ELC) and one Regulatory light chain (RLC). Panel B: The atomic structure of the myosin head domain is shown. The heavy chain is shown in blue. The essential light chain and regulatory light chain are colored in grey. Small conformational changes in the motor domain are amplified by the light chain binding neck domain to produce movement and force. Cardiomyopathy-linked mutations (highlighted in red) are distributed throughout the head domain.

Many disease causing mutations map to the myosin gene

Numerous biophysical and biochemical studies have revealed important information about the function of myosin molecular motors23, 24. However, being such a large molecule, systematic site-by-site genetic mutagenesis and characterization of each of myosin’s 2002 residues would be an impractical task. With HCM and DCM, Mother Nature has already done this series of experiments for us, presenting scientists with a set of mutations that alter protein function in a way that ultimately leads to disease. It is important to note that the mutations likely highlight residues that are critical for modulating function, while mutation of the residues essential for function probably results in embryonic lethality.

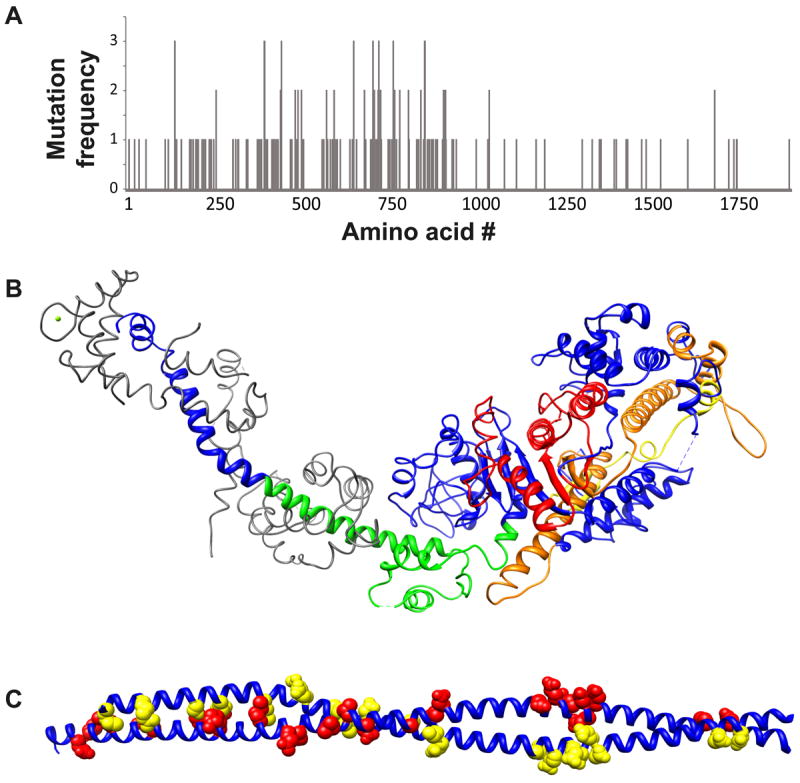

Myosin mutations were the first to be linked to HCM7. Over the next ~ 20 years >300 additional myosin mutations have been identified25-27, which are distributed throughout the molecule although, as can be seen in Figure 2, proportionally more mutations have been shown to occur in the S1 and S2 regions compared to the tail of the molecule25. Mutations mapped onto the atomic structure of the myosin S1 fragment (Fig. 1B) reveal that mutations do, in fact, map to critical regions. Furthermore, some regions have a greater frequency of mutations clustering in the head/motor domain near the ATPase site, sites proposed to be involved in actin binding, the converter and ELC-binding, as well as the S2 portion of the molecule (Fig.1B and 2). As can be seen in Figure 2B, these important regions of the molecule are critically involved in transmission of information about the state of the nucleotide bound in the catalytic site to distant regions of the molecule that are involved in actin binding and force production at the end of the light-chain-binding domain, i.e. the lever arm. Although hundreds of mutations of the β-MyHC gene have been linked to cardiomyopathy in humans, studies of the effects of these mutations on myosin mechanics and kinetics are restricted to a relatively small subset (Table 1). These studies have provided a deepened knowledge of the molecular mechanism of myosin based force generation and, as we describe below, are beginning to provide a framework for how the mutations may cause disease.

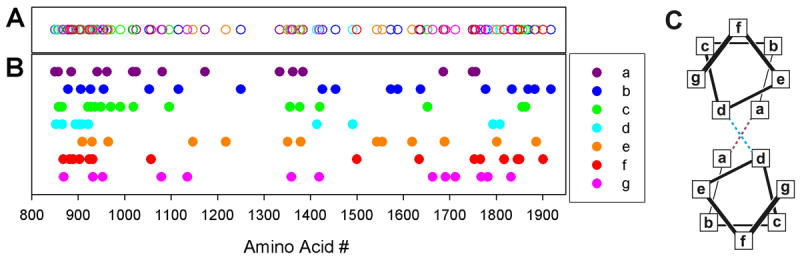

Figure 2. HCM and DCM mutations are distributed throughout the molecule.

Panel A: Distribution of mutations along the myosin heavy chain sequence. Mutations cluster in several regions: The ATP binding region (~130-260), the highly conserved regions implicated in actin binding (385-515 and 577-611), the long helix that extends from the SH1 and SH2 helix through the converter region and into the ELC binding domain (~705-810) and the S2 region at the junction between the motor domain and the filament forming rod domain. Panel B: Cardiomyopathy mutation clusters mapped on the atomic structure of chicken fast skeletal muscle myosin. ATP binding region (red). Actin binding region (yellow and orange). Converter/ELC binding (green). Panel C: Mutations in the S2 region mutations on one chain of the dimer are colored red while mutations in the other chain are highlight in yellow.

Table 1.

HCM and DCM associated mutations

| HCM Mutation | Myosin | Experiment | Velocity | ATPase | Contractile kinetics | Duty ratio | Force | PCa50 | Stiffness Kmyo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lys207Asn38 | Human β-cardiac | Motility | No change | ||||||

| Gly256Glu108 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | No change | No change | |||||

| Arg403Gln108 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Decrease | Decrease | |||||

| Arg403Gln44 | Human β-cardiac | Myofibril | Increase | Decrease | |||||

| Arg403Gln109 | Chicken embryonic | Motility | Increase | No change | |||||

| Arg403Gln42 | Mouse α-cardiac | Motility | Increase | Increase | |||||

| Arg403Gln43 | Mouse α-cardiac | Motility | Increase | Increase | Increase | ||||

| Arg403Gln36 | Mouse α-cardiac | Motility | Increase | Increase | |||||

| Arg403Gln36 | Mouse β-cardiac | Motility | No change | No change | |||||

| Arg403Gln39 | Human β-cardiac | Motility | Increase | ||||||

| Arg403Gln42 | Mouse α-cardiac | Fiber | Decrease | No change | |||||

| Arg453Cys109 | Chicken embryonic | Motility | Decrease | Increase | |||||

| Arg453Cys42 | Mouse α-cardiac | Motility | No change | No change | |||||

| Arg453Cys43 | Mouse α-cardiac | Motility | No change | No change | Increase | ||||

| Arg453Cys42 | Mouse α-cardiac | Motility | Increase | Increase | |||||

| Gly584Arg109 | Chicken embryonic | Motility | Decrease | Increase | |||||

| Arg719Trp47 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Increase | Increase | |||||

| Arg719Trp48 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Decrease | ||||||

| Arg719Trp45 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Increase | Increase | Increase | ||||

| Arg723Gly48 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Decrease | ||||||

| Arg723Gly45 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Increase | Increase | Increase | ||||

| Ile736Thr48 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Increase | ||||||

| Ile736Thr45 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Increase | No change | |||||

| Gly741Arg108 | Human slow skeletal (β-MHC) | Fiber | Decrease | Decrease | |||||

| Gly741Arg46 | Mouse β-cardiac | Fiber | No change | ||||||

| Asp778Gly35 | Chicken smooth muscle myosin | Fiber | Increase | ||||||

| Asp778Gly46 | Mouse β-cardiac | Fiber | Increase | Increase | |||||

| Asp778Val110 | Molecular Dynamics | ||||||||

| Asp906Gly38 | Human β-cardiac | Motility | Increase | ||||||

| Leu908Val38 | Human β-cardiac | Motility | Increase | ||||||

| Leu908Val39 | Human β-cardiac | Motility | Increase | ||||||

| Asp906Gly/Leu908Val38 | Human β-cardiac | Motility | No change | ||||||

| DCM mutation | |||||||||

| Ser532Pro43, 52 | Motility | Decrease | Decrease | Decrease | |||||

| Phe764Leu43, 52 | Motility | Decrease | Decrease | Increase |

HCM mutations: gain of function vs loss of function?

Velocity and ATPase

An attractive early hypothesis for HCM was that reduced enzymatic/contractile activity of mutant myosin molecules leads to compensatory hypertrophy to counteract the contractile deficit. Consistent with this notion, several early studies of R403Q mutant β-myosin isolated from either human leg and ventricular muscles (i.e. the same isoform of cardiac β-myosin is expressed in the slow soleus leg muscle) revealed a severe decrease in the velocity of actin filaments over a coverslip surface coated with mutant myosin28, which serves as a model system for muscle contraction under unloaded conditions. However these initial attempts at determining the molecular defects in myosin that give rise to HCM were confounded by the difficulties in studying this large complex molecule in the small biopsies available from patients 29. In the intervening years several studies using transgenic mice and myosin expressed in vitro have led to a different picture where instead of reducing contractility many of the HCM mutations enhance activity as measured by increased hydrolytic or force and motion producing capabilities either in the active or relaxed states (Table 1).

Despite the fact that modifying genes may alter the ability of transgenic mouse models to develop a phenotype typical of the human disease30-32, the first mouse model for HCM showed that mice heterozygous for the R403Q mutation developed a hypertrophic phenotype with myocyte disarray, resembling the human disease33. Subsequent structural studies found that R403Q mutant smooth muscle myosin S1 was attached to actin at highly variable angles compared to wild-type, suggesting that the histopathological myocyte disarray may be linked to an underlying disarray at the acto-myosin level. Functional studies showed that the R403Q mutation increased actin filament velocity (Vactin) using α-cardiac34 or smooth muscle myosin35 heavy chain backbones, but caution is warranted given the observation that expression of the R403Q mutation in the mouse α-cardiac myosin showed increased Vactin while in the mouse β-cardiac myosin there was no significant effect36. This result in and of itself suggests that mutations would best be studied in the context of the human β-myosin backbone. However, the enhanced contractile properties observed in vitro were consistent with the observation that hearts from the mutant R403Q mice exhibited an accelerated systolic pressure rise and increased contractile dynamics37. Interestingly, the enhancement in enzymatic activity observed with the R403Q mutation was subsequently observed for several other HCM associated mutations. Myosin purified from hearts of patients heterozygous for the D906G and L908V mutations had a 34% and 24% increase in Vactin when compared to normal controls38. Similarly in vitro expressed myosin containing the D778G mutation or myosin isolated form hearts harboring the R403W, R403Q, and R453C mutations exhibit an increase in contractility as measured by Vactin, ATPase and/or power output34, 35, 39-44. Skinned fiber studies have also shown an increased ATPase and unloaded shortening velocity for the R719W and R723G mutations respectively45 and faster tension development and relaxation in human cardiac myofibrils with the R403Q mutation44. Similarly, cultured mouse myoblasts expressing mutant HCM myosin also revealed that unloaded shortening velocity was increased for the D778G mutant, whereas velocity was unchanged for the G741R mutant46. Thus several mutant myosins either expressed in vitro, purified from mouse cardiac tissue, or studied in the myofibrillar environment display enhanced ATPase activity, tension development and relaxation kinetics, and/or unloaded velocity.

Isometric force and calcium sensitivity

HCM mutations in myosin have also been shown to have effects on the sensitivity of the contractile apparatus to calcium, isometric force generation, and myosin stiffness (Table 1). Similar to what was observed for unloaded velocity and ATPase, the majority of the myosin mutations studied resulted in increases in force (Table 1). For example, the R403Q and R453C mutations result in an increased force and power production43. Similarly two mutations in the converter region displayed an increase in isometric force, which resulted from an increase in myosin stiffness45, 47, 48.

In vitro studies have also revealed that many HCM mutations result in an increased calcium sensitivity of the contractile apparatus (Reviewed in49). Several myosin mutations are among them. The R403Q mutation50 and the R453C mutation42 increase calcium sensitivity of isometric force production. Similarly, a mutation in the converter region, I736T, increased calcium sensitivity and demonstrated significant active force even under relaxing conditions45. It is important to note however, that increased calcium sensitivity is not the universal cause of HCM as there are reports of several mutations having no effect or even decreased calcium sensitivity45.

With HCM mutations affecting velocity, ATPase, force, and calcium sensitivity of activation, a major question remains as to how these phenotypes could lead to HCM. One unifying hypothesis consistent with most of the data is that the mutations (Table 1) result in increased contractile activity.

DCM mutations

Although it has been established for the past two decades that HCM and DCM are “diseases of the sarcomere”, the pathway that leads from the individual mutant gene to the distinct cardiac phenotypes is largely unknown. Unlike the numerous studies of the HCM causing mutations described above and elsewhere51, information about the contractile alterations in DCM mutant myosins is only recently emerging (Table 1). Mouse models of the DCM-causing mutations S532P and F764L both faithfully recapitulate the human disease phenotype52. Interestingly, unlike the myosin mutations associated with HCM, myosin purified from hearts expressing the S532P and F764L mutations showed a contractile deficit. Mutant S532P and F764 myosin propelled actin filaments at 57% and 80% the velocity of wild-type myosin52. ATPase and power output were also similarly reduced43, 52. Cellular contractile measurements revealed similar deficits in performance that preceded the onset of cardiac dilation52 indicating that the contractile deficit is the primary insult and not a consequence of the dilated phenotype.

Thus these data support the idea that the primary insult for the HCM and DCM mutations in the myosin motor domain is an alteration in myosin motor activity and that the resulting effects on contractility at the cellular and organ levels precede the disease phenotype. Mutations that enhance motor activity lead to HCM while mutations that diminish motor function lead to DCM.

Mutations in the light chains: A common theme for HCM?

The myosin light chains function to support the elongated α-helical domain that extends from the motor domain. Given the importance of the myosin neck/lever in force and motion generation, it is not surprising that several mutations in the myosin light chains and the myosin neck region were found to be associated with HCM. Similarly, analogous to the light chains, numerous MyHC mutations likely function to destabilize the proximal portion of the helix.

Myosin light chains belong to the EF-hand family of calcium binding proteins53. With the exception of the N-terminal EF-hand of the RLC, the EF-hands of the myosin light chains have lost their ability to bind calcium or magnesium. Mutation of the divalent metal binding site of the RLC has been shown to alter myosin cross-bridge attachment and detachment kinetics54 indicating that an intact N-terminal EF-hand is critical to proper function of myosin.

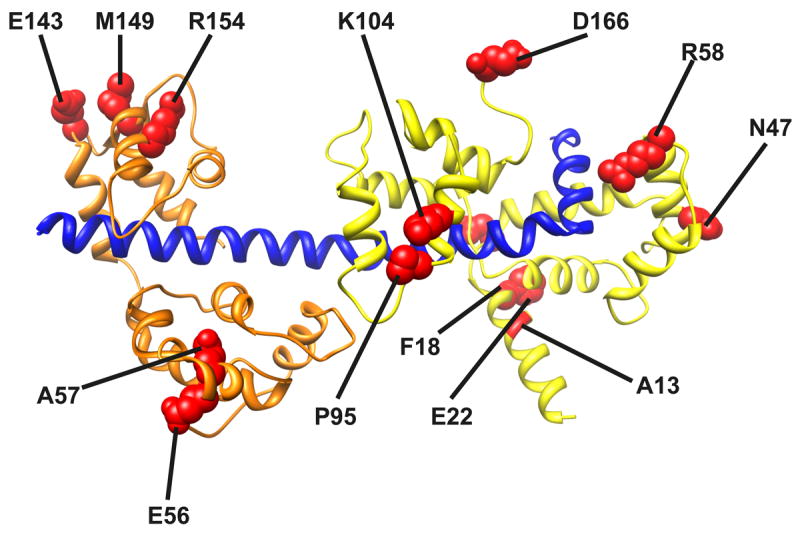

Thirteen mutations have been identified in the myosin light chains, eight mutations in the RLC and 5 mutations in the ELC. The ELC mutations are located primarily in exons 3 and 4 (Fig. 3) indicating that, while incapable of binding calcium, the EF hand motifs of the ELC play an important structural role. Data on the effects of ELC mutations on myosin enzymology are limited but, consistent with the increased contractility hypothesis, one ELC mutation, M149V, has been shown to have a 40% increase in Vactin compared with control myosin55.

Figure. 3. HCM mutations (red) mapped onto the chicken skeletal myosin light chain structures.

The C-terminal region of the MyHC neck is shown in blue, the RLC in green and the ELC in orange.

Mutations identified in the RLC are located throughout the molecule (Fig. 3). The positions of the known RLC mutations55-58 are mapped onto the crystal structure of the chicken skeletal regulatory domain in Fig. 3. The mutations appear to be clustered in three regions: near the phosphorylatable serine (A13T, F18L, and E22K), the Calcium/Magnesium binding site (E22K, N47K and R58Q), and the linker/C-terminal regions of the RLC (P95A, K104E, D166V). Although not studied as thoroughly as the MyHC mutations, there is strong evidence that LC mutations affect several aspects of myosin structure and function 59. Here we will discuss N47K and R58Q, two of the most malignant mutations in the RLC, focusing on how they alter the sensitivity of myosin biochemistry to strain and ultimately support the gain of function hypothesis for HCM.

When the N47K and R58Q RLC mutations are exchanged onto a β-MyHC backbone there is no effect on Vactin or ATPase activity60, seemingly at conflict with the gain of function hypothesis. It is important to point out, however, that these experiments were performed under unloaded conditions.

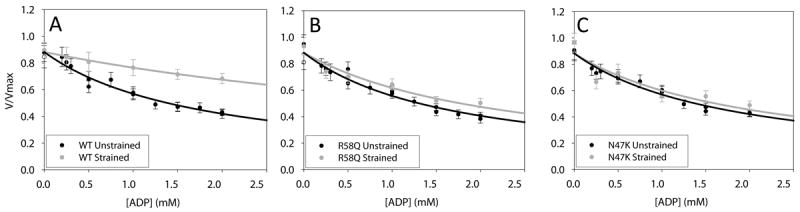

Since the heart must work to pump blood during systole, myosin will always contract against a load and thus the loaded kinetics reflect the ability of myosin to produce work and power under more physiological conditions. Myosin’s ability to perform mechanical work and power is driven by ATP hydrolysis and requires the coupling of its multistep enzymatic and mechanical cycles. In 1923, Fenn61 showed that the kinetics of the myosin molecule are modulated by strain. ADP release from myosin’s catalytic site has been shown to be the rate limiting step for detachment kinetics in myosin and thus a principal determinant of Vactin. Thus when exogenously added ADP competes for ATP binding, velocity is slowed (Ki = 160 ± 10 μmol/L; Fig. 4A). On the other hand, in vitro motility assays examining Vactin as a function of ADP concentration in the presence of load show that load causes a significant ~3-fold increase in the inhibition constant (Ki= 400 ± 60 μmol/L; Fig. 4A). To explain this result it was proposed that straining the myosin traps ADP in the myosin catalytic site preventing its release and rendering it relatively insensitive to exogenously added ADP60, 62. This result is consistent with a strain-dependent isomerization in the ADP bound state63. Interestingly the N47K and R58Q mutations lack the load dependent increase in the Ki (Fig. 4 B and C), consistent with the idea that the RLC mutations reduce myosin stiffness and disrupt transfer of load to the active site.

Figure. 4. HCM mutations in the myosin RLC disrupt myosin strain sensitive biochemistry.

Porcine cardiac myosin velocity as a function of ADP. (gray) loaded (black) unloaded. Panels A, B and C are Wild-type, R58Q and N47K respectively.

In the healthy heart, straining the myosin molecule causes the myosin crossbridges to cycle more slowly, thus hydrolyzing less ATP. It has been suggested that this physiologically important strain dependence underlies the hyperbolic shape of the force velocity curve, and also serves to increase the economy of maintaining and generating tension in loaded muscle. The increase in the economy of tension development is critical for proper functioning of the heart. The lack of strain dependence in the mutant myosins harboring the N47K and R58Q mutant RLCs would result in an unusually high ATP consumption (like that described above for the MyHC mutations) but only clearly observed under more-physiological loaded conditions.

Therefore, defects in strain-dependent mechanochemistry can contribute to disease by causing the mutant myosins to hydrolyze more ATP at physiologic loads. Interestingly, the sites of HCM mutations in the head domain, as discussed above, map out the critical mechanical communication pathways between the catalytic site and more distant domains that are involved with force transmission and sensing. Furthermore, the data also suggest that future in vitro and in vivo studies examining mutation based defects in contractility must not only be characterized under unloaded conditions, but also load dependent changes in myosin mechanochemistry should be considered.

Mutations in the myosin rod affect assembly and stability

While the mechanisms by which mutations in the myosin motor domain are readily interpreted based on predicted effects on motor function, the pathogenic mechanisms of mutations in the rod and S2 portions of the myosin molecule are less clear. It has been proposed that mutations in the myosin head/motor domain lead to a distinct phenotype compared to those in the rod64. The myosin rod is an α-helical coiled-coil protein that self-associates to form the bipolar thick filament. α-helical coiled-coil proteins are characterized by a common heptad amino acid repeat sequence (abcdefg)n. The a and d positions of the coiled-coil are typically hydrophobic residues that stabilize the interaction interface between the coiled-coil helices, while oppositely charged residues in the e and g positions form salt bridges that stabilize the hydrophobic core (Fig. 5).

Figure. 5. Cardiomyopathy mutations in the myosin rod.

Panels A and B: Mutation location corresponding to the heptad repeat (abcdefg)n are shown in purple, blue, green, cyan, yellow, red, and pink respectively. Panel A open circles; Panel B filled circles Panel C: helical wheel representation of the canonical coiled-coil structure. Hydrophobic interactions between the a and d postions and salt bridges between the e and g positions stabilize the structure.

Dimeric myosin molecules assemble into helical-bipolar thick filaments with a helical repeat of 43 nm and an axial stagger of 14.3 nm between myosin molecules. Assembly is a property of the isolated light meromyosin portion of the myosin rod65 and is thought to be driven by favorable electrostatic interactions along repeating 28 residue charge zones66 and the presence of the so-called assembly competent domain67. To date, 112 mutations have been identified in the rod region. Overall, the mutations are distributed throughout the heptad positions although mutations in the d positions are more rare and appear to be clustered in the N-terminal rod segments. Interestingly, with the exception of G1057S, mutations in the d and f positions are absent between residues 931 and 1414 (Fig. 5). A1379T and S1776G were among the first mutations to be identified in the myosin rod region and were proposed to disrupt thick filament assembly properties9. Consistent with this notion the c position mutation, E1356K, was shown to destabilize the protein and reduce filament formation without any detectable changes in secondary structure64. Molecular dynamics simulations of myosin rod mutations have also recently been used to assay the nanomechanical properties of the human cardiac S2 domain 68. These models predicted that the R1193S mutant S2 domain was considerably stiffer than wild-type. Proper myosin rod domain structure, mechanics, and stability are likely critical for both proper thick filament assembly and interaction with accessory proteins like MyBP-C, MyBP-H, myomesin, titin, and myosin head domains (see super-relaxed state below). In addition, forces either generated by the myosin itself or imposed externally as a load to the muscle are transmitted through the myosin filament backbone. Therefore, thick filament stability is critical to the stiffness of the thick filament and its ability to transmit force, providing another potential means of altering the kinetics of the myosin motor itself, which are load sensitive (see above). Biophysical and biochemical studies of myosin rod domain mutations are emerging and likely to provide critical understanding of thick filament assembly and the molecular underpinnings of the mutation phenotype.

Myosin interaction motifs in the thick filament may affect the ATPase activity of “super relaxed state”

Cardiac muscle contraction is regulated primarily by calcium binding to the thin filament. However, there is increasing evidence that cardiac muscle force can be modulated at the level of the thick filament69. In this regard, recent evidence indicates the presence of at least two biochemical states of the relaxed striated muscle thick filament: One state having a rapid ATPase with a time constant similar to the ATP turnover of isolated myosin in the absence of actin and another with a time constant ~ 5-fold longer, the so-called “super relaxed state”70-73. The super relaxed state is not present with isolated myosin but is found when myosin is assembled into thick filaments suggesting that there is likely a structural component involving a potential interaction between the myosin heads and/or the filament backbone. Head-head interactions have been observed for smooth muscle myosin that appear to be responsible for inhibition of ATPase activity74. Specifically, the actin-binding domain of one head (i.e. blocked head) binds the converter domain of its dimeric partner head (i.e. free head), thus preventing ATPase activity in both heads (see Fig. 6)74. Recent evidence from thick filaments75-77 suggests that these interactions represent a general mechanism for regulating myosin activity in striated muscles as well (Fig. 6). Therefore, mutation-induced disruption of thick filament regulation could alter energy consumption by the heart.

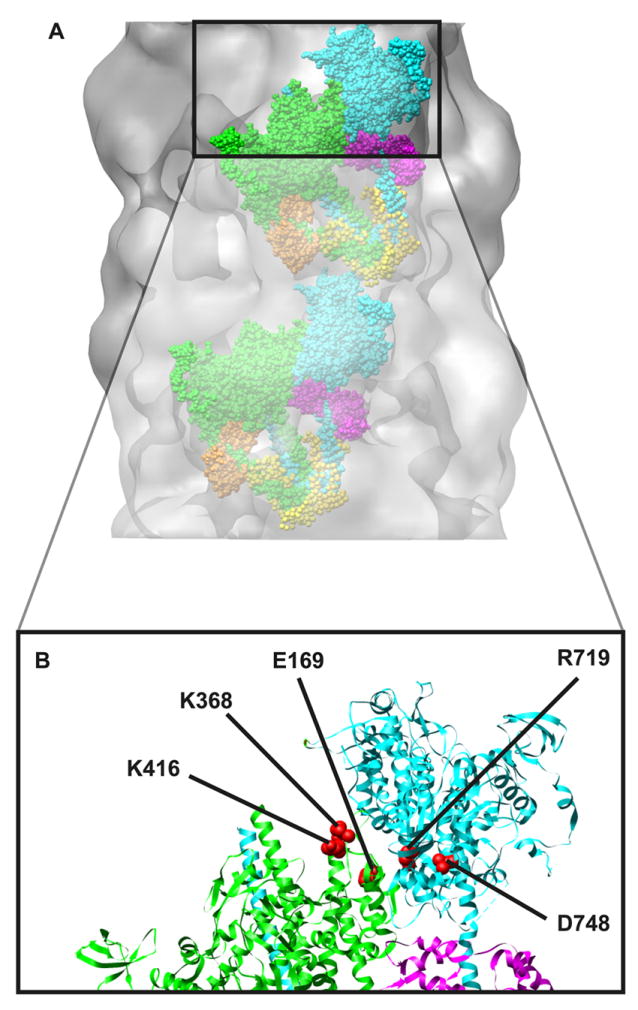

Figure 6. Thick filament myosin interacting head motif73.

Panel A: The interacting head motif docked onto the electron density map of the cardiac muscle thick filament. The interacting head motif contains interactions between the heads of the dimer and additional interactions between the heads and the thick filament backbone. In the motif, one head has its actin binding domain “free” to potentially interact with actin while the other head is in a “blocked” configuration where its actin binding domain interacts with the converter region of the free head. Panel B: Several cardiomyopathy mutations map to regions that could potentially alter the interacting head motif. Potentially interacting residues73 are highlighted as examples (red spheres).

Interacting head motif in cardiac muscle thick filaments

Electron microscopy has revealed an ordered structural motif in which myosin heads interact helically along the backbone of the mouse cardiac muscle thick filament78, 79. Molecular modeling and structural studies have revealed that ionic interactions at head-head and head-tail interfaces are important for the interacting head regulatory motif76. Specific interactions were found between D748 in the converter domain of the free head and K368 of the blocked head, and that R406 and/or K416 of the blocked head may interact with E169 of the free head. Interestingly, these residues map in (or very near) some of the regions with increased HCM mutation frequency also shown in Figure 2. Correcting for species differences, mouse R406 corresponds to the well-known human R403Q cardiomyopathy mutation suggesting that some aspects of the R403Q mutant phenotype could result from altered head-head interactions. Consistent with this notion, the R719W HCM mutation (near the putative D748/K368 interaction) was not regulated by phosphorylation when incorporated into smooth muscle myosin35.

A motor domain/S2-rod segment interaction has also been proposed to be an important component of the interacting head motif76, 80. The primary interaction has been proposed to be between a positive patch on myosin in the actin binding loop and a patch of negative charged residues residing in the N-terminal portion of S2. Again, these regions of the molecule are the ones highlighted in Figure 2. Of these, one of the best studied mutants is the L908V mutation. Therefore, in addition to the current known effects of the L908V mutation on myosin contractility, consideration of the potential effects of the mutation on relaxed head-head and head-tail interactions are likely important for understanding the mutant phenotype.

In cardiac muscle the ordered array of myosin molecules on the thick filament, and ultimately the relaxed myosin ATPase, is dynamic and can be modulated by several factors including myosin binding protein C81, 82 and myosin RLC phosphorylation (Reviewed in 83). In skeletal muscle, the super relaxed state has been proposed to play an important role in thermogenesis71. In cardiac muscle, transition from the super relaxed state has been proposed to be an important component of the recruitment of crossbridges out of the relaxed states to states that hydrolyze more ATP72, 73. Myocardial energy utilization could then be varied by sequestering a population of heads into an inactive state where they have a very low rate of energy utilization. Thus an HCM-mutation induced disruption of the distribution of heads between relaxed and super relaxed states could potentially lead to hypertrophy via an altered energetic state of the heart13.

Summary/Conclusions

In summary, studies of cardiomyopathy-linked mutations in myosin over the last two decades have begun to shed light on the underlying molecular cause of cardiomyopathy. As science often does, early attractive hypotheses that hypertrophic cardiomyopathy results from a myocardial compensatory response to compromised myosin molecular motor function have yet to be realized. Instead, a preponderance of data indicate that myosin with HCM mutations has enhanced activity and the relatively small number of DCM mutations studied display reduced contractility. The increased activity in HCM could result from several sources, increased: ATPase activity (in both the actin bound and unbound states), velocity, and/or force under loaded and unloaded conditions. However, it seems likely that firm conclusions need to await the analysis of mutations in the appropriate human β-myosin backbone36.

Physiologically, the increased enzymatic activity observed in studies of HCM-mutant myosin and mutant myocardium has been proposed to decrease the concentration of free ATP and result in the accumulation of hydrolysis products, ADP and Pi84, 85. Consistent with this idea, the resulting decrease in the free energy available from ATP hydrolysis has been correlated with the progression of disease86. The free energy from ATP hydrolysis is required for several critical processes in the heart and disruption of these processes may lead to the development of the disease phenotype. For example, the reduction of sarcoplasmic calcium levels during relaxation requires the activity of the sarcoplasmic reticular ATPase, the function of which can be compromised by reductions in phosphorylation potential. Furthermore, deficient calcium sequestering would lead to improper relaxation of the heart and diastolic dysfunction. This effect of incomplete relaxation would be more pronounced with the high levels of diastolic calcium resulting from impaired calcium sequestration. Interestingly, in support of the energy depletion hypothesis for HCM13, several non-myosin mutations that disrupt energy production in the myocardium have been shown to produce a similar phenotype87-90. Future studies are required to determine the mechanistic link that leads to the common consequence of these disparate protein mutations. Studies of Mother Nature’s experiment are beginning to shed light on the underlying molecular cause of cardiomyopathy and in the meantime continue to provide important insight into the molecular mechanism of cardiac myosin function.

Clinical insights

Individuals with known cardiomyopathy-causing mutations often do not develop overt symptoms until adulthood or are at times asymptomatic, presumably due to epigenetic or environmental influences in the development of the disease phenotype. Clinically this represents a challenge regarding follow up strategy for families with HCM. Current guidelines 91, 92 recommend genetic screening and recent studies indicate that the addition of molecular genetic screening to the management and diagnosis of HCM is the more likely to be cost effective than clinical tests alone93, 94. With genotyping feasible for some individuals with HCM and DCM, one question that arises is whether knowing the genetic cause of the disease will lead to better and potentially preventive treatments. Currently, disease management for HCM is primarily focused on alleviating symptoms via β-blockade and/or Ca2+ channel blockers95. These treatments as well as reduced exercise and antiarrhythmic drugs have been used to reduce the incidence of sudden cardiac death. For patients judged to be at high risk, an implantable defibrillator can be used96. The mechanism for altered electrical activity and ultimately ventricular fibrillation is not known but could result from altered calcium buffering by sarcomeric proteins as was proposed for HCM-linked mutations in the RLC97. In cases of HCM where removal of a severe obstruction is required, surgical myectomy or alcohol ablation has been shown to be somewhat effective in terms of symptom relief98, 99.

Newer treatments being proposed and developed include miRNA antagonists, angiotensin II receptor blockade and small molecule myosin activators. Recent evidence indicates a role for miRNAs in the development of cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Although MyHC mRNAs themselves have not been shown to be direct targets of any miRNAs, it is clear that regulation of MyHC expression by miRNAs is important. Both α- and β-MyHC encode miRNAs, miR-208a and miR-208b, respectively100. Intriguingly, animal studies have shown that inactivation of miR-208a prevents the pathologic induction of β-MyHC, cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis without any observable toxicity101 suggesting that miRNAs can be good targets for treatment of heart disease102, 103. Clinical trials of angiotensin II receptor blockade, based on research using a mouse model of HCM caused by a mutation in α cardiac MyHC, also show some promise104, 105 with one trial showing a reduction in hypertrophy; mostly in patients with myosin mutations105. Recently, the small molecule myosin activator, omecamtiv mecarbil, has been shown to be effective as a treatment for systolic heart failure106, 107. However, use of a myosin activator as a treatment option requires an in depth understanding of the underlying molecular defect on myosin mechanochemical function. For example, such a treatment likely should only be considered in treating patients with myosin mutations that result in a loss of function to the motor. Thus we are now at the exciting crossroad where molecular level information about actomyosin defects are poised to guide the development and administration of appropriate individual therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Anastasia Karabina and Gerrie Farman for help with Figures and data compilation.

Sources of funding: This work was supported by HL077280 (JRM), HL059408 (DMW), and HL50560 (LAL).

Non-standard abbreviations and acronyms

- MyHC

Myosin heavy chain

- ELC

Myosin essential light chain

- RLC

Myosin regulatory light chain

- HCM

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- DCM

Dilated cardiomyopathy

- S1

Proteolytic sub-fragment 1 of myosin

- S2

Proteolytic sub-fragment 2 of myosin

- LMM

Light meromyosin

- Vactin

actin filament velocity

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

References

- 1.Olivotto I, Cecchi F, Poggesi C, Yacoub MH. Developmental origins of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy phenotypes: A unifying hypothesis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:317–321. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2009.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liew CC, Dzau VJ. Molecular genetics and genomics of heart failure. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:811–825. doi: 10.1038/nrg1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marian AJ, Roberts R. Molecular basis of hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy. Tex Heart Inst J. 1994;21:6–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramaraj R. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Cardiol Rev. 2008;16:172–180. doi: 10.1097/CRD.0b013e318178e525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamisago M, Sharma SD, DePalma SR, Solomon S, Sharma P, McDonough B, Smoot L, Mullen MP, Woolf PK, Wigle ED, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Mutations in sarcomere protein genes as a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1688–1696. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012073432304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNally E, Dellefave L. Sarcomere mutations in cardiogenesis and ventricular noncompaction. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2009;19:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Mutations in cardiac myosin heavy chain genes cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mol Biol Med. 1991;8:159–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson TM, Doan TP, Kishimoto NY, Whitby FG, Ackerman MJ, Fananapazir L. Inherited and de novo mutations in the cardiac actin gene cause hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2000;32:1687–1694. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair E, Redwood C, de Jesus Oliveira M, Moolman-Smook JC, Brink P, Corfield VA, Ostman-Smith I, Watkins H. Mutations of the light meromyosin domain of the beta-myosin heavy chain rod in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2002;90:263–269. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fatkin D, McConnell BK, Mudd JO, Semsarian C, Moskowitz IG, Schoen FJ, Giewat M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. An abnormal Ca(2+) response in mutant sarcomere protein-mediated familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1351–1359. doi: 10.1172/JCI11093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szczesna-Cordary D, Guzman G, Zhao J, Hernandez O, Wei J, Diaz-Perez Z. The E22K mutation of myosin rlc that causes familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy increases calcium sensitivity of force and atpase in transgenic mice. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3675–3683. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haim TE, Dowell C, Diamanti T, Scheuer J, Tardiff JC. Independent FHC-related cardiac troponin t mutations exhibit specific alterations in myocellular contractility and calcium kinetics. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:1098–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.03.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashrafian H, Redwood C, Blair E, Watkins H. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy:A paradigm for myocardial energy depletion. Trends Genet. 2003;19:263–268. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crilley JG, Boehm EA, Blair E, Rajagopalan B, Blamire AM, Styles P, McKenna WJ, Ostman-Smith I, Clarke K, Watkins H. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to sarcomeric gene mutations is characterized by impaired energy metabolism irrespective of the degree of hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1776–1782. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)03009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toyoshima YY, Kron SJ, McNally EM, Niebling KR, Toyoshima C, Spudich JA. Myosin subfragment-1 is sufficient to move actin filaments in vitro. Nature. 1987;328:536–539. doi: 10.1038/328536a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warshaw DM, Guilford WH, Freyzon Y, Krementsova E, Palmiter KA, Tyska MJ, Baker JE, Trybus KM. The light chain binding domain of expressed smooth muscle heavy meromyosin acts as a mechanical lever. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37167–37172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore JR, Krementsova EB, Trybus KM, Warshaw DM. Myosin V exhibits a high duty cycle and large unitary displacement. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:625–635. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200103128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore JR, Krementsova EB, Trybus KM, Warshaw DM. Does the myosin V neck region act as a lever? J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2004;25:29–35. doi: 10.1023/b:jure.0000021394.48560.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uyeda TQ, Abramson PD, Spudich JA. The neck region of the myosin motor domain acts as a lever arm to generate movement. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4459–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruff C, Furch M, Brenner B, Manstein DJ, Meyhofer E. Single-molecule tracking of myosins with genetically engineered amplifier domains. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:226–229. doi: 10.1038/84962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pant K, Watt J, Greenberg M, Jones M, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Removal of the cardiac myosin regulatory light chain increases isometric force production. Faseb J. 2009 doi: 10.1096/fj.08-126672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.VanBuren P, Waller GS, Harris DE, Trybus KM, Warshaw DM, Lowey S. The essential light chain is required for full force production by skeletal muscle myosin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12403–12407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De La Cruz EM, Ostap EM. Relating biochemistry and function in the myosin superfamily. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tyska MJ, Warshaw DM. The myosin power stroke. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2002;51:1–15. doi: 10.1002/cm.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh R, Rutland C, Thomas R, Loughna S. Cardiomyopathy: A systematic review of disease-causing mutations in myosin heavy chain 7 and their phenotypic manifestations. Cardiology. 2010;115:49–60. doi: 10.1159/000252808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buvoli M, Hamady M, Leinwand LA, Knight R. Bioinformatics assessment of beta-myosin mutations reveals myosin’s high sensitivity to mutations. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.PGA C. Genomics of cardiovascular development, adaptation, and remodeling. 2011 NHLBI program for genomic applications, harvard medical school Url: Http://wwwCardiogenomicsOrg 2011.

- 28.Cuda G, Fananapazir L, Epstein ND, Sellers JR. The in vitro motility activity of beta-cardiac myosin depends on the nature of the beta-myosin heavy chain gene mutation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1997;18:275–283. doi: 10.1023/a:1018613907574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lowey S. Functional consequences of mutations in the myosin heavy chain at sites implicated in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:348–354. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00181-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prabhakar R, Boivin GP, Grupp IL, Hoit B, Arteaga G, Solaro JR, Wieczorek DF. A familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy alpha-tropomyosin mutation causes severe cardiac hypertrophy and death in mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1815–1828. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prabhakar R, Petrashevskaya N, Schwartz A, Aronow B, Boivin GP, Molkentin JD, Wieczorek DF. A mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by a alpha-tropomyosin mutation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;251:33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Michele DE, Gomez CA, Hong KE, Westfall MV, Metzger JM. Cardiac dysfunction in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutant tropomyosin mice is transgene-dependent, hypertrophy-independent, and improved by beta-blockade. Circ Res. 2002;91:255–262. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000027530.58419.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geisterfer-Lowrance AA, Kass S, Tanigawa G, Vosberg HP, McKenna W, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. A molecular basis for familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A beta cardiac myosin heavy chain gene missense mutation. Cell. 1990;62:999–1006. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90274-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tyska MJ, Hayes E, Giewat M, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Warshaw DM. Single-molecule mechanics of R403Q cardiac myosin isolated from the mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2000;86:737–744. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.7.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamashita H, Tyska MJ, Warshaw DM, Lowey S, Trybus KM. Functional consequences of mutations in the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain at sites implicated in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:28045–28052. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lowey S, Lesko LM, Rovner AS, Hodges AR, White SL, Low RB, Rincon M, Gulick J, Robbins J. Functional effects of the hypertrophic cardiomyopathy R403Q mutation are different in an {alpha}- or {beta}-myosin heavy chain backbone. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20579–20589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800554200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Georgakopoulos D, Christe ME, Giewat M, Seidman CM, Seidman JG, Kass DA. The pathogenesis of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Early and evolving effects from an alpha-cardiac myosin heavy chain missense mutation. Nat Med. 1999;5:327–330. doi: 10.1038/6549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alpert NR, Mohiddin SA, Tripodi D, Jacobson-Hatzell J, Vaughn-Whitley K, Brosseau C, Warshaw DM, Fananapazir L. Molecular and phenotypic effects of heterozygous, homozygous, and compound heterozygote myosin heavy-chain mutations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1097–1102. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00650.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmiter KA, Tyska MJ, Haeberle JR, Alpert NR, Fananapazir L, Warshaw DM. R403Q and L908V mutant beta-cardiac myosin from patients with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy exhibit enhanced mechanical performance at the single molecule level. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2000;21:609–620. doi: 10.1023/a:1005678905119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keller DI, Coirault C, Rau T, Cheav T, Weyand M, Amann K, Lecarpentier Y, Richard P, Eschenhagen T, Carrier L. Human homozygous R403W mutant cardiac myosin presents disproportionate enhancement of mechanical and enzymatic properties. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Palmer BM, Wang Y, Teekakirikul P, Hinson JT, Fatkin D, Strouse S, Vanburen P, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Maughan DW. Myofilament mechanical performance is enhanced by R403Q myosin in mouse myocardium independent of sex. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1939–1947. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00644.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palmer BM, Fishbaugher DE, Schmitt JP, Wang Y, Alpert NR, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, VanBuren P, Maughan DW. Differential cross-bridge kinetics of FHC myosin mutations R403Q and R453C in heterozygous mouse myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H91–99. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Debold EP, Schmitt JP, Patlak JB, Beck SE, Moore JR, Seidman JG, Seidman C, Warshaw DM. Hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathy mutations differentially affect the molecular force generation of mouse alpha-cardiac myosin in the laser trap assay. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H284–291. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00128.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Belus A, Piroddi N, Scellini B, Tesi C, Amati GD, Girolami F, Yacoub M, Cecchi F, Olivotto I, Poggesi C. The familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-associated myosin mutation R403Q accelerates tension generation and relaxation of human cardiac myofibrils. J Physiol. 2008;586:3639–3644. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.155952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seebohm B, Matinmehr F, Kohler J, Francino A, Navarro-Lopez F, Perrot A, Ozcelik C, McKenna WJ, Brenner B, Kraft T. Cardiomyopathy mutations reveal variable region of myosin converter as major element of cross-bridge compliance. Biophys J. 2009;97:806–824. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miller G, Maycock J, White E, Peckham M, Calaghan S. Heterologous expression of wild-type and mutant beta-cardiac myosin changes the contractile kinetics of cultured mouse myotubes. J Physiol. 2003;548:167–174. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kohler J, Winkler G, Schulte I, Scholz T, McKenna W, Brenner B, Kraft T. Mutation of the myosin converter domain alters cross-bridge elasticity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3557–3562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062415899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirschner SE, Becker E, Antognozzi M, Kubis HP, Francino A, Navarro-Lopez F, Bit-Avragim N, Perrot A, Mirrakhimov MM, Osterziel KJ, McKenna WJ, Brenner B, Kraft T. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy-related beta-myosin mutations cause highly variable calcium sensitivity with functional imbalances among individual muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1242–1251. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00686.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marston SB. How do mutations in contractile proteins cause the primary familial cardiomyopathies? J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 4:245–255. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9266-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blanchard E, Seidman C, Seidman JG, LeWinter M, Maughan D. Altered crossbridge kinetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 1999;84:475–483. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.4.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tardiff JC. Sarcomeric proteins and familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Linking mutations in structural proteins to complex cardiovascular phenotypes. Heart Fail Rev. 2005;10:237–248. doi: 10.1007/s10741-005-5253-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schmitt JP, Debold EP, Ahmad F, Armstrong A, Frederico A, Conner DA, Mende U, Lohse MJ, Warshaw D, Seidman CE, Seidman JG. Cardiac myosin missense mutations cause dilated cardiomyopathy in mouse models and depress molecular motor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14525–14530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606383103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Collins JH. Homology of myosin dtnb light chain with alkali light chains, troponin c and parvalbumin. Nature. 1976;259:699–700. doi: 10.1038/259699a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diffee GM, Patel JR, Reinach FC, Greaser ML, Moss RL. Altered kinetics of contraction in skeletal muscle fibers containing a mutant myosin regulatory light chain with reduced divalent cation binding. Biophys J. 1996;71:341–350. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poetter K, Jiang H, Hassanzadeh S, Master SR, Chang A, Dalakas MC, Rayment I, Sellers JR, Fananapazir L, Epstein ND. Mutations in either the essential or regulatory light chains of myosin are associated with a rare myopathy in human heart and skeletal muscle. Nat Genet. 1996;13:63–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Richard P, Charron P, Carrier L, Ledeuil C, Cheav T, Pichereau C, Benaiche A, Isnard R, Dubourg O, Burban M, Gueffet JP, Millaire A, Desnos M, Schwartz K, Hainque B, Komajda M. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Distribution of disease genes, spectrum of mutations, and implications for a molecular diagnosis strategy. Circulation. 2003;107:2227–2232. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066323.15244.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Flavigny J, Richard P, Isnard R, Carrier L, Charron P, Bonne G, Forissier JF, Desnos M, Dubourg O, Komajda M, Schwartz K, Hainque B. Identification of two novel mutations in the ventricular regulatory myosin light chain gene (myl2) associated with familial and classical forms of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Med. 1998;76:208–214. doi: 10.1007/s001090050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andersen PS, Havndrup O, Bundgaard H, Moolman-Smook JC, Larsen LA, Mogensen J, Brink PA, Borglum AD, Corfield VA, Kjeldsen K, Vuust J, Christiansen M. Myosin light chain mutations in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Phenotypic presentation and frequency in danish and south african populations. J Med Genet. 2001;38:E43. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.12.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harris SP, Lyons RG, Bezold KL. In the thick of it: HCM-causing mutations in myosin binding proteins of the thick filament. Circ Res. 108:751–764. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greenberg MJ, Watt JD, Jones M, Kazmierczak K, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. Regulatory light chain mutations associated with cardiomyopathy affect myosin mechanics and kinetics. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.09.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fenn WO. A quantitative comparison between the energy liberated and the work performed by the isolated sartorius muscle of the frog. J Physiol. 1923;58:175–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1923.sp002115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greenberg MJ, Mealy TR, Jones M, Szczesna-Cordary D, Moore JR. The direct molecular effects of fatigue and myosin regulatory light chain phosphorylation on the actomyosin contractile apparatus. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010 doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00566.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nyitrai M, Geeves MA. Adenosine diphosphate and strain sensitivity in myosin motors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:1867–1877. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Armel TZ, Leinwand LA. A mutation in the beta-myosin rod associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy has an unexpected molecular phenotype. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;391:352–356. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.11.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lowey S, Slayter HS, Weeds AG, Baker H. Substructure of the myosin molecule. I. Subfragments of myosin by enzymic degradation. J Mol Biol. 1969;42:1–29. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90483-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McLachlan AD, Karn J. Periodic charge distributions in the myosin rod amino acid sequence match cross-bridge spacings in muscle. Nature. 1982;299:226–231. doi: 10.1038/299226a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vikstrom KL, Seiler SH, Sohn RL, Strauss M, Weiss A, Welikson RE, Leinwand LA. The vertebrate myosin heavy chain: Genetics and assembly properties. Cell Struct Funct. 1997;22:123–129. doi: 10.1247/csf.22.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cammarato A, Li XE, Reedy MC, Lee CF, Lehman W, Bernstein SI. Structural basis for myopathic defects engendered by alterations in the myosin rod. J Mol Biol. 2011;414:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moss RL, Fitzsimons DP. Regulation of contraction in mammalian striated muscles--the plot thick-ens. J Gen Physiol. 136:21–27. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Naber N, Cooke R, Pate E. Slow myosin ATP turnover in the super-relaxed state in tarantula muscle. J Mol Biol. 411:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cooke R. The role of the myosin atpase activity in adaptive thermogenesis by skeletal muscle. Biophys Rev. 2011;3:33–45. doi: 10.1007/s12551-011-0044-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hooijman P, Stewart MA, Cooke R. A new state of cardiac myosin with very slow ATP turnover: A potential cardioprotective mechanism in the heart. Biophys J. 100:1969–1976. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.02.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Stewart MA, Franks-Skiba K, Chen S, Cooke R. Myosin atp turnover rate is a mechanism involved in thermogenesis in resting skeletal muscle fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:430–435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909468107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liu J, Wendt T, Taylor D, Taylor K. Refined model of the 10s conformation of smooth muscle myosin by cryo-electron microscopy 3d image reconstruction. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:963–972. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00516-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zoghbi ME, Woodhead JL, Moss RL, Craig R. Three-dimensional structure of vertebrate cardiac muscle myosin filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2386–2390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708912105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jung HS, Komatsu S, Ikebe M, Craig R. Head-head and head-tail interaction: A general mechanism for switching off myosin ii activity in cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3234–3242. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lowey S, Trybus KM. Common structural motifs for the regulation of divergent class II myosins. J Biol Chem. 285:16403–16407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.025551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Woodhead JL, Zhao FQ, Craig R, Egelman EH, Alamo L, Padron R. Atomic model of a myosin filament in the relaxed state. Nature. 2005;436:1195–1199. doi: 10.1038/nature03920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Craig R, Woodhead JL. Structure and function of myosin filaments. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alamo L, Wriggers W, Pinto A, Bartoli F, Salazar L, Zhao FQ, Craig R, Padron R. Three-dimensional reconstruction of tarantula myosin filaments suggests how phosphorylation may regulate myosin activity. J Mol Biol. 2008;384:780–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weisberg A, Winegrad S. Alteration of myosin cross bridges by phosphorylation of myosin-binding protein c in cardiac muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:8999–9003. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Winegrad S. Cardiac myosin binding protein c: Modulator of contractility. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;565:269–281. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24990-7_20. discussion 281-262, 405-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kamm KE, Stull JT. Signaling to myosin regulatory light chain in sarcomeres. J Biol Chem. 2012;286:9941–9947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.198697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ventura-Clapier R, Garnier A, Veksler V. Energy metabolism in heart failure. J Physiol. 2004;555:1–13. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.055095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kammermeier H. High energy phosphate of the myocardium: Concentration versus free energy change. Basic Res Cardiol. 1987;82(Suppl 2):31–36. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-11289-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spindler M, Saupe KW, Christe ME, Sweeney HL, Seidman CE, Seidman JG, Ingwall JS. Diastolic dysfunction and altered energetics in the alphaMHC403/+ mouse model of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1775–1783. doi: 10.1172/JCI1940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lodi R, Rajagopalan B, Schapira AH, Cooper JM. Cardiac bioenergetics in friedreich’s ataxia. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:552. doi: 10.1002/ana.10744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lodi R, Rajagopalan B, Blamire AM, Crilley JG, Styles P, Chinnery PF. Abnormal cardiac energetics in patients carrying the A3243G mtDNA mutation measured in vivo using phosphorus MR spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1657:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tanaka T, Sohmiya K, Kawamura K. Is CD36 deficiency an etiology of hereditary hypertrophic cardiomyopathy? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:121–127. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Graham BH, Waymire KG, Cottrell B, Trounce IA, MacGregor GR, Wallace DC. A mouse model for mitochondrial myopathy and cardiomyopathy resulting from a deficiency in the heart/muscle isoform of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Nat Genet. 1997;16:226–234. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hershberger RE, Lindenfeld J, Mestroni L, Seidman CE, Taylor MR, Towbin JA. Genetic evaluation of cardiomyopathy--a heart failure society of america practice guideline. J Card Fail. 2009;15:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Charron P, Arad M, Arbustini E, Basso C, Bilinska Z, Elliott P, Helio T, Keren A, McKenna WJ, Monserrat L, Pankuweit S, Perrot A, Rapezzi C, Ristic A, Seggewiss H, van Langen I, Tavazzi L. Genetic counselling and testing in cardiomyopathies: A position statement of the european society of cardiology working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2715–2726. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ingles J, McGaughran J, Scuffham PA, Atherton J, Semsarian C. A cost-effectiveness model of genetic testing for the evaluation of families with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2012;98:625–630. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wordsworth S, Leal J, Blair E, Legood R, Thomson K, Seller A, Taylor J, Watkins H. DNA testing for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A cost-effectiveness model. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:926–935. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Maron BJ. The young competitive athlete with cardiovascular abnormalities: Causes of sudden death, detection by preparticipation screening, and standards for disqualification. Card Electrophysiol Rev. 2002;6:100–103. doi: 10.1023/a:1017903709361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Maron BJ, McKenna WJ, Danielson GK, Kappenberger LJ, Kuhn HJ, Seidman CE, Shah PM, Spencer WH, 3rd, Spirito P, Ten Cate FJ, Wigle ED. American college of cardiology/european society of cardiology clinical expert consensus document on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. A report of the american college of cardiology foundation task force on clinical expert consensus documents and the european society of cardiology committee for practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1687–1713. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00941-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wang Y, Xu Y, Kerrick WG, Wang Y, Guzman G, Diaz-Perez Z, Szczesna-Cordary D. Prolonged Ca2+ and force transients in myosin rlc transgenic mouse fibers expressing malignant and benign fhc mutations. J Mol Biol. 2006;361:286–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nishimura RA, Holmes DR., Jr Clinical practice. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1320–1327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp030779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Talreja DR, Nishimura RA, Edwards WD, Valeti US, Ommen SR, Tajik AJ, Dearani JA, Schaff HV, Holmes DR., Jr Alcohol septal ablation versus surgical septal myectomy: Comparison of effects on atrioventricular conduction tissue. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:2329–2332. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.van Rooij E, Quiat D, Johnson BA, Sutherland LB, Qi X, Richardson JA, Kelm RJ, Jr, Olson EN. A family of microRNAs encoded by myosin genes governs myosin expression and muscle performance. Dev Cell. 2009;17:662–673. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Montgomery RL, Hullinger TG, Semus HM, Dickinson BA, Seto AG, Lynch JM, Stack C, Latimer PA, Olson EN, van Rooij E. Therapeutic inhibition of miR-208a improves cardiac function and survival during heart failure. Circulation. 2011;124:1537–1547. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.030932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.van Rooij E, Marshall WS, Olson EN. Toward microRNA-based therapeutics for heart disease: The sense in antisense. Circ Res. 2008;103:919–928. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.183426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Thum T, Catalucci D, Bauersachs J. Micrornas: Novel regulators in cardiac development and disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:562–570. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yamazaki T, Suzuki J, Shimamoto R, Tsuji T, Ohmoto-Sekine Y, Ohtomo K, Nagai R. A new therapeutic strategy for hypertrophic nonobstructive cardiomyopathy in humans. A randomized and prospective study with an angiotensin ii receptor blocker. Int Heart J. 2007;48:715–724. doi: 10.1536/ihj.48.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Penicka M, Gregor P, Kerekes R, Marek D, Curila K, Krupicka J. The effects of candesartan on left ventricular hypertrophy and function in nonobstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: A pilot, randomized study. J Mol Diagn. 2009;11:35–41. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2009.080082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cleland JG, Teerlink JR, Senior R, Nifontov EM, Mc Murray JJ, Lang CC, Tsyrlin VA, Greenberg BH, Mayet J, Francis DP, Shaburishvili T, Monaghan M, Saltzberg M, Neyses L, Wasserman SM, Lee JH, Saikali KG, Clarke CP, Goldman JH, Wolff AA, Malik FI. The effects of the cardiac myosin activator, omecamtiv mecarbil, on cardiac function in systolic heart failure: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover, dose-ranging phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2011;378:676–683. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Malik FI, Hartman JJ, Elias KA, Morgan BP, Rodriguez H, Brejc K, Anderson RL, Sueoka SH, Lee KH, Finer JT, Sakowicz R, Baliga R, Cox DR, Garard M, Godinez G, Kawas R, Kraynack E, Lenzi D, Lu PP, Muci A, Niu C, Qian X, Pierce DW, Pokrovskii M, Suehiro I, Sylvester S, Tochimoto T, Valdez C, Wang W, Katori T, Kass DA, Shen YT, Vatner SF, Morgans DJ. Cardiac myosin activation: A potential therapeutic approach for systolic heart failure. Science. 2011;331:1439–1443. doi: 10.1126/science.1200113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lankford EB, Epstein ND, Fananapazir L, Sweeney HL. Abnormal contractile properties of muscle fibers expressing beta-myosin heavy chain gene mutations in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1409–1414. doi: 10.1172/JCI117795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang Q, Moncman CL, Winkelmann DA. Mutations in the motor domain modulate myosin activity and myofibril organization. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4227–4238. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Capek P, Vondrasek J, Skvor J, Brdicka R. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: From mutation to functional analysis of defective protein. Croat Med J. 2011;52:384–391. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2011.52.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]