Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study was to identify factors associated with decision making about inherited cancer risk information within families and determine the interdependence between survivors’ and relatives’ decision making.

Design

A descriptive, cross-sectional design using a population-based sample of 146 dyads (N=292) was used. Analyses included multilevel modeling using the Actor-Partner-Interdependence Model

Main Outcome Measure

Decision making was the main outcome, along with the pros and cons in making a decision regarding inherited cancer risk information.

Results

Overall, results indicate several individual and family factors that survivors and female relatives contribute toward their own and each other’s decision making about inherited cancer risk information. Individual factors included the individual’s perceptions of their family communication and their family’s cancer history. Among family dyadic factors, survivors and family members’ age, communication and coping style influenced the decision making of the other member of the dyad. Cancer worries and a monitoring coping style affected both seeking and avoiding decision making for survivors and their relatives.

Conclusions

In view of the importance of genetic information upon family health outcomes, it is critical to address both individual and family factors that may influence decision making about cancer risk information and surveillance options for all members within the family.

Keywords: Breast/Ovarian Cancer, Decision Making, Family, Inherited Cancer Risk

In 2008, there are expected to be an estimated 182,460 new cases of breast cancer and 21,650 new cases of ovarian cancer in the US (American Cancer Society, 2008), with approximately 5–10% of these cancers attributed to cancer specific genes, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 (Miki et al., 1994; Tavtigian et al., 1996). However, these statistics do not account for the multiple family members who will also be affected by an inherited cancer risk. Recent research suggests that it is essential to include the family’s influence and involvement in genetic risk awareness and decision making, (Bleiker, Hahn, & Aaronson, 2003; Marcus, 1999) because individuals interpret information and make decisions within the context of their families (Marcus, 1999). Although some studies indicate that there is uncertainty and a lack of knowledge related to understanding inherited risk status in these individuals and families (Frost, Venne, Cunningham, & Gerritsen-McKane, 2004; Lanie et al., 2004), we lack empirical information on how decisions are made regarding risk information within families and the interdependence between survivors’ and family members’ decision making.

Using a family decision making model, the purpose of this study was to: 1) determine the extent that sociodemographic and medical factors, personal and family resources, and appraisal factors contributed to cancer survivors’ and unaffected female relatives’ decision making related to inherited cancer risk information; 2) determine the extent to which survivors and relatives influenced one another’s decision making; and 3) assess differences in predictors of decision making between survivors and female relatives.

Background

For the most part, research on decision making with high risk women has been related to individual decisions about genetic counseling/testing (Bluman et al., 1999) risk-reduction surgeries at the time of diagnosis or strong family histories of cancer (Fang et al., 2003; Lynch et al., 2006), with little research on decision making regarding seeking information about one’s personal or family’s potential cancer risk. Studies to date clearly identify there are competing benefits and disadvantages to decisions regarding genetic testing that factor into decision making processes. While advantages include learning of one’s children’s risk, improved screening surveillance and treatment options, and making childbearing decisions (Armstrong et al., 2000; Jacobsen, Valdimarsdottier, Brown, & Offit, 1997; Lerman, Seay, Balshem, & Audrain, 1995), competing disadvantages include stigmatization, increased psychological distress for self and family, insurance discrimination, and worry about accuracy and surveillance options after testing (Armstrong et al., 2000; Jacobsen et al., 1997). However, it is unclear whether similar benefits and disadvantages influence decisions to seek cancer risk information among families who may be at high risk.

One factor that appears to be important in any decision making processes related to inherited cancer risk is an over-estimation of one’s personal cancer risk (Bluman et al., 1999; Lerman et al., 1995). Studies indicate that women interpret information and make decisions based on their own personal experience and the needs and concerns for others within their own families (Manne et al., 2002; Marcus, 1999). Adverse outcomes of genetic information and testing on families include psychological distress in children (Tercyak, Peshkin, Streisand, & Lerman, 2001), poor communication (Forrest et al., 2003), family relationship problems (Manne et al., 2002), and increased distress in managing other family concerns (Halbert et al., 2004). While the importance of the family in decision making for genetic risk cannot be overemphasized, research to date has not examined decision making within the family who may be at risk and the interdependence between family members in their decision making.

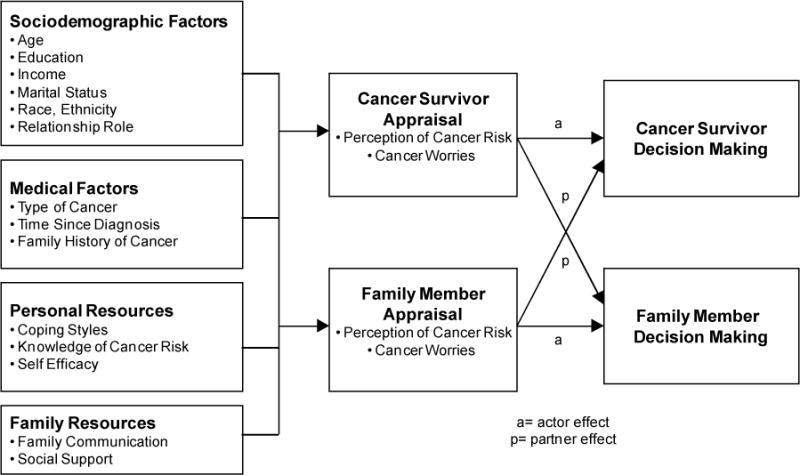

A family decision making model (Figure 1), adapted from the McCubbin and McCubbin’s Resiliency model (McCubbin & McCubbin, 1996) along with several constructs from the transtheoretical model of change (Prochaska et al., 1994; Rakowski, Dube, & Goldstein, 1996), was used to guide this study and the selection of factors that may be associated with individual and family member decision making about inherited cancer risk information.

Figure 1.

Family Decision Making Regarding Inherited Cancer Risk

In addition to the variables identified, the model (Fig 1) specifies that there is an interdependence between the cancer survivor and unaffected female relative in their decision making. A number of studies have documented the effect that patients and family members have on each other in adaptation outcomes and quality of life (Mellon, Northouse, & Weiss, 2006; Northouse, Mood, Templin, Mellon, & George, 2000). Intervention research with families additionally supports that when families are included, important outcomes are noted both in reduced patient and caregiver depression and reduced mortality rates (Martire, Lustig, Schultz, Miller, & Helgeson, 2004). Given the wide-ranging effects that having an inherited cancer risk can mean to an entire family, further research is needed to identify factors that may be important in decision making to assist families in managing the information and in making informed decisions for their family’s health.

Methods

Sample

A population-based sample of women, between the ages of 18 and 79, was identified through the Metropolitan Detroit Cancer Surveillance System (MDCSS), a participant in the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program. The registry collects diagnostic, treatment and demographic information on all individuals diagnosed with cancer in a tri-county area of Metropolitan Detroit. Cases were randomly selected from the registry between the years of 1999 and 2002, after individuals were stratified by race (Caucasian or African American) and cancer site (invasive ovarian and/or breast). Using National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) criteria for assessment of risk of familial breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility, survivors had to be diagnosed with either invasive ovarian cancer at any age, invasive breast cancer at <50 years of age, or invasive breast cancer at any age having a previous, synchronous or subsequent new invasive breast or ovarian cancer. Using these criteria, 674 women were identified.

Additional eligibility criteria were assessed after contacting the potential participant, including confirmation of the cancer diagnosis and having an eligible relative willing to participate in the study. The relatives had to be a first, second or third degree female blood relative, over the age of 17, and no prior diagnosis of cancer. After screening for eligibility, 386 women were able to be contacted and determined eligible. During final accrual, an additional 24 women were ineligible due to lack of a female relative to participate. The final sample was 146 dyads (N=292), with a participation rate of 38%. Those women who declined participation (N=215) cited the following reasons: current participation in a study, lack of interest, medical factors (illness, cancer treatment, or physically challenged), lack of time, refusal to talk about cancer, or unwillingness to approach a family member to participate. We compared survivor participants with eligible non-participants and found no differences between the 2 groups, except for age of ovarian cancer participants. Ovarian participants were significantly older than non-participants (M=49, p=.007).

Procedure

After obtaining institutional review board approval, the procedure for sample accrual followed standard registry protocols. Registry staff notified the potential participant’s physician by letter that she was eligible for the study and requested that the physician inform them if there was any reason the patient should not be contacted. If no response was received from the physician within 3 weeks, the potential participant was sent an invitation letter outlining the study along with a telephone number and response sheet to let us know if she did not want to participate in the study. After two weeks, if the woman did not decline contact, a member of the research team contacted her by telephone to ascertain her interest and to establish if there was an eligible relative to participate with her. Once a woman was selected for the study, with her permission, her name and contact information was forwarded to the data collection team.

The data collection team confirmed the eligibility criteria and scheduled the one-time interview. The interview with the survivor and an unaffected female relative took place in their home, another site selected by the family, or in the investigator’s offices and were conducted by master’s prepared nurses or genetic counselors. Although both members of the family dyad were present during the interview, each person completed the self-report questionnaires independently and was blinded from reviewing their family member’s responses. All participants signed a written consent form prior to participation. The interview took approximately 1 – 1½ hours and all participants received a $25 stipend for their participation.

Measures

Sociodemographic Factors

Personal information related to age, education, income, race, ethnicity, family members, and dyad role relationship (daughter, sister, mother, niece, aunt, other) was obtained through a researcher-designed instrument. Relevant medical information that included cancer history, type of cancer, treatment, recurrence, and genetic counseling or testing was obtained. Family history of cancer was measured using the Family History Assessment Tool (FHAT) (Gilpin, Carson, & Hunter, 2000). Designed originally as a primary care assessment tool to capture individuals at risk for inherited cancer, a scoring system is calculated based on the family history, with a score 10 or greater triggering a genetic counseling referral. Separate scores were calculated for both the survivor and relative, and the highest score for the dyad was used for the entire family’s cancer risk.

Personal Resources

Coping styles was measured with the Miller Behavioral Style Scale (MBSS) (Miller, 1987), comprised of a total of 32 items and two subscales of monitoring and blunting styles. Adequate test-retest reliability and predictive validity (Miller, 1987) has been demonstrated, along with a clear 2-factor solution (Muris & Schouten, 1994). The alpha reliability for the monitoring score was .67 and for the blunting score was .64. A questionnaire by Lerman, Narod, et al. (1996) measured knowledge of cancer risk. While the instrument has a reported high internal reliability, in our population-based study, internal consistency of the scale was not established and we subsequently dropped the instrument from the main analysis. Self efficacy was measured by the General Self-Efficacy subscale (Scherer et al., 1982). Evidence of adequate reliability and construct and criterion validity and reliability has been reported previously (Scherer et al., 1982). In our study, the α coefficient was .81.

Family Resources

Family communication was measured by the Family Relationship Inventory (FRI) (Moos & Moos, 1981), a part of the larger Family Environment Scale, a global measure of family interactions. Evidence of adequate test-retest reliabilities, along with construct and discriminate validity had been reported in other studies (Fredman & Sherman, 1987). For this study, the Cronbach’s α for survivors and family members was .79. Social support was measured using the Personal Resource Questionnaire (PRQ) (Brandt & Weinert, 1981). Documented internal consistency and construct validity have been reported previously (Brandt & Weinert, 1981). For this study, the reliability coefficient was .80.

Appraisal Factors

Perception of cancer risk was measured by a 7-item scale developed by Schwartz et al (Schwartz, Lerman, Miller, Daly, & Masny, 1995). We modified the scale to specifically address perception of risk of inherited breast and/or ovarian cancer for both oneself and added 2 items to determine perception of risk for other family members. For this study, the internal reliability coefficient was α=.75. Cancer worries were measured by a cancer worry scale developed by Lerman and colleagues (1991; McCaul, Branstetter, O’Donnell, Jacobson, & Quinlan, 1998). Evidence of test-retest reliability and internal consistency have been reported in other studies (McCaul et al., 1998). For this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient was .86.

Decision making outcome

A Decisional balance scale was used to measure the decision making outcome of the pros and cons in making a decision to learn about inherited cancer risk information (Jacobsen et al., 1997). Decisional balance is a well-tested and valid outcome measure in research addressing behavioral change (Jacobsen et al., 1997; Manne et al., 2002). The scale used in this study was modeled and adapted from the decisional balance scale used in research on decision making about genetic testing for women at high risk for breast cancer (Jacobsen et al., 1997), with demonstrated internal reliability of the 2 subscales (pros and cons). We adapted the Jacobson 22-item version to emphasize the family dimension of decision making and added 4 new items. The modified scale was reviewed for content validity by experts in the field, including genetic counselors, geneticists, oncologists, and behavioral scientists. Following factor analysis, the final scale of 14 items indicated 2 discrete scales of pros and cons. For this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient was .77 for the pros scale and .78 for the cons scale.

Statistical Analysis

Prior to analysis all variables were examined for accuracy, distributional assumptions of the analyses, and missing values. A single measure representing the average family history of cancer score for each dyad was used in the analysis due to the high correlation between the family history of cancer for the survivors and relatives (r = 0.84, p < .001). Four variables were missing data on one to five cases. The data were missing completely at random and expectation maximization was used to impute the missing cases. The final data set consisted of 289 cases (143 dyads with complete data and three dyads with a single case).

The Actor-Partner Independence Model (APIM) was used to identify the factors associated with decision making while taking into account the effects of survivors and unaffected female relatives on one another (Campbell & Kashy, 2002; Kashy & Kenny, 2000; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). The multilevel approach of the APIM allowed us to examine both individual effects (actor effects) as well as the effects of both members of the dyad on each other at the same time (partner effects). In our study, the dyads were distinguishable from each other by their role (survivor vs. relative). The APIM approach identifies “actor” and “partner” effects in the dyadic analysis. Actor effects refers to an individual’s score (either the survivor or female relative) on a predictor variable affecting their own decision making. The dyadic partner effects refer to an individual’s score on a predictor variable affecting the other member of the dyad’s decision making. Essentially, this means that a survivor influences her female relative’s decision making or conversely, a relative can influence the survivor’s decision making (Kashy & Kenny, 2000). Actor and partner effects are only assessed on mixed variables where the score can differ both within and between the dyads (i.e., age, education, self-efficacy, coping style, communication, social support, cancer worries, perception of cancer risk, decision making). For the other variables where there may be differences within the dyad (survivor vs. unaffected relative) or between dyads in the sample (time since diagnosis; type of cancer; family history of cancer; role relationship – mother/daughter/sister; income; race), main effects were assessed in the APIM.

We used multilevel modeling (or hierarchical linear modeling) to estimate the APIM that looked at the dyads as nested scores within the same group (Campbell & Kashy, 2002; Kashy & Kenny, 2000). This approach to estimate APIM has several advantages over structural equation modeling (SEM) approaches with being less computationally complex, more flexible, and allows the ability to provide direct estimates of the partner or actor effects (Campbell & Kashy). The method outlined for conducting APIM analyses by Campbell and Kashy served as the guide for our analysis plan.

A backward elimination procedure was employed with all possible predictors entered in the first step of the model. Variables significant at p ≤ .05 were retained. To assess differences in predictors of decision making between survivors and relatives, interaction terms for each potential predictor and the role (survivor versus relative) of the individual were also examined in the model. A significant predictor by role interaction indicates that the effect of the predictor on decision making is different for survivors and relatives. After the final model of main effect predictors was determined, interactions significant at p ≤ .20 along with the main effect for the variable were entered into the model. Backward elimination of these effects was then performed to arrive at the final model. Variables that did not have a meaningful value of 0 were centered to enhance the interpretability of the regression coefficients. SPSS MIXED MODELS version 15 was used for the analyses.

Results

Sample Characteristics

The demographic and medical characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. Since the sample was stratified on race, 53.4% of the family dyads were Caucasian and 46.6% were African-American. In regards to medical characteristics, most of the survivors were diagnosed with breast cancer (n=81), over one-third with ovarian cancer (n=50), and 15 women with 2 or more cancers.

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Characteristics of the Study Sample (N=292)

| Characteristics | Cancer Survivor (n=146) | Female Relative (n=146) |

|---|---|---|

| Race (%) | ||

| Caucasian | 78 (53.4) | 78 (53.4) |

| African-American | 68 (46.6) | 68 (46.6) |

| Relationship of Family Member (%) | ||

| Mother | 19 (13.0) | |

| Sister | 52 (35.6) | |

| Daughter | 64 (43.8) | |

| Other (half-sister, aunt, cousin) | 11 (7.6) | |

| Age | ||

| Mean | 51 years | 41 years |

| Range | 25–78 | 18–85 |

| Education (%) | ||

| < high school | 10 (6.9) | 12 (8.2) |

| High school | 36 (24.7) | 34 (23.3) |

| Some college | 45 (31.0) | 56 (38.4) |

| College or post-grad | 54 (37.5) | 44 (30.1) |

| Marital Status (%) | ||

| Married | 83 (57.7) | 58 (39.7) |

| Separated | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.7) |

| Widowed | 11 (7.5) | 13 (8.9) |

| Divorced | 23 (15.8) | 16 (11.0) |

| Single | 25 (17.1) | 53 (36.3) |

| Other | 1 (.7) | 2 (1.4) |

| Family Annual Income (%) | ||

| <$5,000 | 7 (4.8) | 8 (5.5) |

| $5001–15,000 | 9 (6.2) | 13 (8.9) |

| $15,001–30,000 | 19 (13.0) | 40 (27.4) |

| $30,001–50,000 | 40 (27.4) | 32 (21.9) |

| $50,001–75,000 | 39 (26.7) | 24 (16.4) |

| >$75,000 | 32 (21.9) | 27 (18.5) |

| Employment Status (%) | ||

| Employed | 94 (64.4) | 103 (70.5) |

| Retired | 22 (15.1) | 15 (10.3) |

| Homemaker | 12 (8.2) | 15 (10.3) |

| Not Employed | 18 (12.3) | 13 (8.9) |

|

| ||

| Cancer Site (%) | ||

| Breast | 81 (55.5) | |

| Ovarian | 50 (34.2) | |

| Multiple | 15 (10.3) | |

| Time Since Diagnosis | 3–17 yrs (Breast), 2–6 (Ov) | |

| Recurrence | 22 | |

| Currently under Rx | 8 | |

| Genetic Counseling (%) | 15 (10.3) | 5 (3.4) |

| Genetic Testing | 11 (7.5) | 1 (.7) |

Results for the Overall Decisional Balance Summary

The bivariate results using the APIM model are presented in Table 2. At the dyad level, family history of cancer was related to decision making. There were significant actor effects (when an individual’s score on a predictor variable affects her own decision making) for general self efficacy, family communication, and social support. There were also partner effects (when a survivor or relative’s score on the predictor variable affects the other member of the dyad’s decision making) for age and coping style.

Table 2.

Bivariate Relationship of each of the Model Variables and Decisional Balance Summary using the APIM

| Model Variables | β | p | Model Variables | β | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Factors | Personal Resources | ||||

| Age | Coping Style | ||||

| Actor Effect | 0.04 | 0.48 | Actor Effect | −0.03 | 0.86 |

| Partner Effect | −0.13 | 0.01 | Partner Effect | 0.55 | 0.03 |

| Education | General Self Efficacy | ||||

| Actor Effect | −0.32 | 0.60 | Actor Effect | 0.19 | 0.01 |

| Partner Effect | −0.86 | 0.15 | Partner Effect | −0.01 | 0.88 |

| Income | Family Resources | ||||

| Actor Effect | −0.43 | 0.40 | Family Communication | ||

| Partner Effect | −0.38 | 0.46 | Actor Effect | 0.55 | 0.001 |

| Marital Status (married vs. not married) | Partner Effect | −0.47 | 0.01 | ||

| Actor Effect | 0.51 | 0.46 | Perceived Social Support | ||

| Partner Effect | 0.37 | 0.59 | Actor Effect | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Race | Partner Effect | −0.09 | 0.09 | ||

| Caucasian vs. Black | −0.43 | 0.77 | Appraisal | ||

| Relationship of Relative | 0.40a | Perception of Cancer Risk | |||

| Other vs. Mother | −3.85 | 0.28 | Actor Effect | −0.07 | 0.94 |

| Daughter vs. Mother | −1.65 | 0.47 | Partner Effect | 1.42 | 0.14 |

| Sister vs. Mother | 0.42 | 0.86 | Appraisal of Cancer Worries | ||

| Role | Actor Effect | −0.62 | 0.48 | ||

| Survivor vs. Relative | 1.21 | 0.38 | Partner Effect | −0.47 | 0.59 |

| Medical Factors | |||||

| Cancer Type | 0.07a | ||||

| Ovarian vs. Breast | 2.04 | 0.19 | |||

| Multiple vs. Breast | −3.87 | 0.13 | |||

| Time Since Diagnosis | −0.10 | 0.70 | |||

| Family History of Cancer | 8.29 | 0.01 | |||

Significance of overall effect.

The final model for decisional balance summary containing the main effects and interactions is presented in Table 3. When there is a significant predictor by role interactions, this indicates that the effect of the predictor on decision making is different for survivors and relatives. In the final model, family history of cancer remained significant. There was also an effect for years since the first diagnosis of cancer, which was moderated by the role of the women (survivors and relatives). Survivors were less likely to make a decision to seek cancer risk information as their year since diagnosis was further away (β = −.63, p = 0.056). However, there was no relationship between years since first diagnosis and decision making for relatives (β = .37, p = 0.272). The single actor effect in the final model was family communication. Higher levels of communication were related to decisions to seek cancer risk information.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates of Fixed Effects predicting Decisional Balance Summary in Final Model

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Parameter Estimate (β) | Standard Error | Approx. df | t | Sig. | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Intercept | −0.201 | 0.988 | 278 | −0.20 | 0.839 | −2.147 | 1.745 |

| Years Since Diagnosis | −0.633 | 0.330 | 277 | −1.92 | 0.056 | −1.283 | 0.017 |

| Role (Survivor vs. relative) | 0.629 | 1.398 | 156 | 0.45 | 0.653 | −2.131 | 3.390 |

| Age of Partner* | −0.140 | 0.054 | 278 | −2.59 | 0.010 | −0.246 | −0.033 |

| Family History of Cancer | 8.083 | 3.266 | 136 | 2.48 | 0.015 | 1.626 | 14.541 |

| Family Communication | 0.613 | 0.168 | 236 | 3.65 | <0.001 | 0.282 | 0.943 |

| Family Communication of Partner* | −0.429 | 0.168 | 235 | −2.55 | 0.011 | −0.759 | −0.098 |

| Coping Style of Partner* | 0.492 | 0.242 | 279 | 2.03 | 0.043 | 0.016 | 0.968 |

| Role by Years Since Dx (Interaction) | 1.007 | 0.441 | 158 | 2.28 | 0.024 | 0.134 | 1.878 |

Partner’s effect on both survivor and relative.

Partner effects (the influence of the survivor and relative on each other) in the final model included age, family communication and coping style. The effects for age and coping style were similar to those for the individual effects listed above. In the final model, the partner’s family communication was negatively related to decision making. This indicates that the higher the partner’s communication (for both the survivor and female relative), the less likely the other member of the dyad was to seek cancer risk information.

The interrelationship between survivors’ and relatives’ decision making was assessed with the partial intraclass correlation for the final model. The partial intra-class correlation was .09, which was not significant (p = 0.13). The small magnitude of this correlation points to a weak interrelationship between the survivors’ and relatives’ overall decision making.

Results for Decisional Balance Pros

Another set of APIM analyses was done to determine what specific predictors affected women’s decision to seek risk information. The final model for decisional balance pros containing the main effects and interactions is presented in Table 4. At the dyad level, the number of years since the first cancer diagnosis was positively related to decision making pros. The relationship of the relative, which was also a dyad level predictor, was also related to pros for decision making, although this effect was moderated by the role of the women. For survivors, the relationship of the relative was not related to pros toward the decision to seek cancer risk information. For the relative, however, mothers of survivors had more pros for seeking information than daughters of survivors. Actor effects in the final model included marital status, family communication, coping style, and appraisal of cancer worries. Married women had fewer pros for seeking information. Women with higher family communication, higher monitoring coping styles, and more cancer worries had more pros for seeking information. Partner effects in the final model included partner age and education. When the partner was older and when the partner had more education, the women had fewer pros to make a decision to seek cancer risk information. The partial intra-class correlation for the final model was 0.16 (p = .03), indicating that after controlling for all the predictors, there was a significant and fairly strong relationship between survivors’ and relatives’ decisional balance pros. This suggests there was a mutual interdependence between survivors and relatives in their decision to seek cancer risk information.

Table 4.

Parameter Estimates of Fixed Effects predicting Decisional Balance Pros in Final Model

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Parameter Estimate (β) | Standard Error | Approx. df | t | Sig. | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Intercept | 55.742 | 2.811 | 267 | 19.83 | <0.001 | 50.206 | 61.277 |

| Years Since Diagnosis | 0.498 | 0.213 | 140 | 2.34 | 0.021 | 0.078 | 0.919 |

| Relationship of Relative | 0.301a | ||||||

| Other vs. Mother | −6.318 | 3.757 | 265 | −1.68 | 0.094 | −13.716 | 1.079 |

| Daughter vs. Mother | −2.237 | 2.912 | 264 | −0.77 | 0.443 | −7.971 | 3.497 |

| Sister vs. Mother | −0.596 | 2.526 | 264 | −0.24 | 0.814 | −5.570 | 4.378 |

| Role (Survivor vs. relative) | 5.202 | 2.828 | 151 | 1.84 | 0.068 | −0.386 | 10.790 |

| Age of Partner* | −0.169 | 0.054 | 262 | −3.12 | 0.002 | −0.275 | −0.062 |

| Education of Partner* | −1.110 | 0.462 | 271 | −2.40 | 0.017 | −2.019 | −0.201 |

| Marital Status | 1.427 | 0.553 | 268 | 2.58 | 0.010 | 0.338 | 2.517 |

| Family Communication | 0.255 | 0.125 | 259 | 2.04 | 0.042 | 0.009 | 0.500 |

| Coping Style | 0.437 | 0.145 | 268 | 3.01 | 0.003 | 0.152 | 0.723 |

| Appraisal of Cancer Worries | 3.118 | 0.673 | 271 | 4.64 | <0.001 | 1.793 | 4.442 |

| Role by Relationship of Relative (Interaction) | 0.009a | ||||||

| Role by Other vs. Mother | 6.515 | 4.950 | 155 | 1.32 | 0.190 | −3.262 | 16.293 |

| Role by Daughter vs. Mother | −6.801 | 3.691 | 192 | −1.84 | 0.067 | −14.082 | 0.479 |

| Role by Sister vs. Mother | −3.825 | 3.224 | 147 | −1.19 | 0.237 | −10.197 | 2.547 |

Significance of overall effect.

Partner’s effect on both survivor and relative.

Results for Decisional Balance Cons

We were also interested to see what factors specifically predicted against decisions to seek cancer risk information. The final model for decisional balance cons containing the main effects and interactions is presented in Table 5. At the dyad level, the effects of cancer type and family history of cancer risk on cons were moderated by the role of the women. For survivors only, their cancer type was related to cons for seeking cancer risk information with multiple cancer survivors and breast cancer survivors having more cons then ovarian survivors. The effect of history of cancer risk was significant for relatives with higher cancer history related to fewer decision making cons (β = −9.95, p = 0.006). For survivors, the family history of cancer did not predict their cons (β = 2.17, p = 0.541). Actor effects in the final model included general self efficacy, coping style, and appraisal of cancer worries. Women with higher self efficacy had fewer cons for seeking information, whereas women with higher monitoring coping style and more cancer worries had more cons for seeking information. There were no partner effects in the final model. The partial intraclass correlation in the final model was 0.07, which was not significant (p = 0.19). The small magnitude of this correlation points to a weak interrelationship between the survivors’ and relatives’ decisional balance cons.

Table 5.

Parameter Estimates of Fixed Effects predicting Decisional Balance Cons in Final Model

| 95% Confidence Interval | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Parameter Estimate (β) | Standard Error | Approx. df | t | Sig. | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Intercept | 50.687 | 1.036 | 276 | 48.92 | <0.001 | 48.647 | 52.727 |

| Cancer Type | 0.003a | ||||||

| Ovarian vs. Breast | −4.438 | 1.729 | 276 | −2.57 | 0.011 | −7.841 | −1.035 |

| Multiple vs. Breast | 3.957 | 2.647 | 277 | 1.50 | 0.136 | −1.253 | 9.168 |

| Role (Survivor vs. relative) | −1.248 | 1.425 | 139 | −0.88 | 0.383 | −4.066 | 1.569 |

| Family History of Cancer | 2.170 | 3.545 | 277 | 0.61 | 0.541 | −4.810 | 9.149 |

| General Self Efficacy | −0.242 | 0.060 | 278 | −4.07 | 0.000 | −0.360 | −0.125 |

| Coping Style | 0.376 | 0.147 | 278 | 2.56 | 0.011 | 0.086 | 0.666 |

| Appraisal of Cancer Worries | 2.872 | 0.665 | 271 | 4.32 | 0.000 | 1.563 | 4.182 |

| Role by Cancer Type (interaction) | 0.019 | ||||||

| Role by Ovarian vs. Breast | 6.554 | 2.357 | 135 | 2.78 | 0.006 | 1.891 | 11.216 |

| Role by Multiple vs. Breast | 0.270 | 3.691 | 150 | 0.07 | 0.942 | −7.024 | 7.564 |

| Role by Family History of Cancer (interaction) | −12.118 | 4.887 | 139 | −2.48 | 0.014 | −21.780 | −2.455 |

Significance of overall effect.

Discussion

This was one of the first studies to examine decision making about seeking inherited cancer risk information from a family dyadic perspective using a population-based sample. The findings of this study indicate that there are several important factors that family members (both survivors and female relatives) contribute toward each other’s decision making about inherited cancer risk.

A family history of cancer, family communication, the partner’s age, partner’s communication and partner’s coping style were significant predictors for both survivor’s and female relative’s decision making. A family history of cancer appears to be a key factor in making decisions about seeking risk information, a finding that has been also validated in other research (Babb et al., 2002; Bluman et al., 1999). Family communication was another significant factor, both from an “actor” as well as a “partner” perspective. When individuals reported that their family communication was high, there was a decision to seek more risk information.

However, there was a contradictory effect with the partner communication. When the partner (both survivor and female relative) reported higher family communication, there was less of a likelihood to make a decision to seek information. Essentially, this opposite or negative effect of the partner creates a type of collateral damage on the decision making of their family member, potentially cancelling out the decision to seek cancer risk information. This suggests that modification of communication may be difficult if one member is receptive, while the other may have a negative impact on their partner. However, while there may be variation in responses to account for in families facing potential hereditary cancer risk, it potentially suggests that health providers need to include multiple family members in discussions about genetic cancer risk and provide resources to survivors to share with family members that ensures accurate medical information is given to family members that may influence their decision making to seek risk information.

There were several other “partner” effects for the main decision making results. When the partner was older, there was less interest on the part of the survivor or relative to decide to seek information. Additionally, the partner’s coping style was a significant factor toward the decision to seek risk information. Those partners (both survivor and relative) who had a higher monitoring style contributed to their family member’s decision to seek information. While an individual’s monitoring coping style has been supported in previous research regarding genetic information or screening (Lerman, Schwartz et al., 1996), this study further extends these findings and suggests that an individual family member’s coping style influences the decision making of the other member of the family dyad. Clinical implications suggest that providers need to emphasize the inclusion of family members in discussions about potential inherited cancer risk since they are influential in the survivor’s or at-risk relative’s ultimate decision. Decisional aids and educational tools have potential to be developed that could provide information to assist both the survivor and the family member in deciding about risk information.

Since decision making is a complex process for both individuals and relatives, factors that specifically contributed to individuals deciding to seek cancer risk information and factors that served as barriers against decision making revealed several interesting findings. An individual’s cancer worries and coping style (both survivor and female relative) were significant factors in both the pros and cons to seek cancer risk information. This suggests that cancer worries and a monitoring coping style of vigilant scanning present uncertainty about what to do in making a decision to find cancer risk information. This also may have accounted for the weak interrelationship between survivors and relatives in their overall decision making with both pros and cons of cancer worries and coping style essentially cancelling out overall decision making to seek cancer risk information. Women may be both interested to do something about their possible cancer risk, while at the same time concerned and fearful of finding out this information.

Recent studies indicate that cancer screening or preventive practices are not increased after receiving genetic test results and counseling (Lerman et al., 2000; Peshkin et al., 2002) and do not necessarily translate into behavioral change (Marteau & Lerman, 2001). The level of uncertainty and cancer worry may translate into indecisiveness about whether they want to know about their potential cancer risk or not. This suggests several clinical implications of addressing the cancer worries that are present with individuals with cancer histories and potential ambivalence and uncertainty. Cancer worry is a factor that can be modified through direct discussion about realistic risk perceptions, proper management of cancer worries, and provision of accurate information about hereditary cancer risk.

Additional socio-demographic factors influenced decision making to find out risk information. The higher the partner’s education (both survivor and relative), the less likely to make the decision, possibly suggesting the reliance of family members on each other’s knowledge in further seeking out cancer risk information. As well, those women who were married were less likely to seek information. Self-efficacy was another factor important in decisions against seeking risk information. We found that the lower the individual’s sense of confidence in her capabilities, the higher her likelihood of not making the decision to seek information. This may signal that self-efficacy is an important attribute or protective factor for individuals when dealing with inherited cancer risk, and can be a potential factor that can assist individuals in dealing with potential inherited cancer. Encouraging and empowering survivors and family members to seek additional information may foster a sense of self-efficacy and control.

There were also several important differences between survivors and their relatives that warrant consideration in decision making. Survivors who were further out from diagnosis were less likely to make a decision to seek risk information. This has clinical implications for introducing inherited cancer risk information earlier since families may be less likely to talk about cancer-related concerns on risk as more time passes (Mellon, et al., 2006; Rimer et al., 1996). It is important for clinicians to introduce the topic of inherited cancer risk earlier during treatment and survivorship, and also to include family members in this discussion with possible referrals for genetic counseling. Additionally, the type of cancer also made a difference with survivors. Ovarian cancer survivors were more likely to seek risk information. However, for unaffected relatives, differences were noted in the type of relationship. Mothers were more likely than daughters to make decisions to seek information, possibly indicating mothers’ concerns about their offspring’s and family’s possible cancer risk. As has been shown by other studies, (Jacobsen et al., 1997; Lerman, Seay et al., 1995), relatives with stronger family histories of cancer were more likely to decide to seek risk information, indicating the strong influence of the family cancer history on information seeking. These differences suggest that clinicians need to be cognizant of the various cancer diagnoses within a family and how they present different information needs (such as ovarian) as well as varied family role relationships to address individual family member needs about inherited cancer risk.

While the results of this study signify important individual and family implications, there were some limitations. Although we based our study on a theoretical model, several other potential variables could have been included, such as cancer-specific distress or anxiety (van Oostrom et al., 2003), concurrent family stressors (Northouse, et al, 2002) and decisional conflict (O’Connor, 1995). A second limitation is the retrospective, cross-sectional design of the study. Prospective, longitudinal studies are needed in order to determine if decision making about cancer risk changes over time. Another limitation is that we included only female family dyads in this study. Inclusion of other family relationships, particularly spouses, would be important to determine if other family relationships affect decision making of families. Future research could use a Social Relation Model to examine family decision making in more depth. Finally, one of our measures for knowledge of cancer did not demonstrate reliability and we subsequently dropped it from the main analysis. Future research needs to examine knowledge regarding inherited cancer risk and how pre-existing knowledge influences decision making within a family for further risk information.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this study indicate there are important individual and family factors that influence decision making about inherited cancer risk information for both survivors and unaffected female relatives and the interdependence in their decision making. Among individual factors, each person’s own perception of her family communication and family history of cancer significantly contributed to her own decision making. Cancer worries and a monitoring coping style were also important factors toward both seeking and avoiding decision-making for both survivors and their relatives. Among dyadic family factors, the age of the partner, the partner’s communication and coping style influenced the decision making of the other family member. In view of the importance of genetic information upon family health outcomes, it is critical to address both individual and family factors that may influence decision making about cancer risk information and surveillance options for all members within the family.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: This study was supported by a grant from NIH, NINR #R21 NR008584-01

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2008. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong K, Calzone K, Stopfer J, Fitzgerald G, Coyne J, Weber B. Factors associated with decisions about clinical BRCA1/2 testing. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2000;9:1251–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb SA, Swisher EM, Heller HN, Whelan AJ, Mutch DG, Herzog TJ, et al. Qualitative evaluation of medical information processing needs of 60 women choosing ovarian cancer surveillance or prophylactic oophorectomy. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2002;11:81–96. doi: 10.1023/A:1014571420844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleiker EMA, Hahn DEE, Aaronson NK. Psychosocial issues in cancer genetics. Acta Oncologica. 2003;42:276–286. doi: 10.1080/02841860310004391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluman LG, Rimer BK, Berry DA, Borstelmann N, Iglehart JD, Regan K, et al. Attitudes, knowledge, and risk perceptions of women with breast and/or ovarian cancer considering testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1999;17:1040–1046. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt PA, Weinert C. The PRQ – a social support measure. Nursing Research. 1981;30:277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, Kashy DA. Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Personal Relationships. 2002;9(3):327–342. [Google Scholar]

- Fang CY, Miller SM, Malick J, Babb J, Hurley KE, Engstrom PF, et al. Psychosocial correlates of intention to undergo prophylactic oophorectomy among women with a family history of ovarian cancer. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37(5):424–431. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00163-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrest K, Simpson SA, Wilson BJ, van Teijlingen ER, McKee L, Haites N, et al. To tell or not to tell: Barriers and facilitators in family communication about genetic risk. Clinical Genetics. 2003;64:317–326. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman N, Sherman R, editors. Handbook of measurements for marriage and family therapy. New York: Brunner Mazal; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Frost CJ, Venne V, Cunningham D, Gerritsen-McKane R. Decision making with uncertain information: Learning from women in a high risk breast cancer clinic. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2004;13(3):221–236. doi: 10.1023/B:JOGC.0000027958.02383.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilpin CA, Carson N, Hunter AG. A preliminary validation of a family history assessment form to select women at risk for breast or ovarian cancer for referral to a genetics center. Clinical Genetics. 2000;58:299–308. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2000.580408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbert CH, Schwartz MD, Wenzel L, Narod S, Peshkin BN, Cella D, et al. Predictors of cognitive appraisals following genetic testing for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27(4):373–392. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000042411.56032.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PB, Valdimarsdottier HB, Brown KL, Offit K. Decision-making about genetic testing among women at familial risk for breast cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1997;59:459–466. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199709000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Kenny DA. The analysis of data from dyads and groups. [references] In: Reis HT, Jedd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 451–477. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. New York, NY: The Guildford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lanie AD, Jayaratne TE, Sheldon JP, Kardia SLR, Anderson ES, Feldbaum M, et al. Exploring the public understanding of basic genetic concepts. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2004;13(4):305–320. doi: 10.1023/b:jogc.0000035524.66944.6d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Hughes C, Croyle RT, Main D, Durham D, Snyder C, et al. Prophylactic surgery decisions and surveillance practices one year following BRCA1/2 genetic testing. Preventive Medicine. 2000;31:75–80. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2000.0684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Seay J, Balshem A, Audrain J. Interest in genetic testing among first-degree relatives of breast cancer patients. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1995;57:385–392. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320570304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Narod S, Schulman K, Hughes C, Gomez-Caminero A, Bonney G, et al. BRCA1 testing in families with hereditary breast-ovarian cancer. A prospective study of patient decision making and outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275(24):1885–1892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Schwartz MD, Miller SM, Daly M, Sands C, Rimer BK. A randomized trial of breast cancer risk counseling: Interacting effects of counseling, educational level, and coping style. Health Psychology. 1996;15(2):75–83. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Jepson C, Brody D, Boyce A. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychology. 1991;10(4):259–267. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch HT, Snyder C, Lynch JF, Karatoprakli P, Trowonou A, Metcalfe K, et al. Patient responses to the disclosure of BRCA mutation tests in hereditary breast-ovarian cancer families. Cancer Genetics and Cytogenetics. 2006;165:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Markowitz A, Winawer S, Meropol NJ, Haller D, Rakowski W, et al. Correlates of colorectal cancer screening compliance and stage of adoption among siblings of individuals with early onset colorectal cancer. Health Psychology. 2002;21:3–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus AC. New directions for risk communication research: A discussion with additional suggestions. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs. 1999;25:35–42. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Lerman C. Genetic risk and behavioural change. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed) 2001;322(7293):1056–1059. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7293.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schultz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychology. 2004;23(6):599–611. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaul KD, Branstetter AD, O’Donnell SM, Jacobson K, Quinlan KB. A descriptive study of breast cancer worry. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;21(6):565–579. doi: 10.1023/a:1018748712987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI. Resiliency in families: A conceptual model of family adjustment and adaptation in response to stress and crises. In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA, editors. Family assessment: Resiliency, coping, and adaptation – inventories for research and practice. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin System; 1996. pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mellon S, Berry-Bobovski L, Gold R, Levin N, Tainsky M. Communication and decision-making about seeking inherited cancer risk information: Findings from female survivor-relative focus groups. Psychooncology. 2006;15:193–208. doi: 10.1002/pon.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellon S, Northouse LL, Weiss LK. A population-based study of the quality of life of cancer survivors and their family caregivers. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29(2):120–131. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200603000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki Y, Swenson J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Futreal PA, Harshman K, Tavtigian S, et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266:66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SM. Monitoring and blunting: Validation of a questionnaire to assess styles of information seeking under threat. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1987;52:345–353. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Family environment scale manual. California: Consulting Psychologists; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Schouten E. Monitoring and blunting: A factor analysis of the Miller behavioral style scale. Personality & Individual Differences. 1994;17:285–287. [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Mood D, Kershaw T, et al. Quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4050–4064. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northouse LL, Mood D, Templin T, Mellon S, George T. Couples’ patterns of adjustment to colon cancer. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;50:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00281-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Medical Decision Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peshkin BN, Schwartz MD, Isaacs C, Hughes C, Main D, Lerman C. Utilization of breast cancer screening in a clinically based sample of women after BRCA1/2 testing. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2002;11:1115–1118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, Goldstein MG, Marcus BH, Rakowski W, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychology. 1994;13:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakowski W, Dube CA, Goldstein MG. Considerations for extending the transtheoretical model of behavior change to screening mammography. Health Education, Research: Theory & Practice. 1996;11:77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Rimer BK, Schildkraut JM, Lerman C, Lin TH, Audrain J. Participation in a women’s breast cancer risk counseling trial. who participates? who declines? high risk breast cancer consortium. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2348–2355. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960601)77:11<2348::AID-CNCR25>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer M, Maddux JE, Mercandante B, Prentice-Dunn S, Jacobs B, Rogers RW. The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports. 1982;51:663–671. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MD, Lerman C, Miller SM, Daly M, Masny A. Coping disposition, perceived risk, and psychological distress among women at increased risk for ovarian cancer. Health Psychology. 1995;14:232–235. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.3.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavtigian SV, Simard V, Rommens J, Couch J, Shattuck-Eidens D, Neuhausen S, et al. The complete BRCA2 gene and mutations in chromosome 13q-linked kindreds. Nature Genetics. 1996;12(3):333–337. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tercyak KP, Peshkin BN, Streisand R, Lerman C. Psychological issues among children of hereditary breast cancer gene (BRCA1/2) testing participants. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10:336–346. doi: 10.1002/pon.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oostrom I, Meijers-Heijboer H, Lodder LN, Duivenvoorden HJ, van Gool AR, Seynaeve C, et al. Long-term psychological impact of carrying a BRCA1/2 mutation and prophylactic surgery: A 5-year follow-up study. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(20):3867–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]