Abstract

This brief report describes results on study retention among minority men who have sex with men (MSM) from a 12-week, social networking-based, HIV prevention trial with 1-year follow-up. Participants, primarily minority MSM, were recruited using online and offline methods and randomly assigned to a Facebook (intervention or control) group. Participants completed a baseline survey and were asked to complete 2 follow-up surveys (12-week follow-up and 1-year post-intervention). Ninety-four percent (94%) of participants completed the first two surveys and over 82% completed the baseline and both post-intervention surveys. Participants who spent a greater frequency of time online had almost twice the odds of completing all surveys. HIV negative participants, compared to those who were HIV positive, had over 25 times the odds of completing all surveys. HIV prevention studies on social networking sites can yield high participant retention rates.

Keywords: recruitment, retention, social networking technologies, social media

The Internet has been an effective tool in clinical research for quickly recruiting large participant samples [1–3]. However, retaining participants in these studies has been difficult [4, 5]. Retention has generally been below 70%, with the lowest retention rates in longer study intervals and among minority populations [2, 6, 7].

Social networking platforms have rapidly increased in membership, allowing them to be potentially useful tools for increasing participant retention in research studies [8]. Social networking technologies (e.g., Facebook), allow people to use multi-media communication methods, including chatting, sending pictures, and sharing videos [9]. Minority populations, such as African Americans and Latinos, are the fastest growing social networking users [10], supporting findings that these populations find social networking technologies to be acceptable and engaging platforms for health research [11]. The multiple features in social networking sites, such as chatting, sending message, making wall posts, and uploading videos, can be used to enhance more traditional Internet retention methods. Because participants are already communicating via social networking technologies, these technologies might be easily integrated into clinical research as tools for increasing participant retention.

This brief report describes results on overall study retention as well as predictors of retention in the Harnessing Online Prevention Education (HOPE) UCLA study, a social networking-based, 12-week, randomized controlled HIV prevention trial with 1-year follow-up.

METHODS

This study was approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Institutional Review Board. This study conforms to current recommendations on using social networking technologies for HIV prevention research [8].

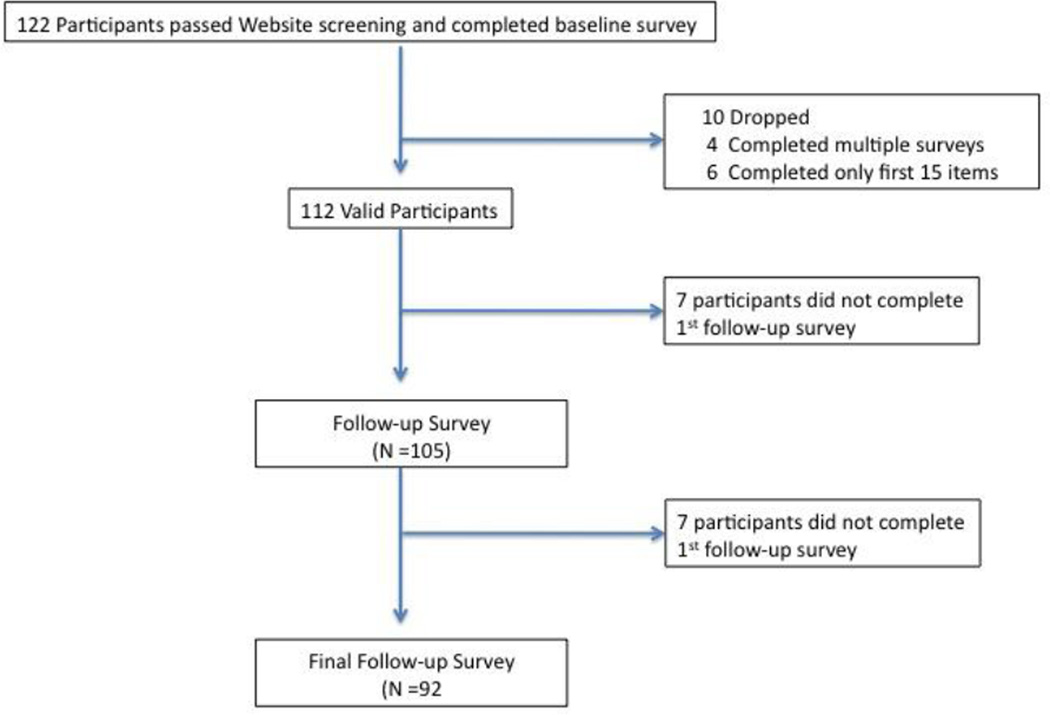

One hundred and twenty-two (122) participants were recruited over 5 months from 2011–2012 as part of a randomized controlled trial on Facebook. The social media-based peer-led HIV prevention intervention was designed to test whether participants receiving HIV prevention information over closed Facebook groups, compared to those receiving general health information over closed Facebook groups, would be more likely to request an HIV self-testing kit and report decreased sexual risk behaviors [12]. Six participants completed only the initial survey items and were dropped from the study. Four participants were found to have completed multiple surveys. The second of their responses was included.

Participants were recruited through online and offline methods. Participants were recruited online through the following methods: 1) a Facebook fan page listing study information 2) Website banner advertisements or posts on Craigslist, and 3) paid targeted banner ads and outreach on social networking sites, such as Facebook and Myspace. Participants recruited offline were recruited both through the help of local organizations and clinics (such as the Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center), bars, and venues serving men who have sex with men (MSM). These venues were provided fliers to distribute that were culturally-tailored to African American and/or Latino MSM. Participants were also able to refer other participant and were not paid for their referrals.

Interested participants were provided with a link to a webpage with contact information and study details. Participants were screened to ensure they fit inclusion criteria: male, 18 years of age or older, living in Los Angeles, has a Facebook account, and has had sex with a man in the past 12 months. Participants consented to the study online. In order to recruit predominantly minority participants, we first recruited 70% of the sample from African American and/or Latino populations, then opened enrollment to MSM from other populations.

Facebook Connect is an application created by Facebook that can be used to validate whether someone is a current Facebook user. This tool can also be used in online studies to reduce the likelihood that participants will respond to multiple surveys (repeat respondents) [8]. After completing eligibility screening and consent, participants were requested to input their Facebook username and password into Facebook Connect to verify that they were uniquely registered Facebook users. After Facebook verified the participant’s status, he was asked to input his email address and contact phone number, and sent a notification ‘thank you’ email stating that he would be contacted once the study was ready to begin.

After 112 participants had been enrolled and completed a baseline survey, the study was ready to begin. Participants were paid $30 in gift cards to an online store to complete the baseline survey and were randomly assigned to one of two HIV intervention or general health (control) groups. Over 12-weeks, participants in each group received group-specific content from African American and Latino MSM peer leaders who had been recruited and trained in ways to communicate online about either HIV prevention (HIV intervention group) or general health (control group) [12, 13]. Participants were paid $40 in gift cards to complete a post-intervention (12-week follow-up) survey. After completion of the 12-week randomized controlled trial, the Facebook groups remained online but participants and peer leaders in both conditions were informed that the study had officially ended. Participants were sent a personal email and received a group wall post informing them they could receive a free HIV testing kit at 6-months post-intervention. Participants were contacted 1 year after completing the post-intervention survey and offered $50 in gift cards to complete a final (1-year follow-up) survey (approximately 15 months after completing the baseline survey). For each survey, participants were contacted initially through personal email. If they did not respond through this method they were then contacted additional times, through personal email, Facebook email, Facebook wall posts, and the phone numbers they provided during consent. Participants were also able to respond to the group Facebook wall posts.

The 92-item survey included questions on demographics, social media and Internet use, sexual and drug-related risk behaviors, HIV status, and perceptions of HIV stigma. Demographics items focused on age, race, place of birth, income and education. Social media and Internet use questions addressed issues such as the amount of time spent online and comfort using the Internet to seek health information. Sexual and drug-related items addressed participant likelihood of engaging in sexual and drug risk behaviors, such as unprotected sex and use of drugs or alcohol during sex. HIV status items asked about experience testing for HIV and receiving results from this test, such as “How many times have you tested for HIV in the past 3 years?” Additional information is available regarding study main outcomes and results [14].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics on demographic information, recruitment methods, intervention group, and HIV/sexual risk behaviors are presented by number of completed surveys for each participant. Multiple logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between completion of all 3 surveys (complete study retention, including baseline and 2 follow-up surveys) with age, education, race, intervention group, recruitment method (online vs. offline), amount of time online, and HIV status entered as multiple predictors.

RESULTS

Participants were MSM who were primarily Latino and African American (59.8% Latino, 27.7% African American, 12.5% Other). Over 93% of participants completed the 12-week post-intervention survey, 94% completed 2 out of the 3 surveys, and over 82% completed all 3 surveys, (including the baseline and both follow-up surveys). Approximately 70% of participants from each racial/ethnic group completed all 3 surveys, with African Americans and Latinos completing a larger proportion compared to “Other” participants. Greater than 90% of participants who had a bachelor’s or graduate level degree completed all 3 surveys while over 70% of those with less than a bachelor’s degree completed all 3 surveys. Responses to each survey appeared fairly similarly across group and method of recruitment (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study retention in an online social networking study among (primarily minority) men who have sex with men (MSM), Los Angeles, CA 2011–12

| Completed Baseline survey N=112* |

Completed 2 out of 3 surveys N=106 (94.6%)++ |

Completed all 3 surveys over 15-month period N=92 (82.1%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD)) |

32.1 (1.0) | 32.3 (1.0) | 32.5 (1.1) | |

| Race | ||||

| African American |

31 (100%) | 28 (90.3%) | 26 (83.9%) | |

| Latino | 67 (100%) | 64 (95.5%) | 56 (83.6%) | |

| Other | 14 (100%) | 14 (100%) | 10 (71.4%) | |

| Education | ||||

| GED/High school or less |

44 (100%) | 41 (93.2%) | 35 (79.5%) | |

| Associate's degree |

25 (100%) | 24 (96%) | 18 (72.0%) | |

| Bachelor's degree |

30 (100%) | 28 (93.3%) | 27 (90.0%0 | |

| Graduate school |

13 (100%) | 13 (100%) | 12 (92.3%) | |

| Group | ||||

| Intervention | 57 (100%) | 53 (93.0%) | 45 (79%) | |

| Control | 55 (100%) | 53 (96.4%) | 47 (85.5%) | |

| Recruitment method+ |

||||

| Online | 86 (100% | 77 (89.5%) | ||

| Offline | 18 (100%0 | 14 (77.8%) | ||

| Amount of time online each week |

||||

| None | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (100%) | |

| 0–1 hours | 9 (100%) | 6 (66.7%) | 5 (55.6%) | |

| 1–2 hours | 11 (100%) | 11 (100%) | 6 (54.6%) | |

| 3–4 hours | 14 (100%) | 14 (100) | 12 (85.7%) | |

| 4–5 hours | 12 (100%) | 12 (100%) | 12 (100%) | |

| 5+ hours | 64 (100%) | 61 (95.3%) | 55 (85.9%) |

Includes all participants who were eligible for the study and assigned to a social network group based on inclusion criteria

Referral method was first asked during the second survey. Participants were able to skip this item if they did not remember, explaining the reduced participant response rates for this item.

Although the majority of participants in this column completed the first follow-up, this includes participants who completed either the first or second follow-up.

Table 2 presents the results from the multiple logistic regression. Participants who spent a greater frequency of time online had almost twice the odds of completing all surveys. Participants who were HIV negative, compared to those who were HIV positive, had over 25 times the odds of completing all surveys.

Table 2.

Predictors of completing all 3 surveys over 15-month study period, Los Angeles, CA 2011–2012

| Odds Ratio* |

Standard Error |

Confidence Interval |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean (SD)) Race (Latino) |

1.01 | 0.05 | (.92, 1.11) | 0.79 | |

| African American |

3.34 | 4.25 | (.28, 40.43) | 0.34 | |

| Other | 0.09 | 0.18 | (.00, 5.42) | 0.25 | |

| Education | 1.52 | 0.5 | (.79, 2.90) | 0.21 | |

| Group (Control) | |||||

| Intervention | 2.28 | 1.96 | (.42, 12.33) | 0.34 | |

| Recruitment method (online) | |||||

| Offline | 1.42 | 1.55 | (.17, 12.07) | 0.75 | |

| Amount of time online | 1.84 | 0.52 | (1.06, 3.19) | 0.03 | |

| HIV Status (Negative) | 25.07 | 28.2 | (2.76, 277.30) | 0.004 | |

| Positive |

DISCUSSION

Results suggest that social networking technologies can be used to obtain high study retention rates among minority populations. Participants who spent a greater amount of time online and were HIV negative were more likely to have higher retention, suggesting that convenience and health status affect participation in health-related studies.

The high rates of retention in this study (for a review of comparative retention rates in online studies, see [2]) suggest that social networking technologies may help to improve study retention. Participants, especially among minority populations, are already using social networking technologies [15, 16]. Integrating these tools for retention makes study retention easier for participants because they can communicate with study personnel using an efficient communication tool they already use in their daily lives. This claim is supported by the increased retention among participants who were more frequently online, as it is easier for participants to complete an online study if they are already online. To increase retention, it is important for researchers to understand study populations and provide tools that are suited for their needs.

Social networking platforms may be combined with traditional retention methods (such as email and phone reminders) [2] to provide added communication tools for study retention. In addition to email or telephone reminders, linking to a participant’s online social network provides the researcher with a number of helpful contact methods, such as through the social networking email, chat, fan pages, and group/forum discussion walls. Use of Facebook Connect can also be useful to improve data quality by filtering out participants who might typically complete multiple surveys and be less likely to complete follow-up surveys [8]. Finally, participants may be more committed to responding to survey and study requests if they are contacted through social networking technologies because much of this activity might be publicly viewable and susceptible to social influence and perceived norms [17]. For example, in contrast to a phone call or email where the sender has no information about the status of the participant, the sender of a social networking communication can often see whether the receiver has viewed the contact attempt, or whether the receiver has recently been active on the site. Because of this ability to view activity (if participants choose to allow activity to be viewed in their privacy settings), participants might feel a greater responsibility to respond to requests for study information in a timely manner. However, to ensure participant safety and security, number of attempts to contact participants should be limited and participants should be reminded of their ability to adjust privacy and security settings.

This study is limited by the number of items we measured related to retention. In addition, we were unable to separate retention resulting entirely from social networking technologies versus other methods such as telephone and email. Recently, Facebook has implemented a feature that allows tracking of contact attempts. These data will be helpful in assessing methods for participant contact. Finally, the high overall rates of retention in this study make it difficult to detect group differences in retention. However, we hope that these methods can be replicated in future studies to achieve high retention rates across groups. A future randomized controlled trial using these methods compared to a standard retention control group may help to provide further insights.

This brief report suggests that social networking technologies can be integrated as tools for increasing retention in research. As participants discover innovative ways to communicate with each other, researchers may find value in using those technologies as methods for study engagement and retention.

Figure 1.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National Institutes for Mental Health (NIMH): (Young, K01 MH090884). Additional support was provided by UCLA CHIPTS and the UCLA AIDS Institute.

We wish to thank Thomas Coates, Sheana Bull, Harkiran Gill, Navkiran Gill, Pantipa Tachawachira, and Justin Thomas for assistance with this study and/or feedback on previous versions of the manuscript.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Fenner Y, Garland SM, Moore EE, et al. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pequegnat W, Rosser BRS, Bowen AM, et al. Conducting Internet-Based HIV/STD Prevention Survey Research: Considerations in Design and Evaluation. Aids and Behavior. 2007;11(4):505–521. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM, Luisi N, et al. Bias in online recruitment and retention of racial and ethnic minority men who have sex with men. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(2):e38. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glasgow RE, Nelson CC, Kearney KA, et al. Reach, engagement, and retention in an Internet-based weight loss program in a multi-site randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(2):e11. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.2.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bull SS, Lloyd L, Rietmeijer C, McFarlane M. Recruitment and retention of an online sample for an HIV prevention intervention targeting men who have sex with men: the Smart Sex Quest Project. AIDS Care. 2004;16(8):931–943. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331292507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horvath KJ, Nygaard K, Danilenko GP, Goknur S, Oakes JM, Rosser BR. Strategies to retain participants in a long-term HIV prevention randomized controlled trial: lessons from the MINTS-II study. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):469–479. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9957-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khosropour CM, Sullivan PS. Predictors of retention in an online follow-up study of men who have sex with men. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e47. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young S. Recommended Guidelines on Using Social Networking Technologies for HIV Prevention Research. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(7):1743–1745. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0251-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd D, Ellison N. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007;13(1):210–230. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith A, editor. Race and Ethnicity: Social Networking. California Immunization Coalition; 2011. Who's on what: Social media trends among communities of color. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young S, Szekeres G, Coates T. Sexual risk and HIV prevention behaviors among African American and Latino MSM social networking users. International Journal of STD and AIDS. doi: 10.1177/0956462413478875. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaganath D, Gill HK, Cohen AC, Young SD. Harnessing Online Peer Education (HOPE): integrating C-POL and social media to train peer leaders in HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2011;24(5):593–600. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.630355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young SD, Harrell L, Jaganath D, Cohen AC, Shoptaw S. Feasibility of recruiting peer educators for an online social networking-based health intervention. Health Education Journal. 2013;72(3):276–282. doi: 10.1177/0017896912440768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young S, Cumberland W, Sung-Jae L, Jaganath D, Szekeres G, Coates T. Social networking technologies as emerging tools for HIV prevention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-5-201309030-00005. In-press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bull SS, Breslin LT, Wright EE, Black SR, Levine D, Santelli JS. Case study: An ethics case study of HIV prevention research on Facebook: the Just/Us study. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(10):1082–1092. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsq126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young S, Jaganath D. Online Social Networking for HIV Education and Prevention: A Mixed Methods Analysis. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318278bd12. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cialdini RB. Influence: HarperCollins. 2009 [Google Scholar]