Abstract

Ethnoracial minority status contributes to an increased risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after trauma exposure, beyond other risk factors. A population-based sampling frame was used to examine the associations between ethnoracial groups and early PTSD symptoms while adjusting for relevant clinical and demographic characteristics. Acutely injured trauma center inpatients (N = 623) were screened with the PTSD Checklist. American Indian and African American patients reported the highest levels of posttraumatic stress and preinjury cumulative trauma burden. African American heritage was independently associated with an increased risk of higher acute PTSD symptom levels. Disparities in trauma history, PTSD symptoms, and event related factors emphasize the need for acute care services to incorporate culturally competent approaches for treating these diverse populations.

Prior investigations have found an increased risk for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in ethnoracial minority populations (Beals et al., 2002; Breslau et al., 1998; Kulka et al., 1990; Norris & Alegria, 2005; Pole, Gone, & Kulkarni, 2008; Santos et al., 2008; Zatzick et al., 2007) that has been associated with previous trauma exposure, trauma severity, lack of access and engagement in mental health treatment, medical comorbidities, and other factors (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000; Kulka et al., 1990). Factors associated with ethnoracial minority status across various ethnoracial populations have been explored to shed light on the differential rates of PTSD. African Americans had higher chronicity of depressive disorders, twice the likelihood of violence exposure, and higher rates of assault compared to Whites (Breslau et al., 1998; U. S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2003; Williams et al., 2007). Misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of mental health disorders have also been a common problem among African American populations (Alim, Charney, & Mellman, 2006; Davis, Ressler, Schwartz, Stephens, & Bradley, 2008). American Indians had higher trauma exposure compared to national samples, including experiencing and witnessing more violence and accidents (Manson, Beals, Klein, & Croy, 2005; National Institute of Mental Health, 2001; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999). Although these studies may not represent all American Indian nations, findings particular to American Indian populations have differed from trends found in larger population studies (i.e., being married was a risk factor rather than a protective factor for PTSD, gender differences were not found; Manson et al., 2005). Latinos had the highest PTSD rates compared to their White and African American counterparts and acculturation levels predicted peritraumatic dissociation (Marshall & Orlando, 2002; Marshall & Schell, 2002; Pole et al., 2008). Among Asian Americans, nonproficient English speakers had higher rates of mental health disorders compared to English speakers (Takeuchi et al., 2007). However, heterogeneity within ethnoracial groups makes it difficult to interpret increased risk findings among broadly defined ethnoracial groups, given that urban/rural, immigrant/native/refugee, acculturation, and socioeconomic status often vary greatly within groups (Pole et al., 2008).

Ethnoracially diverse patients comprise a substantial percentage of survivors who are injured and admitted to the hospital in the United States (Marshall & Orlando, 2002; Santos et al., 2008; Zatzick et al., 2007). Trauma exposure when coupled with physical injury confers an increased risk for the development of PTSD. According to the Center for Disease Control's (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics in 2004, 29.5 million emergency department visits occurred with a primary injury diagnosis and 1.9 million resulting in inpatient admissions (CDC, 2009). Greater levels of early posttraumatic emotional distress, including PTSD symptoms, have been consistently identified as risk factors for the subsequent development of PTSD after injury (Bryant, Harvey, Guthrie, & Moulds, 2000; Marshall & Schell, 2002; O'Donnell, Creamer, & Pattison, 2004; Shalev, Bonne, & Eth, 1996; Shalev, Peri, Canetti, & Schreiber, 1996; Winston, Kassam-Adams, Garcia-Espana, Ittenbach, & Cnaan, 2003; Zatzick et al., 2002, 2007).

Few investigations have compared variations in acute PTSD symptoms in large, representative samples of ethnoracially diverse trauma survivors. Zatzick and colleagues (2007) found that nationally, across 69 hospitals, African American, American Indian, and Latino injury survivors were at greater risk for developing symptoms consistent with PTSD when compared to Whites. This investigation, however, did not include a measure of acute posttraumatic distress. In a follow-up study, Santos and colleagues (2008) found that relative to White patients, African American, American Indian, Asian, and Latino patients reported elevations in one or more posttraumatic symptom clusters. This investigation was limited by relatively small sample sizes and a limited assessment of relevant clinical and demographic characteristics across groups.

In view of the need to more precisely identify risk factors, to separate out the possible confounding factors from ethnoracial group, and to simultaneously examine different ethnoracial groups, the current investigation used clinical epidemiological methods to explore ethnoracial variations in early PTSD symptom levels in a sample of 623 ethnoracially diverse injury survivors admitted to a single county hospital-based level I trauma center. The large sample allowed assessment of variations in preinjury trauma, substance use symptoms, and other clinical and demographic characteristics that have been shown in prior studies to increase the risk for PTSD. The investigation hypothesized that African American, American Indian, Asian, and Latino injury survivors would report higher levels of acute PTSD symptoms when compared to Whites. Regression analyses were used to assess for independent associations between ethnoracial minority status and acute PTSD symptoms while adjusting for relevant injury, clinical, and demographic characteristics, including preinjury trauma history.

METHOD

Participants

Eligible patients were English-speaking survivors of unintentional (accidental) or intentional (violence-related) injury, aged 18 or older, who lived within 50–100 miles of the trauma center. Nine thousand four-hundred nine injured patients were admitted to the Harborview Trauma Center during the period of data collection. Of these, 8,454 were never approached for consent. Reasons for patients not being approached for consent included being discharged prior to approach (2,798), living at distances greater than 50–100 miles from the trauma center (2,737), severe cognitive impairment (328), readmission (378), incarceration (101), self-inflicted injury (177), deceased/other (1,427), and monolingual non-English speaking status. Excluded monolingual non-English speaking patients (508) were comprised of approximately 40% monolingual Asian language speaking patients (202, from highest to lowest incidence—Vietnamese, Cantonese, Korean, Mandarin, Cambodian, Punjabi, Tagalog, Taiwanese, Laotian, Mien, Hindi, Marshallese, Other Chinese, Japanese, Khmer, Mongolian, Samoan, Tong, Indonesian, Toi San, Nepali, Tamil, and Burmese), 25% monolingual Spanish speaking patients (140), and 33% monolingual other language speaking patients (166, from highest to lowest incidence—Somali, Russian, Aramaic, Ukrainian, Other/Unknown, Polish, Tigrinya, Arabic, Bosnian, Romanian, Bulgarian, Dutch, Portuguese, Albanian, Ethiopian, Farsi, Swahili, Dinka, French, Oromo, Finish, and Honduran). Nine hundred fifty-five patients were approached for consent and 332 (35%) refused protocol participation. The remaining 623 patients were screened for PTSD symptoms with the PTSD Checklist.

The patients completing the interview did not significantly differ from all patients admitted to the trauma center on gender or previous medical comorbidities according to chi-square and t-test comparisons. However, on average, interviewed participants were significantly younger (M = 37.2, SD = 13.5 years vs. M = 45.4, SD = 19.9) and had lower Injury Severity Scores (M = 13.5, SD = 8.9 vs. M = 16.4, SD = 12.6) when compared to all other patients admitted to the trauma center (ps < .001).

Of the 623 patients included in the current investigation 28% were female and 77% were insured. Thirty-two percent reported annual household incomes of <$25,000, 16% with $25,000 to $50,000, and 52% with >$50,000. Participants reported a mean of 13.4 years of education (SD = 2.5) and a mean of 4.9 (SD = 2.8) previous traumatic experiences. Self-described ethnoracial breakdowns were as follows: White (61.8%), African American (15.2%), American Indian (13.0%), Asian (5.6%), and Latino (4.3%).

Measures

Posttraumatic stress symptoms

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were measured with the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL; Weathers, Huska, & Keane, 1991). The PCL is a 17-item self-report Likert response (1–5) questionnaire that assessed the intrusive, avoidant, and arousal PTSD symptom clusters. All PCL symptom assessments were anchored to the injury event that brought the patient to the hospital and demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .92). The PCL had good reliability and validity across trauma-exposed populations (Blanchard, Jones-Alexander, Buckley, & Forneris, 1996; Hoge et al., 2004) and has been used extensively to assess PTSD among diverse samples in the acute care setting (Marshall & Schell, 2002; Zatzick et al., 2002). In a study of motor vehicle crash survivors, Blanchard and colleagues (1996) reported the PCL has a correlation of .93 with continuous scores on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale and indicated significant clinical distress for scores ≥44 (Blake et al., 1990).

Ethnoracial group classification

To determine ethnoracial group classifications, patients were asked to report their categorical ethnic/racial group identification (i.e., African American, American Indian, Asian/Pacific Islander, Latino, White, Other). Patients were also asked the open-ended question, “How do you describe your ethnicity?” Research associates were then instructed to explore with patients in an open-ended fashion their ethnoracial, cultural identity. Patients who were clearly identified with a single ethnic/racial group across these indices were assigned to one category. For individuals who self-identified more than one group, decision rules were derived from the 2000 U.S. Census categorization criteria (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000) allowing the classification of multi-ethnoracially identified individuals into singular categories (i.e., “African American alone or in combination”). Furthermore, consistent with recommendations for conducting ethnic and racial disparity research, mixed-heritage individuals were classified into the four non-White ethnic groups based on their ethnic minority status inferring similar patterns of exploitation, prejudice, and discrimination as these patterns may relate to the experience of posttraumatic stress (Sue & Dhindsa, 2006). Ninetyeight of the 623 patients included in the study (15.7%) were of mixed heritages and were classified as follows: 59 American Indian, 19 African American, 7 Latino, and 13 Asian. Two thirds (65) of the mixed-heritage patients identified with one ethnic minority group mixed with only White (34 American Indian, 12 African American, 6 Latino, 13 Asian). The remaining 33 patients (27 designated two ethnic minority groups, 6 designated three or more ethnic minority groups) were classified into single ethnic groups as first American Indian, then African American, then Latino, and finally Asian. Although no classification scheme for these multiple heritage-based ethnicities was ideal, including these individuals in the analyses offered better population representation and this hierarchy-based method of classification mirrors the suggested hierarchy of rates of posttraumatic stress across these groups (Pole et al., 2008). This method resulted in the minority ethnic groups overlapping in the following way: American Indian group—25 (31%) overlapped with African American (16), Latino (12), Asian (3); African American group—7 (7%) overlapped with Latino (2), Asian (5); Latino group—1 (4%) overlapped with Asian; and Asian group—none (0%) overlapped.

Posttraumatic stress predictors

Participants were asked during the interview to designate their years of education and household income on a scale ranging from 1 to 14 beginning at $0–4,999 with 1 to 6 in $5K increments and 7 to 14 in $10K increments, ending in over $100,000. Participants' age, gender, and insurance status were obtained through the trauma center's trauma registry.

To assess for traumatic life events prior to the index injury, we used a modified version of the traumatic event inventory (Kessler et al., 2004) developed for the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. The measure screened for the occurrence of traumatic life events such as physical and sexual assault, natural disasters, and combat. The measure also assessed whether PTSD ever developed in response to any of the incident traumas.

The Injury Severity Score and comorbid chronic medical conditions were obtained from the trauma center's trauma registry and derived from the International Classification of Disease, Ninth Version, Clinical Modification codes (Civil & Schwab, 1985; Johns Hopkins Health Services Research and Development Center, 1989; MacKenzie, Morris, & Edelstein, 1989). The interview included questions that addressed the injury type (coded categorically as intentional vs. unintentional) and endorsement of past symptoms of PTSD enduring for at least 30 days to determine the probability of preexisting PTSD before the current injury. Probable preexisting PTSD was dichotomized as “yes” if patients endorsed PTSD symptoms from past traumas that lasted at least 30 days.

Alcohol use was assessed during the last 12 months before the current injury using the 3-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C; Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Zhou, 2005). Patients were asked about the frequency of other drug use with a single-item screen that assessed substance use over the past year. Blood alcohol concentration, amphetamine, cocaine, marijuana, opiate, and other drug intoxication at the time of admission to the hospital was assessed with toxicology screen data derived from the trauma registry.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from May 16, 2006 to August 22, 2008 at the University of Washington's Harborview Medical Center, a county hospital-based level I trauma center in King County, Washington. Study participants were interviewed at baseline in the surgical ward as part of an initial screening assessment for a clinical trial of a preventative stepped care intervention targeting PTSD and were paid either $10 or $15 depending on how long the interview lasted. The University of Washington Institutional Review Board approved all investigative procedures prior to the initiation of the study and written informed consent was obtained from each study participant. Each weekday morning during the study recruitment period, a research associate used an automated list of newly admitted injury survivors from the admissions/trauma registry database to approach each potential participant in the surgical ward in the order dictated by random number assignments. The principal investigator and senior study coinvestigators oversaw the training for the recruitment and interview procedure. On average, patients were interviewed 5.6 (SD = 8.9, range = 0–119) days after the date of injury.

Data Analysis

All analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0. We first compared the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients included in the investigation with all other patients admitted during the time period of the study to assess the representativeness of the patient sample derived from the random approach procedure. Next, we compared acute PTSD symptoms, trauma history, and other clinical and demographic characteristics across patients from African American, American Indian, Asian, Latino, and White groups evaluating main effects of ethnoracial group (analyses of variance; ANOVAs) followed by Fisher's least significance difference tests to evaluate mean differences. Finally, regression analyses were used to assess for an independent association between ethnoracial heritage and acute PTSD symptoms while adjusting for other injury, clinical, and demographic characteristics. Three stages of sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine inclusion of mixed ethnoracial heritage patients. Analyses were performed excluding them from the sample, then classifying them as their own mixed group, and finally, including them within the singular ethnic groups. All analyses showed identical trends in the main effects and regression analyses. Therefore, mixed individuals were classified into one of the five ethnoracial groups based on previously described criteria (Santos et al., 2008; U.S. Census Bureau, 2000).

RESULTS

Ethnoracial Differences Across Predictors of Posttraumatic Stress

As shown in Table 1, African American and American Indian patients had less education than Whites (ps < .001) and African American patients had the highest proportion of uninsured status, significantly higher than all other groups (ps < .05). Asian patients reported the highest household income, significantly higher than White, African American, and American Indian patients (ps < .05). White patients were significantly older than all other groups (ps < .05).

Table 1.

Main Effects (ANOVA) of Ethnoracial Group and Post Hoc Comparisonsa for Posttraumatic Stress and Predictors

| Non-Hispanic White (n = 385) |

African American (n = 95) |

American Indian (n = 81) |

Latino (n = 27) |

Asian (n = 35) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Posttraumatic stress (PCL-C)*** | 31.9 | 14.3 | 40.4 | 16.3b | 37.8 | 16.6b | 31.1 | 15.0 | 32.5 | 14.1 |

| Sociodemographic and insurance predictors | ||||||||||

| Household income* | 9.2 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 6.0 | 8.2 | 5.5 | 9.0 | 4.3 | 11.6 | 4.3b |

| Education (years)*** | 13.7 | 2.6 | 12.8 | 1.9b | 12.6 | 2.3b | 13.1 | 2.0 | 13.6 | 2.6 |

| Age (years)*** | 39.7 | 14.2 | 34.3 | 12.7b | 34.7 | 11.5b | 33.9 | 10.4b | 31.0 | 12.4b |

| Gender: % female | 29 | 27 | 28 | 11 | 26 | |||||

| Insured? % yes*** | 80 | 58b | 79 | 85 | 78 | |||||

| Pretrauma and index trauma factors | ||||||||||

| Injury severity | 13.9 | 9.2 | 12.6 | 8.6 | 12.0 | 7.1 | 14.7 | 10.4 | 12.8 | 8.3 |

| Admission event type (% intentional)*** | 12 | 60b | 27b | 26 | 23 | |||||

| Total # of past traumas*** | 4.7 | 2.7 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 6.4 | 2.9b | 4.9 | 2.7 | 4.1 | 2.9 |

| Probable prior PTSD? % yes* | 39 | 32 | 44 | 22 | 18b | |||||

| Total # preexisting medical problems | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.8 |

| Substance use (% positive) | ||||||||||

| Alcohol: BAC*** | 29 | 51b | 47b | 61b | 31 | |||||

| Alcohol: AUDIT-C | 53 | 55 | 59 | 63 | 56 | |||||

| Tobacco** | 50 | 61b | 72b | 63 | 72b | |||||

| Marijuana** | 37 | 52b | 52b | 19 | 53 | |||||

| Cocaine*** | 18 | 38b | 28b | 26 | 16 | |||||

| Amphetamines (p = .080) | 7 | 4 | 15 | 4 | 9 | |||||

| Opiates | 8 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 12 | |||||

| Other drugs | 16 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 22 | |||||

Note. All means displayed as percentages represent categorical variables. PCL-C = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder. BAC = blood alcohol concentration. AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Fisher's Least Significant Difference.

Indicate means significantly different from White patients.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

African American and American Indian patients had greater levels of previously established risk factors for PTSD, including higher reports of intentional versus unintentional current injury and past cumulative burden of trauma (Table 1). Specifically, African American patients had the highest percentage of intentional (violence-) related injury, significantly higher than all groups (ps < .001), while White patients had the lowest percentage of intentional injury. American Indian patients also reported a significantly higher percentage of intentional, violence-related injury compared to White patients (p < .001) and reported a significantly higher number of past traumas compared to all other groups (ps < .05). Overall, patients admitted for intentional (violence-) related injury reported a significantly higher number of past traumas compared to those admitted for unintentional injury (p < .05). Asian patients reported the lowest percentage of probable preexisting PTSD, significantly lower than White and American Indian patients (ps < .05); and American Indian patients reported the highest percentage of probable preexisting PTSD, significantly higher than Asian and Latino patients (ps < .05).

Higher percentages of substance use were found among ethnoracially diverse groups compared to White patients (Table 1). African American and American Indian patients had significantly higher proportions of blood alcohol concentration, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine use compared to Whites (ps < .05). Latino patients had significantly higher proportions of positive alcohol toxicology results compared to White and Asian patients (ps < .05) and significantly lower proportions of marijuana use compared to African American, American Indian, and Asian patients (ps < .01). Asian patients had a significantly higher proportion of tobacco use compared to White patients (p < .05), a significantly lower proportion of positive alcohol toxicology results, and a significantly higher proportion of marijuana use compared to Latino patients (ps < .05), and a significantly lower proportion of cocaine use compared to African American patients (p < .01).

Hypothesis Testing

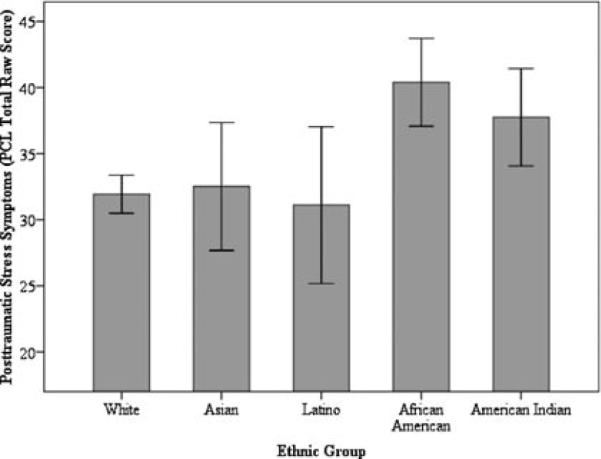

As predicted, a main effect of ethnoracial group was found, F (4, 618) = 7.77, p < .001, indicating the highest posttraumatic stress symptoms among American Indian and African American patients (see Figure 1 and Table 1). Effect sizes were computed using Cohen's d statistic, using raw means and standard deviations (Cohen, 1977, 1988) to evaluate significant mean differences between ethnoracial groups, and resulted in medium effect sizes for African American patients and small effect sizes for American Indian patients. Specifically, African American patients were more likely to endorse acute PTSD symptoms than White (d .55), Asian (d = 0.52), and Latino (d (d = .55), Asian (d = 0.52), and Latino (d = 0.59) patients (ps < .01). American Indian patients endorsed significantly higher PTSD symptoms compared to White (d 0.38) and Latino (d .42) patients (ps < .05).

Figure 1.

Posttraumatic stress symptoms (PCL total raw scores) across ethnoracial groups, means and 95% confidence intervals. Note: African American patients reported significantly elevated posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms compared to White and Latino patients (ps ≤ .008); American Indian patients reported significantly elevated PTSD symptoms compared to White, Latino, and Asian patients (ps ≤ .047). PCL Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist.

A multiple linear regression in which factors were entered in hierarchical blocks was run to test whether or not ethnoracial differences in acute PTSD symptoms would hold after adjusting for the various potential confounders. Variance inflation factor was computed to rule out collinearity between the predictor variables. Although PCL raw scores were positively skewed, negative binomial regressions were calculated, which resulted in a similar pattern of findings to the multiple linear regression. Outliers were examined. Ethnoracial groups were entered first and accounted for adjusted R2 = .04 of the variation in posttraumatic stress symptoms, F (4, 389) = 4.11, p < .01.

Sociodemographic and insurance predictors were then entered and accounted for an additional adjusted R2Δ = .04, F (9, 384) = 3.89, p < .001. The final step included entering pretrauma and index trauma factors as well as substance use, and resulted in the largest change, adjusted R2Δ = .24, F (22, 371) = 8.17, p<.001. As expected, several of the predictor variables (see Table 2) significantly predicted posttraumatic stress symptoms. Female gender, higher injury severity, higher cumulative burden of past traumas, intentional (violence) injury type, probability of preexisting PTSD, and amphetamine use were all associated with higher reports of posttraumatic stress. Although accounting for these confounders, African American ethnoracially identified patients continued to have significantly higher risk for acute PTSD symptoms (β .12, p < .05).

Table 2.

Multiple Linear Regression in Which Factors Were Entered in Hierarchical Blocks Predicting Posttraumatic Stress (PCL Raw Total Scores): Standardized Regression Coefficients (βs)

| Predictor variable | Block 1 R2 = .041** | Block 2 R2 = .083*** RΔ2 = .043** | Block 3 R2 = .326*** RΔ2 = .243*** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block 1: Ethnoracial group | |||

| African American | .17** | .17** | .12* |

| American Indian | .10† | .09† | .03 |

| Latino | −.06 | −.05 | −.04 |

| Asian | .03 | .04 | .04 |

| Block 2: Sociodemographic and insurance predictors | |||

| Household income | −.07 | −.02 | |

| Education (years) | −.10 | −.01 | |

| Age (years) | .03 | −.06 | |

| Gender: % female | .18*** | .13** | |

| Insured? % yes | .01 | .03 | |

| Block 3 | |||

| Pretrauma and index trauma factors | |||

| Injury severity | .14** | ||

| Admission event type (% intentional) | .18*** | ||

| Total # of past traumas | .20*** | ||

| Probable prior PTSD? % yes | .24*** | ||

| Total # preexisting medical problems | .05 | ||

| Substance use (% positive) | |||

| Alcohol: BAC | .00 | ||

| Alcohol: AUDIT-C | −.06 | ||

| Tobacco | .04 | ||

| Marijuana | −.02 | ||

| Cocaine | .08 | ||

| Amphetamines | .11* | ||

| Opiates | −.04 | ||

| Other drugs | .01 |

Note. PCL-C = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-Civilian Version; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; BAC = blood alcohol concentration; AUDIT-C = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

DISCUSSION

This investigation explored ethnoracial variations in acute PTSD symptoms and related clinical and injury characteristics in a large sample of injury survivors admitted to a single U.S. trauma center. As predicted, both African American and American Indian injured trauma survivors reported higher levels of acute PTSD symptom compared to Whites.

African American injured trauma survivors showed the highest levels of acute PTSD symptoms and continued to have higher risk even after accounting for various factors. They reported the highest incidence of intentional (violence-) related injury in this sample. Prior investigation has demonstrated that individuals with experiences of intentional injury are more likely to have four or more past traumas (Ramstad, Russo, & Zatzick, 2004). Patients in this sample admitted with a violence-related injury had significantly higher incidences of past trauma, indicating a dense trauma- and violence-laden environment, which may indicate increased risk for posttraumatic stress. Childhood trauma may also explain the elevated posttraumatic stress, given its association with greater risk for PTSD; however, childhood trauma was not discernible within the reported past traumatic experiences due to the structure of the questions, and unfortunately could not be evaluated directly. Experiences of discrimination are another possible explanation, given perceived discrimination has been found to account for mental health differences between African Americans and Whites, above and beyond socioeconomic status (Schulz et al., 2006; Williams, Yu, Jackson, & Anderson, 1997). Future studies should evaluate the roles of discrimination, family, and social support in the context of trauma.

After accounting for various PTSD-related predictors, significant acute PTSD symptom elevations did not persist with American Indian trauma survivors. However, they reported the highest cumulative burden of past trauma, which is consistent with literature that has compared this group to national samples (Manson et al., 2005; U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1999). This high burden of past trauma and immediate report of PTSD symptoms postinjury indicate the need for appropriate identification of these survivors and available services within the acute care trauma system. It should be noted that this group was comprised primarily of ethnoracially mixed patients and therefore may not generalize to all tribal citizens. The classification strategy used for the ethnoracially mixed patients favored American Indian classification due to findings of higher perceived discrimination in health care, notably mixed White and American Indian individuals perceived the highest discrimination in a population-based sample compared to American Indian, African American, and White individuals (Johansson, Jacobsen, & Buchwald, 2006), and findings of higher trauma burden compared to other ethnic groups (Pole, et al., 2008). However, this knowledge base is quite limited.

Contrary to existing findings of elevated PTSD symptoms among Latino and Asian populations (Pole, Best, Metzler, & Marmar, 2005; Pole et al., 2008; Takeuchi et al., 2007; A. E. Williams et al., 2008), this study did not find significant PTSD symptom elevations compared to Whites. This null finding should be viewed with caution, given the small groups sizes and may be due to the fact that non-English speaking patients were excluded from the study resulting in a relatively small and potentially highly acculturated cohort of Latino and Asian patients. This is consistent with findings of higher levels of peritraumatic dissociation among less acculturated Latino injury survivors (Marshall & Schell, 2002) and higher service utilization with more acculturation and lower incidence of mental disorders among English speaking Asian Americans (Abe-Kim et al., 2007; Takeuchi et al., 2007).

Ethnoracial minority injury survivors tended to have more positive alcohol and drug toxicology screens upon admission to the hospital compared to Whites, indicating more high risk behavior in association with acute injury. Substance use has been associated with increased risk for future trauma and rehospitalization (Rivara, Koepsell, Jurkovich, Gurney, & Soderberg, 1993) and may indicate maladaptive coping strategies that contribute to putting ethnoracial minorities at risk for further injury and trauma. Substance intervention services, particularly among ethnoracial minority groups, are needed in the acute care setting.

These findings indicate a need for acute care clinical services that can effectively identify and engage ethnoracial minority patients in appropriate mental health care, addressing both comorbid substance issues and posttraumatic stress symptoms. Future studies should include measurements of acculturation and other relevant cultural factors that may play an important mediating role in PTSD symptoms directly after injury. Patients from diverse backgrounds may describe postinjury stress differently, may prefer alternative forms of treatment, and may require more intensive explanations of the goals of interventions related to mental health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2001). Rates of mental health service utilization were below national rates for Asian Americans and nonproficient English speakers had higher rates of mental health disorders compared to English speakers (Abe-Kim et al., 2007; Takeuchi et al., 2007). Language barriers, perceived helplessness, and cultural factors such as loss of face may be barriers to service. Therefore, services should cater to individuals from different ethnoracial groups and maximize culturally competent strategies to increase engagement in mental health treatment.

The marked diversity encountered in acute care medical settings such as the one we studied requires an innovative combination of treatment approaches to have potential for high population impact. Ethnic disparities in trauma care have been associated with worse long-term functional outcomes, particularly related to reintegration into society, a decline in overall functioning, and a lower likelihood to be placed in acute rehabilitation, despite insurance status compared to White trauma survivors (M. Shafii & Gentilello, 2008; Shafii, Stovel, & Holmes, 2007). County hospital-based clinical services integrating bilingual, bicultural care managers and addressing the spectrum of postinjury linguistic, medical, and mental health needs have been developed (Jackson, Zatzick, Harris, & Gardiner, 2008) and randomized effectiveness trials of stepped care interventions that include care management and evidence-based treatments for PTSD and related comorbidities have shown promise (Zatzick et al., 2004). More research is needed on such collaborative care programs tailored for heterogeneous ethnoracial minority patients. Future population-based investigations could develop methods for sampling ethnoracially diverse monolingual non-English speaking trauma survivors who may be among the most vulnerable injury survivors (Todd, Samaroo, & Hoffman, 1993).

Understanding ethnic differences in posttraumatic stress and related factors is essential to developing effective care for ethnic minority groups at risk for developing PTSD. Clarifying the roles of various predictive factors among ethnic groups can inform screening practices and treatment targets. Our findings further substantiate the vulnerability of ethnic minority populations to posttraumatic stress as well as the need to expand our investigations of contributing factors, using population-based samples, to better inform practices.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health Diversity Supplement Grant R01MH073613-04S1 to Dr. Stephens and R01MH073613 to Dr. Zatzick.

REFERENCES

- Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi DT, Hong S, Zane N, Sue S, Spencer MS, et al. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alim TN, Charney DS, Mellman TA. An overview of posttraumatic stress disorder in African Americans. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:801–813. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals J, Manson SM, Shore JH, Friedman M, Ashcraft M, Fairbank JA, et al. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among American Indian Vietnam veterans: Disparities and context. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15:89–97. doi: 10.1023/A:1014894506325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake D, Weathers F, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Klauminzer G, Charney D, et al. Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) National Center for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division; Boston: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreske P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant RA, Harvey AG, Guthrie RM, Moulds ML. A prospective study of psychophysiological arousal, acute stress disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:341–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control NCHS data on injuries. 2009 Retrieved August 20, 2009, from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/injury.pdf.

- Civil ID, Schwab CW. The Abbreviated Injury Scale: 1985 revision. American Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine, Committee on Injury Scaling; Morton Grove, IL: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analyses for the behavioral sciences-revised edition. Academic Press; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RG, Ressler KJ, Schwartz AC, Stephens KJ, Bradley RG. Treatment barriers for low-income, urban, African Americans with undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:218–222. doi: 10.1002/jts.20313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:844–854. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000164374.32229.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C, Zatzick D, Harris R, Gardiner L, editors. Loss in translation. Oxford University Press; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson P, Jacobsen C, Buchwald D. Perceived discrimination in health care among American Indians/Alaska Natives. Ethnicity and Disease. 2006;16:766–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins Health Services Research and Development Center . Deter-mining injury severity from hospital discharges: A program to map ICD-9CM diagnoses into AIS and ISS severity scores. The Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore, MD: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): Design and field procedures. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13(2):69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, et al. Trauma and the Vietnam War generation: Report of Findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Brunner/Mazel; New York: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie EJ, Morris JA, Edelstein SL. Effect of pre-existing disease on length of hospital stay in trauma patients. Journal of Trauma. 1989;29:757–764. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198906000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson SM, Beals J, Klein SA, Croy CD. Social epidemiology of trauma among 2 American Indian reservation populations. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:851–859. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Orlando M. Acculturation and peritraumatic dissociation in young adult Latino survivors of community violence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:166–174. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.1.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall GN, Schell TL. Reappraising the link between peritraumatic dissociation and PTSD symptom severity: Evidence from a longitudinal study of community violence survivors. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:626–636. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health . A workshop to reach consensus on best practices. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2002. Mental health and mass violence: Evidence-based early psychological intervention for victims/survivors of mass violence. NIH Publication No. 02-5138. [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Alegria M. Mental health care for ethnic minority individuals and communities in the aftermath of disasters and mass violence. CNS Spectrums. 2005;10:132–140. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900019477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell ML, Creamer M, Pattison P. Posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma: Understanding comorbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1390–1396. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole N, Best SR, Metzler T, Marmar CR. Why are Hispanics at greater risk for PTSD? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2005;11:144–161. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole N, Gone JP, Kulkarni M. Posttraumatic stress disorder among ethnoracial minorities in the United States. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2008;15:35–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ramstad SM, Russo J, Zatzick D. Is it an accident? Recurrent traumatic life events in level I trauma center patients compared to the general population. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2004;17:529–534. doi: 10.1007/s10960-004-5802-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara FP, Koepsell TD, Jurkovich GJ, Gurney JG, Soderberg R. The effects of alcohol abuse on readmission for trauma. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;270:1962–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos M, Russo J, Aisenberg G, Uehara E, Ghesquiere A, Zatzick D. Ethnic/racial diversity and posttraumatic distress in the acute care medical setting. Psychiatry. 2008;71:234–245. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.3.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz AJ, Gravlee CC, Williams DR, Israel BA, Mentz G, Rowe Z. Discrimination, symptoms of depression, and self-rated health among African American women in Detroit: Results from a longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:1265–1270. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.064543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafii M, Gentilello LM. Ethnic disparities in initial management of trauma patients in a nationwide sample of emergency department visits. Archives of Surgery. 2008;143:1057–1061. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafii T, Stovel K, Holmes K. Association between condom use at sexual debut and subsequent sexual trajectories: A longitudinal study using biomarkers. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:1090–1095. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.068437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev AY, Bonne O, Eth S. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: A review. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:165–182. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev AY, Peri T, Canetti L, Schreiber S. Predictors of PTSD in injured trauma survivors: A prospective study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:219–225. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S, Dhindsa MK. Ethnic and racial health disparities research. Health Education and Behavior. 2006;33:459–469. doi: 10.1177/1090198106287922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, Chae DH, Gong F, Gee GC, et al. Immigration-related factors of mental disorders among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:84–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd KH, Samaroo N, Hoffman JR. Ethnicity as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269:1537–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau . Population by race for the Unites States: 1990 to 2000. Author; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity-A supplement to Mental Health: A report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; Rockville, MD: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics . National Criminal Justice (NCJ publication 3386) Author; Washington, DC: 1999. American Indians and crime. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics . Criminal victimization, 2003 (NCJ publication 205455) Author; Washington, DC: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version. The National Center For PTSD, Boston VA Medical Center; Boston: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Williams AE, Smith WR, Starr AJ, Webster DC, Martinez RJ, Vojir CP, et al. Ethnic differences in posttraumatic stress disorder after musculoskeletal trauma. The Journal of Trauma. 2008;65:1054–1065. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318184a9ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Gonzales HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winston FK, Kassam-Adams N, Garcia-Espana F, Ittenbach R, Cnaan A. Screening for risk of persistent posttraumatic stress in injured children and their parents. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290:643–649. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick D, Kang SM, Muller HG, Russo JE, Rivara FP, Katon W, et al. Predicting posttraumatic distress in hospitalized trauma survivors with acute injuries. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:941–946. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick D, Rivara F, Nathens A, Jurkovich G, Wang J, Fan MY, et al. A nationwide US study of posttraumatic stress symptoms after hospitalization for physical injury. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:1469–1480. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Rivara F, Droesch R, Wagner A, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of stepped collaborative care for acutely injured trauma survivors. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:498–506. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]