Abstract

Eukaryotic cells store neutral lipids, such as triacylglycerol (TAG), in lipid droplets (LDs). Here, we have addressed how LDs are functionally linked to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). We show in S. cerevisiae that LD growth is sustained by LD-localized enzymes. When LDs grow in early stationary phase, the diacylglycerol acyl-transferase Dga1p moves from the ER to LDs and is responsible for all TAG synthesis from diacylglycerol (DAG). During LD breakdown in early exponential phase, an ER membrane protein, Ice2p, facilitates TAG utilization for membrane-lipid synthesis. Ice2p has a cytosolic domain with affinity for LDs and is required for the efficient utilization of LD-derived DAG in the ER. Ice2p breaks a futile cycle on LDs between TAG-degradation and -synthesis, promoting the rapid re-localization of Dga1p to the ER. Our results show that Ice2p functionally links LDs with the ER, and explain how cells switch neutral lipid metabolism from storage to consumption.

Introduction

Lipid droplets (LDs) exist in virtually all cells and play a major role in human metabolic diseases, such as atherosclerosis and type 2 diabetes (Greenberg et al., 2011; Walther and Farese, 2012). LDs consist of a core of neutral lipids, comprised of triacylglycerol (TAG) and sterol esters (SE), and a surrounding phospholipid monolayer (Fujimoto and Parton, 2011; Grillitsch et al., 2011; Leber et al., 1994; Penno et al., 2013). The size and number of LDs varies in response to changes in nutrient availability and metabolic state. LDs can expand by the esterification of diacylglycerol (DAG) with fatty acids (FAs)(Listenberger et al., 2003). Conversely, LDs can be consumed by the hydrolysis of TAGs. TAGs can be used in different ways. They can be completely hydrolyzed to generate FA and glycerol, which are ultimately used to generate ATP in the respiratory chain (Zechner et al., 2009). TAGs can also be partially hydrolyzed to generate DAG and FA, which are then used as precursors for membrane lipids (Fakas et al., 2011; Rajakumari et al., 2010; Zanghellini et al., 2008). In addition, the formation of TAG is important to avoid FA-induced lipotoxicity (Garbarino et al., 2009; Listenberger et al., 2003; Petschnigg et al., 2009).

The enzymes involved in the synthesis and degradation of neutral lipids have been identified, and some information exists on how LDs are formed. The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) appears to play a major role, as several enzymes involved in the synthesis of neutral lipids localize to the ER (Czabany et al., 2007; Natter et al., 2005). A popular model posits that LDs form by the accumulation of neutral lipids between the two leaflets of the phospholipid bilayer of the ER; the monolayer-surrounded lipid particle could either bud off into the cytoplasm or remain associated with the ER (Fujimoto and Parton, 2011; Walther and Farese, 2012). Under conditions of LD growth, some enzymes involved in the synthesis of TAG appear to be localized to LDs, suggesting that neutral lipids are not only generated in the ER (Jacquier et al., 2011; Kuerschner et al., 2008; Wilfling et al., 2013). How LDs are consumed is even less understood. One possibility is that LDs are completely autonomous: lipases sitting on LDs would hydrolyze TAGs into glycerol and FA, which in turn would be activated by acyl-CoA synthases for further metabolism. Alternatively, LD consumption may require a functional interaction between LDs and the ER. A coupling between the two organelles would not only allow the efficient conversion of DAG into membrane lipids, but also prevent the accumulation of toxic levels of TAG breakdown products. A physical interaction between the two organelles has been observed in many systems, suggesting that they might indeed be functionally linked (Murphy et al., 2009).

S. cerevisiae offers a unique possibility to study the formation and consumption of LDs. LDs increase in size and number as yeast cells reach early stationary phase, and they shrink when cells are diluted into fresh medium to resume growth (Kurat et al., 2006). During LD growth, DAG is generated in the ER from phosphatidic acid (PA) by the phosphatase Pah1p (Adeyo et al., 2011) (see scheme in Figure 1A). DAG can be converted to TAG by the two diacylglycerol-acyl transferases Lro1p and Dga1p (Oelkers et al., 2002). Lro1p is an ER membrane protein and catalyzes the transfer of a fatty acid molecule from a phospholipid to DAG (Choudhary et al., 2011; Oelkers et al., 2000). In contrast to Lro1p, Dga1p catalyzes the acyl-CoA dependent esterification of DAG. Dga1p has two trans-membrane segments, presumably forming a hairpin structure that allows localization of the enzyme to both the bilayer of the ER and the monolayer of LDs (Jacquier et al., 2011; Sorger and Daum, 2002; Stone et al., 2006). When LDs are consumed during growth resumption, lipases convert TAG into DAG and FAs, which are then used for phospholipid biosynthesis in the ER (Athenstaedt and Daum, 2003; Rajakumari et al., 2010). Three TAG lipases are known in yeast (Tgl3p, 4, 5), with Tgl3p having the strongest effect on TAG hydrolysis in vivo (Athenstaedt and Daum, 2005; Kurat et al., 2006). Phospholipid synthesis from DAG can occur by two alternative pathways, the CDP-DAG and the Kennedy pathway. In the CDP-DAG pathway, DAG is phosphorylated to PA by the kinase Dgk1p. (Figure 1A) (Fakas et al., 2011; Han et al., 2008). In the Kennedy pathway, ethanolamine or choline are phosphorylated and ultimately attached to DAG in the ER (Henry et al., 2012; Kuchler et al., 1986; Natter et al., 2005). Thus, during both LD growth and consumption, DAG must move between LDs and the ER, but it is unknown how the shuttling of this metabolite between the two organelles is achieved. Furthermore, although Dga1p is known to move between the ER and LDs (Jacquier et al., 2011), it is unclear whether its localization is functionally important. More generally, there is as yet no clear picture describing how LDs and the ER are functionally coupled to coordinate neutral and membrane lipid metabolism when cells switch from TAG-synthesis to –consumption.

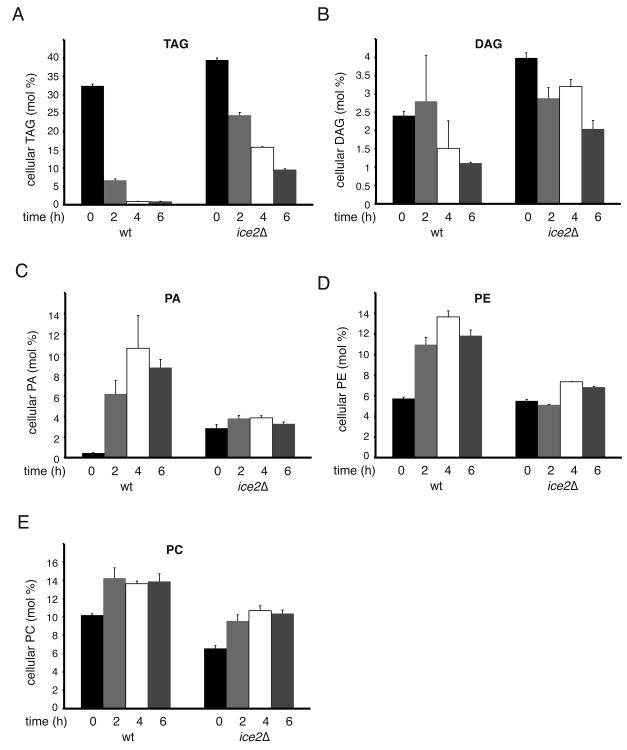

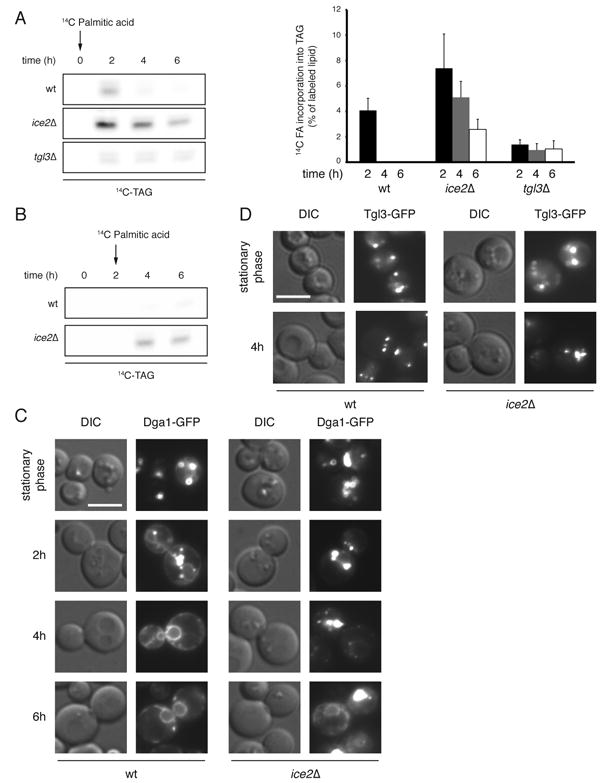

Figure 1. TAG-synthesis and Dga1p-localization on LDs.

(A) Pathways connecting neutral lipid and phospholipid metabolism. Enzymes relevant to the present study are highlighted in red. (B) Wild type cells (WT) expressing Dga1p-GFP from a plasmid or Tgl3p-GFP, and tgl3Δ mutant cells expressing Dga1p-GFP from a plasmid, were grown to stationary phase and then diluted into fresh medium. At the indicated time points of the growth curve (see Supplemental Figure S1), cells were harvested and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar: 5 μm. (C) TAG levels were determined by TLC and iodine staining in WT (black bars) and tgl3Δ (grey bars) cells expressing Dga1p-GFP from a plasmid. Samples were taken at the indicated time points after dilution of stationary cells into fresh medium. Data from three independent experiments are shown as mean +/- SD with the TAG level at t=0 set to 100%. (D) The incorporation of 14C-palmitic acid into TAG was determined. At the indicated time points after dilution of the cells, aliquots were taken and incubated with 14C-palmitic acid for 1h at 30°C.14C-labeled lipids were extracted separated by TLC and quantitated by phosphorimaging and analysis by ImageJ. Labeled TAG was normalized to the total radioactivity in the chloroform-extracted fraction. Data from three independent experiments are shown as mean +/- SD.

Here we have analyzed the functional connection between LDs and the ER in S. cerevisiae. We show that, when LDs grow during early stationary phase, Dga1p moves from the ER to LDs and is responsible for all TAG synthesis from DAG. When cells are supplied with fresh medium, LD consumption for membrane lipid synthesis is facilitated by the ER membrane protein Ice2p. Ice2p has a cytosolic domain with affinity for LDs and is necessary for the efficient channeling of DAG from LDs to membrane lipid synthesis reactions in the ER. It suppresses a futile cycle on LDs between TAG-degradation and -synthesis, ultimately causing Dga1p to re-localize to the ER. Our results provide a simple model for how cells switch neutral lipid metabolism from storage to consumption.

Results

TAG-synthesis and Dga1p-localization on LDs

We first tested in yeast cells whether there is a correlation between TAG synthesis and Dga1p localization on LDs. Previous results showed that Dga1p moves from the ER to LDs when expression of the enzyme is induced in cells lacking all neutral lipid- synthesizing enzymes, and re-localizes back to the ER during induced lipolysis (Jacquier et al., 2011). The re-localization of Dga1p does not require its de novo synthesis (Jacquier et al., 2011). We analyzed whether the localization of Dga1p would change under physiological conditions during different growth phases. We indeed found that Dga1p is localized to LDs during late exponential and stationary phases, and re-localizes to the ER when cells resume growth after dilution into fresh medium (Figure 1B). The localization of Dga1p correlated with the TAG levels, as determined by thin-layer chromatography and iodine staining (Figure 1C). In stationary phase, when Dga1p is on LDs, TAG levels were high, whereas TAG decreased when Dga1p re-localized to the ER. To directly test the role of Dga1p in TAG synthesis, we measured the incorporation of 14C-labeled FA into TAG by thin-layer chromatography followed by autoradiography. We found that TAG synthesis in stationary phase was almost completely abolished when Dga1p was absent (Figure 1D). In contrast, dga1 deletion had a negligible effect on TAG synthesis during exponential growth phase. Previous studies have shown that Lro1p, the other diacylglycerol-acyl transferase, has a stronger effect on TAG synthesis during exponential phase compared to stationary phase (Oelkers et al., 2002). These results suggest that, in wild type cells, the initial accumulation of TAGs during exponential phase occurs by Lro1p in the ER, whereas TAG synthesis during the growth of LDs in stationary phase is mainly caused by LD-localized Dga1p.

Next we tested the localization of the major TAG lipase Tgl3p. In contrast to Dga1p, Tgl3p is localized constitutively to LDs, both in stationary and exponentially growing cells (Figure 1B). Consistent with previous studies, in the absence of Tgl3p, TAG levels were high during all growth phases (Figure 1C) (Athenstaedt and Daum, 2003; Kurat et al., 2006).

Interestingly, Dga1p remained on LDs in tgl3Δ cells even during early exponential phase, suggesting that its re-localization to the ER in wild type cells is caused by a decrease in TAG levels (Figure 1 B). At early time points during growth resumption, when TAG levels are still high, both Dga1p and Tgl3p are present on LDs, raising the question of how net TAG degradation is initiated. One possibility is that the Dga1p substrate DAG is moved from LDs to the ER, thereby turning off TAG synthesis on LDs.

Identification of Ice2p as a component functionally linking LDs and the ER

If the movement of DAG from LDs to the ER involves a protein, we reasoned that such a component should affect the delivery of DAG to Dgk1p in the CDP-DAG pathway and to enzymes in the Kennedy pathway, the two parallel pathways that use DAG for phospholipid synthesis in the ER. The effect of deletion of these enzymes on cell growth should be exacerbated if DAG channeling into the ER is reduced. We therefore searched the DRYGIN database for genes that have negative interactions with both dgk1 and components of the Kennedy pathway. We found ice2 to show a strong negative genetic interaction with dgk1 (i.e. cells lacking both Dgk1p and Ice2p grow slower than cells lacking only one of these proteins) (Costanzo et al., 2010; Garbarino et al., 2009; Koh et al., 2010; Schuldiner et al., 2005; Tavassoli et al., 2013). Ice2p shows many additional genetic interactions with other lipid metabolizing enzymes, including components of the Kennedy pathway (Supplemental Table 3) (Costanzo et al., 2010; Koh et al., 2010; Tavassoli et al., 2013). The genetic interaction partners of Ice2p are most similar to those of Dgk1p (Koh et al., 2010). Importantly, Ice2p also shows a positive interaction with Pah1p, the enzyme that converts PA back into DAG, indicating that Ice2p might indeed be involved in providing DAG for downstream reactions. Based on these data, Ice2p could be at the functional interface between LDs and the ER, and potentially be involved in DAG movement between the organelles.

Ice2p is not essential for the viability of S. cerevisiae, but cells lacking the protein grow significantly slower than wild type cells. In addition, after dilution of stationary phase cells into fresh medium, an extended lag phase was observed (Figure 2A). To test whether this is caused by a defect in the utilization of LDs for phospholipid synthesis, we determined the growth of cells after dilution of stationary phase into medium containing cerulenin, an inhibitor of FA synthesis (Inokoshi et al., 1994); under these conditions, cells completely rely on the degradation of TAG from LDs (Athenstaedt and Daum, 2003, 2005; Kurat et al., 2006). In the presence of cerulenin, growth of wild type cells was not affected until up to 4h, whereas ice2Δ cells barely grew at all from the start (Figure 2A). After 4 h also wild type cells stopped growing in the presence of cerulenin. These results suggest that Ice2p is required for rapid resumption of cell growth after dilution into fresh medium likely by facilitating the efficient utilization of TAG for phospholipid biosynthesis. This is consistent with a role for Ice2p in DAG channeling from LDs to the ER for phospholipid synthesis. It should be noted that a dgk1 deletion mutant only grows slower than wild type cells in the presence of cerulenin (Fakas et al., 2011), indicating that deletion of ice2 has a stronger growth defect than that of dgk1, probably because a dgk1 deletion can be bypassed by alternative reactions, such as the Kennedy pathway. In addition, Ice2p overexpression did not rescue the growth defect of a dgk1 deletion mutant (data not shown). These results are consistent with the idea that Ice2p functions upstream of Dgk1p.

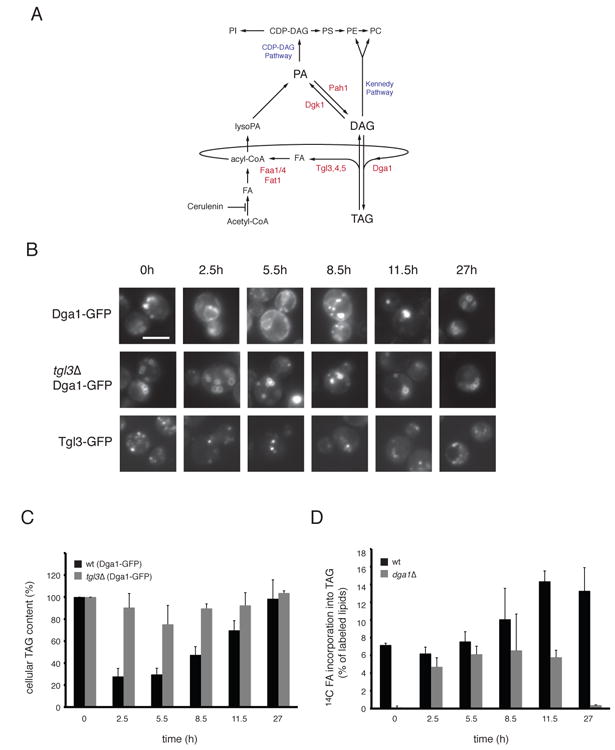

Figure 2. Ice2p is a component involved in TAG metabolism.

(A) Wild type (WT) or ice2Δ mutant cells in stationary phase were diluted into fresh medium lacking or containing 10μg/ml cerulenin, and their growth was followed by measuring the OD at 600nm. Shown are the mean +/- SD of three independent experiments. (B) TAG levels in WT and ice2Δ cells, harvested at early exponential phase, were determined after lipid extraction and analysis by mass spectrometry. Data from three independent experiments are shown as mean +/- SD. (C) LDs were stained with BODIPY 493/503 at early exponential phase and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Lipid droplets were quantitated using CellProfiler software (n, number of cells analyzed). Scale bar: 5μm.

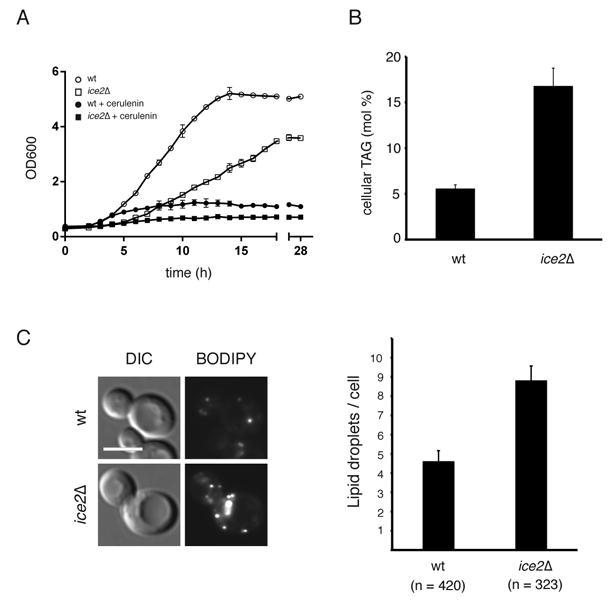

The absence of Ice2p led to three-fold higher TAG levels in exponentially growing cells, determined by quantitative lipid mass spectrometry (Figure 2B). In addition, visualization of BODPIY 493/503-labeled LDs showed that ice2Δ cells also had a two-fold increase in the number of LDs per cell (Figure 2C). Direct measurements of TAG breakdown showed that cells lacking Ice2p had a strong delay in TAG degradation, almost as strong as in tgl3Δ cells, as measured by thin-layer chromatography and iodine staining after diluting stationary cells into fresh medium in the presence (Figure 3A) or absence of cerulenin (Figure 3B). Furthermore, BODIPY 493/503-labeled LDs persisted in ice2Δ cells in the presence of cerulenin, whereas they were rapidly consumed in wild type cells (Figure 3C). Taken together, these results suggest that Ice2p is required for the efficient consumption of LDs for phospholipid synthesis during growth resumption.

Figure 3. Ice2p is required for the efficient utilization of LDs during growth resumption.

(A) TAG degradation was followed in wild type (WT), ice2Δ, and tgl3Δ mutant cells after dilution of stationary phase cells into fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin. At the indicated time points, lipids were extracted and analyzed by TLC followed by iodine staining. The graphs show quantification of three independent experiments (mean +/- SD) with the TAG level at t=0 set to 100%. (B) As in (A), but stationary cells were diluted into fresh medium without cerulenin. (C) The consumption of LDs in WT and ice2Δ cells after dilution from stationary phase into fresh medium containing 10μg/ml cerulenin was followed by BODIPY 493/503 staining and fluorescence microscopy. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Ice2p promotes TAG consumption for phospholipid synthesis

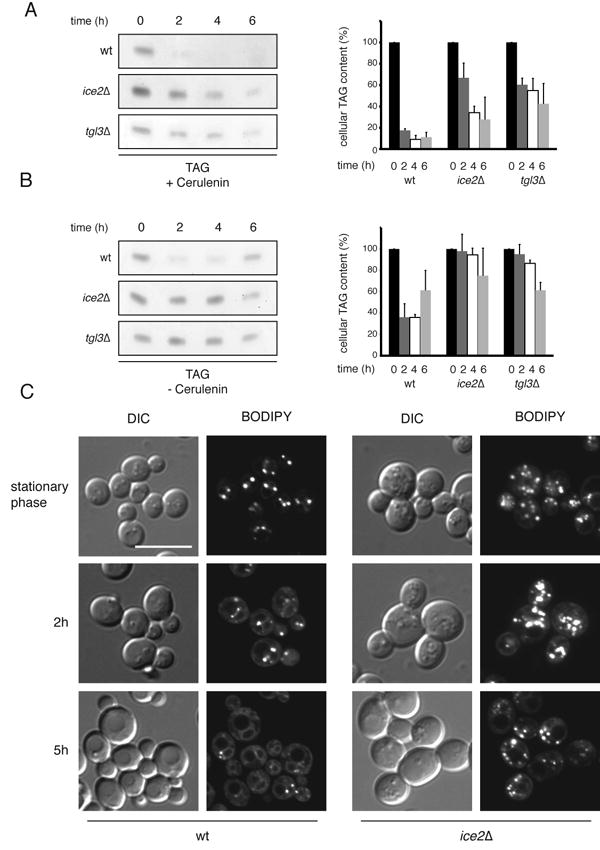

Consistent with a role of Ice2p in TAG utilization for phospholipid synthesis during growth resumption, a lipid analysis by mass spectrometry showed that, even in the absence of cerulenin, ice2Δ cells have decreased levels of phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE), and slightly reduced levels of phosphatidyl choline (PC) (Supplemental Figure S2A). The decreased levels of PE are not caused by a possible effect of Ice2p on the transport of PS from the ER to mitochondria for decarboxylation, as no effect of ice2 deletion was observed in an in vitro assay (Supplemental Figure S2B).

To further test the function of Ice2p, we diluted stationary cells into fresh medium in the presence of cerulenin and performed quantitative lipid mass spectrometry at different time points. In wild type cells, TAG levels decreased rapidly, whereas PA, PE and PC increased (Figure 4A, C, D, E). DAG decreased with some delay, as expected from it being an intermediate metabolite (Figure 4B). In ice2Δ cells, TAG degradation was significantly delayed, and DAG levels remained high, particularly at later time points (Figure 4A, B). No or little increase in phospholipid levels was observed (Figure 4C, D, E). These data show that, in ice2Δ cells, LD-derived DAG cannot be utilized by the PA-generating enzyme Dgk1p in the ER, ultimately affecting the synthesis of PA, PE, and PC. No major differences in the levels of PS and PI between wild type and ice2Δ cells were observed during growth resumption (Supplemental Figures S3A). Together, these results support the idea that Ice2p is required for the efficient channeling of DAG from LDs to the ER for phospholipid synthesis. It should be noted that the growth defect of ice2Δ cells could not be rescued with 1 mM ethanolamine or choline (data not shown), compounds that would stimulate phospholipid synthesis via the Kennedy pathway if DAG were available in the ER. These results support the notion that Ice2p is required for the efficient channeling of DAG from LDs to the ER for phospholipid synthesis and acts upstream of Dgk1p.

Figure 4. Ice2p promotes TAG consumption for phospholipid synthesis.

(A)-(E) The lipid composition of wild type (WT) and ice2Δ cells was analyzed at different time points after dilution from stationary phase into fresh medium containing 10μg/ml cerulenin. The indicated lipid species were analyzed by quantitative mass spectrometry. Data from two independent experiments were analyzed in duplicates and are shown as mean +/- SD.

Ice2p facilitates metabolic channeling of DAG from LDs to the ER

If Ice2p were required for channeling of DAG from LDs to the ER during growth resumption, one would expect that, in the absence of Ice2p, DAG would be generated by lipases such as Tgl3p, but would not be available for the Dgk1p enzyme in the ER. This would be expected to lead to a futile cycle, in which TAG is continuously broken down and resynthesized from DAG by Dga1p (Figure 1A).

This assumption is supported by experiments in which we radiolabeled TAG and studied its conversion into DAG during growth resumption in the presence of cerulenin. In agreement with the mass spectrometry results, ice2 deletion led to delayed TAG degradation and increased DAG levels (Supplemental Figure S3B,C). Importantly, the simultaneous absence of both Ice2p and Dga1p did not change TAG degradation, but led to even higher DAG levels, consistent with a disrupted futile cycle. As expected, the absence of Tgl3p impaired TAG hydrolysis and resulted in rapid consumption of DAG (Figures S3B,C).

To directly test the re-synthesis of TAG from DAG, we added 14C-labeled palmitic acid to cells immediately after dilution from stationary phase into fresh medium containing cerulenin. The incorporation of labeled FA into TAG was followed by thin-layer chromatography and autoradiography. Wild type cells showed some weak, transient TAG labeling, whereas ice2Δ cells synthesized TAG over an extended period (Figure 5A). Cells lacking the major lipase Tgl3p showed very little TAG synthesis. When 14C-labeled palmitic acid was added 2 hours after dilution into fresh medium, wild type cells did not incorporate any label into TAG, whereas TAG synthesis was still observed in ice2Δ cells (Figure 5B). In wild type cells diluted into fresh medium containing cerulenin, the esterification of DAG with 14C-labeled palmitic acid was completely dependent on Dga1p (Supplemental Figure S4A), confirming that this is the major enzyme required for the re-synthesis of TAG on LDs (see also Figure 1D). Cells lacking both Ice2p and Dga1p still showed some re-esterification (Supplemental Figure S4A). Given that Lro1p can localize close to LDs in stationary phase (Wang and Lee, 2012), we assume that it partially replaces Dga1p under these conditions, preventing the accumulation of toxic DAG levels. Similar results were obtained when 14C-labeled oleic acid was used instead of 14C-labeled palmitic acid (Figure S4B). Taken together, these results provide strong support for the idea that, in ice2Δ cells, there is continuous re-esterification of DAG generated by hydrolysis from TAG; in the absence of TAG hydrolysis (in tgl3Δ cells), less DAG is generated that could serve as a substrate for re-synthesis of TAG. Consistent with this model, Dga1p stayed on LDs in ice2Δ cells when cells were diluted into fresh medium containing cerulenin, in contrast to the situation in wild type cells, where it moved to the ER (Figure 5C). Tgl3p also stayed on LDs in ice2Δ cells (Figure 5D). Thus, in the absence of Ice2p, there is a futile cycle on LDs in which TAG is broken down by Tgl3p and re-synthesized by Dga1p. The activation of the FA generated by Tgl3p can occur by the acyl-CoA synthetases Faa1p, Faa4p, and Fat1p, which all have been reported to localize to LDs (Athenstaedt et al., 1999; Natter et al., 2005).

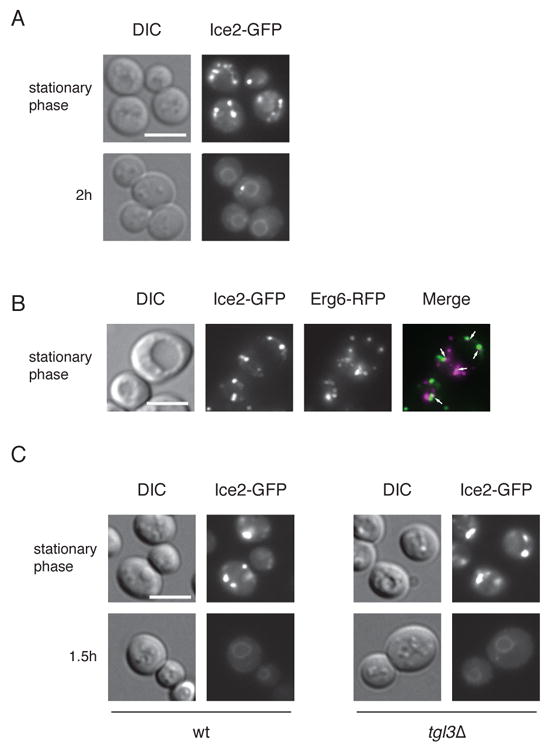

Figure 5. Ice2p suppresses a futile cycle between TAG and DAG on LDs.

(A) The re-synthesis of TAG in wild type (WT), ice2Δ, and tgl3Δ mutant cells was analyzed by adding 14C-palmitic acid to cells immediately after their dilution from stationary phase into fresh medium containing 10μg/ml cerulenin. At the indicated time points aliquots were taken, lipids were extracted and analyzed by TLC. Labeled TAG on the TLC plate (left panel) was quantitated by phosphorimaging (right panel). The data were normalized to the total radioactivity in the chloroform-extracted fraction. and are presented as mean +/- SD of four independent expriments. (B) As in (A), but the 14C-palmitic acid was added 2 h after dilution of WT or ice2Δ cells. (C) The localization of Dga1p-GFP, expressed from a plasmid, was followed by fluorescence microscopy in WT and ice2Δ cells after dilution from stationary phase into fresh medium containing 10μg/ml cerulenin. (D) As in (C), but the localization of Tgl3p-GFP was determined in stationary phase and 4 h after dilution. Scale bars: 5μm.

Ice2p links LDs to the ER for efficient DAG shuttling

If Ice2p has a role in channeling DAG from LDs to the ER, one would expect that it localizes to the interface between the two organelles. In agreement with previous results (Estrada de Martin et al., 2005), GFP-tagged Ice2p (Ice2p-GFP) localized to the ER in exponentially growing cells (Figure 6A; the GFP-tagged protein is functional, see Supplemental Figure S5A). However, in stationary phase, Ice2p-GFP accumulated in punctate structures adjacent to LDs labeled with Erg6p-RFP (Figure 6A, B). When stationary cells were diluted into fresh medium, Ice2p-GFP rapidly re-localized from the LD-proximal sites back to the ER (Figure 6C). Re-localization of Ice2p-GFP occurred within 30min after dilution, preceding the re-localization of Dga1p to the ER (Figure S5B). Interestingly, re-localization of Ice2p-GFP to the ER was also observed in tgl3Δ cells (Figure 6C) where Dga1p stayed on LDs (see Figure 1B), indicating that Ice2p localization is not determined by TAG levels in LDs. Overexpressed Ice2p-GFP localized to the ER, but when oleate was added to generate large LDs, it was also found in sheet structures around LDs (Supplemental Figure S5C).

Figure 6. Growth phase-dependent localization of Ice2p.

(A) The localization of Ice2p-GFP was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy at stationary phase and 2h after dilution into fresh medium. (B) The localization of Ice2-GFP was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy in stationary phase cells expressing Erg6-RFP. Six optical sections along the z-axis were collected with a step size of 0.5μm. A maximum projection is shown. Arrows indicate areas of contact between Ice2-GFP and Erg6-RFP labeled LDs. (C) The localization of Ice2p-GFP was analyzed in wild type (WT) and tgl3Δ mutant cells in stationary phase and after 1.5 h dilution into fresh medium containing 10μg/ml cerulenin. Scale bars: 5μm.

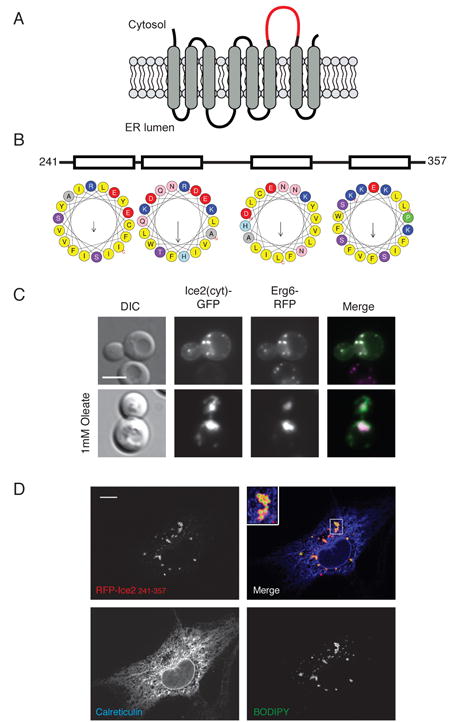

The localization of Ice2p to LD-proximal sites suggested that the protein might have a segment that interacts with LDs. Ice2p is a predicted multi-spanning membrane protein with only one sizable hydrophilic domain (TMHMM server v 2.0; see scheme in Figure 7A) (Estrada de Martin et al., 2005). This domain is predicted to be on the cytoplasmic side of the ER membrane (Ice2(cyt)) and would thus be a candidate to interact with LDs. Indeed, it is predicted to contain four amphipathic helices (Jpred, PSIPRED v3.3, PredictProtein, Robetta, Figure 7B), a common LD targeting motif (Walther and Farese, 2012). To test whether this domain interacts with LDs, we expressed this segment as a GFP fusion (Ice2(cyt)-GFP) in yeast cells together with the LD marker Erg6p-RFP. Both proteins co-localized (Figure 7C), indicating that the cytoplasmic domain of Ice2p indeed has an affinity for LDs. Occasionally, some ER staining was also seen (Figure S6A). When cells were incubated with oleate to generate large LDs, Ice2(cyt)-GFP localized exclusively to LDs ( Figure 7C).

Figure 7. A cytoplasmic domain of Ice2p binds to lipid droplets.

(A) Predicted topology of Ice2p. The largest cytoplasmic loop (amino acids 241-357) is highlighted. (B) Predicted secondary structure of the cytoplasmic loop of Ice2p. Helical wheel representations of predicted helices were generated using the program HeliQuest (http://heliquest.ipmc.cnrs.fr/) (C) The localization of a fusion between the cytosolic loop and GFP (Ice2(cyt)-GFP), expressed from a plasmid, was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy in exponentially growing cells. The cells also expressed Erg6p-RFP as a marker for LDs. Scale bar: 5 μm. (D) As in (C), but cells were grown in the presence of 1 mM oleate. (E) The localization of RFP-Ice2(cyt) was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy in COS7 cells. The cells were also stained with BODIPY 493/503 for LDs and for the ER marker calreticulin by immunofluorescence microscopy. Scale bar: 10 μm.

To further ascertain that the cytoplasmic domain of Ice2p interacts with LDs, we expressed an RFP-fusion (RFP-Ice2(cyt)) in mammalian COS7 cells. The protein localized to the surface of LDs stained with BODIPY 493/503; no co-localization with the ER marker calreticulin was observed (Figure 7D). Given that Ice2p has no obvious homolog in mammalian cells, these data suggest that the cytoplasmic domain interacts with the lipids in LDs, rather than with a protein.

Finally, the overexpression of a mutant of Ice2p lacking the cytoplasmic domain only partially rescued the growth phenotype of an ice2Δ strain (Figure S6C). The protein localized to the ER (Figure S6B), but did not accelerate TAG breakdown or prevent the accumulation of DAG (Figure S6D, E) in ice2Δ cells. Taken together, these results support the idea that the ER membrane protein Ice2p has a cytoplasmic domain that interacts with LDs and is required for its function.

Discussion

We show that during LD growth in late exponential and stationary phase, all TAG synthesis occurs by Dga1p on LDs. Net TAG consumption during growth resumption is achieved by lipases, such as Tgl3p, that always stay on LDs. However, because Dga1p is also initially localized to LDs during growth resumption, there must be a mechanism that suppresses a futile cycle between DAG and TAG to allow net TAG degradation. We show that during early phases of TAG breakdown, futile cycling is inhibited by Ice2p, a multi-spanning membrane protein of the ER. Ice2p facilitates the channeling of DAG from LDs to the ER, a process that shifts the metabolism to efficient phospholipid synthesis and prevents the accumulation of toxic DAG levels. The Ice2p-mediated regulation of a futile cycle on LDs thus presents an important regulatory mechanism in lipid homeostasis. Ice2p has a cytoplasmic loop that targets it to LDs. In a second phase, when TAG levels are sufficiently reduced, Dga1p is moved from LDs to the ER, terminating TAG synthesis on LDs. These results explain how yeast cells can switch from TAG-synthesis to –consumption.

In S. cerevisiae, essentially all LDs appear to be in close proximity of the ER (Szymanski et al., 2007; Wolinski et al., 2011). Fluorescence recovery after photo-bleaching (FRAP) experiments suggest that LDs may be associated with the ER through phospholipids (Jacquier et al., 2011). LDs remain close to the ER in ice2Δ cells (data not shown), indicating that Ice2p is not required for the attachment of the two organelles. Ice2p function does not seem to be restricted to the interface between LDs and the ER. In fact, during growth resumption, Ice2p re-localizes much faster from an LD-associated ER domain to the bulk ER than TAG levels decrease (Figure S5B). Its steady state distribution during different growth phases thus reflects the primary site of DAG utilization; it localizes to the proximity of LDs during DAG to TAG conversion in LDs, and to the bulk ER during DAG utilization by phospholipid synthesizing enzymes. One possible model for how Ice2p might function is that it shuttles DAG directly between the two organelles. If Ice2p is required for the shuttling of DAG, one would have to assume that there is a barrier between LDs and the ER that prevents the free diffusion of the metabolite, despite the fact that the two organelles are contiguous. In principle, Ice2p could also be an activator of Dgk1p, but this would not explain the genetic interaction between the two proteins.

We consider it unlikely that Ice2p is required for metabolic channeling of FA, the other breakdown product of TAG. In contrast to DAG, FA utilization may not require physical contact between LDs and the ER. FAs could be efficiently activated on LDs by acyl-CoA synthetases (Athenstaedt et al., 1999; Natter et al., 2005), and subsequently be moved by acyl-CoA binding proteins through the cytosol to the ER, mitochondria, or peroxisomes (Rasmussen et al., 1994).

Our results lead to a simple model for how yeast cells can switch from TAG-synthesis to –consumption during different growth phases. During late exponential and early stationary phase, Pah1p generates DAG, and Dga1p moves to LDs, where it converts DAG into TAG. LD-localized TAG synthesis by enzymes that move from the ER to growing LDs has also been observed in mammalian cells (Wilfling et al., 2013). In contrast, the ER-localized acyl transferase Lro1p, the other major enzyme converting DAG into TAG in yeast, appears to have its major role in TAG synthesis during exponential growth (Oelkers et al., 2002). Thus, in wild type cells, it may generate the first TAG molecules when LDs are formed de novo, whereas Dga1p would move into the LDs and take over TAG synthesis only when the LDs have reached a sufficient size. The ER-localized DGAT1 enzyme in mammalian cells can also only generate small LDs (Wilfling et al., 2013). However, it should be noted that in yeast cells lacking Lro1p, Dga1p alone is sufficient to generate LDs (Sandager et al., 2002), and it is possible that Lro1p can partially replace Dga1p in ice2Δ dga1Δ cells to recycle DAG to TAG (Figure S4A).

When cells exit stationary phase and resume growth, TAG is hydrolyzed to DAG and FA by lipases such as Tgl3p, DAG is channeled back into the ER by Ice2p and utilized by Dgk1p and the Kennedy pathway for phospholipid synthesis. When TAG levels are sufficiently reduced, Dga1p is moved from LDs to the ER, terminating TAG synthesis on LDs. Previous results indicated that regulated lipase activity is critical for efficient growth resumption (Kurat et al., 2009), but our experiments now indicate that there is an important step in the ER succeeding actual TAG hydrolysis. Recent results in mammalian cells suggest that lipases can degrade TAG to 1,3-DAG (Eichmann et al., 2012), which cannot directly be used for phospholipid synthesis. However, 1,3-DAG is the preferred substrate for DGAT-2, the homolog of yeast Dga1p, suggesting that a futile cycle between TAG and DAG occurs in mammals as well (Eichmann et al., 2012). We have not been able to detect 1,3-DAG in our TAG degradation experiments in yeast (data not shown), so it is possible that 1,2-DAG is used for both TAG and phospholipid synthesis. In both mammals and yeast, it is also conceivable that isomerases exist, which interconvert the DAG species. Regardless of the specificity of the lipases, our results indicate that the switch between net TAG-synthesis and – hydrolysis would be determined by three factors: 1. generation or consumption of DAG in the ER, 2. Ice2p-mediated metabolic channeling of DAG from LDs to the ER, and 3. Movement of Dga1p between the ER and LDs.

How does Dga1p move between the ER and LDs? We assume that it behaves similar to its mammalian homolog, DGAT2, which has an N-terminal hydrophobic domain, but no hydrophilic segment on the luminal side of the ER membrane, allowing it to sit not only in the lipid bilayer of the ER, but also in the monolayer of LDs (Stone et al., 2006; Wilfling et al., 2013). Our results support the idea that Dga1p partitions into LDs simply because of its interaction with the hydrophobic core of LDs or the surrounding monolayer. Such a model would also explain why several other proteins, including Erg6p and Faa4p in yeast, and DGAT2, CCT, and PAT proteins in mammals, associate with expanding LDs, despite the fact that they do not share sequence similarity (Athenstaedt et al., 1999; Bickel et al., 2009; Jacquier et al., 2011; Krahmer et al., 2011; Wilfling et al., 2013). Targeting of Ice2p to LD proximal ER domains is mediated by a cytosolic loop. This domain is predicted to contain four amphipathic helices. A similar motif is found in the LD-binding protein TIP47 and the neutral lipid-interacting apolipoprotein E (apo E) (Walther and Farese, 2012). Structures for these proteins showed that the amphipathic helices are arranged in a four-helix bundle, which is stabilized by a hydrophobic core (Hickenbottom et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 1991). Opening of the four-helix bundle and exposure of hydrophobic sequences allows apo E to bind to lipid surfaces (Brasaemle, 2007; Raussens et al., 1998). A similar mechanism is discussed for TIP47, which would allow its movement from the cytosol to nascent lipid droplets (Bulankina et al., 2009). It is thus tempting to speculate that the cytosolic domain of Ice2p is also arranged in a four-helix bundle and, upon rearrangement, would expose hydrophobic surfaces for interaction with LDs. Interestingly, the cytoplasmic domain of Ice2p localized to LDs even in exponentially growing cells (Figure 7C), when the full-length Ice2p was found in the ER (Figure 6A, C). This result would be consistent with the possibility that Ice2p undergoes a conformational change when cells enter stationary phase, exposing the cytosolic domain for interaction with LDs.

DAG channeling between LDs and the ER might also occur in higher eukaryotes, but its importance might differ between cell types. In adipocytes, TAGs serve primarily as an energy source and are therefore further hydrolyzed to mono-acylglycerol and glycerol (Duncan et al., 2007; Zechner et al., 2009). In contrast, in the liver of mammals, lipolytic products of TAG are precursors for lipoprotein particle synthesis in the ER (Lankester et al., 1998; Wiggins and Gibbons, 1992; Yang et al., 1995). Thus, it is possible that similar pathways as in S. cerevisiae may exist, albeit with components that have no obvious sequence similarity.

Ice2p had previously been implicated in ER inheritance from the mother to the daughter cell (Estrada de Martin et al., 2005). The effect of ice2 deletion on ER morphology is only observed at early stages of bud formation and is relatively weak. It can easily be explained by our observation that Ice2p plays a role in the conversion of TAG into phospholipids. Consistent with this explanation, cells lacking both Ice2p and Scs2p, a protein that binds the transcriptional repressor Opi1p to regulate phospholipid-synthesizing enzymes (Henry et al., 2012; Kagiwada et al., 1998; Loewen and Levine, 2005), have increased defects in cortical ER morphology (Loewen et al., 2007; Tavassoli et al., 2013). Ice2p has also been described as a protein required for optimal growth when Zn2+ ions are limiting (North et al., 2012). Although in our experiments Zn2+ is not limiting (data not shown), it is easy to see why the deletion of Ice2p would exacerbate the effect of low Zn2+ concentrations. Deletion of ice2 leads to lower phospholipid levels, and low Zn2+ levels also result in lowered PS and PE levels, caused by the activation of phosphatidyl inositol synthetase (Pis1p) and of the PA hydrolase Pah1p through relieve of Zn2+-dependent transcription repression (Han et al., 2005; Henry et al., 2012; Soto-Cardalda et al., 2012). Taken together, the identification of the function of Ice2p in DAG channeling from LDs to the ER explains a number of previous seemingly unrelated and puzzling observations.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast Strains and Plasmids

Tagging of proteins and gene deletions were performed by standard PCR-based homologous recombination (Longtine et al., 1998). Strains used in this study are isogenic to BY4741 (Mat a ura3Δ his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0) and are listed in Table S1. Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S2 and described in the Supplemental Information.

Growth conditions

Cells were grown at 30°C in synthetic complete (SC) medium. SC medium contained 1.7 mg/L yeast nitrogen base without ammonium sulfate (MP Biomedical, USA), 5 g/L ammonium sulfate (Sigma Aldrich), 20 g/L glucose, and was supplemented with the required amino acid mixtures (CSM 0.79 g/L; CSM-LEU 0.69 g/L; Sunrise Science Products, USA). For growth resumption from stationary phase, logarithmically grown pre-cultures were diluted to 0.5 A600nm-units/ml and grown overnight to reach stationary phase. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and diluted into fresh medium to A600nm of 0.3 (for growth analysis) or 1 (for lipid analyses). Where indicated, cerulenin was added to cultures from a 10mg/ml stock solution in ethanol to a final concentraion of 10 μg/ml. For lipidomics analysis, the cells were grown in SC medium containing 2% glucose.

Lipid analysis and TAG degradation in vivo

Lipids were extracted according to (Folch et al., 1957). In brief, equal amounts of cells were centrifuged, washed once in ice-cold water, resuspended in 330μl of methanol and disrupted for 10min by Vortex mixing with 100μl of glass beads. 660μl of chloroform was added and the samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000×g to remove debris. The organic solvent supernatant was recovered and washed once with 0.9% NaCl. The lower chloroform phase was dried under a stream of nitrogen, the lipids were resupended in 20μl chloroform, and separated by TLC on Silica60 plates using as a solvent petroleum/diethylether/glacial acetic acid (80/20/1.5 v/v/v). For the analysis of TAG levels in Figure 1C and 3A, B, the cells were grown to stationary phase, collected by centrifugation and resuspended in fresh medium to 1 A600nm-units/ml. At the indicated time points, 10 A600nm-units of cells were processed as described above. Lipids were visualized on TLC plates by staining the plates with iodine vapor. They were identified by comparison with lipid standards. The plates were scanned and the lipid species were quantified using ImageJ. The linearity of iodine staining in the range observed in the experiments was confirmed by anaylsis of TAG standard curves (Figure S1B). For analyzing TAG degradation in vivo (Figure S3B, C; S6D, E), cells were grown to stationary phase in the presence of [1,2-14C]-acetic acid (0.1 μCi/ml; Perkin Elmer, USA). After harvesting, the cells were resuspended in fresh, unlabeled medium to 1 A600nm-unit/ml. At the indicated time points, 5 A600nm-units of cells were processed as described above. Labeled lipids were visualized using a Phosphoimager (BioRad, PMI) and quantified using ImageJ. To analyze the re-esterification of DAG during growth resumption, the cells were grown to stationary phase and diluted into fresh medium containing 10μg/ml cerulenin and [1-14C]-Palmitic acid (0.1μCi/ml; Perkin Elmer, USA) or [1-14C]-Oleic acid (0.1μCi/ml; Perkin Elmer, USA) to 1 A600nm-unit/ml. At the indicated time points, 5 A600nm-units of cells were processed as described above.

Fluorescence microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, yeast cells expressing the indicated GFP- or RFP- tagged proteins were grown in SC medium containing 2% glucose to stationary phase. Where indicated, the cells were diluted into fresh medium in the presence or absence of 10μg/ml cerulenin. The cells were collected by centrifugation, and washed once with PBS buffer before imaging. For staining of lipid droplets, aliquots of cells were incubated with BODIPY 493/503 (final concentration 1μg/ml) for 15 min at 30°C. The cells were washed twice with PBS before imaging. For the quantification of Lipid droplets per cell, ten randomly chosen microscopy images of BODIPY stained wt or ice2Δ cells were analyzed. The number of BODIPY 493/503 stained lipid droplets per cells in each image was determined using the CellProfiler software.

COS7 cells were transfected using 1μg DNA of plasmid and the transfection reagent lipofectamine (Invitrogen). The cells were incubated for 12 hours at 37°C in DMEM, 10% FBS and 1mM sodium pyruvate in the presence of 5% CO2. For immunofluorescence and fluorescence microscopy, the cells were trypsinized, transferred onto acid-washed glass cover slips, and incubated for 24 hours in a 12-well tissue culture dish (BD Biosciences). The cells were fixed by replacing the medium with PBS containing 4% para-formaldehyde and incubated for 20-30 min at room temperature. They were washed with PBS and permeablized by incubation for 10 min in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Thermo). Immunocytochemistry was carried out by incubating the permeabilized cells with antibodies against calreticulin, diluted in PBS containing 1% calf serum (Gibco). The cells were washed three times in PBS and then incubated with Alexafluor-labeled secondary antibodies and 0.1μg/ml BODIPY 493 (Invitrogen).

Images were acquired using a Nikon Ti motorized inverted microscope equipped with 100x Plan Apo N 1.4 objective lens, a Hamamatsu ORCA-R2 cooled CCD camera, and Metamorph 7 software. Alternatively (Figure 7D, S5C), images were captured using a Nikon TE2000U inverted microscope with a 100x Plan Apo NA 1.4 objective lens, a Hamamatsu ORCA ER cooled CCD camera, and MetaMorph software. The images were processed using Adope Photoshop CS3.

Lipidome analysis by mass spectrometry

Samples for the lipidome analysis in Figure 2B, S2A were harvested from cultures of yeast growing exponentially in SC medium containing 2% glucose, washed once in water at 4°C, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples for analysis in Figure 4, S3A were harvested at different time points after diluting stationary phase cells into fresh medium containing 10 μg/ml cerulenin and processed as described above. Lipid analysis was performed using a Triversa NanoMate ion source (Advion Biosciences, Inc.) and a LTQ Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), as previously described (Ejsing et al., 2009).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean +/- SD of three independent experiments. Results in Figure 4, S3A are from two independent experiments, analyzed in duplicates and are presented as mean +/- SD.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Lipid droplets (LDs) increase in size by triacylglycerol (TAG) synthesis on LDs

Consumption of LDs requires their functional interaction with the ER

The ER protein Ice2p suppresses futile cycling between TAG breakdown and synthesis

Ice2p interacts with LDs and promotes TAG utilization for phospholipid synthesis

Acknowledgments

We thank the Nikon Imaging center at Harvard Medical School for help, Albert Casanovas for constructive discussions and Pedro Carvalho for critically reading the manuscript. C. Ejsing is supported by Lundbeckfonden (R44-A4342, R54-A5858) and the Danish Council for Independent Research | Natural Sciences (09-072484). T.A.R. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Accioly MT, Pacheco P, Maya-Monteiro CM, Carrossini N, Robbs BK, Oliveira SS, Kaufmann C, Morgado-Diaz JA, Bozza PT, Viola JP. Lipid bodies are reservoirs of cyclooxygenase-2 and sites of prostaglandin-E2 synthesis in colon cancer cells. Cancer research. 2008;68:1732–1740. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adeyo O, Horn PJ, Lee S, Binns DD, Chandrahas A, Chapman KD, Goodman JM. The yeast lipin orthologue Pah1p is important for biogenesis of lipid droplets. The Journal of cell biology. 2011;192:1043–1055. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athenstaedt K, Daum G. YMR313c/TGL3 encodes a novel triacylglycerol lipase located in lipid particles of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:23317–23323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302577200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athenstaedt K, Daum G. Tgl4p and Tgl5p, two triacylglycerol lipases of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae are localized to lipid particles. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:37301–37309. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507261200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athenstaedt K, Zweytick D, Jandrositz A, Kohlwein SD, Daum G. Identification and characterization of major lipid particle proteins of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of bacteriology. 1999;181:6441–6448. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6441-6448.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel PE, Tansey JT, Welte MA. PAT proteins, an ancient family of lipid droplet proteins that regulate cellular lipid stores. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1791:419–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brasaemle DL. Thematic review series: adipocyte biology. The perilipin family of structural lipid droplet proteins: stabilization of lipid droplets and control of lipolysis. Journal of lipid research. 2007;48:2547–2559. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R700014-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulankina AV, Deggerich A, Wenzel D, Mutenda K, Wittmann JG, Rudolph MG, Burger KN, Honing S. TIP47 functions in the biogenesis of lipid droplets. The Journal of cell biology. 2009;185:641–655. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200812042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HS, Su WM, Morgan JM, Han GS, Xu Z, Karanasios E, Siniossoglou S, Carman GM. Phosphorylation of phosphatidate phosphatase regulates its membrane association and physiological functions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: identification of SER(602), THR(723), AND SER(744) as the sites phosphorylated by CDC28 (CDK1)-encoded cyclin-dependent kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:1486–1498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.155598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary V, Jacquier N, Schneiter R. The topology of the triacylglycerol synthesizing enzyme Lro1 indicates that neutral lipids can be produced within the luminal compartment of the endoplasmatic reticulum: Implications for the biogenesis of lipid droplets. Communicative & integrative biology. 2011;4:781–784. doi: 10.4161/cib.17830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Bellay J, Kim Y, Spear ED, Sevier CS, Ding H, Koh JL, Toufighi K, Mostafavi S, Prinz J, St Onge RP, VanderSluis B, Makhnevych T, Vizeacoumar FJ, Alizadeh S, Bahr S, Brost RL, Chen Y, Cokol M, Deshpande R, Li Z, Lin ZY, Liang W, Marback M, Paw J, San Luis BJ, Shuteriqi E, Tong AH, van Dyk N, Wallace IM, Whitney JA, Weirauch MT, Zhong G, Zhu H, Houry WA, Brudno M, Ragibizadeh S, Papp B, Pal C, Roth FP, Giaever G, Nislow C, Troyanskaya OG, Bussey H, Bader GD, Gingras AC, Morris QD, Kim PM, Kaiser CA, Myers CL, Andrews BJ, Boone C. The genetic landscape of a cell. Science. 2010;327:425–431. doi: 10.1126/science.1180823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czabany T, Athenstaedt K, Daum G. Synthesis, storage and degradation of neutral lipids in yeast. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1771:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE, Ahmadian M, Jaworski K, Sarkadi-Nagy E, Sul HS. Regulation of lipolysis in adipocytes. Annual review of nutrition. 2007;27:79–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichmann TO, Kumari M, Haas JT, Farese RV, Jr, Zimmermann R, Lass A, Zechner R. Studies on the substrate and stereo/regioselectivity of adipose triglyceride lipase, hormone-sensitive lipase, and diacylglycerol-O-acyltransferases. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:41446–41457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.400416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejsing CS, Sampaio JL, Surendranath V, Duchoslav E, Ekroos K, Klemm RW, Simons K, Shevchenko A. Global analysis of the yeast lipidome by quantitative shotgun mass spectrometry. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:2136–2141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811700106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada de Martin P, Du Y, Novick P, Ferro-Novick S. Ice2p is important for the distribution and structure of the cortical ER network in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of cell science. 2005;118:65–77. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakas S, Konstantinou C, Carman GM. DGK1-encoded diacylglycerol kinase activity is required for phospholipid synthesis during growth resumption from stationary phase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:1464–1474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.194308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto T, Parton RG. Not just fat: the structure and function of the lipid droplet. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 3. 2011 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbarino J, Padamsee M, Wilcox L, Oelkers PM, D'Ambrosio D, Ruggles KV, Ramsey N, Jabado O, Turkish A, Sturley SL. Sterol and diacylglycerol acyltransferase deficiency triggers fatty acid-mediated cell death. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:30994–31005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.050443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg AS, Coleman RA, Kraemer FB, McManaman JL, Obin MS, Puri V, Yan QW, Miyoshi H, Mashek DG. The role of lipid droplets in metabolic disease in rodents and humans. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:2102–2110. doi: 10.1172/JCI46069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillitsch K, Connerth M, Kofeler H, Arrey TN, Rietschel B, Wagner B, Karas M, Daum G. Lipid particles/droplets of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae revisited: lipidome meets proteome. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2011;1811:1165–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han GS, O'Hara L, Siniossoglou S, Carman GM. Characterization of the yeast DGK1-encoded CTP-dependent diacylglycerol kinase. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:20443–20453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802866200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SH, Han GS, Iwanyshyn WM, Carman GM. Regulation of the PIS1-encoded phosphatidylinositol synthase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by zinc. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:29017–29024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505881200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry SA, Kohlwein SD, Carman GM. Metabolism and regulation of glycerolipids in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190:317–349. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.130286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickenbottom SJ, Kimmel AR, Londos C, Hurley JH. Structure of a lipid droplet protein; the PAT family member TIP47. Structure. 2004;12:1199–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilvo M, Denkert C, Lehtinen L, Muller B, Brockmoller S, Seppanen-Laakso T, Budczies J, Bucher E, Yetukuri L, Castillo S, Berg E, Nygren H, Sysi-Aho M, Griffin JL, Fiehn O, Loibl S, Richter-Ehrenstein C, Radke C, Hyotylainen T, Kallioniemi O, Iljin K, Oresic M. Novel theranostic opportunities offered by characterization of altered membrane lipid metabolism in breast cancer progression. Cancer research. 2011;71:3236–3245. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inokoshi J, Tomoda H, Hashimoto H, Watanabe A, Takeshima H, Omura S. Cerulenin-resistant mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae with an altered fatty acid synthase gene. Molecular & general genetics : MGG. 1994;244:90–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00280191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacquier N, Choudhary V, Mari M, Toulmay A, Reggiori F, Schneiter R. Lipid droplets are functionally connected to the endoplasmic reticulum in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of cell science. 2011;124:2424–2437. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagiwada S, Hosaka K, Murata M, Nikawa J, Takatsuki A. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae SCS2 gene product, a homolog of a synaptobrevin-associated protein, is an integral membrane protein of the endoplasmic reticulum and is required for inositol metabolism. Journal of bacteriology. 1998;180:1700–1708. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.7.1700-1708.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh JL, Ding H, Costanzo M, Baryshnikova A, Toufighi K, Bader GD, Myers CL, Andrews BJ, Boone C. DRYGIN: a database of quantitative genetic interaction networks in yeast. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:D502–507. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahmer N, Guo Y, Wilfling F, Hilger M, Lingrell S, Heger K, Newman HW, Schmidt-Supprian M, Vance DE, Mann M, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Phosphatidylcholine synthesis for lipid droplet expansion is mediated by localized activation of CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase. Cell metabolism. 2011;14:504–515. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchler K, Daum G, Paltauf F. Subcellular and submitochondrial localization of phospholipid-synthesizing enzymes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of bacteriology. 1986;165:901–910. doi: 10.1128/jb.165.3.901-910.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerschner L, Moessinger C, Thiele C. Imaging of lipid biosynthesis: how a neutral lipid enters lipid droplets. Traffic. 2008;9:338–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurat CF, Natter K, Petschnigg J, Wolinski H, Scheuringer K, Scholz H, Zimmermann R, Leber R, Zechner R, Kohlwein SD. Obese yeast: triglyceride lipolysis is functionally conserved from mammals to yeast. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:491–500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508414200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurat CF, Wolinski H, Petschnigg J, Kaluarachchi S, Andrews B, Natter K, Kohlwein SD. Cdk1/Cdc28-dependent activation of the major triacylglycerol lipase Tgl4 in yeast links lipolysis to cell-cycle progression. Molecular cell. 2009;33:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankester DL, Brown AM, Zammit VA. Use of cytosolic triacylglycerol hydrolysis products and of exogenous fatty acid for the synthesis of triacylglycerol secreted by cultured rat hepatocytes. Journal of lipid research. 1998;39:1889–1895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leber R, Zinser E, Zellnig G, Paltauf F, Daum G. Characterization of lipid particles of the yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1994;10:1421–1428. doi: 10.1002/yea.320101105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listenberger LL, Han X, Lewis SE, Cases S, Farese RV, Jr, Ory DS, Schaffer JE. Triglyceride accumulation protects against fatty acid-induced lipotoxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:3077–3082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630588100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen CJ, Levine TP. A highly conserved binding site in vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein (VAP) for the FFAT motif of lipid-binding proteins. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:14097–14104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500147200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen CJ, Young BP, Tavassoli S, Levine TP. Inheritance of cortical ER in yeast is required for normal septin organization. The Journal of cell biology. 2007;179:467–483. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200708205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine MS, McKenzie A, 3rd, Demarini DJ, Shah NG, Wach A, Brachat A, Philippsen P, Pringle JR. Additional modules for versatile and economical PCR-based gene deletion and modification in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 1998;14:953–961. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199807)14:10<953::AID-YEA293>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nature reviews Cancer. 2007;7:763–777. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S, Martin S, Parton RG. Lipid droplet-organelle interactions; sharing the fats. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1791:441–447. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natter K, Leitner P, Faschinger A, Wolinski H, McCraith S, Fields S, Kohlwein SD. The spatial organization of lipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae derived from large scale green fluorescent protein tagging and high resolution microscopy. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2005;4:662–672. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400123-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North M, Steffen J, Loguinov AV, Zimmerman GR, Vulpe CD, Eide DJ. Genome-wide functional profiling identifies genes and processes important for zinc-limited growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelkers P, Cromley D, Padamsee M, Billheimer JT, Sturley SL. The DGA1 gene determines a second triglyceride synthetic pathway in yeast. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:8877–8881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oelkers P, Tinkelenberg A, Erdeniz N, Cromley D, Billheimer JT, Sturley SL. A lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase-like gene mediates diacylglycerol esterification in yeast. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:15609–15612. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penno A, Hackenbroich G, Thiele C. Phospholipids and lipid droplets. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2013;1831:589–594. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petschnigg J, Wolinski H, Kolb D, Zellnig G, Kurat CF, Natter K, Kohlwein SD. Good fat, essential cellular requirements for triacylglycerol synthesis to maintain membrane homeostasis in yeast. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:30981–30993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.024752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajakumari S, Rajasekharan R, Daum G. Triacylglycerol lipolysis is linked to sphingolipid and phospholipid metabolism of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2010;1801:1314–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen JT, Faergeman NJ, Kristiansen K, Knudsen J. Acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP) can mediate intermembrane acyl-CoA transport and donate acyl-CoA for beta-oxidation and glycerolipid synthesis. The Biochemical journal. 1994;299(Pt 1):165–170. doi: 10.1042/bj2990165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raussens V, Fisher CA, Goormaghtigh E, Ryan RO, Ruysschaert JM. The low density lipoprotein receptor active conformation of apolipoprotein E. Helix organization in n-terminal domain-phospholipid disc particles. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:25825–25830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandager L, Gustavsson MH, Stahl U, Dahlqvist A, Wiberg E, Banas A, Lenman M, Ronne H, Stymne S. Storage lipid synthesis is non-essential in yeast. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:6478–6482. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109109200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuldiner M, Collins SR, Thompson NJ, Denic V, Bhamidipati A, Punna T, Ihmels J, Andrews B, Boone C, Greenblatt JF, Weissman JS, Krogan NJ. Exploration of the function and organization of the yeast early secretory pathway through an epistatic miniarray profile. Cell. 2005;123:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger D, Daum G. Synthesis of triacylglycerols by the acyl-coenzyme A:diacyl-glycerol acyltransferase Dga1p in lipid particles of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Journal of bacteriology. 2002;184:519–524. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.2.519-524.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Cardalda A, Fakas S, Pascual F, Choi HS, Carman GM. Phosphatidate phosphatase plays role in zinc-mediated regulation of phospholipid synthesis in yeast. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:968–977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.313130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone SJ, Levin MC, Farese RV., Jr Membrane topology and identification of key functional amino acid residues of murine acyl-CoA:diacylglycerol acyltransferase-2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:40273–40282. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607986200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymanski KM, Binns D, Bartz R, Grishin NV, Li WP, Agarwal AK, Garg A, Anderson RG, Goodman JM. The lipodystrophy protein seipin is found at endoplasmic reticulum lipid droplet junctions and is important for droplet morphology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:20890–20895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704154104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli S, Chao JT, Young BP, Cox RC, Prinz WA, de Kroon AI, Loewen CJ. Plasma membrane-endoplasmic reticulum contact sites regulate phosphatidylcholine synthesis. EMBO reports. 2013 doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther TC, Farese RV., Jr Lipid droplets and cellular lipid metabolism. Annual review of biochemistry. 2012;81:687–714. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061009-102430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CW, Lee SC. The ubiquitin-like (UBX)-domain-containing protein Ubx2/Ubxd8 regulates lipid droplet homeostasis. Journal of cell science. 2012;125:2930–2939. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins D, Gibbons GF. The lipolysis/esterification cycle of hepatic triacylglycerol. Its role in the secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein and its response to hormones and sulphonylureas. The Biochemical journal. 1992;284(Pt 2):457–462. doi: 10.1042/bj2840457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfling F, Wang H, Haas JT, Krahmer N, Gould TJ, Uchida A, Cheng JX, Graham M, Christiano R, Frohlich F, Liu X, Buhman KK, Coleman RA, Bewersdorf J, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Triacylglycerol synthesis enzymes mediate lipid droplet growth by relocalizing from the ER to lipid droplets. Developmental cell. 2013;24:384–399. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C, Wardell MR, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Agard DA. Three-dimensional structure of the LDL receptor-binding domain of human apolipoprotein E. Science. 1991;252:1817–1822. doi: 10.1126/science.2063194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolinski H, Kolb D, Hermann S, Koning RI, Kohlwein SD. A role for seipin in lipid droplet dynamics and inheritance in yeast. Journal of cell science. 2011;124:3894–3904. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LY, Kuksis A, Myher JJ, Steiner G. Origin of triacylglycerol moiety of plasma very low density lipoproteins in the rat: structural studies. Journal of lipid research. 1995;36:125–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanghellini J, Natter K, Jungreuthmayer C, Thalhammer A, Kurat CF, Gogg-Fassolter G, Kohlwein SD, von Grunberg HH. Quantitative modeling of triacylglycerol homeostasis in yeast--metabolic requirement for lipolysis to promote membrane lipid synthesis and cellular growth. The FEBS journal. 2008;275:5552–5563. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner R, Kienesberger PC, Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Lass A. Adipose triglyceride lipase and the lipolytic catabolism of cellular fat stores. Journal of lipid research. 2009;50:3–21. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800031-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.