Abstract

Efforts have been focused on developing in vitro assays for the study of microvessels because in vivo animal studies are more time-consuming, expensive, and observation and quantification are very challenging. However, conventional in vitro microvessel assays have limitations when representing in vivo microvessels with respect to three-dimensional (3D) geometry and providing continuous fluid flow. Using a combination of photolithographic reflowable photoresist technique, soft lithography, and microfluidics, we have developed a multi-depth circular cross-sectional endothelialized microchannels-on-a-chip, which mimics the 3D geometry of in vivo microvessels and runs under controlled continuous perfusion flow. A positive reflowable photoresist was used to fabricate a master mold with a semicircular cross-sectional microchannel network. By the alignment and bonding of the two polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microchannels replicated from the master mold, a cylindrical microchannel network was created. The diameters of the microchannels can be well controlled. In addition, primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) seeded inside the chip showed that the cells lined the inner surface of the microchannels under controlled perfusion lasting for a time period between 4 days to 2 weeks.

Keywords: Bioengineering, Issue 80, Bioengineering, Tissue Engineering, Miniaturization, Microtechnology, Microfluidics, Reflow photoresist, PDMS, Perfusion flow, Primary endothelial cells

Introduction

Microvessels, as a part of the circulation system, mediate the interactions between blood and tissues, support metabolic activities, define tissue microenvironment, and play a critical role in many health and pathological conditions. Recapitulation of functional microvessels in vitro could provide a platform for the study of complex vascular phenomena. However, conventional in vitro microvessel assays, such as endothelial cell migration assays, endothelial tube formation assays, and rat and mouse aortic ring assays, are unable to recreate the in vivo microvessels with respect to three-dimensional (3D) geometry and continuous flow control1-8. Studies of microvessels using animal models and in vivo assays, such as corneal angiogenesis assay, chick chorioallantoic membrane angiogenesis assay, and Matrigel plug assay, are more time-consuming, high in cost, challenging with respect to observation and quantifications, and raise ethical issues1, 9-13.

Advances in micromanufacturing and microfluidic chip technologies have enabled a variety of insights into biomedical sciences while curtailing the high experimental costs and complexities associated with animals and in vivo studies14, such as easily and tightly controlled biological conditions and dynamic fluidic environments, which would not have been possible with conventional macroscale techniques.

Here, we present an approach to construct an endothelialized microchannels-on-a-chip which mimics the 3D geometry of in vivo microvessels and runs under controlled continuous perfusion flow by using the combination of photolithographic reflowable photoresist technique, soft lithography, and microfluidics.

Protocol

1. Photolithography Fabrication of Photoresist Master Mold

The following protocol shows the process to fabricate the microchannels with diameters between 30-60 μm. To get a microchannel with a smaller diameter (less than 30 μm), a single spin-coating of photoresist is needed.

Transfer the reflow photoresist from the refrigerator at 4 °C to the cleanroom 24 hr prior to use and allow it to warm to room temperature.

Clean a silicon wafer and bake it for one hr at 150 °C to allow it to dehydrate. The dehydration will assist the photoresist adhesion to the silicon substrate.

Spin-coat the first layer of photoresist using the following recipe:

| Step | Time (Seconds) | Speed (rpm) | Acceleration |

| 1 | 2 | 300 | highest |

| 2 | 10 | 0 | |

| 3 | 3 | 300 | highest |

| 4 | 60 | 600 | highest |

| 5 | 10 | 500 | highest |

| 6 | 10 | 600 | highest |

Then, bake the wafer on a hotplate with a temperature of 110 °C for 90 sec. After the soft bake the thickness of the photoresist will be 20-30 μm.

Spin coat a second layer of photoresist following the same recipe used for the first layer.

Soft bake the wafer again by placing it on a hotplate with a temperature of 110 °C for 90 sec. After this soft bake the thickness of the photoresist will be 40-60 μm.

Generate positive master patterns by exposing the photoresist to UV light with an exposure dose of 14,500 mJ/cm2 through a film mask.

Dilute the developer with deionized (DI) water (1:2 (v/v)). Rinse the wafer repeatedly in the solution until the pattern is fully developed. Then wash the wafer with DI water and dry it using nitrogen gas.

Reflow: Place the wafer on a hotplate with a temperature of 120 °C for 4 min and cover with a glass Petri dish to prevent solvent evaporation. Remove the wafer from the hotplate and allow it to cool to room temperature. The photoresist thickness after reflow will be 50-60 μm.

2. Soft Lithography Fabrication of PDMS Microchannel Network

Prepare polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) solution at the weight ratio of 10:1 (base:curing agent) and mix it thoroughly using a planetary centrifugal mixer.

Cast the PDMS solution onto the reflowed photoresist master mold. Place the casted PDMS in a desiccator for 15 min to degas. Use nitrogen gas to remove any remaining bubbles if necessary.

Bake the PDMS in an oven at a temperature of 60 °C for 3 hr to allow it to cure. Then remove the cured PDMS layer from the master mold.

Use a sharpened puncher to create inlet/outlet holes by punching holes in the channel network. Clean the surface of the PDMS using nitrogen gas.

Treat two PDMS layers with oxygen plasma for 30 sec inside a plasma cleaner at an operating pressure of 4.5 x 10-2 Torr and an oxygen flow rate of 3.5 ft3/min. Then, align the surfaces of the PDMS manually under an optical microscope. Use a drop of water if necessary for a better control of the alignment.

Bake the device in an oven at 60 °C for 30 min to achieve permanent bonding.

3. HUVEC Culture and Seeding in the Chip

Culture the HUVECs with culture medium with L-glutamine supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For the experiment passages between 2 and 5 were used.

Once the HUVECs are confluent, count the cells and harvest them by first rinsing the cells with HEPES buffered saline solution (HEPES-BSS), and then treat the cells with trypsin/EDTA and incubate for 2-6 min at 37 °C. After the trypsinization is complete, neutralize the trypsin/EDTA with trypsin neutralizing solution. Centrifuge and suspend the cells in culture medium with 8% dextran to collect them. Dextran was used to increase the medium viscosity to aid in better cell seeding and attachment.

Treat the device with oxygen plasma for 5 min with an operating pressure of 4.5 x 10-2 Torr and an oxygen flow rate of 3.5 ft3/min. Then load the device with DI water and treat with UV light for 8 hr in a laminar biosafety hood for sterilization.

One day before the cells are ready, wash the device with 1x phosphate buffered saline (1x PBS) then coat with fibronectin (100 μg/ml, diluted with 1x PBS) and incubate in the refrigerator at 4 °C overnight.

After the fibronectin coating, wash the device with 1x PBS then load with culture medium. Incubate the device at a temperature of 37 °C for 15 min.

Load the HUVEC cells in 8% dextran culture medium with a cell concentration of 3-4 x 106 cells/ml. Place a 20 μl droplet of cells at one inlet of the device and tilt it to introduce the cells into the microfluidic channel. After 15-20 min the cells will begin to attach to the side walls of the channels. Rotate the device every 15 min to create a more uniform distribution of cells. If necessary, additional loading can be performed.

4. Long-term Perfusion Setup

After 5-6 hr of static culture, the attached HUVECs will start to fully spread out. Set up perfusion using a remote controlled syringe pump system with a steady flow of 10 μl/hr. Perfusion can be adjusted for a higher flow rate, and can last for a time period between 4 days to 2 weeks.

5. Cell Staining and Microscope Characterization

When the cells reach confluence inside the device, firstly, wash the device with 1x PBS to thoroughly remove the medium. Then load the device with red dye diluted with diluent (4 μl-1 ml). Load the dye similar to the cell loading procedure. Incubate the device in the dark for 5 min at room temperature, and then wash the device with culture medium to stop the staining. Long incubation of the dye can cause cellular toxicity and disadhesion.

Load the device with blue dye diluted with 1x PBS (2 droplets per ml). Incubate in the dark for 5 min at room temperature then thoroughly wash the device with 1x PBS.

Examine the cell staining under an inverted optical microscope. If the staining was good, load the microchannels with fixing medium (3.5% paraformaldehyde diluted with 1x PBS), then submerge the device in fixing medium and completely cover it with aluminum foil. Store the device in the refrigerator at a temperature of 4 °C to prevent the device from drying out and photobleaching. The fixed device is now ready for confocal imaging, which can be done by a laser scanning confocal microscope.

Representative Results

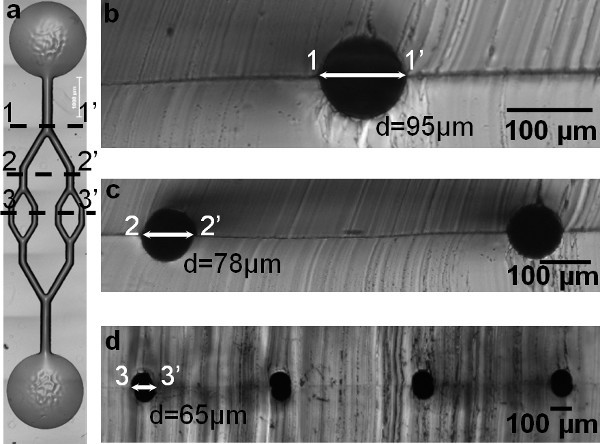

Our approach to fabricate the multi-depth microchannel network mimics the complex 3D geometries of in vivo microvessels, in which the microchannels have rounded cross sections15. Additionally, the diameters of parent branching channels and the daughter channels approximately obey Murray's law for maintaining the fluid flow at a required level so that the overall channel resistance is low and flow velocities are more uniform throughout the network16-18. The processes and results for the fabrication of a semicircular photoresist master mold and a circular cross-sectional PDMS microchannel network were demonstrated in Movie 1, Figure 2, and Movie 2, respectively. The geometric features of the PDMS microchannel network were characterized and shown in Figure 2. Our results show that the photoresist reflow technique can create multi-depth branching channel networks in a more convenient approach by photoresist reflow techniques, and allow designing the microvascular biomimetic systems which approximately obey Murray's Law.

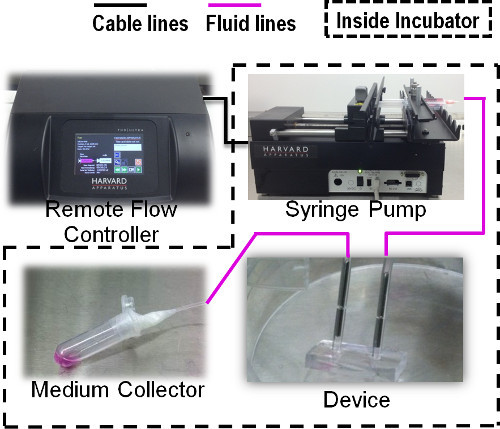

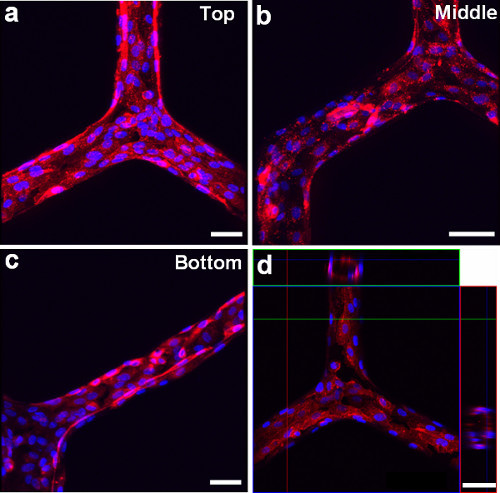

In many in vitro models, vascular cells are normally cultured on planar plates, filters, or these substrates coated with hydrogels. Under these conditions the microvessels are randomly generated by cellular self-assembly. In addition, conventional assays have inherent difficulties in achieving a constant flow over endothelial cells. The lack of a long-term and continuous media flow prevents the ability to maintain the stability of endothelial cell monolayer with appropriate barrier functions. In our model, the benefit of applying microfluidics is the convenience for fluid access and control (varying flow rates, duration and patterns) as well as getting rid of waste. We demonstrate the processes for primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) seeding in the microchannels and setting a long-term fluid perfusion system for cell culture (Figure 3). Furthermore, because of the complex geometries of in vivo microvasculature, real-time monitoring of those small vessels is difficult. The developed PDMS based chip offers good optical properties and allows for high-quality and real-time imaging of the endothelialized microchannels. (Figures 4 and Movie 3)

Movie 1. Schematic fabrication procedures for photoresist master molds. Initially, a pre-cleaned silicon substrate was prepared. The positive reflow photoresist layer was spin-coated onto the silicon substrate and was baked and dried. The photoresist was exposed to UV light through a patterned mask, and then, the patterned microchannels were developed. A semicircular cross-sectional microchannel network was created after the reflow at 120 °C for 4 min. Click here to view movie.

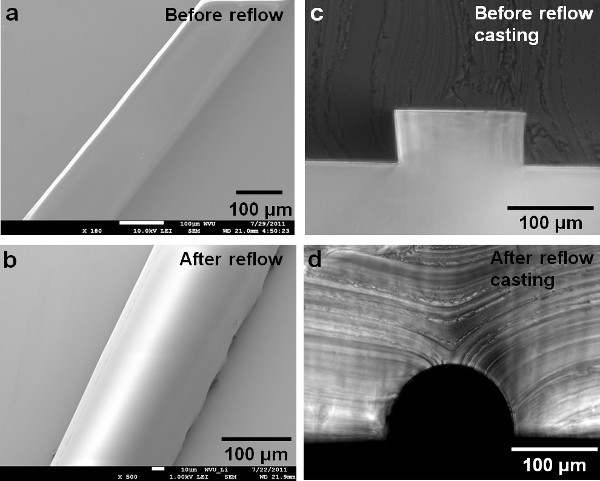

Figure 1. SEM shows the developed photoresist.a) before reflow; b) after reflow; c) molded PDMS shows the cross section of the resist before reflowing; the picture shows a rectangular cross section; d) molded PDMS showing a semicircular cross-section of the resist after reflowing; The cross section after reflow was controlled by the initial dimension design of the pattern and reflow temperature. (Reprinted with permission from Reference 15). Click here to view larger figure.

Figure 1. SEM shows the developed photoresist.a) before reflow; b) after reflow; c) molded PDMS shows the cross section of the resist before reflowing; the picture shows a rectangular cross section; d) molded PDMS showing a semicircular cross-section of the resist after reflowing; The cross section after reflow was controlled by the initial dimension design of the pattern and reflow temperature. (Reprinted with permission from Reference 15). Click here to view larger figure.

Movie 2. The schematic fabrication procedures for cylindrical microchannel network in PDMS. A PDMS solution was cast onto the photoresist mold and cured in the oven at a temperature of 60 °C for 3 hr. Two identical cured PDMS layers, each of which has a semicircular cross-sectional microchannel network, were aligned and bonded together to form microchannels with circular cross sections. Click here to view movie.

Figure 2. a) An aligned and bonded cylindrical microchannel network in PDMS. b-d) Circular cross-sections of PDMS molds show channel dimensions at each branching level (1-1', 2-2', and 3-3'). In addition, these figures show the creation of a multibranching and multidepth circular cross-sectional microfluidic channel network.

Figure 2. a) An aligned and bonded cylindrical microchannel network in PDMS. b-d) Circular cross-sections of PDMS molds show channel dimensions at each branching level (1-1', 2-2', and 3-3'). In addition, these figures show the creation of a multibranching and multidepth circular cross-sectional microfluidic channel network.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram showing the long-term perfusion through the chip using a remote controlled syringe pump.

Figure 3. Schematic diagram showing the long-term perfusion through the chip using a remote controlled syringe pump.

Figure 4. Microscopy images using fluorescent cell membrane dye (red) and cell nuclear dye (blue) show that the HUVECs line the inner surface of a cylindrical microchannel network at different branching regions. a) Top, b) Middle, and c) Bottom. d) Confocal microscopy image shows the circular cross-sectional view of HUVECs lining the channel network. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Figure 4. Microscopy images using fluorescent cell membrane dye (red) and cell nuclear dye (blue) show that the HUVECs line the inner surface of a cylindrical microchannel network at different branching regions. a) Top, b) Middle, and c) Bottom. d) Confocal microscopy image shows the circular cross-sectional view of HUVECs lining the channel network. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Movie 3. Confocal movie showing the cell lining along the circular channel network. Click here to view movie.

Discussion

1. Master mold fabrication

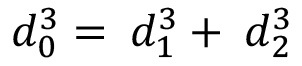

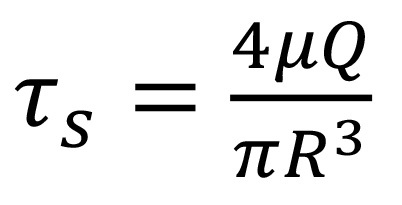

One of the designing and guiding principles for vascular morphometry is known as Murray's law16, which states that the distribution of vessel diameters throughout the network is governed by minimum energy consideration. It also states that the cube of the diameters of a parent vessel at a bifurcation equals the sum of the cubes of the diameters of the daughter vessels ( )19 Additionally, Poiseuille's law has been used to estimate the magnitude of the shear stress in most of the vasculature as

)19 Additionally, Poiseuille's law has been used to estimate the magnitude of the shear stress in most of the vasculature as  . in which

. in which ![]() is the hemodynamic shear stress, μ is the blood viscosity, Q is the flow rate, and R is the radius of the vessel20,21. For symmetric bifurcations, an important consequence based on Murray's law and Poiseuille's law is that the wall shear stress remains constant throughout the vascular network. Thus, for a fabricated symmetric microfluidic channel network with circular cross-sections, if the channel dimensions at bifurcations obey Murray's law, the shear stress experienced by the endothelial cells should be constant at different branching channels.

is the hemodynamic shear stress, μ is the blood viscosity, Q is the flow rate, and R is the radius of the vessel20,21. For symmetric bifurcations, an important consequence based on Murray's law and Poiseuille's law is that the wall shear stress remains constant throughout the vascular network. Thus, for a fabricated symmetric microfluidic channel network with circular cross-sections, if the channel dimensions at bifurcations obey Murray's law, the shear stress experienced by the endothelial cells should be constant at different branching channels.

Many microfabrication techniques and processes have been applied to the fabrication of microchannels used for vascular cells22-25, however, the resulting microchannels resulted in rectangular, square or trapezoidal cross-sections of channels. The rectangular cross-sections of channels are constructed with sharp corners and abrupt transitions at bifurcations, which can impose widely varying fluid shear stresses and nonphysiological geometries on cells in different channel positions, thus resulting in variations in cell physiology26,27.

A photoresist reflow process, resulting in a rounded channel profile, involves two procedures, 1) the melting of the patterned photoresist and the liquid resist surfaces are pulled into a shape which minimizes the energy of the system28,29 and 2) a cooling and solidification phase follows the melting process. The shapes of the reflowed channels are well approximated by a semicylindrical surface. Followed by reflowed master mold fabrication, a standard soft lithography approach was used to fabricate the PDMS microfluidic channel network with a circular cross-section. Our results showed that the photoresist reflow technique can create multi-depth branching microchannel networks in a more straight forward approach, and allows us to design microvascular biomimetic systems that approximately obey Murray's Law and mimic the geometry of in vivo microvasculature, so that the overall channel resistance is low, and the shear stress variations at different branching levels can be minimized in the fabricated microfluidic channel network.

The physiologic blood microvessels adopt a roughly circular cross-section with radii between 30-300 μm30. The dimensions for the demonstrated microchannel network in this paper were varied around 60 μm to 100 μm at different branching levels. To fabricate microchannels with different range of diameters for mimicking in vivo microvessels, we recommend to use single spun layer reflow resist (limited to 30 μm) or other lower viscosity resists. For a microchannel with a larger diameter (30-60 μm), a double-coating procedure can be applied to get a thicker photoresist film15. Additional spin-coatings above two layers should be avoided to prevent nonuniform film thickness, which can result in an inaccurate exposure dose. For a film thickness above 60 μm, other higher viscous reflow photoresists are recommended.

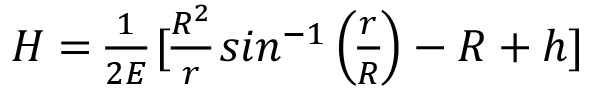

In an ideal condition, to fabricate a resist mold with a semicircular cross section, the film thickness can be initially predetermined by giving a required width and focal length of the microchannel as  , where H is the required spun-film thickness, r is half of the channel width, R is the constant radius of curvature, h is the central height of the curvature, and E is the ratio of resist volumes of the microchannel before and after reflowing31. For a cylindrical surface of a given width of microchannel, one particular volume of the resist is required. However, several parameters have been reported to affect the reflowed photoresist and make the resulted channel profiles more complex, such as critical angle and boundary movement between the photoresist and the solid substrate, material evaporation during reflow baking, temperature and timing for the reflow process, outgassing, substrate uniformity, and resist properties32-34. For example, the reflow temperature and timing can result in a volume change causing the boundary movement and hence varying the critical angle and final reflowed resist profile 33. As reported by our previous work 15, the reflow process decreased the channel widths by 2% on average because of photoresist volume reductions and boundary movement. In addition, the volume for getting a cylindrical surface needs to make allowance for the effect of material evaporation during the reflow process 35,36. If cylindrical surfaces with different radii are required through a microchannel network it is necessary to vary the width of the microchannels, resulting in variations in the volumes at different regions in the network 15. To successfully fabricate a cylindrical channel network with different diameters, the resists widths/volumes, reflow temperatures and timing, critical angles, boundary movement, resist viscosities and spin coating protocols, and substrate properties must be considered and tested.

, where H is the required spun-film thickness, r is half of the channel width, R is the constant radius of curvature, h is the central height of the curvature, and E is the ratio of resist volumes of the microchannel before and after reflowing31. For a cylindrical surface of a given width of microchannel, one particular volume of the resist is required. However, several parameters have been reported to affect the reflowed photoresist and make the resulted channel profiles more complex, such as critical angle and boundary movement between the photoresist and the solid substrate, material evaporation during reflow baking, temperature and timing for the reflow process, outgassing, substrate uniformity, and resist properties32-34. For example, the reflow temperature and timing can result in a volume change causing the boundary movement and hence varying the critical angle and final reflowed resist profile 33. As reported by our previous work 15, the reflow process decreased the channel widths by 2% on average because of photoresist volume reductions and boundary movement. In addition, the volume for getting a cylindrical surface needs to make allowance for the effect of material evaporation during the reflow process 35,36. If cylindrical surfaces with different radii are required through a microchannel network it is necessary to vary the width of the microchannels, resulting in variations in the volumes at different regions in the network 15. To successfully fabricate a cylindrical channel network with different diameters, the resists widths/volumes, reflow temperatures and timing, critical angles, boundary movement, resist viscosities and spin coating protocols, and substrate properties must be considered and tested.

2. Long-term cell culture

The importance of flow and the associated wall shear stress has been well recognized in regulating endothelial biology. This has been seen in areas such as inducing changes in cell shape and orientation, secretion and organization, proliferation and differentiation, intracellular signaling, cytoskeleton protein production and gene expression, vessel maturation and structure, and barrier functions37-47. The current in vitro methods for forming endothelial tubes generally rely on endothelial cells' (ECs) self-organization with or without mesenchymal cells in extracellular matrix (ECM) (type I collagen, fibrin, or Matrigel)48-54. Although these cultures have successfully modeled several microvascular behaviors, the artificial vessels formed through a random process of morphogenesis lack the desired spatial reproducibility and orientation. Additionally, the impact of flow on microvascular stability remains largely unknown because these self-assembled vessels do not easily combine luminal flow with a 3D tubular organization55, posing a challenge to engineering blood vessels to have barrier functions and long-term vascular stability.

Microfluidic systems have proven to be practical and useful for introducing flows to a variety of biochemical and biological analysis56,57. Our approach provides a convenient way to introduce fluid flow over the cultured cells. We used an advanced remote controlled syringe pump to achieve a convenient yet steady and accurate flow control through the microchannels for long-term cell culture (between 4 days and 2 weeks).

3. Cell culture in the chip

Plasma-assisted oxidation of the PDMS microchannels introduces silanol groups (SiOH) on the surfaces which renders the surface hydrophilic and aids in further protein coatings. Different ECM proteins (fibronectin, gelatin, and collagen) were tested for cell attachment, and the best result was found to be fibronectin coating. The HUVECs were prepared at a concentration of 3 x 106 cells/ml in culture media supplemented with 8% dextran (70 kDa) for seeding. Dextran increases the viscosity of the media to enable fine control over seeding density of ECs.

A confluent monolayer was developed between 2-4 days of the HUVECs being exposed to a constant medium flow. To visualize the cells after the cell culture, we labeled cells with membrane staining and nuclei staining dyes, these dyes exhibited lower cytotoxicity58. We stained the cells as an adherent monolayer cultured in the chip. A complete 1x PBS wash is necessary to prevent extra dyes trapped inside the chip.

In summary, by the combination of reflow photoresist technique and PDMS replication, the developed multi-depth microchannel network was approximated by a circular surface and the channel diameters at each bifurcation approximately obey Murray's law. The shear stress variations at different branching levels can be minimized in the fabricated microfluidic channel network. In addition, the results from cell culture indicated the healthy condition of the endothelial cells. Thus, the developed endothelialized microchannels-on-a-chip provides a rapid and reproducible approach to create circular cross-sectional multi-branching and multidepth microchannel networks, which mimics the geometry of in vivo microvessels. The procedure illustrates the use of unique capabilities in advanced micromanufacturing and microfluidic technologies to create a microvasculature model with a long-term, continuous perfusion control as well as high-quality and real-time imaging capability. With the increasing utility of microfluidic channels for cell biology, tissue engineering, and bioengineering applications, the endothelialized microchannels-on-a-chip is a potential assay for microvascular research.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by National Science Foundation (NSF 1227359), WVU EPSCoR program funded by the National Science Foundation (EPS-1003907), WVU ADVANCE office sponsored by the National Science Foundation (1007978), and WVU PSCoR, respectively. The microfabrication work was done in WVU Shared Research Facilities (Cleanroom facilities) and Microfluidic Integrative Cellular Research on Chip Laboratory (MICRoChip Lab) at West Virginia University. The confocal imaging was done at WVU Microscope Imaging Facility.

References

- Adair TH. Angiogenesis: Integrated systems physiology: from molecule to function to disease. 1st edition. Biota Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin AM. In vitro assays of angiogenesis for assessment of angiogenic and anti-angiogenic agents. Microvasc. Res. 2007;74:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EJ, Staton CA. Angiogenesis assays: A critical appraisal of current techniques. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2006. Tubule formation assays; pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsu MN, Davis JJ, Hughes CCW. Optimized fibrin gel bead assay for the study of angiogenesis. J. Vis. Exp. 2007. p. e186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nicosia RF, Ottinetti A. Growth of microvessels in serum-free matrix culture of rat aorta. A quantitative assay of angiogenesis in vitro. Lab. Invest. 1990;63:115–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aplin AC, Fogel E, Zorzi P, Nicosia RF. The aortic ring model of angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol. 2008;443:119–136. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)02007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicosia RF. The aortic ring model of angiogenesis: A quarter century of search and discovery. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2009;13:4113–4136. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00891.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith LG, Swart MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:211–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Angiogenesis: An integrative approach from science to medicine. Springer; 2008. History of angiogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach R, Lewis R, Shinners B, Kubai L, Akhtar N. Angiogenesis assays: A critical overview. Clin. Chem. 2003;49:32–40. doi: 10.1373/49.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach R, Akhtar N, Lewis RL, Shinners BL. Angiogenesis assays: Problems and pitfalls. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2000;19:167–172. doi: 10.1023/a:1026574416001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton CA, Reed MW, Brown NJ. A critical analysis of current in vitro and in vivo angiogenesis assays. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2009;90:195–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2008.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton CA, Stribbling SM, et al. Current methods for assaying angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2004;85:233–248. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes C, Mehta G, Lesher-Perez SC, Takayama S. Organs-on-a-Chip: A focus on compartmentalized microdevices. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012;40(6):1211–1227. doi: 10.1007/s10439-011-0455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Li X, Martins-Green M, Liu Y. Microfabrication cylindrical microfluidic channel networks for microvascular research. Biomedical Microdevices. 2012;14(5):873–883. doi: 10.1007/s10544-012-9667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CD. The physiological principle of minimum work applied to the angle of branching of arteries. J. Gen. Physiol. 1926;9(6):835–841. doi: 10.1085/jgp.9.6.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir M, Medeiros JA. Arterial branching in man and monkey. J. Gen. Physiol. 1982;79:353–360. doi: 10.1085/jgp.79.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gafiychuk VV, Lubashevsky IA. On the principles of the vascular network branching. J. Theor. Biol. 2001;212:1–9. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman TF. On connecting large vessels to small. The meaning of Murray's law. J. Gen. Physiol. 1981;78(4):431–453. doi: 10.1085/jgp.78.4.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiya A, Bukhari R, Togawa T. Adaptive regulation of wall shear stress optimizing vascular tree function. Bull Math Biol. 1984;46(1):127–137. doi: 10.1007/BF02463726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBarbera M. Principles of design of fluid transport systems in zoology. Science. 1990;249:992–1000. doi: 10.1126/science.2396104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson DR, Cieslicki K, Gu X, Barber RW. Biomimetic design of microfluidic manifolds based on a generalized Murray's law. Lab Chip. 2006;6:447–454. doi: 10.1039/b516975e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Koo LY, et al. Microfluidic shear devices for quantitative analysis of cell adhesion. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:5257–5264. doi: 10.1021/ac049837t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevkoplyas SS, Gifford SC, Yoshida T, Bitensky MW. Prototype of an in vitro model of the microcirculation. Microvasc. Res. 2003;65:132–136. doi: 10.1016/s0026-2862(02)00034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaihara S, Borenstein J, et al. Silicon micromachining to tissue engineer branched vascular channels for liver fabrication. Tissue Eng. 2000;6:105–117. doi: 10.1089/107632700320739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AB, Chien S, Barakat AI, Nerem RM. Endothelial cellular response to altered shear stress. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2001;281(3):L529–L533. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2001.281.3.L529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerem RM, Alexander RW, et al. The study of the influence of flow on vascular endothelial biology. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1998;316(3):169–175. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly D, Stevens RF, Hutley MC, Davies N. The manufacture of microlenses by melting photoresist. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1990;1(8):759–766. [Google Scholar]

- Schilling A, Merz R, Ossmann C, Herzig HP. Surface profiles of reflow microlenses under the influence of surface tension and gravity. Opt. Eng. 2000;39(8):2171–2176. [Google Scholar]

- Young B, Heath JW. Wheater's functional histology: A text and colour atlas. 4th edition. Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill FT, Sheridan JT. Photoresist reflow method of microlens production. Part 1: Background and experiments. Optik Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2002;113:391–404. [Google Scholar]

- de Gennes PG. Wetting: statics and dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1985;57:827–863. [Google Scholar]

- Elias HG. An Introduction to Polymer Science. New York: VCH Publishers; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Voinov OV. Dynamic edge angles of wetting upon spreading of a drop over a solid surface. J. Appl. Mech. Tech. Phys. 1999;40:86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Daly D, Stevens RF, Hutley MC, Davies N. The manufacture of microlenses by melting photoresist. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1990;1:759. [Google Scholar]

- Jay TR, Stern MB. Preshaping photoresist for refractive microlens fabrication. Opt. Eng. 1994;33:3552–3555. [Google Scholar]

- Nerem RM, Alexander RW, et al. The Study of the influence of flow on vascular endothelial biology. Am. J. Med. Sci. 1998;316(3):169–175. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199809000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chien S, Li S, Shyy YJ. Effects of mechanical forces on signal transduction and gene expression in endothelial cells. Hypertension. 1998;31:162–169. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YS, Haga JH, Chien S. Molecular basis of the effects of shear stress on vascular endothelial cells. J. Biomech. 2005;38:1949–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Vunjak-Novakovic G, Wang Y, Niklason LE. A biocompatible endothelial cell delivery system for in vitro tissue engineering. Cell Transplant. 2009;18:731–743. doi: 10.3727/096368909X470919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EJ, Niklason LE. A novel flow bioreactor for in vitro microvascularization. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods. 2010;16:1191–1200. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2009.0652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chau L, Doran M, Cooper-White J. A novel multishear microdevice for studying cell mechanics. Lab Chip. 2009;9:1897–1902. doi: 10.1039/b823180j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeson A, Palmer M, Calfon M, Lang R. A relationship between apoptosis and flow during programmed capillary regression is revealed by vital analysis. Development. 1996;122:3929–3938. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Royen NJ, Piek J, Schaper W, Bode C, Buschmann I. Arteriogenesis: mechanisms and modulation of collateral artery development. J. Nucl. Cardiol. 2001;8:687–693. doi: 10.1067/mnc.2001.118924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaper W. Therapeutic arteriogenesis has arrived. Circulation. 2001;104(17):1994–1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarbell JM. Shear stress and the endothelial transport barrier. Cardiovas. Res. 2010;87(2):320–330. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CM, Lundberg MH, et al. Role of shear stress in endothelial cell morphology and expression of cyclooxygenase isoforms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc Biol. 2011;31:384–391. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.214031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesano R. In vitro rapid organization of endothelial cells into capillary-like networks is promoted by collagen matrices. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:1648–1652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.5.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darland DC, D'Amore PA. TGF beta is required for the formation of capillary-like structures in three-dimensional cocultures of 10T1/2 and endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2001;4(1):11–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1016611824696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley TJ, Kubota Y. Induction to morphologic differentiation of endothelial cells in culture. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1989;93:59S–61S. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12581070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzawa S, Endo H, Shioya N. Improved in vitro angiogenesis model by collagen density reduction and the use of type III collagen. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1993;30:244–251. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis GE, Bayless KJ, Mavila A. Molecular basis of endothelial cell morphogenesis in three-dimensional extracellular matrices. Anat. Rec. 2002;268:252–275. doi: 10.1002/ar.10159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velazquez OC, Snyder R, Liu Z, Fairman RM, Herlyn M. Fibroblast-dependent differentiation of human microvascular endothelial cells into capillary-like 3-dimensional networks. FASEB J. 2002;16:1316–1318. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-1011fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan D, Brown NJ, Bishop ET. Comparison of three in vitro human "angiogenesis" assays with capillaries formed in vivo. Angiogenesis. 2001;4:113–121. doi: 10.1023/a:1012218401036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang DG, Conti CJ. Endothelial cell development, vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and tumor neovascularization: an update. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2004;30:109–117. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-822975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama S, McDonald JC, et al. Patterning cells and their environments using multiple laminar fluid flows in capillary networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:5545–5548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho BS, Schuster TG, et al. Passively driven integrated microfluidic system for separation of motile sperm. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:1671–1675. doi: 10.1021/ac020579e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsa H, Upadhyay R, Sia SK. Uncovering the behaviors of individual cells within a multicellular microvascular community. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011;108(12):5133–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007508108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]